Anlin Chen*

Department of Business Management National Sun Yat-Sen University

Kaohsiung 804, TAIWAN Phone: +886-7-5252000 ext. 4656 Fax: +886-7-5254698 Email: anlin@mail.nsysu.edu.tw Lanfeng Kao Department of Finance National University of Kaohsiung

Kaohsiung 811, TAIWAN Phone: +886-7-5919502 Fax: +886-7-5919329 Email: lanfeng@nuk.edu.tw Yi-Kai Chen Department of Finance National University of Kaohsiung

Kaohsiung 811, TAIWAN Phone: +886-7-5919501

Fax: +886-7-5919329 Email: chen@nuk.edu.tw

Keywords: Agency costs; Controlling shareholder; Moral hazard; Share Collateral

* We would like to thank the seminar participants at National Sun Yat-Sen University and National University of Kaohsiung for their helpful comments and suggestions. All the remaining errors are our own responsibility.

Abstract

Controlling shareholders’ share collateral is a new source of the deviation of cash

flow rights and control rights leading to minority shareholder expropriation.

However, controlling shareholders’ share collateral is not forbidden and has not

received particular restriction leading to its popularity in the capital markets.

Neglecting the potential agency costs resulting from controlling shareholders’ share

collateral would hurt the interests of creditors and minority shareholders. We need

legal regulation on controlling shareholders’ share collateral to reinforce corporate

Introduction

In the modern corporation structure, the ownership and control of corporations

are separated. Under the separation of ownership and control, Jensen and Meckling

(1976) argue that in a well-diversified corporation, the managers of the corporation,

who simply own partial ownership of the corporation, may consume more perquisites

and engage in activities that favor themselves rather than the shareholders. Jensen

and Meckling refer to this as the agency problem between the managers and the

shareholders.

Traditional agency theory is prevalent in a well-diversified economy. However,

La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer (1999) examine corporate ownership around

the world and indicate that except in economies with very good shareholders

protection such as the U.S., few firms are well-diversified. Rather, these firms

outside U.S. are typically controlled by families. The controlling families can

monitor the managers for their own benefits and thus also protect the interest of the

minority shareholders from being expropriated by managers.1 That is, the

controlling shareholders or controlling families reduce the agency problems between

managers and shareholders. In this case, the ethical problems related to managers’

bad attitudes toward the shareholders are alleviated. Nevertheless, Shleifer and

Shleifer, and Vishny (2000) argue that even though managers’ bad attitudes toward

shareholders can be alleviated by the presence of controlling families, the minority

shareholders are subject to the expropriation from the “controlling shareholders”

instead. Minority shareholders are expropriated by controlling shareholders rather

than by managers. The deviation of cash flow rights and control rights can lead to

the controlling shareholders’ expropriation on the minority shareholders. That is,

controlling shareholders’ ethical problems arise from the deviation of controlling

shareholders’ cash flow rights and their control rights. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes,

and Shleifer (1999) suggest that the expropriation on the minority shareholders from

the controlling shareholders should be emphasized and deserves investors’ attention.

How come the controlling shareholders’ cash flow rights deviate from their

control rights? Shelifer and Vishny (1997), La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shelfer

(1999), Bebchuk, Kraakman, and Triantis (2000), and Claessens, Djankov, Fan, and

Lang (2002) point out that the controlling shareholders accumulate their control rights

through pyramids, cross-holding, and dual class equity. In a pyramid of two

companies, a controlling minority shareholder holds a controlling stake in a holding

company that, in turn, holds a controlling stake in an operating company. In contrast

to pyramids, companies in a cross-holding structure are linked by horizontal

Dual class equity means that a firm has issued two or more classes of stocks with

differential voting rights. Bebchuk, Kraakman, and Triantis argue that dual class

equity is the only form of deviation of cash flow rights and control rights that does not

depend on the creation of multiple firms. In this paper, we raise another source of

the deviation of cash flow rights and control rights, which does not depend on the

creation of multiple firms and does not receive legal regulation. The new source of

deviation of cash flow rights and control rights deteriorates the expropriation of

controlling shareholders on the minority shareholders and deserves the attention of

government and investors.

What is the new source of the deviation of cash flow rights and control rights?

We argue that the controlling shareholders’ collateralizing shares as collateral is a new

source of the deviation and is popularly used in the real world. Controlling

shareholders’ share collateral does not depend on the creation of multiple firms, either.

Knowing the potential damage from controlling shareholders’ share collateral can

help establish a solid business ethical standard and protect the minority shareholders’

interest. Controlling shareholders’ share collateral is that the controlling

shareholders pledge their shares as collateral from financial institutions for funding.

It is pretty common for shareholders, either controlling shareholders or minority

Share collateral is popular and there are no particular regulations or restrictions on

shareholders’ share collateral, especially the voting rights of the collateralized shares.

