On the Biasing Judgment of Innovation:

Context Effect of Existent Brand

Chung-Chiang Hsiao

Assistant Professor, Institute of Technology Management National Tsinghua University

Yi-Wen Chien

Assistant Professor, Department of Business Administration National Taiwan University

ABSTRACT

A theoretical framework is proposed in this study to explain how the evaluation of the innovation, be it incremental or radical, can be biased by the accessible perception of existent brand (such as core brand, co-brand, or ingredient brand). The underlying mechanisms in the proposed theoretical framework are constructed by theories of context effect, particularly the Dimensional Range Overlap Model. It is proposed that when there is an overlap between the interpretation range of the innovative product and that of the existent brand on the shared attribute, the innovative product will be perceived as more similar to the existent brand than when perceptions of the existent brand is not accessible (assimilation). On the other hand, when the interpretation range of the innovative product is not overlapped with the counterpart of the existent brand on the shared attribute, the innovative product will be perceived as more dissimilar to the existent brand than when no information of the existent brand is accessible (contrast). It is possible that the innovative product is perceived as more similar to the existent brand on some attributes with overlapped interpretation ranges, while, at the same time, perceived as more dissimilar to the existent brand on other attributes with non-overlapped interpretation ranges. Furthermore, the interpretation range of the innovative product on the unique attribute, to which the existent brand is not applicable, will not be biased by the existent brand. Marketing implications based on the proposed theoretical framework is provided in the end.

Keywords:

Biased Judgment, Context Effect, Assimilation, Contrast, Incremental Innovation, Radical InnovationI. Introduction

This study provides a theoretical framework that explains how judgments of an innovative product can be biased by the perceptions on the existent brand. The Note: The authors thank anonymous reviewers very much for helpful comments on

an earlier draft of this manuscript. Correspondence should be addressed to Chung-Chiang Hsiao, Institute of Technology Management, National Tsinghua University.

existent brand can be the core brand from which the innovative product is extended or the associated brand (e.g. co-brand or ingredient brand). When a company introduces an innovative product, it is assumed that the existent brand can serve as a prime that will activate all the stored information related to it, especially the perception of the incumbent products (i.e. products currently available in the market) that bear the same brand name. Such an activation of associated perception of the existent brand will, therefore, become very accessible so as to influence consumers’ judgments on the new, innovative product. For example, assume IBM introduces a new laptop computer with claims that this computer has many improved features. When consumers watch IBM’s TV commercial, the brand name “IBM” may activate many relevant constructs that are related to it and that are stored in consumers’ memory, such as IBM products are of high-quality, IBM’s keyboard has the best touch feeling, etc. All of such information may thus become very accessible and may produce biases in judgments of the new, innovative product.

According to previous theories on accessibility and context effects (Herr, 1986, 1989; Herr, Sherman, & Fazio, 1983; Higgins, 1996; Higgins, Bargh, & Lombardi, 1985; Higgins & Brendl, 1995; Srull & Wyer, 1979, 1980; Stapel, Koomen, & Velthuijsen, 1998), accessible context information may bias target (i.e. evaluated product or object) judgments in two different ways. One is called assimilation effect, which makes judgments shift toward the accessible context information. In the above example, assimilation effects occur when the new, innovative laptop is perceived as more similar to the IBM’s incumbent laptops than if there is no accessible context information. In other words, consumers may not perceive the new product as highly innovative. The other is called contrast effect, which makes judgments shift away from the accessible context information. So, in the above example, contrast effects occur when the new, innovative laptop is perceived as more dissimilar to the IBM’s incumbent laptops than if no context information is accessible. That is, consumers may perceive the new product as highly innovative.

When will assimilation effects occur? And when will contrast effects occur? There have been many models in social psychology explaining the occurrence of assimilation and contrast. In general, assimilation is considered more likely to occur when people perceive the target and the context as very similar or belonging to the same category. Under such circumstances, judgments of the target will be assimilated toward the context. On the contrary, when people perceive the target and the context as very dissimilar or belonging to different categories, contrast will occur so that judgments will be made away from the context.

