Title: Association between periodontitis needing surgical treatment and subsequent

diabetes risk: A population-based cohort studyShih-Yi Lin, MD *,†,‡; Cheng-Li Lin, MS§, ǁ; Jiung-Hsiun Liu†,‡; I-Kuan Wang, MD *,†,‡;; Wu-Huei Hsu, MD *,†; Chao-Jung Chen¶, #; I-Wen Ting, MD†,‡; I-Ting Wu, MD**; Fung-Chang Sung, PhD, MPH§, ǁ, Chiu-Ching Huang *,†,‡, Yen-Jung Chang††.

* Institute of Clinical Medical Science, China Medical University College of Medicine, Taichung, Taiwan

†Department of Internal Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

‡Division of Nephrology and Kidney Institute, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

§Management Office for Health Data, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

ǁDepartment of Public Health, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan ¶Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

# Proteomics Core Laboratory, Department of Medical Research, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

**Department of Dentistry, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

†† Department of Health Promotion and Health Education, National Taiwan Normal

University, Taipei, Taiwan Correspondence:

Fung-Chang Sung, PhD, MPH,Professor

China Medical University College of Public Health 91 Hsueh Shih Road

Taichung 404, Taiwan Tel: 886-4-2206-2295 Fax: 886-4-2201-9901

E-mail: fcsung@mail.cmu.edu.tw Yen-Jung Chang, PhD

Department of Health Promotion and Health Education, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

162 He-Ping E. Rd., Sec. 1, Da-An District, Taipei, 106, Taiwan +886-2-7734-1733

Fax +886-2-2363-0326

Running head: periodontitis and risk of diabetes

Key words: periodontitis, retrospective study, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

One sentence summary: Those periodontitis patients needing dental surgery

have increased risk of future diabetes within 2 years than those periodontitis participants without dental surgery.Abstract

Backgrounds: It is well known that diabetic patients have higher extent and severity

of periodontitis, but the backward relationship is little investigated. We assessed the relationship between periodontitis needing dental surgery and subsequent type 2 diabetes in those non-diabetes.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study employing data from the national

health insurance system of Taiwan. The periodontitis cohort involved 22,299 patients, excluding those with diabetes already or diagnosed with diabetes within 1 year from baseline. Each study subject was randomly frequency matched by age, gender and index year with 1 individual from the general population without periodontitis. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to estimate the influence of periodontitis on the risk of diabetes.

Results: The mean follow up period is 5.47± 3.54 years. Overall, the subsequent

incidence of type 2 diabetes was 1.24-fold higher in the periodontitis cohort than in the control cohort, with an adjusted hazard ration of 1.19(95% confidence interval

[CI], 1.10-1.29) after controlling for sex, age and co-morbidities.

Conclusions: This is the largest and nation-based study examining the risk of diabetes in Asian patients with periodontitis. Those periodontitis patients needing dental surgery have increased risk of future diabetes within 2 years than those periodontitis participants without dental surgery.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a major global health concern. The prevalence of diabetes is increasing rapidly not only in the industrial countries but also in low-middle income countries. 1,2The pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes involves a complicate

genetic-environmental interaction. Family history, ethnicity, age, and obesity might play a contributing role. 3,4 Along with the pathologic process, insulin resistance

accompanied by β-cell dysfunction ensues and is the critical determinant of

developing glucose intolerance and diabetes.5 Chronic low-grade inflammation has

been proposed to be the link between insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.6 Studies have investigated the pathogenic role of inflammatory mediators,

such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interlukin-6, in the development of diabetes.7-9

However, few researches have investigated the association between clinical condition of chronic inflammation and incident diabetes.

Periodontitis, a common but complex disease, manifests chronic infection and inflammation of the supporting tissues of the teeth.10 Periodontitis might have

systemic effects, rather than confined within the teeth and periodontitium only.11

Therefore, periodontitis might provide a clinical model to investigate the possible role of chronic inflammation on health. Periodontitis has been reported to be associated with strokes and rheumatoid arthritis.12,13 Till now, two studies have attempted to

demonstrate an association between periodontitis and incident diabetes.14,15 Demmer

et al.14 have reported baseline periodontal disease as an independent predictor of

future diabetes in the US population, but the results are limited because of inability excluding undiagnosed diabetes at baseline. In a study of Japanese adults, Ide et al. did not find significant association between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes.15 Since

periodontitis is common worldwide, knowing its relationship with glucose

homeostasis is important for public health management. Moreover, it has been shown that early detection of glucose intolerance or type 2 diabetes improves the clinical outcome, through life style intervention or pharmacotherapy.16 Type 2 diabetes is an

increasing epidemic in Asia.2 In light of uncertainties regarding the association of

periodontitis and incident diabetes, we used nation-based insurance claims data to investigate the risk of incident diabetes in an Asian diabetic-free cohort with periodontitis.

