241

What Is the Truth in Market Research? Being a Truth Teller

CHIEH-CHING TIEN

Graduate School of Art-Culture Policy and Management, National Taiwan University of Arts, Taiwan

ABSTRACT

Market research is recognised as having an important function in the turbulent business environment. In recent times the way market research is conducted has changed, with increasing use of qualitative as well as quantitative methods. Consequently, the main question has become, ‘What is the truth in market research?’ It is important for the researcher to be aware of their own philosophical position at the outset of the research.

Taking into account the writer’s own philosophical position and the distinctive features of market research, the view taken here is that there is no such thing as permanent truth. Although there has been debate about the relative merits of positivism and interpretivism, and traditionally positivism has occupied a central position in terms of research philosophy, there is now an increasing move towards interpretivism and the qualitative approach in market research. In seeking truth in marketing science, the role of the ‘truth-teller’ is to present an interpretation of social reality that will be accepted by the research subjects.

Key words: marketing research, positivism, interpretivism, research philosophy.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Development of Market Research

Market research is recognised as having an important function in the turbulent business environment. The findings yielded by market research provide information on the market and consumer expectations. The way market research is conducted has changed with increasing use of qualitative as well as quantitative methods. In the early stage, researchers used informal questionnaires combined with occasional trials. Later they adopted more formal techniques in an effort to improve the validity and reliability of results. They then moved from quantitative methods, the traditional approach of the natural sciences, to qualitative methods more typically used in social science research. Many social scientists are now involved in market research and are contributing to the development of philosophy and academic knowledge in the discipline (e.g. Anderson, 1986; Brown, 1996; Carson, Gilmore, Perry & Gronhaug, 2001; Goulding, 1999; Hunt, 2003; Low, Carr, Thomas &

Watkins-Mathys, 2005; Tadajewski, 2004). Two major paradigms have emerged among researchers: positivism and interpretivism. The former assumes that reality is external and objective and that truth exists; and the latter posits that the world is subjective and there is no permanent truth.

In the face of the battle between these two conflicting approaches, the main question is ‘what is the truth in market research?’ It is important for the researcher to be aware of their own philosophical position at the outset of the research.

242

1.2 The Purpose of Considering Research Philosophy

Considering research philosophy could help researchers answer the question

‘what is the truth in market research?’ According to Tarski, truth may be defined as the free use of the intuitive idea to correspond with the facts (Soames, 1989).

Researchers must be able to use their own judgement and learn to work efficiently and independently with the uncertainty and risk of research (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Lowe, 2002). An understanding of research philosophy could help researchers form a clearer picture about how and why research is implemented.

Carson et al. (2001) indicate that consideration of the philosophy of research can help researchers to see their research from a broader perspective, and to define more clearly the purpose of their specific project within the wider context.

Easterby-Smith et al. (2002) also explain how important it is to understand philosophical issues. They claim it can help researchers clarify their research design and identify whether it will work or not. This knowledge may then help researchers to create new designs.

Management researchers have been criticised for being unaware of their own epistemological position (Johnson & Duberley, 2000); however, the situation is changing. Researchers are expected to demonstrate their own ontology, and epistemology has highlighted the importance of acquiring an understanding of research philosophy. It has been argued that, by recognising these epistemological presuppositions, researchers are more likely to make a conscious choice of the research approach. The argument goes that this will make results more valid and we will learn more about the process of research itself (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001).

Johnson and Duberley (2000: p. 125) also indicate that commitment to a particular research philosophy is ‘a key feature of our pre-understandings which influence how we make things intelligible’. Thus, answering the question: ‘what is truth in market research?’ is a way to identify one’s own philosophical position.

1.3 Introduction to Each Section

The development of market research and the purpose of considering research philosophy are discussed briefly in the introduction. In the next section, a review of research philosophy reveals the current debate in terms of positivism and interpretivism. The researcher’s own paradigmatic stance is then presented along with a discussion of factors influencing this belief. The research philosophy underlying market research is presented in section three. This section aims to discuss what truth is in market research. Conclusions and implications for further research are presented in the final section.

2. The Research Philosophy Debate 2.1 Research Philosophy

243 (1) The nature of a paradigm

A paradigm is used to ‘represent people’s value judgments, norms, standards, frames of reference, perspectives, ideologies, myths, theories and approved procedures that govern their thinking and action’ (Gummesson, 2000,p. 18). It represents researchers’ perceptions of what truth is in the social world. In other words, it is the way in which they see the world and how they investigate the world (McAuley, 2005a).

The debate among different schools of philosophy can be traced back to Kuhn’s adoption of the terms, ‘paradigm’ and ‘incommensurability,’ and Burrell and Morgan’s (1979) work on sociological paradigms and organisational analysis (Lowe et al., 2005). The concept of the paradigm is fundamental to all researches (Gummesson, 2003). Lowe et al. (2005) indicate that the above works have between them stimulated a conversation in administrative and management studies.

