法國驅逐吉普賽人:震撼二零一零年法國政治與社會的新聞之框架研究 - 政大學術集成

123

0

0

全文

(2) June 2011 法國驅逐吉普賽人:震撼二零一零年法國政治與社會的新聞之框架研究 The Roma’s Expulsions in France: Framing the Socio-Political Crisis that shook France in 2010. 研究生:孟柯 Student: Christine Moncoquet 指導教授:朱立 Advisor: Prof. Chu Li. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 國立政治大學 國際傳播英語碩士學位學程. ‧. 碩士論文. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. A Thesis. engchi. i n U. v. Submitted to International Masters’ Program in International Communication Studies National Cheng Chi University In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the Degree of Master in International Communication Studies. 中華民國 100 年 6 月 June 2011.

(3) TABLE OF CONTENT. Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………..iv Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………..v Chart……………………………………………………………………………………………...vi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………………......vi. 政 治 大 Research Problem: News Framing of Roma Expulsion in France 立. Chapter 1 Introduction: Immigration in Europe and Roma immigration in France. 1. ‧ 國. 學. I.Immigration Policies and Challenges in Europe. 1. 4. The beginning of immigration in Europe………………………………………………….4. ‧. The difficulty of the Europeanization of national immigration policies…………………..7. sit. y. Nat. Marginalization and social exclusion……………………………………………………...9. io. al. n. II. Immigration in France. er. Integration………………………………………………………………………………..10. Ch. n engchi U. iv. 11. France and the Republican model………………………………………………………..11 Post WWII immigration in France………………………………………………….........12 Demographics……………………………………………………………………………14 Integration and national identity………………………………………………………....16 III. Rumania and the Transitional System. 17. IV. The Roma. 18. Defining their numerous names………………………………………………………….19 Origins……………………………………………………………………………………21. i.

(4) First migrations…………………………………………………………………………22 Medieval times………………………………………………………………………….23 Changing attitudes………………………………………………………………………23 Sixteenth and seventeenth centuries…………………………………………………….24 The Age of Enlightenment……………………………………………………………….25 The forgotten Roma Holocaust…………………………………………………………..25 Under Communist rule…………………………………………………………………...26 In Western Europe……………………………………………………………………….27. 治 政 大 Political mobilization…………………………………………………………………….28 立. Stereotypes and images.………………………………………………………………….29. ‧ 國. 學. V. The Facts, Summer 2010. ‧. VI. The Roma Immigration Debate and News Media. 30. Nat. y. 32. er. io. sit. Chapter 2 Literature Review I.Conceptualizing on Framing Analysis. n. al. Ch. II. Research on News Framing about Immigrants. engchi. i n U. v. 34 35 37. Research about news framing of economic, social or political issues in general………..37 Research on news framing about immigrants……………………………………………39 III. Immigration Frames: Economization Securitization and Nationalism. 42. Economization narratives………………………………………………………………..42 Securitization narratives……………………………………………………………….....43 Nationalist narratives…………………………………………………………………….44 IV. The Research Problem: framing the Roma Immigration Issue in France. ii. 46.

(5) Chapter 3 Method. 49. I.Collection of the Articles for Analysis. 51. II. Choice of Le Monde and Le Figaro. 53. Le Monde………………………………………………………………………...53 Le Figaro………………………………………………………………………...55 III. Identifying the Discourse in the Dominant Three Frames. 57. Sources and responsibility attribution…………………………………………...57 Identifying the frames in news reports: framing devices………………………...60. 立. Chapter 4 Findings. 62. ‧ 國. 學. I.Nationalism Frame. 政 治 大. 64. ‧. Pro-Roma Nationalism Frame: Le Monde……………………………………………….66 Against Roma Nationalism Frame: Le Figaro.…………………………………………..69. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. II. Securitization Frame. sit. Comparing Le Monde and Le Figaro…………………………………………………….72. Ch. i n U. v. 74. Pro-Roma Securitization Frame: Le Monde…………………...………………………...77. engchi. Against Roma Securitiation Frame: Le Figaro…………………………………………..80 Comparing Le Monde and Le Figaro…………………………………………………….81 III. Economization Frame. 82. Pro-Roma Economization Frame: Le Monde……………………………………………84 Against Roma Economization Frame: Le Figaro………………………………………..85 Comparing Le Monde and Le Figaro……………………………………………………86 IV.Sources in the News Articles. 87. iii.

(6) Chapter 5 Conclusion and Discussion. 91. References. 97. Appendix. 104. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv. i n U. v.

(7) Acknowledgments. First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Professor Chu Li for his continuous guidance, his unconditional support, and his kindness. His patience and encouragements have been a great support for me during the research process. He has been. 政 治 大. generous to me in many ways and I learnt more than I could ever say under his guidance. It is an. 立. honor for me to have him as a mentor.. ‧ 國. 學. I would also like to thank Professor Fong Shiaw-Chian and Professor Liu Wen-Ying, members of my Advisory Committee, for every valuable comment and suggestion. They have been. ‧. supportive to me and always ready to respond, taking precious time off their busy schedule.. y. Nat. sit. Last but not least, I would like to show my appreciation to my family and friends, for their. n. al. er. io. encouragement during my pursuit in this thesis research. Their love and friendship has helped me. i n U. v. through the most difficult times of the thesis research and given me the strength to continue.. Ch. engchi. v.

(8) Abstract The Roma’s Expulsions in France: Framing the Socio-Political Crisis that shook France in 2010. Summer 2010 in France was marked by a major socio-political controversy: the expulsions of. 政 治 大 the debate for the audiences. This 立thesis researched how French newspapers are being politicized illegal Roma immigrants. The French news media widely broadcasted the issue, reconstructing. ‧ 國. 學. in reporting the Roma immigration debate. Framing analysis of 240 articles in of Le Monde and Le Figaro, two selected French national dailies of differing political ideology, supported Hallin. ‧. and Mancini’s hypothesis of media instrumentalization and polarization in frame. Le Monde had. sit. y. Nat. a majority of pro-Roma immigration frames (107 articles) and Le Figaro had a majority of. io. er. against Roma immigration frames (76 articles). Moreover, findings showed that Le Monde’s. al. n. dominant frame was the pro-Roma securitization frame and Le Figaro’s dominant frame was the. i n C against Roma immigration nationalism frame. hengchi U. Keywords:. Roma,. expulsions,. immigration,. instrumentalization. vi. framing,. v. French. newspapers,. political.

