Critique of the methodology of

empirical research on individual

modernity in Taiwan

Kwang-Kuo Hwang

Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Yang’s 1974 to 1991 research on individual modernity and traditionalism in Taiwan is examined and the methodology for developing measurement instruments in this program critiqued. It is proposed that the proper strategy for research on indigenous psychology is to analyze a culture at the conceptual level with the symbolic approach, and then conduct empirical research on ‘lifeworlds’ using activity theory. Yang’s research on individual modernity and traditionalism uses an inductive empirical approach without the theoretical grounding of conceptual analyses. Based on the philosophy of constructive realism, two types of knowledge (the scientific ‘microworld’ and the ‘experienced lifeworld’) are differentiated in order to explicate the significance of the discontinuity hypothesis of modernity for non-Western countries and to critique Yang’s methodology for measuring individual modernity and traditionalism. It is proposed that the research strategy of cultural psychology be used in future study. This replacement would usher in the indigenous psychology approach as is evident in Yang’s (1999, Yang, 2000) later works.

Key words: constructive realism, discontinuity hypothesis, microworld, modernity, traditionalism.

Introduction

In the 1960s and 1970s, modernization theory was popular in the Western scientific psychological community. Modernization theory entails the belief that in order to facilitate the modernization of a state or nation, it is necessary to modernize the personalities, dispositions and psychological characteristics of the individuals in that society (McClelland, 1955, 1961). Inkeles (1966) of Harvard University was the first to propose the idea of ‘the modernization of man’. He conducted a series of empirical studies to identify the distinguishing characteristics of modernized people from the perspective of psychology (Inkeles, 1969; Inkeles & Smith, 1974).

Around that same time, many psychologists also tried to develop various versions of a modernity scale for use in various non-Western societies (Dawson, 1967; Doob, 1967; Correspondence: Department of Psychology, No. 1, section 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei, Taiwan. Email:

Inkeles, 1968; Schnaiberg, 1970; Armer & Youtz, 1971; Guthrie, 1977). In Taiwan, Kuo-shu Yang was the first scholar to devote himself to the study of modernity and traditionalism from a psychological perspective. He developed the Individual Traditionality-Modernity Scale in the 1970s and completed a series of empirical studies using this scale as an instrument of measurement (Yang & Hchu, 1974; Yang, 1981, 1985; Yang, 1986).

In the 1980s, the international academic community strongly criticized modernization theory. Many sociologists began to interrogate the connection between individual and social modernization. They pointed out, for instance, that the lifestyle of urban residents in the big cities of Latin America is highly modernized and similar to that of Western countries, while their countries had not similarly progressed along the path of modernization. In fact, their politics and economics had deteriorated to a disadvantaged position in the world economic system (Frank, 1964, 1971; Dos Santos, 1970; Evans, 1974; O’Brien, 1975). As a result of the rise of world system theory (Wallerstein, 1976, 1979), the tide of research on individual modernity gradually declined in the Western scientific psychological community.

In spite of this decline, Yang has continued this line of research in Taiwan. In the late 1980s, however, he observed that, ‘After 15 years of empirical studies, I finally found that we might have made several serious mistakes in the first stage of our research’ (Yang et al., 1991, p. 245). He amended his view of the scope and content of modernity from several aspects, accordingly developed new versions of the Multiple Individual Traditionality Scale and the Multiple Individual Modernity Scale, and continued to conduct empirical research on this topic. The question remains as to whether such an amendment could truly correct the ‘serious mistakes’ recognized in the first stage. If not, what are the implications of Yang’s empirical research on traditionalism and modernity?

From the perspective of cultural change, one of the reasons for researchers from non-Western countries to study the problem of modernization is to understand whether it is possible to develop modernity from their own cultural traditions and, if so, how to go about it.

Modernism is a method of rational thinking that emerged in Western civilization after the European Renaissance in the 14th century AD. The most significant manifestations of such a way of thinking are the ‘microworlds’ of scientific knowledge constructed by human beings. A ‘scientific microworld’ consists of the particular language, way of thinking, and worldview used by scientists in a system of scientific knowledge. It is essentially different from the language and ways of thinking used by ordinary people in their own ‘lifeworlds’ of daily functioning. Many social scientists have attempted to describe the difference between these two worlds from various perspectives. Their discussions have been labeled the ‘discontinuity hypothesis’ of modernity (Hwang, 2000). Generally speaking, this hypothesis recognizes that there are some problems of modernity that are universal to all humankind, and some problems that are unique to non-Western societies. In order to identify the crucial problems for research on modernity, it is necessary to comprehend what is meant by modernity on a theoretical level, and to clarify its implications for Western and non-Western countries.

The present article consists of six parts. The first part introduces lifeworlds and microworlds, key concepts of constructive realism, a theory proposed by the Vienna School, and that is helpful in understanding the difference between the microworlds of scientific knowledge and the lifeworlds of ordinary people. Based on the discontinuity hypothesis of modernity, part two reviews the evolution of society for people living in Western and non-Western countries with respect to modernity and traditionalism. The third part discusses the methodology used in K. S. Yang’s empirical research on traditionalism and modernity, and the fourth and fifth parts critique his method for measuring them. This critique is developed

on the basis of the theoretical analyses of traditional Chinese culture and a critique of Western modernity. In the conclusion, I point out that the end of research on modernity will be the new beginning of indigenous psychology. Yang’s (2000) later work has indicated this new direction for future research.

Constructive realism

Constructive realism is a philosophy of science proposed by the Vienna School in an attempt to synthesize the previous paradigm of social science (Wallner, 1994). It divides reality into three levels. The first level is called the ‘actuality’ or ‘wirklichkeit’. It is the world, in which we humans find ourselves, and the given world that all living creatures must rely on to survive. The given world may have certain structures, or may function by its own rules. However, we have no way to recognize these structures or rules. No matter how we attempt to explain it, the world we comprehend is constructed by human beings.

According to the theory of constructive realism, the world as constructed by human beings can be divided into two categories. For the individual, a ‘lifeworld’ is a primordial world in which everything presents itself in a self-evident way. Before human beings began to develop scientific knowledge, they could only understand their experiences in daily life by making explanations, structures and responses to their lifeworlds. People living in the same culture experience common changes in their lifeworlds, and their lifeworlds are constantly sustained by a transcendental formal structure called ‘cultural heritage’. Language is the most important carrier of cultural heritage. It is also the medium through which lifeworlds are comprehended, analyzed and recorded.

For the sake of obtaining systematic knowledge on a particular aspect of the world, people construct various microworlds to satisfy the different interests of human beings, including religion, ethics, aesthetics and science. The most important interest relevant to the issue of modernity is the ‘scientific microworld’, which can be a theoretical model built on the basis of realism, or a theoretical interpretation of a social phenomenon provided by a social scientist from a particular perspective. Within any scientific microworld, the reality of the given world is replaced by a constructed reality that can be corroborated empirically.

