國立臺東大學公共與文化事務學系南島文化研究碩士班碩士論文

Master Thesis for the Institute of Austronesian Studies at National Taitung University

The Life History of a Takasago Giyutai Survivor in Taitung, Taiwan

臺東縣高砂義勇隊一位倖存者的生命史

Chetze Lin(林哲次)

Adviser

Dr. Futuru C.L. Tsai(蔡政良 博士)

June 12, 2014

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to those professors of the Institute of Austronesian Studies, National Taitung University (school years 2011-2013) for their instruction—to Dr.

Chang-kuo Tan, to Dr. Suling Yeh, to Dr. Chihchang Keh, and to my adviser, Dr.

Futuru Tsai for his aid in offering various reading programs, focusing on the topic, analyzing the research, and editing and completing the thesis.

I wish to acknowledge with warm appreciation the assistance of the two lady officials at the Household Registration Office in Tungho Township, who helped locate my informant Alianus, but who must go unnamed here. I also wish to thank Grazia Deng of CU, HK, who helped the final stages of the revision. I also benefited from the comments, arguments and criticisms of Dr. Chih-cheng Lin, my son, while forming and consolidating ideas about the topic at the initial stage.

A special note of thanks is extended to Mincheng Chen for the technological assistance in typological arrangements of making wonderful PPT for oral presentations at the International PGSF6 at CU, HK and many others. I am grateful to Dr. Michael Huang for providing the vast and most valuable resources from Japan, and making the study extremely interesting and fruitful.

To my wife, Hsiang-chun, I am a most grateful for her gracious assistance in accompanying me to pay numerous visits to the informant in Taiyuan, taking resourceful photos for the thesis, and constantly reminding the schedule of the advancement of the thesis writing.

To all these scholars and authors I offer my sincere thanks.

摘要

本論文的目的在於透過臺東縣一位高砂義勇隊員倖存者與另一位隊員仍在世 妻子的對話,探討「高砂義勇隊員」至今仍對昔日的日本深感懷念與忠誠,甚至

目前引起原住民之間的爭論。「高砂族」,在日文字面上的意思是「台灣原住民族」。

而「義勇隊」則是「志願軍」兩者合起來就是「高砂義勇隊」,指的就是「自願 從軍的台灣原住民。」太平洋戰爭期間,台灣仍是日本的殖民地,四千兩百名高 砂義勇隊被分成七梯次派遣至太平洋各島嶼。他們為日本與盟軍做戰。大多數人 死於砲火、疾病與缺糧。據報告,只有十分之一的人生還。他們於 1945 年陸續 被遣送回台灣。回到家時,他們才發現台灣已經不再是日本所屬地了,而是由國 民黨所統治的中華民國。當他們回到家鄉時就聽到人們譴責他們是日本的走狗,

由於這些苦衷,導致他們不得不隱藏自己的身分或對打戰一事絕口不提。高砂義 勇隊的歷史被塵封六十多年,鮮為人知。

本論文的內容針對台東縣境內一位倖存者與遺族的訪談田野工作,尋求人們 常問問題的解答:他們是否全然自願獻身、離鄉到數千里外的異國為日本打戰?

為什麼?

田野工作是將被訪談者的參戰經驗,以他們「自我」的觀點口述紀錄下來,

而非「他者」的觀點。在下結論前,加入分析與詮釋。透過屢次的訪談,這些倖 存者以及遺族們的回答,千篇一律皆為否定。顯然他們還是比較喜歡日本的。戰 爭結束至今,這些僅剩十分之一的倖存者陸續過世,甚至每年繼續減少。為數不 明的倖存者仍不知身在何處。即使仍健在,也都是九十歲以上的高齡。一旦錯失 這個機會,這些寶貴的歷史資料將永遠消失,想要紀錄就更困難了。

無論他們是自願還是非自願,最終目的在於讓塵封在他們心中的記憶重現。

關鍵詞:高砂義勇隊、志願、帝國主義、太平洋戰爭、虛構的回憶

Abstract

The purpose of this investigation is to explore factors that affect the Takasago Giyutai to remain patriotic, loyal and nostalgic to the war time Japan even though there remains a contentious issue for the indigenous peoples. The term Takasago Giyutai literally means ‘an army composed of voluntary indigenous peoples.’

During the Pacific War, 1941—1945, while Taiwan was still under the colonization of Japanese Imperialism, 4200 Takasago Giyutais were dispatched to the Pacific Islands in seven rounds respectively to fight the Allied Forces alongside the Japanese army. Most of them died under the bombs, or of diseases and even of hunger. Consequently Japan lost the war and surrendered. Only one tenth of Takasago Giyutai survived and was repatriated to Taiwan at the end of the war in 1945.

Upon returning home, they were shocked by a nasty surprise to see that Taiwan was no longer under the Japanese rule. Instead, the KMT Government had taken it over after the Pacific War. Many public workers and police officers and abingo were dressed in different uniforms; the new residents around looked unfamiliar and spoke in a different language they never heard of. Out of their expectation, they were not given a hero’s welcome; instead, a cold satire. No sooner had they met people in hometown than they heard severe condemnation that they had fought alongside the enemy. As a result, they chose to reveal little or no information about the actions in the war. Thus the Takasago Giyutai’s history has long been tightly wrapped up and made blank for the past over 60 years because of the unspeakable political reasons.

The content of this paper is focused on the research in the practical fieldwork with the survivors and the families of the deceased soldiers residing in Taitung County as well as documentary works. The study proves that they joined Takasago Giyutai of their own volition and an enormous sense of honor in being one.

The fieldwork was recorded and written about the oral history of the war

experience from the viewpoints of ‘himself’ instead of ‘other’s’ point of view, intervening with analyses and interpretation.

Ever since the end of the war, many of the survived one tenth have passed away and still more are gone each year. Even if still alive, each of them, a history keeper, is surely over ninety years old, and once lost the chance, it will certainly make the research work even more difficult.

Whether it is a matter of compulsion or volunteer, our common goal is to elicit the true history that each Takasago Giyutai has kept in secret since it is clearly an integral part of the whole history.

