Published online: 18 September 2002 © Springer-Verlag 2002

Abstract Many medical profession-als are still confused when facing the reduction of food or fluid intake in terminal cancer patients. The aim of this study was to assess the frequen-cy and causes of the inability of eat-ing or drinkeat-ing in terminal cancer patients and to investigate the use of artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH); the frequency, type, and the extent to which staff found ANH to be ethically justified. Three hundred forty-four consecutive patients with terminal cancer admitted to a pallia-tive care unit in Taiwan were recruit-ed. A structured data collection form was used daily to evaluate clinical conditions, which were analyzed at the time of admission, 1 week after admission and 48 h before death. One hundred thirty-three (38.7%) of the 344 patients were unable to take water or food orally on admission; the leading cause was GI tract distur-bances (58.6%). This impaired abili-ty to eat or drink had become worse 1 week after admission (39.1%, P<0.01) and again 48 h before death (60.1%, P<0.001). The total rate of ANH use declined significantly, from 57.0% to 46.9% 1 week after admission (P<0.001), but rose again to the same level as at admission in

the 48 h before death (53.1%, P=0.169). Parenteral hydratation could be reduced significantly 1 week after admission (P<0.05), but no reduction was possible in the 48 h before death; nor was it possible to reduce the nutrition administered. Multiple Cox regression analysis shows that the administration of ANH, either at admission or 2 days before death, did not have any signif-icant influence on the patients’ sur-vival (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.58–1.07; HR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.76–1.38). In conclusion, sensitive care and con-tinuous communication will proba-bly lessen the use of ANH in termi-nal cancer patients. We have found it easier to reduce artificial hydratation than artificial nutrition, which corre-sponds to local cultural practice. Whether or not ANH was used did not influence survival in this study. Thus, the goals of care for terminal cancer patients should be refocused on the promotion of quality of life and preparation for death, rather than in simply making every effort to im-prove the status of hydratation and nutrition.

Keywords Nutrition · Hydratation · Terminal cancer · Survival · Ethics T.-Y. Chiu

W.-Y. Hu R.-B. Chuang C.-Y. Chen

Nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer

patients in Taiwan

Introduction

The reduction of food or water intake and the use of arti-ficial nutrition and hydratation (ANH) in terminal cancer

patients are confusing and troubling issues for the medi-cal staff involved in the care of these patients. Other-wise, the symptoms related to malnutrition or dehydra-tion, such as asthenia, anorexia, and nausea/vomiting,

T.-Y. Chiu (

✉

)Department of Family Medicine, and Social Medicine,

College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

e-mail: tychiu@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw Tel.: +886-2-23562878

W.-Y. Hu

School of Nursing,

College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

R.-B. Chuang

Department of Family Medicine, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

C.-Y. Chen

Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine and Hospital, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

T.-Y. Chiu

No 7, Chung-Shan South Road. Taipei, Taiwan

which usually appear as part of the natural process of dy-ing and are often difficult to manage, are also severely distressing the patients, their families and the medical staff caring for them [2, 5, 8, 21]. Many medical profes-sionals still lack expertise in managing these issues prop-erly and comfortably [12, 15].

Early studies suggested that aggressive nutritional therapy could improve the response to antineoplastic treatments or reduce the incidence and/or severity of complications in these patients [3, 18]. However, later randomized controlled studies have suggested that ag-gressive nutritional therapy has no impact on tumor re-sponse, toxicity, or survival [1, 9]. Moreover, one animal study showed that aggressive nutritional therapy could significantly increase tumor growth [20]. It is widely recognized that the outcome measures of aggressive nu-tritional therapy for patients with advanced cancer should also include the patients’ overall quality of life [14]. Unfortunately, there is currently no evidence that aggressive nutrition therapy can improve such patients’ quality of life [10, 14, 16, 19, 22, 23].