Methods Data Sources

The Taiwan Department of Health integrated 13 health insurance schemes into a universal insurance program in March 1995. This insurance program has covered approximately 99% of the total 23.74 million citizens and contracted with 97% of hospitals and clinics in Taiwan.17 The National Health Research Institute (NHRI) has

computerized medical claims and selected sets of healthcare data for administrative use and research with information on the basic patient demographic status, disease codes, health care rendered, medications prescribed, admissions, discharges, medical institutions, and physicians providing the services etc. The scrambled identifications secured the patient's’ confidentiality. This study is thus exempted from ethics review. Our study data came from a database containing complete medical claims for one million people randomly sampled from entire insured population. No significant differences exist in the age, gender, and insured amount distributions between patients in this selected database and the original National Health Insurance Research

Database (NHIRD). We utilized this database to follow study cohort over time. We applied codes of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to retrieve information on diagnosis.

Study Participants

We enrolled adult patients aged more than 40 years-old with periodontal disease based on claims data (ICD-9-CM codes 523.4 and 523.5) between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2009. To ensure the accuracy and severity of periodontitis, we selected those who underwent periodontal operation including subgingival curettage

(procedure codes 91006C, 91007C, and 91008C) and periodontal flap procedure (procedure codes 91009C and 91010C) as the severe periodontitis cohort. A

comparison cohort selected randomly from those with periodontitis but did not receive periodontal operation. The index date was defined as the date receiving the periodontal surgery. We define the index date as time t0, the first year time t1, the

second year time t2, and annually thereafter (time tn). We excluded all patients with

type 1 or type 2 diabetes diagnosed before the index date or any diabetes recorded between time t0 and time t1. The control cohort was matched with the study cohort at a

ratio of 1:1 and matched by gender, age, and index year using the same exclusion criteria. We tested the proportionality assumption based on the Schoenfeld residuals and found the assumption was violated. In our subsequent analyses, we stratified the follow-up period and fitted separate models.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome is the development of type 2 diabetes which was determined as patients who have been diagnosed with ICD-9-CM codes 250 at least 2 times and concomitantly received anti-diabetic medications. Each study subject was followed until type 2 diabetes (ICD-9-CM codes 250 and received anti-diabetic agents) was diagnosed, or until the time the subject was censored for loss to follow-up, death, termination of insurance, or by the end of follow-up, 31 December 2010. Participants with hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401-405), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM codes 272),

coronary artery disease (ICD-9-CM codes 410-414) and obesity (ICD-9-CM codes 278.00- 278.01) identified before index date were considered as co-morbidities.

Statistical Analysis

SAS version 9.1 for windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. We use the 2 test for categorical variables and t -test for

continuous variables to examine the difference in the distributions of socio-demographic and co-morbidities between the study and the comparison cohort.

