CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this chapter, the results of the various analyses will be provided to answer the research questions. Section 4.1 examines the relationship between L2 proficiency and learners’ implicature comprehension. Section 4.2 addresses the response patterns of high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners in implicature comprehension. Section 4.3 presents the distribution of inferential strategies used by learners in the process implicature interpretation. Section 4.4 discusses learners’ perceived difficulties when they derived implicature from the context.

4.1 Effect of L2 Proficiency on Implicature Comprehension

This section is to answer the first research question, which investigates the extent to which learners’ general L2 proficiency relate to their listening comprehension of conversational implicature. Regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between the independent variable, L2 proficiency, and the dependent variables, the scores in two implicature categories (i.e., Relevance-based and Formulaic-based implicatures). Table 4.1 displays the relationship between learners’ L2 proficiency and their implicature comprehension.

Table 4.1 Regression analysis of L2 proficiency effect on listening comprehension of conversational implicature (N===58) =

Standardize Coefficient (Beta) R Square t p Relevance-based 0.5 0.25 4.34 .000 Formulaic-based 0.55 0.30 4.93 .000

Note. L2 Proficiency was operationalized as learners’ scores of placement

test when they entered the university, ranging between 104.67 and 168.44.

* p < .01.

As shown in Table 4.1, L2 proficiency, operationalized as the scores of placement test, turned out to be a real predictor for the dependent variables examined:

scores of Relevance-base implicatures and scores of Formulaic-based implicatures at the significant level of .01. The obtained R-square of .25 for the scores of Relevance-based implicatures indicated that 25% of the variance was explained by L2 proficiency. For the comprehension of Formulaic-based implicatures, 30% of the variance was accounted for by L2 proficiency. These results indicated that there existed a moderately positive effect of L2 proficiency on learners’ listening comprehension of conversational implicature, which accord with the findings of Taguchi (2005, 2007) and Roever (2006).

In summary, section 4.1 presents the relationship between learners’ general L2 proficiency and their listening comprehension of conversational implicature. The results revealed a distinct effect of L2 proficiency on learners’ listening comprehension of conversational implicature, which supports the findings of previous research (Roever, 2006; Taguchi, 2005, 2007) that high-proficiency learners have better capability of comprehending the nonliteral meaning embedded in the implicature. Possible explanation for the positive L2 proficiency impact may be attributed to the “transient” nature of listening (Rost, 2005), which requires listeners

to engage in real-time comprehension while at the same time seeks the most relevant interpretation of the utterance. Sperber and Wilson (1995) claimed that in the process of utterance interpretation, the listener decodes the linguistic part of the utterance, searches for relevant contextual information to derive the proposition expressed, and finally implicature is operationalized to derive the intended meaning. This utterance-interpretation process is regarded as a universal phenomenon. However, when it comes to L2 context, the situation seems to be more complicated.

High-proficiency learners, being more competent in decoding the spoken utterance, may have more processing space to notice other contextual clues, such as paralinguistic cues, or background knowledge to facilitate their comprehension of the intended meaning. In contrast, low-proficiency learners, due to their deficient L2 proficiency, may be overwhelmed by the linguistic interpretation at the surface level, not to mention to achieve automatic control of the complicated cognitive process in implicature comprehension.

Another explanation for the positive proficiency effect may be related to the way L2 learners process language input. As Cook and Liddicoat (2002) claimed, high-proficiency learners, having developed higher-level language processing, can process both linguistic and contextual knowledge in pragmatic comprehension.

Low-proficiency learners; on the other hand, may rely only on bottom-up linguistic processing without noticing the pragmatic meaning. This claim seems to apply to the present findings in which high-proficiency learners could successfully notice the gap between the expressed meaning and the intended meaning because they had better control in higher-level language processing. Low-proficiency learners; however, may over-rely on linguistic cues, thus failing to comprehend the encoded implicature.

Although the result of positive L2 proficiency impact corresponds to previous research, the present findings are not consistent with Bouton’ s (1999) findings, in

which he claimed that L2 proficiency has little to do with learners’ performance of implicature test, and only the length of L2 exposure counts as a determining factor in the accuracy of implicature interpretation. Such an apparent contradiction may be accounted for by a number of possible explanations. First, the participants in Bouton’s research were all in ESL context; in other words, there was no other EFL comparison group included in his study. When Bouton claimed that his participants improved their implicature interpretation skill as the result of increased exposure to the target culture, it could also be explained by the fact that their L2 proficiency had also increased during their stay in the target culture. Thus, from Bouton’s results, it is indeed difficult to conclude that exposure to L2 context per se counts as an overriding factor accounting for learners’ improvement. Second, Bouton did not specify the age of his participants - both native speakers and non-native speakers. It is possible that participants with older ages have developed better command of sociopragmatic knowledge, which may lead them to different interpretation of the implicature. Third, unlike the present study, Bouton did not specify whether he had controlled the variable of participants’ prior L2 exposure in his study. Due to the lack of clear specification on the above concerns, Bouton’s (1999) findings should be treated with caution.

Providing a much more detailed examination of the above variables, the results of the present study suggest that even in an EFL context with limited exposure to L2 pragmatic convention and sociocultural practices, learners can still comprehend implicatures as their proficiency develops. This positive relationship between learners’ L2 proficiency and their pragmatic competence is in line with a considerable amount of ILP research (Blum-Kulka & Olshtan, 1986; Kerekes, 1992; Koike, 1996;

Maeshiba et al., 1996; Scarcella, 1979; Takahashi & Dufon, 1989; Trosborg, 1987),

use of language than low-proficiency learners in terms of pragmatic comprehension and performance.

4.2 Learners’ Response Patterns in Different Types of Implicatures

This section addresses the second research question, which examines whether learners in different proficiency levels differ in their response patterns when comprehending different types of implicatures. Section 4.2.1 presents descriptive analysis of learners’ comprehension scores. Section 4.2.2 compares the differences of learners’ response patterns in Relevance-based and Formulaic-based implicatures.

Section 4.2.3 examines learners’ response patterns in four subtypes of Relevance-based implicatures. Section 4.2.4 discusses whether there exist statistically significant differences in learners’ implicature comprehension

4.2.1 Descriptive analysis of learners’ comprehension scores

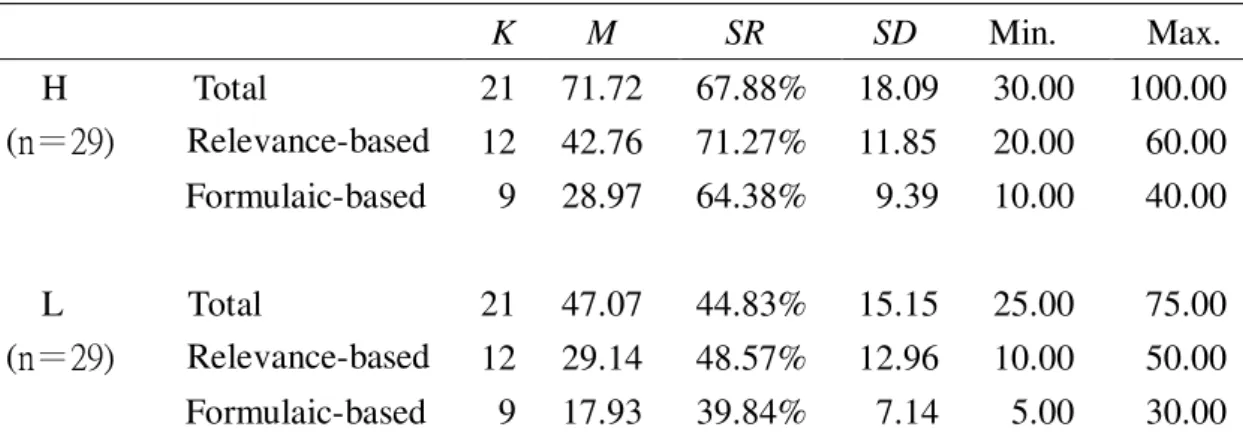

Table 4.2 displays descriptive statistics of the scores in Relevance-based and Formulaic-based implicatures.

