The Conceptualization of STATE: A Comparative Study of

Metaphors in the R.O.C. (Taiwan) and U.S. Constitutions

*Wen-yu Chiang Sheng-hsiu Chiu

National Taiwan University

This paper uses Critical Metaphor Analysis (Charteris-Black 2004), and Grammatical Metaphor Analysis (Halliday 1985) to analyze the conceptual and grammatical metaphors of STATE appearing in the Constitutions of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and the United States. We demonstrate that metaphors related to STATE in the R.O.C. Constitution mostly represent the state as PROTECTOR, ESTABLISHER and AWARDER, whereas the U.S. Constitution casts the state in the role of POSSESSOR or HOLDER. As for grammatical metaphors, the lexeme state in the R.O.C. Constitution tends to occur as an agent subject in active sentences. In the U.S. Constitution, in contrast, the lexeme state most often occurs in passive sentences, in a role other than that of agent, usually as part of a modifying prepositional phrase. We propose that differences in the types of metaphors used in these two texts reflect differences in the framers’ intent, as well as differences in the two societies’ characterization of the power structure defined by the lexeme state.

Key words: state, conceptual metaphor, grammatical metaphor, R.O.C. Constitution, U.S. Constitution, power, ideology

1. Introduction

Recent linguistic and psychological research suggests that metaphor, far from being merely colorful language, constructs both human organization of experience

and the course of cognitive processing.1 Cognitive linguists (e.g. Lakoff 1987:263)

have demonstrated that our system of conceptual metaphors lies at the very core of our ability to understand and act in the world around us. Lakoff and Turner (1989:227) asserted that “Far from being merely a matter of words, metaphor is a matter of thought – all kinds of thought.” If metaphor wields such power over us, and if we rely upon it as consistently and unconsciously as cognitive linguists suggest, it is highly likely that many metaphors can be found in legal texts. Nevertheless, very few studies have examined the metaphors occurring in legal discourse (e.g. Winter 1988, Ross 1989, Oldfather 1994, and Thornburg 1995). This study investigates the conceptual metaphors used to describe the state2 in the Constitution of the Republic

*

We would like to express our gratitude to Shu-Chuan Chen, Siao-Fong Chung, Ren-feng Duan, Wei-lun Louis Lu, and Tanya Visceglia for their valuable suggestions and discussion. Many thanks also go to the two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on this paper. All remaining errors of commission or omission are our own.

1

See, for example, Lakoff and Johnson (1980:3), Leary (1990:1), and Lakoff (1993:202-203).

2

In the U.S. Constitution, both the term “the United States” and “the Union” refer to the concept of state, that is, the body politic of a nation. For a definition of “state”, see Section 2.2.

of China (Taiwan)3 and that of the United States. It examines the differences in

conceptual metaphors of STATE4 between the two Constitutions and links those

metaphorical differences to differences in political ideology between the two governments. We chose to focus on the term state as it is used in the constitution for two reasons: First, the constitution is more than the law of the land; it is a representation of the collective intentions with which a country is established. It outlines the collective responsibilities and obligations of a country, as well as the individual rights, privileges and obligations of its citizens. The constitution leads both the state and the people in pursuit of their common goals. Thus, the ways in which collective intentions for the role and function of the state are represented in the

metaphors used in connection with the term 國家 guoja ‘state’5 may affect the ways

in which its citizens construct their views of their own government. Second, the notion of ‘statehood’ has long been a focus of study in the social sciences (e.g. Chilton and Lakoff 1995, Coggins 2002, Howes 2003, Neumann, 2004, Wendt 2004, and Lawler 2005), since it is the state that grants and constrains the rights of individual

citizens. By comparing the conceptual metaphors related to state in both

Constitutions, we hope to reveal ideological differences between the two countries in conceptualizing the power structure of the state. In this way, we hope to deepen our understanding of cultural differences inherent in constructing the notion of statehood.

Using Charteris-Black’s (2004) Critical Metaphor Analysis (henceforth CMA)6 to

identify conceptual metaphors surrounding the notion of state, we then evaluate the possible interpretation of those metaphors with respect to ideology.7 8 Our study also incorporates methods used in Corpus Linguistics, in order to compare the occurrence rate of the terms guoja ‘state’ in different contexts between the two Constitution texts.

Furthermore, some patterns found in our data are more directly addressed by

3

Hereafter the Republic of China (Taiwan) will be referred to as R.O.C.

4

Conceptual metaphor is defined as “a cross-domain mapping in the conceptual system” (Lakoff 1993: 203). This cross-domain mapping includes two domains: the source domain and the target domain, which is understood in terms of the source domain. For example, in the metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY, the source domain is journey and the target domain is life; thus, the conceptual structure represented by JOURNEY is mapped onto the domain of life. The concept of speed, originally associated with a journey, can be mapped onto LIFE, which creates expressions such as “I’d better

slow down and think about my future.” In cognitive linguistic conventions, the source and target

domains are written in capital letters. This is to distinguish between metaphor, which is a conceptual cross-domain mapping, and metaphorical expression, which is the instantiation of the metaphor in an utterance. Hereafter, we represent “state” in capital letters when it is referred to as a target domain.

5

For the sake of convenience, hereafter we will omit the Chinese character 國家 and use the romanization guojia only to refer to the lexeme state.

6

For a detailed discussion of CMA, see Section 2.4.1.

7

For a detailed discussion of relationship between language and ideology, see Fairclough (1989, 1995, 2001), Kress (1989, 1990), van Dijk (1991, 1993, 1995, 1998), Fairclough and Wodak (1997), Wodak and Meyer (2001), and Phillips and Marianne (2002).

8

Over the past few years, a growing body of research has analyzed the ideology underlying use of metaphor (Semino and Masci 1996, Stockwell 1999, Koller 2002, 2005, Semino 2002, Medubi 2003, Santa Ana 2003, White and Herrera 2003, Wolf and Polzenhagen 2003, and Rohrer 2004).

Halliday’s Grammatical Metaphor Analysis (Halliday 1985, henceforth GMA). GMA formulates the relationship between metaphors and grammar, which can be used to extend the analysis of conceptual metaphors to the syntax/semantics interface. This gives us a more complete picture of the metaphors found in our Constitution corpora. For example, most of the lexemes guojia in the R.O.C. Constitution were found to occur as agents and as syntactic subjects. In the US Constitution, in contrast, only two of the fifty-nine tokens of the lexeme state occurred as agents.9 10

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background information, theoretical considerations and research method. Several sub-sections then profile it. Sections 2.1 and 2.2 provide background information on the drafting of the two constitutions and their definition of the term state. Previous research on metaphors of STATE and the correlation with our study appear in Section 2.3. Section 2.4 discusses the specifics of our chosen theoretical frameworks: CMA and GMA, and outlines our data collection, classification and analysis procedures. Section 3 discusses the results of the analysis and relates our findings to the underlying political ideologies of the two nations and the text producers (framers), which is afterwards followed by Section 4, the conclusion.