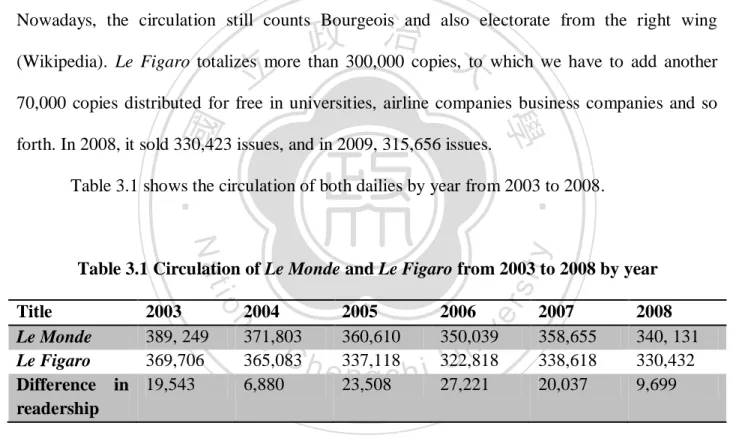

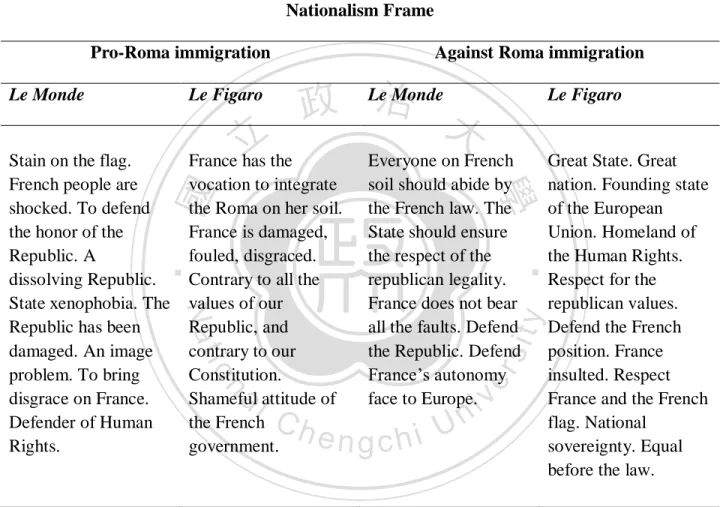

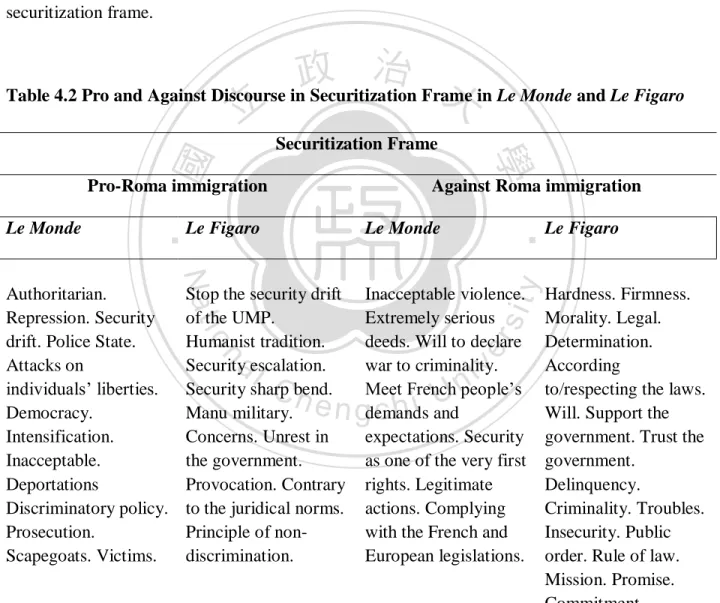

(9) CHART. Chart 4.1 Frequency of frames in Le Monde and Le Figaro………..…………………………64. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大 LIST OF TABLES. ‧. Table 3.1 Circulation of Le Monde and Le Figaro from 2003 to 2008 by year…………………56. y. Nat. sit. Table 4.1 Pro and Against Discourse in Nationalism Frame in Le Monde and Le Figaro………66. n. al. er. io. Table 4.2 Pro and Against Discourse in Securitization Frame in Le Monde and Le Figaro…….76. i n U. v. Table 4.3 Pro and Against Discourse in Securitization Frame in Le Monde and Le Figaro…….84. Ch. engchi. vii.

(10) Chapter 1 Introduction: Immigration in Europe and Roma immigration in France. Research Problem: News Framing of Roma Expulsion in France: During the summer 2010, France went through a major sociopolitical scandal. The issue at stake was the systematic expulsions of immigrants and, more particularly, immigrants from an ethnic minority: the Roma. In this issue, the French President Sarkozy played a paramount role,. 政 治 大. defending the expulsion policy under security reasons and claiming the policy did not. 立. exclusively target the Roma but any illegal immigrant living in unmanaged camps. The problem. ‧ 國. 學. took critical proportions, the European Commission got involved, the European Court of Justice launched a judicial procedure against the French Republic, European politicians were getting. ‧. personal in the matter, and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). Nat. sit. y. of the United Nations asked for a report on the situation. Many Roma grassroots associations. n. al. er. io. mobilized against the expulsion policy and other associations struggling for human rights. i n U. v. claimed there was a major racist problem with France towards her immigrants. The media. Ch. engchi. repeatedly reported news on the issue, feeding the controversy with multiple articles reconstructing the issue according to the media‟s political views. The French population and the immigrants took sides, and demonstrations were organized all over the country. This brief review shows that summer 2010 saw the rise of a major sociopolitical issue not only in France but also in whole Europe. The matter was said to reach the fundamentals of the Republic, i.e. Human Rights and many values upon which Europe is based on. It is true that the general public could hardly understand how a country like France which traditionally defended. 1.

(11) Human Rights could reach the point of a systematic expulsion of one particular ethnic minority. The turnaround was too great and naturally triggered a debate. The media have always played a paramount role in giving an issue a wide audience and shaping people‟s opinion. The Roma issue is no exception, perhaps even more conspicuous as media in Southern Europe, France included, are known to be „politicized‟ or „instrumentalized‟ by varied political ideologies. As forcefully documented and discussed by Hallin and Mancini (2004), the state in Europe “is expected to intervene in media markets to accomplish a variety of collective goals from political pluralism and improving the quality of democratic life” (Hallin. 治 政 大media systems gives leeway to a and Mancini, 2004: 49). This accepted state intervention in the 立 political instrumentalization of the media. The media in Southern Europe are not an autonomous. ‧ 國. 學. institution, and they are often used by various actors as tools to intervene in the political world. ‧. (Hallin and Mancini, 2004: 113).. In such a context, newspapers tend to represent differing political tendencies and can at times. y. Nat. io. sit. play an activist role, mobilizing their readers to support political causes (Hallin and Mancini,. n. al. er. 2004: 98). News reconstructs an issue for the audiences according to the media organizations‟. Ch. i n U. v. own political views and influences the audiences‟ perception depending on how they represent the reality.. engchi. French newspapers are no exception and tend to give precedence to the chronicles and the commentary over mere news reporting, thus reflecting their political roots. Therefore, we expect media of differing political ideologies to hold differing representations of the Roma immigration debate that contribute to polarizing the readership. Hallin and Mancini (2004) have also observed that “in all Mediterranean countries there is an increased tendency to frame events as moral scandals, and for journalists to present themselves as speaking for an outraged public against the. 2.

(12) corrupt political elite” (124). This could account for the French media way of reconstructing the Roma immigration issue as a sociopolitical scandal and their role as defenders of the grassroots society against Sarkozy and the ruling party. The author chooses to focus on the Roma immigration debate because there are very few studies on the Roma immigration in France, and no study analyzing more particularly news reports on Roma in France has been found. The studies usually examine either the cultural dimension of the Roma community and their migration habits understanding them from the. 治 政 about general immigration issues in France without focusing大 on the sole Roma community. The 立 cultural stance, or they assimilate the Roma immigration as a sociopolitical matter in studies. present thesis is thus different than the former studies on Roma and aims at contributing to a. ‧ 國. 學. better understanding of a sociopolitical issue that is taking more and more importance in Europe.. ‧. This thesis will attempt to address the issue of how media represented the immigration issue at stake in the summer 2010 in France by focusing on Le Monde and Le Figaro, two national. y. Nat. er. io. sit. French dailies of differing political tendencies. It intends to examine how differing political tendencies can impact the representations of the Roma immigration issue. The analysis focuses. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. on the frames used by both dailies and strives to identify the dominant frames in news reports. engchi. either favorable or unfavorable to the Roma immigration. The author also strives to demonstrate through the analysis of frames how and to which extent the media were instrumentalized by the political sphere in this immigration issue and how it impacted the audiences‟ opinion formation.. 3.

