Open Access

Research

Prescription profile of potentially aristolochic acid containing

Chinese herbal products: an analysis of National Health Insurance

data in Taiwan between 1997 and 2003

Shu-Ching Hsieh

1,2, I-Hsin Lin

3, Wei-Lum Tseng

4, Chang-Hsing Lee

2,5and

Jung-Der Wang*

2,6Address: 1Division of Health Technology Assessment, Center for Drug Evaluation, Taiwan, 2Institute of Occupational Medicine and Industrial

Hygiene, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 3Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of

Health, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan, 4Emergency Department of Taipei City Hospital, Zhongxiao Branch, Taipei, Taiwan, 5Department of

Occupational Medicine, Ton Yen General Hospital, Hsinchu, Taiwan and 6Department of Internal Medicine and the Department of Environmental

and Occupational Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

Email: Shu-Ching Hsieh - schsieh@cde.org.tw; I-Hsin Lin - ihsin@ccmp.gov.tw; Wei-Lum Tseng - tsengweilum@hotmail.com; Chang-Hsing Lee - d95841004@ntu.edu.tw; Jung-Der Wang* - jdwang@ntu.edu.tw

* Corresponding author

Abstract

Background: Some Chinese herbal products (CHPs) may contain aristolochic acid (AA) or may

be adulterated by the herbs suspected of containing AA which is nephrotoxic and carcinogenic. This study aims to identify the risk and the prescription profile of AA-containing CHPs (AA-CHPs) in Taiwan.

Methods: A longitudinal analysis was conducted on a randomly sampled cohort of 200,000

patients using the data from the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan between 1997 and 2003.

Results: During the 7-year study period, 78,644 patients were prescribed with AA-CHPs; most

patients were females, or middle-aged, or both. A total of 526,867 prescriptions were made to use 1,218 licensed AA-CHPs. Over 85% of the AA-exposed patients took less than 60 g of AA-herbs; however, about 7% were exposed to a cumulated dose of over 100 g of Radix et Rhizoma Asari (Xixin), Caulis Akebiae (Mutong) or Fructus Aristolochiae (Madouling). Patients of respiratory and musculoskeletal diseases received most of the AA-CHP prescriptions. The most frequently prescribed AA-CHPs Shujing Huoxie Tang, Chuanqiong Chadiao San and Longdan Xiegan Tang, containing Radix Stephaniae Tetrandrae, Radix et Rhizoma Asari and Caulis Akebiae, respectively.

Conclusion: About one-third of people in Taiwan have been prescribed with AA-CHPs between

1997 and 2003. Although the cumulated doses were not large, further actions should be carried out to ensure the safe use of AA-CHPs.

Published: 23 October 2008

Chinese Medicine 2008, 3:13 doi:10.1186/1749-8546-3-13

Received: 20 February 2008 Accepted: 23 October 2008 This article is available from: http://www.cmjournal.org/content/3/1/13

© 2008 Hsieh et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

Considerable attention to the safe use of Chinese herbal medicines has been drawn since the reports of nephropa-thy due to some Chinese herbs [1,2]. The reported neph-rotoxicity and carcinogenicity of aristolochic acid (AA) was subsequently corroborated by clinical reports [3-9], results from animal models [10-12] and the detection of AA bound DNA adducts in kidney and ureteral tissues [13-16]. These reports led to the prohibition of all AA-containing products in many countries and regions, such as the USA, UK, Canada, Germany, Australia and Taiwan [13,17-20]. The Bureau of Food and Drug Analysis in Tai-wan is mandated to regularly monitor AA-containing Chi-nese herbal products (AA-CHPs) in the market by quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Substitution of specific AA-containing herbs has been reported. Caulis Akebiae (Mutong), Radix Stephaniae

Tetran-drae (Fangji) and Radix Aucklandiae (Muxiang) may

poten-tially be substituted by Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis (Guanmutong) [21], Radix Aristolochiae Fangchi

(Guan-fangji) [22-24] and Radix Aristolochiae (Qingmuxiang)

respectively. Inappropriate uses were reported after the ban had been imposed [18,25-28]. Containing trace amounts of AA [29,30], Radix et Rhizoma Asari (Xixin) is banned [19,31] but still available in Mainland China, Tai-wan, Japan and Korea [32].

