The Deep Structure of Confucianism: a social

psychological approach

KWANG-KUO HWANG

ABSTRACT The deep structure of Confucianism is identi ed through structuralist analysis in

order to provide a conceptual framework for conducting social psychological research in Chinese society. Through understanding and imitating the Way of Heaven (tiendao), Confucians constructed the Way of Humanity (rendao), which consists of two aspects; ethics for ordinary people and ethics for scholars. Ethics for ordinary people adopts the principle of Respecting the Superior for procedural justice and the principle of Favouring the Intimate for distributive justice; the person who occupies the superior position should play the role of decision-maker and should allocate resources by favouring intimate relationships. Because Confucian cosmology suggests that the Way of Humanity corresponds to the Way of Heaven, Confucians required individuals to cultivate themselves with the Way of Humanity. Ethics for scholars further endows Confucian disciples with the mission of bene ting the whole society with the Way of Humanity.

An understanding of Confucian cultural traditions is crucial to a comprehensive understanding of Chinese social behaviour. The purpose of this paper is to integrate all of my past research analysing the deep structure of Confucianism from the perspective of social psychology in order to further understanding of Chinese social behaviour. The bulk of my analysis of the deep structure of Confucianism has been published in two works, Confucianism and East Asian Modernization and Knowledge and Action.1 In my

article ‘Chinese relationalism: theoretical construction and methodological consider-ations’,2 I employed the philosophy of realism to construct a theoretical model I call

Face and Favour.3Using this model, I analysed the deep structure of Confucian ideas

in terms of structuralism, which led to the construction of a series of theories on Chinese relationalism. As discussed in my article ‘The discontinuity hypothesis of modernity and constructive realism’,4 the Chinese traditional worldview of achieving

harmony is achieved through maintaining homeostasis within the human body, be-tween humans and the social system, and bebe-tween humans and nature.5Of these three

levels, maintenance of homeostasis between humans and the social system draws the most interest from social psychologists studying Chinese social behaviour, and is the focus of this paper.

The deep structure of Confucianism is composed of ve interrelated parts: concep-tions of destiny, a model of mind, ethics for ordinary people, practical methods of self-cultivation and ethics for scholars. The Confucian Way of Humanity consists of two aspects: ethics for ordinary people, and ethics for scholars. Because Confucians believe that the Way of Humanity corresponds to the Way of Heaven, every person is obligated to practice ethics for ordinary people through self-cultivation. Confucians

ISSN 0955-2367 print/ISSN 1469-2961 online/01/030179-26 Ó 2001 Taylor & Francis Ltd DOI: 10.1080/09552360120116928

180

endowed scholars with the added mission of bene ting the world through the Way of Humanity.

I. Confucian Conceptions of Destiny

Throughout history, people of different cultures have conceived of various worldviews.6

As I pointed out in my article ‘The discontinuity hypothesis of modernity and construc-tive realism’, a worldview helps to answer the questions that may be encountered in human existence, such as ‘Where do I come from?’, ‘Why I am in this life situation?’, ‘Why do I suffer?’ and ‘How do I nd salvation?’7These questions arise as people begin

to contemplate the meaning of life as they experience life changes such as the birth of children, aging, disease, or the death of loved ones. Answers to these questions determine one’s ultimate concerns, and establish one’s goals in life.

Most philosophies that have had an impact on a particular culture are established upon the presumptions of a speci c cosmology and provide answers to the questions concerning the meaning of life. These philosophies thus have profound in uence on the ultimate concerns of the members of that culture. Confucianism is no exception. Confucian scholars term worldviews and the various questions they deal with concep-tions of destiny.

In this section I explore the ultimate concerns in Confucian thinking. After providing a review of four approaches to destiny, I focus on the speci c aspects of the Confucian understanding and the relationship between righteousness and destiny. The nal part of this section explores the cultural standards of values that shape the Confucian understanding of righteousness

I.1. Four Approaches to Destiny

Destiny is de ned as the vicissitudes individuals experience during their existence in this

universe. Human understanding of personal destiny can be categorised into four theoretical conceptualisations:8destiny is controlled by God, destiny is determined by

the laws of nature, destiny can be transcended and destiny is partially determined by biology and partially ful lled through the practice of moral principles.

In the rst conceptualisation, humans conceive of a transcendent God who is the source of all human value and controls human destiny. Humankind should hence endeavour to seek and carry out the will of this God. This belief can be seen in the primitive religion of the Shang and Chou dynasties in ancient China as well as in Christianity during the Middle Ages in Europe. People with this belief may convince themselves that they are agents of God’s will and that therefore no secular power can stop them from ful lling their mission in life. They set about their missions without fear or hesitation.

In the second conceptualisation, humans admit it is impossible to defy one’s destiny, but do not perceive the existence of a sovereign master of the universe. Destiny is only the necessary and inevitable occurrence of facts. Human beings should try to under-stand the essential laws of facts and act accordingly. An example is the rise of rationalism after the 14th-century Renaissance in Europe. Religious authority was greatly reduced in the religious Reformation of the 16th century. As a consequence of disenchantment with the world, humanism was promoted. Materialism, mechanicalism and empirical science arose on the basis of this standpoint after the 18th century. During the Warring States period in China, Hsun Tze (289–288 BC) also adopted this

viewpoint. This perspective acknowledges that an individual’s destiny is subject to objective limitations. However, the limitations come neither from a sovereign master nor from the individual’s self-awareness, but from the laws of nature.

The third conceptualisation is based on the conclusion that human destiny cannot be in uenced through individual self-awareness. Human beings should learn to recognise destiny so that they can transcend it. For example, in Buddhism, believers are advised to pursue the state of Nirvana. According to a Chinese Taoist saying,

Hence a gusty wind cannot last all morning, and a sudden downpour cannot last all day. Who is it that produces these? Heaven and earth. If even heaven and earth cannot go on forever, much less can humans. That is why one follows the Way.9The Way never acts yet nothing is left undone.10

Buddhist teachings propose that one should accept the in uence of Nature.

The fourth conceptualisation of destiny is that of Confucius and Mencius. They argued that as a biological being, humans are bound to encounter the inevitable destiny of birth, aging, disease and the end of physical life. On the other hand, as a being with a conscience and self-awareness, humans must actively put into practice moral princi-ples that exceed personal interest, in order to ful ll their heavenly ordained mission or responsibility.

I.2. Righteousness, Destiny and the Supernatural

The conception of destiny advocated by Confucius and Mencius separates the inevi-table aspects of a person’s biological destiny from a person’s preordained individual nature, which requires awareness and an understanding of certain moral principles. Confucius believed that the physical lives of humans are governed by biological destiny, which he labelled the appointment of heaven.

Po-niuˆ being ill, the Master went to ask for him. He took hold of his hand through the window and said, ‘It is killing him. It is the appointment of heaven. Alas! That such a human should have such a sickness!’11

Po-niuˆ, one of Confucius’ disciples, was critically ill. Confucius visited him and attributed his illness to the appointment of heaven, clearly referring to the destiny that dominates the physical lives of humans.