(13) I.Immigration Policies and Challenges in Europe Migration is intrinsically part of human history. People have always moved, for varying reasons: societal conditions, political problems, economic issues and the desire for better chances in life, and ethnic stakes with undermining minorities‟ policies. In response to these migratory movements, receiving countries have developed means to control immigration under both national and international influences. National policies, stresses Brochmann (1999: 1), are expected to “satisfy social, economic and security needs for. 治 政 human rights protection, and without violating the public‟s大 sense of fair treatment of human 立 immigration regulation, without violating international treaties and conventions for asylum and. beings”. Despite such humanistic ideals, flows of immigrants have always been seen as burdens. ‧ 國. 學. to the economy, the labor market and the social welfare system. As it will be developed later in. ‧. this chapter, immigration also brings its share of fears for national security, national identity, integrity and political stability (Brochmann, 1999). For all those reasons, immigration has now. y. Nat. er. io. sit. grown into one of the most central and complex issues for Western European states. As a consequence, when nation-states make their immigration policies, their main interests are:. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. national security, national economy, demography and social and cultural cohesion. All these. engchi. factors make controlling immigration in the receiving countries a great challenge and a very sensitive issue with always the risk to see arise conflicts between the different ethnic groups present in the country. The beginning of immigration in Europe. These immigration issues are nonetheless rather recent in Europe. Until the French Revolution, the European countries were not considered countries of immigration. As Fahrmeir, Faron and Weil (2005: 3) put it, legislation concerning citizenship and international migration was characterized by immense fragmentation. The French. 4.

(14) Revolution set a new trend: it encouraged the formulation of immigration laws and introduced new techniques of immigration control. Torpey underlines that “the distinction between nationals and foreigners became more sharply defined” (2005: 77). Other European states followed the French example and introduced similar practices regarding control over movement. The eighteenth century was thus merely the beginning of immigration, and migration controls took long before becoming coherent and effective in European countries. In the mean time, “the improvement of the transport infrastructure and the declining cost of travel led to a spectacular increase in migration flows” (Fahrmeir, Faron and Weil, 2005: 4). People could more easily. 治 政 大 and other traveling documents travel, but at the same time the establishment of passports 立 increased the control abilities of the states.. ‧ 國. 學. At the end of the nineteenth century, the way immigration was perceived and discussed in. ‧. Europe changed: “nationalization” was fostered, and migration restrictions dealt with “categories” rather than individual “cases”. The rising influence of lobbies and interest groups. y. Nat. er. io. sit. triggered a public debate over immigration. At the beginning of the twentieth century and following the emergence of the welfare state, migrants had more rights to circulate than they had. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. enjoyed at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but far less social rights while they remained. engchi. on the territory of a state whose citizenship they did not possess” (Fahrmeir, Olivier and Weil, 2005: 6). From that time, the economic climate and sometimes the class of origin were criteria of discrimination. The unrestricted movement and economic liberalism of the end of the nineteenth – beginning of the twentieth century was replaced with economic protectionism after the Great War in many European countries and movements across national borders were hardened (Torpey, 2005).. 5.

(15) After the Second World War, Europe witnessed a big wave of immigration. The countries needed to be rebuilt after the war had devastated the land. France and other European countries welcomed “substantial numbers of immigrants to assist in reconstruction work and to compensate for the country‟s weak demographic growth” (Hargreaves, 1995: 10). These first immigration waves were populations from the Southern European countries moving to France, Germany, and so forth. Soon, the Western states appealed to their former colonial empires to fill the gap of labor shortage. This flourishing period for immigration was put to an end with the. 治 政 thus attitudes towards foreigners reversed and they were大 no longer welcomed. Despite the 立 major world economic crisis that happened in the 1970s. Labor opportunities were reduced, and. degrading economic condition, “most „guests‟ [welcomed during the reconstruction years] were. ‧ 國. 學. not leaving, despite the bans that were imposed everywhere on new immigration” (Ireland, 2004:. ‧. 2).. This world economic crisis was followed by another upsurge in the migration flows. Ireland. y. Nat. io. sit. (2004) notes in his book Becoming Europe that “by the early 1990s, there were more than. n. al. er. fourteen million non-nationals residing within the twelve-member European Community”. Ch. i n U. v. (Ireland, 2004: 2). That represents more than the population of Greece or Belgium which each. engchi. has ten to eleven million inhabitants. People had learnt to live in these multiethnic societies, but this process was not without conflict. Immigrant communities were at the heart of a heated debate over identity, social order, crime and the use of public resources, and Ireland emphasized that “the implications of that challenge are of critical importance” (2004: 3). Cultural differences must be acknowledged, but the question remains as to which point they can be accepted by the host society. The challenge of immigration and the consequent multi-ethnicity is one of tolerance, inclusion, equality and inter-group relations. Integrating the immigrant-origin. 6.

(16) populations and “accommodating [them] appears destined to remain at the top of the list of political priorities (Ireland, 2004: 4). As a consequence of this emphasis on integration, the European states have focused on immigration policies, and more particularly they have worked together on a project of joint-immigration policies. The difficulty of the Europeanization of national immigration policies. In the past couple of decades, immigration policies have undergone „Europeanization‟. This period is characterized by increasing communitarization, that is, increased cooperation between the state members on. 治 政 大 moved toward a political cooperation to create a European Community: a common space for all 立 the political level. The European Union was originally created on economic grounds before it. the European citizens, like one big political entity and with a European identity.. ‧ 國. 學. The first step towards communitarization was the Schengen Agreement in 1995, opening the. ‧. borders inside the European Union space and allowing the free flow of people and goods. As a consequence of this „lost control‟, entry control is supposed to be reinforced at the external. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Schengen borders. One of the unforeseen consequences was the handling of immigration as a security issue (Brochmann and Hammar, 1999). Following the Schengen Agreement, the. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. Amsterdam Treaty signed in 1997 and coming to effect in 1999 signaled the transition from. engchi. informal intergovernmental cooperation to incorporation within European-level policymaking structures. It contained directives for police and justice cooperation to deal with racism and xenophobia. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) is in charge to make sure these agreements are enforced by the member states, protecting the immigrants‟ rights when a member state would violate the agreement. The ECJ is the highest court in the European Union in matters of European Union law. It is in charge of interpreting and enforcing European laws across all EU member states. The European Commission has worked since the European Council meeting in. 7.

(17) Tampere -1999- toward a common legal framework for admission and residence. The Tampere Program adopted during a “European Council summit in Tampere in 1999 defined a five-year action program on the central measures of a common European immigration policy” (Ette and Faist, 2007: 6). However, the Tampere Program was hindered by the 9/11 aftermath: internal security and control aspects of migration policies were reinforced both in the national and in the EU‟s migration policy. After 2001, developments for a more liberal and comprehensive idea of migration were stopped (Bendel, 2007).. 治 政 大 by the European Commission. of the ECJ, the join-immigration policies‟ initiative is conducted 立. Before the immigration policies become laws at the European level and fall into the domain. The latter faces many obstacles in this project. The first difficulty is that the European. ‧ 國. 學. Commission merely addresses draft directives with vague and non binding references allowing. ‧. the member states to enforce the directives with their own interpretation. Many complain that the European Commission‟s harmonization of policies results in more talks than actions, lacking a. y. Nat. er. io. sit. real momentum to coordinate national policies. Nonetheless, a common agenda of immigration inclusion, promotion of economic and social cohesion has taken shape at the EU level, and the. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. European Court of Justice acts as a regulation body in charge of reminding the member states of. engchi. their commitment. However, the European-level initiatives grew in importance since their first efforts of policies‟ harmonization and nowadays local official look to EU-level policies when formulating their own. As a result we can say that Europe is on the track of a liberal multicultural consensus. After all, multiculturalism is the proper aim of the European Union; otherwise it would have remained at the level of Economic European Union. It is the strength and the richness of the Union to gather all these different cultures in own single political system. Member states need now to set down and harmonize rules on immigrants‟ rights and. 8.