Table 4.2 Descriptive Statistics for Comprehension Scores

K M SR SD Min. Max.

H Total

(n=29) Relevance-based Formulaic-based

L Total

(n=29) Relevance-based Formulaic-based

21 12 9 21 12 9

71.72 42.76 28.97 47.07 29.14 17.93

67.88%

71.27%

64.38%

44.83%

48.57%

39.84%

18.09 11.85 9.39 15.15 12.96 7.14

30.00 20.00 10.00 25.00 10.00 5.00

100.00 60.00 40.00 75.00 50.00 30.00 Note. H refers to high-proficiency learners. L refers to low-proficiency learners. K refers to the numbers of items in each category. SR refers to success rate of the items answered correctly. Five points were assigned for each correct answer made.

Descriptive statistics showed that high-proficiency learners outperformed low-proficiency learners in both Relevance-based and Formulaic-based implicatures.

In addition, both high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners performed better in the category of Relevance-based implicatures (i.e., success rate of 71.27%

for high-proficiency learners and 44.83% for low-proficiency learners) than in Formulaic-based implicatures (i.e., success rate of 64.38% for high-proficiency learners and 39.84% for low-proficiency learners).

Comprehension scores were compared between the two item categories (i.e., Relevance-based and Formulaic-based implicatures) by performing a one-way MANOVA in order to determine whether the observed difference in descriptive statistics was significant. The results of MANOVA yielded a significant difference for two groups of learners in both Relevance-based (Wilk’s Lambda = .622, F=17.45, p

<.01) and Formulaic-based (Wilk’s Lambda = .622, F=25.39, p<.01) implicatures.

The results of the present study indicated that Formulaic-based implicatures were observed to be more difficult for L2 learners to comprehend than Relevance-based implicatures, which corroborate the findings in Bouton’s studies (1994, 1999). As Bouton claimed, implicatures differ in opaqueness, and the extent of opaqueness partially depends on the fact whether the implicature is formulaic or not.

Formulaic-based implicatures, in general, are found to be more difficult for learners to comprehend in that the formula can be displayed in structure, semantics, pragmatics, or the combination of all. To comprehend Formulaic-based implicatures, learners are required to understand the relationship between the “formula” and its underlying meaning. Consider the following Formulaic-based implicature labeled as Understated Criticism (Bouton, 1988, p. 191).

(1) Item 13 (Two friends are looking over many kinds of food at a buffet restaurant and they are deciding which kinds of food to try.

Tracy: There are so many different kinds of food here and I can’t decide which to take first. Which one tastes good?

Dave: So far I’ve only had some of that one-the yellow one with reddish sauce.

Tracy: Oh, that looks good. Did you like it?

Dave: Well…, it’s colorful, isn’t it?

In the above example, the formula is revealed in the semantics in which Dave responds with a positive, but a peripheral remark to Tracy’s request. The response “It’s colorful, isn’t it?” is considered peripheral because in this context, it is how the food tastes that matters, not its appearance. Thus, when the speaker responds with the peripheral appearance, it is understood as an indirect criticism rather than a compliment. From this example, it demonstrates the complexity of comprehension process underlying the implicature: the learners are not only required to comprehend the linguistic part of the utterance, they are also required to determine what constitutes a “peripheral” feature according to the particular context they have encountered. Thus, even after years of exposure to the target culture, learners still find this type of implicature difficult to comprehend (Bouton, 1999).

Unlike Formulaic-based implicatures, the intended meaning of Relevance-based implicatures “idiosyncratically” relies on its unique utterance and its particular context (Bouton, 1994). This type of implicature is found to be easier for learners to comprehend as long as they understand the context and the underlying conversational principles violated. In other words, all learners have to do is seek the relevance of the implicature without contemplating the meaning of “formula” encoded in the implicature, and this relevance-seeking behavior, according to Sperber and Wilson (1995) is a universal phenomenon shared by human communication.

4.2.2 Relevance-based and three subtypes of Formulaic-based implicatures

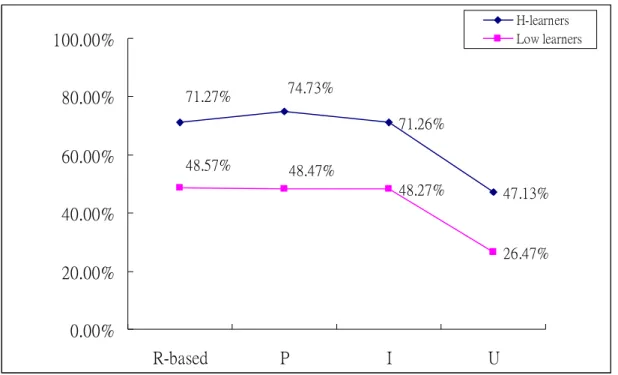

In order to gain a complete picture on the role of implicature type in implicature comprehension, learners’ response patterns in Relevance-based implicatures and three subtypes of Formulaic-based implicatures (i.e., Pope Q, Irony, and Understated Criticism) are further examined. Figure 4.1 graphically presents learners’

comprehension of these four types of implicatures.

71.27% 74.73%

71.26%

47.13%

48.57% 48.47%

48.27%

26.47%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

100.00%

R-based P I U

H-learners Low learners

Note. R-based refers to Relevance-based implicature. P refers to Pope Q. I refers to Irony.

U refers to Understated Criticism.

Figure 4.1 Learners’ comprehension of four types of implicatures

In Figure 4.1, the horizontal axis describes four types of implicatures and the vertical axis reveals the success rate of the items answered correctly. As displayed graphically in Figure 4.1, high-proficiency learners were observed to outperform low-proficiency

learners in all types of implicatures. In addition, the response patterns of two groups of learners were nearly identical, except for the rank order of Pope Q and Relevance-based implicatures. That is, both high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners comprehended most well in Pope Q (74.73% for high-proficiency learners and 48.47%

for low-proficiency learners) and Relevance-based implicatures (71.27% for high-proficiency learners and 48.57% for low-proficiency learners), slightly less well in Irony (71.26% for high-proficiency learners and 48.27% for low-proficiency learners), and noticeably least well in Understated Criticism (47.13% for high-proficiency learners and 26.47% for low-proficiency learners).

In accordance with previous findings (Bouton, 1994, 1999), learners comprehended relatively well in Relevance-based implicatures. As Bouton noted, Formulaic-based implicatures were systematically found to be more difficult for learners to comprehend than Relevance-based implicatures even after years of exposure to the target culture. In the present findings; however, only one type of Formulaic-based implicature (e.g., Understated Criticism) tuned out to be particularly difficult for learners to comprehend.

In fact, the success rate of the other two Formulaic-based implicatures (i.e., Pope Q &

Irony) was close to that of Relevance-based implicatures. Thus, the present study did not directly support Bouton’s findings.

In order to understand why two groups of learners comprehended Understated Criticism least well, detailed examination on learners’ response patterns was necessary.

Understated Criticism is often a response to value judgment in which the original information may contain offensive remark; thus, the speaker may choose to respond with a positive while peripheral feature of the things being evaluated (Bouton, 1999).

