No Longer a Teacher Monologue – Involving EFL Writing Learners

in Teachers’ Assessment and Feedback Processes

Shu-Chen Huang

Foreign Language Center, National Chengchi University ABSTRACT

This paper reports the design of learning-oriented formative assessments in an EFL writing course that involved learners in regularly responding to teacher feedback. Following major assessment and feedback frameworks developed recently, these formative assessments were explicated in three aspects: the scheduling of learning and assessment activities, instruments used to encourage learner responses to teacher assessment feedback, and the arrangement of gradually removing scaffolds provided by the teacher and peers. Four batches of learner essays written throughout the semester were rated for quality. Results revealed significant improvement from the first to the second, from the second to the third, and from the third to the fourth

assignment. To further examine the characteristics of learning, analysis was conducted on the teacher-learner dialogues documented in teacher feedback forms and learner revision reports. Two learners were chosen as cases to exhibit their gradual

development on cognitive and affective dimensions. It was found that, with the repetitive opportunities to perform, assess, articulate, and reflect as afforded by

conversations on these formative assessments, learners could revisit major themes and deepen understanding, receive consistent support adjusted for their personalities, and co-construct meaning through challenges and scaffolds.

Keywords: assessment, feedback, dialogic teaching, EFL writing

INTRODUCTION

Despite considerable success on language testing know-how in the past, a major problem in assessments has been identified in many recent research reports (Black & Wiliam, 2009; Davison & Leung, 2009; McMillan, 2007; Pryor & Crossouard, 2008; Rea-Dickins, 2006), that is, the separation of testing and assessment from teaching and learning. To be more specific, the necessity of linking assessment with teaching to enhance learning has been acknowledged and the potential of assessment in serving teaching and learning needs in the day-to-day classrooms has been widely explored.

In response to this, many policy makers in different parts of the world, such as U.S., U.K., and Hong Kong, are shifting away from norm-referenced uniform assessments to classroom-based ones that consider particular teaching/learning contexts, and consequently placing more responsibilities on the classroom teachers. Similarly, in a discussion on the future of language testing research, McNamara (2001) pointed out that meeting teacher/learner demands would be one important aspect in the agenda of language assessment research.

The capacities of assessment, especially formative assessment, in facilitating instruction and learning has been described as akin to the functions of a global positioning system (Stiggins & Chappius, 2012) in navigation. Teachers and learners need good assessment to help them establish a clear understanding on where learners are going, i.e. the learning objectives, as well as where learners currently are in

relation to that destination, so as not to lose a sense of direction in the learning journey. In addition, engaging learners in formative assessment has also been considered a viable approach toward fostering learner self-regulation because learners are empowered with more responsibilities in planning and evaluating their progress (Boud & Molloy, 2012; Nicol & Marfarlane-Dick, 2006; Orsmond & Merry, 2013). Although the significance of learning-oriented assessments has been recognized and its rationale widely discussed, obstacles to fully taking the advantages of assessment for better teaching and learning lie in at least three areas.

First of all, assessments have been habitually assigned a peripheral or terminal role in most course designs in today’s mass higher education (Graham, 2005). When planning a course, the teacher usually starts with the topics/themes to be covered, which are often followed by decisions on the teaching/learning strategies.

Assessments usually are not scheduled until certain units have been completed, if not at the end of the course. By the time the assessment results are available, the teacher and learners are finally informed of whether and how much the learning expectations have been met. But at this point it is too late for them to do anything. This practice makes it difficult for teachers and learners to regularly and constantly assess learning progress and take timely remedial actions to strengthen teaching and learning.

To address the dilemma, Graham (2005) suggested that the content-based approach to course design has to be replaced by an assessment-based approach, in which the steps in a course design are reversed. Taken into consideration first are the goals and expectations of a course. Assessments come into play very early on and continue throughout the term to help both teachers and learners understand the gap between goals and learners’ status quo. Once the gap is well understood, appropriate strategies could be applied and eventually the more focused topics and themes contingent on learner needs covered. In other words, assessments should be

deliberately designed into and throughout the lifespan of a course, with time and opportunities arranged for all parties to reflect upon and make up for problems in actual learning, thus making the classroom experience more purposeful and rewarding.

Secondly, assessment events are mostly occasional, so there is little room for productive and engaging teacher-learner dialogues and the classroom is still dominated by one-way teacher monologues. One should be reminded that when assessments are used to serve the purpose of learning and teaching, the crux is not on the assessment itself, but the assessment-induced thinking and learning that becomes more focused and problem-oriented because of assessments. Well-designed

assessment events pave the way for a forum that enables learners to be aware of what they do and do not know well and for teachers to teach to the relevant learner needs. Moreover, once the teacher and learners start a focused conversation, the dialogues around assessments would form a continuous flow as learners progressively develop their understanding and proficiency. As advocates of dialogic teaching (Alexander, 2008; Mercer, 1995; Nicol, 2010) have pointed out, it is the cumulative quality that “contribute(s) to the cohesive, temporal organization of pupil’s educational experience” (Mercer, Dawes, & Staarman, 2009; p. 354). Therefore, assessments are just the

antecedents of learning-related dialogues. For assessments to make learning more effective, efforts are needed to allow follow-up dialogues between teachers and learners. Such dialogues are currently absent from most higher education classrooms because of contextual and pedagogical constraints.

Thirdly, among the recent proliferation of publications on formative and

educative assessments, there is an imbalance between theoretical and empirical study reports. Frameworks and principles burgeon rapidly. Discussions on the “why” and “ought to” of formative assessments are quite convincing, but practitioners are largely left on their own to wonder about the “how” and “how true” of those plausible ideals. Large-scale review studies such as Hattie and Timperley (2007) and Evans (2013) pinpointed this imbalance and the lack of empirical data, making a systematic validation and cross comparison of theoretical frameworks almost impossible. Furthermore, even though empirical data and analyses have gradually been

accumulating, most of the findings are from disciplines and contexts (e.g. science and math education in primary and secondary levels) that prohibit direct application in areas such as the English-as-a-Foreign-Language (EFL) education in Taiwan.

