Cultural attribution of mental health suffering in Chinese societies:

the views of Chinese patients with mental illness and their caregivers

Fei-Hsiu Hsiao

PhD, RNAssistant Professor, College of Nursing, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan

Steven Klimidis

PhDAssociate Professor, School of Population Health, Centre for International Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Harry Minas

MDAssociate Professor, School of Population Health, Centre for International Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Eng-Seong Tan

MDProfessor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Submitted for publication: 14 September 2004 Accepted for publication: 24 June 2005

Correspondence: Fei-Hsiu Hsiao, Assistant Professor College of Nursing Taipei Medical University No. 250 Wu-Hsing Street Taipei 110 Taiwan Telephone: 886 2 27361661, ext. 6317 or 886 918153569 E-mail: hsiaofei@tmu.edu.tw H S I A O F - H , K L I M I D I S S , M I N A S H & T A N E - S ( 2 0 0 6 )

H S I A O F - H , K L I M I D I S S , M I N A S H & T A N E - S ( 2 0 0 6 ) Journal of Clinical Nursing 15, 998–1006

Cultural attribution of mental health suffering in Chinese societies: the views of Chinese patients with mental illness and their caregivers

Aims and objectives. This study examined the cultural attribution of distress in the Chinese, the special role of the family in distress and the specific emotional reactions within distress dictated by culture.

Methods. This phenomenological study illustrated the narrative representation of the experiences of suffering by the Chinese patients with mental illness. Twenty-eight Chinese–Australian patients and their caregivers were interviewed together in their homes. They were invited to talk about the stories of the patients’ experiences of suffering from mental illness. The interviews were recorded and transcribed to be further analysed according to the principles of narrative analysis.

Results. The results of case narration indicated that (1) because of the influence of Confucian ideals, interpersonal harmony was the key element of maintaining the Chinese patients’ mental health, (2) Chinese patients’ failure to fulfil cultural expectations of appropriate behaviours as family members contributed to distur-bance of interpersonal relationships and (3) Chinese patients’ failure to fulfil their familial obligations contributes to their diminished self-worth and increased sense of guilt and shame.

Conclusion. The findings of the present study suggest that Chinese people’s well-being is significantly determined by a harmonious relationship with others in the social and cultural context. Psychotherapy emphasizing an individual’s growth and autonomy may ignore the importance of maintaining interpersonal harmony in Chinese culture.

Relevance to clinical practice. The results of this study contribute to the essential knowledge about culturally sensitive nursing practices. An understanding of patient

suffering that is shaped by traditional cultural values helps nurses communicate empathy in a culturally sensitive manner to facilitate the therapeutic relationship and clinical outcomes.

Key words: Chinese culture, cultural empathy, guilt, interpersonal harmony, nursing, shame

Introduction

Social and cultural factors are thought to have an impact on psychological and mental health problems (Murphy & Leighton 1965, Tseng & McDermott 1981, Bond 1986, Cheng 1988, Lin et al. 1995). Chinese people’s mental well-being is frequently associated with stress arising from family environment or intergenerational relationships (Kleinman 1980). This might be because in Chinese society, an individ-ual’s sense of self is embedded in social relationships. Chinese people pay great attention to relationships with others, especially family members (Hwang 2000). In Chinese culture, family is perceived as the ‘great self’ (da wo) and an individual is embedded in the family (Bedford & Hwang 2003). An individual is obligated to do whatever it takes to maintain a well-functioning family. This is in contrast to the idea of self in the Western culture, which emphasizes an individual’s autonomy (Singh et al. 1962, Tarwarter 1966).

In Chinese societies, to be a person (zuo jen) is to fit an individual’s external behaviour to the interpersonal stand-ards of the society and culture. This maintains a satisfac-tory level of psychic and interpersonal equilibrium (Hsu 1971). Confucianism has played the most important role in determining rules for the appropriateness of interpersonal relationships between self and others, how to classify social relationships and how to behave towards others. Confu-cians define five major dyadic relationships (guanxi) in Chinese society: sovereign and subordinate, father and son, husband and wife, elder brother and younger and between friends. The relationships, except the relationship between friends, are vertical, illustrating superior and inferior relationships. The Chinese relational self stresses that personal identity is judged on how one behaves according to his or her relation to the group. According to the different categories of relationships, the 10 rules of righteousness (yi) were used as a guide to appropriate behaviours in each of the roles. The father, elder brother, husband, elders or rulers should act in accord with the principles of kindness, gentleness, righteousness and bene-volence, respectively. The son, younger brother, wife, juniors or minister should act in accordance with the principles of filial piety, obedience, submission, deference and loyalty. Accordingly, an individual’s failure to fulfil his

