Indonesia’s Foreign Policy toward the U.S.’s

Indo-Pacific Strategy in the Context of

Rising China

Ya-wen Yu

Assistant Professor, Department of Diplomacy and International Relations, Tamkang University

Abstract

This article analyzes Indonesia’s foreign policy in the context of the confrontation between the U.S. and China in the Indo-Pacific region. The U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy first was proposed by President Obama and implemented by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. President Trump further re-arranged the U.S.’s international engagements strictly to make sure “America first”. This article will discuss the following topics. What are the attitudes of Indonesia toward the U.S. and China, the current great powers in the region? How important is Indonesia to the U.S. in its Indo-Pacific strategy? What was and is Indonesia’s foreign policy under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014) and President Joko Widodo (2014 onwards)? How did or do they lead the country to respond to the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy? Finally, what are the Joko Widodo administration’s possible future policies toward Taiwan?

Keywords: Indonesia, Indo-Pacific Strategy, Joko Widodo (Jokowi), Susilo Bambang

Yudhoyono, Taiwan

I. Introduction

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe first mentioned the term “Indo-Pacific” in an August 2007 speech to the Indian Parliament. In 2012, Prime Minister Abe declared the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) strategy as the official Japanese foreign policy in the region. Prime Minister Abe proposed a new security strategy that enlisted potential regional partners, such as the U.S., Australia, and India, in a coalition. These three countries view a rising China as a threat to regional security and wanted to form

a security coalition to deal with China. From this perspective, and also as some scholars have mentioned, we can see the Indo-Pacific strategy as a threat-driven security cooperation.1In other words, the main goal of an Indo-Pacific strategy is to counter China’s growing presence and influence.

In the U.S., with the strong growth of China’s economy and military, China has become a threat to U.S. interests in the Indo-Pacific region since the 2000s. In addition, because a breakthrough in U.S.-India relations pushed Washington to devote more attention to this region, President Obama articulated the concepts of “pivot” or “rebalance” to Asia and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton published an article in 2011 (“America’s Pacific Century”), in which she argued that the U.S. would build a multipronged approach of military cooperation, diplomatic engagement, and free trade negotiation to establish its position in the Indo-Pacific region.2

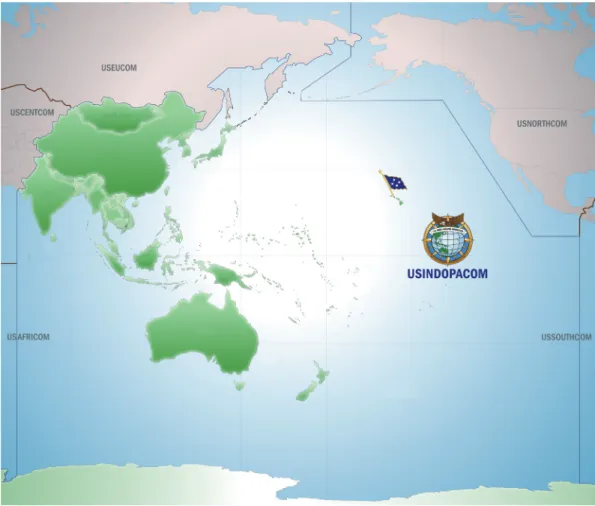

In President Trump’s administration, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson mentioned the “Indo-Pacific region” many times in his talk at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Specifically speaking, the scope of the Indo-Pacific region ranges from the Western Pacific (the U.S.’s territory) to the Indian Ocean (India’s territory) and includes all Southeast and South Asian countries.

The main reason President Obama and President Trump have adopted these policies is to contain China’s rise. Since China became the U.S.’s prime competitor and China President Xi, who has revealed his ambition to assume hegemony in Asia, came to power, both Northeast and Southeast Asia have witnessed conflicts between the U.S. and China. This article analyzes Indonesia’s foreign policy and discusses Indonesia’s recent response to the China/U.S. confrontation in the Indo-Pacific region.

Yujen Kuo, “Japan’s Roles in the Indo-Pacific Strategy,” Prospect Journal, No. 18, October 2018, pp. 29-36.

Hillary Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century,” October 11, 2011, Foreign Policy, <https:// foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/11/americas-pacific-century/>.

Figure 1. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Area of Responsibility

Source: US Indo-Pacific Command, “Area of Responsibility,” September 29, 2019, Accessed, US Indo-Pacific Command, <http://www.pacom.mil/About-USINDOPACOM/USPACOM-Area-of-Responsibility/>.