Based on the aforementioned background, this study had two major purposes. First, it documented an attempt to translate most updated assessment and feedback theories and principles (mostly within ten years) into realities in a tertiary EFL setting in Taiwan. Secondly, it analyzed the resulted learner performance and the

teacher-learner dialogues around assessment so as to critically examine the assessment design.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In a traditional classroom, what follows assessment is mainly the teacher’s feedback in the form of numerical/alphabetical grades, written comments, or a combination of both. In this sense, feedback is regarded as instruction that is

customized after the teacher diagnoses the performance of the learner. To date, many studies have discussed problems with common feedback practices (Evans, 2013; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Orsmond & Merry, 2013; Vardi, 2013). Large-scale surveys (e.g. ACER, 2009; McDowell et al., 2008) also indicated that students are dissatisfied with feedback, often saying it is illegible, incomprehensible, or hard to understand. On the other hand, teachers complain that learners do not read or act upon feedback. Sadler (2010) explained quite clearly why this is the case. First, there is generally a big divide between the teacher experts’ and the novice learners’

background knowledge on the subject matter. This disparity comes from the teacher’s, and the students’ lack thereof, decades of professional training, and it makes teacher feedback inherently opaque to learners. To worsen the matter, the delivery of feedback is debilitated by all the flaws in how it is communicated. With an underline, a question mark, or a few truncated scribbles squeezed on the limited marginal space of learner assignments, the intended message is most likely to fail.

Many researchers have proposed ways to make teacher feedback more effective. Hattie and Timperley (2007), based on their systematic review of feedback studies, offered a comprehensive model of feedback aimed at enhancing learning. First, they state the purpose of learning as “to reduce discrepancies between current

understanding/performance and a desired goal,” thus highlighting the critical role of assessment. In order to reduce that discrepancy, students and teachers can take different approaches. For students, they may either increase efforts and employ more effective strategies or abandon, blur, and lower the goals. For teachers, they may provide appropriate, challenging and specific goals and assist students to reach the goals through effective learning strategies and feedback. In addition, Hattie and Timperley (2007) define effective feedbacks as those that can answer three questions for learners: Where am I going? How am I going? and Where to next? These three aspects of feedback were labeled as Feed Up to the goal, Feed Back to existing performance, and Feed Forward to the immediate next steps that the learner can take. Furthermore, they classify feedback as working at four levels: 1) the task level on how well tasks are understood/performed, 2) the process level on the main process needed

to understand/perform tasks, 3) the self-regulation level on learners’ self-monitoring, directing, and regulating of actions, and 4) the self level on personal evaluation and affect about the learner.

While Hattie and Timperley’s model addresses the cognitive side of feedback quite extensively, there are other non-cognitive aspects to feedback that should be scrutinized in order for feedback to work. Yang and Carless (2013) propose a feedback triangle incorporating, in addition to cognition, the affective and structural dimensions of feedback.

The affective dimension concerns interpersonal interaction, learner identify, and social expectations on the role of learners. Useful feedback messages, if delivered without care, may bring negative emotions to the learner, and hence failing to take the learner to the next stage. Therefore the teacher as a feedback provider needs to be sensitive and empathetic, providing affective as well as cognitive support to learners.

As for the structural dimension, it is an area that has received comparatively very little attention to date. The structure of feedback involves the macro societal and institutional arrangement. Included in this dimension are contextual constraints, such as heavy administrative or research workloads on teachers that take time away from providing detailed feedback, or large class sizes that dilute quality attention given to individual learners. More micro aspects in the structural dimension relate to the management of feedback, such as the sequencing of assessment events and feedback within the various subtopics in a course (such as assessments spreading out at two versus five time intervals), the timing of feedback provision (such as immediate or delayed), the channel chosen to convey feedback (such as written or oral), and the multiple stages of an assignment and the associated opportunities for improving quality after feedback was provided. The three dimensions of feedback do not each function in a vacuum; they inevitably influence one another and have to be

aggregately taken into consideration when assessment and feedback are designed. The abovementioned literature deals with assessment and feedback at a

conceptual level, yet of equal importance are thoughts about carrying out assessments at a pragmatic level. A range of approaches have been discussed on what tools and strategies can be used to enhance the quality of assessment and feedback. Bloxham and Campbell (2010) designed interactive cover sheets attached to assignments so that both the teacher and learners can, in addition to direct marginal notes, give holistic explanations and comments on a particular piece of work. They asked learners to specify the questions related to the task that they wanted answers for when submitting homework. This informed the tutors on what comments may be more relevant to learner needs and directed tutor attention in a more focused manner. It was reported that tutors’ workload was not increased and learner satisfaction was enhanced.

However, it was pointed out that some learners seemed to be unable to ask good questions.

In an ideal assessment situation, learners would be given multiple opportunities to fix work once constructive comments are received. But in reality, there may not be such luxury of time because teachers usually need to move on to other topics in the syllabus. Vardi (2013) suggests that, even when a series of tasks cover different topics, there should be some coherence of standards among them, so that learners will be able to apply things learned in the previous task to the next one. In the same vein, Kicken, Brand-Gruwel, van Merrienboer, and Slot (2009) recommended using development portfolios, in which learners will be able to examine progress from one task to another, thus forming a holistic view of their learning.

In addition to feedback tools and strategies, the feedback content itself can vary depending on how independent or autonomous learners are. Engin (2012) proposed a framework of five scaffolding levels. They are, from the more open guidance to the more closed directives – general open questions, specific wh-questions, closed yes/no questions, slot-fill prompts, and direct telling. It was suggested that “The trainer has to be sensitive to such a difference and change and make their choices of scaffolding contingent on the response of the trainee” (p. 18).

