Vol. 25, No. 6, pp 503Y513xCopyrightB 2010 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Self-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life

and Sleep Disturbances in Taiwanese People

With Heart Failure

Hsing-Mei Chen, PhD, RN; Angela P. Clark, PhD, RN, CNS, FAAN, FAHA; Liang-Miin Tsai, MD;

Chiu-Chu Lin, PhD, RN

Background and Research Objective: Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has been viewed as the most important clinical outcome of heart failure (HF) management. However, information about the predictors of HRQOL in Taiwanese people with HF is limited, especially for the effects of sleep disturbances on HF. Purpose: The purpose of this study was to identify predictors of HRQOL in Taiwanese people with HF, especially focusing on the extent to which sleep variables are related to HRQOL. Methods: A cross-sectional, descriptive correlational design was used. A nonprobability sample of 125 participants was recruited from the outpatient departments of 2 hospitals located in southern Taiwan. Participants were face-to-face individually interviewed to complete the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Data for concomitant health problems and HF characteristics were collected from the medical records. Results: The mean Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score for HRQOL in this sample was 70.50 (SD, 19.63). Health-related quality of life physical symptom had the highest score, and the psychological satisfaction domain had the lowest. Six predictors of the HRQOL were identified by using a 3-step hierarchical multiple regression analysis with forward method. The predictors were education (R2= 0.09), New York Heart Association functional class (R2= 0.398), Charlson Comorbidity Index number (R2= 2.6), subjective sleep quality (R2= 0.037), sleep disturbances (R2= 0.015), and sleep latency (R2= 0.018), and together they accounted for a total of 58.5% of the variance in HRQOL. Conclusions: Nurses should use a holistic perspective to help patients understand and manage the impact of HF on their daily lives. Effective interventions for improving HRQOL should be designed based on patients’ needs and lifestyles. The study findings could serve as a baseline for further longitudinal studies to explore the long-term effects of correlates and causal relationships among the variables in this Taiwanese population with HF.

KEY WORDS:health-related quality of life, heart failure, sleep disturbance

C

hronic heart failure (HF) is characterized by several complex symptoms that are difficult to control and result in a high rate of rehospitalization, morbidity, and mortality across the world.1,2Symptom burden in HF is devastating and causes poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL).3,4Worsening symptoms such as fatigue,exercise intolerance, and dyspnea are associated with an increased prevalence of sleep disturbances,5,6 esti-mated at 30% to 70%.7Y9Limited research has shown that sleep disturbances are independently associated with worsened HRQOL almost to the same extent as having HF.10 However, the extent to which sleep

variables are related to HRQOL in Taiwanese people is unclear. Understanding the interaction between sleep disturbances and HRQOL is needed to provide effective care for this population.

Health-related quality of life has been viewed as the most important clinical outcome to guide therapeutic interventions aimed at increasing survival.11 Health-related quality of life is conceptualized based on the social science paradigm concerned with individuals’ perceptions of daily functioning and overall well-being, with attention to their behaviors and feelings.12 A better sense of HRQOL is important in maintaining a state of overall well-being that reflects an optimistic perspective.13In viewing themselves in a positive way,

Hsing-Mei Chen, PhD, RN

Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Taiwan.

Angela P. Clark, PhD, RN, CNS, FAAN, FAHA

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, The University of Texas at Austin.

Liang-Miin Tsai, MD

Professor of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan.

Chiu-Chu Lin, PhD, RN

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Taiwan.

Correspondence

Hsing-Mei Chen, PhD, RN, Room N440, 100, Shih-Chuan 1st Rd, Kaohsiung 80708, Taiwan (hsingmei@ntu.edu.tw).

people may have better motivation to adhere to long-term treatments.

One challenge in measuring HRQOL is that it is a broad, multidimensional concept that comprises a wide range of needs within a physical, psychosocial, and cul-tural context.14,15This means that many factors need to be taken into concern when measuring HRQOL in-cluding demographics, clinical characteristics, and psy-chosocial factors.4Health-related quality of life is rooted in an individual’s cultural background15; thus, more re-search studies are needed to identify correlates of better HRQOL in HF-specific patients of varying cultures.

The effect of sleep on HRQOL cannot be under-estimated and has been viewed as a facet in the physical health domain of quality of life.16 Adequate sleep is essential for biological and mental restoration, pro-tection, integration, and memory. Therefore, a good quality of sleep is important to maintain physical health17and psychological well-being.18Sleep distur-bances, however, can disrupt the restoration of dam-aged myocardium, resulting in a worsened prognosis in HF.19Excessive daytime sleepiness may follow noc-turnal sleep problems and further interrupt the pa-tient’s circadian rhythm and daily activities.10

The relationship between sleep disturbances and HRQOL in HF needs more evidence. Researchers have reported that sleep disturbances reduced the HRQOL of HF patients, especially for those with sleep-related breathing disorders.7,20Y24However, researchers found different effects of sleep disturbances on the domains of HRQOL. In the study of 223 patients with HF of Brostrom et al,7 the 3 dimensions of HRQOL most influenced by sleep disturbances were general health, vitality, and social functioning, whereas physical health, bodily pain, and emotional functioning had the greatest impact on sleep-related breathing disorder in the Skobel et al23 study with 51 HF patients with left ventricular

ejection fraction of less than 35%. Likewise, there is a need to examine the extent to which sleep variables are relative to HRQOL. In the Redeker and Hilkert22 study, sleep quality and continuity had greater effects on HRQOL than sleep quantity in 61 patients with stable systolic HF. After controlling for age, sex, co-morbidity, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, perceived sleep quality was most rele-vant to mental health, whereas objective data for sleep continuity measured by actigraph were the most rele-vant to functional performance.22The finding that sleep duration was not associated with functional perform-ance differed from other researchers’ view that sleep duration affects health and daily functioning.25,26More research is needed to clarify these relationships.

