http://pmj.sagepub.com

Palliative Medicine

DOI: 10.1177/0269216307087142 2008; 22; 626 Palliat Med

SY Cheng, WY Hu, WJ Liu, CA Yao, CY Chen and TY Chiu

Good death study of elderly patients with terminal cancer in Taiwan

http://pmj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/22/5/626

The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:

Palliative Medicine

Additional services and information for

http://pmj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts: http://pmj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions: http://pmj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/22/5/626 Citations

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV LIB on August 18, 2009 http://pmj.sagepub.com

Good death study of elderly patients

with terminal cancer in Taiwan

SY Cheng Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, WY Hu School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, WJ Liu, CA Yao, CY Chen and TY Chiu Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei

Objectives: Over half of all terminal cancer patients in Taiwan are 65 or older, thus demonstrating the importance of terminal care for elderly people. This study investi-gates the good death status of elderly patients with terminal cancer, comparing the differences in the degree of good death among elderly and younger groups, and exploring the factors related to the good death score. Methods: Three hundred and sixty-six patients with terminal cancer admitted to a palliative care unit were enrolled. Two structured measurements, the good death scale and the audit scale for good death services, were used as the instruments in the study. Results: The scores of indi-vidual items and of the good death scale were increased significantly in both elderly (n = 206, 56.3%) and younger (n = 160, 43.7%) groups from the time of admission to just prior to death. However, the elderly group had significantly lower scores in ‘aware-ness’ (t = −3.76, P < 0.001), ‘propriety’ (t = −2.92, P < 0.01) and ‘timeliness’ (t = −2.91, P < 0.01) than the younger group prior to death. Furthermore, because of a lack of truth-telling, the elderly group also had significantly lower scores than the younger group in both ‘respect for autonomy’ and ‘decision-making participation’ (t = –2.17, P < 0.05; t = –2.21, P < 0.05, respectively). Multiple regression analysis revealed that ‘respect for autonomy’ (OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 0.76–1.67) and ‘verbal support ‘(OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.34–1.51) were two independent correlates of the good death score in the elderly group. Conclusion: The dilemma of truth-telling compromises the autonomy of the elderly patients with terminal cancer and consequently affects their good death scores. The palliative care team should emphasize the issue of truth-telling in the process of caring for terminally ill cancer patients, especially elderly patients. Palliative Medicine (2008); 22: 626–632

Key words: elderly; good death; palliative care; truth-telling

Introduction

Death is an inevitable for all humans, but what is meant by‘good death’? The words ‘good death’ imply the expec-tation that death is appropriately faced and managed by the relevant entities in society. Because the concept of good death varies across cultures, geography, religions and generations, it should not be seen as an absolute but rather one that varies with different cultures and evolves over time.1,2Many anthropologists, historians and sociol-ogists have tried to define good death. Counts and Counts observed that in Papua New Guinea, good death is meant to have a long and fulfilling life and a smooth dying pro-cess that occurs at home surrounded by family and community.3Anton and Van Hooff note that in Classical Greece and Rome, heroic death under self-control was

regarded as good death.4By contrast, in ancient Israel, good death meant a fulfillment of wills rather than heroic ideals.5

Long compared the concept of good death in high-income societies such as Japan and USA, and noted that the ability to control the timing and means of death are factors affecting good death in wealthy countries. How-ever, individualistic philosophy may not easily ‘carry over’ from an American to a Japanese context, where individualism is less valued. She also pointed out the inap-propriateness of futile treatments to prolong the life of patients, and emphasized the importance of medical per-sonnel in truth-telling and assistance in facing death.6In poor countries, such as Uganda, a good death is where the dying person is cared for at home, free from symptoms, feeling no stigma, at peace and has their basic needs met without feeling dependent on others.7Steinhauser, et al. conclude that good death encompasses six themes: pain and symptom controls, clear decision-making,

prepara-Correspondence to: Tai-Yuan Chiu, MD, MHSci, No. 7 Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan. Email: tychiu@ntuh.gov.tw

tions for death, completion, contributing to others and affirmation of the whole person.8