Another important aspect of quality assessment and feedback is about the roles of stakeholders in the classroom. Black and Wiliam (2009) expound on two

dimensions in their formative assessment theory. One dimension, as has been discussed, relates to the stages of learning, i.e. where learners are, where they are going, and how to get there. The other dimension concerns major stakeholders, including the teacher, peers, and the learners. In their theory, the teacher models assessments of current performance, learning objectives, and ways to bridge the gap. Such competence is then to be practiced by learners through classroom interactions with peers, such as peer review activities. In the end, it is hoped that scaffolds from the teacher and peers would be gradually removed and individual learners are able to pick up the ability to perform and self-assess for the purpose of learning on their own.

For a consolidation of these kinds of assessment feedback guidelines, Evans’ (2013) list of principles serves as a checklist. She reviews 267 relevant feedback articles from five large research data bases and concludes with six principles of effective assessment feedback practice. These principles are: (a) Feedback is ongoing and an integral part of assessment; (b) Assessment feedback guidance is explicit; (c) Greater emphasis is placed on feed-forward compared to feedback activities; (d) Students are engaged in and with the process; (e) The technicalities of feedback are attended to in order to support learning; and (f) Training in assessment

further been explicated as twelve pragmatic actions that may guide classroom teachers, including 1) ensuring an appropriate range and choice of assessment opportunities throughout a program of study; 2) ensuring guidance about assessment is integrated into all teaching sessions; 3) ensuring all resources are available to students from the start of a program to enable students to take responsibility for organizing their own learning; 4) clarifying with students how all elements of assessment fit together and why they are relevant and valuable; 5) providing explicit guidance to students on the requirements of assessment; 6) clarifying with students the different forms and sources of feedback available; 7) ensuring early opportunities for students to

undertake assessment and obtain feedback; 8) clarifying the role of the student in the feedback process as an active participant and not as purely receiver of feedback and with sufficient knowledge to engage in feedback; 9) providing opportunities for students to work with assessment criteria and to work with examples of good work; 10) giving clear and focused feedback on how students can improve their work including signposting the most important areas to address; 11) ensuring support is in place to help students develop self-assessment skills including training in peer feedback possibilities; and 12) ensuring training opportunities for staff to enhance shared understanding of assessment requirements.

In sum, all these plausible assessment and feedback principles and guidelines are inspiring, but they need to be consolidated in the real life of classrooms. Whether or not they make learning more effective is also subject to careful examinations. To this end, the purpose of the current study was twofold: a) to report an assessment and feedback design that involved learners in the continuous feedback dialogues with the teacher in a tertiary EFL writing course, and b) to examine the resulted learning by rating learner essays and analyzing the teacher-learner dialogues .

THE ASSESSMENT AND FEEDBACK DESIGN

The context for this assessment design is a two-credit elective language skill course offered at a university in northern Taiwan -- College English III: Essay Writing. Students who have completed or waived the required four-skill integrated College

English I and College English II are eligible to choose from a variety of about twenty

different topics in the College English III course family. The course reported here lasted for eighteen weeks and met two hours once every week. Twenty students were enrolled, with one freshman, three sophomores, seven juniors, and nine seniors. Their majors ranged from philosophy, finance, public administration, land economics, accounting, and business administration, to mass communication, Korean, French, and mathematics.

This writing course covered four essay genres: exposition, comparison and contrast, cause-effect, and argumentation. Great Writing 4: Great Essays, 3rd edition (Folse, Muchmore-Vokoun, & Solomon, 2010) published by Heinle Cengage Learning, was used as the main text. Students wrote a draft essay under an assigned topic after each genre was taught. As the course progressed, the draft was then reviewed and learners took it home for further revision. All revised essays were commented and scored by the instructor or the teaching assistant (TA).

The instructor was the author of this paper with seventeen years of experience teaching EFL at the college level in Taiwan. A part-time TA was recruited to assist her. This TA was at that time a graduate student from the Linguistics Institute of the same university with a bachelor’s degree in English from a teacher-training university. The instructor trained the TA by giving him three pre-course tutorials, based on feedback principles derived from relevant literature as reported above and regular weekly discussions once the course started. In the following sections, the assessment design will be explicated in the sequence of assessing the current performance of learners, helping learners understand learning objectives, and approaches to bridge the gap between the two.

Assessing the Learners’ Current Performance Level

At the inception of the course, three arrangements were made to help learners understand where they were in essay writing. First, in the first class meeting after the syllabus was briefly introduced, students were asked to write an essay on an assigned topic for thirty minutes. This experience brought them right on task and impressed them with how they performed. Secondly, criteria and standards were explicitly taught in the second class meeting. In order to make the criteria more relevant to learners, rubrics and essay samples were drawn from standard examinations that these students were familiar with, including the college entrance exams and General English

Proficiency Test. Finally, after learning about the criteria, learners were asked to mark several essay samples. Once students had completed reading and rating one sample, the instructor asked for a show of hands and summarized the resulted rating in a table on the blackboard, so it was apparent how judgments among students converged and diverged. Three pieces of message were conveyed through this exercise: 1) Slight variation is normal; 2) Even with slight variation, there are still clear standards; and 3) Learners can judge the quality of essays for which they are yet to master. A prototype of this part of design has been reported in Huang (2012).

Helping Learners Understand the Learning Objective through Multiple Samples The learning objectives were exemplified with sample essays from numerous

sources. First, they come from the textbook. Similar to the core of traditional instruction, these essays were introduced and explained in lectures and discussions, with special emphasis on analyzing essay structures and the linguistic elements. Another source of models came from their TA as a near-peer role model. Each time after learners submitted their essays, the TA wrote a piece with the same prompt. This piece was later shown to students when their essays were returned with feedback. In addition, the TA was asked to take learners behind the scene by explaining to them how he went about brainstorming, planning, drafting and revising his essays. Learners got to know what more experienced writers do and started to imitate very soon. A third source of samples came from learners themselves. After each round of feedback provision, good learner essays were selected and presented on the course Moodle platform. They were also highlighted in class by the instructor on areas done

especially well and those that could be further improved. Together with instructional content in the texts, sample essays from these three sources were used to feed up (Hattie & Timperley, 2007), that is to constantly communicate to students the learning objectives with concrete evidence.