In Taiwan, the decision to use or forgo artificial nutri-tion and hydranutri-tion (ANH) remains a perplexing and emotional issue in the care of terminally cancer patients. A previous study in Taiwan, conducted in 1998, showed that about one quarter of palliative care patients have en-countered the ethical conflicts of using nutrition and hy-dratation during their stay in hospital [7]. We felt that in the interests of providing better communication and ap-propriate support for nutrition and hydratation, an explo-ration of the current use of nutrition and hydratation in these terminally ill patients would be helpful.

The aims of this study were to assess the frequency and causes of inability to eat or drink in terminal cancer patients. In addition, an investigation of the use of ANH, including its frequency and type and the extent to which staff found ANH to be ethically justified, should also be carried out. The results suggest improvements which may promote the local quality of terminal care.

Patients and methods

PatientsThree hundred forty-four consecutive patients with advanced can-cer who were admitted to the hospice and palliative care unit of National Taiwan University Hospital between January 2000 and the end of February 2001, were enrolled in the study. Patients whose cancers were not responsive to curative treatment were identified in an initial assessment performed by members of the admissions committee. The selection of patients and design of this study were approved both by the National Science Council in Taiwan and by the ethical committee in the hospital. By the end of the study period, 319 (92.7%) of the patients had died.

Instrument

The assessment tool used was a recording form designed after a careful scrutiny of the literature in this area by the investigators. The form was tested for content validity with a panel comprising physicians, a nursing supervisor, senior nurses and a dietitian, all of whom were experienced specialists in the care of terminal can-cer patients. In addition, a pilot study was conducted for 1 month in the same unit. The pilot study further confirmed the instru-ment’s content validity and ease of application. The instrument re-corded demographic data (gender, age), clinical oncological condi-tions (primary cancer sites, metastases, outcome, and survival time), hydration and nutrition status, conditions of nutrient intake (route of intake, type of nutrients), causes of any inability to eat or drink (consciousness disturbance, head/neck cancer, esophageal obstruction, gastrointestinal tract disturbances, fatigue/anorexia due to underling pathology, and emotional factors), the use of ANH [frequency, type (tube feeding and parenteral hydration and nutrition)] and the extent to which staff found ANH to be ethically justified (appropriate, only acceptable, or inappropriate to the de-cision to use ANH).

Impaired eating or drinking was defined in the study as the in-ability to take water or food by mouth. When the patient becomes unable to take water or food orally, the care problems and ethical conflicts arise very easily. Patients who could take even a little water by mouth were not considered impaired as defined in this study.

Methods

Conditions of water and nutrient intake, prevalence of common symptoms, and the use of artificial nutrition and hydratation were recorded daily by the same members of staff. Data were assessed and subsequently analyzed at the time of admission, 1 week after admission, and 48 h before death (retrospectively) in a weekly team meeting. All of the 344 patients admitted, including 243 pa-tients whose stay in the hospice extended to longer than 1 week and 273 patients who had died in the hospice, were completely as-sessed. Moreover, we analyzed the clinical circumstances of each case and investigated the conflicts among patients, families and medical staff in decision-making relating to the use of ANH on the basis of moral discussions in the 60 weekly team meetings held during the study period.

The use of ANH at the time of admission was usually depen-dent on a previous prescription issued by the referring physicians, despite the fact that the amount of ANH was always rapidly re-duced to less than 1 l of fluid after admission on the basis of the patient’s condition. The decision to use ANH 1 week after admis-sion was always made on the basis of consultation among medical staff, patients and families, indicating the effectiveness of such communication.

Statistical analysis

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 8.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, Ill.). Frequency butions were used to describe the demographic data and the distri-bution of each variable. Mean values and standard deviation were used to analyze the severity of each symptom. The McNemar test was used to compare the changes between frequency of the capabil-ity of oral intake and the use of ANH. A paired t-test was used to compare the differences in fluid amounts at different times. After-ward, multiple Cox regression analysis was used to examine the in-fluence of the following factors on survival: gender, age, primary cancer sites, common symptoms in the study patients (fatigue, pain, and confusion), the capability of oral intake, and the use of ANH. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