A qualitative good death study conducted in Japan, where the cultural background is very similar to Taiwan, found that the most frequently desired category of good death was‘freedom from pain or physical/psychological symptoms’ and the least desired category was ‘having faith’.9In 1988, Weisman defined good death as palliation of physical and psychological sufferings to the maximum extent and a passing away with dignity. The scope of good death should encompass awareness, acceptance, propriety and timeliness.10,11In summary, deaths that are reason-ably free of symptoms, in accordance with patient’s wishes and within acceptable ethical standards are consid-ered high-quality deaths.12

In Taiwan, more than half of terminally ill cancer patients are elderly. Older terminally ill cancer patients usually suffer from more severe symptoms, heightened deterioration in function, and more complications than younger patients.13,14The physical and mental conditions of these patients often leads to the close involvement of their families in medical decisions, compared with their younger counterparts or less severely ill patients. How-ever, the involvement of the family in decision-making can compromise the patients’ autonomy and interfere with the attainment of their good death.

Although the elderly are generally seen as having a higher degree of acceptance of the inevitability of death, and less fear of it, recently, this common belief has been questioned by Tsai, et al.15 In their Taiwan study, they demonstrate that the elderly actually display higher levels of fear of death than the young at two days before death. Similarly, a UK study comparing attitudes toward death, palliative treatment and hospice care revealed that older people do not believe that younger people deserved more consideration than older people when dying, or that they should have priority for hospice care.16The current liter-ature, then, demonstrates a difference regarding attitudes toward death between older and younger people. Further research is warranted regarding the interrelationships among age, good death, and services. To that end, this study investigates the good death status of elderly patients with terminal cancer, comparing the differences in the degree of good death among elderly and younger groups, and exploring the factors related to good death score.

Methods

Patients

The participants enrolled in the study include all patients with various terminal cancers admitted to the palliative care unit in National Taiwan University Hospital during the period from July 2004 through June 2005. Admitted patients were identified by admission committee members

comprised mainly of physicians and nurses, and put under active total care provided by a multidisciplinary team that included physicians, nurses, clinical psychologists, social workers, chaplains and volunteers. Patients were divided into two age groups,‘elderly’ and ‘younger’, with the cut-off point of 65 years according to the WHO definition of elderly. The study was approved both by the National Sci-ence Council in Taiwan and by the hospital ethics committee.

Instruments

An assessment form consisting of three parts was used for all of the subjects. On this form, we recorded demo-graphic characteristics, good death scale and audit scale for good death services. Reliability and validity of these two scales have been established in Taiwanese palliative care units.10,17–18Initially, a panel composed of two phy-sicians, two nurses, one psychologist, two chaplains, and one social worker tested the entire instrument for content validity. All members of the panel were experts in pallia-tive medicine. A content validity index was used to deter-mine the validity of the structured questionnaire and yielded a score of 0.93. In addition, 10 volunteers (bereaved family members) filled out the questionnaire to confirm the questionnaire’s face validity and ease of application.

Demographic data assessed by the questionnaire included gender, age, primary sites of tumor, duration of admission, place of death and survival times. Also included were the two scales:

Good death scale

An appropriate clinical quality-of-dying instrument must be derived from the perspectives of end-of-life care parti-cipants and include the multiple domains of experience important to patients and families.19 Thus, based on Weisman’s definition of a good death and the opinions of experienced professionals in palliative care, the assess-ment of good death in the study consists of five items, including awareness that one is dying (0 = complete igno-rance, 3 = complete awareness), accepting death peace-fully (0 = complete unacceptance, 3 = complete accep-tance), arranging one’s will (0 = no reference to the patient’s will, 1 = following the family’s will alone, 2 = following the patient’s will alone, 3 = following the will of both the patient and their family) , death timing (0 = no preparation, 1 = the family alone had prepared, 2 = the patient alone had prepared, 3 = both the patient and their family had prepared), and degree of physical comfort three days before death (0 = a lot of suffering, 1 = suffering, 2 = a little suffering, 3 = no suffering).