The current study proposes an explanation of process that underlies how judgments of the innovative product will be biased by the perception of the existent brand. Innovation continuum and theories explaining biased judgments will be discussed in the following sections. The proposed theoretical framework and marketing implication will then be described.

II. Innovation Continuum

Innovation, as a construct studied by engineers and marketers for more than 65 years (Garcia & Calantone, 2002), has a wide spectrum of definitions. As reviewed

by Garcia and Calantone (2002), “no less than fifteen constructs and at least 51 distinct scale items have been used in just 21 empirical studies in the new product development (NPD) literature that model product innovativeness.” In their review finding, past research has focused on the measurement and operation of innovation at either macro level, such as industry and market (Atuahene-Gima, 1995; Mishra, Kim, & Lee, 1996) or micro level, such as firm and customer (Olson, Walker, & Ruekert, 1995).

Despite the different perspectives on explanation of “innovation”, innovative products have been commonly perceived on a continuum anchored by incremental innovation and radical/breakthrough innovation (Balachandra & Friar, 1997; Chandy & Tellis, 2000; Kessler & Chakrabarti, 1999; Lee & Na, 1994). On the one end, an innovation is more likely to be categorized as an incremental improvement when the innovation is not perceived as significantly different from the incumbent products. Incremental innovations are thought to be close substitutes (Rangan & Bartus, 1995) of incumbent products. In this study, the incremental product innovation is defined as the innovative product sharing most of the product attributes/features with the incumbent products, but a subset of attributes in incremental product innovations have better performance than those in incumbent products. For example, a LCD display with SXGA (1280*1024) resolution is an incremental improvement to a LCD display with XGA (1024*768), even when all other attributes between two LCD displays are the same. A notebook with an additional embedded wireless LAN (local area network) embedded can also be an incremental improvement to an identical notebook without wireless LAN, because the communication capability of the notebook has been enhanced without the constraint of wired LAN. Consumers’ articulations of unsatisfied needs contribute to the most initiations of incremental innovations. In addition, manufacturers’ differentiation strategies, in responding to diversified market segments and niches in the mature market, facilitate the commercialization of incremental innovations as well.

On the other end, an innovation is more likely to be categorized as a radical/breakthrough innovation when the innovation is perceived significantly different from the incumbent products (Rangan & Bartus, 1995), and when the innovation “incorporates a substantially different core technology and provides substantially higher customer benefits” (Chandy & Tellis, 1998). In this study, the radical product innovation is defined as the innovative product sharing few product attributes/features with the incumbent products. In the extreme case, a radical innovation shares no attribute with incumbent products. For example, the introduction of the first TV set was perceived as a radical improvement to the radio (a then-current product). However, in the general business setting, few products are extremely radical. Most of the radical innovations still share some of the attributes with incumbent products. On the continuum of innovation anchored by incremental and radical innovations, the fewer attributes shared with incumbent products, the more radical an innovation is perceived to be.

III. Context Effects: Assimilation and Contrast

Most theories studying context effects have focused on the effects of the two factors: target ambiguity and context extremity, that influence the occurrence of assimilation and contrast. For example, Herr’s feature match model (Herr, Sherman, & Fazio, 1983) proposes that whether there is a feature match between the target

and the accessible context influences whether assimilation or contrast will occur. Target ambiguity and context extremity are the two factors that determine if there is a feature match. The more ambiguous the target and the less extreme the context, the more likely it is that there is a feature match (assimilation).