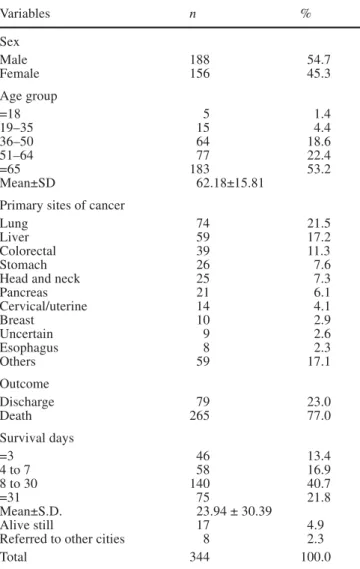

The primary cancer sites in these patients were lung (21.5%), liver (17.2%), colon/rectum (11.3%) and stom-ach (7.6%); 274 patients (79.7%) already had metastases. Around a third of the patients (30.3%) died within 1 week of admission, and mean survival was 23.94 days. The demographic characteristics are displayed in Ta-ble 1.

Table 2 shows the prevalence and causes of the inabil-ity to take water or food by mouth. One hundred thirty-three patients (38.7%) were unable to eat or drink at the time of admission, for which the main causes in the opinion of the medical staff were gastrointestinal tract disturbances (58.6%), systemic disorders including fa-tigue or anorexia due to the underlying pathology (42.9%), disturbed consciousness (33.8%), and emotion-al factors (8.3%). Two hundred eleven patients (61.3%) were capable of taking water or food orally on admis-sion, but 143 of them (67.8%) needed help from caregiv-ers. One week after admission, the percentage of the re-maining 243 patients who were incapable of eating or drinking was significantly higher than on admission (39.1% vs 32.1%, P<0.001). The percentage worsened to 60.1% 2 days before death, with significant differences from the situation in the same 273 patients at the time of admission (41.4%, P<0.001), when systemic disorders, including fatigue and anorexia due to the underlying pa-thology, became the leading cause of inability to eat or drink (43.3%). One hundred nine patients (39.9%) were still able to take some water or food by mouth 2 days be-fore death, but nearly all (n=108, 99.1%) of them need help from their caregivers.

As seen in Table 3, 196 (57.0%) of the 344 patients received ANH on admission, with its prevalence

signifi-Table 1 Demographic characteristics of patients

Variables n % Sex Male 188 54.7 Female 156 45.3 Age group =18 5 1.4 19–35 15 4.4 36–50 64 18.6 51–64 77 22.4 =65 183 53.2 Mean±SD 62.18±15.81

Primary sites of cancer

Lung 74 21.5

Liver 59 17.2

Colorectal 39 11.3

Stomach 26 7.6

Head and neck 25 7.3

Pancreas 21 6.1 Cervical/uterine 14 4.1 Breast 10 2.9 Uncertain 9 2.6 Esophagus 8 2.3 Others 59 17.1 Outcome Discharge 79 23.0 Death 265 77.0 Survival days =3 46 13.4 4 to 7 58 16.9 8 to 30 140 40.7 =31 75 21.8 Mean±S.D. 23.94 ± 30.39 Alive still 17 4.9

Referred to other cities 8 2.3

Total 344 100.0

Table 2 Frequency and causes of inability to eat or drink in terminal cancer

Admission One week after admission Two days before to death

No. % No. % No. %

Unable to eat or drink orally?

Unable to 133 38.7 95 39.1* 164 60.1**

Able to 211 61.3 148 60.9 109 39.9

Total patients 344 100.0 243 100.0 273 100.0

Main causes of inability to eat and drink by mouth (multiple choices)

Consciousness disturbance 45 33.8 32 33.7 56 34.1

Head/neck tumor 34 25.6 26 27.4 27 16.5

Esophageal obstruction 15 11.3 13 13.7 11 6.7

GI disturbances 78 58.6 53 55.8 69 42.1

Systemic disorders including fatigue or anorexia 57 42.9 37 38.9 71 43.3

Emotional factors 11 8.3 8 8.4 9 5.5

Total impaired patients 133 95 164

*P<0.01: the ability decreased compared to the same patients (n=243) at the time of admission; **P<0.001: the ability decreased com-pared to the same patients (n=273) at the time of admission

cantly decreasing to 46.9% after 1 week in the hospice, as against 58.4% of the same 243 patients on admission (P<0.001). The percentage of patients receiving ANH in-creased again, to 53.1%, in the 48 h before death, al-though it was still lower than the percentage of the same 273 patients receiving ANH (57.5%) on admission (P=0.169).

