Is schizophrenia associated with an

increased risk of chronic kidney disease?

A nationwide matched-cohort study

Nian-Sheng Tzeng,1,2Yung-Ho Hsu,3Shinn-Ying Ho,4,5Yu-Ching Kuo,4 Hua-Chin Lee,4Yun-Ju Yin,4Hong-An Chen,4Wen-Liang Chen,5

William Cheng-Chung Chu,6Hui-Ling Huang4,5

To cite: Tzeng N-S, Hsu Y-H, Ho S-Y,et al. Is

schizophrenia associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease? A nationwide matched-cohort study.BMJ Open 2015;5:e006777. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006777

▸ Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ bmjopen-2014-006777). Received 29 September 2014 Accepted 6 January 2015

For numbered affiliations see end of article.

Correspondence to

Dr Hui-Ling Huang; hlhuang@mail.nctu.edu.tw

ABSTRACT

Objective:The impact of schizophrenia on vital diseases, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD), has not as yet been verified. This study aims to establish whether there is an association between schizophrenia and CKD.

Design:A nationwide matched cohort study.

Setting:Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database.

Participants:A total of 2338 patients with schizophrenia, and 7014 controls without schizophrenia (1:3), matched cohort for sex, age group, geography, urbanisation and monthly income, between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2007, based on the International Classifications of Disease Ninth Edition (ICD-9), Clinical Modification codes.

Primary and secondary outcome measures:After making adjustments for confounding risk factors, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare the risk of developing CKD during a 3-year follow-up period from the index date.

Results:Of the 2338-subject case cohort, 163 (6.97%) developed a CKD, as did 365 (5.20%) of the 7014 control participants. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed that patients with schizophrenia were more likely to develop CKD (HR=1.36, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.63; p<0.001). After adjusting for gender, age group, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, heart disease and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) usage, the HR for patients with schizophrenia was 1.25 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.50; p<0.05). Neither typical nor atypical antipsychotics was associated an increased risk of CKD in patients with schizophrenia.

Conclusions:The findings from this population-based retrospective cohort study suggest that schizophrenia is associated with a 25% increase in the risk of developing CKD within only a 3-year follow-up period.

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia, a chronic mental illness, has an approximately 1% lifetime prevalence in the global population,1 which results in

marked behavioural disturbances and func-tional impairment.2 A higher risk for dia-betes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and consequent cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases has been noted in patients with schizophrenia, along with a higher mortality related to these diseases—as much as two to three times higher in comparison with the general population.3

However, whether other health problems, such as CKD, are related to schizophrenia is less discussed. A higher prevalence of CKD was found in developed countries, and identified risk factors include diabetes mellitus, hyperten-sion and the use of various medications.4Other medical or mental illnesses that could be con-tributing to CKD remain unknown.

The Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Dataset (NHIRD) was used to estab-lish whether there is an association between schizophrenia and CKD during a subsequent 3-year follow-up period, from the index date. The National Health Insurance (NHI) Programme was initiated in Taiwan in 1995, and as of June 2009 there were 22 928 190 people enrolled, exceeding 99% of Taiwan’s population, who contracted with 97% of the medical providers in Taiwan.5 The diagnostic

Strengths and limitations of this study ▪ To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

published study to investigate the risk of patients with schizophrenia with chronic kidney disease (CKD) based on the population database. ▪ In a nationwide, matched cohort study, the

selection bias could be minimised.

▪ Misclassification of diseases might exist in such claim data on the basis of the International Classifications of Disease Ninth Edition (ICD-9), Clinical Modification codes.

▪ A longer follow-up is needed to clarify the long-term risk for patients with schizophrenia devel-oping CKD in this population.

coding used for the NHI is according to the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic criteria.6 Each diag-nosis of schizophrenia or CKD was made by board-certified psychiatrists or nephrology specialists, and psychi-atric experts from the Bureau of National Health Insurance randomly review the charts of 1 per 100 ambula-tory cases, and 1 per 20 inpatient claimed cases, in order to verify the accuracy of the diagnosis.7In addition, several Taiwan studies have demonstrated the high accuracy and validity of the diagnoses in the NHIRD.8–10

METHODS Database

This study used the NHIRD, which is released by the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) programme. The NHIRD is open to scientists for research purposes and covers 99% of Taiwan’s 23 million citizens. The research used the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID 2005), which consists of all the original claims data of one million beneficiaries selected from the total registry in 2005 for the analyses. There were no statistically significant differences in age and sex between the LHID and all enrollees. In order to protect individual privacy, the identities of individuals included in this database were all encrypted. The NHI medical claims database includes ambulatory care, inpatient care, outpatient care and prescription drugs.

Patients’ diagnoses are coded using the ‘International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification’ (ICD-9-CM).