Recently, Dimensional Range Overlap Model (Chien, 2002; Chien & Hsiao, 2001) proposes that, in addition to the above two factors, context’s interpretation range (or ambiguity) should also be considered. The model contends that assimilation and contrast are determined by whether there is an overlap between the interpretation range of the target and the interpretation range of the context on the relevant judgment dimension. When there is an overlap, the target and the context will be perceived as more similar and thus assimilation will occur. But, when there is no overlap, they will be perceived as dissimilar and contrast will occur. More important, three factors: target’s interpretation range, context’s interpretation range, and the relative distance between the target and the context, will determine the occurrence of overlap so as to influence the occurrence of assimilation and contrast. According to this model, if the target and the context cannot be related to the same judgment dimension, the accessible context will not be able to produce any biasing effects on target judgments. This prediction is important in terms of judgments of innovative products. It is because innovation typically can be categorized into two types: incremental and radical innovations, based on the portion of shared attributes between the innovative products and the incumbent products. When most of the attributes in incumbent products are shared by innovative extension (i.e. incremental innovation), the context information (i.e. the perception on the incumbent products) may generate biasing effects on judgments of the innovative extension. However, when fewer attributes in incumbent products are shared by innovative extension (i.e. radical innovation), the biasing effects of the context information on judgments of the innovative extension will be reduced.

IV. Proposed Theory

The current study proposes that consumers’ judgments on an innovative product that bears an existent brand are likely to be biased by consumers’ perceptions on that particular brand. When consumers read an ad about a new, innovative product, its brand, or the associated brand (such as co-brand and ingredient brand; e.g. IBM was co-exposed in Lexmark’s advertisements, when Lexmark was first introduced) may serve as a prime that can activate all the stored information that links with it, particularly the stored perception on the existent brand. In other words, during judgments of the innovative product (i.e. target), perception on the existent brand can, at the same time, become very accessible. Such an accessible perception on the existent brand will in turn bias judgments of the innovative product by either making target judgments shift toward the quality of the existent brand (assimilation) or making target judgments shift away from the quality of the existent brand (contrast).

In the former case, the innovative product is perceived as more similar to the existent brand. In other words, consumers may think this new innovation is not very innovative (or not so different from the incumbent products of the existent brand). This would not be the effect that a marketing manager wants to obtain when the innovative product is originally positioned as more advanced than the incumbent products, or is expected to differentiate itself from the incumbent products of the existent brand. In the latter case, consumers perceive the new product as more

dissimilar to the existent brand. That is, in the contrast condition, consumers may perceive that the innovative product has more enhanced performance or improvements than when perception of the existent brand is not accessible.

For a given set of prime (i.e. existent brand) and target (i.e. innovative product), some consumers may perceive two interpretation range as overlapped on a given judgmental dimension, while the other may perceive those as non-overlapped on the same judgmental dimension. As proposed in Dimensional Range Overlap Model, the existent brand, say IBM, can serve as a prime and further bias the evaluation of innovative product, say a newly introduced notebook, only when both the activated attributes of existent brand and those of the innovative product are applicable on some judgmental dimensions. For example, when both IBM and a newly introduced notebook are applicable on the judgmental dimension, resolution quality (that is, consumers have a set of range and mean with regard to the perceived resolution quality on IBM’s products and on the new notebook), consumers’ evaluations of the new notebook can be biased by the activated information of IBM on the judgmental dimension of resolution quality. On the other hand, if the newly introduced notebook comes with a unique feature of virtual simulation in that the new notebook can simulate the working environment by providing specific smells and surrounding sounds (such as smells and sounds of sea shore, forest, and mountain), then the activated information of IBM will not be applicable to the unique judgmental dimension of virtual simulation.

4.1 Incremental Innovation with Overlap-Assimilation

For incremental innovations sharing most of the attributes with incumbent products of the existent brand, if the interpretation range of the incremental innovation is overlapped with the interpretation range of the existent brand (see Figure 1-1), then, according to Dimensional Range Overlap Model, assimilation will be more likely to occur (see Figure 1-2). For example, a newly introduced notebook with better resolution, such as WXGA, may have an interpretation range that is overlapped with IBM’s interpretation range on the judgmental dimension of resolution quality (Figure 1-1). The evaluation of resolution quality on the new notebook will then be assimilated to that of IBM (Figure 1-2).