Concerning the types of AHN, we found the percent-age of patients using parenteral hydratation (including electrolytes) 1 week after admission declined to a statis-tically significant extent from the percentage of the same 243 patients at the time of admission (37.0% vs 44.5%, P<0.05). However, there was no further statistically sig-nificant decline in the percentage in the 48 h before death (43.2%, P=0.597). Compared with the situation at the time of admission, the percentage of patients being tube fed and receiving glucose or other nutrients parente-rally was not significantly lower either 1 week after

ad-mission or 48 h before death. Furthermore, in the study the volume of parenteral fluids used in the patients was calculated, revealing that the mean amount of i.v. fluid used declined significantly from 862±618 ml at the time of admission to 714±528 ml 1 week after admission (t=10.82, P<0.001). This tendency to decline persisted into the 2 days before death, when the mean volume was 637±420 ml (t=8.671, P<0.001).

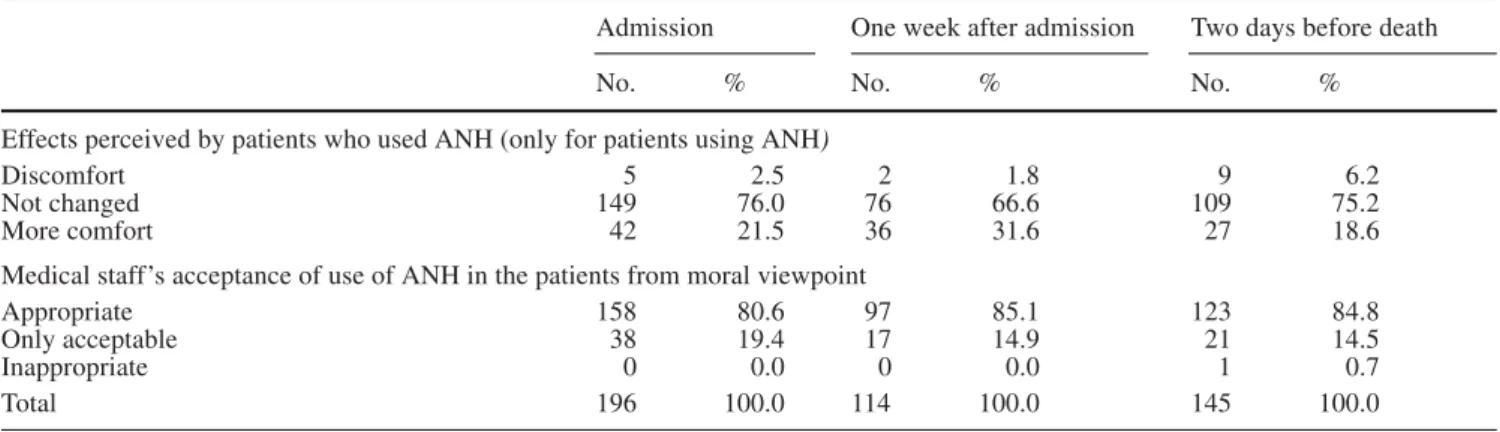

Table 4 shows the effects and the moral acceptability of using ANH. As far as the effects perceived by patients after ANH are concerned, only 4 (2.0%) out of 196 pa-tients complained of discomfort on admission, which was assessed by the medical staff from the aspect of care. On admission, in the majority (80.6%) of patients receiving ANH this was recognized as an appropriate de-cision by the medical staff in the weekly ethical discus-sions, but in some cases (19.4%) the decision to imple-ment ANH was thought to be acceptable only from the

Table 3 Use of artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) in terminal cancer patients

Admission One week after admission Two days before death

No. % No. % No. %

Using ANH?