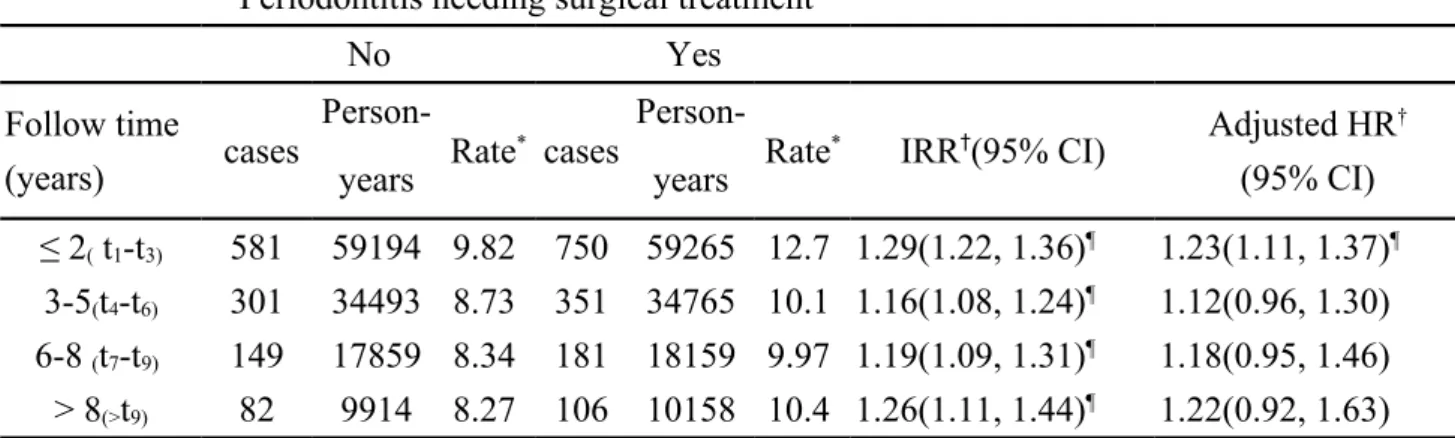

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to estimate the risk of diabetes in association with periodontitis. The follow-up period was partitioned into 4 segments: within 2 years (time t1-t3), 3-5 years (time t4-t6), 6-8 years (time t7-t9), and

more than 8 years (time t9-tn). Poisson regression model was used to examine the

incidence density rates, the incidence rate ratio (IRR), and 95% confidence interval (CIs) of type 2 diabetes differed for categorical variables or over time. The event-free survival functions for incident diabetes between 2 cohorts were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to examine the difference. All significant levels were set at a 2-tailed P value.

Results

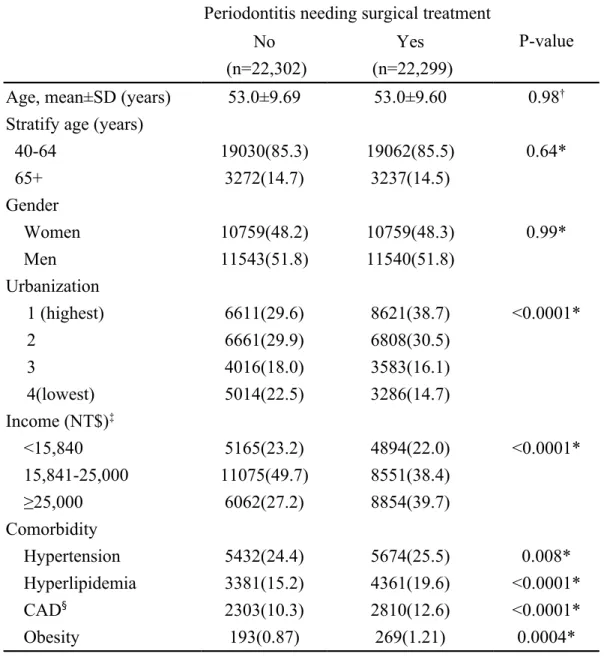

The mean follow up period is 5.47± 3.54 years. The periodontitis cohort included 22,299 participants and the non-periodontitis cohort involved 22,302 participants during the period of 1997-2010 (Table 1). The severe periodontitis and comparison