The purpose of this study was to identify predictors of HRQOL in Taiwanese people with HF, especially for the effects of sleep disturbances on HRQOL. The conceptual model used to guide the study suggests that HRQOL consists of 4 domains, including physical symptoms, physical limitation, psychological satisfaction, and social functioning (Figure). Sleep disturbances included sleep disruption, prolonged sleep latency, and extended sleep duration, occurring in either nighttime or daytime sleep. The study hypothesized that demographics, HF, health-related characteristics, and sleep disturbances were cor-related with HRQOL in Taiwanese people with HF. In particular, sleep disturbances could have a significant effect on HRQOL, after controlling for demographics, HF, and health-related characteristics.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional, descriptive correlational design was used. Prior to the formal data collection, a pilot study

was conducted to test the psychometric properties of all questionnaires and estimated sample size for the formal data collection. All participants were individu-ally interviewed by the principal investigator to com-plete questionnaires in a private area in either a clinic or home. Face-to-face interviews provided a supple-ment for the data interpretations. Interviews lasted from 20 to 60 minutes. The study was reviewed by the institutional review boards of the University of Texas at Austin and a medical center in Taiwan.

Setting and Sample

A nonprobability sample of 125 participants with HF was recruited from the outpatient departments of a large medical center and an affiliated hospital located in southern Taiwan. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having a diagnosis of HF with any class of NYHA I, II, III, or IV as determined by physicians, (2) being 18 years or older, (3) community dwelling, (4) able to commu-nicate either by speaking Mandarin or Taiwanese or writing Mandarin (the official Chinese language), and (5) willing to participate in this study. The sample size was calculated using the software Power Analysis and Sample Size 2005 based on Cohen’s27statistical power analysis method with a level of power of 0.8 at a sig-nificant! level of .05. Using the smallest effect size of 0.26 among the associations between HRQOL and 22 major independent variables from the pilot study (n = 13), a sample size of 125 was recommended.

Instruments

Demographic and Clinical Questionnaires

The demographic questionnaire included age, sex, edu-cation, marital status, employment status, perceived financial status, and language. The clinical question-naire consisted of HF and health-related characteristics. Heart failure characteristics included type of HF, time since the HF diagnosis, NYHA class, and HF medi-cations. Health-related characteristics included body mass index, comorbidity, and a chart-review list of concomitant health problems. Comorbidity was mea-sured using Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

The CCI is composed of 16 items of self-reported comorbidities.28Patients were asked to evaluate their comorbid conditions on a 2-point scale (yes/no). The CCI is calculated using assigned weights for each con-dition (zero, 1, 3, or 6) to reflect both the number and the severity of the comorbidities. Spearman correla-tion between the self-report method and the medical recordYbased Charlson index for criterion validity was 0.63 in a sample of 170 inpatients older than 55 years.29 The self-reported CCI was translated from English into Mandarin-Chinese by the principal inves-tigator for this study.

The chart-review list of 10 concomitant health problems was adapted from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards.30 The 10 problems are musculoskeletal diseases, diabetes/high blood sugar, gastrointestinal diseases, chronic pulmonary diseases, neurological diseases, renal diseases, psychological/ mental health, thyroid, cancer, and other diseases, such as cataract and benign prostatic hyperplasia. The list contained more specific cardiovascular diseases that could complement the CCI. The data were collected from the hospital medical records by the principal investigator.

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

The 23-item HF-specific questionnaire, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), was used to measure HRQOL. The KCCQ consists of 6 domains: physical limitations (6 items); symptoms, including frequency (4 items) and severity (3 items); symptom stability (1 item); self-efficacy (2 items); social function-ing (4 items); and quality of life (3 items).31Patients are asked to answer questions about how HF has affected their lives over the past 2 weeks. Items are scored using an ordinal response scale ranging from 1 to 7. A score for each domain is transformed to a 0- to 100-point scale, with a higher score indicating better HRQOL. An overall summary score is calculated by summing the scores of the physical limitation, symptom, quality of life, and social functioning domains. For this current study, the 4 subscales were used to reflect the domains of HRQOL defined by this current study: physical limitation, physical symptoms, psychological satisfac-tion, and social functioning, respectively. On the other hand, the psychological satisfaction was measured by the 3-item quality-of-life scale of the KCCQ. Research studies have reported good psychometric properties for the KCCQ.31,32 The KCCQ was translated into Mandarin-Chinese for this study. Dr John Spertus, originator of the KCCQ, served as a consultant for the translation. Cronbach !’s for each domain were as follows: physical limitations, .89; physical symptoms, .75; quality of life, .67; social functioning, .75; and overall summary score, .90.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

The 18-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to measure sleep disturbance.33 Participants are asked to answer questions regarding sleep quality and sleep disturbances over a 1-month period. The 18 items are grouped into 7 components: subjective sleep quality (1 item), sleep latency (2 items), sleep duration (1 item), habitual sleep efficiency (3 items), sleep disturbances (9 items), use of sleeping medication (1 item), and daytime dysfunction (2 items). Each component of the PSQI is weighted equally with a possible scale range of 0 to 3.

The 7 component scores are then summed to produce a global score ranging from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates a poor sleep quality. This current study used the Chinese-Mandarin version of PSQI translated by Tsai and colleagues.34 In the present study, Cronbach !’s for domains of PSQI were as follows: sleep latency, .78; sleep disturbances, .51; daytime dysfunction, .79; and global PSQI, .70.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

The self-reporting Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) con-sists of 8 items that ask respondents to rate the chances that they would fall asleep or doze off in 8 specific life situations, such as sitting and reading, watching TV, or sitting stopped in traffic. Each of the 8 items is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (would never doze) to 3 (high chance of dozing).35The total score ranges from 0 to 24, with a lower score indicating low sleep pro-pensity. An ESS greater than 10 is defined as excess daytime sleepiness, and 16 and greater indicates a high level of daytime sleepiness. The ESS has been translated into Chinese-Mandarin by Chen and colleagues.36Cronbach! for the present study was .74. Based on the fact that several participants in the pilot study claimed to take daytime naps habitually, 3 items in respect to the prevalence, frequency, and duration of daytime napping developed by the principal investiga-tor were added into the ESS.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, release 14.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Data analysis approaches included descriptive statistics and inferential statistics, including independent t tests, 1-way analysis of variance, bivariate correlations, and hierarchical multiple regression analyses with forward method. Be-fore the data analysis, checks were made for normality and normal distribution of the major variables and assumptions of the multiple regression analysis for pre-dictor variables of HRQOL. The level of significance was set at .05 for all statistical analyses.