In this paper, we would like to raise attention on controlling shareholders’ share

collateral since it really influences the controlling shareholders’ attitudes toward the

minority shareholders with Taiwan evidence. The reason why we use Taiwan

evidence is because Taiwan SEC requires the disclosure of controlling shareholders’

share collateral and because the data of controlling shareholders’ share collateral is

available. The uniqueness of Taiwan data makes it possible to examine ethical

problems related to controlling shareholders’ share collateral.

The remaining of this paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we express

the share collateral scheme in capital markets. We discuss why shareholders pledge

their shares as collateral in section 3. Section 4 describes the deviation of cash flow

rights and control rights due to controlling shareholders’ share collateral. The

agency problems resulting from controlling shareholders’ share collateral are

investigated in section 5. We provide Taiwan evidence related to the effect of

controlling shareholders’ share collateral on firm performance in section 6. Finally,

section 7 concludes.

Share Collateral Mechanism

institutions. Typically, the publicly traded shares with high liquidity are preferred as

collateral to protect the lenders’ interest. Share collateral is popular as a kind of

margin trading in stock markets when the shareholders use the funding from share

collateral for further stock investments. Of course, the funding from share collateral

can be used for other purposes other than stock investments. To protect the lenders’

interest on the loans, the borrowers cannot borrow the full amount of the value of the

collateralized shares. For example, the shareholders may simply borrow up to a

certain percentage, say 60%, of the market value of the collateralized shares. Since

the stock prices fluctuate, the borrowers might be asked to pledge more shares to meet

the margin requirements when the collateralized shares drop in market value. If the

borrowers cannot provide more shares as collateral to meet the margin requirements,

the lenders may sell the collateralized shares at the capital markets and get their

money back.

Even though the stocks are collateralized to the lenders, the borrowers still own

the stocks unless the borrowers default on the loan. In other words, the shareholders

who pledge their shares for funding at the financial institutions still keep their rights

related to the shares such as the cash flow rights (cash dividends) and the control

rights (voting rights for board elections) once they do not default. Since the

controlling shareholders will not lose their control rights due to their share

collateralization. Brigham and Ehrhardt (2002, p.714) argue that “one would

normally expect the price of a stock to drop approximately the amount of the dividend

on the ex-dividend date.” Before the ex-dividend date, investors expect to receive

the announced dividend. However, after ex-dividend date, the investors would not

be able to receive the announced dividend. That is, even though the collateralizing

shareholders still nominally keep the cash flow rights of cash dividends, the cash

dividends will cause the ex-dividend stock price to drop leading to the decrease of the

market value of the collateralized shares, and consequently the collateralizing

shareholders may have to pledge more shares to meet the margin requirements.

Collateralizing shareholders can keep their control rights but not the cash flow rights

as they pledge their shares as collateral.

There are no securities acts or regulations governing the share collateralization

by minority shareholders in most of the countries. However, the securities acts or

regulations do not impose any restriction on controlling shareholders’ voting rights on

collateralized shares, either. We cannot find any regulation to ban the controlling

shareholders’ share collateral in U.S or in other major countries. The only thing we

find is that controlling shareholders’ share collateral might need to be disclosed. For

share collateral in the prospectus when a firm wants to raise funds through public

offerings. Apparently with respect to the controlling shareholders’ share collateral,

Taiwan Securities Acts protect new fund providers but not existing fund providers.

To sum up, to borrow money by collateralizing shares as collateral from financial

institutions is easy for both the controlling shareholders and the minority shareholders

once they have agreements with the financial institutions.

Why Shareholders Pledge Shares as Collateral

Shareholders can pledge their shares as collateral for funding easily from the

capital markets. Why the shareholders pledge their shares for funding? For

minority shareholders who are not interested in the control over the firms, they pledge

their shares for funding for liquidity preference or for margin trading. Publicly

traded stocks can be liquidated easily, and therefore the lenders prefer them as

collateral for loan. Hence, shareholders who have demands on liquidity and still

want to keep their shares can pledge their shares as collateral at financial institutions

for money. Margin trading means that the investors raise loans to buy stocks.

Margin trading gives the stock investors greater buying power and financial flexibility

to boost their investment potentials. Investors who believe that they can make

money on certain stocks can easily make even more by margin trading. Certainly,

In this paper, we focus on controlling shareholders’ share collateral. Basically,

besides the purposes of liquidity preference and margin trading, the controlling

shareholders would probably pledge their shares for funding to finance the firms’

projects or to gain more control rights over the firms by buying more shares. When

firms cannot finance their projects due to lack of funds, their controlling shareholders

might pledge their shares as collateral for funding to finance the firms’ projects.

