Constitution-Making and the Search for

a European Public Sphere

by

Chien-Yi Lu chienyilu@yahoo.com.tw Associate Research Fellow Institute of International Relations

National Chengchi University Taipei, Taiwan

Paper prepared for the First Annual Research Conference of the EU Centre of Excellence (EUCE)—The Constitutional Treaty, May 21-23, 2007, Halifax

Abstract

How can we reconcile the transparent and inclusive Constitution-making process with the rejection of the Constitutional Treaty? I argue that even though the communicative channels were opened to encourage participation, they were not utilized because of the absence a European public sphere (EPS). Stressing that the concept of public sphere only became relevant owing to the functions it performs to make democracy possible, I demonstrate that an EPS never emerged to allow the Europe-wide public use of reason. The findings of this article, namely that the absence of the EPS deprived citizens of the right to meaningfully participate in the Constitution-making process, have far-reaching implications for the future of the Union. The ratification of the Treaty will not be the last challenge of its kind. Unless the importance of the EPS is taken seriously, the perpetuating elite-citizen gap will result in the same mistake to be repeated time and again.

Introduction

In spite of opinion polls indicating the likely rejection of the Constitutional Treaty (CT) by the French and Dutch voters, the panic and disbelief among the

European political elites following the referendum revealed that the elites were utterly unprepared for the negative results. ‘What’s wrong with them (meaning the ‘no’ voters)?’seemed to be the common question beleaguering their thoughts (Blair 2006). What was wrong, for the elites, was that the voters failed to understand the CT. Had they understood it, the results would have been different.1The political elites were not the only ones stunned by the results. The press described the French referendum as‘a masterpiece of masochism’(Liberation) that ‘turned everything upside down’(Le

Figaro). De Telegraaf noted that even though the Dutch ‘nee’was much expected,

particularly following the French ‘non,’‘nobody foresaw the vote against to be so massive.’Even veteran scholars of European integration were betting, at the eve of the referendum, on a ‘petit oui’(Ross 2005).

There were, however, good reasons to believe that voters would approve the Constitutional Treaty. Among other things, narrowing the elite-citizen gap, fighting the problem of popular disengagement, and enhancing the democratic legitimacy of the European Union (EU) were what instigated the decision to create a Constitution in the first place. The fact that the Convention was unprecedented in its openness and inclusivity also enhanced the expectation that the European citizens, seeing the drafting of the Constitution unfolding in front of them and with the opportunity to

participate, would find the Constitution at least acceptable.

How can we reconcile the discrepancy between the transparent and inclusive Constitution-making process on the one hand and the rejection of the CT by the voters on the other? I argue that even though the communicative channels were opened to encourage the participation of citizens, they were hardly utilized because a European public sphere (EPS) was not present to sustain effective information flow and

meaningful debate among citizens and between elites and citizens.

Contradiction: Transparency, Inclusivity, and Rejection

The origin of the Convention depicts the degree to which the European elites had been troubled by the problem of democratic deficit. In his Humboldt University speech in May 2000, Joschka Fischer expressed his concerns that the process of European integration had been viewed as an undemocratic project, run by a faceless, soulless Eurocracy in Brussels. To tackle the problem, Fischer proposed the launching of a debate on the constitution of the EU. The speech was widely reported and

commented upon by newspapers in the Member States and spurred a series of responses from European political leaders. While views expressed ranged from federalism to intergovernmentalism, all agreed that making the people’s voice heard was the top priority. As a result, the ‘Declaration on the Future of the Union’attached to the Treaty of Nice formally called for ‘a deeper and wider debate about the future of the European Union,’with participation from all interested parties. At Laeken in December 2001, the leaders agreed on the Convention method as the way to produce the final product of the debate.

Given that the common concern of getting closer to the citizens brought the Constitutional Convention into being, it was unsurprising that in designing the

drafting procedure the elites endeavored to make all communicative channels open to the public. In order to ensure broad participation and transparency, an online Forum was created. To reach non-internet-users, the Convention organizers wrote to the editors of all the major newspapers to encourage the media to launch debates of their own on the future of Europe (CONV 14/02:6). Lest the exercise of listening to the citizens became mere rhetoric, the Convention devoted four months —the ‘listening phase’—to identifying people’s expectations and needs from the EU. In the course of the Convention, with the exception of activities within the Presidium, all the

Convention members were made available on the Convention website. In addition, a list of all Convention members with their contact details was available on the website for public use. Citizens could also attend the plenary sessions by contacting the

visitors service of the European Parliament (CONV 9/02). A Conventionnel noted that, ‘up until now, there had been no such public debate with such readily available public information about the major reform in the EU.’2

As a deliberative body, voting was ruled out as a way to determine the consensus among the Conventionnels. Hence, while intergovernmental negotiation was

unsurprisingly still a persisting element in the process, remarkably, the Convention saw representatives of Member States and EU institutions, ranging from federalists to euro-skeptics, leftists to conservatives, ‘deliberated on all issues related to the EU, examined all possible reforms, expressed in public the largest spectrum of arguments ever made about the EU’in the course of the Convention (Magnette 2003:2). Owing to its composition, transparency, and deliberative style, many came to believe that the Convention had ‘proved its worth’and achieved more than an IGC would ever have (Closa 2004:204; Eriksen and Fossum 2004; Maurer 2003; Magnette 2004; Interview with Conventionnels 2004). Those who criticized the EU because it had been built behind closed doors had, as a result of the Convention, ‘lost their argument’ (Magnette 2003:2).

In making sense of the no vote in the aftermath of the referenda, public discourse and opinion polls pointed to factors such as unemployment, fear of globalization and Eastern enlargement. These factors cannot, however, answer why citizens still voted ‘no’when all communicative channels were made open to make them the co-author of the document. Given the impressive efforts to engage the citizens, concerns over unemployment, globalization, and Eastern enlargement should have been addressed

during, not after the drafting process; why weren’t they? It is easy to criticize the

Constitution as yet another product of elitism; as Blair had put it, ‘we locked ourselves in a room at the top of the tower and debated things no ordinary citizen could understand’(Blair 2006). Yet this is to forget that a European-wide debate on the future of Europe was launched a year before the Convention. During that period and at the inception of the Convention, the political elites did put out flags and wave at the people, trying to catch their attention. Why was the connection not made? It is true that all constitutions are written by elites. It is also true that in national contexts, voters regularly say ‘no’to their political elites through referenda. The difference with the CT, however, is that it was explicitly about the problem of popular disengagement and ways to change it. In fact, contrary to the intention of narrowing the elite-citizen

gap through Constitution-making, the process only revealed and magnified how deep and wide the gap is.