Results

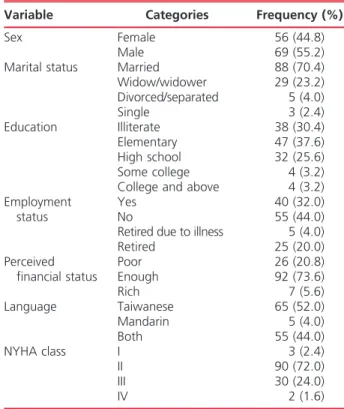

The demographics for the sample of 125 Taiwanese are summarized in Table 1. The mean age for the 125 Taiwanese was 67.79 (SD, 12.19) years, with a median of 68.93 years and a range of 29.78 to 86.86 years. Most participants were elderly, male, married, literate, unemployed or retired, and Taiwanese speaking and reported adequate financial status. For HF character-istics, 50 participants (40.0%) had systolic HF, 51 (40.8%) had diastolic HF, and the remaining (19.2%) had valvular HF.37Most participants (72.0%) were of NYHA class II. The mean number of prescribed HF

medications was 3.58 (SD, 1.51) (range, 1Y8), with a mean duration since HF diagnosis of 35.66 (SD, 43.81) months (range, 1Y192 months).

For health-related characteristics, the mean BMI was 25.55 (SD, 4.37) kg/m2 (range, 16.62Y40.83 kg/m2). The average Charlson comorbidity severity score was 2.39 (SD, 1.88) (range, 0Y8), and the mean comorbidity number was 1.86 (SD, 1.25) (range, 0Y5). The mean chart-review concomitant health problem was 4.88 (SD, 1.83), which included both cardiovascular prob-lems (mean, 3.05 [SD, 1.16]) and noncardiovascular problems (mean, 1.83 [SD, 1.46]). The top 3 concom-itant cardiovascular conditions were hypertension (65.6%), valvular heart disease (56.0%), and coronary artery disease (44%). The top 3 noncardiovascular concomitant problems were musculoskeletal problems (36.8%), diabetes (31.2%), and gastrointestinal prob-lems (25.6%).

Health-Related Quality of Life

The mean KCCQ overall summary score for HRQOL in this sample was 70.50 (SD, 19.63), with a range from 11.98 to 95.83. The physical symptom domain had the highest score (mean, 73.98 [SD, 21.31]), and psycho-logical satisfaction had the lowest (mean, 65.60 [SD, 24.72]) (Table 2). In the physical symptom domain, 24.8% reported swelling feet, ankles, or legs; 69.6% reported fatigue; 68% reported shortness of breath;

TABLE 1 Demographic Characteristics of

Participants (n = 125)

Variable Categories Frequency (%)

Sex Female 56 (44.8)

Male 69 (55.2)

Marital status Married 88 (70.4) Widow/widower 29 (23.2) Divorced/separated 5 (4.0) Single 3 (2.4) Education Illiterate 38 (30.4) Elementary 47 (37.6) High school 32 (25.6) Some college 4 (3.2) College and above 4 (3.2) Employment

status

Yes 40 (32.0)

No 55 (44.0)

Retired due to illness 5 (4.0) Retired 25 (20.0) Perceived financial status Poor 26 (20.8) Enough 92 (73.6) Rich 7 (5.6) Language Taiwanese 65 (52.0) Mandarin 5 (4.0) Both 55 (44.0) NYHA class I 3 (2.4) II 90 (72.0) III 30 (24.0) IV 2 (1.6)

and 24% reported sitting in a chair or using more pillows for sleep. In the physical limitation domain, the most difficult daily activities performed by the participants were ‘‘hurrying or jogging’’ (92.8%), ‘‘do-ing yard work or housework and carry‘‘do-ing groceries’’ (66.4%), and ‘‘climbing a flight of stairs without stop-ping’’ (60.0%). In the psychological satisfaction do-main, more than 84% of the participants reported not satisfied spending the rest of life with HF, 50.4% reported feelings of restrictions in enjoying their life, and more than half of the subjects ‘‘felt discouraged or down in the dumps’’ about their HF. In the social functioning domain, participants reported difficulties in taking part in hobbies and recreational activities (64%), particularly in taking overnight trips, working or doing household chores (83.2%), and visiting fam-ily or friends (50.4%).

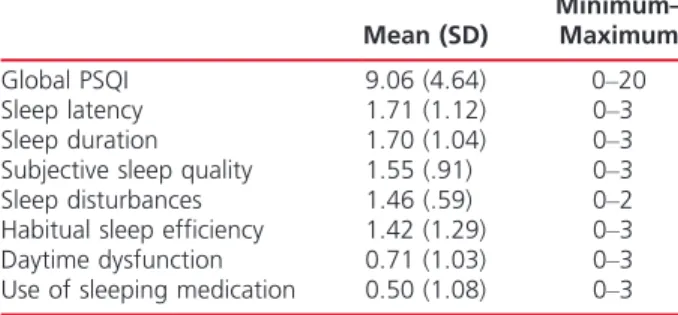

Sleep Disturbances

The global PSQI scores of the 125 participants ranged from 0 to 20, with a mean of 9.06. With a cutoff point of 5,3394 of the participants (74.4%) were identified as poor sleepers (PSQI95). Among the PSQI compo-nents, the sleep latency score was the highest, and use of sleeping medication had the lowest score (Table 3).

Daytime Sleepiness

The ESS scores ranged from 0 to 22, with a mean score of 6.99 (SD, 5.07). When a cutoff point of 10 was used,35 30 of the participants (24%) had excessive daytime sleepiness (ESS 910). For daytime napping, 81.6% of participants reported that they engaged in habitual daytime napping after lunch, with 62.4% taking daytime naps everyday. The mean duration of daytime napping for the 102 participants was 82.3 (SD, 50.42) minutes.

