台灣華語字彙產製之音韻變化性 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Phonological variability in word production in Taiwan Mandarin. BY. 立. 政Hsin-Yi治Wang大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Linguistics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. Ch. engchi. June 2014. i n U. v.

(3) The members ofthe Committee approve the thesis of Hsin-Yi Wang Defended on June 26th, 2014. 三丫 。 ,. I-PingWan (^^^) Advisor. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Committee Member. / /Committee Member. n. al. ¤ÖZ. er. io. sit. y. Nat. " 乙刁L 。子. Approved. 一. Ch. \ // .,乙 臼□.. engchi. i n U. v. 片 ,亡一一. Hsun-Huei Chang (ff t^pf t), Director, Graduate Institute of Linguistics.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. Copyright © 2014 Hsin-Yi Wang All Rights Reserved iii. v.

(5) 致謝詞 能夠寫致謝詞大概真的是每位正在努力寫論文的研究生的夢想,口試結束到 現在我都一直還沒有「我終於可以畢業了!」的真實感,一直到這一刻,心裡想 著我的致謝詞裡面有多少人要感謝才終於比較踏實。 首先要感謝我的指導教授萬依萍老師,感謝老師儘管人在國外,仍不厭其煩 地一字一句地幫我修改論文;感謝老師在我對自己沒有信心時,不斷的鼓勵我, 告訴我一定沒有問題;感謝這三年裡,老師對我的指導和包容。感謝我的口試委 員:張郇慧老師、黃瓊之老師,以及林祐瑜老師。感謝老師們在百忙之中不辭辛 勞來參加我的口試。謝謝張郇慧老師,很乾脆地答應擔任我 proposal 的口試委員 且給我很多寶貴的意見;謝謝黃瓊之老師在邏輯上以及架構上給我很多想法;謝 謝林祐瑜老師給我很多統計上的意見。 謝謝所上的老師們這三年來的教導,讓我不管是在專業知識上或待人處事上 都有很多成長;謝謝助教學姊,從入學到畢業給我的照顧和協助;還有要最謝謝 親愛的 100 級的同學們,謝謝你們總是不吝於伸出援手,也在我不知道跟你們抱 怨幾次之後,還是跟我說加油,好喜歡跟你們一起吃飯、一起開讀書會,也好喜 歡每個人都好聰明、好幽默,以及都好有個性,因為有你們讓我的研究所生涯很 多采多姿,謝謝你們。 謝謝語音實驗室的夥伴們:謝謝涵潔學姊,不管是工作上、論文上或是生活 上都幫助我很多,你畢業之後我真的好想念有你在的實驗室;謝謝彥棻和冠霆幫 我分擔工作,跟你們一起聊天、一起八卦、一起工作大概會是我畢業之後最想念 的事情之一;也謝謝可愛又乖巧的學妹們:欣瑩、庭瑄、佳琳,謝謝你們對於我 交代的工作總是很配合而且做得很好,讓我輕鬆很多。 最感謝爸爸媽媽,對我的栽培和教養,讓我總是可以做自己想做的事而無後 顧之憂,謝謝你們明明就很關心我的論文,但是又怕給我壓力,所以從來不會過 問,希望我能讓你們驕傲。 還要謝謝我的男朋友,一直無止盡的聽我抱怨喊累以及謝謝你時不時問我 「論文怎麼樣了?」,然後在我趕論文的時候一直默默在我身邊,如果沒有你, 我大概真的很難完成這個學位。也要特別謝謝黃爸爸黃媽媽一直以來對我的照顧 和關心,真的謝謝你們。 最後謝謝所有曾經在 facebook 上留言、傳訊息給我,或是口頭上曾跟我說 過加油的大家。 這三年裡真的遇到不少挫折,但是大概就是憑著一股倔強,也因為身邊總 是有可愛又溫暖的人們,所以不管怎麼樣我也告訴自己,一但開始就不能放棄! 真的謝謝大家!!. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 2014/06/30. iv. i n U. v.

(6) Table of content Chapter 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The research background ..................................................................................... 4 1.2 Syllable analysis................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Research questions ............................................................................................... 8 1.4 Organization of the thesis .................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 Literature review ......................................................................................... 11 2.1 The development of speech production ............................................................. 11 2.1.1 Whole-word representation ..................................................................... 13 2.1.1.1 Ferguson and Farwell (1975) ..................................................... 13 2.1.1.2 Ingram (2002) ............................................................................ 15. 政 治 大 2.2 Factors of phonological variability .................................................................... 17 立 2.2.1 Physical factor........................................................................................... 18 2.1.2 Syllable ................................................................................................... 16. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.2 Phonological factors.................................................................................. 19 2.3 Introduction to Mandarin syllable...................................................................... 21. ‧. 2.3.1 Syllable types in Mandarin ....................................................................... 21 2.3.2 Tone........................................................................................................... 24. y. Nat. sit. 2.4 Syllable acquisition in cross-language studies................................................... 25. er. io. 2.4.1 English ...................................................................................................... 25. al. v i n C h................................................................................ 2.4.3 Taiwan Southern Min 28 engchi U 2.4.4 Beijing Mandarin ...................................................................................... 29 n. 2.4.2 German and Dutch .................................................................................... 27. Chapter 3 Methodology ................................................................................................. 31 3.1 Data collection ................................................................................................... 32 3.1.1 Participants.................................................................................................. 33 3.1.2 Procedures ................................................................................................... 34 3.1.3 Recording equipment .................................................................................. 36 3.2 Data analysis ...................................................................................................... 36 3.2.1 Transcription and coding......................................................................... 36 3.2.2 Criteria for target word ........................................................................... 38 3.2.3 Variability rate ......................................................................................... 40 3.2.4 Syllable type frequency ......................................................................... 43 v.

(7) 3.2.5 Substitution patterns of syllable type ...................................................... 44 Chapter 4 Results and Analysis .................................................................................... 47 4.1 Background information of the data .......................................................................... 47 4.2 Phonological variability ................................................................................... 50 4.2.1 Overall variability pattern ....................................................................... 53 4.3 Syllable analysis................................................................................................. 58 4.3.1Frequency of syllable type ......................................................................... 59 4.3.1.1 Monosyllabic words ....................................................................... 59 4.3.1.2 Disyllabic words ............................................................................ 62 4.3.2 Variability rate of syllable type ................................................................... 68 4.3.2.1 Monosyllabic words ....................................................................... 68 4.3.2.2 Disyllabic words ............................................................................ 69. 治 政 大 4.4.1 Overall substitution pattern ....................................................................... 71 立 4.4.2 Monosyllabic words .................................................................................. 73. 4.4 Substitution pattern ............................................................................................ 71. ‧ 國. 學. 4.4.3 Disyllabic words ....................................................................................... 75 4.5 Relationship between frequency, variability rate, and substitution pattern ....... 77. ‧. 4.5.1 Variability rate and frequency ................................................................... 78 4.5.2 Substitution pattern and frequency ........................................................... 80. y. Nat. sit. Chapter 5 Discussion ..................................................................................................... 83. er. io. 5.1 Summary of the findings .................................................................................... 83. al. n. v i n C hanalysis .................................................................. 5.3 Discussion on syllable type 87 engchi U 5.3.1 Syllable type frequency............................................................................. 88 5.2 Discussion on variability pattern ....................................................................... 85. 5.3.2 Substitution pattern ................................................................................... 89 5.3.3 Syllable type variability ............................................................................ 90 5.4 Concluding remarks ........................................................................................... 92 References ....................................................................................................................... 94 Appendixes A. The overall frequencies of syllable combination in disyllabic words.............. 100 B. The frequencies of syllable combination in disyllabic words of each participant. .......................................................................................................................... 103. vi.

(8) List of Tables. Table 2.1 Mandarin consonants ................................................................................... 22 Table 2.2 Possible syllable types in Mandarin (Wan, 1999:36) ................................... 22 Table 2.3 Five-point scale of Mandarin tone ............................................................... 25 Table 2.4 Acquisition of syllable (Ingram, 1978) ........................................................ 26 Table 2.5 Developmental order for the acquisition of syllable types in Dutch ............ 27. 政 治 大 Table 3.2 Inter- and intra立 transcriber reliability .......................................................... 37 Table 3.1 Participants’ age and recording duration ...................................................... 33. ‧ 國. 學. Table 3.3 The sample of coding ................................................................................... 38 Table 3.4 Phonetic forms and tokens of the word [khaj55] .......................................... 41. ‧. Table 3.5 The sample matrix of substitution pattern in different syllable types ......... 45. Nat. sit. y. Table 4.1 Information of participants .......................................................................... 48. n. al. er. io. Table 4.2 Tokens of different word types .................................................................... 49. i n U. v. Table 4.3 Number of target words and variation words of participants at each age ... 50. Ch. engchi. Table 4.4 Production of [xwa55] and [tʂhɤ55tʂhɤ55] of participant #1 at 1;3.............. 52 Table 4.5 Number of forms/tokens and variability rates for words of participant #1. .56 Table 4.6 Tokens and percentages of syllable types in monosyllabic words ............ . 59 Table 4.7 Percentages of syllable types of each participant in monosyllables ............ 61 Table 4.8 Tokens and percentages of syllable types in disyllabic words .................... 62 Table 4.9 Percentages of syllable types of each participant in 1st syllable .................. 64 Table 4.10 Percentages of syllable types of each participant in 2nd syllable ............... 65 Table 4.11 The overall frequencies of syllable combinations ..................................... 65 Table 4.12 The frequencies of syllable combinations of each participant................... 66 vii.

