Hysterectomy is one of the most frequently per-formed operations in Taiwanese women, second only to cesarean section.1Previous studies have shown that most women received hysterectomy due to nonmalignant symptoms such as men-strual pain, menorrhagia, unexplained uterine bleeding and chronic pelvic pain.2–5All of these

symptoms have an adverse effect on a woman’s quality of life. Most women reported a reduc-tion in physical symptoms and pain and an in-crease in health perceptions after hysterectomy.4 However, hysterectomy may also result in the development of new problems such as pelvic/ abdominal pain, urinary problems, constipation,

©2006 Elsevier & Formosan Medical Association . . . . School of Nursing, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, 1National Health Research Institutes, and2School of Psychology,

College of Science, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received: April 25, 2005 Revised: June 2, 2005 Accepted: March 7, 2006

*Correspondence to: Dr Ya-Ling Yang, School of Nursing, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, 1 Jen Ai Road, Section 1, Taipei 100, Taiwan.

E-mail: ylyang@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw

Changes and Factors Influencing

Health-related Quality of Life After

Hysterectomy in Premenopausal Women

with Benign Gynecologic Conditions

Ya-Ling Yang,* Yu-Mei Chao,1Yueh-Chih Chen, Grace Yao2

Background/Purpose: A hysterectomy affects a woman’s health. This study was performed to identify the factors that affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL) before and after hysterectomy in premenopausal w

women.

Methods:This prospective follow-up study recruited 38 women (age range, 33–52 years) who underwentt abdominal hysterectomy for nonmalignant causes. SF-36 and self-rated health status were used to assess HRQoL before and after hysterectomy. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, nonparametric tests and the generalized estimating equation method for modeling the repeatedly measured responses. Results: Patients’ attitudes toward hysterectomy and subsequent sexual activity were influenced by the sur-gery. All patients showed significant improvements in the physical component summary (PCS) of SF-36 (mean, 42.1–51.0), but there was no significant difference in the mental component summary (MCS). The significant improvements were found from the five repeated measurements of the self-rated health status (mean, 6.0–7.3). Hemoglobin level was the most important predictor of HRQoL before surgery. Women in employment, with more years of education and previous blood transfusion had high MCS scores after surgery. Conclusion: The overall self-rated health status and PCS showed significant improvements after hysterec-tomy. Having had a blood transfusion, being educated and employed were positively associated with MCS score after surgery. These findings are vital for preoperative counseling for women undergoing hysterectomy. [J Formos Med Assoc 2006;105(9):731–742]

Key Words: abdominal hysterectomy, generalized estimating equation modeling, health-related quality of life, SF-36

w

weight gain, fatigue, lack of interest or enjoyment in sex, depression, anxiety and negative feelings about oneself as a woman.2,3 Women who had higher depression scale scores prior to hysterec-tomy expressed more fears of aging, weight gain and loss of femininity.6Femininity has been pro-posed as a positively valued quality, thus, the perception of losing one’s femininity is a serious and threatening event in a woman’s life.7 There-fore, hysterectomy may function as a stressor, adding to the general dissatisfaction with life or triggering preexisting health problems. Due to the rate of complications and mortality after hys-terectomy, and the significant number of surger-ies that do not relieve pain, nonsurgical therapy may be more appropriate initially. When nonsur-gical management fails,3 however, hysterectomy can be performed to treat nonmalignant condi-tions, hopefully enhancing the quality of life and relieving discomfort.4,5 The only hysterectomy characteristic that was significantly associated w

with poor outcome was bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO). BSO, rather than hysterec-tomy, may be associated with mild increases in depression scores.8In comparison with women w

without oophorectomy or with unilateral oophorectomy, women with BSO had signifi-cantly lower scores in energy, pain and general health change on the SF-36 4 months after hys-terectomy.9 Hot flashes were a more frequent adverse event in women who had BSO, but the procedure type (BSO vs. no BSO) did not have a significant influence on quality of life indices.2In Maryland study, it was found that hysterectomy w

was not an effective treatment for all women. Baseline depression and therapy for emotional problems were significantly associated with poor outcome. Some of these women who had changed in life circumstances were associated with posthys-terectomy depression, but it is also possible that for some, hysterectomy instigated depression.10 However, research has shown no evidence link-ing the removal of the uterus to psychologic disturbances.11

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has been increasingly recognized as an important

outcome variable in clinical research, in addition to the more traditional biomedical measures.12 HRQoL is a multidimensional concept, which encompasses physical, emotional and social as-pects associated with a given disease or its treat-ment.13 Also, HRQoL refers to an individual’s total wellbeing, an important concept for gyne-cologic medical and nursing staff to understand in order to provide patients with accurate infor-mation during pre- and postsurgical counsel-f ing, thereby enhancing the appropriateness of f treatment and care. Several recent studies of hysterectomy outcome in Taiwan have shown improvements in HRQoL or at least short-term effectiveness after the procedure.