However, The Commercial Times (October 7, 2000) and Kao, Chiou, and Chen (2004)

indicate that the controlling shareholders’ share collateral in Taiwan is not related to

the story of firms’ lack of funds. The Commercial Times argues that the controlling

shareholders typically pledge their shares as collateral to buy more shares of the same

companies to gain more control rights over the firms in a self-financing cycle. The

purposes of shareholders’ share collateral can be summarized as liquidity preference,

investment by margin trading, financing firms’ projects, and control rights over the

firms.

Effects of Share Collateral on the Deviation of Cash Flow Rights and Control

Rights

Cash Flow Rights

As we mentioned, even though the borrowers pledge their shares at financial

shareholder lists and keep their related rights of the shares unless they default.

Therefore, controlling shareholders who pledge their shares as collateral would not

lose their “nominal” ownership of the firms. However, since the shares are

collateralized as collateral, the value of the collateralized shares is used to protect the

lenders’ interest from default. Hence, the “real” ownership (the cash flow right) of

the collateralizing shareholders decreases. We set up several cases to explain how

share collateral affects the cash flow rights and control rights of the controlling

shareholders.

Case A: There are two shareholders, X and Y. Both X and Y own 10 shares of

the firm, which are individually 10% of the total number of outstanding shares.

Suppose X pledges all his shares as collateral for personal liquidity use, but Y does

not. Nominally, both X and Y own 10 shares of the firms. Now the firm pays $1

dividend per share. The stock is normally expected to drop by the amount of

dividend on the ex-dividend date. Therefore, the ex-dividend stock price drops by

$1. Obviously, both X and Y will receive $10 as dividend payment from the firm.

However, the $10 received by X should be used to protect the value of the

collateralized shares because the value of collateral falls by $10. Typically, X will

be asked to pledge more shares. Therefore, the dividends received by X should be

collateralized. Once the ex-dividend stock price drops, X’s cash flow right on the

firm’s dividend payment is less than $10. On the other hand, Y can have his $10

dividend for any use and his cash flow right on the dividend payment is $10. Hence,

the cash flow rights of X on the firm are smaller than those of Y even though X and Y

have the same quantity of the shares of the firms. Shareholder X loses his cash flow

rights due to his share collateral.

Case B: Both X and Y own 10 shares of the firm. X pledges all his shares as

collateral and buys 10 more shares of the same firm (suppose no margin is required

for share collateral). Now the firm pays $1 dividend per share and the ex-dividend

stock price drops by $1 leading to the value of collateralized shares decreasing by $10.

Since X owns 20 shares of the firm, he will receive $20 dividend payment from the

firm. However, $10 out of the $20 dividend should be used as collateral to protect

the lenders’ interest. Even though X currently owns nominally 20 shares of the firm,

his cash flow right on the dividend is still $10, which is the same as that of Y who

simply owns 10 shares of the firm.

Case C: Both X and Y own 10 shares of the firm. X pledges all his shares as

collateral and buys 6 more shares of the same firm (suppose the margin requirement

restricts X to buy only 6 more shares from his collateral of 10 shares). Now X owns

share and the ex-dividend stock price drops by $1 leading to the value of

collateralized share decreasing by $10. Even though X receives $16 dividends, $10

of the dividend should be used to protect the value of the collateral. Finally, X

receives $6 cash flow without any restriction from the dividend payment. That is,

X’s cash flow right decreases when X pledges his shares as collateral.

Since shareholder Y does not pledge his shares, he always keeps his original cash

flow rights on the firm. However, shareholder X pledges his shares and loses his

cash flow rights. The more shares of the firm shareholder X buys from his share

collateral, the more cash flow rights he keeps over the firm.

Control Rights

The ex-dividend stock price will drop so at least part of the cash dividends from

the collateralized share should be used to protect the value of the collateralized shares

for lenders’ interest. That is the reason why that the shareholders will lose at least

part of their cash flow rights once they pledge their shares as collateral for funding.

Even though the shareholders pledge their shares as collateral, they are still the

nominal owners of the firms and have the full rights to vote for board elections, i.e.

they still keep their voting rights (or the control rights) over the firms. So far, there

is no restriction on the voting rights of the collateralized shares in U.S., Singapore or

control rights of the firm on case A, B, and C, respectively. For all the cases,

shareholder Y always keeps 10% of the control rights of the firm. Minority

shareholders gain on the liquidity preference or investment benefits from share

collateral at the costs of losing cash flow rights over the firm. On the other hand, the

controlling shareholders gain on keeping control rights from share collateral at the

costs of losing cash flow rights. Share collateral causes a change in cash flow rights

and control rights over the firm.

Agency Problems on Controlling Shareholders’ Share Collateral

Share collateral will separate control rights from cash flow rights. Bebchuk,

Kraakman, and Triantis (2000) point out that the separation of control from cash flow

rights creates agency costs and hurts the interests of minority shareholders. They

argue that under the separation of control from cash flow rights, the controlling

shareholders may hold a small fraction of the cash flow rights of the firm leading to a

sharp increase of the agency costs. The controlling shareholders may select the

projects that provide private benefits of control available only to themselves.