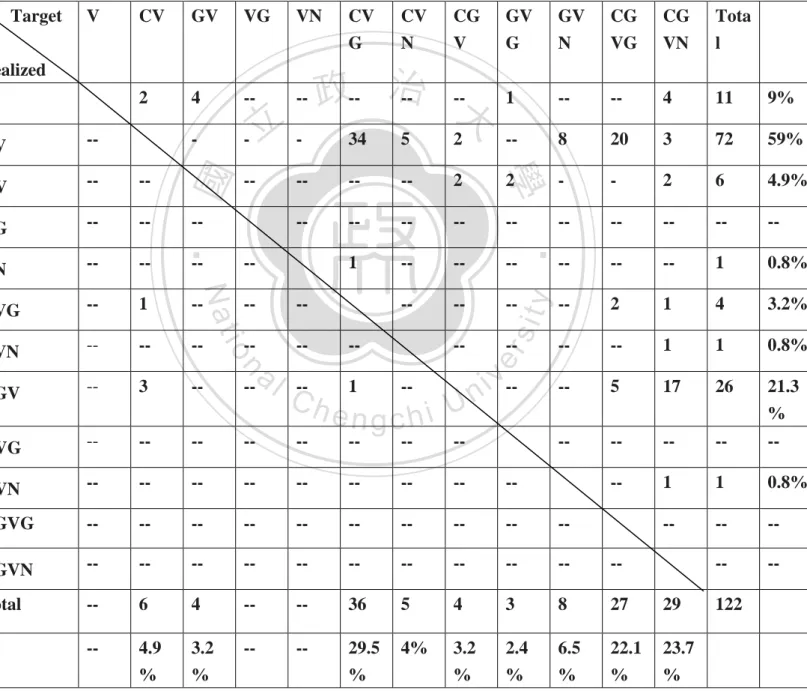

(9) Table 4.13 The substitution pattern of syllable types .................................................. 72 Table 4.14 Preferred substitutes of each syllable type ................................................ 76 Table 4.15 Frequencies of syllable types in all syllabic tokens................................... 81 Table 5.1 Ranking of syllable types in different measure ........................................... 83. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i n U. v.

(10) List of Figures. Figure 4.1 Overall variability patterns of each participant ......................................... 54 Figure 4.2 Percentages of syllable types in monosyllabic words................................ 60 Figure 4.3 Percentages of syllable types in disyllabic words...................................... 63 Figure 4.4 Variability rates of syllable types in monosyllabic words ......................... 69 Figure 4.5 Variability rates of syllable types in different word position..................... 70. 政 治 大 Figure 4.7 Percentages 立of replaced syllable types in monosyllabic words ................. 74 Figure 4.6 Percentages of realized syllable types in monosyllabic words .................. 73. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 4.8 Percentages of realized syllable types in disyllabic words ........................ 75 Figure 4.9 Percentages of replaced syllable types in disyllabic words ....................... 75. ‧. Figure 4.10 Frequencies of syllable types in disyllabic words ................................... 79. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Figure 4.11 Variability rates of syllable types in disyllabic words ............................. 79. Ch. engchi. ix. i n U. v.

(11) 國. 立. 政. 治. 大. 學. 研. 究. 所. 碩. 士. 論. 文. 題. 要. 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:台灣華語字彙產製之音韻變化性 指導教授:萬依萍 研究生:王心怡 論文提要內容 (共一冊,17,863 字,分五章). 政 治 大. 本篇論文是針對六位以台灣華語為母語的嬰幼兒,採長期觀察的方式,研究 台灣華語字彙產製的音韻變化性(phonological variability),並詳細描述單音節詞 和雙音節詞之中音節類型出現的頻率、變化性、以及代換模式。本研究同時要用. 立. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Jakoson (1968)的音節標記理論來檢驗各種音節類型中的共通性。 本研究一共觀察了有六位年齡在十一個月至兩歲的嬰幼兒長達一年。以兩個 禮拜一次的頻率收集嬰幼兒和母親之間的自然對話,並利用錄製回來的影音檔做 譯寫和分析。 結果顯示小朋友的音韻變化是很常見的,且是有規則可循的。小朋友的音韻. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 變異量的高峰(variability peak)會出現在當小朋友的音韻發展從一個階段進展到 另一個階段的時候,而本篇論文顯示與當小朋友由單字期(one-word stage)進展到 雙字期(two-word stage)以及字彙量有大幅上升的時期符合。華語音節習得的部分, 結果顯示 CV 是頻率最高、變化性最低,且最常被拿來替換的音節類型。CVG 也是頻率高的音節類型之一,但他的變化性也很高,主要是因為韻尾省略 (coda-dropping)的現象在小朋友的早期發展很常見的關係,所以 CVG 雖然頻率高 但是變化性也很高而且是最常被取代的音節類型之一。 最後,將所有的結果拿來檢驗 Jakoson (1968)的音節標記理論,結果發現頻 率高以及變化性低的音節類型都是無標記(unmarked)的音節類型,相反的頻率低. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 以及變化性高的音節類型則都是有標記的(marked)音節類型,此外小朋友會用無 標記的音節類型來取代有標記的音節類型。 關鍵詞:兒童語言發展、音韻變化性、音節習得、頻率、代換模式、台灣 華語. x.

(12) Abstract The purpose of this study is to discuss the issue concerning phonological variability of children acquiring Taiwan Mandarin. Two aspects are including in the following: the phonological variability of words and the syllable types composed the words. The overall variability pattern, the frequency, variability rate, and substitution pattern of syllable type were analyzed. Six participants are investigated in the study, aged between 0;11 to 2;0. A longitudinal observation study is conducted by the author and the research team. The results showed that phonological variability is common in early phonological development. The increase in variability reflects the reorganization of phonological system, where children started to produce two-word utterances and the amount of different words was increased. As for the syllable type analysis, CV presented the highest in frequency, the lowest in variability rate, and also was used to replace other syllable type more often. CVG was one of the most frequently used syllable type; however, the variability rate of CVG was also high. The reason may due. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. to the fact coda-dropping is a very common phenomenon in children’s development. The results in this study were examined in the markedness theory of syllable proposed by Jakobson (1968). The results showed that syllable types with higher frequency and lower variability rates were unmarked syllable types, while syllable types with lower frequency and higher variability rates were marked syllable types.. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. Furthermore, children tended to use a more unmarked syllable to replace a more marked syllable.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Keywords: phonological development, syllable acquisition, phonological variability, frequency, substitution pattern, Taiwan Mandarin.. xi.

(13) Chapter 1 Introduction The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the issue concerning phonological variability of children acquiring Taiwan Mandarin. Two aspects are included in the following: the phonological variability of words and the syllable types composed the words.. 立. 政 治 大. Early works on child phonology have focused on examining the order of. ‧ 國. 學. acquisition of segments, namely, individual speech sounds involving consonants,. ‧. vowels and their substitution patterns. However, less is known about the whole-word. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. pattern of acquisition. This ‘whole-word’ system was proposed by Ferguson &. v. n. Farwell (1975) who suggested that the minimal unit of lexical representation for. Ch. engchi. i n U. children in the earliest stages of language development is the syllable or word, not the phoneme. Both phonological variability and syllable analysis of words fit in the whole-word system, so it is important to investigate these two aspects in phonological acquisition from the whole-word point of view. In early phonetic and phonological development, children begin by babbling, and then they acquire their first words in just a few months, and finally, they begin to put words together into sentences. During the process, children’s early attempts at words. 1.

(14) 2. often sound quite different from adult pronunciations (Menn & Stoel-Gammon, 2009). A child’s first words often show many substitutions of one feature for another or one phoneme for another. These substitutions are simplifications of the adult pronunciations, which make articulation easier until the child achieves greater and more mature articulatory control. There is one problem that occurs during this period, which, however, has often been ignored in studies of language development; that is,. 政 治 大. phonological variability in the acquisition process.. 立. In phonological development, variability can be defined as repeated productions. ‧ 國. 學. of the same target words, and can be attributed to factors described in normal. ‧. acquisition and use of speech (Holm et al., 2007; Macrae, 2013; McLeod & Hewett,. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. 2008; Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2006 & 2012).Variability within individuals occurs in. i n U. v. two different forms. First, children have different realizations of a particular phoneme. Ch. engchi. for different lexical item, which refers to inter-word variability. For example, the phoneme /k/ in [kar] ‘car’ may be realized as [k], but in producing the word ‘cat’, the phoneme /k/may be pronounced as [t]. This phenomenon shows that children have not mastered the phoneme /k/. Secondly, children have different realizations for multiple productions of the same lexical item, which refers to intra-word variability (Ferguson & Farwell, 1975; Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2006 & 2012). For example, when a child attempts to produce /bebɪ/ ‘baby’, he or she may realize / bebɪ / as [bɪbi], [bibi], or.