or her responsibility as demanded by these cultural values may contribute to the conflicts with others (Hwang 1978). Guilt and shame are common manifestations of psycholo-gical distress and are often considered symptoms of mental illness. The subjective experience of guilt emerges when one feels that he has violated the moral order and is responsible for a negative outcome (DeRivera 1984, Lindsay-Hartz 1984). Confucian relationalism regards highly personal duties and social goals, in contrast to the Western individualism’s emphasis on personal rights (Bedford & Hwang 2003). Chinese people often hold a sense of responsibility and obligation towards family and group. Therefore, a failure to fulfil one’s duty and obligations often leads to feelings of guilt. The feeling of shame is associated with negative judgments about one’s self and a negative sense of self (Thrane 1979, Hultberg 1988, Babcock & Sabini 1990). Shame refers to the feeling of loss of standing in the eyes of oneself or his significant others because of a failure to fulfil his expected role or status (Bedford & Hwang 2003), a failure to achieve a desired self-image (Creighton 1988), a failure to live up to an ego ideal (Piers & Singer 1953, Kaufman 1989), or the internalization of a negative ideal (Lindsay-Hartz 1984). The difference in the self-concept between North Americans and Chinese may contribute to a different understanding of shame (Bedford & Hwang 2003). Hwang (2001) states that shame in Confucian cultures refers in particular to a failure to fulfil positive duties and obligations. In addition, failing to maintain one’s identity in the social hierarchy can contribute to the feeling of shame. It has been found that shame can provoke damage to the individual and to social relationships.

To summarize, it is clear from the various accounts that interpersonal dynamics are central to the Chinese self-concept and how the self is negotiated and self-image regulated. Deviations in interpersonal dynamics appear to be relevant to the experience of distress and may contribute to perceptions of psychopathology. The Chinese cultural heritage considered as a determinant of psychopathology was based on the studies of epidemiological research. Very few studies examined how traditional Chinese culture played a role in influencing to develop a mental illness from the interpretations of the patients with their problems diagnosed as a mental illness in mental health services. The aim of this study is to explore Chinese mental health patients’ and their

caregivers’ interpretations of how traditional Chinese cultural values influence their experiences of suffering.

Methods

This phenomenological study applied reading response the-ory to implement the narrative construction of experiences of suffering of Chinese patients with mental illness. Ricoeur (1981) described that ‘reading response’ theorists have elaborated on the temporal and intersubjective qualities of all narrative by giving special attention to the ‘phenomenol-ogy of the act of following a story’ (p. 277). Good (1994:139) explained that ‘narrative is a form in which experience is represented and recounted, in which events are presented as having a meaningful and coherent order, in which activities and events are described along with the experiences associ-ated with them and the significance that lends them their sense for the persons involved.’ The experience of suffering organized in narrative form can help illustrate how narratives emerge within the frames of cultural values (Kleinman 1988). This study used narrative theory to explore the structure of narratives amongst case stories and investigate what the patients and their caregivers revealed about the impact of traditional Chinese cultural values on their mental states.

Subjects

Twenty-eight patients and 28 caregivers – all of whom lived in Melbourne, Australia – were interviewed together making a total sample of 56. The criteria for inclusion of patients were diagnosed with mental disorder; over 18 years of age; and able to speak a Mandarin language. Each patient’s main caregiver was recruited for the study. Two patients were recruited from two traditional Chinese medicine practitioners through the use of the Patient Screen Checklist, which is based on the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) and the Structured Clinical Interview. Their problems were diagnosed by their psychiatrists as mental illness. The rest of the participants were recruited from four private Chinese-speaking psychiatrists. At the time of the study, all participants received their psychiatrists’ treatments in outpatient clinics. The PRIME-MD has been used to screen for common disorders in primary care. The reliability and validity of this scale has been well established (Spiltzer et al. 1994, Van Hook et al. 1996). The Structured Clinical Interview has been widely used to determine psychiatric diagnosis of participants (Spiltzer et al. 1992, Ressler et al. 2004). Forty-six percent of patients and 61% of caregivers were male. The average of age was 45 years for caregivers and 46 years for patients. Fifty-three percent of caregivers and 46 of patients had received higher education at

the tertiary level. No caregiver but one patient was employed in jobs requiring higher education.