Two types of knowledge in scientific microworld and lifeworld

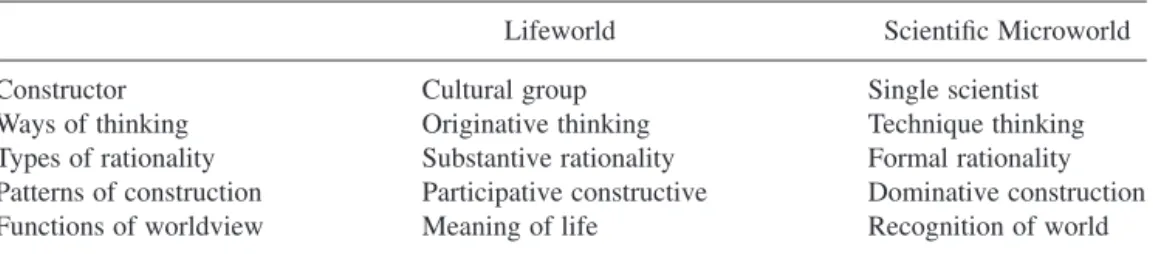

In order to highlight the dramatic difference between these two types of knowledge, I will compare them from five aspects; namely, the constructor, the way of thinking, type of rationality, pattern of construction, and the function of the worldview (Table 1).

Table 1 Two types of knowledge in lifeworld and scientific microworld Lifeworld Scientific Microworld Constructor Cultural group Single scientist Ways of thinking Originative thinking Technique thinking Types of rationality Substantive rationality Formal rationality Patterns of construction Participative constructive Dominative construction Functions of worldview Meaning of life Recognition of world

The microworld of scientific knowledge is constructed by a single scientist, while the language and knowledge used by people in their lifeworlds is constructed by a group of people living with the same cultural background for a long period of time. In any given culture, people concentrate themselves on observing the external world and contemplating the nature of objects in the lifeworld. They attempt to get rid of their own will and intention, and try their best to make every thing manifest itself in the language they create to represent it. Heidegger (1966, 1974) labeled this way of thinking ‘originative thinking or essential thinking’. In contrast, the language used by scientists to construct ‘microworlds’ of scientific knowledge is intentionally created to reach a specific goal. The language has a compulsory and aggressive character that demands the most gain with the least cost and, according to Heiderger, is a product of ‘technical thinking or metaphysical thinking’.

From the perspective of insiders living in a given society, collective consciousness and social representations are all rational (Durkheim, 1912/1965). But there is a fundamental difference between the rationality used for constructing a microworld and that used in a lifeworld. In their lifeworlds, people emphasize the importance of ‘substantive rationality’, which refers to the value of ends or results judged from a particular position. It is completely different from the ‘formal rationality’ for constructing scientific microworlds used by Western scientists after the European Renaissance (Weber, 1921/1963). Formal rationality emphasizes the importance of goals or results and provides no clear-cut means and procedures for reaching them. Only a few persons who are familiar with the special means and procedures can use them to pursue worthy goals. Substantive rationality pays attention only to value-natural facts and the calculability of means and procedures that can be used by everyone to pursue their personal goals (Brubaker, 1984).

Scientists construct their microworlds with Cartesian dualism that requires the individual to assume a position in opposition to the world in order to obtain objective knowledge through a process called ‘dominative construction’ (Shen, 1994). They construct these microworlds about various aspects of their external world that concern human beings in order to attain the goal of controlling and utilizing nature. These microworlds are neither permanent nor absolutely certain; each has its own specific goal. When the goal loses its importance, or when people are faced with new problems, scientists must construct new microworlds to address these problems. In contrast, ordinary people construct knowledge in their lifeworlds by ‘participative construction’, especially in premodern civilizations. Anthropologist Levy-Bruhl (1910/1966) indicated that the cultural systems of primitive people are constituted on the law of mystical participation, which conceptualizes human beings and nature as parts of an inseparable entity that can be viewed as a consciousness of cosmic holism (Taylor, 1871/1929).

The worldviews of the lifeworld and the scientific microworld are essentially different. As people of a given culture contemplate the nature of the universe and the situation of humankind, they gradually formulate their worldviews with original thinking in the course of their history. Walsh and Middleton (1984) indicated that a worldview thus formulated usually answers four broad categories of questions: Who am I? What is my situation of life? Why do I suffer? How do I find salvation? Generally speaking, a worldview describes not only human nature but also the relationship between an individual and the external environment, as well as the individual’s historical situation in the world. In addition, it provides a diagnosis for problems and prescribes a recipe for their solution.

The worldview in a microworld does not serve such a function. In his lexicon theory, Kuhn (1986, 1987) indicated that the scientific lexicon is composed of a set of terms with structure and content. Scientists use terms in the lexicon to make propositions in theory for

describing the nature of the world. Theory and lexicon are inseparable. The microworld of a theory cannot be understood without its specific lexicon. Different theories are understood with their various lexicons. When a theory is changed, its lexicon will change with it. Each lexicon contains a method to recognize the world. Members of the same scientific community must master the same lexicon, and share the same worldview in order to communicate with one another. In order to think about the same problem and engage in related research in the same scientific community, they must share the same worldview. However, the worldview of a microworld provides no answers to problems related to the meaning of life for ordinary people. It is essentially different from the worldview of a lifeworld.

Co-existence of modernity and traditionalism

The contrast between the two types of knowledge in a scientific ‘microworld’ and a ‘lifeworld’ enables illustration of the ‘discontinuity hypothesis’ of modernity, which is manifest especially in non-Western societies that have been evolving from their traditional cultures into modern ones.

For Western countries, most microworlds of scientific knowledge, as well as the philosophy of science for constructing the microworlds, have evolved from the interior of the civilization through a process of rationalization in every aspect of the cultural tradition. But, for non-Western countries, most scientific knowledge is transplanted from the exterior of the civilization. As a consequence, the coexistence of modernity and traditionalism has become apparent in many non-Western countries. During their process of growth, children learn traditional patterns of thinking and behaving by acquisition of language in their lifeworld (Barth, 1975, 2002; Geertz, 1983), which shapes their personality orientation with originative thinking. As they grow up and attend school, they begin to learn scientific knowledge originated from the West. Knowledge from different origins with different natures becomes mixed in their cognitive systems, and helps them to deal with problems in different situations of their lifeworlds.

When adults in non-Western countries are engaged in production work in a social system, they are likely to use knowledge from a scientific microworld as well as technical thinking with formal rationality to solve the problems encountered in their task. When they return to their intimate society and interact with family members or acquaintances, they may switch cognitive frames (Kitayama & Markus, 1999; Hong et al., 2000) and adopt some habitual patterns of activity and substantive rationality learned during earlier socialization. In particular, when individuals encounter crisis or drastic changes in life situations in which their problems cannot be solved by scientific knowledge, they are very likely to return to cultural traditions and seek solutions in their traditional worldview. This phenomenon can be termed ‘compartmentalization’ as suggested in Yang’s (1988) later works.

Methodology of K. S. Yang’s empirical research on modernity and traditionalism

Yang’s earlier empirical research on modernity and traditionalism can be assessed from the perspective of constructive realism, the discontinuity hypothesis, and world dependency theory. In this section, Yang’s basic assumptions and the specific features of his methodology are reviewed. General problems encountered in research on modernity and traditionalism are

discussed, and the instruments Yang developed to measure modernity and traditionalism critiqued with reference to the theoretical framework of this article.

Evolution of Yang’s research on modernity

After using his measurement instrument in empirical research for 15 years, Yang observed that he ‘might have made several serious mistakes at the first stage of his research’, and that ‘some of these mistakes can also be found in many studies conducted by Western researchers’ (Yang et al., 1991; p. 245). He then made significant changes to several aspects of his early conceptualization of individual modernity and traditionalism:

1 In the early stage, Yang regarded individual modernity and traditionalism as two extremities of a continuum linked together to compose a bipolar construct. Individuals higher in modernity would be lower in traditionalism, and vice versa. Later, Yang (1986, 1988) recognized that some traditional traits are preserved in modern societies. Traditionalism and modernity are neither in opposition to one another, nor are they two different stages of rectilinear development in the process of modernization.