Worst Quality Best Quality Interpretation Range

Shared Attribute

Figure 1-1 The Original interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on the Shared Attribute When There Is an Overlap

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute

Figure 1-2 The Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on the Shared Attribute Shifted toward the Existent Brand (Assimilation)

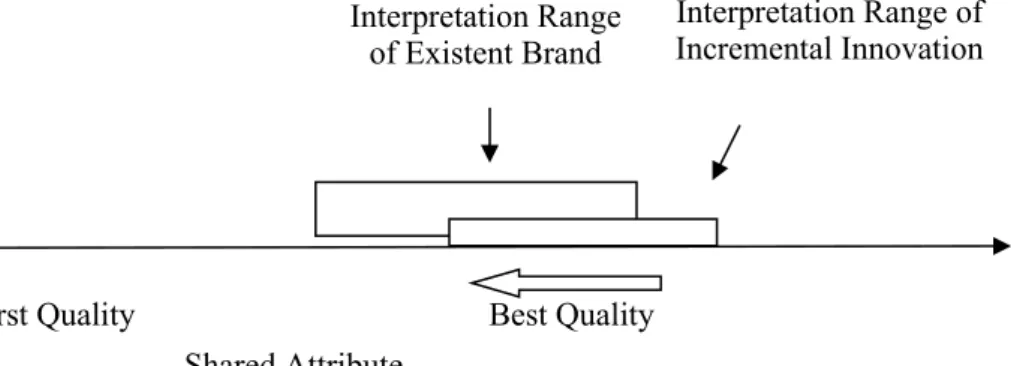

4.2 Incremental Innovation without Overlap-Contrast

For incremental innovations sharing most of the attributes with incumbent products of the existent brand, if the interpretation range of the incremental innovation is not overlapped with the interpretation range of the existent brand (see Figure 2-1), then, according to Dimensional Range Overlap Model, contrast will be more likely to occur (see Figure 2-2). For example, a newly introduced notebook with better resolution, such as WXGA, may have an interpretation range that is not overlapped with IBM’s interpretation range on the judgmental dimension of resolution quality (Figure 2-1). The evaluation of resolution quality on the new notebook will then be contrasted away from that of IBM (Figure 2-2).

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Existent Brand Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation Interpretation Range

Figure 2-1 The Original Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on the Shared Attribute When There Is No Overlap

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute

Figure 2-2 The Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on the Shared Attribute Shifted Away from the Existent Brand (Contrast)

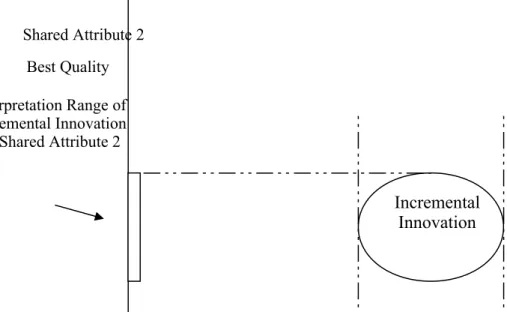

4.3 Incremental Innovation with/without Overlap-Combined Effect

For incremental innovations sharing most of the attributes with incumbent products of the existent brand, if the interpretation range of the incremental innovation is overlapped with the interpretation range of the existent brand in some attributes and not overlapped in other attributes (see Figure 3-1), then assimilation will be more likely to occur in overlapped attributes while contrast will be more likely to occur in non-overlapped attributes (see Figure 3-2). For example, a newly introduced notebook has better resolution, such as WXGA, and an integrated 802.11g wireless feature. If there is an overlap on the judgmental dimension of communication quality between the new notebook and IBM, then the evaluation of communication quality on the new notebook will be assimilated to that of IBM. At the same time, if there is no overlap on the judgmental dimension of resolution quality between the new notebook and IBM, then the evaluation of resolution quality on the new notebook will be contrasted away from that of IBM.Shared Attribute 2 Best Quality

Interpretation Range

of Existent Brand Interpretation Range ofIncremental Innovation

Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on Shared Attribute 2

Incremental

Innovation

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute 1

Figure 3-1 The Original Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation When There Is No Overlap on Shared Attribute 1, But an Overlap

on Shared Attribute 2

Shared Attribute 2 Best Quality Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute 1

