A U-shApe relAtionship wAs foUnd with re-gArd to sleep dUrAtion And oUtcome stUdies which showed thAt both short And long sleep durations were associated with the risk of all-cause death among caucasians,1-3 Japanese,4,5 and taiwanese.6 however, the association between sleep duration and cardiovascular disease (cVd) risk was inconsistent: a U-shape relationship was found among chinese in singapore7 and white women,8 but other studies only showed an inverse relationship.9 short sleep duration has been linked to increased obesity and weight gain,10-12 diabetes,13 and hypertension14,15; and this association has been attributed to the relationship between sleep dura-tion and all-cause death and cVd risk. however, the asso-ciation between long sleep duration and cVd risk remains unexplained.

ethnic difference for the risk of sleep duration and sleep quality, such as insomnia severity, has been reported. ethnic and geographic variation in self-reported sleep duration has

been noted.16,17 A nationwide survey of 32,749 adults aged 18 years or older in the United states showed that compared with caucasians, African Americans and other non-hispanics, in-cluding Asian Americans, were more likely to be short or long sleepers, and the relative risks ranged from 1.26 to 1.62.16 in a population-based survey of 3,158 adults, the prevalence of reduced habitual sleep time was higher in African Americans than caucasians (18.7% vs. 7.4%).17 however, African Ameri-cans were less likely to have sleep complaints among a cross-sectional study based on 13,563 adults aged 47 to 69 years.18 evidence regarding the prevalence and the risk of sleep dura-tion among ethnic chinese is relatively rare.6,19

furthermore, the issues on association between sleep dura-tion and the risk of all-cause death and cVd events need to be clarified. First, it unclear whether the association between sleep duration and cVd risk is still persistent after multi-variate adjustment. previous studies included only limited covariates in an adjusted model. second, potential effect mod-ification between sleep and the risks by age and gender has been reported.20 third, insomnia severity was associated with cVd outcomes,21-23 but its role with regards to all-cause death is still unknown. therefore, we hypothesized that reduced or prolonged sleep duration and frequent insomnia predisposed individuals to increased risk of all-cause deaths and cardio-vascular events. we tested this hypothesis using a large pro-spective cohort of middle-aged to older chinese adults in a community in taiwan.

habitual sleep duration, insomnia and health risk

Habitual Sleep Duration and Insomnia and the Risk of Cardiovascular Events

and All-cause Death: Report from a Community-Based Cohort

Kuo-Liong Chien, MD, PhD1,2; Pei-Chung Chen, PhD3; Hsiu-Ching Hsu, PhD2; Ta-Chen Su, MD, PhD2; Fung-Chang Sung, PhD3; Ming-Fong Chen, MD, PhD2;

Yuan-Teh Lee, MD, PhD2,4

1Institute of Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University; 2Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan

University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; 3Institute of Environmental Health, College of Public Health, China Medical University, 4Institute of Clinical

Medical Science, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

study objectives: To investigate the relationship between sleep duration and insomnia severity and the risk of all-cause death and cardiovascular

disease (CVD) events

design: Prospective cohort study setting: Community-based

participants: A total of 3,430 adults aged 35 years or older intervention: None

measurements and results: During a median 15.9 year (interquartile range, 13.1 to 16.9) follow-up period, 420 cases developed cardiovascular

disease and 901 cases died. A U-shape association between sleep duration and all-cause death was found: the age and gender-adjusted relative risks (95% confidence interval [CI]) of all-cause death (with 7 h of daily sleep being considered for the reference group) for individuals reporting ≤ 5 h, 6 h, 8 h, and ≥ 9 h were 1.15 (0.91-1.45), 1.02 (0.85-1.25), 1.05 (0.88-1.27), and 1.43 (1.16-1.75); P for trend, 0.019. However, the relationship between sleep duration and risk of CVD were linear. The multivariate-adjusted relative risk (95% CI) for all-cause death (using individuals without insomnia) were 1.02 (0.86-1.20) for occasional insomnia, 1.15 (0.92-1.42) for frequent insomnia, and 1.70 (1.16-2.49) for nearly everyday insomnia (P for trend, 0.028). The multivariate adjusted relative risk (95% CI) was 2.53 (1.71-3.76) for all-cause death and 2.07 (1.11-3.85) for CVD rate in participants sleeping ≥9 h and for those with frequent insomnia.

Conclusions: Sleep duration and insomnia severity were associated with all-cause death and CVD events among ethnic Chinese in Taiwan. Our

data indicate that an optimal sleep duration (7-8 h) predicted fewer deaths.

keywords: Sleep, cohort study, cardiovascular disease

Citation: Chien K; Chen P; Hsu H; Su T; Sung F; Chen M; Lee Y. Habitual sleep duration and insomnia and the risk of cardiovascular events and

all-cause death: report from a community-based cohort. SLEEP 2010;33(2):XXX-XXX.

submitted for publication February, 2009 Submitted in final revised form September, 2009 accepted for publication september, 2009