In Kuhn’s (1962) early work, he defined a paradigm as ‘universally recognized scientific achievements that for a time provide model solutions to a community of practitioners’ (Kuhn, 1996,p. ix). Kuhn’s idea of a paradigm is ’an accepted model or pattern’ (1962,p. 23). Tadajewski (2004) indicates that the paradigm

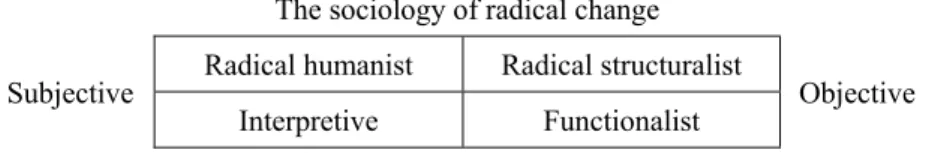

‘encompasses a theoretical structure comprised of a network of conceptual, theoretical and instrumental commitments.’ Burrell and Morgan’s (1979) conceptualisation of sociological paradigms and organisational analysis can be understood in terms of four paradigms: radical humanist, radical structuralist, interpretive and functionalist, which are based on different assumptions (fundamentally, they embody the opposition between subjectivist and objectivist conceptions) about the social world. Each paradigm has its own position and way of investigating social life, which differs from the others.

Table 1. Burrell and Morgan’s (1979) sociological paradigms and organisational analysis

Subjective

The sociology of radical change

Objective Radical humanist Radical structuralist

Interpretive Functionalist The sociology of regulation

The subject of paradigms is often discussed in terms of the opposition between two schools of philosophy: positivism and interpretivism. Both have their own way of looking at social reality and their own strategies for investigating the world; and both are valuable and valid research paradigms. The positivistic paradigm is often applied to quantitative research, and the interpretivistic paradigm is often related to qualitative research. However, even within these two broad stances there are a number of possible approaches. Silverman (1998) argues that there are no universal principles underlying all qualitative social research;

qualitative research brings up a plurality of research paradigms. However, in terms

244

of the use of sources, data collection and interpretation, a degree of overlap exists between most of these paradigms (Goulding, 1999). Both schools of philosophy are influential in business management and market research (Gummesson, 2000;

Easterby-Smith et al., 2002). However, there is debate about the respective merits of the two schools within the academic community.

Scholars use the term ‘paradigm’ in various ways, but Hunt (1994) indicates that the common interpretation among research scientists today is that a paradigm includes a knowledge content which points out a theory and its concepts; a methodology which indicates a procedure by which knowledge is to be generated;

and an epistemology which is a set of criteria for evaluating knowledge claims.

While the debate between different schools continues, academic researchers must choose a philosophical stance according to their own beliefs (Gummesson, 2000).

Tornebohm (1976 cited in Gummesson, 2000) points out that researchers can improve their research by being aware of their own research paradigm. In the next section, we will turn to discuss ontology and epistemology, to explore how researchers present the truth in terms of their belief in the social world, and how they follow a scientific methodology to find out objective knowledge.

(2) Ontology and epistemology

Research has been called the creation of truth, presented as fact or reality (Alvesson & Skoldberg, 2000). Researchers explain social facts and examine people’s subjective views of the world in the light of their own adherence to the ontological or epistemological approach. According to Alvesson and Skoldberg (2000), this is why different researchers produce different results when investigating the same research question.

Carson et al. (2001) indicate that while ontology is the study of the nature of reality, the study of epistemology essentially concerns the relationship between reality and the researcher. Easterby-Smith et al. (2002,p. 33) state that ontology is the ‘assumptions that we make about the nature of reality’ and epistemology is a

‘general set of assumptions about the best ways of inquiring into the nature of the world’. In other words, ontology is ‘a way we see the world’; epistemology is ‘a way we investigate the world’ (McAuley, 2005a). All research is based on a particular view of the world, adopts different methods and processes, and presents results which aim at ‘predicting, prescribing, understanding, constructing or explaining’ (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001,p. 13).

(3) Positivism and interpretivism

This section discusses the two opposing views of how social science research should be conducted. The two paradigms are positivism and interpretivism. In positivism, the knowledge produced by researchers is objective and contextual.

Reality is constant, independent of the individual and is the context for interactions between actors (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001). On the other hand, interpretivism posits that, although the real world cannot be accessed by individuals directly, their expression of their knowledge of the observed world is meaningful in its own right.

The real world can also be understood through appropriate interpretivist processes (Carson et al., 2001).

245 (4) Positivism

Positivists try to maintain a clear distinction between facts and value judgements. They struggle to adopt a consistently rational, verbal and logical approach in order to search for objectivity (Carson et al., 2001). They believe that

‘truth is determined through verification of predictions`. Although facts are concrete, truth cannot be accessed directly (Easterby-Smith et al., 2002). The social world is external to individual knowledge. According to Burrell and Morgan (1979), positivists maintain that reality exists as an empirical entity. Their aim is to generate a universal law that explains reality and reveals objective truth (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001).

In positivism, the world is external and objective and a single reality does exist (Easterby-Smith et al., 2002; Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001), thus, positivist epistemology is based on the assumption that only this external reality and the knowledge it generates are of significance (Easterby-Smith et al., 2002). It aims to explain causal relationships and fundamental laws through objective facts.

Positivist researchers focus on ‘description and explanation’, exploring the research topic through the discovery of external objects. Positivist researchers are independent, detached and maintain a distance from the object of the research (Carson et al., 2001).