The CHPs currently covered by the National Health Insur-ance (NHI) of Taiwan do not include raw herbs. Manufac-tured and marketed as extract products, CHPs are equivalent to the 'finished herbal products' or 'mixed herbal products' as defined by the World Health Organi-zation (WHO) [33]. In terms of safety, AA-CHPs may be quite different from individual AA herbs because tradi-tional Chinese medicine formulae that are used to make AA-CHPs were designed to not only enhance the efficacy of the herbs but also reduce their toxicity [34,35].

This study aims to determine the prescription profile of AA-CHPs in Taiwan based on data for the period between January 1997 and November 2003. The prescription data for 2004 enable us to determine whether the ban on the use of AA herbs was complied with in Taiwan [36] where the high incidence and prevalence rates of chronic kidney disease were associated with the use of herbal medicines [37].

Methods

Selection of herbs

AA-CHPs in this study are defined as the Chinese herbal products that are (1) either suspected of containing AAs (AA herbs), e.g. Herba Aristolochiae (Tianxianteng), Fructus

Aristolochiae (Madouling) and Xixin, or (2) likely to be

adulterated by AA herbs, e.g. Fangji, Muxiang and Mutong.

In Taiwan, the ban on some SAA herbs, including

Guan-fangji, Qingmuxiang, Guanmutong, Madouling, and Tianxi-anteng, took effect on 4 November 2003. However Xixin, Mutong, Fangji and Muxiang, may still be used if correct

species without adulteration or malnomenclature are assured. We therefore examined all the CHPs licensed by the Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy (CCMP) between 1997 and 2003, including single herbs and herbal formulae, to determine whether they include AA herbs. The inclusion period runs from the start of the research database (1 January 1997) to one day prior to the ban on AA-CHPs (3 November 2003). The databases used in this study were also used in similar studies [38,39].

List of licensed Chinese herbal products

The CCMP list shows that 18,019 CHPs were licensed dur-ing the study period, of which 9,837 were covered by the NHI. CHPs in Taiwan can only be prescribed by Chinese medicine practitioners and CHP prescriptions usually contain more than one single herb/herbal formula [38]. For simplicity, all CHPs with the same CCMP standard formulae are classified under the same categories, regard-less of slight variations among products of different phar-maceutical companies [40]. For example, there are 46 approved licenses for the formula Duhuo Jisheng Tang.

National Health Insurance reimbursement database

The NHI covers over 96.16% of the population in Taiwan [41]. Our cohort of 200,000 patients was randomly selected from all NHI beneficiaries, according to the methods of Knuth [42] and Park and Miller [43] using random numbers generated by a program written in Sun WorkShop C 5.0. Under secure encryption, all reimburse-ment data of the cohort from 1996 onwards were col-lected and analyzed. The database contains all transactions of health care services for the cohort, includ-ing both Western medicine and Chinese medicine, with the dates and some details of all outpatient visits, hospi-talization, diagnoses, prescribed CHPs (dosages, dosage frequency and prescription duration) and the personal data of the patients. The database was made available by the National Health Research Institutes in 2002 and was widely used by researchers in various fields [44]. The main datasets used were 'Ambulatory care expenditure by visits', 'Details of ambulatory care orders' and 'Registry for con-tracted medical facilities'. As the NHI of Taiwan does not cover the use of Chinese medicine in inpatient services, we only studied the use of Chinese medicine in outpatient services. Using the data of 2004, we also studied whether Chinese medicine practitioners complied with the ban on AA herbs.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was undertaken by descriptive statistics, including the decomposition of the AA herb contents of

the licensed and prescribed AA-CHP items, AA-CHP pre-scription rates stratified by patient's gender and age, the median (plus 5 and 95 percentiles) of cumulated doses of AA herbs, the population distribution of those who had been potentially exposed to AA herbs at various dosages, the frequencies of the disease categories prescribed with AA-CHPs, the most frequently prescribed herbal formulae potentially containing AA herbs, and the most common duration and dosage frequencies of AA-CHP prescrip-tions. All of the above analyses were performed using the SAS software package (version 9.1, USA).