When learners encountered this type of implicature, they tended to interpret literally without knowing that the underlying meaning was actually an indirect criticism.

Consider example (2) and (3) below.

(2) Item 6 (Two teachers, Mr. Chen and Mrs. Liu are talking about a student’s term paper.)

Mr. Chen: Have you read Mark’s term paper?

Mrs. Liu: Yes, I read it last night.

Mr. Chen: What did you think of Mark’s term paper?

Mrs. Liu: I thought it was well typed.

H L How did Mrs. Liu like Mark’s term paper?

0% 10.3% (a) She liked the paper and she thought it was good.

37.9% 62.1% (b) She thought it was surely well typed.

41.4% 17.2% (c) She did (c) She did like the form, but not the content.

20.7% 3.4% (d) She didn’t like Mark’s term paper.

(3) Item 19 (Brenda and Sam are having lunch in a restaurant. They are talking about Brenda’s new dress.)

Brenda: I just got a new dress. How do you like it?

Sam: Well, this year there really are a lot of women wearing that dress.

H L What does Sam mean?

13.8% 27.6% (a) He is amazed that so many women are wearing this dress.

0% 6.9% (b) He thinks Brenda has good taste in clothes because she’s right in style.

51.7% 37.9% (c) He likes the dress, but too many women are wearing it.

34.5% 27.6% (d) He doesn’t like Brenda’s new dress very much.

In example (2), around 80% of the learners (79.3% for both high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners) interpreted Mrs. Liu’s response as a true compliment on the students’ term paper format. Only 20.7% of the high-proficiency learners grabbed the intended meaning. However, nearly all the low-proficiency learners misinterpreted Understated Criticism (with the success rates being 3.4%). Similarly, in example (3), learners either selected the literal meaning (so many women are wearing it) or interpreted the response as a compliment. Only about one third of the learners selected

the negative evaluation (34.5% for high-proficiency learners and 27.6% for low-proficiency learners). From learners’ response patterns, it appeared that learners’

poor comprehension in Understated Criticism may be explained by their failure to notice the “peripheral” or “unimportant” feature, which made the response as a negative evaluation rather than a positive one.

To sum up, section 4.2.2 presents learners’ response patterns in Relevance-based implicatures and three subtypes of Formulaic-based implicatures (e.g., Pope Q, Irony, and Understated Criticism). As described in the previous section (Section 4.2.1), Formulaic-based implicatures were found to be more difficult for learners to comprehend, and the results of the present section revealed that the difficulty mainly arouse from Understated Criticism. Understated Criticism was the only type of Formulaic-based implicature that was observed to be particularly difficult for learners to comprehend. The reason learners misinterpreted Understated Criticism can be attributed to the failure to recognize that the speaker is avoiding criticism by indirectly complimenting on some features of the item not central to the evaluation.

4.2.3 Four subtypes of Relevance-based implicatures

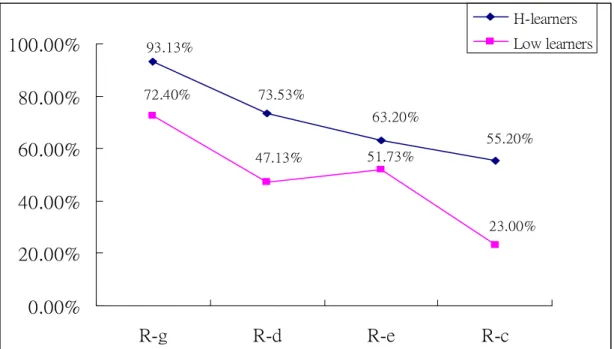

Due to the “idiosyncratic” nature (Bouton, 1999) of the Relevance-based implicatures in that implicatures derived in Relevance-based items are based on the relationship between the unique utterance and context, it is relatively more difficult to specify a general pattern in this category. In order to provide a clearer picture concerning learners’ response patterns in this special type of implicature, Relevance-based implicatures were further divided into two subcategories: responses violating Grice’s Relation maxim with no politeness concern (R-general) and responses violating Grice’s Relation maxim with politeness concern. The latter type was further categorized into three subtypes: responses given to evaluation (R-evaluation), responses

to disclose oneself (R-disclosure), and responses that totally change the topic (R-change). Learners’ comprehension of four subtypes of Relevance-based implicatures was presented in this section, as displayed graphically in Figure 4.2.

55.20%

63.20%

73.53%

93.13%

23.00%

51.73%

47.13%

72.40%

0.00%

20.00%

40.00%

60.00%

80.00%

100.00%

R-g R-d R-e R-c

H-learners Low learners

Note. R-g refers to Relevance-general implicature. R-d refers to Relevance-disclosure implicature.

R-e refers to Relevance-evaluation implicature. R-c refers to Relevance-change implicature.

Figure 4.2 Learners’ comprehension of Relevance-based implicatures

In Figure 4.2, the horizontal axis displays the 4 subtypes of Relevance-based implicatures and the vertical axis shows the success rate of the items answered correctly.

From this figure, it can be observed that, by and large, learners comprehend much better in implicature with no politeness concern (R-general: 93.13% for high-proficiency learners and 72.40% for low-proficiency learners) than implicatures with politeness concern (R-d, R-e, and R-c). Regarding the implicatures with politeness concern, the response patterns between high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners showed slight disparity: High-proficiency learners comprehended most well in responses to disclose oneself (Rd: 73.53%), followed by responses given to evaluation

(R-e: 63.20%), and they comprehended least well in responses that totally change the topic (R-c: 55.20%). Low-proficiency learners; however, comprehend most well in responses given to evaluation (R-e: 51.73%), followed by responses to disclose oneself (R-disclosure: 47.13%), and least well in responses that totally change the topic (R-c:

23%).

The general pattern indicated from Figure 4.2 can be explained in terms of the role of conventionality played in implicature comprehension. Conventionality is revealed through relatively fixed pattern of discourse exchange or language expression in a dialogue context and familiarity of these conventional features reduces the processing load required in implicature comprehension (Taguchi, 2005). Indirect refusal is one typical type of conventional implicature in which the speaker provides excuses to turn down the request of action. According to Holtigraves (1999), native speakers of English were observed to take less inferential time in interpreting conventional indirect refusal than other types of non-conventional implicatures. Consistent with previous research, the present findings showed that non-conventional implicatures, R-d, R-e, and R-c were proved to be difficult for both high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners to comprehend. Consider the following examples.

(4) R-disclosure

Item 8 (Sarah had heard that Larry was arrested for hitting a parked police car during the finals and she wants to know whether this was true.)

Sarah: I heard that you drank a lot at the end of term party. Is it true you got arrested for hitting a parked police car?

Larry: Well, um… It’s hard not to celebrate the end of semester.

(5) R-evaluation

Item 3 (Jack gave a party last week and Sandy attended. Jack wants to know what Sandy thought of the party.)

Jack: Sandy, how did you enjoy yourself at my party?

Sandy: Oh, um…you know, it’s hard to give a good party.

(6) R-change

Item 4 (Tina got her hair cut and styled. She wants to find out what Mark, Tina’s roommate, thinks of it and so she asks him.) Tina: Do you like my new hair style?

Mark: I was thinking, I’d like to have the apartment painted.

In the above examples, excuses were provided toward disclosure (example 4) and evaluation (example 5) in a non-conventional manner in which learners were required to utilize both linguistic and nonlinguistic cues in order to understand the intended meaning. Similarly, the response of example (6) was presented non-conventionally in that the response totally changed the topic discussed. Compared with R-d, R-e, and R-c, R-general was relatively more conventional in which the response was given in a more relevant fashion toward the previous utterance, as shown in the following example.