Similar to Jensen’s (1986) argument on agency cost of free cash flow, Bebchuk,

Kraakman, and Triantis (2000) indicate that controlling shareholders tend to extract

private benefits from unprofitable projects to expand firm scope. Controlling

of minority shareholders’ benefits. Since controlling shareholders’ share collateral

will deviate their cash flow rights and control rights, all the agency costs proposed by

Bebchuk, Kraakman, and Triantis (2000) apply directly when controlling shareholders

pledge their shares as collateral.

Besides agency costs, controlling shareholders’ share collateralization also raises

moral hazard problems. The risk preference of controlling shareholders who

pledge their shares at financial institutions diverges from that of minority shareholders

or creditors. After collateralizing shares, the controlling shareholders bear little risk

from the operations of the firms. The controlling shareholders can simply walk

away and leave the lenders with worthless shares once the firms collapse or are in

financial distress. In this paper, we further investigate some other ethical problems

toward outside investors and creditors regarding to controlling shareholders’ share

collateral. The real problem of controlling shareholders’ share collateralization is

that the risk preference they have with respect to cash flow changes.

In this section, we examine the ethical problems associated with controlling

shareholders’ share collateral in three contexts: earnings management, direct stock

manipulation, and risky project investments.

Earnings Management

application of generally accepted accounting principles.” Perry and Williams (1994),

Friedlan (1994), Erickson and Wang (1999), and Toeh, Welch, and Wong (1998)

indicate that managers engage in earnings management in order to mislead the stock

markets. Typically, if the reported financial statements reveal high earnings power

of the firms, the stock prices normally reflect positively to the reported earnings.

Why do the controlling shareholders engage in earnings management when they

pledge their shares as collateral? When shareholders pledge their shares as collateral

at financial institutions, they can only raise up to a certain fraction of the market value

of the collateralized shares. As we mentioned earlier, the publicly traded stocks are

preferred as collateral due to the liquidity property. Since the collateralized stocks

are publicly traded at exchanges, the stock prices normally fluctuate. When the

stock price goes up, the value of the collateralized share increases and the

collateralizing shareholders can borrow more money from the financial institutions

with their initial collateral. On the other hand, when the stock price goes down, the

value of the collateralized shares decreases and the collateralizing shareholders will

be asked to pledge more shares as collateral. Faced with the changeable stock price,

controlling shareholders who pledge their shares as collateral encounter further

pressure on the falling price. Once the controlling shareholders pledge their shares

price drop and have an incentive to engage in earnings management to fool the stock

markets and other shareholders.

Once the controlling shareholders engage in earnings management, the reported

financial statements become less credible. Kao and Chiou (2002) show that the

relation between accounting information and stock return becomes weaker when the

controlling shareholders pledge their shares as collateral implying that accounting

information is less credible in the capital markets.

Earnings management will distort the information of the financial statements and

thus the financial statement will become less relevant to the capital suppliers

including the shareholders and the creditors. It is unethical for firms not to reveal

their true information to their capital suppliers.

Direct Stock Price Manipulation

Shareholders who pledge shares as collateral are very sensitive to the price

movement of the stock, especially when the shareholders accumulate their shares by

using the funds from share collateral to buy more shares of the same firms. In a

bullish market, this stock accumulation causes the price to rise further and increases

the shareholders’ profit. On the other hand, in a bear market this share accumulation

causes margin calls and substantial losses. For a minority shareholder who pledges

price when he is required to meet the margin requirements of his share collateral.

However, controlling shareholders who control the firm have control over the

resources of the firm. Once the controlling shareholders need to meet the margin

requirements, they might have an incentive to utilize the firm’s resources to

manipulate the stock price directly to avoid their personal losses, especially for the

economies without proper governance mechanisms. Chiou, Hsiung, and Kao (2002)

indicate that during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, a lot of Taiwanese firms with their

controlling shareholders’ share collateral become financially distressed. They argue

that a major cause for the firms’ financial distress is that the cash flows of the firms

are mis-used to support the stock price during the market crash.

Choice of Risky Investment Projects

Brealey and Myers (2002) argue that due to the limited liability of the

shareholders in the corporation, the shareholders prefer the risky investment projects

at the expenses of the creditors. The shareholders can capture all the benefits from

the appreciation of the risky projects. However, shareholders only partially bear the

losses from the depreciation of the risky projects due to the limited liability. That is,

even though the payoff of the risky investment is symmetric, the payoff of the risk

investment to the shareholders is asymmetric. The payoff pattern of the controlling

financial institutions. When the controlling shareholders pledge their shares as

collateral, they can benefit from the stock appreciation leaving the financial

institutions bearing the risk of stock depreciation. If the controlling shareholders use

the loan from share collateral to buy shares of the same firm, then their payoff on the

risky projects becomes even more asymmetric. When the controlling shareholders

select the risky projects, the creditors cannot earn profits from the upside benefits of

the risky projects but bear the downside risk of the projects.