Results

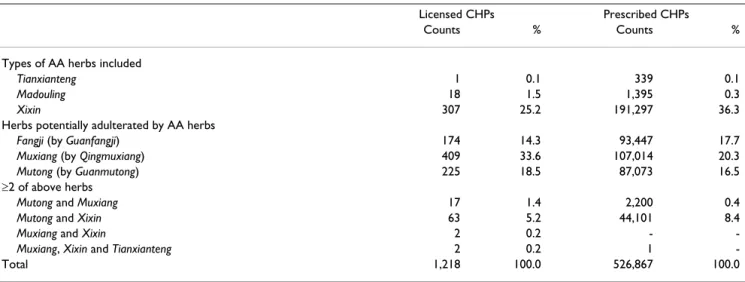

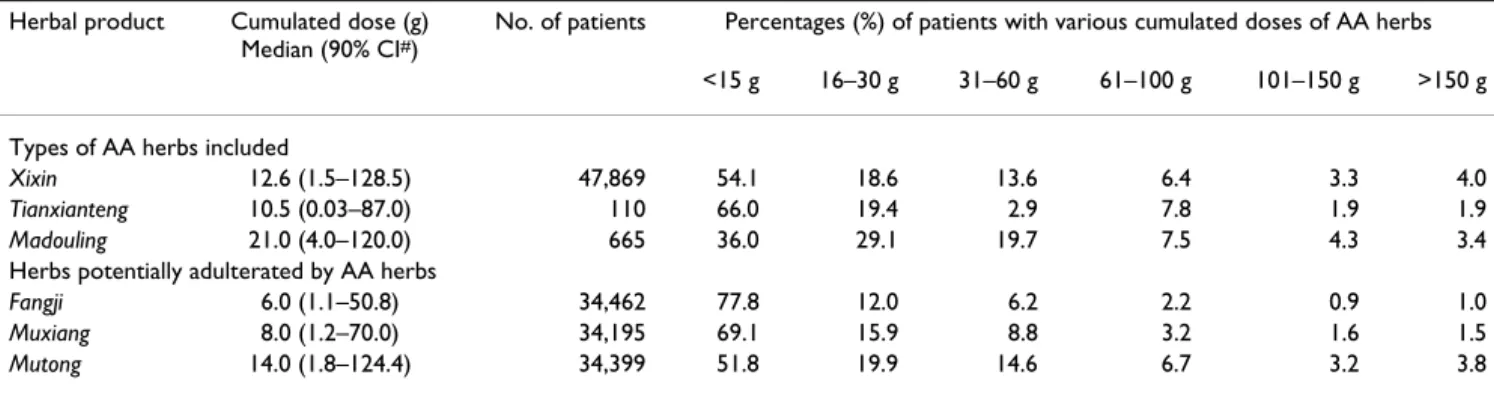

Between 1 January 1997 and 3 November 2003, 1,218 (12.38%) AA-CHPs were identified out of the total of 9,837 licensed CHPs, of which the most frequently pre-scribed were Muxiang (35.3%) and Xixin (30.7%). A total of 526,867 cases of prescribed and reimbursed AA-CHPs were recorded (Table 1). Among all the AA-CHPs, Xixin was the most frequently prescribed (44.7%). The co-exist-ence of more than two AA herbs was identified in both licensed and prescribed AA-CHPs, of which Mutong and

Xixin were the most frequently seen. During the study

period, 105,737 patients (52.9%) sought Chinese medi-cine treatment on at least one occasion, of which 78,644 were prescribed with AA-CHPs. The AA-exposed popula-tion demonstrated the prevalence of middle-aged female patients (Table 2). More than 70% of the patients were exposed to lower cumulated doses (less than 30 mg) of all AA herbs in CHPs; about 7% of the patients were pre-scribed with Xixin, Mutong and Madouling at cumulated doses of over 100 g (Table 3). Given that the random sam-ple of this cohort accounts for approximately 1% of the population of Taiwan, it may be inferred that about

344,300 people were exposed to such high cumulated doses of Xixin, while about 234,700 people were exposed to similarly high cumulated doses of Mutong.