2 Like most scholars who have studied individual modernity (Dawson, 1967; Inkeles & Smith, 1974), in his early stage, Yang considered the bipolar construct of individual modernity and traditionalism to be unidimensional, with the components constituting an individual’s modernity organized into a coherent syndrome. Yang changed his mind in later years. Now, he regards individual traditionalism and modernity as two different sets of combinations of psychological and behavioral traits composed of several dimensions (Yang et al., 1991). The extent of interrelations among those dimensions varies; sometimes there may be no relation at all.

3 In his early stage, the contents of items Yang used to measure modernity involved many domains of life. Those items were summed to give a total score representing the extent of an individual’s modernity. This method assumed that individuals have the same extent of modernity in all life domains, and that the domains are tightly related. In later years, Yang recognized that individuals may attain different degrees of modernity and traditionalism in different domains of life (Yang, 1986, 1988; Yang et al., 1991). The psychological function of compartmentalization could be an important factor for the formation of such a phenomenon. Cognitive conflict across different domains of life may cause a suffering individual to become disturbed and anxious. In order to be freed from such a state, a person might cognitively segregate the domains of life. The person may try not to simultaneously recall words and deeds from other domains of life so as to remain unaware of the potential conflict between modernity and traditionalism.

Generally speaking, the concepts of modernity and traditionalism in Yang’s second stage correspond to the discontinuity hypothesis of modernity discussed earlier. Yang (1988) called it the ‘limited convergence hypothesis’. People in non-Western societies have their own languages, ways of thinking and worldviews that have originated from their own cultural traditions. From the perspective of cultural psychology, the cultural tradition developed by any cultural group should represent the substantive rationality that the group highly values, and constitute a holistic organization that contains an integrated worldview (LeVine, 1984). The holistic organization of culture should be manifest in all domains of life, including family life, social interactions, leisure activities, the arts, politics, economy and so on. It might be true that an individual’s traditionalism is multidimensional in the psychological sense. How

can this multidimensional traditionalism that can emerge in all domains of life be understood and measured?

A similar question can be asked about the problem of modernity. After the Renaissance in the 14th century, the modernity developed by Westerners with technical thinking had the specific feature of formal rationality, which reflected the worldview of Cartesian dualism and could be represented in various microworlds of scientific knowledge. In non-Western societies, only professionals or intellectuals who had been educated in a Western-style formal educational system could master and make use of this formal rationality in their own various social systems. With the aid of modern mass media, knowledge of modernity can now penetrate non-Western people’s lifeworlds and, as a result, colonize them in the various domains of life (Habermas, 1978). However, most people in non-Western societies usually absorb only fragmentary information originating from Western culture, and so are unable to integrate it into a microworld of systematic knowledge. From a psychological perspective, the extent of an individual’s modernization under the influence of Western culture might also be multidimensional. How can the multidimensional modernity of an individual be measured?

A critique of Yang’s methodology: Experts’ experience and consensus

These questions of measurement can be answered through consideration of the research strategies of cultural psychology. Ratner (1999) suggested that there are three strategic approaches in cultural psychology: ‘symbolic’, ‘individualistic’ and ‘activity’ theory. As the individualistic approach focuses on the study of the universality of human behavior, it will not be discussed in detail in the present paper. However, the symbolic and activity theory approaches can both contribute to answering the question of how to set about studing modernity and traditionalism. The structure of a designated culture can first be analyzed using the symbolic approach to construct a microworld in a theoretical model. The theoretical model can then be used as a framework for research in the various domains of life with the activity theory approach.

In the earlier stage of the modernization study, Yang did not use the symbolic and activity theory approaches. He neither analyzed the structure of Chinese culture at a cultural level, nor explained what modernity means at a theoretical level. Instead, he followed an empirical approach and defined modernity and traditionalism on the basis of experts’ experiences and consensus. It is necessary to collect data through first-hand experience and to consult experts’ opinions in developing such an instrument of psychological measurement. Nevertheless, it is also necessary to have a sound theoretical framework to guide the direction of data collection. Any attempt to measure such broad and complicated constructs as modernity of traditionalism might be incomplete without a convincing theoretical framework. Unfortunately, in his earlier work of measuring modernity and traditionalism, K. S. Yang seems to have fallen into such a trap.

In Hchu and Yang’s (1972) earlier stage of research, a total of 212 items for the individual modernity scale were adopted from two main sources: (i) items of related questionnaires developed by foreign psychologists that were suited to Chinese people; and (ii) items designed through consideration of the social and cultural situation in Chinese society at that time. In order to ensure that each item was related to modernity, they invited 14 researchers to judge each item with respect to whether its content was valid for measuring modernity (Hchu & Yang, 1972). Yang believed that this approach ‘had taken into consideration the contents of

individual modernity for cross-cultural universality and indigenous local culture’ (Yang et al., 1991; p. 385).

After conducting research with this instrument for more than 20 years, he commented that he had been able to draw out the actual construction of modernity and traditionalism more systematically in his second stage. Yang proposed a list of 14 psychological and behavioral traits as domains of Chinese individual traditionalism and another list of 14 traits for Chinese individual modernity (Yang et al., 1991). They are listed in Table 2 side-by-side for easy comparison.

Although in his later stage, Yang and associates (Yang et al., 1991) declared that they would no longer consider individual modernity and traditionalism to be the two extremities of a continuum, most of the traits listed above can be systematically paired: universalistic/particularistic orientation, dominating-the-nature/submissive-to-nature orientation, self/other orientation, inhibited/ expressive orientation, authoritarian/ equality disposition, and independence/ dependency disposition. Each of these pairs of traits could be regarded as two extremities of a continuum. This might not have been Yang’s intention. However, this pairing of the two lists easily lends itself to construal of each pair of traits as polar ends of a dimension.

Based on these two sets of 14 traits, Yang defined eight domains for constructing items in his Individual Multiple Traditionality Scale and Individual Multiple Modernity Scale, and tried to compose meaningful items for each domain. These eight domains were: (i) family life, including the relationships between parents and children, conjugal relations, and household affairs; (ii) education and learning; (iii) profession and job; (iv) economy and consumption; (v) law and politics; (vi) religion and belief; (7) social life and leisure activity; and (vii) sex and sexual relationships. These domains were composed and chosen through discussion among a professor and three postgraduates who specialized in personality and social psychology. That is, the contents of the items for measuring individual modernity and traditionalism in Yang’s second stage were decided by expert consensus.

Table 2 Yang’s two lists of 14 psychological and behavioral traits as domains of Chinese individual traditionalism and 14 traits for Chinese individual modernity (1) Collectivistic orientation (1) Individualistic orientation

(2) Famialism orientation (2) Institutional orientation (3) Particularistic orientation (3) Universalistic orientation (4) Submissive-to-nature orientation (4) Dominating-the-nature orientation (5) Other-orientation (5) Self-orientation

(6) Relationship orientation (6) Future orientation (7) Past orientation (7) Expressive orientation

(8) Inhibited orientation (8) Achievement orientation (Activity orientation) (9) Authoritarian disposition (9) Competitive orientation

(10) Dependency disposition (10) Equality disposition (11) Homogeneity disposition (11) Independency disposition (12) Modesty disposition (12) Heterogeneity disposition (13) Self-contentment disposition (13) Tolerance disposition

(Effeminate disposition)

Yang and his colleagues collected two sets of items, and then reviewed the appropriateness of their content. After deleting items with repetitive or ambiguous meanings, 299 items were obtained for measuring traditionalism, and 256 items for modernity. A sample of 819 university students in Taiwan was used to pretest the traditionality scale, and 891 were used to test the modernity scale. Factor analysis revealed five factors on each scale. The five factors of the Multiple Traditionality Scale were:

1 Comply with Authority.

2 Filial to Parents and Worship Ancestors. 3 Self-content and Conservative.

4 Fatalism and Self-protection. 5 Male Superiority.

The five factors of the Multiple Modernity Scale were: 1 Egalitarian and Open-minded.