Following the death of each patient, a score ranging from 0 to 15 was recorded by the palliative care team to summarize the extent to which it was a good death.10The Good death of elderly cancer patients 627

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV LIB on August 18, 2009 http://pmj.sagepub.com

higher the total score, the better the good death status the patient had achieved. The opinion of each member was considered and the final score for each patient was decided jointly at the team meeting. Whenever there was a disagreement, it was resolved mainly according to the opinion of the primary care nurse. The good death scores of 366 patients were collected and analyzed. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency of this good-death measure in the study subjects and showed a coeffi-cient of 0.71 for the five items.

Audit scale for good death services

This good death service measure was designed with care-ful scrutiny of the available literature and was used to evaluate the performance of palliative care service based on three components including structure, process and out-come. The original scale was classified into six categories, each of which contains two items. Each item is appraised on a scale of 1 =‘extremely unsatisfied’ to 5 = ‘extremely satisfied’. The six categories and 12 items were as follows: (1) physical care: symptom control and satisfaction of the patient and the family; (2) autonomy: respect for auton-omy and decision-making participation; (3) emotional support: alleviation of anxiety and resolution of depres-sion; (4) communication: verbal support and non-verbal support; (5) continuity of life: continuity of social support and affirmation of one’s past life; and (6) closure: fulfill-ment of last wish and bereavefulfill-ment support.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BT) and Kaiser–Meyer– Olkin (KMO) test were used to confirm that the measure was appropriate for exploratory factor analysis (BT = 3373.56, KMO value = 0.871, P < 0.01). The draft items were analyzed using principal component fac-tor analysis followed by orthogonal varimax rotation. The number of principal components to be extracted was determined by examining the eigenvalues (> 1) and Cat-tell’s Scree test. The cutoff point of factor loading in the study was set at 0.5. Finally, the domains were recon-structed to two factors and named ‘patient care’ and ‘social well-being’. The internal consistency was demon-strated with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.84 to 0.91 in the factors and 0.93 for total items of this measure. These two factors accounted for 65.4% of the total variance of the variables. These tests indicate that both scales have an acceptable level of reliability and validity for this study sample.

Statistical analysis

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using SPSS V12.0 statistical software. A frequency distri-bution was used to describe the demographic data. Means and standard deviations were used to analyze the ‘good death and good death services’ scores. The independent t-test was utilized to compare the differences between

two age groups in terms of both scales. In addition, a paired t-test was used to compare the changes of the good death scale at the time points of ‘on admission’ and‘two days before death’. Univariate analysis, includ-ing the chi-square test, Fisher exact method, independent t-test, and Pearson correlation coefficient analysis, was performed between the possible correlates (demographic data, duration of admission, survival time, place of death, items of audit scale for good death services) and the scores of the good death scale to identify significant differences. Finally, backward step-wise multiple regression analysis was used to explore independent correlates of good death. A probability value less than 0.05 is considered sta-tistically significant in this study.

Results

The subjects of this study included 366 hospitalized patients with terminal cancers: 183 men and 183 women. The mean (SD) age was 65.00 (± 16.49) years. More than half of the 366 patients (56.3%) were older than 65 years and only three patients were younger than 18 years. With regard to the primary cancer origins, liver cancer patients comprised the largest group (19.7%), followed by lung cancer patients (19.4%), and gastrointestinal cancer patients (18.9%). Of the 366 patients, 288(78.7%) died at the hospital while 78 (21.3%) died at home (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of the men was 63.67 (± 16.70) years, whereas the mean (SD) age of the women was 66.33 (± 16.22) years. There was no statistical difference in age between male and female groups.