Two basic approaches characterize the meas-urement of HRQoL: generic instruments (includ-y ing single indicators, health profiles and utility measures) and specific instruments. A health profile is an instrument that attempts to measure all important aspects of HRQoL.14The SF-36 is an example of such an instrument that was con-structed to survey health status and to apply the findings to clinical practice and research, health policy evaluations and general population sur-vey.15 Utility measures of quality of life are the other type of generic instrument, which is sum-marized as a single number along a continuum scale of the net change in HRQoL. Utility meas-ures are useful for determining if patients are, overall, better off, but they do not show the do-mains in which improvement or deterioration oc-curs. The instruments used to assess HRQoL mayy be specific to a disease, patient population, cer-tain function or problem. Specific measures have y the advantage of relating closely to areas routinely analyzed by clinicians.14Most previous research used the SF-36, a generic instrument, to measure HRQoL in women who have undergone hysterec-tomy.10,15–18Ideally, the instruments used should comprise a generic and disease-specific question-c naire so that comparisons can be made at a generic level and specifically to that disease or condition.19 In a review of the literature, Jones et al20 found that 26% of the tools used to measure HRQoL in women with benign gynecologic conditions were

not based on established psychometric proper-ties and, therefore, were inappropriate for the measurement of HRQoL. However, a specific in-strument for the assessment of HRQoL in women w

with benign gynecologic disorders who undergo hysterectomy has yet to be developed.20The pur-poses of this study were as follows: (1) to deter-mine if women’s perceived HRQoL improved after hysterectomy; (2) to investigate what aspects of HRQoL are affected by hysterectomy during the recovery period; (3) to examine the relation-ship between women’s self-rated health (utility measures) and HRQoL; and (4) to assess the fac-tors influencing HRQoL during the year after hysterectomy.

Methods

TThis was a prospective follow-up study. A sample of 40 women undergoing hysterectomy for non-malignant reasons was enrolled. The sample size required for this study was determined based on the following assumptions. The probability of a type I statistical error (two-sided) is 0.05 and of a type II statistical error is 0.10. Under the difference of hypotheses not less than 0.6 standard deviation σ, the sample size of this test is approximately 36. T

The process of data collection combined with interview methods was used to validate the data interpretation and to control the measurement errors. The participants had regular menstrual cycles, and were scheduled for abdominal hys-terectomy, either with or without BSO. The final sample used in the data analysis comprised 38 w

women (mean age, 44.6± 6.1 years; range, 33–59 y

years), all of whom completed 1 year of postop-erative follow-up.

During a preoperative visit after recruitment, the informed consent form was signed by all par-ticipants. Each participant received a self-rated health questionnaire and completed it five times (before and immediately after surgery, and 1, 6 and 12 months postsurgery). The SF-36 Health Survey was completed by the participant on three different occasions (before surgery, and 6 and

t 12 months after surgery). Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Human Subjects Committee of National Taiwan University Hospi-tal. To ensure participant anonymity and confiden-tiality, an identification number was assigned to each woman in place of her name. Questionnaires were also coded using identification numbers.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages provided a general description of sample char-acteristics. Nonparametric tests such as the t Wilcoxon signed rank test and Friedman’s test were used to examine the effect of time on HRQoL and self-rated health status. The general-ized estimating equation (GEE)21,22 method forr modeling the marginal means of longitudinal data was used to examine the effects of the fac-tors on subjects’ physical and mental HRQoL be-fore, and at 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy. y Due to the relatively small sample size, a normality assumption was made on the response variables f to obtain the maximum likelihood estimates of the regression coefficients, and the model-based variances of the regression coefficient estimates (according to the chosen AR(1) correlation struc-ture for the response errors) were used. Given the relatively small sample size, any statistically signif-icant findings deserve further attention. Backward t variable selection, goodness of fit assessment and basic regression diagnostics were conducted. A two-tailed significance level of 0.05 was used in all statistical tests.

Self-rated health questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by the investi-gators to gather subjective information from par-ticipants about their health and concerns before surgery and during the recovery period. Data col-w lection was performed using personal interview in order to obtain the participants’ perception at specific times. All the interview data were collected by one well-trained interviewer. The questionnaire covers four parts: (1) the patient’s attitudes and emotional reactions to having and

not having a uterus; (2) the patient’s concern with their current health problems; (3) the patient’s perceived interest or enjoyment in sex after hys-terectomy; and (4) the patient’s self-rated health status. Patients pointed out their subjective per-ceptions using a single-item numeric rating scale of 1–10. The clinical data were obtained from each patient’s medical records. The relevance of the content of the questionnaire was verified through a review of the literature and by a panel of expert nurses and gynecologists.

SF-36 Health Survey T

The SF-36 Health Survey measures generic health concepts that assess HRQoL outcomes.23 The T

Taiwan version of the SF-36 Health Survey ap-pears to be a practical and reliable instrument for use in the general population.24The SF-36 meas-ures eight health concepts: (1) physical function-ing (PF); (2) role limitations due to physical health problems (RP); (3) bodily pain (BP); (4) general health (GH); (5) vitality/fatigue (VT/FT); (6) so-cial functioning (SF); (7) role limitations due to emotional problems (RE); and (8) mental health (MH). The SF-36 was constructed to represent two major dimensions of health—the physical com-ponent summary (PCS) and the mental compo-nent summary (MCS).25 A second-order factor analysis (principal component analysis) of the eight SF-36 scale scores was carried out to test the assumption that there were two underlying fac-tors in the SF-36. Two facfac-tors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted and rotated to an orthogonal simple structure using the varimax method,25which accounted for 81.5% of reliable v

variance in SF-36 scales.26 Reliability estimates (Cronbach’s α) of the eight SF-36 (Taiwan ver-sion) scales met or exceeded the 0.7 level, with the exception of the SF scale (α = 0.57).24Linear transformations were performed to convert orig-inal scores (0–100) to a mean of 50 with a stan-dard deviation of 10.23Higher scores represented a perception of better health.