Predictors of HRQOL

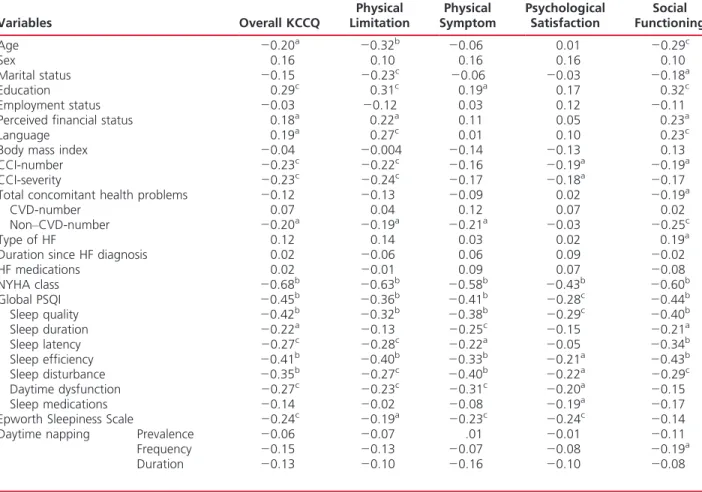

Prior to hierarchal multiple regression analysis, Pearson correlation was initially performed to identify variables that had significant associations with the dependent variable, KCCQ overall summary score (Table 4).

Fifteen variables were identified as correlates of HRQOL. They were age (r = j0.20, PG .05), education (r = j0.30, PG .01), financial status (r = 0.18, P G .05), type of language (r = 0.19, P G .05), NYHA classi-fication (r = j0.68, PG .001), CCI-number (r = j0.23, PG .05), CCI-severity (r = j0.23, P G .05), chart-review concomitant noncardiovascular health problems (r = j0.20, P G .05), subjective sleep quality (r = j0.42, P G .001), sleep duration (r = j0.22, PG .05), sleep latency (r = j0.27, P G .01), sleep efficiency (r = j0.41, P G .001), sleep disturbances (r = j0.35, PG .001), daytime dysfunction (r = j0.27, PG .01), and daytime sleepiness (r = j0.24, PG .01).

Multicolinearity was considered as a potential prob-lem because 2 pairs of variables each showed high and moderate correlations: number versus CCI-severity (r = 0.95, PG .001) and education versus type of language (r = 0.58, P G .001). Therefore, an initial regression analysis with all variables was performed to obtain colinearity diagnostics.38 The results showed that CCI-number and CCI-severity had similar data for tolerance (0.08 for each) and variance inflation factor (VIF) (12.51 for number vs 13.03 for CCI-severity). The CCI-number, however, had a higher unstandardized coefficient (B = j4.70) and stand-ardized coefficient (" = j.30) than CCI-severity (B = 2.03," = .19). It was decided to exclude CCI-severity and to retain CCI-number. Similarly, education was moderately correlated with type of language (r = 0.68, P G .001). Education had a higher unstandardized coefficient (B = 1.16) and a standardized coefficient (" = .10) than type of language (B = j0.75, " = j.04). Therefore, the variable of type of language was eliminated from the regression model. The Pearson correlation coefficients among the final predictor variables ranged from j0.01 to 0.69, tolerance was from 0.47 to 0.88, and VIF was from 1.14 to 3.82.

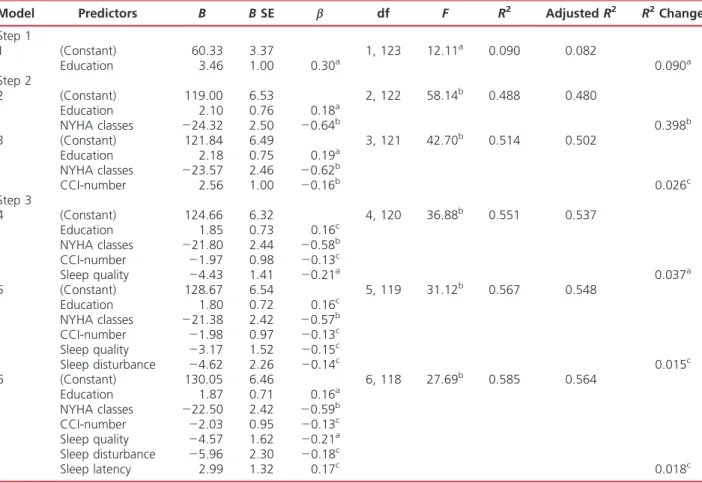

The 13 variables were then available to enter in 3 steps using a hierarchical multiple regression analysis with forward method. A total of 6 models were generated in the 3 steps. The R2for the final model

was 0.585 (PG .001), with an adjusted R2of 0.564.

TABLE 2 Summary for the Health-Related

Quality of Life Scores of the Participants (n = 125)

Mean (SD)

Minimum– Maximum Overall HRQOL 70.50 (19.63) 11.98Y95.83 Physical symptoms 73.98 (21.31) 6.25Y100.00 Physical limitation 73.14 (23.70) 0.00Y100.00 Psychological satisfaction 65.60 (24.72) 0.00Y100.00 Social functioning 69.27 (25.08) 0.00Y100.00

TABLE 3 Summary for the Pittsburgh Sleep

Quality Index Scores of the Participants (n = 125)

Mean (SD)

Minimum– Maximum Global PSQI 9.06 (4.64) 0Y20 Sleep latency 1.71 (1.12) 0Y3 Sleep duration 1.70 (1.04) 0Y3 Subjective sleep quality 1.55 (.91) 0Y3 Sleep disturbances 1.46 (.59) 0Y2 Habitual sleep efficiency 1.42 (1.29) 0Y3 Daytime dysfunction 0.71 (1.03) 0Y3 Use of sleeping medication 0.50 (1.08) 0Y3

Age, education, and financial status were avail-able to enter in the first step as covariates. Education was the only significant predictor among these 3 pre-dictor variables of HRQOL, accounting for 9.0% of the variance (P G .01). Those who had higher edu-cation levels had better HRQOL.

