準確界定漢語中分類詞 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Identifying True Classifiers in Mandarin Chinese. By Wan-chun Lai. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. io. y. sit. Graduate Institute of Linguistics. er. Nat. A Thesis Submitted to the. n. a lin Partial Fulfillment of the i v nof C h for the Degree Requirements U engchi Master of Arts. September 2011.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. C 2011 Copyright ○. Wan-chun Lai All Rights Reserved. i n U. v.

(4) Acknowledgements 誌謝. 對於這篇論文的完成,首先我最感謝的是我的指導教授 何萬順老師。從這 篇論文的開始到完成,老師總是不厭其煩的回答我所有疑惑,並提供我相關資源 的協助,給予我很大的幫助。由衷地感謝您的諄諄教導及您的鼓勵,因為有您, 我才能夠順利完成這篇論文。也感謝所上的老師在這兩年來對我的照顧以及教. 治 政 賴惠玲老師及師丈對我的照顧,我會永遠 大 記得您給予的寶貴意見。也感謝我的口試委員: 張郇慧老師及師大 詹曉蕙老 立 導,為我奠下學術基礎。此外,感謝. ‧ 國. 學. 師,在我計畫書口試及論文口試時,不但撥空前來還提供了我許多重要的意見和 建議,讓我的論文能夠趨近完善。. ‧. 接著,感謝惠玲助教學姐總是傾聽我的煩惱,給我意見。謝謝我的同學們(晉. sit. y. Nat. 偉、小貞、姿幸、婉婷、媛媜、書豪、柏溫、心綸、美杏、侃彧)陪伴我度過研. al. er. io. 究所生活,因為有你們,我成長了許多。謝謝你們讓我在政大留下許多美好回憶。. v. n. 也謝謝一路上以來幫助我、支持我、聽我發牢騷的朋友智盛、芭比學姐、Dora、. Ch. engchi. i n U. Monica、偉嘉哥、幫助我上政大的老師們、學長姐、學弟妹,還有好多好多的人, 謝謝你們。 最後,感謝我強大的後援團(爸爸、媽媽、弟弟),因為有你們強大的支持, 我才可以毫無顧慮的往前邁進、通過ㄧ關又ㄧ關。謝謝你們!政大碩士學位獻給 我強大的後援團。另外,也感謝上蒼,謝謝祢們賜給我的一切,對我現在所擁有 的,我心存感激!. iv.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………...iv Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………...v Tables……………………………………………………………………....................vii Figures…………………………………………………………………….................viii Chinese Abstract………………………………………………………………….......ix English Abstract………………………………............................................................x CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………1 1.1 Motivation and Purpose………………………………………………………..2 1.2 Conventions of the Data……………………………………………………….3 1.3 Organization of the Thesis……………………………………………………..4. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. II. LITERATURE REVIEW……………………………………………………..6 2.1 Classifiers and Measure Words………………………………………………...6 2.1.1 Traditional Views………………………………………………………...6 2.1.2 Recent Views…………………………………………………………….8 2.2 Mandarin Chinese Classifier Categorizations………………………………...10 2.2.1 Chao (1968)…………………………………………………………….10 2.2.2 Erbaugh (1986)…………………………………………………………11 2.2.3 Hu (1993)……………………………………………………………….12 2.2.4 Huang et. al. (1997)…………………………………………………….12 2.2.5 Gao and Malt (2009)……………………………………………………14 2.3 Remark………………………………………………………………………..15. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. III. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS………………………………………..19 3.1 Numeral / adjectival stacking………………………………………………...19 3.2 De-insertion…………………………………………………………………..26 3.3 Ge-substitution………………………………………………………………..29 3.4 Yi-multiplier…………………………………………………………………..31 3.5 Remark………………………………………………………………………..34 IV. DATA ANALYSIS……………………………………………………………38 4.1 Re-classify Mandarin Chinese Classifier Categorizations……………………39 4.1.1 Chao (1968)…………………………………………………………….45 4.1.1.1 Classifiers………………………………………………………45 4.1.1.1.1Mei2 枚………………………………………………..46 4.1.1.1.2 Ding3 頂……………………………………………...47 4.1.1.1.3 Words Re-classified as Classifiers…………………...49 v.

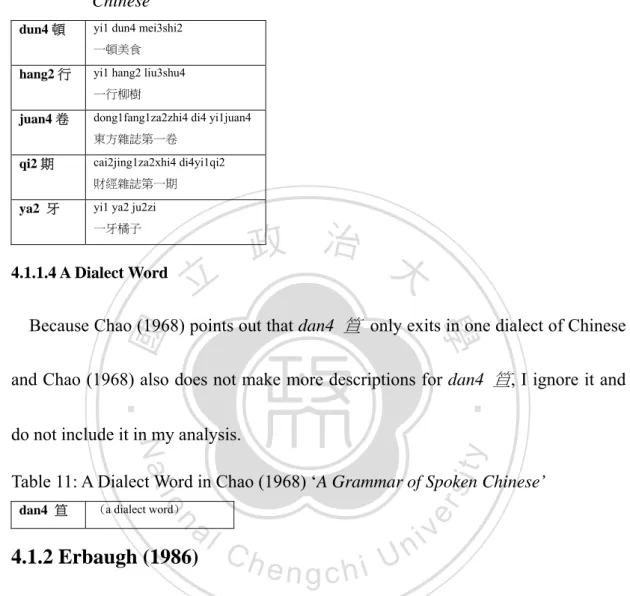

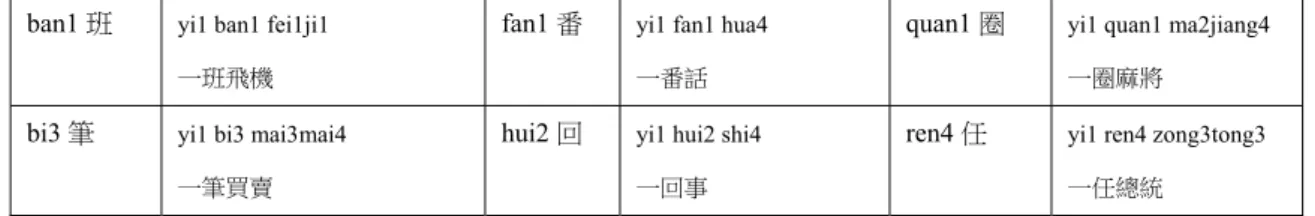

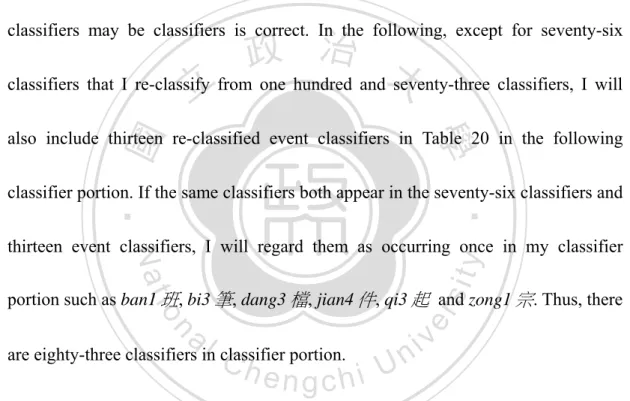

(6) 4.1.1.2 Xc and Xm……………………………………………………...50 4.1.1.2.1Ba3 把………………………………………………...50 4.1.1.2.2 Kou3 口………………………………………………54 4.1.1.2.3 Words Re-classified as Xc and Xm…………………...57 4.1.1.3 Measure Words………………………………………………...58 4.1.1.3.1 Hang2 行……………………………………………..58 4.1.1.3.2 Words Re-classified as Measure Words……………...59 4.1.4 A Dialect Word…………………………………………………...60 4.1.2 Erbaugh (1986)…………………………………………………………60 4.1.2.1 Words Re-classified as Classifiers……………………………..61 4.1.2.2 Words Re-classified as Xc and Xm……………..........................61 4.1.2.3 Words Re-classified as Measure Words………………………..62 4.1.3 Hu (1993)……………………………………………………………….62 4.1.3.1 Words Re-classified as Classifiers……………………………..62 4.1.3.2 Words Re-classified as Xc and Xm……………………………..63 4.1.3.3 Words Re-classified as Measure Words………………………..63 4.1.4 Huang et. al. (1997)…………………………………………………….63 4.1.4.1 Words Re-classified as Classifiers……………………………..71 4.1.4.2 Words Re-classified as Xc and Xm………………......................73 4.1.4.3 Words Re-classified as Measure Words………………………..74 4.1.4.4 Inapplicable Words…...…………………………………….......76 4.1.5 Malt and Gao (2009)……………………………………………………76 4.1.5.1 Words Re-classified as Classifiers……………………………..77 4.1.5.2 Words Re-classified as Xc and Xm…………………………….79 4.1.5.3 Words Re-classified as Measure Words………………………..80 4.2 True Classifiers………………………………………………………………..81 4.2.1 Core Classifiers and Non-core Classifiers………………………………81 4.2.2 An Experiment on Classifier Identifications……………………………85 4.3 A Semantic Categorization of True Classifiers……………………………….95. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. V.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. CONCLUDING REMARKS………………………………………………..103 5.1 Summary of the Thesis……………………………………………………...103 5.2 Issues for Future Study……………………………………………………...105. REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………107 APPENDIXS………………………………………………………………………112 A. Pre-test of Classifier Identifications………………………………………112 B. Formal Test of Classifier Identifications………………………………….114 C. A Semantic Categorization of Mandarin Chinese Classifier (Hu 1993)…...116. vi.

