Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 187

Journal of Research in Education Sciences 2018, 63(2), 187-218

doi:10.6209/JORIES.201806_63(2).0008

Models of Transformative Learning Among

Family Caregivers of People With Dementia:

Positive Experience Approaches

Chia-Ming Yen

Medical Center of Aging Research, China Medical University Hospital

Abstract

In contrast to the general assumptions that people with dementia are a physical, psychological, and financial burden, recent studies have demonstrated that family caregivers can benefit and experience personal growth when caring for a family member with dementia. This study investigates the transformation of family caregivers when caring for a family member with dementia. This study first examined the negative experiences of family caregivers of people with dementia and then explored the triggers that helped change their experiences from negative to positive during caregiving. In-depth interviews were conducted with 18 participants. The participants were recruited from two local care associations and one medical centre in central and southern Taiwan. Each interview was audio-recorded and data were transcribed verbatim. A thematic analysis was performed to analyze the themes and subthemes related to the triggers. The findings revealed that optimistic characteristics, mutuality, spirituality, and coping abilities and skills are important triggers for developing a positive caregiving experience model. This study is intended to help family caregivers, who may often feel pessimistic, to have positive daily caregiving experiences. Moreover, the study provides government long-term care policymakers, scholars, and healthcare professionals and practitioners with a more comprehensive understanding of the caregiving challenges and needs of family caregivers.

Keywords: family caregivers of people with dementia, positive caregiving experiences, transformative learning

Corresponding Author: Chia-Ming Yen, E-mail: ayen1001@gmail.com

188 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

Introduction

In 2016, 3,051,893 persons in Taiwan were aged 65 years and older, and 243,430 persons were estimated as having dementia. That is, one in every 13 persons aged 65 years and older and one in every 5 persons aged 80 years and older received a diagnosis of dementia (Taiwan Alzheimer’s Disease Association, 2017). Furthermore, 9.9 million new cases of dementia are present globally (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016). A total of 47 million persons worldwide have dementia, more than the population of Spain. This number is projected to increase to more than 131 million by 2050 as populations age (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016). The incidence of dementia is rapidly increasing both in Taiwan and worldwide. Unlike other diseases, dementia leads to a progressive decline in memory and other cognitive functions, causing increased dependence in daily activities. The experiences of family caregivers of people with dementia show wide individual variations because every caregiver and care recipient is different. In particular, numerous studies have reported the negative experiences of family caregivers (Gainey & Payne, 2006; Wang, Shyu, Chen, & Yang, 2010). The most significant negative effects reported by caregivers are commonly referred to as caregiver: (a) psychological burden (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003); (b) social isolation (Chiu, Huang, & Shyu, 2004); (c) health decline (Pallant & Reid, 2014); and (d) increased cost of health care and other resources (Arno, Levine, & Memmott, 1999). In addition, adults who look after their parents with dementia encounter difficulties in reconciling work and family caregiving (Wang, et al., 2010; Wang, Shyu, Tsai, Yang, & Yao, 2013). The factors that contribute to caregiving burden have been reported to be associated with cultural beliefs; caregiver personality; perceived resources; and feelings of situational overload, resentment, fatigue, and relational deprivation (Huang et al., 2015; Huang, Lee, Liao, Wang, & Lai, 2012).

Past literature also has identified important aspects of culture impact upon caregiver living with dementia. In Chinese customs, dementia is sometimes attributed to normal aging and regression to childhood but also is associated with stigma (Liu, Hinton, Tran, Hinton, & Barker, 2008). This stigmatisation may mean families do not seek support as they fear the shame associated with dementia (Chan & O’Connor, 2008). In this study, cultural norms cannot be ignored as the notion of Confucian traditions may possible play a significant role ideologically among the participants who are adult children, in their 40s, 50s and 60s, caring elder parents may possible consider as his or her obligation in the family, for the son in particular. The Confucian traditions of respect for the elderly and of filial piety, as well as the more collectivist orientation of East Asian culture would be

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 189

especially distinct from individualism values among Western caregivers. Moral obligations of filial responsibility (e.g., filial piety) are an important part of identity in many traditional Asian cultures (Holroyd & Mackenzie, 1995) and may provide a sense of role fulfillment, pride and self-worth (Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006). However, there are conflicting findings. The cultural value accorded to caregiving may ultimately harm wellbeing where caregivers struggle to fulfill high cultural expectations with diminished resources. The importance of the cultural expectedness of care provision (as reflected in filial responsibility) may also be overstated (Funk, Chappell, & Liu, 2013, p. 81). In Funk et al.’s (2013, pp. 89-90) study were interviewed and the results showed stronger filial expectancy was associated with worse self-rated health, but stronger filial piety was associated with higher perceived well-being. Conflict between traditional obligations and the capacity to provide care may emerge among caregivers in Taiwan. Previous study has suggested that differences in cultural beliefs may interfere with the caregiving process, including caregivers’ appraisal of stress, coping strategies, and social support. It is worth examining the experience of caregiving in an Asian country like Taiwan.

Studies have increasingly reported the positive effects of care from family caregivers who perceive themselves as uplifted because they actively work to promote the positive aspects of care (Donovan & Corcoran, 2010; Farran, 1997; Hollis-Sawyer, 2003; Kramer, 1997). These gains, such as valuing positive aspects (Farran, Keane-Hagerty, Salloway, Kupferer, & Wilken, 1991), significant gratification (Folkman, 1997; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003), and reciprocal relationships (Donovan & Corcoran, 2010; Huang, 2009; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003), have been reported in caregivers and care recipients. Studies have indicated that different aspects may yield individual positive effects during care for a family member with dementia. However, few studies have comprehensively reported the positive caregiving experiences of family caregivers of patients with dementia. Therefore, this study explored and examined the negative experiences of these caregivers as well as determined how these negative experiences can be transformed into positive ones.

This study used the transformative learning process to examine the changes from negative to positive caregiving experiences in family caregivers. Positive caregiving changes can be the results of 2 factors: phases of transformation and the irreversible characteristics of Alzheimer disease. Transformative learning theory facilitates the interpretation of how family caregivers question, examine, validate, and develop their perspectives while caring for a family member with dementia. On the other hand, the perceived experiences of family caregivers may possibly change in accordance with the process of dementia at different stages. Due to the individuals with dementia, because of special pathological changes in cognitive decline, there are several kinds of symptoms

190 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

(e.g., behavioral problems and functional impairment). These are the reasons why taking care of dementia people are challenging. To interpret changes in family caregivers, Mezirow’s transformative learning theory was adopted because it examines how adults interpret their life experiences (Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner, 2007, p. 132). Mezirow (2003, p. 58). explains that “transformative learning is learning that transforms problematic frames of reference – sets of fixed assumptions and expectations (habits of mind, meaning perspectives, mindsets) – to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, reflective, and emotionally able to change” According to Mezirow (1991), the process of personal transformation, within awareness, often involves 11 phases:

1. A disorienting dilemma;

2. Self-examination, with feelings of guilt or shame;

3. A critical assessment of epistemic, sociocultural, or psychic assumptions;

4. Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change;

5. Exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and actions; 6. Planning a course of action;

7. Acquisition knowledge and skills to implement one’s plans; 8. Provisionally trying new roles;

9. Renegotiating old and new relationships1;

10. Building competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships; and

11. A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s new perspective. The first phase can present in different forms, such as unexpected distress, a life crisis, or an experience that deviates from expected or assumed circumstances. Once individuals understand the new phase, they can move forward to phases 5 and 7, where the transformation process is reaffirmed and they seek new knowledge, skills, and actions. In phases 8-11, individuals either accept the new role or relationship or reject and redesign a new role or relationship. Mezirow states “transformation experience may manifest in various forms and that is not necessary for individuals to experience all phases or do so in a set order” (Kitchenham, 2008, p. 113).