2. Background information, theoretical considerations and research method

2.1 History of the R.O.C. and U.S. Constitutions

The R.O.C. Constitution11 was enacted on December 25, 1946, by the National

Assembly convened in Nanking. It was ratified by the National Government on January 1, 1947 and was put into effect on December 25 of the same year. After the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) retreated to Taiwan, this Constitution was effected in Taiwan. In addition to the preamble, the Constitution comprises 174 articles in 14 chapters. This Constitution intended to embody the ideal of “sovereignty of the people,” to guarantee human rights and freedoms, to provide for a central government with five branches and a local self-government system, to ensure a balanced division of powers between the central and local governments, and to stipulate fundamental national policies.

The Constitution of the United States of America12 was ratified in 1789. The

9

Our analysis of this finding will be presented in Section 3.

10

Consideration of the role of grammar in our analysis was inspired by earlier studies, such as Su (2000), Ahrens (2002), and Chung (2005), which have attempted to incorporate grammar into the CTM framework. Our study departs from previous work, however, in its inclusion of Critical Discourse Analysis.

11

Source: Office of the President, Republic of China.

12

document was the product of nearly 4 months of deliberations at the Federal Convention at Philadelphia. The challenge was to create a republican form of government that could accommodate the 13 states as well as anticipated expansion to the West. The distribution of authority among legislative, executive, and judicial branches was an original attempt to create an effective federal government while preserving the rights of individual states and citizens.

2.2 Definitions of guojia ‘state’ in the two Constitutions

In modern Western political thought, the idea of state is often linked to the notion of an impersonal and privileged legal or constitutional order with the capability of administering and controlling a given territory (e.g. Neumann 1964, Tilly 1975, Poggi 1978, Skinner 1978, and Held and Robertson 1983). Hence, guojia ‘state’ in both Constitutions is defined following this line as “a self-governing political entity, whose responsibility is to organize and guarantee the welfare and security of its citizens within its territory, where it is the supreme authority, tolerating no challenge to its sovereignty” (Mellor 1989:32). Constitutional legal definition of the state competence, as stated explicitly in the first article of the R.O.C. Constitution and the preamble to the U.S. Constitution, lay down its nature and the sources from which its power emanates.

To exercise sovereignty, guojia ‘state’ may be thought to consist of clusters of cobwebs, politically created administrative systems, within the territory of its dominium. Therefore, it is also customary to describe the structure of the state apparatus as the legislature, executive, and judiciary. The role, responsibility, and authorities of such machinery of state as the legislature, executive, judiciary, examination and control in R.O.C. Constitution and the legislature, executive, and judiciary in U.S. Constitution are explicitly prescribed in both texts.

While the terms country and nation are sometimes used interchangeably with

guojia ‘state’, there is a difference among them. A nation is a tightly knit group of

people which share a common culture. By Mellor’s definition, a nation may be described simply as “comprising people sharing the same historical experience, a high level of cultural and linguistic unity, and living in a territory they perceive as their homeland by right” (Mellor 1989:4). In addition, based on Fishman (1972:5), a nation is distinct from a state, polity or country in that the latter may not be independent of external control, whereas a nation is. Sometimes, a single nation may be divided between different states.13 As for the term country, it is a geographical territory in the sense of political geography and international politics. Country is used casually to

13

include both the concept of nation and state. According to Benedict (1991:28), there are dozens of non-sovereign territories which constitute a geographical country, but are not sovereign states.14

2.3 Metaphors of STATE: Previous research

In his discussion of metaphor and war, Lakoff explicated his central metaphor of STATE-AS-PERSON: “A state is conceptualized as a person, engaging in social relations within a world community. Its land-mass is its home. It lives in a neighborhood, and has neighbors, friends and enemies” (1991:3-4). Similarly, Chilton and Lakoff (1995:40), proposed that states are often described as having personalities: “they can be trustworthy or deceitful, aggressive or peace-loving, strong or weak-willed, stable or paranoid, cooperative or intransigent, enterprising or not.”

Many studies suggested that the most common ways to describe the state include a range of fixed metaphorical expressions. (Lakoff 1991, Chilton and Illyin 1993, Chilton and Lakoff 1995, Schaffner 1995, Musolff 1995, Chilton 1996, Milliken 1996, and Wendt 2004). Chilton and Lakoff (1995) and Chilton (1996) argued that most international thinking is embedded in the metaphorically-based belief that STATES are PERSONS or more generally that STATES are CONTAINERS. These metaphors enable us to think about states in terms of their bodies, beliefs and health, or to see states as closed boxes, houses or objects of natural forces. Wendt (2004) also argued that states are perceived as actors or persons; people often attribute to them properties of human beings, such as rationality, identities, interests, and beliefs. Wendt proposed three distinct ways in which states are personified: “STATES are intentional systems”, “STATES are organisms”, and “STATES have consciousness.” The studies summarized above all provide examples of how state is understood as a person-like resource; this metaphor may influence our comprehension of the nature of world politics as well as the ways in which we formulate policy. Our data contain many examples of the STATE-AS-PERSON metaphor in both Constitution texts, such as

guojia appearing in the example (1) of following Section 2.4.1.1, and the United States appearing in example (2) of the same section. We propose that the metaphors in

legal languages differ cross-linguistically both in their frequency and their characterization of the type of person the state should be. A detailed analysis of this finding will appear in Section 3.

14

In some countries (e.g. the U.S.), the term state also refers to nonsovereign political units subject to the authority of the larger State, or federal union. In American constitution law the word state is applied to the several members of the American Union, while the word states/union is applied to the whole body of the people embraced within the jurisdiction of the federal government.

2.4 Theoretical frameworks and research method

2.4.1 Charteris-Black’s Critical Metaphor Analysis

Critical Metaphor Analysis (Charteris-Black 2004), which integrates cognitive linguistics, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) and corpus linguistics, is an approach to metaphor analysis that aims to reveal the covert and possibly unconscious intentions of language users/producers. Cognitive linguistics argues for the potential of metaphor to construct representations of the world; many studies have demonstrated that metaphors are not just pieces of figurative language used to add flavor; instead, metaphors are the conceptual framework for language use, as well as a system for organization of knowledge and experience (e.g. Lakoff and Johnson 1980 inter al.)15.