Procedure

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the University of Melbourne Ethics Committee. The psychiatrists and the traditional Chinese medicine practitioners provided a bro-chure to patients and family members. The brobro-chure contained information about the study and invited partici-pation from families. When potential subjects were interested in participating in the project, the researcher explained the purpose and nature of the study to family members and patients, and then invited them to participate as subjects. The patients and their caregivers were asked to give their written consent before the interview began. The researcher conducted the interviews in Mandarin in each family’s home. The interviews were recorded on cassette tape (with the permis-sion of the subject) and via hand-written notes, and the interviews were later transcribed, translated and analysed.

Data analysis

Reading response theory influenced the narrative analysis of each interview. For example, Good (1994) used the analytic method of reader response theory to analyse illness stories. He proposed three analytic concepts: the ‘emplotting,’ the ‘sub-junctivizing’ and the ‘positioning of suffering.’ ‘Emplotting’ refers to the process of uncovering a plot as the underlying structure of a case story. A prototypical plot emerges as a distinctive cultural form amongst illness narratives. The concept of ‘subjunctivizing’ refers to the process of identifying the multiple perspectives and interpreting potential outcomes in illness narratives. ‘Positioning of suffering’ refers to the process of examining the meanings of suffering in everyday life. For the present study to arrive at a reasonably faithful representation of the stories presented to the researcher, the following steps were exercised: (1) uncover the story struc-ture and identify the prototypical plot types, (2) identify the relationships amongst the conceptual categories (themes), (3) identify contrasting and complementary perspectives and (4) establish the validity of meanings carried by the observed conceptual categories (by cross-situation/respondent/narrator replication).

Results

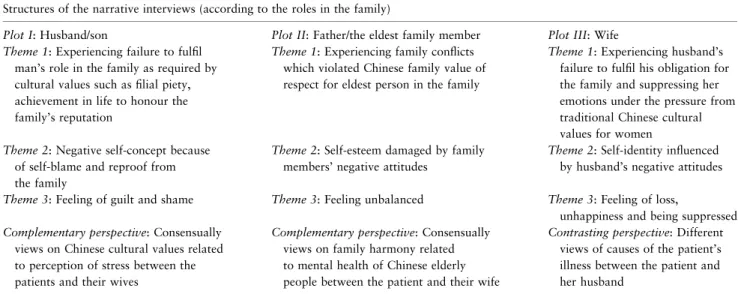

The identified plot types, themes and contrasting and complementary perspectives under each plot type are shown in Table 1.

1. Uncover the story structure and identify the prototypical plot types

As shown in Table 1, in examining the narratives, three types of narrative plots could be identified amongst 28 case stories according to the roles in the family. These roles included the husband/the son to be responsible for raising the family and protecting the family’s reputation, the father/the eldest family member to be respected by the family members, and the wife to show obedience to her husband and mother-in-law. Twenty-eight case stories fell into different plots: 15 for Plot I; one for Plot II and 12 for Plot III.

2. Identify the relationships amongst themes

Prototypical plot types were also examined to identify themes. As shown in Table 1, there were three common themes under each plot type identified in this study. These themes were causally related. For example, for Plot I, three themes demonstrated that external stresses led men not to be able to adjust to their familial roles as required by social norms and cultural values. Hence, self-blame and reproof from the family contributed to the patient’s negative views of self and their emotional responses and the patients’ failure to cope with the situations. For Plot II, the themes described how traditional Chinese values’ emphasis on family harmony and the respect for eldest person in the family interrupted the patient’s psychosocial homeostasis. For Plot III, the themes demonstrated that the Chinese female patient’s negative view of self and negative emotions was influenced by her husband failing to fulfil his obligation to the family and the lack of support from her husband and her mother-in-law. Confucian

values of obedience and submission for women appeared related to her suppression of her emotions.