(7) TABLES Table 1. The 51 Classifiers Proposed by Chao (1968)……………………………………..11 Table 2. The 22 Classifiers Proposed by Erbaugh (1986)………………………………….11 Table 3. The 20 Classifiers Proposed by Hu (1993)………………………………………..12 Table 4. The 173 Classifiers Proposed by Huang et. al. (1997)……………………............13 Table 5. The 126 Classifiers Proposed by Gao and Malt (2009)…………………………...15 Table 6. Asymmetry of the Rightmost Digit (Her 2011b, Table 1)………………...............32 Table 7. The Relation of the Three Portions………………………………………………..44 Table 8: 39 Words of Classifiers in Chao (1968) ‘A Grammar of Spoken Chinese’………..49 Table 9: 6 Words of Xc and Xm in Chao (1968) ‘A Grammar of Spoken Chinese’...............57 Table 10: 5 Words of Measure Words in Chao (1968) ‘A Grammar of Spoken Chinese’………………………………………………………………………...60 Table 11: A Dialect Word in Chao (1968) ‘A Grammar of Spoken Chinese’………………60 Table 12: 18 Words of Classifiers in Erbaugh (1986)……………………………...............61. 政 治 大 Table 14: 1 Word of Measure Word in Erbaugh (1986)……………………………………62 立 Table 15: 15 Words of Classifiers in Hu (1993)…………………………………................62. Table 13: 3 Words of Xc and Xm in Erbaugh (1986)……………………………………….61. ‧ 國. 學. Table 16: 4 Words of Xc and Xm in Hu (1993)…………………………………………….63 Table 17: One Measure Word in Hu (1993)………………………………………………..63. ‧. Table 18: The 14 Kind Classifiers Proposed by Huang and Ahren (2003)………...............65 Table 19: The 35 Event Classifiers Proposed by Huang and Ahren (2003)………………..65. y. Nat. Table 20: 13 Event Classifiers Testified as Classifiers……………………………………..68. sit. Table 21: 83 Words of Classifiers in Huang et. al. (1997)‘Mandarin Daily Dictionary of. al. er. io. Chinese Classifiers’ ……………………………………………………………..71. n. Table 22: 21 Words of Xc and Xm in Huang et. al. (1997)‘Mandarin Daily Dictionary of. Ch. i n U. v. Chinese Classifiers’ ……………………………………………………………..73. engchi. Table 23: 75 Words of Measure Words in Huang et. al. (1997)‘Mandarin Daily Dictionary of Chinese Classifiers’ ………………………………………………………….74 Table 24: NA Words in Huang et. al. (1997)‘Mandarin Daily Dictionary of Chinese Classifiers’ ………………………………………………………………………76 Table 25: 71 Words of Classifiers in Malt and Gao (2009)………………………………...77 Table 26: 18 Words of Xc and Xm in Malt and Gao (2009)………………………………..79 Table 27: 37 Words of Measure Words in Malt and Gao (2009)…………………………...80 Table 28: 22 Core Classifiers………………………………………………………………83 Table 29: 90 Non-core Classifiers…………………………………………………….........84 Table 30: Statistics of Non-core Classifiers…………………………………......................89 Table 31: Percentage of Test Items as a Classifier in Non-core Classifiers………………..93 Table 32: 61 True Classifiers……………………………………………………………….94 Table 33: Sixty-one True Classifiers and Their Semantic Meanings……............................97 Table 34: Sixty-one True Classifiers and Their Bottom-up Semantic Categorizations…….99 vii.

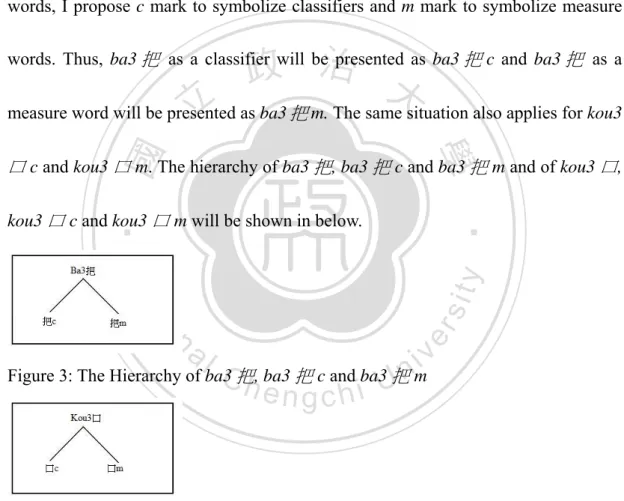

(8) FIGURES Figure 1: Classifier System………………………………………………………...............10 Figure 2: The Hierarchy of Lexemes and Word-forms…………………………………….41 Figure 3: The Hierarchy of ba3 把, ba3 把 c and ba3 把 m………………………...............43 Figure 4: The Hierarchy of kou3 口, kou3 口 c and kou3 口 m…………………………….43 Figure 5: Intersection of Two Sets………………………………………………………….82 Figure 6: Union of Two Sets……………………………………………………………….83 Figure 7: Portion of A∪B - 2 × A ∩ B………………………………………………...84. Figure8: A Bottom-up Semantic Categorization of True Classifiers…….. ……...100. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i n U. v.

(9) 國立政治大學研究所碩士論文摘要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:準確界定漢語中分類詞 指導教授:何萬順博士 研究生:賴宛君. 政 治 大. 論文提要內容: (共一冊,二萬七千六百七十三個字,分五章). 立. ‧ 國. 學. 漢語分類詞數量之歧異現象起因於未有一套共同界定分類詞之準則。因此,本 篇論文採用四個以語言學為基礎之準則重新檢視漢語分類詞,並在眾多漢語分類. ‧. 詞分類中,採用五個語言學代表性研究提出之漢語分類詞分類為本篇語料來源。. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. 研究分析之目的在於透過四個以語言學為基礎之準則重新檢視五個代表性人. i n U. v. 物提出之漢語分類詞分類,並使用二個數學法及一個問卷實驗法找出準確的漢語. Ch. engchi. 分類詞。最後,分析所得之準確的漢語分類詞再根據國語日報量詞典列出之分類 詞語意做更進一步的語意分類。在分類詞語意分類上,本篇論文採用下到上之方 向做分類詞語意分類而非傳統上到下之方向,提供完整且精確之漢語分類詞語意 分類。. ix.

(10) Abstract. The discrepancy in the different inventories of Mandarin Chinese classifiers results from there being no identical and consentient tests to identify Mandarin Chinese classifiers. Thus, this thesis adopts four linguistic-based tests as norms to identify Mandarin Chinese classifiers and five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations. 政 治 大. proposed by representative studies (Chao 1968, Erbaugh 1986, Hu 1993, Huang et. al.. 立. 1997 and Malt and Gao 2009) as sources of data in Mandarin Chinese classifier. ‧ 國. 學. categorizations.. ‧. The data analysis focuses on offering true classifiers in Mandarin Chinese through. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. re-classifying five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations on the basis of four. n. linguistic-based tests, applying two mathematical methods and using a questionnaire. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. experiment. Ultimately, true classifiers will be further classified on the basis of their semantic meanings from the Mandarin Daily Dictionary of Chinese Classifiers (Huang et. al.) to provide an explicit semantic categorization in a bottom-up form, rather than a traditional top-down one.. x.

(11) 1. CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION. Previous studies have provided very different inventories of classifiers in. 政 治 大. Mandarin Chinese. The number of Mandarin Chinese classifiers estimated by. 立. previous studies has been given as in variable numbers, for example fifty-one (Chao. ‧ 國. 學. 1968), one hundred and seventy-three (Huang et. al. 1997), one hundred and. ‧. twenty-six (Gao and Malt 2009), four hundred and twenty-seven (Huang & Ahren. Nat. io. sit. y. 2003), two hundred (Hung 1996) and several dozen (Erbaugh 1986, Hu 1993). The. n. al. er. main reason for this drastic discrepancy results from the different standards used in identifying classifiers.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In the traditional view of Chinese grammar, classifiers are regarded as on a par with measure words and no distinction is made between classifiers and measure words. For example, Chao (1968) regards classifiers as ‘individual measure words’ in A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Li and Thompson (1981) blend classifiers and measure words and state that ‘any measure word can be a classifier’. For instance, a measure word such as bang4 磅 can function as a classifier in ‘yi1 bang4 rou4’一磅. 肉. A detailed explanation is given in Section 2.1.1..