Examining positivist research conducted into the development of organisational structures, Girod-Seville and Perret (2001) stated that, where research is guided entirely by technical and organisational reality, and not by the researchers` own views of reality, it can generate an objective picture of organisational structure. By describing these structures and reconstructing the causes of structural events, researchers hope to be able to formulate the laws which govern organisational reality.

(5) Interpretivism

The term interpretivism is derived from the Greek hermeneuein, which means

“to interpret” (Blaikie, 1993; Carson et al., 2001). This paradigm is the opposite of positivism (Bryman, 2001). According to Burrell and Morgan’s (1979) analysis, the interpretive paradigm is ‘informed by a concern to understand the world as it is, to understand the fundamental nature of the social world at the level of subjective experience` (Burrell & Morgan, 1979,p. 28). The interpretivist approach aims to understand what is happening in the context of the phenomenon under examination, in terms of the researcher’s interpretation of the data (Carson et al., 2001). In other words, it is about understanding how people make sense of the world, with human action being conceived of as purposive and meaningful (Gill & Johnson, 2002).

In interpretivism, reality is impossible to research directly. It is unknowable (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001). Interpretivists declare that reality does not exist and that the subject can never be independent of the observers. Lincoln and Guba (1985,p. 37) point out that the multiple constructed realities which exist can only be studied holistically. Reality is made up of interpretations which are constructed through the actors` interactions, motives and beliefs; thus, the knowledge gained from this process will be subjective and contextual. This has various implications for researchers (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001).

Interpretivism casts doubt on the ability of researchers to identify causal

246

relationships, because ‘all entities are in a state of mutual simultaneous shaping, so that it is impossible to distinguish causes from effects’ (Lincoln & Guba, 1985,p.

38). Interpretivists claim that the social world is being constructed and reproduced continuously (Blaikie, 1993). Thus, the process of generating new knowledge involves understanding the meaning actors give to reality (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001). Understanding is based on the concept of verstehen, developed by Max Weber (ibid). Weber‘s methodological concern was ‘with the conditions of, and limits to, establishing the validity of interpretive understanding` and was ‘directed towards the subjective states of mind of social actors and the meanings which they have used as they engage in particular social action’ (Blaikie, 1993,p. 37). This means that the researcher must first appreciate how individuals understand their world before being able to grasp and interpret the subjective meaning behind their social action (Lee, 1991).

Positivism has been applied in scientific research to explain causal relationships through objective facts. However, interpretivism is more concerned with understanding the social world. Carson et al. (2001,p. 9) point out that the key criteria differentiating the two paradigms are:

.in positivism, the researcher is independent, but in interpretivist research the researcher is involved;

.in positivism, large samples may be used whereas interpretivist research uses small numbers;

.in positivism, testing theories predominate whereas interpretivist-type research focuses on generating theories or ‘theory building’.

It is important that researchers identify their stance clearly in the research.

Girod-Seville and Perret (2001,p. 16) suggest that researchers ask themselves: ‘Can a person be his or her own object? Can a subject really observe its object without altering the nature of that object?’ It may be that a clear philosophical stance will emerge when methods and design are being selected (Burrell & Morgan, 1979).

2.2 The Writer’s Research Position

Burrell and Morgan (1979,p. 6) suggest that our choice of particular approaches and what we see and think in the research are influenced by ‘human nature’. The current writer`s preferred philosophy is interpretivism, because she believes that there is no such thing as a permanent truth; it changes moment by moment and is constructed and interpreted by people and via social consensus. This attitude towards the search for truth and meaning may well be the result of the writer’s personal experience, including the influence of Chinese philosophers, and her previous research experience.

(1) Influence of the Chinese philosophers

In primary schools in Taiwan, children are taught that ‘at the beginning of human nature is good’ (from an ancient Chinese book titled: Three-Word Proverbs).

This belief remained with the writer until she studied Chinese philosophy at university. A Chinese philosopher, Mencius, also advocated that human nature is

247

originally good (Wang, B.S., 1998). On the other hand, Xuncius took the opposite view of human nature, arguing that it is essentially bad (Wei, 1987). The writer’s faith was shaken by this philosophical dichotomy, leading her to wonder: Can human nature be absolutely good or bad? Can people really observe human nature without applying their own subjective interpretation?

An old Chinese proverb says that: when people see the mountain, it is not truly a mountain. In other words, people should not think solely in terms of objective externals, since things can be flexible and changeable on the inside.

Taoism and Buddhism also advocate this view. The Taoist concepts of ‘yin and yang’ emphasise the importance of intuitive wisdom and harmony rather than representing the world in terms of dichotomous forces (Lu, 2000). Taoist philosophy takes the view that there is no absolute truth. Buddhism embodies the traditional religion and philosophy of China. This Eastern philosophy is interested in the wisdom which results from the enlightenment of the mind and the perfection of the heart, rather than the observation of the external environment (Lan, 1997).

The writer’s curiosity about the concept of the meaning behind the objective external began with the characters of the Chinese language. Chinese characters are determined by the form of the object they represent, its sound or the meaning behind the object (Wang, 1971). The first link is easy to understand, because people can easily connect the object to the character. For example, the Chinese character:

“山” means mountain; and the word came from the shape of a mountain. The most interesting link is the last one, which relates to the meaning behind the word. Thus, our interpretation of the word is determined by our experience.