Interpretation Range of

Incremental Innovation

on Shared Attribute 1

Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute 2Existent

Brand

Existent

Brand

Incremental

Innovation

I

nterpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute 2 Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on Shared Attribute 2Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute 1

Figure 3-2 The Original Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on the Shared Attribute 1 Shifted Away from the Existent Brand (Contrast), While Shifted toward the Existent Brand on the Shared Attribute 2 (Assimilation)

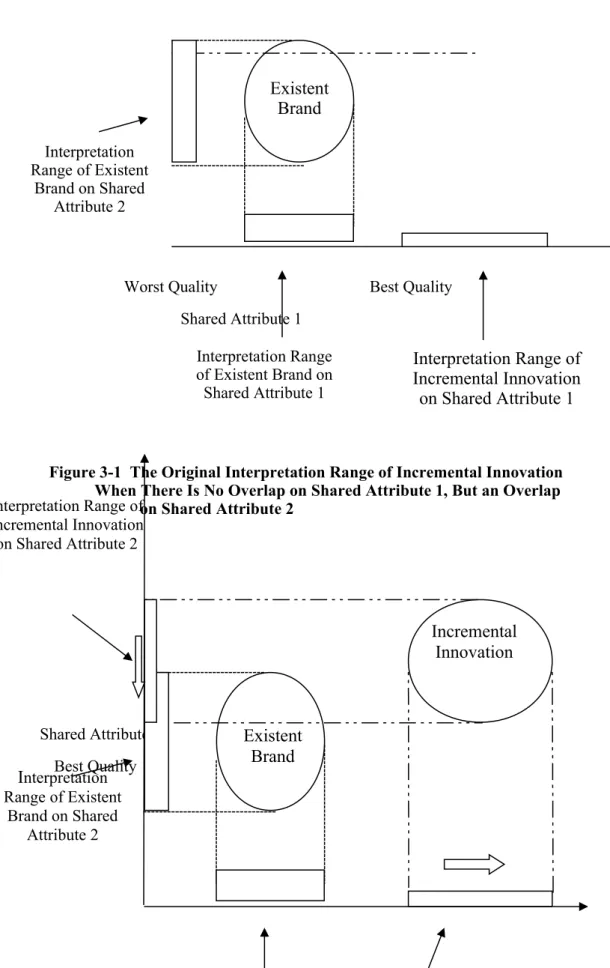

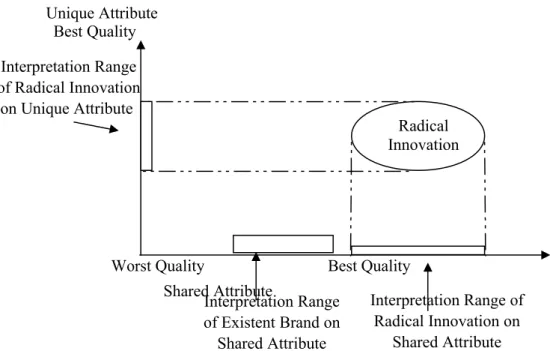

4.4 Radical Innovation with Overlap-Assimilation

For radical innovations sharing fewer attributes with incumbent products of the existent brand, if the interpretation range of the radical innovation is overlapped with the interpretation range of the existent brand on the shared attributes (see Figure 4-1), then assimilation will be more likely to occur. But there would be no context effect on the unique attributes as long as all attributes of the existent brand are not applicable to (or are independent from) the unique attributes (see Figure 4-2). For example, assume a radically new PDA is introduced with unique feature of virtual simulation as mentioned above. The new PDA has somewhat better CPU and computation power than the currently available notebooks in the market. In addition, the new PDA has the ability to project virtual display on the wall and keyboards on the flat surface such that users are able to work on their jobs by the new PDA as if

Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute 1 Interpretation Range of Incremental Innovation on Shared Attribute 1

they work on the regular notebooks. The unique feature of virtual simulation of the new PDA is so radical that all IBM’s attributes are not applicable to the judgmental dimension of virtual simulation. Therefore, consumers’ evaluation of virtual simulation on the new PDA will not be biased or influenced by the activated information of IBM. However, if there is an overlap on the judgmental dimension of computation power between the new PDA and IBM, then the evaluation of computation power on the new PDA will be assimilated to that of IBM.