In this study, the experiences of some family caregivers changed from negative to positive throughout the transformative learning process. The association of the transformative learning

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 191

process with triggers2 was explored and examined through the responses of the study participants. The research questions were as follow: (a) What are the negative experiences of family caregivers of patients with dementia? (b) What are the significant triggers that result in positive caring experiences for family caregivers of people with dementia? (c) How do the experiences of family caregivers of people with dementia become positive?

Methods

Participants

The participants were recruited by the staff (e.g., social workers, research assistants of neurologists, and administrative staff) of 3 care and health organizations in central and southern Taiwan. Caregivers were recruited if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) self-identifying as the primary caregiver in the house; (b) living with the care recipient (a parent, parent-in-law, grandparent, or spouse with dementia); (c) self-identifying as experiencing both the negative and positive aspects of caregiving or being recruited because social workers or neurologists and the researchers perceived them as having had these experiences3.

Data Collection

A total of 18 participants were recruited: 10 from care associations that provide support services for family caregivers of people with dementia in central and southern Taiwan and 8 from the outpatient department of the Division of Neurology in a teaching hospital in southern Taiwan. The procedure for recruiting interview participants were through the following three organizations, the Association of Republic of China Dementia Family Caregivers (中華民國失智症家庭照顧者協會), Division of Neurology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Kaohsiung (高雄長庚紀念醫院神經內科) and Kaohsiung City Smart-Action Neurodegeneration Association (高雄市聰動成長協會). The recruitment for the participants was via the staff from the above three organizations. The author surfed the information on the internet about the associations in related to dementia family caregivers. Then the author made a phone or email contact to the organization and explained my purposes and the intention of my study. Meanwhile the author asked for the possibility to assist for recruiting

2 Triggers are the elements or factors that enable participants to have positive caregiving experiences. In brief,

triggers can be considered driving forces that have significant effects on participants.

3 Family caregivers of people with dementia who have had both negative and positive experiences during caregiving,

regardless of gender, age, or caregiving duration. These caregivers can realize the relevance and rewards of caregiving, despite its challenges and problems.

192 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

participants in this study. Selected participants were received a letter, a consent form and handouts. This study was based on in-depth interviews. A list of open-ended interview questions was used to give family caregivers the opportunity to tell their stories without feeling that the interviewer was imposing a structure on them. Initially it was designed to interview twice. However due to the availability of time of mostly participants, in the end there were 6 out of 18 participants were conducted interviews twice. All of them are from the same association. The others remained as one interview. Despite the number of interviews is vary among the participants, it does not affect significantly the quality of responses since each participant was given the same interview schedule and asked “Whether there is something else you want to add or talk more about” before the close of interview.

The author conducted the interview process from February to March 2014, with continuous reviews of notes, tapes, and transcriptions. Moreover, the author followed up with the participants through telephone calls for response clarification and elaboration. The original interview questions were modified based on the outcomes of a pilot study that was conducted with 2 family caregivers. The interviews were held in quiet venues agreed upon by both interviewer and interviewee. All interviews were tape-recorded and began with reviewing the consent form. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Cheng Kung University. In accordance with the IRB requirements, participation was informed and voluntary, and every possible effort was made to ensure data confidentiality.

Data Analysis

A thematic data analysis was performed. In this study, each theme represents a specific aspect of positive effects and self-transformation through the caregiving processes, as reported by the participants. Thematic analysis involves coding themes and subthemes (Kvale, 1996). Common themes were found among all participants based on their answers to the interview questions, such as the positive effects of caregiving. A data grid was created to develop the categories. The authors followed a continuous reflection process as interviews were completed. A broad range of themes regarding participants’ experiences were adopted using inductive reasoning and interpreting through individual perspectives. The various representations of these experiences were recorded to develop an essential structure. The analysis was not aimed at proving that all family caregivers of people with dementia had similar experiences. Instead, it aimed to acknowledge, understand, and appreciate the diverse and similar experiences of these caregivers. Hence, this study avoided making generalizations about the participants. The exclusion factors were cautiously decided so that the

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 193

caregivers’ experiences would be presented as completely and fairly as possible.

Reliability and Validity

In this study, member check was used for quality review and verification. The participants were asked to review the transcripts prepared by the first author for accuracy, including any preliminary analysis of their responses with an emphasis on aspects interpreted as transformative learning. Data were considered reliable and valid in terms of both description and interpretation.

Table 1 presents the interview questions; follow-up questions were asked in case the participants had crucial concerns.

Table 1

Interview Questions

Q1: What have made you feel the most frustrated in terms of caring a family with dementia? Is it physical, mental or both? Have you ever had negative thoughts?

Q2: How do you adjust yourself while facing the cognitive decline of family with dementia? Q3: How do you deal with unpleasant feelings during the process of caring?

Q4: How do you feel about yourself in terms of adoptability and the ability to deal while encountering problem during the process of caring?

Q5: How do you describe your interaction (relationship) with care recipient?

Q6: Has the relationship between the care recipient and you changed during the process of caring? In what ways how it has been changed?

Q7: Do you think you are someone who is strong, optimistic and tend to bounce back after hardship? Q8: Have you been supported or helped by other family members? In what ways you have generally

received her/ his/ their supports?

Q9: What is your religion? Have you started to join a religion after becoming the family caregiver? Q10: Have you changed from the process of caring a family with dementia? What kinds of changes are

they?

Results

Demographic Data

In this study, 18 participants were recruited; patient characteristics are reported in Table 2. In total 18 participants were recruited – and 6 were males and 12 females. Twelve out of 18 are between 30 and 50 years old; six out of the 18 are aged 60 and above. There are 8 out of 18 participants who are adult children to look after his or her parent with dementia. There are 8 spouses

194 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

Table 2

Participant Demographics

The participants Gender Age The relationship between caregiver/ care recipient The length of caregiving time A1 F 55 Daughter/Mother 6-7 years A2 F 37 Daughter-in-law/Father-in-law 1 year B1 M 49 Son/Mother 4-5 years B2 M 68 Son/Mother 10 years

A3 (mother of B3) F 71 Wife/Husband 24 years

B3 (son of A3) M 40 Son/Mother

A4 F 65 Wife/Husband 1-2 years A5 F 73 Wife/Husband 3-4 years B4 M 50 Son/Mother 5-6 years B5 M 75 Husband/Wife 2-3 years B6 M 72 Husband/Wife 5-6 years A6 F 50 Daughter/Mother 7-8 years A7 F 50 Daughter/Mother 6-7 years A8 F 50 Wife/Husband 6-7 years A9 F 30 Granddaughter/Grandmother 5-6 years

A10 F 55 Wife/Husband 5-5 years

A11 F 40 Daughter/Mother 2-3 years

A12 F 50 Wife/Husband 5-6 years

Note. “A” means female family caregiver; “B” means male family caregiver.

in which 6 are wife caregivers and 2 are husband caregivers. The longest duration of care giving is about 25 years while the shortest is about a year.