3. Identify the contrasting and complementary perspectives

The juxtaposition of contrasting and complementary per-spectives of the patients and the family members was also evident in the case stories. For Plot I, the patients and their wives both thought that traditional Chinese cultural values emphasizing the men’s role in the family influenced the patients to perceive stress as an adverse situation and to view themselves negatively. For Plot II, the patient and his wife consensually attributed the patient’s distress to not being treated respectfully by family members. For Plot III, the patient and her husband held different views of the causes of the patient’s problem. The patient thought that her husband’s affair with another woman was the main cause of her distress while her husband thought that the patient’s failure to fulfil her responsibility for the family was the root of her unhappiness.

4. Establish the validity of meanings carried by the observed conceptual categories

In the present study, validity and reliability was achieved by verification of themes that organized the researcher’s obser-vation. Validity requires qualifying lay people’s interpreta-tions of their situainterpreta-tions in relation to their local world (Kleinman 1994). The researcher construed the themes based on examining the patients’ and their caregivers’ subjective interpretations of the impacts of traditional Chinese cultural

Table 1 Plots, themes and contrasting or complementary perspectives identified from the narrative interviews Structures of the narrative interviews (according to the roles in the family)

Plot I: Husband/son Plot II: Father/the eldest family member Plot III: Wife Theme 1: Experiencing failure to fulfil

man’s role in the family as required by cultural values such as filial piety, achievement in life to honour the family’s reputation

Theme 1: Experiencing family conflicts which violated Chinese family value of respect for eldest person in the family

Theme 1: Experiencing husband’s failure to fulfil his obligation for the family and suppressing her emotions under the pressure from traditional Chinese cultural values for women Theme 2: Negative self-concept because

of self-blame and reproof from the family

Theme 2: Self-esteem damaged by family members’ negative attitudes

Theme 2: Self-identity influenced by husband’s negative attitudes Theme 3: Feeling of guilt and shame Theme 3: Feeling unbalanced Theme 3: Feeling of loss,

unhappiness and being suppressed Complementary perspective: Consensually

views on Chinese cultural values related to perception of stress between the patients and their wives

Complementary perspective: Consensually views on family harmony related to mental health of Chinese elderly people between the patient and their wife

Contrasting perspective: Different views of causes of the patient’s illness between the patient and her husband

values on mental health. Subjective interpretations amongst all participants were compared in terms of the meanings given by subjects, context and relationship with the social and cultural context.

The following case stories demonstrate the specific findings that emerged from the analytic process. All names used in the stories are pseudonyms.

Plot I: Chinese adult male patients as the husband and the son

Mr Wu had suffered from agoraphobia with panic attacks for over a decade. He recalled his life and explained that because fulfilling achievement in life to honour the family’s reputation was highly valued in Chinese societies, he had worked very hard to pursue a high social status. His effort paid off and he became a manager who controlled a great resource in southern China. However, his personal identity was chal-lenged upon migrating to Australia. In Australia, he began work as a laborer and was ordered by his employer to do a lot of ‘dirty’ work, such as cleaning dishes. He had difficulty in coping with this situation. He appeared to have physical discomfort and gradually became afraid of going out. His wife blamed him for not being tough enough to overcome his fear and she also devalued him by saying, ‘you are useless.’ (Female caregiver 1) The patient reported that his parents’ visit to Australia made his condition worse. This was because ‘I felt more uncomfortable when they mentioned how successful our neighbours were in China. Compared with them, my situation here is very worse now.’ (Male patient 1) He felt ‘nei jiu’ (guilt) for his family’s suffering because of his illness.

The patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and their wives explained that Chinese cultural values influenced the patients’ perceptions of stress arising from their workplace injuries. Such cultural values were all related to the Chinese family and included the man’s role in the family, filial piety and an individual’s honour related to the family’s honour. For example, Mr Wang’s wife said that:

I know that he feels uncomfortable. You know that in Chinese society, the man is the leader in the family and the man should raise the family. But now his mother and I look after him. He cannot stand this…. He is a man so his self-esteem is very important…. Now he feels that he is a man but that he makes trouble for the family and so he feels sad and nei jiu (guilt)… (Female caregiver 5).

