一個以形成性評量與回饋意見在

英文寫作課實踐批判思考教學的行動研究

黃淑真

摘 要

本行動研究報導一位大學英文教師在寫作教學的改進過程。最 初的教學包含四次指定題目的寫作與修改練習,教師已疲於批改, 但仍欠缺藉由寫作以訓練批判思考與獨立發聲的重要元素。為求改 進,教師安排自選題作文,加入多階段多來源的形成性評量與回饋 設計,示範進而導引學生在構思過程中相互評量與批判,並安排期 末的成果發表儀式。過程中,任課教師不再是唯一的評量者與意見 回饋來源,而是將文章的發展從訂定主題、大綱、細部論點、草稿、 修改到校對分成六個階段,並在每個階段安排兩種不同人員提供回 饋,如助教及同儕。這些回饋意見包含了批評與挑戰,協助寫作學 習者在文章發展過程中改進。最終產出的小論文成品以批判思考力 評量表檢驗,結果顯示,學生多能選擇切身議題、表達個人意見, 且對批判思考的結構有所掌握,唯在批判思考的內容論證上仍有改 進空間。 關鍵詞: 形成性評量、評量回饋、批判思考、英語教學、英文寫作黃淑真(通訊作者),政治大學外文中心副教授 電子郵件:huang91@nccu.edu.tw 投稿日期:2015 年 07 月 16 日;修正日期:2015 年 11 月 18 日;接受日期:2015 年 12 月 31 日

AN ACTION RESEARCH ON FOSTERING

CRITICAL THINKING IN EFL WRITING

THROUGH FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

AND FEEDBACK

Shu-Chen Huang

ABSTRACT

This action research reports how a college English teacher improved her essay writing instruction. The original course design consisted of instruction and four rounds of drafting and revising under assigned topics. While the teacher had been busy enough giving individual feedback, an important element of cultivating critical thinking and giving learners a voice was absent from the course. To address the problem, the teacher required learners to write an additional essay on a topic they each chose, designed an assessment scheme with multi-stage and multi-source feedback, and celebrated the final products at the end of the semester. During the process, the teacher was no longer the only feedback provider. Instead, essay development was arranged into six stages including idea generation, general outline, detailed outline, drafting, editing and proofreading. For each stage, feedback came from two different sources, such as the teaching assistant and peers. The feedback consisted of questions and challenges and helped the author learners improve from one stage to the next. The resultant essays were examined against a critical thinking rubric. Analysis indicated that these essays demonstrated unique personal opinions and that the writers had control over the structure of critical thinking. But in terms of the soundness of reasoning, there was more room for improvement.

Keywords: formative assessment, assessment feedback, critical thinking, teaching English as a foreign language, English writing

Shu-Chen Huang (corresponding author), Associate Professor, Foreign Language Center, National Chengchi University.

E-mail: huang91@nccu.edu.tw

Manuscript received: July 16, 2015; Modified: November 18, 2015; Accepted: December 31, 2015 DOI : 10.6151/CERQ.2016.2401.03

Introduction

It is the responsibility of college English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) teachers in Taiwan to educate young adults to become capable of clearly expressing opinions in the lingua franca of the global community. This basic yet fundamental ability has often been manifested by university authorities in their mission statements as objectives for general and liberal education. The relevant common core ability indicators often include logical thinking, clear judgment, and effective communication, followed by more specific descriptions such as writing well-organized English paragraphs. This noble manifestation, however, is usually constrained by dwindling resources in mass higher education and is seldom scrutinized in a systematic manner. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to explore ways in which an EFL teacher can improve her instruction in an English writing class to fulfill the aforementioned ideals by undertaking an action research.

Action research is a process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking the action. By engaging in action research, the “actor’s” primary purpose is to improve and/or refine his/her actions (Sagor, 2000). According to Lewin (1946), procedures of action research consist of a number of phases: Identifying a problem, planning, carrying out an action, observation, and reflection. Because of its grass-root nature, action research helps to solve problems defined by and directly relevant to the actor, thereby giving those involved in the process an empowering experience. In this paper, the author/teacher/researcher/actor will first describe the problems she encountered, and then illustrate how a plan was devised and carried out with the help of insights from the relevant literature. Then, the observed results will be examined and reflections will be provided on the implementation of the action research.

The Problems Identified

The course in question was a one-semester, two-credit EFL elective College English III: Essay Writing admitting a maximum of twenty students from different disciplines and different years at the undergraduate level. Prerequisites to this course were the required College English I and College

English II in the freshman year. Main texts included Great Writing 4: Great Essays (Folse, Muchmore-Vokoun, & Solomon, 2010) and Writing Academic

EnglishLevel 4 (Oshima & Hogue, 2006). The students met once a week for two hours over a period of eighteen weeks. The model essays taught and followed by the learners mostly had a five-paragraph structure, ranging from 500 to 600 words in length, with the first paragraph as an introduction, the final one a conclusion, and the middle three as the body. The essays usually started with a hook to attract reader attention, which then connected to the thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph. Each body paragraph focused on one point to support the thesis and typically had a clear topic sentence that was followed by supporting details. The concluding paragraph repeated the thesis with no new information added. Following the same pattern, the students studied relevant model essays and then practiced one genre after another, from exposition, comparison, cause-effect, to argumentation, each with an assigned topic to be drafted in class and revised afterwards. When it came to argumentation, learners were taught to take a stance. They also needed to consider the opposing points of view in a further paragraph inserted before the concluding one. In this additional paragraph, opposing views were recognized and followed by refutations and relevant supports.