Although the care recipients are not interviewed and nor do they are the main focus in this study, Table 3 shows the types of information about care recipient may help to gain a more complete picture about the process of caregiving.

Negative Experiences

According to the study participants, negative experiences are mainly caused by “psychological burden,” “family tension and chaos,” “lack of knowledge about dementia,” “health decline,” and “economic concerns.” Table 4 shows a data grid was created to group the categories from negative experiences.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 195

Table 3

Types of Information of Care Recipients

Caregiver Gender of care recipient The date of confirmation of dementia diagnosis Age of care recipient First visit of MMSE First visit of CDR The most recent date of medical visit Latest MMSE Latest CDR Types of dementia A1 F 2007 75 * * * * * Alzheimer A2 M 2013 79 * * * * * Alzheimer B1 F 80 * * * * * Alzheimer B2 F 2009 88 * * * * * * A3 M About 2002 About 80 * * * * * Vascular Alzheimer B3 M About 2002 About 80 * * * * * Vascular Alzheimer A4 M 2012 * * * * * * Dementia/ Lewy Bodies A5 M 2010 76 20 0.5 2014/01/14 24 0.5 Alzheimer B4 F 2008 74 17 0.5 2014/04/21 14 1 Alzheimer B5 F 2011 75 23 0.5 2014/04/28 19 0.5 Alzheimer B6 F 2008 68 15 1 2014/04/28 08 1 Alzheimer A6 F 2006 79 18 0.5 2014/04/14 17 0.5 Alzheimer A7 F 2007 74 18 0.5 2014/04/15 15 1 Alzheimer A8 M 2007 82 28 0.5 2014/04/14 26 0.5 Alzheimer A9 F 2008 74 * * * * * Alzheimer A10 M 2009 64 * * * * * * A11 F 2011 74 14 1 2014/04/03 11 1 Alzheimer A12 M 2008 57 * * * * * *

Note. *Due to family caregivers may not be able to acknowledge with the medical information of care recipient. Certain amounts of information are unavailable here.

Psychological Burden

Ten of the 18 participants reported experiencing a psychological burden more so than a physical one. This resulted from the problem behaviors of patients with dementia, such as repeating language, using offensive and aggressive words, being suspicious of even the smallest events, low self-esteem, and potential physical violence. Participant B4 (age, 40 years) initially reported that he and his family could not understand the behaviors and language their mother used with them. These problem behaviors occurred repeatedly:

196 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

Table 4

Data Grid 1: The Negative Experiences

Themes Sub-themes Titles

Negative experiences

Problem behaviors of dementia patients

Repeating language, using offensive and aggressive words, being suspicious of even the smallest events, low self-esteem, and potential physical violence

Different stages of dementia

The sorts of hardship vary because different symptoms are manifest during different stages of dementia

Psychological burden

No burden There is no burden during the process of caregiving Family chaos and

tension

Lack of deep knowledge about dementia disease. Mainly lack of knowledge and coping skills from psychiatric problem behaviors of dementia patient

Caregivers self-reported that their health was not good but this was often ascribed to neurotic disorders

Participants’ old disease became worse after caregiving Health condition

of caregiver

Health condition are self-reported by

caregivers

There is no relationship between the condition of my health and caregiving

Families’ economic condition is quite good

Our family’s economic position relies on a pension or adult children Family economic condition Family economic condition are self-reported by caregivers

Our family’s economic condition is not good

She has become very suspicious and has sudden emotional outbursts. Also, the language she uses hurts. She has not yet caused physical harm. What she says to us tends to come from her own imagination.

In addition, the participants reported different challenges at different stages. A mother and son have cared for a family with dementia (relationships: spouse and father, respectively) for more than 25 years. The mother reported,

The stresses are both mental and physical. The past 10 years have been the hardest time of the entire caring process. He has been completely dependent on us. (A3, age, 71 years)

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 197

In the early stage, it was mental suffering, and then it was physical suffering. It really depends on the caregiver and care recipient; individuals may have different experiences. (B3, age, 40 years)

Family Tension and Chaos Due to Lacking of Knowledge About Dementia

In this study, family tension and chaos was mainly caused by the psychiatric behaviors of patients with dementia. Eleven participants reported that “they did not know what dementia was”; 7 reported they had “heard about dementia but had limited knowledge about it.” Three reported that after a certain length of time, they were able to understand the disease. The father of participant B3 was diagnosed as having vascular dementia; however, it had not been confirmed until 12 years previously. His father has had dementia for more than 25 years. He recalled the long, chaotic journey the family has endured:

Initially, it was a disaster, filled with chaos. It was difficult to confirm his diagnosis a decade previously. We thought he was aging normally. I didn’t know what had happened to him. I thought he was creating all kinds of trouble for me. (B3, age, 40 years)

The mother continued, her heart still seeming to flutter with fear:

One morning, I returned from buying breakfast and saw my husband beating my son with his stick. There was a period – about 10 years – when everything was blank. The whole family was miserable. Our neighbours did not know what had happened to us. We said nothing to them. For about 12 years, we could not confirm whether he was ill with dementia. Nobody could confirm this for us. (A3, age, 71 years)

A lack of knowledge and skill can cause negative effects on dementia cases in terms of medical treatment.

Health Decline

Twelve participants reported that their health had declined since they had become primary caregivers. Three participants reported deteriorating health mainly because of the stress of caring for a relative with dementia. In the past year, participant A4 has experienced pain in her knee and hip joints. Her husband lost his way home several times, worsening her health. However, health problems such as these tend to be “neurotic disorders” and are not actually severe. Participant A2

198 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

(age, 37 years) reported the following:

I feel very tired. I suppose it is caused by my psychological burden. I used to be able to work for long hours and sleep for 4 hours on average. However, now I feel sleepy at erratic hours.

Economic Concerns

Seventeen participants reported that their families had no economic concerns. Most participants (adult children/spouse) in this study were either still employed, managing their own businesses, or relying on their own pensions. Most of them reported that their families were in stable economic condition, except for one young caregiver (participant A9) who looks after her paternal grandmother and is financially supported by other family members.

We are not economically stable. I rely on my husband’s income. I’ve told my father and aunty about our family’s economic strain, so they give me some money every month. However, we still have [to pay the] mortgages! (A9, age, 30 years)

Triggers that Result in Positive Caregiving Experiences Among

Family Caregivers

Table 5 shows the data grid was created by compiling all major themes and relevant quotes into tables to ensure the cohesiveness and distinctions from responses of triggers that result in positive experience.