(18) responsibilities, the challenge being that every state is reluctant to leave the European Commission impinge on their national prerogatives. A balance needs to be found on that ground. Nonetheless, a trend towards greater European regulation can be observed in the last thirty years (Ette and Faist, 2007). Powers have increasingly transferred from the national to the EU level. The Treaty of Maastricht and the Treaty of Amsterdam prove that the EU has gained competence in an area that has traditionally been strongly linked to aspects of national sovereignty. Ette and Faist (2007) attribute this successful shift to the fact that the European level offers a new venue. 治 政 大courts. wing parties, economic actors, ethnic groups and constitutional 立. to national officials to circumvent national constraints such as public opinion, extreme right-. Marginalization and social exclusion. Aside from all these European efforts to. ‧ 國. 學. „europeanize‟ immigration policies, every state member faces its own issue brought by. ‧. immigration. Europe‟s major cities now all have at-risk neighborhoods in which the at-risk populations are in a large proportion of immigrant-origin prompting fear that ethnicity has. y. Nat. er. io. sit. become a major axis of social exclusion. Mahnig contends that in the early 1980s, Paris neighborhoods with high concentrations of migrants began to be regarded as ghettos. The new. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. word “ghettoization” in use nowadays aims at describing the critical situation in the suburbs. engchi. where a majority of inhabitants are immigrants regrouping in these neighborhoods because they would often feel unwelcomed in other parts of the city. This “ghettoization” brings many social and security problems to the governments. In Paris‟ area, “the spatial concentration of migrants in certain parts of Paris region was to remain a political issue throughout and beyond the 1970s” (Mahnig, 2004: 20). Decentralization with immigrant population sent to the suburban areas expose minorities to greater discrimination and exclusion. Spatial concentration and segregation have contributed to the accumulation of social problems in particular neighborhoods that the rest. 9.

(19) of the population ignores since these problems remain confined to some particular areas. It is not certain that the immigrants are responsible for the consequent conflicts, but instead results of marginalizing in one same place all the social ills at once. It could also be an opportunity for immigrants to create social networks supportive to immigrants belonging to a same ethnicity: “recent work in Europe has tended to stress the contributions of associational activity to the building of useful social capital” (Ireland, 2004: 11). Too often, the term „insecurity‟ has been seized by officials playing on fears of nationals for electoral reasons, fostering cleavages between immigrant populations and nationals. The „zero. 治 政 大of urban violence have provoked tolerance‟ policies implemented in the 1990s after outbreaks 立 rising anxiety among nationals over minority populations. Another fear nationals have is that the. ‧ 國. 學. new cultural diversity might hinder social bonds and shared values that unify European societies,. ‧. shattering into pieces national identities (Ireland, 2004).. Integration. In response to these marginalization problems, European state members have. y. Nat. er. io. sit. strived to find appropriate policies to respond to the immigrants‟ presence. They aim at finding solutions to help the integration of the immigrant-origin populations, but the efficiency of these. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. policies are difficult to assess. Integration has become nowadays a paramount issue in public. engchi. policy. As Ireland (2006) argues, the concept used to be defined in terms of how well particular individual immigrants or groups participate in the majority society, but how it has come to apply as well to the cohesiveness of the entire host society. The challenge for integration is to find the appropriate policies that will meet the immigrants‟ special needs while at the same time not further aggravating segregation and marginalization of these ethnic groups. After many debates, experiences and mistakes, European officials seem to have finally understood integration less as immigrants fitting into the host society and more as immigrants fitting themselves into host. 10.

(20) societies that were transformed in turn (Ireland, 2004). Liberal multiculturalism appears to be ascendant nearly everywhere: this approach emphasizes immigrants‟ individual rights as well as their assimilation. As Ireland stresses, “equal access is vital to having immigrants avoid social exclusion. But some types of service provision intensify it, isolating immigrants from the rest of the community and hindering their integration into the educational system and the labor market.” (2004: 228).. 治 政 France and immigration in France share the same patterns大 as most European member states, 立 II. Immigration in France. facing issues of appropriate immigration issues, marginalization of the immigrant populations,. ‧ 國. 學. and their integration. Immigration in France started even earlier than in the other European. ‧. states; it started in the middle of the nineteenth century. However, it is not a nation of immigrants with an immigration founding myth like in the US.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. France and the Republican tradition. Even though France is not a country with a tradition of immigration, the ideal that all men are equal, no matter their origins, is deeply embedded in. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. the French national subconscious. France early accepted foreigners as settlers, immigrants, and. engchi. even as citizens, as part of the Republican tradition that stem from the French Revolution (Hollifield, 1999). The famous French motto „liberté, égalité, fraternité‟ (liberty, equality, fraternity) comes from that same tradition. Republicanism is strongly egalitarian and anticlerical, stressing popular sovereignty, citizenship and the rights of man (Droits de l’Homme). Hollifield (1999) stressed that even though immigration and integration are closely associated with the French Republican tradition, they are not crucial to French national identity because of the confidence in the Republican model‟s capacity to integrate and absorb. 11.

(21) newcomers. The historical Republican model gave immigration a greater legitimacy compared to other receiving countries of Western Europe. It called to universalism, egalitarianism, nationalism and laïcité (secularism). Post WWII immigration in France. As we have already said above, the European countries pursued expansive immigration policies in the post World War II period. The French government was no exception and opened its borders to satisfy the labor needs of industrialization and the nation‟s reconstruction after the war. It was a period of extraordinary economic growth that became known as the Trente Glorieuses –thirty glorious years of economic growth.. 治 政 Another reason for allowing this immigration wave大 was the decrease of the French 立. demographics. France had entered in the demographic transition earlier than its neighbors, and it. ‧ 國. 學. was in desperate need to boost its aging population. The immigration flows first originated from. ‧. countries with a Catholic majority: Italy, Spain and Portugal. After the independence of Algeria in 1962, the composition of ethnic flows changed to a majority of North African Muslims. These. y. Nat. io. sit. latter flows questioned the capacity of the Republican model to integrate and absorb the new. n. al. er. Islamic populations. Hargreaves noted in his study that in a 1991 poll, “some 49 percent of those. Ch. i n U. v. questioned […] said Islam was so different from the prevailing norms in French society that it. engchi. made the integration of Muslim immigrants impossible” (Hargreaves, 1995: 157). This period of growth was followed by a great economic recession and an unemployment wave that hit France in the 1970s. In 1974, the French administration stopped immigration. However, as Hollifield (1999) noted, cutting immigration proved to be difficult since instruments of control had not been yet developed by the French state. At that stage, labor immigration was stopped, but family reunification was harder to control for humanitarian and social reasons, and it remained the main immigration flow throughout the 1970s with over 500,000 immigrants per. 12.