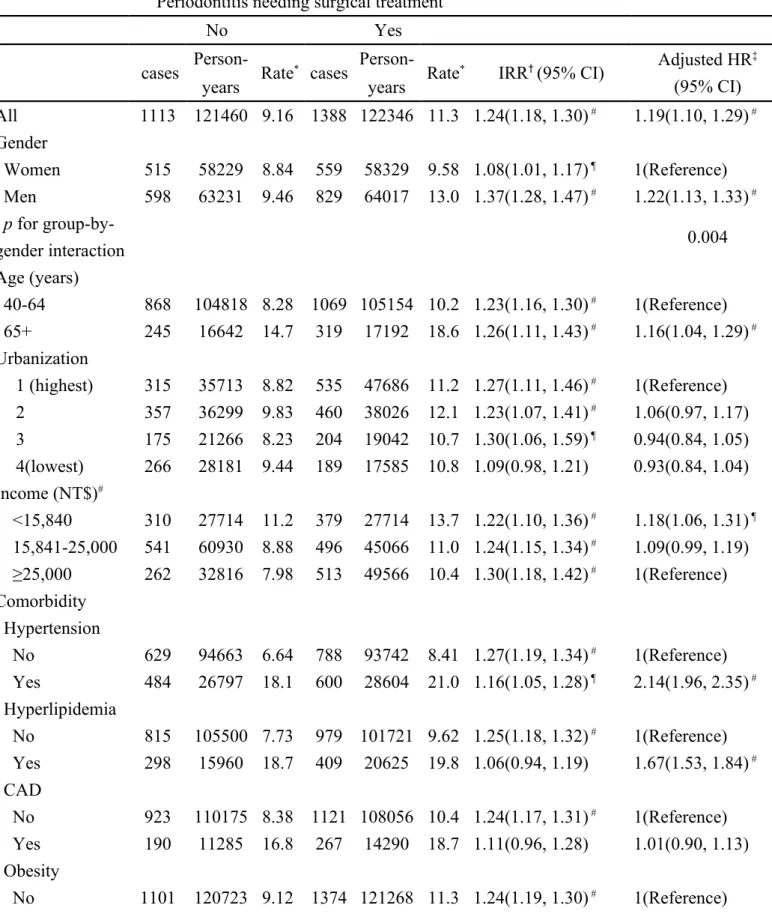

cohort were similar in distributions of age, and gender, with mean age of 53.0 years. The dominant gender was male (51.8%). The severe periodontitits cohort was more prevalent with comorbidities, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease and obesity (all p <0.05). The incidence of diabetes was 1.24-fold higher in the severe periodontitis cohort than in the comparison cohort (11.3 vs. 9.16 per 1,000 person-years) with an adjusted HR of 1.19 (95% CI, 1.10-1.29) (Table 2). The incidence rate ratio of diabetes was higher for men than women. Generally, the incidence of diabetes increased with age in both cohorts. However, the age-specific analysis showed that the incidence rate ratio of type 2 diabetes is younger in severe periodontitis cohort than the control cohort. The adjusted HRs showed that age, income, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were significant risk factors for type 2 diabetes.

Table 3 shows that the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the severe periodontitis cohort decreased with follow-up year, while that in the comparison cohort was increasing. The severe periodontitis cohort to comparison cohort IRR was the highest in earlier period, from time t1 to time t3 (12.7 vs. 9.82 per 1,000 person-years) with an adjusted

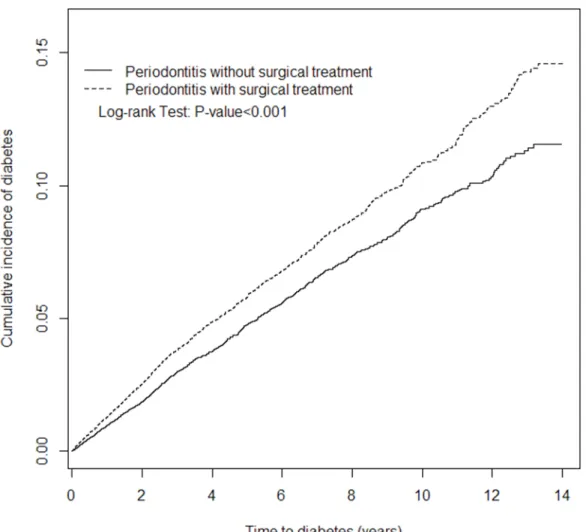

HR of 1.23. The elevated risk disappeared after being followed up for six years. The cumulative incidence of diabetes was higher in the severe periodontitis cohort than

comparison cohort during the entire follow-up period (log-rank test, p-value <0.001) (Figure 1).

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study, we confirmed the association between peridontitis and risk of diabetes. In both cohorts, the incidence of diabetes increased with age. Participants with co-morbidities of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and lower income at baseline are associated with increased risk of incident diabetes. Moreover, increased risk of developing diabetes associated with severe periodontitis is observed between time t1 and time t3 following the periodontal surgery. Though the elevated

risk disappeared after being followed up for six years, the cumulative incidence of diabetes remained significantly higher in the severe periodontitis cohort than

comparison cohort during the entire follow-up period. The above finding suggest that those periodontitis patients requiring dental surgery might have higher risk of

developing diabetes within 3 years than those periodontitis patients who needed no surgery treatment.

Ample clinical studies have established a well-described bi-directional

relationship between diabetes and periodontitis: diabetics tend to have periodontitis, and the severity of periodontitis would influence the glycemic control in established diabetes.19-21 Up to the present, only two clinical studies have evaluated the risk of

incident diabetes in periodontitis individuals.14,15 However, the two studies have

yielded apparently conflicting results. In the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and its Epidemiologic follow-up study, Demmer et al.14 found

that dentate participants with severe tooth loss has an odds ratio of 1.7 for incident diabetes while compared with those have less tooth loss.They14 utilized Periodontal

Index22 at initial dental surveillance which could not reflect tooth mobility, attachment

loss, or furcation involvement. The study is limited in vague method of assessing periodontitis and inability of excluding undiagnosed diabetes at baseline.14 In contrast,

the study of Ide et al. for Japanese individuals aged 30-59 revealed no apparent association between periodontal disease and incident diabetes.15 The results of the

specific study participants cannot be generalized to whole general population.