This article analyzes Indonesia’s foreign policy in the context of the confrontation between the U.S. and China in the Indo-Pacific region. In order to do that, this article will discuss the following important topics. What are the attitudes of Indonesia toward the U.S. and China, the current great powers in the region? How important is Indonesia to the U.S. in its Indo-Pacific strategy? What was and is Indonesia’s foreign policy under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014) and President Joko Widodo (2014 onwards)? How did or do they lead the country to respond to the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy? Finally, what are the Joko Widodo administration’s possible future policies toward Taiwan?

II. Indonesia between China and the U.S.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s pro-investment and infrastructure-centric government has pushed Indonesia closer to China. In 2019, China became Indonesia’s number two investor with an infrastructure drive, and China has beaten Japan to a number of high profile investments, such as the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed train project.3

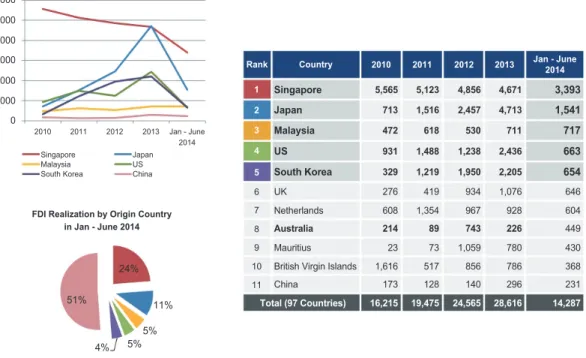

Traditionally, Singapore and Japan have been the largest sources of FDI in Indonesia. Nevertheless, China has risen from 11thin 2014 to a top-3 position in 2017. Please see Figure 2, Table 1 and Table 2 for details.

6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Jan - June 2014 Singapore Malaysia South Korea Japan US China

FDI Realization by Origin Country in Jan - June 2014 51% 24% 11% 5% 5% 4%

Country 2010 2011 2012 2013 Jan - June 2014 Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Singapore Japan Malaysia US South Korea UK Netherlands Australia Mauritius British Virgin Islands China 5,565 713 472 931 329 276 608 214 23 1,616 173 5,123 1,516 618 1,488 1,219 419 1,354 89 73 517 128 16,215 19,475 24,565 28,616 14,287 Total (97 Countries) 4,856 2,457 530 1,238 1,950 934 967 743 1,059 856 140 4,671 4,713 711 2,436 2,205 1,076 928 226 780 786 296 3,393 1,541 717 663 654 646 604 449 430 368 231

Figure 2. FDI Realization in Indonesia by Origin Country in 2014

Source: Nurman Hartono, “Indonesia Investment Outlook and Policy Development,” September 2, 2014, Slide Share, <https://www.slideshare.net/hidayatnurman/indonesia-investment-outlook-and-development>.

Erwida Maulia, “China becomes Indonesia’s No. 2 investor with infrastructure drive,” NIKKEI, February 1, 2018, <https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/China-becomes-Indonesia-s-No.-2-investor-with-infrastructure-drive>.

Table 1. FDI Flows into Indonesia by Country in 2017

Main Investing Countries 2017 (January-June)

Singapore 19.5%

Japan 17.5%

China 16.4%

Hong Kong 7.5%

South Korea 5.8%

Source: Indonesia Bureau for the coordination of investments & Institute of statistics, “Indonesia: Foreign Investment,” September, 2019, Santander Trade Portal, <https://en.portal. santandertrade.com/establish-overseas/indonesia/foreign-investment>.

Table 2. FDI Flows into Indonesia by Industry in 2017

Main Invested Sectors 2017 (January-June)

Metal, Machinery, and Electronic Industry 13.7%

Mining 12.2%

Electricity, Gas, and Water Supply 12.0%

Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry 9.7%

Food industry 8.5%

Source: Indonesia Bureau for the coordination of investments & Institute of statistics, “Indonesia: Foreign Investment.”

Chinese investment was a contentious issue in the 2019 election, as Joko Widodo approached China for more investments. Tom Lembong, the head of Indonesia’s investment board, likened the current Chinese investment spree with Japan’s similar deals in the 1980s and 1990s. As he mentioned, though, most countries that wish to work closely with China try to make it less and less controversial over time. Japanese investment around the world has become well-accepted and completely uncontroversial.4

Karishma Vaswani, “Indonesia election: China’s complicated role in the country’s future,” BBC, April 12, 2019, <https://www.bbc.com/news/business-47905090>.

