Date 2014/Novmeber/25

Type of manuscript: Original article

Manuscript title: Digoxin use may increase the relative risk of acute pancreatitis: a population-based case-control study in Taiwan

Running head: digoxin and acute pancreatitis Authors' full names:

Shih-Wei Lai MD1,2, Cheng-Li Lin MS 3,4, Kuan-Fu Liao DM and MS 5,6

1School of Medicine, China Medical University and 2Department of Family

Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

3Department of Public Health, China Medical University and 4Management Office for

Health Data, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

5Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, China Medical University and

6Department of Internal Medicine, Taichung Tzu Chi General Hospital, Taichung,

Taiwan

Corresponding author: Kuan-Fu Liao, Department of Internal Medicine, Taichung Tzu Chi General Hospital, No.66, Sec. 1, Fongsing Road, Tanzi District, Taichung City, 427, Taiwan

Phone: 886-4-2205-2121; Fax: 886-4-2203-3986 E-mail: kuanfuliao@yahoo.com.tw

ABSTRACT

Objectives. The goal of this study was to evaluate the association between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis in Taiwan. Methods. Utilizing the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program, this case-control study consisted of 6116 subjects aged 20-84 years with a first-attack of acute pancreatitis since 2000 to 2011 as the cases and 24464 randomly selected subjects without acute pancreatitis as the controls. Both cases and controls were matched by sex, age and index year of diagnosing acute pancreatitis. The absence of digoxin prescription was defined as “never use”. Active use of digoxin was defined as subjects who received at least 1 prescription for digoxin within 7 days before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Non-active use of digoxin was defined as subjects who did not receive a prescription within 7 days but at least received 1 prescription for digoxin ≥8 days before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were measured to evaluate the association between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis by a multivariable unconditional logistic regression model. Results. After adjusting for potential

confounding factors, the adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis was 5.29 for subjects with active use of digoxin (95%CI 3.61, 7.73), when compared with subjects with never use of digoxin. The adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis decreased to 1.04 for subjects with non-active use of digoxin (95%CI 0.89, 1.21), but no statistical significance. Conclusions. These data indicate that only persons actively using digoxin may have the high relative odds of acute pancreatitis. Further research or case report is

warranted to evaluate the pathophysiological basis underlying the relationship between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis.

INTRODUCTION

Digoxin is an old agent commonly used for treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure. Traditionally, the clinical features of digoxin toxicity may include extra-cardiac and extra-cardiac effects. Till now, no case has been reported that digoxin use can be associated with acute pancreatitis, but U.S. Food and Drug Administration has reported that since 1997 to 2012, 103 persons (0.2%) had acute pancreatitis among 51856 persons using digoxin with side effects.

Acute pancreatitis is an acute process of the pancreas with varying severity. Its clinical features may be self-limited or may be potentially fatal. Identification of factors potentially related to acute pancreatitis is relatively important from a view of preventive medicine. Although many risk factors have been well proven to be associated with acute pancreatitis, including alcoholism, biliary stone, diabetes mellitus as well as hypertriglyceridemia, there is increasing evidence that numerous routine prescription drugs may be another etiological factor of acute pancreatitis. Approximately 2% of cases with acute pancreatitis may be caused by drugs.

Even without case report about the association between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis, any adverse drug event reported still deserves further exploration. U.S. Food and Drug Administration has reported the events of acute pancreatitis occurring in digoxin users, but the cause-effect relationship remains inconclusive. Due to extensive use of digoxin and the potential fatality of acute pancreatitis, a formal pharmacoepidemiological research based on systematic design is needed before the cause-effect relationship can be established. We therefore conducted a case-control study to further evaluate the relationship between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis. METHODS

Study design and data source

Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. The Taiwan National Health Insurance

Program began in March 1, 1995 and this program has covered nearly 99% of the

whole population living in Taiwan. The details of insurance program have been

described in previous studies. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of

China Medical University and Hospital (CMU-REC-101-012). Identification of cases and controls

In this study, subjects aged 20-84 years with a first-attack of acute pancreatitis were identified as the case group since 2000 to 2011 (based on International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision-Clinical Modification, ICD-9 codes 577.0). For each case

identified in the study, 4 subjects without acute pancreatitis were randomly selected from the same database as the control group. Both groups were matched by sex, age (5-year interval) and index year of diagnosing acute pancreatitis. We defined the index date for each case as the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis. We defined the index date for the control subject as a randomly assigned date within the index year of the corresponding case. To reduce bias, subjects with chronic pancreatitis (ICD-9 codes 577.1) or pancreatic cancer (ICD-9 codes 157) before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis were excluded from the study.