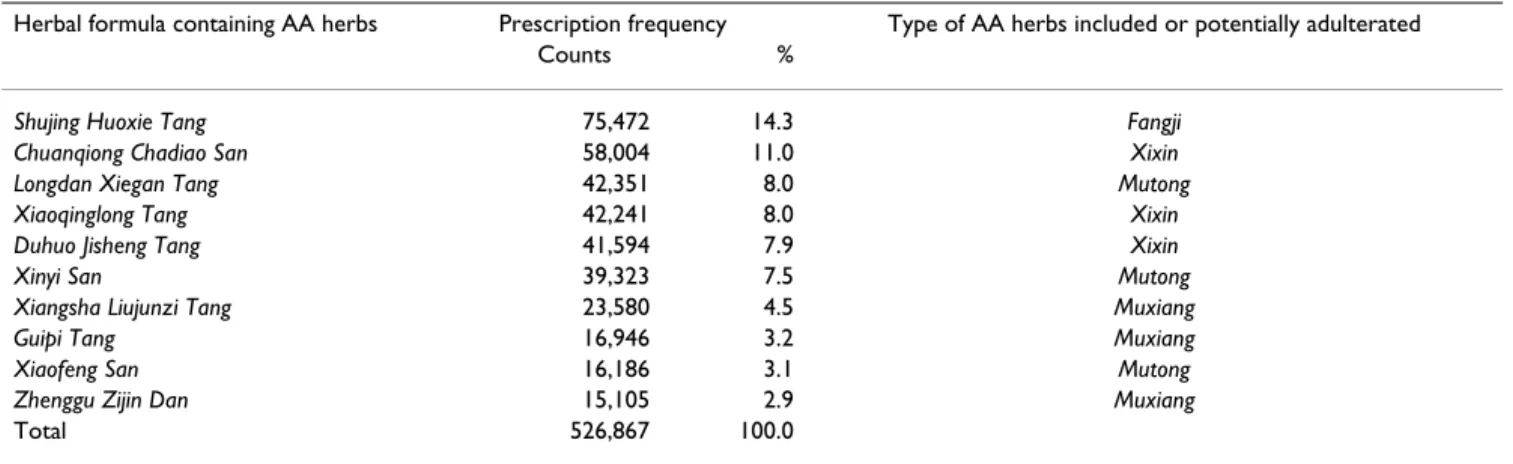

The major disease categories often prescribed with AA-CHPs include respiratory diseases (132,598 visits) and musculoskeletal/connective diseases (77,153 visits), fol-lowed by symptoms/signs/ill-defined conditions (68,466 visits), digestive diseases (46,646 visits) and injury/poi-soning (40,260 visits). Among all AA-CHPs, 90.7% were in the form of herbal formulae, of which the most fre-quently prescribed were Shujing Huoxie Tang (containing

Fangji), Chuanqiong Chadiao San (containing Xixin) and Longdan Xiegan Tang (containing Mutong) (Table 4).