Therefore, in the 2019 Indonesia election, presidential candidate Mr. Prabowo Subianto used Chinese investment as a bogeyman. Anti-Chinese sentiments have long existed in Indonesia and now are utilized as a political tool. Mr. Prabowo Subinato accused President Joko Widodo of being too soft on China and criticized him for allowing millions of Chinese workers in to work on Chinese-funded projects.5 Mr. Prabowo Subinato has said that, if he becomes president, he will review all of Beijing’s projects in the country. Nevertheless, the news about so-called “millions of Chinese workers” who illegally came to work in Indonesian Chinese funded projects has been proven to be fake news.6

The share of Indonesians who hold favorable views of China has been declining over time. The figure below shows that the percentage of Indonesians who had a favorable view of China decreased from 66% in 2014 to 53% in 2018, the most recent election year in Indonesia. The main reason more and more Indonesians have a negative view of China is because they are concerned about Indonesia’s increasing economic dependence on Beijing.7

Karishma Vaswani, “Indonesia election: China’s complicated role in the country’s future.” Leo Suryadinata, “Anti-China campaign in Jokowi’s Indonesia,” The Straits Times, January 10, 2017, <https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/anti-china-campaign-in-jokowis-indonesia>; Fanny Potkin & Agustinus Beo Da Costa, “Fact-checkers vs. hoax peddlers: a fake news battle ahead of Indonesia’s election,” Reuters, April 11, 2019, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us- indonesia-election-fakenews-insight/fact-checkers-vs-hoax-peddlers-a-fake-news-battle-ahead-of-indonesias-election-idUSKCN1RM2ZE>.

Christine Tamir & Abby Budiman, “Indonesians optimistic about their country’s democracy and economy as elections near,” April 4, 2019, The Pew Research Center, <https://www. pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/04/indonesians-optimistic-about-their-countrys-democracy-and-economy-as-elections-near/>.

73% 62 65 58 59 58 67 70 66 63 55 53 37% 42 38 36 40 34 36

Favorable view of China

Confidence in the Chinese president

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2018

Hu Jintao Xi Jinping

Figure 3. Favorable Views of China among Indonesians

Source: Christine Tamir & Abby Budiman, “Indonesians optimistic about their country’s democracy and economy as elections near.”

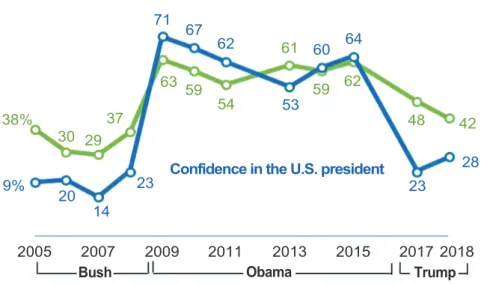

The share of Indonesians who hold a favorable view of the U.S. has also declined. In 2018, 42% of Indonesians said they had favorable views of the U.S., versus 62% who said this in 2015, during Barack Obama’s administration.

38% 30 29 63 59 54 61 59 62 19% 14 71 62 53 64 28 Favorable view of the U.S.

Confidence in the U.S. president

2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2018 Bush 37 48 42 20 23 67 60 23 Obama Trump

Figure 4. Favorable Views of the U.S. among Indonesians

Source: Christine Tamir & Abby Budiman, “Indonesians optimistic about their country’s democracy and economy as elections near.”

III. The U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy and the Geographic Location of

Southeast Asia

The Indo-Pacific region is entering a new era marked by a struggle for supremacy between the U.S. and China. President Trump’s “America First” philosophy attempts to re-arrange America’s international engagements strictly in line with American national interests.

About the “importance” of a country to the U.S. in this region, due to U.S. treaties with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, U.S. conflict with China will most likely occur in Northeast Asia rather than Southeast Asia, even with the contentious South China Sea issue.

Japan is by far the most important U.S. ally in the region, with the third largest economy in the world and highly developed security. Australia is a long-time military ally of the U.S. with significant naval capability. India is a democracy with a significant military and a large population that also is capable of punching its weight against China. All of the above regions, therefore, will be seen by the U.S. as “more strategic” than Southeast Asia. The U.S. does not have strong reliable military allies in Southeast Asia; it has only defense treaties with the Philippines and Thailand, which are susceptible to Chinese influence.