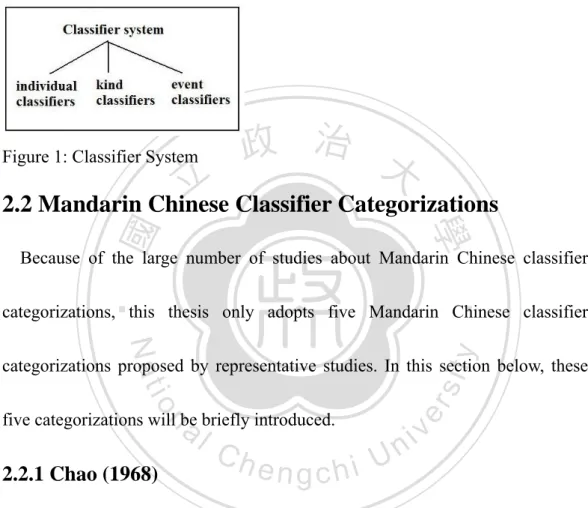

(12) 2. The recent views of classifiers support the differentiation of classifiers and measure words. Tai and Wang (1990), for example, think that it is desirable and possible to differentiate classifiers and measure words. Thus, Tai and Wang (1990) postulate an important semantic distinction between measure words and classifiers: that the notion of measure words is based on quantification, while that of classifiers is based on qualification.. 政 治 大. Apart from supporting the differentiation of classifiers and measure words, Ahren. 立. and Huang (1996) and Huang and Ahren (2003) propose that classifiers can be. ‧ 國. 學. further divided into three subcategories, namely individual classifiers, kind. ‧. classifiers and event classifiers. These three subcategories operate under the classifier. Nat. io. sit. y. system, which is a particular system of a natural language grammar. The above. n. al. er. concept of three subcategories implies that classifiers seem to be more complicated and varied.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 1.1Motivation and Purpose Although numerous studies have been conducted on Mandarin Chinese classifiers, discrepancies can be found in the inventories of the classifiers. The main reason for the discrepancies results from being no identical and consentient norms to identify classifiers. Thus, this thesis will adopt four tests based on linguistic theory mentioned in.

(13) 3. Chapter 3 to re-examine five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations proposed by representative studies including Chao (1968), Erbaugh (1986), Hu (1993), Huang et. al. (1997) and the Gao and Malt (2009), respectively. The first purpose is to re-classify five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations on the basis of the four norms and offer a solution for use in the classification of ambiguous classifiers. Although the concept of ambiguous classifiers has been. 政 治 大. mentioned by Tai and Wang (1990) and Tai (1992), such a classification for. 立. ambiguous classifiers has not been proposed before.. ‧ 國. 學. The next purpose is to offer true classifiers1 which are definite classifiers in. ‧. Mandarin Chinese through comparing the results of the analysis of five Mandarin. Nat. al. er. io. questionnaire experiment.. sit. y. Chinese classifier categorizations, applying two mathematical methods and using a. n. v i n Cclassify The last purpose is to further classifiers on the basis of their semantic h e n true gchi U. meanings as given in the Mandarin Daily Dictionary of Chinese Classifiers (Huang et. al 1997) so as to offer an explicit semantic categorization in a bottom-up form, rather than a traditional top-down one.. 1.2 Conventions of the Data Since the five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations are the source of the data in Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations in this thesis, many of the. 1. A name given by this thesis to express some classifiers is ‘precise classifiers’..

(14) 4. examples used herein thus come from these five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations, which include the grammar book《中國話的文法》“A Grammar of Spoken Chinese” edited by Chao (1968), the dictionary 《國語日報量詞典》 “Mandarin Daily Dictionary of Chinese Classifiers” edited by Huang et. al. (1997) and the PhD dissertation of Hu (1993), and two journal papers of Erbaugh (1986) and of Gao and Malt (2009). Since this thesis focuses on Mandarin Chinese. 政 治 大. classifiers, all the data in this thesis are from studies of Mandarin Chinese classifiers.. 立. The tone system used in this thesis is expressed as none for neutral tone, 1 for high. ‧ 國. 學. level tone, 2 for high raising tone, 3 for falling raising tone and 4 for high falling. io. sit. Nat. 1.3 Organization of the Thesis. y. ‧. tone.. al. er. The thesis is organized in the following way. Both traditional views and recent. n. v i n C hwords will be reviewed views of classifiers and measure e n g c h i U in Section 2.1.1 and 2.1.2.. Brief introductions of the five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations adopted in this thesis will be provided in Section 2.2. Next, Chapter 3 presents the four tests based on linguistic theory tests used in this thesis to re-examine five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations proposed by representative linguists. The notion of numeral / adjectival stacking will be introduced in Section 3.1. Next, the notion of de-insertion and ge-substitution will be introduced in Section 3.2 and 3.3, separately. Section 3.4 provides the notion of yi-multiplier. The data analysis will be discussed.

(15) 5. in Chapter 4 with re-classifications of the five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations proposed by representative studies in Section 4.1. The notion and reason of the emergence of true classifiers will be provided in Section 4.2 and a semantic categorization of true classifiers in a bottom-up form in Section 4.3. Finally, Chapter 5 concludes the study by summarizing the the main points of the thesis and pointing out the implications for future study.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(16) 6. CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW. Although numerous studies have been conducted on numeral classifiers in. 政 治 大. Mandarin Chinese, especially the individual classifiers that are generally called. 立. classifiers in the following chapters in this thesis, the core issues addressed in these. ‧ 國. 學. studies have been controversies in the different definitions and standards of. ‧. identifying classifiers. In the following, two aspects will be concerned. First,. Nat. io. sit. y. different definitions of classifiers will be provided. One is the traditional view of. al. er. classifiers and measure words proposed by Chao (1968) and by Li and Thompson. n. v i n C hrecent one of that U (1981), and the other is the more e n g c h i proposed by Tai & Wang (1990), by Tai (1992, 1994) and by Ahren & Huang (1996) and Huang & Ahren (2003), all of which will be individually discussed. Second, five Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations proposed by representative studies will be briefly introduced. Finally, some remarks for this section will be given.. 2.1 Classifiers and Measure Words 2.1.1 Traditional Views.

(17) 7. In the traditional view of Chinese grammar, classifiers are regarded as on a par with measure words. For example, Chao (1968) treats classifiers as a subcategory of measure words in A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Thus, the classifiers that I concentrate on in this thesis are called individual measure words in Chao (1968). Moreover, Li and Thompson (1981) blend classifiers and measure words and state ‘any measure word can be a classifier.’ The following examples from Li and. 政 治 大. Thompson (1981) can illustrate their opinions. (1) a.. 立. 一 哩. ‧ 國. one. 學. yi1 li3. mile. ‧. ‘one mile’ *b. 一. 個. yi1. ge. Nat. one. C. mile. 一. 磅. yi1. bang4. one. pound. y. sit. n. al. er. li3. io. (2) a.. 哩. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. ‘one pound’ b. 一. 磅. 肉. yi1 bang4 rou4 one. pound. meat. ‘one pound of meat’ Not only does a measure word generally not take a classifier as shown in (1), but.

(18) 8. any measure word can be a classifier as shown in (2). The standard measure li3 哩 in (1a) is acceptable, but not in (1b) because measure words do not take a classifier. However, the standard measure bang4 磅 in (2) is regarded as a classifier by Li and Thompson (1981) because the a phrase shows a measure word functioning as a noun without a classifier and the b phrase shows the same measure word functioning as a classifier with another noun. From observation of (2b), Li and Thompson thus think. 政 治 大. that ‘any measure word can be a classifier’.. 2.1.2 Recent Views. 立. ‧ 國. 學. The recent views of classifiers and measure words support the differentiation of. ‧. classifiers from measure words. For example, Tai and Wang (1990) suggest that it is. Nat. io. sit. y. feasible and desirable to differentiate classifiers from measure words in order to. al. er. better understand the cognitive basis of the classifier system. Thus, Tai and Wang. n. v i n (1990) were the first to studyC Mandarin Chinese classifiers on the basis of cognitive heng chi U. categorization. According to the concept that ‘a classifier denotes some salient perceived or imputed characteristic of the entity to which the associated noun refers’ postulated by Allan (1977), Tai and Wang (1990) think that classifiers denote relatively ‘inherent’ or ‘permanent’ properties while measure words denote ‘contingent’ or ‘temporary’ properties. Tai and Wang (1990) thus propose the following distinction between ‘permanent’ and ‘temporary’ properties of entities as the fundamental cognitive basis for distinguishing between classifiers and measure.

(19) 9. words.. Semantic Distinction between Classifiers and Measure Words. ‘A classifier categorizes a class of nouns by picking out some salient perceptual properties, either physically or functionally based, which are permanently associated with the entities named by the class of nouns; a measure word does not categorize but denotes the quantity of the entity named by a noun.’. But under the view of semantic distinction between classifiers and measure words, Tai (1992) points out that it is difficult to decide in the case of some. 政 治 大. ambiguous classifiers like ba3 把 2 and kuai4 塊 3 as to whether they are. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. words.. 學. classifiers or measure words because these classifiers also function as measure. The other scholars supporting the recent view are Ahren and Huang (1996). sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. and Huang and Ahren (2003). In addition to approving the existence of. i n U. v. classifiers, they think that classifiers can be further divided into three. Ch. engchi. subcategories, namely, individual classifiers, event classifiers and kind classifiers. Individual classifiers are those such tiao2 條 , mian4 面 and so on. Event classifiers coerce event readings on the nouns that they occur with, for example, chu1 齣, chang3 場, tong1 通 and so on. Kind classifiers explicitly mark the nominal element that they select as having a kind reading, such yang4 樣, zhong3. 2. Ba3 把 in yi1 ba3 dao1zi 一把刀子 can mean either ‘one knife’ functioning as a classifier or ‘one handful of knives’ functioning as a measure word. 3 Kuai4 塊 in yi1 kuai4 rou4 一塊肉 can stress either ‘the shape of meat’ functioning as a classifier or ‘a portion of meat’ functioning as a measure word..