(15) 3. [meɪbi] (Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2006). The present study will focus on the last aspect of phonological variability, which describes individuals’ repeated productions of the same lexical item. A child may produce one word consistently and another word variably. However, the variation is not unlimited; it appears to be quite principled (McLeod & Hewett, 2008). Therefore, it is important to investigate the value of phonological variability and to see what phonological variability might reveal about. 政 治 大. phonological development of children.. 立. Studies have shown that phonological variability is most likely to occur when. ‧ 國. 學. one or more aspect of the word is unstable in child’s phonological system; that is,. ‧. phonological elements were presented in a child’s speech, but not yet mastered (Holm. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. et al., 2007; Leonard et al., 1982; McLeod & Hewett, 2008). McLeod and Hewett. i n U. v. (2008) examined variability and accuracy of words containing consonant clusters in. Ch. engchi. children, aged 2; 0-3; 4. They found that 53.7% of all target words produced by all participants were variable. Compared to the study of Holm et al. (2007), 13% of the target words were produced variably by children aged 3; 0-3; 5, and only some of the target words contained consonant clusters. Although some of McLeod and Hewett’s participants were younger than the study of Holm et al., the different results from the two studies still indicated that words containing consonant clusters are produced with more variability. Words contained complex syllable structure are more difficult for.

(16) 4. children to produce, so children would use some strategies like dropping codas, or syllable substitution to make their articulation easier, resulting in phonological variability of words.. 1.1 The research background This section presents the research background of the phonological variability and syllable acquisition. To investigate the area of phonological variability, the first issue. 政 治 大. needed to be concerned is the relationship between age and variability pattern.. 立. However, it is still a question whether or not the phonological variability patterns of. ‧ 國. 學. children decrease or increase when children grow older. One potential pattern of. ‧. variability would be a steady linear decrease over the second year of life until. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. children’s productions become stabilized. Holm et al., (2007) examined the. v. n. consistency of word production in children aged between 3; 0-6; 0, and found that age. Ch. engchi. i n U. has a significant negative effect on variability; that is, when children grow older, their word variability tends to decrease. The study of Macrae (2013) is consistent with the previous study, in which children younger than three years old show the same decreasing variability with increasing age. On the contrary, some researchers have suggested that variability is relatively low during the very early stage of lexical development, and then increases as the number and phonetic diversity of the words the child attempted increase (Ferguson &.

(17) 5. Farwell, 1975; Vihman, 1993).. Sosa and Stoel-Gammon (2006) investigated the patterns of intra-word production variability of English-speaking children aged 1;0-2;0. Longitudinal data from four children were analyzed to determine variability at each age. The percentage of intra-word variability for each child at each age was calculated. The results showed that children even at two years of age still display a considerable amount of. 政 治 大. intra-word variability (variability rates above 20% at the final data collection session).. 立. The pattern of variability observed in these children showed peaks and valleys rather. ‧ 國. 學. than steady decreases in variability.. ‧. The second problem is the concern as to whether vowel difference should be. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. included in the calculations of accuracy and variability. Typically, vowel productions. i n U. v. are better than consonant productions and many studies excluded vowel difference. Ch. engchi. from analysis (Ferguson & Farwell, 1975; Leonard et al., 1982; Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2006 & 2012). For example, [ta] and [te] would be considered as the same phonetic form of a word. Other studies included vowels in their data analyses (McLeod & Hewett, 2008; Schwartz et al., 1980). Ingram (2001) pointed out that pervasive vowel errors in children’s production will require the inclusion of vowels. Bernthal et al. (2009) also suggested that by excluding vowels in calculations of word variability and accuracy in young children, researchers are ignoring an important area.

(18) 6. of phonological development. Since this study intends to investigate whole-word variability, repeated productions of a target word will be determined to be variable if differences are present in every aspect of the word including features, vowels, and consonants contained in the word. Furthermore, previous work did not talk about the individual difference of the pattern of phonological variability, so this thesis would not only investigate the overall pattern but also the individual pattern of variability.. 1.2 Syllable analysis. 立. 政 治 大. Many researchers have proposed that children acquire CV syllable first since CV. ‧ 國. 學. syllable is the core syllable which is the most unmarked syllable (Ingram, 1978; Stark,. ‧. 1980). Jakobson (1947, 1968) also proposed that children acquire CV syllable, and. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. gradually followed by more complex syllable type. The studies of Ingram (1978) and. v. n. Stark (1980) both showed that children acquire CV and CVCV form first since young. Ch. engchi. i n U. children often use augmented or truncated words in their early speech (Allen & Hawkins, 1978 & 1980), and V, VC, and CVC forms are the next types. This codadropping phenomenon is considered very common in phonological acquisition. However, some studies have found that word-final clusters were acquired several months earlier than word-initial clusters (Lleo & Prinz, 1996), and syllable-final consonants were mastered earlier than syllable-initial consonants (So & Dodd, 1995). In order to solve the inconsistence of acquisition order in syllables, researchers.

(19) 7. have studied the effect of frequency in the acquisition of syllable. Bernhardt and Stemberger (1998) proposed that there is a tendency for the less complex or more natural syllable structures to occur frequently in a language, and to be mastered earlier. However, in the case of children acquiring Taiwan Southern Min (Tsay, 2007), CVC is the second most frequent syllable in children’s speech, but the error rate of children producing CVC syllable is 98%.. 政 治 大. Since the acquisition order of syllables, the relationship between frequency. 立. and the acquisition of syllables still remain in much debate, it is necessary to. ‧ 國. 學. investigate the acquisition of syllables of different languages in the world.. ‧. The syllable types and syllable structure in Mandarin are relatively simple. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. compared to other languages. For example, English allows three consonant clusters in. v. n. the syllable onset, and Mandarin only allows two consonants in the onset-position and. Ch. engchi. i n U. the glide [j], or [w], and [ɥ], which are the phonetic variant of high vowels [i], [u], and [y], so they are even not considered as phonemes in Mandarin consonants (Duanmu, 2007; Lin, 2007; Wan, 1999). By investigating the acquisition of syllable from a language that has a lot of difference from languages such as English, this research aims to add cross-linguistic studies on literature of phonological acquisition and hope to clarify questions that were raised by former researchers. There are only a few studies concerning the issue of acquisition of syllable in.

(20) 8. Mandarin. It is still an issue whether the acquisition of Mandarin syllable has the same pattern as that of other languages is still not clear. The present study might hope to investigate the issues concerning phonological variability and syllable acquisition from children’s natural production. 1.3 Research questions The present study aims to investigate the intra-word production variability of six. 政 治 大. Taiwan Mandarin children, aged 0;11 to 2;0, excluding the pre-meaningful speech.. 立. Furthermore, since children’s early lexicon representation is the whole word, the. ‧ 國. 學. syllable types and structures in children’s speech are also of interest. A longitudinal. ‧. observation study of typically developing children acquiring Taiwan Mandarin has. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. been conducted.. n. The research questions to be addressed contain three parts and are described as follows:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. (1) Regarding the phonological variability: how prevalent is variability in children‘s speech during their early stage of phonological development? What are the patterns of phonological variability of children? Is the variability pattern a linear decrease over time or a linear increase over time? Or there are no regular patterns of phonological variability?.

(21) 9. (2) Regarding the syllable type: what is the general syllable type used among children? What is the most frequent syllable type used by the participants? What is the rank-order of frequency in different syllable types? What are the variability rates of different syllable types? Do syllable types that have higher frequencies present lower variability rates? Is there a relationship between the frequency of syllable types and its variability rate?. 政 治 大. (3) Regarding substitution pattern: are there any syllable substitution patterns in. 立. children’s production of variable forms of same words? Which syllable types. ‧ 國. 學. are more unstable and are replaced by other types more often? Which syllable. ‧. types are more likely to be chosen to replace the unstable ones? What kind of. y. Nat. er. io. sit. strategy would participants use to replace the syllable types they are not mastered yet? Would they replace the syllable types they are not mastered with. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. more frequent ones? Are there obvious individual differences among children's substitution strategies? 1.4 Organization of the thesis The thesis is organized as follows. Chapter one has laid out the introduction to the present study and the questions pertinent to the data analyses. In Chapter 2, firstly I will introduce the development speech production in first-language acquisition in 2.1, and the factors of phonological variability will be introduced in 2.2. Introduction to.