(7) R-general

Item 1 (One day, Jane and Tom are talking about Rudy.) Lars: Where is Rudy, Tom? Have you seen him this morning?

Tom: I think there’s a yellow Honda parked over by Sarah’s house?

Despite the fact that the above four subtypes of implicatures were all in the category of Relevance-based implicatures, the degree of conventionality and relevance was different. The present findings indicated that learners’ implicature comprehension was partially determined by the conventionality of the implicature items.

Although high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners revealed

interesting features worth being reported. First, there revealed small differences between high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners in R-e, indicating that two groups of learners responded similarly in this type of implicature. Detailed examination on learners’ response patterns was presented in the following to see why two groups of learners interpreted this type of implicature similarly. When comprehending R-e (response given to evaluation), both groups of learners seemed to understand that the speaker’s “circumlocution” may stand for negative evaluation, as shown in example (8).

(8) Item 3 (Jack holds a party, and he asks Sandy how thinks of the party) Jack: Did you enjoy yourself at my party?

Sandy: Um. It’s hard to give a good party.

H L What does Sandy mean?

0%

3.4%

27.6%

69.0%

3.4%

3.4%

41.4%

51.7%

(a) Jack holds good party. Sandy likes the party.

(b) Sandy understands Jack’s efforts on the party.

(c) Sandy means it’s not easy to throw a party everyone likes.

(d) Sandy doesn’t like the party very much.

In example (8), around 70% of the high-proficiency learners selected the expected answer “Sandy doesn’t like the party very much”, so did more than half of the low-proficiency learners (51.7%). However, 30% to 40% of the learners were distracted to the literal interpretation “It’s hard to give a good party”. When the “party evaluation”

context was displaced by the “assignment evaluation” context, more comprehension problems seemed to surface, as shown in example (9).

(9) Item 21 (May asks Mr. White how he thinks of her term paper)

May: Oh, Mr. White, I’m really curious to find out how I did on my term paper. What did you think of it?

Mr. White: Well, that was a very difficult assignment.

H L What does Mr. White mean?

44.8% 37.9% (a) Mr. White didn’t like May’s term paper very much.

27.6% 37.9% (b) Mr. White was just saying the assignment was difficult for many students.

27.6% 20.7% (c) Mr. White understood May must put much work into her paper.

0% 3.4% (d) May did a good job because the assignment was very difficult.

More than 55% of the learners were distracted to either the literal sense “The assignment was difficult” (27.6% for high-proficiency learners and 37.9% for low-proficiency learners) or the relevance of the difficult assignment that “You must put much effort on it” (27.6% for high-proficiency learners and 20.7% for low-proficiency learners). It is interesting to note that the implicatures encoded in example (8) and (9) are similar in semantics, that is, “something is difficult”; however, learners’

interpretation seemed to vary with the contexts. Unlike the “party evaluation” context, fewer learners interpreted Mr. White’s response as a negative evaluation in the

“assignment evaluation” context.

R-c is another type of implicature worth discussing here. From the descriptive analysis, R-c (response that totally changes the topic) revealed to be the most difficult implicature type for both high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners to comprehend among the Relevance-based subtypes. It is reasonable to speculate that the response of R-c, being the most irrelevant in the category of Relevance-based implicatures, may be the cause for learners’ comprehension problems. Detailed item

analysis was provided to examine learners’ response patterns. Consider the following examples.

(10) Item 2 (Martha asks Paul how well he did at golf today.) Martha: Hey, Paul. How did you do today at golf?

Paul: Man. Hm. I’m so tired of this cold weather.

H L What does Paul mean?

44.8% 20.7% (a) He didn’t play golf well today.

6.9% 13.8% (b) He didn’t go out to play golf, either.

6.9% 3.4% (c) He felt bored because Jane didn’t play with him.

41.4% 62.1% (d) He was just complaining about the bad weather.

(11) Item 4 (Tina got her hair cut and styled. She wants to find out what Mark thinks of it)

Tina: Do you like my new hair style?

Mark: I’d like to have the apartment painted.

H L What does Mark mean?

51.7%(a) Mark thi (a) Mark thinks Tina’s hair style is terrible. 17.2%

48.3% 34.5% (b) Tina’ hair doesn’t match the color of their apartment.

0% 41.4% (c) Mark thinks Tina’s hair style is good.

0% 6.9% (d) Mark wants Tina to paint the apartment with him.

Despite poor comprehension in R-c, high-proficiency learners, still, comprehended much better than L-learners. In example (10), high-proficiency learners (44.8%), more than twice as many low-proficiency learners (20.7%) interpreted the irrelevant response as negative information. In example (11), the percentage of high-proficiency learners (51.7%) choosing the expected answer was about three times as many low-proficiency learners (17.2%). In the case of irrelevant response, both groups of learners seemed to be less confident to interpret it as a negative response. Instead, they were either

distracted to select the literal interpretation (i.e., option d in item 2) or seek the relevance of the response as possible (i.e., option b, c in item 2 and option b, c, d in item 4).

In summary, section 4.2.3 presents learners’ response patterns in four subtypes of Relevance-based implicatures. It was found that implicatures without politeness concern (R-general) appeared to be much easier for learners to comprehend than implicatures involving the politeness factor (R-d, R-e, and R-c). This result can be attributed to the degree of conventionality encoded in the implicature items. When learners dealt with the more difficult types of Relevance-based implicatures (R-d, R-e, and R-c), two groups of learners shared a similar response pattern in R-e. In addition, both groups of learners comprehended least well in R-c.

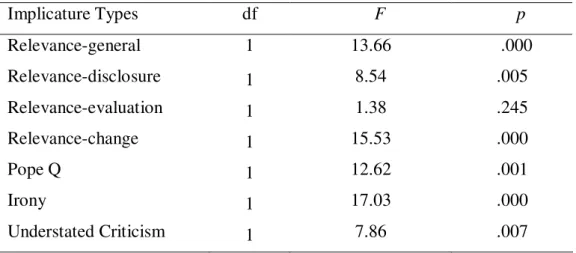

4.2.4 Comprehension Differences in Implicature Subtypes

In the above section, descriptive analysis was presented to show learners’

response patterns in different types of implicatures. In order to see whether the observed difference in descriptive statistics was statistically significant; namely, whether high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners comprehended significantly different in response to different types of implicature, one-way MANOVA was performed with learners’ L2 proficiency as independent variable, and seven implicature subtypes (i.e., Relevance-general, Relevance-disclosure, Relevance-evaluation, Relevance-change, Pope Q, Irony and Understated Criticism) as dependent variables. In general, the results of the one-way MANOVA revealed a significant difference for high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners in comprehending different types of implicatures. (Wilk’s Lambda=.53, F=6.27, p<.01).

As displayed in Table 4.3, among the seven implicature subtypes, high-proficiency

Relevance-general (F=13.66, p <.01), Relevance-disclosure (F=8.54, p < .01), Relevance-change(F=15.53, p<.01), Pope Q (F=12.62, p<.01), Irony (F=17.03, p

<.01), Understated Criticism (F=7.86, p<.01), but not in Relevance-evaluation (F=1.38, p=.245) and this result again corresponds to Figure 4.2 (p.51) presented in an earlier section (Success rate: 63.20% for high-proficiency learners and 51.73% for low-proficiency learners).