Permission to use the SF-36 Taiwan version w

was obtained from the principal investigator for the Taiwan team and the IQOLA project

director Dr JR Lu. The reliability estimates (Cronbach’s α) of the eight health concepts off SF-36 in this study were: PF= 0.95, RP = 0.98, BP= 0.92, GH = 0.88, VT/FT = 0.74, SF = 0.69, RE= 0.97, MH =0.74. The correlation coefficientt (r) ranged from 0.23 to 0.7 between the eightt health concepts.

Results

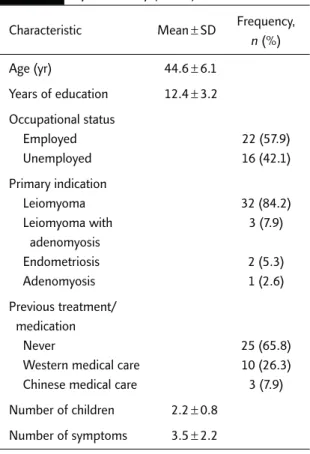

The most common primary condition in the par-y ticipants was leiomyoma (84.2%), followed by leiomyoma with adenomyosis (7.9%), endome-triosis (5.3%) and adenomyosis (2.6%), while menorrhagia (19.1%), abdominal pain (14.5%), blood clot (14.5%) and frequent urination (14.5%) were the main complaints. All partici-pants were married and premenopausal at the time of surgery. Patients’ demographic and clini-cal characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

of premenopausal women undergoing hysterectomy (n= 38)

Characteristic Mean± SD Frequency, n (%) Age (yr) 44.6± 6.1 Years of education 12.4± 3.2 Occupational status Employed 22 (57.9) Unemployed 16 (42.1) Primary indication Leiomyoma 32 (84.2) Leiomyoma with 3 (7.9) adenomyosis Endometriosis 2 (5.3) Adenomyosis 1 (2.6) Previous treatment/ medication Never 25 (65.8)

Western medical care 10 (26.3) Chinese medical care 3 (7.9) Number of children 2.2± 0.8

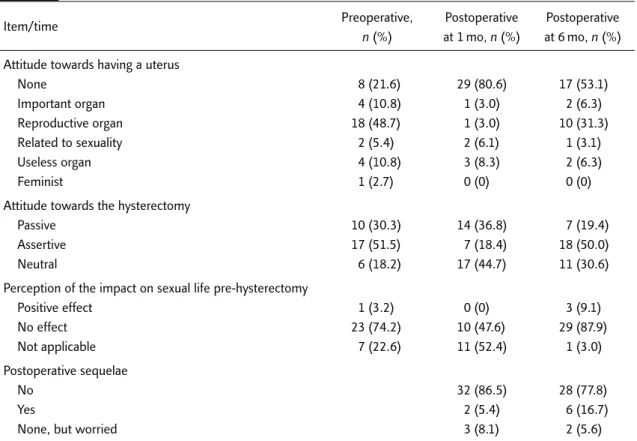

Out of 40 participants, 18 (48.7%) considered the uterus to be a reproductive organ since that is its general classification regardless of whether the w

woman is fertile before hysterectomy (Table 2). A

After hysterectomy, most of the patients expressed a feeling of detachment towards their uterus, and that it no longer represented something im-portant. Their attitude towards the hysterectomy shifted from passive (following doctor’s advice, feeling this was their only choice) or neutral (feel-ing indifferent) at 1 month after surgery, to as-sertive (a right choice) at 6 months after surgery. A

Attitudes toward hysterectomy and the resulting effect on their sex life differed greatly at 1 and 6 months postsurgery, with the latter results being more similar to the presurgery evaluation. This may be due to a miscomprehension of the changes and adaptive needs that a woman experiences after hysterectomy. While some participants cited w

wound healing and the need for additional time for adjustment as reasons for the delay of sexual activity, others had resumed their normal sexual life within 2 or 3 months after hysterectomy.

Sexual problems such as lack of orgasm, dyspare-unia and vaginal dryness were reported 6 months after surgery.

Significant differences in the PCS of SF-36 scores measuring the time effect were found between presurgery and 6 and 12 months post-surgery for three of the separately examined health concepts, role limitations due to physical g health problems being the exception. Measuring the time effect in the MCS of SF-36, only social functioning and role limitations due to emo-tional problems had significant differences between presurgery and 6 and 12 months post-surgery. There were no significant differences in health concepts between 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy. Similar findings were made in the analysis of results for the physical compo-nents of SF-36 (Table 3). Analysis of the inter-t view data supported that the participants felt much better at 1 month after surgery and contin-ued to feel better in the physical and emotional aspects of health at 6 and 12 months after sur-gery. There were no significant changes in the

Table 2. Attitude and perception toward hysterectomy before and after surgery

Item/time Preoperative, Postoperative Postoperative

n (%) at 1 mo, n (%) at 6 mo, n (%) Attitude towards having a uterus

None 8 (21.6) 29 (80.6) 17 (53.1) Important organ 4 (10.8) 1 (3.0) 2 (6.3) Reproductive organ 18 (48.7) 1 (3.0) 10 (31.3) Related to sexuality 2 (5.4) 2 (6.1) 1 (3.1) Useless organ 4 (10.8) 3 (8.3) 2 (6.3) Feminist 1 (2.7) 0 (0) 0 (0)