(22) 10. Mandarin syllable will be introduced in section 2.3. Syllable acquisition in cross-language studies will be presented in 2.4. Chapter 3 contains the methodology of this study. Section 3.1 is the data collection methods. How I obtained the speech tokens will be introduced in this section. Section 3.2 is the data analysis which explains how the data were arranged. Chapter 4 will present the results and analysis in tables and graphs. The overview of the overall data will be presented in section 4.1.. 政 治 大. Section 4.2 will present the pattern of phonological variability pattern of each. 立. participant. Section 4.3 will present the results of syllable analysis, including the. ‧ 國. 學. general syllable type participants produced, the frequency of syllable types in. ‧. different syllable positions, and the variability rate of different syllable types. Section. Nat. io. sit. y. 4.4 will present the substitution pattern between different syllable types. The. al. er. relationship between frequencies of syllable types and its variability rates as well as. n. v i n C h and substitution the relationship between frequencies e n g c h i U pattern will be summarized in section 4.5. The discussion and explanation is provided in chapter 5. Section 5.1 summarizes the findings in chapter 4. Section 5.2 presents the discussion on variability pattern. Section 5.3 presents the discussion on syllable type analysis. Section 5.4 will be the concluding remarks..

(23) Chapter 2 Literature review In this section, I will introduce the universal process of children’s speech production in 2.1. Second, I will introduce the factors of production variability of children in 2.2. Introduction to Mandarin syllable will be introduced in 2.3. Syllable. 政 治 大. acquisition in cross-language studies will be presented in 2.4.. 立. 2.1 The development of speech production. ‧ 國. 學. Children’s productions of sounds begin with simple cries at birth, and they. ‧. progress through several stages until they can produce complex babbling and. Nat. io. sit. y. adult-like intonation patterns. Many researchers proposed that children across the. er. world acquire different languages by similar steps (Lenneberg, 1967; Kaplan &. al. n. v i n Kaplan, 1971; Stark, 1980).C The of children’s early vocalization are shown h six e nstages gchi U in the following (Stark, 1980):. Stage 1: Reflexive vocalizations (0; 0-0; 2) -Most of the production are crying, fussing sounds, and vegetative sounds like coughing and sneezing. Some vowel-like sounds may occur. Stage 2: Cooing and laughter (0; 2-0; 4) - Infants interact with adults or older kids by using cooing sound and laughter.. 11.

(24) 12. Stage 3: Vocal play (0; 4-0; 6) - Infants begin to test their articulatory organs and use them to produce sounds. Stage 4: Reduplicated babbling (0; 6 and older) -The sequences of consonant-vowel (CV) syllables and adult-like intonation begin to appear at this stage. Stage 5: Non-reduplicated babbling (0; 10 and older) - Strings of sounds and. 政 治 大. syllables uttered with a rich variety of stress and intonation patterns are. 立. appeared. In addition to consonant and vowel sequence, other syllable. ‧ 國. 學. types also appear such as consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) syllable.. ‧. Stage 6: Single word production - Infants begin to produce protowords, and. Nat. io. sit. y. words used as symbols and refer to recurring objects or events.. al. er. Although researchers commonly refer children’s different vocalization period as. n. v i n Ctypes ‘stages’, these vocalization h e typically i U from one stage to another. For n g c hoverlap. example, consonant and vowel sequence has become a unit in the speech production in stage 4. The production of CV sequence may appear in the previous stages such as in vocal play stage; the production of CV sequence may also continue to appear into stage 5 (Stark, 1980)..

(25) 13. 2.1.1 Whole-word representation The following section will present the whole-word representation and its measurement. 2.1.1.1 Ferguson and Farwell (1975) Ferguson and Farwell (1975) proposed that the minimal unit of lexical representation at early developmental stages is the whole word or syllable rather than. 政 治 大. the segments or the phonemes. In other words, young children are able to be aware of. 立. relatively large phonological units, such as syllables or words, at early stages of. ‧ 國. 學. phonological development. Ferguson and Farwell proposed this ‘whole-word’ system. ‧. of phonological representation based on two observations. The first is the variability. Nat. io. sit. y. of individual phonemes in different contexts. For example, a child may have produced. al. er. initial [b] correctly in a specific set of words; however, when the initial [b] occurs in. n. v i n C h set, the child may contexts other than the specific e n g c h i U produce the initial [b] in many different forms. This pattern of production suggests that the child has not mastered /b/ as an individual phoneme, but rather only mastered [b] when it occurs in specific words. The second evidence supporting the whole-word representation is the prosodic variability (Ferguson, 1986). Ferguson and Farwell described a young girl who used ten different pronunciations of the word ‘pen’ in a one half-hour session. They.

(26) 14. suggested that this variation, in which multiple tokens of the same word are produced differently at the same point of time, may be referred to as intra-word variability. Aslin and Smith (1988) also supported the whole-word representation system of young children. They proposed that young children’s representation of lexicon is holistic in nature. Only later can they analyze a string of new sounds based on phonemic units. For example, in early phonological process, the representation of. 政 治 大. [dɔg] ‘dog’ is not organized as a sequence like [d] + [ɔ] + [g]. Instead, words are. 立. represented as overall acoustic shape. The common assumption regarding the. ‧ 國. 學. development of phonemic categories is that as the amount of vocabulary in children’s. ‧. lexicon grows, there is a need to discriminate the speech sounds efficiently in. Nat. io. sit. y. production and also in perception. As the result, the growth of children’s lexicon leads. al. er. to the development of phonemic representation. Therefore, children’s phonological. n. v i n development can be viewedC ash a gradual process from e n g c h i U a more holistic level to a more segmental level; that is, from whole-word representation to phonemic representation (Nittrouer et al., 1989; Waterson, 1971; Walley, 1993). When, precisely, the transition begins is not known, but assumption has been made that phonemic representation begins to emerge when a child has between 50 and 100 words, and the process may not be complete until much later in childhood, perhaps as late as 7;0 or 8;0 (Leonard et al., 1980)..

(27) 15. 2.1.1.2 Ingram (2001) Ingram (2001) proposed four measures of whole-word productions to estimate children’s whole-word abilities. Firstly, the Phonological Mean Length of Utterance measures the length of a child’s words and the number of correct consonants. Secondly, the Proportion of Whole-Word Proximity may capture how well a child approximates the target words. Thirdly, the Proportion of Whole-Word Correctness. 政 治 大. determines the proportion of a child’s words that are produced correctly out of the. 立. entire production. And fourthly, the Proportion of Whole-Word Variation provides a. ‧ 國. 學. method for quantifying the amount of intra-word phonological variability exhibited by. ‧. children.. Nat. io. sit. y. In order to obtain the phonological variability of children, the fourth measure. al. er. proposed by Ingram (2002), the Proportion of Whole-Word Variation, was adopted in. n. v i n C hvariability and phonological this study. The relation between representation is still not engchi U clear. However, one hypothesis is that a decrease in intra-word variability would reflect the emergence of a segmental phonological representation. On the other hand, an increase in variability might reflect that the phonological system is not stable when it starts to undergo reorganization, a transition from whole-word representation to segmental representation (Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2006)..

(28) 16. 2.1.2 Syllable Jakobson’s early work (1947, 1968) proposed a universal order of acquisition of syllable structure. He indicated that children begin the processes of phonological acquisition with the CV or CV reduplicated syllable and gradually followed by more complex syllable such as CVC and CVCV (where the second consonant-vowel combination is different from the first one). He also proposed ‘markedness theory of. 政 治 大. syllable’ which was summarized below:. 立. (1) The open syllable is more unmarked than the closed syllable.. ‧ 國. 學. (CVCVC, CVV). ‧. (2) The syllable with onset is more unmarked than those without onset.. Nat. (3) Syllable contained consonant cluster is marked.. n. al. Ch. (CVCCV, VCVCC). engchi. er. io. sit. y. (CVV, CVCVC). i n U. v. Stark (1980) proposed the order of stages in the speech production before infants begin to produce their first word. In the stage called canonical babbling, infants in their 6-month-old start to produce sequences of identical CV syllables with adult-like timing such as [mama] or [baba]. At around 12 or 13 months, syllable strings with varying consonants and vowels, like [bagidabu] emerge as the more frequent type in infants’ speech. When infants are 10-month-old, syllables like V, VC, and CVC start.

