國立交通大學

管理科學系碩士班

碩士論文

衝動購買後:

購買後理由對消費者滿意度之影響

After Impulse Buying: The Effects of Post-Purchase

Justification on Consumer Satisfaction

研究生: 高奐宇

指導教授: 張家齊 博士

After Impulse Buying: The Effects of Post-Purchase Justification on

Consumer Satisfaction

研究生:高奐宇 Student: Huan-Yu Kao

指導教授:張家齊 博士 Advisor: Dr. Chia-Chi Chang

國立交通大學

管理科學系

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Department of Management Science

College of Management

National Chiao Tung University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master

in

Management Science

June 2007

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

研究生:高奐宇 指導教授:張家齊 博士

國立交通大學管理科學系碩士班

中文摘要

這篇論文主要是在研究消費者衝動購買後的滿意度。購買後理由是探討此議題的重 要因子,除此之外,本篇作者還探討了其他相關變數,包括購買前心情以及消費者的後悔 傾向。這篇文章以認知失調的觀點來研究該議題,並且著重在網路環境的討論。本文以操 弄心情的圖片並設計一個衝動購買情境來操作實驗,結果發現,足夠的購買後理由能夠有 效地影響消費者衝動購買後的滿意度。然而,消費者的購買前心情與滿意度沒有存在顯著 關係,也沒有成功調節購買後理由與滿意度之間的關係。消費者的後悔傾向能夠有效調節 購買後理由與滿意度之間的關係,購買後理由的多寡會因為不同後悔傾向的消費者,而產 生不一樣的影響。 關鍵字:衝動購買、滿意度、購買後理由、購買前心情、後悔傾向Consumer Satisfaction

Student:Huan-Yu Kao Advisor:Dr. Chia-Chi Chang

Department of Management Science

National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

This study investigates the consumer satisfaction after impulse buying. Reason provided is the main factor used to investigate the relationship. We also study related factors which may influence the association: mood prior to purchase and tendency to regret. The paper observes this issue in a cognitive dissonance perspective and focuses the observation on the internet

environment. We use mood-manipulated pictures and impulse-stimulated scenario to conduct the experiment. The results showed that sufficient numbers of reason provided was an important role which influenced consumer satisfaction after impulse buying. There was no significant

relationship between mood prior to purchase and satisfaction. Mood prior to purchase did not moderate the interrelationship between reason provided and satisfaction. However, tendency to regret moderate the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction. The numbers of reason provided have different meanings for people with a high tendency to regret and with a low

tendency to regret.

Key Words: Impulse Buying, Satisfaction, Reason Provided, Mood Prior to Purchase, Tendency to Regret

這份論文之所以能夠順利的完成,必須感謝許多人,首先,感謝我的指導老師,張家 齊博士,對於我的論文細心、耐心的指導,給予我許多研究方面的建言,讓我在研究的路 途上不至於迷失方向。感謝我的父母給我經濟以及精神上的支持,讓我能無後顧之憂的完 成我的學業並取得碩士學位。 除了老師以及家人,還有許多管科 94 級的同學們的陪伴,才能讓我順利的走過碩士 生涯的這兩年。感謝我的男友,為新,給予我精神的支持,在我的研究遭遇一些問題時給 我最溫暖,最窩心的鼓勵。感謝張門的其他同學,慧芸、佩瑜、以江、秋君以及 109 研究 室的夥伴們,一路相隨,互相打氣,才能使我不斷向前,完成我的學業,我的碩士論文。 感謝交大管科提供我一個好的學習環境,以及許多優秀同學的良性競爭、相互學習,才能 成就如今的我。 最後,必須感謝每個協助我完成碩士論文的人,由於有許多好心的人願意幫我填寫問 卷,許多 PTT 實業坊的板主願意讓我放置問卷,許多給予研究建議的朋友,我才能順利的 完成研究,很多人雖然都不知道你們的姓名,但這份感謝的心意將一直留在我的心裡。 再次感謝所有陪伴我,支持我,給予幫助的所有人! 高奐宇 謹誌於 民國 96 年於交大管科

CONTENT

中文摘要 ...I

ABSTRACT ... II

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ...III

CONTENT ... IV

LIST OF TABLES ... VI

LIST OF FIGURES ... VII

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Research Motivation ... 2

1.3 Research Objectives ... 2

1.4 Literature Structure ... 3

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 5

2.1. The Nature of Impulse Buying ... 5

2.2. Reason Provided ... 7

2.3. Consumer Satisfaction ... 8

2.4. Mood Prior to Purchase ... 9

2.5. Tendency to Regret... 10

2.6. Hypothesis ... 11

2.7. Research Structure ... 15

CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY... 16

3.1 Overview... 16

3.4 Data Collection and Analysis Method ... 22

CHAPTER 4 RESEARCH ANALYSIS AND RESULTS... 23

4.1 Manipulation Check ... 23

4.2 Background of Respondents ... 24

4.4 Hypotheses Test ... 27

4.5 Results of the Tested Hypotheses ... 35

CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 36

5.1 Discussion of Results ... 36 5.2 Implications... 39 5.3 Limitations ... 40 5.4 Future Research... 41

REFERENCES ... 43

APPENDICES 1 QUESTIONNAIRE ... 47

APPENDICES 2 MOOD MANIPULATION ... 53

APPENDICES 3 REASON PROVIDED ... 55

APPENDICES 4 TEST FOR NORMALITY ... 56

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 3- 1 REASON PROVIDED TABLE...18

TABLE 4- 1 RELIABLE STATISTICS OF MANIPULATION CHECK...24

TABLE 4- 2 FREQUENCY TABLE ... 24

TABLE 4- 3 RELIABILITY ANALYSIS ... 25

TABLE 4- 4 FACTOR ANALYSIS ... 26

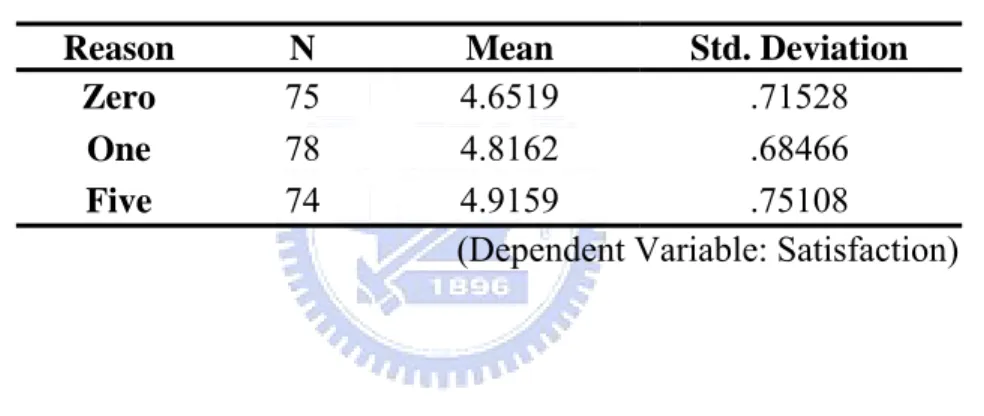

TABLE 4- 5 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF REASON PROVIDED...28

TABLE 4- 6 TESTS OF MOOD, TENDENCY TO REGRET AND REASON PROVIDED ... 28

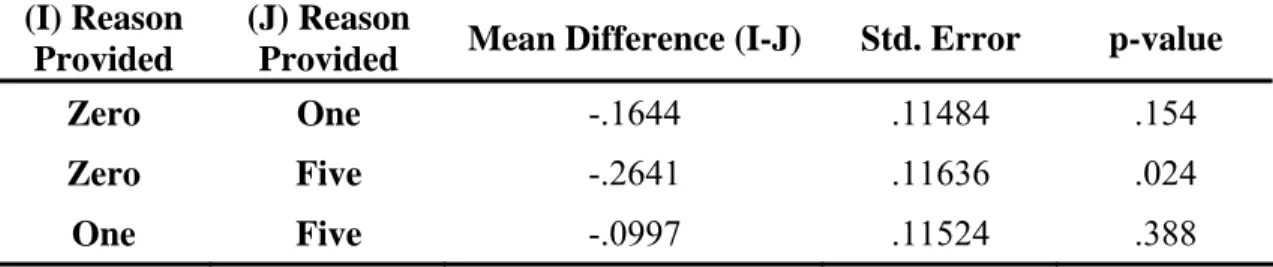

TABLE 4- 7 MULTIPLE COMPARISONS (LSD) ... 29

TABLE 4- 8 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF MOOD... 29

TABLE 4- 9 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF MOOD AND REASON PROVIDED ... 30