Attitude towards the hysterectomy

Passive 10 (30.3) 14 (36.8) 7 (19.4)

Assertive 17 (51.5) 7 (18.4) 18 (50.0)

Neutral 6 (18.2) 17 (44.7) 11 (30.6)

Perception of the impact on sexual life pre-hysterectomy

Positive effect 1 (3.2) 0 (0) 3 (9.1) No effect 23 (74.2) 10 (47.6) 29 (87.9) Not applicable 7 (22.6) 11 (52.4) 1 (3.0) Postoperative sequelae No 32 (86.5) 28 (77.8) Yes 2 (5.4) 6 (16.7)

participants’ overall HRQoL (SF-36) as a result of hysterectomy. This finding may be attributable to the diversity of symptoms, age, educational level, diagnosis or occupational status of the women in this sample.

The difference between symptom types and HRQoL was analyzed using the t test. The results showed that women with menorrhagia before hys-terectomy had a lower PCS score (t= −2.3, p < 0.05) and a higher MCS score (t= 2.1, p < 0.05) com-pared to women without this symptom. At 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy, no statistically significant differences in PCS and MCS scores w

were found between women with and without menorrhagia. In addition, comparison of the re-lated differences (score before surgery subtracted from score at 6 months postsurgery) between

before and 6 months after hysterectomy showed significant improvements in PF in the women who had menorrhagia (t= 2.5, p < 0.05) and also in PCS (t= 3.2, p <0.05) compared to the women withoutt this symptom. But these women still showed less improvement in SF (t= −3.0, p < 0.01) and MCS (t= −2.5, p < 0.05) compared to the women without menorrhagia. There were significant dif-ferences between patients with and without ab-dominal pain in PCS (t= −2.5, p <0.05) and bodilyy pain (t= −4.9, p < 0.00) before surgery. However, there was no significant difference in PCS afterr surgery between these groups. Additional com-parison of the related differences (score at 6 months minus score before surgery) between be-fore and 6 months after hysterectomy revealed that women who had abdominal pain had

Table 3. Health-related quality of life before and at 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy

Preoperative Postoperative at Postoperative at Friedman’s Wilcoxon signed

Items (I) 6 mo (II) 12 mo (III) test rank test

M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) (χ2) (Z)

Physical functioning 45.2 (12.0) 53.0 (7.5) 53.1 (7.5) 22.4* II> I (4.4†) III> II (0.7) III> I (3.3†) Role limitations due 42.3 (13.9) 49.5 (2.4) 43.7 (12.9) 10.1* II> I (2.7‡)

to physical health problems Bodily pain 43.6 (14.9) 56.5 (7.7) 55.5 (6.8) 26.2* II> I (4.1†) II> III (0.5) III> I (3.7†) General health 38.1 (12.4) 49.9 (13.2) 48.0 (12.3) 21.1* II> I (3.8†) perception II> III (1.0) III> I (3.5†) PCS 42.1 (13.1) 52.5 (8.7) 51.0 (9.1) 23.3* II> I (5.0†) II> III (1.5) III> I (3.8†) Vitality, energy/fatigue 50.0 (8.6) 54.0 (7.5) 53.2 (6.5) 5 Social functioning 47.5 (10.0) 54.4 (6.8) 53.8 (5.6) 19.9* II> I (3.9†) II> III (0.1) III> I (3.5†) Role limitations due 43.3 (15.0) 52.5 (9.4) 52.2 (9.7) 11.5* II> I (3.1†)

to emotional health III> II (0.9)

problems III> I (2.6‡)

General mental health 47.2 (8.0) 50.8 (7.5) 51.5 (5.7) 4

MCS 47.7 (12.5) 52.1 (7.7) 52.4 (6.6) 0.4

*p< 0.01, Friedman’s test;††p< 0.003 and ‡‡p< 0.017, Wilcoxon signed rank test. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; PCS = physical component summary; MCS= mental component summary.

significant improvements in RP (t= 2.5, p < 0.05), BP (t= 3.2, p < 0.01), GH (t = 2.0, p < 0.05) and PCS (t= 3.5, p < 0.01) compared to women without this symptom. Categorizing patients according to hemoglobin (Hb) level before hysterectomy, Hb level at 10.5 mg/dL using the 50thpercentile as the cut-off point revealed that PCS (t= −2.4, p< 0.05), MCS (t = 2.4, p < 0.05) and RE (t = 2.3, p< 0.05) were different between these two strata. Hb level did not show any significant association w

with self-rated health score.