(29) 17. to emerge in infants’ production. Allen and Hawkins (1978, 1980) proposed that young children acquiring English tend to use the form of disyllabic trochaic feet. They observed that children often use augmented (CVC→CVCV) or truncated words. Furthermore, this early syllable structure might be a universal tendency; that is, children all over the world acquire languages with uniformity. Demuth and Johnson (2003) also found that children. 政 治 大. acquiring different languages use similar rules to truncate adults’ target forms. They. 立. examined the phonological acquisition of French in longitudinal data from one. ‧ 國. 學. French-speaking child, aged 1; 3-1; 5, and found that the child’s early words were all. ‧. reduplicated CVCV forms. The examples of English and French children are. Nat. al. n. French. [paˈtat] → [pəˈtæ:] ‘potato’. Ch. engchi. er. io. English [bənæ nə] → [‘nænə] ‘banana’. sit. y. presented as below:. i n U. v. Child acquiring English produced [bənæ nə] as [‘nænə], and child acquiring French produced [paˈtat] into [pəˈtæ:]. Both English and French children truncated trisyllabic word into disyllabic word. 2.2 Factors of phonological variability Variability appears frequently in the developmental phonology literature, and is often used as a diagnostic marker of phonological disorders. However, less is known about normal patterns of variability. The following section introduces the factors of.

(30) 18. phonological variability in typically developing children. Studies concerning phonological variability will also be presented. Production variability has been attributed to a number of different factors which summarized into the following categories: physical factor and phonological factors. 2.2.1 Physical factor The development of neuromotor control for speech that occurs during the period. 政 治 大. of early language acquisition can influence children’s speech production. Young. 立. children have been found to demonstrate high levels of variability in many different. ‧ 國. 學. aspects of motor control (Green, Moore & Reilly, 2002; Holm, Crosbie & Dodd, 2007;. ‧. Macrae, 2013; Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2012). In general, motor development might. Nat. sit. al. er. io. (Stoel-Gammon, 2006). y. be summarized as a process of increasing accuracy and decreasing variability. n. v i n Ch Green et al. (2002) investigated e n gthecsequential h i U development of the upper lip,. lower lip, and jaw movement of 1-, 2-, and 6-year-olds and adults during speech. The findings revealed that 1- and 2-year-old children’s jaw movements were significantly similar to adults’. However, 1-year-olds’ upper and lower lip movement patterns exhibited high variability, which would become more adult-like with maturation. These findings suggested that children’s early sound acquisition might be influenced by the inconsistent development of articulatory control, with the jaw preceding the.

(31) 19. lips. For example, it is easier for children to produce sounds formed by using mandible as primary mover like /b/ than those tend to be associated with lip control like /f/. According to Green et al. (2002), young children’s phonetic inventory was constrained by their dependence on the mandible to approximate adult-like speech targets resulting in the production of predictable speech errors and distortions. 2.2.2 Phonological factors. 政 治 大. There are a number of phonological factors of phonological variability to be. 立. discussed. The first is phonetic context. The position of sounds in a word may affect. ‧ 國. 學. the accuracy of production. Kenney and Prather (1986) examined the speech. ‧. consistency of children aged 2;5 to 5;0. They found that children produced phonemes. Nat. io. sit. y. /t, l, f/ more accurately in word initial than in word final position.. n. al. words that are difficult. er. The second phonological factor is phonological overload. It is not surprising that. v i n forCahchild to pronounce e n g c h i U will display greater. variability.. Leonard et al. (1982) examined 8 typically developing children ranging from 1; 10 to 2;2 years of age. They found that variability is most likely to occur when more than one phonological or structural feature of the target words that show instability in the child’s linguistic system. Furthermore, words with higher variability rates are most often those which have more advanced forms, sounds, or word shapes. Thus, variability can be seen as the result of phonological overload, which results in the.

(32) 20. simplification or substitution of sounds that are difficult for children to produce. The third factor of phonological variability is phonological complexity. McLeod and Hewett (2008) examined variability and accuracy in the production of words containing consonant clusters in typically developing children, aged 2; 0 to 3; 4. They found that the children in the study exhibited extensively variability when producing words that contained consonant clusters.. 政 治 大. Macrae (2013) investigated word variability and accuracy in children aged 1; 9. 立. to 3; 1. The study used Word Complexity Measure (Stoel-Gammon, 2012) to assign. ‧ 國. 學. score to a word based on the three levels of complexity: word pattern, syllable. ‧. structures and sound classes. The results showed that phonological complexity has a. Nat. io. sit. y. significant positive effect on word variability. Words with more complex speech. al. er. sounds are produced with more variability than those with less complex speech. n. v i n C h with the study sounds. These studies are consistent e n g c h i U of Ferguson and Farwell (1975) which also indicated the effect of phonological complexity on word variability.. The last factor of phonological factor is reorganization of phonological system. Sosa and Stoel-Gammon (2006) investigated the patterns of intra-word production variability of English-speaking children during their first year of lexical acquisition (1;0-2;0). The variability pattern observed by Sosa and Stoel-Gammon (2006) showed peaks and valleys. Three of the four children showed a very noticeable peak in.

(33) 21. variability. These peaks appeared when these children aged 1; 9 to 2; 0. It was also the time when two-word utterances were first observed in children’s speech. The results indicated that an increase in variability might correspond to instability in the phonological system when it undergoes reorganization: a movement from lexically-based system of phonological representation to segmental system. This view is consistent with dynamic systems theory, which proposed that variability is. 政 治 大. associated with transitions between developmental stages and is a potential force of. 立. 2.3 Introduction to Mandarin syllable. 學. ‧ 國. developmental change (Thelen & Bates, 2003).. ‧. Nat. 2.3.1 Syllable types in Mandarin. al. er. io. sit. Mandarin will be introduced.. y. There are two parts in this section. The possible syllable types and the tone in. n. v i n C h [ŋ] in Mandarin can All consonants except nasal e n g c h i U appear in the onset position, and. only nasals can be in the coda position. Prenuclear glides occurred in syllable initial position serve as an onset of the syllable, or it can occur before the syllable nuclear position. They are not considered as phonemes in Mandarin but can be treated as phonetic variants of high front vowels since the prenuclear glides do not contrast with the corresponding high vowels (Duanmu, 2007, Lin, 2007, Wan, 1999). Throughout this study, the Mandarin phones are presented by IPA system. Table 2.1 shows the.

(34) 22. description of possible consonant inventory, based on the studies from Lin (2007) Table 2.1 Mandarin consonants Bilabial Stop. Labiodental. Dental. ph. p. t. Fricative. f. ts. Nasal. m. Central approximant. w ɥ. Alveolo palatal -palatal. th. tsh. ɕ. tʂ. tʂh. tɕ. x tɕh ŋ. n ʐ. Lateral (Approximant). 立. Velar k. ʂ. s. Affricate. Postalveolar. j ɥ. 政l 治 大. w. ‧ 國. 學. In Table 2.1, symbols under the same place of articulation share every feature except for aspiration. The one on the left is voiceless unaspirated which is shaded, and. ‧. the one on the right is voiceless aspirated.. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Taiwan Mandarin allows at most four segments in a syllable, and is analyzed as. i n U. v. having twelve syllable types: V, CV, VG, GV, VN, CVG, CVN, CGV, GVG, GVN,. Ch. engchi. CGVG, and CGVN. The maximal syllable is CGVX, in which C is a consonant, G is a glide, V is a vowel, and X can be a glide or a nasal. Possible syllable types and examples are shown in Table 2.2. Table 2.2 Possible syllable types in Mandarin (Wan, 1999:36) Syllable type. Phonetic Transcription. Gloss. V. i55. dependent. CV. ma55. mother. kh.

(35) 23. GV. ja55. push. VG. aj51. love. VN. an55. safe. CVG. maj214. buy. CVN. tjŋ214. top. CGV. ɕjɛ35. shoes. GVG. jɑw35. shake. GVN. wan51. ten thousand. CGVG. 立. CGVN. tjɑw51 治 政 大 t jɛn55. drop. h. sky. ‧ 國. 學. In traditional analysis, Chinese syllable contains three parts: the first part is the Initial, which is optional and could be a consonant, a glide, or a nasal; the rest of the. ‧. sit. y. Nat. syllable after the initial consonant is the Final, which contains Medial and Rime. The. n. al. er. io. medial is the glide before the main nuclear vowel. Rime can be further divided into. Ch. i n U. v. two parts: the Nucleus, which is the main vowel in a syllable, and the Ending, which. engchi. could be a glide or a nasal. The third part is the Tone, which is considered a property of the whole syllable (Cheng, 1973). The phonological status of the prenuclear glides [j], [w], and [ɥ] in Mandarin Chinese has been well-studied but still remains as a controversial issue. Traditionally, the prenuclear glides are considered to be part of the final (Cheng, 1973), while Duanmu (1990) suggested that the prenuclear glides are not rime segments but secondary articulation on the onset. Duanmu (2007) pointed out that the.