Potential comorbidities studied

Numerous comorbidities before the index date were evaluated for their possible association with acute pancreatitis as follows: alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease (including coronary artery disease, heart failure,

cerebrovascular disease and peripheral atherosclerosis), chronic renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, as well as hypertriglyceridemia. All were diagnosed with ICD-9 codes.

Definition of digoxin use

The elimination half-life of digoxin ranges from 1.5 to 2 days in persons with normal real function and it ranges from 4 to 6 days in persons with impaired renal function. Hence, we used the period of 7 days as a cut-point. The absence of digoxin

prescription was defined as “never use”. Active use of digoxin was defined as

subjects who received at least 1 prescription for digoxin within 7 days before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis or the corresponding date for the control subjects. Non-active use of digoxin was defined as subjects who did not receive a prescription within 7 days but at least received 1 prescription for digoxin ≥8 days before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis or the corresponding date for the control subjects. Statistical analysis

We compared the differences in demographic status, digoxin use and comorbidities between the acute pancreatitis case group and the control group by using Chi-square test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. The variables found significant in an univariable unconditional logistic regression model were then analyzed in a multivariable unconditional logistic regression model to measure the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for acute pancreatitis risk. The further analysis was stratified by presence of chronic renal disease or not to evaluate the interaction effect of active use of digoxin on acute pancreatitis risk. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed with the SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of the study population

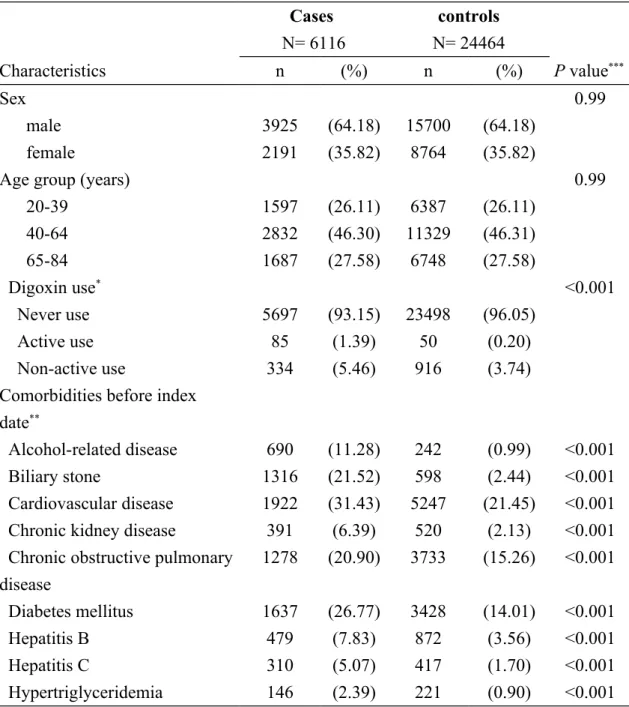

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of digoxin use and comorbidities among the study population. There were 6116 cases with acute pancreatitis and 24464

control subjects. When compared with the control subjects, the cases were more likely to have alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hypertriglyceridemia (P <0.001 for all). In total, 419 of 6116 cases had ever used digoxin (6.85%) and 966 of 24464 control subjects had ever used digoxin (3.95%), with statistical significance (P <0.001). The mean ages (standard deviation) were 52.94 (16.46) years in the cases and 52.47 (16.62) years in the control subjects, without statistical significance (P =0.05 for t test)

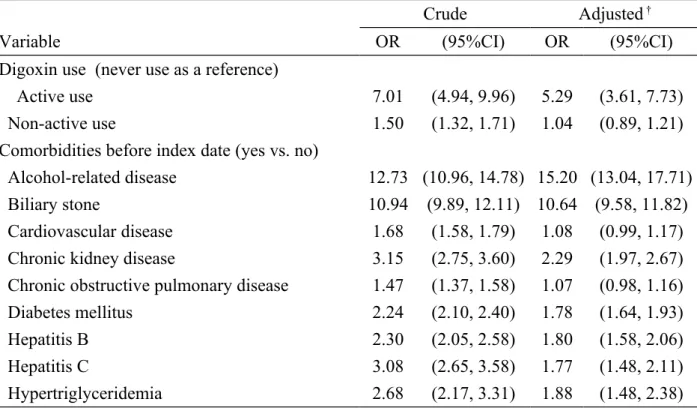

Odds ratio of acute pancreatitis associated with digoxin use

Table 2 presents the OR of acute pancreatitis associated with digoxin use and comorbidities. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, the adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis was 5.29 for subjects with active use of digoxin (95%CI 3.61, 7.73), when compared with subjects with never use of digoxin. The adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis decreased to 1.04 for subjects with non-active use of digoxin (95%CI 0.89, 1.21), but no statistical significance.

