Zara在台灣的消費者行為研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(3) Acknowledgment. The present study has come true thanks to the support and kindness of persons, for whom I will be always immensely grateful. First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Robert Chen. His guidance and his knowledge about culture studies and fashion have been greatly helpful for my work. I must also highlight his patience throughout all the meetings and emails. I’m also thankful for Professor Katherine Chen, who recommended me in the beginning such a good advisor. As well, I really appreciate Professor Kuo Cheng and Professor. 治 政 Yan Chong Hsien, for offering their time and advice 大 to my thesis. Their comments, 立 opinions and encouraging words made me feel even more eager to conduct this. ‧ 國. 學. research. I give you a big ‘Thank You’ to all of you, my dear Professors.. ‧. Undoubtedly, without the help of my interviewees, all of this would not have been. sit. y. Nat. possible. I’m deeply thankful for you to be willing to participate in my work and to. io. you. Thank you so much, my dear new friends.. al. er. give me such useful and interesting insights and feedback. I have learned a lot with. n. v i n Ceffort Certainly, I felt moved by the Chamber of Commerce in Taipei h e nthegSpanish chi U. did for me to contact Zara representatives in Taiwan. I’m really thankful for such a kind gesture. Muchas gracias, compañeros.. Definitely, thank you to my beloved parents and brother, for accompanying me in this four-year Taiwanese adventure, and for giving me moral support whenever it was needed. Thank you for believing in me, my dear family. As well, thank you to my Taiwanese family 吳任 and great friends in Taiwan, for making me feel like home. Without you, I wouldn’t have survived. You have incredibly fulfilled my life with happiness and joy. You have made Taiwan touch my.

(4) heart. And I am more than happy to welcome you back in Spain. 非常感謝! Last but not least, I would like to mention Enrique and his family. Across distance, I have felt your words of encouragement and love. Thank you, my special family. I am not sure how many times I’ve written ‘thank you’ or ‘thankful’. But let me take a bow and say it again, this time out loud: THANK YOU!. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. ii . i n U. v.

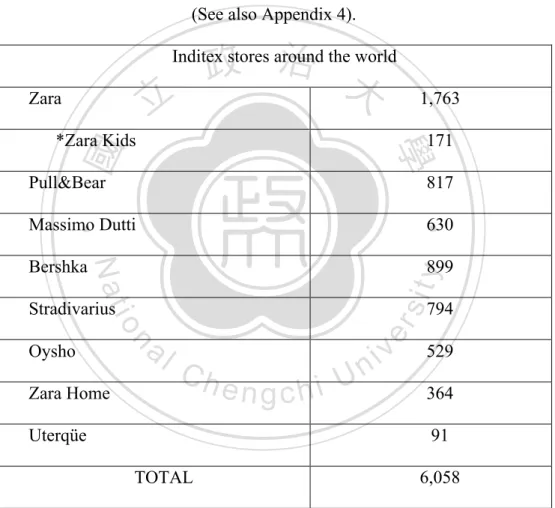

(5) Abstract Zara is one of the largest fast fashion retailers in the world. Since its first opening in 1975 in Spain, it has reached the total number of 1,763 stores around the world. Asia is a key expansion market for the Inditex Group (Textile Design Industry), which is the holding company of Zara and seven other chain stores. As a pioneer in fast fashion, Zara absorbs the trends and bring them to the stores in the shortest time possible at affordable prices. Zara arrived in Taiwan in 2011 and since then, the success is significant. The purpose of this study is to explore the perceptions and motivations behind the consumer behavior in Zara among Taiwanese consumers. In. 治 政 大we examine the theories and order to understand the fashion and social phenomenon, 立. concepts related to fashion, as well as the background of Zara in its home market and. ‧ 國. 學. its impact worldwide, especially in Taiwan. Apart from the literature review, we will. ‧. conduct interviews with Taiwanese customers of Zara and store assistants in Taiwan.. sit. y. Nat. As well, we will include observations from Zara in Spain. Unlike previous case. io. al. n. cultural perspective.. er. studies of Zara, which have a business focus, we address the present study from a. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Keywords: Zara, Inditex, Taiwan, fast fashion, consumer behavior. iii .

(6) 中文摘要 Zara是世界上最大的快速時尚零售商之一。從1975年第一家Zara開設於西班牙, 至今Zara在世界上總共有1,763家分店。亞洲對Inditex來講是一個重要的擴展市場。 Inditex集團(紡織品設計企業)是時裝控股公司,旗下擁有Zara和其他七個品牌。 身為一個快速時尚開拓者,Zara以最快的速度及合理的價格來體現最新潮流時尚。 Zara在2011年進駐台灣,從此這品牌非常成功。本研究是從文化的觀點分析探討 台灣的Zara消費者行為。為了瞭解這個時尚與社會現象,我們檢驗關於時尚的理. 政 治 大 也採訪在台灣的Zara消費者和店員,並在西班牙Zara進行實地研究調查。 立. 論與概念,以及Zara在國內市場和全世界產生的影響。除了文獻探討之外,我們. ‧ 國. 學. 關鍵字:Zara、快速時尚、消費者行為、時尚學. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv . i n U. v.

(7) Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................... iii Chinese Abstract 中文摘要 ......................................................................... iv Table of Contents ........................................................................................... v Table of Figures .............................................................................................. viii Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................. 1 1.1 Motivation............................................................................................... 1. 政 治 大. 1.2 Purpose ................................................................................................... 3. 立. 1.3 Research question .................................................................................. 5. ‧ 國. 學. 1.4 Method .................................................................................................... 6. ‧. 1.5 Thesis structure ...................................................................................... 7. sit. y. Nat. Chapter 2. Literature Review ....................................................................... 9. n. al. er. io. 2.1 Interpretations of fashion ...................................................................... 9. Ch. i n U. v. 2.2 Sociological discourse ............................................................................ 11. engchi. 2.3 Fashion as a social phenomenon ........................................................... 15 2.3.1 Fashion and symbolic consumption ................................................. 17 2.3.2 Fashion and anxiety ......................................................................... 19 2.4 Haute couture and Prêt-à-porter.......................................................... 21 2.4.1 Retailing and global fashion ............................................................ 23 2.5 Mass fashion and fast fashion ............................................................... 24 Chapter 3. Zara: an Overview ...................................................................... 28 v .

(8) 3.1 Inditex, Zara and Amancio Ortega ...................................................... 29 3.1.1 Zara: Business model ....................................................................... 34 3.1.2 Zara: Marketing and (zero) Advertising .......................................... 37 3.2 Zara: Current situation ......................................................................... 39 3.2.1 Zara in Spain .................................................................................... 39 3.2.2 Zara expansion worldwide ............................................................... 41 3.2.3 Zara in Taiwan ................................................................................. 47. 政 治 大. Chapter 4. Research and Analysis ................................................................ 52. 立. 4.1 Interviews with Zara Taiwanese consumers ....................................... 55. ‧ 國. 學. 4.1.1 Perception of Zara in Taiwan ........................................................... 55. ‧. 4.1.2 Taiwanese style and Zara ................................................................. 59. sit. y. Nat. 4.1.3 Value of Zara in Taiwan .................................................................. 62. n. al. er. io. 4.1.4 Position of Zara among other brands in Taiwan .............................. 65. Ch. i n U. v. 4.1.5 Impacts of Zara on the consumer ..................................................... 67. engchi. 4.1.6 Impacts of Zara on the consumer’s daily life ................................... 71 4.1.7 Reason of Zara’s popularity in Taiwan ............................................ 74 4.2 A field trip with a fashion consumer .................................................... 78 4.3 Interviews with Zara store assistants ................................................... 84 Chapter 5. Conclusion ................................................................................... 88 5.1 Discussion ............................................................................................... 92 5.2 Limitations of study ............................................................................... 95 vi .

(9) 5.3 Further research .................................................................................... 97 Appendices ...................................................................................................... 99 Reference ......................................................................................................... 110. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii . i n U. v.