The current writer’s research stance is influenced by her contact with Chinese philosophy. Ezzy (2002,p 1) suggests that researchers should adopt ‘[t]ruths that [they] could live by with absolute confidence’. The writer believes that people have to trust their own intuition and experience, and reflect on what they see in the world;

that the truth is constructed and interpreted subjectively by individuals. Thomas indicates that people are real in their consequences if they define situations as real .

(2) Interview experience

It is inevitable that the pre-understandings or preconceptions of the researcher will influence the conduct of market research. It is the writer’s experience that, when participating in market research within arts organisations, it is often difficult for arts organisers to avoid putting their own preconceived opinions into the research. The respondents’ previous experience will influence the research. For example, when the writer investigated how arts organisations in Sheffield, UK worked with the Sheffield Telegraph newspaper, the respondents predicted from the outset that the research would identify their audience as coming predominantly from the S10 and S11 postcodes, this being a middle class area.

The power relationship is also a specific issue in management and market research (Easterby-Smith et al., 2002). This relationship may influence the choice of research topic, access to the data and whether there is much truth behind the results. Easterby-Smith et al. (2002,p. 59) indicate that ‘in the case of managerial research the boot is firmly on the other foot’. From previous experience, the writer has found that it is not always easy to access all those organisations which fall

248

within the parameters of the study, and this may make final results biased. In addition, the relationship between supervisors and students or employers and employees is crucial; some researchers may take ‘an opportunistic approach to get tenure’ (Gummesson, 2000). These factors can influence the direction of the research, the choice of paradigm and research behaviour.

According to Berg (1989), in modern organisation and management science, whether a fact or statement is accepted by, saleable to or valid for consumers is more important than whether it is true or false. Thus, for the researcher, there is no choice between absolute truth and no truth in market research – the truth is

‘historical, cultural and socially created’ (Ezzy, 2002,p. 2). A researcher’s interpretation of the historical or cultural context is derived from their wisdom or experience and will determine their pre-understanding of the research. Their understanding of the social world is guided by the socially created and interpreted by observers.

Accordingly, the writer believes that the ‘truth’ in market research is a matter of individual interpretation, and that the appropriate philosophic position is the interpetivist paradigm. The next section further explores ‘the art and science of interpretation’ (Ezzy, 2002,p. 24) in a discussion of hermeneutics.

(3) Hermeneutics and the hermeneutic circle

This section gives a broad outline of the philosophy of hermeneutics and discusses its implications for research.

Hermeneutics is defined as ‘the theory or philosophy of the interpretation of meaning’ (Bleicher, 1980:1). The major concern of hermeneutics is to consider the

‘communication [through] which we continually gain access to the world in which we live’ (Ezzy, 2002,p. 23). It posits that in the real world, object and subject are not independent (Slife and Williams, 1995). It aims to understand and interpret the meanings of the social world and evaluate how people share these meanings. It is not the business of hermeneutics to identify a single version of the truth; indeed, it posits that there is no ‘truth’ behind the objective reality – the truth is discovered in the process of interpretation. In other words, in hermeneutics there are no facts only interpretations (McAuley, 2005b), and the interpretations have to be evaluated according to their ‘coherence’ (Ashworth, 2000).

It is generally recognised that although theories are guided by data they can never entirely reflect reality. Thus, researchers are continually exploring, searching, examining, theorising and linking to internal intentions (Ezzy, 2002). Ezzy (2002) describes hermeneutic analysis as like ‘a dance’ between the interpretation of the observer and the objective which is studied, and the (to-and-fro) movement between ‘preexisting interpretive frameworks’ and ‘intentional observation’. It ends when an understanding is developed and there is no more new story to be told.

Researchers not only discover ‘the experience of the subject’, but also ‘the position of the interpreter’ (McAuley, 2004). This process will take researchers on a long journey from their pre-understanding. The hermeneutic circle is defined by Blaikie (1993,p. 47) as ‘a process of constructing the whole meaning from the available fragments and then using the evolving whole to understand the parts’. Thus, the part can only be understood from the whole, and the whole only from the parts (Alvesson & Skoldberg, 2000).

249

How can we observe the world without being influenced by preconceptions?

We must have some assumptions. Observers always start from somewhere, their pre-understanding of the social reality being influenced by their intuitive capacity or past history (McAuley, 2005b). Kearny (1999,p. 68) describes how pre-existing interpretations fit into the hermeneutic circle: ‘we are spoken to before we speak;

we are posited in tradition before we posit tradition; we are situated before we are free to criticise this situation’. Ezzy (2002) argues that pre-understanding affects everything we do in everyday life; thus, there is no reason to exclude it from the research process. Then how does the researcher’s own pre-understanding affect the research process? The researcher seeks subjects who will cooperate with the process in an attempt to build up an understanding of the world from the inside.

Collaboration is an important element of the hermeneutic circle (Ezzy, 2002). By finding subjects to participate in the study, researchers are able to interpret the meaning of the social world (Gummesson, 2003).

Hermeneutics tries to set criteria for validity, reliability and generalisability (Denzin, 1989). To make the results meaningful and presentable, researchers choose a sample which is related to their topic; at the same time, they try not to make huge generalisations. Results may be unpredictable because each researcher may place their own interpretations on the findings.