(20) 10. 種 , shi4 式 , kuan3 款 and so on. And these three subcategories, namely individual classifiers, kind classifiers and event classifiers, are under a classifier system which is a particular system of a natural language grammar. The relations of these three subcategories and the classifier system are represented below.. Figure 1: Classifier System. 立. 政 治 大. 2.2 Mandarin Chinese Classifier Categorizations. ‧ 國. 學. Because of the large number of studies about Mandarin Chinese classifier. ‧. categorizations, this thesis only adopts five Mandarin Chinese classifier. y. Nat. al. n. five categorizations will be briefly introduced.. 2.2.1 Chao (1968). Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. categorizations proposed by representative studies. In this section below, these. i n U. v. The reason for adopting Chao (1968) is that Chao represents the traditional way of describing Chinese grammar. In A Grammar of Spoken Chinese, Chao postulates that measure words could be divided into nine categories and treats classifiers as a subcategory of measure words. This thesis only concentrates on the first category: individual measures. This category includes fifty-one individual measures as shown below. Tai (1992) mention that Chao’s ‘individual.

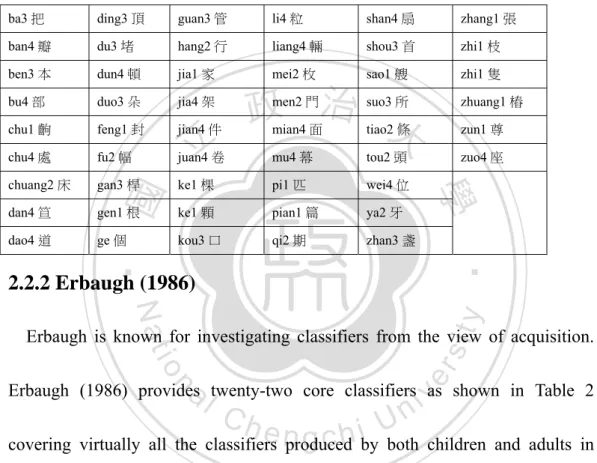

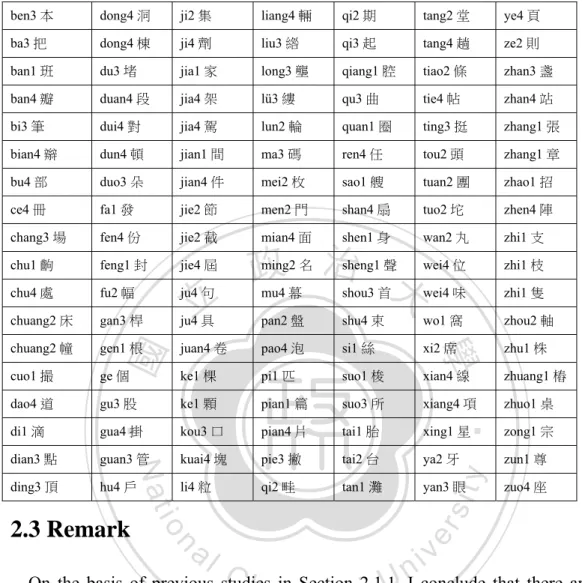

(21) 11. measure’ is actually a classifier on the basis of the semantic distinction between classifiers and measure words proposed by Tai and Wang (1990). Thus, I will call the first category of ‘individual measures’ in Chao (1968) classifiers in the following. Table 1: The 51 Classifiers Proposed by Chao (1968) ba3 把. ding3 頂. guan3 管. li4 粒. shan4 扇. zhang1 張. ban4 瓣. du3 堵. hang2 行. liang4 輛. shou3 首. zhi1 枝. ben3 本. dun4 頓. jia1 家. mei2 枚. sao1 艘. zhi1 隻. bu4 部. duo3 朵. jia4 架. men2 門. suo3 所. zhuang1 樁. chu1 齣. feng1 封. jian4 件. mian4 面. tiao2 條. zun1 尊. chu4 處. fu2 幅. juan4 卷. mu4 幕. tou2 頭. zuo4 座. chuang2 床. gan3 桿. ke1 棵. pi1 匹. wei4 位. dan4 笪. gen1 根. ke1 顆. pian1 篇. ya2 牙. dao4 道. ge 個. kou3 口. qi2 期. zhan3 盞. 學 ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. 2.2.2 Erbaugh (1986). y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. Erbaugh is known for investigating classifiers from the view of acquisition.. v. n. Erbaugh (1986) provides twenty-two core classifiers as shown in Table 2. Ch. engchi. i n U. covering virtually all the classifiers produced by both children and adults in Erbaugh’s studies. No matter in what kind of conversations, adults to adults or adults to children or children to children, Erbaugh (1986) mentions that these core classifiers almost all appear in these conversations. That is to say, Erbaugh (1986) considers that these twenty-two classifiers are representative classifiers. Table 2: The 22 Classifiers Proposed by Erbaugh (1986) ba3 把. gen1 根. ke1 棵. shou3 首. zhi1 枝. ben3 本. jia4 架. ke1 顆. tiao2 條. zhi1 隻. ding3 頂. jian1 間. kuai4 塊. tou2 頭.

(22) 12 duan4 段. jia4 件. li4 粒. wei4 位. duo3 朵. ju4 句. pian4 片. zhang1 張. 2.2.3 Hu (1993) Hu (1993) is also known for investigating classifiers from the view of acquisition. Hu (1993) provides twenty classifiers which are commonly used in the acquisition of Chinese classifiers by young Mandarin speaking children as given in Table 3. Hu also mentions that these twenty classifiers are classifiers which are used to qualify.. 政 治 大. According to Adam and Conklin (1973), classifiers which are used to qualify usually. 立. denote a permanent, particular intrinsic feature of the referent of the noun. On the. ‧ 國. 學. basis of the semantic distinction between classifiers and measure words provided by. ‧. Tai and Wang (1990), the concept of qualifying classifiers proposed by Adam and. Nat. classifiers provided by Hu (1993) in this thesis.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Conklin (1973) corresponds to classifiers. Thus, I focus on the twenty qualifying. C h by Hu (1993) U n i Table 3: The 20 Classifiers Proposed engchi ba3 把 jian4 件 liang4 輛 shuang1 雙 wei4 位 ge 個. ke1 顆. pi1 匹. tai2 台. zhang1 張. gen1 根. kuai4 塊. pian4 片. tiao2 條. zhi1 枝. jia4 架. li4 粒. sao1 艘. tou2 頭. zhi1 隻. v. 2.2.4 Huang et al. (1997) A comprehensive dictionary of Mandarin classifiers named the Mandarin Daily Dictionary of Chinese Classifiers was edited by Huang et. al. (1997). This dictionary is a representative example of modern Mandarin Chinese. Although many Mandarin Chinese classifier dictionaries have been published, Huang et. al. propose that their.

(23) 13. dictionary marks a breakthrough in the lexicography of modern Mandarin Chinese. The dictionary has the following two traits. First, the data in the dictionary is not sourced from existing dictionaries or on the personal opinions, but based on findings from a balanced large electronic corpus (Sinica Corpus) as the database for this dictionary. Second, this dictionary is edited by many linguists with much experience in analyzing Chinese. Thus, this dictionary is claimed to provide a completely new. 政 治 大. and accurate listing of Mandarin Chinese classifiers.. 立. In this dictionary, Mandarin Chinese classifiers are divided into seven categories.. ‧ 國. 學. This thesis only concentrates on the first category: individual classifiers which. ‧. include one hundred and seventy-three individual classifiers as shown in Table 4.. y. dian3 點. ban1 班. die2 疊. ban3 版. ding3 頂. ban4 瓣. ding4 錠. bang1 幫. dong4 棟. huo3 夥. kuai4 塊. pie3 撇. ting3 挺. zhi1 只. ben3 本. du3 堵. ji2 級. kuan3 款. pou2 抔. tou2 頭. zhi1 枝. bi3 筆. duan4 段. ji2 集. kun3 捆. qi2 畦. tuan2 團. zhi1 隻. bing3 柄. dui1 堆. ji2 輯. lan2 欄. qi2 期. tuo2 坨. zhi3 紙. bu4 部. dui4 隊. ji4 記. li4 粒. qi3 起. wan1 彎. zhou2 軸. cai2 槽. dui4 對. ji4 劑. lian2 聯. qu3 曲. wan1 灣. zhu1 株. ce4 冊. duo3 朵. jia1 家. liang4 輛. quan1 圈. wan2 丸. zhu4 柱. ceng2 層. fa1 發. jia4 架. lie4 列. que4 闋. wei3 尾. zhu4 炷. chong2 重. fang1 方. jian1 間. liu3 綹. qun2 群. wei4 位. zhuo1 桌. chu4 處. fang2 房. jian4 件. lu4 路. shan4 扇. wei4 味. zong1 宗. chuan4 串. fen4 分. jie1 階. lun2 輪. shen1 身. xi2 席. zu3 組. chuang2 床. fen4 份. jie2 節. luo4 落. sheng1 聲. xi2 襲. zun1 尊. chuang2 幢. feng1 封. jie2 截. lyu3 旅. shou3 首. xian4 線. zuo4 座. io. ba3 把. hao4 號. al. ke1 顆. pi3 匹. tao4 套. zhao1 招. ke4 客. pian1 篇. ti2 題. zhen1 針. ke4 課. pian4 片. er. hang2 行. sit. Nat. Table 4: The 173 Classifiers Proposed by Huang et. al. (1997). n. v 條 tiao2 i n C hkou3 口 piao4 票U tie4 帖 hui2 回 engchi hu4 戶. zheng4 幀 zhi1 支.