TABLE 4- 10 CONTRAST TESTS...32

TABLE 4- 11 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF TENDENCY TO REGRET AND REASON PROVIDED ... 33

TABLE 4- 12 MULTIPLE COMPARISONS OF TENDENCY TO REGRET AND REASON PROVIDED ... 33

TABLE 4- 13 SUMMARY OF CONTRAST ANALYSIS ... 33

LIST OF FIGURES

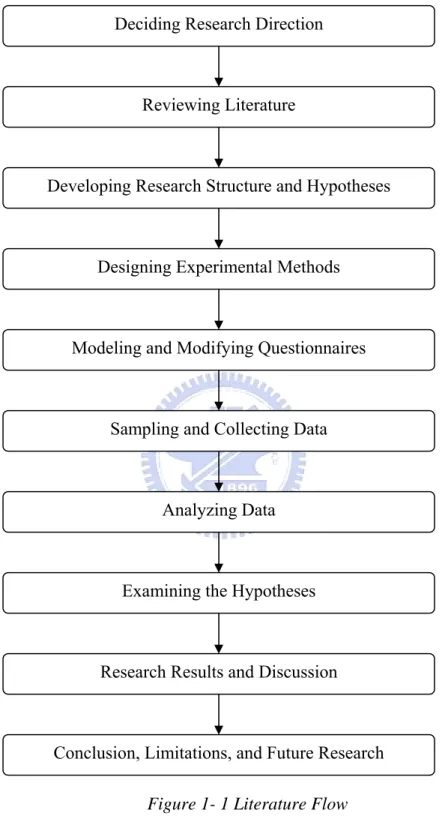

FIGURE 1- 1 LITERATURE FLOW... 4 FIGURE 2- 1 RESEARCH STRUCTURE ... 15 FIGURE 4- 1 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MOOD PRIOR TO PURCHASE AND

REASON PROVIDED ... 31 FIGURE 4- 2 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MOOD PRIOR TO PURCHASE AND

REASON PROVIDED ... 31 FIGURE 4- 3 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TENDENCY TO REGRET AND REASON

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BackgroundImpulse buying is a special and prevailing field of consumers' daily behaviors and a focal point for considerable marketing activity (Beatty & Ferrell, 1998). In the late 1970s impulse purchases accounted for between 27 and 62 percent of purchases in department stores (Bellenger & Robertson, 1978). More recently, a Chinese website survey of consumer research stated that more than 64% of consumers have once or even more made unplanned purchases in retail stores. There were 62.4% of impulse buying behaviors in the supermarkets and 75% of consumers’ buying decisions were made within 15 seconds (Wang, 2005). As economics develops, more and more purchasing activities are stimulated by marketing innovations, such as Internet shopping, home shopping networks, telecommunications, credit/cash cards and varieties of marketing strategies (Rook, 1987). Such innovations increase the probability of impulse buying. Impulse buying is an important topic in the modern marketplace.

With the improvement of electronic commerce, bricks-and-mortar stores are no longer the only channel to spur consumers’ buying impulse (Hodge, 2004, p. 2). In some marketing research in 2004, about 70% of shoppers questioned had purchased online in the previous three months and 18.8% of them were frequent online shoppers (InsightXplorer, 2004). Online shopping has even more attractive features than traditional stores to stimulate people to buy. There are many mechanisms that help consumers buy easily, such as accessibility and convenience(Wolfinbarger & Gilly, 2001), time and money save (LaRose & Eastin, 2002). People can also find many kinds of merchandizes on the internet, such as popular, new products or unique items (Donthu & Garcia, 1999; Wolfinbarger & Gilly, 2001). And buyers will be interested in and attracted by vivid text, pictures, video, advertisement and marketing activities presented on the webpage, enjoying the

appealing, pleasant and exciting experiences through online shopping (Adelaar, Chang,

Lancendorfer, Byoungkwan Lee, & Morimoto, 2003; Donthu & Garcia, 1999; Teo, 2002). Thus, consumers shopping online have a greater probability of buying impulsively due to the

convenience of online stores. This research focuses on impulse buying behavior in the online shopping environment because there was only a little literature about this issue in the past (Hodge, 2004; Parboteeah, 2006; Rhee, 2006).

1.2 Research Motivation

For decades, researchers have studied impulse buying in bricks-and-mortar stores and investigated the antecedences of impulse buying, such as display, promotion, products, time pressure, impulse buying tendency and so on (Beatty & Ferrell, 1998; Bellenger & Robertson, 1978; Goodey, May 1990; Hodge, 2004; Iyer, Spring 1989; Jones, Reynolds, Weun, & Beatty, 2003). Few studies of impulse buying focus on the internet environment(Hodge, 2004;

Parboteeah, 2006; Rhee, 2006) and on the consequences of impulse buying behavior. The motivation of the research is to discuss the satisfaction after impulse buying, find the issues related to how consumers adjust their satisfaction after impulse buying if they are provided purchasing reasons, and to expand the specific factors to how mood prior to purchase and tendency to regret influence people’s post-purchase satisfaction.

1.3 Research Objectives

In view of the reasons above, the research is to find:

1. After impulse buying, whether consumers change their satisfaction as they are provided some purchasing reasons or persuaded by other people.

2. Whether consumers’ mood prior to purchase would moderate the relationship between reason provided and their satisfaction.

3. Whether consumer’s tendency to regret would moderate the relationship between reason provided and consumer satisfaction.

1.4 Literature Structure

This research includes five chapters, and the outline of each chapter is as follows:

Chapter One introduces the research background, research motivation, research objectives, and the research structure.

Chapter Two reviews the antecedent literatures relevant to this research. It contains impulse buying behaviors, reason provided after purchase, satisfaction, mood prior to purchase, and tendency to regret.

Chapter Three illustrates how the experiment was designed and the data was collected. It presents an experimental procedure, scenario design, sample selection, data collection,

measurements, data analysis method, manipulation check, and pre-test.

Chapter Four examines the hypotheses and shows the statistical results of this research. It includes reliability and validity analysis, sample-independent T test and ANOVA Test. With this information, differences could be compared and factors behind impulse buying discussed.

Chapter Five summarizes the findings, describes the limitation of this research and provides suggestions for future research.

Figure 1- 1 Literature Flow

Deciding Research Direction

Sampling and Collecting Data

Analyzing Data

Examining the Hypotheses

Research Results and Discussion

Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Research Reviewing Literature

Developing Research Structure and Hypotheses

Designing Experimental Methods

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. The Nature of Impulse BuyingResearch of impulse buying behavior has a long history since Stern (1962) had defined impulse buying as “any purchase which a shopper makes but has not planned in advance” (p. 370). Impulse buying occurs while shopping in a store, someone who has no pre-shopping plans makes an unintended, unreflective, and immediate purchase(Rook & Fisher, 1995). It is made without engaging in a great deal of evaluation. Individuals buying on impulse are less likely to consider the consequences or to think carefully before making the purchase(Rook, 1987). One comprehensive definition described an impulse as “a strong, sometimes irresistible urge; a sudden inclination to act without deliberation”(Golderson, 1984, p. 37; Rook, 1987, p. 189). And Rook (1987) defined impulse buying as when "a consumer experiences a sudden, often powerful and persistent urge to buy something immediately” (p.190). Consumers buying impulsively will not postpone the desire in order to gather more information; they are prone to act with

diminishing regard for the consequences and have the urge to meet their immediate needs (Jones et al., 2003; Rook, 1987).

