Abstract

The present study was conducted to establish the validity of the spritual distress scale (SDS), a scale developed as part of a qualitative study in which 20 cancer patients were interviewed in 2003–2004. The SDS has four domains: relations with self, relations with others, relations with God, and attitude towards death A measurement study was conducted whereby 85 patients completed the SDS during their hospitalization in the oncology unit of a medical centre in southern Taiwan. A purposive sample of cancer patients was recruited in the oncology unit of a medical centre hospital in southern Taiwan. The SDS, including four domains of sub-scales, was broader than other spiritual scales in the literature that only contained one or two domains and focused on the health area. The SDS has established the adequate content and construct validity. Further training of nurses for assessing spiritual distress of cancer patients using the SDS would be recommended for future study. The established content and construct validity of the SDS could be applied in oncology for nurses to assess spiritual distress of cancer patients.

Key words: Spiritual scales l Spiritual wellbeing l Cancer patients

l Content validity index

C

ancer has ranked as the leading cause ofdeath for Taiwanese people since 1982. In 2006 the mortality rate in Taiwan was 166.5 persons per 100 000 of the population. The mortality rate of cancer for males was 1.7 times as much as that for females (Department of Health Executive Yuan, 2006).

Many patients who are on the journey from receiving a cancer diagnosis to facing death will require spiritual care. Taylor (2006) measured the spiritual needs of 156 patients with cancer, and identified that positive loved others, finding meaning, and relating to God were the most important spiritual needs that were directly cor-related to the patient’s desire for nurse help. In light of this, spiritual care for cancer patients is an essential issue to nurses. Chung et al (2007) proposed that nurses’ integration of spiritual care is positively correlated to their understanding and practices of spiritual care. During spiritual care, nurses can discuss the patients’ beliefs and values, increase patients’ awareness of their own spiritu-ality, and empower each unique patient to find

meaning and purpose during illness (Baldacchino, 2006; Pesut and Thorne, 2007).

However, spiritual care is difficult to involve in the nursing process because there is no clear cut definition of spiritual care; no such clear defini-tion was found after interviewing specialists in oncology, cardiology and neurology, nurses, patients, and hospital chaplains (Pesut and Sawatzky, 2006; van Leeuwen et al, 2006). The major spiritual scales described in the literature focused on wellbeing and health, while few stud-ies explored spiritual distress. Establishing a spir-itual distress scale for cancer patients is important because health-oriented spiritual scales may not be able to reflect feelings of distress in the illness stage. The first author conducted a qualitative study by interviewing 20 patients with incurable cancer, and developed a spiritual distress scale (SDS) with four domains: relations with self, rela-tions with others, relarela-tions with God, and atti-tude toward death, in the period of 2002–2003 (Ku, 2005). The present study was conducted to establish the validity of the SDS.

Literature review

A literature search of nursing texts from 1980– 2009 revealed that several types of spiritual scales exist, relating to a number of subjects. Paloutzian and Ellison (1982) developed the spiritual wellbe-ing scale—the first published spiritual scale in nursing literature. Paloutzian and Ellison devel-oped a 20-item Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) compar-ing religious wellbecompar-ing and existential wellbecompar-ing dimensions of spirituality. The following year, Ellison (1983) reported that religious wellbeing was not significantly correlated with existential wellbeing (r=0.32), which means that the two sub-scales were independent of each other. In addition, Laubmeier et al (2004) studied the role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment of 95 cancer patients, and results indicated that the spiritual wellbeing scale and perceived life threat were not significantly correlated with each other; however, the impact of spirituality on anxiety/

Ya-Lie Ku PhD student,

University of Illinois at Chicago, United States, and Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, Fooyin University; Shih-Ming Kuo is Instructor, School of Environment and Engineering Science, Fooyin University, and

Ching-Yi Yao is Head

Nurse of Cancer and Hospice Care, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung County, Taiwan, Republic of China