Confucius rarely discussed the appointment of heaven and the biological aspect of destiny. Instead, he was more concerned with the ordinances of heaven, which bestow a moral obligation to ful ll one’s preordained nature. Confucius felt that ‘without recognition of the ordinances of heaven, it is impossible to be a superior human’12

because without this recognition, a person would only consider immediate personal interests. In contrast, a person with knowledge of the ordinances of heaven is neither drawn by personal bene t nor hindered by potential for personal harm, but solely follows the principle of righteousness (yi). For example, in talking about himself,

Confucius said, ‘At fty, I knew the ordinances of heaven’.13After age fty, Confucius

felt strongly bestowed with moral obligation and saw himself as the successor to Chou Wen Wang (1185–1135 BC), a sage king and founder of the Chou dynasty, with respect to moral ful llment.

Confucius assigned events beyond human power to the domain of destiny and what humans can master consciously to the realm of righteousness. That is, only through righteousness can a person ful ll his individual destiny. Consequently, Confucius felt

182

that humans should focus only on the earthly affairs that they had the power to in uence and not concern themselves with supernatural events over which they have no power. ‘Give yourself earnestly to the duty to establish the standard of right and wrong in the human community, for it is earthly affairs that one should rst learn to handle well.’14Confucius acknowledged supernatural events, but did not dwell on them. His

reasoning was that, ‘While you are not able to serve men, how can you serve their spirits?’ and ‘While you do not know life, how can you know about death?’15‘Humans

should respect spiritual beings, but keep aloof from them.’16

Mencius continued this conception of destiny originated by Confucius. He also believed that human nature is determined by heaven. He believed that only when people spare no effort in ful lling themselves can they obtain true knowledge of their own heaven-ordained natures:

He who has exhausted all his mental constitution knows his nature. Knowing his nature, he knows heaven. To preserve one’s mental constitution, and nourish one’s nature, is the way to serve heaven. When neither a premature death nor long life causes a person any double-mindedness, he waits in the cultivation of his personal character for whatever issue; this is the way in which he establishes his heaven-ordained being.17

People cannot necessarily impact their own personal circumstances such as time of death, poverty or prosperity. They should therefore constantly strive to focus their mental energies on the practice of righteousness to develop their own heaven-ordained natures.

Mencius attributed a person’s encountering of easy circumstances or adversity, blessings or misfortunes, to destiny. However, what happens to a person may or may not be part of the person’s ordinance of heaven. That is, the consequence of ful lling moral duties is attributed to the ordinance of heaven, while the misfortunes that occur as a consequence of a person’s self-abuse and self-abandonment is not attributed to the appointment of heaven.18

In the next section I explore the cultural standards of values that shape the Confucian understanding of the role of righteousness. To provide context for a discussion of these standards, I rst review Confucian scholars’ ideas on human nature in the pre-Chin period.

I.3. Constructing the Way of Humanity by Understanding the Way of Heaven

The cosmology embraced by Confucians contains a view of the universe that has been passed down from the Shang and Chou dynasties in ancient China. This view is best depicted in the Ten Wings (Appendix I) of the I-Ching.19

Vast is the ‘great and originating power’ indicated byKhien! All things owe to

it their beginning. It contains all the meaning belonging to (the name) heaven. The clouds move and the rain is disturbed; various things appear in their developed forms. Complete is the ‘great and originating capacity’ indicated by

Khwan! All things owe to it their birth. It obediently receives the in uences of

Heaven.Khwan, in its largeness, supports and contains all things. Its excellent

capacity matches the unlimited power ofKhien.20

This cosmology manifests three main characteristics. First, it assumes that the universe itself has in nite capacity for procreation. The endless ow and changes of the ‘myriad

things in the universe’ are caused by the encounter and interaction between Heaven and Earth. This understanding is not like the Christian view in the West, which sets aside a divine entity that surpasses the universe and created everything in it. Second, it assumes the change of all things in the universe to be cyclic.

The way of Heaven and Earth is characterized by its consistent change. Everything is going forth and coming back, its end is followed by a new beginning. The sun and the moon are always moving and shining in the sky, the four seasons are changing to foster the harvest, and the sages are consist-ently practicing their way to change the world. The nature of everything in the universe is revealed by watching its consistent change.21

The third point that this cosmology assumes is that all things in the universe have endless vitality. ‘The grand virtue of Heaven and Earth is to breed in an endless succession.’ Wei Chi, the last hexagram in the I-Ching, emphasises that ‘from an end

there comes a new beginning’. The ideas of circularity such as ‘when things are at their worst, they will surely mend’ and ‘adversity, after reaching its extremity, is followed by felicity’, are readily apparent in this cosmology.

Confucius was obviously in uenced by the view of the universe outlined in the

I-Ching. He expressed his thoughts in a conversation with Duke I of Lu.

Duke I asked: ‘Why should a jun zi (true gentleman) follow the Way of

Heaven?’ Confucious said: ‘Because of its ceaselessness. For instance, the sun and moon circle around from east to west, this is the Way of Heaven. Everything in the universe always follows its rule of change, this is the Way of Heaven. Accomplishing everything without doing anything, this is the Way of Heaven. The accomplished thing has its signi cant feature, this is the Way of Heaven.’22

Inspired by natural phenomena such as the alternate illumination of the sun and the moon, the cycle of the four seasons, the gush of water from deep pools and the ceaseless vibrant ow of rivers and streams, Confucian scholars of the pre-Chin period acquired the following insights: ‘To entire sincerity there belongs ceaselessness’;23 ‘Without

sincerity, there would be nothing’;24 and ‘It is only he who is possessed of the most

complete sincerity that can exist under heaven, who can transform’.25Based on these

insights, Confucian scholars concluded that ‘sincerity is the Way of Heaven. The attainment of sincerity is the Way of Humanity.’26The order and reason within the

human heart corresponds to the order and reason in nature.27Once entire sincerity is

achieved, the nature of human beings and the Way of Humanity, which derive from the Way of Heaven, will emerge. Therefore,

It is only he who is possessed of the most complete sincerity that can exist under heaven, and only he who can give its full development to his nature. Once able to develop his own nature, he can do the same for the nature of others. Once able to give sincerity’s full development to the nature of others, he can give their full development to the natures of animals and things. Once able to give full development to the natures of creatures and things, he can assist the transforming and nourishing powers of Heaven and Earth. Once able to assist the transforming and nourishing powers of Heaven and Earth, he may with Heaven and Earth form a union.28

184

cannot be proven by any scienti c method in the empirical world. It is a kind of practical reasoning that is speci c to Confucianism, and sustains individuals in carrying out the Confucian way of personhood. According to this deductive reasoning,

Heaven exists within humans. As humans bring out their internal virtue, they bring to light the Way of Heaven. Hence, although a human’s life is limited, it may be channeled into the in nite and participate with Heaven and Earth.30

Confucians believed that the Way of Humanity as revealed by their sages has a spiritual essence corresponding to the Way of Heaven. As biological organisms, individ-uals are destined by their congenital conditions. However, as human beings with moral awareness, they are able and obligated to practice the Confucian Way of Humanity, which corresponds to the Way of Heaven. Each person is endowed with the heavenly ordained mission of applying the Way of Humanity through the mind of benevolence, a key component of the Confucian ethical system. The next section of this paper explores this component, the Confucian model of Mind.