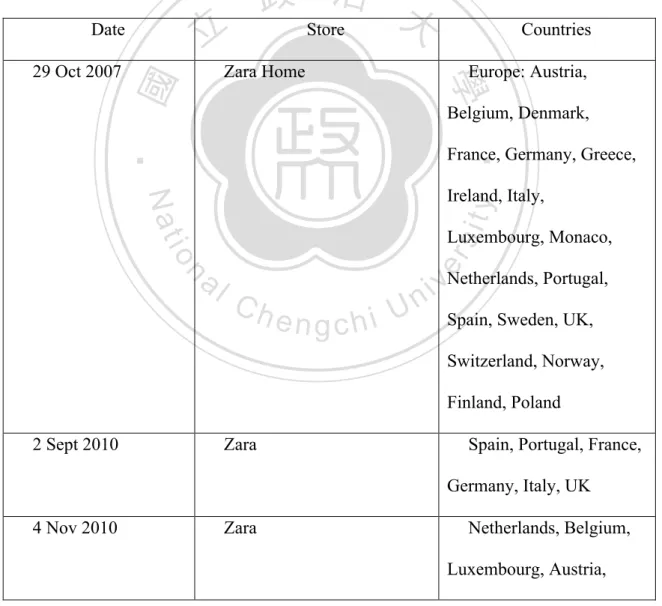

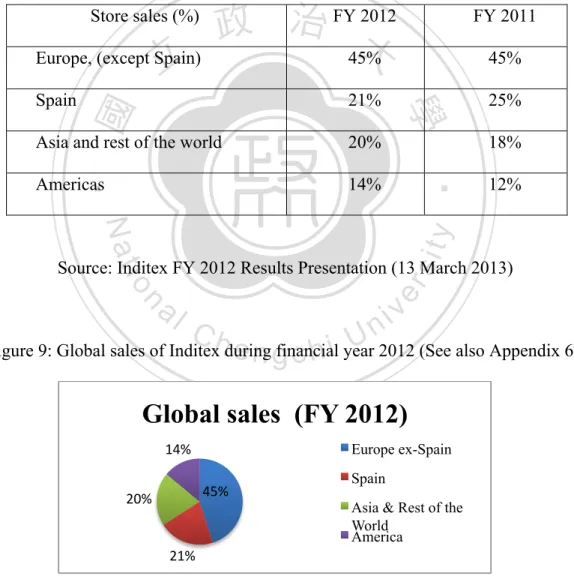

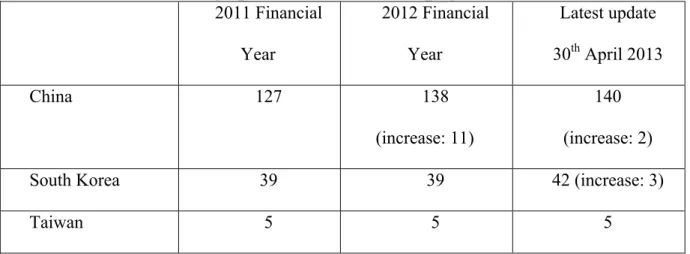

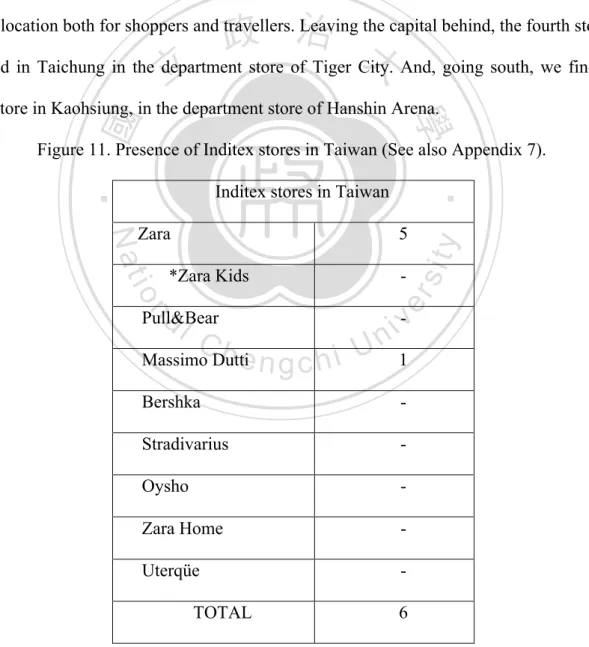

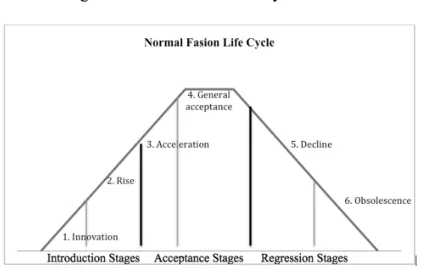

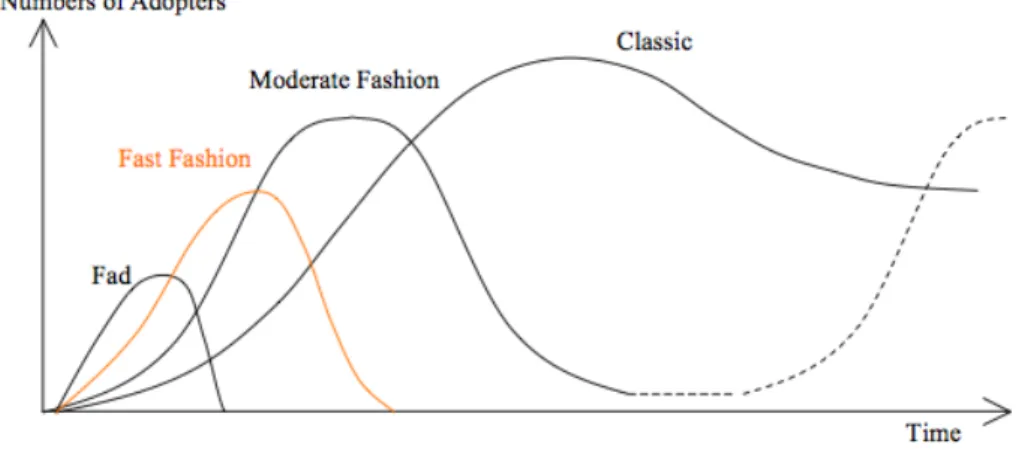

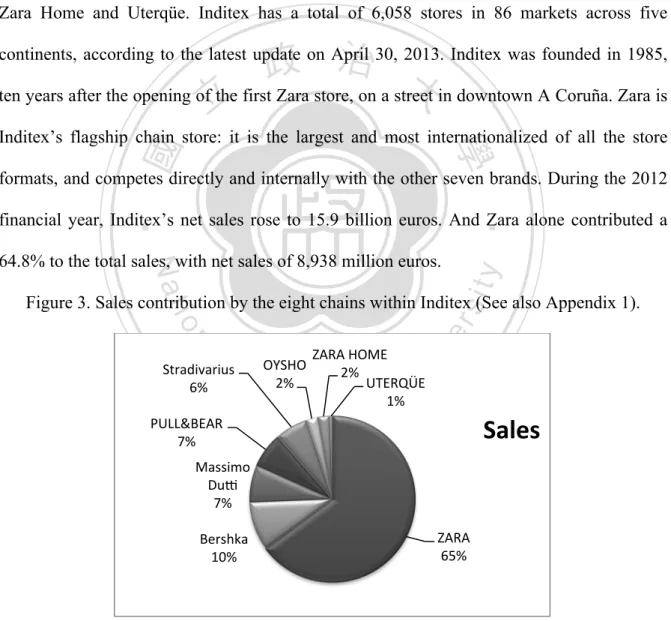

(10) Table of Figures Figure 1. A normal fashion cycle model……………………………………….…....26 Figure 2. Comparison among fad, fast fashion, moderate fashion and classic..…….27 Figure 3. Sales contribution by the eight chain stores within Inditex (See also Appendix 1)…………………….……………….………………..….…...………29 Figure 4. Comparison of sales percentages between Zara stores and the other seven brands, during the financial years of 2011 and 2012 (See also Appendix 2)……………….……………….………...……….……….………...…………...30 Figure 5. Business model of the Inditex Group (See also Appendix 3)………....…..35. 治 政 大by the eight retail formats Figure 6. Inditex stores open around the world, classified 立. (See also Appendix 4)………………………………....……...…………………..41. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 7. History of global online sales of the chain stores in Inditex (See also. ‧. Appendix 5)……………...……….………….……………….……….………….42. sit. y. Nat. Figure 8. Global sales of Inditex during the financial years of 2012 and 2011 (See. io. er. also Appendix 6)…...…………...……….......……………………........................44 Figure 9. Global sales of Inditex during financial year 2012 (See also Appendix. al. n. v i n Ch 6)………………...….……………………………………………….....................44 engchi U. Figure 10. Zara stores in Asia during the financial years 2011, 2012 and latest. update..………………...……...………………………………………….….……45 Figure 11. Presence of Inditex stores in Taiwan (See also Appendix 7)……….........47 Figure 12. Zara cover story in magazine 遠見 Global Views Monthly………...…..49. viii .