(24) 14 cong2 叢. fu2 服. jie4 介. lyu3 縷. shu4 束. xiang4 項. cu4 簇. fu2 幅. jin4 進. mei2 枚. shuang1 雙. ye4 頁. cuo1 撮. fu4 副. jing1 莖. men2 門. si1 絲. ye4 葉. da3 打. gan3 桿. ju4 句. mian4 面. sou1 艘. yuan2 員. dai4 代. gen1 根. ju4 具. ming2 名. suo3 所. ze2 則. dai4 帶. ge 個. juan3 卷. pai2 排. tai1 胎. zha1 紮. dang3 檔. gu3 股. juan4 卷. peng3 捧. tai2 台. zhan3 盞. dao4 道. gua4 掛. ke1 科. pi1 匹. tan1 攤. zhang1 張. di1 滴. guan3 管. ke1 棵. pi1 批. tang2 堂. zhang1 章. 2.2.5 Gao and Malt (2009) Gao and Malt (2009), who lately provide Mandarin Chinese classifier. 政 治 大 categorizations, compile a list of one hundred and twenty-six classifiers in order to 立. ‧ 國. 學. provide a basis for their studies and to serve as a resource for future research. Although several Chinese classifier dictionaries have been published, Gao and Malt. ‧. sit. y. Nat. (2009) claim that their list has some advantages. For instance, Gao and Malt (2009). n. al. er. io. claim that they only include individual classifiers in this list and that they only list. i n U. v. classifiers which are familiar to speakers of Chinese. The sources of these classifiers. Ch. engchi. are also very wide-ranging, from Chinese books, newspapers, and dictionaries to casual conversations between Gao and Malt and the other native Chinese speakers and their own knowledge of Chinese. Gao and Malt (2009) mention that these one hundred twenty-six classifiers are approved not only by themselves but also by six paid native speakers of Mandarin Chinese from Beijing (three graduate students at Lehigh University and three college-educated spouses of graduate students). As a result, Gao and Malt (2009) think that these one hundred twenty-six classifiers as.

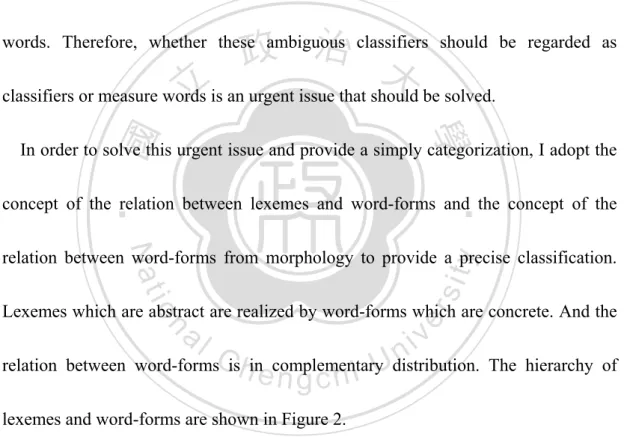

(25) 15. shown below are quite accurate classifiers. Table 5: The 126 Classifiers Proposed by Gao and Malt (2009) ben3 本. dong4 洞. ji2 集. liang4 輛. qi2 期. tang2 堂. ye4 頁. ba3 把. dong4 棟. ji4 劑. liu3 綹. qi3 起. tang4 趟. ze2 則. ban1 班. du3 堵. jia1 家. long3 壟. qiang1 腔. tiao2 條. zhan3 盞. ban4 瓣. duan4 段. jia4 架. lü3 縷. qu3 曲. tie4 帖. zhan4 站. bi3 筆. dui4 對. jia4 駕. lun2 輪. quan1 圈. ting3 挺. zhang1 張. bian4 辮. dun4 頓. jian1 間. ma3 碼. ren4 任. tou2 頭. zhang1 章. bu4 部. duo3 朵. jian4 件. mei2 枚. sao1 艘. tuan2 團. zhao1 招. ce4 冊. fa1 發. jie2 節. men2 門. shan4 扇. tuo2 坨. zhen4 陣. chang3 場. fen4 份. jie2 截. mian4 面. shen1 身. wan2 丸. zhi1 支. chu1 齣. feng1 封. jie4 屆. ming2 名. sheng1 聲. wei4 位. zhi1 枝. chu4 處. fu2 幅. ju4 句. mu4 幕. shou3 首. wei4 味. zhi1 隻. chuang2 床. gan3 桿. ju4 具. pan2 盤. shu4 束. wo1 窩. zhou2 軸. chuang2 幢. gen1 根. juan4 卷. pao4 泡. si1 絲. xi2 席. zhu1 株. cuo1 撮. ge 個. ke1 棵. pi1 匹. suo1 梭. xian4 線. zhuang1 樁. dao4 道. gu3 股. ke1 顆. pian1 篇. suo3 所. xiang4 項. zhuo1 桌. di1 滴. gua4 掛. kou3 口. pian4 片. tai1 胎. xing1 星. zong1 宗. dian3 點. guan3 管. kuai4 塊. pie3 撇. tai2 台. ya2 牙. zun1 尊. ding3 頂. hu4 戶. li4 粒. qi2 畦. tan1 灘. yan3 眼. y. sit. zuo4 座. er. io. al. ‧. Nat. 2.3 Remark. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. n. v i n C h in Section 2.1.1, On the basis of previous studies e n g c h i U I conclude that there are two. views to support the recent view that there needs to be a differentatiation between classifiers and measure words. One view is from the set theory. Her (2011b) mentions that classifiers do not contribute any semantic value that the noun has already possessed to the semantics of the overall [Number C Noun] phrase. For example, yi1 wei3 yu2 一尾魚 provided by Her (2011b). The classifier wei3 尾 will not contribute the ‘tail’ value to yu2 魚 because having a tail is part of what necessarily makes a fish. On the other hand, Her (2011b) claims that measure words.

(26) 16. do contribute semantic value that the noun does not possess to the semantics of the overall [Number C Noun] phrase. For example, yi1 xiang1 yu2 一箱魚. The measure word xiang1 箱 will contribute ‘box’ value to yu2 魚 because xiang1 箱 will furnish additional information to the phrase, indicating that the fish are inside the box and mass boxful quantity. The other view is from Her’s (2010, 2011b) yi-multiplier, a mathematic formula which can be used to differentiate classifiers and measure words.. 政 治 大. Her (2010, 2011b) proposes that classifiers are the multiplier 1 and 1 only. For. 立. example, the classifier wei3 尾 is the multiplier 1 and 1 only. Thus, yi1 wei3 yu2 一. ‧ 國. 學. 尾魚 will be equal to 1 × 1 yu2 魚, which means one fish. Otherwise, measure. ‧. words are other infinite possible values. For example, the measure word da3 打 is. Nat. io. sit. y. the multiplier 12, rather than 1. Thus, yi1 da3 dan4 一打蛋 is equal to 1 × 12 dan4. al. er. 蛋, which means twelve eggs. The details of Her’s mathematic formula about the. n. v i n C h and measure words differentiation between classifiers e n g c h i U will be discussed in Section 3.4. According to the above two views, I thus adopt differentiable concept of classifiers and measure words in this thesis and focus on classifiers. In Section 2.1.2, there are also two aspects to note. First, although Tai (1992) notes that ambiguous classifiers like ba3 把 and kuai4 塊 can also be measure words, he does not provide any precise classification to show how these ambiguous classifiers should be regarded as classifiers or measure words. Thus, I will provide my solution to these ambiguous classifiers from morphology in the following Section 4.1. Second,.