About 97.5% of all AA-CHPs were prescribed for treat-ment of no more than seven days and the most common dosage frequency (82.7%) was three times a day. Further-more, our investigation of the 2004 database found an alarming number of cases of CHPs containing AA herbs (Tianxianteng or Madouling) prescribed after the ban was announced on 4 November 2003. We found a total of 68 records involving the prescription of these herbs to 25 patients by 19 Chinese medicine practitioners (in 19 clin-ics). Therefore, our estimate was that about 2,760 patients (= 25*23,000,000* 96.16%/200,000) were prescribed with the prohibited AA-CHPs at least once during the study period.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that more than one-third (39.3%) of the population in Taiwan were prescribed with AA-CHPs during the study period and that the cumulated doses of AA-CHPs for each patient may have exceeded 100

Table 1: Distribution frequencies of licensed and prescribed Chinese herbal products potentially containing aristolochic acid, 1997– 2003*

Licensed CHPs Prescribed CHPs

Counts % Counts %

Types of AA herbs included

Tianxianteng 1 0.1 339 0.1

Madouling 18 1.5 1,395 0.3

Xixin 307 25.2 191,297 36.3

Herbs potentially adulterated by AA herbs

Fangji (by Guanfangji) 174 14.3 93,447 17.7

Muxiang (by Qingmuxiang) 409 33.6 107,014 20.3

Mutong (by Guanmutong) 225 18.5 87,073 16.5

≥2 of above herbs

Mutong and Muxiang 17 1.4 2,200 0.4

Mutong and Xixin 63 5.2 44,101 8.4

Muxiang and Xixin 2 0.2 -

-Muxiang, Xixin and Tianxianteng 2 0.2 1

-Total 1,218 100.0 526,867 100.0

*The table shows the distribution frequencies of licensed and prescribed Chinese herbal products (CHPs) that may potentially contain aristolochic acid (AA).

g (Table 3). Exposure to Xixin and Mutong was the most extensive. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the use of CHPs. Special attention should be drawn to prescriptions for patients suffering from respiratory and/or muscu-loskeletal diseases and to the herbal formulae with AA herbs (Table 4).

There are a few major limitations to this study. Firstly, the study was based upon the NHI reimbursement data. Spe-cific information is not available for causal studies or inference. Secondly, different pharmaceutical companies may obtain their herbs from different sources which may have different degrees of AA herb adulterations. The esti-mation of cumulated AA doses may be inaccurate. Thirdly, this study did cover the consumption of medici-nal herbs purchased directly from the market. Therefore our estimate does not represent all consumption of AA herbs in Taiwan.

Conclusion

This study showed a prescription profile of AA-CHPs in Taiwan between 1997 and 2003 based on the NHI reim-bursement data, including an estimate of the total amount of AA herbs consumed and the target population requiring continuous monitoring. Moreover, this study revealed the NHI prescription of some banned AA-CHPs.

Abbreviations

AA: aristolochic acid; CHPs: Chinese herbal products; AA-CHPs: CHPs containing AA; NHI: National Health Insur-ance; CCMP: Committee on Chinese Medicine and Phar-macy.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Table 2: Prescription frequencies of Chinese herbal products (by gender, age and types of herbs), 1997–2003*

Herbal products Gender Age (years)

Male Female <12 12–18 19–34 35–59 60–75 ≥76

Any CHPs 35.4 41.8 11.1 7.3 23.6 26.5 7.2 1.6

AA-CHPs 25.9 31.6 6.8 5.8 17.6 20.6 5.6 1.2

Types of AA herbs included

Xixin 14.8 20.2 4.9 3.1 9.8 12.7 3.7 0.8

Madouling 0.2 0.3 0.1 -- 0.1 0.2 0.1

--Tianxianteng -- -- -- -- -- -- --

--Herbs potentially adulterated by AA herbs

Fangji 11.5 13.6 0.8 2.1 7.6 11.0 3.0 0.6

Muxiang 10.3 14.7 2.7 2.5 7.9 9.2 2.2 0.5

Mutong 10.8 14.4 3.3 2.4 7.6 9.2 2.2 0.4

*The prescription frequencies (per 1,000 person-years) of Chinese herbal products (CHPs) are stratified by gender, age and the types of AA containing herbs (AA herbs) or those potentially adulterated by AA herbs.