II. The Confucian Model of Mind

In my bookConfucianism and East Asian Modernization,31I constructed the Confucian

model of Mind (Figure 1) through integration of Confucius’, Mencius’ and Hsun Tze’s viewpoints on human nature. The model I constructed does not represent the ideas on human nature of any one of them alone. Each of them had a model ofconsciousness in

human nature, while the Confucian model of Mind I constructed is a model of

unconsciousness. My model is a second-degree interpretation proposed as a social

scientist after integrating these three scholars’ ideas, as opposed to their own rst-de-gree of interpretations of human nature.32

The mind as comprehended by Confucians of the pre-Chin period has a bi-level existence. Themind of discernment observed by Hsun Tze is the cognitive mind that an

individual possesses as a biological organism in nature.33The mind of benevolence (ren shin) is endowed with the ethical system promoted by Confucius and Mencius of ren

(benevolence), yi (righteousness) and li (propriety). The two parts of this section

explore these two aspects of mind in Confucian thinking.

II.1. The Mind of Discernment

Hsun Tze conceptualised humans as biological organisms and human nature as the innate tendencies of biological individuals.34 The mind Hsun Tze talked about is

capable of cognitive functioning and thinking. For example, Hsun Tze said, ‘The mind is established in the central cavity to control the ve senses – this is what is meant by the natural ruler (T’ien-jium)’.35 ‘When the mind selects from among the emotions by

which it is moved, this is called re ection.’36‘When my thoughts are unclear, then I

cannot decide whether a thing is so or is not so.’37

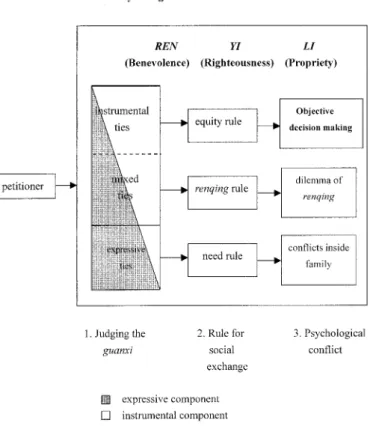

In my Confucian model of Mind, I indicated that the psychological processes of individuals operate through the mind of discernment. In the gure, a diagonal corre-sponding to ren (benevolence) diagonally bisects the rectangle denoting guanxi

(inter-personal relationships). The white portion of the rectangle represents the instrumental component of relationships and the mind of discernment. As a biological organism, humans are born with a variety of innate desires, such as ‘the fondness of the eyes for beauty, or of the mouth for pleasant avors, or of the mind of gain, or of the bones and

Figure 1. Confucian ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–propriety for ordinary people (adapted from Hwang (1995) note 1, p. 233).

skin for the enjoyment of ease.’38 ‘[When] hungry he desires to eat; when cold he

desires to be warm; when toiling he desires to rest; he wants what is bene cial and hates what is injurious.’39An important function of the mind of discernment, therefore, is to

contemplate the proper ways of social interaction in an instrumental manner in order to acquire the resources needed for satisfying the individual’s various (biological) desires.

From the perspective of symbolic interactionism,40instrumental behaviours based on

personal desires such as the love of beauty, sound, avours and gain, re ect the impulse that the subjective self tends to follow. When humans carry out act impulsively, social order may fall apart, so Confucians of the pre-Chin period set up principles of righteousness and propriety and framed laws and regulations. They established the Confucian ethical system ofren-yi-li and expected to pass it on to individuals through

the agents of socialisation. The ethical system ofren-yi-li is employed as a regulation for

interpersonal interaction in order ‘to straighten and ornament innate feelings and correct them, to tame and change those same feelings and to guide them.’41

In Figure 1, a solid line and a dotted line divide the rectangle denoting guanxi

(interpersonal relationships) into three portions. These lines indicate that there exists a continuous dialectical process between the impulses of the subjective self and the social demands on the objective self during interpersonal interaction. This dialectical process enables the individual to adopt the most appropriate rule for social exchange and act in accordance with propriety, so that the self may ‘go forth in the way of moral

186

government and in agreement with reason’.42Hsun Tze maintained that this dialectical

process is the function of the mind of discernment.

II.2. The Mind of Benevolence

Confucians of the pre-Chin period established their ethical system by constructing the Way of Humanity through an understanding of the Way of Heaven. According to the Confucian model of Mind, the mind of benevolence embodies the Way of Humanity (the arrangement of social relationships), which is illustrated in the following passage from the Ten Wings of the I-Ching:

Heaven and Earth exist; all [material] things exist. After all [material] things existed, there came male and female. From the existence of male and female there came husband and wife. From husband and wife there came father and son. From father and son there came ruler and minister. From ruler and minister there came high and low. When [the distinction of] high and low existed, the arrangements of propriety and righteousness came into exist-ence.43

This way of reasoning, when perceived in terms of Levy–Bruhl’s concept as discussed in my article ‘The discontinuity hypothesis of modernity and constructive realism’,44

fully re ects the primitive thinking of mysterious participative law. In other words, in theI-Ching human beings are conceptualised as one of the myriad things in the world.

The universe was composed of Heaven and Earth, corresponding to yang and yin.

When males and females came into existence creating a social world, their uni cation gave birth to a second generation, providing grounds for constructing social relation-ships between father and son, and sovereign and subordinates. Arrangement of social relationships between self and others (the Way of Humanity) therefore corresponds to the Way of Heaven.

The shaded section of the rectangle in Figure 1 represents the expressive component of relationships. Here, the mind of benevolence moderates the expressive component and acts as the individual’s moral conscience. It is exercised during one’s interactions in various relationships. The practice of the mind of benevolence is proportional to the intimacy of the guanxi (interpersonal relationships with others).

Guidance for this guanxi is provided by the Confucian ethical system (ren–yi–li),

which consists of two parts: ethics for ordinary people and ethics for scholars. In the next section, I describe Confucian ethics for ordinary people, leaving description of ethics for scholars for Section V.

III. Ethics for Ordinary People: The Ethical System of Benevolence– Righteousness–Propriety (ren–yi–li)

According to Confucian understanding. As biological organisms humans are born with a number of innate desires:

There belongs to it, even at his birth, the love of gain, and as actions are in accordance with this, contentions and robberies grow up, and self-denial and yielding to others are not to be found; there belong to it envy and dislike, and as actions are in accordance with these, violence and injuries spring up, and self-devotedness and faith are not to be found; there belong to it the desires

of the ears and the eyes, leading to the love of sounds and beauty, and as the actions are in accordance with these, lewdness and disorder spring up, and righteousness and propriety, with their various orderly displays, are not to be found. It thus appears, that to follow human nature and yield obedience to its feelings will assuredly conduct to contentions and robberies, to the violation of the duties belonging to everyone’s lot, and the confounding of all distinc-tions, till the issue will be in a state of savagism.45

Because of the innate desires of humans as biological organisms, Confucians of the pre-Chin period argued that humans should be regulated by the ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–propriety (ren–yi–li). Among classical Confucian works, the

following passage inThe Golden Mean best depicts the relationships among benevolence

(ren), righteousness (yi), and propriety (li) in Confucian ethics:

Benevolence (ren) is the characteristic attribute of personhood. The rst

priority of its expression is showing affection to those closely related to us. Righteousness (yi) means appropriateness; respecting the superior is its most

important rule. Loving others according to who they are, and respecting superiors according to their ranks gives rise to the forms and distinctions of propriety (li) in social life.46

The notion of loving others according to who they are and respecting superiors according to their rank indicates an emphasis on the differential order of interpersonal relationships. The above citation from The Golden Mean not only demonstrates the

interrelated concepts of benevolence (ren), righteousness (yi), and propriety (li), but

also implies the dimensions along which Confucians assess role relationships in social interaction.