Key words: Takasago Giyutai, Volunteer, Imperialism, The Pacific War, Imaginative Recollection

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ... i

中文摘要 ... ii

Abstract ... iii

Chapter One: Introduction ... 3

Definition ... 3

Historical Background ... 3

Research Questions ... 5

Motivation ... 5

The Purpose ... 7

Introduction to the Informants ... 9

Alianus: A second round Takasago Giyutai ... 9

Accidental Encounter ... 12

Kulian: A first round Takasago Giyutai’s wife ... 13

A great surprise ... 14

Childhood Education ... 15

Marriage ... 16

‘Triumphant’ Return... 17

Literature Review ... 21

Method ... 29

Subjects ... 29

Procedures ... 30

Chapter Two: Before the War ... 32

Initial period of Japanese Colonization ... 32

The Conflict between the Natives and the Invader ... 32

The Musha Event ... 32

Kominka Undo : All-out Assimilation Movement ... 33

The Japanization of the Taiwan Population through Assimilation ... 34

Bando Kyoiku 番童教育 ... 35

Primary Education ... 35

Kotoka 高等科 ... 36

Zettzai Fukuju 絶対服従 and Kinro Hoshi 勤労奉仕 ... 37

Seinendan 青年団 ... 38 How the Teenagers Were Prepared to Perform Their Patriotism to the

Country ... 38

Chapter Three: In the Battlefields ... 41

Why Was Takasago Giyutai Born? ... 41

Alianus’ War Experience ... 43

Kulian’s Interviews ... 53

Chapter Four: Back in Home ... 57

Home Again ... 57

Imaginative Recollections ... 65

Chapter Five: Conclusion ... 71

References ... 76

Chapter One: Introduction

Definition

The term Takasago Giyutai (高砂義勇隊) literally means “a volunteer troop composed of indigenous young men serving for the war.” Takasago zoku (高砂 族), Japanese terminology, refers particularly to the indigenous peoples of Taiwan. Zoku(族) means an ethnic tribe. Giyuta (義勇隊)means a troop composed of volunteers to serve for the war. Takasago Giyutai forms the meaning of “a volunteer troop composed of indigenous young men to serve for the war.” In this thesis Takasago Giyutai may stand for a specific individual or can be a collective noun.

The Great East-Asian War On December 12, 1941, four days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Tojo Cabinet of Japan decided to call the war against Allied Forces including Sino-Japanese War as the Great East-Asian War (大 東 亜 戦 争 ). However, after the war ended, the main center of military organization, the GHO (General Headquarters), of Allied Forces prohibited the use of the Great East-Asian War by keeping strict vigilance over all the mass media. Eventually it was replaced by the Pacific War. Since then the term the Great East-Asian War, which was actually used during the war time only, has entirely disappeared. (Sekigawa 2013)

Historical Background

This study begins with a brief history of Taiwan prior to the Pacific War until the end of the war and a little afterwards. It traces back to 1895 when Taiwan was alienated from Ching Dynasty to Japan as the result of Sino-Japanese War.

From then on Taiwan would be part of a Japanese territory for as long as 50 years. During this period of time, the Japanese led Taiwan to marvelous development in agriculture and education. In 1941, the Pacific War broke out.

Here Takasago Giyutai was pragmatically born. During the Pacific War (December, 1941—August, 1945), 4200 Takasago Giyutai were selected and dispatched to the front lines such as the Philippines and as far as New Guinea in eight rounds. They were non-combatants but engaged in labor force carrying weapons, ammunition, food supplies and the like from the seashore to the Provision Depot, and from there to wherever the units needed them. They had, no doubt, the harshest and the most unbelievably unbearable time accomplishing their role. They even took the responsibility for repairing and constructing roads, airfield runways and bridges. However, as the war got more and more intensified, they played a critically important role in guerrilla warfare.

Many of them lost their lives under the bombs, and even died of diseases and hunger. Only estimated one tenth of them survived at the end of the war.

Takasago Giyutai were repatriated to Taiwan only to find a nasty surprise that Taiwan was no longer under the Japanese control. Instead, the Chiang Kaishek‟s KMT Government took it over. The first thing they felt upset about was that the new master spoke Mandarin Chinese which they had never heard of. They had no chances or schools to learn it. What was worse, they heard condemnation that they had fought alongside the enemy Japanese against the Allied Forces. As a result, rarely did they show up and spoke out no information about the actions in the war. Therefore Takasago Giyutai‟s history has long been tightly wrapped up in their memory for the past 60 years because of the unspeakable political reasons. None of Takasago Giyutai‟s history has

Takasago Giyutai remains patriotic, loyal and nostalgic to the war time Japan so much. Today the number of Takasago Giyutai still living now has been drastically dropping and only a handful can be counted in Taitung County. They are over 90 years of age.

Research Questions

Here arise unavoidable questions: Did those enlisted as volunteers in the army prior to 1943 and after indeed volunteer or were they coerced? Did they really

“volunteer” without the slightest compulsion of the Japanese authority? Did they ever regret? Did their parents, grandparents or wives consent? Did any police officer try hard to convince them into volunteering? These are the questions people constantly ask about.

This study focuses on two questions: Did the Takasago Giyutai virtually volunteer for service on their own volition without any slightest coercion?

What are the main factors that have made Takasago Giyutai remain patriotic, loyal and nostalgic to the war time Japan so much? Besides, what happened to the family after they had been dispatched to the battlefront because they were supposed to hold responsibility for working outside and making the living for the family? What influence did they exert on the niyaro? How about the operation of age hierarchical system during their absence? So on and so forth.

Motivation

Ever since the end of the war, nearly seventy years have elapsed, during which period of time many more of the one tenth alive passed away and still the number is drastically declining each year. They joined the war at their twenties more and less and now are almost over nineties, from the peak to the bottom of

life. A doubtful number of them may be hidden in some unknown places, if still alive. Fortunately it happened more than once that I chanced to encounter a few elderly indigenous people at MacKay Hospital and Christian Hospital in Taitung. They ARE physically feeble, but when asked of Takasago Giyutai that they once were decades ago, they suddenly came to life and were willing to share their extraordinary experience with me.

Figure 1. Three Takasago Giyutai from Taitung were posed with their families who came to see them off on the departure day. None of them returned. (left). Down left

An Amis also of Taitung is with his Father and brothers before the departure day.

Down right A Bunun man wears his traditional costume with funus before the departure day. (Source: Hayashi 1998:6)

for the frontline, when I was at an early primary school age, impressed me so deeply. On that day, the whole village, young and old, gathered at the bus depot.

Each of the fresh Takasago Giyutai wearing a soldier‟s uniform with funus (Amis‟ traditional indigenous sword regarded as a man‟s second life, also a superb symbol of Takasago Giyutai) at his side, looking so brave and awesome, lifted up a white cup of wine, said cheers and bid farewell to their families, friends and the crowd. Since the Takasago Giyutai volunteered for service with their parents‟ blessing, they all appeared so excited. In return, the whole crowd of villagers yelled and roared, “BANZAI! BANZAI! GAMBARE (cheer up)!”

We began to sing military songs repeatedly, waving the sunrise national flags, and lingering and seeing them off until the bus was completely out of sight.

What their future would be like, only God knew! This past impression has long been vividly alive in my memory.

The past memory of the young Takasago Giyutai overlapped with these living elderly veterans has geared my intention to learn more about them.

Talking to them warmly, one could excavate tons of untold adventurous memories.

The Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to present the result of visiting and talking with witnesses and record as much oral history and experience as possible, and what is the most important, to explore how they thought about the life events both during the war time and after, and how they built up their national identity to dedicate their lives to “their country.” Eventually this will lead to the discussion and conclusion of whether they had truly volunteered to join the war.