The CCI-number, noncardiovascular concomitant problem, and NYHA class were available to enter in the second step as covariates. Two significant predictors, NYHA class and CCI-number, were identified from these 3 variables. When NYHA class was added to the second model, the R2increased by 0.398 (PG .001), from 0.09 to 0.488. When CCI-number was added to the third model, it accounted for an additional 2.6% of the variance (PG .05) and 51.4% of the variance associated with education and NYHA class. New York Heart As-sociation class and CCI-number collectively accounted for 42.4% of the variance in HRQOL. Participants with HF who had lower NYHA class and a small number of comorbid conditions reported higher HRQOL.

In the third step, subjective sleep quality, sleep dura-tion, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances,

sleep dysfunction, and daytime sleepiness were available to enter. The results showed that, after controlling for education, CCI-number, and NYHA class, subjective sleep quality, sleep disturbances, and sleep latency were identified as significant predictors and accounted for 7.0% of the variance in HRQOL. Subjective sleep quality, when entered into model 4, accounted for 3.7% of the variance in HRQOL (PG .001), resulting in an increased R2, from 0.514 to 0.551. When sleep dis-turbance was added to model 4 to obtain model 5, the percentage of the variance increased by 1.5% (PG .05), from 55.1% to 56.7%. The addition of sleep latency to model 5 to obtain model 6 explained an additional 1.8% of the variance (PG .05). The summary for the hierarchical multiple regression of predictor variables on HRQOL is shown in Table 5.

Discussion

In this study of Taiwanese people with HF, as sleep disturbances increased, HRQOL decreased. This find-ing is similar to other studies involvfind-ing participants

TABLE 4 Correlations Between Major Variables and Health-Related Quality of Life (n = 125)

Variables Overall KCCQ Physical Limitation Physical Symptom Psychological Satisfaction Social Functioning Age j0.20a j0.32b j0.06 0.01 j0.29c Sex 0.16 0.10 0.16 0.16 0.10 Marital status j0.15 j0.23c j0.06 j0.03 j0.18a Education 0.29c 0.31c 0.19a 0.17 0.32c Employment status j0.03 j0.12 0.03 0.12 j0.11

Perceived financial status 0.18a 0.22a 0.11 0.05 0.23a

Language 0.19a 0.27c 0.01 0.10 0.23c

Body mass index j0.04 j0.004 j0.14 j0.13 0.13

CCI-number j0.23c j0.22c j0.16 j0.19a j0.19a

CCI-severity j0.23c j0.24c j0.17 j0.18a j0.17

Total concomitant health problems j0.12 j0.13 j0.09 0.02 j0.19a

CVD-number 0.07 0.04 0.12 0.07 0.02

NonYCVD-number j0.20a j0.19a j0.21a j0.03 j0.25c

Type of HF 0.12 0.14 0.03 0.02 0.19a

Duration since HF diagnosis 0.02 j0.06 0.06 0.09 j0.02

HF medications 0.02 j0.01 0.09 0.07 j0.08 NYHA class j0.68b j0.63b j0.58b j0.43b j0.60b Global PSQI j0.45b j0.36b j0.41b j0.28c j0.44b Sleep quality j0.42b j0.32b j0.38b j0.29c j0.40b Sleep duration j0.22a j0.13 j0.25c j0.15 j0.21a Sleep latency j0.27c j0.28c j0.22a j0.05 j0.34b Sleep efficiency j0.41b j0.40b j0.33b j0.21a j0.43b Sleep disturbance j0.35b j0.27c j0.40b j0.22a j0.29c Daytime dysfunction j0.27c j0.23c j0.31c j0.20a j0.15 Sleep medications j0.14 j0.02 j0.08 j0.19a j0.17

Epworth Sleepiness Scale j0.24c j0.19a j0.23c j0.24c j0.14 Daytime napping Prevalence j0.06 j0.07 .01 j0.01 j0.11

Frequency j0.15 j0.13 j0.07 j0.08 j0.19a

Duration j0.13 j0.10 j0.16 j0.10 j0.08

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NYHA, New York Heart Association Functional Classification; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

aP G .05. bPG .001. cP G .01.

-with HF.7,22Y24 Among the 4 domains of HRQOL, social functioning had the strongest correlation with sleep disturbances, whereas psychological satisfaction had the weakest correlation. The significant influence of sleep disturbances on social functioning was also found in the study of 223 HF patients of Brostrom et al7in Sweden.

Sleep disturbances may have had a larger effect than what was reflected in the statistical analysis, although only 3 sleep variables were selected as predictors of overall HRQOL. In this study, a variety of elements created a vicious cycle in sleep disturbances. When sleep disturbances were initiated by HF symptoms, such as nocturia and shortness of breath, sleep con-tinuity was disrupted, resulting in a longer sleep dura-tion and a feeling of poor sleep quality. The percepdura-tion of poor sleep quality became stronger if the participants could not fall asleep within a short time (normally 15 minutes) because of sleep disruptions. Perceived sleep inefficiency was further pronounced because the time in bed was much longer than actual sleep duration. Participants noted that their sleep no longer refreshed them or restored energy for performing daily functions.