Speci cally, Confucians propose that in interacting with other people, one should begin with an assessment of the role relationship between oneself and others along two cognitive dimensions: intimacy/distance and superiority/inferiority. The former refers to the closeness of the relationship while the latter indicates the relative superior/inferior positions of the two parties involved. Once the assessment is made, favouring people with whom one has a close relationship can be termed benevolence (ren), respecting

those for whom respect is required by the relationship is called righteousness (yi), and

acting according to the social norms is propriety (li).

This proposition ofThe Golden Mean has an important implication when examined

with reference to justice theory in Western psychology, which divides the concepts of justice in human society into two categories: procedural justice and distributive justice. Procedural justice refers to the steps that should be followed by members of a group to determine methods of resource distribution. Distributive justice is the particular method of resource distribution that is accepted by group members.47

According to Confucian thinking, procedural justice in social interaction should follow the principle of respecting the superior. The person who occupies the superior position should play the role of resource allocator. The resource allocator should then follow the principle of favouring the intimate in choosing an appropriate rule of resource distribution or social exchange. Righteousness (yi) in the Confucian model of

Mind (Figure 1), as well as the rule for social exchange in the psychological process of resource allocator refer to distributive justice.

As pointed out in my bookConfucianism and East Asian Modernization,48Confucian

188

provides certain cultural guidance. However, scholars, who are endowed with addi-tional social and cultural responsibilities, are placed under higher demands by Confu-cian ethics. This section explores ConfuConfu-cian ideas of procedural and distributive justice with respect to Confucian ethics for ordinary people. Confucian ethics for scholars are examined in a separate section.

III.1. Procedural Justice: The Principle of Respecting the Superior

Confucians consider the relationships between father and son, sovereign and subordi-nate, husband and wife, elder brother and younger, and friends to be the most fundamental relationships in society and termed themthe ve cardinal relationships (wu lun). According to Confucianism, each pair of relationships in the ve cardinal

relation-ships has an appropriate type of interaction in accordance with the relative superior/in-ferior positions as well as with the intimacy/distance of the relationship. In fact, it is along these two dimensions that Confucian scholars of the pre-Chin period evaluate the role characteristics of these ve relationships and propose the most appropriate ethics for each of them. For example, Mencius maintains:

Between father and son, there should be affection: between sovereign and subordinate, righteousness; between husband and wife, attention to their separate functions; between elder brother and younger, a proper order; and between friends, friendship.49

Among these ve dyadic relationships, Mencius most emphasised those between father and son, and between sovereign and subordinate: ‘In the family, there is the relation of father and son; abroad, there is the relation of prince and minister. These are the two important relations among men.’50These two relationships provide examples of

the way Mencius determined the various ethical rules for different role relationships. For a son, his father is his most intimate relationship along the dimension of intimacy/ distance and also is his senior along the dimension of superiority/inferiority. As benevolence is the most highly valued virtue in Confucianism, Mencius advocated affection between father and son. For the person who is in the role of a subordinate, the sovereign falls on the far end of the dimensional continuum of intimacy/distance, as well as the far end along the dimension superiority/inferiority. As there is no intimacy to be attended to, Mencius proposed only righteousness between sovereign and subor-dinate. Similar principles may be applied in determining the various ethics for the other relationships.

The Confucians set up appropriate ethical principles for a given role relationship according to superior/inferior positions and the intimacy/distance of the relationship. This system can be interpreted in terms of justice theory in Western psychology. When a person begins a social interaction with others, the dimensions of intimacy/distance and superiority/inferiority concerning the relationship between the two parties should be carefully considered in order to achieve procedural justice and distributive justice respectively. After an assessment of superior/inferior status in the relationship, the principle of respecting the superior should be adhered to determine who should play the role of resource allocator

What are the things which humans consider righteous (yi)? Kindness on the

part of the father, and lial duty on that of the son; gentleness on the part of the elder brother, and obedience on that of the younger; righteousness on the

part of the husband, and submission on that of the wife; kindness on the part of the elders, and deference on that of juniors:benevolence on the part of the

ruler, and loyalty on that of the minister. These are the ten things that humans consider to be right.51

Although the interaction between every pair of the ve cardinal relationships should be based on benevolence (ren), the values and ethics emphasised in these relationships

differ due to their various role functions.

Speci cally, the values that should be most cherished and emphasised in the relation-ships between father and son, sovereign and subordinate, husband and wife, elder brother and younger, and between friends, are respectively affection, righteousness, attention to separate functions, a proper order and friendship. Except for the relation-ship between friends, the relationrelation-ships are all vertical ones between superiors and inferiors. There are differences in status within each pair of the rst four relationships as well as in the power available to them. For instance, the conduct of father and son should accord with the standard of righteousness where the father is kind and the son is lial. When the ‘ten things’ do not exist, conduct is considered unrighteous.

These requirements do not constitute an exhaustive list of Confucian standards for righteousness (yi). For example, when one breaks a promise to friends, one will also be

considered unrighteous. The reason the ten things of righteousness are speci cally de ned in Li Chi is that there exists a differential order within the ve pairs of roles

involved. In accordance with the idea of the ten things of righteousness (yi), persons

who assume the roles of father, elder brother, husband, elders, or ruler should make decisions in line with the principles of kindness, gentleness, righteousness, kindness and benevolence respectively. And for those who assume the roles of son, younger brother, wife, juniors, or minister, the principles of lial duty, obedience, submission, deference, loyalty and obedience to the instructions of the former group apply. The superior/in-ferior and sovereign/subordinate aspects of the relationships between the two groups are apparent, with the former being dominant and the latter subservient.

III.2. Distributive Justice and the Principle of Favouring the Intimate

After considering a role relationship along the dimension of superiority/inferiority, resource allocators should then choose an appropriate rule for exchange or resource distribution. As illustrated in the Confucian model of Mind, the Confucian ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–propriety is used to make this choice. Proper assessment of the intimacy/distance of the relationship corresponds to benevolence (ren), choosing an appropriate rule for exchange according to closeness of the

relation-ship corresponds to righteousness (yi) and acting properly after evaluating the loss and

gain of exchange corresponds to propriety (li).