The key problem, I argue, is the absence of an EPS. Without an EPS to sustain meaningful cross-level and transnational communications, the so-called

‘European-wide debates’and ‘dialogues’were launched in a vacuum. Hence, when the ‘Europeanized’elites came up with transnationalized solutions, the European voters, confined in the public spheres they resided in, could only test those solutions against ‘national’experiences and ‘national’visions; they found, unsurprisingly, the solutions unacceptable. By the same token, the inability of the elites to discern the will of the people during the drafting process is also just a natural result of the absence of an EPS. The absence of an EPS perpetuates the discrepancy and the conflicts between the ‘Europeanized top’and the ‘un-Europeanized bottom,’as was epitomized in the Constitution-making experience.

Functions of the Public Sphere

The public sphere (PS) is a realm of our social life that hosts myriads of public forums, links small, private circles of discussion into larger, public conversations. Woven by a variety of media—print, electronic, and face-to-face encounters—it occupies the space between the scattered, ill-informed, and poorly developed private opinions on the one hand, and the approximated public opinion on the other. By synthesizing streams of communication and sustaining the public competition of private arguments, the PS helps to channel relevant societal problems into topics of concern that would allow ‘the general public to relate, at the same time, to the same topics’(Habermas 2001: 17). Even though the media are multiple in a PS, the exchanges taking place are inter-communicating. ‘The discussion we may be having on television right now takes account of what was said in the newspaper this morning, which in turn reports on the radio debate of yesterday, and so on. That’s why we usually speak of the PS, in the singular’(Taylor 1995:259). What takes place in a PS is a collective effort of truth-seeking both in the sense of objectively/scientifically determining cause-and-effect relationships and subjectively/normatively

building/renewing the value-system of a society (Risse 2000). The PS gives

deliberation a ‘spatially and temporally extended form of publicity’(Bohmann 1996: 43), which helps to relieve the constraint of ‘deliberative economy’where the

legitimacy of deliberative results remain questionable due to the fact that participation in a given time and space can never be broad enough to include all. With the presence

of a PS, the idea of legitimacy can be detached from ‘a head count of (real or imaginary) reflectively consenting individuals’(Dryzek 2001: 657).

The PS is important not just to those who have much to say and who want others to listen. Being a social space sustaining a shared way of comprehending the world both in terms of facts and values, it is important to those who feel they have little to say as well. In a PS, therefore, ‘actors not only communicate among themselves but also address their communication to a third other, i.e. to an audience.’(Trenz and Eder 2004:9). The information, analysis, and viewpoints made readily available in a PS help the silent individuals to make sense of the overwhelmingly complicated public affairs. The PS is hence not just where the political agenda is settled, but also where individual preferences are shaped (Neyer and Schröter 2005:6).

To better understand the PS, it may be helpful to distinguish its functions between horizontal and vertical ones. Horizontally, the PS performs society-making functions by connecting citizens with one another. Vertically, it allows public opinion to steer public policies, hence connecting the society with the state.

The literature of deliberative democracy illuminates how the PS, inherently deliberative in its operational logic, serves to connect citizens with one another. Unlike aggregative democracy, which aims at gathering individual preferences and transforming these preferences into a collective choice in as fair and efficient a way as possible, the deliberative approach arrives at collective decision-making through open and un-coerced public reasoning among equals. In aggregative democracy, citizens are treated as atomized individuals. Since the interests of each individual are

sacrosanct, there is no need for citizens to leave the private realm of personal interests to interact with others with similar or dissimilar preferences. Deliberative democracy, in contrast, envisions a distinct idea of a public formed from the interaction of citizens. Reaching a collective decision is a process of reason-giving whereby the initial

preferences of individuals are subject to modification. The point of public deliberation, thus, is not to discover the ‘correct’answers, but to ensure that as many points of view as possible are considered. The outcomes of the democratic process are legitimate only if they receive reflective assent from all that are subject to the decision (Miller 2000; Cohen and Sabel 1997; Young 2000; Bohmann 1996; Cohen 1989; Manin 1987).

This logic of deliberative democracy implies that the PS does not simply help a society to define what it wants, but by being reflective, it also helps the society to

define and thematize itself (Eriksen & Fossum 2002; Schlesinger & Fossum 2005). It is not just a sphere in which a ready-constituted people debates and decides what institutions and policies it should have, but also a communicative space that helps to constitute social solidarity and create culture (Calhoun 2002). Deliberation within the PS hinges not on ‘the assumption of macro-subjects like the “people”of “the” community but on anonymously interlinked discourses or flows of communication’ (Habermas 1992:11). It enables a collection of persons to transform into ‘a people’ entitled to govern itself democratically (Calhoun 2002). ‘Collective identity has to be made rather than merely discovered’(Eriksen 2000:55).

This understanding of the PS is the basis on which scholars like Habermas and Weiler refute the idea that the existence of a fixed demos—by whom and for whom democratic discourse takes place—must precede democracy. For these scholars, the relationship between ‘demos’and ‘identity’on the one hand and ‘democracy’and the

‘praxis of citizens’on the other is considered mutually constitutive, with the PS being

the indispensable medium that makes solidarity among strangers possible (Habermas 1992, 1995, 2001; Weiler 1995, 2001; Offe 2002; Risse 2003; Van de Steeg et al. 2003; Eriksen & Fossum 2004; Eriksen 2005; Zürn 2000; Caporaso 2005). Understood this way, Demos refers not to the coming together of a shared ethnos and/or organic culture, but of ‘shared understanding of rights and societal duties and shared rational, intellectual culture which transcend organic-national differences’ (Weiler 1995: 243-4). The normative requirements of the democratic process—such as autonomous individuals with freedom of opinion and information—and the democratic process—such as elections—are seen as mutually reproductive (Zürn 2000: 186).