(11) Chapter 1. Introduction 1.1 Motivation To be more specific, two events motivated me to work on this thesis. The first one comes from a conversation. Zara opened its first store in Taiwan, exactly on the first floor of the world’s second highest building of Taipei 101, on the 5th of November in 2011. That day I called my mother that she had no need to send me more packages with Zara clothes. Sadly she told me that the Zara store in our town just shut down. I was shocked: Zara, one of the world’s largest clothing and accessories retailers, is closing down stores in. 政 治 大 more commonly known as Inditex group, is one of the largest fashion distribution groups 立. the country where it was born. Industria de Diseño Textil, S.A. (Textile Design Industry). ‧ 國. 學. worldwide and Zara is its flagship chain store. In the financial year of 2012, Inditex’s net sales rose by 16% from 2011, to 15.9 billion euros (Inditex.com) thanks to the expansions in. ‧. America and Asia, (being this latter market where Inditex has grown most), in contrast to a. sit. y. Nat. Europe with little movement and, a Spain suffering the worst economic recession in its. al. er. io. history, with drastic cuts in public funds and consumption at its lowest points. In contrast,. v. n. Zara’s success in further regions such as America and Asia is increasing: In Asia alone, Zara. Ch. engchi. i n U. opened 11 new stores during the first months of 2013 (latest update 30th April), reaching a total of 326 stores nowadays. The second event dates back to my first year in Taiwan, in 2009. On a group night out in Taipei, I wore a non-real leather purple jacket I bought during the summer sales back in Spain, an item I was long time yearning for and which I decided only to wear for special occasions. That night my jacket was stolen, in one of the safest countries in the world. That was the first time I realized how treasured Zara items could be. Unconsciously, I viewed. . 1 .

(12) myself having my first temper tantrums regarding to a fashion item: “it was not just simply a jacket; it was from Zara, my Zara jacket!” On the one hand, the first event made me look deeply at the success Zara is achieving within the Taiwanese market and more precisely, within its society. “Zara must be spread all over the world far and wide. We first have to open in the most important cities to be known, so people (and future customers) see and buy our clothes. Then, we continue opening where it’s nearest to urban areas, to establish our presence”, said Amancio Ortega, co-founder of Inditex group and the leading figure behind Zara. Inditex is present in 86 markets across five. 政 治 大 Zara stores in Taiwan. Since its arrival in 2011, the brand has become very popular among 立 continents, with a total of 6,058 stores, from which 1,763 are Zara. Currently there are 5. ‧ 國. 學. Taiwanese consumers. It is interesting to explore their consumption motivations, whether it is due to merely the clothing quality and/or affordable prices, or there are other motivations. ‧. that go beyond.. sit. y. Nat. On the other hand, the second event made me reflect on the influence that fashion. al. er. io. clothing and brands can have in people’s behavior and to a further extent, the identity itself.. v. n. As Umberto Eco wrote in 1973, “I speak through my clothes.” In our daily life we attend a. Ch. engchi. i n U. “society of the spectacle”, where our selves consist essentially in the image reflected in the eyes of others. Consciously or not, we create an identity of ourselves through clothing and, through what we believe a specific clothing means within a particular society (included the correspondent brand and fashion style). Thus, we want to analyze whether Taiwanese also speak about themselves by purchasing or wearing any Zara item, and which consequently influences in their consumption behavior in Zara. In regard to our research, this thesis will focus on the consumption behavior of Taiwanese. . 2 .

(13) consumers in Zara stores in Taiwan, from a cultural perspective.. 1.2 Purpose The present thesis aims to examine the phenomenon surrounding Zara among Taiwanese consumers. According to Monneyron (2005), “fashion, as a concept and as a recent social phenomenon, is created in Western societies” (p.15). Nevertheless, nowadays, and in any kind of society, when does fashion really become a social phenomenon? Therefore, we want to observe whether we are witnessing a fashion and social phenomenon of Zara in Taiwan.. 政 治 大 Zara entered the Taiwanese market in 2011, the Spanish presence was, and still is, 立 And, why should we choose Zara over other fashion brands existing in Taiwan? Before. ‧ 國. 學. represented by 10 companies established in Taiwan (ICEX, 2011). Among them, only one belongs to the fashion sector, Flagship Fashion Trading Co LTD, which is responsible for. ‧. importing clothes and accessories of Mango in the Taiwanese market. This fashion brand. sit. y. Nat. established itself in the Asian market with its entry into Taiwan in 1995. Currently, there are. al. er. io. in Taiwan a total of 25 Mango stores. Opening their first store in 1984 in Barcelona and now. v. n. with over 2,000 stores in 140 countries, Mango is since 1998, the second largest exporter in. Ch. engchi. i n U. the Spanish textile sector - right behind Inditex group, with Zara as its flagship chain store. Nevertheless, although the path in Taiwan for Mango is long, the overall feeling about Zara among Taiwanese consumers has made an unprecedented effect, only comparable with Japan’s Uniqlo, the fourth largest specialty apparel retailer worldwide (Uniqlo.com). The two giant clothing retailers are competing in Asia, the unquestionably hottest retail market in the world, and Taiwan, indeed, plays an important piece of their global expansion strategy. Both share similar target demographics and store expansion ambitions but each has its own. . 3 .

(14) business model, and both equally successful. At the moment, Zara has opened in Taiwan five stores (since 2011), compared to the 27 stores of Uniqlo (since 2010). Meanwhile, Uniqlo has many more stores (1,120) in Asia than Zara (326). On the other hand, the Spanish brand has more presence in the rest of the world with 1,610 stores, while Uniqlo has ‘only’ 17 stores (Fastretailing.com). Therefore our thesis has decided to study the case of Zara in Taiwan as no other Spanish fashion reference has ever made such an impact in this country before, in a society that usually takes fashion influences from its Asian neighbors, mostly from Korea and Japan.. 政 治 大 popular music, and especially, fashion and cultural magazines which cover all latest fashion 立. Taiwanese clothing styles are influenced by media culture, such as movies, television,. ‧ 國. 學. trends (both local and foreign) or social events where the stars wear the newest designs. Although Taiwanese clothing styles are inspired by Western and Eastern flavors, consumers. ‧. add a touch of Taiwanese unique style, which is a fusion of local customs and culture.. sit. y. Nat. Fashion in Taiwan sticks to the traditions but it always keeps an eye on the newest trends of. al. er. io. the global fashion panorama. However, the phenomenon of Zara in Taiwan looks impressive,. v. n. if we take into account the following two facts: one, that the Taiwanese market is. Ch. engchi. i n U. experiencing a new wave of foreign brands, while coexisting with local brands, and two, that Taiwan consequently lives in a highly competitive environment of fashion brands and retailers. So, how does Zara attract customers in Taiwan and to the rest of the world? First of all, there is no advertising: “we don’t want to create a perception or press the customers with a specific collection or clothes,” says Jesús Echevarría, director of communication of Inditex (Martínez, 2012, p. 73). As Martínez (2012) writes, Amancio Ortega, the man behind the success of Zara, considers that “the best advertising is being in the best street” (p. 149).. . 4 .

(15) Apart from the element ‘store’, Zara’s success is mainly due to the importance given to the rapid turnover of collections: Zara introduces new models twice a week, which makes customers visit the store frequently in search of more and more fashionable items, in a way to keep them updated, or to put in other words, in a way to create expectations on them, as items are produced in limited edition. Therefore we agree with Martínez (2012) when he points out that for the Inditex Group, the most important factor to consider is time (p. 131). These recipes have, so far, worked in Taiwan and Zara keeps on expanding its global fashion throughout the country. Therefore, it is very interesting to analyze such fashion and. 政 治 大. social phenomenon in Taiwan, a country that keeps up with the latest international trends. 立. while maintaining its local style.. ‧ 國. 學. Previous studies about Zara conducted in Taiwan have been focused on the business models of Zara and its comparison, on the one hand, with luxury brands such as Armani or. ‧. LVMH, and on the other hand, with retailer Uniqlo. However, our study will analyze Zara as. sit. y. Nat. a global brand from a cross-cultural perspective, by understanding Zara in its home market. n. al. er. io. Spain, before focusing on the consumer behavior of Zara within the Taiwanese market.. 1.3 Research Question. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Taiwan, the main competitor of Zara is Uniqlo. The increase of international fashion brands has put great pressure on Taiwanese clothing companies, says Alexander Wu, head designer for men’s wear at Shiatzy International Co. Ltd., the Taiwan-based company behind the famous Shiatzy Chen label. He states, “International brands have an appeal in Taiwan. The fierce competiveness of those brands comes from their ability to launch medium-priced products at a high frequency” (Taiwan Today, 2012). In Taiwan, Zara and. 5 .