In economic value to the U.S., Southeast Asia also lags behind Northeast Asia. Southeast Asia contributed 6.3% to total U.S. trade in 2017, whereas China, Japan, and Korea accounted for 25.3%. In terms of tourism and student spending in the U.S., Northeast Asia is still far ahead. The only metric where Southeast Asia is more economically important is FDI, in which Southeast Asia has a slightly larger FDI share from the U.S. (mainly in Singapore). In sum, although Southeast Asia is an important economic partner of the U.S., overall, Northeast Asia is more important.

Southeast Asia’s main importance to the U.S. lies in its geography, in the middle of the Indo-Pacific region astride strategically and commercially vital sea lanes and because of its perceived vulnerability to Chinese inducements and pressures. Any loss of a country in this vital maritime lane will be a blow to the U.S. and its allies.

As geographical location enhances the value of Southeast Asia in U.S. eyes, Indonesia is gaining strategic importance. Nevertheless, Indonesia has long developed a non-aligned movement and loathes having to pick a side. Given the recent fracture in ASEAN countries between camps that are pro-China or wary of China, and rumors of an offshore Chinese military base in Cambodia, the luxury of not picking a side might not exist in the future.

IV. Indonesia’s Foreign Policy and Its Response to the U.S.

Indo-Pacific Strategy

The goal of Indonesia’s foreign policy is to maintain regional stability by strengthening cooperation, especially in the economic sector, and focusing on dialogue to settle discords, instead of relying on military alliances. Some Indonesian policy-makers think that “strong positive cooperation” based on mutual understanding is much better than reaction to regional developments based on “perception of threat.”8 To maintain regional stability, Indonesia tries to foster more cooperation and hopes that the growing ties of multilateral economic and cultural cooperation will reduce regional tensions. By doing so, Indonesia also can downplay any attempt to craft a regional counterbalance against China.

The main reason for Indonesia’s reliance on multilateral institution-building is that it lacks a coherent Indo-Pacific policy. There are also three minor reasons that influence Indonesia to adopt this kind of foreign policy. The first reason is due to the fragmentation of the national government itself; each national ministry is divvied up between political parties and milked for patronage resources; thus, ministers tend to compete against each other instead of cooperating. The second reason is due to Indonesia desiring Chinese investment, so Indonesia is wary of taking actions that might jeopardize its relationship with China. As a result, Indonesia simply is passing the buck to ASEAN by stressing its centrality in the Indo-Pacific region. The third reason is due to Indonesia’s problem in power-projecting capability. Militarily, Indonesia

Retno Lestari Priansari Marsudi, “2018 Annual Press Statement of the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia,” January 9, 2018, p. 13, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, <http://fpcindonesia.org/beta/images/files/PPTM%202018%20English. pdf>.

is too weak to challenge China, while its strategic culture, which focuses more on internal security, self-reliance, and self-strengthening, prevents it from taking part in an active military alliance that would contain China.

1. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono

President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono thinks that the best policy for Indonesia is to promote peace, to increase mutual restraint, and to work toward “an Indo-Pacific wide treaty of friendship and cooperation.”9 In the case of the South China Sea, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono adopted a multilateral approach to deal with China by persuading China to agree to a code of conduct with ASEAN, which provided rules of engagement between China and ASEAN to settle disputes in a confidence-building process.

Mr. Marty Natalegawa (Indonesia’s former foreign minister, 2009-2014) has supported President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s foreign policy outlook, namely “a million friends and zero enemies,” which also is known as an “all-direction foreign policy.” President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono wanted to set Indonesia as a global actor. Nevertheless, as the political analyst Dr. Yohanes Sulaiman has mentioned, despite President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s focus on all-direction foreign policy, it is difficult to see any breakthroughs in Indonesia’s strategy regarding the South China Sea and the Indo-Pacific as a whole.10

2. President Joko Widodo’s Foreign Policy

Prashanth Parameswaran, Senior Editor of The Diplomat based in Washington, D.C., has commented on what Indonesia’s foreign policy will look like in President Joko Widodo’s second term. Parameswaran mentioned that Indonesia’s foreign policy has always been “free and active,” as its former Vice President Mohammad Hatta has

Marty Natalegawa, “An Indonesian Perspective on the Indo-Pacific,” The Jakarta Post, May 20, 2013, <https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/05/20/an-indonesian-perspective-indo-pacific.html>.

Yohanes Sulaiman, “Whither Indonesia’s Indo-Pacific Strategy?” Asie. Visions, No. 105, January 2019, pp. 13-14.

referred to as Indonesia playing a “bebas-aktif” (free and active) role in world politics. Indonesia especially has emphasized neutrality since its independence. For example, Indonesia hosted the historic Bandung Conference in 1955, which led to the founding of the Non-Aligned Movement.11 By so doing, Indonesia can defend Indonesia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and develop a South-South Cooperation.