While having all of the students write one essay every four weeks on average, each with a draft written in class and a corresponding revision later to be word-processed and uploaded on the course Moodle platform, the teacher was busy furnishing individual comments to guide learners through their process of revision. An account of the original design, especially of how the learners were involved in a continuous dialogue with the teacher on their essay work, can be found in Huang (2016). Although it was desirable to have learners write beyond the assigned topics at the end, so as to showcase the abilities which they had learned and express their voice on issues of their concern, the teacher could not afford the additional time and effort. Moreover, despite the resources invested in the course, the figure for course satisfaction from the university survey was mediocre at 82.26. Students seemed to be buried in the necessary fundamentals of essay writing and did not have the luxury to experience the excitement of writing and to have their own voice heard, let alone realize the common higher education ideal of cultivating critical thinking (CT). The teacher was already exhausted by having to provide regular timely feedback and felt like a Cinderella doing all of the dirty chores without getting the due effect and being appreciated.

Before the author was ready to run the same course again in the Fall 2013 semester, she hoped to address the problems observed by instilling components lacking in the previous round, at the same time limiting her

intervention as well as time and effort to a minimum. On top of the existing curriculum and the four assignments for each genre introduced, questions considered included:

(1) How can students be given a chance to write an additional essay in which they express opinions on issues they are concerned about? (2) What resources, in addition to the teacher, in the classroom and

university could be mobilized to facilitate learners in thinking more critically as they write and revise this essay? and

(3) What can be done to give learners a sense of ownership of what they write?

Guided by these questions, the author turned to research findings for inspiration before she redesigned her course.

Literature Review

Relevant literature comes mainly from two areas: The teaching of CT alongside writing and formative assessment for the purpose of enhanced learning. The former helps the teacher to learn from the experiences of other EFL teachers who have tried teaching CT in writing. The latter provides guidelines and principles for how assessment of and feedback on the learner's written work could be more effectively arranged.

Teaching Critical Thinking

CT is oftentimes associated with writing and learning to write (e.g., Quitadamo & Kurtz, 2007). Bensley and Haynes (1995) pointed out that it is the commonalities shared by CT and writing that make many teachers use writing for the training of CT. Unlike oral discussions in which words can only be qualified or reconsidered with difficulty, written assignments can be structured to allow for the revision and refinement of ideas, which is an integral part of CT (Wade, 1995). However, well-written but poorly reasoned student papers make teachers aware that, although good writing requires CT, writing itself, if not carefully planned, does not necessarily improve CT (Goodwin, 2014). An example of such planning for CT to be developed in student writing is found in Cavdar and Doe (2012). They designed writing assignments in two stages, using postscripts as a strategy for improving CT. Learners were thus encouraged to reconsider concepts, critically evaluate

assumptions, and undertake substantive revisions of their writing. Their study shows that learners were able to write and argue better due to being critically challenged.

When teachers cultivate CT with writing in a foreign language setting, the issue becomes more complicated. Atkinson (1997) believed that CT is a tacit social practice in some cultures that children, such as those in the U.S. mainstream, grow up with. In other cultures, such as those of many Asian countries, people value qualities such as empathy and conformity, which run counter to the spirit of CT. Atkinson (1997) therefore contended that attempts to teach CT in the realm of EFL instruction are unproductive. Despite Atkinson’s position against teaching CT, EFL and other foreign language teachers’ aspiration to instill CT in their students has never faded away. For example, Stapleton (2002) called the above conception of Asian students a “tired” construct. His survey indicated that Japanese college students possessed a firm grasp of the elements of CT and that they expressed little hesitation in voicing opinions against authority figures. It is usually other factors, such as the topics that teachers assign for writing, which put foreign language learners at a disadvantage when they are compared to their native- speaking counterparts. Stapleton’s (2001) analysis showed that Japanese students’ CT was more evident in their essays when they wrote on a topic that they were familiar with (rice imports) than on an unfamiliar conventional western topic (gun control) taken from EFL textbooks. More specifically, on a particular CT element in argumentation, i.e., the recognition of counterargument and refutation, Liu and Stapleton (2014) demonstrated that Chinese learners benefited from the teaching of the two concepts and showed improvements in their argumentative essays. The aforementioned studies suggest that CT is teachable to foreign language writing learners, provided that learners are familiar with the topics they write on. But it is not clear how exactly we can go about teaching CT. A review of the literature beyond writing and EFL education may be helpful.

Approaches to Teaching Critical Thinking

Studies have shown that CT is not only teachable; it is transferrable and should be transferred across domains (Bensley & Murtagh, 2012; Halpern, 1998; Halpern & Nummedal, 1995). The teaching of CT has to be based on process and be deliberate, so that it can be spontaneously transferred to novel settings (de Sanchez, 1995). Karabulut (2012) reviewed 132 published articles

from 1977 to 2006 on social studies education and found three essential patterns for teaching CT: Classroom discussions, writing activities, and questions. McKeachie, Pintrich, Lin, and Smith (1986), in another review of college teaching and learning, concluded with three rewarding CT approaches: Student discussion, an explicit emphasis on problem solving, and verbalization of metacognitive strategies. King (1995) adopted an inquiry- based approach to teaching CT, which involved questioning, fostering questioning through modeling, and reciprocal peer questioning. Miri, David, and Uri’s (2007) effective strategies included dealing in class with real-world problems, encouraging open-ended discussions, and fostering inquiry-oriented experiments. Other approaches leading to the development of CT ranged from debate (Sziarto, McCarthy, & Padilla, 2014), group work (Fung, 2014), cooperative learning and giving a voice to students (Cooper, 1995), to using online discussion and facilitation from teaching assistants as a catalyst (Yang, 2008).

Underlying this wide array of approaches is a common core of challenging one’s reasoning and of verbalizing such reasoning explicitly in a variety of formats. No matter what particular format is adopted, divergent viewpoints, most possibly from peers and teachers who are actively engaged in the same problem or task, are aggressively sought and responded to so that student reasoning is challenged, modified, strengthened, and CT is, thus, developed. In order to link these types of inquisitive activity closely to instruction, Angelo (1995) subsumed these pedagogical endeavors under a big umbrella concept of classroom assessment. As Angelo explicated, “it is not the classroom assessment itself but the teacher’s and students’ responses to the assessment results that can lead to improved critical thinking” (p. 7).