Study population

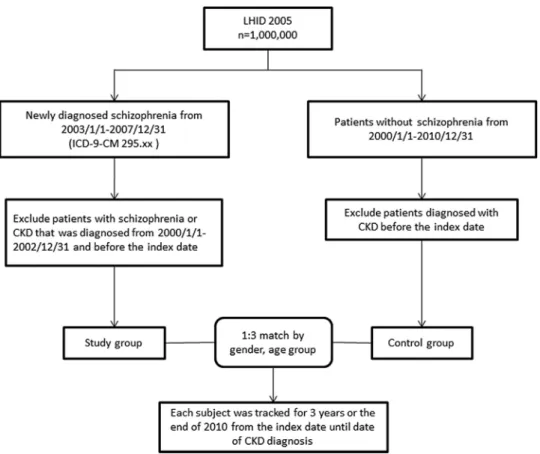

We identified adult (≥18 years) patients with a first-time diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.xx) between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2007. Patients with schizophrenia or CKD (ICD-9-CM 580, 581, 582, 583, 584, 585, 586, 587, 588, 589, 753, 403, 404, 2504, 2741, 4401, 4421, 4473, 5724, 6421 or 6462) before the index date were further excluded. The initial diagnosis date was defined as the index date of entry into the schizophrenia cohort (figure 1). In Taiwan, the diagnosis of CKD follows the criteria of‘Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)’. CKD is defined as kidney damage as albumin-to-creatinine ratio >30 mg/g in two of three spot urine specimens, or glomerularfiltration rate (GFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, for 3 months or more, irrespective of the cause.11

During 2003–2007, the NHIRD database used included 2338 patients with schizophrenia. We identified one such control patient with the most similar demographic characteristics. Covariates included gender, age group (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ≥70 years), geo-graphical areas (north, central, south and east of Taiwan), urbanisation level (level 1–4) and monthly income groups (NTD; <18 000, 18 000–34 999, ≥35 000). The urbanisation of a patient’s home city was defined by

population and certain indicators of the city’s level of development. Level 1 urbanisation was defined as having a population greater than 1 250 000 people, and a spe-cific status of political, economic, cultural and metropol-itan development. Level 2 urbanisation was defined as having a population between 500 000 and 1 250 000, and an important role in Taiwan’s political system, economy and culture. Urbanisation levels 3 and 4 were defined as having a population between 150 000 and 500 000 and a population less than 150 000, respectively.12

After matching, 7014 were found to be without schizo-phrenia (1:3) among a total of 9352 sampled patients. All patients were followed up within 3 years or those diagnosed with CKD. Comorbidities included diabetes (ICD-9-CM 250, 250.33), hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401.1, 401.9, 402.10, 402.90, 404.10, 404.90, 405.1, 405.9), hyperlipidaemia (ICD-9-CM 272.x), obesity (ICD-9-CM 278), heart disease (ICD-9-CM 410–429) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) usage.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft SQL Server 2008 software was used for data man-agement and analysis. All statistical methods were per-formed using the Statistical Analysis Systems software package (Release 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A two-sided p value with less than 0.05 was consid-ered statistically significant. The χ2test was used to analyse data for categorical variables including gender, age group, geography, urbanisation level, monthly income, comorbid-ities and NSAIDs usage from the data set prescription records. Multivariate analysis was conducted using Cox pro-portional hazards regression models to estimate the effects of risk factors on the HRs, and the 95% CI, for CKD.13

RESULTS

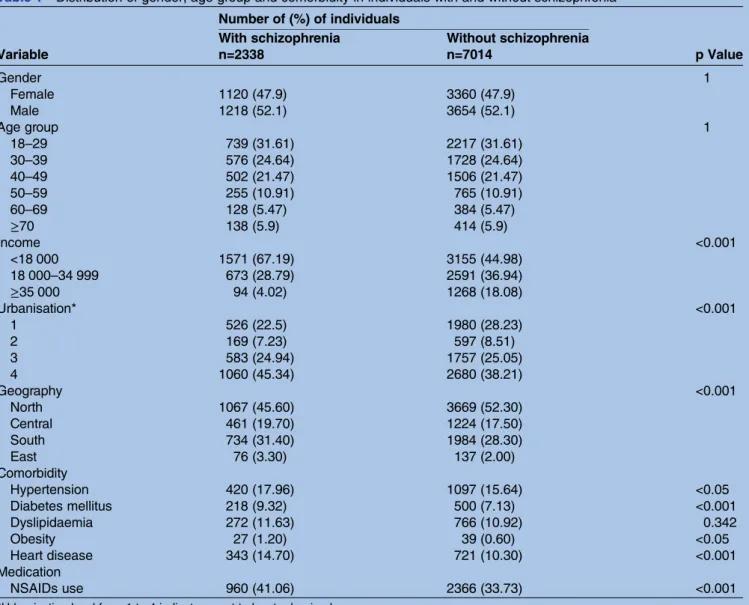

We identified 2338 patients with schizophrenia, and 7014 without schizophrenia, among a total of 9352 sampled patients by using 1:3 matched. Table 1 shows