Repeated Cycles of Learning, Performing and Formative Assessments

After learners were prepared by learning to assess their current performance and understanding the learning objective, instructions on ways to improve essay writing were conducted mainly in three channels: lectures, individual feedback comments, and elaborated briefing of patterns in student writing after each round of feedback stipulation. For lectures, its emphasis and specificity was influenced by learners’ demonstrated performance. The second access was of course the written feedback for each assignment, which will be discussed in more details in the following subsections. Thirdly, to follow written comments, an immediate face-to-face briefing for the entire class was scheduled the week when assignments were returned, which provided a venue for teacher explanations and learner clarification requests.

Of particular prominence was the assessment and feedback design which systematically guided individual learners. The design objectives were to make sure that learners were allowed opportunities to understand feedback, to act upon feedback and improve previous work, to reflect on that learning experience, and to assess progress and monitor learning. To make this happen, special care was placed on the scheduling of assignment, the instruments used for teacher feedback and learner response, and the gradual transfer of responsibility from the teacher through peers to the learner him/herself.

Scheduling of performance, assessment, and feedback

Assignments included four required essays on assigned topics. As shown in Figure 1, each assigned-topic essay went over two stages – the drafting stage, in which learners wrote by hand within limited time in class, and the revising stage, in which learners followed comments (from teacher/TA, peers, or self) to revise the draft and formally word-processed the essay for the final submission.

The first draft of these four, as mentioned above, was written on the first day of class and served a “getting-to-know-where-learners-are” purpose. It was not returned for revision until two weeks later in Week 3 after the basic essay structure and a few model essays had been introduced. The other three assignment drafts were each scheduled after a new genre had been taught, respectively in weeks 7, 10, and 14. Learners were given one week’s time for each of the four revisions, and all revisions were returned with teacher comments in the following week.

In-class Feedback by (no scores)

Out-of-class Feedback by (two scores) Draft 1 Teacher/TA Revision 1 Teacher/TA Draft 2 Peers (peer review) Revision 2 Teacher/TA Draft 3 Peers (peer review) Revision 3 Teacher/TA Draft 4 Self (checklist) Revision 4 Teacher/TA Figure 1. Assessment and feedback arrangement for four assigned-topic essays.

For each teacher feedback provision round (once on Draft 1and four more times on Revisions 1, 2, 3, and 4), the instructor commented on half of the learner

assignments and passed them on as exemplars for the TA to work on the other half. They then switch learner batches in the next round. All TA comments were reviewed and finalized by the instructor. There was no distinction made to students as for who provided them feedback comments. For the sake of convenience, hereafter all teacher/TA feedbacks are referred to as teacher feedbacks/comments. In addition to verbal comments, all revised essays were rated independently by both the instructor and the TA, so each learner received two numerical scores for each piece of revised work and the averages of the two were calculated into learner final grades. Learners were fully aware of such scoring arrangement. As the TA was not blind to the instructor’s scores, he may have been influenced to some extent. The inter-rater reliabilities for the four rounds were .93, .90, .94, and .91 respectively (p < .05 in all occasions).

Instruments that enabled teacher-learner dialogues on performance

Forms for pedagogical purposes were created and used (Appendix A, B, C, and D) to permit conscious learner reflection, so that teacher feedback could be responded to and a continuous flow of teacher-learner dialogues could be formulated around each individual student’s learning and performance. Learners were seen as playing a key role in driving their assessment and learning, and therefore should also contribute to the assessment feedback process (Boud & Molloy, 2012). This started with a

question asked by the learner when the first draft was submitted for teacher comments. When the first drafts were returned to students, in addition to marginal notes on the draft, an A4-size comment form was attached. Included in this form were columns on 1) strengths and the overall comments for the work, 2) specific suggestions for improvement, 3) two holistic numerical ratings given by the instructor and the TA, and 4) specific answers to the question that the learner previously raised (Appendix A). One more column at the bottom of the form asked the learner to write down thoughts after reading the feedback. The strengths and overall comment column furnished recognition, assurance, and affective support. The suggestions gave constructive directions that guided learners to move forward in the next task. The ratings on a scale of 1 to 15 (for details, see Huang, 2015; p. 26) were meant to secure a constant

objective measure throughout the semester among the four tasks, so learners could diachronically check their progress against this uniform standard. Synchronically, after completion of each of the four tasks, the class average with highs and lows were reported so that learners had an idea of where they stood in relation to their peers. There was also a purpose for the instructor and the TA to each rate learner work and supply two scores, rather than a single one. It showed that rater variance is part of this kind of evaluation, but such variance is within a small range. The two ratings were also expected to diminish the authoritative impression of teacher scores long established in these learners’ minds, so they could focus more on the comments.

When the revised versions were submitted, a revision report was required of the learners (Appendix B). This revision report asked each learner to summarize a) the comments they received and applied, b) additional resources consulted, c)

explanations for the revision including what was revised, why, and how, d) basic essay figures calculated using the Word readability function, and finally e) another question for the teacher. This report deliberately guided learners to assess and select received comments and metacognitively monitor their effort in improving the quality of previous work. Questions were followed up in the subsequent teacher feedback and made the teacher-learner dialogues along the stream of assignments more focused.

Other than the teacher feedback form and learner revision report, peer review guides (Appendix C) were used between the draft and revision stages in the second

and third essays. Peer review was removed for the fourth essay, and a checklist (Appendix D) was used instead for the learner author to independently evaluate and check the draft before revising. The rationale for sequentially using these different tools is discussed in the next subsection.

Gradual removal of scaffolding

As enunciated in formative assessment literature discussed above, good assessment capability should ultimately be acquired by the learner; it is not just the business of the instructor. To do this, the teacher has to model assessment and learning first. Learners then imitate what they observe to practice assessing and critiquing as peers. Eventually, the learner is expected to perform the assessment of his/her own performance independently, so learning could be sustained beyond the closure of formal instruction. With this concept in mind, this assessment design, as shown in Figure 1, started with the teacher modeling assessment for the first learner draft, in the hope that learners could understand the underlying rationale and imitate the thought processes. Starting from the second draft, peer reviews were conducted in class right after the drafts were completed. This was repeated one more time in the third task. Specific close- and open-ended questions serve as scaffolds in the peer review process. When it came to the final task, peer reviews were replaced by a checklist to be

examined independently.