In the Confucian model of Mind in Figure 1, a diagonal bisects the rectangle corresponding to benevolence (ren). The shaded section represents the expressive

component and the white portion represents the instrumental component. This division implies that the Confucian idea of benevolence contains the principle of favouring the intimate. Instead of treating everyone with equal affection, the intimacy of relationships is considered and affection given accordingly. The same rectangle denoting guanxi

(interpersonal relationships) is also divided into three parts (expressive ties, mixed ties and instrumental ties) by a solid line and a dotted line. These parts are proportional to the expressive component. The solid line separating expressive ties within the family

190

and mixed ties outside the family indicates a relatively impenetrable psychological boundary between family members and people outside the family. Different distributive justice or rules for exchange are applicable to these two types of relationships during social interactions.

According to my theoretical model of Face and Favour,52the relationships between

father and son, husband and wife, and elder brother and younger are ruled by expressive ties. In these relationships the need rule for social exchange should be adhered to and people should try their best to satisfy the other party with all available resources. The relationship between friends makes use of mixed ties and follows the

renqing rule. Between the ruler and ordinary people, there is scarcely any direct

interaction and ordinary people often have little choice but to obey the ruler. Confu-cians did not set up speci c ethical principles for strangers beyond the ve cardinal relationships. When individuals want to acquire a particular resource from someone with whom they have instrumental ties, they tend to follow the equity rule and use instrumental rationality.

III.3. The Deep Structure of Benevolence–Righteousness–Propriety (ren–yi–li)

Our discourse so far is supported by various passages in classical Confucian works. Benevolence (ren) is recognised as the perfect virtue of the mind and the ontology of

moral principles that exceed personal interest.53Righteousness (yi) and propriety (li)

are derivatives of benevolence (ren), and extend to other secondary moral rules.

Together they constitute the complex ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–pro-priety. All major interpersonal relationships in one’s lifetime should be arranged with reference to the deep structure of this ethical system. To illustrate the signi cant features of Confucian society, it is necessary to expound upon the structural relation-ships among the three core concepts of Confucianism: benevolence, righteousness and propriety.

III.3.1. Benevolence: From the Intimate to the Distant. Confucius de ned benevolence as

‘lovingall men’.54He thought that a person who truly knows how to love all people can

put himself in another’s position. ‘Wishing to be established himself, [he] seeks also to establish others; wishing to be enlarged himself, he seeks also to enlarge others’.55

Confucius knew very well it is not easy to love all people. When people try to express love or benevolence to others during social interactions, they often have to give away some of their own resources. As people possess only nite resources, it is not realisti-cally possible to lavish in nite benevolence upon others.

Confucius seldom praised individuals for being benevolent (perfectly virtuous). When asked, ‘Is someone perfectly virtuous?’ his response was either ‘I don’t know’ or ‘How can we know that?’ One of the main reasons for these answers is the dif culty of truly loving all people. When Tsze-kung asked Confucius whether a person could be called benevolent (perfectly virtuous) if that person ‘extensively [confers] bene ts on other people, and [is] able to assist all’, Confucius answered, ‘Is such a human considered merely virtuous? He can almost be called a sage! Even Yaˆo and Shun are still striving to achieve this.’56

Mencius maintained that to practice the virtue of benevolence, one should start with service to one’s parents.57‘There has never been a benevolent person who neglected his

parents.’58 ‘Of services, which is the greatest? The service of parents is the greatest.

ful lling the duty of serving their parents can people then practice the virtue of benevolence to others in the order of intimacy.

Confucius proposed that

a youth, when at home, should be lial, and, abroad, respectful to his elders; [he] should be earnest and truthful; [he] should over ow in love to all and cultivate the friendship of the good.60

These directions suggest a sequence for performing benevolence. Confucians perceived lial piety as the root of all benevolent actions. ‘In carrying out the virtue of benevo-lence, one should rst [bend] one’s attention to what is radical.’61 That is, people

should practice lial piety and the service of their parents, and thereafter heed other benevolent actions.

III.3.2. Righteousness: To Dwell in Benevolence and Pursue the Path of Righteous-ness. Mencius shared Confucius’ view on righteousness and gave the most elaborate

account of righteousness of all Confucian scholars of the pre-Chin period. He often put his teachings on benevolence and righteousness side by side, and thought that the judgement of righteousness should be based on the concept of benevolence, which he labelled dwelling in benevolence and pursuing the path of righteousness.

Benevolence is the human mind, and righteousness is the human path. How lamentable is it to neglect the path and not pursue it, to lose this mind and not know to seek it again!62Benevolence is the tranquil habitation of humans, and

righteousness is the straight path.63

Mencius also agreed that the performance of benevolence and righteousness should begin within the family. ‘The richest fruit of benevolence is this, the service of one’s parents.’64

Yang Chu, a contemporary of Mencius, promoted the competing idea of ‘every man for himself’. He said that though he might have bene ted the whole kingdom by plucking out a single hair, he would not have done it. Another philosopher, Mo Ti, proposed the idea of universal love, suggesting that one should love others’ fathers as one’s own. Mencius criticised them:

Now, Yang’s principle is ‘every man for himself’, which does not acknowledge the claims of the sovereign. Mo’s principle is ‘to love all equally’, which does not acknowledge the particular affection due to a father.65

Yang’s and Mo’s propositions are contradictory to the Confucian principles of having the mind dwell in benevolence and of the differential order of love. Mencius denounced both of them as beasts.

Although Confucians maintained the idea of the differential order of love and believed that the exercise of the Way of Humanity should start within the family, the performance of benevolence did not end there. Especially for scholars, who are endowed with more social and cultural obligations, Confucians thought the practice of the Way of Humanity should start within family and then extend to other relationships along the differential structure of intimacy: ‘He is lovingly disposed to people generally, and kind to creatures’.66‘Beginning with what they care for, proceed to what they do

not care for.’67 This point has an important implication for the understanding of

192

III.3.3. Propriety: Interaction in Line with Propriety.No matter which rule of exchange

resource allocations use during social interactions, Confucians maintained that they should always heed the principle of propriety when choosing an appropriate response after the evaluation of loss and gain. Propriety (li) initially denoted religious etiquette

in the East Chou dynasty, but lost its religious connotation and gradually became a tool for maintaining political and social order in the West Chou dynasty.68The concept of

propriety (li) contains three elements according to classical Confucian works.

I. Etiquette is the procedures or steps that should be taken in a ceremony, i.e. what participants should do during the ceremony. For example, there are detailed accounts of proper etiquette for occasions such as visiting the emperor, employ-ing of cials, funerals and weddemploy-ing inLi Chi, ILi and Chou Li.

II. Utensils are the tools needed for completing a ceremony. These include carriage, clothing, ags, seals, bells, vessels, jade and gems.

III. Titles indicate a person’s status as well as the degree of intimacy of the relationship between the host and the participants of the ceremony. Examples are family titles such as father and son, and political titles such as Son of Heaven, feudal princes and of cials.