The CMA model also incorporates Critical Discourse Analysis (Fairclough 1989, 1995, 2001, Kress 1989, 1990, van Dijk 1991, 1993, 1995, 1998, Fairclough and Wodak 1997, Wodak and Meyer 2001, and Phillips and Marianne 2002). According to CDA, language and discourse, far from being self-contained systems removed from interaction and communication, are embedded in social practice and are thus imbued with power and ideology. Speakers, writers, or text producers express their ideologies in the formation of discourse on various linguistic levels; recipients of such discourse interpret it as ideological (van Dijk 1995). According to van Dijk (1995, 1998), the association of discourse and ideology can be seen in a wide range of discourse levels and grammatical structures, including lexicalization, propositional structures, implication and presupposition. The decision of a speaker to use one form of expression instead of another reveals something about his/her ideology. Generation of ideological discourse is claimed to create and perpetuate power imbalances, social hierarchy, dominance and hegemony. CDA proposes that “analysis using appropriate linguistic tools, and referring to relevant historical and social context, can bring ideology, normally hidden through habituation of discourse, to the surface for inspection.” (Fowler 1991:89) CDA aims to increase our awareness of the power imbalances that are forged, maintained and reinforced by language use, with the ultimate goal of correcting those imbalances. We believe that legal discourse is particularly effective in promulgating and maintaining existing hierarchies, so we use CDA to examine the covert ideology in the texts of two Constitutions.

CMA also includes methods used in corpus linguistics. Many earlier studies of metaphor within Lakoff and Johnson’s Cognitive Theory of Metaphor based their

15

Examples include Turner (1987), an analysis of kinship metaphors, and Woodward’s (1991) investigation of education metaphors.

analysis on individual metaphorical expressions, without considering their overall frequency or pattern of distribution. According to Charteris-Black (2004:31), “a corpus is any large collection of texts that arise from natural language use.” Corpus-based analysis allows for analysis of word frequencies and collocations, which may reveal patterns and generalizations of which we would not otherwise be aware.

As for the analysis, we performed the three stages of analysis proposed in Charteris-Black (2004) to identify, interpret and explain the metaphors found in our corpus. However, what differs from the CMA proposed by Charteris-Black is that we incorporate Halliday’s Grammatical Metaphor Analysis in our study. The grammatical metaphor theory was invoked to explain the ways in which the framers’ choice of syntactic category and thematic role also helps to reveal aspects of their ideology.

2.4.1.1 Metaphor identification

Tokens of the lexemes guojia in the R.O.C. Constitution, and the United States or

the Union in the U.S. Constitution were identified and categorized as metaphorical or

non-metaphorical, as exemplified below from (1)16 to (4).

(1) 人民具有工作能力者,國家應予以適當之工作機會。

‘The State shall provide suitable opportunities for work to people who are able to work.’

(2) The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion.

In examples (1) and (2), the lexemes guojia and the United States were identified as metaphorical usages since the presence of incongruity or semantic tension resulting from a shift in domain use of the lexemes was apparent. In these examples, both the impersonal subjects guojia and the United States were personified and followed by a predicate which specified the animate property of the subjects. Other examples such as the near-synonymous lexeme the Republic of China (中華民國) in examples (3) and the United States in example (4) below were determined to be non-metaphorical. In (3), the lexemes the Republic of China ( 中 華 民 國 ) were classified as non-metaphorical because they are used as modifiers for “nationality” and “citizens”, respectively. As in (4), the United States was considered non-metaphorical as well since it functions as the modifier of “the Vice President”.

16

Example (1) and (2) are quoted from Article 152, Chapter 13 of the R.O.C. Constitution and Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution, respectively.

(3) Article 3 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

具中華民國國籍者為中華民國國民。

‘Persons possessing the nationality of the Republic of China shall be citizens of

the Republic of China.’

(4) Article I, Section 3, Paragraph 4 of the U.S. Constitution:

The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no vote, unless they be equally divided.

2.4.1.2 Metaphor interpretation

The second stage of our analysis classified the metaphors we had identified through examination of the contexts in which they occurred. For example, the metaphorical usages of the lexemes guojia and the United States found in (1) and (2) were then classified as conceptual metaphors by considering their collocation with the verb, such as the lexemes the State followed by the verb phrase shall provide in (1) and the United States followed by the verb phrases shall guarantee and shall protect in (2). We found STATE-AS-PERSON to be the most prevalent conceptual metaphor, having a total of 45 metaphorical occurrences in the R.O.C. Constitution and 19 occurrences in the U.S. Constitution.

2.4.1.3 Metaphor explanation

According to Charteris-Black (2004:39), the critical role of metaphor in constructing a covert evaluation can be positive or negative, and the process of metaphor explanation examines the social agency involved in the production of the text as well as the social role of the text in persuasion. The issue of positive or negative evaluation that underlies the choice of one metaphor, however, is not a main concern in this study. Instead, in explaining the conceptual and grammatical metaphors found in the two Constitutions, we intend to identify the discourse function of the metaphors of STATE found in our corpus and to investigate differences in the text producers’ ideological and rhetorical motivations.

2.4.2 Halliday’s Grammatical Metaphor Analysis

Halliday (1985) proposed that the language forms used to represent meaning are networks of choices. A speaker’s selection from the possible words or structures used to express any given meaning is an indicator of that language producer’s ideology. Halliday’s model introduced the concept of grammatical metaphor to analyze possible

motivations underlying the choice of grammatical form in language production. He argued that certain linguistic realizations are “literal” or “congruent” with the grammatical system, and that others are “metaphorical” or “incongruent”. GMA proposes two major categories of grammatical metaphor: metaphors of transitivity and metaphors of mood (including modality). In terms of the model of semantic functions, these could be described as ideational metaphors and interpersonal metaphors, respectively. Ideational metaphors are incongruent with the grammatical system in terms of transitivity. For example, Mary came upon a wonderful sight and a wonderful

sight met Mary’s eyes are both metaphoric variants of Mary saw something wonderful,

but they differ in transitivity congruency.17 Our study analyzed “metaphors of

transitivity”, examining the transitivity of verbs in the sentences containing the lexeme guojia ‘state’ in the two texts.

One example of the grammatical metaphors containing the target lexeme guojia ‘state’ is given in (5).

(5) Article 152 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

人民具有工作能力者,國家應予以適當之工作機會。

‘The State shall provide suitable opportunities for work to people who are able to work.’

In (5), state occurs as an agent in the subject syntactic position. We interpret this choice as reinforcement of the state’s power of agency, since without an agent, the actions of those verbs could not have been performed. Moreover, the syntactic subject position is a major constituent of sentence or clause structure, traditionally associated with the “doer” of an action, which further intensifies the “active” and “dominant” traits of the agent.

In order to examine the transitivity congruence of the sentences in which the target lexeme appears, we further divided the target lexemes into the following syntactic categories since it was found that all the target lexemes occur within these three syntactic classifications.

(a) Subject (the target lexeme is specifically referring to the grammatical subject of an active sentence.)

(b) Object of a preposition18 (the target lexeme is specifically referring to the

grammatical object of a preposition, i.e. the agent, in a passive sentence.)

(c) Modifier (the target lexeme modifies one of the other constituents in the sentence,

17

Only ideational metaphors are discussed in our data analysis; so interpersonal metaphor will not be defined here. For a detailed discussion of interpersonal metaphor, see Halliday (1994).

18

e.g. it appears as the object of a modifying prepositional phrase.)