3. Research Philosophy Underlying Market Research

3.1 The Writer’s Philosophy of Market Research

The view of the writer is that the nature of reality is determined by subjective perception and is constructed socially (Girod-Seville & Perret, 2001). The interpretive stance implies that there are few truly universal scientific absolutes (Anderson, 1983). This philosophical position will influence how the researcher understands and studies market phenomena: the aim of this approach is to understand why people have particular social perspectives and experiences, rather than hypothesising external causes or generating laws to explain their behaviour and objective reality. The focus of market research is therefore to understand how people construct the different meanings they have for social reality, rather than to collect information or measure how often patterns occur in the market.

3.2 The Debate About Marketing Paradigms

Some scholars have argued that the implications of the different philosophical approaches in market research are a seriously neglected and ‘muddled’ issue (Hunt, 2003,p. 5). However, all research is influenced by how researchers see and investigate the world. Tadajewski (2004) has reviewed the philosophy behind the market research conducted over the last sixty years, including researchers’

assumptions about the nature of the world being investigated and the methodology employed. He found that educators and practitioners are increasingly being required to show knowledge of the philosophy of science, making this an important

250 issue for doctoral inquiry.

Easterby-Smith et al. (2002,p. 27) argue that ‘[a]rguments, criticisms and debates are central to the progress of philosophy’. In recent years, the rise of different paradigms in market research has resulted in big battles between those adopting different ontological and epistemological stances. Lowe et al. (2005) argue that some researchers assert that their paradigms are better than and incompatible with others. Gabriel (1999,p. 288) also points out that those researchers who claim that the positions are incommensurable are simply trying to defend their own position. The debates have become 'virtually impenetrable' (Kavanagh, 1994,p. 28) and can 'hardly be described as easy reading' (Brown, 1995,p. 683). On the other hand, Hunt (2003) claims some market researchers advocate a relativistic/constructionist stance (e.g. Peter & Olson, 1983), believing that this approach could generate functional theories in market research. Others against this notion support naturalistic, humanistic and interpretivist approaches based on the work of Lincoln and Guba, who query whether an absolute reality can be said to exist (1985). In practice, different kinds of research study require different philosophic commitments from the researcher. Only through

‘communication’ and ‘interaction’ between different sources can knowledge be generated in the domain of marketing management (Carson et al., 2001).

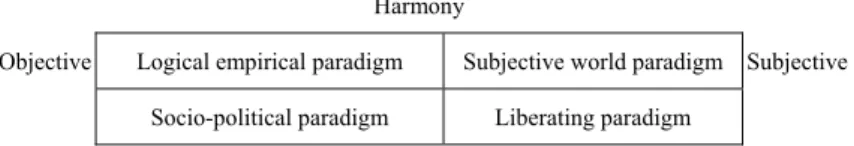

Arndt (1985) has distinguished four marketing paradigms: the liberating paradigm, the socio-political paradigm, the subjective world paradigm and the logical empirical paradigm, reflecting both subjective and objective world views (see Table 2). They recall Burrell and Morgan’s (1979) paradigms for the analysis of social theory, and provide an alternative way of conducting research in the marketing domain.

Table 2. Arndt’s (1985) marketing paradigms

Objective

Harmony

Subjective Logical empirical paradigm Subjective world paradigm

Socio-political paradigm Liberating paradigm

Conflict

(1) Truth in market research

In market research, a key issue is whether the truth is objective or subjective.

Traditionally, objective truth has been portrayed as the central goal of market research, but this has been challenged as wishful thinking by some scholars (Peter and Olson, 1983.p.122-123). Peter and Olson (1983) argue that the aim should be to arrive at a relativistic/constructionist truth; that ‘truth’ is a subjective assessment, which cannot be gathered from objective observation. In marketing science, Hunt (2003,p.222) argues, ‘we conceptualise truth not as an entity, but an attribute. It is an attribute of both beliefs and linguistic expressions’.

251

Truth is a central concept in marketing research. Morgan and Hunt suggest it can only exist where those involved trust each other’s ‘reliability’ and ‘integrity’

(1994). Zaltman and Moorman (1988) find that the key factor for managers deciding whether or not to use market research is trust. Hunt (2003,p. 248) points out that the ‘[m]ainstream philosophy of science views trust as a key construct for understanding the dynamics of scientific disciplines.’ Zaltman and Moorman (1988,p. 20) indicate that ‘being a truth teller’ is important to maintain trust.

Access to reality means ‘the ability to get close to the object of study, to really be able to find out what is happening’ (Gummesson, 2000,p. 25). This determines whether or not researchers will be able to gather the real world data to pursue a project. Another important issue is that trust can be destroyed by the misinterpretation of the results of a research project (Hunt, 2003). The problem could be caused by the researcher’s pre-understanding or by a lack of practical experience in statistical analysis. Gummesson (2000) indicates that most academic researchers’ pre-understanding comes from theories or models; they lack practical knowledge or personal business experience. For these reasons, many marketing associations and researchers pay particular attention to professional codes of ethics.