There were 160 subjects in the younger group (< 65 years old), of whom 89 were men (55.6%) and 71 were women (44.4%). Of the 206 patients in the elderly group (≥65 years old), 94 were men (45.6%) and 112 were women (54.4%). The mean (SD) duration of hospi-talization for the younger group (11.53 [±13.60] days) and for the elderly group (10.62 [±10.56] days) showed no sig-nificant difference. However, the survival time for the elderly group (35.96 [±38.90] days) was significantly lon-ger than that of the younlon-ger group (23.34 [±38.90] days) (P < 0.05).

Table 2 reveals a significant difference between the elderly group and the younger group for the average score of the item ‘awareness’ (1.99 vs. 2.16, P < 0.05) at admission. However, the elderly group had a higher aver-age score in the item of ‘comfort’ compared with the younger group (2.11 vs. 1.98, P < 0.05). There was no sig-nificant difference between the two groups for the rest of the items.

Table 3 indicates that there remains a significant differ-ence between the elderly and younger groups in the item of ‘awareness’ (2.61 vs. 2.83, P < 0.001) prior to death.

Regarding the items of ‘propriety’ and ‘timeliness’, the score of the younger group became significantly higher than the elderly group (2.88 vs. 2.68, P < 0.01; 2.89 vs. 2.72, P < 0.01). There was no statistical difference for the average scores between the two age groups in the items of ‘acceptance’ and ‘comfort’. However, the total score of the good death scale of the elderly group before death was lower significantly than that of the younger group (13.52 vs. 14.17, P < 0.01) before death. Using paired t-test to compare the scores of good death scale

on admission and before death, the scores of all items were increased in both groups, and the sum of all items of the good death scale both in the elderly and younger groups were elevated from 10.94 and 10.84 to 13.52 and 14.17 (P < 0.01, respectively). This demonstrates that total care of the palliative care team can promote the good death score of these terminally ill patients.

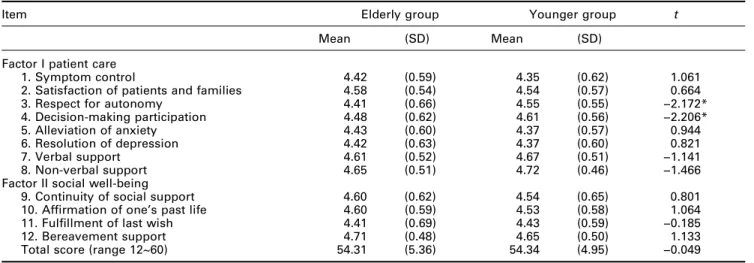

Concerning the audit scale for good death services, the exploratory factor analysis result was different from the original version. The sub-domains were reconstructed to two factors ‘patient care’ and ‘social well-being’. Items ‘continuity of social support’, ‘affirmation of one’s past life’, ‘fulfillment of last wish’, and ‘bereavement support’ had comparatively larger factor loadings on the social well-being domain (0.564 ~ 0.850) (Table 4). These results imply that items‘continuity of social support’, ‘affirma-tion of one’s past life’, ‘fulfillment of last wish’, and ‘bereavement support’ should be grouped under social well-being domain.

Table 5 showed that the average scale score was higher than 4 (range 1–5) irrespective of items, reflecting the high level of satisfaction in both patients and family toward the services in the hospice. However, in the category of ‘autonomy’, the elderly groups had significantly lower score than the non-elderly group (P < 0.01) including both items of ‘respect for autonomy’ and ‘decision-making participation’. There was a significant positive correlation among the scores of individual items and the sum of all items of good death scale and the good death services at the time before death (r = 0.15 ~ 0.51, P < 0.01).