Formative Feedback as an Approach to Teaching

Critical Thinking

Indeed, teacher’s and students’ responses, or feedback, are the critical part of classroom assessment that has the potential to guide and improve learning. But apart from Angelo’s (1995) very brief discussion of the concept, assessment and feedback have hardly ever been associated with the teaching of CT, let alone detailed explorations of how and how well it could be done. The author therefore explored the teaching of CT with an assessment and feedback design that incorporated various instructional approaches to inducing CT.

Formative assessment, or assessment for learning (as opposed to the assessment of learning), or learning-oriented assessment, as well as many other slightly different terms, is an area that has attracted abundant attention from researchers in the past two decades. Black and Wiliam (2009) call the classroom teacher’s assessment practice “a black box,” and advocate careful examination and refinement of such practice to improve teaching and learning. In their formative assessment theory, the teacher helps learners identify their learning objectives (where they are going) and the current performance level (where they are right now) by way of formative assessment. Teaching and learning is thus an action to bridge the observed gap and to move learners closer to where they want to go from where they currently are. One central tenet of Black and Wiliam’s theory states that assessment is not solely the teacher’s business. Learners also need to understand the criteria and standard expected of them, and be able to assess their performance accordingly. In order to achieve that, classroom teachers should first model assessment and feedback, and then provide opportunities for learners to practice such skills through interacting with peers. In the end, it is hoped that learners will be able to carry out their own self-assessment and provide feedback on their own learning and function independently when they exit the classroom.

Feedback, coming after assessment, could be seen as a more focused form of teaching that identifies and takes learners’ strengths and weaknesses into consideration (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Teacher feedback has therefore attracted extensive attention from researchers in recent years. However, most of these studies discovered that although many teachers spent a significant amount of their time assessing homework and furnishing assessment feedback for individual learners, such feedback was usually ineffective and unappreciated (e.g., Bailey & Garner, 2010; Price, Handley, Millar, & O’Donovan, 2010). Quality teacher feedback can often be filtered out because of the misalignment in perceptions between the teacher and the learners (Orsmond & Merry, 2011) or flaws in the way messages are communicated (Wingate, 2010). In addition, Orsmond and Merry (2013) point out problems such as focusing too much on the teacher and neglecting the students in many feedback studies. More specifically, Boud and Molloy (2012) contend that, for feedback, we should move away from the dominant teacher-telling conception to one that features students actively seeking, evaluating, and using feedback. Thus, teachers should guide learners to gradually master the necessary conceptions and skills involved in assessing learner work, so as to allow for the development of learner assessment and feedback capabilities, mainly by engaging learners in practicing assessment skills through peer feedback.

In fact, peers and learners themselves are believed to be significant providers of feedback who can benefit from the process and product of assessment (Black & Wiliam, 2009). As a scaffold, feedback does not have to be limited to the form of telling or explicitly correcting mistakes. Engin (2013) proposed five levels of scaffolding that range from direct telling to slot-fill prompts, closed yes/no questions, specific wh-questions, to general open questions. In fact, the more open-ended questioning that requires elaboration and explanation from learners, rather than a more authoritative judgment, would be more conducive to the cultivation of CT. Questions, challenges, or even disagreements all serve as catalysts; they may prompt learners to reflect on performance and consequently modify and strengthen the underlying logic of their work. Such reflection and modification usually do not come immediately. It takes time. As vividly captured in the ancient Chinese metaphor, the teacher is likened to a brass bell who responds to the enquirers, the bell strikers. The bell should not only sound contingent on the strength of the striker, it should also “allow some leisure so the sound can linger and go afar” (Huang, 2012).

Addressing the Problem by Designing a Feedback Scheme

Based on the above discussion, effective strategies for cultivating CT include presenting real-world problems, encouraging open-ended discussions, providing challenging feedback, and having learners work cooperatively with peers. The author designed a formative assessment scheme, with all of the CT- inducing elements integrated into it, to facilitate the development of CT while EFL learners were formulating ideas and drafting their essays. Instead of furnishing all of the feedback, the teacher’s role in this scheme could be depicted as that of a conductor orchestrating the assessment and feedback to be provided by the learners for the learners.In addition to the work to be done on the existing four assigned-topic essays, for the Fall 2013 semester, the students were also guided to work throughout the semester on one other essay whose topic and genre was of their own choosing. To address the action researcher’s first problem, i.e., giving learners a chance to express opinions on issues they are concerned about, this essay was meant to be a representative piece of work for each learner to demonstrate his/her learning achievement by expressing personal opinions.

To address the action researcher’s second problem, i.e., mobilizing other resources to facilitate CT and essay revision, she tried to spend as little class

time and teacher feedback time as possible on this essay. Instead, the students followed the teacher-designed procedures and worked on the essay mostly outside of class. It was hoped that the learners could transfer what they had learned from the instruction and feedback comments provided for the four assigned essays to this one featuring their genuine voice as independent writers. Another important objective was to shift the responsibility and power of the provision of feedback from the teacher to the learners by giving them various opportunities to seek feedback from the teaching assistant, campus Writing Center tutors, peers, and themselves. Details of this assessment design are provided below.

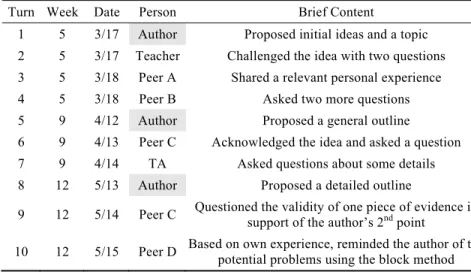

This formative assessment scheme featured multiple feedback sources at multiple stages. As shown in Table 1, there were six feedback stages throughout the lifespan of this essay, for each of which learners received feedback from two different sources.