Beyond generating public opinion, social solidarity, and identity, a PS also has the vertical functions of empowering the citizens to hold the state accountable and to challenge, inflect, and steer public policies (Fraser 2005:40; Taylor 1990:98). ‘The public sphere is not prior to or independent of decision-making agencies but is created and formed in opposition to them—as a vehicle to test the legitimacy of legal

provisions and as a counterweight to governmental power’(Eriksen 2000:55). In fact, what gave birth to the emergence of the bourgeois PS in the 18thCentury in the first place was precisely the need of the private people (the bourgeois) to come together to confront the absolutist state through the public use of reason (Habermas 1989: 27; Taylor 1995: 217-8). Within the bourgeois PS, ‘the best rational argument and not the identity of the speaker was supposed to carry the day’(Forbath 1998:982). The emphasis of reason and de-emphasis of status effectuated an equal relationship

between policy-makers and policy-receivers and made the notion of self-rule plausible. The government is put under the pressure to rule in the midst of a reasoning public. Hence, in taking their decisions, parliaments and courts must concentrate and enact what has already been emerging out of debate among the people. At the same time, the legislative deliberation that is made public further informs public opinion and allows it to be maximally rational (Taylor 1995:264).

Democracy is least constrained and most authentic in the ‘communicatively fluid’PS (Cohen and Sabel 1997:339). Unlike deliberations within the formal political system (where public policies are produced), mass communication within the PS (where public opinions are formed) is relieved of the burden of decision-making. This has the effect of intellectualizing the deliberation within the sphere and elevates the quality of collective truth-seeking (Habermas 1996; Flynn 2004). Whereas the PS has no capacity to solve problems on its own, it can act as a sounding board for problems that need attention, amplify the pressure of problems, and oversee the way the

problems are handled inside the formal political system. The informal PS is to act as a ‘context of discovery,’while institutionalized deliberative bodies take on the role of a ‘context of justification’(Flynn 2004). Without information drawn from the former, even if it intended to, the state will be unable to remain sensitive to the influx of issues, value orientations, and programs originating from the society, and be bound by the approximate consensus emerging from the informal communication to more or less rational premises.

Circumventing the No EPS Problem?

If the existence of a PS is crucial for democratic legitimacy at the national level, there is no reason to think that a supra-/trans-national governing relationship can be democratically legitimate in the absence of a PS. In fact, signs of the detrimental effects of the absence of an EPS have been unfolding for some time. In tackling the legitimacy problem of the EU, some treat the absence of an EPS as irremediable and suggest solutions that could presumably circumvent the problem of no PS. Grimm, for instance, argued that the strong links between the individual and the governing bodies required of democracy are absent at the European level. Decisional power, therefore, should remain at the state level, where the mediation processes including the

communication media, political parties, and citizens associations are better developed (Grimm 1995). Similarly, Scharpf argues that since the EU lacks the ‘thick’collective identity to justify the binding effect of a majority decision, to legitimize the EU,

efforts should be focused on decreasing the Union’s problem-solving deficits (Scharpf 1999). Circumventing the no EPS problem, hence, the mainstream literature considers the legitimacy of the EU to derive from either the representative mechanism inherent in the design of the institutions (the representation model), or the problem-solving capacity of EU governance (the regulatory-state model), or both (Caporaso 2005; Dehousse 1998). A closer examination of these arguments, however, reveals the limitations of tackling the EU’s legitimacy deficit by working around the problem of no PS, for the persisting absence of the EPS severely discounts the effects of the measures and institutional designs aimed at legitimating the EU.

At the core of the representation model is the notion that citizens in a democracy are empowered to ‘throw out the rascals’that ill represent their interests. Within the EU context, the ‘rascals’that the citizens are supposedly empowered to ‘throw out’ should be found in the European Parliament, the Council, and the national parliaments. The reality, however, is that given the nebulous way the competencies are assigned, it is unrealistic to expect voters to make informed decisions about throwing out

representatives that performed poorly with respect to EU affairs (Christin, Hug, and Schultz 2005). The European elections, for instance, are hardly ever determined by European issues. This phenomenon not only deprives voters of the opportunity to influence EU affairs but also deprives them of the opportunity to become familiar with and understand European affairs through elections. In the case of the Council, national executives continue to be judged almost exclusively according to their performances at home even though they are legislators in the EU context. In fact, due to the limited knowledge of the citizens with regard to European affairs, national executives have long used the EU as the scapegoat for unpopular policies. If it is unrealistic to expect voters to throw out the rascals in the European Parliament and the Council, it is even less realistic to expect voters to hold national parliamentarians responsible for policies produced by the EU. Given how little voters understand European affairs, national parliamentarians’time and energy invested in European affairs are unlikely to catch the voters’attention and secure votes for national parliamentarians. ‘No demand, no supply’can largely explain the ‘it’s not my job’ mentality pervasive among national parliamentarians towards the EU.

In contrast to the input-oriented, procedural democracy embodied in the

representation model, the regulatory-state model focuses on consequential democracy and output-oriented legitimacy. The point of the EU is not to follow majority rule and maximize the representativeness of its institutions but to fulfill its role as a specialized, independent regulator (Majone 1994; 1998; 2006). The model acknowledges the

redistributive implications of efficiency-enhancing policies, but insists that the redistributive problem can be easily resolved if the efficiency gains are large enough to compensate the losers.

The question then, in view of the absence of an EPS, is who should determine whether the efficiency gains are ‘large enough’,who thelosers should be, and how they should be compensated. The model points out that the two-stage decision-making process of the EU—problem solving followed by bargaining—is ideal for resolving this problem: Member States that are negatively affected in the first stage can be duly compensated in the bargaining stage (Majone 1998: 28). This argument would have been more convincing had ‘nationality’been the only cleavage in the competition of resources. Given that EU regulation policies affect different domestic actors

differently, the empowerment of the national executives to single-handedly identify problems, set agendas, and determine how the costs and benefits should be distributed can hardly be justified. Moreover, specialized knowledge of experts does not

necessarily embody disinterested solutions to problems (Calhoun 2002:165; Caporaso 2005). Determining where ‘facts and norms merge’is an exercise that requires the involvement of more than just a circle of experts and interest groups and must refer to deliberation that takes place in the PS (Habermas 1996; Steffek 2003). Even theories of deliberative supranationalism, directly-deliberative polyarchy, and network

governance (Joerges and Neyer 1997; Joerges 2002; Eriksen 2000; Eriksen & Fossum 2002; Cohen and Sabel 1997; Eising and Kohler-Koch 1999), which stress the

importance of deliberation and direct participation, fail to address the problem that these so-called deliberative processes are limited to ‘trans-national networks of stakeholders’and ‘sporadicdiscourses among the editorials of high-quality newspapers’(Neyerand Schröter2005:6).