Table 1 Distribution of gender, age group and comorbidity in individuals with and without schizophrenia Number of (%) of individuals

p Value With schizophrenia Without schizophrenia

Variable n=2338 n=7014 Gender 1 Female 1120 (47.9) 3360 (47.9) Male 1218 (52.1) 3654 (52.1) Age group 1 18–29 739 (31.61) 2217 (31.61) 30–39 576 (24.64) 1728 (24.64) 40–49 502 (21.47) 1506 (21.47) 50–59 255 (10.91) 765 (10.91) 60–69 128 (5.47) 384 (5.47) ≥70 138 (5.9) 414 (5.9) Income <0.001 <18 000 1571 (67.19) 3155 (44.98) 18 000–34 999 673 (28.79) 2591 (36.94) ≥35 000 94 (4.02) 1268 (18.08) Urbanisation* <0.001 1 526 (22.5) 1980 (28.23) 2 169 (7.23) 597 (8.51) 3 583 (24.94) 1757 (25.05) 4 1060 (45.34) 2680 (38.21) Geography <0.001 North 1067 (45.60) 3669 (52.30) Central 461 (19.70) 1224 (17.50) South 734 (31.40) 1984 (28.30) East 76 (3.30) 137 (2.00) Comorbidity Hypertension 420 (17.96) 1097 (15.64) <0.05 Diabetes mellitus 218 (9.32) 500 (7.13) <0.001 Dyslipidaemia 272 (11.63) 766 (10.92) 0.342 Obesity 27 (1.20) 39 (0.60) <0.05 Heart disease 343 (14.70) 721 (10.30) <0.001 Medication NSAIDs use 960 (41.06) 2366 (33.73) <0.001

*Urbanisation level from 1 to 4 indicates most to least urbanised. NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

the distributions of demographic characteristics and medical comorbidities among patients with and without schizophrenia in Taiwan. Schizophrenia occurred more frequently in the age group of 18–29 years (31.61%) than in the other five groups. Patients with schizophre-nia generally had a lower economic status (67.19%), urbanisation level (45.34%) and lived in the north (45.60%). A comparison with controls revealed that patients with schizophrenia were more likely to have the comorbidities of diabetes mellitus (9.32 vs 7.13%, p<0.001), hypertension (17.96% vs 15.64%, p<0.05) and hyperlipidaemia (11.63% vs 10.92%, p<0.05). Patients with schizophrenia were more likely to take NSAIDs (41.06% vs 33.73%, p<0.001).

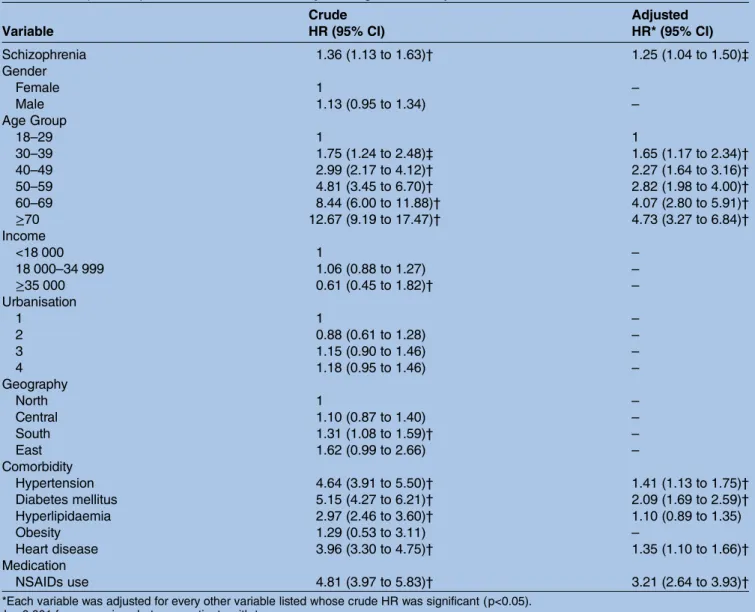

During the 3-year follow-up period, 528 (3.21%) of the 9352 study patients experienced CKD, including 163 patients in the schizophrenia group and 365 patients in controls. The stratified Cox proportional hazard analysis showed that the schizophrenia group had a crude HR 1.36 times greater than that of the comparison group (95% CI 1.13 to 1.63; p<0.001;table 2).

Figure 2depicts the CKD-free survival curves obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method, and shows that patients with schizophrenia had a significantly lower 3-year CKD-free survival than those without (log rank test, p<0.05). There was a significant difference in the CKD distribution between these two cohorts in the 3-year follow-up. The incidence rate ( per 1000 person-years) of CKD for patients with schizophrenia (25.13) was higher than that for non-schizophrenic controls (18.60).

After adjusting the age group, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, heart disease and NSAIDs usage, the Cox regression analysis showed that the elderly (HR=4.73; 95% CI 3.27 to 6.84; p<0.001), hyper-tension (HR=1.41; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.75, p<0.001), dia-betes mellitus (HR=2.09; 95% CI 1.69 to 2.59; p<0.001), heart disease (HR=1.35; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.66, p<0.001) and NSAIDs usage (HR=3.21; 95% CI 2.64 to 3.93; p<0.001); the HR for patients with schizophrenia was 1.25 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.50; p<0.05). Most notably, patients with schizophrenia were found to be of an increased risk for the development of CKD, such as dia-betes mellitus and the use of NSAIDs (table 3).