(22) year from 1974 to 1980. In that same period of time, the French government shifted from an open to a more closed immigration regime. We understand that French immigration policies underwent many changes depending on the historical and economic background but also depending on the political tendency of the ruling government. The socialist government of 1981 was by definition more liberal towards immigrants. On the other hand, the conservatist right-wing proved committed to stricter immigration control.. 治 政 immigration, integration and national identity. From 1986大 to 1993, the French government 立. Since the 1980s, French politics seemed to continuously be in a state of crisis over issues of. launched a psychological warfare against immigrants: France remained open to legal. ‧ 國. 學. immigration, but everything was done to discourage economic immigration. Getting families of. ‧. immigrants back together was made harder than it used to be, working permits were more difficult to obtain and so forth. In 1991-1992, there was another severe economic recession and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. as usual, immigration was linked to the recession and the high unemployment rates. Immigration policies remained at the core of French politics throughout the 1990s (Hollifield, 1999), with the. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. government tending towards „zero immigration‟ during that period of time. The immigrants‟. engchi. civil liberties were restricted: their civil (equal protection), and social (welfare) rights were constrained. Hollifield (1999) underlines that altering social rights of immigrants and foreigners puts at risk the Republican state because the state runs the risk to undermining its legitimacy and alienating its own citizens. Besides, the „zero immigration‟ trend, although reducing the annual rate of legal immigration, gave leeway to illegal channels of immigration. In 1993, 8,700 individuals were caught trying to enter the country illegally, and in 1996 their number had jumped to 12,000.. 13.

(23) Another challenge to the Republican model was the increasing cooperation between European states towards common immigration policies such as the Schengen agreement in 1985. The Schengen Agreement concerned “cooperation on the mutual abolishment of internal border controls and the development of compensating internal security measures” (Ette and Faist, 2007: 6). French immigration policies witnessed another shift in 1997, when the socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin advocated for a return to a more liberal and dignified immigration policy. 治 政 大 were much lower than in the Nonetheless, the immigration rates in the 1980s and the 1990s 立 without having to renounce to the French values or compromising the social balance.. 1960s and the 1970s, and a lot lower than other European countries.. ‧ 國. 學. The law of July 27, 1997 reestablishes the soil right for the acquisition of the French. ‧. citizenship. There are no more conditions to obtain the citizenship for anyone born on French territory: “the acquisition of French citizenship is a privilege, not a right, and it should be. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. (Hollifield, 1999: 69).. sit. withheld from those who have not made a clear commitment to the French nation and society”. Ch. i n U. v. However, November 26, 2003, a new law passed making the delivery of the residency card. engchi. subject to an integration criterion. The example of these two last laws, in 1997 and 2003 proves the tendency of French immigration policies to vacillate between two opposite trends: one more liberal and generous to immigrants, and the other more closed. Demographics. After several waves of immigration and despite all the ups and downs in immigration policies, the French population is nowadays composed of a wide mix of ethnicities. Statistics of the Institut National d‟Etudes Démographiques (INED) or „National Institute of. 14.

(24) Demographic Studies‟, estimate that thirteen million of French citizens, or about a fifth of the population, are of non-French origins. In the 2004 and 2005 census, 4.9 million immigrants were counted. That is 8.1 percent of the population in France. In contrast, there were 4.2 million immigrants in 1990. Sixty percent of the immigrants are concentrated in merely three regions. There were four immigrants on ten people living in Ile-de-France (Paris and the surrounding region), one on ten in the Rhône-Alpes region, and one on ten in Provence-Alpes-Côte d‟Azur region. There are few immigrants in the Western. 治 政 大 data from 2004). regions of Brittany, Basse-Normandie and Pays de la Loire (INSEE, 立. part of the country, with immigrants representing less than three percent of the population in. About 960,000 immigrants entered France between January 1999 and middle 2004, and. ‧ 國. 學. almost a quarter of them were coming from countries belonging to the European Union. In 2004,. ‧. 140,033 people immigrated to France, and slightly less in 2005 with 153,890 immigrants. With these numbers, France has a very low rate compared to other European countries. The net. y. Nat. er. io. sit. immigration rate is 0.66 migrants per 1000 population a year. That is twice and a half less than the average of other European states. This can be explained by a higher fertility rate than for. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. example its German and Spanish neighbors and a labor market less dynamic than the UK for instance.. engchi. Nowadays, one immigrant out of four has a university degree, or four times more than in 1982 (Catherine Borrel, from the Statistics and Immigration unit of the French National Institut of Statistics and of Economic Studies (INSEE), data from 2004). It has been found that immigrants come to France on three major grounds: their country has economic difficulties and they are seeking for a better life; they help boost French decreasing demography; and familiarity. 15.

(25) with the French language in some countries –especially former French colonies- makes it easier for immigrants to come to France. Integration and national identity. So many immigrant populations of different ethnic origins mixing in a country that traditionally had little immigration represent a challenge for the French state. The alternation of borders opening and borders closure proves the difficulty of not only controlling immigration but also dealing with the presence of these immigrant populations. The integration of the latter in the French society remains until nowadays an important issue.. 治 政 integration was paramount on the national agenda, with 大 political parties and the electorate 立 Immigration policies were hotly debated through the 1980s and the 1990s. The issue of. increasingly polarized on both immigration and integration issues.. ‧ 國. 學. The economic downturn provoked a rising tide of xenophobia in the 1970s that resulted in. ‧. the electoral breakthrough of a neo-fascist, xenophobic and racist movement in 1984: the Front National (FN). The discourse of this new political party mixes xenophobia, extreme nationalism. y. Nat. io. sit. and anti-Semitism, with appeals to the economic insecurities of the French working class. Under. n. al. er. the FN attacks, “immigrants were seen as the cause of the economic and cultural decline of the. Ch. i n U. v. French nation, provoking a loss of confidence in the Republican model” (Hollifield, 1999: 67).. engchi. The rise of the FN heightened a sense of crisis and triggered a debate over French national identity. Public opinion polls of 1988-1989 showed that about a third of the electorate had sympathies for the FN‟s position on immigration. France‟s economic situation in 2010 was not great consequently to the 2008 economic world crisis. However, the economic aspect does not seem to have been the focus in the 2010 Roma controversy. The reasons will be explained further, in the results section.. 16.

(26) Immigrants have been stigmatized and marginalized. Many of them concentrate in particular areas that are similar to ghettos and in particular occupations, giving little possibilities to improve their quality of life. These so-called ghettos thus concentrate many economic and social problems such as unemployment, lack of education opportunities, delinquency, and criminality. Immigrants encounter great difficulties integrating the labor market and the French society. They suffer from discrimination in the hiring process and in most aspects of their lives. Hargreaves (1995) argued that the formal rights of immigrants have been limited in many spheres. “In unofficial ways, public authorities have often discriminated against minority ethnic groups”. 治 政 (Hargreaves, 1995: 197). Moreover, many do not speak the大 national language when they first 立. arrive and they live in communities similar to those of the country of origin, which is another. ‧ 國. 學. hindrance to integration in the society of the majority. Means of integration are profession,. ‧. school –French norms and values are taught to immigrants‟ children at school, migrants‟ associations, and social and political mobilization.. y. Nat. io. sit. Some states have adopted policies designed to favor disadvantaged groups. This „positive. n. al. er. discrimination‟ aimed at redressing inequalities. However, “in France, such approaches are. Ch. i n U. v. almost universally condemned as Anglo-Saxon devices leading to quotas, ghettos and. engchi. communitarianism, i.e. ethnic separatism” (Hargreaves, 1995: 200. III. Rumania and the Transitional System In the most recent years the main immigration waves have not been coming from Spain or Italy anymore while immigration from Maghreb countries and other former colonies remains strong. For instance, the number of immigrants from former French colonies has increased 45 per cent since 1999 (INSEE statistics, 2004). However, the same institute of statistics noted that the. 17.