The students were not introduced to this task until after Week 4 by when they had received the necessary orientation and done preliminary work on essay basics. The first three stages, which lasted for two months, focused on idea formulation. Idea generation and feedback at these stages took place in a discussion forum on the Moodle platform and were open to all course members. First, each student initiated a discussion string with a possible topic, the suitable genre identified, a brief description of the controlling ideas, and the potential problems they wanted to solve. Between Weeks 4 and 9, the teacher and two peers responded to the author so that original ideas were confirmed, expanded on, questioned, or challenged. The author did not have to respond immediately, but was given ample time to consider or incorporate relevant ideas into his/her work at the following stage.

Table 1

Formative Assessment with Multiple Feedback Sources at Multiple Stages

Week 5 9 12 13 16/17 18 Stages Sources 1 Brainstorming for topics 2 General outline 3 Detailed outline 4 First draft 5 Second draft 6 Final editing Teacher V Course TA V V V WC tutors V Peers V V V V Self V V V

* TA: Teaching assistant; WC: The English Writing Center established on campus by the Foreign Language Center to provide one-on-one consulting services to students.

In the second stage in Week 9, the author proposed a general outline with the major points for either the original, revised, or a brand new topic, posted at the end of his/her discussion string. This general outline was then commented on by the teaching assistant for the course and one peer.

Three weeks later, the author, after having considered all of the feedback, posted a detailed outline with added supporting details for the major points. By that time, some of the original topics and outlines had been extensively modified; others had been refined and expanded upon.

Table 2 illustrates the ten turns in one learner’s discussion string during the first three stages, with the date, contributor of the feedback, and a brief summary of the content. For example, in turn 2, the teacher challenged the author’s initial ideas and topic with two questions, which was followed on the next day by Peer A sharing a personal experience relevant to the proposed topic and Peer B asking two more questions.

After the first three stages when the course was two-thirds of the way through and three genres had been practiced with assigned topics under teacher guidance, the learner authors had also considered and modified their own topic ideas, main points, and supporting details with feedback from the teacher, the teaching assistant, and a few different peers. It was at this point that they started to draft the essay which is the focus of study in this action research.

Table 2

An Illustration of Proposals and Feedback on Essay Ideas

Turn Week Date Person Brief Content

1 5 3/17 Author Proposed initial ideas and a topic

2 5 3/17 Teacher Challenged the idea with two questions

3 5 3/18 Peer A Shared a relevant personal experience

4 5 3/18 Peer B Asked two more questions

5 9 4/12 Author Proposed a general outline

6 9 4/13 Peer C Acknowledged the idea and asked a question

7 9 4/14 TA Asked questions about some details

8 12 5/13 Author Proposed a detailed outline

9 12 5/14 Peer C Questioned the validity of one piece of evidence in support of the author’s 2nd point

At Stage 4, the learners were asked to take their first draft to the campus English Writing Center for the opinion of an outsider. The English Writing Center had been established by the university’s Foreign Language Center for about seven years. Selected graduate students of mostly English and Linguistics majors were trained each year to provide a free one-on-one consulting service. This service was not provided for any particular course, but teachers interested in using the service for their courses can contact the head tutor and specify particular needs. All of the students in the university can check the schedule, choose a tutor, make an appointment, and bring their own EFL writing to the center for discussions in half-hour sessions. As announced on the website of the Center, the tutors do not revise the writing for the students; instead, they usually ask the students to read their writing aloud, help them to clarify their points, and answer relevant questions. The tutors can also suggest strategies for making the written work better. After the learners on the course in this research had been to the center, the revised drafts were then brought to Stage 5.

Stage 5 was designed to have learners work cooperatively to get more challenges and feedback from each other. Stapled on top of each printed draft was a checklist of feedback items to be provided by peers in writing. In the four class hours during Weeks 16 and 17, the learners worked in four groups of four. In the first hour, they swapped drafts within the group to check the organization of the essays in the drafts. Guided by the question “Does any information need to be moved/deleted/added for better unity and coherence?”, they provided feedback for their peers. After this in-group check, the four drafts were passed outside of the group for further scrutiny. In the second hour, each group of learners received four drafts from their neighboring group and they worked together to check the appropriateness of the topic sentences in each paragraph based on what they had learned. In the third hour, the drafts went to a third group for feedback on supporting details. Finally, in the fourth hour, the drafts went to the final group for feedback on language and mechanics. The main responsibility of the peer feedback providers was to find problems and to point them out. It was the responsibility of the author to collect the feedback, consolidate it, and decide on how to revise his/her essay further. At the end of Week 17, the learners took their drafts and peer feedback back home for more revision on their own.

At Stage 6, i.e., two days later, the learners uploaded the revised work on Moodle. The teaching assistant then gave the essays a quick final proof using the track changes and comment functions in Word. Two days later, the

documents were uploaded to Moodle as feedback files for the learners to check again. Each learner author finalized his/her essay and uploaded a clean copy two days before the final class meeting in Week 18. The teaching assistant followed up by designing a simple cover, making a table of contents, and putting all of the essays together in a booklet. Each student received one copy on the final day of class, when all writers chose one short paragraph to read to the class, discussed his/her essay, and reflected on his/her journey of learning to write.