Address correspondence to: Yuan-The Lee, MD, PhD, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, #7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan, 100; Tel: (886) 2-2356-2830; Fax: (886)-2-2392-0456; E-mail: ytlee@ntu.edu.tw

methods

study design and study population

participants in the chin-shan community cardiovascular cohort study who completed questionnaires about lifestyle and sleep in 1990-1991 were the population for this study. details of this cohort study have been published previously.24-28 Briefly, this study began in 1990 by recruiting 1,703 men and 1,899 women ≥ 35 y—a homogeneous group of Chinese ethnicity that was living in the chin-shan township 30 km north of metropol-itan taipei, taiwan. information about anthropometry, lifestyle, and medical conditions was assessed by interview question-naires in 2-y cycles, and the validity and reproducibility of the collected data and measurements have been reported in detail elsewhere.28 the national taiwan University hospital commit-tee review board approved the study protocol.

exposure measures

we measured sleep in 1990 with 2 self-reported variables: habitual sleep duration and insomnia severity. sleep duration was a variable with 5 categories (≤ 5, 6, 7, 8, and ≥ 9 h). The questionnaire for the frequency of insomnia complaints in the past one year were as follows: “how frequent is your insomnia complaint?” and the 4 response alternatives, including “no in-somnia,” “occasional insomnia (2-3 times each month),” “fre-quent insomnia (2-3 times each week),” and “insomnia nearly every day”, were chosen. participants were reminded that the definition of insomnia was complaints of difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or additional nonrefreshing sleep. biochemical and Clinical measures

the procedures for blood sample collection were reported elsewhere.29,30 Serum samples were then stored at −70°C before batch assay for levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (hdl-c). standard enzymatic tests for serum cholesterol and triglycerides were used (merck 14354 and 14366, germany, respectively). hdl-c levels were measured in supernatants after the precipitation of specimens with magnesium chloride phospho tungstate reagents (merck 14993). ldl-c concentrations were calculated as total choles-terol minus cholescholes-terol in the supernatant using the precipita-tion method (merck 14992).31

outcome ascertainment

Deaths were identified from official death certificates and further verified by house-to-house visits. Incident CVD includ-ed coronary heart disease and stroke cases. incident coronary heart disease cases (n = 174) were defined as nonfatal myocar-dial infarction, fatal coronary heart disease, and hospitalization due to percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary bypass surgery. incident stroke cases (n = 246) were ascertained ac-cording to the following criteria: a sudden neurological deficit of vascular origin that lasted longer than 24 h, with supporting evidence from the image study. The cases were confirmed by neurologists and internists.

statistical analysis

participants were categorized on the basis of sleep dura-tion and insomnia severity, and the continuous variables were

presented by mean and standard deviation, and AnoVA was used to test the difference across quartiles. incidence rates of all-cause death and cVd event were calculated by dividing the number of cases by the person-years of follow-up for each category of sleep duration and insomnia severity. the cox pro-portional hazards model was applied to estimate the relative risk and 95% confidence interval (CI) for sleep duration and insomnia status. All models were adjusted for age (in 10-y cat-egories) and gender. Additional baseline covariates for which simultaneously adjusted covariates included body mass index (< 18, 18-20.9, 21-22.9, 23-24.9, ≥ 25 kg/m2), smoking (yes/ no or abstinence), current alcohol drinking (regular/no), mari-tal status (single, married and living with spouse, or divorced and separated), education level (< 9 y, ≥ 9 y), occupation (no work, manual or office job), regular exercise (yes vs. no), and family history of coronary heart disease. the third model in-cluded covariates in the additional model plus clinical mea-sures, including baseline hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/ no), cholesterol, hdl, triglyceride, glucose, and uric acid level. the joint effects of sleep duration and insomnia severity were estimated in the multivariate cox models. here, insomnia was categorized as dichotomies, describing optimal (no or scanty) versus nonoptimal (frequently or nearly everyday insomnia), and the duration of sleep was grouped into 3 strata (≤ 6 h, 7-8 h, ≥ 9 h) in the jointed models. In addition, we examined the non-linear relationship between sleep duration and risk of all-cause death and cVd events with restricted cubic splines.32 we applied the SAS macro “%LGTPHCURV8”, to fit the restrict-ed cubic splines into the multivariate cox model to examine the possible non-linear relationship between sleep duration as well as insomnia and relative risks of all-cause death and cVd events. The output showed the significance level from the like-lihood ratio tests for non-linearity, and the plot for the multi-variate relative risk and confidence band was plotted.32 we also tested the goodness of fit for the model by using the Hosmer and lemeshow test,33 and the goodness-of-fit test was accept-able (p > 0.5). We conducted stratified analyses to evaluate a potential effect modification by baseline gender and age (65 years as cutoff) and found no significant interaction was found. performance measures, including area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), net reclassification improvement (nri) and integrated discrimination improvement (idi), were used to compare the models with and without sleep variables, described in supplementary methods.