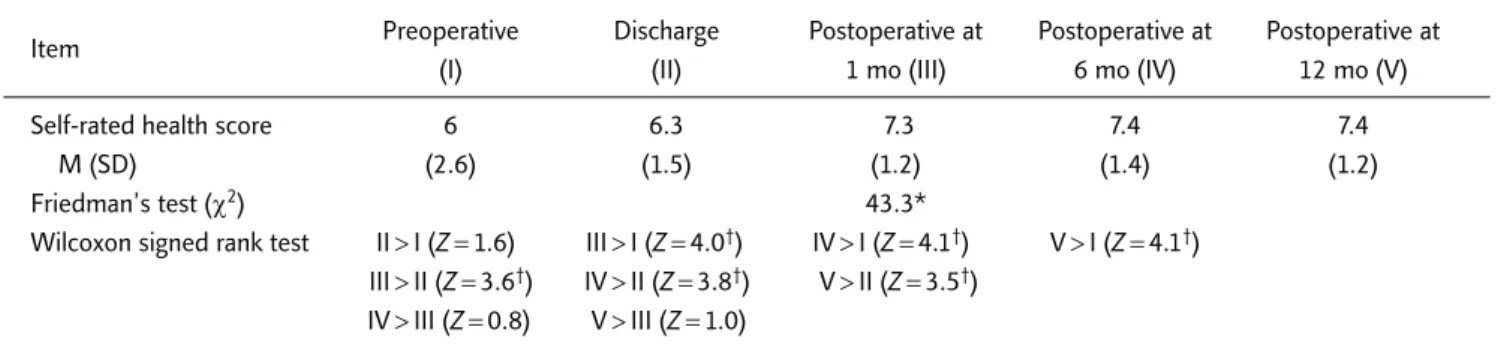

The mean score in self-rated health status increased from 6.0 at presurgery to 6.3 at dis-charge, 7.3 at 1 month after surgery, and 7.4 at 6 and 12 months after surgery. Using Friedman’s test, significant differences were found between the five health status measurements at these time

points (p< 0.01) (Table 4). Additionally, while no difference was found between presurgery and at discharge, a significant difference was found y between discharge and 1 month after surgery (Z=3.2, p<0.01), between discharge and 6 months (Z= 3.1, p <0.01), and between discharge and 12 months (Z= 3.2, p < 0.01) after hysterectomy. No significant differences were found in the five health status measurements between 1, 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy. The health score postsurgery was significantly correlated with PCS (at 6 months, r= 0.66, p < 0.01; at 12 months, r = 0.64, p< 0.01) and MCS (at 6 months, r = 0.59, p< 0.01) (Table 5).

Multiple regression analyses were performed with the following factors as independent vari-ables: age, years of education, occupational

Table 4. Comparison of self-rated health score preoperatively, at discharge, and at 1, 6 and 12 months postoperatively

Item Preoperative Discharge Postoperative at Postoperative at Postoperative at

(I) (II) 1 mo (III) 6 mo (IV) 12 mo (V)

Self-rated health score 6 6.3 7.3 7.4 7.4

M (SD) (2.6) (1.5) (1.2) (1.4) (1.2)

Friedman’s test (χ2) 43.3*

Wilcoxon signed rank test II> I (Z(( = 1.6) III > I (Z(( = 4.0†) IV> I (Z(( = 4.1†) V> I (Z(( = 4.1†) III> II (Z(( = 3.6†) IV> II (Z(( = 3.8†) V> II (Z(( = 3.5†)

IV> III (Z(( = 0.8) V> III (Z(( = 1.0)

*p< 0.01, Friedman’s test; ††p< 0.0025, Wilcoxon signed rank test. M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Table 5. Correlation of eight health concepts in the SF-36 and self-rated health score preoperatively and at

6 and 12 months postoperatively

Self-rated health score/ Preoperative Postoperative 6 mo Postoperative 12 mo

eight concepts in SF-36 (I) (II) (III)

Physical function 0.2 0.5* 0.7*

Role limitations due to 0.2 0.5* 0.6*

physical health problems

Bodily pain −0.3 0.4† 0.0

General health 0.6* 0.8* 0.7*

Vitality/fatigue 0.4* 0.6* 0.6*

Social functioning 0.4* 0.7* 0.5*

Role limitations due to 0.0 0.5* 0.4†

emotional problems

Mental health 0.5* 0.6* 0.5*

PCS 0.1 0.7* 0.6*

MCS 0.3 0.6* 0.3

*p

status, knowledge of which body part(s) will be removed, self-rated health score and Hb level before surgery, with HRQoL acting as the dependent variable before surgery. The analysis showed that the adjusted R2 for PCS in HRQoL w

was 0.26, with Hb level being the most powerful predictor. It also showed that the adjusted R2for

MCS in HRQoL was 0.36, with Hb level and occupational status being the most powerful predictors.

An additional multiple regression analysis was performed; this time with the following fac-tors as independent variables: age, years of edu-cation, occupational status, knowledge of which

Table 6. Marginal linear regression models of the health-related quality of life by the generalized estimating equation

method

Covariate Estimate Model-based

95% CI

p standard error Lower Upper

A. The physical component summary (PCS) model

Intercept 9.4 9.0 −8.3 27.1 0.3 6 mo postoperative vs. preoperative 48.5 7.9 33.0 64.1 < 0.0001 12 mo postoperative vs. preoperative 61.4 13.7 34.6 88.2 < 0.0001 Years of education 16 vs. 12 −5.2 3.0 −11.1 0.7 0.1 18 vs. 12 −15.6 8.2 −31.5 0.4 0.1 Hb (preoperative) 3.3 0.9 1.6 5.0 0.0001

Age× 12 mo postoperative vs. preoperative −0.4 0.2 −0.8 0.1 0.1

Hb (preoperative)× 6 mo postoperative vs. preoperative −3.6 0.7 −5.1 −2.2 < 0.0001 Hb (preoperative)× 12 mo postoperative vs. preoperative −3.4 0.9 −5.3 −1.6 0.0003 B. The mental component summary (MCS) model