Table 4.3 Comprehension Differences in Seven Implicature Subtypes

Implicature Types df F p

Relevance-general 1 13.66 .000

Relevance-disclosure 1 8.54 .005

Relevance-evaluation 1 1.38 .245

Relevance-change 1 15.53 .000

Pope Q 1 12.62 .001

Irony 1 17.03 .000

Understated Criticism 1 7.86 .007

4.3 Learners’ Strategy Use in Different Types of Implicatures

This section addresses the third research question, which examines learners’

strategy use in response to different types of implicatures. Section 4.3.1 presents seven types of inferential strategies learners employed to interpret the implicatures. Section 4.3.2 compares strategy use difference between high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners.

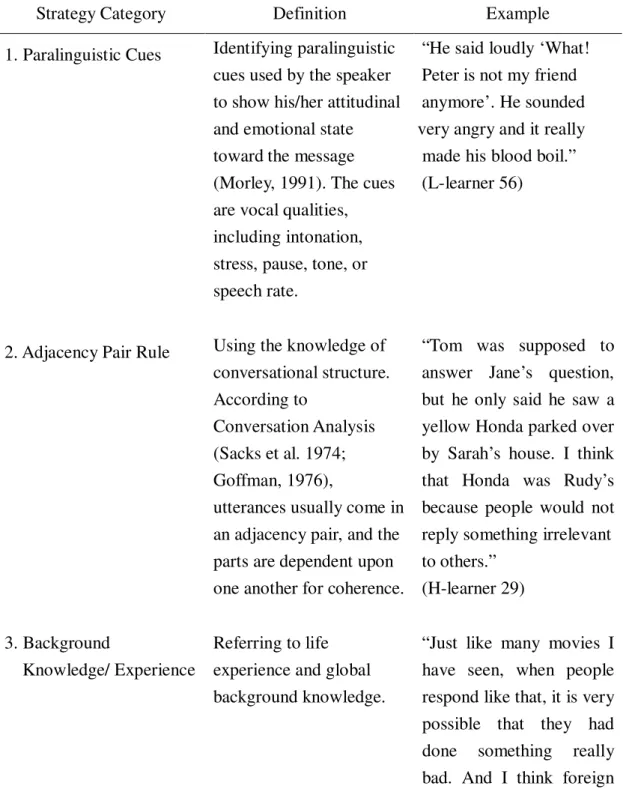

4.3.1 Seven Types of Inferential Strategies Used by Learners

A total of 363 strategy occurrences were found in Learners’ Inferential Strategy Questionnaires and they were identified into seven strategy types, including

paralinguistic cues (PC), adjacency pair rule (APR), background knowledge/experience (B&E), key word inferencing (KWI), logical reasoning (LR), speaker intention (SI), and testing tips (TT). Table 4.4 displays the strategy categories together with their representative examples.

Table 4.4 Inferential Strategies Used by Learners

Strategy Category Definition Example

1. Paralinguistic Cues Identifying paralinguistic cues used by the speaker to show his/her attitudinal and emotional state toward the message (Morley, 1991). The cues are vocal qualities, including intonation, stress, pause, tone, or speech rate.

“He said loudly ‘What!

Peter is not my friend anymore’. He sounded very angry and it really made his blood boil.”

(L-learner 56)

2. Adjacency Pair Rule Using the knowledge of conversational structure.

According to

Conversation Analysis (Sacks et al. 1974;

Goffman, 1976),

utterances usually come in an adjacency pair, and the parts are dependent upon one another for coherence.

“Tom was supposed to answer Jane’s question, but he only said he saw a yellow Honda parked over by Sarah’s house. I think that Honda was Rudy’s because people would not reply something irrelevant to others.”

(H-learner 29) 3. Background

Knowledge/ Experience

Referring to life experience and global background knowledge.

“Just like many movies I have seen, when people respond like that, it is very possible that they had done something really

students usually regard it normal; they don’t take it seriously.”

(H-learner 28)

4. Key Word Inferencing Catching a key word in the input and associating it with meaning.

“Tom said ‘I think…’

which means he knew something. Also I heard

‘Sarah’s house’ so I think Rudy may be at Sarah’s house.”

(L-learner 33)

5. Logical Reasoning Recognizing literal meaning and working deductively toward the implied meaning.

“Larry responded ‘It’s hard not to celebrate the end of semester’ so I think he indeed attended the party. He was confessing he got drunk and made a mistake.”

(H-learner 8)

6. Speaker Intention

7. Testing Tips

Understanding the

function of the implicature spoken by the speaker;

why and for what purpose the speaker used the implicature instead of a literal response.

Using testing tips developed by learners themselves to help them choose the correct answer.

“I think Sandy thought the party was not bad, but it

was far from perfection.

She could not say it directly because she didn’t want to break his heart (L-learner 43).

“I heard ‘where’ in the question, so I know the answer relates to the location. Among the options, only option C relates to location, so I

chose C. (L-learner 40)

4.3.2 Strategy Use Difference between H-learners and L-learners

In order to examine the differences between high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners’ use of inferential strategies, frequency and distribution of learners’ strategies were presented in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5 Frequency Distribution of the Inferential Strategies

PC APR B/E KI LR SI TT Total H-learners 40 45 8 2 68 43 0 206 L-learners 41 19 11 19 40 18 9 157

Note. PC = paralinguistic cues; APR = adjacency pair rule; B/E = background knowledge/experience; KI = key word inferencing; LR = logical reasoning; SI = speaker intention; TT = testing tips.

As shown in Table 4.5, except few strategy types (i.e., PC & B/E), high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners displayed different patterns in strategy use when comprehending implicatures. High-proficiency learners were found to use more adjacency pair rule (H: 45 incidences; L: 19 incidences), logical reasoning (H: 68 incidences; L: 40 incidences), and speaker intention (H: 43 incidences; L: 18 incidences), while key word inferencing (H: 2 incidences; L: 19 incidences) and testing tips (H: 0 incidences; L: 9 incidences) were more frequently used by low-proficiency

learners. This finding suggested that learners with different language proficiency demonstrated different preferences for strategy use in implicature comprehension, which is consistent with Taguchi’s (2002) findings.

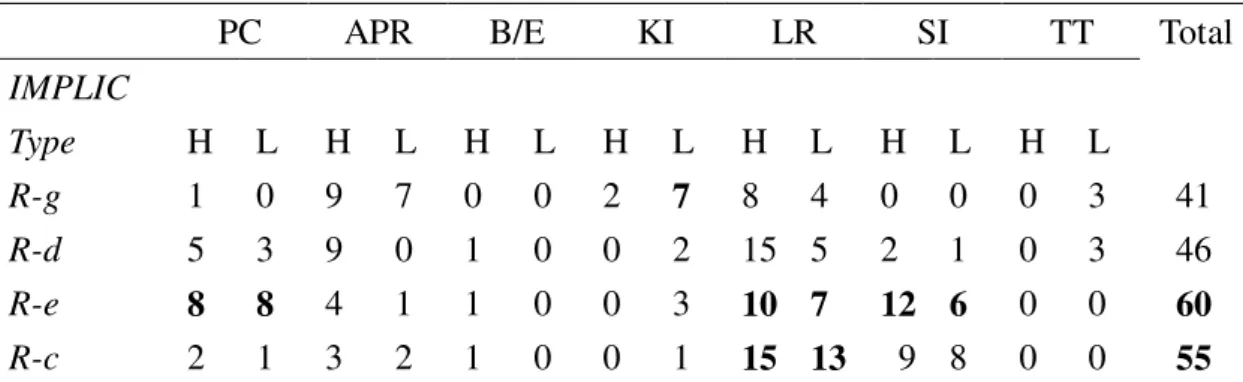

4.3.2.1 Learners’ Strategy Use in Relevance-based Implicatures

In order to understand how high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners employed inferential strategies to derive the implicature, a detailed examination on learners’ strategy use in each type of implicature is necessary. Table 4.6 displays the frequencies of learners’ strategy use in interpreting Relevance-based implicatures.