For another subject, Mr Wong’s emotional distress was a result of not fulfilling the cultural expectation of filial piety. As a result, his self-blame and the reproof from his parents

conflicted with his self-concept and this contributed to his feeling of shame. He stated:

When I called my mother, my mother cried on the phone and said that ‘you are not our son.’ I come from Shangdong. You know, compared with other provinces in China, people in Shangdong place more value on filial piety. They (parents) cannot understand my situation in Australia but I still need to call home…. When I wrote a letter, I just wrote that everything was all right…. Their son never sent any money to them. What could they think of me? I have been in this situation for two-and-half years. I stayed at home all day and this is like living in a jail…. I miss home and my parents. If I were not injured, I would have sent much money to my mother in the last four years to let them enjoy life. As a son, I could have performed this, and I would have felt very good…’ (Male patient 11).

Plot II: Chinese elderly male patient as the father and the eldest family member

Mr Yu had suffered from depressive disorder over 30 years ago because he had been traumatized and was physically and mentally tortured from the conditions of the Cultural Revolution. He attributed his recovery to the joy of being with his grandson rather than the psychiatric medication. However, he suffered a relapse in Australia. He and his wife attributed his illness to the actions of a remote relative who destroyed the harmony of the family and had alienated their son-in-law from them. The husband, as the eldest in the family, was not treated with respect by his son-in-law and he was even ordered to do things by his son-in-law’s nephew. The husband reported that:

When he (the nephew) lived with us, he ordered us to do this and that. He even wanted us to buy him cigarettes…. His terrible attitude towards us made my problem relapse. I felt very unbalanced. Before this, the atmosphere in our family was harmonious. Nevertheless, after he split our family, my daughter and son-in-law wanted to divorce. He made our family disturbed. (Male patient 3).

Plot III: Chinese adult female patient as the wife and the daughter-in-law

Ms Lin, suffering from major depression, perceived herself as a traditional Chinese woman whose personal identity and happiness were embedded in the family. She said that:

I am a very traditional woman. Speaking of social values, I am family oriented. When he (husband) pursued his career, I took care of the family. I felt happy, despite we not having much money at that time. The root of my happiness is from the family… (Female patient 29).

She attributed her emotional distress to her husband having an affair with another woman. She could not express her distress openly, as she felt that her husband was like a ‘hood’, which covered her head. In addition, this was because her husband and her mother-in-law blamed her and did not follow the social norm of ‘knowing renqing (human affect)’ to understand and provide their support to her. She recalled that:

Last time he and his family celebrated the Chinese New Year together while leaving my son and me here. I asked my son to call his father at home. But, we did not have a nice talk and he hung up the phone. I kept calling him about five or six times. His mother blamed me. She did not understand my situation. What she did to me showed that she was the kind of person who did not know renqing (Female patient 29).

Her husband thought that the wife’s low social status in Australia had been threatening her self-esteem, as the patient was concerned with mientze (face, representing a person’s social status in the society). In addition, he explained that the root of happiness was to fulfil a person’s responsibility in the family. This explained why Ms Lin felt depressed. He said:

I mean to be a human, you have responsibility and you do not live only for yourself, but also for other people. You do what the family expects you to do. If you do not take your responsibility and do not do your best for everything, of course, you will not feel satisfied. She is only concerned about herself so she feels unhappy… (Male caregiver 29).

The husband of Ms Lee, suffering from schizophrenia, thought that because of the complicated relationships in a big Chinese family, the patient had difficulty in dealing with the situation. In addition, her capacity to deal with difficulty was impeded by her never having gone to school to gain the education that would have fulfilled her, particularly as being the eldest daughter, and her responsibility to the family. He said:

When I was in China, I was the eldest son in the family and I took all the responsibility and I decided everything for the family…. After I left China, many things happened in the family and she could not deal with the situation… (Male caregiver 15).

Discussion

The phenomenon of suffering emphasizes the patients and families’ interpretations of the situation and their experiences of distress (Kleinman 1988). Kleinman illustrates that culture shapes experiences of suffering because people learn the way to think about their stress, how to respond with the

appropriate emotions and how to act as expected in the local cultural and social context. The study illustrated that cultural rules govern people’s interpretations of what types of stressors are the most adverse and how loss should be responded to. For example, the study suggests that because Confucianism thought emphasizes interpersonal harmony, interpersonal stimuli were perceived by Chinese people as the principle source of stress. Interpersonal stress arises when Chinese patients’ behaviour deviates from the cultural norm and they do not meet their roles as required by Confucian thought.