(16) Uniqlo also compete with NET (founded in Taiwan in 1991), Giordano (established in Hong Kong in 1981), Baleno (established in Hong Kong in 1996) and, Hang Ten (originally a sportswear brand created in California in 1960 and currently owned by Hang Ten Enterprises Ltd, located in Hong Kong). Although it is not long since Zara has landed in Taiwan, Zara has already made an impact in the fashion consumption behavior within the Taiwanese market. But, why and how has it happened? This thesis explores first, what are the Taiwanese consumers’ perceptions towards the brand, from the perspectives of its clothing and store visiting experience. It’s. 政 治 大 Taiwan. Second, we analyze the underlying social and psychological motivations that 立. also important to point out whether the customers knew about the brand before its entry in. ‧ 國. 學. influence the fashion consumption behavior among Taiwanese in the Zara stores in Taiwan. And third, we study their awareness of gaining something more than just a piece of Zara by. ‧. performing such consumption activities.. sit. y. Nat. This thesis will go through these questions, in order to find responses for the phenomenon. n. al. er. io. surrounding Zara among the Taiwanese consumers.. 1.4 Method. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The content of the introductory chapter is collected from various sources concerning to the background and profile of Zara, such as its official website, the results published on March 13, 2013, the Inditex 2011 Annual Report and Martínez’s Zara: Visión y estrategia de Amancio Ortega (Zara: vision and strategy of Amancio Ortega), which talks about the success of the brand, and to an extent, of the whole Inditex Group, as well as the personal history of the co-founder Amancio Ortega. For Zara’s competitors’ information, we use their. . 6 .

(17) official websites. Chapter 2 covers the literature review regarding to the production and consumption of fashion. The content for this chapter is collected through references about fashion theories and concepts, sociological discourses, as well as fashion history, in three languages (Spanish, English and Chinese). Chapter 2 lays the path for Chapter 3, which entirely focuses on Zara. Our sources in Chapter 3 are similar to those in Chapter 1. In Chapter 3 we also include a brief comparison between two issues of the Taiwanese magazine 遠見 Global Views Monthly. As for the second half of the thesis, which concerns the consumption behavior among. 政 治 大 method. We propose open-ended 立 interviews with both customers and staff (store managers. Taiwanese consumers in Zara stores in Taiwan, we choose descriptive qualitative research. ‧. ‧ 國. consumer.. 學. and store assistants) of the Zara stores in Taiwan. We also include a field trip with a fashion. Therefore, in order to address the research questions proposed above, these are the. sit. n. al. er. io 1.5 Thesis structure. y. Nat. methods chosen for the data collection.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The present thesis is intended to offer an introduction to the fashion consumption behavior in Taiwan among Taiwanese consumers, specifically in the case of the fashion retailer Zara, in its stores located in Taiwan. Chapter 1 is an introductory chapter explaining the motivation, the purpose, the research questions, the method proposed and the thesis structure. Chapter 2 has five sections. We review the interpretations of the concept of fashion proposed by several authors, as well as the analysis of sociological discourses. We continue analyzing fashion as a social phenomenon, the symbolic consumption in fashion. . 7 .

(18) and the concept of anxiety. Finally, we go briefly through the history of Haute couture, Prêt-à-porter and retailing, as well as the concepts of mass fashion and fast fashion. Chapter 3 covers the world of Zara by introducing background, current profile and business strategy of Zara and to an extent, Inditex. Then we have a look at its worldwide success, with special focus on the situation in Asia and in Taiwan. Chapter 4 brings the results from open-ended interviews with both customers and staff of the Zara stores in Taiwan, as well as the results from the field trip with a fashion consumer. In this chapter we will also analyze those results. Chapter 5 is the conclusion of the thesis, including discussion, limitations of study and. 政 治 大 All in all, with this thesis structure we want to understand the fashion and social 立. further research.. ‧ 國. 學. phenomenon around Zara in Taiwan by analyzing the consumption behavior among Taiwanese consumers in the Zara stores in Taiwan, from a cultural perspective.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. . Ch. engchi. 8 . i n U. v.

(19) Chapter 2. Literature Review This second chapter will cover the theoretical frameworks that will help us to understand the background of the present study. The present chapter focuses on the production and consumption of fashion, and it will be divided into five sections. We first review the interpretations of the concept of fashion proposed by several authors. After that, we move into the analysis of sociological discourses by reading Veblen, Spencer, Simmel, and Blumer, among others. We continue by exploring fashion in culture as a social phenomenon, as well as the relation of fashion with symbolic consumption and anxiety.. 政 治 大 and retailing. Finally, we look at the concepts of mass fashion and fast fashion, which are 立. Then, we go briefly through the history of fashion in relation to Haute couture, Prêt-à-porter. ‧ 國. 學. particularly closely related to Zara’s principles. Chapter 2 lays the path for the following chapter 3, which entirely regards to the fast fashion empire of Zara, and to a further extent,. ‧. to the Inditex Group.. sit. y. Nat. For the present chapter we have consulted the following books as main sources:. al. er. io. Fashion-ology, by Kawamura, Y. (2005); El vestido habla (“The dress speaks”), by. v. n. Squicciarino, N. (2012); 50 respuestas sobre la moda (“50 answers about fashion”), by. Ch. engchi. i n U. Monneyron, F. (2006); and Fashion theory: a reader, by Barnard, M. (2007).. 2.1 Interpretations of fashion Kawamura (2005, p. 10) cites Wilson to point out the complexity of explaining fashion: “Sometimes fashion is explained in terms of an often over-simplified social history; sometimes it is explained in psychological terms; sometimes in terms of the economy.” Unfortunately, fashion has always encountered difficulties to be taken seriously in the. . 9 .

(20) academic field, “because fashion is considered trivial, frivolous and fun” (Kawamura, 2005, p. 79). Nevertheless, various authors have studied fashion as a subject and given their own interpretation of the concept of fashion. In Squicciarino’s book (2012, p. 149) we learn that for Kybalová, fashion reflects the general lifestyle of the society; each particular human being is subject to it in a spontaneous way and with enthusiasm or in a passive way and unconsciously. Fashion is a cultural component of everyday life; it is its illustration in live colors. Similarly, Kawamura (2005, p. 74) quote Horn and Gurel, who explain: Fashions in any area of life, especially fashions in clothing, are not. 政 治 大 Fashions follow a progressive and irreversible path from inception 立. random and purposeless. They reflect the cultural patterns of the times.. ‧ 國. 學. through acceptance to culmination and eventual decline, and they also tend to parallel to some extent the larger events of history.. ‧. Crane in her Fashion and its social agendas (2000) and Kawamura (2005) apply. sit. y. Nat. Bourdieu’s cultural stratification theory to observe the influence of different social classes. al. er. io. and its tastes in the concept of fashion. This theory aims to understand how different social. v. n. classes respond to cultural goods and material culture in highly stratified societies.. Ch. engchi. i n U. Kawamura (2005, p. 36) illustrates this with the following example: the designers’ position within a certain society, with their cultural tastes and social status, determine the status of products they produce and influence, at the same time, in their audience (p. 96). Crane (2000, p. 8) writes, that, according to Bourdieu, the tastes of working-class men would be based on a “culture of necessity” characteristic of that class, in other words, clothing that was practical, functional, and durable rather than aesthetically pleasing and stylish (for the bourgeoisie). Similarly, according to Bell, quoted by Kawamura (2005, p. 79): “fashion is. . 10 .

(21) the grand motor force of taste, and the influence of fashion goes beyond individual taste and our past perceptions of fashion; it molds our concept of what is beautiful” (p. 79). However, the people’s taste in clothing is only considered fashionable when it is constructed by institutional factors. Squicciarino (2012) explains that during the 17th century, upper classes in France dressed “à la mode”, i.e. according to the French taste, in order to differentiate themselves from the austere dress of the dominant Spanish court (p.151). The word ‘mode’ has been used to refer the constant changes in clothing. Continuing with the perspective of innovation,. 政 治 大 phenomenon of psycho-collective origin and of aesthetic character, that satisfies the need of 立 Squicciarino (2006, p. 156) borrows Squillace’s definition of fashion: fashion is “a social. ‧ 國. 學. innovate and change, as well as the desire to look, to shine, to compete and to win.” Other authors have seen fashion as a way to express oneself. For instance, Kawamura. ‧. (2005, p. 28) quotes Cannon:. sit. y. Nat. Fashion is an inherent part of human social interaction and not the. al. er. io. creation of an elite group of designers, producers or marketers. Because. v. n. of its basis in individual social comparison, fashion cannot be. Ch. engchi. i n U. controlled without undermining its ultimate purpose, which is the expression of individual identity. If self-identity were never in doubt and social comparison never took place, there would be no demand for fashion, and there would be no need or opportunity for style change.. 2.2 Sociological discourse First, we will analyze the concept of imitation in fashion. Kawamura (2005, p. 20) quotes. 11 .