Interaction between active use of digoxin and chronic kidney disease on acute pancreatitis risk

Table 3 presents the interaction effect on risk of acute pancreatitis between active use of digoxin and chronic kidney disease. In further analysis, as a reference of subjects without digoxin use and without chronic kidney disease, the OR was 5.06 in those with active use of digoxin and without chronic kidney disease (95% CI 3.37, 7.59). The OR increased to 20.13 in those with active use of digoxin and with chronic kidney disease (95% CI 5.78, 70.15). This highlights that there is a strong impact on risk of acute pancreatitis in those with active use of digoxin and comorbid with chronic kidney disease (P value for interaction <0.001).

of digoxin

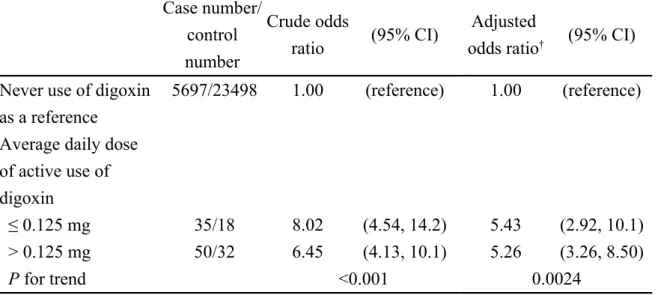

We further conducted an analysis on the dose-response effect among those with

active use of digoxin. The average daily dose of digoxin was calculated by using the

total prescribed dose divided by total number of days supplied. Because the

commonly used form of digoxin is 0.25 mg per tablet in Taiwan, we used 0.125 mg as

a cut-point. We classified study subjects into two subgroups: high dose with average

daily dose of digoxin use > 0.125 mg and low dose with average daily dose of digoxin

use 0.125 mg. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, both subgroups

were associated with increased odds of acute pancreatitis (OR 5.26, 95% CI 3.26, 8.50

for high dose and OR 5.43, 95% CI 2.92, 10.1 for low dose) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Digoxin is an old agent commonly used for treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure, not for treatment of gastro-intestinal diseases. Before this study, no other study evaluates whether patients with acute pancreatitis have higher proportion of using digoxin or not. In this study, 419 of 6116 acute pancreatitis cases had ever used digoxin (6.85%) and 966 of 24464 control subjects had ever used digoxin (3.95%), with statistical significance (P <0.001). After adjusting for potential confounding factors, we observed that active use of digoxin was associated with increased odds of acute pancreatitis (OR 5.29, 95%CI 3.61, 7.73), but no association was detected between non-active use of digoxin and acute pancreatitis. These findings indicate that only persons actively using digoxin may have the high relative odds of acute

odds.

About 70% of digoxin is eliminated by renal route and the elimination half-life of digoxin depends on the renal function. That is why we included chronic renal disease as a covariable for adjustment. We further estimated the interaction effect on risk of acute pancreatitis between active use of digoxin and chronic kidney disease. We observed that as a reference of persons without digoxin use and without chronic kidney disease, the OR was 20.13 in those with active use of digoxin and with chronic kidney disease (95% CI 5.78, 70.15). This finding means that the elimination half-life of digoxin may be prolonged in persons with chronic kidney disease. The serum concentration of digoxin further increases. Therefore, the risk of digoxin-associated acute pancreatitis may markedly enhance. Careful attention must be paid to persons with chronic kidney disease about acute pancreatitis risk when prescribing digoxin.

Although the pathophysiological basis underlying the relationship between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis cannot be completely elucidated in this observational study, even after searching thoroughly, no case report or no relevant literature about the possible cause-effect relationship between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis has been published. We cannot compare our data with each other. One in-vivo study revealed that digoxin can induce hypomagnesemia and low serum magnesium level can further lead to increased glycosaminoglycan level in the pancreas. All these changes can be associated with chronic calcific pancreatitis. In spite of no direct evidence, based on the hint of the above study, we make a plausible presumption that acute and direct effect of digoxin on the pancreas may be associated with acute pancreatitis. In addition, a drug-drug interaction should also be considered. Digoxin seems to have a significant potential for interaction with several medications concomitantly used. Therefore, a probable drug-drug interaction may be associated with acute pancreatitis.