Confucians define roles according to the five major dyadic relationships that influence how patients and family members judge if a patient’s behaviour is appropriate (Hwang 2000). In the Chinese hierarchical structure, men are the heads of families, hold more power and are expected to take more responsibility than those in lower positions. In the present study, the patients and the family members indicated that when male patients failed to fulfil their obligation as the head of the family, their personal identity was threatened by blame from themselves, their family members and their friends for that failure. This blame diminished their self-worth and increased their sense of loss. Consequently, they felt a sense of guilt and shame. This finding is supported by Bedford and Hwang’s study (2003) suggesting that in Chinese society an individual’s personal identity is embedded in the social network and is dependent upon the appropriate behaviour in his social role.

This study showed that when Chinese patients, as children, failed to achieve success and bring honour to the family, they viewed themselves as bad sons or daughters – children who could not live up to the values of filial piety. This may be because Chinese children are brought up to pay great concern to their own and their family’s honour and reputation (Ji et al. 2001). Consonant with the influence of Confucian philoso-phy, one’s ‘face’ is a collective concept. ‘Loss of face’ not only reflects on the individual patient, but also on families and their ancestors (King & Bond 1985). A ‘loss of face’ is a threat to the homeostasis of the family. This study illustrated that the patients’ negative perception of themselves as a result of transgressed personal identity and family reputation led them to feel, guilt, shame, hopelessness and disappointment.

Zhang et al. (1997) revealed that family conflicts, especially verbal abuse which violates socio-cultural family values, were frequently associated with depression amongst Chinese people. The present study indicated that Chinese older people’s strong belief in traditional Chinese family values influenced them to regard the stress arising from family conflicts as the worst sort of stress and, as a result, this kind of stress had a particularly negative impact on

their experiences of depression. Kua (1989) suggests that traditional Chinese values emphasizing filial piety and family support for older people might be correlated to the low prevalence of depression amongst Chinese elderly. Phillips and Pearson (1997) argue that Confucian values, emphasizing the family as central to the management of life’s problems, influence Chinese people to regard the lack of the family’s support as an important cause of psycho-logical distress. The findings of Phillips and Pearson (1997) also suggest that the patients’ psychological distress emerged when the patients did not receive their family members’ support according to the idea of knowing ‘renqing.’ The Chinese cultural concept of ‘knowing renq-ing’ – meaning that people can understand and empathize with other’s emotions – is seen as an appropriate social behaviour (Hwang 1987). Saving mianzi (face) for someone else demonstrates that a person ‘knows renqing’ because mianzi, presenting a person’s social position and prestige, is regarded as essential to Chinese people. The strategy commonly used to protect people’s face is to avoid criticizing them, especially superiors, in public. In this study, people’s socially unsanctioned behaviours towards the patients were thought to be related to the patients’ experiences of distress.

Bernard (1976) and Horwitz et al. (1996) demonstrate that women are socialized to be ‘other-oriented’. That is, women tend to have a great concern for interpersonal relationships. The present study reveals that the Chinese relational self contributes to traditional Chinese women’s concern about others, especially their families. Moreover, in the hierarchical family system, traditional Chinese women’s positive emotions rely upon each family member’s fulfilment of their obligations for the family’s integrity. Therefore, women are more vulnerable to the stresses of deprivation of interpersonal ties and, as a result, to depression. Desjarlais et al. (1995) also notes that in the developing world, a ‘relatively powerless’ social status is one of the risk factors that can lead women to suffer from depression. In addition, suppression of emotions was found to be relevant to the Chinese women’s experiences of suffering. Pearson et al. (2002) suggests that suicidal women are often vulnerable in dealing with relationships because they experience difficulty in expressing their anger in a rigid social and family structure. The present study illustrates that the Confucian value of obedience and submission of traditional Chinese women in relation to men may play a crucial role in the restriction of emotional expression. Outwardly aggressive behaviour that breaks the harmonious interpersonal relationship is seen as inappro-priate in Chinese societies (King & Bond 1985). This value

that prescribes what constitutes appropriate behaviour in social situations influences Chinese women’s expression, or suppression, of their negative emotions – emotions not sanctioned in Chinese families.