Intercept 35.1 10.6 14.5 55.8 0.0009

Age 0.3 0.2 −0.0 0.6 0.0536

Years of education: 18 vs. 12 and 16 16.0 5.7 4.8 27.1 0.005

Employed: yes vs. no 10.3 2.6 5.1 15.5 0.0001

Knowing the part of body to be removed before surgery 7.1 4.1 −0.8 15.1 0.0799 vs. not knowing

Hb (preoperative) −2.5 0.6 −3.8 −1.3 < 0.0001

Having blood transfusion vs. none 6.3 2.2 2.1 10.5 0.0035

Years of education: 16 vs. 12 and 18× 6 mo 5.9 2.6 0.8 11.1 0.024

postoperative vs. preoperative

Employed: yes vs. no× 6 mo −5.8 2.4 −10.6 −1.1 0.0152

postoperative vs. preoperative

Employed: yes vs. no× 12 mo −10.0 2.9 −15.7 −4.3 0.0005

postoperative vs. preoperative

Knowing the part of body to be removed before −9.2 4.2 −17.3 −1.0 0.0274 surgery vs. not knowing× 6 mo postoperative vs.

preoperative

Knowing the part of body to be removed before surgery −9.8 4.9 −19.5 −0.1 0.0480 vs. not knowing× 12 mo postoperative vs. preoperative

Hb (preoperative)× 6 mo postoperative vs. 1.9 0.5 0.9 2.9 0.0002

preoperative

Hb (preoperative)× 12 mo postoperative vs. preoperative 2.9 0.6 1.7 4.1 < 0.0001

body part(s) will be removed, Hb level before surgery, blood transfusion during and after sur-gery, and self-rated health score, HRQoL again being the dependent variable at 6 and 12 months after surgery. The analysis showed that the ad-justed R2 for this model was 0.36, with the self-rated health score contributing 62% of the v

variance in the PCS of HRQoL. The adjusted R2 for the MCS in HRQoL was 0.54, with the self-rated health score, receiving blood transfusion after surgery and age showing significant differ-ences in this model. The analysis also showed that the adjusted R2 for this model was 0.29, w

with the self-rated health score contributing 59% of the variance in the PCS of HRQoL at 12 months after surgery. A regression model could not be found for MCS.

Moreover, the GEE method for modeling the repeated measures data was used to identify the statistically significant influencing factors of HRQoL before and after hysterectomy and to assess their relative importance (Table 6). The following factors were independent variables: age, years of education (divided into five levels), occupational status, knowledge of which body part(s) will be removed, Hb level before surgery, blood transfusion during and after surgery, plus w

with the interaction variables by each two of these independent variables. HRQoL (PCS or MCS) w

was the dependent variable in each model. The final model showed that the R2 for this model w

was 0.35 in the PCS of HRQoL. Statistically sig-nificant improvement in PCS was identified. W

Women with more than 12 years of education or lower Hb levels had lower PCS scores before surgery. Older patients had lower PCS scores at 12 months after hysterectomy. Age had a nega-tive effect on PCS after surgery. Given that the v

values of other covalues are fixed, the effect of Hb (presurgery) on PCS is (3.3− 3.6 PCST2 − 3.4 PCST3), where PCST2 and PCST3 are two dummy v

variables (PCST2= 0 and PCST3 = 0 is the PCS before surgery, the first time point; PCST2= 1 and PCST3= 0 is the PCS at 6 months after surgery, the second time point; PCST2= 0 and PCST3= 1 is the PCS at 12 months after surgery,

the third time point) representing three time f points. Thus, at the first time point, the effect of Hb on PCS is 3.3, at the second time point, it is −0.3 (3.3 − 3.6), and at the third time point, it is −0.1 (3.3 −3.4). Therefore, Hb level before surgeryy y had positive impact only on PCS at presurgery (bˆ = 3.3, p = 0.0001), but had no effect at 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy. The interpretation of the other interaction terms in Table 6 followed the same principle (as Hb).

The R2of the marginal regression model forr MCS in HRQoL was 0.48. There was no signifi-cant change in MCS after hysterectomy. Age (bˆ = 0.3, p= 0.0536) and having blood transfusion (bˆ = 6.3, p = 0.0035) always positively affected the MCS score. More years of education also pos-itively affected the MCS score, especially at 6 months after hysterectomy. Women who were employed had a positive effect on the MCS score (bˆ = 10.3, p = 0.0001), but that effect decreased to half (bˆ = 10.3 − 5.8 = 4.5, p < 0.05) at 6 months after hysterectomy, and then diminished to none (bˆ = 10.3 − 10.0 = 0.3, p >0.05) at 12 months afterr hysterectomy. If the patient was an employee, r she had higher score in MCS before and after

y surgery. Similarly, knowing the part of the body to be removed before surgery only positively af-fected the MCS score before surgery (bˆ = 7.1, p = y 0.0799). In contrast, Hb level before hysterectomy only negatively affected the MCS score before sur-gery (bˆ = −2.5, p <0.0001), but its effect graduallyy diminished after surgery.