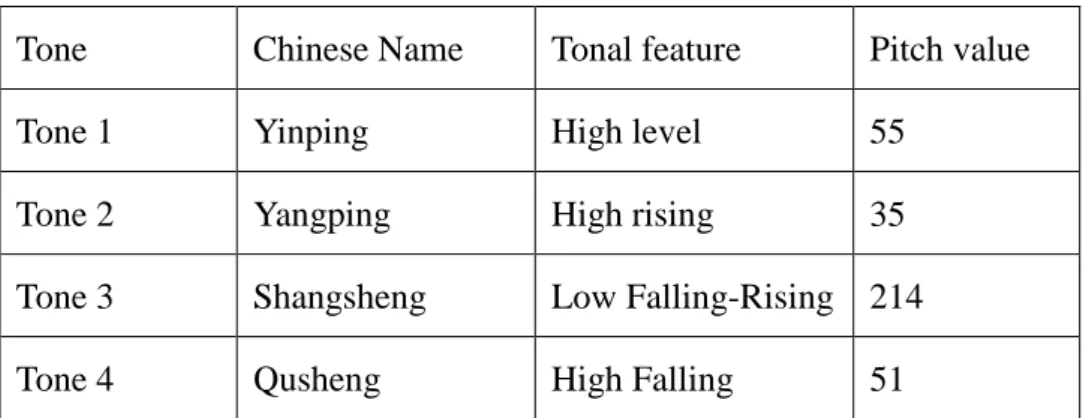

(36) 24. CG(C=consonant; G=glide) sequence, like [s] and [w] sounds in [swan] ‘sour’, is actually a single sound in Chinese, due to the fact that the lip rounding of [w] starts at the same time as [s]. In contrast, [sw] in English words like ‘sway’ are two sounds because the rounding of [w] occurs after [s]. Zhu and Dodd (2000) examined the phonological acquisition of Putonghua of 134 children aged 1;6-4;6 in Beijing. From the speech error pattern of syllable-initial. 政 治 大. consonant deletion, Zhu and Dodd pointed out that children acquiring Putonghua. 立. always delete the syllable-initial consonants before the vowels [i], [u], and [y]. This. ‧ 國. 學. pattern may reflect the flexible function of these three vowels: these vowels have their. ‧. variants [j], [w], and [ɥ], as mentioned before. Deletion occurs before these vowels. Nat. io. sit. y. suggested that children acquiring Putonghua have the tendency to cluster the. n. al. er. prenuclear glides with the nucleus; that is, prenuclear glides tend to group with rime. Ch. engchi. instead of onset in child phonology.. i n U. v. 2.3.2 Tone Syllable is a tone-bearing unit in Mandarin. People speaking tonal languages use tones to distinguish lexical meanings. Mandarin has four lexical tones and one neutral tone. Chao (1956) have provided a 5-point scale to specify the tone values in Standard Mandarin which were widely used and cited in most research on tone languages. Table 2.3 presents the five-point scale proposed by Chao (1956)..

(37) 25. Table 2.3 Five-point scale of Mandarin tone Tone. Chinese Name. Tonal feature. Pitch value. Tone 1. Yinping. High level. 55. Tone 2. Yangping. High rising. 35. Tone 3. Shangsheng. Low Falling-Rising 214. Tone 4. Qusheng. High Falling. 51. The four tones named yinping, yangping, shangsheng, and qusheng were. 政 治 大 [51] in the study of Chao 立(1965).. described as high level [55], high rising [35], low falling-rising [214], and high falling. ‧ 國. 學. The neutral tone usually appears in grammatical particles or in unstressed. al. sit. io. 2.4 Syllable acquisition in cross-language studies. er. Nat. is usually represented without any numeral citation.. y. ‧. syllable. Phonologically, a neutral tone was a low tone underlyingly (Lin, 2007) and it. n. v i n In this section, I will review C h studies of syllableUacquisition on different language, engchi including English, German, Dutch, Taiwan Southern Min, and Mandarin. Linguists are interested in whether there are language universals in first language acquisition. 2.4.1 English Ingram (1978) presented the acquisition order of different syllable structure of his daughter. The child acquired CV and CVCV form first, and then CVC. By the age of 2, she produced most words contained closed syllable, as showed in Table 2.3..

(38) 26. Table 2.4 Acquisition of syllable (Ingram, 1978) Monosyllabic words. Disyllabic words. 1;3. 89% CV. 87% CVCV. 1;6. mostly CVC. 47% CVCV. 2;3. Most of the words contained closed syllable. Ingram (1978) analyzed the monosyllabic and disyllabic token separately. In monosyllabic words, 89% percents of words were CV form at the beginning; however,. 政 治 大. when the child was one and six months olds, most forms in monosyllabic words was. 立. CVC. As for disyllabic words, 87% percents of words were CVCV form when the. ‧ 國. 學. child was one and three months olds, while only 47% percents of CVCV forms occur. ‧. in disyllabic words when the child aged 1;6. These previous studies showed that. y. Nat. er. io. sit. children master syllable onset consonants earlier than coda consonants. However, Kehoe and Stoel-Gammon (2001) found that codas were produced. al. n. v i n Ch early than onset by some English-speaking i U The reason might due to the e n g c hchildren. lexical frequency. Stoel-Gammon (1998) analyzed the phonological characteristics of approximately 600 early acquired words and found that the most frequent syllable was CVC, far exceeding the frequency of CV and CVCV forms. The relative frequency of codas in the target language influenced children's babbled productions. Thus, codas were presented in some English-speaking children's first words..

(39) 27. 2.4.2 German and Dutch Lleo and Prinz (1996) examined the acquisition of consonant clusters of five German-speaking children aged from 1;9 to 2;1. Their data showed the following acquisition order: CV>CVC>CVCC>CCVCC. Furthermore, they found that word-final clusters were mastered several months earlier than word-initial clusters for both groups of children.. 政 治 大. In order to explain the variance in phonological acquisition within syllable. 立. structures, recent researchers studied the effect of frequency on the acquisition of. ‧ 國. 學. syllable structures. Levelt et al. (2000) examined the development of syllable types in. ‧. longitudinal data of twelve children acquiring Dutch as their first language. The. Nat. io. sit. y. children’s ages ranged between 0; 11 and 1;11. The results showed that the input. n. al. er. frequency of different syllable structures in Dutch corresponded to the order in which. Ch. engchi. these structures were acquired and mastered.. i n U. v. Table 2.5 Developmental order for the acquisition of syllable types in Dutch A: > (5) CVCC, VCC> (6) CCV, CCVC (1) CV > (2) CVC > (3) V > (4) VC >. (7) CCVCC. B: > (5) CCV, CCVC > (6) CVCC, VCC The frequency of syllable types in the speech input appears to determine which learning path is followed. If the child has a choice between different learning paths, the path of the most frequent syllable type is chosen. If there is no noticeable.

(40) 28. difference between the frequencies of syllable types that correspond to different possible paths, variation is expected and attested. That is, there is a correlation between the frequency of a syllable structure in a specific language and how early that structure is acquired. 2.4.3 Taiwan Southern Min Tsay (2006) examined the prosodic structure and syllable omission pattern. 政 治 大. produced by young children acquiring Taiwan Southern Min, aged from 1; 6 to 3; 0.. 立. The results showed that over 70% of the attempted target words in children’s data. ‧ 國. 學. were monosyllabic words and disyllabic words were the second frequently used word. ‧. type, which is contradictory to the findings of Allen and Hawkins (1978, 1980) who. Nat. io. sit. y. proposed that young children acquiring English tend to use the form of disyllabic. al. er. forms. Tsay (2006) also found that children would use strategies, such as syllable. n. v i n C h There were U omission, to shorten long utterances. e n g c h i three patterns of children’s syllable omission: (1) Omission occurred in multisyllabic words more frequently than in. monosyllabic word. (2) Word-initial syllables were omitted more frequently than word-final syllables. (3) Syllable types consisting of VN, CVK (K stands for obstruent codas in Taiwan Southern Min [p], [t], [k], and [ʔ]), and V were the common omitted syllable types. Tsay (2007) examined the issue of the interactions between markedness and.

(41) 29. frequency in the domain of syllable types of children aged 1;2-4;4 acquiring Taiwan Southern Min. The study was based on the longitudinal data from Taiwan Child Language Corpus (Tsay, in preparation). The results showed that CV was the most frequently used syllable, followed by CVC, CVV, and V. More than 82% to 86% of children’s speech was these four syllable types. CV syllable is the core syllable and is considered as the most unmarked syllable across languages. The findings showed that. 政 治 大. the most unmarked syllable type CV was the most frequent syllable in children. 立. acquiring Taiwan Southern Min. However, frequency did not always have a positive. ‧ 國. 學. correlation with accuracy. For example, CVC was the second most frequently used. ‧. syllable in children’s speech; however, the error rate of children producing CVC. Nat. io. sit. y. syllable was 98%. The most common-error in syllable structure involved coda. al. er. dropping, which was a regular type in phonological acquisition (So & Dodd, 1995). n. v i n C hand Prince (1994),Uchildren’s early productions were and as mentioned by McCarthy engchi. governed by highly-ranked No-Coda constraints, which predicts that CV syllable types appear to be the most common output of syllable errors. 2.4.4 Beijing Mandarin Zhu and Dodd (2000) studied the phonological acquisition of Putonghua and found that the children’s errors suggested that Putonghua-speaking children mastered syllable elements in the following order: tone was acquired first; and followed by.