(22) Hunt: “imitation is typically a view from above since it assumes that social inferiors envy superiors and engage in imitative activities to emulate their ‘betters’ in order to gain recognition and even entry into the privileged group.” Similarly, Squicciarino (2012, p. 153-154) uses Spencer’s observation: fashion is intrinsically imitative, as fashion attempts to produce the similarities and the equalization of the inferiors with the superiors through a competitive imitation. It is about rivalry, rather than admiration from inferiors. In Spencer’s theory, upper classes try to differentiate themselves from the lower classes, while these, at the same time, by imitating the upper classes in clothing, try to satisfy their desire to belong. 政 治 大 (2000, p.6), Simmel adds that the highest-status groups sought once again to differentiate 立 to an upper class, and to differentiate themselves from the lower classes. Quoted by Crane. ‧ 國. 學. themselves from their inferiors by adopting new fashions. And this, in turn, starts the cycle all over again. Simmel’s scheme elevates the prestige of the elite to the position of major. ‧. importance in the fashion process. Kawamura (2005, p. 20, 22) continues with Spencer’s. sit. y. Nat. observations when he implies that what is important is not the actual clothes that are worn,. al. er. io. but the wearer’s position in society, which has the power to transform clothing into fashion.. v. n. In addition, Spencer considers two types of imitations: competitive and reverential. The. Ch. engchi. i n U. former is prompted by the desire to assert equality with a person. And, the latter is prompted by reverence for the one imitated. For instance, any modification of dress adopted by a king is imitated by courtiers and spreads downwards; the result of this process is ‘fashion’ in clothing. This is exactly a fundamental principle of the trickle-down theory, which was studied by Spencer in 1896, Veblen in 1899 and Simmel in 1904. As the name implies, fashion is launched at the top of the social structure and eventually works its way down to bottom, i.e. fashion is diffused vertically. In Squicciarino’s book (2006) Simmel positions. . 12 .

(23) the roots of fashion in two tendencies the human being adopts: the tendency for imitation or social equality and the tendency of individual differentiation or change (p. 154). Thus, this creates the following paradox: does fashion encourage a democratized equality or a differentiated exclusion? In other words, whether fashion aggregates individuals of a social class from others, or fashion poses a threat to the upper class, while offering at the same time an opportunity to lower classes to cross that class boundary. According to Squicciarino (2006, p. 155) Veblen in his The Theory of Leisure Class defends the trickle-down theory, as fashion and consumerism phenomena depend on the. 政 治 大 express one’s wealth and to demonstrate consumption without any physical effort. In 立. social structure and not on natural needs. He argues that in its origins, fashion served to. ‧ 國. 學. Kawamura’s study (2005, p. 97) we find that within Veblen’s analytical framework regarding to the institutionalization of the leisure class through consumption activities, he. ‧. identifies three concepts: Conspicuous consumption, conspicuous waste and conspicuous. sit. y. Nat. leisure. The first aims to impress others and demonstrate one’s purchasing power. The. al. er. io. second demonstrate one’s wealth by giving away one’s possessions. And, the third shows a. v. n. life devoted for leisure, without any labor or effort, thus it displays one’s social status.. Ch. engchi. i n U. Veblen’s discussion emphasizes the fact that people acquire goods to compete with others. We copy those of higher status with whom we are competing. Thus, as Kawamura (2005) concludes in Veblen’s analysis, being fashionable has to be something that is envied and desired; otherwise, the consumer would not adopt fashion nor wish to be fashionable (p. 97). Martínez Barreiro (2006, p. 188) limits the validity of the trickle-down conception solely for pre-consumerist societies, such as those studied by Veblen. But it can also be valid for consumerist societies, as those studied by Bourdieu, as the trickle-down theory depends on. . 13 .

(24) the class structure of a capitalist society. However, a society, in which a developed capitalist system favored by the mass production, the mass communication and the social mobility, has gradually removed the strict class distinctions. Squicciarino (2012, p. 165) argues that new fashions appear and stay within the middle-class, who constitutes the main subjects in this contemporary period. Therefore, democratization and social change have allowed fashions to be spread both to the top and to the bottom within a less obvious social hierarchy. Regarding to our contemporary society, fashion is no longer only a trickle-down process, “but also a ‘trickle-across’ process,” argues Veblen, quoted by Kawamura (2005, p. 58).. 政 治 大 similar social levels. Spencer also suggested a similar view when he explained fashion is 立. Such ‘trickle-across’ process claims that fashion moves horizontally between groups on. ‧ 國. 學. intrinsically imitative. In addition, fashion can even be a ‘trickle-up’ or ‘bubble-up’ process, and Kawamura (2005, p. 31) uses Blumer’s proposition when he situates consumers in the. ‧. construction of fashion. Fashion is initiated and adopted from the bottom and it eventually. sit. y. Nat. moves to upper classes. According to Kawamura (2005), as consumers become increasingly. al. er. io. fashionable and fashion conscious in modern and postmodern societies, they themselves. v. n. become producers. For instance, street fashion began as anti-fashion, but ironically it was. Ch. acknowledged as fashion (p. 101).. engchi. i n U. On the other hand, Squicciarino (2006, p. 166, 167) adds a fourth model, which he defines as model of the marionette or trickle-effect. This concept can be present in consumerist societies: although there is a general improvement in life quality, it would still exist an invisible stratified pyramid among social classes. This can be influenced by the increasing “bombing” of advertisement to encourage consumption. Contemporary sociologists have reviewed these earlier works on fashion and most of. . 14 .

(25) them reject the class-differentiation. For instance, Kawamura (2005, p. 30-31) uses Blumer’s perspective, as he replaces the trickle-down theory with the collective selection theory. He argues that the class differentiation model is rather suitable for European fashions in the 17th-19th centuries, but no longer applicable to fashion in contemporary society. For Blumer, “the fashion mechanism appears not in response to a need of class differentiation and class emulation, but in response to a wish to be in fashion, to be abreast of what has good standing, to express new tastes, which are emerging in a changing world”. Thus, fashion is led by the taste of the contemporary collective mass, rather than by the prestige of the elite.. 政 治 大 on the concept of imitation within stratified societies resulting in various theories (the 立 After we have reviewed the theoretical frameworks around fashion, with a special focus. ‧ 國. 學. trickle-down, the trickle-across, the trickle-up and the trickle-effect), we have also observed that fashion is not always influenced by socioeconomic factors, but by the tastes and. ‧. preferences of the individuals themselves. As we can see, by giving a social perspective to. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. fashion, we can better understand the significance of fashion in the society today.. n. 2.3 Fashion as a social phenomenon. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. As Monneyron (2005, p. 15) affirms, we may think that fashion is a universal phenomenon when we look back at prestigious old civilizations, such as the Indian or the Chinese, where ornaments were viewed as an old form of fashion. In Kawamura’s study (2005) we learn from Lipovetsky that clothes are almost universal, fashion is not. Fashion does not belong to all ages or to all civilizations; it has an identifiable starting point in history (p. 26). While Flügel indicates that fashion is linked to a particular society and culture, those of the West (p. 26). However, Cannon strongly disagrees with the perspective. . 15 .

(26) that fashion is a Western phenomenon and argues: “Although the processes of fashion comparison, emulation and differentiation are more noticeably apparent in the rapid changes that characterize systems of industrial production, the same processes are observable or at least inferable in most cultures” (p. 27). Therefore, Kawamura (2005) concludes that fashion is found not only in modern societies but exists in all known societies (p. 27). Kawamura (2005, p. 24) explains that in medieval and early modern Europe, sumptuary laws prohibited people in the subordinate ranks from living or dressing like those above them. However, as industrialism led to a less hierarchical society, people could eventually. 政 治 大 whichever kind of clothing. However, Monneyron (2006, p. 17-18) offers a curious and 立. compete in style of living with those upper classes, and they were entirely free to wear. ‧ 國. 學. contradictory example: during the French Revolution in the 18th century, which promoted liberty and equality, a fashion reserved for a restricted and reduced group of aristocrats was. ‧. born. Again, the freedom of the individual was being questioned. Nonetheless, without the. sit. y. Nat. upper class, fashion would not be possible be fashion as we know today. And here it’s when. al. er. io. Haute Couture appeared for the first time.. n. Monneyron (2006, p. 17) says that if we look back in the 19th century, when fashion was. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. born as a social phenomenon, with rituals and foundation of institutions, we see that the society’s most privileged value lied on the individual – individualistic society. Thus, it’s not a coincidence that the phenomenon of fashion is developed first in England and France, countries in which such kind of society was first established. On the other hand, Kawamura (2005) remarks that social mobility is a fundamental factor for fashion phenomena to occur (p. 24). Indeed, it was the objective of reducing class distinctions emerging from each individual and favored by the political and economic. . 16 .