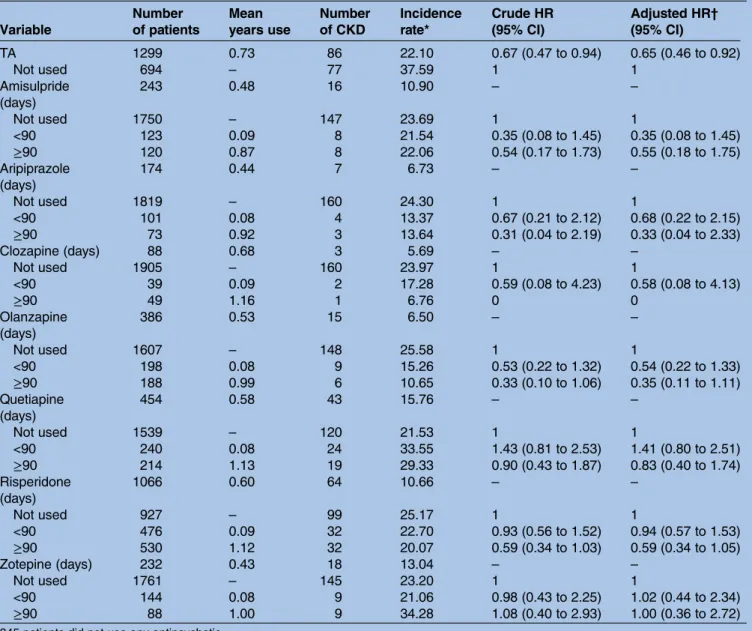

All the 2338 patients with schizophrenia with treatment of antipsychotics were assessed during the 3 years from the diagnosis index date. There are 10 typical antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, clopenthixol, clothiapine, flupentixol, haloperidol, loxapine, pimozide, sulpiride, thioridazine and trifluoperazine) and seven atypical antipsychotics (amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetia-pine, risperidone and zotepine). Of the patients with schizophrenia, 808 (34.56%) were treated with a single antipsychotic, 1185 (50.68%) were treated with two or more different antipsychotics, and 345 (14.76%) were treated without any antipsychotics. As shown intable 4, the patients with schizophrenia using different antipsychotics are stratified by the total number of days the antipsychotics were used (never used, <90 or ≧90 days). After adjusting for hypertension and diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and heart disease, neither typical antipsychotics nor atyp-ical antipsychotics increased the risk of CKD.

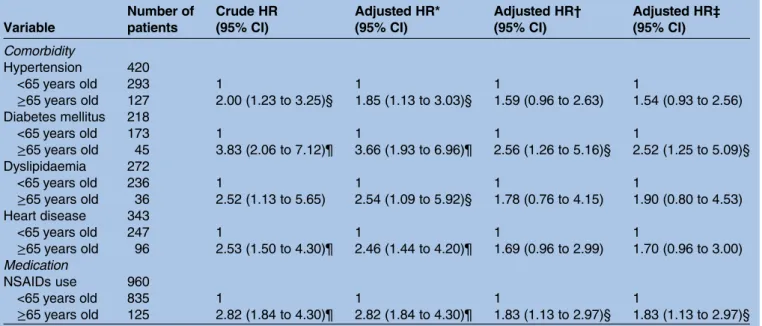

About 40% (41.06%, N=960) of the patients used any NSAIDs in the schizophrenia group, and 2366 (33.73%) used NSAIDs in the control group. The average prescrip-tion days of NSAIDs were 29 in the schizophrenia group and 30 in the control group. The patients with schizo-phrenia were stratified by comorbidities and NSAIDs usage in patients older than 65 years. After adjusting for NSAIDs usage, the patients had a higher HR in this group, as shown intable 5.

DISCUSSION

After adjusting for demographic characteristics, select comorbid medical disorders and NSAIDs usage, the

Table 2 Individuals with and without schizophrenia as predictors of CKD identified by Cox regression

Variable Number (%) of individuals Schizophrenia Non-schizophrenia n=2338 n=7014 With CKD 163 (6.90) 365 (5.20) Without CKD 2175 (93.10) 6649 (94.80) Incidence rate* 25.13 18.6 Crude HR 1.36 (1.13 to 1.63)† *Incidence rate: per 1000 person-years.

†p<0.001 for comparison between patients with two groups. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Figure 2 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) free survival for patients with schizophrenia (---) and patients without

schizophrenia (–) during the 3-year follow-up period in Taiwan from the index date.

current results reveal that patients with schizophrenia have an increased risk of nearly 40% (HR=1.36; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.63; p<0.001) of developing CKD within a 3-year follow-up period after their schizophrenia diagnosis, as compared with that of the matched non-schizophrenic controls. There was a significant difference in the CKD distribution between these two cohorts in the 3-year follow-up period. This tendency was more evident since the enrolled patients with schizophrenia were newly diagnosed and had no previous history of CKD. No sex difference in the risk of developing CKD was found. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no previous studies showing this risk for the development of CKD. Since the Kaplan-Meier method revealed that patients with schizophrenia had a significantly lower 3-year CKD-free survival than those without schizophrenia, and it takes 540 days (18 months) to achieve a significantly adjusted HR (data not shown), hence 3 years proved to

be a reasonable period to follow the newly-diagnosed patients with schizophrenia.