Absent an EPS, relevant interests are systematically excluded from the various specialized committees and policy networks in the EU. The epistemic quality of deliberation, in other words, is achieved at the expense of broad participation (Eriksen 2000; Neyer 2006). In emphasizing the importance of ‘reason-giving’by independent agencies in the process of policy-making, Majone cites the American APA

(Administrative Procedure Act) as a way for the EU to ensure the accountability of independent agencies. The problem is, the disclosure of the data, methodology, reasoning, and evaluation of consequences can only become meaningful to the public if there exists a medium consisting of news analysis, op-eds, and commentaries, in-depth reports with arguments and counterarguments that refer to and refute one another. Such a medium, which helps the public to understand and assess the impact

of the new regulations, is absent in the EU.

To summarize, tackling the EU’s legitimacy problem by dismissing the absence of an EPS as either unimportant or irremediable has proved problematic. In a

democracy, representative institutions and problem-solving capacities can yield legitimate public policies only when the representation and problem-solving mechanisms are embedded in a stable and lively PS where unorganized and

anonymous communications are constantly taking place to help citizens to make sense of public affairs.

Is There a European Public Sphere?

That Europe lacks a PS is not a view shared by all. The existence of European audio-visual spaces (newspapers, television, internet), academic debate, representative assemblies, cross-border social movements, NGOs, and identity politics indicates that an EPS is ‘not totally missing’(Eriksen 2000; 2005; Eriksen & Fossum 2002). Others use content analysis of media reports to demonstrate that an EPS is present. Trenze analyzed news coverage of European governance and policy-making in the quality press of the Member States during the year 2000 and found that an average 35.2% of all the political news articles in individual newspapers are European political

communication (Trenz 2004). For Risse and Van de Steeg et al., Trenz’s criterion speaks only of the necessary condition for an EPS. To claim that an EPS exists, the various national public spaces need to be interconnected through a common discourse that frames particular issues as common European problems. In the common

discourse, fellow Europeans must be treated as legitimate participants, using similar frames of reference, meaning structures, and patterns of interpretation. Applying this set of more stringent criteria, the scholars found, as did Trenz, that a fledgling EPS is indeed present (Risse 2002, 2003; Van de Steeg et al. 2003).

If we heed the functional aspects of the PS highlighted in the previous sections, however, it becomes clear that content analysis of media reports looks only at the ‘delivering end’(voice utterance) of the PS and tells us nothing about the ‘receiving end’(whether readers/audience have become better informed and more capable of making sense of EU affairs) of the sphere. The mere free flow of ‘flat’information and voice utterance in a cross-national space do not by themselves constitute a PS. Rather, the claim that an EPS is present must be supported by empirical evidence showing that the knowledge of, dialogue among, and power to influence European

public policies by the citizens have not only increased but also transcended the national boundaries.

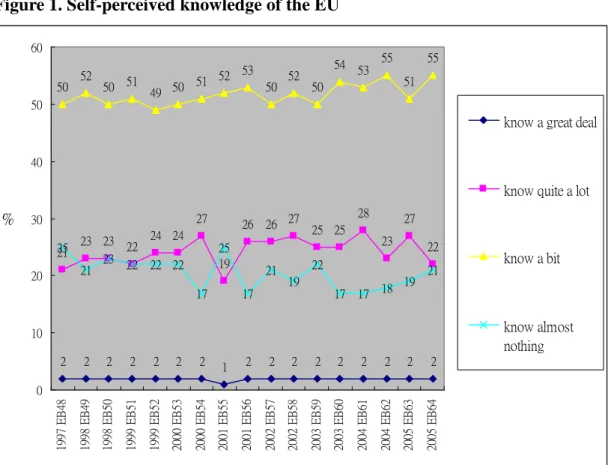

Surveys show that the knowledge of citizens about the EU did not correspond to the rapid growth of competencies in the EU and increased only marginally over the past decade in spite of the increased European news-reporting (figure 1).

Figure 1. Self-perceived knowledge of the EU

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 21 23 23 22 24 24 27 19 26 26 27 25 25 28 23 27 22 50 52 50 51 49 50 51 52 53 50 52 50 54 53 55 51 55 25 21 23 22 22 22 17 25 17 21 19 22 17 17 18 19 21 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 19 97 E B 48 19 98 E B 49 19 98 E B 50 19 99 E B 51 19 99 E B 52 20 00 E B 53 20 00 E B 54 20 01 E B 55 20 01 E B 56 20 02 E B 57 20 02 E B 58 20 03 E B 59 20 03 E B 60 20 04 E B 61 20 04 E B 62 20 05 E B 63 20 05 E B 64 %

know a great deal

know quite a lot

know a bit

know almost nothing

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 48-64

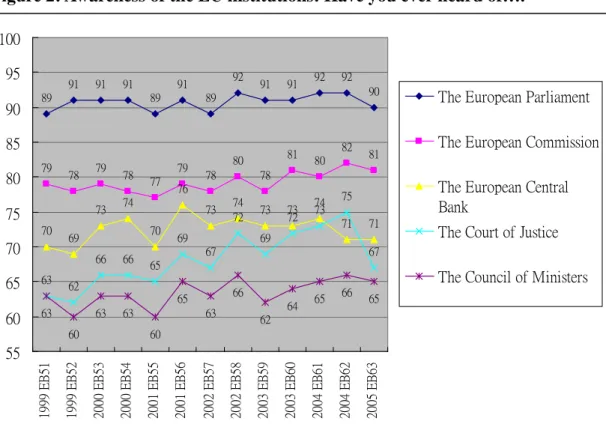

Similarly, the awareness of the EU institutions through media improved only marginally over the past seven years (figure 2). The percentage of respondents that had heard of the Council of Ministers—arguably the most powerful institution in the EU—rarely exceeded 65.

Figure 2: Awareness of the EU institutions: Have you ever heard of…. 89 91 91 91 89 91 89 92 91 91 92 92 90 79 78 79 78 77 79 78 80 78 81 80 82 81 70 69 73 74 70 76 73 74 73 73 74 71 71 63 62 66 66 65 69 67 72 69 72 73 75 67 63 60 63 63 60 65 63 66 62 64 65 66 65 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 19 99 E B 51 19 99 E B 52 20 00 E B 53 20 00 E B 54 20 01 E B 55 20 01 E B 56 20 02 E B 57 20 02 E B 58 20 03 E B 59 20 03 E B 60 20 04 E B 61 20 04 E B 62 20 05 E B 63

The European Parliament The European Commission The European Central Bank

The Court of Justice The Council of Ministers

Compared to the 37% of the respondents in a recent European Voice survey who said they do not understand the way their national governments operate, 64% of the respondents said they do not understand the way the EU institutions operate. More significantly, a large majority (82%) feels that the EU institutions communicate poorly with them (European Voice 2006).