There are detailed accounts and regulations for both the titles (ming) and utensils

(chih) that aristocrats were entitled to use under the feudal system of the East Chou

dynasty. Confucius himself also stressed these regulations of propriety.69Chõˆ Luˆ once

asked Confucius about the priority of government, and Confucius replied that what is necessary is to rectify names. Chõˆ Luˆ made fun of Confucius’ obstinately observing the old rules, but Confucius responded: ‘If the names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs can not be carried to success.’70

One time, Jonhshu Yuhsi rescued the commander of Wei, General Sun, in the battle between the states Chi and Wei. The prince of Wei intended to reward him with land. Jonhshu declined with thanks and instead requested to use the music band and carriage that only feudal princes were entitled to use when he paid visit to the emperor. The prince of Wei granted his request, for which Confucius felt sorry. He thought that it was better to have given more land to Jonhshu and gave a lecture about not lending titles and utensils to others.71

Witnessing countless battles and annexations, and the killing of rulers by feudal princes, Confucius responded: ‘ “It is according to the rules of propriety,” they say. Are gems and silk all that is meant by propriety? “It is music”, they say.

Are bells and drums all that is meant by music?’72

The superior person considers righteousness to be essential in everything. He performs it according to the rules of propriety. He brings it forth in humility; he completes it with sincerity. This is indeed a superior human.73

According to Chu Tze’s annotation, the essential mentioned by Confucius is the kernel of things. Confucius held that a superior person’s mind dwells in benevolence. A superior person considers righteousness to be essential in everything, performs it according to the rules of propriety, brings it forth in humility and completes it with sincerity. When the mind of benevolence no longer exists and a person is without the virtues proper to humanity, the empty form of propriety and music do not embody any meaning. Confucius proclaimed: ‘If a human be without the virtues proper to

hu-manity, what has he to do with the rites of propriety? If a humans be without the virtues proper to humanity, what has he to do with music?’74

Before the Shang and Chou dynasties, propriety was the only restriction and regulation imposed externally. Confucius combined the concepts of propriety, benevo-lence and righteousness, and transformed the external ritual of propriety into a cultural psychological structure.75He expected that humans, based on the mind of benevolence,

could make moral judgements in line with righteousness after assessing the various role relationships in social interactions, and then act according to propriety. The integration of benevolence (ren), righteousness (yi) and propriety (li) is the most signi cant feature

of Confucian ethics.

IV. Self-cultivation with the ‘Way of Humanity

The Confucian ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–propriety constitutes the core of the Way of Humanity. The Chinese name for the Way of Humanity isrendao

ordao. Human beings must cultivate themselves with the Way of Humanity in order to

ful ll their heaven ordained destinies. A delicate set of practices for self-cultivation was developed so that Confucian disciples could learn to cultivate themselves with the Way of Humanity. From the Son of Heaven down to the general masses, self-cultivation was the root of everything else.76Even the sovereign could not neglect cultivation of his own

character.77

The goal of self-cultivation is to apply the Way of Humanity through the ve cardinal relationships. Self-cultivation requires enthusiasm about learning the Way of Hu-manity, practicing it with vigour and shame when one’s conduct is contradictory to it.78

These methods for self-cultivation are not virtues, but they constitute the essential process for achieving the three virtues, wisdom (zhi), benevolence (ren) and courage

(yung).79A person who is willing to assume the responsibility of self-cultivation is called

a jun zi (true gentleman). People who do not accept this responsibility may be

denounced as xiao ren (small-minded people).

IV.1. Fondness for Learning Leads to Wisdom

Confucius put great emphasis on learning and often mentioned it in his daily teachings. The Analects of Confucius begin with the saying, ‘To learn and in due time to repeat what one has learned, is that not after all a pleasure?’80As he looked back on his life,

Confucius said he had his mind set on learning at the age of fteen and ever since then has been learning without satiety and instructing others without becoming weary.81As

a learned scholar, Confucius stressed that he was not born with his knowledge. He talked about learning and studying, saying, ‘I am one who is fond of antiquity, and earnest in seeking it there’,82and ‘[when] I walk along with two others, they may serve

me as my teachers’.83Confucius recommended asking for information and not being

ashamed to learn from one’s inferiors when encountering incomprehensible things. Commenting on his own attitude of acquiring knowledge, he said, ‘eager pursuit of knowledge makes one forget food, the joy of its attainment makes one forget sorrows and not perceive that old age is coming’.84

A set of Confucian theories on learning is recorded inThe Golden Mean. Confucian

disciples are required to learn the proper ways of extensive study, accurate inquiry, careful re ection, clear discrimination and earnest practice. Most importantly, if disciples encounter anything in what they have studied that they cannot understand, in

194

what they have inquired about that they do not know, in what they have re ected on that they do not apprehend, on which their discrimination is not clear, or if their practice fails in earnestness, they should not give up easily. Instead, they should persevere with the spirit that ‘[if] other people succeed by one effort, I will use a hundred efforts; if another person succeeded by ten efforts, I will use a thousand’,85

until what they strive to learn is crystal clear.

Confucius thought that spontaneous interest leads to the most ef cient learning. ‘To prefer it is better than to only know it. To delight in it is better than merely to prefer it.’86 Disciples should embrace the attitude of ‘learning as if you were following

someone with whom you could not catch up, as though it were someone you were frightened of losing’,87and become ‘widely versed in letters’.88During the process of

learning, one should ‘from day to day [be] conscious of what one still lacks, and from month to month never [forget] what has already been learned’.89Disciples should strive

to ‘reanimate the old and gain knowledge of the new’.90 Memorising itself is not

suf cient for learning. Confucius said, ‘He who learns but does not think, is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is, in great danger. If one only achieves the parts without comprehensive integration, learning will result in confusion.’91 Confucius encouraged

his disciples to abstract from the learning materials some fundamental principles so that they could ‘have one thread upon which to string them all’,92and then when he ‘[holds]

up one corner it can come back [to him] with the other three’.93Students should apply

and make use of what they have learned.

IV.2. Vigorous Practice Leads to Benevolence

Confucian education consists mainly of instruction on its ethical system. According to Kant’s epistemology, the Confucian ethical system uses practical reasoning that can be acquired only through the process of realisation and doing,94 or knowing by

practis-ing,95 but not theoretical reasoning, which is necessary for constructing a system of

knowledge on the basis of sensory experience. For this reason, Confucius stressed vigorous practice in his teachings. For Confucians, the purpose of learning is to apply knowledge in life.96 Knowledge is useless when it can only be talked about and not

implemented. Confucius demanded that his disciples ‘not preach until they have practiced what they preach’.97They should be ‘slow in word but prompt in deed’, and

‘only [speak] of what it would be proper to carry into effect’.98

Mencius also stressed the practice of ethics. He thought that humans innately possess benevolence, righteousness, propriety and wisdom.99 These things are ‘the knowledge

possessed by humans without the exercise of thought’, and ‘the ability possessed by a person without having been acquired by learning’.100 The practice of the Way of

Humanity should be as easy. If someone says, ‘I am not able to do it’, it is actually ‘a case of not doing’ instead of ‘not being able to do’.101Any person who focuses attention

on the practice of the Way of Humanity is able to become the same type of person as the Sage Shun.102

Hsun Tze, who believed human nature to be evil, did not agree that humans are born with a conscience. He thought that the Way of propriety and righteousness is learned from the sages or kings of antiquity. Nonetheless, he also put great emphasis on the practice of the Way of Humanity (dao). ‘Though the road (dao) be short, if a person

does not travel on it, he will never get there; though a matter be small, if he does not do it, it will never be accomplished.’103

Sincerely put forth your effort, and nally you will progress. Study until death and do not stop before. For the art of study occupies the whole life; to arrive at its purpose, you cannot stop for an instant. To do that is to be human; to stop is to be a bird or beast.104

As Kant suggested, the Confucian ethical system uses practical, but not theoretical reasoning. Confucian scholars insist that one must not only learn, but also practice the way of benevolence for one’s whole life. Practice of the Way of Humanity was a criteria for differentiating human beings from beasts.