The sequence of teacher model, two peer reviews, and self check along the four assignment tasks (Figure 1) was to scaffold more fully in the beginning and to gradually remove the scaffolds. This arrangement was also influenced by practical time constraints, as it was difficult to have more rounds in a semester.

RESULTS, ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Throughout the semester, students wrote four timed-essays in class. Each of these essays were reviewed and discussed following the aforementioned assessment design before learners brought them home to revise. For each submission of a revised essay, learners filled out a revision report (Appendix B). For each revised essay returned to learners, the teacher summarized comments in a feedback form (Appendix A). These essays and the associated written teacher-learner dialogues/exchanges around the essays were used as data for analysis. Moreover, individual interviews were conducted by the instructor/researcher at the end of the term, in which each participating student reflected on and discussed his/her learning experience by referring specifically to his/her essays and documents. Interviews were conducted in mostly Chinese and accompanied by English terms. They were transcribed verbatim.

Within the maximum number of twenty students enrolled, three dropped out in the middle of the semester for personal reasons and another fell seriously behind in assignment submission. After removing these four students’ data, sixteen sets of complete data from sixteen students remained for analysis.

Analysis of Learner Essays

Average readability indices of the four revised essays are shown in Table 1. As the figures demonstrated, the lengths of essays stretched from 350 words in the first time to 529 in the end. Total number of paragraphs and sentences, as well as number of sentences per paragraph and number of words per sentence all grew along the way. Table 1. Average Readability Indices of the Four Revised Essays

Readability Indices and Holistic Rating Essay 1 Essay 2 Essay 3 Essay 4

Number of Words 349.7 464.3 509.9 529.0

Number of Paragraphs 4.4 4.9 5.0 5.3

Number of Sentences 20.6 26.4 30.8 28.8

Number of Sentences per Paragraph 4.8 5.5 6.4 5.6 Number of Words per Sentence 17.3 17.2 16.6 18.3

Flash-Kincaid Grade Level* 9.2 9.2 8.7 9.6

Note: * The Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level presents a score as a U.S. grade level. It means the number of years of education generally required to understand the text.

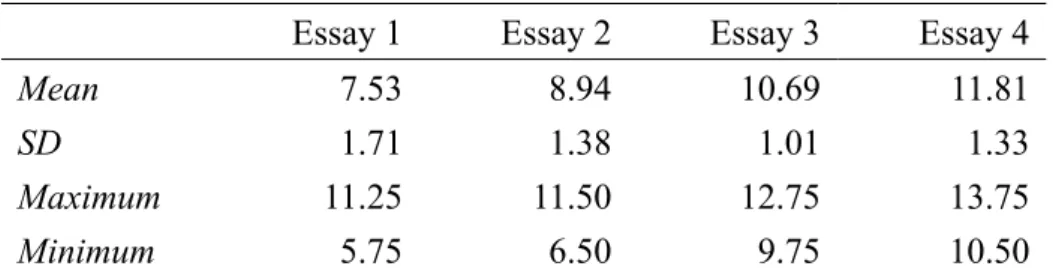

The quality of writing was rated by the author/instructor and the TA against a 15-point scale based on an instructional and grading rubric developed for the same learner population (Huang, 2015; p. 26) as the course progressed. To ensure reliability of data analysis, a research assistant was recruited after the conclusion of the course to independently rate all the essays using the same rubric. The inter-rater reliability between scores assigned by this outside rater and the average of the teacher/TA, as shown in Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, was .86. As shown in Table 2, the average holistic ratings went from the initial 7.53 in the first essay, gradually moving to 8.94 and 10.69 in the second and third essay, and eventually reached 11.81 for the fourth and final essay. By conducting a one-way within-subject ANOVA, significant difference was found among the four essays at the p < .05 level [F (3, 45) = 57.15, p = .000]. The strength of this relationship was relatively strong, with η2 = .774. Follow-up pariwise comparisons were conducted using Scheffe tests. Results indicated that differences between Essays 1 and 2, 1 and 3, 1 and 4, 2 and 3, 2 and 4, and 3 and 4 were all significant at the p < .05 level.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Average Essay Scores (n = 16) Essay 1 Essay 2 Essay 3 Essay 4

Mean 7.53 8.94 10.69 11.81

SD 1.71 1.38 1.01 1.33

Maximum 11.25 11.50 12.75 13.75

Minimum 5.75 6.50 9.75 10.50

Analysis of Teacher-learner Dialogues and Two Cases of Learner Development The second part of data analysis concerned student learning beyond the numbers revealed in essay ratings by examining specifically the teacher-learner dialogues made possible in the iterative formative assessments.

All feedback comments and interview transcripts were analyzed by the author researcher with help from a research assistant (not the course TA) after the course was completed using NVivo 10.0. The software allowed the two coders to check the consistency of categorization more easily. Coding were largely informed by Hattie and Timperley’s (2007) feedback framework, Evan’s (2013) feedback landscape, Yang and Carless’ (2013) feedback triangle, and Open University’s (2005) feedback

categories. The researcher first read through the entire data set two times. By clustering relevant meaning units and identifying patterns (Cohen & Manion 1994), the researcher deduced the initial coding categories. The research assistant was then instructed to code the data in the same way independently. When the first round of analysis was completed by both coders, discussions were carried out until all discrepancies were resolved. The researcher then read the coded data repeatedly to locate overlaps and connections. Through this recursive process, categories were progressively redefined (Kember & Ginns, 2012) and themes emerged. Finally, to exemplify findings, excerpts were purposefully chosen and translated when necessary.

Results of analysis were showcased in two learner cases. One case revealed the chronological development of a learner on the cognitive dimension and the other revealed that of another on the affective dimension. In discussing each of these two cases, excerpts were extracted from one single learner so that the entirety of learner development under this assessment design could be shown.