Controlling shareholders who use the loan proceeds to buy more stocks of the

same firms assume greater risk because more of their assets are tied up in the firm.

Hence, the controlling shareholders may be willing to take extreme risks to keep the

firm solvent. With extreme risk, the firm may either gain lots of cash or be in

distress. However, the controlling shareholders who pledge their shares can benefit

from gains of the risky projects and walk away leaving the creditors suffering losses

when the risky projects fail. On the other hand, the minority shareholders who do

not pledge shares do not have the creditors to bear the down side risk. The moral

hazard resulting from controlling shareholders’ share collateralization exposes the

minority shareholders to higher risk.

If controlling shareholders use loan proceeds for unrelated purposes, then they

risk with respect to the future cash flow of the firm. In other words, the

collateralizing shareholders bear lower risk than other minority shareholders and thus

have higher risk tolerance on the future fortunes of the firm. When the controlling

shareholders have higher risk tolerance, they may take risky investment projects and

expose minority shareholders to greater risk. The agency costs and moral hazard

resulting from controlling shareholders’ share collateralization create ethical problems

toward the minority shareholders.

The Relation between Firm Performance and Controlling Shareholders’ Share

Collateral

We argue that controlling shareholders’ share collateral raises agency cost and

moral hazard problems including earnings management, direct stock price

manipulation, and selection of risky investment projects. These ethical problems

will hurt firm performance and expose the firm to financial distress.

The effect of controlling shareholders’ share collateral on firm performance

depends on the use of the funding from share collateral. The funding from

controlling shareholders’ share collateral could be for personal use such as gaining

control or for corporate use such as financing firms’ projects. Basically, only when

corporate debt is not available or too expensive to use, the controlling shareholders

controlling shareholders finance the firms’ projects through their share collateral, the

controlling shareholders have to share the benefits from the projects with other

shareholders but bear the risk of the projects themselves. Hence, the use of funding

from controlling shareholders’ share collateral can be regarded as a positive signal to

the value of the firms’ projects leading to a higher firm performance. On the other

hand, it can also be a sign of desperation implying that the firm cannot raise corporate

debt for projects. However, if the funding from controlling shareholders’ share

collateral is for personal use instead of corporate use, the firms do not benefit from the

funding but suffer associated agency cost or moral hazard. Therefore, when the

funding of controlling shareholders’ share collateral is not for corporate use, the firm

performance should be poorer due to the severe ethical problems of agency costs and

moral hazard.

Anecdotal evidence (The Commercial Times, October 7, 2000) indicates that the

controlling shareholders in Taiwan pledge their shares as collateral to exaggerate their

control rights rather than to finance the firms’ projects. Therefore, we expect

controlling shareholders’ share collateral in Taiwan will be negatively related to firm

performance.

Sample and Variable Definition

controlling shareholders’ collateralized shares with the sample of listed firms in

Taiwan. The data on collateralized shares held by directors, ownership of directors,

debt ratio, R&D ratio, market value of equity, and stock returns are collected from the

Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database. Since TEJ began to report the proportion

of collateralized shares owned by directors in 1998, our sample period covers a 6-year

period of 1998-2003. Financial firms, utility firms, and state-owned firms are

deleted from the sample. Firms with missing data on controlling shareholders’ share

collateral or other variables are also discarded. Finally, our sample consists of 2766

firm-year observations.

Our variables are explicitly defined as follows.

1). RETM: market-adjusted annual stock return; RETM is used to measure firm

performance.

RETMit=Rit - Rmt,

Rit is the stock return of firm i at year t.

Rmt is the market return at year t. Market return is measured by the TSE (Taiwan

Stock Exchange) stock index which is a value-weighted market index.

2). COLLATERAL: percentage of shares that is held by directors of the firm and is

collateralized to financial institutions; COLLATERAL is used to measure controlling

COLLATERALit= directors by owned shares ns institutio financial at ized collateral directors by owned shares ,

COLLATERALit is the percentage of shares that is held by directors of the firm i

and is collateralized to financial institutions at the end of year t.

3). DEBT: debt-to-asset ratio,

DEBTit= it it assets Total s liabilitie Total ,

Total liabilitesit is the total liabilities of firm i at the end of year t.

Total assetsit is the total assets of firm i at the end of year t.

4) R&D: ratio of R&D expenses to net sales,

R&Dit= it it sales Net expenses D & R ,

R&D expensesit is the R&D expenses of firm i at year t.

Net salesit is the net sales of firm i at year t.

5) LogMV: the logarithm of market value of the firm’s outstanding shares. LogMV is

a proxy for firm size.

LogMVit=log(Pit×Number of shares outstandingit),

Pit is the stock price of firm i at the end of year t.