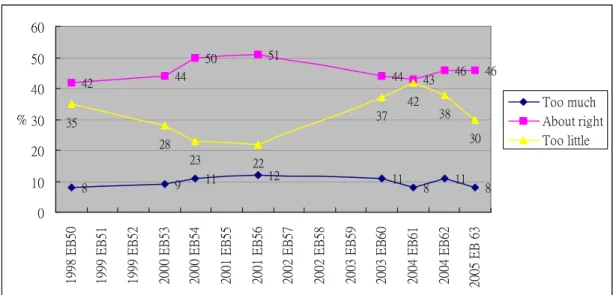

Overall, the Europeans do not seem to be satisfied with the amount of EU news covered by national media (figure 3). In spring 2004, when the European Convention was concluding its work, as many as 42% of the respondents felt that the media coverage of the EU was too little. There is no steady improvement of citizen perceptions towards the amount of media coverage on the EU over time.

Figure 3: Assessment of amount of news coverage of EU affairs

8 9 11 12 11 8 11 8 42 44 50 51 44 43 46 46 35 28 23 22 37 42 38 30 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 19 98 E B 50 19 99 E B 51 19 99 E B 52 20 00 E B 53 20 00 E B 54 20 01 E B 55 20 01 E B 56 20 02 E B 57 20 02 E B 58 20 03 E B 59 20 03 E B 60 20 04 E B 61 20 04 E B 62 20 05 E B 63 % Too much About right Too little Source: Eurobarometer 50-63

The indifference of the citizens towards EU affairs is also evident in surveys that asked citizens how much attention they paid to a list of issues. Invariably over the years, EU affairs ranked behind social issues, the environment, sport, culture, the economy, politics, and foreign-policy/international affairs (EB 52, 55, 57). When asked about the frequency of talking about national or local issues in a recent survey, 44% answered ‘everyday’, 8% answered ‘hardly ever’. When asked about the

frequency of talking about European issues, in contrast, only 7% answered ‘everyday’, and 29% answered ‘hardly ever’(European Voice 2006).

The current form of debate and information dissemination in the EU is therefore a long way from the kind of public deliberation seen in a PS with the horizontal

function of society making and the vertical function of policy steering. Having long been an elite game, European integration had provided European political elites enormous opportunities to socialize with one another within the EU institutions. From the European Council, Commission, and Parliament to the countless committees, political elites from different countries have been socialized to the effect that, even where the stands remain diverse, they can not only communicate with one another effectively, but also produce binding policies efficiently. (Wessels 1998; Zürn and Checkel 2005; Hooghe 2001, 2005; Beyers and Dierickx 1998; Beyers 2005).

Outside the formal institutions, the elites are increasingly served and addressed as a single entity by a specialized European media structure composed of newspapers such as the Financial Times and The Economist (Schlesinger and Kevin 2000). The EU norms and cultures resulting from such socialization further creeps—through the process of ‘Europeanization’—into the operation of national and sub-national

governments and even non-governmental groups (Wessels 1998; Kohler-Koch 1999). As a contrast, opportunities for facilitating better understanding and communication among citizens hardly exist. The so-called ‘public reasoning’and ‘truth-seeking’ within a PS that might result in the modification of individual preferences are taking place only within small circles in the EU. Where the Europeans are supposed to be defining the contour of ‘Europe’and thematizing the European society, the elites are doing this for them.

If the horizontal, society-making functions of a PS are absent in the European context, it is even less likely that, vertically, the European communicative space is present to act as a sounding board and empower the citizens to challenge, inflect, and steer public policies. Consequently, none of the EU institutions can, even if it intends to, enact what has already been emerging out of debate among the people. Some see the absence of an EPS as a natural result of the low saliency of issues dealt with at the European level: When the EU begins to deal with issues that are the more immediate concerns of the citizens, the contentiousness of the EU politics will lead to the emergence of an EPS (Moravcsik 2005:374). Implicit in this argument is an elitist bias that takes the policy-makers’exclusive agenda setting power for granted. It misreads the lack of means for citizens to participate in the EU affairs as apathy by choice: Where a PS does not exist; citizens are unable to understand, sort out, and determine the salience of issues and the desirability of placing new issues on the EU agenda. The prevailing journalistic styles of reporting EU news, which inform citizens about legislation only after their adoption and leave out the vital details of what influences had been exerted and by whom, only reinforce the perception that public

opinion matters little (Schlesinger and Kevin 2000:216).

Absence of EPS and EU Constitution-Making

While it was hoped that the Constitution-making process could serve as a catalyst for creating solidarity among the citizens (Habermas 2001; Closa, Fossum, and Menéndez 2005), in the absence of an EPS, it is unrealistic to expect citizens to suddenly change their habits and become engaged the moment the political elites summon them to participate in a European-wide debate. Given that a PS is where private people come together to reason, an EPS could be fostered neither top-down nor overnight. There is little wonder, then, that the one-shot attempt to create an EPS by bringing citizens onboard early on in the process of Constitution-making was unsuccessful. A document produced with a high degree of ‘transnationalness’and concerned with collective problems was, therefore, still tested by citizens in an almost exclusively nationalistic way.

Throughout the course of the Constitution-making process, the citizen knowledge level about the CT remained low. A comparison between surveys conducted in June 2003 and October 2003 shows that once the intensive media coverage of the Convention died down, citizen knowledge of the Convention dropped from 45% in June 2003 to 39% in October 2003 (Europe-Flash EB No 142/2:5). Only four countries out of 25 had a majority of respondents having heard of the Convention even after the presentation of the Convention’s work to the European Council. As to the objective knowledge about the Convention, the type of text elaborated by the Convention remained unknown to most European citizens. Even during the period when the referenda in France and the Netherlands were attracting a lot of media attention, the interests and knowledge of citizens in the other Member States remained low (Eurobarometer 63:138). While the number of citizens who had never heard of the Constitution decreased by fifteen percent between Autumn 2004 and Spring 2005, with the exception of France and the Netherlands, the corresponding increase in the number of citizens who had heard of the Constitution was found mainly in the group that ‘knew very little about’(up 14%) rather than the group that ‘knew the contents of the Constitution’. The entire Constitution-making process, in fact, barely made any difference in citizens’self-perceived knowledge of the EU (Figure 1).

On first sight, the debates in France and the Netherlands prior to the referenda appear to be good evidence that citizens did participate in the European-wide debate.