(42) 30. syllable-final consonants and vowels; and syllable-initial consonants were mastered last. In the study, vowels emerged early in the development. Both syllable-final nasals [n, ŋ] appeared in the children’s inventory at their 1;6, while the syllable-initial consonants was completed by 3; 6 for 75% of children. It is proposed that the saliency of the components in the language system determines the order of acquisition. Tone is more salient than the three other syllable components, so it is acquired by children. 政 治 大. earlier. Since syllable-initial consonants are optional, they have the lowest saliency of. 立. the four syllable components. So, children would master syllable-initial consonant. ‧ 國. 學. later.. ‧. In sum, at children’s early phonological developmental stage, the unit of lexical. Nat. io. sit. y. representation is the syllable or the whole word rather than the phonemes. Inter-and. al. er. intra-word phonological variability of children serves as evidence of this statement.. n. v i n This study will then focus C on h intra-word variability e n g c h i U produced by children acquiring Taiwan Mandarin. Two aspects are including in the following: the phonological variability of words and the syllable types composed the words. A longitudinal observation was conducted. The overall variability pattern, the frequency and variability rate of syllable type, and the substation pattern of syllable type will be discussed..

(43) Chapter 3 Methodology There are two parts in this methodology section. The first part includes the data collection, and the second part contains the data analysis. The data have been collected by the author and the research team in the Phonetics and Psycholinguistics. 政 治 大. Lab at National Chengchi University for many years. The whole study has been. 立. sponsored by the NSC research projects, “Consonant Acquisition in Taiwan Mandarin. ‧ 國. 學. (NSC 100-2410-H-004-187- )” and “Consonant acquisition in Taiwan Mandarin:. ‧. Evidence from longitudinal and experimental studies (NSC 101-2410-H-004-182- )”,. Nat. io. sit. y. both investigated by Professor I-Ping Wan.. er. Section 3.1 involves how I recruited the participants and their background. al. n. v i n C hprocedure and theUrecording equipments used during information. Furthermore, the engchi the data collection would also be detailed in this section.. For data analysis in section 3.2, I would present the methods of data transcription, the criteria for choosing target words, the formulas used in obtaining syllable type frequency and variability rate, and how the substitution pattern of different syllable types has been organized.. 31.

(44) 32. 3.1 Data collection The participated families were recruited from an advertisement posted on a non-profit parent forum called Babyhome (http://www.babyhome.com.tw/). An article was posted on the forum explaining the academic research purpose, the information of the NSC research project, and the age of recruiting children. Parents who wanted to participant in the research filled out the registration form we designed on “Google doc. 政 治 大. spread sheet,” which is an online questionnaire and can be customized in several ways.. 立. Sixteen families were enrolled under the study.. ‧ 國. 學. Some of the children in the NSC research project lived with their grandparents. ‧. who spoke Taiwan Southern Min, so the children might produced Taiwan Southern. Nat. io. sit. y. Min during the observation. Furthermore, some of the parents used English to. n. al. sometimes. In order to. er. communicate with their children, so the children might also produced English. v i n C out rule of languages h ethen ginfluence chi U. other than Mandarin. Chinese, these children would not be included in this study. At the end, only six children fit in this study, from which I collected four children, and the other two were collected by the research team. There were in a total number of 5868 tokens produced by six participants, among which 2088 tokens were transcribed by the assistants in the research team..

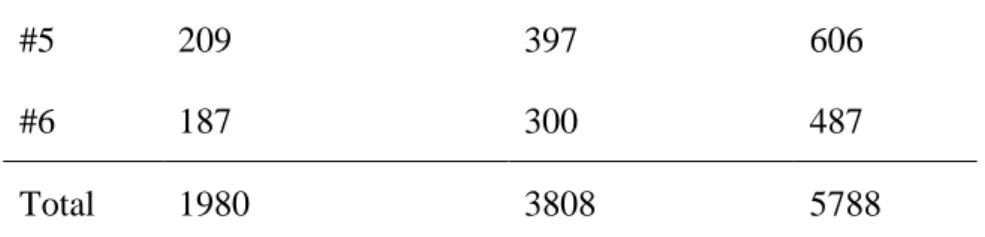

(45) 33. 3.1.1 Participants The background of the six children enrolled in this study shared several similarities. All of them were the only child in their family. They only lived with their parents, and they were all taken care by their mothers in the day time. All mothers used Mandarin Chinese to communicate with their children, so these children‟s first language was Taiwan Mandarin.. 政 治 大. All of them were from middle class family in Taipei. Two of them were boys and. 立. the other four were girls. Their ages were between 0; 11 to 1; 1 at the beginning of. ‧ 國. 學. observation. Since every child‟s phonological development was inconsistent, I. ‧. selected the age when they were in non-reduplicated babbling stage and have already. Nat. io. sit. y. produced their first meaningful word. The observation continued for twelve months.. n. al. healthy and appeared to. er. At the end, the participants‟ ages were between 1; 10 to 2; 0. All participants were. v i n C have h enormal h i Uas determined n g chearing,. through parental. interviews and observation of children during data collection. The participants‟ background information is presented below. Table 3.1 Participants‟ age and recording duration Participants. Gender. Age range. Duration. #1. M. 1;1-2;0. 12 months. #2. F. 1;0-1;11. 12 months. #3. F. 0;11-1;10. 12 months. #4. M. 0;11-1;10. 12 months.

(46) 34. #5. F. 0;11-1;10. 12 months. #6. F. 1;1-2;0. 12 months. 3.1.2 Procedures The data collection started from December 2011 to August 2013. There were eight research assistants in the research team. Every other week, two assistants were sent to a child‟s house in order to record the spontaneous speech between the child and the mother.. 政 治 大. On average, the recording was about sixty minutes for one time. Sometimes the. 立. recording time might be shorter if the children were tired, hungry, or cried. The. ‧ 國. 學. activity during recording was not limited. It could be share-book reading, eating, or. ‧. playing with toys. During the recording, in order to create a more natural context, the. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. mothers were encouraged to play with their children just like the way they always did. v. when they were home by themselves. Sometimes the assistants would also interact. Ch. engchi. i n U. with the children, using toys to attract children‟s attention and encourage them to talk. Children played with their mothers for the most of the time, since they were the people children were more familiar with. According to Lewedage et al. (1994), children produce well-formed syllables more frequently in home environment when familiar adults are present than in lab settings. No specific or systematic planning of elicitation was done during the recording, except for natural elicitations in daily life. For example, when the mother and the.

(47) 35. child were doing share-book reading activities, sometimes mother would ask the child to name pictures. The goal was to ensure that the data of this study was elicited from spontaneous speech, a method which increases the chances for variability since it involves the planning of longer utterances, including the need for syntactic planning and communicative intent (Dodd et al., 1989). The target words for analysis were selected in these spontaneous speeches. Therefore, the number and type of errors. 政 治 大. might be larger than a carefully controlled experimental task. However, it could. 立. reflect processes of phonological acquisition that occur in a more natural context. As. ‧ 國. 學. Ingram (2011) have claimed that syllables are best studied from words taken from a. ‧. spontaneous sample because they more directly reflect a child‟s preferred usage.. Nat. io. sit. y. Children‟s vocalizations were audio recorded during observations of their natural. al. er. daily activities in their homes. One of the assistants held the video recorder and the. n. v i n C during other held the sound recorder The assistant who held the video h e ntheg recording. chi U recorder had to make sure to film the children‟s face, mouth, and the objects they played with. The assistant who held the sound recorder had to stay near to the children. The participants were all paid volunteers and have had signed the human subject consent forms. At the end of the research project, the families would receive an album of video recordings as a souvenir. The rewards and cost were supported by the NSC.

(48) 36. research projects (NSC 100-2410-H-004-187- and NSC 101-2410-H-004-182- ). 3.1.3 Recording equipments Video-recording and sound-recording equipments were both used in this study. Sony DCR-SR40 Handycam digital video camera recorder and the Sony ICDUX513F digital voice recorder were used during the recording. The sizes of these equipments were small, so it is easy to carry. The equipments were provided by the. 政 治 大. lab and also sponsored by the two NSC research projects... 立. The video camera helped us record children‟s gestures, lip movement and things. ‧ 國. 學. they played with. The video could provide us some clues to decode the referential. ‧. meaning of children‟s utterance. The sound recorder provided us high quality sound. Nat. sit. al. er. io. 3.2 Data analysis. y. files which could help us distinguish the sounds children uttered.. n. v i n The participants in the C observation were around one-word stage, but their h e n gperiod chi U. utterances were longer than two syllables, so the study will analyze children‟s monosyllabic and disyllabic words separately in different sections. The following section includes how the data have been transcribed, coded, classified and analyzed. 3.2.1 Transcription and coding The data from the recording were transcribed by the author and the assistants of the research team. If there were disagreements, the tokens would be discussed or.