An additional syntactic structure, negation, was also examined to support our findings that STATE-AS-PERSON metaphors in the R.O.C. Constitution seldom occur in negative sentences, even though negative sentences are very common in legal discourse.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 STATE-AS-PERSON metaphor

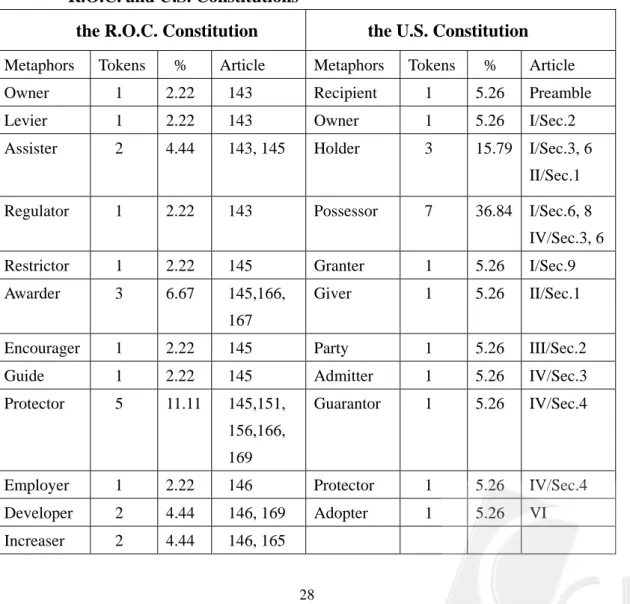

Previous studies of metaphors of STATE showed that states have been endowed with human qualities such as perception, desire and emotion. Metaphors of personhood found in our Constitution corpora have been summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Personification types found in STATE-AS-PERSON metaphors in the R.O.C. and U.S. Constitutions

the R.O.C. Constitution the U.S. Constitution

Metaphors Tokens % Article Metaphors Tokens % Article Owner 1 2.22 143 Recipient 1 5.26 Preamble Levier 1 2.22 143 Owner 1 5.26 I/Sec.2 Assister 2 4.44 143, 145 Holder 3 15.79 I/Sec.3, 6

II/Sec.1

Regulator 1 2.22 143 Possessor 7 36.84 I/Sec.6, 8 IV/Sec.3, 6 Restrictor 1 2.22 145 Granter 1 5.26 I/Sec.9 Awarder 3 6.67 145,166,

167

Giver 1 5.26 II/Sec.1

Encourager 1 2.22 145 Party 1 5.26 III/Sec.2 Guide 1 2.22 145 Admitter 1 5.26 IV/Sec.3 Protector 5 11.11 145,151,

156,166, 169

Guarantor 1 5.26 IV/Sec.4

Employer 1 2.22 146 Protector 1 5.26 IV/Sec.4 Developer 2 4.44 146, 169 Adopter 1 5.26 VI Increaser 2 4.44 146, 165

Improver 1 2.22 146 Planner 1 2.22 146 Initiator 1 2.22 146 Hastener 1 2.22 146 Manager 1 2.22 149 Establisher 3 6.67 150, 155, 157 Fosterer 2 4.44 151, 169 Provider 1 2.22 152 Enactor 1 2.22 153 Enforcer 2 4.44 153, 156 Giver 2 4.44 155, 168 Supervisor 1 2.22 162 Emphasizer 1 2.22 163 Promoter 1 2.22 163 Safe- guardian 1 2.22 165 Subsidizer 1 2.22 167 Accorder 1 2.22 168 Helper 1 2.22 168 Undertaker 1 2.22 169 Total 45 100.00 19 100.00

Differences in the conceptual and grammatical metaphors involving the lexeme

guojia ‘state’ in the two texts can be summarized as follows: STATE-AS-

PROTECTOR, ESTABLISHER and AWARDER occur most frequently and noticeably in the R.O.C. Constitution, while STATE-AS-POSSESSOR and HOLDER appear most often in the U.S. Constitution. Moreover, one striking finding is that instances of all personification types are found in Chapter XIII “Fundamental National Policies” of the R.O.C. Constitution, Articles 143-169. Among the 45 tokens related to guojia, 31 different personification types are found in the R.O.C. Constitution while among the 19 tokens related to state in the U.S. Constitution, there are only 11 various personification types found. When further examining the personification types in the R.O.C. Constitution, we found the most salient type STATE-AS-PROTECTOR appears 5 times in five different articles. STATE-AS-ESTABLISHER and AWARDER each appear three times in three different articles. Tokens which appear two times are STATE-AS-ASSISTER,

DEVELOPER, INCREASER, FOSTERER, ENFORCER and GIVER.19 As for the personification types found in the U.S. Corpus, the most frequent one is STATE-AS-POSSESSOR, which appears 7 times, and, STATE-AS-HOLDER appears three times. Other types such as RECIPIENT, OWNER, GRANTER, GIVER, PARTY, ADMITTER, GUARANTOR, PROTECTOR and ADOPTER each appear one time.

Careful examination of lexeme collocation in the R.O.C. Constitution revealed that the most common words following the target lexemes are verbs such as protect,

establish, award, develop and assist, all of which endow guojia ‘state’ with the ability

to perform human actions. Some typical examples appear below in (6)-(8).

(6) Article 143 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

國家對於土地之分配與整理,應以扶植自耕農及自行使用土地人為原則,並

規定其適當經營之面積。

‘In the distribution and readjustment of land, the State shall in principle assist self-farming land-owners and persons who make use of the land by themselves, and shall also regulate their appropriate areas of operation.’

(7) Article 150 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

國家應普設平民金融機構,以救濟失業。

‘The State shall extensively establish financial institutions for the common people, with a view to relieving unemployment.’

(8) Article 156 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

國家為奠定民族生存發展之基礎,應保護母性,並實施婦女兒童福利政策。

‘The State, in order to consolidate the foundation of national existence and development, shall protect motherhood and carry out a policy for the promoting of the welfare of women and children.’

In the examples above, verbs such as assist, regulate, establish, and protect in the various statutes were interpreted metaphorically to cast the state as the “assister”, “regulator”, “establisher”, and “protector”; these all fall into the category of STATE-AS-PERSON. Similarly, in aforementioned example (2), the United States is categorized as “guarantor” and “protector” based on its collocation with the verbs

guarantee and protect.

In addition to what has been mentioned above, it is also noted that not only the

19

The personification types appearing one time in the R.O.C. Constitution are STATE-AS-OWNER, LEVIER, REGULATOR, RESTRICTOR, ENCOURAGER, GUIDE, EMPLOYER, IMPROVER, PLANNER, INITIATOR, HASTENER, MANAGER, PROVIDER, ENACTOR, SUPERVISOR, EMPHASIZER, PROMOTER, SAFE-GUARDIAN, SUBSIDIZER, ACCORDER, HELPER and UNDERTAKER.

numbers but the role kinds of the personification types are very different between the two Constitution texts. The number of personification types is larger in the R.O.C. Constitution, and also, the role types are, as well, more numerous in the R.O. C. Constitution than those in the U.S Corpora. Moreover, comparing the personification types such as POSSESSOR and HOLDER in the U.S. Constitution, we found that the various role kinds such as PROTECTOR, AWARDER, ESTABLISHER, ASSISTER etc. in the R.O.C. Constitution are more energetic, active, and with greater power. The differences of both the quantity and quality of the personification types related to

guojia ‘state’ in the two texts indicate the very different nature of the R.O.C. and U.S.