Table 4.6 Learners’ Strategy use in Relevance-based Implicatures

PC APR B/E KI LR SI TT

IMPLIC

Type H L H L H L H L H L H L H L

Total

R-g 1 0 9 7 0 0 2 7 8 4 0 0 0 3 41

R-d 5 3 9 0 1 0 0 2 15 5 2 1 0 3 46

R-e 8 8 4 1 1 0 0 3 10 7 12 6 0 0 R-c 2 1 3 2 1 0 0 1 15 13 9 8 0 0

60 55 Note. H= high-proficiency learners; L= low-proficiency learners; PC= paralinguistic cues;

APR= adjacency pair rule; B/E= background knowledge/experience; KI= key word inferencing; LR=logical reasoning; SI=speaker intention; TT=testing tips. Numbers in bold type are highlighted to show learners’ strategy use pattern.

As shown in Table 4.6, among the Relevance-based implicatures, it is particularly interesting to note that R-evaluation and R-change elicited noticeably more strategies, 60 and 55 incidences respectively, than R-general and R-disclosure did. The reason learners employed more strategies in these types of implicatures may be explained by the fact that R-evaluation and R-change, as has been demonstrated previously in section 4.2.3, were found to be two difficult implicature types for both high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners to comprehend. The results suggested that when learners found it difficult to derive the implicature, they tended to take advantage of other accessible contextual information to help them derive the intended meaning.

When learners interpreted R-evaluation, both high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners reported using frequent paralinguistic cues and logical reasoning to derive the implicature (See Table 4.6). However, high-proficiency learners seemed to advance to a higher-level inferential skill-recognizing speaker intention for producing the implicature. As can be seen in Table 4.6, high-proficiency learners were found to employ more speaker intention than low-proficiency learners did, as one of the high-proficiency learners responded (H-learners 18),

(12) Sandy said “It’s hard to give a good party.” It means that Sandy didn’t have a good time at this party, but she was embarrassed to say that to Jack.

When interpreting R-c, logical reasoning revealed to be the strategy most frequently employed by both high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners, through which they first interpreted the literal meaning of the utterance, searched for the relevance, and worked deductively toward the implicature, as shown in the following excerpts described by two learners.

(13) Since Jack said his boss looked sick, and he didn’t promise to drive Beth home, I think he was going to give his boss a ride home.

(H-learners 3)

(14) Jack said his boss was sick, so I think he would drive his boss home, not Beth. (L-learners 53)

Logical Reasoning, the most frequently used strategy in R-c, however, did not help

learners derive the intended meaning as learners had expected. The response of R-c, though categorized into Relevance-based implicatures, is in fact irrelevant to the

looks sick today instead of responding to the request (drive Beth home), he was in fact

totally changing the topic and avoiding the response. Thus, seeking the relevance was of little use to derive the implicature. Learners’ frequent use of logical reasoning may partly explain why they failed to recognize the intended meaning in R-c.

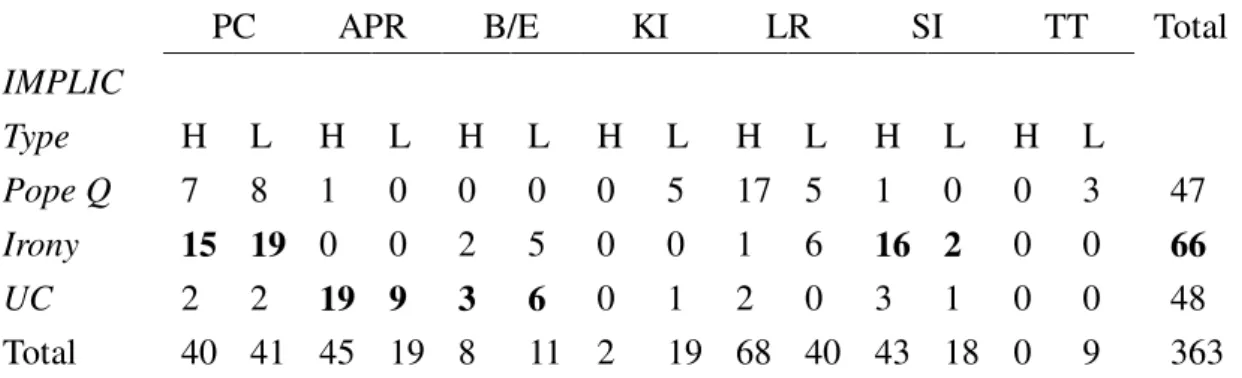

4.3.2.2 Learners’ Strategy Use in Formulaic-based Implicatures

Table 4.7 displays the distribution of learners’ strategy use in Formulaic-based implicatures.

Table 4.7 Learners’ Strategy Use in Formulaic-based Implicatures

PC APR B/E KI LR SI TT

IMPLIC

Type H L H L H L H L H L H L H L

Total

Pope Q 7 8 1 0 0 0 0 5 17 5 1 0 0 3 47

Irony 15 19 0 0 2 5 0 0 1 6 16 2 0 0 66

UC 2 2 19 9 3 6 0 1 2 0 3 1 0 0 48

Total 40 41 45 19 8 11 2 19 68 40 43 18 0 9 363 Note. H= high-proficiency learners; L= low-proficiency learners; PC= paralinguistic cues;

APR= adjacency pair rule; B/E= background knowledge/experience; KI= key word inferencing; LR=logical reasoning; SI=speaker intention; TT=testing tips. Numbers in bold type are highlighted to show learners’ strategy use pattern.

In the previous section (section 4.2), learners’ comprehension results showed that learners comprehended less well in Formulaic-based implicatures than in Relevance-based implicatures. Among the Formulaic-based implicatures, learners comprehended least well in Understated Criticism, a special type of implicature in which the speaker’s indirect criticism is encoded with a seeming compliment on a peripheral or an unimportant feature of something or someone being evaluated. Close examination on learners’ strategy use in Understated Criticism emerges an interesting

fact. Take item 13 for example. When the speaker was asked to comment on the food, he responded with It’s colorful, isn’t it? In the dialogue, the speaker neither responded with an unpleasant tone nor with a negative comment. Instead, the speaker made a compliment The food looks colorful. Since there were no apparent paralinguistic cues available to help learners interpret the implicature, they turned to employ adjacency pair rule. As can be seen in Table 4.7, both high-proficiency learners and

low-proficiency learners frequently employed adjacency pair rule as a clue to derive the intended meaning, as two of the learners responded,

(15) He did not directly say ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about the food, but only commented ‘colorful’. It is apparent that he was indirectly saying the food was not good. (H-learner 7)

(16) If he liked it, he could have directly said the food was good, but he didn’t. He only said that the food was colorful, which means he didn’t like it very much. (L-learner 51)

Note that high-proficiency learners employed two times as many adjacency pair rule as low-proficiency learners did (H: 19 incidences; L: 9 instances), which may probably explain why low-proficiency learners failed to comprehend Understated Criticism (with the success rate of 26.47% ). When low-proficiency learners failed to employ adjacency pair rule, some of the learners turned to their background knowledge or experience in

colorful food.

(17) Usually, food that is beautiful in appearance looks tastier. (L-learner 53) (18) I think the food tastes good because beautiful food usually increases the

appetite. (L-learner 43)

Another interesting point which deserves our attention is learners’ strategy use in Irony, which elicited most strategies (66 incidences) among the Formulaic-based implicatures. When learners interpreted Irony, high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners uniformly employed frequent paralinguistic cues, 15 and 19 instances respectively, as demonstrated in the following examples.