All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with sAs version 9.1 (sAs institute, cary, nc) and stata version 9.1 (stata corporation, college station, texas). results

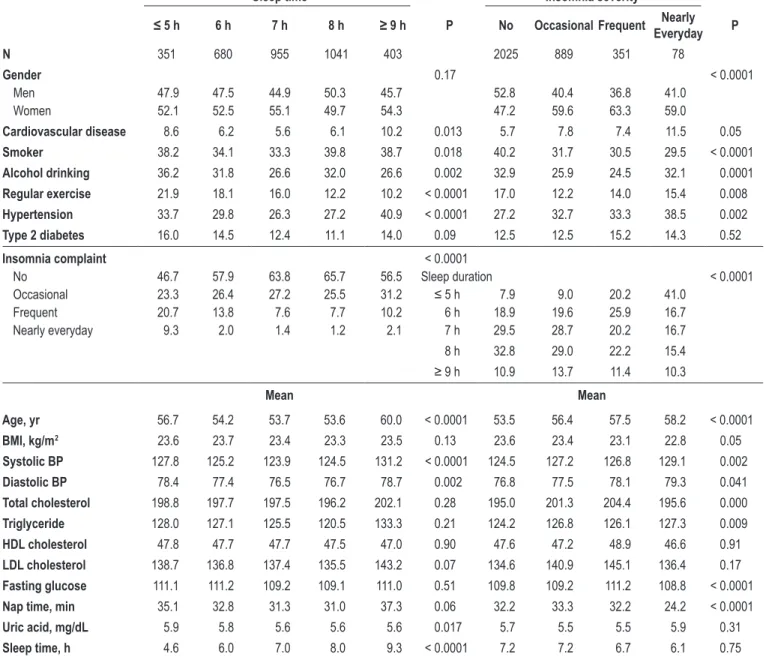

After excluding missing data on sleep (n = 172), 3,430 partic-ipants were included in this study. the baseline characteristics of clinical, lifestyle, socioeconomic, and biochemical measures are listed in table 1, according to sleep duration and insomnia severity. compared with those sleeping 7 or 8 h, participants sleeping ≤ 5 h and ≥ 9 h were more likely to be men, smokers, and alcohol drinkers. shorter and longer sleepers were older, having a longer nap time, and higher blood pressure and uric acid levels than those sleeping 7 or 8 h. compared with those

with no or occasional insomnia complaints, participants with frequent nearly daily insomnia were more likely to be women, have cardiovascular disease and hypertension history, and less likely to be smokers, separated or divorced, and menopause; they, and were less likely to be educated, office workers, and have habits of regular exercise and regular napping. partici-pants with frequent insomnia were older, had a lower body mass index, higher blood pressure, higher cholesterol, triglyc-eride, fasting glucose, and less nap time.

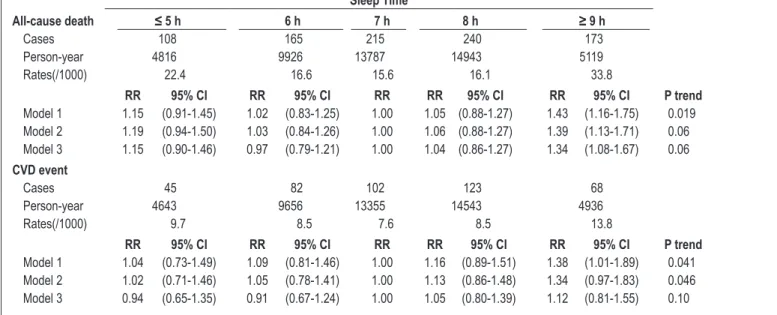

during a median 15.9 (interquartile range, 13.1 to 16.9) years’ follow-up period, 420 cases developed cardiovascular disease and 901 cases died. the incidence rates, relative risks for all-cause death and cardiovascular events are listed in table 2. A U-shape association between sleep duration and all-cause death was found: the age and gender-adjusted relative risks (95% ci)

of all-cause death (with 7 h of daily sleep being considered the reference group) for individuals reporting ≤ 5 h, 6 h, 8 h, and ≥ 9 h were 1.15 (0.91-1.45), 1.02 (0.85-1.25), 1.05 (0.88-1.27), and 1.43 (1.16-1.75, p for trend, 0.019), respectively. After ad-justing for various potential confounding factors, the relative risk (95% CI) for all-cause death in the group with ≥ 9 h of sleep was 1.34 (1.08-1.67). the U-shape relationship between sleep duration and risk of all-cause death was also observed by splines method (figure 1), with the test for a linear relation being rejected (p = 0.035). however, the relationship between sleep duration and risk of cVd was linear. the multivariate-adjusted relative risks (95% ci) for cVd (with 7 h as reference) for participants reporting ≤ 5 h, 6 h, 8 h, and ≥ 9 h were 0.94 (0.65-1.35), 0.91 (0.67-1.24), 1.05 (0.80-1.39), and 1.12 (0.81-1.55), respectively (test for trend, 0.10).