2 Independent and Fending for Oneself. 3 Optimistic and Aggressive.

4 Valuing Affections. 5 Sexual Equality.

It is interesting to find that, as revealed by factor analysis, most of these two sets of five factors can be paired: Comply with Authority/Egalitarian and Open-minded, Self-content and Conservative/Optimistic and Aggressive, Male Superiority/Sexual Equality. Why might these results have been obtained despite Yang’s statement that he didn’t consider traditionalism and modernity to be the two extremities of a continuum? As a technique for analyzing data, factor analysis is only as good as the quality of the data being analyzed. As mentioned before, Yang’s conceptual framework of traditionalism and modernity traits easily lends itself to being perceived as a set of polar extremities. Thus, the resulting five paired and opposing factors should be no surprise. The natural question that arises at this point is: Do these two sets of factors capture the essentials of traditionalism and modernity?

Yang’s measurement of traditionalism and its critique

In the previous section, I cited Ratner’s (1999) ‘symbolic approach’ advocating analysis of the potential influences of cultural tradition on a person’s psychology and behavior at the cultural level. Applying this approach to Chinese culture reveals that the Chinese cultural traditions of Taoism, Confucianism, Legalism and even Buddhism, which was imported into China during the East Han Dynasty, have all had an influence on Chinese social activities in daily life (Hwang, 1995). The Chinese cultural tradition is a complicated system containing numerous significant but different components. Can such a heterogeneous cultural tradition be measured with five factors? This is a question for serious consideration. Yang might cite Redfield’s (1956) distinction between ‘great tradition’ and ‘little tradition’ and point out that his intention was to investigate the little traditions practiced unconsciously by most Chinese people in their daily lives, rather than the great traditions acquired from literature by intellectuals.

Anthropologist Li (1988, 1992) defined the little traditions in Chinese culture using the symbolic approach and structuralism. His worldview model of equilibrium and my analysis of the deep structure of Confucianism will be used in this part to explore and critique Yang’s measures of traditionalism.

The worldview model of equilibrium

Anthropologist Li (1988, 1992) analyzed the folk religions, legends and myths prevailing in Chinese society and constructed a Chinese worldview model of equilibrium using the method of structuralism. The word ‘equilibrium’ used in Li’s model comes from the Confucian classic the Golden Mean, in which the term was used to mean ‘to reach balance and harmony’. Li proposed that the most fundamental operating rule in traditional Chinese cosmology is to seek balance and harmony between humans and nature, humans and society, and humans and ego. The most ideal and perfect states in traditional culture all aim at such a state of balance and harmony. In order to reach these ideal states, many complicated belief systems have been developed to maintain balance and harmony within each of the three systems, including the system of 10 celestial stems and 12 terrestrial branches (ba zi or eight characters), the theory of geomancy ( feng-shui), the theory of Chinese medicine and food, the traditional theory of naming, and the Confucian system of ethics.

Li’s worldview model of equilibrium represents the contents of substantive rationality in Chinese cultural tradition. The cosmism, concepts of person, body, disease, and ethics contained in his conceptual framework can be viewed as participative construction in Chinese culture, and can be further analyzed with the symbolic approach of cultural psychology. This type of approach is a second-degree interpretation constructed by researchers at a cultural level. It is different from the first-degree interpretation provided by people for their own actions.

Structure of Confucianism

In their critiques of previous research on individualism/collectivism that also conceptualizes culture as a continuous quantitative variable on a dimension with two polar ends, Miller (2002) proposed that psychological processes should be understood in a particular sociocultural historical context. Kitayama (2002) suggested that psychologists should adopt a system view of culture. He argued that culture is not just ‘in the head’ it is ‘out there’. Cultural meanings are typically externalized in historically accumulated public artifacts and collective patterns of behavior, including verbal and non-verbal symbols, daily practices and routines, conversational scripts, tools, and social institutions. Fiske (2002) also made a similar suggestion. I strongly agree with their arguments. It seems to me that each of the systems contained in Li’s worldview model of equilibrium can be analyzed as a microworld with the methods of social science. For instance, Hwang (1995, 2001) analyzed the deep structure of Confucianism from the perspective of social psychology by the method of structuralism. He suggested that Confucianism is composed of several distinctive components:

1 The Confucian model of mind.

2 A conception of destiny emphasizing separation of righteousness and destiny. 3 The Confucian way of humanity.

1. Ethics for ordinary people: The principle of respecting the superior and the principle of favoring the intimate.

2. Ethics for scholars: Benefit the world with the way of humanity. 4 Methods for self-cultivation.

1. Fondness for learning. 2. Vigorous practice.

3. Sensitivity to shame.

5 Jun zi (true gentleman) verses xiao ren (small-minded people).

The deep structure of Confucianism is a microworld constructed by social scientists. It is not exactly the same as the collective patterns of behavior observed in the lifeworld of a particular cultural group. Nevertheless, this type of system view of culture enables researchers to understand the findings of psychological research in terms of a theoretical framework. As Yang (1993) indicated, some components of traditional culture may change under the impact of Western culture, but some core values of a given culture may be robust and resistant to change. With such a theoretical framework, researchers may adopt a dynamic view of culture (Kitayama, 2002) that enables prediction of which parts of a traditional culture are very functional and enduring, and which parts are ready to change. For example, in an article entitled ‘Familism and development’, C. F. Yang (1988) reviewed a series of studies on the family conducted in Taiwan, Hong Kong and China. She examined four aspects of family change: the father/son axis, hierarchical power structure, mutual dependence, and dominance of family interaction. Her results indicated that although the content of Chinese familism has changed, cultural ideas about family are resistant to change. After completing higher education, younger generations are able to find jobs outside of their families and have their own income. As a consequence, parents’s power to make decisions about their children’s mate selection and money expenditure has decreased, and the father/son axis emphasizing submission to authority has weakened. In addition, the separation of residence for younger generations as they reach adulthood, has increased employment opportunities for females, and legal protection of women’s rights have all weakened the hierarchical relationship between men and women. The separation of family members’ residences may decrease the opportunity for personal interaction; however, the likelihood of interpersonal conflict is also reduced.

One of the most enduring aspects of Chinese familism is the mutual interdependence of family members. Most parents do their best to educate and take care of their children, while most children assume the obligations of filial piety, and are willing to repay and support their aging parents. When any family member encounters trouble in life, other family members are obligated to help.