Using 196 57.0 114 46.9* 145 53.1

Not using 148 43.0 129 53.1 128 46.9

Total 344 100.0 243 100.0 273 100.0

Types of ANH (multiple choices)

Tube feeding 44 12.8 31 12.8 35 12.8

Parenteral

1) Hydration and electrolyte 153 44.5 90 37.0** 118 43.2

2) Glucose 127 36.9 77 31.7 106 38.8

3) Other nutrients 66 19.2 37 15.2 50 18.3

(albumin, amino acid, intrafat,.. etc)

Mean amount (ml) of i.v. fluid 862±618 714±528* 637±420***

Total 344 243 273

*P<0.001: decreased compared with the condition of the same pa-tients (n=243) at the time of admission; **P<0.05: decreased com-pared to the condition of the same patients (n=243) at the time of

admission; ***P<0.001: decreased compared to the condition of the same patients (n=273) at the time of admission

Table 4 Effects perceived by patients subjectively and ethical acceptability of medical staff toward the use of ANH

Admission One week after admission Two days before death

No. % No. % No. %

Effects perceived by patients who used ANH (only for patients using ANH)

Discomfort 5 2.5 2 1.8 9 6.2

Not changed 149 76.0 76 66.6 109 75.2

More comfort 42 21.5 36 31.6 27 18.6

Medical staff’s acceptance of use of ANH in the patients from moral viewpoint

Appropriate 158 80.6 97 85.1 123 84.8

Only acceptable 38 19.4 17 14.9 21 14.5

Inappropriate 0 0.0 0 0.0 1 0.7

moral aspect. It is worth mentioning that the percentage of those feeling there was an inappropriate use of ANH persisted until very near the death of the patients con-cerned, implying potential conflicts among patients, fam-ilies, and medical staff. In this study the clinical circum-stances of each patient were also analyzed and the deci-sion-making conflicts experienced among patients, fami-lies and medical staff in relation to the use of ANH were investigated. Twenty-three (6.7%) out of 344 patients or their families insisted on the use of ANH immediately on admission although it was thought to be inappropriate on the basis of a careful assessment made by medical staff. These conflicts persisted into the 48 h before death in 17 (6.2%) of the 273 patients remaining.

Both the families and the medical staff always worry that if ANH is withheld from terminally ill patients this may shorten the patient’s life. Therefore, this study also examined the influence of ANH on patients’ survival. The results of multiple Cox regression analysis (Table 5) show that ANH, either on admission or 2 days before death, does not significantly influence survival (hazard ratios: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.58–1.07; hazard ratios: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.76–1.38).

Discussion

This prospective study not only recorded the frequency and causes of eating and drinking impairment, but also investigated the details and morality of ANH in terminal cancer patients. Past experience in Taiwanese hospices has shown that one of the most common controversies at the interface between general hospital wards and pallia-tive care units is that over the use of ANH. When we have more evidence about the appropriate use of hydra-tion and nutrihydra-tion in terminal cancer patients, this may lead to better care both in palliative care units and on general hospital wards.

Although in this study the percentage of patients un-able to take fluid or food by mouth as a result of the dis-ease process incrdis-eased after admission, the percentage of patients using ANH significantly declined after admis-sion because of constant care and appropriate informa-tion from the several aspects. Clinically, more than one third (38.7%) of the patients studied were unable to eat or drink at the time of admission. The fact that the pro-portion is so large indicates the importance of managing this problem. First, we comprehensively assessed the reasons for these difficulties, noting: incorrect types of

food, inappropriate time to supply, stomatitis, physiolog-ical causes, and any emotional factors. Many patients in the study were able to take more food or water by mouth after improved oral hygiene, a change in food type, or assistance with family–patient interaction. Corticoste-roids (time-limited trials) and prokinetic agents were of-ten given to improve the appetite and facilitate the pas-sage of food, lowering the need for ANH. It then became possible for the mutual interaction among patients, fami-lies and medical staff to be more intimate, thereby pav-ing the way for a higher quality of care. In this study, the percentage of ANH use increased again before death, implying renewed difficulties with decisions about ANH use near death. Further exploration of the concerns of patients and families in this phase will be valuable. Moreover, although hydratation by a subcutaneous route is a preferred approach in many hospices [4, 11], this procedure is still rarely used in Taiwan. Development of this simple technique may be very helpful in solving some of these difficulties arising in the time immediately before death.