Table 3: Distribution frequencies* of Chinese herbal product prescriptions potentially containing aristolochic acid (by cumulated doses), 1997–2003

Herbal product Cumulated dose (g) Median (90% CI#)

No. of patients Percentages (%) of patients with various cumulated doses of AA herbs <15 g 16–30 g 31–60 g 61–100 g 101–150 g >150 g Types of AA herbs included

Xixin 12.6 (1.5–128.5) 47,869 54.1 18.6 13.6 6.4 3.3 4.0 Tianxianteng 10.5 (0.03–87.0) 110 66.0 19.4 2.9 7.8 1.9 1.9 Madouling 21.0 (4.0–120.0) 665 36.0 29.1 19.7 7.5 4.3 3.4 Herbs potentially adulterated by AA herbs

Fangji 6.0 (1.1–50.8) 34,462 77.8 12.0 6.2 2.2 0.9 1.0 Muxiang 8.0 (1.2–70.0) 34,195 69.1 15.9 8.8 3.2 1.6 1.5 Mutong 14.0 (1.8–124.4) 34,399 51.8 19.9 14.6 6.7 3.2 3.8 *Distribution frequency refers to the number of patients who have been prescribed with Chinese herbal products that may potentially contain aristolochic acid (AA).

Authors' contributions

SCH conducted the study design, data management, sta-tistical analysis, preparation and revision of the manu-script. IHL contributed to the study design and coordinated the study. WLT and CHL assisted in literature survey and data interpretation. JDW conceived, designed, coordinated the study and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This project was partially supported by the grants from the Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy (CCMP95-TP-016) and the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX96-9204PP). We are also grateful to Drs Jung-Nein Lai, Yao-Hsu Yang and Chien-Tung Wu for their helpful advice about the theory and practice of Chinese medicine.

References

1. Vanherweghem JL, Depierreux M, Tielemans C, Abramowicz D, Dratwa M, Jadoul M, Richard C, Vandervelde D, Verbeelen D, Van-haelen-Fastre R, et al.: Rapidly progressive interstitial renal fibrosis in young women: association with slimming regimen including Chinese herbs. Lancet 1993, 341(8842):387-391. 2. Vanhaelen M, Vanhaelen-Fastre R, But P, Vanherweghem JL:

Identifi-cation of aristolochic acid in Chinese herbs. Lancet 1994, 343(8890):174.

3. Lord GM, Cook T, Arlt VM, Schmeiser HH, Williams G, Pusey CD: Urothelial malignant disease and Chinese herbal nephropa-thy. Lancet 2001, 358(9292):1515-1516.

4. Krumme B, Endmeir R, Vanhaelen M, Walb D: Reversible Fanconi syndrome after ingestion of a Chinese herbal 'remedy' con-taining aristolochic acid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001, 16(2):400-402.

5. Pena JM, Borras M, Ramos J, Montoliu J: Rapidly progressive inter-stitial renal fibrosis due to a chronic intake of a herb (Aris-tolochia pis(Aris-tolochia) infusion. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996, 11(7):1359-1360.

6. Stengel B, Jones E: End-stage renal insufficiency associated with Chinese herbal consumption in France. Nephrologie 1998, 19(1):15-20.

7. Tanaka A, Nishida R, Yoshida T, Koshikawa M, Goto M, Kuwahara T: Outbreak of Chinese herb nephropathy in Japan: are there any differences from Belgium? Intern Med 2001, 40(4):296-300. 8. Chen W, Chen Y, Li A: The clinical and pathological manifesta-tions of aristolochic acid nephropathy – the report of 58 cases. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi 2001, 81(18):1101-1105.

9. Chang CH, Wang YM, Yang AH, Chiang SS: Rapidly progressive interstitial renal fibrosis associated with Chinese herbal medications. Am J Nephrol 2001, 21(6):441-448.

10. Chen L, Mei N, Yao L, Chen T: Mutations induced by carcino-genic doses of aristolochic acid in kidney of Big Blue trans-genic rats. Toxicol Lett 2006, 165(3):250-256.