table 1 —Distribution of baseline demographic, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors in the CCCC study population (1990-91) by sleep duration and insomnia severity status

sleep time insomnia severity

≤ 5 h 6 h 7 h 8 h ≥ 9 h p no occasional Frequent nearly everyday p

n 351 680 955 1041 403 2025 889 351 78 Gender 0.17 < 0.0001 Men 47.9 47.5 44.9 50.3 45.7 52.8 40.4 36.8 41.0 Women 52.1 52.5 55.1 49.7 54.3 47.2 59.6 63.3 59.0 Cardiovascular disease 8.6 6.2 5.6 6.1 10.2 0.013 5.7 7.8 7.4 11.5 0.05 smoker 38.2 34.1 33.3 39.8 38.7 0.018 40.2 31.7 30.5 29.5 < 0.0001 alcohol drinking 36.2 31.8 26.6 32.0 26.6 0.002 32.9 25.9 24.5 32.1 0.0001 regular exercise 21.9 18.1 16.0 12.2 10.2 < 0.0001 17.0 12.2 14.0 15.4 0.008 hypertension 33.7 29.8 26.3 27.2 40.9 < 0.0001 27.2 32.7 33.3 38.5 0.002 type 2 diabetes 16.0 14.5 12.4 11.1 14.0 0.09 12.5 12.5 15.2 14.3 0.52 insomnia complaint < 0.0001 No 46.7 57.9 63.8 65.7 56.5 Sleep duration < 0.0001 Occasional 23.3 26.4 27.2 25.5 31.2 ≤ 5 h 7.9 9.0 20.2 41.0 Frequent 20.7 13.8 7.6 7.7 10.2 6 h 18.9 19.6 25.9 16.7 Nearly everyday 9.3 2.0 1.4 1.2 2.1 7 h 29.5 28.7 20.2 16.7 8 h 32.8 29.0 22.2 15.4 ≥ 9 h 10.9 13.7 11.4 10.3 mean mean age, yr 56.7 54.2 53.7 53.6 60.0 < 0.0001 53.5 56.4 57.5 58.2 < 0.0001 bmi, kg/m2 23.6 23.7 23.4 23.3 23.5 0.13 23.6 23.4 23.1 22.8 0.05 systolic bp 127.8 125.2 123.9 124.5 131.2 < 0.0001 124.5 127.2 126.8 129.1 0.002 diastolic bp 78.4 77.4 76.5 76.7 78.7 0.002 76.8 77.5 78.1 79.3 0.041 total cholesterol 198.8 197.7 197.5 196.2 202.1 0.28 195.0 201.3 204.4 195.6 0.000 triglyceride 128.0 127.1 125.5 120.5 133.3 0.21 124.2 126.8 126.1 127.3 0.009 hdl cholesterol 47.8 47.7 47.7 47.5 47.0 0.90 47.6 47.2 48.9 46.6 0.91 ldl cholesterol 138.7 136.8 137.4 135.5 143.2 0.07 134.6 140.9 145.1 136.4 0.17 Fasting glucose 111.1 111.2 109.2 109.1 111.0 0.51 109.8 109.2 111.2 108.8 < 0.0001

nap time, min 35.1 32.8 31.3 31.0 37.3 0.06 32.2 33.3 32.2 24.2 < 0.0001

uric acid, mg/dl 5.9 5.8 5.6 5.6 5.6 0.017 5.7 5.5 5.5 5.9 0.31

sleep time, h 4.6 6.0 7.0 8.0 9.3 < 0.0001 7.2 7.2 6.7 6.1 0.75

the incidence rates, relative risks for all-cause death and cVd event for insom-nia complaints are listed in table 3. the multivariate-adjusted relative risk (95% ci) for all-cause death (using individu-als without insomnia) were 1.02 (0.86-1.20) for occasional, 1.15 (0.92-1.42) for frequent, and 1.70 (1.16-2.49) for nearly everyday insomnia (p for trend, 0.028). similar patterns were found for cVd events: compared with those without in-somnia, individuals with occasional, fre-quent and nearly everyday insomnia had a 1.07 (0.85-1.36), 1.05 (0.75-1.46), and 1.78 (1.03-3.08)-fold risk of developing CVD. The results for stratified analysis by age and gender were similar (data not shown).

in a joint analysis of sleep duration as well as insomnia severity and the risk of all-cause death and cVd (figure 2), par-ticipants sleeping ≥ 9 h and frequent in-somnia had the highest risk for all-cause death and cVd risk, compared with those with sleeping 7 to 8 h and scanty insom-nia. the multivariate adjusted relative risk (95% ci) was 2.53 (1.71-3.76) for all-cause death and 2.07 (1.11-3.85) for cVd rate in participants sleeping ≥ 9 h and fre-quent insomnia.

table 2—Incidence rates and relative risks (95% confidence intervals) of all-cause death and cardiovascular disease event during median 15.9 years of follow-up according to habitual sleep hour In 1990-91 for the CCCC study participants