Following the literature review above, Beatty and Ferrell (1998) extended Rook’s definition of impulse buying to “impulse buying is a sudden and immediate purchase with no pre-shopping intentions either to buy the specific product category or to fulfill a specific buying task. The behavior occurs after experiencing an urge to buy and it tends to be spontaneous and without a lot of reflection (i.e., it is "impulsive"). It does not include the purchase of a simple reminder item, which is an item that is simply out-of-stock at home(Beatty & Ferrell, 1998). Because this paper focuses on the online shopping experience, and most people do not get daily supplies such as toilet paper or eggs on the internet in order to make the study applicable to an online environment,

this research has decided to use the definition of Beatty and Ferrell (1998) to improve the rationality of the research.

Previous research has identified four classifications of impulse buying: pure, reminder, suggestion and planned (Hodge, 2004; Miller, 2002; Stern, 1962). Pure impulse buying is driven by emotional appeal. It satisfies the buyer’s immediate urge which is stimulated by emotional appeal; reminder impulse buying occurs when consumers see certain products which remind them to make the purchases. For example, when buyers see the products in front of them, they are reminded that the things used at home are out of stock such as the supplies for daily use. In reminder impulse buying, consumers buy the items on a regular basis and have prior product knowledge about the features of the products; suggestion impulse buying means when an individual sees a certain product for the first time and conceives it useful for application. This kind of buying is stemmed from the functions of the item, not out of emotional appeal just like pure impulse buying; planned impulse buying occurs when consumers buy products based on price and product specials. For example, when someone enters a supermarket and finds tissue paper on sale. Although there is no immediate need to buy tissue paper, the consumer knows that the regular item will be used in the future. So the knockdown tissue paper is bought based on the sale price.(Hodge, 2004; Miller, 2002)

Impulse buying behavior makes buyers have the urge to own something immediately. However, the cognitions associated with impulse behavior are more likely to possess negative reactions(Rook & Fisher, 1995; Shiv & Fedorikhin, 1999). The formidable urge leads to the decrease of intelligence on buying decision(Weinberg & Gottwald, 1982) and up to 80% of consumers face some negative outcomes, including financial risk, unnecessary spending, guilt, non-support and so on(Rook, 1987). The main cause is because that these purchasers do not

undergo considerable assessment. Unwise decisions causes buyers to give up other better, rational alternatives and then feel regret(Lin, Jhuang, Gong, & Lai, 2005).

2.2. Reason Provided

Consumers may produce dissonance after the decision is made (Sweeney, Hausknecht, & Soutar, 2000 ). According to Festinger (1957), dissonance could be described as a person being in a conflictive state if two elements about their cognition, behavior, or feeling, are

inconsistent(Festinger, 1957; Hunt, 1970). Cognitive dissonance is a kind of psychological discomfort; for some people, this kind of discomfort is an extremely painful feeling which will motivate them to reduce it to keep consonant within their recognition (Carlsmith & Aronson, 1963; Elliot & Devine, 1994; Festinger, 1957; Sweeney et al., 2000 ). Manifestations to reduce dissonance include behavior changes, attitude changes, and searches for new information and supportive opinions or other communications (Festinger, 1957; Hunt, 1970; Kotler, 1967).

In previous literature, impulsive buyers always purchase quickly and don’t like to postpone their decision to gather more information. Thus, they are usually not able to make the best decision or choose the ideal alternative. Their impetuous behavior mires themselves in

difficulties such as regret, financial risk, moral condemnation (Jones et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2005; Rook, 1987; Shiv & Fedorikhin, 1999). This study proposes that impulsive consumers experience cognition dissonance more easily than rational consumers because their unwise, irrational,

impetuous decisions are inconsistent with their initial cognition, and this discrepancy motivates people to seek new opinions to reduce dissonance. Dissonant consumers need more reassurance to be sure that a sensible purchase decision has been made (Montgomery & Barnes, 1993). They will be looking for supportive evidence such as advertisements, sale’s reassurance or other

communications to reduce the pressure of dissonance. Thus, the thesis argues that, dissonant, impulsive consumers will engage in seeking supportive buying reasons, or positive

reinterpretation (Yi & Baumgartner, 2004), to persuade themselves that the impetuous purchases are not as poor as people think. Reason provided is defined as impulse buyers are provided with buying reasons. The study speculated that, providing with buying reasons to the buyers will be a powerful and persuasive way to correspond behaviors with cognition. As they are provided with buying reasons, they can reduce dissonance more easily.

According to literatures, buyers will gain information from alternative sources and use persuasion knowledge to deal with message from different sources (Campbell & Kirmani, 2000). In order to make the research more specific and reduce variations, the author has decided to focus the source of reason only from neutral sources, who are people who will not benefit from the sale (e.g. a salesperson would), such as friends, relatives, key pals or anyone who shares the same opinions in a forum.

2.3. Consumer Satisfaction

Consumer satisfaction has been discussed for several decades since Cardozo (1965) first brought it up and has various definitions in previous literature. It could be characterized as an evaluative judgment after purchasing with an evaluation between expectation and product or service performance (Oliver, 1980; Westbrook & Oliver, 1991). Expectancy-disconfirmation theory is one of the most influential topics of consumer satisfaction (Oliver, 1980; Zwick, Pieters, & Baumgartner, 1995), and among which consumer satisfaction can be specified as a function of initial standard judgment which compared to the level of perceived performance (Westbrook & Oliver, 1991; Zwick et al., 1995). Consumers are assumed to assess a product and yield

expectation before actual purchasing it. If performance exceeds expectation, a positive disconfirmation will be expected and people will feel satisfied about the product, in contrast, people will be dissatisfied if there is a negative disconfirmation as performance can not reach people’s expectation (Zwick et al., 1995).

In this study, cognitive dissonance theory suggests that individuals will adopt a dissonance reduction strategy if they experience disconfirmation consumption (Tse & Wilton, 1988). People may distort their cognition of how the product performs and assimilate their judgments into initial expectation if they don’t want to admit the difference between expectation and actual cognition (Anderson, 1973). When consumers experience dissonance after consumption, they will

assimilate the cognition judgments in line with expectation. This statement will be applied in further research.

2.4. Mood Prior to Purchase

Gardner (1985) defined mood as “a phenomenological property of an individual’s

subjectively perceived affective state” (p. 281). Mood in this paper refers to the feeling before making an impulse buying decision, mood prior to purchase. It is viewed as a temperate, transient, and pervasive feeling state (Gardner, 1985) that affects consumers’ responses such as what they buy, when they shop and whom they shop with, retail preference and choice(Machleit & Mantel, 2001), measure of store image, number of products bought(Sherman & Smith, 1987 ), spending levels above what consumers had planned, willingness toreturn, and shopping

satisfaction(Dawson, Bloch, & Ridgway, 1990) and shopping satisfaction(Machleit & Eroglu, 2000). Mood has a significant effect on shopping behavior and consumers may bias their selection, preference, retrieval cues of memory or judgment in varying with their mood states.

Someone in a good mood may process more positive information and be more willing than someone in a bad mood to associate their positive mood with related social arguments (Swinyard, 1993). When people are in a positive mood, they usually tend to avoid cognitive elaboration (Swinyard, 1993) and perceive a higher likelihood of positive events occurring than those in a negative mood (Fedorikhin & Cole, 2004). Besides, impulse buying behaviors have greater emotional reactions than non-buyers, such as amusement, delight, enthusiasm, and joy (Dawson et al., 1990; Weinberg & Gottwald, 1982).

Gardner (1985) has suggested that consumers’ mood states are positively related to product satisfaction because people tend to seek consistency between their moods and evaluations (Dawson et al., 1990; Gardner, 1985). People in a good mood will not be willing to accept bad events or outcomes because they do not want to destroy their initial good mood (Fedorikhin & Cole, 2004). Thus, consumers experiencing a positive mood state are more likely to report that products or stores consist with expectations (Dawson et al., 1990; Mackie & Worth, 1989).