In the study population, the group with schizophrenia consisted of patients who were first entered into the record with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, with over 70% of this group being 30 years of age and/or older, which is beyond the typical age of the onset of schizophrenia, being that of males 18–25 years of age, and females 20– 35 years of age.14 15This disparity may be due to the fact that people with mental disorders tend to start searching for help from folk belief healers or their primary care physicians, such as internists or family physicians, before they visit a psychiatrist in Taiwan.16However, most of the Taiwanese folk belief healers provide shamanistic ritual treatment,17 religious consultations18 or support to patients and caregivers from their faith groups,19 as well as to those patients with schizophrenia who seek their help, instead of medications.

Table 3 Independent predictors of CKD identified by Cox regression analysis Variable Crude HR (95% CI) Adjusted HR* (95% CI) Schizophrenia 1.36 (1.13 to 1.63)† 1.25 (1.04 to 1.50)‡ Gender Female 1 – Male 1.13 (0.95 to 1.34) – Age Group 18–29 1 1 30–39 1.75 (1.24 to 2.48)‡ 1.65 (1.17 to 2.34)† 40–49 2.99 (2.17 to 4.12)† 2.27 (1.64 to 3.16)† 50–59 4.81 (3.45 to 6.70)† 2.82 (1.98 to 4.00)† 60–69 8.44 (6.00 to 11.88)† 4.07 (2.80 to 5.91)† ≥70 12.67 (9.19 to 17.47)† 4.73 (3.27 to 6.84)† Income <18 000 1 – 18 000–34 999 1.06 (0.88 to 1.27) – ≥35 000 0.61 (0.45 to 1.82)† – Urbanisation 1 1 – 2 0.88 (0.61 to 1.28) – 3 1.15 (0.90 to 1.46) – 4 1.18 (0.95 to 1.46) – Geography North 1 – Central 1.10 (0.87 to 1.40) – South 1.31 (1.08 to 1.59)† – East 1.62 (0.99 to 2.66) – Comorbidity Hypertension 4.64 (3.91 to 5.50)† 1.41 (1.13 to 1.75)† Diabetes mellitus 5.15 (4.27 to 6.21)† 2.09 (1.69 to 2.59)† Hyperlipidaemia 2.97 (2.46 to 3.60)† 1.10 (0.89 to 1.35) Obesity 1.29 (0.53 to 3.11) – Heart disease 3.96 (3.30 to 4.75)† 1.35 (1.10 to 1.66)† Medication NSAIDs use 4.81 (3.97 to 5.83)† 3.21 (2.64 to 3.93)†

*Each variable was adjusted for every other variable listed whose crude HR was significant (p<0.05). †p<0.001 for comparison between patients with two groups.

‡p<0.05 for comparison between patients with two groups. NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The disadvantaged socioeconomic status and psychotic symptoms present in patients with schizophrenia can also result in poor food choices.20 In the non-schizophrenic population, many with chronic illnesses, their treatments and even their medications usage can also contribute to the development of CKD: for example, comorbidity with diabetes mellitus, auto-immune diseases or nephritis; use of some nephrotoxic drugs21; or unhealthy lifestyles, obesity and the meta-bolic syndrome.22Therefore, unhealthy diets of low-fibre food, smoking habits, lack of exercise, disadvantaged socioeconomic status and metabolic syndrome may also contribute to the development of CKD among patients with schizophrenia.

Another potential interpretation could be that once individuals are diagnosed with schizophrenia, they are

then subjected to closer medical attention, thus making diagnosis with CKD more likely. However, results varied about the study of frequency in the help-seeking beha-viours of patients with schizophrenia or contacts with their general practitioners.23 24 Therefore, further study is needed to understand utilisations of preventive somatic diseases screening of patients with schizophrenia.

From the biological viewpoint, some previous studies have shown that endothelial dysfunction is common to the pathogenesis of DM, hypertension and hyperlipid-aemia,22 and also that endothelial dysfunction is an underlying pathophysiological condition of CKD.25 Alteration of the endothelial function, as shown in one prior study, plays a role in patients withfirst-onset schizo-phrenia26 another study revealed that some pharmaco-genetic variability regarding folate and homocysteine