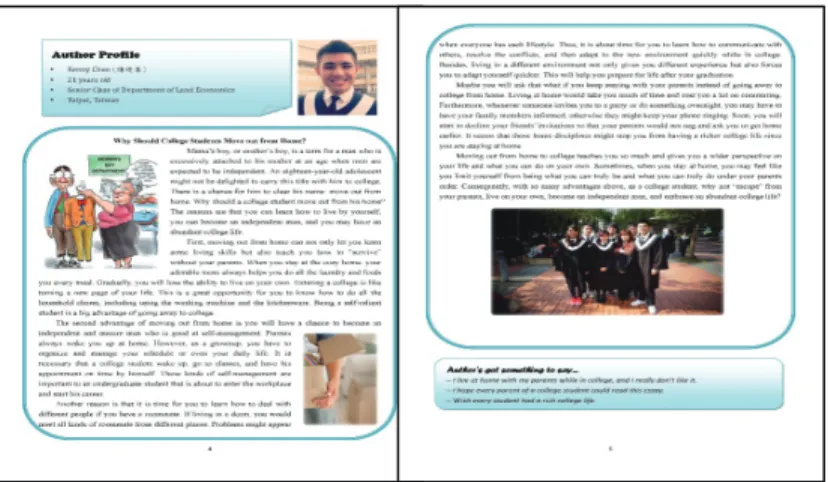

Last but not least, to address the action researcher’s third problem, i.e., the lack of a sense of ownership and hence the writer’s identity and passion, the aforementioned booklet served as a ceremonial artifact and the final class day as an event to celebrate learner accomplishment. In the booklet, each learner was allotted two pages for the printing of his/her essay, which was accompanied by a few illustrations or pictures that the author chose. Preceding the essay was an “author profile” section, in which the learner could put a personal photo and some biota. At the end of the two pages, there was a space for “The author’s got something to say…”, in which the learners briefly reflected on their writing experience or shared some afterthoughts. An image of the cover of the booklet is presented in Fig. 1. Figure 2 gives an example of one student’s two pages. The final class meeting, as the course was scheduled from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m., became a breakfast roundtable. In this roundtable, each author read part of his/her essay to the class, followed by some verbal reflection by the author and then questions and answers.

Figure 2. An Example of Printed Learner Work

Observation of Action Results

The action results were examined in three aspects: Learner satisfaction, what they wrote, and their CT as demonstrated in essays. The first two were examined through the university end-of-term course evaluation survey and the learners’ essays. The final part was more elaborated by scrutinizing CT as demonstrated in the essays.

Overall Course Satisfaction and Content of Learner Essays

First, the official course evaluation results as compared to the previous year showed a considerable improvement from 82.26 to 92.66, as presented in Table 3. The students were satisfied with this learning experience and felt a sense of achievement.The learners produced sixteen essays whose topics and theses are summarized in Appendix. For a quick overview, the average readability figures of these essays as calculated by Word were 675 words, 5.71 paragraphs, 37.21 sentences, 6.61 sentences per paragraph, 18.35 words per sentence, and 9.57 in the Flesch-Kincaid grade level. Of the genres chosen, there were eight argumentation (1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, and 14), four exposition (3, 4, 10, and 15), three comparison (2, 11, and 16) and one cause-effect (12) essays. As for topics, all of the essays were related to the authors’ current life or learning experiences. Somewere related to their

Table 3

Course Evaluation Results Before and After the Implementation of the Assessment Design

Evaluation Items 2012 2013

1. The instructor provided, at the beginning of the semester, a

complete syllabus that includes all the course requirements

and the grading criteria. 8.53 9.71

2. This course was well organized and prepared. 8.40 9.43

3. The instructor’s teaching materials were appropriate to the

abilities of the students. 7.87 9.29

4. The teaching methods were helpful for effective learning. 8.00 8.86

5. The instructor’s elaboration of the course contents was clear,

organized and systematic. 8.40 9.43

6. The grading was fair and reasonable. 8.27 9.23

7. The course materials were carefully-prepared and the

objectives of the syllabus were fully met. 8.00 9.14

8. The instructor encouraged students to ask questions and

participate in discussions. 7.73 9.00

9. The instructor was sincere and responsible in teaching, and

the class hours were effectively utilized. 8.53 9.57

10. I learned a lot from the course. 8.53 9.00

Total 82.26 92.66

own fields of study, such as 9 about Communication studies at the broader college level, 10 on the common core course of Economics, 1 on the study of Land Economics, 12 on Law, and 13 on a second foreign language as a major.

Interestingly, more than one third of the essays (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 13) were directly related to a current university practice or policy, and all of the authors argued against the status quo. For example, in 5 the author criticized the policy of taking the first year’s GPA as the major criterion for selecting students who wanted to transfer to a different department. The author of #6 argued against most teachers’ practice of including student attendance as part of their grading schemes. In #7, the author criticized the arrangements of the experimental co-ed dorm she was experiencing and called for a return to single-sex dorms. The author of #8 specified inherent problems and explained why he believed that the new campus Free Bike service would eventually fail. In #9, a senior who had almost completed his studies described

and critiqued his college’s new “undeclared-major-in-the-first-two-years” policy. The author of #13, with a somewhat sarcastic tone, advised others not to choose her major, despite its prestige, because she had seen several problems in its curriculum design. The choice of topics demonstrated that these learners paid attention to issues around them and that they were able to voice their unique and interesting opinions, which is an initial step into CT.

A Further Examination of the Action: Learners’ Critical

Thinking as Demonstrated in Their Self-selected-topic Essays

In research studies attempting to teach CT or identify relations between CT and other factors, the majority have used a number of instruments that break down the multidimensional construct of CT (e.g., skills, dispositions, metacognition) into subcategories and quantify it (e.g., Fung, 2014; Miri et al., 2007; Yang, 2008). In these cases, CT is mostly measured by learners’ responses to questionnaire items or to some pre-designed scenarios. Relatively fewer studies have examined CT in the work which the learners produced themselves. Among them, Stapleton (2001) examined learners’ EFL essays based on Toulmin’s (2003) argumentation model. His original analysis was based on calculating and comparing pieces of arguments, evidence, refutations, fallacies, and references. Nevertheless, Sampson and Clark (2008) pointed out with examples that, depending on the perspective of the reader, a particular learner statement could be classified as anything from a claim, warrant, or qualifier, to rebuttal. This phenomenon makes reliable classification of the argumentative elements in learner writing almost impossible.

More recently, Stapleton and Wu (2015) made a breakthrough and argued that many studies following the Toulmin-like model in examining learners’ writing for CT focused solely on structure and lost sight of substance, i.e., the quality of the reasoning. They examined Hong Kong students’ essays for the compatibility between structure and substance. Results indicated that those essays with good argumentative structures did not have sound reasoning. As a remedy, Stapleton and Wu (2015) introduced an integrated Analytic Scoring Rubric for Argumentative Writing in which both structure and substance could be addressed. In this rubric, structural elements of CT such as claims and reasons are broken down in the column and assigned different weightings in the row. The clarity of the statements and the soundness of the reasoning are evaluated against two to five levels. Finally, although instruments and rubrics evaluating CT are abundant, classroom teachers need to align assessment with

a focus on instruction (Bensley & Murtagh, 2012) and make necessary adaptations before using them with students.