2.5. Tendency to Regret

Regret is the most frequently mentioned negative emotion in everyday conversation (Inman & Zeelenberg, 2002). It arises from “comparing an obtained outcome with a better outcome that might have occurred had a different choice been made” (MarcelZeelenberg, Dijk,

AntonyS.R.Manstead, & Pligt, 1998). If consumers make a decision and then find it not as good as they thought, or if they find better opportunities after making a decision, they may feel regret (Schwartz, 2004). Regret has been defined as “the painful sensation of recognizing” that “what is” compares unfavorably with “what might have been” (Sugden 1985, p. 77)”.

Everyone has a different tendency of ease to feel regret (Schwartz, 2004). According to Schwartz (2004), a person who easily feels regret is unhappy, not satisfied with their life and is pessimistic. The study speculates that a person with a higher tendency to regret may need more reasons after impulse purchase to reduce that feeling of regret.

2.6. Hypothesis

2.6.1. Reason Provided and Satisfaction

According to the literature mentioned above, impulsive buyers who experience negative emotions after purchasing will turn to their friends or acquaintances for advice or approval (Yi & Baumgartner, 2004). They are prone to seek positive reinterpretation to reduce their regret or dissonance (Yi & Baumgartner, 2004). And consumers who received post-purchase reassurances or support would have lower dissonance and a more favorable attitude toward the products and the store they had shopped in. As a result, the article could infer that, when impulsive buyers are provided with more reasons for impulse buying, it is easier for them to reduce dissonance than those are not provided with buying reasons, and a higher satisfaction after dissonance has been reduced. Based on the above, it is hypothesized that:

H1: Impulsive consumers who are provided with more buying reason are more satisfied than those who are provided with fewer buying reasons.

1a: One reason is better than no reason. 1b: Five reasons are better than one reason.

2.6.2. Mood with Reason Provided and Satisfaction

Mood with Satisfaction

Moods are feeling states that are transient and specific to certain time or situation(Gardner, 1985; Robert & Sauber, 1983), which would influence specifiable consumer behaviors(Clark & Alice, 1982; Robert & Sauber, 1983) Positive mood seems to enhance the likelihood of expected performance and , by contrast to negative mood, make people kinder to oneself and to others(Gardner, 1985; Underwood, Moore, & Rosenhan, 1973).

Consumers will be distracted by positive mood states in the processing of information; therefore, they will not be so critical on the judgment of products and report a higher perceived performance to consist with their good moods (Dawson et al., 1990). As previously discussed, people in a good mood may be motivated to maintain their state of well-being (Isen & Levin, 1972 ; Swinyard, 1993) and then affect their product satisfaction (Gardner, 1985). Also they will have a preferable attitude toward the store which they had selected for shopping (Swinyard, 1993). Therefore the article assumes:

H2: Consumers in a good mood will have higher satisfaction than those in a bad mood.

Mood with Reason Provided and Satisfaction

Jonas, Graupmann and Frey (2006) believed that, cognitive dissonance is an uncomfortable state of affect, similar to a negative mood, which will motivate people to change their current state of mind into a more positive one. From a mood-theoretical point of view, dissonance reduction behavior would be referred to as mood repair or mood regulation (Jonas, Graupmann, & Frey, 2006), The mood-repair approach(Isen, 1987; Jonas et al., 2006) suggests that people try

to maintain positive mood states and therefore focus on positive memories. They also try to avoid negative mood states by neglecting the memory of negative events (Isen, 1987; Jonas et al., 2006). Thus, we can infer that a negative mood to dissonance arousal would lead to positive attitude change, such as dissonance reduction to recover good mood state, whereas positive mood decreased attitude change (Jonas et al., 2006). The dissonance can be reduced by searching for information that supports the decision and avoiding conflictive information. And supportive information to reduce dissonance is more pleasing for people in a negative mood compared to those in a positive mood (Jonas et al., 2006). Thus, supportive buying reasons to the impulsive buyers in a good mood are supposed not to be so effective on reducing dissonance as those in a bad mood.

Integrating the conceptions described above, the article supposes that mood may play as a moderator between reason provided and satisfaction. As mood states intervene between the relationships, reason provided would have different effect on satisfaction. As stated in previous literature, people tend to maintain a neutral mood to ensure coping with demanding situations (Jonas et al., 2006). If people have been in a negative mood before purchasing, adding to a more regrettable or guilty feeling after impulse buying, would necessitate a higher urge to adjust their mood to a neutral state, in case they became more depressed; however, if people are in a positive mood, they don’t have such an urgent demand to recover their affect as those in a negative mood; thus, it may not have such a significant change on satisfaction after they are comforted by buying reasons. The study supposes that there might be some rise in satisfaction when provided reasons are increased, but not as conspicuous as for those in a negative mood. On the other hand, when impulsive buyers experience a negative mood, providing reasons may be more persuasive to help them reduce their guilty feeling or dissonance. They would increase their satisfaction

significantly as more and more reasons are provided. The previously mentioned reasoning leads to the hypothesis:

H3: Impulsive buyers in a negative mood before making a buying decision have more significant increasing post-purchase satisfaction when buying reasons are provided than those in a positive mood.

3a: One reason is better than no reason. 3b: Five reasons are better than one reason.

2.6.3. Tendency to Regret with Reason Provided and Satisfaction.

Ritov and Baron (1992) suggest that the underlying reasons for the decision making might play an important role in post-decision regret(Ritov & Baron, 1992). Consumers may incorporate the presence of a reason into their assessment and hence indicate less regret; in other words, decisions which are not backed up by good reasons are especially likely to produce regret (Inman & Zeelenberg, 2002). Consumers with a high tendency to regret will blame themselves more (Schwartz, 2004). Therefore we can argue that providing reasons behavior would help consumers reduce regret. They may desire reasons more strongly than those with a low tendency to regret. This is to reduce bad feeling. After being provided more reasons to purchase, the high tendency to regret consumers will feel much more relaxed and then have higher satisfaction. These notions described above will lead to the hypotheses:

H4: Impulsive buyers with a higher tendency to regret have more significant increasing satisfaction when buying reasons are provided than those with a lower tendency to regret.

4a: One reason is better than no reason. 4b: Five reasons are better than one reason.

2.7. Research Structure

* Under circumstance after impulse buying

Figure 2- 1 Research Structure Reason Provided after Purchase Tendency to Regret Mood Prior to Purchase Satisfaction H1 H2 H3 H4

CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 OverviewThis study intended to find out in an online shopping environment how reason provided influences impulsive buyers’ satisfaction and how the relationship is moderated by moods prior to purchase and the tendency to regret.

To test H1, H2, and H3, in this 2 (prior mood: positive or negative) ×3 (reason provided, none (N=0), fewer (N=1) and more (N=5)) between -subject experiment, the author assessed mood effects on consumer reactions to some mood-inducing pictures under three reason provided conditions; Then, the author assessed respondents’ tendency to regret to investigate whether tendency to regret would moderate the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction. A 3 (reason provided, none (N=0), fewer (N=1) and more (N=5)) × 2 (mood prior to purchase

(positive & negative)) × 2 (tendency to regret (high & low)) between-subject experiment was applied to test if H4 was supported.

3.2 Experiment Design

3.2.1 Experiment Procedure

Initially, the research focused on those respondents who have online shopping experience. Respondents learned that they would participate in one study about mood states of shopping decisions. To induce respondents to form initial mood states before purchasing, respondents were randomly assigned to two mood-inducing conditions, to complete the mood scales. Then, an online shopping scenario was designed to stimulate them into impulse buying behaviors, and the impulse buying scale was used to check whether they were spurred on to buy impulsively. Last the respondents were randomly assigned into three scenarios about numbers of reason provided,

namely none (N=0), less (N=1), more (N=5), and their satisfaction was analyzed. In addition, a regret scale, which was cited by Schwartz (2004), was used to examine the influence of tendency to regret on the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction. Post-purchase satisfaction was analyzed in particular for the effect of the variable. After the experiment, participants were thanked for their help.