Furthermore, they use Community Periodontal Index23 which is being questioned as a

reliable epidemiological tool due to inability reflecting the true periodontal status.24

The present study might provide a way to reconcile these findings. Because of the severity of periodontitis varied from mild gingivitis to edentulous, the intra-observer difference and misclassification of periodontitis severity may cause disparity in defining periodontitis among studies. Besides, periodontitis is indeed highly prevalent among adult population. A German dental survey assessed recently that more than 70% of adults have periodontitis and at least one-fourth of them present severe form.25

Therapy for periodontitis included systematic, hygiene, corrective, and supportive treatment.26 Therefore, our study defined only those who received dental surgery for

periodontitis as study participants. It is reported that 91% of adults in Taiwan were affected with periodontitis27, thus we generate a control group which randomly

selected from participants with periodontitis, matched by 1:1 ratio, sex, age, and index year. Based on this study design, we found a significant increasing risk of incident diabetes in our study cohort, while compared with the control. There are several possible explanations and evidence for our finding. Chronic inflammation of periodontitis might represent a triggering factor for insulin resistance.28Highly

vascularity of inflamed periodontium might provide an endocrine-like origin for pro-inflammatory mediators, which the main are TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 all reported to have insulin antagonizing actions.29The periodontal microflora, most Gram-negative

bacteria, might generate endotoxinemia and further worsen insulin resistance.29

Pussinen et al.30 have reported that endotoxemia is associated with an increased risk of

incident diabetes and the risk is independent of the metabolic syndrome.31 In a

subgroup analysis of Hisayama study, Saito et al.32 have observed that deep pocket is

related to current and future glucose intolerance. Their findings suggest periodontitis might be a risk factor for type 2 diabetes but failure to confirm this hypothesis in their study. Furthermore, in an animal model of Zucker Diabetic fatty rats, Watanabe et al.

found that periodontitis could accelerate the onset of severe insulin resistance and the type 2 diabetes.33 These studies have clearly indicated an important relationship

between periodontitis and potential glucose intolerance as well as diabetes. Our findings that patients with periodontitis needing dental surgery are at increased risk of diabetes might reflect that it is the severity of periodontitis rather than treatment which might be associated with the development of diabetes. Thus, it would suggest that preventing worsening of periodontitis severity might lessen the risk of diabetes in those patients with mild periodontitis. Further studies might be needed to investigate this relationship.

Our results also revealed that lower income at baseline had a HR of 1.18 for incident diabetes. Therefore, it may be assumed that it is the poverty that contributes to both the development of periodontitis and diabetes in our study. It have been stated thatlow socioeconomic status aggravated the periodontal condition in individuals with type 2 diabetes.34 Further attempts are needed to minimize the effects of

socioeconomic disparities on incidence of diabetes and periodontitis. In another aspect, we also found that patients receiving periodontal surgery indeed were wealthier than the comparison participants. This might explain why we only see an association within 3 years of follow-up, since wealthier people might receive more medical care and have their diabetes diagnosed sooner.35

Furthermore, our results suggest that increased risk of developing diabetes associated with severe periodontitis is observed within 2 years (between time t1 and

time t3) following periodontal surgery. Demmer et al.14 have reported no

dose-response association could be established between the severity of periodontitis and risk of future diabetes.Ourresult showed that the elevated risk of diabetes disappeared after being followed up for three years Since our study cohort enrolled only those with worst periodontal status needing dental surgery, the excess risk of diabetes between time t1 and time t3 is likely due to the preexisting glucose intolerance and insulin

resistance of past long term chronic periodontitis. On the other aspect, another explanation for the slightly higher hazard ratio is that some periodontal patients have underlying diabetes without being diagnosed before the index year, and this would fit the observation that the diagnosis of diabetes is higher in the periodontal patients in the short term.

Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, although we have excluded the incent diabetes diagnosed within one year from baseline, we could not confirm the casual relationships between

periodontitis and subsequent diabetes. However, we have noted that the association between periodontitis needing surgery and the risk of subsequent diabetes existed within 3 years follow up. Second, we have no precise information about smoking

status, lifestyle, family history, and body-mass index. However, this situation might happen in both groups. Third, certain participants were followed for short observation period (5.47± 3.54 years). However, since our findings also indicated the significant effect in short period (within 3 years), the short observation period would further strengthen our results. Fourth, we did not have precise data about the severity of periodontitis. However, the dental surgery for periodontitis in NHIRD needs strict pre-operative evaluation and assessment reported in electric medical records. The potential for diagnostic bias is unlikely. Finally, there are imbalances of

co-morbidities between our study and comparison cohorts. Certain selection bias may exist, but we have adjusted these confounding factors. The selection bias would be lessened minimally in this study. Our study has several strengths. The comprehensive, detailed, constant, and long follow-up electronic medical records of NHIRD enable the investigation of temporal relationship between periodontitis and diabetes. The nation-based setting, the universal access to health care, and the large study size may make our results more generable and interpretable. Furthermore, the accuracy of diagnosis based on NHIRD has been ensured and established.36, 37