Establishing the validity of a spiritual

distress scale for cancer patients

hospitalized in southern Taiwan

depression and quality of life was significant. Moberg (1984) developed an index of spiritual wellbeing with seven factors: Christian beliefs, self-satisfaction, personal faith, subjective spirit-ual wellbeing, optimism, cynical attitudes, essen-tialism. Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale ranged from 0.60 to 0.86 (Frank-Stromborg and Olsen, 1997). Poloma and Pendleton (1991) developed three prayer scales, including types of prayer activities, prayer experiences, and atti-tudes toward prayers. Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale was 0.85. Meraviglia (2002) tested three prayer scales for 30 cancer patients and found that scores on the three prayer scales were moderately correlated with perceived relationship with God; low levels of functional status were related to more prayer activity, and low levels of physical health status were related to more prayer experiences. Furthermore, Meraviglia (2004) adapted three prayer scales to 60 lung cancer patients—with Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale as 0.94. Higher prayer scores were associated with greater psychological wellbeing; prayer mediated the relationship between current physi-cal health and psychologiphysi-cal responses.

In addition to the spiritual wellbeing scale, spiritual wellbeing indexes, and the three prayer scales, Hungelmann et al (1996) developed a JAREL spiritual wellbeing scale with 21 items and three factors: faith/beliefs, life/personal responsibility, and life-satisfaction/self-accom-plishment. In addition, Hermann (1997) devel-oped a spiritual needs inventory for 100 dying patients that included 17 items with six factors: need for religion, companionship, need to finish business, involvement and control, need to expe-rience nature, and positive outlook. Cronbach’s alpha of the spiritual needs inventory was 0.85, while correlation between sub-scales was low and factor analysis indicated that the sub-scales explained 63.7% of the variance.

Furthermore, Chiu (2002) developed the good death scale with 18 items, and the content valid-ity index ranged from 0.65 to 0.95. The critical ratio for item discrimination analysis of this scale was from 2.31 to 5.33, and criteria-related valid-ity ranged from 0.14 to 0.87.

Yong et al (2008) developed and validated a spiritual needs scale for Korean cancer patients. The authors reviewed the literature for the con-tent of spiritual needs and conduct. A qualitative interview was conducted with six constructs extracted as: love and connection, hope and peace, meaning and purpose, religious rituals, relationship with God, and acceptance of dying. The original 37 items were evaluated by experts from palliative care and research methodology

Age

17–84 years, (median=45.9, standard deviation=15.1) Other variables:

n

(%) Sex Male: 57(67.1) Female: 28(32.9) Marital status Single: 21(24.8) Married: 49(57.5) Divorce: 10(11.8) Widow: 5(5.9) Education Illiterate: 3(3.5) Elementary: 16(18.8)High school: 44(51.8) Associate degree: 11(12.9)

College: 10(11.8) Graduates: 1(1.2)

Religion

Buddhism: 44(51.7) Taoism: 25(29.4)

Christian: 5(5.9) Catholic: 1(1.2)

Yi Guan Dao: 2(2.4) Other: 8(9.4)

Employment status Yes: 46(54.1) No: 39(45.9) Occupation Fishing: 1(1.2) Farming: 11(12.9) Labour: 21(24.7) Business: 14(16.5) Teaching: 5(5.9) Other: 33(38.8) Income <20000: 44(51.8) 20000–40000: 26(30.6) 40000–60000 :8(9.4) >60000: 7(8.2) Main caregiver Parents: 22(25.8) Siblings: 12(14.1)

Friends: 3(3.5) Nurses aides: 2(2.4)

Self: 10(11.8) Other: 36(42.4)

Years since cancer diagnosis

0–5 years: 81(95.2) 6–10years: 3(3.6) >10 years: 1(1.2) Number of hospitalizations 0–5: 53(62.3) 6–10: 25(29.4) 11–15: 4(4.7) 16–20: 2(2.4) >20: 1(1.2) Length of hospitalizations

Half a month: 25(29.4) Half-1 month: 25(29.4)

1–2 months: 24(28.3) >2 months: 11(12.9)

Methods of treatment

One kind: 30(35.3) Two kinds: 31(36.4)