Thereafter, more data are required to understand this issue.

Some limitations need to be taken into account when interpreting our data. First, whether persons actually took digoxin or not could not be proven in this study due to the natural limitation of the database. We used prescriptions for digoxin instead of digoxin administration. We also observed that no matter average daily dose of active use of digoxin was > 0.125 mg or 0.125 mg, the relative odds of acute pancreatitis was significantly high. It means that active use of digoxin use is substantially associated with acute pancreatitis, independent of dose-effect. Second, some covariables such as behavior risk factors (alcohol consumption and smoking) and socioeconomic factor were not recorded due to the natural limitation of the database. We could not include socioeconomic factor as a covariable for adjustment, but we included alcohol-related disease as an alternative covariable instead of alcohol consumption and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an alternative covariable instead of smoking for adjustment. Third, although we included cardiovascular disease as a covariable for adjustment, the clinical indications for digoxin use were not recorded due to the natural limitation of the database. We cannot make sure whether or not the indications for digoxin use are associated with acute pancreatitis. A further research is needed to clarify the relationship between the indications for digoxin use and acute pancreatitis. Forth, in addition to traditional risk factors such as alcoholism, biliary stone, diabetes mellitus as well as hypertriglyceridemia, we found that chronic renal disease was associated with acute pancreatitis in this study, which is partially compatible with Hou and colleagues’ study that patients on long-term

hemodialysis have a higher risk of acute pancreatitis, as compared with the general population (adjusted hazard ratio 3.44, 95%CI 2.5–4.7). This indicates a future research direction about the relationship between chronic renal disease and acute

pancreatitis. Nevertheless, we analyzed a well-organized database that has

contributed greatly to the literature in addressing major epidemiological researches in the Taiwan‘s population. The topic is novel and interesting in that it attempts to clarify the issue of the relationship between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis for which little previous literature has been published. The statistical methodology is correct and the conclusions appear impressive. This present study is clinically relevant and may trigger future scientific research on toxicity of digoxin.

In conclusion, only persons actively using digoxin may have the high relative odds of acute pancreatitis. However, the available literature is insufficient and further research or case report is warranted to evaluate the pathophysiological basis underlying the relationship between digoxin use and acute pancreatitis.

Funding

This study was supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW103-TDU-B-212-113002). The funding agency did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Specific author contributions

Shih-Wei Lai: (1) substantial contributions to the conception of this article; (2) planned and conducted the study; (3) initiated the draft of the article and critically revised the article.

Cheng-Li Lin: (1) conducted data analysis; (2) critically revised the article. Kuan-Fu Liao: (1) planned and conducted the study; (2) participated in data interpretation; (3) critically revised the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement None to declare.

REFERENCES

[1] Bauman JL, Didomenico RJ, Galanter WL. Mechanisms, manifestations, and management of digoxin toxicity in the modern era. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2006;6:77-86.

[2] Ehle M, Patel C, Giugliano RP. Digoxin: clinical highlights: a review of digoxin and its use in contemporary medicine. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2011;10:93-8.

[3] eHealthMe study from FDA and social media reports. Review: could digoxin cause acute pancreatitis? http://www.ehealthme.com/print/ds14956490. [cited in 2014 October].

[4] Chang MC, Su CH, Sun MS, Huang SC, Chiu CT, Chen MC, et al. Etiology of acute pancreatitis--a multi-center study in Taiwan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1655-7.

[5] Chen CH, Dai CY, Hou NJ, Chen SC, Chuang WL, Yu ML. Etiology, severity and recurrence of acute pancreatitis in southern taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:550-5.

[6] Lai SW, Muo CH, Liao KF, Sung FC, Chen PC. Risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes and risk reduction on anti-diabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1697-704.

[7] Balani AR, Grendell JH. Drug-induced pancreatitis : incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf. 2008;31:823-37.

[8] Nitsche CJ, Jamieson N, Lerch MM, Mayerle JV. Drug induced pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:143-55.

[9] Ksiadzyna D. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis related to medications commonly used in gastroenterology. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:20-5.

[10] National Health Insurance Research Database. Taiwan. http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/Backgroundhtml. [cited in 2014 October].

[11] Lai SW, Liao KF, Liao CC, Muo CH, Liu CS, Sung FC. Polypharmacy correlates with increased risk for hip fracture in the elderly: a population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89:295-9. [12] Liao KF, Lai SW, Li CI, Chen WC. Diabetes mellitus correlates with increased risk of pancreatic cancer: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:709-13.

[13] Iisalo E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of digoxin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1977;2:1-16.