(2) Positivism and interpretivism

In recent years, marketing researchers have engaged in vigorous debates about the respective merits of positivism and interpretivism. Positivism assumes there exists a single unchanging and objective reality and that the researcher and subject must be separated in order to achieve ‘accurate, repeatable results’ (Szmigin

& Foxall, 2000,p. 191). On the other hand, interpretivists believe reality to be mental and perceptual with different perceptions and that the concern of researchers is to address a changeable and complex environment (Szmigin & Foxall, 2000,p.

190).

Szmigin and Foxall (2000) also indicate that positivists believe customer behaviour is influenced from outside; on the other hand, interpretivism assumes human behaviour comes from ‘a voluntary model’. In the positivistic tradition, the

‘stimulus-response’ and ‘stimulus-organism-response’ models are employed in most consumer research (Szmigin & Foxall, 2000). Szmigin and Foxall (2000) claim that behaviour studies need to use the same scientific methods. However, the opponents of positivism claim that consumer behaviour should be ‘distinguished from intentional action which is purposeful action mediated by meanings, deliberation on consequences, and the formation of intentions’ (O'Shaughnessy, 1985). Although positivism has traditionally been seen as ‘the sole means of theory justification’, Carson et al. (2001) claim that such a ‘polarized position’ is no longer tenable. They also argue that ‘no consensus exists as to the nature’ or applicability of a unique scientific method. O'Shaughnessy (1985) argues that most human social behaviour cannot be explained by means of a paradigm, which suggests that it may be more appropriate to use the hermeneutic approach to explain enigmatic phenomena and unscientific human beings. Applying the hermeneutic approach in the marketing context, for example, could involve observing how managers make decisions or how they interpret their role. This approach aims to gain a more ‘contextual’ understanding of phenomena (Carson et al., 2001).

252

Szmigin and Foxall (2000) have examined a range of research in marketing and found that, according to some researchers, consumer behaviour is ‘subjectively experienced in consumers’ minds’ (e.g. Hirschman & Holbrook, 1986). However, others believe that consumer experiences should be seen as a reasoned action (e.g.

Aizen & Fishbein, 1980). According to Szmigin and Foxall (2002), some researchers have a positive attitude toward both positivism and interpretivism, and advocate integrating the two approaches in order to better understand customer behaviour (e.g. Ryan, 1986). In their study of the demands of market research, Barker, Nancarrow and Spackman (2000) also found that it is impossible to get a single true picture of consumers’ attitudes or behaviour. It is inevitable that the researcher will influence the findings in both qualitative and quantitative studies.

(3) Critique of positivism

The aim of positivist research in the field of management is to generate laws to govern the operation of organisations (Johnson & Duberley, 2000). In order to make management more scientific and the environment easier to predict and control, it is necessary to identify causal relationships. Willmott (1997 cited in Johnson & Duberley, 2000,p. 40) indicates that the reality in positivist research is

‘objectively given, functionally necessary and politically neutral’. Thus, theories, whether they are accepted or rejected, are based on the truth in the objective world (Johnson & Duberley, 2000).

Johnson and Duberley (2000) point out that the major criticism of positivist management research is that this approach is so focused on identifying causal relationships and generating laws that it neglects and fails to reflect the complex situations arising in everyday work in management. Some critics claim that positivist researchers have seldom explained their epistemological stance (e.g.

Marsh, 1979). The reliability, openness to generalisation and operation of the findings generated by positivist management research have also been questioned.

Johnson and Duberley (2000) claim that positivists pay much attention to getting the objective truth, but forget that poor researchers or respondents could cause bias.

Although positivists aim to identify a probability sample for the purpose of generalisation, this sample is often drawn from a localised population only, making generalisations unreliable. The final problem in positivist research is that the observation method cannot adequately represent phenomena such as emotions, motivations or cultural influences (Johnson & Duberley, 2000).

3.3 Trends In Market Research

Marketing research is becoming increasingly important for companies facing market turbulence and challenges (Honomichl, 2000). Malhotra and Peterson (2001) identify two major reasons for the steady growth of market research as a discipline.

First, with the development of technology, companies are now able to respond to their customers more efficiently. Market research is a way for the ‘voice of the customer’ to find its way to management. Secondly, with the knowledge gained from market research, companies have a better chance of entering new and competitive markets (Kotabe & Helsen, 1998). However, the high cost and complexity of the process are encouraging many companies to try to learn how to

253

do their own market research (Malhotra & Peterson, 2001).

Malhotra and Peterson (2001) have examined the twenty-first century trends in market research and found that market researchers and managers would like to participate more both in marketing-related decision-making and market research.

Market research is increasingly being conducted on an ‘on-going’ basis, and interpretive research methodologies are becoming more widespread.

A growing interest in qualitative research

There has also been a growing interest in the qualitative approach in market research. This phenomenon is the result of increasing dissatisfaction with quantitative techniques. Hunt (1994) claims that the traditional paradigm in the marketing domain, the use of quantitative methods, is being discredited. These methods require large samples, and explaining the results can be difficult (Cepeda

& Martin, 2005). Some researchers claim that ‘positivism is discredited’ and are increasingly turning to qualitative methods as a way of knowing (Hunt, 1994).