all-cause death sleep time ≤ 5 h 6 h 7 h 8 h ≥ 9 h Cases 108 165 215 240 173 Person-year 4816 9926 13787 14943 5119 Rates(/1000) 22.4 16.6 15.6 16.1 33.8 rr 95% CI rr 95% CI rr rr 95% CI rr 95% CI p trend Model 1 1.15 (0.91-1.45) 1.02 (0.83-1.25) 1.00 1.05 (0.88-1.27) 1.43 (1.16-1.75) 0.019 Model 2 1.19 (0.94-1.50) 1.03 (0.84-1.26) 1.00 1.06 (0.88-1.27) 1.39 (1.13-1.71) 0.06 Model 3 1.15 (0.90-1.46) 0.97 (0.79-1.21) 1.00 1.04 (0.86-1.27) 1.34 (1.08-1.67) 0.06 CVd event Cases 45 82 102 123 68 Person-year 4643 9656 13355 14543 4936 Rates(/1000) 9.7 8.5 7.6 8.5 13.8 rr 95% CI rr 95% CI rr rr 95% CI rr 95% CI p trend Model 1 1.04 (0.73-1.49) 1.09 (0.81-1.46) 1.00 1.16 (0.89-1.51) 1.38 (1.01-1.89) 0.041 Model 2 1.02 (0.71-1.46) 1.05 (0.78-1.41) 1.00 1.13 (0.86-1.48) 1.34 (0.97-1.83) 0.046 Model 3 0.94 (0.65-1.35) 0.91 (0.67-1.24) 1.00 1.05 (0.80-1.39) 1.12 (0.81-1.55) 0.10 *: test for trend

Model 1: adjusted for age groups (35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, ≥ 75 years old) and gender,

Model 2: Model 1 plus BMI (< 18, 18-20.9, 21-22.9, 23-24.9, ≥ 25), smoking (yes/no or abstinence), current alcohol drinking (regular/no), marital status(single, married and living with spouse, or divorced and separate), education level (< 9 years, ≥ 9 years), occupation (no work, manual or office job), regular exercise (yes vs. no), family history of coronary heart disease

Model 3: Model 2 plus baseline hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), cholesterol, HDL, triglyceride, glucose, and uric acid level

table 3—Incidence rates and relative risks (95% confidence intervals) of all-cause death and cardiovascular disease event during median 15.9 years of follow-up according to insomnia in 1990-91 for CCCC study participants

all-cause death

insomnia

no occasional Frequent nearly everyday

Cases 498 233 113 32 Person-year 29083 12594 4729 973 Rates(/1000) 17.1 18.5 23.9 32.9 rr rr 95% CI rr 95% CI rr 95% CI p* Model 1 1.00 0.97 (0.83-1.14) 1.18 (0.96-1.45) 1.65 (1.16-2.37) 0.023 Model 2 1.00 0.99 (0.84-1.16) 1.16 (0.94-1.42) 1.84 (1.27-2.65) 0.016 Model 3 1.00 1.02 (0.86-1.20) 1.15 (0.92-1.42) 1.70 (1.16-2.49) 0.028 CVd event Cases 227 118 47 15 Person-year 28244 12187 4592 935 Rates(/1000) 8 9.7 10.2 16 rr rr 95% CI rr 95% CI rr 95% CI p* Model 1 1.00 1.09 0.87 1.37 1.12 0.82 1.54 1.62 0.94 2.78 0.12 Model 2 1.00 1.10 0.87 1.38 1.15 0.83 1.58 1.78 1.03 3.06 0.07 Model 3 1.00 1.07 (0.85-1.36) 1.05 (0.75-1.46) 1.78 (1.03-3.08) 0.17 *: test for trend

Model 1: adjusted for age groups (35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, ≥ 75 years old) and gender, Model 2: Model 1 plus BMI (< 18, 18-20.9, 21-22.9, 23-24.9, ≥ 25), smoking (yes/no or abstinence), current alcohol drinking (regular/no), marital status(single, married and living with spouse, or divorced and separate), education level (< 9 years, ≥ 9 years), occupation (no work, manual or office job), regular exercise (yes vs. no), family history of coronary heart disease

Model 3: Model 2 plus baseline hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), cholesterol, HDL, triglyceride, glucose, and uric acid level

composed of 1.1 million adults aged 30 to 102 years were fol-lowed from 1982 to 1988 showed a U-shape association be-tween sleep duration and all-cause death.1 Among 82,969 women from the nurses health study who were followed up for 14 years, A U-shape relationship between sleep duration and all-cause death was also found after multiple covariate adjust-ment.2 compared with women sleeping 7 h, women sleeping ≤ 5 h had a 1.15-fold (95% CI, 1.02-1.29) risk, and women sleeping ≥ 9 h had a 1.42-fold (95% CI, 1.27-1.58) risk for all-cause death.2 however, the U-shape association was not found in Japanese women.4-5 compared with those sleeping 7-8 h, women sleeping shorter than 6 h had a 0.7-fold (95% ci, 0.2-2.3) risk and women sleeping 9 h or longer had a 1.5-fold (95% ci, 1.0-2.4) risk for all-cause death..5 furthermore, the associa-tion between sleep duraassocia-tion and all-cause death were observed only in elderly, but not in middle-aged adults.3 Another cohort based on scottish adults also showed only short sleep duration was associated with cardiovascular and all-cause death.40 A co-hort based on the nation-wide representative sample of 3079 taiwanese adults 64 years and older who were followed for 10 years showed a longer sleeping time (≥ 10 h for men and ≥ 8 h for women) was associated with the risk of all-cause death6: the multivariate risk was 1.42 (95% ci, 1.08-1.86) for men and we tested the performance measures for all-cause death and