Poor physical functioning results in more sedentary lifestyles, which in turn could reduce their cardiopul-monary tolerance. Perceived lifestyle changes and frequent sleep disturbances could cause mood swings, which could also affect perceptions of sleep quality. Likewise, engaging in few social activities could pro-vide more opportunities for daytime napping, which again could worsen nocturnal sleep quality. Daytime dysfunction, however, resulted in the greater likelihood of falling asleep or dozing off during daytime.10

Education played an important role in HRQOL in this sample. This finding was similar to those reported in previous studies conducted in Taiwan and Hong Kong.15,397Y41That agreement among the studies may support the argument that Taiwanese people with higher education have less difficulty in receiving medi-cal information written in the Chinese-Mandarin language. Accordingly, they have more resources and a greater ability to adjust to their illnesses and changes in life expectations,42 and can use better critical thinking in making decision about their treatments.43 Rockwell and Riegel43 found that HF patients with

higher education performed better self-care. Additionally,

TABLE 5 Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Predictor Variables on Health-Related Quality of Life (n = 125)

Model Predictors B B SE " df F R2 Adjusted R2 R2Change Step 1 1 (Constant) 60.33 3.37 1, 123 12.11a 0.090 0.082 Education 3.46 1.00 0.30a 0.090a Step 2 2 (Constant) 119.00 6.53 2, 122 58.14b 0.488 0.480 Education 2.10 0.76 0.18a NYHA classes j24.32 2.50 j0.64b 0.398b 3 (Constant) 121.84 6.49 3, 121 42.70b 0.514 0.502 Education 2.18 0.75 0.19a NYHA classes j23.57 2.46 j0.62b CCI-number 2.56 1.00 j0.16b 0.026c Step 3 4 (Constant) 124.66 6.32 4, 120 36.88b 0.551 0.537 Education 1.85 0.73 0.16c NYHA classes j21.80 2.44 j0.58b CCI-number j1.97 0.98 j0.13c Sleep quality j4.43 1.41 j0.21a 0.037a 5 (Constant) 128.67 6.54 5, 119 31.12b 0.567 0.548 Education 1.80 0.72 0.16c NYHA classes j21.38 2.42 j0.57b CCI-number j1.98 0.97 j0.13c Sleep quality j3.17 1.52 j0.15c Sleep disturbance j4.62 2.26 j0.14c 0.015c 6 (Constant) 130.05 6.46 6, 118 27.69b 0.585 0.564 Education 1.87 0.71 0.16a NYHA classes j22.50 2.42 j0.59b CCI-number j2.03 0.95 j0.13c Sleep quality j4.57 1.62 j0.21a Sleep disturbance j5.96 2.30 j0.18c Sleep latency 2.99 1.32 0.17c 0.018c

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; NYHA, New York Heart Association. aP

G .01. bPG .001. cP

people who were better at reading and writing Chinese engaged in more positive health-promoting behaviors in a study by Lee and Wang.44 In the current study, participants who could speak Mandarin showed less physical limitation, social functioning, and overall HRQOL than those who could speak Taiwanese only. New York Heart Association functional classification was the strongest predictor of HRQOL. The greater the HF severity, the more likely were the participants to experience lower levels of HRQOL. This finding is con-sistent with previous research findings.15,45Y50 Overall, the participants appeared to have a higher mean overall summary score (70.50 [SD, 19.63]) on the KCCQ than those reported in several other studies (55.9Y66.9), with a great number of participants who had advanced HF.31,48,51,52Although the current study showed an overall summary score similar to that found by Myers et al53(mean, 74.2 [SD, 19]), the 2 studies yielded dif-ferent scores for the domains. For example, whereas the score for physical symptom was the lowest (54.5 [SD, 18]) in the study of 41 American participants of Myers et al,53 it was highest in the current study with Taiwanese participants (74.98 [SD, 21.31]). How-ever, physical symptom also had the highest score in the study of stable HF participants of Green et al.31 The finding suggests that physical domain and symp-toms categories have the lowest level of agreement of all the domains of HRQOL across different cultures.54

Similar to the study of Myers et al,53the participants were less likely to perceive the burden of symptoms than they were for the frequency of the symptoms. An explanation for the high score on symptom burden (indicating low burden of symptoms) may reflect less HF severity within the sample. Indeed, the participants with advanced HF (NYHA classes III and IV) reported lower scores on physical symptom than did the ticipants with NYHA classes I and II HF. Some par-ticipants, however, may have accepted symptoms as part of their life situation. For example, a number of participants, particularly those with valvular heart dis-eases as a precipitating factor for HF and those who had had HF for longer periods, reported that they had become used to living with the symptoms; as a result, they no longer perceived that any symptoms still ex-isted. Among those participants, however, some had observable shortness of breath during the interviews for this study. Participants who did not work or carry out household chores indicated that they perceived little burden from their HF symptoms because they engaged only in daily activities that demanded little energy. Patients, however, may overlook the severity of their symptoms and postpone treatment when symp-toms are gradually getting worse.

Comorbidity was a predictor of overall HRQOL in the current study. The number of noncardiovascular diseases was correlated with HRQOL and not with the

number of cardiovascular health problems. Braunstein and associates55stated that noncardiac comorbidities are highly prevalent in older patients with HF and strongly associated with adverse clinical outcomes, such as hospitalization and mortality. Those findings, how-ever, supported the view that the HF care has shifted from the paradigm in which HF is considered a domi-nant condition to a new paradigm in which HF is considered one of several comorbid conditions.56

Among the 4 domains, participants gave the lowest score to psychological satisfaction domain (65.60 [SD, 24.72]), which is consistent with the score (64.50) reported by Green et al31and the same as that in study

of Myers et al53 (65.2 [SD, 26.0]). Researchers have suggested that psychological problems, particularly depression and anxiety, are natural characteristics of HF, and those characteristics may adversely affect the prognosis of HF.57 For example, recent studies indi-cated that psychological problems may be adverse ef-fects of the activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the sympathetic nervous system.58,59 What-ever the pathophysiological mechanism linking HF to depression, early recognition and treatment of psycho-logical disturbances should be an important compo-nent of HF care. Likewise, Yu and colleagues15found that Chinese HF patients had high levels of psycho-logical distress because of their cardiac dysfunctions and decline in functional ability. During the data col-lection for the current study, we found that several participants viewed HF as a terminal disease and therefore felt that they were useless and waiting to die. Researchers have suggested that both Taiwanese and Chinese patients report more negative effects of illness in the psychological domain than in the physi-cal domain.15,60Further qualitative research is needed to acquire more comprehensive information regarding the effect of HF on psychological status.