A closer look, however, reveals that the debates that seemingly involved ordinary citizens had come too little too late. They were neither an integral part of the ‘debate on the Future of Europe’nor of the drafting process. In fact, the CT was not even necessarily the focal point. The exploitation of the campaign by domestic parties not only failed to invoke the European perspective in voters, but also had the effect of ‘re-nationalizing’the debate that was made European by the elites.

In France, the choices of politicians to put their weight behind either Yes or No were determined more by domestic party politics than by the content of the

Constitution. The campaign saw the unfolding of a power struggle among and within political parties—particularly within the Socialist Party between Laurent Fabius and François Hollande. Fabius’move to champion the No campaign, for instance, was seen as a calculated decision to rally the radical left to position himself as the left’s candidate for the presidential election (Financial Times, 2005). That the debate was dominated by national rather than European concerns was also demonstrated by the fact that both camps exploited the strategy of Anglo-Saxon bashing. While Chirac insisted that saying yes to the Treaty is saying no to the Anglo-Saxon liberalizing agenda, the No camp threatened that saying yes to the ‘pro-America British plot’is saying yes to ultra-liberalism and surrendering to the invasion of the ‘Polish

plumbers’and the ‘evil forces of globalization’. The No camp also cunningly equated saying yes to the CT with ‘saying yes to Chirac.’As to the degree to which citizens perceived they had been informed, according to a survey conducted in November 2004, only 4% felt they were ‘very well-informed’, while 27% felt ‘very

poorly-informed’(CSA Survey conducted on November 16-17, 2004). With regard to

citizen interest in the debate leading to the referendum, 27% of the respondents said they were interested, while 71% were not (CSA Survey conducted on December 9, 2004). As the referendum approached, however, the interest level of the public did eventually pick up (Sofres Survey conducted between March and May 2005).

In the Netherlands, the campaign was noticeable for the ‘non-debate’. The inexperience of the government in running a referendum contributed to the underestimation of the efforts required to win the referendum (Harmsen 2005). A post-referendum survey shows that ‘lack of information’(32%) was a far more important reason given by the ‘no’voters than ‘fear of the loss of national

sovereignty’(19%) for opposing the Constitution (Figure 4). To the extent that the debate did take place, the dissatisfaction and pessimism with domestic politics, stagnant economy, and the future of the society became the core concerns, while the CT per se received little attention (de Beus 2006). Even after the referendum

campaign, most citizens could be described only as ‘somewhat interested’in

European affairs, with less than 4% saying they were ‘very interested’(Aarts & van der Kolk 2006). Similar to the situation in France, all major parties (representing 85% of parliamentarians), the employers association, the trade unions, and mainstream newspapers all stood behind the yes campaign, turning the referendum into a

confrontation between the Dutch political elite and citizens (The Economist, May 21, 2005).

Figure 4: What are all the reasons why you voted ‘No’at the referendum?

6% 6% 6% 6% 7% 8% 13% 14% 19& 32% 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Opposition to further enlargement Too technocratic / juridical / too much regulation The draft goes too far / advances too quickly I do not see what is positive in this text It will have negative effects on the employment situation in the Netherlands / relocation of Dutch enterprises / loss

of jobs

I am against Europe / European construction / European integration

Europe is too expensive Opposes the national government / certain political

parties

Loss of national sovereignty Lack of information

Source: Flash EB 172

While it is true that within a nation state regional interests often prevail over national interests as well and political parties can easily exploit national referenda by

blurring the focus of the issue for political gains, the existence of a PS means that the nation as a unit of solidarity is necessarily given significant consideration in the process of reason-giving. The more an argument runs counter to this basic principle the less it will be considered legitimate in the PS. Pertaining to the CT, it is true that the debates preceding national referenda are by definition meant to be ‘national’, it is nonetheless significant that to the extent citizens did participate in EU

Constitution-making, nationality turned out to be the only visible cleavage in the process. This is where the existence of an EPS could have made a difference.

Post-referendum surveys in both France and the Netherlands indicate that the ‘yes’ voters were mainly motivated by factors with a European dimension, while the ‘no’ voters were more preoccupied with dissatisfactory domestic situations (Flash EB 171 & 172; Ipsos 30/05/2005). In other words, the presence of parochialism is in itself not a problem; the problem lies, rather, in the fact that the elitist belief that parochialism can and must be transcended failed to resonate with ordinary citizens. Unsurprisingly, the national debates only produced—as Jean-Luc Dehaene had put it—‘answers to questions other than those which had been asked.’

Conclusion

The Constitution-making experience is full of paradoxes. In spite of the rejection of the CT, the origin and design of the process revealed an increased level of elite sensitivity towards the frustration of the European citizens about being bound by but having no say in European policies. On the other hand, the elites recognition of the problem and efforts to engage citizens failed to translate into effective communication. The horizontal and vertical functions of a PS discussed in this article show that

meaningful European-wide policy debates cannot begin to take shape until an EPS is existent to sustain a constant flow of information, opinions, and counter-opinions. Hence, the reason that the EU needs a PS is not that every ‘normal’democratic state has one but that a PS performs functions that the EU cannot do without. In a

democracy, political discourses that include different voices help the polity to continually reconstitute itself to more appropriately acknowledge and represent the values and vital interests of its people (Neyer 2006: 781).

In the EU, even with strong elite consensus on the urgency to reconstitute the Union to better represent the values and interests of its people, the absence of a communicative space that could help individuals to make sense of the European affairs, facilitate a shared way of understanding the world, and create a common

identity means that a legitimate guidance for such a reconstitution is missing. No democratic government can rule without constantly tending to the repeated expressions of the popular will; it is unrealistic to expect that the EU can be an exception. If no thoughts are put into the fundamental problem of facilitating the emergence of an EPS, no ‘periods of reflection’and ‘calls for debates’will alleviate the frustration, as citizens will not know what to reflect upon.

This diagnosis, however, brings us to the second paradox: Attributing the failure of the Constitution-making process to the absence of an EPS is to call for measures that could facilitate the emergence of an EPS. Amongst the plausible measures, ironically, are exercises such as Constitution-making. Indeed, as was mentioned before, the Constitution-making process was seen by many as a catalyst for the sense of European solidarity. Seemingly, thus, the Union is locked in a vicious cycle: The lack of an EPS reduces the likelihood that the catalyst could succeed in fostering a shared identity, while the absence of an effective catalyst reduces the chances for the emergence of an EPS. This situation reappears in the aftermath of the rejection of the CT. One of the key measures taken by the EU in the ‘reflection period’was the Commission’s ‘Plan D’(‘D’for democracy, debate, and dialogue). Failing to address the broader implications of the absence of an EPS, the Commission repeats the pattern of the Future of Europe debate and the Constitutional Convention and urged national governments to—yet again—seize the opportunity provided by the Plan to ‘kick start the debates and to act as a motor for European change’(IP/05/1272). While in view of facilitating an EPS, ‘Plan D’was both welcoming and necessary, programs like this will yield only limited results if the analysis of this article is valid.