Table 4 The HR of CKD in patients with schizophrenia in relation to antipsychotics use during the 3-year follow-up period Variable Number of patients Mean years use Number of CKD Incidence rate* Crude HR (95% CI) Adjusted HR† (95% CI) TA 1299 0.73 86 22.10 0.67 (0.47 to 0.94) 0.65 (0.46 to 0.92) Not used 694 – 77 37.59 1 1 Amisulpride (days) 243 0.48 16 10.90 – – Not used 1750 – 147 23.69 1 1 <90 123 0.09 8 21.54 0.35 (0.08 to 1.45) 0.35 (0.08 to 1.45) ≥90 120 0.87 8 22.06 0.54 (0.17 to 1.73) 0.55 (0.18 to 1.75) Aripiprazole (days) 174 0.44 7 6.73 – – Not used 1819 – 160 24.30 1 1 <90 101 0.08 4 13.37 0.67 (0.21 to 2.12) 0.68 (0.22 to 2.15) ≥90 73 0.92 3 13.64 0.31 (0.04 to 2.19) 0.33 (0.04 to 2.33) Clozapine (days) 88 0.68 3 5.69 – – Not used 1905 – 160 23.97 1 1 <90 39 0.09 2 17.28 0.59 (0.08 to 4.23) 0.58 (0.08 to 4.13) ≥90 49 1.16 1 6.76 0 0 Olanzapine (days) 386 0.53 15 6.50 – – Not used 1607 – 148 25.58 1 1 <90 198 0.08 9 15.26 0.53 (0.22 to 1.32) 0.54 (0.22 to 1.33) ≥90 188 0.99 6 10.65 0.33 (0.10 to 1.06) 0.35 (0.11 to 1.11) Quetiapine (days) 454 0.58 43 15.76 – – Not used 1539 – 120 21.53 1 1 <90 240 0.08 24 33.55 1.43 (0.81 to 2.53) 1.41 (0.80 to 2.51) ≥90 214 1.13 19 29.33 0.90 (0.43 to 1.87) 0.83 (0.40 to 1.74) Risperidone (days) 1066 0.60 64 10.66 – – Not used 927 – 99 25.17 1 1 <90 476 0.09 32 22.70 0.93 (0.56 to 1.52) 0.94 (0.57 to 1.53) ≥90 530 1.12 32 20.07 0.59 (0.34 to 1.03) 0.59 (0.34 to 1.05) Zotepine (days) 232 0.43 18 13.04 – – Not used 1761 – 145 23.20 1 1 <90 144 0.08 9 21.06 0.98 (0.43 to 2.25) 1.02 (0.44 to 2.34) ≥90 88 1.00 9 34.28 1.08 (0.40 to 2.93) 1.00 (0.36 to 2.72)

345 patients did not use any antipsychotic. *Incidence rate: per 1000 person-years

†Each variable was adjusted for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and heart disease. ‡p<0.05 for comparison between patients with two groups.

metabolism may also increase endothelial dysfunction risk in patients with schizophrenia using atypical antipsy-chotics.27 There is a statistically significant increase in the risk of CKD in patients with schizophrenia, and a possible common pathway involving an alteration of the endothelial function should be explored in further research.

Patients with schizophrenia need a long duration of, or even lifelong, antipsychotic treatment. Therefore, the association between antipsychotic use and CKD in patients with schizophrenia has been discussed in this study. We therefore found that there is no specific associ-ation between antipsychotic treatment and CKD when controlling for comorbidity with hypertension and dia-betes mellitus.

Using NSAIDs is a well-known risk factor for CKD.28 Several nationwide population-based studies showed that the use of NSAIDs in Taiwan’s residents was generally around 40–50%, and could be up to 95% in some popu-lations.29–31In a previous study, patients with schizophre-nia were found to have the well-known phenomenon of pain insensitivity, or hypoalgesia, but its impact on their general health is unclear.32 Some authors argue that patients with schizophrenia do have chronic pain.33 However, the current findings suggest that the percent-age of patients with schizophrenia with any previous NSAIDs usage is higher than that of the non-schizophrenia group, and therefore this phenomenon needs further study. In our study, patients with schizo-phrenia who had used NSAIDs had a higher HR (3.21, 95% CI 2.64 to 3.93; p<0.001) in comparison to the

control group. In the group of patients with schizophre-nia, those with any NSAIDs usage had a higher adjusted HR than patients not receiving NSAIDs (HR=2.13; 95% CI 1.51 to 3.02; p<0.001). Therefore, schizophrenia pre-sents an increased risk for CKD, and the use of NSAIDs seems to have some synergistic effects for this mounting risk in these patients.

Current guidelines recommend the regular monitor-ing of metabolic risk in people treated with anti-psychotic medication, such as fasting glucose, body mass index, fasting triglycerides, fasting cholesterol, girth, high-density/low-density lipoprotein, blood pressure and symptoms of diabetes.34 From the aspects of cost-effectiveness, screening combined blood urine nitrogen and creatinine tests in patients with schizophrenia once a year would cost about NT$80 (New Taiwan dollars), equivalent to US$2.67 per patient-year, as compared to haemodialysis US$1325 per patient-year for patients without diabetes with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and $4677 per patient-year for patients with diabetes with ESRD in Taiwan. These tests would allow physicians to initiate early prevention for patients with schizophre-nia who are at risk of developing CKD.35 However, further study is required to evaluate the benefits of screening CKD in patients with schizophrenia.