Daytime sleepiness was not a predictor of HRQOL. The prevalence of daytime sleepiness (24%) was similar to that found in a study of HF patients (21%),7 but higher than reported in the general population (aged 915 years).61 The finding that daytime sleepiness

was correlated with overall HRQOL is similar to that in the study of Brostrom et al,7 showing that

exces-sive daytime sleepiness was associated with reduced HRQOL in 223 patients with HF. Daytime sleepiness, however, may be independent of sleep disturbance in its effect on HRQOL in patients with HF, in that daytime sleepiness was associated with only 1 domain of sleep disturbance, daytime dysfunction. Given the finding that participants who had greater frequency and burden of fatigue and shortness of breath had more propensity to fall asleep during the daytime, further research with patients with higher NYHA classifications may be useful to help understand the relationship between daytime sleepiness and HRQOL.

Daytime napping was prevalent in 81.6% of the participants. The prevalence and mean duration of daytime napping (82.3 [SD, 50.42] minutes) in this present study, however, were higher than those reported in a study with 60 community-dwelling elderly insom-niacs (64%, 43 [SD, 14] minutes; n = 60).62In contrast with the finding about daytime sleepiness, greater frequency of daytime napping was correlated with poor HRQOL social functioning. Likewise, longer day-time napping was correlated with lower symptom fre-quency, suggesting that daytime napping may slow the occurrence of HF symptoms. This finding is congruent with the use of naps to restore energy, commonly seen among Taiwanese people.62,63Further research is needed, however, to clarify the effects of daytime napping on HF symptoms.

The study has several limitations. The generalizabil-ity of the study findings was limited because the study used a nonprobability sample and cross-sectional design that highlights associations, but not a causal relation-ship. Future research should include more participants with NYHA classes III and IV HF to better understand the effect of HF on HRQOL. Because HRQOL is a multidimensional concept, the use of only 1 instrument may overlook other dimensions of this complex con-cept. Similarly, the use of only a 3-item quality-of-life subscale of KCCQ to measure psychological satisfac-tion is very limited. The low internal consistency re-liability for the PSQI sleep disturbance might have resulted from several sleep conditions that were re-ported by a few participants only, such as feeling too cold or too hot. Adding objective tools to measure sleep disturbances would be helpful to provide more compre-hensive information about this area.

Implications for Practice

Fifteen factors were related to HRQOL, suggesting that nurses should use a holistic perspective to help patients understand and manage the impact of HF on their daily lives. The importance of ongoing screening for sleep disturbances in people with HF is highlighted based on the study findings about the prevalence of sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness among the partici-pants in this study. Early detection of sleep disturban-ces may help health care providers minimize potential poor outcomes and improve HRQOL in people with HF. Because psychological satisfaction had the lowest score among HRQOL domains, routinely assessing HF patients’ emotional status is recommended. Although physical symptoms had the highest score, health care providers should carefully assess patients’ perceptions of HF symptoms as well as use clinical observation skills to evaluate for the presence of symptoms. Patients may have adapted to their symptoms and adopted more sedentary daily activities. They, however, may overlook

the severity of their symptoms and postpone treatment when symptoms are gradually getting worse.

Effective interventions for improving HRQOL should be designed based on the patient’s needs and lifestyle, for example, providing counseling programs for patients who are newly diagnosed with HF or those with worsening symptoms or with sleep disturbances. Developing a support group can offer opportunities for patients and their families to share lived experiences and difficulties with others. Such groups are rare in Taiwan. Spoken explanations are particularly needed for people who are illiterate or elderly. The study findings could serve as a baseline for further longitudinal studies ex-ploring the long-term effects of correlates and causal relationships among the variables in the population with HF, especially for the relationship between sleep disturbances and HRQOL. Future research can com-pare the study findings with other research studies across different cultures and countries.

REFERENCES

1. Heidenreich PA, Spertus JA, Jones PG, et al. Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):752Y756. 2. Podrid PJ, Myerburg RJ. Epidemiology and

stratifica-tion of risk for sudden cardiac death. Clin Cardiol. 2005; 28(11 suppl 1):I3YI11.

3. Heo S, Moser DK, Riegel B, Hall LA, Christman N. Testing a published model of health-related quality of life in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11(5):372Y379. 4. Johansson P, Dahlstrom U, Brostrom A. Factors and

interventions influencing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: a review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;5(1):5Y15.

5. Floras JS. Sympathetic nervous system activation in human heart failure: clinical implications of an updated model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):375Y385. 6. Principe-Rodriguez K, Strohl KP, Hadziefendic S, Pina IL.

Sleep symptoms and clinical markers of illness in patients with heart failure. Sleep Breath. 2005;9(3):127Y133. 7. Brostrom A, Stromberg A, Dahlstrom U, Fridlund B. Sleep

difficulties, daytime sleepiness, and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(4):234Y242.

What’s New and Important

h Taiwanese with HF who experienced better HRQOL were those who had higher levels of education, lower NYHA classes, and smaller numbers of comorbidity conditions and who reported better subjective sleep quality, fewer sleep disturbances, and shorter sleep latency.

h After controlling for education, comorbidity, and NYHA class, 3 sleep variables (subjective sleep quality, sleep disturbances, and sleep latency) accounted for 7% of the variance in HRQOL.

h Correlates of HRQOL that did not act as predictors of HRQOL included age, perceived financial status, concomitant noncardiovascular problems, sleep efficiency, sleep duration, daytime dysfunction, and daytime sleepiness.

8. Erickson VS, Westlake CA, Dracup KA, Woo MA, Hage A. Sleep disturbance symptoms in patients with heart failure. AACN Clin Issues Adv Pract Crit Care Nurs. 2003;14(4): 477Y487.

9. Chen H-M, Clark AP, Tsai L-M, Chao Y-FC. Self-reported sleep disturbance of patients with heart failure in Taiwan. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):63Y71.

10. Chen H-M, Clark AP. Sleep disturbances in people living with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(3):177Y185. 11. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119(14):e391Ye479.

12. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient out-comes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59Y65.

13. Spilker B. Introduction. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1Y10.

14. Fayers P, Machin D. Quality of Life Assessment, Analysis, and Interpretation. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2000.