Rather than seeing Constitution-making, Plan D, and the EPS as elements constituting an unbreakable ‘vicious circle’and doomed to fail, however, the relationship between the catalysts and the EPS can be seen as mutually facilitating. Hence, a failed attempt to adopt a Constitution and lukewarm reactions to initiatives such as Plan D can nonetheless have cumulative effects on bringing the Union closer to a condition conducive to the emergence of an EPS. The more public-sphere-like the European communicative space becomes in the process, the more likely that future initiatives of European-wide debates will become genuine public debates with broad participation. The presence of an EPS does not, however, guarantee the eventual ratification of a European Constitution, as the point of the EPS is not, as Moravcsik had reckoned, to ‘muster greater popular support for EU institutions’(2005: 374), but to find out, more accurately than is possible under the current circumstances, what kind of Europe the Europeans want. A democratic EPS will give all views—including

those that question the very existence of the EU—a chance to be heard, discussed, and contemplated upon. In the presence of an EPS, policy makers can be more confident in interpreting polling results: a ‘No’in a referendum means ‘No’to the question asked rather than to the individual or party in power. Moreover, an EPS will reduce the uneasiness among the citizens in that, even for citizens choosing to pay little attention to European affairs, the existence of an EPS composed of anonymous speakers and audiences can give them confidence that ‘somebody out there’is paying attention and monitoring European policy-making.

NOTES

1 Juncker, Barroso, and Borrell expressed this view at a press conference in June, 2005. Whether or not a valid interpretation of the ‘no’vote, this view was taken by many as yet another example of elite arrogance (Dempsey and Bennhold 2005). 2 Interview with a Conventionnel, April 2004, Strasbourg.

References

Aarts, Kees and Henk van der Kolk (2006) ‘Understanding the Dutch “No”’, Political Science and Politics April, 243-46.

Beyers, Jan (2005) ‘Multiple Embeddedness and Socialization in Europe: The Case of Council Officials’, International Organization 59 (4): 899-936.

Beyers, Jan and Guido Dierickx (1998) ‘The Working Groups of the Council of the European Union: Supranational or Intergovernmental Negotiations’, Journal of Common Market Studies 36 (3): 289-317.

Blair, Tony (2006) Speech to the St. Antony’s College in Oxford, 2 February.

Bohmann, James (1996) Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Calhoun, Craig (2002) ‘Imagining Solidarity: Cosmopolitanism, Constitutional Patriotism, and the Public Sphere’, Public Culture 14 (1): 147-71. Caporaso, James (2005) ‘The Emergence of the EU Supranational Polity and its

Implications for Democracy’, in Sergio Fabbrini (ed.) Democracy and

Federalism in the European Union and the United States, pp. 57-75. London: Routledge.

Christin, Thomas, Simon Hug and Tobias Schulz (2005) ‘Federalism in the European Union: the View from Below’, Journal of European Public Policy 12 (3): 488-508.

Closa, Carlos (2004) ‘The Convention Method and the Transformation of EU Constitutional Politics’, in Erik Oddvar Eriksen, John Erik Fossum, Agustín José Menéndez (eds.) Developing a Constitution for Europe, pp. 183-206. New York: Routledge.

Closa, Carlos, John Erik Fossum, and Agustin Jose Menendez (2005) ‘Lessons from the European Constitutional Experiment’, Paper presented at the CIDEL Concluding Conference, Villa Schifanoia, September.

Cohen, Joshua (1989) ‘Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy’, in Alan Hamlin and Philip Pettit (eds.) The Good Polity: Normative Analysis of the State, pp. 17-34. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Cohen, Joshua and Charles Sabel (1997) ‘Directly-Deliberative Polyarchy’, European Law Journal 3 (4): 313-42.

De Beus, Jos (2006) ‘A Dutch Correction of the European way’, EUSA Review 18: 4. Dehousse, Renaud (1998) ‘European Institutional Architecture After Amsterdam:

Parliamentary System or Regulatory Structure’, Common Market Law Review

35: 595-627.

Dempsey, Judy and Katrin Bennhold (2005) ‘EU Leaders and Voters See Paths Diverge’, International Herald Tribune, 18 June.

Dryzek, John S. (2001) ‘Legitimacy and Economy in Deliberative Democracy’, Political Theory 29 (5): 651-69.

Eising, Rainer and Beate Kohler-Koch (1999) ‘Introduction: Network Governance in the European Union’, in Beate Kohler-Koch and Rainer Eising (eds) The Transformation of Governance in the European Union, pp. 3-13. New York: Routledge.

Eriksen, Erik Oddvar (2000) ‘Deliberative Supranationalism in the EU’, in Erik Oddvar Eriksen and John Erik Fossum (eds) Democracy in the European Union—Integration Through Deliberation, pp. 42-64. London: Routledge. --- (2005) ‘An Emerging European Public Sphere’, European Journal of Social

Theory, 8 (3): 341-63.

Eriksen, Erik Oddvar and John Erik Fossum (2002) ‘Democracy through Strong Publics in the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (3): 401-24.

--- (2004) ‘Europe in Search of Legitimacy: Strategies of Legitimation Assessed’, International Political Science Review 25 (4): 435-59.

Financial Times (2005) ‘Rebel with a Cause Pushes Intellectual Case for No’, 12 May.

Flynn, Jeffrey (2004) ‘Communicative Power in Habermas’s theory of democracy’, European Journal of Political Theory 3 (4): 433-54.

Forbath, William E. (1998) ‘Habermas’s Constitution: a History, Guide, and Critique’, Law and Social Inquery 23 (4): 969-1016.

Fossum , John Erik and Agustín José Menéndez (2005) ‘The Constitution’s Gift? A Deliberative Democratic Analysis of Constitution Making in the European Union’, European Law Journal 11 (4): 380-410.