Optimistic Characteristics

The participants were asked to report whether they were optimistic. Nine participants stated “I am optimistic,” and 3stated “I am not optimistic.” Another 4 participants expressed other ideas.

I Am Optimistic

Participant B6 (age, 72 years) said,

I am optimistic. I used to have a bad temper, but not now. I feel guilty about her. My children cannot look after her. She is my wife; I have to say she is important to me. Now we do everything together. Sometimes, I will nag her when she leaves waste on her trousers.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 199

Table 5

Data Grid 2: Triggers that Result in Positive Experiences

Themes Sub-themes Titles

I am optimistic. Participants with optimistic characteristics tend to face challenges and problems with positive attitudes from the process of caregiving

Optimism

I used to be pessimistic/timid/soft but now I am more optimistic/proactive/stronger. Participants are not optimistic but they become a positive caregiver

Optimistic characteristics

Duty of adult children I am not that strong, but taking care of elderly parents is a child’s duty

An improved relationship with the patients with dementia Relationship changed

positively A strengthened relationship between the caregiver and other family members

Mutuality

Caregiver is more distant

with care recipient Caregiver is more distant with care recipient

Religion has helped me enhance the caregiving process Religion I believe in the concept of karmic rewards, samsara, and the

cycle of death and rebirth

I do not follow a particular religion, but I believe in the existence of God

Traditional worship as

spiritual process My spiritual strength is enhanced by worshiping my ancestors

Spirituality

No religion is related to positive experience

Religion does not play as an important factor to me during the process of caregiving in terms of positive experience Understand your own emotions and express your negative feelings

Uplift yourself mentally and emotionally Understand dementia and follow medical advice Coping ability

and skills

Attempts to positively cope with the problems and challenges involved

in caregiving Finding appropriate ways to deal with the problematic behaviors of the care recipient

Do not make use of

caregiving resources There is no need to use them

Home based services/foreign carer (paid carers) resources Caregiving

resources Adopts of caregiving

200 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

Participant A11 (age, 40 years) said, “I don’t ignore problems. I think I am kind of moderately optimistic.”

During the interview, participant A11 stated that many people perceive her as highly positive.

I Used to Be Pessimistic/Timid/Soft but Now I Am More Optimistic/Proactive/Stronger

Participant A1 reported not always being as proactive as her current self; she has been her mother’s primary caregiver for 8 years. Of her personalities, she said,

I used to be timid. However, I like to seek solutions when I encounter problems. I like asking for help and can find the resources. I encourage myself to stay active. Otherwise, I think I would remain a pessimist. (A1, age, 55 years)

Another participant reported,

I used to be soft before my husband was ill.[Sobs, choking up.] I have a driver’s license, but I never had the courage to drive. However, now I am much stronger although I sometimes have negative thoughts. (A12, age, 50 years)

I Am Not that Strong, but Taking Care of Elderly Parents Is a Child’s Duty

Participant B4 (age, 50 years), who cares for his mother, said,

I am not that strong. I do not think too much. What I can say is that I face problems and considered it my duty to do so. I think I am capable of dealing with the problems I’ve encountered.

Mutuality

An Improved Relationship With the Patient With Dementia

In this study, 4 participants reported that their relationship with the care recipient is closer than it was before caregiving. Participant A11 (age, 40 years) reported,

I feel our family is “cold.” It seems there is no closeness among us. This is probably because we are a big family. My parents used to work day and night. For 3 years, I have lived with my parents every single day. I left home for more than 2 decades. Mom says she appreciates having me with them. Therefore, I feel caring for them is worth it.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 201

Participant A1 (age, 55 years) noticed that she needed to change her caregiving ways and said,

I used to follow what mom wants and likes, but I became more dominant during a certain period. I think I forgot who I was, as a daughter; she does not like to be treated as an idiot by her own daughter. My attitude and the way I talk matter a lot to her. After I realized these things, I changed myself. She knows I care for her. When she knows I am still talking to her like a daughter, she is much more willing to listen to me or accept my suggestions.

A Strengthened Relationship Between the Caregiver and Other Family Members

Participant B2 (age, 68 years) described a strong relationship with his siblings who supported him continuing as a caregiver. He said,

We brothers are very close to one another. Mom lives with me; we have regular family gatherings in my house. My brothers are medical doctors. They take care of mom as well. I think a family like ours is not common. I care for mom without any complaints. The 5 of us take care of her as much as we can.

Similarly, participant A3 (age, 71 years) said,

My son looks after his father carefully. He does what he can for our family. I notice he is doing well. Compared with other families, we are lucky. I think he wants to encourage me and guide me like a mentor. I am very pleased to have him.

Participant B3 (age, 40 years) continued,

My family and my sister’s family live nearby. We do not want to leave my parents alone.

Caregiver Is More Distant With Care Recipient

Meanwhile, eight out of 18 reported that their relationship was worse than before. Among these eight participants, six are spouse caregivers and two are adult (or grand) children caregivers. Participant B5 said he found there is always tension between his wife and him. He said,

202 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

She has become more aggressive than ever. I used to be more aggressive than she was. She would blame me but not to my children. I tried to talk with her in a rational way, but it did not work. (B5, age, 75 years)

A10 described the changes in their relationship. She said,

He used to talk with good points. He is not talkative. But now he is very quiet. There is less interaction vocally between us now. I feel it is quite strange. I even bring him to do language therapy. It does not help much. He noticed the changes, and depends on me more. He gets nervous when I am not with him outside. (A10, age, 55 years)

A2 used to be close to her father-in-law but this seems to have changed. She said,

We used to be like father and daughter. I speak to my father in a more direct way. I am now nervous when I talk to my father-in-law. I don’t know how to respond to him. We are not as close as we were before. (A2, age, 37 years)

She is also confused and noticed,

I found it is always me to encounter when he is in bad mood. Not my husband. It is quite strange. (A2, age, 37 years)

Granddaughter A9 recalled the old days when their relationship was good. But she has noticed the changes in her grandma. She said,

We used to get along very well. But now she does not like to interact with others. I blame her, so she is upset with me. (A9, age, 30 years)

Spirituality

In this study, spirituality is inferred not only from its religious or spiritual aspects but also from psychological aspects that present implications for human lives from a spiritual perspective. In total six out of 18 respondents reported that “religion has helped me a lot as a caregiver.” However, eight out of 18 respondents reported that “religion is not necessity in my life,” “I do not belong to any particular religion” or “As long as it is a good religion, I will practice it.” Lastly, four out of 18

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 203

respondents reported that “religion is not important to me at all.” The details are as follows:

Religion Has Helped Me Enhance the Caregiving Process

Six participants reported that “religion has helped me a lot as a caregiver.” Practicing Buddhist said her religion is associated with her volunteer work.