People would be shocked to learn how few Takasago Giyutai hate the

war experience, how they are in favor of the Japanese instead, how they felt proud to be Japanese soldiers, and how they feel nostalgic for their young age while Taiwan was under the control of the Japanese Imperialism.

Many people can not fathom why anyone like Takasago Giyutai would have such an affectionate feeling for their teenage nostalgia in spite of the

„insignificant‟ dedication (other‟s view) of their lives in the exotic islands thousands of miles away from their homes. For whom did they volunteer to dedicate their precious youth? Did they really “volunteer” without the slightest compulsion of the Japanese authority? Did they ever regret? People today constantly ask these sorts of questions.

Takasago Giyutai returned, not only sacrificing for so little, unworthy of comparison with that the Japanese soldiers gained from their government but also being looked upon coldly by the KMT government because the fact that they had intended to dedicate their lives in order to fight for the „mother country in the past‟ turned into the result that they had fought on the enemy‟s side against the „mother country at present.‟ Who would have known that?

Many years later, the Takasago Giyutai was informed that their Japanese comrades who collaborated at the same frontline, dead or alive together, received from the Japanese government a considerable amount of money, as much as 30- 40 million Yen for compensation while Takasago Giyutai in Taiwan got hopelessly none. It is where this discrimination creates the ambivalence in Takasago Giyutai. Later a sequence of legal suits, although lost and only 30- 40 thousand dollars were allowed to the families of Takasago Giyutai, is perseveringly being proceeded. The arguments for and against the

their collective memory. Every Takasago Giyutai I spoke to has one thing in common: not a single man complained about his past history. They deem it pride and honor instead. Should this precious past of theirs not be integrated in our Taiwan‟s history?

Little attention has been given to this paradoxical phenomenon. It is, therefore, the purpose of this paper that is to investigate what factors have made Takasago Giyutai in favor of Japan so much.

Introduction to the Informants

Alianus: A second round Takasago Giyutai

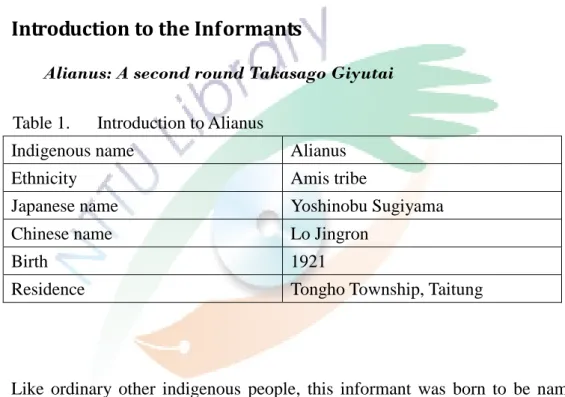

Table 1. Introduction to Alianus

Indigenous name Alianus

Ethnicity Amis tribe

Japanese name Yoshinobu Sugiyama

Chinese name Lo Jingron

Birth 1921

Residence Tongho Township, Taitung

Like ordinary other indigenous people, this informant was born to be named Alianus, an an indigenous name. Later when he volunteered to join Takasago Giyutai for the Pacific War, he was given a Japanese name (every Takasago Giyutain had one), Yoshinobu Sugiyama (杉山良信). After he returned from the battlefield at the end of the war, he was given a Chinese name, Lo Jingrong (羅景容). Three names of a person, as a matter of fact,may imply a complex history of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan. (Suenari 1983)

Alianus is a resident of Meilan, Peiyuan Village, Tongho Township,

Taitung, about 70 kilometers to the north of Taitung. It takes approximately 40 minutes‟ drive from Taitung City along Taiwan Highway 11 northward to come to a big gas station. That is the turning point to make a left turn. You will immediately come upon a century old tunnel. Through the tunnel, the road turns and twists a good deal for 6 kilometers, passing through a quiet village, and makes a sharp turn at the highest point. There are two old grocery stores contiguous to each other with a local bus stop standing just in between. From there concrete open fliers of thirty-three very steep steps lead to a spacious front yard of Alianus‟s one-story house, which looks down over a nice view, a deep valley and a winding river. The Alianus family has lived here for several decades as a pomelo and orange farmer since he was young and strong. In the rear of the house is also a big vegetable garden which is likely to be imagined that it used to produce various kinds of seasonal vegetables each year even much more than enough for the family of a dozen. But today like the aged couple, it has obviously long been deserted and left nothing but dried weeds.

All nine of his children, six of them alive, were born and brought up here, and then have mounted on the trend of lifetime migration moving northward to urban districts such as Taipei and Taoyuan and settled down there. However, they do return home for a family reunion a few times a year.

Figure 2. At his nineties, this senior veteran Alianus still stays in good shape, vivid and clear in his interview. He holds infinite war stories untold in his memories. (Photo by HC Liu.)

Alianus was born in Shoma (Xiaoma now), attended school for four years at Harapawan Kogakko (Taiyuan Elementary School now) which was the maximum years for the primary school then. Moreover, it was the time of Kominka Undo. Later through a strict military training of Seinen-dan, Youth Corps, they were offered a chance to be Japanese soldiers. Alianus together with his younger brother Hatsuo volunteered for the Second Round Takasago Giyutai, when he was 22 years old. When asked if he petitioned on his own volition, he said, “The leader, a Japanese police officer, advised, „How about taking this chance to be a soldier? It‟s a golden opportunity.‟ I agreed at once and replied the police officer confidently, „That‟s what I‟ve been expecting and that‟s what I‟m here for.‟” He laughed wildly, and continued, “I passed. Never was I so excited. My father was, too.” By that time the concept of taking a pride in having a son become a Japanese soldier was broadly accepted by the general indigenous society. This fact reveals that the once ruled were now treated as equally as the ruler. It is also clear how the young men wished to show the counterparts their prowess and bravery at the battlefront.

They were first sent to Manila in different units, and then to New Guinea via Palau. Both of them returned safe, but his brother died here at 63 years of age.

Alianus‟ wife Sra(89), Lai Showsha (頼秀霞) in Chinese name, is also an Amis woman of Tomiac tribe (Chungan now). Sra and Alianus have now six children—used to have nine but three died--three sons and as many daughters all working in Taipei, Kaohsiung, Kinmen and other places except Taiyuan. She

is said to have been an outstanding runner at school days. She kept the record of the fastest woman in Chengkoung Township area. One year, Sra took part in the 100- and 200- meter-dash at the local sports meeting and beat all other contestants even she was with six months pregnant, which fact made her well-known as the fastest woman in the village.