Three kinds: 18(21.2) Four kinds: 6( 7.1)

Table 1. Demographics of the sample (n=85)

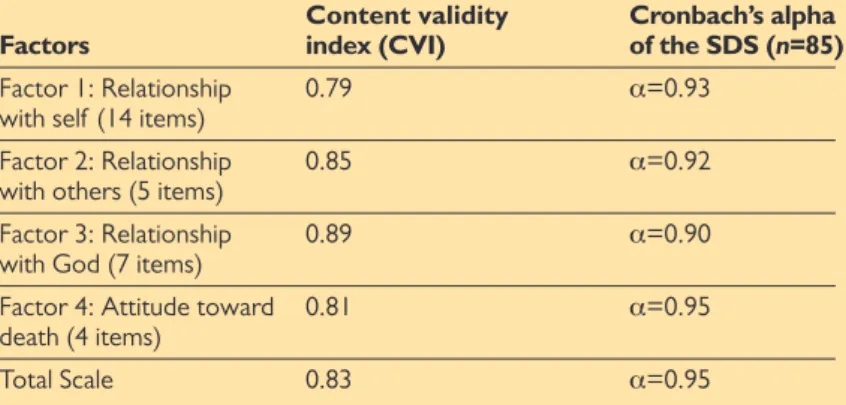

Content validity Cronbach’s alpha Factors index (CVI) of the SDS (n=85)

Factor 1: Relationship 0.79 a=0.93

with self (14 items)

Factor 2: Relationship 0.85 a=0.92

with others (5 items)

Factor 3: Relationship 0.89 a=0.90

with God (7 items)

Factor 4: Attitude toward 0.81 a=0.95

death (4 items)

Total Scale 0.83 a=0.95

Table 2. Content validity index and Cronbach’s alpha of the

spiritual distress scale

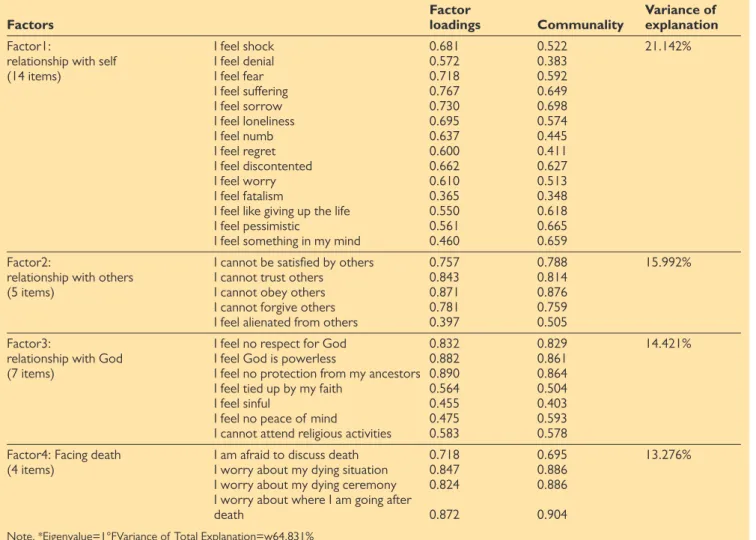

Factor Variance of Factors loadings Communality explanation

Factor1: I feel shock 0.681 0.522 21.142%

relationship with self I feel denial 0.572 0.383

(14 items) I feel fear 0.718 0.592

I feel suffering 0.767 0.649 I feel sorrow 0.730 0.698 I feel loneliness 0.695 0.574 I feel numb 0.637 0.445 I feel regret 0.600 0.411 I feel discontented 0.662 0.627 I feel worry 0.610 0.513 I feel fatalism 0.365 0.348