Unique Attribute Best Quality

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute

Figure 4-1 The Original Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation When There Is an Overlap on the Shared Attribute

Unique Attribute Best Quality Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Shared Attribute Radical Innovation Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Unique Attribute Radical Innovation Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Unique Attribute

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute

Figure 4-2 The interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on the Shared Attribute Shifted toward the Existent Brand (Assimilation), While Unchanged on the Unique Attribute

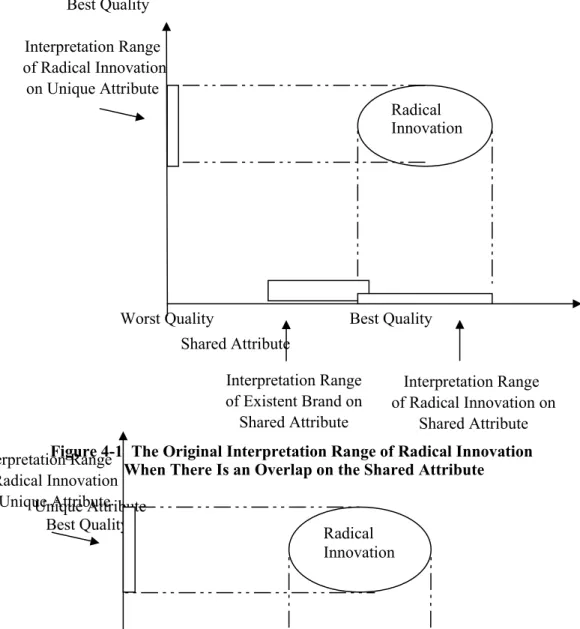

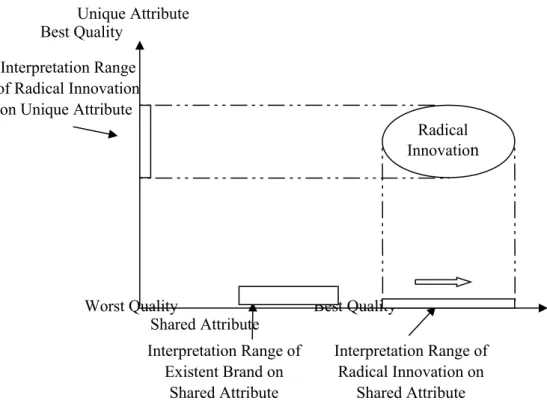

4.5 Radical Innovation without Overlap-Contrast

For radical innovations sharing fewer attributes with incumbent products of the existent brand, if the interpretation range of the radical innovation is not overlapped with the interpretation range of the existent brand on the shared attributes (see Figure 5-1), then contrast will be more likely to occur. But there would be no context effect on the unique attributes as long as all perceived attributes of existent brand are not applicable to (or are independent from) the unique attributes (see Figure 5-2). As in the above example regarding radically new PDA, if the CPU of the new PDA is much better than the currently available notebooks in the market, and therefore, there is no overlap between the new PDA and IBM on the judgmental dimension of computation power, then the evaluation of the new PDA on computation power will be contrasted away from that of IBM.

Unique Attribute Best Quality

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Shared Attribute Radical Innovation Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Unique Attribute

Figure 5-1 The Original Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation When There Is No Overlap on the Shared Attribute

Unique Attribute Best Quality

Worst Quality Best Quality Shared Attribute

Figure 5-2 The Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on the Shared Attribute Shifted Away from the Existent Brand (Contrast),

While Unchanged on the Unique Attribute

V. Conclusion and Marketing Implication

The theoretical framework proposed in this study provides a comprehensive explanation on how the judgment of an innovative product can be biased by the existent brand through the accessibility mechanism in context effect. The existent brand under consideration can be the core brand from which the innovative product is extended or the associated brand (such as brand or ingredient brand) co-exposed in promotions and advertisements with the innovative product. According to the implications of Dimensional Range Overlap Model, every accessible object during target evaluation is associated with an interpretation range applicable on a set of dimensions (or attributes). In the judgment of the innovative product, the existent brand (e.g. core brand or associated brand) is expected to be accessible because of the salient exposures with the innovative product.