Constitution.

3.2 Grammatical metaphors

As for grammatical metaphors, 45 metaphorical occurrences of guojia ‘state’ were found in the R.O.C. Constitution, and 59 were found in the U.S. Constitution. It is interesting to note that all the metaphorical occurrences of guojia in the R.O.C. Constitution belong to both conceptual and grammatical metaphors, while only 19 out of 59 in the U.S. Constitution are both conceptual and grammatical metaphors.

Examples from our corpora to illustrate the target lexeme appearing as a grammatical subject of an active sentence are below in (9) and (10).

(9) Article 146 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

國家應運用科學技術,以興修水利,增進地力,改善農業環境,規劃土地利

用,開發農業資源,促成農業之工業化。

‘The State shall, by the use of scientific techniques, develop water conservancy,

increase the productivity of land, improve agricultural conditions, develop

agricultural resources and hasten the industrialization of agriculture.’ (10)Section 4 of Article IV of the U.S. Constitution:

The United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form

of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion; and on application of the legislature, or of the executive (when the legislature cannot be convened) against domestic violence.

In these two examples, the target lexemes not only are in subject syntactic positions but also belong to the classification of conceptual metaphor. We identified the target lexemes as PERSON since they are followed by specific related verbs such as develop and guarantee, which give a personal acting part to the subjects.

3.2.1 Transitivity

Among 45 occurrences of the lexeme guojia found in the R.O.C. Constitution, 23 tokens were semantic agents; of these, 6 tokens were objects of a preposition of passive sentences and 17 tokens were syntactic subjects of active sentences collocated with verbs. In the U.S. corpus, among 59 occurrences of the lexeme state in the U.S. Constitution, only two tokens are semantic agents. Examples to illustrate the target lexeme referring to the syntactic subject of an active sentence are represented above in (9) and (10), while examples to specify target lexemes referring to semantic agents in passive sentences are shown below in (11) and (12).

(11) Article 149 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

金融機構,應依法受國家之管理。

‘Financial institutions shall, in accordance with law, be subject to State control.’ (12) Article I, Section 9 of the U.S. Constitution:

No title of nobility shall be granted by the United States: and no person holding any office of profit or trust under them, shall, without the consent of the Congress, accept of any present, emolument, office, or title, of any kind whatever, from any king, prince or foreign state.

Both (11) and (12) are passive constructions, and in each, the target lexeme state occurs as a part of a prepositional phrase, namely, the grammatical object of the preposition to and by. Specifically, the target lexeme, either State in (11) or the United

States in (12), is semantically related to the verbs control and grant, and is the one

who performs the action.

The categorization of grammatical metaphors related to STATE with respect to thematic agency and voice (active vs. passive) has been summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Grammatical metaphors of STATE classified with respect to agency and voice

the R.O.C. Constitution

Metaphors Tokens %

Agent 23 Active 17 51.11 Active 73.91

Passive 6 Passive 26.09

Non-agent 22 48.89

the U.S. Constitution Metaphors Tokens % Agent 2 Active 1 3.39 Active 50.00 Passive 1 Passive 50.00 Non-agent 57 96.61 Total 59 100.00

Some occurrences of the target lexeme in both Constitution texts are non-agent, and appear as the objects of prepositions to modify one of the other constituents in the sentences. Example (13) and (14) below are the typical ones in our corpora.

(13) Article 53 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

行政院為國家最高行政機關。

‘The Executive Yuan shall be the highest administrative organ of the State.’ (14) Article I, Section 6 of the U.S. Constitution:

The Senators and Representatives shall receive a compensation for their services, to be ascertained by law, and paid out of the treasury of the United States. They shall in all cases, except treason, felony and breach of the peace, be privileged from arrest during their attendance at the session of their respective Houses, and in going to and returning from the same; and for any speech or debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other place.

In (13), the target lexeme state occurs as the object of the prepositional phrase of

the State to modify the NP (noun phrase) the highest administrative in the sentence.

Similarly, the United States in (14) appears as the object of the preposition of in the phrase of the United States to describe and limit the meaning of the NP the treasury in the sentence.

When focusing on the findings of the U.S. Constitution, we found that fifty-five occurrences of the lexeme state are not assigned the role of agent; these were also categorized on the basis of the prepositions with which they co-occur, as shown in Table 3.20

20

Aside from the 55 modifiers listed in Table 3, two other instances of grammatical metaphor were found among the 57 non-agent tokens. In the preamble, the lexeme union appears as the object of the infinitive; the other is in Section 2 of Article III, in which the United States is the subject of an adjective clause.

Table 3. Grammatical metaphors of STATE occurring as modifiers within prepositional phrases in the U.S. Constitution

the U.S. Constitution

Type Token %

of the United States of the union

36 69.09

2

for the United States 1 1.82

within the United States within this union

1 3.64

1

under the United States 4 7.27

throughout the United States 3 5.45

From the United States 1 1.82

Against the United States 3 5.45

to the United States 1 1.82

into this union 1 1.82

in this union 1 1.82

Total 55 100.00

Using Halliday’s model, the instances of “a Congress of the United States” would be interpreted as a relational process of possession, and “profit under the United States” as a relational process of circumstance. In the first type, the relationship between the two terms is one of ownership; one entity possesses another. In the second type, the attribute is a prepositional phrase and circumstantial relationship is expressed using a preposition, e.g. about, in, with or under.

The results presented above show that most of the state lexemes found in Chapter XIII “Fundamental National Policies” of the R.O.C. Constitution occur in the subject syntactic position and play the thematic role of agent in active sentences, whereas the lexeme state usually occurs in the U.S. Constitution as non-agent in passive sentences, most often in the object syntactic position of a prepositional phrase, acting as a modifier (e.g. under the United States, of the Union). We propose that the different syntactic configurations of the grammatical metaphors between the two Constitutions can be linked to differences in the power structures underlying the two texts. In the R.O.C. Constitution, state is represented as being more like a powerful social actor (agent) who can perpetuate and exercise dominance. In contrast, the social power of the state in the U.S. Constitution tends to be downplayed or left implicit by using various types of non-agentive representation. However, apart from the tokens found in Chapter XIII of the R.O.C. Constitution, most of the syntactic structures used in both texts are passive constructions. Examples (15) and (16) illustrate uses of the passive

typically found in legal discourse.