(27) 17. Ahren and Huang (1996) and Huang and Ahren (2003) propose that classifiers can be further divided into three subcategories, namely individual classifiers, event classifiers and kind classifiers. These three subcategories are under the classifiers system. However, a question arises, should these event classifiers and kind classifiers be regarded as classifiers? Because some studies from whom I have adopted Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations in this thesis such as Chao (1968),. 政 治 大. Erbaugh (1986), Hu (1993) and Gao and Malt (2009) do not include kind classifiers. 立. into their classifier categories. But, event classifiers are included into classifier. ‧ 國. 學. categories of Chao (1968) and of Gao and Malt (2009). Thus, my hypothesis to the. ‧. above question is that kind classifiers should not be treated as classifiers and that it is. Nat. io. al. er. further evidence to support this hypothesis will be offered.. sit. y. possible for event classifiers to be classified as classifiers. In Section 4.1.4, the. n. v i n C h thing is slove theU discrepancy of the number of Ultimately, the most important engchi. Mandarin Chinese classifiers. For example, fifty-one classifiers are given in Chao (1968), twenty-two in Erbaugh (1986), one hundred and seventy-three in Huang et. al. and one hundred and twenty-six in Gao and Malt (2009). The reason for these descrepancies results the lack of consentient norms in classifying Mandarin Chinese classifiers. Thus, I will adopt the four tests introduced in Chapter 3 to re-classify Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations (Chao 1968, Erbaugh 1986, Hu 1993, Huang et. al 1997 and Gao and Malt 2009) in Chapter 4..

(28) 18. In the following chapters, the theoretical frameworks of this thesis will be introduced. Chapter 4 provides the data analysis of Mandarin Chinese classifier categorizations. Chapter 5 provides a short summary and indicates further points for further study in the future.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(29) 19. CHAPTER III THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS. Two well-known syntactic tests, adjective insertion and de-insertion have been. 政 治 大. used to differentiate the distinction between classifiers and measure words. In light of. 立. the on-going controversies over both tests, Her (2010) demonstrates that both tests. ‧ 國. 學. can be made much more accurate and reliable. Below more accurate adjective. ‧. insertion and de-insertion will be briefly introduced. In addition to the above two. Nat. io. sit. y. tests, two other tests will also be adopted. Altogether four tests, numeral/adjectival. al. er. stacking (Her and Hsieh 2010, Her 2011b), revised de-insertion (Her and Hsieh. n. v i n 2010), ge-substitution (Tai andCWang Tai 1994) and yi-multiplier Her (2010, h e 1990 n g and chi U 2011b), are used in this thesis to differentiate classifiers from measure words. These four tests will be successively introduced in this section. Finally, some remarks will be made to sum up the content of this section.. 3.1 Numeral/adjectival stacking According to Liang (2006), Mandarin Chinese measure words can be inserted and modified by an adjective while Mandarin Chinese classifiers can not, as shown in (3).

(30) 20. and (4), respectively. (3) 一. 小. 箱. 書. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (8)). yi1 xiao3 xiang1 shu1 one small. box. book. ‘one small box of books’ (4) *一. 小. 隻. yi1 xiao3 zhi1. gou3. C4. one small. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (9)). 狗. dog. 政 治 大. Although this test is confirmed by some linguists, many counter-examples to this. 立. test are found. For example, Her and Hsieh (2010) find numerous [Adj-C] examples. ‧ 國. 學. from Google searches in the Taiwan domain as shown in (5a) and (5b), respectively. 蘋果. da4. ke1. ping2guo3. al. n. ‘one big apple’. apple. er. C. io. one big. b. 一. sit. 顆. y. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (10a)). 大. Nat. yi1. ‧. (5) a. 一. i n U. v. C h(Her and Hsieh 2010, (10b)) engchi. 大. 本. 書. yi1. da4. ben3. shu1. one. big. C. book. ‘one big book Although the above examples represent that the adjective insertion test is unreliable, Her and Hsieh (2010) and Her (2011b) note crucial differences between classifiers and measure words.. 4. Note that C refers to classifiers only throughout this thesis..

(31) 21. Her (2011b) proposes that the first observation relates to the scope of the numeral. Her and Hsieh (2010) point out that the pre-classifier numeral quantifies the noun together with the classifier, while a pre-measure word numeral only quantifies the measure word itself, not the noun. In the following examples, Her and Hsieh (2010) apply numeral quantification in pre-measure, as well as pre-classifier positions, as in (6a), or the stacking of measure words, as in (6b). Her (2011b) points out that these. 政 治 大. two phrases acceptable because the numeral that quantifies the measure words has its. 立. scope blocked by the measure words. Nevertheless, the reverse cases as in (7a) and. ‧ 國. 學. (7b) are totally ill-formed because Her (2011b) points out that numeral that. ‧. quantifies the classifiers must also quantify the measure words, thus yielding a. Nat. sit. 十. er. io. (6) a. 一 箱. al. n. example (7b).. y. nonsensical reading. For example, it can not be one and ten packs at the same time in. v i n 顆C 蘋果 and Hsieh 2010, (11a)) h e n g c(Her hi U. yi1 xiang1. shi2 ke1. ping2guo3. one box. ten. apple. C. ‘one box of ten apples’ b. 一. 箱. 十. 包. 蘋果. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (11b)). yi1 xiang1 shi2 bao1. ping2guo3. one. apple. box. ten. pack. ‘one box of ten packs of apples’ (7) *a. 一 個 yi1 ge. 十. 顆. 蘋果. shi2 ke1 ping2guo3. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (12a)).

(32) 22. one. C. ten. C. apple. *b. 一. 個. 十. yi1. ge. shi2 bao1. ping2guo3. one. C. ten. apple. 包. pack. 蘋果. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (12b)). A formula for the first observation proposed by Her (2011b) is shown in (8). (8) Classifiers / Measure words Distinction in Numeral Quantification Scope If [Num5 X Num Y Noun] is well-formed, then X = M6, X ≠ C, and Y = C/M. Her (2011b) proposes that the second observation relates to the scope of the. 治 政 modification of adjectival. Three forms of adjectival大 modification, [Num – Adj – C/ 立 ‧ 國. 學. M Noun], [Adj – C/ M – de – Noun] and [Adj – Adj – de – Noun], are included in this observation. Following, examples of these three forms will be demonstrated. ‧. individually. First, Her and Hsieh (2010) provide the main concept in the second. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. observation that the adjectival modification of a pre-measure word has only the. i n U. v. measure word as its scope, while a pre-classifier adjective transcends the classifier to. Ch. engchi. modify the noun and allows the scope of a pre-classifier adjective to cover nouns. The first form [Num – Adj – C/ M Noun] of adjectival modification is shown in (9a) and (9b) provided in Her and Hsieh (2010). Example (9b) shows that a pre-classifier adjective transcends the classifier to modify the noun and allows the scope of a pre-classifier adjective to cover the noun; while example (9a) shows that measure words do not behave in this way.. 5 6. Note that Num refers to cardinal numerals only throughout this thesis. Note that M refers to measure words only throughout this thesis..

(33) 23. (9) a. 一. 大. 箱. ≠一. 蘋果. 箱. 大. 蘋果. yi1 da4. xiang1 ping2guo3. yi1 xiang1 da4. ping2guo3. one big. box. one box. apple. apple. ‘one big box of apples’ b. 一. 大. 顆. big. ‘one box of big apples’. 蘋果. = 一. 顆. 大. 蘋果. yi1. da4 ke1 ping2guo3. yi1. ke1 da4 ping2guo3. one. big. one. C. C. apple. ‘one big apple’. big. apple. ‘one big apple’. 政 治 大. The second form of [Adj – C/ M – de – Noun] of adjectival modification is shown. 立. in (10a) and (10b). Example (10a) shows that a pre-classifier adjective transcends the. ‧ 國. 學. classifier to modify the noun and allows the scope of a pre-classifier adjective to. ke1. de. big. C. DE. = 大. sit. da4. 蘋果. 蘋果. er. io. 的. ‘big apple(s)’ b. 大. (Her 2011, (8a)). aping2guo3 da4 ping2guo3 i v l C hengchi Un apple big apple. n. 顆. y. Nat. way. (10) a. 大. ‧. cover the noun; while example (10b) shows that measure words do not behave in this. ‘big apple(s)’ ≠ 大. 箱. 的. 蘋果. da4. xiang1. de. ping2guo3. da4. ping2guo3. big. box. DE. apple. big. apple. ‘apples that come in big boxes’. 蘋果. (Her 2011, (9a)). ‘big apple(s)’. The third form of [Adj – Adj – de – Num – C / M –Noun] in adjectival modification is shown in (11a) and (11b) provided by Her (2011b). Example (11a) shows that a pre-classifier adjective transcends the classifier to modify the noun and.

(34) 24. allows the scope of a pre-classifier adjective to cover the noun; while example (11b) shows that measure words do not behave in this way. (11) a. 大大的. 一. 顆. 蘋果. = 一. 顆. 大. 蘋果. da4da4de. yi1 ke1 ping2guo3. yi1 ke1 da4 ping2guo3. big. one. one. C. apple. ‘one big apple’ b. 大大的. big. apple. ‘one big apple’. 一. 箱. 蘋果. da4da4de yi1. xiang1. ping2guo3. big. box. one. C. 立. ≠ 一 yi1. 箱. 大. 蘋果. xiang1. da4. ping2guo3. big. apple. 治 one box 政 apple 大. ‘one big box of apples’. ‘one box of big apples’. ‧ 國. 學. A formula for the second observation proposed by Her (2011b) is shown in (12).. ‧. (12) C/M Distinction in Adjectival Modification Scope. y. Nat. If [Num A-X N] = [Num X A-N], [A-X-de N] = [A-N], or [AA-de Num X N]. al. er. io. sit. = [Num X A-N], semantically and A refers to size, then X = C, and X ≠ M.. n. Her (2011b) proposes that the last observation comes from the inferences of the. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. above formula (12). Her (2011b) claims that whether the adjective modifies classifiers or nouns, they all have the same scope. Her (2010) thinks that a pre-classifier adjective and a pre-noun adjective in the same phrase can not contradict each other, as shown in (13); while it is totally fine for a pre-measure word to contradict a pre-noun adjective, as shown in (14). (13)*a. 一. 大. 顆. 小. 蘋果. yi1. da4. ke1. xiao3 ping2guo3. one. big. C. small apple. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (15a)).