(27) development, that the origins of fashion lie in the origins of modernity with the growth of industrial capitalism. In regard to the class boundaries that in the industrial societies started to become blurry, therefore, the individuals of these societies have more opportunities, a fact that allowed the emergence of fashion as a phenomenon in many societies. Kawamura (2005, p. 26) concludes by quoting Baudrillard, who considers that fashion can only exists in socially mobile societies: “Modernity is a code and fashion is its emblem”. However, nowadays, the way we see fashion, as social phenomenon within a particular society does no longer look at the social hierarchy, but at the ways that society itself creates. 政 治 大 all the elements that form part of each social group’s interests and daily life can influence in 立 fashion; through art, media, social media, lifestyles, travels, among others. In other words,. ‧ 國. 學. fashion. From fashion designers and famous people in the popular culture to fashion consumers, all of them are participants within this social phenomenon called fashion; to. ‧. some extent they can determine the directions of fashion change. This perspective will help. al. n. 2.3.1 Fashion and symbolic consumption. Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. y. Nat. us to analyze the social phenomenon of Zara in Taiwan among Taiwanese consumers.. i n U. v. To understand the concept of symbolic consumption, Sowden & Grimmer (2009, p. 1) review the definitions of this concept, proposed by several authors. Piacentini and Mailer refer to processes of ‘symbolic consumption’, whereby individuals use products as mechanisms to create, develop and maintain their identities. Dittmar describes a ‘symboliccommunicational’ link through which the symbolic meanings of material possessions communicate aspects of their owner’s identity to themselves and to others. Ger and Belk similarly note that consumption is a communicative act crucial to the constitution of self.. . 17 .

(28) O’Shaughnessy & O’Shaughnessy state that consumers seek “positional” goods to demonstrate group membership, to identify themselves and mark their position – as well as social status-. Thus, the symbolic meanings of material possessions serve to express not only one’s own identity and membership of social groups, but also to perceive the identity of others, according to Belk, Dittmar, Solomon, Christopher and Schlenker. Lury states that possessions are “a means of making visible and stable the basic categories by which we classify people in society”. McCraken and Wattanasuwan consider that material objects embody a system of meanings, which, upon consumption, can be used by individuals as an. 政 治 大 identification. Douglas further argues that consumers define themselves in contrast to others, 立 outward expression of their identity, and as a means of signifying group membership and. ‧ 國. 學. that is, they identify themselves in terms of what they are not. Thus, individuals use consumption to give themselves a sense of belonging as well as an affinity with others who. ‧. make similar statements to, and about, themselves.. sit. y. Nat. Lane (2000, p. 76) in his Jean Baudrillard reviews what the French author stated about. al. er. io. use-value and exchange-value. The first concept arises from productive activity to construct. v. n. something that fulfills a need, such as clothing. The use-value functions as the instrumental. Ch. engchi. i n U. value of an object. While the second one is not related to the commodity itself but to the cost of the labor needed to make the commodity. The exchange-value functions as the economic value. Baudrillard even argues that we must distinguish between the logic of consumption and the logic of use value, exchange-value and symbolic exchange. As an example, he suggests the difference between a wedding ring and an ordinary ring. The wedding ring has symbolic value (the marriage), and in the process of being given becomes a singular object. The ring isn’t periodically changed for one of a different fashion, and so on. While the. . 18 .

(29) ordinary ring, is however, not usually symbolic: it can be changed for one of a different fashion, thrown completely away, be worn to show one’s wealth or be worn purely for personal pleasure. The ordinary ring is non-singular and functions like a sign; it is an object of consumption. Therefore, we can verify later the symbolic value to Zara items from our interviewees’ comments. On the other hand, Martínez Barreiro (2006, p. 195) explains that the growth of consumerism and the diversity of tastes and preferences within the society have changed the way fashion is produced, distributed, commercialized and sold. Therefore, in the process of. 政 治 大 is the image concerning to that specific item and not the material goods itself. In addition, 立 fashion nowadays, material goods create meanings –or even values. What is now consumed. ‧ 國. 學. we believe that marketing and advertising play a significant role in the process of fashion and its symbolic consumption.. ‧. After we have reviewed the literature regarding to symbolic consumption, we can observe. sit. y. Nat. that the symbolic value of material possessions is realized when individuals engage in. al. er. io. consumption of a specific item and thereby express their social identity. We will observe in. v. n. further chapters the degree of influence of the symbolic consumption among Taiwanese. Ch. engchi. consumers when they visit Zara stores in Taiwan.. i n U. 2.3.2 Fashion and anxiety We find two meanings of anxiety in Oxford Dictionaries: 1. A feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease about something with an uncertain outcome; and 2. strong desire or concern to do something or for something to happen. In order to apply anxiety in fashion, we first look at the correlation between newness and. 19 .

(30) fashion. Fashion as a concept and as a phenomenon has gone through various changes along the centuries. Indeed, Kawamura (2005) considers change and novelty are two of the characteristics that fashion has always encompassed, no matter which time period fashion refers (p.6). Both characteristics are highly valued in fashion, probably because they are socially constructed or imposed by institutions (by the fashion system or by fashion designers). Kawamura (2005, p. 6) cites Koenig, who refers to ardent fashion followers as neophilia. He states that humankind receptiveness for anything new is, among many other aspects, in some way essential to fashion-oriented behavior. Like Koenig, Kawamura (2005,. 政 治 大 Fashion doubtless belongs to all the phenomena of neomania, which 立. p. 6) borrows Barthes’s view about newness in fashion:. ‧ 國. 學. probably appeared in our civilization with the birth of capitalism: in an entirely institutional manner, the new is a purchased value. But in our. ‧. society, what is new in Fashion seems to have a well-defined. sit. y. Nat. anthropological function, one that derives from its ambiguity:. al. er. io. simultaneously unpredictable and systematic, regular and unknown.. v. n. The newness component that fashion conveys, can make consumers feel anxious in their. Ch. engchi. i n U. fashion consumption behavior; when they visit a clothing store to look for any new items, they may feel “disoriented” if they have missed any previous item and they find themselves without forms of support and reassurance. As Koenig named (quoted by Kawamura, 2005, p. 6), the ardent fashion followers can experience anxiety and desire when they are eager to own a certain unattainable, authentic or unique fashion item, in order to express themselves, i.e. to offer a particular image. Not only this, but a sense of belonging to a particular social group can make those ardent fashion followers (or consumers) feel anxious if they cannot. . 20 .

(31) get that specific item or brand. Arnold (2001, p. 12) in her Fashion, Desire and Anxiety explores the fashion’s relationship with consumerism and the construction of identities, that if aimed to an extreme, that relationship can lead to self-destruction. She illustrates the dichotomy in fashion by citing Simmel: “fashion on the one hand signifies union with those in the same class, the uniformity of a circle characterized by it, and, at the same time, the exclusion of all other groups.” Arnold continues by explaining that dress can be used as an indicator of group identity, including all those who adhere to particular tenets of taste and style, but this. 政 治 大 We can apply the concept of anxiety in our case of Zara. Products in Zara stores are 立. necessarily excludes anyone who does not adopt the group’s dress codes.. ‧ 國. 學. limited edition, and it makes a win-win situation: On the one hand, it catches customers on going back often to the store, as it creates expectations with the introduction of new models. ‧. al. er. io. sit. Nat. them to be returned; hence, there are almost non-existent stocks.. y. twice a week. On the other hand, products can thus be sold at a full price, without having. n. 2.4 Haute couture and Prêt-à-porter. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Monneyron (2006, p. 21) traces back to the beginnings of haute couture (literally “high dressmaking”, and commonly known as “high fashion”). According to Monneyron (2006, p. 22), two factors led to the appearance of haute Couture: 1. An emergent middle-class, and 2. Clothing was no longer subject to political strings and public life, which laid the path for aristocracy, in order to differentiate themselves. The history of fashion considers the English Charles Frederick Worth as the Father of haute Couture. Barnard (2007, p. 78) quotes Lipovetsky in Fashion theory: a reader. Lipovetsky pointed out that Worth revolutionized. . 21 .

(32) the process of creating fashion, especially in sales techniques and advertising. His major innovation was introducing the clothing models to be worn by young women, who became the prototypes of today’s mannequins or fashion models, known then as sosies, “doubles”. In this way, fashion became an enterprise involving not only creativity but also advertising spectacles. However, haute couture as we know today did not adopt the current rhythm of creation and presentation until the beginning of the 20th century: Haute couture is based in the exclusive design, (i.e. no mass production) aimed to exclusive customers with a good economic background. As Monneyron (2006, p. 30) says, until the end of the 1950s, haute. 政 治 大 As Monneyron (2006, p. 30-31) explains, although prêt-à-porter is a term invented by a 立. couture was copied by dressmakers.. ‧ 國. 學. French in 1949, the concept, renamed under “ready wear”, was actually applied to the mass fashion production in the US right after the World War II was over. Prêt-à-porter also. ‧. reproduces models of haute couture, but with obvious differences. Prêt-à-porter uses. sit. y. Nat. different fabrics and of inferior quality, clothes are not tailor-made and they generally do not. er. al. n. consumers.. io. have a single size. Its variety reflects the heterogeneity of tastes and the economic access of. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Barnard (2007, p. 362) takes Braham’s perspectives. Braham considers that haute couture has lost is significance in contemporary fashion, as the major fashion houses have erased the apparent division between elite designer fashion and high street fashion. Therefore, fashion houses have increasingly applied for licensing agreements worldwide, in order to protect their brands and image. However, in parallel, haute couture deals nowadays with a counterfeiting market of elite designers’ items with their correspondent name and logo. The limited edition of original and exclusive products with a high fashion brand can make. . 22 .