IV.3. Sensitivity to Shame Leads to Courage

The ethical system of benevolence, righteousness and propriety entails the belief that people should feel ashamed when their words exceed their actions, and when they deviate from the Way of Humanity. Confucius said, ‘The superior human is modest in his speech, but exceeds in his actions’.105The reason the ancients did not readily give

utterance to their words, was that they feared lest their actions should not come up to them.’106

Mencius also maintained that people should abide by ethics through action instead of with empty words. ‘A person may not be without shame. When one is ashamed of having been without shame, he will afterwards not have occasion to be ashamed.’107

The sense of shame is of great importance to humans. Those who form contrivances and versatile schemes distinguished for their artfulness, do not allow their shame to come into action. When a person differs from other men in not having this sense of shame, what will he have in common with them?108

Confucians assigned scholars different goals and standards than ordinary people. The conditions under which they were expected to feel shame also differed. For example, scholars were given the speci c mission of bene ting the world with the Way of Humanity. The life goal for scholars is the actualisation of that mission instead of the pursuit of material prosperity. ‘A scholar, whose mind is set on truth, and who is ashamed of bad clothes and bad food, is not t to be discoursed with.’109 Confucius

praised Tsze-luˆ for ‘[dressing] himself in a tattered robe quilted with hemp, and standing by the side of men dressed in furs, unashamed’.110

However, the Way of Humanity does not require an unconditional acceptance of poverty. According to the Confucian ideal, the purpose of a person’s occupying an of cial post is to bene t the world with the Way of Humanity. When the country is governed with right principles, one should work for the government. In this case, poverty and a mean condition should be considered something to be ashamed of since they indicate a person’s inability to serve well in the government. On the other hand, when the nation is ill-governed, and yet a person gains wealth and honor from his of cial post, he should feel shame for ‘[standing] in a prince’s court, and not carrying principles into practice’,111and even for acquiring a reputation beyond one’s merits.112 IV.4. Jun zi (a True Gentleman) vs xiao ren (a Small-Minded Person)

Confucians promoted self-cultivation by the means of love of knowledge, strenuous attention to conduct and sensitivity to shame. The goal was to develop people intojun zi (true gentlemen) who abide by the Way of Humanity. The term jun zi originally

196

denoted a person with the status of nobility. Confucius changed the meaning and used it to denote a person with moral cultivation. It is this second meaning that is applicable in most of the passages in the Analects of Confucius. The concept of jun zi was often

mentioned in Confucius’ daily teachings. For example, when Tsze-hsiaˆ came to follow Confucius, the Master said, ‘be a scholar after the style of superior humans, and not after that of mean humans’.113Confucius constantly discussed the distinction between jun zi and xiao ren with his disciples.

Confucius attempted to illustrate the difference betweenjun zi and xiao ren from

every perspective with the aim of guiding his disciples into beingjun zi.114Ajun zi is a

human whose mind dwells on benevolence and he is familiar with the ethical system of benevolence–righteousness–propriety. He not only follows the principle of dwelling in benevolence and pursuing the path of righteousness in dealing with his daily life, but also humbles himself and abides by the virtue of propriety. Unlike a xiao ren, who

focuses his eyes on the gains and losses in this secular world, the major concern for a

jun zi are the moral principles founded on the ethical system of

benevolence–righteous-ness–propriety. ‘The mind of a superior human is conversant with righteousness; the mind of a mean human is conversant with gain.’115 ‘The superior human thinks of

virtue; small humans think of comfort. Superior humans think of the sanctions of law; small humans think of the favors that they may receive.’116‘The superior human may

indeed have to endure want, but the mean human, when he is in want, gives way to unbridled license.’117 Confucius observed that a jun zi, who adheres to the Way of

Humanity and has his mind dwelling on benevolence, not only makes demands on himself, asking himself to actualise the ethical system of benevolence–righteousness– propriety. He also ‘[seeks] to perfect the admirable qualities of men, and does not seek to perfect the bad qualities’.118Consequently, ajun zi can be completely at ease and free

from perturbation. During interaction with others, he can be ‘affable but not adula-tory’,119 ‘catholic and not partisan’,120 and display ‘a digni ed ease without pride’.121

These actions are in contrast to those of axiao ren, who strenuously pursues personal

interest.

V. Confucian Ethics for Scholars: Bene ting the World with the Way of Humanity

According to Confucian thinking, the tranquility, order and harmony in society are founded on each individual’s moral cultivation. Every person therefore has the re-sponsibility of learning to become a jun zi. This responsibility and the self-cultivation

of virtues is the fundamental demand Confucians made on people.122Ordinary people

are required to practice the Way of Humanity in their family and community life, but scholars, who are endowed with cultural missions, were given even higher standards of moral practice.

V.1. Scholars Dedicate Themselves to the Way of Humanity

Confucian ethics are status ethics. Confucians endowed scholars with the mission of bene ting the world with the Way of Humanity. Confucians expected their disciples to practise the principles and not to use them as the means for enlarging their personal reputation.123Pursuit of the Way of Humanity has intrinsic value and takes a lifetime

die in the evening without regret’.124Both Mencius and Tsang Tze expounded on this

ideal of Confucianism.

The philosopher Tsang said, ‘The of cer may not be without breadth of mind and vigorous endurance. His burden is heavy and his course is long. Perfect virtue is the burden that he considers it is his to sustain – is it not heavy? Only with death does his course stop – is it not long?125

According to the Confucian ideal of governing with virtue, a ruler is obliged to govern his country in the Way of Humanity, so that his people can be bathed in benevolence. This done, he must expand from making his own country prosperous with benevolence, to achieving the ideal of letting benevolence prevail in the world. Scholars play an important role in this process. Once given an of cial post, a scholar should adhere to the ideal of the Way of Humanity, serve the sovereign with the Way of Humanity, ‘practice his principles for the good of the people’, confer bene ts to them, and even ‘[make] the whole kingdom virtuous’.126 The larger the scope in which a

scholar exercises the Way of Humanity, the higher that scholar’s moral performance is. Confucians thought that leaders should cultivate themselves, manage their families, govern the nation and bring tranquility to the world. In contrast, when a scholar’s desire for of ce is disappointed, he ‘though poor, does not let go his righteousness’. He should ‘[attend] to [his] own virtue in solitude’, and ‘[practice] [his] [principles] alone’, in order to ‘became illustrious in the world’.127 Only by ‘holding rm to death [in]

perfecting the excellence of his course’, and striving to be above the power of riches and honours, and beyond letting poverty and mean condition’s temptation to swerve from principle128 can a person be called great.