On the cognitive dimension

First of all, the iteration of performance and assessment discussions gave room for learners to revisit the same or similar issues again and again, therefore deepening their understanding and enhancing their performance level along the way. This revisit opportunity allowed learners to gradually acquire important writing skills or concepts which are easy to understand but difficult to master. Initial lectures raised the

awareness of the learner, but did not guarantee that the learner’s performance, even when carefully monitored, was on par with his/her knowledge. This pattern was evident in some learners but absent in others. More details are explained below using John’s (pseudonym) case.

In John’s four revision reports, he had shown a consistent concern on the

arrangement of ideas in his writing. This interest was exemplified in his questions to the teacher, his reports about revisions, and his reflection on the learning experience. When John submitted his first draft, he asked very succinctly:

(1) How could I remove irrelevant parts and make my essay more to the point?

In his first revision report, he mentioned that he took the teacher’s advice and rearranged the content and organization to make his points clearer.

(2) … Taking advices from the teacher, to emphasize the benefits, I took the original third paragraph apart, respectively demonstrating my points more precisely into the new third and fourth paragraphs. I also somehow enlarged the concluding paragraph, with main points of view remaining the same. Thoroughly, I corrected the mistakes, expanded the essay and fortified its structure by using topic, supporting and concluding sentences. …

In one of his reflections, he elaborated on the difficulties during the revising process, which were about the arrangement of content in different paragraphs. In the end, he reported that he came up with a solution. This reflection revealed the thought process he had been engaged in. It was this opportunity to reflect and explain that brought him to a higher level of understanding and performance in the issue of content and

structure.

(3) … The most difficult part was to distinguish the second and the fourth

paragraphs, for their contents were quite similar. Finally I decided to write the objective conditions in the second paragraph and the subjective feelings and behavior in the fourth. …

In his revision report for the third essay, John started to sound more like an experienced writer and began to use the disciplinary language he acquired in discussing his problems and strategies. His major concern still centered on how to arrange contents clearly into different paragraphs so the essay would be more logical. There was one part in his report that resembled the above excerpt, discussing how he rearranged the content so the argumentation became more logical.

In revising the fourth draft when teacher guidance and peer review had been taken away, John independently and quite assertively explained the problems he saw with his draft and the actions he took to improve it. His attention was still quite focused on the separation and flow of main ideas. Interestingly, one of his statements happened to be a ready answer to his beginning-of-term question in Excerpt (1) mentioned earlier.

(4) The content in the second and third paragraphs overlapped too much, so I deleted them. In addition, I moved the part on interpersonal relations from paragraph four to an earlier paragraph, and added one more paragraph to describe the relationship between campus activities and part-time jobs. Major revisions were on the second and third part of the body, i.e. the third and fourth paragraphs, because I wanted to control and present my ideas in a more logical manner.

Later in the interview, when asked what he had learned most, John pointed out very briefly on essay structure, with no hesitation. When asked to compare the writing experience in this course with his previous learning of writing, John again raised the issue of structure and logic.

(5) I used to write well and got good scores even before taking this course. But I did not have a clear essay structure concept. Now I care more about the arrangement of points – the what and where – in an essay. I think my writing becomes more logical.

John’s data, as well as some other learners’, showcased the chronological development of cognition and writing. John paid special attention on the better

separation and arrangement of ideas for the unity and logical progression of his essays. Such development was associated with learners’ early questions and reinforced

repeatedly by their own articulation and reasoning along the subsequent cycles of writing tasks. The teacher-learner dialogue opportunities permitted them to be consciously aware of and pay attention to the particular areas of interest. Such precious experience may be lost if assigned tasks were isolated or sporadic and learners were not constantly prompted to resolve and reflect on his/her problems. The formative assessment design in this study afforded learning to happen right in front of the learners’ eyes.

Another major finding on the cognitive dimension had to do with Hattie and Timperley’s (2007) notion of four feedback levels. As discussed above, they classify teacher feedback as at the four levels of task, process, self-regulation, and self. Of special importance to teachers is that the task-level comments are more directly related to the here and now of a task while process-level feedback could help learners generalize learning to other situations. They remind teachers not to just provide task-level feedbacks, but also process-level ones. When the data of teacher comments were analyzed, it was often hard to separate these two kinds of feedback and still keep the wholeness of the comment, because these feedback comments could hardly stand alone as either related only to task or only to process. The comment below for John is an example of this kind.

(6) You have done a very good job in presenting complicated ideas clearly. What you can do to improve your essay is summarized below (with reference to the marginal notes on your essay, although the comments there were more on the linguistic level).

a. Notes #6, # 8, and #10 sound more like a direct translation from the first language. Try to think in English and rewrite.

b. Notes #17, #19, and #20 are related to sentence structures. c. Notes #16 and #18 show you the parts that could be deleted. d. Note #15 has the purpose of making your essay more coherent.

As seen in the example cited above, feedback at the process level was supported by details from the task-level feedback, and feedback at the task level was explicitly summarized for its rationale and significance, which then became feedback at the process-level. If the comments were broken down into pieces and examined in

isolation, the learning they could trigger would probably be substantively diminished. This is a point worthy of attention and has probably not been highlighted in previous studies on assessment feedback.

On the affective dimension

Learners had their own personalities; this was perceptible in the tone of the descriptions and explanations in their reports. The teacher feedback reviewed seemed to be adjusting, maybe not quite consciously, to this learner disposition by either holding learners back or giving emotional support. For some learners who showed more confidence than their performance could justify, the teacher feedback used concrete examples to pinpoint areas not performed so well and require deliberate revisions. On the other hand, some learners showed much higher levels of insecurity about their proficiency and learning progress. They tended to criticize more than they had to. Judy (pseudonym) was one of them. A relatively hard-working student, Judy was never late for class, always submitted work on time, and wrote a lot more than her peers in her essays, revision reports, as well as review comments for her peers. But she seemed to be quite tough on herself at the beginning, pointing out problems all over the place without mentioning anything positive, as shown below when she was required to ask the teacher a question after her first draft.