3.2.2 Stimulus Development

Manipulation of mood prior to purchase

To manipulate moods, the study selected some pictures for each mood state. There were four interesting and humorous comedies for positive mood manipulation, and four pictures about butchering seals selected for negative mood manipulation (APPENDIX 2). For the purpose of a manipulation check, participants were asked to report their mood using the mood scale adapted from Swinyard (1993) (sad/happy, bad mood/good mood, irritable/pleased, depressed/cheerful).

Manipulation of Impulse Buying

To stimulate respondents into impulse buying behaviors, an online shopping scenario was designed to achieve the purpose. First, the study referred to the product categories from the most popular shopping website (InsightXplorer, 2005), Yahoo! Shopping Mall, to form a virtual shopping environment (APPENDIX 1), and let respondents plan their own shopping lists according to their disposable incomes. Second, in light of Beatty and Ferrell’s (1998) definition of impulse buying (not including reminder items), an appealing purchase alternative was selected, KINGMAX flash drive. This was on sale, to attract respondents to buy the product after they had made their shopping lists (APPENDIX 1). Once respondents chose the impulse-inducing item as

their purchase decisions, they were identified as impulsive buyers. The sample without constructing impulse buying behaviors was eliminated. Finally, the study used the scale of impulse buying of Beatty and Ferrell (1998) to check whether the manipulation was successful (e.g. “When I bought flash drive, I felt a spontaneous urge to buy it.”, scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

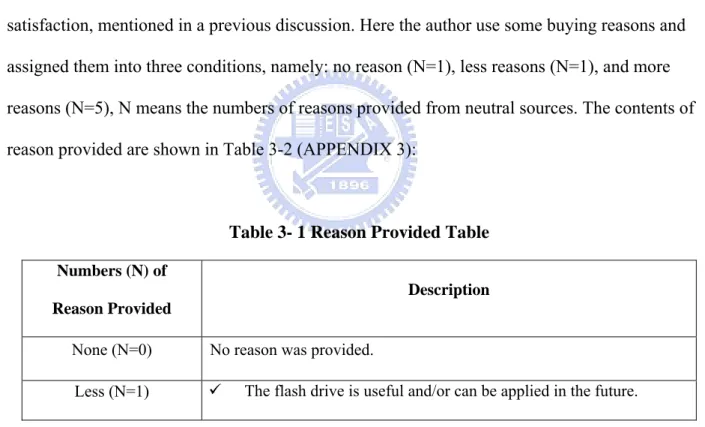

Manipulation of Reason Provided

Reason provided would have the effect of comfort and persuasiveness to influence satisfaction, mentioned in a previous discussion. Here the author use some buying reasons and assigned them into three conditions, namely: no reason (N=1), less reasons (N=1), and more reasons (N=5), N means the numbers of reasons provided from neutral sources. The contents of reason provided are shown in Table 3-2 (APPENDIX 3):

Table 3- 1 Reason Provided Table

Numbers (N) of Reason Provided

Description

None (N=0) No reason was provided.

More (N=5)

9 The flash drive is useful and/or can be applied in the future. 9 A famous flash drive is on sale! Of course you must buy it

immediately!

9 The flash drive looks pretty charming! It is handy and special. This will be a good buying decision!

9 It is too much of a waste of time and energy to return goods, so…accept it!

9 You bought the flash drive just for fun, now you are happy anyway, so it is worthwhile!

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Mood State

A mood scale adapted from Swinyard (1993) was used to check the effect of the mood manipulation. It measures mood at a particular point of moment on a simple good/bad continuum rather than attempting to assess various dimensions of mood (Bruner, Hensel, & James, 2005). The scale consisted of four summed bipolar measures coded in a seven-point scale and the alpha was originally.85. Our Cronbach’s α of the experiment was 0.974.

Scale Items: 1. sad / happy

2. bad mood / good mood 3. irritable / pleased 4. depressed / cheerful

3.3.2 Impulse Buying

The scale called impulsivity by Beatty and Ferrell (1998) is composed of five, seven-point Likert-type statements measuring the extent to which a consumer indicates experiencing a strong urge to spontaneously make a particular purchase without hesitation or consideration of the consequences (Beatty & Ferrell, 1998). The scale developed in dissertation research by Jeon (1990) was unidimensional and they showed validity with a coefficient alpha of .70. A mean score of 4 or above represented impulsivity. Our Cronbach’s α of the experiment was 0.758. Scale Items:

1. When I bought the flash drive, I felt a spontaneous urge to buy it.

2. When I bought the flash drive, I felt I would not be able to get it off my mind until I bought it.

3. When I bought the flash drive, I really did not consider the consequences of the purchase. 4. When I bought the flash drive, I did it without much hesitation.

5. When I saw the flash drive, I could not resist it.

3.3.3 Satisfaction

The scale is composed of twelve Likert-type items and measures consumers’ degree of satisfaction with a product they have recently purchased (Bruner et al., 2005). It was originally generated and used by Westbrook and Oliver (1981) measure consumer satisfaction with cars but Mano and Oliver (1993) appear to have adapted it so as to be general enough to apply to

whatever a respondent was considered. The research followed Oliver and Swan (1989) to use a seven-point format with their alphas of .94. Our Cronbach’s α of the experiment was 0.870 after the validity was qualified as required.

Scale Items:

1. This is one of the best flash drive I could have bought. 2. This flash drive is exactly what I need.

3. This flash drive hasn’t worked out as well as I thought it would. ® 4. I am satisfied with my decision to buy this flash drive

5. Sometimes I have mixed feelings about keeping it. ® 6. My choice to buy this flash drive was a wise one.

7. If I could do it over again, I would buy a different make/model. ® 8. I have truly enjoyed this flash drive.

9. I feel bad about my decision to buy this flash drive. ® 10. I am not happy that I bought this flash drive. ® 11. Owning this flash drive has been a good experience. 12. I am sure it was the right thing to buy this flash drive.

3.3.4 Tendency to Regret

The article used a regret scale which is from the American Psychological Association to evaluate the levels of regret. After summing up all the scores of the questions, the scale shows that the higher the total amount, the easier people feel regret (Schwartz, 2004). The point is from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Our Cronbach’s α was .711 after the validity was qualified as required.

Scale Items:

2. Every times I make a decision, I always want to know what would have happened if I had made a different choice then.

3. Even though I have made a good decision, I still feel I have lost if a better choice is found. 4. I collect related information of all alternatives before making a decision.

5. When I recall my performance, I usually take a missed opportunity to heart.

3.4 Data Collection and Analysis Method

First, an Independent-Sample T Test was employed to compare if mood states (positive vs. negative) and impulsiveness (high vs. low) have significant differences under stimulus

manipulation. Then, to understand the influence of moderators of prior mood and tendency to regret on reason provided and satisfaction, ANOVA was used to test the interaction. Satisfaction was analyzed separately for the two variables to probe into the effect of reason provided.

CHAPTER 4 RESEARCH ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

This chapter demonstrated the analyses and results of this research, including background of respondents, manipulation check, reliability and validity of the results, and a series of data

analyses techniques, such as ANOVA, multi-comparison, and an Independent-sample T test. After manipulation and data collection, the data was coded, sorted, and tested the meaningfulness of this study. At this point, this research used SPSS 12.0 to analyze the data.

4.1 Manipulation Check

A pretest was conducted to test the validity and reliability of the questionnaires and to discover any problems or misunderstandings of the design in the experiments. The pretest was made by giving the experiment tests and the questionnaires to 79 respondents, debriefing the research purpose to reduce the uncertainty in the survey.