Discussion

This study showed that postsurgery, overall self-y rated health status and HRQoL were significantly improved at 6 months and then remained con-stant throughout 1 year after hysterectomy. Within 6 months after hysterectomy, patients had re-turned to normal health and bodily functions, a finding compatible with related research.2,3,9,27 Symptom relief after hysterectomy is associated with a marked improvement in HRQoL.17The re-sults support previous findings that patients with

severe excess menstrual bleeding experienced the greatest improvement in physical health but sur-gical treatment had no significant effect on the w

women’s psychological health dimensions of SF-36. This finding is in contrast to a study by Ruta et al,28who found that the major impact of menorrhagia was on social functioning. The prob-able explanation is that the participants perceived menorrhagia as a normal physical change that affected their physical health but did not affect their role expectation and performance. They might have been proud that they still performed their roles in life so well despite this physical impairment. However, not all women who have undergone a hysterectomy benefit from this pro-cedure, and almost 8% of the women who under-w

went hysterectomy in a previous study reported the same or increased number of symptoms.10 In this study, 5.4% of patients had sequelae at 1 month and 16.7% at 6 months after hysterec-tomy, which supports this previous finding.

Interpretation of the SF-36 (Taiwan version) scores in this study population may be facilitated by comparison with the available normative data. T

The advantage of the SF-36 (Taiwan version) is that the norm used in the validation of the instru-ment was different age groups of women.29In this study, the participants’ HRQoL in each of the eight health concepts of SF-36 was lower than the norm before hysterectomy. Jones et al proposed that benign gynecologic conditions had a negative impact on HRQoL, which is even greater when comparisons are made to women with nongyne-cologic conditions.20 At 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy, patients had significantly higher scores than the norm standard in six of the eight health concepts of SF-36, with the exception of physical functioning and role limitation due to physical problems. In addition, role limitations due to physical health problems and general health exhibited high coefficients of variation postsurgery. This demonstrates that patients had w

widely differing recovery processes, with some not fully recovering and thereby experiencing limita-tions in life performance. An active life, which in-cluded more than childbearing and motherhood

roles, defined middle-aged women and was re-ported as the major expectation from the hysterec-tomy.28In this study, patients usually inquired as to how long it would take before they could go back to normal life and daily activities after the surgery. One year after the surgery, six patients (18.2%) reported that they had less energy than before, while two noted emotional disturbances t due to unsatisfactory physical recovery. Thus, it seems that limitations in physical activity reduced r their social role performance, impacting their general health perception.

The results of this study indicate that role func-t tion and sexual life adjustment are very important aspects of HRQoL in women who have undergone hysterectomy. A negative impact on sexual func-tioning has also been reported in women with endometriosis,18dysfunctional uterine bleeding16 and menorrhagia.30However, the instrument we g used for measuring HRQoL, the SF-36, is lacking in these health concepts. A previous study also noted that generic tools did not include the com-ponents of health that were specific to women with menorrhagia.31Thus, generic questionnaires are insufficient for the evaluation of clinical changes in HRQoL in women with benign gyne-cologic disorders.20One limitation of the use off generic measures is that they may not be sensitive enough to assess changes in specific conditions L because they are designed to measure HRQoL y across a wide variety of diseases. This most likely L explains our finding of low variance of HRQoL t at 12 months after hysterectomy, even though it was not possible to build up an adequate predic-tion model in the MCS of HRQoL. At 12 months after surgery, these patients had not only recov-ered from the hysterectomy, but had also reached a new equilibrium in their life and health.

It has been argued that it is best to use more than one instrument when HRQoL is being meas-ured.19 In this study, two generic instruments (SF-36 and self-rated health score) were used r to measure HRQoL in women before and after f hysterectomy. This allowed confirmation of improvements in self-rated health status and HRQoL postsurgery, and of the high correlation

of self-rated health status with PCS and MCS in SF-36. The single-item self-rated health score was shown to be a valid and reliable predictor of PCS at 6 and 12 months after hysterectomy. This is consistent with Shadbolt’s findings that self-rated health was subject to change in physical health status in middle-aged Australian women.32

There is a clear need for incorporation of more patient-generated, disease-specific question-naires into the clinical assessment of patients w

with benign gynecologic conditions, preferably in conjunction with generic measures. The measure-ment of HRQoL in women with benign gyneco-logic conditions before and after hysterectomy should also consider aspects of women’s role, family and sexual function. The related variables and measurement time scale should be increased during the follow-up process.

This study used a prospective follow-up design, and collected data on HRQoL and influencing fac-tors before surgery and during a 1-year recovery period. This contemporaneous collection of infor-mation also limited recall biases, thus improving the reliability and accuracy of information about the condition and needs of the patients during re-covery. The findings of this study may be useful in assessments of the appropriateness and outcome of hysterectomy, and provide additional insight into the surgery’s potential impact on HRQoL and w

what patients can expect during recovery.

This study had several limitations. First, the severity of symptoms and the effects of distress due to symptoms on HRQoL were not measured, w

which might have been valuable in predicting v

variables related to HRQoL. Colwell et al33found that women with severe endometriosis-associated pain had worse functioning on each HRQoL scale than women whose pain was mild to moderate. T

The rehabilitation period for women who had undergone hysterectomy in their study, however, did not exceed 6 months. The critical time period for assessing HRQoL recovery from hysterectomy remains unclear. Future study with the use of additional measurements during the interval be-tween 1 and 6 months after surgery may uncover early trends. Finally, the sample size of this study

was small. Future studies with more participants may provide clearer implications, and improve the accuracy of results.