The prediction of Dimensional Range Overlap Model, then, suggests that on the attributes to which both innovative product and existent brand are applicable (i.e. shared attributes), the evaluation of the innovative product (serving as target) can be biased by the perception of the existent brand (serving as prime). The underlying determinant of the direction to which the evaluation of an innovative

Interpretation Range of Existent Brand on Shared Attribute Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Shared Attribute Radical Innovatio

n

Interpretation Range of Radical Innovation on Unique Attributeproduct is biased is whether or not there is an overlap between the interpretation range of the innovative product and that of the existent brand on the commonly applicable attributes. The innovative product will be perceived as more similar to the existent brand (assimilation) when there is an overlap between the interpretation range of the innovative product and that of the existent brand on the shared attributes. However, the innovative product will be perceived as more dissimilar to the existent brand (contrast) when there is no overlap between two interpretation ranges on the shared attributes. For incremental innovation, context effects of the existent brand on the innovative product are more likely to occur because most of the attributes in the incremental innovation are shared with the existent brand.

According to Dimensional Range Overlap Model, if the perception of the prime can not be applied to the evaluative dimension of the target, the context effect will not occur on that particular evaluative dimension. Therefore, for a radical innovation sharing fewer attributes with the existent brand, the biased judgment can occur only on the shared attributes, and no context effect will be expected on the unique attributes to which only the radical innovation is applicable.

Marketers should be aware of the potential context effect of the existent brand on the innovative product, because various consumers’ evaluations on the innovative product can be manipulated by different marketing strategies. According to the theoretical framework proposed in this study, the innovative product, be it incremental or radical, can be judged in a direction more similar to the existent brand or dissimilar to the existent brand. The following examples show that perceptions of the innovative product can be manipulated in accordance with particular marketing goals.

If an incremental innovation is designated to position as a far more advanced product in order to differentiate itself from the incumbent competitors, what can be a better move? According to the suggestions of this study, marketers should try to produce contrast effect so that the perception of the incremental innovation can be shifted away from the existent brand or competitor brand. To produce contrast effect, marketers should make the overlapped attributes so salient that the non-overlapped attributes become accessible during the evaluation of the innovative product. At the same time, marketers should try to reduce the possible assimilation effect so that the perception of the incremental innovation will not be shifted toward the existent brand or competitor brand. To reduce the possible assimilation effect, marketers should make the overlapped attributes less salient so that the overlapped attributes will not be accessible during the evaluation of the innovation product. Therefore, to position an incremental innovation as a far more advanced product, marketers can focus on promoting the non-overlapped attributes while inhibiting the exposure of overlapped attributes.

In another example, if a radical innovation is introduced to a mainstream market in which the majority of potential customers are more conservative than counterpart customers in an early market, then consumers’ familiarity and confidence with the radical innovation become very important. Strong association between the radical innovation and consumers’ previous experiences on the existent brand may eliminate consumers’ fear and uncertainty about the radical innovation. In this particular case, marketers should try to produce assimilation effect so that the perception of the radical innovation will not be too different from that of the existent brand. To produce the assimilation effect, marketers should make the overlapped attributes as salient as possible so that the overlapped attributes become accessible during the evaluation of the radical innovation. According to the theoretical

framework proposed in this study, the interpretation range of the unique attribute will not be changed by the context effect on the shared attribute. Therefore, marketers should focus on promoting both the overlapped attributes to reduce consumers’ fear and uncertainty about the radical innovation and the unique attribute to emphasize the unique values and benefits delivered by the radical innovation.