cVd risk with and without sleep duration and insomnia com-plaints in the multivariate models using AUc, nri, and idi sta-tistics (supplementary table). Adding sleep duration provided a modest improvement in predicting the risk of all-cause death and cVd beyond the standard risk factors by AUc measures (AUc, from 0.854 to 0.855 for all-cause death, from 0.741 to 0.740 for cVd event, p, 0.24 and 0.09). However, the significant NRI and idi values for all-cause death indicated that adding sleep dura-tion informadura-tion resulted in a better discriminadura-tion improvement (nri, 2.0%, p, 0.023; idi, 0.3%, p, 0.003). sleep duration did not improve prediction for cVd events. similarly, adding insomnia information results in a modest discrimination for all-cause death (idi, 0.2%, p, 0.017) and cVd events (idi, 0.2%, p 0.049). disCussion

in this cohort of middle-aged to older chinese, habitual sleep duration and insomnia severity were significantly associ-ated with increased future risk of all-cause deaths. longer sleep time and frequent or nearly everyday insomnia appeared to be a stronger predictor of all-cause death.

previous studies have shown the consistency of long sleep duration for the risk of all-cause death.1,2 A large population

Figure 1—Relationship between habitual sleep duration and the risks of all-cause death (left) and CVD event (right). The multivariate adjusted relative risk is plotted as a function of the baseline sleep duration value with the 95% confidence bands shown as the shaded areas

2.4 3.2 4.0 4.8 5.6 6.4 7.2 8.0 8.8 9.6 10.4 Habitual sleep duration, hr

2.4 3.2 4.0 4.8 5.6 6.4 7.2 8.0 8.8 9.6 10.4 Habitual sleep duration, hr

Adjusted relative risk Adjusted relative risk

1.96 1.82 1.68 1.54 1.40 1.26 1.12 0.98 0.84 0.70 0.56 2.2 2.0 1.8 1.6 1.4 1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2

was 1.79 (95% ci, 1.48-2.17).7 based on 71,617 female health professionals aged 45-65 y during a 10-y follow-up, Ayas and colleagues8 demonstrated a U-shape association between sleep duration and the risk of coronary ar-tery disease. for the risk of stroke, a prospective cohort based 93,175 postmenopausal women aged 50-79 y who were followed for 7.5 y showed a U-shape relationship between sleep duration and ischemic stroke risk.41 the associations were stronger among women without prevalent cardiovas-cular disease at baseline.41 however, our data did not support sleep duration as an independent predictor for cVd event after adjustment for extensive biochemical measurements. there-fore, we proposed that the underlying mechanistic mediators for the putative adverse effect of long sleep was medi-ated by clinical and biochemical mea-sures. in fact, recent study on coronary artery calcification severity showed that the longer sleepers (≥ 8 h) were at similar risk for calcification incidence as 6 to 8 h sleepers.43

with regards to insomnia severity, our results are consistent with previ-ous studies conducted in primarily caucasian populations. in another co-hort study based on 6896 adults aged 45 to 74 y in Augsburg city for a mean follow-up period of 10.1 y, sleep dura-tion and sleep complaints were associ-ated with risk of incident myocardial infarction, especially among women.9 moreover, poor sleep quality, such as daytime somnolence, was associated with a 1.9-fold (95% ci, 1.2-3.1) risk for stroke.42 frequent insomnia was associated with cardiovascular disease risk among 1986 british men aged 55-69 y for a 10-y follow-up duration.21 insomnia complaints predicted an in-creased risk of cardiovascular disease (relative risk, 1.5; 95% ci, 1.1-2.0) and hypertension (relative risk, 1.2; 95% ci, 1.03-1.3) in north American communities.44 in our study, insomnia severity was as important as sleep dura-tion in predicting cardiovascular disease risk, which was con-sistent with other studies. in addition, our study showed that increased mortality appeared restricted to those with both self-reported insomnia and long sleep duration. This finding may reflect “nonrefreshing sleep” for reasons other than insomnia, such as sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, or sys-temic disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first extensive investigation of sleep duration and risk of all-cause death and cVd events 2.26 (95% ci, 1.59-3.22) for women. the lack of U-shape

rela-tionship for this elderly taiwanese cohort may be attributed to only one group < 7 h.6 our results did not support gender and age as the effect modifier for the effects of sleep duration and all-cause death.

with regards to cardiovascular events, the available evidence was inconsistent. Among 58,044 Chinese adults aged ≥ 45 y in singapore who were followed up for 13 y, both short and long sleep durations were associated with coronary artery disease mortality.7 compared with adults with a sleep duration of 7 h, the multivariate relative risk for a sleep duration of 5 h was 1.57 (95% CI, 1.32-1.88), and for a sleep duration ≥ 9 h, the risk

Figure 2—Joint effects of sleep duration and insomnia frequency for all-cause death and CVD events during median 15.9 y of follow-up, adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, smoking, current alcohol drinking, marital status, education level, occupation, regular exercise, family history of coronary heart disease, baseline hypertension, diabetes, cholesterol, HDL, triglyceride, glucose, and uric acid level