Religion provides me access to a place where I can talk about my feelings when I am depressed. On Monday evenings, we meditate with a dharma teacher. First, this type of gathering offers group interaction; second, I can speak aloud while we are chanting sutras. I really enjoy being there and following these religious practices. “Empathy” is what I must learn and apply in the caregiving process. If I treat mom with empathy, I will not argue about little things with everyone or have negative thoughts. (A1, age, 55 years)

Participant A9 stated that religion helped her to have a peaceful mind.

Yes, religion is helpful to me. I meditate. I read Buddhist scriptures at night. It helps me to stay calm. (A9, age, 30 years)

I Believe in the Concept of Karmic Rewards, Samsara, and the Cycle of Death and

Rebirth

Participant A7 shared her experiences of attending Lamrim Chenmo courses. It seems she has benefited from the courses. She believes that all her constraints and the difficult periods during caregiving are meant “to pay her debt.” Moreover, she thinks she and her sister-in-law have “good karmic rewards” compared with other family members who are not involved in caregiving. These concepts seemed to have motivated her to continue in her role as her mother’s caregiver. She continued,

I have attended Lamrim Chenmo courses and learned “my life is to pay her debt” and also “because I owe her from my previous life.” I told my elder sister-in-law that both of us must take care of my mom to gain more karmic rewards. I feel tired and angry sometimes, but then I pause to think about gaining more karmic rewards. I think religion has positively influenced me. In addition, many people attend these classes. They tell me how to react when I encounter problems. (A7, age, 40 years)

204 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

I Do Not Follow a Particular Religion, but I Believe in the Existence of God

Eight participants reported not following one particular religion or that they would be happy to follow whatever religion is considered good. Participant A2 expressed that she worships Matsu and Guanyin and said “I also read the Bible.” She continued,

There should be no compulsion to follow a religion; religion is not necessary to me. Sometimes when I feel low, I read some religious books. I think all gods give people strength. So I read books from different religions. In my opinion, you don’t have to participate in the activities of one religion nor do you have to part with them unless you have a need to follow it. I do not like attending those types of activities. I think we have to depend on our own attitudes if we want to avoid suffering. (A2, age, 36 years)

My Spiritual Strength Is Enhanced By Worshiping My Ancestors

A3, who has been taking care of her husband for 25 years, stated that she “cannot figure out why I don’t follow any particular religion. I asked myself, ‘Why didn’t I need religion to guide me all these years?’” She continued,

Religion provides spiritual strength. When you are unable to deal with the constraints of life, you’d best follow a religion. As for myself, I don’t know why I am such a stubborn person. I think as long as I am doing the right thing, I am going on the right path. I can find my way back to the right path when I am lost. These are the types of spiritual strength I mean. In our family, we only worship our ancestors. This is a part of our tradition. I think what is important for us is how much you’ve done, how much you’ve learned, and how much you’ve given. (A3, age, 71 years)

Coping Abilities and Skills

Nine participants reported attempting to positively cope with the problems and challenges involved in caregiving. They adopted the following types of coping abilities and skills: “understand your own emotions and express your negative feelings,” “uplift yourself mentally and emotionally,” “understand dementia and follow medical advice,” and “find appropriate ways to deal with the problematic behaviors of the care recipient.”

Understand Your Own Emotions and Express Your Negative Feelings

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 205

The more you understand your own emotions, the better you can cope with the caregiving role. Worse results occur when you do not express your negative feelings. If you notice you’re under a certain stress, find someone to talk to. You will soon feel relieved.

Uplift Yourself Mentally and Emotionally

Participant A1 reported always self-reflecting on her deeds and what needs to change. She said,

I have been my mom’s caregiver for more than 8 years. Until recently, I could not bounce back quickly from negative emotions. This was probably because of my nature as I tended to look at things from a negative perspective. However, I now tell myself ‘she is not that bad,’ ‘I shouldn’t be too worried about her,’ and ‘these things are not completely my fault.’ Once I am back on track, most of my burdens and stress are reduced or eliminated. (A1, age, 55years)

Participant A3 (age, 71 years) reported,

If other people were in my situation, they would likely be filled with rage. I have just accepted everything. I looked at my heart and thought what other methods I could apply in working with him. This is how I have sustained myself over the past 25 years. Life does not have a single way out. It is full of changes that are interrelated. Being my husband’s caregiver for 25 years has trained me to be resilient and cope.

Understand Dementia and Follow Medical Advice

Participant A3 (age, 71 years) suggested,

You have to listen to your doctor’s advice because you don’t understand dementia. Different stages of dementia have different types of hardships and burdens.

Finding Appropriate Ways to Deal With the Problematic Behaviors of the Care

Recipient

Participant A2 was previously a fruit vendor in an open market. After her father-in-law moved in with her and her family, she decided to stop working there and spend more time at home. She has been avidly participating in educational programsand family support groups. She wants to learn how to communicate with her father-in-law in particular. Similarly, another participant recalled being

206 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

embarrassed when she was told about her husband asking others for cigarettes. It took her time to cope andrealizewhat was most appropriate for her and her husband. She said,

It was not like him; he would never do this before. Gradually, I adjusted my ways of thinking and stopped asking him to quit smoking. Instead I allowed him to smoke, but limited the number of cigarettes. (A12, age, 50 years)

Participant B2 reported that positivity helped him to grow and become more capable of coping with further challenges. He said,

I have looked after my wife, who has a mental illness, for more than 30 years. I am an experienced caregiver. I would say ‘time, health, and energy’ are essentials for a caregiver. Considering my mom as an example, I learned the skills to cope with her problem behaviors. These types of skills are important. If the care recipient is emotionally and physically stable, you will feel relief, too. (B2, age, 68 years)

Caregiving Resources

The findings show eleven out of 18 participants do not make use for caring resources. Only three out of the 18 reported that they used both home based service and foreign carer resources. There are only 4 participants who reported they stopped using caring resources for various reasons. Caregiving resources were not adopted by most participants as they reported “there is no need to use them.” Participant B4 (age, 50 years) said,

So far, we can manage by ourselves. I know about caregiving resources. We don’t need to use them now.

A care recipient refusing to be cared for by someone unfamiliar was also commonly reported. A participant said,

She would refuse care from an unfamiliar person. I think she would like her daughter or son to accompany her until the end. (A6, age, 50 years)

For caregivers who rely on pensions for their income, the cost of paid services may be a considerable expense. Participant A3 mentioned,

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 207

If I calculate the entire cost of caregiving, how much would I need for 1 year? Ten years? We are not wealthy, so we have to calculate it thoroughly. (A3, age, 71 years)

Despite a relatively small number of participants adopting caregiving resources (e.g., home-based services and foreign caregivers), those who are using these resources stated approvingly that the resources provided them the opportunity to take a break.

Positive Changes Derived from Caregiving

Seven participants reported experiencing positive changes from the caregiving process. Participant B2 expressed,

My temper has changed. I used to be stubborn and strong. There was only black and white in my head. Now I have realized there is no absolute right or wrong… it all depends on your mindset. It is the same for the care recipient. I am pleased to see [my mother] feeling comfortable after bathing. I might feel tired or exhausted but once I see that she is feeling good, I am relieved.