Viewed from the deep structure of Confucianism outlined above, Yang’s measurement of traditionalism must be considered partial and incomplete. The contents of three factors in Yang’s traditionality scale (Submission to Authority, Filial to Parents and Worship Ancestors, and Male Superiority) can be viewed as manifestations of the principle of respecting the superior in the Confucian ethics of ordinary people, according to my analysis of the deep structure of Confucianism at the cultural level. Continued analysis with the symbolic approach reveals that Confucian ethics are basically duty based, and thus quite different from the rights-based ethics of Western individualism. Confucian ethics emphasize the importance of fulfilling one’s role obligations. They underscore the principle of respecting the superior, which reserves the power of decision-making for the person who occupies a superior position. They also emphasize the principle of favoring the intimate, which requests the decision-maker to allocate resources according to the moral principle of benevolence for the sake of maintaining the psychosocial homeostasis of both parties in the interaction.

The Confucian cultural tradition emphasizes the reciprocity of interpersonal relationships, rather than just requesting the inferior to follow the principle of respecting the superior. Therefore, Yang’s measure on traditionalism by emphasizing the principle of respecting the superior only is incomplete for us to understand the traditional arrangement of interpersonal relationships.

The principle of respecting the superior and its partiality

The following are some items for measuring the Submission to Authority factor.

T 76. The chief of government is like the head of a family. All important officers of the state should obey his decision.

T 91. The best way to avoid making the wrong decision is to obey a senior’s words. Some of the items Yang used to measure the Filial to Parents and Worship Ancestors factor were:

T 87. The maximum offense made by children is not fulfilling filial devotion to their parents.

T 103. Tasks that parents assign should be carried out right away without any hesitation. Some of the items used for measuring the Male Superiority factor were:

T 6. When a husband and wife have different opinions, the wife should obey her husband. T 112. The man is the leader of the family. The husband should make all major decisions in the family.

In Chinese cultural tradition, items such as these are all manifestations of the principle of respecting the superior. That is, Yang did capture the values entailed by the principle of respecting the superior in his research. However, he measured these factors without consideration of the cultural context. Specifically, he measured Male Superiority without considering the responsibility that men must take for women, Filial to Parents and Worship Ancestors without considering the obligations that the parental generation must assume for the younger generation, and Submission to Authority without considering that the person in authority should assume all responsibility and obligation. Traditionalism measured without consideration of the cultural context can only be partial and not complete.

Conservative or studious?

From the perspectives of Li’s worldview model for achieving the state of equilibrium, and my analysis of the Chinese cultural tradition, Yang’s two additional factors (Self-content and Conservative, and Fatalism and Self-protection) as measured by the Multiple Traditionality Scale are somewhat confusing. For example, in the 1980s, social scientists all over the world were attracted by the empirical facts of the East Asian economic miracle. Many scholars argued that the Confucian tradition emphasizing the value of studiousness and hard work were the most important cultural factors for economic development in East Asian countries (Jones & Sakong, 1980; Hofheinz & Calder, 1982; Hicks & Redding, 1983). Yang’s Self-content and Conservative factor contains some items related to attitudes towards learning and working:

T 53. Seeking higher education is useless. It is enough for one to know how to read and to write.

T 93. Blame and physical punishment are the best way to discipline children.

T 98. People would rather make less money working for relatives, rather than more money working for strangers.

T 38. Rewards for work should consider seniority first, and personal ability second. Do these items measure the traditional attitudes of studiousness and hard work in Chinese culture? If the answer to this question is ‘yes’, how could East Asian countries have developed

the labor intensive and export-oriented manufacturing industry in the 1980s with this kind of traditionalism?

Dynamic fatalism

Some of the items with high loadings on the Fatalism and Self-protection factor are quite ambiguous. For example:

T1 100. It is very hard to find a job now. People won’t get a job if they don’t have the proper background or relationship.

T1 48. When a person has power but makes less money, we can say that he doesn’t know how to take advantage of a good opportunity.

T1 97. No matter whether a poor person does his best, it is impossible for him to be elected as the people’s representative.

T1 59. Poor people’s children are still poor; wealthy people’s children are still wealthy. Why would agreement with these items indicate that a person has the traditional orientation of Fatalism and Self-protection? These items basically describe some facts of a society. A traditional society may have these phenomena, but a modern society may have them too. What links agreement with these items to traditionalism?

In Yang’s Multiple Traditionality Scale, among those items that have high loadings on the Fatalism and Self-protection factor, there are only three items related to a person’s view of destiny:

T 68. Wealthy or poor, success or failure, gain or loss, all are destined. T 88. Success or failure of a business is mostly determined by fortune.

T 5. People’s whole lives are arranged by destiny. One should not worry about it. These three items all measure a sort of fatalism. But, do they reflect the traditional concepts of destiny popular in Chinese culture? The answer to this question is worthy of careful consideration. Alhough Confucians acknowledged that supernatural powers might have some influence on a person’s future, they did not think that it was possible for human beings to understand such supernatural powers as ghosts or a god. They rejected discussion of the supernatural and assumed an attitude of respecting supernatural powers without inquiring into those issues (Lau, 1968). People with a moral conscience should try their best to practice their virtuous duty. This attitude is exemplified by the following Confucian sayings: ‘Do your best and leave everything else to Heaven’, ‘Man plots, Heaven determines’, ‘Do your best with reference to your fortune’.

Li (1992) indicated that, according to the traditional Chinese conceptions of destiny, fortune can be modified by various means. Seeking a harmonious state with temporality was expressed by this convertible fortune. When traditional Chinese are engaged in important affairs in life, they will usually consult a fortune-teller to assess the most appropriate time to conduct the matter. This behavior is called ‘choosing fine days and good time’.

The traditional Chinese belief in geomancy ( feng shui) also contains ideas of controlling nature and manipulating spatial factors. In traditional Chinese society, it is generally believed that there are five factors that may exert some influence on one’s destiny, namely, fate, fortune, geomancy, doing charitable deeds, and reading books. Except for the first, the other four factors can be modified by one’s will and effort. Lee (1993) termed this kind of attitude ‘dynamic fatalism’. In other words, this kind of Chinese fatalism may work in either a positive or a negative way. It is up to the individual how and on what occasion to use it.

Yang’s measurement of modernity and its critique

Yang’s Multiple Modernity Scale includes five factors in total. Among them, the meaning of the fifth factor, Optimistic and Aggressive, is most difficult to comprehend. A sample of items with high loadings on this factor includes:

M1 12. The progress of science and technology brings bright prospects for human beings. M2 18. The economy can get prosperous only under a trade system with free competition. M2 123. Rich entrepreneurs deserve their wealth because it is the fruit of their hard work. M2 282. Most of the social problems we have now will certainly gradually be resolved in the future.

M2 117. Most people are honest and reliable; they will not plot against others.

Why would an individual who agrees with these items necessarily have a high degree of modernity? As these items were empirically derived, one might argue that those who are modern are more likely to agree with these items. But, is it true that a person living in a modern society would agree with these items?

We cannot answer these questions by continuing with an empirical approach. Instead, analysis with reference to a theoretical framework is necessary to answer not only these questions, but also such questions as: What is modernity? What kind of situation will it bring to human beings? In the next section, I will discuss its relationship with rationality and the consequence of its degeneration from classical rationality to instrumental rationality.