For this reason and based on the above literature, a Critical Thinking Rubric (Table 4) was developed for the current study. In addition to having learners express a unique personal voice, CT, as shown in the essays, was operationally defined at two levels. At the first level of the essay structure, the elements of clear opinions, including the thesis, claims, reasons, and conclusion should be easily apparent to the readers. At the second level of substance, supports for the reasons should be sound/acceptable and free of irrelevance. The presentation of these reasons was divided into five degrees in terms of its success in convincing the readers. For the genre of argumentation in particular, because opposing views should be recognized and refutations be offered, these two elements were added in the first level. And the supports for this refutation were added for the second level.

Besides the author, two research assistants were invited as raters to check the learner essays against the customized CT rubrics. After a one-hour training session explaining the rubric and demonstrating how to assess four essays, one from each genre, the author researcher answered questions from the assistants before they each worked individually on the rating. Once the individual ratings were completed, the three raters met again to check the results and resolve discrepancies.

Adapted from Stapleton and Wu (2015), this rubric attempted to strike a balance between structure and substance in assessing the rigor of the CT in the learners’ essays. As shown in Table 4, the thesis and conclusion of each essay was first examined against the three levels. They were expected to appear at the end of the introductory and at the beginning of the concluding paragraphs. Each body paragraph was examined separately for the topic sentence providing the reason and the rest of the paragraph providing the supports for the reason. The clarity of the reasons, in the same way as for the theses, was divided into three levels and the soundness/acceptability of the supports was further divided into five levels. Once the results for all of the body paragraphs of an essay (mostly three with one exception of two) had been decided, they were averaged as two aggregate ratings, one for reason and the other for supports, of the claims as a whole. The eight argumentative essays were further checked for the three elements of a rebuttal: A statement of opposing views, refutation, and supports for the refutation, at three, three, and five levels respectively.

Table 4

Analysis of CT in Learners’ Essays as Judged Against a CT Rubric

Rubric for All Essays Thesis and

Conclusion

Clearly states thesis and

conclusion States thesis and conclusion Does not state thesis and conclusion

16/16 0/16 0/16

Claims

Reasons Clearly states reasons States reasons Does not state reasons

16/16 0/16 0/16 Supports for Reasons All supports are sound/acceptable and free of irrelevance. Most supports are sound/acceptable and free of irrelevance. Some supports are sound/acceptabl e and free of irrelevance. Supports are somewhat weak and irrelevant. Supports are totally irrelevant. 5/16 6/16 5/16 0/16 0/16

Additional Rubric for Argumentative Essays Opposing

Views Recognized

Clearly states opposing

point(s) of view States opposing point(s) opposing point(s) Does not state

2/8 3/8 3/8

Refutation Clearly states refutation(s) States refutation(s)

Does not state refutation(s) 2/8 4/8 2/8 Supports for Refutation All supports are sound/ acceptable and free of irrelevance. Most supports are sound/ acceptable and free of irrelevance. Some supports are sound/ acceptable and free of irrelevance. Supports are somewhat weak and irrelevant. Supports are totally irrelevant. 1/8 3/8 2/8 0/8 2/8

The results of the analysis are shown in Table 4. For the thesis and conclusion, all of the 16 essays were rated as having clear statements. For the reasons for the claims, again, all of the essays were rated as providing clear reasons. For the supports, however, five of the 16 were rated as “all supports are sound”, six were rated as “most are sound” and five as “some are sound.” None of the essays fell in the lower two categories where the supports would be rated as weak or irrelevant. While the ratings on CT for half of the 16 essays were completed at this point, the eight argumentative essays were scrutinized further for the use of rebuttal. Two of them completely ignored possible opposing views, and hence there were no follow-up refutations. One essay attempted to deal with opposing views, but failed to make a logical

statement. The other argumentative essays were mediocre in the quality of their refutations and supports, with one rated as “all supports are sound”, three as “most are sound”, and two as “some are sound.” A more detailed examination of the essays revealed that the quality of the reasoning seemed to be related to the novelty of the topics. On the more conventional topics such as the challenge against grading schemes and transfer policies, the supports were relatively more comprehensive. On the other hand, for more innovative topics, such as the campus Free Bike service, learners expressed interesting personal opinions, but did not take into consideration many other possible viewpoints.

Teacher Reflection

In general, the results indicate that the 16 essays demonstrated CT. As shown, the learners had control over essay structure, which served as the basics of CT. On the other hand, with regard to the substance of CT, i.e., the underlying logic of the supporting details, although the essays were generally sound/acceptable and free of irrelevance, there was much room for improvement. However, in considering that this essay did not take the center stage of the course in the way that the four assigned-topic essays did, and that the teacher did not prescribe what the learners should write about, and nor did she intervene with lessons or formal evaluation for this essay, the teacher/author was satisfied with the achievement of the learners. This achievement may be related to the formative assessment scheme, considering that the major parts of the design of the course remained the same. In this assessment design as shown in Table 1, CT was treated as a form of procedural knowledge to be developed in the process of giving birth to an essay, rather than a form of declarative knowledge to be explicitly taught. To summarize, the features of the design included 1) an open and inquisitive attitude modeled by the teacher at the beginning, 2) that the thought processes of all of the learner authors were open to all of the other authors, 3) multiple feedback sources, and 4) abundant time given for reflection and modification at the earlier stages of essay writing.