The selected pictures were checked to see if they would influence people’s mood states, and if the impulse-inducing scenario would work to restrict the condition under impulse buying. The reliability of the mood scale and the impulsivity scale was .978 and .782 respectively (Table 4.1). The validity of the two tests was also accepted.

In the first part of pretest, the study collected 79 samples. 37 respondents were in the set of positive mood and 42 respondents were in the set of negative mood. There was a significant difference between positive mood and negative mood sets (positive mood mean = 5.446; negative mood mean =3.499; t-value=16.191, p<.001); thus, the manipulation was successful. In the second part of pretest, the study also had 79 effective samples. If the mean value of the sample was significantly over 4, the manipulation was successful. Consequently, the result showed that

the respondents who decided to purchase the impulsive item fitted in with impulse buying behaviors (mean=4.4658; t-value=3.795; p<.001). The manipulation was effective.

Table 4- 1 Reliable Statistics of Manipulation Check

Reliability Statistics Cronbach's Alpha

Cronbach's Alpha Based

on Standardized Items N of Items

Mood Scale .974 .978 4

Impulsivity Scale .774 .782 5

4.2 Background of Respondents

The data were obtained from random sample of residents on the Internet. The total effective sample was 227 respondents. 67.8% were female, 96% aged 19-35 years old, 98.6% had

college/bachelor’s or master’s degree, and 82.3% were with a disposable income below NT30, 000. The demographic characteristics of the respondents were shown below: (Table 4.2)

Table 4- 2 Frequency Table

Demographics Category Frequency Percent (%)

Male 73 67.8% Sex Female 154 32.2% 15-18 8 3.5% 19-23 107 47.1% 24-28 99 43.6% 29-35 12 5.3% Age 36-42 1 .4% High School 3 1.3% Bachelor 169 74.4% Education

Master and above 55 24.2%

<10,000 134 59.0% 10,000-29,999 53 23.3% 30000-49,999 32 14.1% Disposable Income 50000-69,999 7 3.1%

>=70,000 1 .4% (Total participants =227)

4.3 Reliability and Validity of the Results

4.3.1 Reliability Analysis

The reliability of the data was tested with Cronbach’s α. If Cronbach’s α is above 0.7, the study is accepted as reliable. Table 4.3 demonstrated the values from reliability tests of four constructs. The result showed that of the reliability test of mood, impulsivity, and satisfaction was reliable (all above 0.7), and the reliability of tendency to regret would be qualified after two items were deleted.

Table 4- 3 Reliability Analysis

Construct (Original Items) Cronbach Alpha Item deleted Cronbach alpha after item deleted

Mood(4 items) .974 None --

Impulsivity(5 items) .758 None --

Tendency to Regret(5 items) .526 2 items .711

Satisfaction(12 items) .859 3 items .870

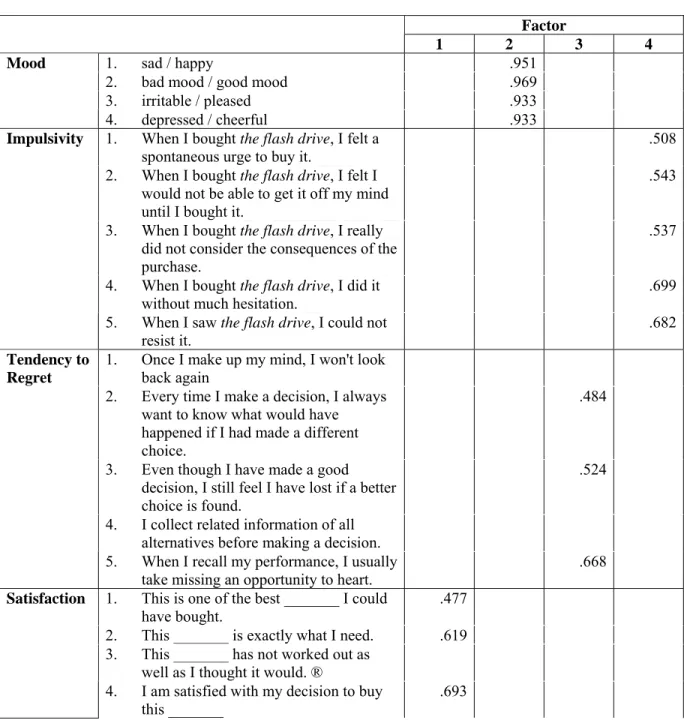

4.3.2 Validity Analysis

A principle axis factoring factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted. The criterion of factor extraction constrained four factors. The loading score of each item was higher than .4. The rotated factor matrix was presented in Table 4.4 and showed that the four concepts were loaded into four factors. However, the two loadings of the items of “tendency to regret” did not qualify for the concept; thus, item 1 and item4 would be eliminated in order to improve the reliability and validity of the study. The reliability of “tendency to regret” was improved

from .526 to .711 after the two items were deleted (Table 4.4). In addition, there were three unqualified loadings in the concept of satisfaction, namely items 3, 5 and 7. All of the three items were reverse items. After deleting these items, the reliability of satisfaction was up to .870 (Table 4.3), and the validity of the research was qualified as required.

Table 4- 4 Factor Analysis

Factor

1 2 3 4

1. sad / happy .951

2. bad mood / good mood .969 3. irritable / pleased .933

Mood

4. depressed / cheerful .933 1. When I bought the flash drive, I felt a

spontaneous urge to buy it.

.508 2. When I bought the flash drive, I felt I

would not be able to get it off my mind until I bought it.

.543 3. When I bought the flash drive, I really

did not consider the consequences of the purchase.

.537 4. When I bought the flash drive, I did it

without much hesitation.

.699

Impulsivity

5. When I saw the flash drive, I could not resist it.

.682 1. Once I make up my mind, I won't look

back again

2. Every time I make a decision, I always want to know what would have happened if I had made a different choice.

.484

3. Even though I have made a good decision, I still feel I have lost if a better choice is found.

.524 4. I collect related information of all

alternatives before making a decision.

Tendency to Regret

5. When I recall my performance, I usually take missing an opportunity to heart.

.668 1. This is one of the best _______ I could

have bought.

.477 2. This _______ is exactly what I need. .619 3. This _______ has not worked out as

well as I thought it would. ®

Satisfaction

5. Sometimes I have mixed feelings about keeping it. ®

-.589 6. My choice to buy this _______ was a

wise one.

.672 7. If I could do it over again, I would buy a

different make/model. ®

8. I have truly enjoyed this _______. .730 9. I feel bad about my decision to buy this

_______. ®

.491 -.504 10. I am not happy that I bought this

_______. ®

.487 -.461 11. Owning this _______ has been a good

experience.

.692 12. I’m sure it was the right thing to buy

this _______.

.769

Eigenvalues 4.099 3.673 2.547 2.078 Rotation Sums of Squared

Loadings

% of Variance 15.767 14.126 9.797 7.993

4.4 Hypotheses Test

After assuring the manipulation, reliability and validity of the analyzed data, the study proceeded to conduct ANOVA, General Linear Model and Independent-Sample T Test to test the hypotheses.

4.4.1 Reason Provided and Satisfaction

Reason provided was given into three groups respectively: zero, one, and five reasons provided. ANOVA was used to test if satisfaction differed when the number of reasons provided differed. In hypothesis 1, the study speculated that impulsive consumers with more buying reasons were more satisfied than those with fewer reasons, and more satisfied than those with no reason.