[14] Kumar RA, Kurup PA. Serum and tissue glycoconjugates, digoxin and magnesium levels in chronic calcific pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:230-3.

[15] Hou SW, Lee YK, Hsu CY, Lee CC, Su YC. Increased risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with chronic hemodialysis: a 4-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71801.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of cases with acute pancreatitis and controls Cases N= 6116 controls N= 24464 Characteristics n (%) n (%) P value*** Sex 0.99 male 3925 (64.18) 15700 (64.18) female 2191 (35.82) 8764 (35.82)

Age group (years) 0.99

20-39 1597 (26.11) 6387 (26.11) 40-64 2832 (46.30) 11329 (46.31) 65-84 1687 (27.58) 6748 (27.58) Digoxin use* <0.001 Never use 5697 (93.15) 23498 (96.05) Active use 85 (1.39) 50 (0.20) Non-active use 334 (5.46) 916 (3.74)

Comorbidities before index date**

Alcohol-related disease 690 (11.28) 242 (0.99) <0.001

Biliary stone 1316 (21.52) 598 (2.44) <0.001

Cardiovascular disease 1922 (31.43) 5247 (21.45) <0.001 Chronic kidney disease 391 (6.39) 520 (2.13) <0.001 Chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease 1278 (20.90) 3733 (15.26) <0.001 Diabetes mellitus 1637 (26.77) 3428 (14.01) <0.001 Hepatitis B 479 (7.83) 872 (3.56) <0.001 Hepatitis C 310 (5.07) 417 (1.70) <0.001 Hypertriglyceridemia 146 (2.39) 221 (0.90) <0.001

Data are presented as the number of subjects in each group, with percentages given in parentheses.

*Active use of digoxin was defined as subjects who received at least 1 prescription for

digoxin within 7 days before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis or the

corresponding date for controls. Non-active use of digoxin was defined as subjects who did not receive a prescription within 7 days but at least 1 prescription for digoxin ≥8 days before the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis or the corresponding date for controls.

***Chi-square test comparing subjects with and without acute pancreatitis

Table 2. Crude and adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of acute pancreatitis associated with digoxin use and other variables

Crude Adjusted †

Variable OR (95%CI) OR (95%CI)

Digoxin use (never use as a reference)

Active use 7.01 (4.94, 9.96) 5.29 (3.61, 7.73)

Non-active use 1.50 (1.32, 1.71) 1.04 (0.89, 1.21)

Comorbidities before index date (yes vs. no)

Alcohol-related disease 12.73 (10.96, 14.78) 15.20 (13.04, 17.71)

Biliary stone 10.94 (9.89, 12.11) 10.64 (9.58, 11.82)

Cardiovascular disease 1.68 (1.58, 1.79) 1.08 (0.99, 1.17)

Chronic kidney disease 3.15 (2.75, 3.60) 2.29 (1.97, 2.67)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 1.47 (1.37, 1.58) 1.07 (0.98, 1.16)

Diabetes mellitus 2.24 (2.10, 2.40) 1.78 (1.64, 1.93)

Hepatitis B 2.30 (2.05, 2.58) 1.80 (1.58, 2.06)

Hepatitis C 3.08 (2.65, 3.58) 1.77 (1.48, 2.11)

Hypertriglyceridemia 2.68 (2.17, 3.31) 1.88 (1.48, 2.38)

†Adjusting for alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney

disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hypertriglyceridemia

Table 3. Interaction effect on acute pancreatitis between active use of digoxin and chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease

Never use of digoxin Active use of digoxin

Case number/ control number

OR(95% CI)† Case

number/ control number OR (95% CI)† No 5373/23072 As a reference 66/47 5.06(3.37, 7.59) Yes 324/426 2.47(2.08, 2.91) 19/3 20.13(5.78, 70.15)

†Adjusting for alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hypertriglyceridemia.

The interaction between active use of digoxin and presence of chronic kidney disease was significant (P value for interaction <0.001).

Table 4. Crude and adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of acute pancreatitis associated with average daily dose of active use of digoxin

Case number/ control number Crude odds ratio (95% CI) Adjusted

odds ratio† (95% CI)

Never use of digoxin as a reference

5697/23498 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference)

Average daily dose of active use of digoxin

≤ 0.125 mg 35/18 8.02 (4.54, 14.2) 5.43 (2.92, 10.1)

> 0.125 mg 50/32 6.45 (4.13, 10.1) 5.26 (3.26, 8.50)

P for trend <0.001 0.0024

†Adjusting for alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease, chronic

kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hypertriglyceridemia