Accidental Encounter

My first encounter with Alianus‟s was at Taitung MacKay Hospital two years ago (2012). I happened to open the conversation in Japanese by asking him if he could speak Japanese, and how old he was. His brief answer was enough for me to decide that he was in a great spirit apart from his clumsiness because of his age. But it was immediately discovered that he was blind with utterly white pupil in the right eye. And the left eye was only extremely slightly open, but also blind. Surprisingly, he became excited when asked if he had volunteered for Takasago Giyutai. The conversation was interrupted abruptly when his wife came along and spurred for the Hospital‟s courtesy bus bound for Taiyuan.

Seeing that no time could be wasted, I briefly asked where I could see him again. I only heard, “Peiyuan Tzun,” and away the couple rushed for the courtesy bus waiting across the street.

Peiyuan Tzun, what a familiar name of a place! It is famous for producing good quality of pomelos in the early autumn each year, well associated with the moon festival. Three weeks passed. My wife and I ventured to pay a visit at Peiyuan and look for this veteran and see if I was lucky enough to meet him again.

Thanks to great help of an official of the Household Registration Office in Tonghe, I had less difficulty than expected locating the place where we found this man at home. What a surprise! Upon hearing my first greeting, he recognized my voice. His vigilance melted away instantly and he began to feel relaxed.

Figure 3. The aged couple lives in the house built by themselves.

Kulian: A first round Takasago Giyutai’s wife

Table 2. Introduction to Kulian

Tribal name Kulian Kaburugan

Ethnicity Paiwan

Japanese Name Natsuko Takada

Chinese name Kao Yuying

Husband (First round Takasago Giyutai Member)

Takurigeru (Japanese name: Sinichi Takada, Chinese Name: Kao Hsin-liang)

Birth 1925

Residence Jinfeng Township, Taitung

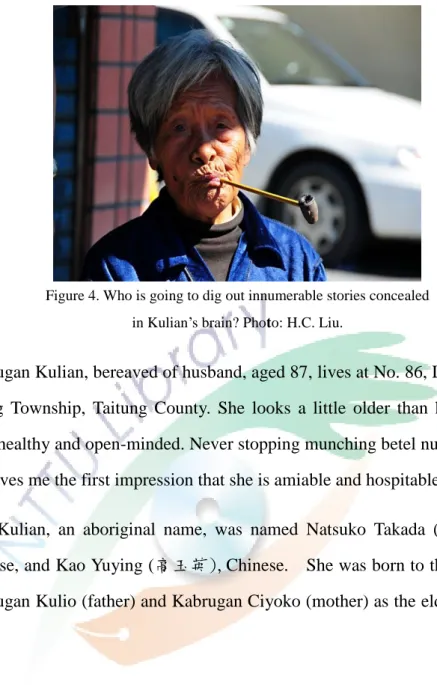

Figure 4. Who is going to dig out innumerable stories concealed in Kulian‟s brain? Photo: H.C. Liu.

Kaburugan Kulian, bereaved of husband, aged 87, lives at No. 86, Liwei Street, Jinfeng Township, Taitung County. She looks a little older than her age, but rather healthy and open-minded. Never stopping munching betel nuts, this aged lady gives me the first impression that she is amiable and hospitable.

Kulian, an aboriginal name, was named Natsuko Takada (高田夏子), Japanese, and Kao Yuying (高玉英),Chinese. She was born to the family of Kaburugan Kulio (father) and Kabrugan Ciyoko (mother) as the eldest child of seven.

A great surprise

I intended to make a short visit with a translator, but it turned out unnecessary.

At 10 o‟clock, I saw Kulian at her home. At the first glance, I was aware that she was well advanced in age, seeming in the habit of keeping herself clean and neat and healthy. She was wearing a dark purple turtle-neck sweater and black

with a stick standing within an arm‟s reach against the door. “Good day,” I tentatively started in Japanese because I knew senior tribal people over seventy generally spoke Japanese properly.

“Good, day. Welcome to my humble home. Please have a seat.” Sure enough, she spoke to me all straight in decent Japanese, remaining in her chair, and showing me to the vacant chair a little way in front of her,. Suddenly our psychological obstacles were cleared off. “Thank you very much indeed. It‟s very kind of you,” saying, I took my seat.

I was briefly introduced by his son about 40 years old in Paiwan. When I responded to her in Japanese, I immediately realized that we, she and I, could converse completely in Japanese. So our conversation started, with no translation.

Childhood Education

Kulian was born on October 20, 1925, as the oldest child in the family of Kaburugan Kulio and Kaburugan Ciyoko, living at Taryutaryun up in the mountains for 50 years, and then they were kind of forced to move down to Tsuarabi at the foot of the mountain by the Japanese police when she was just a kid of eight.

She received the Japanese elementary schooling at Kanaron Primary School from Year One through Year Four, and got No. 2 prize when graduated.

Kulian must have been a smart and hard working girl, so she was loved by her Japanese school master, Mr. Nishino, who she has still remembered so well until today. The elementary education was said to be only four years as a maximum instead of six probably because of the teacher and classroom

shortage at the early Japanese colonization period in Taiwan. However, the Japanese educational influence would last as long as her lifetime.

Since smart, active and good at singing, Kulian was appointed as team captain of Josi seinenkai, Young Women‟s Society, equivalent of local Women‟s Association today. One year she was awarded No. 1 prize of 20 Yen at Kokugo (national language) Enshukai (speech contest), which she stated with pride.

Marriage

At 16, she got married. Traditionally, her husband, the third child in his family, married to Kulian, the first child in hers. When they got married, they had five cows and some rice paddies for their own.

“My Man, Sinici Takada, was 17,” Kulian began to describe her husand.

“A Japanese police officer talked him into taking the entrance test for Taitung ex-Agricultural School. A few days after wedding, he got the notification of passing the test. He had to walk all the way from Kanarun to Taitung, which took him two days to get to the school. He stayed at the dormitory and studied for four months with everything provided by the government, as an indigenous elite under the Japanese education program. The next year my Man volunteered as Takasago Giyutai, and was sent to New Guinea until the war ended.”

When asked how she felt about her Man‟s volunteerism, she remarked slowly, “He did petition on his own like a few friends of his. A woman‟s withstanding what her man decided to do was a kind of betraying behavior, not

‘Triumphant’ Return

Finally the “Japanese” military were carried on an American warship to return to Kaohsiung Port. Once they were on shore, they were completely dismissed.

No transportation. No money. This hero had no other thought than to go home.

He had to walk all the way, day and night, to Kanarun, arriving at home after midnight. When I saw my Man appearing at the front door, I just couldn‟t believe my eyes. Both stood dumfounded for a long time. My village people and I were enormously shocked and sad when we learned four others had died on the remote island of New Guinea. My Man was the only blessed. The legendary hero had never left me and his homeland for the rest of his life.

Takurigeru, her man, was elected a representative of the township for 8 years, and died at the age of 83. During his tenure of being the township representative, it may be considered a mystery whether Takurigeru spoke in public at the meeting Paiwanese (aboriginal languages were politically discouraged at that time), Japanese (definitely prohibited), or Mandarin Chinese (if only he had willingly volunteered to learn it). There was no way of knowing it.