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first nation-based study demonstrating the chronological association between periodontitis and incident diabetes in Asian

population. Asian diabetes has several unique characteristics, including a substantial increase of affected individuals over short period, relatively younger onset, and less obesity.2 There are studies demonstrated that the diabetes in Asia would be related

with major clinical events, such as cancer, coronary heart disease, end stage renal disease, and stroke.38-40 Considering the huge health consequences and economic

impacts of diabetes epidemic, several diabetic risks scores have been proposed.3,41,42

Strong evidence exists that screen and lifestyle intervention of high risk cases for diabetes is protective and cost-effective.43 We observed a phenomenon that within 3

years of follow up, the association between periodontitis and the risk of developing diabetes existed. Our result may help to early screen and introduce intervention into this potentially high risk group of future diabetes.

Acknowledgments— None.

Conflict of interest and source of funding statement: No potential conflicts of

Referenes

1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047-1053.

2. Chan JC, Malik V, Jia W, et al. Diabetes in Asia: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. JAMA 2009;301:2129-2140.

3. Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, et al. Genotype score in addition to common risk factors for prediction of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2208-2219.

4. Talmud PJ, Hingorani AD, Cooper JA, et al. Utility of genetic and non-genetic risk factors in prediction of type 2 diabetes: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ 2010;340:b4838.

5. Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2006;444:840-846.

6. Dandona P, Aljada A, Bandyopadhyay A. Inflammation: the link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol 2004;25:4-7. 7. Spranger J, Kroke A, Mohlig M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to

develop type 2 diabetes - Results of the prospective population-based

European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam study. Diabetes 2003;52:812-817.

8. Liu S, Tinker L, Song YQ, et al. A prospective study of inflammatory Cytokines and diabetes Mellitus in a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1676-1685.

9. Chan KH, Brennan K, You NC, et al. Common variations in the genes encoding C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-6, and the risk of clinical diabetes in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Clin Chem 2011;57:317-325.

10. Laine ML, Crielaard W, Loos BG. Genetic susceptibility to periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2012;58:37-68.

11. Redlich K, Smolen JS. Inflammatory bone loss: pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012;11:234-250.

12. Jimenez M, Krall EA, Garcia RI, Vokonas PS, Dietrich T. Periodontitis and incidence of cerebrovascular disease in men. Ann Neurol 2009;66:505-512. 13. Demmer RT, Molitor JA, Jacobs DR, Jr., Michalowicz BS. Periodontal disease,

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and its epidemiological follow-up study. J Clin Periodontol 2011;38:998-1006.

14. Demmer RT, Jacobs DR, Jr., Desvarieux M. Periodontal disease and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and its epidemiologic follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1373-1379.

15. Ide R, Hoshuyama T, Wilson D, Takahashi K, Higashi T. Periodontal disease and incident diabetes: a seven-year study. J Dent Res 2011;90:41-46.

16. Gillies CL, Lambert PC, Abrams KR, et al. Different strategies for screening and prevention of type 2 diabetes in adults: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2008;336:1180-1185.

17. Wendt C. Six Countries, Six Reform Models: The Healthcare Reform

Experience of Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan. Political Studies Review 2011;9:254-256.

18. Web sites. ICD-9 on line. Available at: icd9cm.chrisendres.com

19. Chavarry NGM, Vettore MV, Sansone C, Sheiham A. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and destructive periodontal disease: A Meta-Analysis. Oral Health Prev Dent 2009;7:107-127.

20. Teeuw WJ, Gerdes VEA, Loos BG. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of diabetic patients - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:421-427.

21. Lalla E, Papapanou PN. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;7:738-748.

22. Russell AL. A system of scoring for prevalence surveys of periodontal disease. J Dent Res.1956;35:350-359.

23. Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN). Int Dent J. 1982;32:281-291.

24. Leroy R, Eaton KA, Savage A. Methodological issues in epidemiological studies of periodontitis--how can it be improved? BMC Oral Health 2010;10:8.