Modernity and its critique

Degeneration of rationality

From the analyses reviewed in the present article, it is clear that modernity is actually a consequence of the rationality emerging from European civilization after the Renaissance in the 14th century that became substantially manifest in various microworlds of scientific knowledge. When people consistently use scientific knowledge to do production work, this kind of rationality is very likely to degenerate qualitatively into instrumental rationality. In the conclusion of his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber (1930) pessimistically predicted the fate of industrial capitalism:

To-day the spirit of religious asceticism – whether finally, who knows? – has escaped from the cage . . . The rosy blush of its laughing heir, the Enlightenment, seems also to be irretrievably fading, and the idea of duty in one’s calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs . . . The individual generally abandons the attempt to justify it at all . . . The pursuit of wealth, stripped of its religious and ethical meaning, tends to become associated with purely mundane passions, which often actually give it the character of sport . . . Of the last stage of this cultural development, it might well be truly said: ‘Specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.’ (Weber, 1930/1992, p. 182).

Philosopher Husserl (1936/1970) solemnly criticized the rationality that has predominated the progress of Europe civilization. In his work The Crisis of European Sciences and the Transcendental Phenomenology, he pointed out that the most significant feature of the modern European spirit is the belief that through the power of rationality, human beings can acquire the liberty of autonomy, improve their own lives and assume the mission to create their own history.

However, Husserl indicated that natural science and classical rationality are essentially two different kinds of knowledge. Classical rationalists strive for the truth of the universe, whereas natural scientists work towards knowing how the natural world operates. They believe that the occurrence of natural phenomena can be predicted or controlled, providing that the universal laws for the operation of nature are found. Such rationality in natural science is actually a biased instrumental rationality. It lacks the spirit of classical rationality that is essential for learning and finding pure theory, and excludes values, asthetics, ethics and meanings of life. It is impossible to use this type of blind knowledge with no reasonable purpose to guide people to develop a rational life. This is origin of the crisis of European civilization. Both Max Weber and Husserl devoted themselves to studying the influence of modernization on the future of human beings. In consideration of their pessimistic attitudes towards the capitalistic system and natural science, how can it be argued that modern people will agree with statements such as, ‘The economy can become prosperous only under a trade system with free competition’, or ‘The progress of science and technology brings bright prospects for humanity’?

The character of calculation

What might be the influence of instrumental rationality over the individual’s mentality? As early as the beginning of the 20th century, sociologist Simmel (1900/1978) discussed this issue in his book The Philosophy of Money. He indicated that the most representative emblem for instrumental rationality in modern society is money. Money can be regarded as a kind of pure instrument. It can be used to attain any goal or intention without restriction, although it is essentially irrelevant to any goal of human beings. Money is originally a means for achieving various ends. As a consequence of economic development, it has been transformed into an absolute end for human actions. Simmel indicated that modern mentalities have become increasingly calculating. The precondition of calculation is the quantification of everything. The disposition to change quality into quantity in life can be completed with the aid of money (Simmel, 1900/1978, p. 278). The operation of a money economy makes modern humans busy all day long with counting, appraising, weighing, altering and simplifying the value of quality into quantity, and making decisions on the basis of numerical values. With this point in mind, it is difficult to understand why ‘Most people are honest and reliable; they will not plot against others’ is an item for measuring modernity.

‘Instrumental rationality’ causes the character of calculation to become the most significant psychological function of modern people. A modern person will emphasize realities and take a matter-of-fact attitude as far as possible when interacting with others. They respond according to their brains, not their hearts (Simmel, 1900/1978, p. 410). In contemporary cities, the anonymity of supply-and-demand relationships maintained by market exchange enables interpersonal relationships to divest themselves of personal considerations or affections. After rational calculation, two parties can interact on the basis of economic egoism without worrying about the aberration caused by unpredictable factors external to their relationship. In view of the egoistic character of modern people, it is hard to believe that a modern participant with self-consciousness tends to endorse the statements: ‘Most of the social problems we have now will certainly gradually be resolved in the future’, or ‘Rich entrepreneurs deserve their wealth because it is the fruit of their hard work.’

Distinguishing rights from power

Bearing in mind the calculating orientation of modern people, it is not difficult to see the partiality and incompleteness of Yang’s Multiple Individual Modernity Scale. The Egalitarian and Open-minded and the Sexual Equality factors in this scale are both used to measure a subject’s attitude towards equal rights and opportunity for various situations in an open society. The major difference between these two factors lies in the fact that the contents of the latter concentrate on relationships between members of the opposite sex. Items with high loadings on the Egalitarian and Open-minded factor include:

M 56. If the leader of government makes mistakes in public, people have the right to criticize him.

M 21. Students should have the right to argue with teachers over their faults. M 122. In order to supervise the government, we need powerful opposition parties. M 127. A political reformer or propagandist should have the right to give a speech in public.

M 68. Children are supposed to argue against their parents if they consider their own opinions are reasonable.

In comparison, items measuring Sexual Equality include

M 20. It is not a problem if the chief executives of the government are female.

M 31. A wife is supposed to have her own independence. She needn’t be amenable to every word her husband says.

M 2. Men and women should have equal opportunity to be well educated.

M 137. For most occupations, women have the ability to serve in the same positions as men.

Most people would agree that modern people would insist on the ideal of equal rights. Assessing an individual’s modernity by that person’s attitude towards Egalitarianism and Open-mindedness or Sexual Equality is acceptable. However, rights are not equal to power. In modern societies, everyone has the same right or opportunity, but this doesn’t mean that everyone has the same power. In any social interaction, each person will be situated in a position of either superiority or subordination, depending on the quantity and quality of social resources held. The party in a superior position holding many social resources might control or manipulate the inferior one. Simmel (1950) termed this phenomenon ‘domination’. Domination is normal in any social relationship. It can be found not only in traditional societies, but also in modern societies. Of course, there are remarkable differences between the two: In a traditional society, interpersonal relationships are arranged according to a role system of ascribed status, and interpersonal domination is often constrained by primordial or social roles. Interpersonal relationships in a modern society are determined by one’s achieved status, and an individual may enjoy more freedom to choose the role to play without so much constraint. However, inferiors who don’t hold social resources are still likely to be dominated by powerful superiors. Taking this point into consideration, it would be incomplete to measure modernity by considering only the Egalitarian and Open-minded and Sexual Equality factors, while ignoring the pursuit of power and the phenomenon of power domination in modern society.

Individualistic self-assertion or valuing affections

Similar problems arise with the factor Be Independent and Fend for Oneself and the Valuing Affections factor. Most of the items included in these two factors measure an orientation of

individualistic self-assertion, with the contents of the latter concentrating on the arrangement of interpersonal relationships between members of the opposite sex. For example, some representative items for measuring the Valuing Affections factor include:

M 34. A couple that cohabitates without legal marriage should not be disparaged. M 22. As long as a couple love each other, they may get married without considering whether one spouse has had sexual relationships with others.

M 23. A high school student having a girl- or boyfriend is nothing evil, they should not be stopped.

M 18. As long as a couple love each other, it would be all right to have sex without legal marriage.

M 54. If a couple loves each other, they can get married even if the wife is older. From the contents of these items, it can be seen that items of the Valuing Affections factor are actually measuring a sort of Eros Orientation, which is an individualistic self-assertion in the arrangement of relationships with the opposite sex. It is acceptable to use the factor to measure the psychological disposition of modernity. However, it is inappropriate to name it ‘Valuing Affections’. We should not forget the other aspect of modernity in assessing the tendency of individualistic self-assertion.