(33) customers or followers feel anxious. As we can see, haute couture and prêt-à-porter are two completely different clothing from social, economic and cultural perspectives. And nowadays the fashion on the streets and peoples’ lifestyles is replacing haute couture and influencing in the decisions makings of clothing companies. We will link in chapter 3 the connection of these two modalities of clothing with the fast fashion retailer Zara.. 2.4.1 Retailing and Global fashion. 政 治 大 are two essential factors for clothing retailers nowadays. Similarly, Nueno and Ghemawat 立. Cachon and Swinney (2011, p. 793) state that enhanced design and quick response (QR). ‧ 國. 學. (2003) use the description of QR from Hammond and Kelley: larger apparel retailers play the leading role in promoting QR. QR is a set of policies and practices targeted at improving. ‧. coordination between retailing and manufacturing in order to increase the speed and. sit. y. Nat. flexibility of responses to market shifts, which began to diffuse in apparel and textiles in the. al. er. io. second half of the 1980s.. v. n. Cachon and Swinney (2011, p. 793) add that European fast fashion retailers such as Zara,. Ch. engchi. i n U. H&M, and Benetton, employ large staffs of internal designers and even use costly local labor and expedited shipping methods when necessary. Although this is seemingly costly, it still turns profitable, because they can minimize strategic behavior. For instance, according to the 2011 Annual Report of Inditex Group (holding company who owns Zara and seven other chain stores), over 50% of Inditex’s manufacturing takes place in suppliers from proximity. Thus, fashion retailers stress on the importance of the close relationship between manufacturing and retailing.. . 23 .

(34) On the other hand, fashion retailers focus on internationalization, which creates a highly competitive environment. Current major fashion retailers promote a global fashion: Zara, H&M and Uniqlo. The three have different business models but equally successful. The emergence and development of global fashion in the 21st century has played a significant role in the fashion industry. Fashion is, actively and passively, part of the cultural globalization, and globalization is about mobility across frontiers of individuals; goods, values, customs, traditions, etc. Fashion is global in the sense that Western fashion system no longer defines what is fashionable and what is not.. 政 治 大 fashion, at affordable prices. With its current 1,925 stores in the world, the concept of global 立. As we will see in chapter 3, the maxim of Zara is to create and commercialize a global. ‧ 國. 學. fashion that Zara embraces since its beginnings proves that national borders do not impede to a shared fashion culture (Martínez, 2012, p. 99).. ‧ sit. y. Nat. 2.5 Mass fashion and fast fashion. al. er. io. According to the Glossary of Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, mass fashion consists of “widely. v. n. accepted fashions sold in mass quantities through retail stores, often at low prices”. Barnard. Ch. engchi. i n U. (2007, p. 223) cites Partington: the so-called ‘mass-market’ theory (or similarly, what we mentioned in the previous subsections, ‘trickle-across’) was developed during the post-Second World War, along with a capitalist system and industrialized society, in which the working classes needed commodities. With mass production, consumer revolution came along and led to new tastes, new preferences and a change in consumption behavior among the working classes. Fashion was then democratized. Thus, mass-market fashion or mass fashion appeared due to economic arguments. Furthermore, the seasonal component of. . 24 .

(35) fashion was re-considered: new manufacturing and merchandising strategies were introduced, so that consumers within all socio-economic groups could access to clothing simultaneously to the collections presented in fashion shows. Thus, market segments with their respective different styles were able to access equally fashionable styles and a wide range of choices. And nowadays, many of the new ideas for mass fashion come from the street, the trends, and under the pressure of constant innovation. In addition, Kawamura (2005) correlates mass fashion with labels: Before something can really become a fashion, it must be capable of being labeled. If the new style or clothing. 政 治 大 wide territory, and become identified with that particular time (p.87). Therefore, the flow of 立. becomes a mass fashion, the label will become known to many people, spread quickly over a. ‧ 國. 學. information and influence is an important factor within this system of mass fashion. As Partington (quoted by Barnard, 2007, p. 223) states, the mass fashion responded to a desire. ‧. of the large majority of consumers to innovate and to be fashionable in their styles of life.. sit. y. Nat. In recent years, the rise of fashion retailers has attracted consumers worldwide. What do. al. er. io. Zara, H&M and Uniqlo have in common? Fast fashion. According to Macmillan Dictionary. v. n. (2010), fast fashion is a term used to describe cheap and affordable clothes, which are the. Ch. engchi. i n U. result of catwalk designs moving into stores in the fastest possible way in order to respond to the latest trends. Before analyzing fast fashion, we have a look at the fashion life cycle.. . 25 .

(36) Figure 1. A normal fashion cycle model.. Source: Consumer behavior in fashion, Solomon & Rabolt (2009, p. 12).. 政 治 大. As we can see in the figure above, a normal fashion life cycle starts with the innovation. 立. and rise of a certain trend (introduction stage). Then, it gains in popularity and reaches the. ‧ 國. 學. peak of the trend (acceptance stage). And, eventually, in the regression stage, that trend. ‧. gradually declines as time goes by, until it becomes obsolete, and a new style arises. However, the length and shape of the fashion cycle depend on the different kinds of. y. Nat. io. sit. fashion. Some are longer-lived; others shorter-lived, and the stages can also vary. Apart. n. al. er. from the normal life cycle and considering the relative length of acceptance cycle, there are. Ch. i n U. v. other three kinds of life cycle curves: Fad, moderate fashion and classic. We take the. engchi. suggestion of Wang (2010, p.9) in her thesis Consumer behavior: characteristics in fast fashion, as she includes the position of Fast fashion, in order to better understand the term:. . 26 .

(37) Figure 2. Comparison among fad, fast fashion, moderate fashion and classic.. Source: Consumer behavior: characteristics in fast fashion, Wang (2010, p.9).. 政 治 大. We observe in the figure above, that fast fashion is located between moderate fashion and. 立. fad. A fad is a short-lived fashion that suddenly becomes popular and quickly disappears.. ‧ 國. 學. Fads can be accompanied by a craze or mania by consumers, and retailers may find it difficult to keep the item in stock. On the other hand, classics are those trends or styles that. ‧. seem to be acceptable or in good taste anytime, any place (Solomon & Rabolt 2009, p. 16).. Nat. sit. y. Finally, from a business perspective, Liz & Gaynor, (2006, p. 259) define fast fashion as. n. al. er. io. a strategy which aims to reduce the processes involved in the buying cycle and lead times. i n U. v. for getting new fashion product into stores, in order to satisfy consumer demand at its peak.. Ch. engchi. As we continue now with chapter 3, we will observe in depth how Inditex Group is considered the world’s largest fashion retailer, according to Reuters (March 15, 2013). We will see how Zara integrates the key points of fast fashion, mass fashion and retailing, in a well-defined global strategy, and why Zara emphasizes on the key factor of quick response in all the phases of its business model.. . 27 .

(38) Chapter 3. Zara: an Overview The first Zara store was opened in 1975, in downtown A Coruña, and after 38 years, there are 1,763 stores in the world. During the 2012 financial year (1 February 2012 to 31 January 2013), Inditex’s net sales rose by 16%, from 2011 with 13.8 billion euros, to 15.9 billion euros. Figures demonstrate that Zara is the leader in growth and sales revenues. Zara’s unconventional approach of global fast fashion makes it a significant case for study and discussion. This third chapter is entirely focused on Zara. First we review the history of Inditex. 政 治 大 business model, as well as the marketing and (zero) advertising strategy that the Group 立 Group, Zara and the man behind such a fast fashion empire. Second, we go through the. ‧ 國. 學. follows. Then, we look at what is the current position of Zara in its home market, Spain, and finally, contrast it with the expansion of the fashion retailer worldwide, with special. ‧. emphasis on Asia and recently, on Taiwan.. sit. y. Nat. For this chapter, we use several sources: the Inditex 2011 Annual Report, the press. al. er. io. releases from Inditex, the results of March 13, 2013 and the latest update of stores of April. v. n. 30, 2013. But the main source is the book Zara: Visión y estrategia de Amancio Ortega. Ch. engchi. i n U. (“Zara: vision and strategy of Amancio Ortega”), in which journalist David Martínez analyzes the principles and strategies governing Inditex in order to understand its business model, as well as to get to know the creator and co-founder. And we will look in depth the sections dedicated to the beginnings of Inditex and the key points for its business model, in order to understand the reasons behind the success of Inditex and Zara, along with the exponential growth of Zara stores worldwide.. . 28 .