Studies using insurance claims data have some limita-tions: patients with CKD have been detected, but the severity and outcomes are not clear in such a data set. The antipsychotic dose, degree of smoking and alcohol use, dietary habits and the amount of NSAID or other analgesics, such as acetaminophen usage, are not known

Table 5 The HR of CKD in 2338 patients with schizophrenia for comorbidities and NSAIDs use during the 3-year follow-up period Variable Number of patients Crude HR (95% CI) Adjusted HR* (95% CI) Adjusted HR† (95% CI) Adjusted HR‡ (95% CI) Comorbidity Hypertension 420 <65 years old 293 1 1 1 1 ≥65 years old 127 2.00 (1.23 to 3.25)§ 1.85 (1.13 to 3.03)§ 1.59 (0.96 to 2.63) 1.54 (0.93 to 2.56) Diabetes mellitus 218 <65 years old 173 1 1 1 1 ≥65 years old 45 3.83 (2.06 to 7.12)¶ 3.66 (1.93 to 6.96)¶ 2.56 (1.26 to 5.16)§ 2.52 (1.25 to 5.09)§ Dyslipidaemia 272 <65 years old 236 1 1 1 1 ≥65 years old 36 2.52 (1.13 to 5.65) 2.54 (1.09 to 5.92)§ 1.78 (0.76 to 4.15) 1.90 (0.80 to 4.53) Heart disease 343 <65 years old 247 1 1 1 1 ≥65 years old 96 2.53 (1.50 to 4.30)¶ 2.46 (1.44 to 4.20)¶ 1.69 (0.96 to 2.99) 1.70 (0.96 to 3.00) Medication NSAIDs use 960 <65 years old 835 1 1 1 1 ≥65 years old 125 2.82 (1.84 to 4.30)¶ 2.82 (1.84 to 4.30)¶ 1.83 (1.13 to 2.97)§ 1.83 (1.13 to 2.97)§ *Adjusted HR Adjusted for NSAIDs use.

†Adjusted HR Adjusted for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and heart disease.

‡Adjusted HR Adjusted for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, heart disease and NSAIDs use. §p<0.05 for comparison between patients with two groups.

¶p<0.001 for comparison between patients with two groups. NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

in the health data set. Adequate accessibility to and avail-ability of treatment in the disadvantaged patient group with schizophrenia are in doubt, since inequalities in healthcare provision for people with schizophrenia have been documented.36 37 In addition, an even longer follow-up is needed to clarify the long-term risk for patients with schizophrenia of developing CKD in this population. Although periodic renal function tests are recommended for patients with schizophrenia, the future cost-effectiveness of such tests needs further study.

CONCLUSIONS

In this national population-based retrospective cohort study, we found a significant association, a 25% increased risk, between schizophrenia and subsequent CKD in a 3-year follow-up period, especially in those older ages, those with DM and those using NSAIDs. Further study is required to extend this positive link to clinical purposes, thereby not only establishing prevent-ive treatment, but also by evaluating the benefits of screening CKD in patients with schizophrenia.

Author affiliations

1Department of Psychiatry, Tri-Service General Hospital, School of Medicine,

National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan

2Student Counseling Center, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan 3Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Shuang Ho

Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan

4Institute of Bioinformatics and Systems Biology, National Chiao Tung

University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

5Department of Biological Science and Technology, National Chiao Tung

University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

6Department of Computer Science, Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank Ms Jessie Wei-Shan Chiang for her help in the administrative work and proofreading of the manuscript.

Contributors N-ST and H-LH conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, data interpretation, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. S-YH, Y-YH and H-CL participated in the design of the study and data interpretation. Y-CK, Y-JY and H-AC participated in the design of the study and data interpretation. W-LC and WC-CC participated in the statistical analysis and data interpretation. N-ST wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding This work was supported by National Science Council of Taiwan under the contract number NSC-103-2221-E-009-117-, and‘Center for Bioinformatics Research of Aiming for the Top University Program’ of the National Chiao Tung University and Ministry of Education, Taiwan, R.O.C. for the project 103W962. This work was also supported in part by the UST-UCSD International Center of Excellence in Advanced Bioengineering sponsored by the Taiwan National Science Council I-RiCE Programme under Grant Number: NSC-103-2911-I-009-101.

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval Institutional Review Board (IRB), Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study (No. B-102-12).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement No additional data are available.

Open Access This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work

non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

REFERENCES

1. Hovatta I, Terwilliger JD, Lichtermann D, et al. Schizophrenia in the genetic isolate of Finland.Am J Med Genet1997;74:353–60. 2. Rossler W, Salize HJ, van Os J, et al. Size of burden of

schizophrenia and psychotic disorders.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;15:399–409.

3. Auquier P, Lancon C, Rouillon F, et al. Mortality in schizophrenia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2006;15:873–9.

4. Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Chen HC. Epidemiology, impact and preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan.Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15(Suppl 2):3–9.

5. Ho Chan WS. Taiwan’s healthcare report 2010.EPMA J 2010;1:563–85.

6. DeWitt EM, Glick HA, Albert DA, et al. Medicare coverage of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors as an influence on physicians’ prescribing behavior.Arch Intern Med2006;166:57–63. 7. Raina PS, Gafni A, Bell S, et al. Is there a tension between

clinical practice and reimbursement policy? The case of osteoarthritis prescribing practices in Ontario. Healthc Policy 2007;3:e128–44.

8. Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, et al. Validation of the National Health Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2011;20:236–42.

9. Chou IC, Lin HC, Lin CC, et al. Tourette syndrome and risk of depression: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan.J Dev Behav Pediatr2013;34:181–5.