Participant A1 mentioned that she has learned to be more empathetic toward others and has becomes skilled at observing people.

I now know how to change my ways of thinking. Sometimes, I remain pessimistic and perceive things in a negative way. To be empathetic toward others is not easy. I feel my life is a learning process. I need to learn many things. But I have learned to change myself and look at things from different angles. I’ve benefited a lot from these changes. (A1, age, 55 years)

Participant A7 found it easier than before to stay calm. She said, “I don’t argue about so many things as I used to previously. I am more relaxed than I was.” Participant A12, a housewife with 2 children, managed a flower shop before her husband became ill. She also previously had depression. But because of the illness of her husband with dementia, she has learnt how to uplift herself when encountering problems. She said, “I have become more independent now.”

208 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

Discussion

Transformative Learning Model in Terms of Positive Caregiving

Experiences

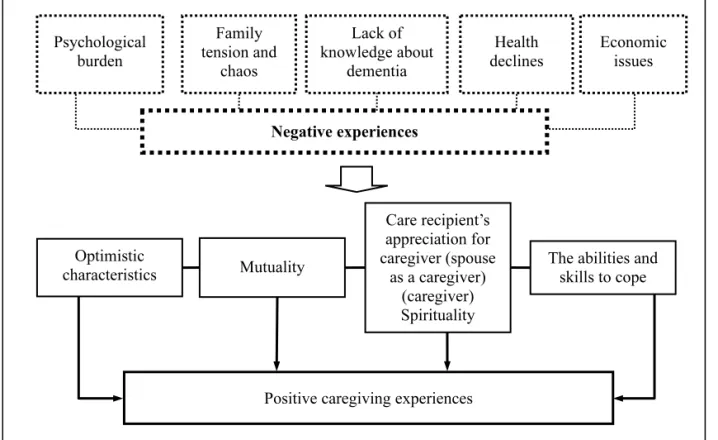

This study first revealed the negative caregiving experiences of family caregivers of people with dementia and subsequently examined the triggers and possible processes that resulted in positive caregiving experiences. Our findings revealed that the triggers are divided into 4 aspects: optimistic characteristics, mutuality, spirituality, and coping abilities and skills. Each aspect contained different elements that facilitated the development of the transformative learning model in terms of positive caregiving experiences (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Transformative Learning Model of Positive Caregiving Experiences. The author used different thickness of dot lines to indicate “Negative experiences” were resulted from “Psychological burden,” “Family tension and chaos,” “Lack of knowledge about dementia,” “Health declines,” and “Economic issues” factors.

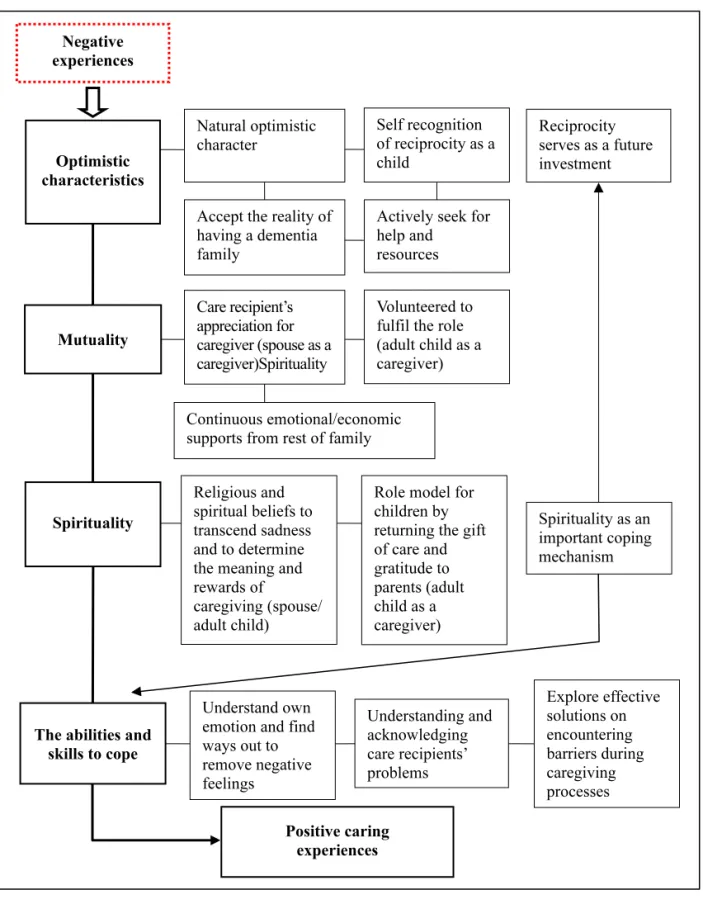

The details of each aspect are listed to reveal how the caregiving experiences of family caregivers changed from negative to positive (Figure 2).

Positive caregiving experiences Negative experiences Care recipient’s appreciation for caregiver (spouse as a caregiver) (caregiver) Spirituality

The abilities and skills to cope Optimistic characteristics Mutuality Family tension and chaos Psychological burden Lack of knowledge about dementia Health declines Economic issues

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 209 Positive caring experiences Self recognition of reciprocity as a child

Role model for children by returning the gift of care and gratitude to parents (adult child as a caregiver) Reciprocity serves as a future investment Negative experiences Religious and spiritual beliefs to transcend sadness and to determine the meaning and rewards of caregiving (spouse/ adult child) Natural optimistic character Spirituality as an important coping mechanism Actively seek for

help and resources

Volunteered to fulfil the role (adult child as a caregiver) Care recipient’s appreciation for caregiver (spouse as a caregiver)Spirituality Accept the reality of having a dementia family Optimistic characteristics Spirituality Mutuality Understand own emotion and find ways out to remove negative feelings Explore effective solutions on encountering barriers during caregiving processes Understanding and acknowledging care recipients’ problems Continuous emotional/economic supports from rest of family

Figure 2. Driving Forces that Stimulate the Transformation of Family Caregivers from Negative to Positive Experiences. The author used different thickness of lines to indicate how “Negative experiences” were transformed into “Positive caring experiences” via the following triggers: Optimistic characteristics, Mutuality, Spirituality, and the abilities and skills to cope.

The abilities and skills to cope

210 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

The study participants who reported being optimistic revealed more favourable self-adjustment and active behavior on encountering problems during caregiving. The findings were in concordance with a previous study reporting that individual differences in optimism play an important role in adjusting to stressful life events (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 2001). Apart from natural character as self reported as optimistic, the participants reported that their characteristics changed from pessimistic to optimistic and from soft to strong throughout the caregiving process; this may be interpreted as the participants accepting the reality of having a family member with dementia and actively seeking help and resources to make themselves stronger and more capable of managing problems. In this study, optimistic characteristics contributing to positive caregiving experiences should not be considered as single factors; other factors should be examined, particularly those associated with mutuality (e.g., supports from other family members), coping abilities and skills (e.g., understand oneself, knowledge of the disease of dementia), and spirituality or spiritual strength (e.g., worship the God, follow religious concepts).