(35) 25. *b. 大大的. 一. 顆. 小. da4da4de yi1. ke1. xiao3. ping2guo3. big. C. small. apple. (14) a. 一. one 大. 箱 小. 蘋果. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (15b)). (Her and Hsieh 2010, (14a)). 蘋果. yi1 da4 xiang1 xiao3 ping2guo3 one. big. box. small. apple. ‘one big box of red/small apples’ b. 大大的. 一. 箱. 小. da4da4de. yi1. xiang1. big. one. 立. box. 蘋果. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (14b)). xiao3 ping2guo3 政 治 大 small apple. ‘one big box of red/small apples’. ‧ 國. 學. Her (2011b) points out that example (13) does not have a congruent reading. ‧. because apples can not be big and small at the same time. However, the example in. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. (14) can have a congruent reading because the box can be big and the apples small at. n. the same time. A formula for the last observation proposed by Her (2011b) is shown in (15).. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. (15) C/M Distinction in Antonym Stacking Given antonyms A1 and A2, if [Num A1 X A2 N] is semantically incongruent, then X = C and X ≠ M; otherwise, X = M and X ≠ C Finally, more accurate adjective insertion is revised as numeral/adjectival stacking including three subtests, C/M distinction in numeral quantification scope, C/M distinction in adjectival modification scope and C/M distinction in antonym stacking..

(36) 26. 3.2 De-insertion Many linguists claim that de-insertion is a further piece of evidence for the distinction between classifiers and measure words (e.g., Chao 1968, Tai and Wang 1990, Tai 1994). De may be optionally inserted after measure words, but not after classifiers, as shown in (16). (16) 一 箱/*本. 的. 書. yi1 xiang1/ben3. de. shu1. one box/C. DE book. 立. (Her and Hiesh 2010, (16) ). 政 治 大. ‘one box of/*C books’. ‧ 國. 學. However, M. Hsieh (2008) points out that there are many well-formed. y de. ya1zi. DE. duck. sit. 鴨子. (Her and Hiesh 2010, (17) ). n. al. 的. er. 隻. io. (17) 五百萬. Nat. and (18).. ‧. classifier-de-noun examples in the Sinica Corpus as in the following examples of (17). wu3bai3wan4. zhi1. five-million. C. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. ‘five million ducks’ (18) 幾百. 條. 的. 海蛇. (Her and Hiesh 2010, (18) ). ji3bai3. tiao2 de hai3she2. several-hundred. C. DE. sea-snake. ‘hundreds of sea snakes’ An explanation that is attempted for the above examples is N. Zhang’s (2009) corroboration that in a [Number – classifier – de - noun] phrase, the lower the.

(37) 27. number, the less acceptable the phrase. Thus, the higher the number, the more naturally de intervenes between classifiers and nouns. However, Her and Hsieh (2010) indicate that if we apply the fractions of a number including those with a value smaller than one to [Number–classifier–de–noun], it will drastically increase acceptability. And they point out that there are seventy instances of 之一顆的 zhi1 yi1 ke1 de ‘one fraction of’ found in Google searches, as. 政 治 大 的 高麗菜 (Her and Hsieh 2010, 21 (a)). shown in (19). 顆 立. (19) a. 八分之一. ‧ 國. one-eighth. gao1li4cai4. 學. ba1fen1zhi1yi1 ke1 de. C DE cabbage. ‧. ‘one-eighth (of a ) cabbage’ 洋蔥. ke1 de yang2cong1. one-eighth. aCl. io. si4fen1zhi1yi1. (Her and Hsieh 2010, 21 (b)). n. DE onion. Ch. ‘one-eighth (of an) onion’. engchi. y. 的. sit. 顆. er. Nat. b. 四分之一. i n U. v. One explanation that is attempted for the above examples (19a) and (19b) is given by Tang (2005:444), where numeral contrast is interpreted as a contrast in ‘information weight’, the higher the number in [Number – classifier – de – noun], the higher its information weight. However, Her and Hsieh (2010) provide another opinion that the higher the degrees of the computational complexity of the modifications before the classifiers are, the heavier the modifications are and the more acceptable the de-insertion.

(38) 28. phrases are. In other words, any increase in the complexity of a classifier should increase the acceptability of de-insertion. In the following example (20) provided by Her and Hsieh (2010), they say that ban4 半 is computationally more complex than yi1 一, so the degree of acceptability of ban4 ke1 de ping2guo3 半顆的蘋果 is higher than that of yi1 ke1 de ping2guo3 一顆的蘋果. But, if we use the method of ‘information weight’, the degree of acceptability of yi1 ke1 de ping2guo3 一顆的蘋. 政 治 大. 果 is higher than that of ban4 ke1 de ping2guo3 半顆的蘋果 because yi1 一 is. 立. heavier than ban4 半.. ‧ 國. 學. However, Her and Hsieh (2010) provide Google matches data7 , with twenty. ‧. matches of ban4 ke1 de ping2guo3 半顆的蘋果 and merely one of yi1 ke1 de. Nat. n. al. (20) a. 半. er. io. computational complexity.. sit. y. ping2guo3 一顆的蘋果, to further support the correctness of the argumentations of. v i n 蘋果 (Her and Hsieh 2010, 22(a)) Ch engchi U. 顆. 的. ban4. ke1. de. half. C. DE apple. ping2guo3. ‘half an apple’ *b. 一. 顆. 的. 蘋果. yi1. ke1. de. ping2guo3. one. C. DE. (Her and Hsieh 2010, 22 (b)). apple. ‘an apple’ (21) a. 一. 7. 大. 條. 的. 魚. (Her and Hsieh 2010, 23 (a)). Data accessed on February 22, 2010 in Her and Hsieh (2010)..

(39) 29. yi1 da4 tiao2 one. big. C. de. yu2. DE. fish. ‘one big fish’ *b. 一. (Her and Hsieh 2010, 23 (b)). 條. 的. 魚. yi1. tiao2. de. yu2. one. C. DE. fish. ‘one fish’ Example (21) shows that the modification da4 大 increases the complexity of. 政 治 大. classifier itself which is also equal to increase the acceptability of de-insertion. Thus,. 立. the degree of acceptability of yi1 da4 tiao2 de yu2 一大條的魚 is higher than that of. ‧ 國. 學. yi1 tiao2 de yu2 一條的魚.. ‧. In conclusion, Her and Hsieh (2010) assume that one is computationally the least. y. Nat. al. n. more restricted terms and with much more precision. (22)De-insertion (revised). Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. complex number. They thus restate the test of de-insertion as shown in (22) in much. i n U. v. [yi M/*C de Noun]. 3.3 Ge-substitution Tai and Wang (1990) and Tai (1994) propose that if ge 個, the neutral individual classifier, can definitely substitute the element without any changes in its truth conditions, then the element is a classifier rather than a measure word. Consider the following examples: (23) 三. 顆. 蘋果. =. 三. 個. 蘋果. (Her and Hsieh 2010, (24)).

(40) 30. san1. ke1. ping2guo3. san1. ge. ping2guo3. three. C. apple. three. C. apple. ‘three apples’ (24) 三 san1. ‘three apples’ ≠ 三. 蘋果. xiang1. ping2guo3. san1 ge. ping2guo3. apple. three C. apple. three box. ‘three boxes of apples’. 個. 蘋果 (Her and Hsieh 2010, (25)). 箱. ‘three apples’. Example (23) illustrates that ke1 顆 is a classifier because ke1 顆 can be replaced. 政 治 大. by ge 個 without any change in the numeral meaning of the apple, while (24) shows. 立. that xiang1 箱 should be categorized as a measure word because xiang1 箱 can not. ‧ 國. 學. be replaced by the neutral individual classifier ge 個. As a result, Tai and Wang (1990). ‧. and Tai (1994) suggest that classifiers and measure words can be distinguished by. er. io. sit. y. Nat. ge-substitution.. But not all classifiers can be replaced by ge 個. For instance, Hsieh (2009). n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. mentions that ben3 本 ‘a unit used for books’ is typically regarded as a classifier, as in the case of yi1 ben3 shu1 一本書, but that the substituted form ? yi1 ge shu1 一個. 書 is not acceptable at all. And other examples that I have found, such as yi1 gen1 dao4cai3 一根稻草 will not be acceptable if we substitute ge 個 for their specific individual classifier, such as ? yi1 ge dao4cai3 一個稻草. Thus, words that can be substituted for ge 個 are certain to be classifiers but not all classifiers can be substituted for ge 個 . In other words, ge-substitution is a sufficient but not a.