Table 4.5 showed the descriptive statistics of the analysis and Table 4.6 presented ANOVA results which indicated that the main effect was significant (p<0.1). After multiple comparisons with least square deviation (LSD), the research found that statistically significant differences

existed between zero reasons and five reasons (p<0.1). No significant differences existed among groups of zero to one and one to five reasons provided (Table 4.7). Thus, H1a was not supported, suggesting that impulsive consumers with more reasons for buying were more satisfied than those with fewer reasons. H1b was not absolute. There was no significant difference between zero and one reason provided, however, statistical differences occurred between zero and five reasons. The result indicated that H1b was supported when sufficient buying reasons were provided

Table 4- 5 Descriptive Statistics of Reason Provided

Reason N Mean Std. Deviation

Zero 75 4.6519 .71528

One 78 4.8162 .68466

Five 74 4.9159 .75108

(Dependent Variable: Satisfaction)

Table 4- 6 Tests of Mood, Tendency to Regret and Reason Provided

Source Type III Sum

of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. Reason 2.886 2 1.443 2.862 .059 Mood .139 1 .139 .275 .600 Tendency to Regret .916 1 .916 1.816 .179 Reason * Mood .084 2 .042 .083 .920 Reason * Tendency to Regret 2.354 2 1.177 2.334 .099 Mood * Tendency to Regret 2.003 1 2.003 3.973 .048 Reason * Mood * Tendency to Regret 1.007 2 .504 .999 .370

R Squared = .080 (Adjusted R Squared = .032)

Table 4- 7 Multiple Comparisons (LSD) (I) Reason

Provided

(J) Reason

Provided Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error p-value

Zero One -.1644 .11484 .154

Zero Five -.2641 .11636 .024

One Five -.0997 .11524 .388

4.4.2 Mood and Satisfaction

H2 was to check whether mood prior to shopping influenced impulse buyers’ satisfaction. The papers discussed before stated that consumers in a good mood before shopping would have higher satisfaction than those in a bad mood.

Stimulant pictures classified participants into two groups, a positive mood and a negative mood respectively. The hypothesis was tested by comparing the means of satisfaction for each group; thus, an independent-sample T test was used to determine the difference in satisfaction between the two mood classifications. Eventually, the study found out that mood states prior to purchase was indifferent to the degree of satisfaction (Table 4.8). Hypothesis 2 was not supported (p>0.1).

Table 4- 8 Descriptive Statistics of Mood

Mood N Mean Std. Deviation

Positive Mood 116 4.7692 .71306

Negative Mood 111 4.8208 .73339

t-value = -0.538, p-value = 0.591

4.4.3 Mood with Reason Provided and Satisfaction

H3a and H3b predicted that as buying reasons were provided, impulsive buyers in a negative mood would have more significant increased post-purchase satisfaction than those in a positive mood. However, according to H2 presented above, mood prior to purchase was indifferent to satisfaction, and Table 4.6 suggested that there was no interaction effect between mood and reason provided (p>0.1). As a whole, the study found that impulse buyers would not change their satisfaction depending on mood prior to purchase, and mood prior to purchase would not change the association between reason provided and satisfaction. Although there were some directional differences in the mean values shown in Table 4.9 and Figure 4.1, statistically no interaction effect existed between moods prior to purchase and reason provided. H3a and H3b were not supported.

Mood prior to purchase and tendency to regret showed interaction effect in Table 4.6 (Figure 4.2). When respondents were in a positive mood, there were no differences between people with a high tendency to regret and with a low tendency to regret (p>0.1); however, there were significant difference when they were in a negative mood (p<0.1).

Table 4- 9 Descriptive Statistics of Mood and Reason Provided

Reason Provided Mean (Std. Deviation)

Zero Reason One Reason Five Reasons Positive Mood 4.5916 (.69194) 4.8307 (.65493) 4.8769 (.77988) Negative Mood 4.7105 (.74178) 4.7994 (.72682) 4.9550 (.72976)

Figure 4- 1 Interactions between Mood Prior to Purchase and Reason Provided 4.5916 4.8769 4.7105 4.955 4.8307 4.7994 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 5

Zero One Five Reason Provided

Satisfaction Positive Mood Negative Mood

Figure 4- 2 Interactions between Mood Prior to Purchase and Reason Provided

4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 5 Positive Negative

Mood Prior to Purchase

Satisfaction Low

High

4.4.4 Tendency to Regret with Reason Provided and Satisfaction

According to the papers discussed before, the study perceived people with higher tendency to regret would be more sensitive to reason provided after impulse buying. Median value (median value =4.6667) was used to classify participants into two groups. Thus, there were 114

respondents in high tendency to regret and 113 respondents in low tendency to regret.

When the study used tendency to regret as an independent variable, there was no difference in satisfaction between the two tendency groups. The main effect was not significant (Table 4.6).

However, there was some interaction between tendency to regret and reason provided (p<0.1), suggesting that the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction would be influenced by tendency to regret. Table 4.6 and Figure 4.2 showed the interaction between tendency to regret and reason provided. Multiple comparisons were used to test the inference. As a result, when reason provided was from zero to one reason, satisfaction of consumers with a high tendency to regret had significantly increase than those with low tendency to regret’s increase, supporting H4a. But the dissimilarity of satisfaction between zero to one and one to five reasons provided were indifferent to people with a high tendency to regret and a low tendency to regret. H4b was not supported (Table 4.10). For the three groups of reason provided, low tendency to regret was indifferent to satisfaction (p>0.1) but significantly different for high tendency to regret (p<0.05). For low tendency to regret, zero to one and zero to five reasons provided a significant increase in satisfaction did not exist; for one to five reasons provided a significant increase existed. For a high tendency to regret, for one to five reasons provided a significant increase in satisfaction did not exist; for zero to one and zero to five reasons provided a significant increase existed (Table 4.12 & Table 4.13).

Table 4- 10 Contrast Tests

Contrast Estimations Value of Contrast Std. Error t df p-value 1. 5-4>2-1 .4411 .23043 1.914 221 .057 2. 6-5>3-2 -.3119 .23138 -1.348 221 .179 3. 6-4>3-1 .1292 .23302 .554 221 .580

Table 4- 11 Descriptive Statistics of Tendency to Regret and Reason Provided

Reason Provided Mean (Std. Deviation)

Zero Reason One Reason Five Reasons

Low Tendency to Regret 4.8348(.77849) 4.7804(.54135) 5.0256(.69035)

High Tendency to Regret 4.4737(.60621) 4.8603(.83424) 4.7937(.80582)

Total numbers =227

Table 4- 12 Multiple Comparisons of Tendency to Regret and Reason Provided Reason Provided Tendency to Regret I J Mean Difference (I-J) Std. Error Sig. Zero One .09039 .15325 .556 One Five *-.26456 .15325 .087 Low Zero Five -.17417 .15620 .267 Zero One *-.41813 .17157 .016 One Five .06899 .17273 .690 High Zero Five *-.34914 .17273 .046 Dependent Variable: Satisfaction *The mean difference is significant at the 0.1 level.

Table 4- 13 Summary of Contrast Analysis

Reason Provided Tendency to Regret 0-1 1-5 0-5 Low X O X High O X O

Figure 4- 3 Interactions between Tendency to Regret and Reason Provided 4.8348 4.7804 5.0256 4.4737 4.8603 4.7937 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 5 5.1

Zero One Five Reason Provided

Satisfaction Low Tendency to

Regret

High Tendency to Regret

4.5 Results of the Tested Hypotheses

Table 4- 14 Results of the Hypotheses

Hypotheses Description of the hypotheses Results

Hypothesis 1 Impulsive consumers who are provided with more buying reason are more satisfied than those who are provided with fewer buying reasons.

1a: One reason is better than no reason.

1b: Five reasons are better than one reason. Reject Reject Hypothesis 2 Consumers in a good mood will have higher satisfaction

than those in a bad mood. Reject

Hypothesis 3 Impulsive buyers in a negative mood before making a buying decision have more significant increasing post-purchase satisfaction when buying reasons are provided than those in a positive mood.

3a: One reason is better than no reason. 3b: Five reasons are better than one reason.

Reject Reject Hypothesis 4 Impulsive buyers with a higher tendency to regret have

more significant increasing satisfaction when buying reasons are provided than those with a lower tendency to regret.

4a: One reason is better than no reason.

CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

5.1 Discussion of Results5.1.1 Reason Provided and Satisfaction

Previous discussion indicated that consumers who received post-purchase support would be more satisfied with the products and the store they had shopped in(Hunt, 1970). The result showed consistent conclusion that reason provided is contributive to satisfaction. However, further analysis found that only when reason provided was from zero to five, satisfaction would significantly increase, indicating those customers who were provided sufficient buying reasons would have higher satisfaction toward the goods they had just bought impulsively. This finding corresponded to the previous papers that buyers produced dissonance after impulse buying (Sweeney et al., 2000 ); thus, they would look for supportive evidences to reduce the pressure of dissonance (Hunt, 1970). As impulse buyers were provided sufficient buying reasons from neutral sources, they would feel comforted or encouraged about their impulse buying decisions and their satisfaction would increase after being persuaded. However, it was not significantly increased when reason provided was from zero to one or one to five. There were two possible explanations for the differences. First, for impulse buyers, only one reason was not effective enough to influence satisfaction. And from one to five reasons provided, the increased range was not big enough to result in a difference. Providing a sufficient number of reasons was a key factor. Second, strong argumentswere generally more persuasive(Gibbons, Busch, & Bradac, 1991). The content of some reasons might not be strong enough to increase the persuasion. Therefore, no significant difference existed between zero to one and one to five reasons provided.

5.1.2 Mood, Reason Provided and Satisfaction

Many theses showed positive association between mood and satisfaction (Dawson et al., 1990; Gardner, 1985). However, the results showed that there was no significant difference between positive and negative moods. One of the possible explanations of the result was that the effect of mood manipulation did not last until participants responded to satisfaction. When participants made impulsive decisions, they had already forgotten their prior mood states, thus, mood manipulation did not work upon post-purchase satisfaction. The indifference might also result from the manipulated pictures which were not personally relevant to respondents. People with high involvement in processing a message enhance the elaboration of a message(Andrews, 1990). If the pictures could not arouse people’s personal concern, they were not greatly

influenced by these pictures.

In addition, there was no interaction between mood and reason provided. Owing to information from a previous discussion, this paper considered that consumers with a positive mood prior to purchase would be more satisfied than those with a negative mood prior to purchase (Dawson et al., 1990; Mackie & Worth, 1989). Buyers with a negative mood would increase satisfaction more significantly as reasons were provided. However, there was no difference in satisfaction between those in a positive mood and negative mood among the three reason provided groups. Mood prior to purchase did not moderate the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction. The interaction effect between mood prior to purchase and tendency to regret suggested that when people were in a positive mood, there were no difference in satisfaction between those with a high tendency to regret and with a low tendency to regret; however, when they were in a negative mood, people with a low tendency to regret were more satisfied than those in a high tendency to regret. Maybe this is because that people with a low

tendency to regret would have better ability to repair their negative mood, and then have higher satisfaction.

5.1.3 Tendency to Regret, Reason Provided and Satisfaction

There was no difference in satisfaction between people with high a tendency to regret and with a low tendency to regret. Because there was an interaction between reason provided and tendency to regret, this article excluded reason provided in order to understand the result that, when the effect of reason provided was eliminated, and respondents were restricted to zero reason provided only, in terms of satisfaction, people with a low tendency to regret were significantly better than those with high tendency to regret (t=2.245, p<0.05). Therefore the study inferred that when reason was not provided, consumers with a low tendency to regret were more satisfied than those with a high tendency to regret.

In addition, people with a high tendency to regret had significantly increased satisfaction when they were provided with one buying reason, but consumers with a low tendency to regret did not. Reason provided contributed to rationalization, and regret were mitigated when

consumer considered the decision was appropriate under the circumstances(Inman & Zeelenberg, 2002). Hence, people with a high tendency to regret were more sensitive to reason provided, especially when the number of reasons was increased from zero to one. One reason was greatly strong for those people who were in serious regret. H4a was supported.

Then, the research based on directional difference in satisfaction suggested that consumers with a low tendency to regret would not be influenced until five reasons were provided. Because they would not feel regret so easily about their buying decisions(Schwartz, 2004). Only providing with sufficient buying reasons were useful to increase satisfaction effectively. However,

consumers with a high tendency to regret were greatly increasing satisfaction when once one reason was provided because they were badly in need of supports to reduce dissonance than those with a low tendency to regret. In brief, for one to five reasons provided, consumers with a high tendency to regret did not have significantly increased satisfaction, but those with a low tendency to regret did. That’s why H4b was not significant. For zero to five reasons provided, both

tendency types of consumers had significantly increased satisfaction, so there was no significant difference between their dissimilarity measurements.

5.2 Implications

There are more and more marketing activities and promotions nowadays. These attractive activities make customers purchase impulsively more often than ever, and then this results in a bad feeling toward the stores, low satisfaction with the products, and a high return rate. In order to build a good relationship with customers and raise satisfaction which falls because of impulse buying behavior, reason provided is an effective action in the post-purchase service. Through neutrals’ opinions and appreciation of products expressed on the internet, impulsive buyers will be more satisfied with the products after being encouraged or supported. Managers can use platforms on the internet, such as online forums, discussion areas, the bulletin boards system (BBS) or blogs to make the advantageous opinions be found on the internet and observe consumers’ reactions after certain marketing activities have been held. Even if there were any negative opinions in the discussion areas, marketing managers could receive the information and react immediately. The study discovered the importance of reason provided on satisfaction. That means managers could influence consumers’ post-purchase behaviors and satisfaction by

The research also analyzed if mood prior to purchase had any effects on satisfaction and the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction. The result was not conclusive. The

indifference may result from the imperfect mood manipulation failing to influence satisfaction, or the manipulated pictures provided were not relevant to consumers. Nevertheless, from a

marketing perspective, managers could still use some marketing activities to influence

consumers’ initial moods; for example, playing some games or lottery sessions before a special sale to increase their buying motivation and satisfaction.

Tendency to regret is a main factor in satisfaction, and it is helpful for managers to understand customers’ buying behaviors. Managers are supposed to apply the regret scale to figure out their customers and then aim at the consumers with a high tendency to regret to

provide exceptional post-purchase service tactics. For example, increasing their chances of being exposed to reason provided, sending thank you cards after they buy impulse-stimulating items, to strengthen their positive impression of the stores and products. With the applications of this research, managers can increase consumer satisfaction and reduce return rates; thus maintaining a long-term relationship with customers and creating more value for their companies.

5.3 Limitations

At first, the research focused on the virtual environment and the data was mainly from the Internet, 96% respondents were 19-35 years old and all were students. If the study extended the sample to an off-line environment and other ages and occupations, a more general investigation could be conducted. Second, because of a technique restriction, static pictures instead of vivid films to manipulate mood states were used. Besides that, the content of the manipulated-pictures were not personally relative. The effect of the experiment might be influenced by the form and

the content of manipulated material. Third, a flash drive was used as the impulsive item. More product categories are supposed to be used to check the consistency of the result. Some specific occasions which more easily bring about people’s buying impulse, such as a special sale of name brands, an anniversary sale of a department, could also have been applied for the experiment. Fourth, in order to reduce the complexity of the research, to control the source of reason provided was only from neutral people. More diverse sources of reason provided, such as clerks, friends or family, could be used for further investigation. Fifth, the manipulation of impulse buying could not ensure that respondents produce dissonance after buying the flash drive because the impulse buying behavior did not really happen and respondents did not obtain the flash drive in the experiment. Dissonance state of the respondents should be further affirmed to make the result more accurate.

5.4 Future Research

The research focused on the relationship between reason provided and satisfaction, and related factors which may influence the relationship. However, besides mood before purchase and tendency to regret, more factors, such as product attributes, involvement, sources of reason provided, purchase channels or personal characteristics, might be essential for investigating the relationship. Future research could use clerks, friends, and family as the sources of reason provided, or examine the shopping values of consumers to study if there are going to be any change on the effect of reason provided. Tendency to regret will influence consumer satisfaction; therefore, the factor can be further conducted to understand the association with brand loyalty and post-purchase behaviors. Furthermore, many relative issues surrounding online shopping,