Concerning socio-cultural issues, in most cultures the provision of food or drink is seen as a basic act of caring. Feeding has powerful symbolic and social significance [17], especially in Asia. Difficulty in eating or drinking often leads to anxiety in the patient’s loved ones, who worry that the patient will starve to death and therefore become a “starving soul” after death. Such cultural con-cerns in Taiwan are behind family requests to provide food or fluids, particularly nutrients, which is reflected in the findings of this study, indicating that it would be possible to reduce the use of artificial hydratation more than the use of nutrition. These concerns might cause greater discomfort for patients and make it necessary for them to be in hospital rather than at home.

With regard to withholding or providing ANH, we ex-plain the causes of problems with eating or drinking and the potential benefits and drawbacks of ANH to the pa-tients (if possible) and to their families, although the evi-dence for some of these benefits and drawbacks remains inconclusive. Communication seems to have improved in the study hospice, where 25% of patients reported con-flicts about the use of ANH in 1998 [7], but only under 10% of patients admitted to this study encountered the same trouble in 2001. Furthermore, perhaps since the ma-jority of Taiwanese are Buddhists, they usually believe that a “good death” can only be achieved in a Buddhist care model, especially in the very terminal stage. The staff in the study hospice always gently explained that in

Table 5 The influence of ANH

use on the survival of patients by using multiple Cox regres-sion analysis

Hazard ratios (95% CI) p-Value Using ANH at the time of admission 0.88 (0.58–1.07) 0.34 Using ANH 2 days before death 1.03 (0.76–1.38) 0.86

Buddhism excessive nutrition or hydratation is inappro-priate to enlightenment and inspiration, both of which are helpful in achieving a better afterlife. Families usually understand and accept this explanation, and it relieves their anxiety to some extent. The staff also encourage family members to stay with the patients and provide del-icate care in such forms as touching, kissing, or speaking Buddhist phrases; this replaces the use of ANH, which may be linked with the idea of the best care in the minds of the families. After such care, although the inability to take fluid or food by mouth becomes very prominent in the dying process, the number of patients using ANH did not increase (53.1%), and the proportion of cases in which there were conflicts between the medical staff and the families was not considered remarkable (6.7%).

With regard to ethical implications, the U.S. Supreme Court has made a clear distinction between withdrawal of life support and assisted suicide, namely, between al-lowing death and killing. When the intention behind dis-continuation of ANH is to cause death it is not ethically permissible. If the intention is to cease futile treatment, discontinuation is ethically justified [14, 23]. The staff of Taiwanese hospices have also received intensive training in the ethical implications of ANH in recent years. The findings of this study also show that ANH has no signifi-cant influence on survival, which could be explained with reference to the “terminal common pathway” in cancer patients [6, 21], which may validate the ethical nature of withholding ANH, which always involves drawbacks or risks that are disproportionate to the bene-fits for these patients. Legally, ANH has been recognized as a medical treatment, which can be refused by a com-petent adult or a surrogate decision maker appointed

through an advance directive [16, 22]. This is embodied in the Natural Death Act enacted in Taiwan in June 2000 [13]. This law not only represents respect for the dignity of the terminally ill, but also facilitates ethical decision-making in end-of-life care including the use of ANH.

Certain caveats should be mentioned in relation to this study. First, the authors have attempted to research artificial nutrition and artificial hydratation together in this exploratory study, owing to the generally held ideas about mixing the provision of nutrients and fluid in Tai-wan. However, it may be better to clarify this issue in further empirical work. Second, the energy of the nutri-ents administered was not calculated in the study, though this may also be important in the decision-making be-hind the use of ANH.