(15) Article 8 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

人民身體之自由應予保障。除現行犯之逮捕由法律另定外,非經司法或警察

機關依法定程序,不得逮捕拘禁。非由法院依法定程序,不得審問處罰。非

依法定程序之逮捕、拘禁、審問、處罰,得拒絕之。

‘Personal freedom shall be guaranteed to the people. Except in case of flagrante delicto as provided by law, no person shall be arrested or detained otherwise than by a judicial or a police organ in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law. No person shall be tried or punished otherwise than by a law court in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law. Any arrest, detention, trial, or punishment which is not in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law may be resisted.’

(16) Article I., Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution:

All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

The construction of (15) in the R.O.C. corpus is in the passive voice, with the semantic agent State omitted. In a similar way, although the target lexeme the United

States in (16) is non-agent and a modifier of the noun Congress, the syntactic

construction of the sentence is obviously passive voice.

3.2.2 Negation

Both Constitutions contain a large proportion of negative sentences, due to the tendency in legal documents to use an unusual amount of negation. The profession’s favoring of the negative may be related to the age-old notion that the law is primarily about what people cannot do; thus, it is most logically phrased in the negative. Negatives include not only words like not or never, but any element with negative meaning, like the prefix mis- in misstate or un- in unusual, and even semantic negatives21 like the words deny, forbid, except, free from and unless. Two typical negative constructions of each of the Constitutions are offered in examples (17) and (18) below.22

21

Also termed “hidden negatives”.

22

One issue worthy of mention is that the syntactic constructions stating provisions of Article I, Section 9 of the U.S. Constitution are all negative sentences. In this case, it is reasonable to assume that subject matter dictates grammatical choice; these provisions all specify restrictions on the powers of Congress. For example, Paragraph 3 provides “No bill of attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed.” Paragraph 4 provides “No capitation, or other direct, tax shall be laid, unless in proportion to the census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.” Paragraph 5 provides

(17) Article 4 of the R.O.C. Constitution:

中華民國領土,依其固有之疆域,非經國民大會之決議,不得變更之。

‘The territory of the Republic of China according to its existing national boundaries shall not be altered except by resolution of the National Assembly.’ (18) Article I, Section 5 of the U.S. Constitution

Neither House, during the session of Congress, shall, without the consent of the

other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other place than that in which the two Houses shall be sitting.

Two negative indicators, not and except appear in (17) to signify the negative construction of the statute, while in the U.S. example, similarly, two negative conjunctions neither and nor indicate the negative construction of (18).

Although negation is pervasive in our corpora, the sentences containing the lexeme guojia in the R.O.C. Constitution are all positive. Regarding the power of state, one exception exemplified below in (19) is Article 23.

(19) Article 23 of the R.O. C. Constitution:

以上各條列舉之自由權利,除為防止妨礙他人自由、避免緊急危難、維持社

會秩序,或增進公共利益所必要者外,不得以法律限制之。

‘All the freedoms and rights enumerated in the preceding Articles shall not be

restricted by means of law except such as may be necessary to prevent

infringement upon the freedoms of other persons, to avert an imminent crisis, to maintain social order or to advance public welfare.’

It is crucial to note that even this statute laying down the authority of state is in negative syntactic construction, the subject guojia is actually omitted and downgraded. As for the U.S. corpora, of the two tokens with state as semantic agents, one is negative, and the other is positive. Each of them is represented in (20) and (21) respectively.

(20) Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution:

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person

holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince or foreign State.

(21) Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution:

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican

Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

Negative passive construction (20) takes the target lexeme the United States as the agent while in (21), the United States is the grammatical subject and specifies the agent function in an active construction.

Comparing the difference of negative construction related to guojia ‘state’ in both Constitution texts, we found there are more positive sentences containing the lexeme

guojia in the R.O.C. Constitution. This supports our position that STATE in the

R.O.C. Constitution has been endowed with more power and is subject to fewer constraints.

3.2.3 Further examples

With the exception of the STATE metaphor found in Chapter XIII of the R.O.C. Constitution, the two constitutions’ provisions for subordination of the president, congress, and other government organizations to the state are very similar in terms of syntactic construction and semantic role. For example, provisions regarding the

executive powers of the president in both Constitutions23 have the same syntactic

structure. This is also true for provisions regarding administration and legislation. For instance, Articles 57, 59 and 60 of the ROC Constitution correspond to Article II, Section 3 of the US Constitution; the provisions outlined in Article 64 of the R.O.C. Constitution correspond to those in Article I, Sec.2-3 of the U.S. Constitution. These parallels provide further support for our previous claim that different conceptualizations of STATE-AS-PERSON represent the major source of difference between the two Constitutions, since other institutions granted power by the Constitution are represented in more linguistically similar ways. To make this clearer, some examples are given below. For example, both Article 64 of the R.O.C. Constitution and Article I, Section 2 and 3 of the U.S. Constitution are the provisions pertaining to the power of the legislative.

(22) Article 64 of the R.O.C. Constitution: 立法院立法委員,依左列規定選出…

23

‘Members of the Legislative Yuan shall be elected in accordance with the following provisions...’

(23) Article I, Section 2 and 3 of the U.S. Constitution

The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, chosen by the Legislature thereof, for six Years; and each Senator shall have one Vote.

The syntactic constructions of these two provisions are both passive. Moreover, legislators and congressmen such as representatives and senators are similarly the syntactic subjects with the semantic roles of patient in both Constitution texts.

3.3 Ideology related to both conceptual and grammatical metaphors in the two Constitutions

We suggest that differences in construction of conceptual and grammatical metaphor between the two Constitutions reflect underlying ideological differences in the framers’ intentions. Co-occurrence of STATE-AS-PROTECTOR conceptual metaphors and STATE as agent grammatical metaphors is the characteristic of the dominant role of the state in the R.O.C. Constitution. The U.S. Constitution, in contrast, exhibits an abundance of non-agent roles and fewer STATE-AS- PROTECTOR conceptual metaphors, which suggests an emphasis on distribution of powers and a desire to mitigate the importance of centralized government.

We believe that the different choices of metaphor in both of the Constitutions also reveal the distinct institutional principles and philosophies of the text producers. The R.O.C. Constitution was developed based on the philosophy of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founding father of the R.O.C., particularly based on his “Three Principles of the

People”24 and “The Separation of Five Powers.”25 26 Sun also formulated the

principles of nationalism, democracy, and social well-being. The Principle of

24

The first article of the Constitution explicitly states that “The Republic of China, founded on the Three Principles of the People, shall be a democratic republic of the people, to be governed by the people and for the people.”

25 行政、立法、司法、考試、監察,五權分立;亦稱五權憲法.

26

The separation of three powers: executive, legislative and judiciary, was modeled on the “Separation of Powers” doctrine, originally proposed by the French political thinker Montesquieu. The divisions of Examination and Control, in contrast, were developed by Sun according to traditional Chinese principles of government.