From anthropological point of view, it is extremely interesting to learn the informant Kulian‟s oral history, which must have been accumulated in person from her husband at random repeatedly, day by day, year by year until he passed away. I could imagine Takurigeru, the Man in the story, telling his personal saga of fighting hunger, diseases and jungle beasts as well as enemies on the Austronesian islands. It would not have been possible for me to record the personal history here unless this fieldwork had been practiced on this particular person and particular place. Presumably more numerous stories remain concealed somewhere in the brains of this aged indigenous lady. If not

dug out, the historical treasure would vanish from this earth in no time.

The attractiveness of the oral history is utterly attributed to the incidental encounter with Kulian, who knows all about it and still keep more about it in her mind so precisely and well. Anthropologists must put it the first rank to capture such ethnographic riches like Kulian‟s before the precious evidences vanish. It would depend on the skills of questioning for the researcher to elicit them thoroughly. Like Dr. Lin Poyer‟s significant studies on Chuuku Island implies that the similar wartime data are certainly concealed in many brains of senior aboriginals like Kulian in Taitung areas. How to dig them out and preserve in the history remains to be solved by the anthropologists. (Poyer 2004, 2008)

Dr. Lin Poyer (ibid.) points out that she started the fieldwork without learning a word of Chuukise but mostly depended on recording and translation.

What a great task she had done! So did Dr. Yuping Chen on Palau—she started with only 20 words when she first set her foot there. It does make sense for anthropologists to make enormous efforts to reveal more precious data right in our own county.

The two-story house is built of reinforced concrete, looks safe enough to protect from typhoons and earthquakes. Kulian regularly sits in the front veranda, easy to be seen from the narrow street. This aging lady really enjoys sitting there doing nothing except sometimes watching her grandchildren playing and chasing in the street, most of the time probably engaged in recalling the past repeatedly from time to time.

Kulian has two golden front teeth implanted when she was 14. They have

has been chewing binro betel nuts for lifelong. All through our conversation, she kept chain chewing one after another, and occasionally she takes out her self-made long pipe and smoke. The smoke leaves are self planted so they are organic, meaning free from agricultural chemicals, she said proudly.

When she was a kid, the Japanese doctor told her father that Kulian‟s stomach was particularly allergic to food of strong flavor. So she chews binro betel nut just plainly, meaning it is needless to put anything to strengthen the flavor. In her own way Kulian fully enjoys the original juicy flavor. She keeps moving her jaws so rhythmically that she keeps pace to her heart beat. This is her only way of keeping herself in shape and health, so slim and healthy except weakness in her knees which is something she could hardly do anything about.

She needs a stick to help stand and walk. This aging lady, I doubt, needs no doctor, no medicine. I just wonder if she ever touches her health insurance card which seems entirely of no use at all in the long run.

I invited Kulian to sing some Japanese children‟s songs together. We started with “Haru ga kita” Spring Has Come, and “Yuyake koyakete” The Sunset Glow. Immediately she was reminded of songs of wartime.

Wakawashi (Yokaren) no uta

Saraba Rabauruyo, Farewell Rabaul „til We Meet Again Karoranko de At the Karoran Port

She sang with perfect tune and pitch so well that you cannot but think she used to be a great singer in her youth. She made me think, “How many times had these songs come up to her lips and thought of her Man in the frontlines fighting against the enemies?” The verses are extremelly likely to make people feel so sentimental and nostalgic. I never heard or sang those songs without

feeling sympathetic with the warriors who had died at the battlefront for their country.

Kulian, while talking, is constantly soothing her hair with her left hand.

At first I neglected the action, but it kept popping back into my head. I began to feel a strange urge to comb her hair. I offered the hairbrush—lovely and handy—which I had happened to prepare as a part of gifts.

“This is for you,” I offered.

“Whas-sat?”

“A hair comb,” saying, I tore open the plastic bag, took the comb out and combed her almost 80 percent gray fumbled hair twice for her.

“Oh, arigato.” Accepting it from my hand, she began to comb herself. “Very kind of you. So comfy.”

A muffled exclamation flowed throughout her wrinkled lines on her face. A feeling of pleasure needed no translation.

“In the ancient times,” Kulian, curiously looking into the flexible comb, said, “people never used this kind of stuff.”

“Today is Sunday. Do you go to church?” I interrupted.

“No,” she replied. “Later in the afternoon, Shimpusan Catholic Father will come here and tell me stories about Yesusama Jesus.

They will also sing hymnals for me. I love „em.”

It was far past noontime. I left quite reluctantly, with a feeling that I had been with a great friend and ancient person. “I‟ve never met an indigenous

Literature Review

General accounts of the Pacific War are abundant in many books published in Japan. The fullest accounts of the Pacific War are in Hayashe Eidai‟s Testimonies--Taiwan Takasago Giyuti.(1998). It covers twelve interviews, as the result of six times of visits to Taiwan, of Takasago Giyutai from different tribes, such as Bunun, Paiwan, Amis, Atayal, etc. respectively as well as their commanders and leaders in different places in Japan who had combated together and returned alive. Most of the testimonies reveal their volunteerism, patriotism and loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. Their commanders lavish high praise and admiration on Takasago Giyutai. Here is a short excerpt: ( Hayashi 1998: 7, 43-45)

These men were gifted warriors. They had superb hearing which enabled them to tell enemy‟s approach from passing wild animals.

They could see meters ahead at the pitch dark night. Aside from this, they could move silently through the clumps of bushes in the jungle, which proved to be extremely advantageous for guerilla warfare.

They were capable of amazing feats of physical endurance.

The Testimonies is the thickest book in Takasago Giyutai’s history, and the most thought-provoking book as the evidence of the author‟s interest in the field of Takasago Giyutai‟s life history. Hayashi is unquestionably one of the pioneers in the field study of Takasago Giyutai and his firm belief in Takasago Giyutai‟s contribution is expressed in the following statement: (ibid.: 302-303)

Rarely is there anyone who could not be moved by their ultimate

sense of responsibility and spirit of fight. Whether in Munda or Wewak, their exploits erected like the Pyramids which would last forever, would be handed down generation after generation in Japan‟s history for ever and ever.

After reading many parts of the Testimonies, one may be led to wonder if it would be possible for the whole profile of Takasago Giyutai to represent the authority to have it incorporated in the history textbooks in Taiwan as well as in Japan.

There are general histories of the war partly depicting Takasago Giyutai‟s fabulous actions by Ishibashi Takashi, Kadowaki Tomohide, Tsauchibashi Kazunori, etc., stressing Takasago Giyutai‟s volunteerism in addition to various exploits.