The results of this study suggested that understanding patients’ suffering that was shaped by traditional cultural values would help nurses express empathy in a culturally sensitive manner. Through empathy, nurses are able to understand the meanings of patients suffering and to com-municate their caring with patients more effectively (Carson 2000). However, culturally sensitive empathy has not been clearly identified in nursing and this may lead nurses to have difficulty in understanding the meanings of the inner struggle of patients from different cultural background. Cultural empathy has been defined as ‘seeing the world through another’s eyes, hearing as they might hear, and feeling and experiencing their internal world, which does not involve mixing ones own thoughts and actions with those of the client’ (Ivey et al. 1993). Nurses can be culturally empathic through recognizing and accepting patients’ cultural values and beliefs. For example, this study and Chung et al.’s study (2002) found that knowledge of cultural issues related to family, the concept of filial piety social role, obligation, loss of face and shame helped recognize the impacts of traditional cultural values on Chinese patients’ experiences of suffering. Both studies demonstrate that therapy emphasizing patients’ autonomy may be culturally insensitive because the Chinese concept of self is embedded in social relationships and is influenced by cultural expectations of appropriate roles. Chinese patients suffered from interpersonal disharmony because of their failure to fulfil cultural expectations of appropriate behaviours particularly in their family roles. Nurses can express cultural empathy through demonstrating understanding of the cultural issues related to patients’ distress.

Limitations

The small sample size (28 families) raises questions regarding how the representative views of the sample are with respect to the majority of Chinese–Australians with mental illness. The lack of representation of subjects, who were aged less 30 years, were second or subsequent generations of immi-grants and were young at the time of migration might limit to understanding of the impacts of Confucian thought on such groups. Those who are younger and younger at the time of migration are likely to have different educational experiences, which might expose them to Western concepts of mental health and social relationships than those who are older and older at migration.

Conclusion

The results of the present study suggest that Chinese people’s emotional suffering in the presence of mental disorder is influenced by their cultural emphasis on interpersonal roles and relationships. Psychotherapy, which aims to understand the impact of cultural values on the development of interpersonal conflicts and on the sense of guilt and shame in order to restore the harmony of interpersonal relation-ships, may need to be provided for Chinese patients and their family members.

The study’s implication for nursing practice relates to the need for cultural empathy, which is built on understanding the complex roles underpinning interpersonal behaviours in Chinese culture. Examining the Chinese patients’ experiences of suffering helps, nurses understand how suffering is shaped by culture. To be culturally empathic, nurses need to have a cultural understanding and the ability to identify the cultural elements of interpersonal harmony – elements such as filial piety, loss of face, guilt or shame. The nurses’ expressions of cultural empathy help them to be able to feel as their patients feel and thereby respond appropriately to their patients’ needs.

Contributions

Study design: FHH, SK; data analysis: FHH, SK, EST, HM; manuscript preparation: FHH, SK, HM, EST.

References

Babcock M & Sabini J (1990) On differing embarrassment from shame. European Journal of Social Psychology 20, 151–169. Bedford O & Hwang KK (2003) Guilt and shame in Chinese

culture: a cross-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. Journal for the Theory of Social Beha-viour 33, 125–142.

Bernard J (1976) Homosociality and female depression. Journal of Social Issues 32, 213–238.

Bond MH (ed.) (1986) The Psychology of the Chinese People. Oxford University Press, Hong Kong.

Carson VB (2000) Mental Health Nursing: The Nurse–Patient Journey, 2nd edn. W.B. Saunders Company, Pennsylvania. Cheng TA (1988) A community study of minor psychiatric

morbid-ity. Psychological Medicine 18, 953–968.

Chung RCY, Bemak F & Kilinc A (2002) Culture and empathy: case studies in cross-cultural counselling. In Dimensions of Empathic Therapy (Breggin PR, Breggin G & Bemak F eds). Springer Pub-lishing Company, New York. pp. 119–128.

Creighton M (1988) Revisiting shame and guilt culture: a forty-year pilgrimage. Ethos 18, 279–307.

DeRivera J (1984) The structure of emotional relationships. Review of Personality and Social Psychology 5, 116–144.

Desjarlais RL, Eisenberg B, Good B & Kleinman A (1995) World Mental Health. Oxford University Press, New York.

Good B (1994) The narrative representation of illness. In Medicine, Rationality, and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective (Good B, ed.). Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 135– 165.

Horwitz AV, White HR & Howell-White S (1996) The use of mul-tiple outcomes in stress research: a case study of gender differences in responses to marital dissolution. Journal of Health Social Behavior 37, 278–291.