(27) number of immigrants coming from European countries like Rumania and Bulgaria has significantly increased. Rumania and Bulgaria have joined the European Union in January 2001. According to the European Union Agreements, their nationals should benefit from free movement of people, working and dwelling in any other member state. However, their entry is subject to a transitional system until the end of 2013. Until that date, nationals of these two countries can freely enter the French territory without a visa, but they need to apply for a working permit if they wish to work. 治 政 大they have to prove having enough and Bulgarian nationals in the territory: when entering France, 立. and settle down. Moreover, France has added one economic condition to the entry of Rumanian. funding to sustain themselves. Otherwise, entry on the territory can be denied to them.. ‧ 國. 學. In short, this transitional system allows Rumanians and Bulgarians to travel in other member. ‧. countries and stay for maximum three months. Beyond that period of time, they need to either leave the country or find an occupation with the corresponding working permit. Based on that. y. Nat. er. io. sit. law, expulsions of Roma have shifted from two-three thousand per year before 2007 to eight thousand and more in 2008 and onwards. The escorts back to the borders are mainly voluntary. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. because the French government grants a three hundred euro bonus to each adult and one hundred. engchi. euro bonus for each child, and furthermore pays for the airplane ticket back to their country of origin.. IV. The Roma Among the Rumanians and Bulgarian immigrants arriving in France and other Western European states, the case of the Roma ethnic minority is of particular interest. Even in both countries Rumania and Bulgaria they are considered to have a status aside and they very often do. 18.

(28) not enjoy the same benefits as the other nationals. Moreover, their type of migration is different than the one of other Rumanians and Bulgarians. In order to understand their pattern of migrations, we need to understand who they are, where they come from, and what their way of living is. The history of the Roma ethnic minority is one of endless persecution, suffering and forced assimilation. Host populations have at all times perceived them as threatening, and tried to annihilate them, either through enslavement, banishment, genocide, or more mildly but none the. 治 政 大constraints, historical events and life have survived. They sure had to change and adapt to local 立. less radical in its intentions, through forced assimilation. And yet, the Roma spirit and way of. economic downturns in order to survive, but the essence of the spirit remains the same. After. ‧ 國. 學. trying for centuries to assimilate them and force into conformity, the host population can only. ‧. but note that they have failed in that. The Roma have preserved a distinctive identity centuries after their first arrival in Europe, even when they have merged in the host society.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Defining their numerous names. Rom is an endonym, which means it is the word Roma people use to call themselves. The term rom was chosen during Roma World Congress held in. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. London in 1971. Literally it means „man‟ or „husband‟. A flag and a slogan were also chosen at. engchi. that Congree: „Opre Roma‟ (Gypsy rise!) Rom is the singular, and Roma is its plural, but most people call them „Gypsies‟, the name given to them by the outsiders (Fraser, 1992). Rom has two meanings. In the first, it is a generic term designating all ethnic groups originating from India and which arrived in Western Europe as early as in 1419. Comprised in his generic sense, it encompasses Sinti, Manouches, Gypsies (or Kale), and Roma for the most notorious ones. In this sense of the term rom, there is no relation to Rumania. The second meaning refers to the groups of a more recent wave of migration coming from the Balkans. Their. 19.

(29) common denominator is the Romani language. Their speech is “much influenced by the impact of their ancestors‟ long stay in Rumanian-speaking lands, hence their designation as Vlach (=Wallachian) Rom” (Fraser, 1992: 8). (Wallachia is the ancient name of a Rumanian province). These Vlach Rom are subdivided into several different tribes: Kalderash, Lovara, Curara, Ursara and so forth. Historically, they have been called many names. In the Medieval times they were called „Egyptians‟ because they pretended to come from Little Egypt; then in the fifteenth century they were called „Bohemians‟ as their nobles claimed on their titles to come from Bohemia, and. 治 政 大are all names given by outsiders. „Gypsies‟, a Spanish term that stem from „Egyptian‟. These 立. Nowadays, it is under the term „Gypsy‟, largely pejorative because of its racial connotation, that. ‧ 國. 學. they are often referred to, and under the new one: Rom. Only the latter has been chosen by the. ‧. Roma themselves to refer to their ethnic identity (Fraser, 1992: 317).. In France, as in some other countries, one more term is used to refer to all peripatetic groups:. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Gens du voyage or „Travellers‟. This term refers to anyone with a nomadic way of life and it is not limited to the Roma alone. It is more neutral and politically correct. It reflects the modern. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. concern to avoid discrimination on grounds of race. But none of the terms used by outsiders is. engchi. actually free from ambiguity. The first name referring to them in the Balkans stems from a Macedonian term, Athinganoi, which comes from the Byzantine Greek Athinganoi or Atsinganos. Other terms used in Europe in the nineteenth century stem from that origin and give Zingaro in Italian, Tsigane in French, Zigeuner in German, Cigani in Yugoslavia and so forth (Association Migration Conseil, blog, 2010). Romanichal, which simply means Rom people, is most in use in the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia. On the continent, there are many names for the old-established Gypsies: calé („blacks‟) in Spain and Southern France, Kale in Finland, Sinti. 20.

(30) in Germany, and manouches in France. There are numerous terms in use to call them, which proves the diversity of this fragmented nation. The way these groups refer to themselves is mutually exclusive. This quick description supports Angus Fraser‟s (1992) idea that Gypsies can be called a „people of Europe‟ because the long association and intermingling with other people in Europe have indelibly marked their language, culture, and society. They are present in every European country, and what we Fraser calls „pan-Europeans‟.. 治 政 大 migrations. It is necessary to Europe and arrived in Western Europe in the most recent 立. The present study will deal with the more precise group of Roma originating from Eastern-. distinguish all those sub-groups in order to understand precisely whom we are talking about. Few. ‧ 國. 學. people are aware of these important variations and there is a tendency to confuse all these groups. ‧. in one, using the name of one group for the other, interchangeably. The confusion in the media betweens the numerous terms in use contributed to the overall confusion about the issue of. er. io. sit. y. Nat. summer 2010.. Origins. There are few written records of the Roma presence in Europe. They have been. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. written by outsiders or gadje, as Roma call them, often in ignorance, prejudice and. engchi. incomprehension. It is said that the Roma Diaspora took place at some time before the ninth century AD. Nowadays most scholars seem to agree with the theory saying that Roma are originally from India. There are linguistic evidence linking the Romany language to Indian dialects, and more particularly, Hindi. Genetics studies have given support to the theory of racial affiliation when finding a blood relationship between Roma and tribes of the Indian subcontinent. The limit of such a study, however, is met by the great miscegenation the Roma have undergone through time and through their numerous migrations. Fraser noticed that “Gypsies. 21.

(31) [aka Roma] have undergone racial admixture and the gene pool of any particular cohort may be very mixed (1992: 24). The first person to make the connection between Romani language and Indian dialects is a Hungarian theologian, Istvan Wali, back in 1753. Two others scholars, Johann Rüdiger and Jacob Bryant, studied that connection between Romani language and Indian as well. Rüdiger published his findings in 1782, but these reached a little audience. It is through the publication of H.M. Grellmann who made a synthesis of these findings that they reached the wider public in. 治 政 大 consideration of authorities that time by a passion for exotic peoples, but also by the practical 立 1783. Angus Fraser points out that this interest in the Roma their origins had been motivated at. eager to understand them. The idea was to understanding them through understanding their. ‧ 國. 學. origins, aka through studying their language. However, the origins of the Roma remain rather. ‧. ambiguous, despite repeated efforts to trace back their migrations.. First migrations. The Roma are believed to have left India at different times sometime. y. Nat. er. io. sit. before the ninth century. They first arrived in Persia, then Armenia. In 1071 we find them in the Byzantine Empire after the Seljuks invaded Armenia. From there they crossed to Greece around. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. the fourteenth century, and by the end of the fourteenth century they were widely established. engchi. throughout the Balkan provinces where they had arrived through Transylvania. In Wallachia (a historical and geographical region of Rumania) and Moldavia the Roma first sold their services as serfs paying tribute to the local monasteries. However, they were before long turned into slaves, and this condition continued until 1856, when their liberty was finally fully restored. Fraser recounts the Roma‟s predicaments in Wallachia and Moldavia where “the Gypsies were systematically turned into slaves” (Fraser. 1992: 57).. 22.