(41) 31. necessary factor to distinguish classifiers from measure words. The following is a ge-substitution formula postulated by Her and Hsieh (2010) to distinguish classifiers from measure words. (25)Ge-substitution If [Num X Noun] = [Num ge Noun] semantically, then X = C and X ≠ M.. 3.4 Yi – Multiplier In supposing that coding of the operation of multiplication in language is. 治 政 necessary, Her (2011b) thinks that Au Yeung (2005,大 2007) makes a convincing case 立 ‧ 國. 學. for the essential role of the multiplicative identity, 1, in the emergence of classifiers. Her (2011b) points out that in the number calling system of both Chinese and. ‧. 百. 四. wu3 bai3 si4. n. al. Ch. 十. (Her 2011b, (50)). 三. shi2 san1. six thousand five hundred four ten three. engchi. sit. io. liu4 qian1. 五. er. 千. Nat. (26) 六. y. English, all multipliers above the ten are called. Take the number 6543 for example.. i n U. v. ‘Six thousand five hundred and forty-three’. While, as Comrie (2006) points out, Chinese numbers are famously regular in their decimal pattern, (n × base) + m, where m < base, Her (2011b) mentions that the number 6543 can be derived as shown in (27) and (28). (27) Derivation of the number 6543 in Chinese (I). (Her 2011b, (51)). (6 × 103) + (5 × 102) + (4 × 101) + (3 × 100) (28) Derivation of the number 6543 in Chinese (II) (6 × 1000) + (5 × 100) + (4 × 10) + (3 × 1). (Her 2011b, (52)).

(42) 32. Her (2011b) points out that the multiplication, that is symbol ×, and addition, symbol +, in examples (27) and (28) is not pronounced, but that all of the bases, such as qian1 ‘thousand’ (103), bai3 ‘hundred’ (102), and shi2 ‘ten’ (101) must be. Only, ge (100) will be viewed as a exception as a base but without pronunciation. Such an asymmetry between the rightmost digits such as ge and other digits such as qian1, bai3, and shi2 has been noted by Au Yeung (2005). Au Yeung (2005) points out that. 政 治 大. the only phonetically null but numerically present slot is ge when a number is called. 立. in Chinese as shown in Table 6. The single digit 3 in Table 6 is equal to 3 × ge that ge. ‧ 國. 學. is bound to appear but without pronunciation. Because ge is bound to appear and 3 ×. ‧. ge is equal to 3, the only possible multiplier for ge is the multiplier 1. The single digit. Nat. io. al. er. null, ge is marked as silent to represent phonetically null.. sit. y. 3 is thus represented by the multiplication formula as 3×1. Because ge is phonetically. n. v i n C h Digit (Her 2011b, Table 6: Asymmetry of the Rightmost Table 1) U i e h ngc 4 Number 6543 6 5 3 Position Naming Digit Value Calling Number Calling. 千位 百位 十位 個位 Qian1-we4i Bai3-wei4 Shi2-wei4 Ge-wei4 Liu6-qian1 Wu3-bai3 Si4-shi2 San1- GEsilent 六 千 五 百 四 十 三 (*個) (5 bai3) (4 shi2) (3 × ge) (6 qian1) Liu4 qian1 wu3 bai3 si4 shi2 san1 GEsilent. As a result, Au Yeung (2005: 201) points out: “The silent classifier in the form of 1GE in the CL slot could serve as a seed for the noisy sortal classifier to grow”.8 However, Her (2011b) mentions that Au Yeung (2005) does not follow his simple mathematical 8. Note that Au Yeung (2007) does not differentiate classifiers from measure words and uses ‘classifiers’ to include both of them. However, Au Yeung (2005) does differentiate classifiers which are called as sortal classifiers in his terminology from measure words which are called non-sortal classifiers in his terminology..

(43) 33. value of ge as classifiers, which is quite simply the multiplier 1. Instead, Her (2011b) points out that Au Yeung pursues a more complicated formula and takes a classifier as having a numerical value ‘one tokenobject per unit’ and a measure word as ‘n tokenobject per unit’. Au Yeung (2007) further interprets ‘tokenobject’ as the size of the ‘unit’, or the set.. (1× 1set) in example (29) and (2× 1set) in example (30) are demonstrations of ‘one tokenobject per unit’ and ‘n tokenobject per unit’, respectively.. (29) 三. (Her 2011b (53)). 個. 球. san1. ge. qiu2 (3×(1× 1set)×qiu2). three. C. ball. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‘three balls’. pair. qiu2 (3×(2× 1set)×qiu). Nat. three. ‧. san1 dui4. (Her 2011b (54)). 球. y. 對. ball. sit. (30) 三. n. al. er. io. ‘three pairs of balls’. Ch. i n U. v. From the above two examples and the ‘one tokenobject per unit’ and ‘n tokenobject per. engchi. unit’ concepts, Her (2011b) proposes that Au Yeung’s distinction between classifiers. and measure words rests on the value of n. If n is equal to 1, it is a classifier. If n is not equal to 1, it is a measure word. Au Yeung’s formula of is shown below. (31) Au Yeung’s (2005, 2007) Formula (Her 2011b (55)) [Num X Noun] = [Num × (n× 1set) ×Noun], where X=C if n=1 and X=M if n≠1 Although Au Yeung (2005, 2007) is possibly the first researcher to make the above clear and mathematically precise distinction between classifiers and measure.

(44) 34. words, Her (2011b) further provides a simpler proposal of Au Yeung’s (2005, 2007) formula. Her (2010) proposes that if a classifier or a measure word is interpreted as having a mathematical value, then the only possible mathematical function is multiplication linking between numeral and classifiers or measure words. Simplifying Au Yeung’s formula, Her (2010) proposes that classifiers represents necessarily multiplier 1 and. 政 治 大. 1 only while measure words represents other than 1. The precise and simplier. 立. distinction for distinguishing between classifiers and measure words of Her (2010) is. ‧ 國. 學. given as (32).. ‧. (32)Her’s (2010) Yi-multiplier Formula. sit. y. Nat. [Num X Noun] = [Num×n Noun], where X=C iff n=1, otherwise X=M.. io. n. al. er. Finally, Her (2011b) mentions that many classifiers in Chinese are all of the same. i n U. v. mathematical value which is multiplier 1 and that measure words are the other infinite possible values.. Ch. engchi. 3.5 Remark Theories to differentiate classifiers from measure words have been outlined in this section. Numeral/adjectival stacking is not a perfect way to differentiate classifiers and measure words because there are many variables. For example, a Mandarin Chinese classifier feng1 封. Under the scope of numeral modification, yi1 xiang1 shi2 feng1 xin4 一箱十封信 is acceptable, but under the scope of adjectival.

(45) 35. modification yi1 da4 feng1 xin4 一大封信 is semantically doubtful if it is equal to yi1 feng1 da4 xin4 一封大信 or da4 feng1 de xin4 大封的信 is also semantically doubtful if it is equal to da4 xin4 大信. Or, a Mandarin Chinese classifiers, ju4 具. Under the scope of numeral modification, yi1 xiang1 shi2 ju4 shi1ti3 一箱十具屍體 is acceptable, but under the scope of adjectival modification yi1 da4 ju4 shi1ti3 一大. 具屍體 is semantically doubtful if it is equal to yi1 ju4 da4 shi1ti3 一具大屍體 or. 政 治 大. da4 ju4 de shi1ti3 大具的屍體 is semantically doubtful if it is equal to da4 shi1ti3. 立. 大屍體. The above situations in which classifiers are testified as classifiers in one. ‧ 國. 學. test but where there status is uncertain in others will increase the difficulties and lack. ‧. of accuracy in determining whether a Mandarin Chinese word is classifiers or. Nat. al. er. io. for classifiers and measure words.. sit. y. measure words. Moreover, it is impossible to have a definite dichotomous distinction. n. v i n Although Her (2011b) has C already U of de-insertion, I still found h e revised h idefects n g c the. some counter-examples through Google searches. For example, a classifier jian4 件 is allowed to have de-insertion such as in yi1 jian4 de mao2yi1 一件的毛衣9. A classifier mian4 面 is also allowed to have de-insertion such as in yi1 mian4 de jing4zi 一面的鏡子10.. Though I found some counter-examples through Google. searches, most classifiers are still not allowed to have de-insertion. Words which are not allowed to have de-insertion must be classifiers, while words which are allowed 9 10. Data accessed on June 27, 2011. Data accessed on June 27, 2011..

數據

相關文件

Teachers may consider the school’s aims and conditions or even the language environment to select the most appropriate approach according to students’ need and ability; or develop

好了既然 Z[x] 中的 ideal 不一定是 principle ideal 那麼我們就不能學 Proposition 7.2.11 的方法得到 Z[x] 中的 irreducible element 就是 prime element 了..

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

For pedagogical purposes, let us start consideration from a simple one-dimensional (1D) system, where electrons are confined to a chain parallel to the x axis. As it is well known

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..

• Formation of massive primordial stars as origin of objects in the early universe. • Supernova explosions might be visible to the most

Miroslav Fiedler, Praha, Algebraic connectivity of graphs, Czechoslovak Mathematical Journal 23 (98) 1973,

(Another example of close harmony is the four-bar unaccompanied vocal introduction to “Paperback Writer”, a somewhat later Beatles song.) Overall, Lennon’s and McCartney’s