The study also performed multiple regression analysis for the correlates of good death score in three groups including total patients, younger and elderly groups

Table 1 Demographic data of the 366 terminal cancer patients

Variable n %

Sex

Male 183 50.0

Female 183 50.0

Age (year) Mean (SD) = 65.00 ± 16.49

≤18 3 0.8

19~35 13 3.6

36~64 144 39.3

≥65 206 56.3

Primary sites of tumor

Liver 72 19.7

Lung 71 19.4

Gastrointestinal 69 18.9

Head and neck 43 11.7

Cervix and ovary 23 6.3

Breast 19 5.2 Pancreas 18 4.9 Hematology 10 2.7 Uncertain 8 2.2 Others 33 9.1 Place of death Hospital 288 78.7 Home 78 21.3

Duration of admission (days) Mean (SD) = 10.58 ± 12.59 Survival time (days)

after admission

Mean (SD) = 30.44 ± 63.52

Table 2 The scores of good death scale at admission between elderly group (n = 206) and younger group (n = 160)

Item Elderly group, mean (SD) Younger group, mean (SD) t

Awareness 1.99 (0.82) 2.16 (0.69) −2.188* Acceptance 2.13 (0.68) 2.04 (0.67) 1.234 Propriety 2.56 (0.81) 2.56 (0.84) −0.049 Timeliness 2.16 (1.01) 2.10 (1.05) 0.512 Comfort 2.11 (0.60) 1.98 (0.62) 2.119* Total score 10.94 (2.72) 10.84 (2.72) 0.342 *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Table 3 The scores of good death scale prior to death between elderly group (n = 206) and younger group (n = 160)

Item Elderly group, Mean (SD) Younger group, Mean (SD) t

Awareness 2.61 (0.67) 2.83 (0.41) −3.761*** Acceptance 2.68 (0.56) 2.78 (0.45) −1.806 Propriety 2.69 (0.73) 2.88 (0.49) −2.923** Timeliness 2.72 (0.67) 2.89 (0.44) −2.909** Comfort 2.82 (0.41) 2.80 (0.46) 0.340 Total score 13.52 (2.14) 14.17 (1.55) −3.364** *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Good death of elderly cancer patients 629

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV LIB on August 18, 2009 http://pmj.sagepub.com

(Table 6). Of all the potential correlates of good death score in the elderly group, we found there was a signifi-cantly positive correlation between respect for autonomy and good death (odds ratio = 1.215, 95% confidence inter-val, CI = 0.758 ~ 1.672). In addition,‘verbal support’ was significantly correlated with good death (odds ratio = 0.928, 95% CI = 0.345 ~ 1.511) for the elderly patients. This model accounted for 27.9% (multiple R2) of the variance in the good death score.

Discussion

In general, elderly patients’ physical and mental condi-tions can compromise the state of autonomy, which may interfere with the achievement of good death. This issue previously has received little attention in the literature. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to investigate the effect of palliative care on, and the correlates of good death in, elderly patients with terminal cancer.

In this study, 56.3% of the patients were elderly, 39.3% of the patients were between 36–65 years old, only 4.4% of the patients were less than 35 years old. This compares to data from The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization in the USA, where a majority of patients undergoing palliative care were elderly with less than 1% younger than 17.14 This difference may be attributed to the demographic characteristics and the attitudes toward palliative care in the two countries. The average length of hospitalization in our study was 10.58 ± 12.59 days, con-siderably shorter than the 29 days in the US data in 1999. This may be ascribed to the fact that many patients in Taiwan were very terminal when they were admitted to the hospice, often well into the active dying process. The phenomenon of late referral implies that palliative care needs to be further promoted in Taiwan at earlier stages. Moreover, when the medical conditions of the patients stabilize, they are often discharged and referred into home care system, and readmitted to hospice only when medical condition deteriorates, thus contributing to the shorter average length of hospitalization in Taiwan.

Concerning the good death scale, the patients in the elderly group scored lower on the item of ‘awareness’ than the patients in younger group both at admission and prior to death, which subsequently results in lower scores in‘propriety’ and ‘timeliness’. A higher proportion of the elderly patients with terminal cancer are not fully aware of their medical condition even before death because in Oriental culture, it is common practice not to disclose the truth of the illness, especially to a terminal cancer patient, on the basis of non-maleficence. This mutual pretence prevails because both sides are unwilling to hurt each other and lack knowledge of communicating with each other.

