©2010 Taipei Medical University

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

Background: Following the curriculum reforms of 2002 that emphasized humanistic values and ethics in medical education and instituted liberal arts requirements, medical students are expected to acquire a new conception of professionalism that incorporates the social contract inherent to the profession.

Purpose: This paper presents the results of a 2007 survey of medical students concerning their ideals.

Methods: The survey instrument was designed based on codes of conduct for good doc-toring; it encompassed five dimensions deemed essential to professionalism. The quality of the instrument was assured via consultation with experts as well as with reliability and validity tests. The data were collected from 440 out of 860 first- to fourth-year undergradu-ate medical students at four medical schools between April and June 2007 in Taiwan. Statistical analysis utilized LISREL 8.72 to check construct validity. Further ANOVA tested the significance of differences among groups.

Results: The 440 responding medical students expressed a high valuation for all dimen-sions of medical professionalism; however, they placed relatively greater importance on medical knowledge and skills, interpersonal skills, and teamwork. First- and second-year students had a slightly higher valuation for all dimensions compared to fourth-year students. This may be due to curriculum reforms not being fully in effect when the older students began study.

Conclusion: Taiwan’s humanistic medical educational reforms are only in the nascent stages, and subsequent longitudinal studies are recommended. The slight gap between general universities and medical universities may reflect a greater range of liberal arts courses in general universities that enhance a student’s basic understanding of humani-ties. Nonetheless, liberal arts courses are now listed as requirements for undergraduate medical students. Received: Sep 13, 2009 Revised: Oct 9, 2009 Accepted: Oct 9, 2009 KEY WORDS: code of conduct; medical professionalism; medical students; survey

A Professionalism Survey of Medical

Students in Taiwan

Chiung-Hsuan Chiu

1,2, Hsin-Yi Lu

3, Linda Gail Arrigo

2,

Chung-Jen Wei

4, Duujian Tsai

2*

1Department of Health Care Administration, School of Public Health and Nutrition, Taipei Medical University,

Taipei, Taiwan

2Graduate Institute of Humanity in Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan 3College of Hakka Studies, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

4Department of Public Health, College of Medicine, Fu-Jen Catholic University, Hsinchuang, Taiwan

*Corresponding author. Graduate Institute of Humanity in Medicine, Taipei Medical University, 250 Wu-Hsing Street, Taipei 110, Taiwan. E-mail: djtsai@tmu.edu.tw

1. Introduction

In recent years, concerns over the challenges to profes-sionalism among physicians in developed countries have triggered curricular reforms in medical educa-tion.1–3 The main concern is that with the rise in cost-management by insurers, physicians are losing both autonomy and personal responsibility to their patients. Medical schools worldwide have held substantive discussions regarding pedagogy and curriculum de-sign in order to create academic environments that in-still professionalism. Professional behavior and related personal attributes are now listed as core learning ob-jectives in medical education. Different measuring tools have been devised to better assess the progress of a student’s professional attitude.4

In Taiwanese society, physicians have been held in high esteem as leaders. This practice dates back to Japanese colonialism (1895–1945) when locals were encouraged and educated in modern Western medi-cine for the sake of public health. Public trust in phy-sicians and close personal relationships between doctors and patients constituted the foundations of the social contract in folk society.5–7 Since personal re-lationships with physicians in small local clinics have largely been subsumed by large hospitals after the im-plementation of the National Health Insurance policy in 1995, public perception of the medical profession has been eroding. This event is conjunctly related to the increasing complexity of biomedical technology, marketization of medical care, and domination of health care management with cost concerns. Moreover, similar to what many scholars have observed in devel-oped countries, it is generally remarked that young Taiwanese physicians, affluent and privileged com-pared to the previous generations, do not display the personal commitment assumed by past medical pro-fessionals.8–10 Criticisms expressed by the United States National Committee on Foreign Medical Education and Accreditation in 199811 were the trigger that spurred Taiwan’s medical schools to initiate curricular reform in 2002, specifically prescribing humanistic and liberal arts education for entering medical students compara-ble to that required in the United States.

The goals of the medical education reform were to enhance humanistic concerns in medical education. The strategies most schools adopted included replac-ing entrance examinations with various kinds of appli-cant interviews, and establishing liberal education requirements for the pre-med curriculum. Several years have passed since reform, making possible an evalua-tion of the ideals that have been imbued in the medical students post-reform.

One matter to be addressed is the different selection of liberal education courses in general universities and medical universities. While Rosovsky indicated that stu-dents in college should achieve a breadth of general

education during the first year and be allowed to pur-sue their own academic interests in the second, liberal education should be separate from occupational train-ing.12 While teaching programs and resources of medi-cal schools are somewhat different, the goal is to clarify differences in educational effect on students. We se-lected samples from four medical schools, two from general universities, and the others from dedicated medical universities.13

2. Methods

This paper analyzes the outcome of Taiwan’s medical education reforms with respect to student ideals of professionalism. We used a cross-sectional attitude sur-vey to evaluate the development of professional atti-tudes and behaviors of medical school students from the first to the fourth year. An all-inclusive code of con-duct was utilized to assess student judgments as to how physicians should interact with patients, their coworkers, and the overall community.