I feel like giving up the life 0.550 0.618

I feel pessimistic 0.561 0.665

I feel something in my mind 0.460 0.659

Factor2: I cannot be satisfied by others 0.757 0.788 15.992%

relationship with others I cannot trust others 0.843 0.814

(5 items) I cannot obey others 0.871 0.876

I cannot forgive others 0.781 0.759

I feel alienated from others 0.397 0.505

Factor3: I feel no respect for God 0.832 0.829 14.421%

relationship with God I feel God is powerless 0.882 0.861

(7 items) I feel no protection from my ancestors 0.890 0.864

I feel tied up by my faith 0.564 0.504

I feel sinful 0.455 0.403

I feel no peace of mind 0.475 0.593

I cannot attend religious activities 0.583 0.578

Factor4: Facing death I am afraid to discuss death 0.718 0.695 13.276%

(4 items) I worry about my dying situation 0.847 0.886

I worry about my dying ceremony 0.824 0.886

I worry about where I am going after

death 0.872 0.904

Note. *Eigenvalue=1°FVariance of Total Explanation=w64.831%

Table 3. Factor analysis of the spiritual distress scale (n=85)

for the content validity. A pilot test was con-ducted with 50 cancer patients to exclude 11 items. The spiritual needs scale was formally tested with 257 Korean cancer patients. Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale was 0.92 and five factors were identified, including needs in praying, listening to sacred music or scripture reading, participating in religious rituals and services, feeling God’s presence, and receiving forgiveness from God.

Methods

Design

A measurement study was undertaken whereby patients completed the SDS during their hospital-ization in the oncology unit of a medical centre in southern Taiwan.

Study population

A purposive sample of cancer patients was recruited in the oncology unit of a medical centre hospital in southern Taiwan. Participants were included if they had been diagnosed with cancer, had received cancer treatment, had a stable

con-dition, were conscious and alert, and could com-municate in Chinese or Taiwanese.

Data collection and measurement

Data were collected when potential subjects were admitted into the oncology unit between August 2004 and July 2005. The SDS was administered by the research nurse both to the participants who could complete the SDS on their own, and to those who could do so with the help of the research nurse (reading the questions). The SDS was devel-oped through a qualitative study by interviewing 20 incurable cancer patients in 2003 (Ku, 2005). The SDS is a self-reporting, 30-item instrument with four domains: relations with self (14 items), relations with others (5 items), relations with God (7 items), and the attitude towards death (4 items). Each item is scored from 1 to 4. The possible range of scores is 30–120. Higher scores indicate a higher level of spiritual distress.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the institutional research committee board of the medical centre.

All participants were given information about opportunities to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason and were told that there were no disadvantages of withdrawal. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. Each participant signed the consent form follow-ing discussion with the nursfollow-ing researchers.

Results

Demographics of participants

A total of 100 cancer patients were invited to participate in the study, but only 85 did so. The ages of the participants ranged from 17–84 years, with an average of 45.9 years. Further demo-graphics can be found in Table 1.

Content validity and internal

consistency

Four health practitioners in the cancer and hos-pice units graded the SDS as an acceptable scale, and the content validity index for four domains ranged from 0.79 to 0.89. The total scale’s con-tent validity index was 0.83. For internal consist-ency, the Cronbach’s alpha of the SDS among 85

cancer patients for four domains ranged from 0.90 to 0.95, and the total scale reached 0.95. The content validity index and Cronbach’s alpha of the SDS are listed in Table 2.

Factor analysis

Principal component analysis with Eigenvalue 1 on Varimax rotation including Kaiser normaliza-tion was performed, which found that the SDS consisted of 30 items with four domains compris-ing 64.831% explanation of total variance. According to Hair et al (1995) factor loading over 0.60 is within the significant level for a sam-ple size of 85 cancer patients; however, 0.30 is the generally acceptable level. All factor loadings among the 30 items of SDS were over 0.30. A total of 66.7% were over 0.60, and communality ranged from 0.348 to 0.904. For factor 1, 14 items represented the cancer patients’ relation-ship with self, which explained 24.142% of total variance. Five items were in factor 2, measuring the cancer patients’ relationship with others, which explained 15.992% of total variance. Seven items in factor 3 represented the cancer