(39) 3.1 Inditex, Zara and Amancio Ortega Industria de Diseño Textil, S.A. (Textile Design Industry) more commonly known as Inditex Group, is one of the largest fashion distribution groups worldwide, and its headquarters are located in Arteixo, a town near the province of A Coruña, in the region of Galicia, on the northwest of Spain. Inditex is a holding company made up of more than 100 companies operating in textile design, manufacturing and distribution. The Group is present in eight retail formats: Zara, Pull & Bear, Massimo Dutti, Bershka, Stradivarius, Oysho, Zara Home and Uterqüe. Inditex has a total of 6,058 stores in 86 markets across five. 政 治 大 ten years after the opening of the first Zara store, on a street in downtown A Coruña. Zara is 立. continents, according to the latest update on April 30, 2013. Inditex was founded in 1985,. ‧ 國. 學. Inditex’s flagship chain store: it is the largest and most internationalized of all the store formats, and competes directly and internally with the other seven brands. During the 2012. ‧. financial year, Inditex’s net sales rose to 15.9 billion euros. And Zara alone contributed a. y. sit. Nat. 64.8% to the total sales, with net sales of 8,938 million euros.. n. al. er. io. Figure 3. Sales contribution by the eight chains within Inditex (See also Appendix 1).. Stradivarius 6% . Ch. OYSHO 2% . i n U. ZARA HOME 2% UTERQÜE 1% . engchi. v. Sales . PULL&BEAR 7% Massimo Du> 7% ZARA 65% . Bershka 10% . Source: Inditex 2011 Annual Report. . 29 .

(40) There is no doubt that Zara is the leader in growth and sales revenues. With 9.5%, Bershka is the second chain store and it appeals to the youngest target market, by bringing trends from street fashion, music and art. Massimo Dutti ranks the third position (7.3%) and appeals to independent, urban and cosmopolitan men and women. The fourth one is Pull&Bear, which contributes 6.9% and is specialized in casual, laid-back fashion within a global youth culture. Stradivarius is in the fifth position, with 6.3%, and is aimed to young people who crave an informal, funky look. A contribution of 2.3%, Oysho offers women’s lingerie and intimate apparel. Also with 2.3%, Zara Home specializes in home decor and. 政 治 大 in 2008 and offers a more elegant and sophisticated fashion. We can observe that each of the 立. linens. In the last position with a contribution of 0.5%, we find Uterqüe, which was launched. ‧ 國. 學. eight retail formats have their own distinctive characteristics, and their clear fashion objectives allows shoppers to distinguish them.. ‧. Below we compare Zara’s figures with the rest of the chain stores within the Inditex. sit. y. Nat. group, by aggregating them into one group called “Non Zara”. We also notice that all figures. al. er. io. have slightly decreased from 2011 to 2012.. v. n. Figure 4. Comparison of sales percentages between Zara and the other seven brands, during. Ch. engchi. i n U. the financial years 2011 and 2012 (See also Appendix 2).. . Concept. FY 2012. FY 2011. Zara. 66.1%. 64.8%. Non Zara. 33.9%. 35.2%. Pull&Bear. 6.8%. 6.9%. Massimo Dutti. 7.1%. 7.3%. Bershka. 9.3%. 9.5%. 30 .

(41) Stradivarius. 6.0%. 6.3%. Oysho. 2.0%. 2.3%. Zara Home. 2.2%. 2.3%. Uterqüe. 0.5%. 0.5%. Source: Inditex Financial Year 2012 Results Presentation Amancio Ortega Gaona, best known as Amancio Ortega, is the man behind Zara’s fast fashion empire. Although he stepped down from the helm of Inditex in July 2011 and. 政 治 大 company, Ortega continues立 as the majority shareholder of the company, from which he. handed over the presidency to Pablo Isla, CEO and former Deputy Chairman of the. ‧ 國. 學. owns nearly 60%. In early March 2013, magazine Forbes listed Ortega as the third richest man in the world, with a net worth of $57 billion.. ‧. Ortega was born on March 28, 1936 in León, northwest of Spain. In 1944, the whole. sit. y. Nat. family moved to A Coruña because of his father’s job as a railway worker. When he turned. n. al. er. io. 11, he decided to give up school. At the age of 14, he went to work as a delivery boy to help. v. feed his family, in a small shirt maker's shop called “Gala”. There, he focused on the. Ch. engchi. i n U. importance of offering products directly to the customer, without intermediaries and generating almost no stocks. Today, this principle is reflected in Zara’s business model: simplification to the maximum in the number of intermediaries between the design phase until the moment the fashion item gets to the customer. Thus, all decisions (from design to distribution) are made in the Inditex headquarters in Arteixo. Indeed, the most important factor for Inditex is ‘time’ (Martínez, 2012, p. 131), which can be well illustrated by the rapid turnover of collections. We also remark that the total amount of garments that Inditex. . 31 .

(42) creates is impressive: a total of 900 million every year and, within a team of over 300 designers, 200 are only dedicated to Zara (Martínez, 2012, p. 71, 127). Years later, he moved to a bigger clothing shop called “La Maja”. Customers came from both wealthy families and the emergent middle-class, which started to have an interest in ways of dressing, after years of hard work and during the post-civil war era in Spain. In La Maja, Ortega made contact with fabric manufacturers from Catalonia (northeastern region of Spain), who allowed him access to wholesale prices. He then understood how important it is to integrate and control fabric supply and manufacturing within the business strategy. He. 政 治 大 firmly the idea that it is the customers who dictate the designer what they want to wear, and 立 also learned to focus on the customers’ tastes and preferences. Therefore, Zara has kept. ‧ 國. 學. not the way around. As Martínez (2012, p. 61) points out, for Ortega, the designer is rather an editor of what is being sold in the world, than a creator.. ‧. On the other hand, La Maja had several stores spread strategically all over the city of A. sit. y. Nat. Coruña, which made Ortega apply this strategic location for his future business: Zara stores. al. er. io. are located in heavily trafficked areas, such as wide streets or shopping zones, to attract as. v. n. many customers as possible. Zara especially establishes its stores in landmark locations such. Ch. engchi. i n U. as the Corso Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan and considered the oldest shopping mall in Italy, a Baroque-style 18th-century convent in Salamanca in Spain or the Taipei 101 building in Taiwan. To approve the opening of an Inditex store, the Group analyzes the following five factors (Martínez, 2012, p. 100): the typology of the customers, the capacity of acquisition, the presence of other textile companies, the channels of sales and the evolution of demand. Ortega left La Maja and, along with his wife, Ortega’s brother and wife, founded the company Confecciones GOA (“Dressmaking GOA” – GOA was the acronym upside down. . 32 .

(43) of Amancio Ortega Gaona). According to Martínez (2012) Ortega started to adapt the production costs to the estimated quantity of clothes to sell, as they ‘know’ the customers’ needs and/or desires (p. 47). They made and sold fine comfortable bathrobes, aimed to both the working woman and the woman who wanted to dress well at home. Therefore, these bathrobes could cover all social segments. Ortega started to focus on the textile needs of the Spanish women, in those days when fashion used to come from Paris and Milan. This is the beginning of the process of Zara. Thus, Ortega was determined to commercialize simple, beautiful and comfortable clothing at affordable prices, lower than those from his. 政 治 大 Ortega wanted to run his own business, so he left GOA. The first Zara store was opened 立. competitors and with a similar or superior quality.. ‧ 國. 學. in 1975, in downtown A Coruña. During the following years, Zara extended its network of stores to major Spanish cities. In 1988 Zara opened its first store abroad, in Oporto, Portugal.. ‧. The next locations were in New York (1989) and Paris (1990).. sit. al. er. io. key points of the Zara:. y. Nat. After we have reviewed the background of Inditex and Zara, we summarize now the main. v. n. 1. Production of medium-quality fashion clothing at an affordable price;. Ch. engchi. i n U. 2. Simplification of intermediaries in the business model; 3. The rapid turnover of collections; 4. Heavy investment of stores in landmark locations.. As we can see, the maxim of Zara is to create and commercialize a global fashion, at affordable prices. In addition, Zara applies the concept of fast fashion: they absorb the trends from the streets and bring them to the stores in the shortest time possible. In the following section we will look in depth the successful business model of Zara.. . 33 .

數據

相關文件

(c) Draw the graph of as a function of and draw the secant lines whose slopes are the average velocities in part (a) and the tangent line whose slope is the instantaneous velocity

6 《中論·觀因緣品》,《佛藏要籍選刊》第 9 冊,上海古籍出版社 1994 年版,第 1

The underlying idea was to use the power of sampling, in a fashion similar to the way it is used in empirical samples from large universes of data, in order to approximate the

Reading Task 6: Genre Structure and Language Features. • Now let’s look at how language features (e.g. sentence patterns) are connected to the structure

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it