President Joko Widodo’s foreign policy can be described as domestic-oriented, focusing much more on keeping friendly relations and bringing investment in from abroad. He is noticeably less active than President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono regarding foreign affairs. Things, however, might change in his second term, as he does not have the looming fear of re-election.12

Trend-wise, the growing U.S.-China rivalry is likely to reinforce the need for Indonesian leadership in the Indo-Pacific region. Since Indonesia has viewed itself as a rising country in Southeast Asia, it tries to formulate an ASEAN response to the world trend.

Prashanth Parameswaran, “What Will Indonesia’s Foreign Policy in Jokowi’s Second Term Look Like?” The Diplomat, April 22, 2019, <https://thediplomat.com/2019/04/what-will-indonesias-foreign-policy-in-jokowis-second-term-look-like/>.

Prashanth Parameswaran, “What Will Indonesia’s Foreign Policy in Jokowi’s Second Term Look Like?”

Figure 5. President Joko Widodo Introduced “ASEAN Outlook on Indo-Pacific” Initiative, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in Conveyed His

Support for This Concept at G20 Summit in 2019

Source: Nur Yasmin, “Several countries express support for Indonesia’s ‘ASEAN Outlook on Indo-Pacific’ Initiative,” Jakarta Globe, July 1, 2019, <https://jakartaglobe.id/context/ several-countries-express-support-for-indonesias-asean-outlook-on-indopacific-initiative>.

3. The Way Joko Widodo Has Responded to the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy

President Joko Widodo made a new policy, called “ASEAN on the Indo-Pacific Outlook” (AOIP), but it seems to be an independent concept from the U.S.’s Indo-Pacific Strategy despite having a similar name.13 The AOIP is much more neutral regarding China and the U.S. and is ASEAN’s take on displaying a more united voice in their redefining of Indo-Pacific geopolitics. The main difference between ASEAN’s

ASEAN,“ASEAN OUTLOOK ON THE INDO-PACIFIC,” June 22, 2019, ASEAN, <https:// asean.org/storage/2019/06/ASEAN-Outlook-on-the-Indo-Pacific_FINAL_22062019.pdf>; William Choong, “Indonesia, ASEAN and the Return of the Indo-Pacific Strategy,” July 17, 2019, Australian Institute of International Affairs, <https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/ australianoutlook/indonesia-asean-return-indo-pacific-strategy/>; RSIS, “ASEAN’s Indo-Pacific

AOIP and the U.S.’s FOIP is that the AOIP focuses more on cooperation, inclusiveness, and neutrality, whereas the FOIP focuses more on security and containment. There are some reports listed below about Joko Widodo and Indonesia’s “Indo-Pacific” concept.

(1) Joko Widodo Introduces the Indo-Pacific Concept at the ASEAN-India Summit in January 2018

Indonesia hopes that a peaceful, stable, and prosperous ecosystem will be formed in the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean in the Indo Pacific Rim. This was conveyed by President Joko Widodo at the ASEAN-India Summit at Rasthrapati Bhawan, India. On that occasion, President Joko Widodo invented another new concept of the Indo-Pacific region fit for so-called ASEAN’s ways. President Joko Widodo said, “I believe that through a mechanism led by ASEAN and through the ASEAN-India partnership an Indo-Pacific region that is peaceful, stable and prosperous can be achieved.”14Joko Widodo further said that the Indo-Pacific concept could be developed naturally based on the ASEAN Cooperation and Friendship Treaty in which all important countries in the region had become parties.

Dilemma: Where To From Here?– Analysis,” August 7, 2019, Eurasia Review, <https://www. eurasiareview.com/07082019-aseans-indo-pacific-dilemma-where-to-from-here-analysis/>; Prashanth Parameswaran, “Indonesia’s Indo-Pacific Approach: Between Promises and Perils,” The Diplomat, March 15, 2019, <https://thediplomat.com/2019/03/indonesias-indo-pacific-approach-between-promises-and-perils/>.

Natalia Santi, “Jokowi Perkenalkan Konsep Indo-Pasifik di KTT ASEAN-India,” CNN Indonesia, January 26, 2018, <https://www.cnnindonesia.com/internasional/20180126074522-113-271697/ jokowi-perkenalkan-konsep-indo-pasifik-di-ktt-asean-india>.