Fraser, Nancy (2005) ‘Transnationalizing the Public Sphere’, in Max Pensky (ed.) Globalizing Critical Theory, pp. 37-47. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. Grimm, Dieter (1995) ‘Does Europe Need a Constitution’, European Law Review 1

(3): 282-302.

Habermas, Jürgen (1989) The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere—An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge: Polity Press. --- (1992) ‘Citizenship and National Identity: Some Reflections on the Future of

Europe’, Praxis International 12 (1): 1-19.

--- (1995) ‘Remarks on Dieter Grimm’s “Does Europe need a Constitution”’, European Law Review 1 (3): 303-7.

--- (1996) Between Facts and Norms—Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Harmsen, Robert (2005) ‘The Dutch Referendum on the Ratification of the European Constitutional Treaty’, EPERN Referendum Briefing Paper No 13, 1 June. Hooghe, Liesbet (2001) The European Commission and the Integration of

Europe—Images of Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. --- (2005) ‘Several Roads Lead to International Norms, but Few via International

Socialization: a Case Study of the European Commission’, International Organization 59 (4): 861-98.

Joerges, Christian (2002) ‘”Deliberative Supranationalism”—Two Defences’, European Law Journal 8 (1): 133-51.

Joerges, Christian and Jurgen Neyer (1997) ‘From Intergovernmental Bargaining to Deliberative Political Processes: the Constitutionalization of Comitology’, European Law Journal 3 (3): 273-99.

Kohler-Koch, Beate (1999) ‘The Evolution and Transformation of European Governance’, in Beate Kohler-Koch and Rainer Eising (eds) The

Transformation of Governance in the European Union, pp. 14-35. New York: Routledge.

Magnette, Paul (2003) ‘Deliberating under the Shadow of the Veto’, EUSA Review 16 (4): 1-2.

--- (2004) ‘Deliberation or Bargaining? Coping with Constitutional Conflicts in the Convention on the Future of Europe’, in Erik Oddvar Eriksen, John Erik Fossum, Agustín José Menéndez (eds.) Developing a Constitution for Europe, pp. 207-25. New York: Routledge.

Majone, Giandomenico (1994) ‘The Rise of the Regulatory State in Europe’, West European Politics 17 (3): 77-101.

--- (1998) ‘Europe’s “Democratic Deficit”: The Question of Standards’, European Law Journal 4 (1): 5-28.

--- (2006) ‘The Common Sense of European Integration’, European Journal of Public Policy 13 (5): 607-26.

Manin, Bernard (1987) ‘On Legitimacy and Political Deliberation’, Political Theory 15: 338-68.

Maurer, Andreas (2003) ‘Less Bargaining, More Deliberation—The Convention

Method for Enhancing EU Democracy’, Internationale Politik und Gesellschaft 1: 167-90.

Miller, David (2000) Citizenship and National Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Moravcsik, Andrew (2005) ‘The European Constitutional Compromise and the

Neofunctionalist Legacy’, European Journal of Public Policy 12 (2): 349-86. Neyer, Jurgen (2006) ‘The Deliberative Turn in Integration Theory’, Journal of

European Public Policy 13 (5): 779-91.

Neyer, Jurgen and Schroter Michael (2005) ‘Deliberative Europe and the Rejected Constitution’, Paper presented at the Conference ‘Law and Democracy in Europe’s Post-National Constellation’, EUI, Florence, 22nd-24th, September. Offe, Claus (2002) ‘Is There, or Can There Be, a “European Society”’, manuscript to

be published in Ines Katenhusen and Wolfram Lamping (eds.) Demokratien in Europa. Europäische Integration, Institutionenwandel und die Zukunft des demokratischen Verfassungsstaates, Opladen: Leske.

Risse, Thomas (2000) ‘”Let’s Argue!”: Communicative Action in World Politics’, International Organization 54 (1): 1-39.

--- (2002) ‘How Do We Know a European Public Sphere When We See One’,

manuscript for the IDNET Workshop “Europeanization and the Public Sphere”, EUI, Florence, February.

--- (2003) ‘An Emerging European Public Sphere? Theoretical Clarifications and Empirical Indicators’, paper presented at the EUSA meeting, Nashville, March.

Ross, George (2005) ‘From the Chair’. EUSA Review 18(2): 2.

Scharpf, Fritz W. (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schlesinger, Philip and Kevin, Deirdre (2000) ‘Can the European Union Become a Sphere of Publics’, in Erik Oddvar Eriksen and John Erik Fossum (eds) Democracy in the European Union—Integration Through Deliberation, pp. 206-29. Londond: Routledge.

Steffek, Jens (2003) ‘The Legitimation of International Governance: A Discourse Approach’, European Journal of International Relations 9 (2): 249-75. Taylor, Charles (1990) ‘Modes of Civil Society’, Public Culture 3 (1): 95-118. --- (1995) Philosophical Arguments. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. The Economist (2005) ‘Ahead of the Dutch Referendum on the EU Constitution’, 21

May.

Trenz, Hans-Jorg (2004) ‘Media Coverage on European Governance—Exploring the

European Public Sphere in National Quality Newspapers’, European Journal of Communication 19 (3): 291-319.

Trenz, Hans-Jorg and Eder, Klaus (2004) ‘The Democratizing Dynamics of a European Public Sphere’, European Journal of Social Theory 7 (1): 5-25. Van de Steeg, Marianne, Valentin Rauer, Sylvain Rivet, and Thomas Risse (2003)

‘The EU as a Political Community—A Media Analysis of the “Haider Debate”

in the European Union’, paper presented at the EUSA meeting, Nashville, March.

Weiler, Joseph H.H. (1995) ‘Does Europe Need a Constitution? Demos, Telos and the German Maastricht Decision’, European Law Journal 1 (3): 219-58.

--- (2001) ‘Europe 2000—The Constitutional Agenda’, in Alfred E. Kellermann, Jaap W. de Zwaan, and Jenö Czuczai (eds.) EU Enlargement: The

Constitutional Impact at EU and National Level, pp. 3-14. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press.

Wessels, Wolfgang (1998) ‘Comitology: Fusion in Action—Politico-Administrative Trends in the EU System’, Journal of European Public Policy 5 (2): 209-34. Young, Iris Marion (2000) Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Zurn, Michael (2000) ‘Democratic Governance Beyond the Nation-State: The EU and Other International Institutions’, European Journal of International Relations 6 (2): 183-221.

Zurn, Michael and Jeffrey T.. Checkel (2005) ‘Getting Socialized to Build Bridges: Constructivism and Rationalism, Europe and Nation-State’, International Organization 59 (4): 1045-79.