≤ 6 hr Scanty insomnia CVD event 4 3 2 1 0 Relative risk 7-8 hr

Scanty insomnia ≥ 9 hrScanty insomnia ≤ 6 hrFrequent insomnia 7-8 hrFrequent insomnia ≥ 9 hrScanty insomnia 1.3 1.0 0.8 1.5 1.1 0.8 2.3 1.5 1.0 3.8 2.1 1.1 1.1 0.7 0.4 1.0 ≤ 6 hr Scanty insomnia All-cause death 4 3 2 1 0 Relative risk 7-8 hr

Scanty insomnia ≥ 9 hrScanty insomnia ≤ 6 hrFrequent insomnia 7-8 hrFrequent insomnia ≥ 9 hrScanty insomnia 1.2 1.0 0.9 1.6 1.3 1.0 1.6 1.2 0.9 3.8 2.5 1.7 1.5 1.1 0.8 1.0

3. Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Sleep duration as-sociated with mortality in elderly, but not middle-aged, adults in a large Us sample. sleep 2008;31:1087-96.

4. tamakoshi A, ohno Y. self-reported sleep duration as a predic-tor of all-cause mortality: results from the JAcc study, Japan. sleep 2004;27:51-4.

5. Amagai Y, ishikawa s, gotoh t, et al. sleep duration and mortality in Ja-pan: the Jichi medical school cohort study. J epidemiol 2004;14:124-8. 6. lan tY, lan th, wen cp, lin Yh, chuang Yl. nighttime sleep, chinese

afternoon nap, and mortality in the elderly. sleep 2007;30:1105-10. 7. shankar A, Koh wp, Yuan Jm, lee hp, Yu mc. sleep duration and

coro-nary heart disease mortality among chinese adults in singapore: a popu-lation-based cohort study. Am J epidemiol 2008;168:1367-73.

8. Ayas nt, white dp, manson Je, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch intern med 2003;163:205-9. 9. meisinger c, heier m, lowel h, schneider A, doring A. sleep duration

and sleep complaints and risk of myocardial infarction in middle-aged men and women from the general population: the MONICA/KORA Augsburg cohort study. sleep 2007;30:1121-7.

10. patel sr, malhotra A, white dp, gottlieb dJ, hu fb. Association between reduced sleep and weight gain in women. Am J epidemiol 2006;164:947-54.

11. van den berg Jf, Knvistingh neven A, tulen Jh, et al. Actigraphic sleep duration and fragmentation are related to obesity in the elderly: the rot-terdam study. int J obes (lond) 2008;32:1083-90.

12. chaput Jp, despres Jp, bouchard c, tremblay A. the association between sleep duration and weight gain in adults: a 6-year prospective study from the Quebec family study. sleep 2008;31:517-23.

13. Ayas nt, white dp, Al-delaimy wK, et al. A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. diabetes care 2003;26:380-4.

14. Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, et al. Gender-specific associati-ons of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension: the whitehall ii study. hypertension 2007;50:693-700.

15. gottlieb dJ, redline s, nieto fJ, et al. Association of usual sleep duration with hypertension: the sleep heart health study. sleep 2006;29:1009-14.

16. hale l, do dp. racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. sleep 2007;30:1096-103.

17. singh m, drake cl, roehrs t, hudgel dw, roth t. the association bet-ween obesity and short sleep duration: a population-based study. J clin sleep med 2005;1:357-63.

18. phillips b, mannino d. correlates of sleep complaints in adults: the Aric study. J clin sleep med 2005;1:277-83.

19. chen mY, wang eK, Jeng YJ. Adequate sleep among adolescents is po-sitively associated with health status and health-related behaviors. bmc public health 2006;6:59.

20. Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Boden-Albala B, Heymsfield SB. Inade-quate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: analyses of the nhAnes i. sleep 2005;28:1289-96.

21. elwood p, hack m, pickering J, hughes J, gallacher J. sleep disturbance, stroke, and heart disease events: evidence from the caerphilly cohort. J epidemiol community health 2006;60:69-73.

22. mallon l, broman Je, hetta J. sleep complaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: a 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged swedish population. J intern med 2002;251:207-16.

23. phillips b, mannino dm. does insomnia kill? sleep 2005;28:965-71. 24. chien Kl, su tc, Jeng Js, et al. carotid artery intima-media thickness,

carotid plaque and coronary heart disease and stroke in chinese. plos one 2008;3:e3435.

25. chien Kl, hsu hc, su tc, sung fc, chen mf, lee Yt. lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease in ethnic chinese: the chin-shan community cardiovascular cohort study. clin chem 2008;54:285-91.