Figure 6. President Joko Widodo Introduces the Indo-Pacific Concept at the ASEAN-India Summit in January 2018

Source: Kantor Staf Presiden Republik Indonesia, “Bertemu PM Modi, Ingin Tingkatkan Kerjasama Ekonomi dengan India,” January 25, 2018, PresidenRI.go.id, <http://presidenri.go.id/ berita-aktual/bertemu-pm-modi-ingin-tingkatkan-kerjasama-ekonomi-dengan-india.html>.

President Joko Widodo thinks that the development of the Indo-Pacific concept must also be conducted in an open, transparent, and inclusive manner based on habit of dialogue based on the desire to cooperate and uphold international law. According to Joko Widodo, with this concept, unhealthy rivalries that lead to power projections can be avoided. Joko Widodo further stated that the development of the Indo-Pacific concept would be good if it were done through strengthening bilateral cooperation, as well as multilateral cooperation, such as ASEAN-India; strengthening regional mechanisms, such as the Indian Ocean Circle Cooperation Association (IORA) in the Indian Ocean; and ASEAN leadership mechanisms, especially the East Asia Summit (EAS) of the Pacific Ocean, linking and integrating mechanisms for cooperation in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

Indonesia hopes that the Indo-Pacific region will become one of the main sources of world economic growth, trade, and industry. The concept of the Indo-Pacific region also was mentioned by Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Lestari Priansari Marsudi in the Annual Press Speech at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs early last January. The foreign minister underlined that maritime cooperation is the key in developing the architecture of the Indo-Pacific region and Indonesia has a strong commitment to enhance maritime cooperation through IORA and EAS.

Besides that, President Joko Widodo said: “I would like to use this opportunity to express appreciation for India’s support of ASEAN centrality. I am optimistic [that] ASEAN and India will be the backbone of Indo-Pacific cooperation.”15

(2) President Joko Widodo presented on the Indo-Pacific Concept at the East Asian Summit in November 2018

When giving a speech in Singapore at the 13thEast Asia Summit of the 13thEast Asia Summit plenary session, President Joko Widodo presented the Indo-Pacific concept. First, he mentioned that, at the 2014 EAS meeting, he conveyed the vision of a “World Maritime Axis” of Indonesia. At that time, Joko Widodo stressed the importance of increasing maritime cooperation, not only in the Pacific Ocean, but also in the Indian Ocean. President Joko Widodo conceptualized the Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean as a single geo-strategic theater. As he said: “We need to keep the Indian Ocean - Pacific Ocean peaceful and safe. It will not be used as a competition for natural resources, territorial disputes and maritime supremacy.”16

Natalia Santi, “Jokowi Perkenalkan Konsep Indo-Pasifik di KTT ASEAN-India.”

Kantor Staf Presiden Republik Indonesia, “Presiden Jokowi Presentasikan Konsep Indo-Pasifik di EAS,” November 15, 2018, Kantor Staf Presiden Republik Indonesia, <http://ksp.go.id/ presiden-jokowi-presentasikan-konsep-indo-pasifik-di-eas/>.

Figure 7. President Joko Widodo Conveys Indo-Pacific Concept to the 13thEast Asia Summit in 2018

Source: Azis Kurmala, “Indonesia conveys Indo-Pacific concept to East Asia Summit,” ANTARA NEWS, November 16, 2018, <https://en.antaranews.com/news/120550/indonesia-conveys-indo-pacific-concept-to-e-asia-summit>.

In addition, President Joko Widodo reminded that maritime cooperation also continues to be developed with ASEAN. At present, Indonesia and ASEAN are developing a concept of “Indo-Pacific” cooperation. Indonesia also conducts consultations with partner countries. Therefore, Joko Widodo expressed his appreciation for the support of ASEAN partners who emphasize the centrality of ASEAN, including the development of the Indo-Pacific concept.

After a long period of consultation, Joko Widodo thinks it is time. At this time in the EAS, countries in the region should discuss more openly “Indo-Pacific” cooperation. In President Joko Widodo’s view, the development of Indo-Pacific cooperation is important to emphasize several principles, including cooperation, inclusiveness, transparency, openness, and respect for international law.