Those researchers who are abandoning positivism are instead advocating qualitative methods and embracing philosophical concepts such as relativism, constructionism and subjectivism (Hunt, 1994). Evidence of the interpretive approach is widespread. For example, Thompson (1997) grounded his interpretive framework on the hermeneutical approach in order to identify marketing-relevant insights from consumers’ stories. In this way, it was possible to listen to consumers, identify their needs and suggest market-oriented decisions. The meaning-based research approach has also been shown to be an effective way of gathering customers` in-depth perceptions of the service environment as the first step to improving service quality (Obenour, Patterson ,& Person, 2007).

The debate between positivism and interpretivism is finally subsiding. The trend towards accepting qualitative, interpretive research to present market phenomena is growing not only among researchers but also among market practitioners (Goulding, 1999; Goulding, 2004). For example, in their study of consumer behaviour, Holbrook and Hirschman (1993) advocate the importance of interpretivist perspectives. These are increasingly seen as a way of gaining a better insight into the decision-making process and of developing theory more effectively (Goulding, 2004). Qualitative research methods are particularly effective for

‘examining and developing theories that deal with the role of meanings and interpretations’ (Ezzy, 2002,p. 3).

4. Conclusion

What is the truth? No one can claim that they own the truth, but researchers’

life experience and academic training will inevitably lead them towards their own view of what is truth and influence how they approach their research. Their beliefs in terms of ontology and epistemology will influence their research approach and it is important that they are aware of their own philosophical stance. The greater awareness of their own paradigm, the better the research that researchers can carry out. The researcher must adopt a paradigm in which he has confidence and with

254

which he is comfortable. The writer’s views are influenced by Chinese philosophers and her own past research experience. The author believes that people have to trust their own intuition and experience, and reflect on what they see in the world; that truth is constructed and interpreted subjectively by individual social actors. In other words, the writer’s philosophical position is interpetivist.

What is truth in market research? Taking into account the philosophical position outlined above and the distinctive features of market research, the view taken here is that there is no such thing as permanent truth. Although there has been debate about the relative merits of positivism and interpretivism, and traditionally positivism has occupied the central position in terms of research philosophy, there is now an increasing move towards interpretivism and the qualitative approach in market research. There are additional factors to consider, which are specific to market research: how can researchers gain sufficient access to the organisations under examination to find out what is really happening, and how can they ensure the results of the research are accepted by the decision-makers in these organisations? The power relationship in market research is one where: The power lies with the subject rather than the researchers. The key issue is not therefore whether the results are true or not, but whether the facts or statements are accepted for a larger audience. In market research, the role of the ‘truth-teller’ is to present an interpretation of social reality that will be accepted by the research subjects.

255 REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. London, UK: Prentice-Hall.

Alvesson, M., & Skoldberg, K. (2000). Reflexive Methodology: New Vitas for Qualitative Research. London, UK: SAGE.

Anderson, P. F. (1983). Marketing, scientific progress, and scientific method.

Journal of Marketing, 47(4), 18-31.

Anderson, P. F. (1986). On method in consumer research: A critical relativist perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(2), 155-173.

Arndt, J. (1985). On making marketing science more scientific: The role of observations, paradigms, metaphors and puzzle solving. Journal of Marketing, 49(3), 11–23.

Ashworth, P. (2000). Psychology and ‘Human Nature’. Sussex, UK: Psychology Press.

Barker, A., Nancarrow, C., & Spackman, N. (2000). Informed eclecticism: A research paradigm for the twenty-first century. International Journal of Market Research, 43(1), 3-28.

Berg, P.O. (1989). Postmodern management? From facts to fiction in theory and practice. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 5(3), 201-217.

Blaikie, N. (1993). Approaches to Social Enquiry. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Bleicher, J. (1980). Contemporary Hermeneutics: Hermeneutics as Method, Philosophy and Critique. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brown, S. (1995). The eunuch's tale: Reviewing reviewed. Journal of Marketing Management, 11(7), 681-706.

Brown, S. (1996). Art or science? : Fifty years of marketing debate. Journal of Marketing Management, 12, 243-267.

Bryman, A. (2001). Social Research Methods. (2nd ed.) Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. Hampshire, UK: Ashgate.

Carson, D., Gilmore, A., Perry, C., & Gronhaug, K. (2001). Qualitative Marketing Research. London, UK: SAGE.

Cepeda, G., & Martin, D. (2005). A review of case studies publishing in management decision 2003-2004: Guides and criteria for achieving quality in qualitative research, Management Decisions, 43, 851-876.

Denzin, N. K. (1989). Interpretive Biography. London: Sage.

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Lowe, A. (2002). Management Research: An Introduction (2nd ed.) London, UK: SAGE.

Ezzy, D. (2002). Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation. London, UK:

Routledge.

Gabriel, Y. (1999). Organizations in Depth: The Psychoanalysis of Organizations.

London, UK: SAGE.

Gill, J., & Johnson, P. (2002). Research Methods for Management. (3rd ed.) London,UK: SAGE.

Girod-Seville, M., & Perret, V. (2001). Epistemological foundations in Thietart, R.

256

et al. Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide. London, UK:

SAGE.

Goulding, C. (1999). Consumer research, interpretive paradigms and methodological ambiguities. European Journal of Marketing, 33(9/10), 859-873.

Goulding, C. (2004). Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: A comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research.

European Journal of Marketing, 39(3/4), 294-308.

Gummesson, E. (2000). Qualitative Methods in Management Research (2nd ed.) London, UK: SAGE.