Within the domain of interpersonal relationships with the opposite sex, modern people may confront a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, persons in modern society have more freedom to choose sexual partners. On the other, this kind of freedom may engage them in conflict between eros and sex. Rollo May (1969; ch. 3), an existentialist psychoanalyst, differentiated two types of heterosexual love in the Western tradition. The first is lust or libido, which is aimed at obtaining satisfaction from sexual intercourse. The second is Eros, which is the drive for love that makes people have the desire for propagation and creation. Since the end of World War I, people in the West have changed from a state of pretending that sex does not exist, into a new state of being wholeheartedly captivated by it. In the contemporary Western societies, people are comfortable being naked in sexual contact, but they are afraid of disclosing their minds, which should be accompanied with interpersonal warmth and gentleness. The passion towards the sex partner is weakened so as to almost disappear. May (1969) indicated unequivocally that this kind of divided personality is actually a natural consequence of instrumentalization in interpersonal relationships. It makes people avoid intimate relationships, unable to touch or even understand them.

Modern people may have more freedom to choose a sexual partner. But, this freedom of individualistic self-assertion can only be called Lust or Eros Orientation at most. The term Valuing Affection cannot be appropriately used to describe this kind of interpersonal attitudes

The dark side of modernity

Yang holds a very optimistic attitude towards modernity. This optimism towards modern society is reflected in the Optimistic and Aggressive factor in his Plural Modernity Scale. However, modernity has its dark sides: For example, Marcuse (1964), a leading figure of the Frankfurt School, pointed out that the advanced industrial society is a new totalitarian society. The major factor contributing to its totalitarianism is not terror and violence, but technical advancement. The advancement of technology enables modern society to penetrate into people’s leisure time, and to occupy people’s minds through the television and other mass media. It makes people feel satisfied with their rich material lives here and now, and leaves no motivation to pursue freedom or to imagine another way of life. In sum, because of the advancement of instrumental rationality, although modern society is not a free society, it is

a comfortable society. It is a centralized society that exerts effective control over the individual, and yet it is a society that makes its people feel satisfied.

The modern society criticized by Marcuse is an advanced industrial society. Asian countries mostly import their technology and equipment for industrial production from foreign countries. Although they may be able to claim that they have already reached the status of a modern society by many objective indicators, it is very hard for them to claim to be an advanced industrial society. Is it difficult for members of Asian societies to be aware that their destinies are still controlled or dominated by other advanced industrial societies? It is not clear why modern people should score high on the Optimistic and Aggressive factor.

Conclusion

The modernization of non-Western countries is a very complicated phenomenon that can be understood from many different perspectives. This article adopts the perspective of constructive realism, which emphasizes the distinction of the two types of knowledge in the scientific microworld and the lifeworld, and highlights the discontinuity hypothesis of modernity. It represents a particular perspective formulated by the author after two decades of reflection and research on this topic. But, the possibility of alternative interpretations of this issue should not be excluded. A more appropriate solution to this issue may be possible. This article has discussed the constraints of Yang’s empirical research on individual traditionalism and modernity. In the second stage of his research, Yang proclaimed that he no longer considered traditionalism and modernity to be the two extremes of a continuum and proposed such important ideas as the limited convergence hypothesis and compartmentalization (Yang, 1988). However, when he constructed his measurement instrument, the instrument still appeared to be dimensional extremities. In constructing his Individual Traditionalism Scale, he paid attention to the social inferior’s or subordinate’s obligation to follow the principle of respecting the superior, but neglected to consider the responsibility superiors must assume in order to gain their position. In constructing his Individual Modernity Scale, Yang paid attention to the individualistic self-assertion of modern people and emphasized the equality of rights, but he did not thoroughly consider that the equality of rights does not mean every person has equal power in a modern society. Under the domination of ‘instrumental rationality’, the powerless are destined to become puppets that can be easily controlled or manipulated by capitalists and politicians.

I must admit that my critique of Yang’s research on modernity and traditionalism has the benefit of hindsight, which is not entirely fair to Yang. Further, Yang is not the only researcher to embrace such an optimistic attitude towards modernity. With the May Fourth Movement of 1919 many Chinese intellectuals took this standpoint. They advocated a New Culture Movement, which took the position that Western democracy and science are two foreign ‘Buddhas’ that can save China. These intellectuals believed that modern civilization originating from the West stood in sharp contrast to traditional Chinese culture. In fact, they thought that these two cultural systems were located at the two extremes of a construct and were incompatible with one another (Lin, 1979). Working under such an intellectual tradition and zeitgeist, Yang might have been influenced by the ideas of earlier Chinese scholars who advocated modernization, as were many of his contemporaries. This influence was in all likelihood reflected in his earlier empirical research on modernity and traditionalism.

Yang has devoted himself to the progress of indigenous psychology for more than 10 years. As a student of Yang and a participant in the Indigenization of Social Science

Movement, I propose that in order to develop indigenous psychology in Taiwan, it is necessary to recognize the limitations of the modernization approach. The only way to promote scientific research in searching for reality is to continue rational communication from the perspective of wider rationality. As far as research on modernity and traditionalism is concerned, if the ‘discontinuity hypothesis’ of modernity is acceptable, it is necessary to treat modernity and traditionalism as two completely different cultural systems, and to investigate their content and structure separately with the ‘symbolic approach’ as suggested by cultural psychologists. For example, if researchers want to study the traditionalism of Chinese culture, they must first examine the traditional concepts of destiny, geomancy, body, diseases, ethics, soul etc. These concepts can be used to construct a conceptual framework for conducting empirical research in daily life using the ‘activity theory’ approach. In the same way, in order to conduct research on modernity, researchers must first analyze related concepts at the theoretical level. Paradoxically, this task is also the main goal of indigenous psychology. A phoenix must be burned in fire to gain rebirth. Yang’s advocating of indigenous psychology might be the logical result of his years of research with the modernization approach. As a consequence of Yang’s advocacy, the scientific community of psychology in Taiwan is experiencing a paradigm shift from modernization research to the indigenous approach, while strong debates about the ontology, epistemology and methodology of the new trend are still reoccurring within the Taiwanese camp of indigenous psychology (Hwang, 2002). Can he accomplish his goal through indigenous psychology as he has defined it (Yang, 1999, 2000)? These questions await Yang’s answer and the efforts of all scholars in search of a psychology of the Asian people.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written while the author was supported by a grant from Ministry of Education, Republic of China, 89-H-FA01-2-4-2. The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr Olwen Bedford for her constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

References

Armer, M. & Youtz, R. (1971). Formal education and individual modernity in an African society.

American Journal of Sociology, 71, 604–626.

Barth, F. (1975). Ritual and Knowledge Among the Baktaman of New Guinea. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Barth, F. (2002). An anthropology of knowledge. Current Anthropology, 43, 1–18.

Brubaker. R. (1984). The Limits of Rationality: An Essay on the Social and Moral Thought of Max

Weber. George Allen & Unwin, London.

Dawson, J. L. M. (1967). Traditional versus Western attitudes in West Africa: The construction, validation, and application of a measuring device. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,

6, 81–96.

Doob, L. W. (1967). Scales for assessing psychological modernization in Africa. Public Opinion

Quarterly, 31, 414–421.

Dos Santos, T. (1970). The structure of dependence. American Economic Review, 60, 231–236. Durkheim, E. (1912/1965). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Free Press, New York.

Evans, P. (1974). The military, the multinationals and the ‘Miracle’: The political economy of the ‘Brazilian Model’ of development. Studies in Comparative International Development, 9, 26–45.

Fiske, A. P. (2002). Using Individualism and Collectivism to Compare Cultures: A Critique of the Validity and Measurement of the Constructs. Psychological Bulletin, Vol, 128, no. 1, 78–88. Frank, A. G. (1964). The growth and decline of import substitution. Economic Bulletin for Latin

America, 9(1), March.