26. chien Kl, cai t, hsu h, et al. A prediction model for type 2 diabetes risk among chinese people. diabetologia 2009;52:443-450

27. chien Kl, hsu hc, sung fc, su tc, chen mf, lee Yt. metabolic syn-drome as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke: An 11-year pro-spective cohort in taiwan community. Atherosclerosis 2007;194:214-21. 28. lee Yt, lin rs, sung fc, et al. chin-shan community cardiovascular

Cohort in Taiwan: baseline data and five-year follow-up morbidity and mortality. J clin epidemiol 2000;53:836-46.

among ethnic chinese. evidence from other Asian populations also demonstrates that sleep duration and quality were associ-ated with increasing risk events, but head-to-head comparison of sleep duration and insomnia severity has not been available. because of the prospective cohort design, the baseline measure-ments of all cohort members were unlikely to be affected by storage and laboratory issues that might be raised in some nested case-control studies. the use of a community-based population could reduce the possibility of selection bias. we also included important socioeconomic, lifestyle, and clinical factors in the models to control the potential confounding factors. previous studies did not include biochemical measures, which confound-ed the association with the outcomes. in addition, combining habitual sleep duration and insomnia complaints from self-re-ported data improved the prediction of all-cause death.

our study had several potential limitations. first, because self-reported sleep duration and insomnia data were measured only once, our results might be attenuated by intra-individual variations. self-reported sleep duration was used; no other ob-jective measures (e.g., actigraphy) were used. second, we did not include prescription sleeping pill dosage in our study be-cause of limited medical records in this cohort. previous studies showed prescription sleeping pill use was also associated with all-cause death.1 finally, our measure on self-reported insomnia severity is a measure of sleep quality, but does not include sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, depression, or a multitude of oth-er disordoth-ers. insomnia is poth-erceived as a symptom that could be associated with a variety of psychiatric and medical disorders.45 Insomnia was considered as the symptoms of difficulty initiat-ing and maintaininitiat-ing sleep or experiencinitiat-ing nonrefreshinitiat-ing sleep and is associated with daytime consequences.46 our study did not clarify these symptoms; thus misclassification may exist.

in conclusion, we clearly demonstrate that sleep duration and insomnia severity were associated with all-cause death and cVd events among ethnic chinese in taiwan. our data indi-cates that optimal sleep duration (7-8 h) and scanty insomnia predicted fewer cVd events and less death. further studies are warranted to better understand the possible mechanisms for sleep duration and insomnia.

aCknoWledGments

we thank the participants in the chin-shan community and the cardiologists at the national taiwan University hospital for their assistance in this study. this study was supported partly by grants from the national science council in taiwan (nsc 96-2314-b-002-155, nsc 97-2314-b-002 -130 -mY3) and na-tional taiwan University hospital (ntUh 98-s1056).

disClosure statement

this was not an industry supported study. the authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

reFerenCes

1. Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Morta-lity associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch gen psychiatry 2002;59:131-6.

2. patel sr, Ayas nt, malhotra mr, et al. A prospective study of sleep du-ration and mortality risk in women. sleep 2004;27:440-4.

38. ridker pm, buring Je, rifai n, cook nr. development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the reynolds risk score. JAmA 2007;297:611-9.

39. pencina mJ, d’ Agostino rb sr, d’ Agostino rb Jr, Vasan rs. evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157-72. 40. heslop p, smith gd, metcalfe c, macleod J, hart c. sleep duration

and mortality: the effect of short or long sleep duration on cardiovas-cular and all-cause mortality in working men and women. sleep med 2002;3:305-14.

41. chen Jc, brunner rl, ren h, et al. sleep duration and risk of ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women. stroke 2008;39:3185-92.

42. Qureshi Ai, giles wh, croft Jb, bliwise dl. habitual sleep patterns and risk for stroke and coronary heart disease: a 10-year follow-up from nhAnes i. neurology 1997;48:904-11.

43. King cr, Knutson Kl, rathouz pJ, sidney s, liu K, lauderdale ds. Short sleep duration and incident coronary artery calcification. JAMA 2008;300:2859-66.

44. phillips b, mannino dm. do insomnia complaints cause hypertension or cardiovascular disease? J clin sleep med 2007;3:489-94.

45. roehrs t, roth t. sleep disorders: an overview. clin cornerstone 2004;6 suppl 1c:s6-16.

46. roth t, roehrs t. insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and conse-quences. clin cornerstone 2003;5:5-15.

29. chien Kl, lee Yt, sung fc, hsu hc, su tc, lin rs. hyperinsulinemia and related atherosclerotic risk factors in the population at cardiovascular risk: a community-based study. clin chem 1999;45(6 pt 1):838-46. 30. chien Kl, hsu hc, sung fc, su tc, chen mf, lee Yt. hyperuricemia

as a risk factor on cardiovascular events in taiwan: the chin-shan com-munity cardiovascular cohort study. Atherosclerosis 2005;183:147-55. 31. Wieland H, Seidel D. A simple specific method for precipitation of low

density lipoproteins. J lipid res 1983;24:904-9.

32. durrleman s, simon r. flexible regression models with cubic splines. stat med 1989;8:551-61.

33. hosmer dw Jr, lemeshow s. the multiple logistic regression mod-el. Applied logistic regression. 1 ed. new York: John wiley & sons, 1989:25-37.

34. hanley JA, mcneil bJ. A method of comparing the areas under receive operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. radiology 1983;148:839-43.

35. greiner m, pfeiffer d, smith rd. principles and practical application of the receiver-operating characteristic analysis for diagnostic tests. prev Vet med 2000;45:23-41.

36. delong er, delong dm, clarke-pearson dl. comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. biometrics 1988;44:837-45.

37. cook nr. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. circulation 2007;115:928-35.