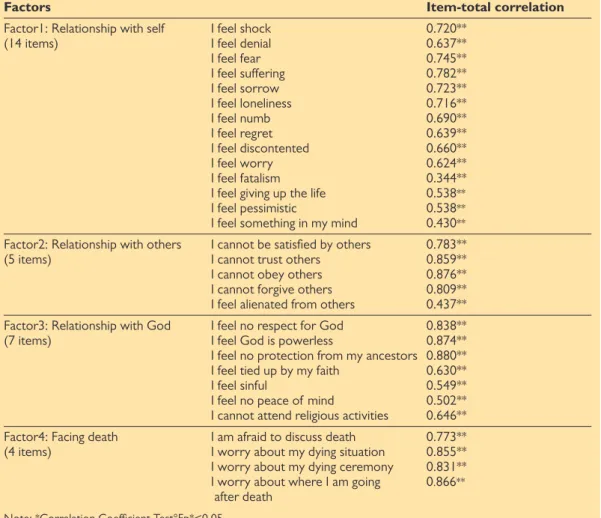

Factors Item-total correlation

Factor1: Relationship with self I feel shock 0.720**

(14 items) I feel denial 0.637**

I feel fear 0.745** I feel suffering 0.782** I feel sorrow 0.723** I feel loneliness 0.716** I feel numb 0.690** I feel regret 0.639** I feel discontented 0.660** I feel worry 0.624** I feel fatalism 0.344**

I feel giving up the life 0.538**

I feel pessimistic 0.538**

I feel something in my mind 0.430**

Factor2: Relationship with others I cannot be satisfied by others 0.783**

(5 items) I cannot trust others 0.859**

I cannot obey others 0.876**

I cannot forgive others 0.809**

I feel alienated from others 0.437**

Factor3: Relationship with God I feel no respect for God 0.838**

(7 items) I feel God is powerless 0.874**

I feel no protection from my ancestors 0.880**

I feel tied up by my faith 0.630**

I feel sinful 0.549**

I feel no peace of mind 0.502**

I cannot attend religious activities 0.646**

Factor4: Facing death I am afraid to discuss death 0.773**

(4 items) I worry about my dying situation 0.855**

I worry about my dying ceremony 0.831** I worry about where I am going 0.866** after death

Note: *Correlation Coefficient Test°Fp*<0.05

patients’ relationship with God, which explained 14.421% of total variance. Four items in factor 4 dealt with cancer patients’ attitude towards death, which explained 13.276% of total variance. The item-total correlations of four sub-scales were all over 0.30 with the significant levels of P<.001, which showed that each item was correlated with its sub-scale in the significant level. Factor analysis and items-total correlation of SDS are displayed in

Table 3 and Table 4 respectively.

Discussion and conclusions

The SDS in this study included the four sub-scales of cancer patients’ relationship with self, relation-ship with others, relationrelation-ship with God, and atti-tude towards death. The first sub-scale of the SDS is similar to existential wellbeing, while the third sub-scale is comparable to religious wellbeing (Paloutzian and Ellison, 1982) and the three prayer scales (Poloma and Pendleton, 1991). Moberg’s indexes of spiritual wellbeing (Frank-Stromborg and Olsen, 1997), the JAREL spiritual wellbeing scale (Hungelmann et al, 1996), and Hermann’s spiritual needs index (1997) are similar to the first and third sub-scales of the SDS. Additionally, the spiritual needs scale (Yong et al, 2008) is similar to the first, third, and fourth sub-scales of the SDS. Finally, the fourth sub-scale of the SDS is similar to Chiu’s (2002) good death scale. Only the second sub-scale of the SDS is unique among the spiritual scales reviewed in the literature, which measured relationships with oth-ers. The importance of relationships with others for spirituality is that through interaction with people, cancer patients can identify their own existence and see themselves as unique people, of value to others.