Frank, A. G. (1971). The Sociology of Development and the Underdevelopment of Sociology. Pluto Press, London.

Geertz, C. (1983). Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. Basic Books, New York.

Guthrie, G. M. (1977). A social-psychological analysis of modernization in the Philippines. Journal of

Cross-Cultural Psychology, 8, 177–206.

Habermas, J. (1978). Theory of Communicative Action. Vo1. II, Lifeworld and System: A Critique of

Functionalist Reason. Beacon Press, Boston.

Hchu, H. Y. & Yang, K. S. (1972). The relationship between the degree of modernity and psychological needs of Chinese university students. In: Y. Y. Lin & K. S. Yang, eds. Personality of Chinese People, pp. 393–422. Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Taipei (in Chinese). Heidegger, M. (1966). Discourse on Thinking. Harper & Row, New York.

Heidegger, M. (1974). The Principle of Ground. In. T. Hoeller, ed. Man and World, Vol. II, pp. 207–222. M. Nijhoff, The Hague.

Hicks, G. L. & Redding, S. G. (1983). The story of the East Asian Economic Miracle: Part One: Economic theory be damned!. Euro-Asia Business Review, 2, 24–32.

Hofheinz, R. & Calder, K. E. (1982). The Eastasia Edge. Basic Books, New York.

Hong, Y. Y., Morris, M. W. & Chiu, C. Y. (2000). Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologist, 55, 709–720.

Husserl, E. (1936/1970). The Crisis of European Sciences and the Transcendental Phenomenology [Trans. by D. Carr]. Northwestern University Press, Evanston, IL.

Hwang, K. K. (1995). Knowledge and Action: A Social-Psychological Interpretation of Chinese

Cultural Tradition. Sin-Li, Taipei (in Chinese).

Hwang, K. K. (2000). The discontinuity hypothesis of modernity and constructive realism: The philosophical basis of indigenous psychology. Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences, 19, 1–32 (in Chinese).

Hwang, K. K. (2001). The deep structure of Confucianism: A social psychological approach. Asian

Philosophy, 11, 179–204.

Hwang, K. K. (2002). Emergence of Indigenous Psychology in Taiwan; Paper presented at the International Congress of Applied Psychology, 7–12 July, Singapore.

Inkeles, A. (1966). The modernization of man. In: M. Weiner, ed. Modernization: The Dynamics of

Growth, pp. 151–163. Basic Books, New York.

Inkeles, A. (1968). The Measurement of Modernism: A Study of Values in Brazil and Mexico. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Inkeles, A. (1969). Making man modern: On the causes and consequences of individual change in six developing countries. American Journal of Sociology, 75, 208–225.

Inkeles, A. & Smith, D. H. (1974). Becoming Modern. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Jones, L. P. & Sakong, I. (1980). Government, Business and Entrepreneurship in Economic

Development: The Korean Case, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Kitayama, S. (2002). Culture and Basic Psychological Processes: Toward a System View of Culture.

Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 128, no. 1, 89–96.

Kitayama, S. & Markus, H. (1999). Yin and Yang of the Japanese self: the cultural psychology of personality coherence. In: D. Cervone & Y. Shoda, eds. The Coherence of Personality. Social

Cognitive Bases of Personality Consistency, Variability, and Organization, pp. 242–302. Guilford,

New York.

Kuhn, T. (1986). Possible worlds in the history of science. In: S. Allen, ed. Possible Worlds in

Humanities, Arts and Sciences, pp. 9–32. Proceedings of Nobel Symposium, 65. W. de Gruyter,

Kuhn, T. (1987). What are scientific revolutions? In: L. Kruger, L. J. Datson & M. Heidelberger, eds.

The Probabilistic Revolution, pp. 7–22. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Lau, S. G. (1968). The History of Chinese Philosophy, vol. 1. Chung-Chi College, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (in Chinese).

Lee, P. L. (1993). Modernization and Dynamic Fatalism in Chinese Culture. Paper presented at the IVth Symposium on Modernization and Chinese Culture; 11–18 October 1993. The Chinese University of Hong Kong & Beijing University, Hong Kong and Su-Zhou (in Chinese).

LeVine, R. A. (1984). Properties of culture: An ethnographic view. In: R. A. Shweder & R. A. LeVine, eds. Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self and Emotion, pp. 67–87. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Levy-Bruhl, L. (1910/1966). How Natives Think [Trans. by L. A. Clare]. Washington Square Press, New York.

Li, Y. Y. (1988). Ancestor worship and the psychological stability of family members in Taiwan. In: K. Yoshimatsu & W. S. Tseng, eds. Asian Family Mental Health, pp. 26–33. Psychiatric Research Institute of Tokyo, Tokyo.

Li, Y. Y. (1992). In search of equilibrium and harmony: On the basic value orientation of traditional Chinese peasants. In: C. Nakane & C. Chiao, eds. Home Bound: Studies in East Asian Society, pp. 127–148. The Center for East Asian Cultural Studies, Hong Kong.

Lin, Y. S. (1979). The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Anti-Traditionalism in the May Fourth

Era. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

McClelland, D. C. (1955). Some social consequences of achievement motivation. In: M. R. Jones, ed.

Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, pp. 41–65. University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The Achieving Society. Free Press, New York.

Marcuse, H. (1964). One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Beacon Press, Boston.

May, R. (1969). Love and Will. Norton, New York.

Miller, J. G. (2002). Bringing Culture to Basic Psychological Theory: Beyond Individualism and Collectivism. Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 128, no. 1, 97–109.

O’Brien, P. J. (1975). A critique of Latin American theories of dependency. In: Oxaal, I, Bartnett, T. & Booth, D., eds. Beyond the Sociology of Development, pp. 7–27. Routledge Kegan Paul, London. Ratner C. (1999). Three approaches to cultural psychology: A critique. Cultural Dynamics, 11, 7–

31.

Redfield, R. (1956). Peasant Society and Culture. University of Chicago Press, Phoenix Books, Chicago.

Schnaiberg, A. (1970). Measuring modernism: Theoretical and empirical explorations. Americal

Journal of Sociology, 76, 399–425.

Shen, V. (1994). Confucianism, Taoism and Constructive Realism. WUV-Universitäsverlag, Bruck. Simmel, G. (1900/1978). The Philosophy of Money [Trans. by T. Bottomore and D. Frisby]. Routledge

& Kegan Paul, Boston.

Simmel, G. (1950). The Sociology of Georg Simmel [Trans., edited and with an introd. by K. H. Wolff ]. Free Press, Glencoe, IL.

Taylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive Culture, 5th edition: 1929 printing. Harper and Torch Books, London. Wallerstein, I. (1976). A world system perspective on the social sciences. British Journal of Sociology,

27, 243–352.

Wallerstein, I. (1979). The Capitalist World-Economy. Cambridge University Press, New York. Wallner, F. (1994). Constructive Realism: Aspects of New Epistemological Movement. W. Braumuller,

Vienna.

Walsh, B. J. & Middleton, J. R. (1984). The Transforming Vision: Shaping a Christian World View. Inter-Varsity Press, Downers Grove, IL.

Weber, M. (1921/1963). The Sociology of Religion. Beacon Press, Boston.

Weber, M. (1930/1992). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism [Trans. by T. Parsons, introd. by A. Giddens]. Routledge, London.