Table 4 Varimax rotated factor matrix for audit scale of good death services (n = 366)

Item Factor I Factor II

1. Symptom control 0.826

2. Satisfaction of patients and families 0.771 0.219

3. Respect for autonomy 0.615 0.448

4. Decision-making participation 0.630 0.473

5. Alleviation of anxiety 0.742 0.348

6. Resolution of depression 0.701 0.389

7. Verbal support 0.609 0.529

8. Non-verbal support 0.642 0.489

9. Continuity of social support 0.129 0.847 10. Affirmation of one’s past life 0.253 0.850

11. Fulfillment of last wish 0.354 0.708

12. Bereavement support 0.492 0.564

Table 5 The scores of audit scale for good death service between elderly group (n = 206) and younger group (n = 160)

Item Elderly group Younger group t

Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

Factor I patient care

1. Symptom control 4.42 (0.59) 4.35 (0.62) 1.061

2. Satisfaction of patients and families 4.58 (0.54) 4.54 (0.57) 0.664

3. Respect for autonomy 4.41 (0.66) 4.55 (0.55) −2.172*

4. Decision-making participation 4.48 (0.62) 4.61 (0.56) −2.206*

5. Alleviation of anxiety 4.43 (0.60) 4.37 (0.57) 0.944

6. Resolution of depression 4.42 (0.63) 4.37 (0.60) 0.821

7. Verbal support 4.61 (0.52) 4.67 (0.51) −1.141

8. Non-verbal support 4.65 (0.51) 4.72 (0.46) −1.466

Factor II social well-being

9. Continuity of social support 4.60 (0.62) 4.54 (0.65) 0.801

10. Affirmation of one’s past life 4.60 (0.59) 4.53 (0.58) 1.064

11. Fulfillment of last wish 4.41 (0.69) 4.43 (0.59) −0.185

12. Bereavement support 4.71 (0.48) 4.65 (0.50) 1.133

Total score (range 12~60) 54.31 (5.36) 54.34 (4.95) −0.049

Chiu, et al. found that this problem of truth-telling occurred in nearly half of the patients over age 65 in the hospice.20 They also found that the ethical dilemma of truth-telling could not be completely resolved until a patient’s death. However, a study conducted in Hong Kong suggests that truth-telling should depend on what the patient wants to know and is prepared to know, and not on what the family wants to disclose.21Therefore, it seems that there is considerable work to be done concern-ing truth-tellconcern-ing toward the elderly patients with terminal cancer. In this study there was no significant difference with regard to the items of ‘propriety’ and ‘timeliness’ between the two age groups at admission, however, patients in the elderly group scored significantly lower on those two items than the younger group prior to death. Cicirelli notes that many elderly take a fearful atti-tude toward death and are willing to prolong their life by any means, which might contribute further to their unpre-paredness toward death.22Again, the primary reason that the elderly could not well prepare for their death was that they were not fully aware of their imminent death.

In this study, the average scores of all categories in the audit scale of good death services were higher than 4 (range 1–5), demonstrating the high level of satisfaction toward the palliative care services. However, in the cate-gory of‘autonomy’, including the subscales of ‘respect for autonomy’ and ‘respect for decision-making participa-tion’, the average score of patients in elderly group were lower than their younger counterpart. This suggests the elderly are often absent in the process of decision-making, which could be attributed to the fact that many family members deliberately concealed the truth and, thus, medical decisions were made only by medical staff and family. The autonomy of the patient is therefore diminished and this affects their good death.

Multiple regression analysis revealed that ‘respect for autonomy’ and ‘verbal support’ from the palliative team members are the two most important predictors of good death for the elderly. The more respect the patient received regarding to medical decision-making and partic-ipation, the higher the score for good death. Likewise, the more encouragement the patient received from the hos-pice team, the higher the score for good death.