V.2. Serving the Sovereign with the Way of Humanity

Confucians evaluate a person’s moral performance in terms of the scope in which he exercises the Way of Humanity when making moral judgements and taking moral actions. When a scholar obtains an of ce, he attains higher moral achievement as he extends benevolence to larger groups. As Chu Tze said, ‘A person’s benevolence is something like the vastness of water. It might be a glass of water, a brook, a river, or the ocean. The benevolence of a sage is certainly like the ocean.’129 How a person’s

benevolence is perceived accords with the size of the groups to which he applies benevolence. The more people he confers bene ts on, the higher his moral achieve-ment.

Confucians proposed that ‘a person of virtue deserves to occupy an important position’. Just as scholars are obliged to extend benevolence, so are aristocrats and feudal princes who occupy higher social positions. Mencius said,

If the sovereign be not benevolent, he cannot preserve the throne from passing from him. If the Head of a State be not benevolent, he cannot preserve his rule. If a high noble or great of cer be not benevolent, he cannot preserve his ancestral temple. If a scholar or common people be not benevolent, he cannot preserve his four limbs.130

The sovereign, the Head of a State and the high noble or great of cer are people who occupy the highest positions in society. Mencius argued that when these people make any judgement concerning righteousness, they should have their decisions grounded in benevolence, lest they lose people’s hearts and, thereafter, their positions.

198

The virtue of benevolence is based on an individual’s love for the group or com-munity he belongs to. A governor should make full consideration for his own group as he exercises his decision-making power to ensure that he will ‘gather and give what the people desire, and withhold what they dislike’.131 Mencius suggested that the most

important duty for a minister was to rectify what is wrong in the sovereign’s mind. According to Confucianism,

Let the prince be benevolent, andall his acts will be benevolent. Let the prince

be righteous, andall his acts will be righteous.132Let the prince be correct, and

everything will be correct. Once the ruler is recti ed, the kingdom will be rmly settled.133The way in which a minister serves his prince contemplates

simply leading him in the right path, and directing his mind to benevolence.134

Based on benevolence for the group, a scholar may develop a relationship of equity with the sovereign in the course of his of cial duty. Mencius said to the king Hsu¨an of Ch’õˆ,

When the prince regards his ministers as his hands and feet, his ministers regard their prince as their belly and heart; when he regards them as his dogs and horses, they regard him as any other human; when he regards them as the ground or as grass, they regard him as a robber and an enemy.135

This concept re ects the Confucian ethic of autonomy. In terms of procedural justice, Confucians advised that those who assume superior roles, i.e. father, elder brother, husband, elders and ruler, should make decisions in line with the principles of kindness, gentleness, righteousness, kindness and benevolence respectively. For those who as-sume the roles of son, younger brother, wife, juniors, or minister, the principles of lial duty, obedience, submission, deference, loyalty and obedience to the instructions of the former group apply. However, when the superior violates the principles of benevolence, Confucians encouraged the inferior to correct them. It is a general principle put forward by Confucians; they emphasised that one should ght against unrighteous behaviours no matter whom they come from:

In case of contemplated moral wrong, a son must never fail to warn his father against it; not must a minister fail to perform a like service for his prince. In short, when there is question of moral wrong, there should be correction.136

According to Confucian ideas of the pre-Chin period, the father/son and sovereign/ minister relationships belong to two distinct categories. When the superior in each of these relationships was engaged in morally wrong activities, the subordinate’s reaction in making suggestions for correction was also different.

In serving his parents, a son may remonstrate with them, but gently; when he sees that they do not incline to follow his advice, he shows an increased degree of reverence, but does not abandon his purpose; and should they punish him, he does not allow himself to murmur.137

This kind of unbreakable bond of kindred does not exist in the relationship between sovereign and minister. If the sovereign becomes tyrannous and does not listen to admonition, the minister should react differently.

In his answer to King Hsu¨an of Ch’õˆ about the of ce of high ministers, Mencius distinguished between relationships in which the high ministers are in the nobility, and therefore relatives of the prince, and those in which they have different surnames from the prince.138 For those in the rst category who have a blood connection with the

prince, if the prince makes serious mistakes and does not respond to their respected admonitions, they should determine their course of action by considering the principle that ‘the people are the most important element in a nation; the spirits of the land and grain are the next, the sovereign is the lightest’.139They should supersede the prince as

he might harm the state. On the other hand, the high ministers with different surnames from the prince have no inseparable connection to him. If the prince makes mistakes and does not accept their repeated advice, they can just leave the state for another one. If the emperor is tyrannical and does not practice benevolent government, then powerful chiefs of state should rise and ‘punish the tyrant and console the people’. For example, in a famous dialogue with Mencius, King Hsu¨an of Ch’õˆ asked about a case in which a minister put his sovereign, named Chau, to death.

The king Hsu¨an of Ch’õˆ asked saying, ‘Was it so, that T’ang banished Chieh, and that king Wuˆ smote Chaˆu?’ Mencius replied, ‘It is so in the records’. The king said, ‘May a minister then put his sovereign to death?’ Mencius said, ‘He who outrages the benevolence proper to his nature, is called a robber; he who outrages righteousness is called a ruf an. The robber and ruf an we call a mere fellow. I have heard of the cutting off of the fellow Chau, but I have not heard of the putting a sovereign to death, in his case.’140

These citations highlight the fact that the differential order of superior/inferior and sovereign/subordinate so emphasised by Confucians should be placed under the major premise that both parties abide by the Way of Humanity. When the sovereign violates the principle of benevolence, the subordinate is not bound to follow blindly. This is the most outstanding feature of the Confucian ethic of autonomy. The autonomy and self-government that the political gures in Chinese history are characteristic of have drawn increasing attention from Sinologists of political culture.141 It has been shown

that they have their root in Confucianism. However, the role Confucians assign to scholars is to serve the sovereign with the Way of Humanity and to rectify what is wrong in the sovereign’s mind. Whether a scholar can actualise the Way of Humanity depends on whether an opportunity of serving in the government is granted to him. Hence the monarchy becomes the precondition for a scholar to realise his ideal personality.142

Paradoxically, a Confucian scholar who has been dedicated to the cultivation of his moral personality is unable to ful ll his moral goals and personality independently.

VI. Conclusion

In this paper, the deep structure of Confucianism is analysed in terms of structuralism based on my theoretical model of Face and Favour. The analysis demonstrated that

there exists an isomorphism between the psychological process of resource allocator in the theoretical model of Face and Favour and the Confucian model of Mind

con-structed by the author through the integration of the Confucian concepts of benevo-lence, righteousness and propriety. Benevolence (ren) with its emphasis on differential

order corresponds to the expressive component of the relationship (guanxi). In judging

theguanxi, righteousness (yi) corresponds to the rule for social exchange and propriety

(li) corresponds to the overt behaviours resulting from the dialectical con icts

underly-ing the psychological process. Although the theoretical model ofFace and Favour may

be applied to illuminate various types of social interaction within different social groups, consideration of the deep structure of Confucian tradition and the surface structure derived from it is indispensable if we intend to understand why Chinese place