25. Holtfreter B, Kocher T, Hoffmann T, Desvarieux M, Micheelis W. Prevalence of periodontal disease and treatment demands based on a German dental survey (DMS IV). J Clin Periodontol 2010;37:211-219.

26. Pihlstrom BL. Periodontal risk assessment, diagnosis and treatment planning. Periodontol 2000 2001;25:37-58.

27. Lai H, Lo MT, Wang PE, Wang TT, Chen TH, Wu GH. A community-based epidemiological study of periodontal disease in Keelung, Taiwan: a model from Keelung community-based integrated screening programme (KCIS No.

18). J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:851-859.

28. Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1793-1801.

29. Taylor GW, Borgnakke WS. Periodontal disease: associations with diabetes, glycemic control and complications. Oral Dis 2008;14:191-203.

30. Pussinen PJ, Tuomisto K, Jousilahti P, Havulinna AS, Sundvall J, Salomaa V. Endotoxemia, immune response to periodontal pathogens, and systemic inflammation associate with incident cardiovascular disease events. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27:1433-1439.

31. Pussinen PJ, Havulinna AS, Lehto M, Sundvall J, Salomaa V. Endotoxemia Is associated with an increased risk of incident diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:392-397.

32. Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Kiyohara Y, et al. The severity of periodontal disease is associated with the development of glucose intolerance in non-diabetics: The Hisayama study. J Dent Res 2004;83:485-490.

33. Watanabe K, Petro BJ, Shlimon AE, Unterman TG. Effect of periodontitis on insulin resistance and the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Periodontol 2008;79:1208-1216.

34. Javed F, Nasstrom K, Benchimol D, Altamash M, Klinge B, Engstrom PE. Comparison of periodontal and socioeconomic status between participants with type 2 diabetes Mellitus and non-diabetic controls. J Periodontol 2007;78:2112-2119.

35. Szwarcwald C, Souza-Junior P, Damacena G. Socioeconomic inequalities in the use of outpatient services in Brazil according to health care need: evidence from the World Health Survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:217.

36. Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, Lee CH, Lai ML. Validation of the National Health Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 20 (2011), pp. 236–242.

37. Yu YB, Gau JP, Liu CY, et al. A nation-wide analysis of venous thromboembolism in 497,180 cancer patients with the development and validation of a risk-stratification scoring system. Thromb Haemost 2012;108:225-35.

38. Woodward M, Zhang X, Barzi F, et al. The effects of diabetes on the risks of major cardiovascular diseases and death in the Asia-Pacific region. Diabetes Care 2003;26:360-366.

39. So WY, Kong AP, Ma RC, et al. Glomerular filtration rate, cardiorenal end points, and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2006;29:2046-2052.

patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:2754-2764.

41. Aekplakorn W, Bunnag P, Woodward M, et al. A risk score for predicting incident diabetes in the Thai population. Diabetes Care 2006;29(8):1872-1877.

42. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Robson J, Sheikh A, Brindle P. Predicting risk of type 2 diabetes in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QDScore. BMJ 2009;338:b880.

43. Bertram MY, Lim SS, Barendregt JJ, Vos T. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of drug and lifestyle intervention following opportunistic screening for pre-diabetes in primary care. Diabetologia 2010;53:875-881.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics between periodontitis cohorts with and without surgical treatment in 1997-2010

Periodontitis needing surgical treatment

P-value No

(n=22,302)

Yes (n=22,299)

Age, mean±SD (years) 53.0±9.69 53.0±9.60 0.98†

Stratify age (years)

40-64 19030(85.3) 19062(85.5) 0.64* 65+ 3272(14.7) 3237(14.5) Gender Women 10759(48.2) 10759(48.3) 0.99* Men 11543(51.8) 11540(51.8) Urbanization 1 (highest) 6611(29.6) 8621(38.7) <0.0001* 2 6661(29.9) 6808(30.5) 3 4016(18.0) 3583(16.1) 4(lowest) 5014(22.5) 3286(14.7) Income (NT$)‡ <15,840 5165(23.2) 4894(22.0) <0.0001* 15,841-25,000 11075(49.7) 8551(38.4) ≥25,000 6062(27.2) 8854(39.7) Comorbidity Hypertension 5432(24.4) 5674(25.5) 0.008* Hyperlipidemia 3381(15.2) 4361(19.6) <0.0001* CAD§ 2303(10.3) 2810(12.6) <0.0001* Obesity 193(0.87) 269(1.21) 0.0004*