2.1. Instrument

Most existing instruments that measure profession-alism tend to focus on specific attributes of a profes-sional, or one aspect of competence, but neither on a comprehensive construct14 nor interactions with im-portant stakeholders.15 In contrast, we define profes-sionalism in the context of a social contract between medicine and society3,4,15 in a rather more compre-hensive manner. Our instrument was devised from the codes of conduct across specialties and countries, in-corporating an important declaration that covers a wide array of good doctoring practices. We began by collecting the codes of conduct from associations in the United Kingdom, the USA, Japan and Taiwan, and from the World Medical Association and the Dec-laration of Lisbon on the Rights of the Patient 1981.16–36 We adapted three foundations for medical profession-alism (clinical competence, communication skills, and ethical and legal understanding) from Arnold and Stern,1 the professionalism standard of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education,37 and the competency measure of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination.38

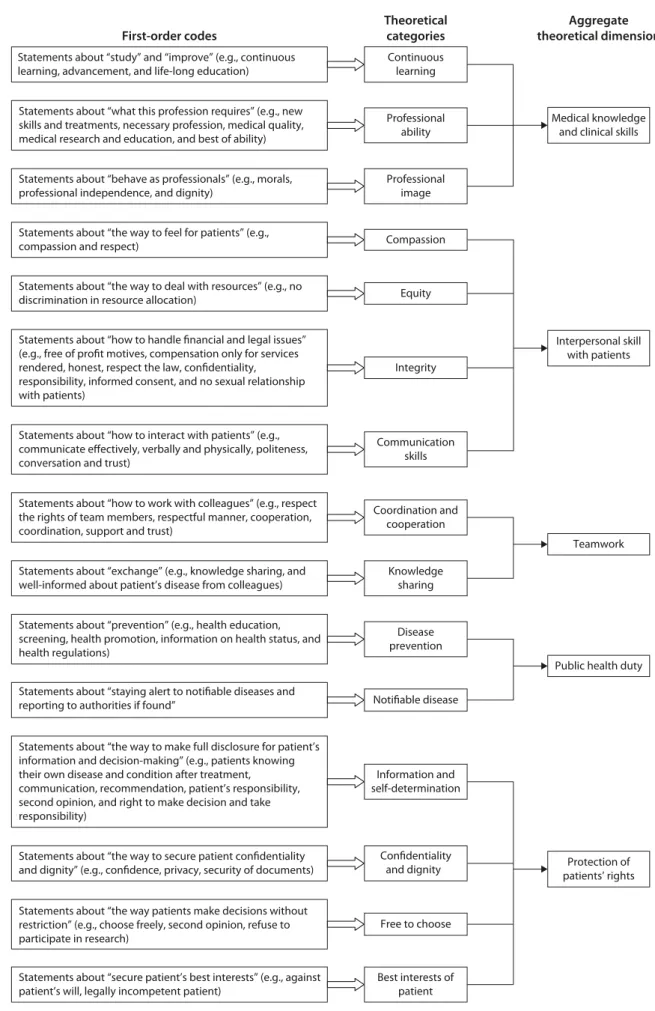

The authors formed theoretical categories and then determined five aggregate theoretical dimensions, in-cluding “medical knowledge and clinical skills”, “inter-personal skill with patients”, “teamwork”, “public health duty”, and “the protection of patients’ rights” (Figure 1). The dimension of “public health duty” was added to the survey due to public concern regarding medicine’s social responsibility in the aftermath of the major SARS outbreak in Taiwan in 2003, when some medical per-sonnel were accused of abandoning their stations.39

First-order codes

Theoretical categories

Aggregate theoretical dimension

Statements about “staying alert to notifiable diseases and reporting to authorities if found”

Statements about “prevention” (e.g., health education, screening, health promotion, information on health status, and health regulations)

Notifiable disease Disease prevention Statements about “exchange” (e.g., knowledge sharing, and

well-informed about patient’s disease from colleagues) Statements about “how to work with colleagues” (e.g., respect the rights of team members, respectful manner, cooperation, coordination, support and trust)

Knowledge sharing Coordination and

cooperation Statements about “how to interact with patients” (e.g.,

communicate effectively, verbally and physically, politeness, conversation and trust)

Statements about “how to handle financial and legal issues” (e.g., free of profit motives, compensation only for services rendered, honest, respect the law, confidentiality, responsibility, informed consent, and no sexual relationship with patients)

Statements about “the way to deal with resources” (e.g., no discrimination in resource allocation)

Statements about “the way to feel for patients” (e.g., compassion and respect)

Communication skills Integrity

Equity Compassion Statements about “behave as professionals” (e.g., morals,

professional independence, and dignity)

Statements about “what this profession requires” (e.g., new skills and treatments, necessary profession, medical quality, medical research and education, and best of ability) Statements about “study” and “improve” (e.g., continuous learning, advancement, and life-long education)

Professional image Professional ability Continuous learning

Statements about “secure patient’s best interests” (e.g., against patient’s will, legally incompetent patient)

Statements about “the way patients make decisions without restriction” (e.g., choose freely, second opinion, refuse to participate in research)

Statements about “the way to secure patient confidentiality and dignity” (e.g., confidence, privacy, security of documents) Statements about “the way to make full disclosure for patient’s information and decision-making” (e.g., patients knowing their own disease and condition after treatment, communication, recommendation, patient’s responsibility, second opinion, and right to make decision and take responsibility) Information and self-determination Confidentiality and dignity Free to choose Best interests of patient

Public health duty

Protection of patients’ rights Teamwork Interpersonal skill with patients Medical knowledge

and clinical skills

The 66 items devised for the survey instrument were distributed to 10 experienced medical education re-searchers who were asked to judge the content validity of the dimensions proposed in order to delineate the ideals of professionalism.