(19) This situation per se is quite illogical (how come my wife left with my good friend). In addition, Bill said “He really is my good friend”

and I can feel he particularly stressed the word “really”, which means

“How can you do this to my wife!” From his tone, apparently, he was not saying what he meant-it’s just a sarcasm. (H-learner 28)

(20) He said loudly “What! Peter is not my friend anymore”. He sounded very angry and it really made his blood boil. (L-learner 56)

Although previous research categorized Irony into difficult type of implicature (Bouton, 1999), the results of the present study did not support this claim. Descriptive statistics showed that learners were not found to comprehend less well in Irony (71.26% for high-proficiency learners and 48.27% for low-proficiency learners). In fact, learners’

success rate in Irony was close to that of Relevance-based implicature (71.27% for high-proficiency learners and 48.57% for low-proficiency learners). This finding could be explained by the fact that paralinguistic cues were accessible in Irony items to help learners interpret the implicature (See Table 4.7). In interpreting Irony, high-proficiency learners were also found to employ more upper-level inferential strategy-recognizing speaker intention for making the implicature. As shown in Table 4.7, 16 instances of speaker intention were employed by high-proficiency learners, which was eight times

as many as low-proficiency learners did. In the Inferential Strategy Questionnaires, high-proficiency learners were able to specify speaker intention behind the implicature,

such as “He was furious and he was just showing his sarcasm” (H-learner 4).

In summary, section 4.3 presents and compares the distribution of learners’

strategy use in implicature comprehension. Two generations can be derived from the above analysis. First, learners with different proficiency level were found to demonstrate different preferences for inferential strategy use. In general, high-proficiency learners employed more higher-level inferential strategies, such as adjacency pair rule, logical reasoning, and speaker intention. Low proficiency learners;

on the other hand, were found to employ more bottom-up strategies such as key word infenrencing and Testing Tips. This result is consistent with Taguchi’s (2002) findings,

in which he found that high-proficiency learners reported using more speaker intention, while low-proficiency learners reported using more key word inferencing and background knowledge/experience. This distinct strategy use not only demonstrated

learners’ preferences, it could also explain why learners comprehend less well in certain types of implicature. Closer examination on learners’ strategy use in difficult types of implicatures (Relevance-evaluation, Relevance-change, and Understated Criticism) suggested that when encountering difficult types of implicature, high-proficiency learners still held onto the adjacency pair rule principle and sought genuine speaker intention for the mismatch between what was said and what was meant. Low proficiency learners; however, when they encountered difficult types of implicature, they tended to search for the relevance at the surface level by either relating a key word to the possible interpretation (i.e., key word inferencing and Testing Tips), or by turning to their background knowledge/experience to justify the validity of the literal interpretation they chose. These results lent support to Sperber and Wilson’s (1995) claim that utterance interpretation is a relevance-seeking behavior, an “individual behavior”, in which the individual’s “preferences” and “abilities” shape the ways of

Second, it was found that the difficulty of the implicature per se was not the only factor resulting in learners’ misinterpretation. The accessibility of the contextual information also played an essential role in implicature comprehension. As discussed earlier, Irony, being categorized as a difficult implicature type in the previous literature (Bouton, 1999), was not found difficult at all for the learners to comprehend. In fact, descriptive statistics showed that learners’ success rate of Irony was close to that of Relevance-based implicatures (See Figure 4.1). This contradiction may be attributed to the fact that Irony items in the present study were accompanied with rich paralinguistic cues and familiar contexts, which had complemented learners’ inadequate interpretation skill and facilitated their comprehension. Similar finding was also observed by Gibbs (1994), in which he found that English native speakers could understand nonliteral utterance as quickly as, sometime even more quickly as literal uses of the same utterance in different contexts, provided that these expressions appeared in realistic social context. For instance, people could capture the ironic meaning of the utterance You’re a fine friend (meaning You’re a bad friend) immediately without additional cognitive effort. The easiness of people processing ironic remark is because people are often familiar with many ironic situations, and when they encounter similar contexts, they can understand the ironic remark without resorting to additional computation (Gibbs, 1994; Lucariello, 1994). Consistent with Gibb’s (1994) findings, the ironic remark in the present study That Peter knows how to really be good friend, doesn’t he?

was easily captured by the learners through the speaker’s ironic tone as well as the familiar ironic context (i.e., His wife had affairs with his good friend). As can bee seen in Table 4.7, learners employed frequent paralinguistic cues and speaker intention to help them derive the ironic meaning. These results once again suggested that if contextual information is accessible, L2 learners can even comprehend difficult types of implicature without additional cognitive effort.

4.4 Learners’ Difficulties in Implicature Comprehension

This section addresses the fourth research question, which investigates the source of learners’ difficulties in implicature comprehension. Interview protocols obtained from eight participants (four from low-intermediate class and four from advanced class) were analyzed and presented in terms of learners’ perceived difficulties when they comprehended different types of implicatures. Section 4.4.1 presents shared difficulties both high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners had encountered. Section 4.4.2 addresses difficulties particularly found in low-proficiency learners.

4.4.1 Difficulties Shared by Learners

The interview protocols revealed that both high-proficiency and low-proficiency learners encountered several difficulties when comprehending implicatures in the following three aspects: (1) implicature with little relevance, (2) literal interpretation and (3) learners’ assumption.

Implicature with little relevance. Both high-proficiency learners and low-proficiency learners were found to comprehend less well in the type of implicature with little relevance, which is titled “R-change” in the present task, as illustrated in the following example.

(21) Item 4 (Tina got her hair cut and styled and she wants to find out what Mark thinks of it.)

Tina: Do you like my new hair style?

Mark: I was thinking, I’d like to have the apartment painted.

When learners encountered the response that totally changes the topic, they still strived to find the relevance as possible. The following two extracts from a high-proficiency

learner and a low-proficiency learner demonstrated how they searched for relevance to help them interpret the implicature.

(22) H-learner 1: I heard the man said he wanted to help her repaint the apartment, so I think the man thought Tina’s hair color went wrong.

Researcher: Why do you think her hair goes wrong?

H-learner1: Um…at first, I think the man’s reply was really strange. He may think her hair color was strange so that he wanted to repaint the apartment to match her hair color.

(23) L-learner 43: Well, he probably thought the girl’s hair looked good so he planned to paint the apartment to make the apartment looked better. Um…painting the apartment could also mean the girl should have her hair restyled.

Researcher: So, you mean it could have two meanings concerning painting the apartment?

L-learner 43: What he really said was not the apartment, but her hair.

Painting the apartment was served as an analogy, which means her hair may look good or bad.

Whether learners interpreted Mark’s response as a positive or a negative comment, they failed to recognize the genuine speaker intention revealed in this type of implicature, that is, the speaker avoids giving negative response by totally neglecting the listener’s request of opinion. This result is consistent with learners’ strategy use in R-change discussed earlier (section 4.3.2.1), in which learners frequently employed logical reasoning to seek the relevance between the response and the request.

Literal interpretation. The second learners’ difficulty arose from their habitual use

of literal interpretation. Five out of the eight learners reported that they tend to match the answer with what they have literally heard in listening tests. Two learners reported that they are accustomed to employing this hear-match strategy in listening tests.

(24) Item 6 (Mr. Chen asks Mrs. Liu about a student’s term paper and Mrs. Liu responds,” I thought it was well typed.”)