In conclusion, the prevalence of inability to eat or drink in terminal cancer patients is rather high, which is due to the natural course of the disease. Delicate care and continuing communication can be helpful in avoid-ing unnecessary artificial nutrition or hydration. Artifi-cial hydratation is found to be easier to decrease than nu-trition. Whether or not ANH was given did not influence survival in the study. Thus, the goals of care for these terminal cancer patients should be re-focused on the pro-motion of quality of life and preparation for a good death, rather than on simply making every effort to im-prove the hydratation and nutrition status.

Acknowledgements This research was supported by the National

Science Council in Taiwan (NSC 89-2314-B-002-560). The au-thors are indebted to the faculty staff of the Department of Family Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, for their full sup-port in conducting this study and also to Ms. Y.Y. Pan for her as-sistance in preparing the manuscript.

Reference

1. Apelgren KN, Wilmore DW (1984) Parenteral nutrition: is it oncologically logical? J Clin Oncol 2:539–541 2. Baines M (1988) Nausea and vomiting

in the patient with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 3:81–85 3. Blackburn G, Miller M, Bothe A

(1985) Nutritional factors in cancer in medical oncology. In: Calabresi P, Schein P (eds) Oncology. MacMillan, New York, pp 1406–1432

4. Bozzetti F, Amadori D, Bruera E, et al (1996) Guidelines on artificial nutrition versus hydration in terminal cancer pa-tients. European Association for Pallia-tive Care. Nutrition 12:163–167 5. Bruera E, MacDonald RN (1988)

As-thenia in patients with advanced can-cer. J Pain Symptom Manage 3:9–14

6. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Cheng SY, et al (2000) Ethical dilemmas in palliative care: a study in Taiwan. J Med Ethics 26:353–357

7. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chen CY (2000) Prevalence and severity of symptoms in terminal cancer patients: a study in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 8:311–313

8. Curtis EB, Krech R, Walsh TD (1991) Common symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Care 7:25–29

9. Evans WK, Nixon DW, Daly JM, et al (1987) A randomized study of oral nu-tritional support versus ad lib nutrition-al intake during chemotherapy for ad-vanced colorectal and non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 5:113–124 10. Fainsinger RL, Bruera E (1997) When

to treat dehydration in a terminally ill patient? Support Care Cancer 5:205–211

11. Fainsinger RL, MacEachern T, Miller MJ, et al (1994) The use of hypoder-moclysis for rehydration in terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 9:298–302

12. Finlay I (1996) Difficult decisions in palliative care. J Hosp Med

56:264–267

13. Hu WY, Chiu TY, Lue BH, et al (2001) An educational need to “Natural Death Act” in Taiwan. J Med Educ 5:21–32 14. Huang ZB, Ahronheim JC (2000)

Nu-trition and hydration in terminally ill patients: an update. Clin Geriatr Med 16:313–325

15. Kinzbrunner BM (1995) Ethical dilem-mas in hospice and palliative care. Support Care Cancer 3:28–36

16. McCann RM, Hall WJ, Groth-Jun-cker A (1994) Comfort care for termi-nally ill patients. The appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA 272:1263–1266

17. McInerney F (1992) Provision of food and fluids in terminal care: a sociologi-cal analysis. Soc Sci Med

34:1271–1276

18. Smale BF, Mullen JL, Buzby GP, et al (1981) The efficacy of nutritional as-sessment and support in cancer surgery. Cancer 47:2375–2381

19. The Hastings Center (1987) Guidelines on the termination of life-sustaining treatment and care of the dying. Indi-ana University Press, Bloomington 20. Torosian MH, Daly JM (1986)

Nutri-tional support in the cancer-bearing host. Effects on host and tumor. Cancer 58:1915–1929

21. Vainio A, Auvinen A (1996) Preva-lence of symptoms among patients with advanced cancer: an international collaborative study. Symptom Preva-lence Group. J Pain Symptom Manage 12:3–10

22. Waller A, Hershkowitz M, Adunsky A (1994) The effect of intravenous fluid infusion on blood and urine parameters of hydration and on state of conscious-ness in terminal cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 11:22–27 23. Zerwekh JV (1997) Do dying patients

really need i.v. fluids? Am J Nurs 97:26–30