11. Cosyns JP, Dehoux JP, Guiot Y, Goebbels RM, Robert A, Bernard AM, van Ypersele de Strihou C: Chronic aristolochic acid toxicity in rabbits: a model of Chinese herbs nephropathy? Kidney Int 2001, 59(6):2164-2173.

12. Cui M, Liu ZH, Qiu Q, Li H, Li LS: Tumour induction in rats fol-lowing exposure to short-term high dose aristolochic acid I. Mutagenesis 2005, 20(1):45-49.

13. Arlt VM, Stiborova M, Schmeiser HH: Aristolochic acid as a prob-able human cancer hazard in herbal remedies: a review. Mutagenesis 2002, 17(4):265-277.

14. Cosyns JP: Aristolochic acid and 'Chinese herbs nephropathy': a review of the evidence to date. Drug Saf 2003, 26(1):33-48. 15. Cosyns JP: Human and experimental features of aristolochic

acid nephropathy (AAN; Formally Chinese herbs nephropa-thy-CHN): are they relevant to Balkan endemic nephropath8 (BEN). Medicine and Biology 2002, 9(1):49-52. 16. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Monographs on the

eval-uation of carcinogenic risks to humans – Complete list of agents evaluated and their classification [http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Classification/ index.php].

17. Schwetz BA: From the Food and Drug Administration. JAMA 2001, 285(21):2705.

18. Cheung TP, Xue C, Leung K, Chan K, Li CG: Aristolochic acids detected in some raw Chinese medicinal herbs and manufac-tured herbal products – a consequence of inappropriate nomenclature and imprecise labelling? Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006, 44(4):371-378.

19. Kessler DA: Cancer and herbs. N Engl J Med 2000, 342(23):1742-1743.

20. Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Health Executive Yuan, Taiwan: Regulations on aristolochic acid-con-tained Chinese herbal medicine products [http://www.ccmp.gov.tw/pub lic/public.asp?selno=561&relno=561&level=C].

21. Chuang MS, Hsu YH, Chang HC, Lin JH, Liao CH: Studies on adul-teration and misusage of marketed akebiae caulis. Ann Rept NLFD Taiwan ROC 2002, 20:104-119.

22. Deng JS: Quality evaluation of Fang-Ji and analysis of marker constituents. In PhD thesis Taichung: China Medical University; 2002.

23. Hsu YH, Tseng HH, Wen KC: Determination of aristolochic acid in fangchi radix. Ann Rept NLFD Taiwan ROC 1997, 15:136-142. 24. Tung CF, Ho YL, Tsai HY, Chang YH: Studies on the commonly

misused and adulterated Chinese crude drug species in Tai-wan. Chin Med Coll J 1999, 8(1):35-46.

Table 4: Distribution frequencies* of the most commonly prescribed herbal formulae potentially containing aristolochic acid, 1997– 2003

Herbal formula containing AA herbs Prescription frequency Type of AA herbs included or potentially adulterated

Counts %

Shujing Huoxie Tang 75,472 14.3 Fangji Chuanqiong Chadiao San 58,004 11.0 Xixin Longdan Xiegan Tang 42,351 8.0 Mutong

Xiaoqinglong Tang 42,241 8.0 Xixin

Duhuo Jisheng Tang 41,594 7.9 Xixin

Xinyi San 39,323 7.5 Mutong

Xiangsha Liujunzi Tang 23,580 4.5 Muxiang

Guipi Tang 16,946 3.2 Muxiang

Xiaofeng San 16,186 3.1 Mutong

Zhenggu Zijin Dan 15,105 2.9 Muxiang

Total 526,867 100.0

Publish with BioMed Central and every scientist can read your work free of charge "BioMed Central will be the most significant development for disseminating the results of biomedical researc h in our lifetime."