Conclusion

Menstrual symptoms such as menorrhagia and L abdominal pain had negative effects on HRQoL after a hysterectomy. During the recovery period, HRQoL and self-rated health score improved. This study identified a regression model of the L relationship between hysterectomy and HRQoL over time. Hysterectomy effectively improves the t physical domain of patients’ HRQoL. No direct effect of hysterectomy on patients’ mental do-main of HRQoL was found in this study, but the data suggested that it may have had positive as-sociations with role function and performance. Knowledge of these potential effects of hysterec-tomy is important for gynecologists and nurses to provide preoperative counseling to women undergoing this procedure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study subjects for com-pleting the questionnaires and acknowledge the financial support from the National Science Council of Taiwan. They also appreciate Dr Hsu-Min Tseng’s support and consultation on the SF-36 data management and Dr Fu-Chang Hu’s and Ms Chen-Fung Chen’s help on the GEE model-ing for longitudinal data analysis.

References

1. Chueh C, Chu-Hui C, Shu-Fen K, et al. A preliminary study on hysterectomy rate in Taiwan. Chin J Public Health

(Taipei) 1995;14:487–93. [In Chinese]

2. Carlson KJ, Miller BA, Flower FJ. The Maine women’s health study: I. Outcomes of hysterectomy. Obstett Gynecol 1994;83:556–65.

3. Carlson KJ, Miller BA, Flower FJ. The Maine women’s health study: II. Outcomes of nonsurgical management

leiomyomas, abnormal bleeding, and chronic pelvic pain.

Obstet Gynecol 1994;83:566–72.

4. Naughton KJ, Mcbee WL. Health-related quality of life after hysterectomy. Clin Obstet 1997;40:947–57. 5. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Crawford DA. Hysterectomy for

chronic pelvic pain of presumed uterine etiology. Obstet

Gynecol 1990;75:676–9.

6. Lalinec-Michaud M, Engelsmann F, Marino J. Depression after hysterectomy: a comparative study. Psychosomatics 1988;29:307–14.

7. Drellich MG, Bieber I. The psychologic importance of the uterus and its functions. J Nerv Ment Dis 1958;126:322–36. 8. Kritz-Silverstein D, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and depression in older women. J Womens Health 1994;3:255–63.

9. Lambden MP, Bellamy G, Ogburn-Russell L, et al. Women’s sense of well-being before and after hysterec-tomy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1997;26:540–48. 10. Kjerulff KH, Langenberg PW, Rhodes JC, et al. Effectiveness

of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:319–26. 11. Meikle S, Brody H, Pysh F. An investigation into the

psy-chological effects of hysterectomy. J Nerv Ment Dis 1977;164:36–41.

12. Padilla GV, Grant MM, Ferrell B. Nursing research into quality of life. Qual Life Res 1992;1:341–8.

13. Levinson CJ. Hysterectomy complications. Clin Obstet

Gynaecol 1972;15:802–26.

14. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:622–29. 15. Sculpher MJ, Bryan S, Dwyer N, et al. An economic

evalu-ation of transcervical endometrial resection versus ab-dominal hysterectomy for the treatment of menorrhagia.

Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993;100:244–52.

16. Clarke A, Black N, Rowe P, et al. Indications for and out-come of total abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease: a prospective cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102:611–20.

17. Sculpher MJ, Dwyer N, Byford S, et al. Randomised trial comparing hysterectomy and transcervical endometrial re-section: effect on health related quality of life and costs two years after surgery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:142–9. 18. Row MK, Kanouse DE, Mittman BS, et al. Quality of life

among women undergoing hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:915–21.

19. Patrick DL, Bergner M. Measurement of health status in the 1990s. Annu Rev Public Health 1990;11:165–83.

20. Jones GL, Kennedy SH, Jenkinson C. Health-related qual-ity of life measurement in women with common benign gynecologic conditions: a systemic review. Am J Obstett Gynecol 2002;187:501–11.

21. Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using gen-eralized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22. 22. Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for

dis-crete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42: 121–30.

23. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medl Care 1992;30:473–83.

24. Ware JE, Kosinsk M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey:

Manual and Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality

Metric Incorporated, 2003;2:1–26.

25. Tseng HM, Lu JR, Gandek B. Cultural issues in using the SF-36 health survey in Asia: results from Taiwan. Health

Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:1–9.

26. Ware JE, Ware Jr, Kosinsk M. SF-36 Physical and Mental

f Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual for Users of Version 1, 2ndedition. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incor-porated, 2003:18–20.

f 27. Rannestad T, Eikeland OJ, Helland H, et al. The quality of life in women suffering from gynecological disorders is improved by means of hysterectomy. Absolute and relative differences between pre- and postoperative measures.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:46–51.

28. Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Russell IT. Patient centered assess-ment of quality of life for patients with four common con-ditions. Qual Health Care 1999;8:22–9.

29. Tseng HM, Lu JR, Tsai YJ. Assessment of health-related quality of life (II): norming and validation of SF-36 Taiwan Version. Taiwan J Public Health 2003;1:1–9.

30. Lamping DL, Rowe P, Clarke A, et al. Development and validation of the menorrhagia outcomes questionnaire. rBr J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:1155–9.

31. Shaw R, Brickley MR, Evans E, et al. Perceptions of women on the impact of menorrhagia on their health using multi-attribute utility assessment. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105:1155–9.

32. Shadbolt B. Some correlates of self-rated health for Australian women. Am J Public Health 1997;87:951–6. 33. Colwell H, Mathias SD, Pasta DJ, et al. A health-related

quality of life instrument for symptomatic patients with endometriosis: a validation study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:47–55.