15. Yu DSF, Lee DTF, Woo J. Health-related quality of life in elderly Chinese patients with heart failure. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(5):332Y344.

16. The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551Y558.

17. Manocchia M, Keller S, Ware JE. Sleep problems, health-related quality of life, work functioning and health care utili-zation among the chronically ill. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(4): 331Y345.

18. Ford DE, Cooper-Patrick L. Sleep disturbances and mood disorders: an epidemiologic perspective. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(1):3Y6.

19. Leung RST, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascu-lar disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(12): 2147Y2165.

20. Mansfield DR, Gollogly NC, Kaye DM, Richardson M, Bergin P, Naughton MT. Controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3): 361Y366.

21. Rao A, Georgiadou P, Francis DP, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in a general heart failure population: relation-ships to neurohumoral activation and subjective symp-toms. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(1):81Y88.

22. Redeker NS, Hilkert R. Sleep and quality of life in stable heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11(9):700Y704.

23. Skobel E, Norra C, Sinha A, Breuer C, Hanrath P, Stellbrink C. Impact of sleep-related breathing disorders on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(4):505Y511. 24. Villa M, Lage E, Quintana E, et al. Prevalence of sleep

breathing disorders in outpatients on a heart transplant waiting list. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(5):1944Y1945. 25. Dement WC. Sleep extension: getting as much extra sleep

as possible. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24(2):251Y268. 26. Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, et al. Objectively

measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(1):5Y16.

27. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

28. Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73Y84. 29. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new

method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitu-dinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373Y383.

30. Radford MJ, Arnold JMO, Bennett SJ, et al. ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clini-cal management and outcomes of patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112:1888Y1916.

31. Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Develop-ment and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart fail-ure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1245Y1255.

32. Pettersen KI, Reikvam A, Rollag A, Stavem K. Reliability and validity of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Ques-tionnaire in patients with previous myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(2):235Y242.

33. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989; 28(2):193Y213.

34. Tsai P-S, Wang S-Y, Wang M-Y, et al. Psychometric eval-uation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Qual-ity Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(8):1943Y1952.

35. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540Y545. 36. Chen N-H, Johns MW, Li H-Y, et al. Validation of a

Chinese version of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(8):817Y821.

37. Patel AR, Konstam MA. Assessment of the patient with heart failure. In: Crawford MH, DiMarco JP, eds. Car-diology. London, UK: Mosby; 2001:5.2.1Y10.

38. Hutcheson GD, Sofroniou N. Introductory Statistics Using Generalized Linear Models. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1999.

39. Lai K-L, Tzeng R-J, Wang B-L, Lee H-S, Amidon RL, Kao S. Health-related quality of life and health utility for the institutional elderly in Taiwan. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(4): 1169Y1180.

40. Lam CL, Lauder IJ. The impact of chronic diseases on the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of Chinese patients in primary care. Family Practice. 2000;17(2):159Y166. 41. Tsai S-Y, Chi L-Y, Lee LS, Chou P. Health-related quality

of life among urban, rural, and island community elderly in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103(3):196Y204. 42. Wang K-Y, Wu C-P, Tang Y-Y, Yang M-L. Health-related

quality of life in Taiwanese patients with bronchial asthma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103:205Y211.

43. Rockwell J, Riegel B. Predictors of self-care in persons with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001;30(1):18Y25. 44. Lee F-H, Wang H-H. A prelimary study of a

health-promoting lifestyle among South Asian women in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Scien. 2005;21(3):114Y120.

45. De Jong M, Moser DK, Chung ML. Predictors of health status for heart failure patients. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20(4):155Y162.

46. Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002;87(3):235Y241. 47. Westlake C, Dracup K, Creaser J, et al. Correlates of

health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2002;31(2):85Y93.

health-related quality of life among lower-income, urban adults with congestive heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003; 32(6):391Y401.

49. Cline CM, Willenheimer RB, Erhardt LR, Wiklund I, Israelsson BY. Health-related quality of life in elderly patients with heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J. 1999;33(5):278Y285. 50. Wang F-T. Quality of Life, Self-care Behavior and Social Support in Patients With Heart Failure [thesis]. Taipei, Taiwan: National Yang-Ming University; 2005.

51. Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, et al. Age, functional capacity, and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10(5):368Y373. 52. Shin G, Tooley J, Southworth M, Dunlap S, Boyer J, Johnson

N. Quality of life and patient preference as predictors for resource utilization among patients with heart failure: interim analysis. Value Health. 2001;4(5):101Y102. 53. Myers J, Zaheer N, Quaglietti S, Madhavan R, Froelicher V,

Heidenreich P. Association of functional and health status measures in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12(6):439Y445. 54. Fox-Rushby J, Parker M. Culture and the measurement of health-related quality of life. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 1995; 45(4):257Y263.

55. Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G, et al. Non-cardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(7):1226Y1233.

56. Havranek EP, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Steiner JF. A broader paradigm for understanding and treating heart failure. J Card Fail. 2003;9(2):147Y152.

57. Skotzko CE. Symptom perception in CHF: why mind matters. Heart Fail Rev. 2009;14(1):29Y34.

58. Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(2):153Y160.

59. Parissis JT, Fountoulaki K, Paraskevaidis I, Kremastinos D. Depression in chronic heart failure: novel pathophysiolog-ical mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14(5):567Y577.

60. Leung K-K, Wu E-C, Lue B-H, Tang L-Y. The use of focus groups in evaluating quality of life components among elderly Chinese people. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(1):179Y190. 61. Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Philip P, Guilleminault C,

Priest RG. How sleep and mental disorders are related to complaints of daytime sleepiness. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(22):2645Y2652.

62. Lai H-L. Self-reported napping and nocturnal sleep in Taiwanese elderly insomniacs. Public Health Nurs. 2005; 22(3):240Y247.

63. Ohayon MM, Zulley J, Guilleminault C, Smirne S, Priest RG. How age and daytime activities are related to insomnia in the general population: consequences for older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(4):360Y366.