Sir Paul Nurse, Cancer Research UK Your research papers will be:

available free of charge to the entire biomedical community peer reviewed and published immediately upon acceptance cited in PubMed and archived on PubMed Central yours — you keep the copyright

Submit your manuscript here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/publishing_adv.asp

BioMedcentral

25. Ohno T, Mikami E, Matsumoto H, Kawaguchi N: Identification tests of aristolochic acid in crude drugs by reversed-phase TLC/scanning densitometry. J Health Sci 2006, 52(1):78-81. 26. Ioset JR, Raoelison GE, Hostettmann K: Detection of aristolochic

acid in Chinese phytomedicines and dietary supplements used as slimming regimens. Food Chem Toxicol 2003, 41(1):29-36.

27. Jou J-H, Li C-Y, Schelonka EP, Lin C-H, Wu T-S: Analysis of the analogue of aristolochic acid and aristolactam in the plant of aristolochia genus by HPLC. J Food Drug Anal 2004, 12(1):40-45. 28. Schaneberg BT, Khan IA: Analysis of products suspected of con-taining Aristolochia or Asarum species. J Ethnopharmacol 2004, 94(2–3):245-249.

29. Hashimoto K, Higuchi M, Makino B, Sakakibara I, Kubo M, Komatsu Y, Maruno M, Okada M: Quantitative analysis of aristolochic acids, toxic compounds, contained in some medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol 1999, 64(2):185-189.

30. Jong TT, Lee MR, Hsiao SS, Hsai JL, Wu TS, Chiang ST, Cai SQ: Anal-ysis of aristolochic acid in nine sources of Xixin, a traditional Chinese medicine, by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2003, 33(4):831-837.

31. U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition Dietary Supplements: Aristolochic Acid [http:// www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/ds-bot.html].

32. Drew AK, Whyte IM, Bensoussan A, Dawson AH, Zhu X, Myers SP: Chinese herbal medicine toxicology database: monograph on Herba Asari, "xi xin". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2002, 40(2):169-172.

33. WHO: General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine. In Document WHO/ EDM/TRM/2000.1 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. 34. Molony D: The American Association of Oriental Medicine's Complete

Guide to Chinese Herbal Medicine New York: Berkley Books; 1998:65-72.

35. Editors: Huangdi Neijing-Suwen. Document CM017 [http:www.ccmp.gov.tw/public/pub

lic.asp?selno=712&relno=712&level=C]. Taiwan: Committee on Chi-nese Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Health Executive Yuan 36. WHO: WHO Traditional medicine strategy 2002–2005. In

Document WHO/EDM/TRM/2002.1 Geneva: World Health Organiza-tion; 2002.

37. Guh JY, Chen HC, Tsai JF, Chuang LY: Herbal therapy is associ-ated with the risk of CKD in adults not using analgesics in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis 2007, 49(5):626-633.

38. Hsieh SC, Lai JN, Lee CF, Tseng WL, Hu FC, Wang JD: The pre-scribing of Chinese herbal products in Taiwan: a cross-sec-tional analysis of the nacross-sec-tional health insurance reimbursement database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008, 17(6):609-619.

39. Kung YY, Chen YC, Hwang SJ, Chen TJ, Chen FP: The prescriptions frequencies and patterns of Chinese herbal medicine for allergic rhinitis in Taiwan. Allergy 2006, 61(11):1316-1318. 40. Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of

Health Executive Yuan, Taiwan: List of 100 unified formulas [http:// www.ccmp.gov.tw/information/

formula_type.asp?relno=549&level=C].

41. Bureau of National Health Insurance, Taiwan: The National Health Insurance Statistics – Beneficiaries profile [http://www.nhi.gov.tw/web data/web

data.asp?menu=1&menu_id=4&webdata_id=815&WD_ID=20]. 42. Knuth DE: Art of Computer Programming, Seminumerical Algorithms

Vol-ume 2. Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional; 1997.

43. Park SK, Miller KW: Random Number Generators: Good Ones are Hard to Find. CACM 1988, 31(10):1192-120.

44. Bureau of National Health Insurance, Taiwan: International publications regarding the use of national health insurance database Taiwan [http:// www.nhri.org.tw/nhird/talk_07.htm].