Number of share outstandingit is the number of shares outstanding of firm i at the

end of year t.

OWNERSHIPit= g outstandin shares of number directors by owned shares ,

7) INDUSTRY: industry dummy variable. INDUSTRY is 1 for electronic firms; 0

otherwise.

8) EM : the measurement of earnings management measured by absolute value of

abnormal accruals. Abnormal accruals are accruals that can be manipulated and is

typically used as the measure of earnings management. This paper applies absolute

values of abnormal accruals as a measure of earnings management. This measure is

suggested by Warfiled et al. (1995) and Bartov (2000). Accruals are the difference

between net income and cash flow from operations. Accruals consist of

discretionary and non-discretionary accruals. We use a modified Jones (1991) model

to estimate expected or nondiscretionary accruals for each two-digit industry code for

each year from 1998-2003. Abnormal or discretionary accruals are measured by

subtracting normal accruals from total accruals.3

Empirical Results

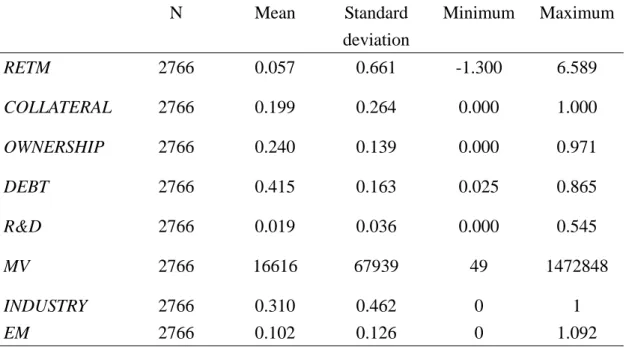

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics of the variables. On average,

market-adjusted annual stock return is 5.71%. 19.9% of shares owned by directors is

collateralized at financial institutions. Directors own 24% of the outstanding shares

sample is electronic firms. The earnings management level is about 0.102 on

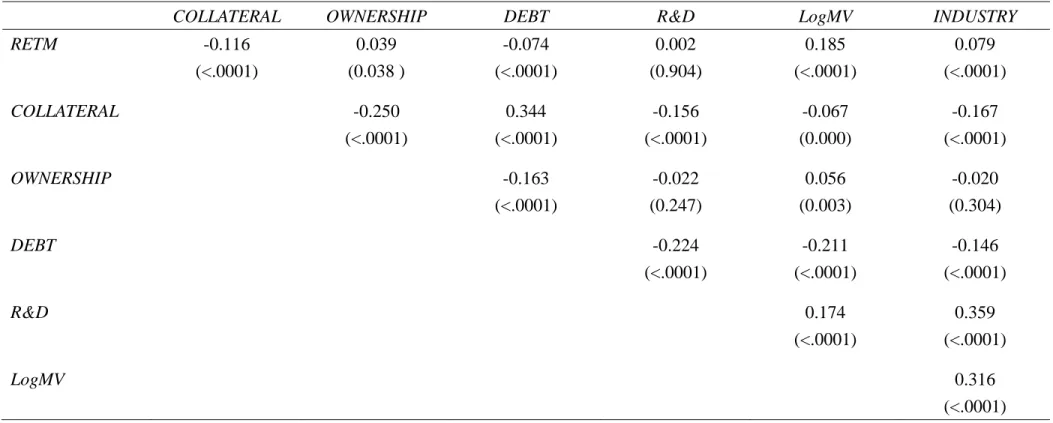

average. Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients among the variables and

indicates that the magnitudes of the correlation coefficients are all smaller than 0.359

(the correlation coefficient between INDUSTRY and R&D). The magnitudes of

correlation coefficients imply that our independent variables are not highly correlated

to cause multi-collinearity problem. We also apply VIF (variance inflation factor) to

examine the collinearity among independent variables in Table 3.

--- TABLES 1 2 3 about here ---

We employ the following regressions to investigate the relationship between firm

performance (earnings management) and controlling shareholders’ share collateral.

RETM = 0 + 1 COLLETERAL + 2 DEBT + 3 R&D + 4 logMV + 5 OWNERSHIP + 6 INDUSTRY + (1) EM = 0 + 1 COLLETERAL + 2 DEBT + 3 logMV + 4 OWNERSHIP

+ 5 INDUSTRY + (2) From the correlation coefficients in table 2, we know that our independent

variables are not highly correlated to one another. In table 3, we further investigate

the VIF of each independent variable in the regressions to see if collinearity problem

that there is no severe collinearity among the independent variables.