(32) Medieval times. The first migrations of the Gypsies that researchers have reconstructed start from India and stop in the Balkans. We have to wait until the Medieval time to finally find them in Western Europe. The first mention of Roma in Western Europe dates from 1417. They arrived from the Balkans in groups of 30, 60 or even 100 people, claiming to be pilgrims and asking for alms. At that time they were still treated with a measure of consideration. Their unique physical appearance (dark skin) and attire (large earrings) attracted people‟s curiosity. The Roma claimed to come from Little Egypt and to be under a seven-year penitence to expiate the sin of the. 治 政 this excuse the local lords, nobles and kings delivered them大 letters of protection and the Roma 立 forbearers who refused to give asylum to the Holy Family during Its flight from Egypt. Under. received shelter, food and even money. At that time, it was still accepted the Roma had the right. ‧ 國. 學. to manage their own affairs (Fraser, 1992: 70).. ‧. Changing attitudes. A few decades to a century after Roma‟s first arrival in Western Europe, public attitude towards them deteriorated and decrees and laws were enacted against. y. Nat. er. io. sit. them, banishing them from the countries, allowing physical punishments against them and physical and economic punishments against the local people helping them. They were seen as. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. undesirable, a political threat (people thought they were spies for the Turks) and troubling the public security and the social order.. engchi. Fraser analyses the change of attitudes towards the Roma was to be found in the religious climate where pilgrims did not have the same status as before; people grew tired of seeing the same groups of Roma regularly coming back; and finally settled people do not trust nomads. They “represented a blatant negation of all the essential values and premises on which the dominant morality was based” (Fraser, 1992: 127). That was true in the fifteenth century, and it. 23.

(33) still is true in the twenty-first century. Roma are anti-conformists, and this disturbs the established order, and settled people seem never be able to forgive them that fact. The Roma livelihood was described as begging, fortune-telling, horse-dealing, metalworking, healing, music and dancing. Theft was another recurrent theme reported by the chroniclers. The truth is that in this atmosphere of suspicion, the Roma could hardly find regular livelihoods. The peasants were not in the habit of employing casual labor at that time, guilds regulated crafts and trades, and commerce was tightly controlled. The Roma, perceived as a. 治 政 大legitimate services to the settled entertainment. Fraser underlined that “when Gypsies offered 立. dangerous and unfair concurrence, were left with the small services and minor trading and. population, they were at risk from the ill-will attracted by transient traders and artisans who. ‧ 國. 學. violated local monopolies” (1992: 129). Roma faced a serious contradiction: accused of violating. ‧. the local monopolies when trying to make a decent living, Roma were yet criticized for being lazy, unproductive, beggars and thieves.. y. Nat. io. sit. Sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As time passed, the Western European countries. n. al. er. started getting annoyed at the Gypsy‟s presence. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, all. Ch. i n U. v. European countries were taking repressive measures against the Roma. They were viewed as. engchi. criminals because of their position in society: there were severe racial prejudices against them and religious hostility. The Church tried repeatedly to excommunicate them and those who helped them or went to them for fortune-telling. Besides expulsions, the governments had come with new measures: the Roma were sent to the galleys or to one of the overseas colonies to be used as manpower. Another means was to force them to assimilate with the local populations. “They were forbidden to set themselves apart in dress, speech or occupation. […] Marriage between Gypsies were forbidden [and] Gypsy children over the age of five were to be taken. 24.

(34) away and brought up in non-Gypsy families” (Fraser, 1992: 157). By the middle of the seventeenth century sedentarization was much achieved. The Age of Enlightenment that opened so many minds brought little change how Europe perceived and dealt with the Roma. The Age of Enlightenment. The eighteenth century witnessed social, political and economic changes. Fraser noticed that these changes stirred up “new currents of migration, both within European countries and on a global scale” (1992: 190). The Roma were not the only people on the roads. At that period, the Roma population in Europe was assessed at 700,000 to 800,000. 治 政 大 “in the than ever before. Nonetheless, 立. individuals. The Industrial Revolution that largely occurred between 1815 and 1914 brought into the society larger changes. face of urbanization,. industrialization and other European pressures, Gypsies showed themselves able to maintain. ‧ 國. 學. their autonomy” (Fraser, 1992: 221) The Roma failed to conform to the imperatives of the. ‧. Industrial Revolution as they were part of an informal economy, and they were soon perceived as outcasts who had been overlooked by the industrial culture.. y. Nat. io. sit. The forgotten Roma Holocaust. A consequence was the resurgence of dormant notions. n. al. er. about the Roma being thieves and criminals. The ideology there were a „higher‟ and a „lower‟. Ch. i n U. v. races came up at that time (in the 1850s). The Nazi party saw in the Roma a racial problem that. engchi. needed to be solved. During the Second World War, when they finally got the means to apply their ideology, the Roma were taken to work camps along with the Jews, and from 1943 they were included the infamous “final solution” that brought the death camps. All the countries under German rule applied the directives concerning Jews and Roma. The France under Vichy‟s government contributed too. “30,000 Gypsies and other „nomades‟ [were] guarded by French police and military. Eventually, many of them were deported to concentration camps” ({Fraser, 1992: 265). The biggest numerical losses were in Yugoslavia, Rumania, Poland, the ex-USSR. 25.

(35) and Hungary. It is however impossible to assess the exact number of casualties. “Tallies of the Gypsy victims who died in Europe during the war range from about a quarter of a million to half a million and more” (Fraser, 1992: 268). And those who survived most carried physical or mental marks of their experience. While the Jews‟ genocide was quickly acknowledged and compensations given, the Roma‟s sufferings and persecutions were not. For many years, they were denied the recognition of the genocide they suffered. This is why many scholars call the Roma Holocaust the “Forgotten Holocaust”. German courts made prevail that Roma were not being persecuted on racial grounds.. 治 政 大 against Roma had started Eventually, in December 1963, a Court accepted that racial persecution 立. back in 1938 and from then on the Roma Holocaust was finally acknowledged for what the. ‧ 國. 學. tragedy it really was (Fraser, 1992: 269).. ‧. Under communist rule. After WWII, the Roma were in a large majority concentrated in the communist countries. Communist regimes‟ handling of Roma was typified by twists and turns.. y. Nat. io. sit. “Throughout the Communist bloc, with the partial exception of Yugoslavia, the Gypsies wre. n. al. er. subject to a systematic assimilatonist campaign” (Stewart, 1997: 5) because non-conformity was. Ch. i n U. v. incompatible with the regime‟s plannification and ideology. Communists had no ill-will in their. engchi. attempt of assimilation, as they were convinced they were doing the Roma a favor. They thought “the Communist society could provide a home for the Gypsies and so integrate them into „normal‟ life” (Stewart, 1997: 6). After realizing soft assimilation was impossible to overcome the Roma‟s way of live, they became more coercive and tried by means of force to demolish the Roma identity. They enforced school attendance and the settlement of nomadic people. The Communist did not imprison the Gypsies or kill them, but the ultimate aim could still be called. 26.