(3) The ASEAN Summit Adopts President’s Joko Widodo’s Proposal on the Indo-Pacific Outlook in June 2019

ASEAN’s outlook regarding the Indo-Pacific, which was proposed by Indonesia, has been adopted at the ASEAN Summit in Bangkok. The ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific has become more important in the midst of current world developments. “The trade war between the United States and China has not improved,” President Joko Widodo said. It is feared that the trade war will become a ‘multi-front war,’ Joko Widodo said. President Joko Widodo said that ASEAN must be strong, ASEAN must unite, and ASEAN must be able to become the motor of peace and stability in Southeast Asia. In addition to the Indo-Pacific issue, in the ASEAN Summit Plenary Meeting, President Joko Widodo called for an affirmation of ASEAN’s commitment to the completion of the Regional Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) negotiations.17

Figure 8. ASEAN Summit Adopts ASEAN Outlook on Indo-Pacific in June 2019

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, “ASEAN Summit Adopts ASEAN Outlook on Indo-Pacific,” June 23, 2019, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, <https://kemlu.go.id/portal/en/read/388/berita/asean-summit-adopts-asean-outlook-on-indo-pacific>.

Juko Susilo, “KTT ASEAN adopsi Outlook ASEAN mengenai Indo-Pasifik,” ANTARA NEWS, June 23, 2019, <https://www.antaranews.com/berita/924113/ktt-asean-adopsi-outlook-asean-mengenai-indo-pasifik>.

V. Concluding Remarks and the Joko Widodo Administration’s Possible

Future Policies toward Taiwan

As discussed above, we understand the fact that Southeast Asia is getting more and more important to the U.S. today in the context of heightened China/U.S. rivalry in the Indo-Pacific region. Indonesia has become the U.S.’s potential significant ally. Indonesia’s importance will be due to its geographic location in the Indo-Pacific region. Indonesians have a history of distrust towards both China and the U.S.; therefore, they have always prioritized neutrality. Even in his pro-investment foreign policy, President Joko Widodo has been extremely cautious in getting closer to China and has even displayed a strong stance against China in protecting Indonesia’s national sovereignty. Even with all his caution, anti-Chinese sentiment still rises very easily when political power is put behind it, in this case by Mr. Prabowo Subianto, the challenger of Joko Widodo during the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections.

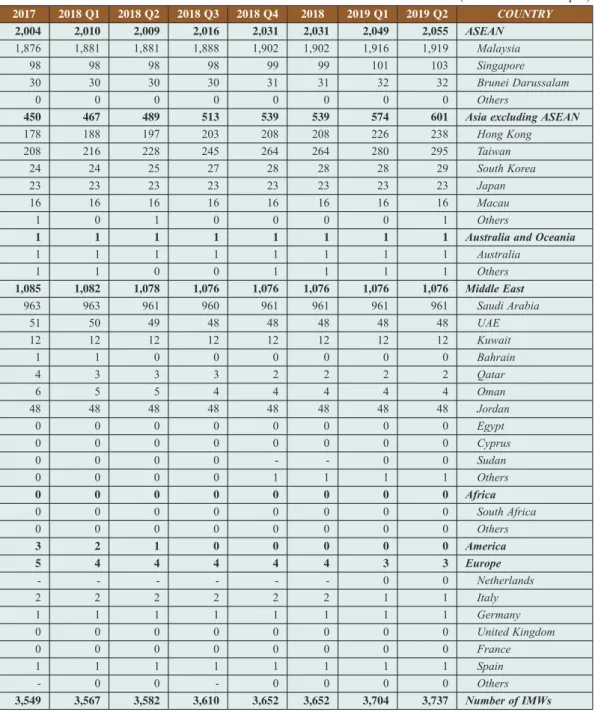

Undeniably, Taiwan has not been the main focus for Joko Widodo’s foreign policies, but there have been some attempts between Indonesia and Taiwan to increase cooperation due to the historical friendliness between the two countries. In 2014, Taiwan overtook Hong Kong as the third largest destination for Indonesian migrant workers, below only Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. The number of Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMW) in Taiwan has risen from 180,000 in 2012 to 295,000 in 2019 Q2,18 representing a 64% total increase under Joko Widodo’s administration. Please see the table listed below.

Bank Indonesia, “Number of Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMWs) by Host Country,” September 29, 2019, pp. 220-221, Bank Indonesia, <https://www.bi.go.id/seki/tabel/TABEL5_30.pdf>.