Nationalism27 calls for equal treatment and sovereign status for the R.O.C. internationally as well as equality for all ethnic groups within the nation. The Principle of Democracy,28 which grants each citizen the right to exercise political and civil liberties, is the foundation for the organization of the R.O.C. government. The Principle of Social Well-being29 dictates that powers granted to the government must ultimately serve the welfare of the people by building a prosperous economy and a just society. Since the “The Principle of Social Well-being” was emphasized strongly by Sun, it has made a significant contribution to the content of Chapter XIII of the R.O.C. Constitution. The provisions of Chapter XIII mainly enumerate the state’s duties and obligations, such as education, land reform and social welfare; these are intended to enact Sun’s “Principle of Social Well-being.” The Constitution emphasizes that the state should carry out its duties and obligations, and implement national policies for the benefit of the people. To fulfill these objectives, the role of the state is quite active; it must prevent restrictions against the freedom of others, respond to emergencies, maintain social order, and protect the public interest. We found that the dominant position assigned to the state is reflected in the large percentage of state lexemes occurring as agent subjects, and in the large variety of conceptual STATE metaphors casting the state in the role of PROTECTOR, ESTABLISHER and AWARDER.

The U.S. Constitution was also shaped by the political doctrine of “Separation of Powers”, under which the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government are kept distinct to prevent abuse of power. We believe that, although the Montesquieu doctrine is never explicitly referred to, its importance is clearly implied by the provisions of the Constitution. In Article I, “all legislative powers” are “vested in a Congress of the United States”. In Article II, “the executive power” is “vested in the President of the United States”, and in Article III, “the judicial power” is “vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time ordain and establish”. In addition, in order to prevent the concentration and abuse of power, a

system of “checks and balances”30 was established to constrain the powers of the

three branches of government. Since the U.S. Constitution emphasizes the even distribution and limitation of state power, rather than investment of power in the state for the protection of the people, we would expect to find far fewer instances of the

27 民族主義.

28 民權主義.

29 民生主義.

30 制衡原則 (checks and balances) is a phrase coined by Montesquieu. In a system of government

with competing sovereigns (such as a multi-branch government or a federal system), “checks” refers to the ability, right, and responsibility of each power to monitor the activities of the other(s); “balances” refers to the ability of each entity to use its authority to limit the powers of the others, whether in general scope or in particular cases.

state being cast in the role of agent, acting on the people’s behalf. Moreover, this is compatible with our analysis of metaphorical state lexemes in the U.S. Constitution presented in Section 3.1 and 3.2—the state has fewer personification types, and it mainly occurs in non-agentive, prepositional phrases in post-nominal, modifier positions.

4. Conclusion

Our investigation of both the conceptual and grammatical metaphors of the two Constitution texts makes some contributions with regard to cognitive and social science. We would like to summarize them as follows.

Firstly, our study gives a new insight into the ways of viewing the legal language. Traditionally, the precision of the language of law is the overwhelming claim since the legal professions are acutely aware that any ambiguity in a legal document can lead the law down the garden path. Lots of researchers also argue that legal language is by its nature more precise than ordinary language (e.g. Mellinkoff 1963, and Solan 1993). However, after thorough analysis, we found that metaphors, without exception, have the same impact in the legal world. The personification metaphor, as when the physical object is conceived as having human qualities or powers, is particularly easy to be neglected in legal texts. In Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson (1980:34) argued that “Personification is a general category that covers a very wide range of metaphors”. They proposed that personification metaphors are “extensions of ontological metaphors and that they allow us to make sense of phenomena in the world in human terms”. Since viewing something abstract in human terms functions actively and importantly in our cognition, we should pay more attention to this matter in legal texts too. Based on the comparison of two Constitution texts, we found that the lexemes guojia ‘state’ in both corpora are conceived as having abundant and multiple personification characteristics. This finding is tremendously different from those of previous studies. Most previous studies (e.g. Chilton 1996, Neumann 2004, Wendt 2004, and Lawler 2005) showed that the personification type of STATE metaphor tends to be more monotonous and lack variety while this study demonstrates the state cast in multiple roles.

Secondly, our approach to the data integrates principles of Critical Metaphor Analysis and Grammatical Metaphor Analysis to better capture the ideological generalizations underlying the state-related metaphors used in the two Constitutions. With the integrated models, most of the lexemes guojia in the R.O.C. Constitution were found to occur as agents with multiple personification roles. In the U.S. Constitution, in contrast, nearly all the state lexemes occur as post-modifiers within

prepositional phrases and with fewer personification roles. Our study has shown that using an integrated approach to examine both the conceptual and grammatical metaphors not only gives us a more comprehensive picture of the findings but also throws new light on the issue of metaphor analysis.

Thirdly, this study has demonstrated that metaphor analysis can be very useful in revealing the ideology hidden behind linguistic expressions. Our investigation of both the conceptual and grammatical metaphors of the two Constitution texts has shown that metaphor choices are, in part, motivated by ideology, particularly by the ideology of the text producers. According to Charteris-Black (2004), “if language is a prime means of gaining control of people, metaphor is a prime means by which people can regain control of language.” Therefore, we suggest that the increased awareness of metaphor through critical analysis is necessary for individual empowerment and offers alternative ways to understand the world we live in.

Since metaphor is a vital language device that reflects the cognitive source of human thinking, we expect that more and more studies will explore the interrelationship of ideology and metaphor in legal languages. Our future research will examine a range of legal texts to investigate whether patterns can be found that are similar to those presented here. We believe that continuing analysis of the metaphors in legal texts will slowly reveal text producers’ intentions, as well as the ways in which those texts have influenced popular perception of the power relations associated with the concept of state.

References

Aarts, Bas. 2001. English Syntax and Argumentation. 2nd edition. New York: Palgrave

Publishers.

Ahrens, Kathleen. 2002. When love is not digested: Underlying reasons for source totarget domain pairings in the contemporary theory of metaphor. Proceedings of

the First Cognitive Linguistics Conference, ed. by Yuchau E. Hsiao, 273-302.

Taipei: National Chengchi University.

Benedict, Anderson. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread on Nationalism. London: Verso.

Charteris-Black, Jonathan. 2004. Corpus Approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis. New York: Palgrave-MacMillan.

Chilton, Paul, and Mikhail Illyin. 1993. Metaphor in political discourse: The case of the ‘common European house’. Discourse and Society 4:7-31.

Peace, ed. by Christina Schaffner, and Anita L. Wenden, 37-59. Singapore:

Harwood Academic Publishers.

Chilton, Paul. 1996. The meaning of security. Post-Realism: The Rhetorical Turn in

International Relations, ed. by Francis A. Beer, and Robert Harriman, 193-216.

East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Chung, Siaw-Fong. 2005. MARKET metaphors: Chinese, English and Malay.

Proceedings of the 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (PACLIC19), 77-81. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Coggins, Bridget. 2002. Secession, Recognition and the International Politics of

Statehood. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University.

Fairclough, Norman. 1989. Language and Power. New York: Longman Group.

Fairclough, Norman. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of

Language. London: Longman.