VI. Limitation and Future Research

There are several limitations pertaining to the scope of this study. First of all, since this study focuses on the development of theoretical framework, no empirical measures are collected to further associate the proposed biasing judgment of innovative products with reliable and valid evidence obtainable in the causal research. Secondly, independently from the main stream research in context effect, Reciprocity Hypothesis (Hsiao, 2002) proposed that not only the perception of target (e.g. innovative product) might be biased due to the accessible information activated by prime (e.g. existent brand), but also the perception of prime might be shifted in a direction opposite to the biasing perception of target. That is, when the perception of innovative product (target) is assimilated toward the existent brand (prime), the perception of existent brand will be expected to shift toward the innovative product as well. However, when the perception of innovative product is contrasted away from the existent brand, the perception of existent brand will be expected to shift away from the innovative product. Such simultaneous perception shifts of innovative product and existent brand in the opposite directions are not discussed in the proposed theoretical framework. The potential future research may be directed to the two limitations mentioned above.

References

Atuahene-Gima, K. 1995. An exploratory analysis of the impact of market orientation on new product performance: a contingency approach. Journal of

Product Innovation Management. 12: 275-293.

Balachandra R., & J. H. Friar, 1997. Factors in success in R&D projects and new product innovation: A contextual framework. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management. 44(3): 276-287.

Chandy, R. K., & G. J. Tellis, 1998. Organizing for radical product innovation: The overlooked role of willingness to cannibalize. Journal of Marketing Research. 34: 474-87.

Chandy, R. K., & G. J. Tellis, 2000. The incumbent's curse? Incumbency, size, and radical product innovation. Journal of Marketing, 64(3): 1-17.

Chien, Y. 2002. Dimensional range overlap model for explanation of contextual

priming effects on product judgments. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,

Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

Chien, Y., & C. Hsiao, 2001. Dimensional range overlap model for explanation of contextual priming effects. Advances in Consumer Research, 28: 136.

Garcia, R., & R. Calantone, 2002. A critical look at technological innovation typology and innovativeness terminology: A literature review. Journal of

Herr, P. M. 1986. Consequences of priming: Judgment and behavior. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 51: 1106-1115.

Herr, P. M. 1989. Priming price: Prior knowledge and context effects. Journal of

Consumer Research, 16: 67-75.

Herr, P. M., Sherman, S. J., & R. H. Fazio, 1983. On the consequences of priming: Assimilation and contrast effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 19: 323-340.

Higgins, E. T. 1996. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology:

Handbook of basic principles: 133-168. New York: Guilford.

Higgins, E. T., Bargh, J. A., & W. Lombardi, 1985. The nature of priming effects in categorization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and

Cognition, 11: 59-69.

Higgins, E. T., & C. M. Brendl, 1995. Accessibility and applicability: Some “Activation Rules” influencing judgment. Journal of Experimental

Psychology, 31: 218-243.

Hsiao, C. 2002. The reciprocity hypothesis as an explanation of perception shifts in

product judgment, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Purdue University,

West Lafayette, Indiana.

Kessler, E. H., & A. K. Chakrabarti, 1999. Speeding up the pace new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 16: 231-247. Lee, M., & D. Na, 1994. Determinants of technical success in product development

when innovative radicalness is considered. Journal of Product Innovation

Management. 11: 62-68.

Mishra, S., Kim, D., & D. H. Lee, 1996. Factors affecting new product success: cross country comparisons. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 13: 530-550.

Olson, E. M., Walker, O. C., & R. W. Rueker, 1995. Organizing for effective new product development: The moderating role of product innovativeness. Journal

of Marketing. 59: 48-62.

Rangan, V. K., & K. Bartus, 1995. New product commercialization: Common mistakes, in V. K. Rangan et al. (eds.), Business marketing strategy: 66, Chicago: Irwin.

Srull, T. K., & R. S. Wyer, 1979. The role of category accessibility in the interpretation of information about persons: Some determinants and implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37: 1660-1672. Srull, T. K., & R. S. Wyer, 1980. Category accessibility and social perception:

Some implications for the study of person memory and interpersonal judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38: 841-856. Stapel, D. A., Koomen, W., & A. S. Velthuijsen, 1998. Assimilation or contrast?:

Comparison relevance, distinctness, and the impact of accessible information on consumer judgments. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(1): 1-24.