(7) I made mistakes on my grammar. I have only very limited vocabulary. I have problem using new words I memorized. I don’t have good ideas, facts, or examples in my supporting sentences. My arguments are not complete, and my expression is flawed.

The same situation persisted when she explained her second revision, as shown in the following excerpt.

(8) … As I said above, I feel my essay is plain. Every time I write I don’t know how to describe the same thing or express the same thought in different ways. I run out of words quickly. And for the last paragraph, I don’t know how to make it better.

Faced with such harsh self-critics and nicely-prepared homework, the instructor drew on what Judy had done well and encouraged her, as illustrated below.

(9) You revised very carefully by consulting resources and spending time and effort. Please keep up the good work! Just because you wanted to try and express sophisticated ideas, problems with longer sentences became obvious, which was natural. This would remind you to review grammar and sentence structures learned before and improve more next time. Please compare your original with my revised sentences to see the difference and think about why. Remember to ask questions if there’s any place that remained unclear to you.

Judy’s earlier critiques were more general, judgmental, and self-oriented, but as her learning and the conversation with teacher evolved, she became more

problem-oriented and her descriptions carried more specificity. At times she could articulate the problems as well as her solutions quite clearly. However, even though she became more assertive, she still presented her thoughts in the form of questions, seemingly as a way to invite confirmation so she could be rest assured. Later in one peer review, she took her peer’s comments into serious consideration but in the end exercised her discretion and decided to reject some advice, with her own valid justification. In the third task, she had demonstrated a lot more confidence than in previous tasks as a learner writer.

(10) My peer suggested that I deleted the third sentence in third paragraph, because its meaning was similar to the following sentence. But I didn’t follow his suggestion, because there was a cause-effect relation between the two sentences and if I did what he told, that relation would be obscured.

What the instructor did was simply backing her up by confirming her reasoning and decision. In the later part of her third revision report, after describing her internal struggle and the rejection of peer opinions that she felt sorry about, she asked the teacher in a parenthesis – “Am I too stubborn?” She was reassured for what she did in the following piece of feedback comment.

(11) Writing is in nature a process of communicating with your readers. A lot of times we thought we expressed something but our readers did not get the intended message. At that point we should ask ourselves why we did not make ourselves understood. The best part of peer review, other than giving you suggestions, is that you get to communicate face-to-face and clarify your intentions, so you know why some messages failed to get across or what

caused the misunderstanding. The author possesses the ultimate right as for how he/she would express his/her ideas, as long as he/she knows the effect produced by his/her words.

Again, if there were no such repeated opportunities to discuss Judy’s essays and responded to her questions, the instructor would not have had known Judy’s insecurity well. And hence basic but important messages such as those in Except (11) would not have been highlighted to Judy.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This study achieved the two planned purposes – a) presenting a formative

assessment design in which the teacher’s written feedback was regularly responded to by learners, and b) examined the results of the design through ratings of learner essays and analysis of teacher-learner dialogues. As this was a study conducted in a naturalist setting for exploratory purposes, there were limitations in interpreting the results. First of all, the sample of sixteen learners was a relatively small size. In addition, patterns of cognitive and affective development as shown in the two learner cases were not evident in all. Why did some learners’ development appear to be more apparent and successful than others? What were the possible reasons behind the phenomenon? These questions warrant further studies. Secondly, there were no rigorous lab-like controls for variables and no comparisons made with a control group. Cautions are needed in generalizing results to other contexts. Thirdly, the commitment required of all stakeholders in this course was significant and may not be easily replicated when the class size is larger or participant involvement is at a lower level. For example, the time needed for the instructor to respond to one single essay in the manner

exemplified in this study was about one hour. The very competent TA also devoted lots of his time in working with the instructor. Such help may not always be available for every busy teacher. Learners, likewise, considered this course to be one of the most demanding in their learning experiences. The three dropouts and the one other student whose data were excluded were actually unable to manage the workload.

The study demonstrated an assessment design integrated in an EFL course with principles informed by recent research findings. As having been reported, assessment and feedback was deliberately integrated into the essay writing process in the hope that learners would learn to take more responsibility of their learning. Of special importance were the scheduling of assessment and feedback, the instruments that enabled the teacher-learner dialogues, and the arrangement for scaffolding to be gradually removed. Statistical analyses on the four batches of essays indicated that learners improved significantly from one task to the next in the four essays they wrote

during the semester, which suggested that the learning was effective. Furthermore, the examination of teacher-learner dialogues showed that there were focused discussions flowing from one assignment to the next, which provided an avenue for individual learners to deepen their learning and for the teacher to strengthen customized instructions. As revealed in the cases, some learners, when given this dialogue opportunity, were able to constantly revisit the subtlety of certain topics through practices and the reflection on those practices. They were informed, reassured, and directed by the instructor with concrete suggestions for the next steps and a higher level of preparedness for follow-up learning. The dialogues reinforced learning and empowered learners with a better sense of metacognition. Instead of the conventional one-way transmission, teachers’ feedback monologues could be turned into

bidirectional dialogues that involved learners. By engaging students and turning them from passive recipients of feedback to active feedback seekers and critical assessors, the co-constructed dialogues prepared them for independent learning in the future.

REFERENCES

ACER (Austrialian Council for Educational Research). (2009). Engaging students for

success: Australiasian student engagement report. ACER, Melbourne.

http://www.acer.edu.au/documents/AUSSE_ASERReportWebVersion.pdf (accessed October, 2014)

Alexander, R. (2008). Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. 4th ed. York, England: Dialogos.

Barker, M., & Pinard, M. (2014). Closing the feedback loop? Iterative feedback between tutor and student in coursework assessments. Assessment & Evaluation

in Higher Education, 39(8), 899-915.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment.

Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 21, 5-31.

Bloxham, S., & Campbell, L. (2010). Generating dialogue in assessment feedback: exploring the use of interactive cover sheets. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher

Education, 35(3), 291-300.

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2012). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698-712.

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education. London: Routledge. Davison, C., & Leung, C. (2009). Current issues in English language teacher-based

assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 43(3), 393-415.