The process of truth-telling is a complicated, delicate and unfamiliar to the Oriental people. Clayton, et al. iden-tified themes of truth-telling including emphasizing what can be done, exploring realistic goals and discussing day-to-day living.23First of all, the care team has to be well prepared, with a thorough understanding of the illness, the patient and the family. The care team should know the extent to which the patient understands his or her own illness, choosing an appropriate timing in a quiet environment. The meeting is best conducted by someone the patient fully trusts and should proceed in a guiding, exploring and progressive manner. The care team should keep the principles of mutual trust, autonomy, confidenti-ality and no harm, listen carefully to the questions the patient raises and encourage the patient to release his or her emotions. It is important to let the patient know the future care plan, and assure him or her that the care team would never abandon and will accompany him or her until the end. Truth-telling has to be individualized, espe-cially to the elderly. The elderly sometimes have difficulty comprehending the meaning of cancer and therefore it is best not to emphasize the word‘cancer’ and let the patient realize that he or she is dying by using commonly under-stood language.

Certain caveats should be mentioned in relation to this study. First, proxy evaluation by the hospice care team was used. Surrogate observation is often used when direct

Table 6 Multiple regression analysis of factors independently correlated with good death score (n = 366)

Variable Coefficient Beta t-value 95% CI

1. Total patients (n = 366)

Respect for autonomy 0.783 0.251 4.505*** 0.441 ~ 1.125

Non-verbal support 0.669 0.170 2.855** 0.208 ~ 1.130

Age 0.000 −0.155 −3.463** −0.028 ~ −0.008

Alleviation of anxiety 0.500 0.152 2.603* 0.122 ~ 0.877

Continuity of social support 0.323 0.106 2.081* 0.018 ~ 0.629

Constant 4.665 NA 5.016*** 2.836 ~ 6.494

Multiple R value = 0.560; multiple R2= 0.304

2. Younger group (n = 160)

Non-verbal support 0.784 0.234 2.803** 0.231 ~ 1.336

Alleviation of anxiety 0.687 0.252 3.258** 0.270 ~ 1.104

Continuity of social support 0.532 0.225 2.879** 0.167 ~ 0.898

Constant 5.045 NA 4.609*** 2.883 ~ 7.207

Multiple R value = 0.572; multiple R2= 0.315

3. Elderly group (n = 206)

Respect for autonomy 1.215 0.376 5.247*** 0.758 ~ 1.672

Verbal support 0.928 0.225 3.137** 0.345 ~ 1.511

Constant 3.883 NA 3.333** 1.586 ~ 6.181

Multiple R value = 0.535; multiple R2= 0.279

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Beta, normalized beta coefficient; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

Good death of elderly cancer patients 631

at NATIONAL TAIWAN UNIV LIB on August 18, 2009 http://pmj.sagepub.com

assessment by the patient is not available; however it might not be a very accurate index of the patient’s subjective feel-ing, thus limiting the interpretation of the results.17 Never-theless, the evaluation items were usually apparent in the opinions of health care workers, based on observation and mutual interactions in the process of care. Our previous study also showed the high concordance of the evaluation between hospice care team and families.17Additional qual-itative studies of dying patients in the actual circumstances are needed to elucidate this. Second, analysis as to whether the good death scale used here can elucidate the meaning of a good death within the Taiwan cultural context would be useful.

In conclusion, elderly patients with terminal cancer have significantly lower scores in subscales ‘awareness’, ‘acceptance’, and ‘propriety’ in the good death scale, and in‘autonomy’ in the audit scale, which was mainly related to lack of truth-telling. The dilemma of truth-telling com-promises the autonomy of elderly patients with terminal cancer and consequently affects their good death scores. The palliative care team should emphasize the issue of truth-telling in the process of caring for terminally ill can-cer patients, especially elderly patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the staff of the Hospice and Palliative Care Unit, National Taiwan University Hospi-tal, and also to Y. C. Chen and M. K. Hsieh for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

References

1 Emanuel, EJ, Emanuel, LL. The promise of a good death. Lancet 1998; 351(Suppl II): 21–29.

2 McNamara, B. Good enough death: autonomy and choice in Australian palliative care. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 929–938.