Table 3 Number of Indonesian Migrant Workers by Host Country (Thousands of People) 2017 2018 Q1 2018 Q2 2018 Q3 2018 Q4 2018 2019 Q1 2019 Q2 COUNTRY 2,004 2,010 2,009 2,016 2,031 2,031 2,049 2,055 ASEAN 1,876 1,881 1,881 1,888 1,902 1,902 1,916 1,919 Malaysia 98 98 98 98 99 99 101 103 Singapore 30 30 30 30 31 31 32 32 Brunei Darussalam 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Others

450 467 489 513 539 539 574 601 Asia excluding ASEAN

178 188 197 203 208 208 226 238 Hong Kong 208 216 228 245 264 264 280 295 Taiwan 24 24 25 27 28 28 28 29 South Korea 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 Japan 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 16 Macau 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Others

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Australia and Oceania

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Australia 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 Others 1,085 1,082 1,078 1,076 1,076 1,076 1,076 1,076 Middle East 963 963 961 960 961 961 961 961 Saudi Arabia 51 50 49 48 48 48 48 48 UAE 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 Kuwait 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Bahrain 4 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 Qatar 6 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 Oman 48 48 48 48 48 48 48 48 Jordan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Egypt 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Cyprus 0 0 0 0 - - 0 0 Sudan 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 Others 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Africa 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 South Africa 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Others 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 America 5 4 4 4 4 4 3 3 Europe - - - 0 0 Netherlands 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 Italy 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Germany 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 United Kingdom 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 France 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Spain - 0 0 - 0 0 0 0 Others 3,549 3,567 3,582 3,610 3,652 3,652 3,704 3,737 Number of IMWs Source: Bank Indonesia, “Number of Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMWs) by Host Country,”

p. 220.

Accordingly, Indonesian migrant workers now are the largest group of migrant workers in Taiwan, eclipsing Vietnam and Thailand in the past decade. Indonesian migrant workers now represent 38.4 percent of foreign labor in Taiwan, of a total of

706,000 foreign workers.19 That number is expected to increase, as Taiwan recently printed the first batch of direct hiring visas for Indonesian migrant workers. The Taipei Economic and Trade Office has issued the direct hiring visa for Indonesian migrant workers recruited directly by Taiwan factories since July 2019.

In Taiwan, there is a Direct Hiring Service Center under the auspices of the Taiwan Ministry of Labor and the Indonesia Economic and Trade Office, which runs processes in Taiwan (the selection process), including issuing recruitment letters, visiting factories in need, providing recruitment information, and legalizing documents along with things that must be prepared before entering Taiwan.

While in Indonesia, there is a National Agency for the Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers that helps with the selection of workers, creating a database of workers and making the necessary documents, and the Taipei Economic and Trade Office which helps with issuing visas and other things needed to leave Taiwan. Based on the consensus of Taiwan and Indonesia, to ensure that this plan can run smoothly, each recruitment campaign is expected to be completed within 2 months.20

Until now, the number of migrant workers in Taiwan has been approximately 710,000, including Indonesian migrant workers, with a total of nearly 270,000. Direct hiring is expected to reduce the cost burden of Indonesian migrant workers who will work in Taiwan and provide guarantees for the protection of human rights and social welfare of Indonesian migrants.

In the 2019 Indonesian general election, Joko Widodo won in Taiwan his largest victory outside of Indonesia: 86.4% or a total number of 72,726 Indonesians in Taiwan voted for Joko Widodo. Indonesian migrant workers in Taiwan have been one of the most vocal groups advocating for Joko Widodo’s presidency.21

Keoni Everington, “Migrant worker count in Taiwan climbs to 706,000, Indonesians largest group,” Taiwan News, June 3, 2019, <https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3716487>. “Taiwan Terbitkan Visa Pertama Direct Hiring Migran Indonesia,” TEMPO, July 11, 2019, < https://dunia.tempo.co/read/1223618/taiwan-terbitkan-visa-pertama-direct-hiring-migran-indonesia>. “Jokowi-Ma’ruf Menang Telak di Taiwan, Ini Rinciannya,” Tribun news, April 24, 2019, <https:// www.tribunnews.com/internasional/2019/04/24/jokowi-maruf-menang-telak-di-taiwan-ini-rinciannya>.

To sum up, President Joko Widodo’s pro-trade and pro-investment policies are expected to bring Indonesia and Taiwan closer economically. In addition to the large and growing number of Indonesian migrant workers and students living in Taiwan, the fact that President Joko Widodo won massively in Taiwan is bound to bring Taiwan more under his radar. Indonesia’s policy still strictly adheres to a One China policy, with little news regarding the relationship between the two countries, which seems to be festering in the background.

In 2016, Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen launched “The New Southbound Policy.” The New Southbound Policy aims to enhance bilateral cooperation and exchanges between Taiwan and Southeast Asia. Therefore, this policy would be a great step for Taiwan in the right direction, which needs to be socialized better to the Southeast Asian populations.