Engin, M. (2012). Trainer talk: levels of intervention. ELT Journal, 67(1), 11-19. Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Review

of Educational Research, 83(1), 70-120.

Folse, K. S., Muchmore-Vokoun, A., & Solomon, E. V. (2010). Great Writing 4: Great

Essays (3rd ed.). Boston: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Graham, P. (2005). Classroom-based assessment: Changing knowledge and practice through preservice teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(6), 607-621.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational

Research, 77 (1), 81-112.

Huang, S.-C. (2012). Like a bell responding to a striker: Instruction continent on assessment. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 11(4), 99-119.

Huang, S.-C. (2015). Motivating revision by integrating feedback into revision instructions. English Teaching and Learning, 39(1), 1-28.

Kember, D., & Ginns, P. (2012). Evaluating teaching and learning: A practical

handbook for colleges, universities and the scholarship of teaching. London:

Kicken, W., Brand-Gruwel, S., van Merrienboer, J., & Slot, W. (2009). Design and evaluation of a development portfolio: how to improve students’ self-directed learning skills. Instructional Science, 37, 453-473.

McDowell, L., Smailes, J., Samball, K., Sambell, A., & Wakelin, D. (2008).

Evaluating assessment strategies through collaborative evidence-based practice: Can one tool fit all? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 45(2), 143-153.

McMillan, J. H. (Ed.). (2007). Formative classroom assessment: Theory into practice. New York: Teachers’ College Press, Columbia University.

McNamara, T. (2001). Language assessment as social practice: challenges for research. Language Testing, 18(4), 333-349.

Mercer, N. (1995). The guided construction of knowledge: Talk amongst teachers and

learners. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Mercer, N., Dawes, L., & Staarman, J. K. (2009). Dialogic teaching in the primary science classroom. Language and Education, 23(4), 353-369.

Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 501-517.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in

Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.

Open University. (2005). Codes for categorizing tutor feedback comments on

assignments. Accessed October 1, 2014.

www.open.ac.uk/fast/pdfs/feedback_codes.pdf

Orsmond, P., & Merry, S. (2013). The importance of self-assessment in students’ use of tutors’ feedback: a qualitative study of high and non-high achieving biology undergraduates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 737-753. Pryor, J., & Crossouard, B. (2008). A socio-cultural theorization of formative

assessment. Oxford Review of Education, 34(1), 1-20.

Rea-Dickins, P. (2006). Currents and eddies in the discourse of assessment: a learning-focused interpretation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics,

16(2), 163-188.

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535-550. Stiggins, R., & Chappuis, J. (2012). An introduction to student-involved assessment

FOR learning. 6th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Vardi, I. (2013). Effectively feeding forward from one written assessment task to the next. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(5), 599-610.

Yang, M., & Carless, D. (2013). The feedback triangle and the enhancement of dialogic feedback processes. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(3), 285-297.

APPENDIX

Appendix A. Teacher Feedback Form

Teacher Response to _________’s Revision of Timed Essay #1

Date: Overall

strengths

Areas that could be further improved Numerical ratings Answers to learner questions Learner’s own reflection on the first writing/revision cycle

Appendix B. Student Revision Report _______________’s Revised Version Date: Summary of comments I received from my peer that I decided to use Other resources I consulted (e.g. dictionary, Internet, TA, teacher, etc.) Explanation for revision

What was revised? Why I revised those parts? How I revised?

Potential areas for revision that I noticed

Essay figures and my own score for this work

___ words; ___ paragraphs; ___ sentences; ___ sentence per paragraph; ___ words per sentence; Flash-Kinkaid Grade Level ___; my self-evaluation ____ (1~15)

Questions for Teacher

Appendix C. A Peer Review Guide

Peer Review Form – The Second Completed Essay Draft Date:

Writer’s Name: Reviewer’s Name: Essay Title:

Your purpose in answering these questions is to provide an honest and helpful

response to your partner’s draft and to suggest ways to make his/her writing better. Be sure to read the entire paper carefully before writing any response. Be as specific as possible, referring to particular parts of the paper in your answers.

1. What do you like most about the paper? Choose the most interesting idea and explain why it captures your attention.

2. In your own words, state what you think the paper is about. 3. Identify the hook. Is it effective? Make suggestions here. 4. Write down the thesis statement. Is it stated or implied?

5. Does each body paragraph contain a clear topic sentence? If not, point out any areas that need improvement.

6. What method of organization does the writer use, block or point-by-point? 7. List the main points that the writer compares.

8. Are the comparisons supported with examples or details? Indicate clearly where you think improvement is needed.

9. Does the writer use connectors correctly? If not, circle any problematic connectors or any places that need connectors.

10. Does the writer restate the thesis in the conclusion? If not, bring this to the attention of the writer.

Appendix D. A Checklist

Timed Writing #4 Name: Date: Checklist (done well √; more work needed *; can’t tell?)

I. Response to Prompt/Assignment

_____ The paper responds clearly and completely to the specific instructions in the prompt or assignment.

_____ The essay stays clearly focused on the topic throughout. II. Content (Ideas)

_____ The essay has a clear thesis statement.

_____ The thesis is well supported with a few major points or arguments. _____ The supporting points are developed with ideas, facts, or examples. _____ The arguments or examples are clear and logical.

III. Organization

_____ There is a clear beginning (introduction), middle (body), and end (conclusion) to the essay.

_____ There is an effective hook.

_____ The beginning introduces the topic and clearly expresses the main idea. _____ The body paragraphs included topic sentences that are directly tied to the

main idea (thesis).

_____ Each body paragraph is well organized and includes a topic sentence, supporting details, and a summary of the ideas.

_____ Coherence devices (transitions, repetition, synonyms, pronoun reference, etc.) are used effectively within and between paragraphs.

_____ The conclusion ties the ideas in the body back to the thesis and summarizes why the issue is interesting or important.

IV. Language and Mechanics

_____ The paper is proofread and free from spelling errors.

_____ The paper does not have serious and frequent errors in grammar or punctuation.