10. Liang JA, Sun LM, Muo CH, et al. The analysis of depression and subsequent cancer risk in Taiwan.Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev2011;20:473–5.

11. Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO).Kidney Int 2005;67:2089–100.

12. Chang CY, Chen WL, Liou YF, et al. Increased risk of major depression in the three years following a femoral neck fracture—a national population-based follow-up study.PloS One

2014;9:e89867.

13. Kay R. Proportional hazard regression models and the analysis of censored survival data.Appl Stat1977;26:227–37.

14. Bayle FJ, Misdrahi D, Llorca PM, et al. Acute schizophrenia concept and definition: investigation of a French psychiatrist population. Encephale2005;31(1 Pt 1):10–17.

15. Bak M, Drukker M, van Os J, et al. Hospital comorbidity bias and the concept of schizophrenia.Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:817–21.

16. Wen JK. Folk belief, illness behavior and mental health in Taiwan. Chang Gung Med J 1998;21:1–12.

17. Kleinman A, Gale JL. Patients treated by physicians and folk healers: a comparative outcome study in Taiwan.Cult Med Psychiatry1982;6:405–23.

18. Lin TY. Psychiatry and Chinese culture. West J Med 1983;139:862–7.

19. Huang XY, Sun FK, Yen WJ, et al. The coping experiences of carers who live with someone who has schizophrenia.J Clin Nurs 2008;17:817–26.

20. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia.Br J Psychiatry2000;177:212–17.

21. Mattos P, Santiago MB. Disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with end-stage renal disease: systematic review of the literature.Clin Rheumatol2012;31:897–905. 22. Fonseca V, Jawa A. Endothelial and erectile dysfunction, diabetes

mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome: common pathways and treatments?Am J Cardiol2005;96:13M–8.

23. Oud MJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Somatic diseases in patients with schizophrenia in general practice: their prevalence and health care. BMC Fam Pract2009;10:32.

24. Oud MJ, Schuling J, Groenier KH, et al. Care provided by general practitioners to patients with psychotic disorders: a cohort study. BMC Fam Pract2010;11:92.

25. Satoh M. Endothelial dysfunction as an underlying

pathophysiological condition of chronic kidney disease.Clin Exp Nephrol2012;16:518–21.

26. Herberth M, Rahmoune H, Schwarz E, et al. Identification of a molecular profile associated with immune status in first-onset

schizophrenia patients.Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 2014;7:207–15.

27. Ellingrod VL, Taylor SF, Brook RD, et al. Dietary, lifestyle and pharmacogenetic factors associated with arteriole

endothelial-dependent vasodilatation in schizophrenia patients treated with atypical antipsychotics (AAPs).Schizophr Res2011;130:20–6. 28. Gooch K, Culleton BF, Manns BJ, et al. NSAID use and progression

of chronic kidney disease.Am J Med2007;120:280.e1–7. 29. Peng YL, Leu HB, Luo JC, et al. Diabetes is an independent risk

factor for peptic ulcer bleeding: a nationwide population-based cohort study.J Gastroenterol Hepatol2013;28:1295–9. 30. Cheng KC, Chen YL, Lai SW, et al. Risk of esophagus cancer in

diabetes mellitus: a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. BMC Gastroenterol2012;12:177.

31. Huang WF, Hsiao FY, Wen YW, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with the use of four nonselective NSAIDs (etodolac, nabumetone, ibuprofen, or naproxen) versus a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor (celecoxib): a population-based analysis in Taiwanese adults.Clin Ther2006;28:1827–36.

32. Bonnot O, Anderson GM, Cohen D, et al. Are patients with schizophrenia insensitive to pain? A reconsideration of the question. Clin J Pain2009;25:244–52.

33. de Almeida JG, Braga PE, Neto FL, et al. Chronic pain and quality of life in schizophrenic patients.Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2013;35:13–20.

34. Mitchell AJ, Delaffon V, Vancampfort D, et al. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices.Psychol Med2012;42:125–47.

35. Yang WC, Hwang SJ, Chiang SS, et al. The impact of diabetes on economic costs in dialysis patients: experiences in Taiwan.Diabetes Res Clin Pract2001;54(Suppl 1):S47–54.

36. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction.JAMA 2000;283:506–11.

37. Lawrence D, Kisely S. Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness.J Psychopharmacol2010;24(4

nationwide matched-cohort study

increased risk of chronic kidney disease? A

Is schizophrenia associated with an

Cheng-Chung Chu and Hui-Ling Huang

Hua-Chin Lee, Yun-Ju Yin, Hong-An Chen, Wen-Liang Chen, William Nian-Sheng Tzeng, Yung-Ho Hsu, Shinn-Ying Ho, Yu-Ching Kuo,

doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006777

2015 5:

BMJ Open

http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/1/e006777

Updated information and services can be found at:

These include:

References

#BIBL

http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/1/e006777

This article cites 37 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Open Access

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

non-commercial. See:

provided the original work is properly cited and the use is

non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work

Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative

service

Email alerting

box at the top right corner of the online article.

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

Collections

Topic

Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections(66) Renal medicine (388) Mental health

Notes

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissionsTo request permissions go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To order reprints go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/