From the literature review, the focus of the majority of spiritual scales such as the spiritual wellbeing scale and SHS were found to be health-oriented. Also, some studies tested either the rela-tionship between spirituality and the psychological situation, or the impact of spirituality on psycho-logical adjustments. Overall, the SDS was broader than other spiritual scales in the literature that only contained one or two domains and focused on the health area. The SDS has a holistic perspec-tive combining these domains, and also patients’ relationship with others, which is unique to SDS. Besides, the SDS has established the adequate con-tent and construct validity. Further training of nurses for assessing spiritual distress of cancer patients by the SDS would be recommended for the future study. Further, the established content and construct validity of the SDS could be applied in oncology for nurses to assess spiritual distress of cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the nursing department of Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for approving and support-ing this study. Special thanks are given to all 85 cancer patients for their participation.

Baldacchino DR (2006) Nursing competencies for spiritual care. Journal of Clinical Nursing 15(7): 885–96 Chiu YW (2002) Construction of good death index: A

pre-liminary and pilot study in hospice palliative medicine. Unpublished master’s thesis. Chung Shan University, Taichung, Taiwan

Chung LYF, Wong FKY, Chan MF (2007) Relationship of nurses’ spirituality to their understanding and practice of spiritual care. J Adv Nurs 58(2): 158–70

Department of Health Executive Yuan (2006) Health Sta-tistics in Taiwan 2006. Part II Statitics on Causes of Death. DHEY, Republic of China http://www.doh.gov. tw/ufile/doc/Chapter%202.pdf (accessed 18 March 2010)

Ellison C (1983) Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Psychology and Theology

11(4): 330–40

Frank-Stromborg M, Olsen SJ (1997) Instrument to meas-ure aspects of spirituality. In: Ellerhorst-Ryan JM, ed.

Instruments for Clinical Health-care Research. 2nd edn.

Jones and Bartlett, Boston

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1995)

Mul-tivariate Data Analysis. 4th edn. Prentice Hall, New

York

Hermann CP (1997) Spiritual needs of dying patients: A methodological study. Unpublished doctoral disserta-tion, University of Kentucky

Hungelmann J, Kenkel-Rossi E, Klassen L, Stollenweark R (1996) Focus on spiritual well-being: Harmonious inter-connectedness of mind-body-spirit-use: Assessment of spiritual well-being is essential to the health of individu-als. Geriatric Nursing 17(6): 262–6

Ku YL (2005) Spiritual distress experienced by cancer pa-tients-develop a spiritual care for cancer patients.

Tai-wan Journal of Hospice Palliative Care 10(3): 221–33

Laubmeier KK, Zakowski SG, Bair JP (2004) The role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment to cancer: A test of the transactional model of stress and coping. Int

J Behav Med 11(1): 48–55

Meraviglia MG (2002) Prayer in people with cancer.

Can-cer Nurs 25(4): 326–31

Meraviglia MG (2004) The effects of spirituality on well-being of people with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum

31(1): 89–94

Moberg DO (1984) Subjective measures of spiritual well-being. Review of Religious Research 25(4): 351–64 Paloutzian R, Ellison C (1982) Loneliness, spiritual

well-being, and the quality of life. In Peplau L, Perlman D, eds. Loneliness: A Source Book of Current Theory,

Re-search, and Therapy. Wiley, New York: 224–37

Pesut B, Sawatzky, R (2006) To describe or prescribe: as-sumptions underlying a prescriptive nursing process ap-proach to spiritual care. Nursing Inquiry 13(2): 127– 34

Pesut B, Thorne S (2007) From private to public: negotia-tion professional and personal identities in spiritual care. Journal of Advanced Nursing 58(3): 396–403 Poloma MM, Pendleton BF (1991) The effects of prayer

and prayer experiences on measures of general well-be-ing. Journal Psychological and Theology 19: 71–83 Taylor EJ (2006) Prevalence and associated factors or

spir-itual needs among patients with cancer and family car-egivers. Oncol Nurs Forum 33(4): 729–35

van Leeuwen R, Tiesinga LJ, Post D, Jochemsen H. (2006) Spiritual care: implications for nurses’ professional re-sponsibility. Journal of Clinical Nursing 15(7): 875–84 Yong J, Kim J, Han SS, Puchalski CM (2008) Development

and validation of a scale assessing spiritual needs for Korean patient with cancer. Journal of Palliative Care

24(4): 240–6