H-learner 2: She only talked about his advantage (well typed), so I chose

“b”. Just like taking multiple choice tests, you don’t have to understand every option. If you hear something in the dialogue that you think is correct, then you just select the option that matches what you heard.

(25) Item 19 (Brenda asks Sam how he thinks of her new dress and Sam

responds, “Well, this year there really are a lot of women wearing that dress.”)

L-learner 43: I think there are two meanings. If it is the surface-level meaning, I will choose “c”, “He likes it, but too many women are wearing it.”

Researcher: What about the deep-level meaning?

L-learner 43: It’s like the daily questions we are asked about. For example, your friend may ask you “How do you like something?” Sometimes you may not like it very much, or you don’t have any opinions, you will just give a reply that everybody will give.

Researcher: Um… then why did you choose the surface-level meaning?

L-learner 43: When we take listening tests, we usually select the answer that we heard from the script. We won’t think so

complicatedly.

Example (24) and (25) showed that learners were inclined to interpret the implicature as literal meaning based on what they had literally heard in the context. This kind of hear-match strategy probably can explain why learners preferred to use bottom-up strategies when interpreting implicature, as one of the low proficiency learners commented, “I heard the word ‘hard’, then I saw a option with the words ‘not easy’, and I selected that option since ‘not easy’ is the synonym of ‘hard’.

Learners’ assumption. From the interview protocols, it was systematically found that learners were distracted toward the option that approximates their assumption in certain people and event. For example, learners were found to assume that “teachers” are supposed not to reveal subjective opinions toward students’

performance, as shown in the following excerpts.

(26) Item 6 (Mr. Chen asks Mrs. Liu about a student’s term paper and Mrs. Liu responds, “I thought it was well typed.”)

H-learner 4: I didn’t choose “d” (She didn’t like Mark’s term paper).

It’s too negative! When a teacher evaluates students’

assignment, the teacher will not give too many personal comments. Instead, the teacher is supposed to comment objectively, reporting the strength and weakness of the assignment, or the points that need improving. I think the teacher will not say “I like it!” or “I don’t like it!”

(27) Item 21 (May asks her teacher about her term paper and her teacher responds, “That was a very difficult assignment.”)

L-learner 57: The teacher meant “None of the students did well on the assignment, including her. That was a very difficult assignment for all students.”

Researcher: You mean her term paper was not good?

L-learner 57: Yeah. The teacher probably didn’t like it.

Researcher: Why didn’t you select option “a” (Mr. White didn’t like May’s term paper very much.)

L-learner 57: Since it was difficult, everyone didn’t do well. It was not related to the teacher’s preferences because the teacher was commenting the assignment according to general performance, not just to May alone.

Example (26) and (27) clearly demonstrated how learners’ assumption in “teachers”

influenced their interpretation of the implicature, that is, teachers’ comments on

students’ performance should be neutral and not involve personal preferences. Thus, when they faced this type of implicature, they could not capture the intended meaning behind the implicature — Your performance is far from satisfactory. Instead, they tended to interpret the utterance more like a comfort, as one of the learners (H-learner 3) noted, “She didn’t do well, but it’s not her fault since the assignment was difficult.

The teacher could understand it.”

Learners’ assumption was also demonstrated in the Relevance-evaluation context. Consider the following examples.

(28) Item 3 (Jack gave a party last week and he wants to know what Sandy thought of the party.)

Jack: Sandy, how did you enjoy yourself at my party?

Sandy: Oh, um…you know, it’s hard to give a good party.

(29) Item 10 (Nick asks Judy what she thinks of his paintings.) Nick: Judy, do you like my paintings?

Judy: Well, painting with oil is very difficult.

As discussed earlier (section 4.2.3), the responses in example (28) and (29) are nearly identical with the meaning “It is difficult to do something” except one context dealing with the evaluation towards the party, while the other towards the paintings. However, learners’ responses towards these two items were completely different. The following two excerpts were from a high-proficiency learner (H-learner 2).

(30) Item 3 (Jack asks Sandy how she thinks of the party and she responds, “It’s hard to give a good party.”)

H-learner 2: Sandy may not enjoy the party, but she didn’t want to say it directly that “The party sucks!”

(31) Item 10 (Nick asks Judy how she thinks of his paintings and she responds, “Painting with oil is very difficult.”)

H-learner 2: She said “Oil painting is difficult!”, which meant she understood his effort on it.

Researcher: Did she answer his question?

H-learner 2: Well…no. I don’t think she didn’t like his paintings.

When you appreciate someone’s paintings, it is very likely that you are not good at paintings. Since you know his effort on it, you will recognize his accomplishment.

Example (31) and (31) showed that learners perceived “party” and “painting”

differently. Learners tended to perceive “oil painting” as something difficult, which explains why they interpreted the response “Painting with oil is very difficult” as a true compliment. As one of the learners reported,

(32) L-learner 52: She said “Painting with oil is difficult”, which meant he did a good job to accomplish it. It is a positive comment.

However, when learners interpreted the implicature in the “party context”, they tended to regard the utterance “It’s hard to give a good party.” as a circumlocution for negative evaluation, as one of the high-proficiency learners noted,

(33) H-learner 1: Party is more of a “fun” thing and atmosphere is the most important part in a party. So, when you feel something goes wrong, you are not going to enjoy the party. It’s quite easy to judge a party: It’s either “fun”

or “sucks”!

Due to the fact that learners had different perceptions toward “party” and “painting”, it is not surprising to find that they had different standards towards the evaluation. As can be seen in the above examples, learners were inclined to see “oil painting” as something difficult to do; thus, no matter how well a person painted, he or she deserved the encouragement. “Holding a party”; on the contrary, was a completely different thing: A party is easier to be evaluated as “fun” or “not fun” since party per se is a “fun thing”. From this point, we can see that learner’ assumption plays an important role in their implicature comprehension.

4.4.2 Difficulties Found in Low-Proficiency Learners

This section focuses on difficulties low-proficiency learners had encountered in the process of implicature comprehension. From the analysis of interview protocols, it was found that low-proficiency learners systematically reported difficulties in the following three aspects: (1) language proficiency, (2) speaker intention, and (3) specific types of Formulaic-based implicature. It is essential to include a separate section to discuss difficulties that exclusively arise among low-proficiency learners because these difficulties can lead us to better understanding concerning the marked disparity between high proficiency and low proficiency learners.

Language proficiency. The interview protocols revealed that low-proficiency learners’ difficulties arouse mainly from inadequate language proficiency. Most of the

learners interviewed reported that their processing speed was not fast enough to follow the dialogue.

(34) L-1earner 55: My processing speed is very slow. When I heard the girl’s question and tried to process it, the other person had already spoken. So, I could not listen very clearly what he said.

In addition to low processing speed, learners’ inadequate language proficiency also led to wrong interpretation of the word, which was clearly demonstrated in the discourse marker “well”. Consider the following two excerpts.

(35) Item 19 (Brenda asks Sam how he thinks of her new dress and Sam responds, “Well, this year there really are a lot of women wearing that dress.”)

L-Learner 43: I heard the word “well”, which meant “good”. Also, he spoke in a quite “merry” tone. I don’t think he didn’t like the dress.

L-learner 55: The man didn’t sound like “He didn’t like it!”, and I heard the word “well”, which meant a positive reply—he liked that dress.

In example (35), learners misinterpreted “well” as literal meaning rather than a dispreferred marker, indicateing that the speaker is saving the listener’s face because the intended meaning of the following utterance contains negative information (Jucker, 1993). Dispreferred markers, such as “well”, are used to mitigate such face-threatening effect (Holtigraves, 1992).