Fairclough, Norman, and R. Wodak. 1997. Critical discourse analysis. Discourse as

Social Interaction, ed. by T. A. van Dijk, 258-284. London: Sage Publications.

Fairclough, Norman. 2001. Language and Power. 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

Fishman, Joshua. 1972. Language and Nationalism: Two Integrative Essays. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Fowler, R. 1991. Language in the News: Discourse and Ideology in the Press. London: Routledge.

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1985. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1994. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 2nd edition.

London: Edward Arnold.

Held, David, and Martin Robertson. (eds.). 1983. States and Societies. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Howes, Dustin Ells. 2003. When states choose to die: Reassessing assumptions about what states want. International Studies Quarterly 47:669-692.

Koller, V. 2002. A shotgun wedding: Co-occurrence of war and marriage metaphors in mergers and acquisitions discourse. Metaphor and Symbol 17:179-203.

Koller, V. 2005. Critical discourse analysis and social cognition: Evidence from business media discourse. Discourse and Society 16:224-299.

Kress, G. 1989. History and language: Towards a social account of linguistic change.

Journal of Pragmatics 13:445-466.

Kress, G. 1990. Critical discourse analysis. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 11:84-97.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal

about the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Turner. 1989. More Than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to

Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George. 1991. Metaphor and war: The metaphor system used to justify war in the Gulf. Peace Research 23:25-32. London: Sage publications.

Lakoff, George. 1993. The contemporary theory of metaphor. Metaphor and Thought, ed. by Andrew Ortony, 202-251. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lawler, Peter. 2005. The good state: In praise of ‘classical’ internationalism. Review

of International Studies 31:427-449.

Leary, David E. 1990. Psyche’s muse: The role of metaphor in the history of psychology. Metaphors in the History of Psychology, ed. by David E. Leary, 1-23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Medubi, O. 2003. Language and ideology in Nigerian cartoons. Cognitive Models in

Language and Thought: Ideology, Metaphors and Meanings, ed. by Rene Dirven,

Roslyn Frank, and Martin Putz, 159-198. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mellinkoff, David. 1963. Language of the Law. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. Mellor, Roy E. H. 1989. Nation, State, and Territory. New York: Routledge.

Milliken, Jennifer L. 1996. Metaphors of prestige and reputation in American foreign policy and American realism. Post-Realism: The Rhetorical Turn in International

Relations, ed. by Francis A. Beer, and Robert Harriman, 217-238. East Lansing:

Michigan State University Press.

Musolff, Andreas. 1995. Promising to end a war = Language of peace? The rhetoric of allied news management in the Gulf War 1991. Language and Peace, ed. by Christina Schaffner, and Anita L. Wenden, 93-110. Aldershot: Dartmouth.

Neumann, Franz. 1964. The Democratic and the Authoritarian State. New York: Free Press.

Neumann, Iver B. 2004. Beware of organicism: The narrative self of the state. Review

of International Studies 30:259-267.

Oldfather, Chad M. 1994. The hidden ball: A substantive critique of baseball metaphors in judicial opinions. Connecticut Law Review 17:27-68.

Ortony, Andrew. 1993. Metaphor and Thought. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Phillips, L., and W. J. Marianne. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage Publications.

Poggi, Gianfranco. 1978. The Development of the Modern State. London: Hutchinson. Rohrer, T. 2004. Cartooning and ideology: A conceptual blending analysis of contemporary and WWII war cartoons. Ideology zwischen Luge und

Wahrheitsanspruch, ed. by Steffen Greschonig, and Christine S Sing, 193-216.

Wiesbaden, Germany: Deutscher Universitats-Verlag.

Ross, Thomas. 1989. Metaphor and paradox. Georgetown Law Review 23:1053. Santa Ana, O. 2003. Three mandates for anti-minority policy expressed in U.S. public

discourse metaphors. Cognitive Models in Language and Thought: Ideology,

Metaphors and Meanings, ed. by Rene Dirven, Roslyn Frank, and Martin Putz,

199-228. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Schaffner, Christina. 1995. The ‘balance’ metaphor in relation to peace. Language

and Peace, ed. by Christina Schaffner, and Anita L. Wenden, 75-92. Aldershot:

Dartmouth.

Semino, E., and M. Masci. 1996. Politics is football: Metaphor in the discourse of Silvio Berlusconi in Italy. Discourse and Society 7:243-269.

Semino, E. 2002. A sturdy baby or a derailing train? Metaphorical Representations of the Euro in British and Italian Newspapers. Text 22:107-139.

Skinner, Quentin. 1978. The Foundations of Modern Political Thought. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Solan, Lawrence M. 1993. The Language of Judges. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stockwell, P. 1999. Towards a critical cognitive linguistics. Discourses of War and

Conflict, ed. by A. Combrink, and I. Biermann, 510-528. Potchefstroom, South

Africa: Potchefstroom University Press.

Su, I-Wen Lily. 2000. Mapping in thought and language as evidenced in Chinese.

Chinese Studies 18:395-421.

Thornburg, Elizabeth G. 1995. Metaphors matter: How images of battle, sports, and sex shape the adversary system. Wisconsin Women’s Law Journal 10:225-282.

Tilly, Charles. 1975. Reflections on the history of European state-making, The

Formation of National States in Western Europe, ed. by C. Tilly, 3-83. New

Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Turner, Mark. 1987. Death is the Mother of Beauty: Mind, Metaphor, Criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

van Dijk, T. A. 1991. Racism and the Press. London: Routledge.

van Dijk, T. A. 1993. Discourse and Elite Racism. London: Sage Publications.

van Dijk, T. A. 1995. Discourse semantics and ideology. Discourse and Society 6: 243-289.

van Dijk, T. A. 1998. Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. London: Sage Publications.

Wendt, Alexander. 2004. The state as person in international theory. Review of

White, M., and H. Herrera. 2003. Metaphor and ideology in the press coverage of telecom corporate consolidations. Cognitive Models in Language and Thought:

Ideology, Metaphors and Meanings, ed. by Rene Dirven, Roslyn Frank, and

Martin Putz, 277-323. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Winter, Steven L. 1988. The metaphor of standing and the problem of self-governance. Stanford Law Review 40:1371-1387.

Wodak, R., and M. Meyer M. (eds.). 2001. Methods of Discourse Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Wolf, Hans-Georg, and Frank Polzenhagen. 2003. Conceptual metaphor as ideological stylistic means: An exemplary analysis. Cognitive Models in

Language and Thought: Ideology, Metaphors and Meanings, ed. by Rene Dirven,

Roslyn Frank, and Martin Putz, 247-276. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Woodward, Tessa. 1991. Models and Metaphors in Language Teacher Training. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[Received 22 August 2006; revised 14 January 2007; accepted 29 January 2007]

Wen-yu Chiang

Graduate Institute of Linguistics &

Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University

Taipei, TAIWAN wychiang@ntu.edu.tw Sheng-hsiu Chiu

Graduate Institute of Linguistics National Taiwan University Taipei, TAIWAN