Table 3 reports our regression results between firm performance and controlling

shareholders’ share collateral. We use Newey-West (1987) test to adjust for

heteroscedasticity and autocorrelatoin. Table 3 shows that controlling shareholders’

share collateral is highly and negatively related to firm stock return with coefficient=

0.352 and Newey-West t-value= 3.659. Table 3 also indicates that controlling shareholders’ share collateral is significantly positively related to the level of earnings

management with coefficient and Newey-West t-value are 0.025 and 2.581,

respectively. With the data in Taiwan, the empirical results confirm our argument

that the controlling shareholders’ share collateral would raise ethical problems and

increase agency costs leading to poor firm performance.

Concluding Remarks and Suggestions

Shareholders can pledge their shares as collateral for funding from the capital

markets. Minority shareholders who have no control over the firms will bear all the

related risk and benefits from their share collateral themselves. On the other hand,

the controlling shareholders with their control power over the firm can earn benefits

from their share collateral and transfer the risk of share collateral to the creditors and

to the minority shareholders. However, controlling shareholders’ share collateral is

controlling shareholders on the minority shareholders and the ethical problems on the

creditors and minority shareholders due to controlling shareholders’ share collateral

should attract the attention of the government and all the participants of the capital

markets.

A major source for the ethical problems related to controlling shareholders’ share

collateral is the deviation of cash flow rights and control rights. To alleviate the

ethical problems, we can do at least two things: one is to reinforce the corporate

governance mechanism; the other is to reduce the deviation of the cash flow rights

and the control rights resulting from the controlling shareholders’ share collateral.

To reinforce the corporate governance mechanism, the controlling shareholders’ share

collateral should be monitored by the exchange and the related information should be

truthfully revealed to the public. To reduce the deviation of cash flow rights and

control rights associated with controlling shareholders’ share collateral, the voting

rights of the collateralized shares should be limited. We suggest that similar to

treasury stocks collateralized shares should not be honored with voting rights. When

a shareholder collateralizes his shares for funding, his voting rights of the

collateralized shares should be removed. That is, the controlling shareholders may

lose control over the firm when collateralizing shares. Once the controlling

shareholders. In this case, the controlling shareholders would not expropriate the

minority shareholders, but instead they would favor the minority shareholders.

Knowing the potential ethical problems of controlling shareholders’ share collateral

can protect the interest of the creditors and minority shareholders and thus facilitates

Footnotes

1

Controlling shareholders are shareholders able to control the composition of the

board of directors. Typically, controlling shareholders are also top managers. La

Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer (1999) define shareholders own at least 10% of

votes through a control chain as controlling shareholders. On the other hand, a

minority shareholder is exactly what it sounds like: an individual or organization who

holds shares in a corporation but does not control a majority of the votes. In

companies that are widely-held, a 10% shareholder can be a controlling shareholder.

However, in companies that are concentrated, a 10% shareholder can still be a

minority shareholder.

2

In fact, directors are not exactly the same as controlling shareholders. In Taiwan, it

is difficult to define the ultimate controlling shareholders due to complicate control

chain and token sharehodlers. Hence, we follow Kao, Chiou, and Chen (2004) to

use “director” as a proxy variable for “controlling shareholder”.

3

Since direct stock price manipulation is illegal and risky investment project is

difficult to observe, we simply test the relation between controlling shareholders’

References

Bebchuk, L., R. Kraakman, and G. Triantis. “Stock Pyramids, Cross-Ownership, and

Dual Class Equity: The Mechanisms and Agency Costs of Separating Control

from Cash Flow Rights.” Concentrated Corporate Ownership (R. Morck, ed.),

445-460, (2000).

Brealey, R. A. and S. C. Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance, 7th edition,

McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 2002.

Brigham, E. F. and M. C. Ehrhardt. Financial Management: Theory and Practice,

10th edition, South-Western Thomson Learning, Inc, 2002.

Chiou, J., D. Hsiung and L. Kao. “A Study on the Relationship between Financial

Distress and Collateralized Shares.” Taiwan Accounting Review 3 (1), 79-111,

(2002).

Claessens, S., S. Djankov, and L. Lang. “The Separation of Ownership and Control in

East Asia Corporations.” Journal of Financial Economics 58, 81-112, (2000).

Claessens, S., S. Djankov, J. Fan, and L. Lang. “Disentangling the Incentive and

Entrenchment Effects of Large Shareholders.” Journal of Finance 57 (6),

2741-2771, (2002).

Ericksnon, M. and S. Wang. “Earnings Management by Acquiring Firms in Stock for

Friedlan, J. “Accounting Choices of Issuers of Initial Public Offerings.”,

Contemporary Accounting Research 11, 1-31, (1994).

Jensen, M. and W. Meckling. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency

costs, and Ownership Structure.” Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305-360,

(1976).

Jensen, M. “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeover.”

American Economic Review 76, 323-329, (1986).

Kao, L. and J. Chiou. “The Effect of Collateralized Shares on Informativeness of

Accounting Earnings.” NTU Management Review 13, 1-36, (2002).