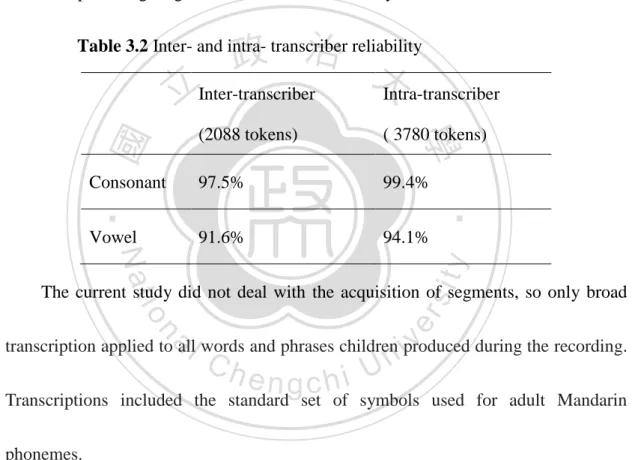

(49) 37. checked by another team member. All of the assistants are native speakers of Taiwan Mandarin and have good training in transcribing children‟s speech. Inter- rater reliability and intra-rater reliability were assessed for the identification of participants‟ consonant and vowel productions in IPA broad transcription. The inter-transcriber and intra-transcriber reliability of the transcription reached a percentage higher than 90% under the study, as shown in Table 3.2. 政 治 大. Table 3.2 Inter- and intra- transcriber reliability. 立Inter-transcriber. Intra-transcriber. Consonant. 97.5%. 99.4%. Vowel. 91.6%. 94.1%. Nat. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. ( 3780 tokens). 學. (2088 tokens). io. n. al. er. The current study did not deal with the acquisition of segments, so only broad. i n U. v. transcription applied to all words and phrases children produced during the recording.. Ch. engchi. Transcriptions included the standard set of symbols used for adult Mandarin phonemes. The utterances of words and phrases would be transcribed into four parts: actual produced words in IPA transcription, tone, possible meaning and number of occurrences. The transcribed examples are shown below in Table 3.3..

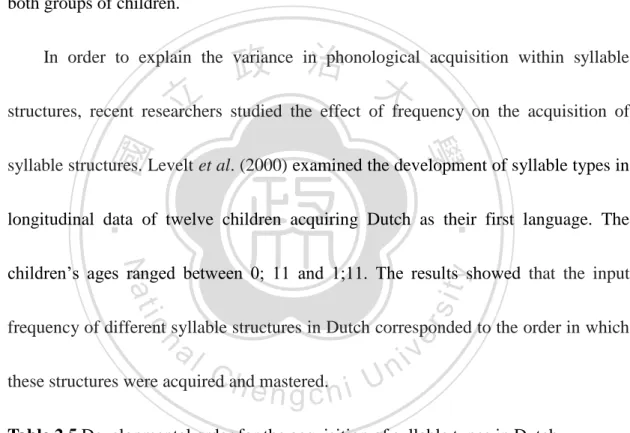

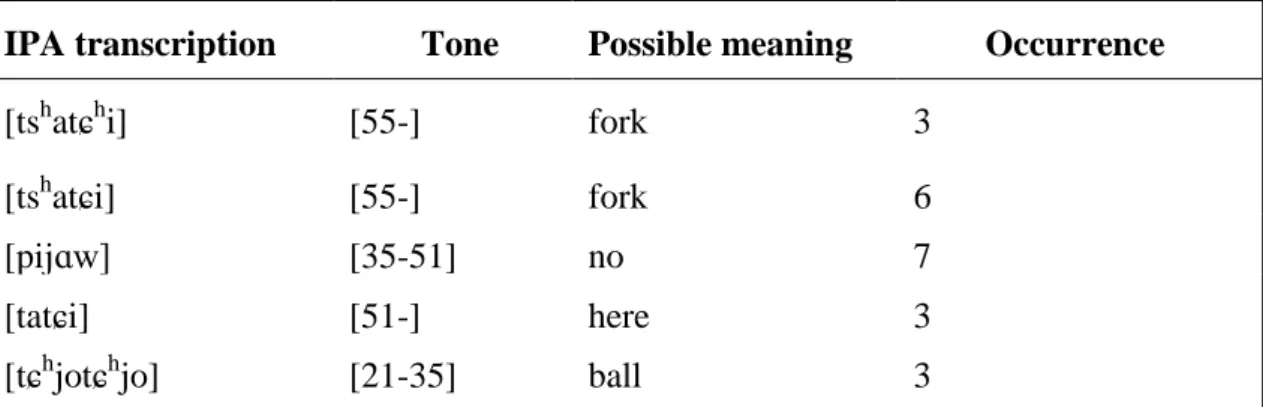

(50) 38. Table 3.3 The sample of coding IPA transcription. Tone. Possible meaning. Occurrence. [tshatɕhi]. [55-]. fork. 3. [tshatɕi]. [55-]. fork. 6. [pijɑw]. [35-51]. no. 7. [tatɕi]. [51-]. here. 3. [21-35]. ball. 3. h. h. [tɕ jotɕ jo]. The first column represented children‟s actual produced words which were. 政 治 大 The tones were coded 立 with [55], [35], [21], [51], representing level tone, rising tone,. transcribed with IPA symbols. The second column marked the tone of produced words.. ‧ 國. 學. falling rising tone, and falling tone respectively. The neutral tone was coded without. ‧. any tone number. The third column marked the possible meanings of each word. sit. y. Nat. children produced which could be inferred by contexts, children‟s gestures, or the. n. al. er. io. repetition of adult‟s speech. If the utterance was meaningless or unable to infer from. Ch. i n U. v. the context, we would leave this column blank. The meaningless token would not be. engchi. included in the study. The last part was the number of occurrence of each word. For example, in the first and second row of the sample, this child produced „fork‟ as [tsha55tɕhi] for 3 times and as [tsha55tɕi] for 6 times. 3.2.2 Criteria for target words The following are some criteria for choosing target words that children produced for analysis. The criteria were adopted from Sosa and Stoel-Gammon (2012). Firstly,.

(51) 39. the sound quality of words must be fair and clear. Whispered speech and overlapping speech of adults would be excluded. Background noise from toys and rustling noise from contact with the sound recorder resulted in blurred and fuzzy sound would also be excluded. Secondly, the meaning of the words must be clear. Words that would only be considered for analysis if a Mandarin gloss could be identified, or if the meaning of words could be inferred by careful examination from the context as well. 政 治 大. as the reaction or repetition of adults‟ speech. For example, if a child pointed at a toy. 立. car and uttered [tɤ55 tɤ55], we would suggest that its intended meaning is „a car‟.. ‧ 國. 學. Thirdly, target words with fewer than three useable tokens, although initially. ‧. transcribed, would not be included in the final analysis.. Nat. io. sit. y. Imitated words would be included in this study, as is often done in this type of. al. er. study (Ferguson & Farwell, 1975; Macrae, 2013; McLeod & Hewett, 2008). Ferguson. n. v i n and Farwell (1975) arguedCthat h ea nhighg cpercentage h i U of what young children say is. imitated and children can imitate words spoken by adults with a considerable separation in time, so it is difficult to exclude imitation from analysis. Imitated words were defined as productions that occurred within 2 seconds of immediately preceding adult utterances that contained the same target words (Sosa & Stoel-Gammon, 2012). Since the study focuses on children acquiring Taiwan Mandarin, English and Taiwanese produced by children, although meaningful, would not be included in the.

數據

相關文件

• When a system undergoes any chemical or physical change, the accompanying change in internal energy, ΔE, is the sum of the heat added to or liberated from the system, q, and the

However, it is worthwhile to point out that they can not inherit all relations between matrix convex and matrix monotone functions, since the class of contin- uous

The evidence presented so far suggests that it is a mistake to believe that middle- aged workers are disadvantaged in the labor market: they have a lower than average unemployment

The relationship between these extra type parameters, and the types to which they are associated, is established by parameteriz- ing the interfaces (Java generics, C#, and Eiffel)

– Students can type the words from the word list into Voki and listen to them. • Any

• One of the main problems of using pre-trained word embeddings is that they are unable to deal with out-of- vocabulary (OOV) words, i.e.. words that have not been seen

• To achieve small expected risk, that is good generalization performance ⇒ both the empirical risk and the ratio between VC dimension and the number of data points have to be small..

A periodic layered medium with unit cells composed of dielectric (e.g., GaAs) and EIT (electromagnetically induced transparency) atomic vapor is suggested and the

![Table 3.4 Phonetic forms and tokens of the word [k h aj55] Target word IPA description Tokens](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/8029461.161336/53.892.191.746.161.340/table-phonetic-forms-tokens-word-target-description-tokens.webp)