All about the Pacific War (Taiheiyo Senso no Subete) by the Research Institute of the Pacific War, Tokyo, Japan (2012), reveals crucial battles on land and sea many of which Takasago Giyutai‟s virtual supports and daring actions were worthy of acclamation.

Churetsu Batsugun, Distinguished Loyalty (Tsuchibashi Kazunori 1976), uncovers dramatic accounts of Takasago Giyutai on diverse coasts, jungles and battlefronts.

A candid description of cannibal feast in From A’tolan to New Guinea by Futuru Tsai (2011) should be one of the rare accounts about the war. It is Ro‟eng‟s, the author‟s grandfather, true life history. Ro‟eng thought it

“unfortunate” to be selected among many to be the Fifth Round Takasago

which obviously meant death. It was not until he got to know one Amis, Haruta, from Ikegami, who also volunteered and selected to be Takasago Giyutai that his worry and fear began to vanish. Ultimately he became pleased to accept volunteerism. Ro‟eng and Haruta became good friends in the battlefield. Many a section reveals the skill of „thick description‟ (Clifford Geertz: 1973). For example, the keen observation and the gentle humor with which the small affair of cannibalism is described in a dialogue style makes From A’tolan to New Guinea one of the most delightful stories in the realm of anthropological studies.

Suzuki, Akira, Takasago-Zoku ni Sasageru, Dedicated to Takasago-Zoku , and Sato Aiko (1984), Sunion no Issho, Sunion’s Life, give details of Takasago Giyutai‟s life both at war and at home until death.

Chou Wan yao (2013), Taiwan no Rekishi, History of Taiwan (Japanese edition), shows Takasago Giyutai‟s background, volunteerism and loyalty in favor of aborigines. She touches the Takasago Giyutai‟s volunteerism under the political background paralleled by the Conscription System enacted shortly later. She reflects much sympathy by condemning the Japanese government‟s postwar cold and discriminative attitude toward Takasago Giyutai.

An opposite interpretation permeates such indigenous studies as Sun Dachuan (2005) points out that Takasago Giyutai was “coerced to concede their bodies” to Japan. Sun strongly states his conflicting opinions on how willing these young men were to leave Taiwan and go to support their colonial masters.

After the outbreak of the war, Japan required men between the age of 18 and 45 to register for military service. The nation actually drafted all men eligible into the army, not solely aborigines but Taiwanese and Japanese in

Taiwan as well as in Japan under the policy of National Mobilization (April 1, 1938). At the time they received Akagami Shoshurei ( 赤紙召集令), no reluctant actions were allowed otherwise they were to be scorned as slackers or enemy sympathizers (Tsuchibashi 1994; Hayashi 1995). For example, I know two of my teachers in the same elementary school, and a few fathers of my schoolmates, all of them Japanese, were equally called up for service in the army—there were almost no draft exemptions to any ethnic groups, that is, aborigines, Taiwanese and Japanese. Even if the volunteerism or draft was called coercion at all, it was fairly exerted nationwide, not spotlighted upon the aborigines only.

Almost all of the contents of the literature about the history of Takasago Giyutai is favorable to them in many ways. (Chou 2013:190)

In 1941, General Governor of Taiwan and Military Commander-in-Chief had the Army Volunteerism System enacted. In appreciation of the past benevolent colonial policies despite the sad conflicts, people all over Taiwan held celebration after celebration that young men were allowed to serve for the Japanese army. Instantly volunteerism caused an enormous sensation throughout Taiwan. It was amazing that many applied by submitting blood pledge to oath their passion, enthusiasm and loyalty. It is by no means easy to understand this sort of social phenomena of that time. Nevertheless, it would be considered a terrible way of thinking if it were taken for granted that the Taiwanese young males were coerced to volunteer. (Tsuchihashi 1976: 132) At the first recruitment of Army Volunteers, over 420,000 applicants swarmed up and it made the policemen in charge extremely difficult to select

When National Mobilization was enacted in 1938 (April 1), Taiwanese males thought they were fulfilling their duty as loyal subjects and later citizens of the Japanese realm. They were taught, “All Taiwanese, as loyal subjects, are equal to the Japanese.‟‟ Recruitment was voluntary and the number of applicants greatly exceeded the number required. (Miyazaki 1944)

One survivor, who joined the Third Round of Takasago Giyutai, which was said to have nearly1000 aboriginal youths, said:

“We virtually had an extremely hard time but never did we hate the Japanese. We were shouted and yelled at and beaten, but hard punishments were equally given to everybody whether you were aborigines or Japanese. I mean when it comes to the crisis of the bitterest and the most intolerable, nothing like discrimination was seen. At the very front, fighting was really hard and dangerous work; and the hard work and danger fell on everyone of us no matter you were Giyutai or not. Death under the fire came to all equally because bullets and bombs had no eyes. The harder, and the more dangerous, the more tightly we were united. At home, our life was made easier and better than our parents‟ time. So there is nothing to complain about (the Japanese colonization).”

(Suzuki, 1976; Sato, 1987).

In response to the question, “Do you think Takasago Giyutai was brave and strong?” Kamimura of Bunun said, “Strong or weak would turn out to be nothing before such fierce weapons of America. I can only say that I‟m lucky to be back alive.” (Suzuki 1976: 205)

overpraised. There are compliments given to Takasago Giyutai by Japanese commanders as follows (Hayashi 1998):

1. They all communicated in one common language—Japanese. Takasago Giyutai are composed of diverse ethnic groups, e.g. Puyuma, Paiwan, Amis, Bunun, Atyal and so on, and fatally those languages are utterly unintelligible to each other. So it is essential to have a common language to rely on. That is Japanese. Fortunately they had learned it before they became Takasago Giyutai. It surely was the most powerful thing to tie them together.

2. They had a strong sense of responsibility in accomplishing missions without fail.

3. Nothing would prevent them from finding the accurate direction and location however primitive and entangled the jungle might appear. They were able to see in the pitch dark at night, and therefore advantageous for night guerilla warfare.

4. They performed as excellent hunters when the other soldiers desperately fell in need of food.

5. Accustomed to walking barefooted by nature, they were fitted for moving in silence beyond belief. They turned out to be a most advantageous for night guerilla warfare.

6. Their tremendous physical stamina made them capable of discharging arduous duties with conspicuous ability. They were a most wonderful guys.

8. They gave top priority to honor and share adversity, never shaking it off.

9. There was not the slightest trace of selfishness or unreliability in their characteristics.

10. They feared no death, yet pursued death of glory for the “mother country.”

In addition, Takasago Giyutai left with them indelible impressions of the Japanese leaders and soldiers:

1. We had really hard time, but it fell not only upon us but upon the Japanese as well. The leaders absolutely never chose only Takasago Giyutai to head forward for danger or hardships. It is entirely true that we are of one family (people of the Emperor). Now at home our life has become much better-off than our father‟s time. So how come the hell I should say I hate Japan?