Kao, L., J. Chiou, and A. Chen. “The Agency Problems, Firm Performance and

Monitoring Mechanisms: The Evidence from Collateralized Shares in Taiwan.”

Corporate Governance: An International Review 12 (3), 389-402, (2004).

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. “Investor Protection and

Corporate Governance.” Journal of Financial Economics 58, 3-27, (2000).

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer. “Corporate Ownership around the

World.” Journal of Finance 54, 471-517, (1999).

Newey, W. D. and K. D. West. “A Simple, Positive Semi-Definite Heteroscedasticity

and Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix.” Econometrica 55, 703-708,

Perry, S. E. and T. H. Williams. “Earnings Management Preceding Management

Buyout Offers.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 18 (2), 157-179, (1994).

Shleifer, A. and R. Vishny. “A Survey of Corporate Governance.” Journal of Finance

52, 117-142, (1997).

Teoh, S., I. Welch, and T. Wong. “Earnings Management and the Underperformance

of Seasoned Equity Offerings.” Journal of Financial Economics 50, 63-99,

TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for stock performance, controlling shareholders’ share collateral, and other firm characteristics of firms listed in Taiwan over the period of 1998-2003. N Mean Standard deviation Minimum Maximum RETM 2766 0.057 0.661 -1.300 6.589 COLLATERAL 2766 0.199 0.264 0.000 1.000 OWNERSHIP 2766 0.240 0.139 0.000 0.971 DEBT 2766 0.415 0.163 0.025 0.865 R&D 2766 0.019 0.036 0.000 0.545 MV 2766 16616 67939 49 1472848 INDUSTRY 2766 0.310 0.462 0 1 EM 2766 0.102 0.126 0 1.092

RETM: market-adjusted annual stock return.

COLLATERAL: percentage of shares that is held by directors of the firm and is collateralized to

financial institutions. The minimum ownership of controlling shareholders equals to 0 because some directors, for example independent directors, do not own any shares of the firms.

DEBT: debt-to-asset ratio.

R&D: ratio of R&D expenses to net sales.

MV: the market value of the firm’s outstanding shares. Unit: in million NT dollars. OWNERSHIP: percentage of shares owned by directors.

TABLE 2 Correlation analyses

Correlation coefficients among stock performance, controlling shareholders’ share collateral, and other firm characteristics of firms listed in Taiwan over the period of 1998-2003. P-values are reported in the parentheses.

COLLATERAL OWNERSHIP DEBT R&D LogMV INDUSTRY

RETM -0.116 (<.0001) 0.039 (0.038 ) -0.074 (<.0001) 0.002 (0.904) 0.185 (<.0001) 0.079 (<.0001) COLLATERAL -0.250 (<.0001) 0.344 (<.0001) -0.156 (<.0001) -0.067 (0.000) -0.167 (<.0001) OWNERSHIP -0.163 (<.0001) -0.022 (0.247) 0.056 (0.003) -0.020 (0.304) DEBT -0.224 (<.0001) -0.211 (<.0001) -0.146 (<.0001) R&D 0.174 (<.0001) 0.359 (<.0001) LogMV 0.316 (<.0001)

TABLE 2 continued

RETM: market-adjusted annual stock return.

COLLATERAL: percentage of shares that is held by directors of the firm and is collateralized to financial institutions. DEBT: debt-to-asset ratio.

R&D: ratio of R&D expenses to net sales.

MV: the market value of the firm’s outstanding shares. Unit: in million NT dollars. OWNERSHIP: percentage of shares owned by directors.

TABLE 3

Regression analyses between firm performance (earnings management) and controlling shareholders’ share collateral

The relation between stock performance (earnings management) and controlling shareholders’ share collateral conditioning on other firm characteristics. In the parentheses are Newey-West t-values are calculated using Newey-West test.

Dependent variable: RETM Dependent variable: EM Variance Inflation Factor Intercept -0.525 (-4.192) 0.089 (1.606) 0.000 COLLATERAL -0.352 (-3.659) 0.225 (2.581) 1.217 DEBT -0.106 (-0.906) 0.109 (9.056) 1.221 R&D -1.564 (-2.549) 1.198 LogMV 0.241 (6.191) -0.009 (-3.451) 1.153 OWNERSHIP 0.065 (0.633) 0.031 (3.782) 1.086 INDUSTRY 0.169 (1.356) 0.050 (12.198) 1.263 N 2766 2766 R2 4.78% 8.96% Pr>F <0.0001 <0.0001

RETM: market-adjusted annual stock return.

EM: the absolute value of abnormal accrual as measure of earnings management.

COLLATERAL: percentage of shares that is held by directors of the firm and is collateralized to

financial institutions.

DEBT: debt-to-asset ratio.

R&D: ratio of R&D expenses to net sales.

MV: the market value of the firm’s outstanding shares. Unit: in million NT dollars. OWNERSHIP: percentage of shares owned by directors.