First, notice that the teacher was the first feedback provider, after which she no longer involved herself, but monitored the process in the later five stages. At the inception when the learners had just proposed what they wanted to write about, it was an appropriate time for the teacher to model a positively inquisitive attitude. Initial learner ideas were responded to with confirmation,

questions, challenges, and cautions on what might sound illogical or what might cause problems if the ideas were to be further developed. These comments were made public to all of the members of the class on the Moodle discussion forum. The learners did the same thing because they were all required to comment on peers in a similar way. After Stage 1, the teaching assistant was instructed by the teacher to provide comments at Stages 2 and 3 when the essay outlines were presented. This arrangement reinforced the healthy class atmosphere of inquiry and reiterated to students that the teacher was not the single authority and that sound CT involved constant reflection.

Secondly, in addition to teacher feedback, all of the peer feedback was open to all of the students on the course e-platform. A learner shared his/her essay ideas, read others’, provided feedback to some of them, and received feedback from the teacher, the teaching assistant, and quite a few peers. While each of the students worked on a different topic, this gave them a chance to see a variety of ideas and structures being formulated and challenged. The points of concern for each essay may not have been the same, but they all served as catalysts in stimulating the learners to think more critically. Unlike most traditional feedback, which is either unidirectional and serves the purpose of one feedback recipient only or is given as collective feedback that may sacrifice individual needs, this arrangement catered to the needs of each learner and wasted no feedback resources.

Third, two different sources of feedback were deliberately arranged for each of the six stages. Because the feedback came from various sources, some conflict over opinions was inevitable, and this further nurtured CT. Learners were advised to assess the feedback and make their own decisions. By playing the role of a feedback provider in addition to being an author, each learner was involved in not only his/her own but also other students’ work in the first three stages when ideas were being generated and modified. At Stage 5, after the essays had been revised once by the author, the learners had a chance to perform extensive peer review in groups, collectively examining one aspect of the essays at a time. This, again, was an opportunity for more stimulation and reflection before learners made their own final revisions. In addition to all of the course members being feedback providers, the design arranged for outside opinions to be sought at Stage 4 when the first draft had just been completed. The Writing Center tutors, as peer experts in EFL writing, were not involved in the class activities and thus served as ideal sources of external perspectives. Eventually, after the learners had been prepared through their experience of the first three stages of giving feedback to peers, they started to shoulder more

responsibility in performing self checks on the various drafts and provided feedback to themselves.

Finally, a special feature of this design was the ample time given to the learners for reflection on the feedback, especially in the first three stages when they had not yet started drafting their essay. Between Stage 1 of generating ideas and Stage 2 of drafting the general outlines, there were four weeks for learners to ponder on the feedback they had received; between Stage 2 and Stage 3 there were three more weeks to proceed from general to detailed outlines. This format is not typical in most EFL writing assignments, and perhaps not so either in most other classroom assignments, in which learners are usually expected to respond to feedback without much delay. Previous assessment and feedback studies generally advise teachers to give learners timely feedback (Shute, 2008), because the effect of the feedback may diminish as time passes by and memory fades away. But learner response time to feedback has not seemed to emerge as an issue for research so far. Common wisdom would probably follow the same pattern of expectation for teacher feedback and prescribe that learners respond immediately. This may be true with most other kinds of academic tasks, but in the case of CT, novice writers and critical thinkers may need to be given the luxury of more time. The factors involved in the consideration of the timing for response to feedback may require more studies.

In conclusion, this action research demonstrated a practical design in which formative assessment and feedback were arranged to foster CT as learners organized ideas and drafted their essays. To nurture CT, learners were first given freedom in choosing their topics. This feature was based on Stapleton’s (2001) finding that CT was more evident in topics that learners are familiar with. Second, the design was mainly concerned with processes rather than content. This was drawn from de Sanchez’s (1995) notion that CT instruction should focus on the processes that underlie complex and reasoned thoughts. Moreover, various strategies that have been shown to be facilitative to teaching CT, such as discussion, questioning, verbalization, and problem solving (Karabulut, 2012; King, 1995; McKeachie et al., 1986) were incorporated at the different stages of assessment and feedback when the learners engaged actively as providers of feedback themselves. At the same time, scaffolds in the form of feedback came from the teacher, teaching assistant, Writing Center tutors, and peers. As counter-evidence to Atkinson (1997), these EFL essays were the results of teaching CT to students who grew up in the Asian culture of Taiwan. Like their Japanese counterparts

(Stapleton, 2001, 2002), these students voiced their opinions and tried to express them in an organized manner using a language they have yet to master.

Finally, the study showcased a midpoint of feedback provision between teacher telling and the seemingly too idealistic state of learner actively seeking (Boud & Molloy, 2012). Before learners become independent and know when and how to ask for feedback, the teacher has other choices than being a Cinderella who laboriously and ineffectively furnishes feedback that learners may not read, understand, appreciate, or act upon. Instead, the teacher could become the conductor of a symphony, who orchestrates all of the available resources and plans the procedures that would occur in the learning process, to stimulate the classroom learners to act, think, reflect, and provide feedback to each other. The power of feedback has been proven to be considerable and is certainly something that researchers could explore more.

Acknowledgement

This paper was supported by Research Grant MOST103-2410-H-004-080 from the Ministry of Science and Technology. The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and editors whose insightful comments helped improve the paper. Thanks also go to Mr. Hengming Kang, my teaching and research assistant. His wonderful support during the design and development of this action research was highly valuable and treasured.

References

Atkinson, D. (1997). A critical approach to critical thinking in TESOL. TESOL

Quarterly, 31(1), 71-94.

Angelo, T. A. (1995). Classroom assessment for critical thinking. Teaching of

Psychology, 22(1), 6-7.

Bailey, R., & Garner, M. (2010). Is the feedback in higher education assessment worth the paper it is written on? Teachers’ reflection on their practices. Teaching in

Higher Education, 15(2), 187-198.

Bensley, D. A., & Haynes, C. (1995). The acquisition of general purpose strategic knowledge for argumentation. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 41-45.

Bensley, D. A., & Murtagh, M. P. (2012). Guidelines for a scientific approach to critical thinking assessment. Teaching of Psychology, 39(1), 5-16.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment.

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2012). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: The challenge of design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 698-712.