A study reported that the reciprocal relationship between caregivers and care recipients is a critical source of positive caregiving experiences (Nolan, Grant, & Keady, 1996). Echoing a previous study, the findings revealed that “an improved relationship with the family people with dementia” and “a strengthened relationship between the caregiver and other family members” helped the participants to develop a positive caring experience either with the care recipient or other family members. Unlike patients with other diseases, those with dementia are physically and emotionally dependent on their caregivers and fundamental changes occur in their relationships. Namely, the quality of the caregiver – care recipient relationship often worsens over time (Schulz & Martire, 2004, p. 243). The findings revealed that adult children caregivers who volunteered to fulfill the role of caregiver had particularly strong relationships with care recipients, regardless of gender and even if the relationship was distant previously. However, the results varied for spouse caregivers. In some cases, the relationship tended to be worse than it had been before the diagnosis of dementia. In some other cases, once the caregiver, mainly the wife, accepted the fact of her husband’s disease and problem behaviors, their relationship improved if it was strained previously. If the care recipient, typically the husband with mild- or moderate-stage dementia, showed appreciation for the caregiver’s efforts, caregiver mutuality was considerably increased. Continuous support from the rest of the family (e.g., children and spouse), both emotionally and economically, was a significant contributor to positive relationships between caregivers and other family members. By contrast, a lack of communication with other family members or care being solely provided by primary caregivers tended to worsen caregiver mutuality.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 211

In accordance with Farran et al. (1991), this study revealed that caregivers relied on their religious and spiritual beliefs to transcend sadness and to determine the meaning and rewards of caregiving. For caregivers who regularly participated in religious practices, religion provided a space to meditate, calm their emotions, or reflect on the caregiving problems they encountered daily. In addition, the participants learned to be more empathetic toward care recipients. This study indicated that deeply embedded notions of karmic rewards, samsara, and the cycle of death and rebirth may help caregivers to recognize the positive aspects of caregiving. The ideas of “paying her debt” and “I owe my mother from my previous life” reflect Buddhist karma and the law of retribution. Similarly, adult children in this study wanted to be role models for their children by returning the gift of care and expressing gratitude to their parents for raising them. This is essentially a behavior based in reciprocity that also serves as a future investment. The practice of worshiping ancestors is common in Taiwanese families. This notion enables caregivers to do the right things and proceed on the right path. In concordance with previous studies, the caregivers of terminally and chronically ill patients relied on spirituality as a crucial resource (Spurlock, 2005, p. 154); spirituality was identified as an important coping mechanism among caregivers of patients with dementia (Kaye & Robinson, 1994). This study primarily demonstrated how Buddhism, spiritual beliefs, and traditional worship result in positive caregiving experiences. Thus, caregivers became able to negotiate between bliss and suffering and accept suffering as a part of their daily life. They also learned to reintegrate daily stress and spiritual strength, which uplifted them and helped them find solutions to their daily caregiving problems.

In accordance with a previous study (Cheng, Mak, Lau, Ng, & Lam, 2016), the findings regarding coping abilities and skills (e.g., express negative feelings, understand dementia and follow the medical advice, and find appropriate means of dealing with the problematic behaviors of the recipients) revealed that understanding and acknowledging care recipients’ problems helped family caregivers to appreciate the uncontrollability of the recipients’ symptoms and to refrain from imposing unrealistic demands. This study indicated that positive caregivers are more inclined to explore effective solutions on encountering barriers during caregiving processes rather than assuming that the problematic behaviors are intentional.

Caregiving resources were not highly required by the study participants for various reasons. These included care recipients having mild-stage dementia or refusing to be cared for by someone unfamiliar, or the costs of hiring a professional caregiver being prohibitive. The present findings are in accordance with a previous study on the prevalence of dementia in Taiwan (Taiwan Alzheimer’s Disease Association, 2014), which reported that 71.3% of dementia people were cared for by their

212 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

family members, 19.1% of the families employed a foreign caregiver, and only 3.2% of the families used home-based services. Only 2.2% and 0.2% of the families employed Taiwanese caregivers and daycare centres. Despite the findings showing that only a small number of participants adopted home-based caregiving or foreign caregivers, caregivers benefited both mentally and physically.

Limitations

There are some limitations that could be addressed through future research. Qualitative data explored the experiences and positive changes of primary family caregivers of people with dementia regardless age, social and economic status of caregivers and the characteristics and stages of dementia of care receivers. Further research is better to understand the view points from different age cohorts of caregiver (e.g., young old or oldest old), residential location (e.g., urban or rural areas) and life history of care receivers. In addition, the stages of dementia proceed vary on each individuals. In this study, the participants were interviewed once or twice in a short period of time and the latter changes from both caregivers and care receiver were remained unknown. Future longitudinal research could adopt a six-month or up to two-year length of approaches to address this limitation.

Conclusion

This study revealed various positive changes derived from caregiving in the participants: 1. The participants learned to stay calm and patient and to be less worried.

2. They have learned to be more tolerant and perform self-adjustments. 3. They became more empathetic.

4. They grew closer to the care recipients.

5. They now have increased knowledge and skills for managing dementia. 6. They are aware of the importance of following medical advice.

7. They have become more independent.

8. They are aware of their own health conditions.

9. They have learned that everyone, including people with dementia, can keep learning. 10. They want to be role models for their children.

11. They have learned to not expect love to be reciprocated. 12. They have grown spiritually.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 213

This study highlighted positive changes in caregiving experiences are caused by various triggers: optimistic characteristics, mutuality, spirituality, and coping abilities and skills. The caregiving experiences of the participants are possibly to be able to change from negative to positive throughout the caregiving process. This study revealed that participants accept the reality of having a family member with dementia and actively seeking help both medical and caregiving resources that make themselves stronger and more capable of managing problems. Adult children caregivers who volunteered to fulfill the role of caregiver had particularly strong relationships with care recipients, and even if the relationship was distant previously. However, for spouse caregivers, in some cases, the mutual relationship tended to be worse than it had been before the diagnosis of dementia. If the care recipient, typically the husband with mild- or moderate-stage dementia, showed appreciation for the caregiver’s efforts, caregiver mutuality was considerably increased. Continuous support from other family members both emotionally and economically contributed to positive relationships between caregivers and other family members. Religion provided a space to meditate, calm their emotions, or reflect on the caregiving problems they encountered daily. The practice of worshiping ancestors, are commonly seen families in Taiwan, enables caregivers to do the right things and proceed on the right path. For adult children in particular, the desire of becoming role models for their children by returning the gift of care and expressing gratitude to their parents for raising them provided the strengths to positive caregiving experiences. Mostly important, equipped with medical knowledge and coping skills contributed to understand and acknowledge care recipients’ problems. Also it helped family caregivers to appreciate the uncontrollability of the recipients’ symptoms and to refrain from imposing unrealistic demands. Despite caregiving resources were not highly required by the study participants, for those who adopted the resources reported to be benefited from them (e.g., home based service or paid carer).