2. The Japanese and Takasago Giyutai were united tightly together until the last minute. “United, we stand. Divided, we fall.” It became our everyday motto. We now and then sang in chorus TAIWAN TAKASAGO GIYUTAI, and TAIWAN-GUN (Taiwanese Troops) in excitement with the commander among us. Everyone was greatly encouraged, cheered up and fell in ecstasy. All that was formerly taught, such as the Japanese language, and the Japanese way of life as well, paid off at the battlefield, and it has even been lasting up to present. Only the fluency in speaking Japanese may account for it.

3. When asked what his last impressive scene of the war time was, an Amis Takasago Giyutai replied, “It is my last recall that I bid farewell to my Japanese comrades when I disembarked at the Keelung Port. It was very

hard and sad to say farewell to my comrades with whom I had had the hardest times in my life.” (Ishikawa 1999)

The following are the results of participant observation and they may offer some implications for interpreting why Takasago Giyutai responds invariably in appreciation of the Japanese.

1. They discern an affectionate sense of nostalgia instead of hatred to the Japanese.

2. They have planted in them a feeling of being treated with rigid impartiality.

3. Their patriotism is based on the philosophy of life that they traditionally had a native spirit of obligation to protect their own homeland from enemies, no matter who they worked for.

4. The Takasago Giyutai is definitely keeping precious memories rarely talked.

5. The society should not isolate their collective memory. It is the anthropologists and historians that are obliged to be responsible for bridging the gap between Takasago Giyutai and the society.

6. They are now increasingly advancing in age. Once they disappear, the chance will never return forever.

The above points 4, 5 and 6 may be worth discussing from the viewpoints of history and anthropology.

Method

Subjects

More than 10 aborigines are involved in this study: Man A, Paiwan, Taxi;

Woman B, Bunun, Yenping; Couple, Paiwan, Tanyao; Woman D, Amis, Malan;

Man E, Pailang, Chishang; Woman F, Amis, Taitung Bridge; Woman G, Amis, Harapawan; Kulian, Paiwan, Kanarung; Alianus, Amis, Meilan, and others.

Except Alianus, who is Takasago Giyutai himself and still alive, a few are widows of Takasago Giyutai, the others are relatives of the ones who died at the battlefields.

All the participants are considered equivalent because they all look similar in age, over eighties, and by appearance they sure are Takasago Zoku, indigenous. You do not get chances very often. When you do, they must be seized.

Even though they speak languages utterly unintelligible to each other (I do speak a bit of Amis but none of others), they all speak Japanese appropriately about the same level. Yet they were not selected by strict randomization. Moderate factors such as age, name, the relationship with Takasago Giyutai, etc. were omitted here because all happened in an accidental encounter and not convenient to record. Here are a handful of informants who were able to provide a bit of info at the encounter.

Man A Paiwan 80+ Taxi Woman B Bunun 80+ Taniao Couple C Paiwan 85, 86 Taxi Woman D Amis 85 Malan

Man E Pairan 88 Chishang

Woman F Amis -- Taitung Great Bridge Woman G Amis 88 Harapawan

Procedures

A diagnostic set of questions was constructed to shape a figure of the Takasago Giyutai they know in mind. Like piano-trio, Quest-trio was designed. It is composed of three parts:

WHO—Do you know anybody who once was Takasago Giyutai? If yes, who?

WHERE—Where was he dispatched to?

HOW—Did he volunteer? Did his family support the thought?

If more time is permitted, each item of the Quest-trio can be continued with subquestions. For instance, WHO: What age was he when he became Takasago Giyutai? Did he return alive? How many went from his nyaro? etc.

so that the description of the target Takasago Giyutai get more and more specific and perfect. The most critical question should be the last item to get the info about his willingness to volunteer. Each of the questions was asked in random order within an ultra-short time.

The total interviewing time for each person at the hospital lobby was

leave the hospital to be taken home in the courtesy van of the hospital waiting right at the front keeping the engine running or on a wheelchair aided by an alien helper.

Couple C live in Taxi and on Mahengheng Avenue, Taitung City alternately. The husband‟s older brother was the Third Round Takasago Giyutai.

When he volunteered for service, his mother was sad but he sent letters (postcards) home three times. He died when his ship was attacked by the US planes and sunk on the way back to Taiwan. When asked if I could see the letters, he said the letters were buried with his mother when she died because they were his brother‟s only keepsakes left at home.

Alianus is the only exception that I have paid several visits with a camera, a tape recorder, a notebook, etc. and even keeping in close touch sometimes by calling. He is the main informant of this thesis.

The data gained by interviewing the casual and regular informants are put into words according to many facets of experiences, synthesis, integration and interpretation which lead to general comments.

Apart from the publications in both Chinese and Japanese as well as informants, a DVD entitled “To Unforgettable Friends—Takasago Giyutai”

(Director Hayashi Eidai, June 23, 2006) borrowed from Lifok‟s house library--provides strong verbal evidences of the war history.

Chapter Two: Before the War

Initial period of Japanese Colonization

The Conflict between the Natives and the Invader

In 1895, Taiwan was alienated from Qing Dynasty to Japan and became Japanese territory as the result of Sino-Japanese War. Most people in Taiwan were totally unaware of what was going on outside their world. Particularly in the indigenous sphere, there was no way to learn about such political and geographical warfare.

For the natives, just the Japanese showed up one day and began to take control of their land and lives. It was natural that many Taiwanese, Han and indigenous people as well, resent the invasive force and feel a sense of objection and resistance. From the new ruler‟s viewpoint, the Japanese took it for granted that all Taiwanese settlers, despite Han or indigenous people, must obey Japanese rules. The Japanese police thought they were the absolute power and authority. They wanted the ruled under their control, and expected no repellent attitudes of the natives.

On the contrary, it was more than reasonable for the natives of Taiwan to think that they suffered unjustifiable invasion of Japan. Repelling the invasion clearly meant the natives‟ exasperation and demeanor of protecting their own land at all cost of their lives and souls. (Haruyama 2008)

invasive power but in vain because of their poorly equipped arms and not organized crowds of villagers. Among the most well-known was Musha Event (by Sediq People, 霧社事件) on October 27, 1930, which is regarded as the ultimate manifestation of the indigenous outrageous exasperation. With serious toll of casualties on both sides, the Event was consequently suppressed by the Japanese military.

The indigenous people were gradually enforced by the new rulers to move down from the mountain for easier control. If any tribal chief had a move of resistance, he would be arrested, put in hand cuffs and leg chains, and brought down to walk the street. I remember the indigenous chiefs looked fierce; they had wild hair like a lion‟s head, a stout body with steel-like muscles and skin in ultra-simple clothing. He walked barefooted showing huge feet and toes and stared at people with piercing eyes which literally scared children away. The Japanese needed to gain control over these dogged chiefs to maintain order of the whole indigenous peoples. After several stubborn rebel leaders were prosecuted, resistance began to cool down.