3 Counts, DA, Counts, D. The good, the bad, and the unresolved death in Kaliai. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 887– 897.

4 Anton, JL. Van Hooff. Ancient euthanasia:‘good death’ and the doctor in the graeco-Roman world. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 975–985.

5 Spronk, K. Good death and bad death in ancient Israel according to biblical lore. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 987–995. 6 Long, SO. Cultural scripts for a good death in Japan and the United States: similarities and differences. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 913–928.

7 Kikule, E. A good death in Uganda: survey of needs for palliative care for terminally ill people in urban areas. BMJ 2003; 327: 192–194.

8 Steinhauser, KE, Clipp, EC, McNeilly, M,

Christakis, NA, McIntyre, LM, Tulsky, JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and pro-viders. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 825–832.

9 Hirai, K, Miyashita, M, Morita, T, Sanjo, M, Uchitomi, Y. Good death in Japanese cancer care: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006; 31: 140–147.

10 Cheng, SY, Chiu, TY, Hu, WY, Guo, FR, Wang, Y, Chou, LL, et al. A pilot study of good death in terminal cancer patients [in Chinese]. Chin J Fam Med 1996; 6: 83– 92.

11 Weisman, AD. Appropriate death and the hospice pro-gram. Hospice J– Phys, Psychosoc Pastoral Care Dying 1988; 4: 65–77.

12 Patrick, DL, Curtis, JR, Engelberg, RA, Nielsen, E, McCown, E. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 410–415. 13 Hsu, HC, Hu, WY, Chuang, RB, Chiu, TY, Chen, CY.

Symptoms in the elderly with terminal cancer: A study in Taiwan [in Chinese]. Formosan J Med 2002; 6: 445–473. 14 Porzsolt, F, Zeeh, J, Platt, D. Palliative therapies in

elderly cancer patients. Drugs Aging 1995; 6: 192–209. 15 Tsai, JS, Wu, CH, Chiu, TY, Hu, WY, Chen, CY. Fear

of death and good death among the young and elderly with terminal cancers in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Man-age 2005; 29: 344–351.

16 Catt, S, Blanchard, M, Addington-Hall, J, Zis, M, Blizard, R, King, M. Older adults’ attitudes to death, pal-liative treatment and hospice care. Palliat Med 2005; 19:402–410.

17 Chiu, TY. Good Death of Terminal Cancer Patients: Report of National Science Council in Taiwan. Taipei: National Science Council in Taiwan, 2004.

18 Yao, CA, Hu, WY, Lai, YF, Cheng, SY, Chen, CY, Chiu, TY. Does dying at home influence the good death of terminal cancer patients? J Pain Symptom Manage 2007 (in press).

19 Steinhauser, KE, Clipp, EC, Tulsky, JA. Evolution in measuring the quality of dying. J Palliat Med 2002; 5: 407–414.

20 Chiu, TY, Hu, WY, Cheng, SY, Chen, CY. Ethical dilemmas in palliative care: a study in Taiwan. J Med Ethics 2000; 26: 353–357.

21 Tse, CY, Chong, A, Fok, SY. Breaking bad news: a Chi-nese perspective. Palliat Med 2003; 17: 339–343.

22 Cicirelli, VG. Elders’ end-of-life decisions: implications for hospice care. Hospice J – Phys Psychosoc Pastoral Care Dying 1997; 12: 57–72.

23 Clayton, JM, Butow, PN, Arnold, RM, Tattersall, MH. Fostering coping and nurturing hope when discussing the future with terminally ill cancer patients and their care-givers. Cancer 2005; 103: 1965–1975.