(36) genocide in that it sought for the total disappearance of the Gypsy ethnic identity, by merging them into the mass. After the fall of Communism, the Gypsies have become the scapegoats throughout the region because they were considered troublesome and „antisocial‟. Communists saw their way of life „anarchic‟ and „unproductive‟ (Stewart, 1997: 3, 6). The Gypsies suffered from the social and economic disintegration that affected the whole area since 1989. For instance, in Hungary, sixtyfive percent of Roma men were unemployed.. 治 政 大 and rejection. In the 1960s either. There too, they faced many problems of discrimination 立. In Western Europe. In Western Europe, the situation of the Roma was not an ideal one. already, a new westward upsurge out of the Balkans happened. These new groups were in. ‧ 國. 學. majority illiterate and could hardly find a job in such conditions. Most Western European. ‧. countries felt concerned with human and social problems: the camp sites issues and education. The governments try to improve the poor living conditions as many of the Roma who had chosen. y. Nat. er. io. sit. to live a sedentary life lived in shanty towns, and the peripatetic had to use camp site like rubbish tips with no water supply or sanitary facilities. From 1969 onwards, the Council of Europe. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. adopted a succession of resolutions and recommendations, urging the member governments to. engchi. put an end to discrimination, to do something about camping grounds and housing, and to promote education and health and social welfare. From 1977, the United Nations on Human Rights turned its attention to discrimination against the Roma. In the 1980s, emphasis was put on the education of Roma children, as only thirty to forty percent regularly went to school. Illiteracy rate among adults in the members of the European Union had an average of fifty percent, and was as high as eighty percent in some places. Fraser sums up the difficulties the Gypsies had to face: “a high proportion was illiterate and uneducated and often spoke little of the local language,. 27.

(37) and also because they were Gypsies, any regular work would have been difficult to find” (1992: 272). Empowering them, giving them the means to speak for themselves and find good jobs starts with literacy. In the 1990s, there were new waves of immigrants, including Roma from Rumania. The unrest over migration, both legal and illegal in all Western and Central European countries led some countries like Germany and France to strike repatriation deals with Rumania. Fraser (1992) reports that “in 1992, the German government struck a repatriation deal with Rumania”.. 治 政 大 They used not to be interested themselves for their rights and against abuses and discrimination. 立 Political mobilization. The Roma have organized in a political entity so as to fight. by political matters, leaving it to the gadje. Now, they have understood the necessity to be heard. ‧ 國. 學. at political level, and have started lobbying to influence political decision.. ‧. Fraser reports that “France was the center of the initial attempts to make progress on an international front” (1992: 318). In 1965, the Comité International Tzigane (CIT) „International. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Gypsy Committee‟ was founded in Paris. Their primary aim was not the adaptation of Roma to the host society, but the ending of perceived injustice by the host society.. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. The CIT organized a first World Romany Congress in April 1971 in London. The term Rom. engchi. was adopted to describe themselves, and a flag and a slogan „Opre Roma!‟ (Gypsy rise!) They have now delegates at the UN Human Rights Commission and at the UNESCO, in 1978. They obtained a consultative status at the UN social and Economic Commission in 1979. Fraser underlined that “lobbying of governments and international bodies has been vigorously pursued ever since” (1992: 318).. 28.

(38) In some countries like for instance Hungary, Rumania, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, a large Gypsy population could be found which led them to create their own political parties to represent them. Stereotypes and images. Images on consequent stereotypes have been conveyed to us from early centuries through writers and artists‟ works. Until 1800, those writers, artists and chroniclers were exclusively gadjé. The images they described were full of ignorance and prejudice. Even nowadays, stereotypes are continuously conveyed through news means like the media or the movies. In movies like “Time of the Gypsies” or “Black Cat White Cat” these. 治 政 大 The image repeated and stereotypes are positive, but they remain stereotypes nonetheless. 立 exaggerated was one of a people going from place to place for a long time without a profession,. ‧ 國. 學. asking for alms and stealing, practicing the dark arts and doing other dishonest things (Leblon in. ‧. Kenrick, 2004: 83). The Roma have been misrepresented and marginalized in art. Each depiction in art of Roma criminality and otherness at first glance reflect widespread prejudices and. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. local populations.. sit. antipathy to them (Breger, 2004). This same „otherness‟ is what made them so threatening to the. Ch. i n U. v. Before the nineteenth century, the major stereotype was the darkness of their skin. The color. engchi. of their skin differentiated them from the „normal‟ populations and made them „other‟. From the nineteenth onwards, the Roma were being romanticized. The color black was seen as having exotic connotations. It was associated with a primitive relation to nature, and people saw the Roma as „colorful‟. The noble savage image in vogue at that time attracted the imagination of writers and artists as a lost ideal. They were also seen as exotic, and used as stereotyped Oriental figures in the literature. However, the Romani minority was and is still considered as society‟s underclass with alleged criminal propensities and dealing with the dark arts. The Roma suffered. 29.

(39) from demonization, and this stereotype is far from fading away. In arts and literature there was a ubiquitous emphasis on Roma‟s otherness: because of the physical appearance, because of their attire, and because of their way of living different from that of settled people. Kapralski (2004) argued that these representations can be regarded as part of a political process of introducing repressive legislation to neutralize them. These multiple identities forced onto them century after century conveniently coincided with political attempts to repress and assimilate them. The generation of negative press representations is thus linked to the genesis of. 治 政 大 which involves Rom selfThe Romani identity is actually a process of ethnogenesis 立. political and legislative reaction.. consciously playing with their identities (Acton, 2004). Then we can wonder if the Romani. ‧ 國. 學. identities have been forced onto them by outsiders, or if the Roma themselves have at some point. ‧. played with these identities and adopted them so as to confuse outsiders, with “what is authentic and what is forged”. However, this theoretical discussion about Romani identity seems to be. y. Nat. er. io. sit. more of intellectual Roma‟s concern. Non intellectual Roma do not seem to care about their identity, origins and legitimization of their ethnic belonging. For them, identity is constructed. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. and constantly remade in the present and in relation with significant others (Stewart, 1997).. engchi. V. The Facts, Summer 2010 The fact that triggered the whole movement happened in July 19, 2010, in the village of SaintAignan. During the night, two young men broke through a police roadblock. In what has been later judged as a self-defense move, one of the policemen shot the car and killed one of the young men. These young men happened to belong to a group of Roma who, the next day, attacked the police station to show their anger. The Roma considered the killing not a self-. 30.

數據

+2

相關文件

於高中就學期間,參加政府機關或學術研究機構舉辦與該科相關之國際性或全

吳佳勳 助研究員 國立台灣大學農經博士 葉長城 助研究員 國立政治大學政治學系博士 吳玉瑩 助研究員 國立台灣大學經濟博士 陳逸潔 分析師 國立台灣大學農經系博士生 林長慶

本法中華民國一百零二年六月二十七日修正之條文施行前,因行為不檢有損師道,經有關機

國立政治大學應用數學系 林景隆 教授 國立成功大學數學系 許元春召集人.

本法中華民國一百零二年六月二十七日修正之條文施行前,因行為不檢有損師

旅客消費調查 二零零一年第二季 統計暨普查局

美國自二零零二年第四季經濟明顯放緩,二零零三年第一季經濟增長只錄得 1.9% a 的增

中華人民共和國於 1949 年建立。建國初期,政府提出建設社會主義的目標,推 行不同的政治、經濟和社會的規劃與建設;但在 1966 年至