Kominka Undo : All-out Assimilation Movement

Since the disastrous event of Musha, the Japanese government has changed its policies in much moderate ways (Haruyama 2008: 68-71). Now they began to put more emphasis on local infrastructure and indigenous people‟s education by implementing Kominka undo 皇 民 化 運 動 (1936--1940), aiming at 1) Renovation of religion, 2) National language (Japanese) movement, 3) Change of names into the Japanese style, and 4) Conscription system.

The indigenous people should learn a lesson: He who resists authority

The Japanization of the Taiwan Population through Assimilation

Inauguration of the Imperial Rescript (Mandate) of Education

In 1890, the Imperial Rescript of Education (教育勅語) was mandated in Japan.

Imperialized education took a start in schools all over Taiwan. Here is a part of the Imperial Rescript of Education cited as follows:

Our subjects ever united in loyalty and filial piety have from generation to generation illustrated the beauty thereof. This is the glory of the fundamental character of Our Empire.

Whether at highlands or on the plain, students were taught „loyalty to the Emperor and obedience to their parents.‟ Since it was regarded as dominant codes of behavior, students of elementary schools up were required to recite the Imperial Rescript of Education. It is fantastic to learn that many senior indigenous people, let alone aging Takasago Giyutai, are still able to recite it any time and anywhere today.

Due to the severe shortage of classrooms and teachers, villagers were compelled into labor service to build very simple thatched classrooms temporarily to meet the urgent use; the police officers at every police station in every village took the role of teaching. Even their wives also practically participated in the teaching job.

A retired educational inspector, Akiyoshi Suzuki, said about the “Essence

Bando Kyoiku 番童教育

On the beginning stage, those schools were called bando kyoikusho (番童教育 所) putting emphasis on the Japanese language training and acquiring Japanese ways of life such as encouragement on using chopsticks and bowls to eat meals, regular haircuts and baths, proper dressing—some girls were given Japanese kimono in person—hygiene and sanitation other than shushin (修身) Moral and Manners Education which inevitably covered such domains as honesty, filial piety, friendliness, interdependence, loyalty, and eventually patriotism.

(Watanabe 1981)

Ultimately they were trying to infuse the thought of nihon seishin (日本精 神) into every child. For instance, Alianus has always been in the habit of saying, “My teacher always stressed the never-tell-a-lie lesson to me.” Also,

“Whatever we do is for the sake of the country.” One can imagine how influential the effect of primary education has been to a child like Alianus to keep practicing lifelong.

Primary Education

The primary schooling was basically given a period of four years which was compulsory to all school age children, putting emphasis on the language acquisition and moral education. If the children could afford to continue further, they were recommended to the regular school in bigger town or city where they were enrolled in the fifth and sixth years to complete elementary school education. In general, there wee two tracks of elementary school: 1) Sho gakko 小学校 , and 2) Kou gakko 公学校. On the one hand, Sho gakko was

designed only for Japanese children. It was so well staffed and equipped that the content of teaching was exactly the same as that enjoyed by the children in Japan. On the other hand, in the other type of school, Ko gakko was for both Han and indigenous children where majority of the staff were Taiwanese teachers, except the principal and the dean, and a few Japanese teachers. The content of their texts was pretty much easier and for more daily use in comparison than that of Sho gakko, accentuating local circumstances for the Taiwanese children to acclimate.

Like Alianus, the main informant in this thesis, finishing the fourth year at Shoma Ko gakko, he transferred to Harapawan Ko gakko for the fifth and sixth years and then went on the next stage, seinen dan.

In 1941, all primary schools, kougakko and shougakkao, were unified to be called kokumin Gakko 国 民 学 校 . It was to superficially eliminate discrimination under the name of Kominka only to keep the original two parallel tracks. (Watanabe 1981)

Kotoka 高等科

The Japanese had a strict language policy to teach every Taiwanese, both children and adults. It took decades to implement. Some elite Taiwanese including Han and indigenous youths were inducted for extra two years of more intensive advanced schooling after six years of regular elementary school.

It was called kotoka (高等科) which was special and unique to Taiwan and it can be found nowhere else. Those kotoka graduates were qualified to be substitute teachers to make up for the teacher shortage, especially in rural areas.

when I was six. Nearly every evening he took me on his bicycle to nearby villages like Shouma and Pangwong where he taught Japanese to indigenous adults at yagaku night school. I still remember our bicycle had a small light powered by the bicycle‟s generator to illuminate our way back home in the darkness after the night school.

Zettzai Fukuju 絶対服従 and Kinro Hoshi 勤労奉仕

Under the Japanese colonization, three main ethnical hierarchies emerged in Taiwan‟s society. In the order of privilege, they were: 1) Japanese, 2) Han Chinese, and 3) Indigenous people. There was a strict separation between the ruling and the ruled. The Japanese police had power and authority. Kinro hoshi,

“Labor service”--without pay always—was forced to every family to construct the public infrastructure. Under such a system, “Absolute Obedience” was strictly carried out. In other words, Japanese Police expected the indigenous people, then Han and Japanese as well of free service. (Shung Ye Taiwan Indigenous People Research 1998)

As mentioned above, the Japanese tried to infuse nihon seishin or Japanese spirit into Taiwanese children. They were substantially taught: “We are citizens of the Emperor. Everybody must be loyal and patriotic to the mother country.” The National Mobilization (April 1,1938) and Kominka Undo (皇民化運動 1936--1940) were launched with the implementation of the Imperial Rescript of Education. Kominka Undo was assimilation projects of

“becoming citizens of the emperor.” Every pupil was urged to memorize the Imperial Rescript of Education by heart.

Seinendan 青年団

After Kotoka young men and women were encouraged to be members of men and women seinendan, receiving military training. Alianus was born in 1921.

Like those peers born in 1920s, Alianus was receiving seinendan military training in Taitung, Hualien and Pingtung, and they were just the fittest persons for becoming soldiers at the outbreak of the Pacific War; the chance of serving for the country had come. No wonder multitudes of young seinendan volunteered for this sacred service for the “motherland.”

Seinendan‟s motto was: Responsibility. Honor. Country. Emperor. It was there that they received a kind of education enhancing the thought of patriotism.

At the end of seinendan‟s three-month training, everybody was “encouraged”

to join the volunteer corps. By this time it was right time for them to dedicate themselves to their mother country because they were taught that they were citizens of the Emperor of Japan, and that Japan was their mother country.

Seeing that many aspects of their life had been greatly improved, they began to think that those benefits would not have been possible but for Japanese benevolence.

How the Teenagers Were Prepared to Perform Their Patriotism to the Country

Three different generations are clearly observed: 1) Adults in 1895 when Taiwan was alienated to Japan; 2) born in 1895; 3) born in 1920—30. The first group only spoke native language. The second group might pick up some Japanese and Taiwanese. They could just barely make themselves understood