Cavdar, G., & Doe, S. (2012). Learning through writing: Teaching critical thinking skills in writing assignments. Political Science & Politics, 45(2), 298-306. Cooper, J. L. (1995). Cooperative learning and critical thinking. Teaching of

Psychology, 22(1), 7-9.

de Sanchez, M. A. (1995). Using critical-thinking principles as a guide to college-level instruction. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 72-74.

Engin, M. (2013). Trainer talk: Levels of intervention. ELT Journal, 67(1), 11-19. Folse, K. S., Muchmore-Vokoun, A., & Solomon, E. V. (2010). Great writing 4: Great

essays (3rd ed.). Independence, KY: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Fung, D. (2014). Promoting critical thinking through effective group work: A teaching intervention for Hong Kong primary school students. International Journal of

Educational Research, 66, 45-62.

Goodwin, B. (2014). Teach critical thinking to teach writing. Educational Leadership,

April, 78-80.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American

Psychologist, 53(4), 449-455.

Halpern, D. F., & Nummedal, S. G. (1995). Closing thoughts about helping students improve how they think. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 82-83.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational

Research, 77(1), 81-112.

Huang, S.-C. (2012). Like a bell responding to a strikerInstruction contingent on assessment. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 11(4), 99-119.

Huang, S.-C. (2016). No longer a teacher monologueInvolving EFL writing learners in teachers’ assessment and feedback processes. Taiwan Journal of TESOL, 16(1), 1-31.

Karabulut, U. S. (2012). How to teach critical-thinking in social studies education: An examination of three NCSS journals. Egitim Arastirmalari-Eurasian Journal of

Educational Research, 49(12), 197-214.

King, A. (1995). Inquiring minds really do want to know: Using questioning to teach critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 13-17.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues,

2(4), 34-46.

Liu, F., & Stapleton, P. (2014). Counterargumentation and the cultivation of critical thinking in argumentative writing: Investigating washback from a high-stakes test.

System, 45, 117-128.

McKeachie, W., Pintrich, P., Lin, Y., & Smith, D. (1986). Teaching and learning in

the college classroom: A review of the research literature. Ann Arbor, MI:

National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning. Miri, B., David, B. C., & Uri, Z. (2007). Purposely teaching for the promotion of

higher-order thinking skills: A case of critical thinking. Research in Science

Orsmond, P., & Merry, S. (2011). Feedback alignment: Effective and ineffective links between tutors’ and students’ understanding of coursework feedback. Assessment

& Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(2), 125-136.

Orsmond, P., & Merry, S. (2013). The importance of self-assessment in students’ use of tutors’ feedback: A qualitative study of high and non-high achieving biology undergraduates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(6), 737-753. Oshima, A., & Hogue, A. (2006). Writing academic EnglishLevel 4(4th ed.). White

Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., & O’Donovan, B. (2010). Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), 277-289.

Quitadamo, I. J., & Kurtz, M. J. (2007). Learning to improve: Using writing to increase critical thinking performance in general education biology. CBELife

Sciences Education, 6(2), 140-154.

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with action research. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Sampson, V., & Clark, D. B. (2008). Assessment of the ways students generate arguments in science education: Current perspectives and recommendations for future directions. Science Education, 92(3), 447-472.

Shute, V. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research,

78(1), 153-189.

Stapleton, P. (2001). Assessing critical thinking in the writing of Japanese university studentsInsights about assumptions and content familiarity. Written

Communication, 18(4), 506-548.

Stapleton, P. (2002). Critical thinking in Japanese L2 writing: Rethinking tired constructs. ELT Journal, 56(3), 250-257.

Stapleton, P., & Wu, Y. (2015). Assessing the quality of arguments in students’ persuasive writing: A case study analyzing the relationship between surface structure and substance. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 17, 12-23. Sziarto, K. M., McCarthy, L., & Padilla, N. L. (2014). Teaching critical thinking in

world regional geography through stakeholder debate. Journal of Geography in

Higher Education, 38(4), 557-570.

Toulmin, S. (2003). The use of argument (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Wade, C. (1995). Using writing to develop and assess critical thinking. Teaching of

Psychology, 22(1), 24-28.

Wingate, U. (2010). The impact of formative feedback on the development of academic writing. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 519-533. Yang, Y.-T. C. (2008). A catalyst for teaching critical thinking in a large university

class in Taiwan: Asynchronous online discussions with the facilitation of teaching assistants. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 56(3), 241-264.

Appendix. Topics and content of the 16 learner essays

Essay Topics Brief Descriptions

1 Why should college students move out from home? Advising younger students to move out from home and become independent

2 Home or dorm? More objectively comparing living at home vs. living in the dormitory

3 Finding the right way Giving three pieces of advice for students who are not interested in their majors

4 Master’s degree, should I? graduate should pursue a master’s degree Stating three reasons for why a college

5 Not just depending on scores GPA is the dominant criterion for approving Arguing against the current policy in which

students’ change of majors 6

Should class attendance be counted into students’ academic

performance?

Arguing against many teachers’ grading practice in which class attendance is part of

academic performance

7 single-sex dorms rather than co-ed Why XXU should support

dorms

Arguing against the current co-ed dorm experiment by pointing out problems and

refuting opposing views

8 Is the XXU Free Bike system a good idea? Arguing why the author believed this new benign policy would not work

9

Whether XXU’s College of Communication freshmen should

have undeclared majors

Arguing against the new college policy of having undeclared majors in the freshman

and sophomore years

10 Why study economics? Explaining three underlying benefits

11

The comparison of real estate appraisal between the U.S. and

Taiwan

Explaining why and how the same real estate appraisal industry differ in the two countries

12 Why a civil law system Explaining why Taiwan follows the civil law system

13 The reasons you should not major in XXX in XXU Analyzing the curriculum problems in the author’s department

14 Do you “Facebook”? Explaining the benefits of using Facebook and arguing that everyone should use it

15 Why is online shopping getting popular nowadays? Offering three reasons to explain the phenomenon