Gummesson, E. (2003). All research is interpretive! Journal of Business &

Industrial Marketing, 18(6/7), 482-492.

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1986). Expanding the ontology and methodology of research on the consumption experience in Brinberg, D. &

Lutz, R.J. eds. Perspectives on Methodology in Consumer Research. New York, USA: Springer.

Holbrook, M. B. & Hirschman, E. (1993). The Semiotics of Consumption:

Interpreting Symbolic Behaviour in Popular Culture and Works of Art. Berlin, DE: Mouton de Gruyter.

Honomichl, J. (2000). Research revenues on the rise in '99. Marketing News, 34(13), H2, H6.

Hunt, S. D. (1994). On rethinking marketing: Our discipline, our practice, our methods. European Journal of Marketing, 28(3), 13-25.

Hunt, S. D. (2003). Controversy in Marketing Theory: For Reason, Realism, Truth, and Objectivity. London, UK: M. E. Sharpe.

Johnson, P., & Duberley, J. (2000). Understanding Management Research: An Introduction to Epistemology. London, UK: SAGE.

Kavanagh, D. (1994). Hunt versus Anderson: Round 16. European Journal of Marketing, 28(3), 26-41.

Kearny, R. (1999). Poetics of Modernity: Toward a Hermeneutic Imagination. New York, USA: Humanity Books.

Kotabe, M., & Helsen, K. (1998). Global Marketing Management. New York, USA:

Wiley.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, USA:

University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. (3rd ed.) Chicago, USA:

University of Chicago Press.

Lan, J. F. (1997). The History of Buddhism. Taipei: Dong-Da Books. (in Chinese) Lee, A. (1991). Integrating positivist and interpretive approaches to organizational

research. Organization Science, 2(4), 342-365.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. London, UK: SAGE.

Lowe, S., Carr, A. N., Thomas, A. & Watkins-Mathys, L (2005). The fourth hermeneutic in marketing theory. Marketing Theory, 5(2), 185-203.

Lu, Y. Z. (2000). The Philosophy of Taoism. Taipei: Wen-Jin Publishing. (in Chinese)

Marsh, C. (1979). Problems with surveys: method or epistemology. Sociology, 13(2), 293-305.

257

Malhotra, N. K., & Peterson, M. (2001). Marketing research in the new millennium:

Emerging issues and trends. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(4), 216-235.

McAuley, J. (2004). Hermeneutic understanding in Cassell, C. & Symon, G.

Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. London, UK: SAGE.

McAuley, J. (2005a). Background Issues in Organisation Research Methodology.

Lecture on 14 October 2005. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam University.

McAuley, J. (2005b). Hermeneutic Approaches to Organisation & Management Research. Lecture on 12 November 2005. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam University.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S.D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20-38.

Obenour, W., Patterson, M., & Person, L. (2007). Conceptualization of a meaning-based research approach for tourism service experiences. Tourism Management, 27, 34-41.

O'Shaughnessy, J. (1985). A return to reason in consumer behavior: An hermeneutical approach. Columbia University of Science, 12, 305-312.

Peter, J. P., & Olson, J. C. (1983). Is science marketing? Journal of Marketing, 47(4), 111-125.

Ryan, M. J. (1986). Implications from the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ physics for studying buyer behavior in Brinberg, D. & Lutz, R.J. eds. Perspectives on Methodology in Consumer Research. New York, USA: Springer.

Slife, B. D., & Williams, R. N. (1995). What’s Behind the Research? Discovering Hidden Assumptions in the Behavioural Sciences. London, UK: SAGE.

Silverman, D. (1998). Qualitative research: Meanings or practice? Information Systems Journal, 8(1), 3-20.

Soames, S. (1989). Understanding Truth. USA: Oxford University Press.

Szmigin, I., & Foxall, G. (2000). Interpretive consumer research: How far have we come? Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3(4), 187-197.

Tadajewski, M. (2004). The philosophy of marketing theory: Historical and future directions. The Marketing Review, 4(3), 307-340.

Thomas, W. I. (1928). The Child in America. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Thompson, C. J. (1997). Interpreting consumers: A hermeneutical framework for deriving marketing insights from the texts of consumers’ consumption stories.

Journal of Marketing Research, XXXIV, 438-455.

Wang, B. S. (1998). The Meaning of Mencius’s Philosophy. Taipei: E-Hu Publishing. (in Chinese)

Wang, Y. W. ed. (1971). Interpreting the Chinese. Taipei: Shang-Wu Publishing. (in Chinese)

Wei, Y. G. (1987). The Philosophy of Xuncius. Taipei: Gu-Feng Publishing. (in Chinese)

Willmott, H. (1997). Rethinking management and managerial work: Capitalism, control and subjectivity. Human Relations, 50(11), 1329-1359.

Zaltman, G. & Moorman, C. (1988). The importance of personal trust in the use of research. Journal of Advertising Research, 28(5), 16-24.

258

Chieh-Ching Tien is a researcher in the management of museums area. She is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of Arts, Cultural Policy and Management, in the National Taiwan University of Arts, Taiwan. She holds an MSc in Events and Facilities Management from Sheffield Hallam University, UK. Her research area mainly focuses on museum management. She has a particular interest in collaboration and relationship marketing.