*Chi-Square Test; † Two-sample T-Test

NT$‡: New Taiwan Dollars per month. One New Taiwan Dollar equals

0.03 US Dollar.

Table 2. Incidence and adjusted hazard ratio of diabetes adjusted by sex, age, urbanization, income and comorbidity compared between periodontitis cohorts with and without surgical treatment

Periodontitis needing surgical treatment

No Yes

cases Person- Rate* cases Person- Rate* IRR† (95% CI) Adjusted HR ‡ (95% CI) years years All 1113 121460 9.16 1388 122346 11.3 1.24(1.18, 1.30) # 1.19(1.10, 1.29) # Gender Women 515 58229 8.84 559 58329 9.58 1.08(1.01, 1.17) ¶ 1(Reference) Men 598 63231 9.46 829 64017 13.0 1.37(1.28, 1.47) # 1.22(1.13, 1.33) # p for group-by-gender interaction 0.004 Age (years) 40-64 868 104818 8.28 1069 105154 10.2 1.23(1.16, 1.30) # 1(Reference) 65+ 245 16642 14.7 319 17192 18.6 1.26(1.11, 1.43) # 1.16(1.04, 1.29) # Urbanization 1 (highest) 315 35713 8.82 535 47686 11.2 1.27(1.11, 1.46) # 1(Reference) 2 357 36299 9.83 460 38026 12.1 1.23(1.07, 1.41) # 1.06(0.97, 1.17) 3 175 21266 8.23 204 19042 10.7 1.30(1.06, 1.59) ¶ 0.94(0.84, 1.05) 4(lowest) 266 28181 9.44 189 17585 10.8 1.09(0.98, 1.21) 0.93(0.84, 1.04) Income (NT$)# <15,840 310 27714 11.2 379 27714 13.7 1.22(1.10, 1.36) # 1.18(1.06, 1.31) ¶ 15,841-25,000 541 60930 8.88 496 45066 11.0 1.24(1.15, 1.34) # 1.09(0.99, 1.19) ≥25,000 262 32816 7.98 513 49566 10.4 1.30(1.18, 1.42) # 1(Reference) Comorbidity Hypertension No 629 94663 6.64 788 93742 8.41 1.27(1.19, 1.34) # 1(Reference) Yes 484 26797 18.1 600 28604 21.0 1.16(1.05, 1.28) ¶ 2.14(1.96, 2.35) # Hyperlipidemia No 815 105500 7.73 979 101721 9.62 1.25(1.18, 1.32) # 1(Reference) Yes 298 15960 18.7 409 20625 19.8 1.06(0.94, 1.19) 1.67(1.53, 1.84) # CAD No 923 110175 8.38 1121 108056 10.4 1.24(1.17, 1.31) # 1(Reference) Yes 190 11285 16.8 267 14290 18.7 1.11(0.96, 1.28) 1.01(0.90, 1.13) Obesity No 1101 120723 9.12 1374 121268 11.3 1.24(1.19, 1.30) # 1(Reference)

Yes 12 737 16.3 14 1078 13.0 0.77(0.49, 1.21) 0.97(0.67, 1.41) Rate*, incidence rate, per 1,000 person-years

IRR†, incidence rate ratio, per 1,000 person-years

Adjusted HR‡: multivariable analysis including sex, age, income, urbanization, and

comorbidities of hypertension, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, and obesity

§ NT$: New Taiwan Dollars per month. One New Taiwan Dollar equals

0.03 US Dollar.

Table 3. Hazard ratio for diabetes compared between periodontitis cohorts with and without surgical treatment by follow-up duration

Periodontitis needing surgical treatment

No Yes

Follow time

(years) cases

Person-Rate* cases Person- Rate* IRR†(95% CI) Adjusted HR † (95% CI) years years ≤ 2( t1-t3) 581 59194 9.82 750 59265 12.7 1.29(1.22, 1.36)¶ 1.23(1.11, 1.37)¶ 3-5(t4-t6) 301 34493 8.73 351 34765 10.1 1.16(1.08, 1.24)¶ 1.12(0.96, 1.30) 6-8 (t7-t9) 149 17859 8.34 181 18159 9.97 1.19(1.09, 1.31)¶ 1.18(0.95, 1.46) > 8(>t9) 82 9914 8.27 106 10158 10.4 1.26(1.11, 1.44)¶ 1.22(0.92, 1.63)

Rate*, incidence rate, per 1,000 person-years IRR†, incidence rate ratio, per 1,000 person-years

Adjusted HR†: multivariable analysis including sex, age income, urbanization, and

comorbidities of hypertension, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, and obesity

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of diabetes compared between periodontitis cohorts with and without surgical treatment