The population of Taiwan is rapidly aging, therefore, the needs and challenges for caregivers continue to grow. Therefore, this model provides the details of the positive experiences of caregivers and they should be widely propagated. These positive outcomes may also assist many of whom remain pessimistic and seek ways to escape daily circumstances. In the increasing numbers of family caregivers of people with dementia in Taiwan and worldwide, this study provides long-term care policymakers, scholars, healthcare professionals, practitioners and family caregivers of people with dementia with a better understanding of the challenges and needs.

214 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Ministry of Science and Technology (grant number NSC 102 DFA1000004). The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers. Her deeply thanks and respects to all the participants of family caregivers in this study. Their words had made this study meaningful and valuable. Thank you to the staff of the Division of Neurology from Chang Gang Memorial Hospital in Kaohsiung, the staff of the Association of R.O.C. Dementia Family Caregivers in Taichung and the staff of Kaohsiung Smart Action.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 215

References

Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2016). World Alzheimer report 2016: Improving healthcare for people living with dementia. Retrieved from https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimer Report2016.pdf

Arno, P. S., Levine, C., & Memmott, M. M. (1999). The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Affairs, 18(2), 182-188. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.18.2.182

Chan, S. M., & O’Connor, D. L. (2008). Finding a voice: The experience of Chinese family members participating in family support groups. Social Work with Groups, 31(2), 117-135. doi:10.1080/01609510801960858

Cheng, S.-T., Mak, E. P. M., Lau, R. W. L., Ng, N. S. S., & Lam, L. C. W. (2016). Voices of Alzheimer caregivers on positive aspects of caregiving. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 451-460. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu118

Chiu, Y.-C., Huang, S.-H., & Shyu, Y.-I. (2004). Family caregivers’ fatigue, burden and depression in Alzheimer’s patients. The Journal of Long-Term Care, 7(4), 338-351.

Donovan, M. L., & Corcoran, M. A. (2010). Description of dementia caregiver uplifts and implications for occupational therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(4), 590-595. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09064

Farran, C. J. (1997). Theoretical perspectives concerning positive aspect of caring for elderly persons with dementia: Stress/adaptation and existentialism. The Gerontologist, 37(2), 250-256. doi:10.1093/geront/37.2.250

Farran, C. J., Keane-Hagerty, E., Salloway, S., Kupferer, S., & Wilken, C. S. (1991). Finding meaning: An alternative paradigm for Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers. The Gerontologist, 31(4), 483-489. doi:10.1093/geront/31.4.483

Folkman, S. (1997). Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine, 45(8), 1207-1221. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3

Funk, L. M., Chappell, N. L., & Liu, G. P. (2013). Associations between filial responsibility and caregiver well-being: Are there differences by cultural group? Research on Aging, 35(1), 78-95. doi:10.1177/0164027511422450

Gainey, R. R., & Payne, B. K. (2006). Caregiver burden, elder abuse and Alzheimer’s disease: Testing the relationship. Journal of Health & Human Services Administration, 29(2), 245-259. Hollis-Sawyer, L. A. (2003). Mother-daughter eldercare and changing relationships: A path-analytic

216 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen

investigation of factors underlying positive, adaptive relationships. Journal of Adult Development, 10(1), 41-52. doi:10.1023/A:1020738804030

Holroyd, E. A., & Mackenzie, A. E. (1995). A review of the historical and social processes contributing to care and caregiving in Chinese families. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22(3), 473-479. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22030473.x

Huang, J. (2009). A study on the process of experiential learning of the elders care for the disability elder (Unpublished master’s thesis). National Chung Cheng University, Chiayi County, Taiwan. Huang, S.-S., Lee, M.-C., Liao, Y.-C., Wang, W.-F., & Lai, T.-J. (2012). Caregiver burden associated

with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in Taiwanese elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(1), 55-59. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2011.04.009 Huang, M.-F., Huang, W.-H., Su, Y.-C., Hou, S.-Y., Chen, H.-M., Yeh, Y.-C., & Chen, C.-S. (2015).

Coping strategy and caregiver burden among caregivers of patients with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Diseases and Other Dementias, 30(7), 694-698.

Kaye, J., & Robinson, K. M. (1994). Spirituality among caregivers. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26(3), 218-221. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00317.x

Kitchenham, A. (2008). The evolution of John Mezirow’s transformative learning theory. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(2), 104-123. doi:10.1177/1541344608322678

Kramer, B. J. (1997). Gain in caregiving experience: Where are we? What next? The Gerontologist, 37(2), 218-232. doi:10.1093/geront/37.2.218

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Liu, D., Hinton, L., Tran, C., Hinton, D., & Barker, J. C. (2008). Reexamining the relationships among dementia, stigma and aging in immigrant Chinese and Vietnamese family caregivers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23(3), 283-299. doi:10.1007/s10823-008-9075-5 Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2007). Learning in adulthood: A

comprehensive guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Mezirow, J. (Ed.). (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(1), 58-63. doi:10.1177/1541344603252172

Nolan, M., Grant, G., & Keady, J. (1996). Understanding family care: A multidimensional model of caring and coping. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Chia-Ming Yen Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches 217

Pallant, J., & Reid, C. (2014). Measuring the positive and negative aspects of the caring role in community versus aged care setting. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 33(4), 244-249. doi:10. 1111/ajag.12046

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and non-caregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250-267. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (2001). Optimism, pessimism and psychological well-being. In E.-C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research and practice (pp. 189-216). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/ 10385-009

Schulz, R., & Martire, L. M. (2004). Family caregiving of persons with dementia: Prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 12(3), 240-249.

Spurlock, W. R. (2005). Spiritual well-being and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Geriatric Nursing, 26(3), 154-161. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2005.03.006

Taiwan Alzheimer’s Disease Association. (2014, April). Dementia friendly community. Paper presented at the Conference Proceedings of the Investigation on Prevalence Study of Dementia in Taiwan, Taipei, Taiwan.

Taiwan Alzheimer’s Disease Association. (2017). Estimated number of dementia patients in Taiwan between 2016 and 2061. Retrieved from http://www.tada2002.org.tw/tada_know_02.html Wang, Y.-N., Shyu, Y.-I., Chen, M.-C., & Yang, P.-S. (2010). Reconciling work and family

caregiving among adult-child family caregivers of older people with dementia: Effects on role strain and depressive symptoms. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(4), 829-840. doi:10.1111/j. 1365-2648.2010.05505.x

Wang, Y.-N., Shyu, Y.-I., Tsai, W.-C., Yang, P.-S., & Yao, G. (2013). Exploring conflicts between caregiving and work for caregivers of elder with dementia: A cross-sectional, correctional study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(5), 1051-1062. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06092.x

Wallhagen, M. I., & Yamamoto-Mitani, N. (2006). The meaning of family caregiving in Japan and the United States: A qualitative comparative study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(1), 65-73. doi:10.1177/1043659605281979

218 Transformative Learning & Positive Experience Approaches Chia-Ming Yen 教育科學研究期刊 第六十三卷第二期 2018年,63(2),187-218 doi:10.6209/JORIES.201806_63(2).0008