Hsu FLK (1971) Psychological homeostasis and jen: conceptual tools for advancing psychological anthropology. American Anthropol-ogist 73, 23–44.

Hultberg P (1988) Shame: a hidden emotion. Journal of Analytical Psychology 33, 109–126.

Hwang KK (1978) The dynamic processes of coping with interper-sonal conflicts in a Chinese society. Proceedings of the National Science Council (Taiwan) 2, 198–208.

Hwang KK (1987) Face and favor: the Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology 92, 944–974.

Hwang KK (2000) Chinese relationalism: theoretical construction and methodological considerations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30, 155–178.

Hwang KK (2001) The deep structure of Confucianism: a social psychological approach. Asian Philosophy 11, 179–204. Ivey AE, Ivey MB & Simek-Morgan L (1993) The empathic attitude:

individual, family and culture. In Counselling and Psychotherapy: A Multicultural Perspective, 3rd edn (Ivey A, Ivey M & Simek-Morgan L eds). Allyn & Bacon, Boston. pp. 23–49.

Ji JL, Kleinman A & Becker AE (2001) Suicide in contemporary China: a review of China’s distinctive suicide demographics in their sociocultural context. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 9, 1–12. Kaufman G (1989) The Psychology of Shame: Theory and Treatment

of Shame-Based Syndromes. Springer, New York.

King YC & Bond MH (1985) The Confucian paradigm of man: a sociological view. In Chinese Culture and Mental Health (Tseng WS & Wu YH eds). Academic press, London, pp. 29–45. Kleinman A (1980) Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture:

An Exploration of the Bordeland Between Anthropology, Medi-cine, and Psychiatry. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. Kleinman A (1988) The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing and the

Human Condition. Basic Books, New York.

Kleinman A (1994) An anthropological perspective on objectivity: observation, categorisation, and the assessment of suffering. In Health and Social Change in International Perspective (Chen LC, Kleinman A & Ware NC eds). Harvard University press, Boston. pp. 129–138.

Kua E (1989) Depressive disorder in elderly Chinese people. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 81, 386–388.

Lin TY, Tseng WS & Yeh EK (1995) Chinese Societies and Mental Health. Oxford University Press, New York.

Lindsay-Hartz J (1984) Contrasting experiences of shame and guilt. The American Behavioral Scientist 27, 689–704.

Murphy JM & Leighton AH (1965) Approaches to Cross-Cultural Psychiatry. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Pearson V, Hil DP & Liu M (2002) Ling’s death: an ethnography of a Chinese women’s suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 32, 347–358.

Phillips MR & Pearson V (1997) Coping in Chinese communities: the need for a new research agenda. In The Handbook of Chinese Psychology (Bond MH ed.). Oxford University Press, Hong Kong, pp. 429–440.

Piers G & Singer M (1953) Shame and Guilt. International University Press, Springfield, IL.

Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, Anderson P, Graap K, Zimand E, Hodges L & Davis M (2004) Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of d-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Archives of General Psychiatry 61, 1136–1144.

Ricoeur P (1981) Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences. Edited and translated by John B. Thompson, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Singh PN, Huang SC & Thompson CW (1962) A comparative study of selected attitudes, values, and personality characteristics of American, Chinese, and Indian students. Journal of Social Psy-chology 57, 123.

Spiltzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M & First MB (1992) The struc-tured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry 49, 624–629.

Spiltzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K & Linzer M (1994) Utility of a new procedure of diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 272, 1749–1756.

Tarwarter JW (1966) Chinese and American student’s interpersonal values: a cross-cultural comparison. The Journal of College Student Personnel 7, 351.

Thrane G (1979) Shame and the construction of the self. The Annual of Psychoanalysis 7, 321–341.

Tseng WS & McDermott JF (1981) Alcohol-related problems. In Culture, Mind and Therapy: An Introduction to Cultural Psy-chiatry (Tseng WS & McDermott JF eds). Bruner/Mazel, New York, pp. 73–87.

Van Hook MP, Berkman B & Dunkle R (1996) Assessment tools for general health care settings: PRIMD-MD, OARS, and SF-36. Health Social Work 21, 230–234.

Zhang AY, Yu LC, Yuan J, Tong Z, Yang C & Foreman SE (1997) Family and cultural correlates of depression among Chinese elderly. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 43, 199–212.