2.2. Sample

The collection of data was undertaken from April to June 2007. After the authors first obtained permission from the directors of four medical schools in Taiwan, representatives of each medical school class issued and collected questionnaires during their core course lec-tures. Two medical schools in general universities were private, one located in Taipei County and one in Hualien city. Two medical schools in dedicated medical univer-sities were private, located in Taipei City and Taichung City. The plan was to survey first- to fourth-year under-graduate medical students; however, we faced limita-tions in terms of the appropriate number of students representing all years.

Since some students missed classes or were unwill-ing to complete the questionnaires, we carried out a second application in order to include those who missed the first run. Of the total 860 questionnaires issued, 440 completed questionnaires were subse-quently collected, yielding a response rate of 51.2%.

2.3. Study design

This study incorporated into the survey instrument the codes of conduct listed for physician associations in the United States, Britain, Japan and Taiwan.16–36 Both deductive and inductive methods of generating items for scale development were used, as suggested by Hinkin.40 In Figure 1, we recapitulate the themes and validate the five dimensions of physicians’ codes of conduct.

“Medical knowledge and clinical skills” are defined as applying to an occupation that involves specialized knowledge of a subject, field or science, and which in-variably involves prolonged academic training, formal qualification, and prestige. “Interpersonal skill with pa-tients” refers to the major principle to which a physi-cian adheres when interacting with patients, such as treatment, communication, and financial or legal is-sues. “Teamwork” is defined as physicians smoothly working together with others, such as nurses, general staff and other physicians. “Public health duty” refers to disease prevention and the reporting and eradication of notifiable diseases. Finally, “the protection of pa-tients’ rights” is defined as the commitment by physi-cians to ensuring the fundamental rights of patients, as defined in the Declaration of Lisbon.

The items were rephrased from the original medical associations’ codes of conduct, allocated to appropriate constructs by the first and fourth authors, and pretested

on a total of 29 fifth-year medical students. Interrater reliability was reasonable (> 0.7). A six-point Likert scale was used to measure the perceived degree of im-portance of being a “good” doctor, with the response ranging from 1 for “least important” to 6 for “most important”.

Afterwards, construct validity was further tested. We achieved a fairly good index for overall fit (RMSEA = 0.07; GFI = 0.07), a very good incremental fix index (NFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97), and a very good parsi-mony fit index (PNFI = 0.93; PGFI = 0.067). The results of confirmatory factor analysis supported the good con-struct validity of this instrument.

We applied three steps to handling missing data. First, we excluded the questionnaires if they were in-complete. Second, we excluded cases if they failed a consistency check. Therefore, our dataset includes a few missing entries. And finally, we used listwise dele-tion (a convendele-tional method) to exclude cases from samples.41

3. Results

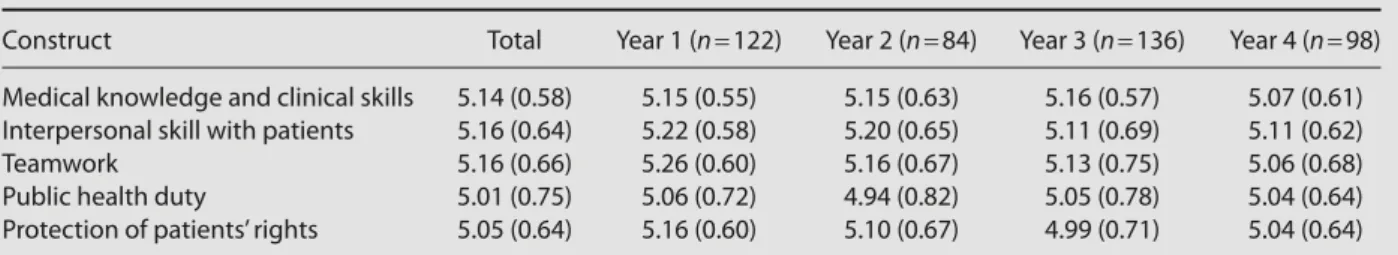

Of the total study sample, males accounted for 254 (57.1%) of the sample, with an average age of 21.3 years (standard deviation = 2.6). There were 122 (27.9%) first-year students, 84 (19.1%) second-year students, 136 (30.8%) third-year students, and 98 (22.2%) fourth-year students. Table 1 provides details of the responses on the five dimensions of the code of conduct by these groups of students.

3.1. Medical knowledge and clinical skills

The respondents gave high valuation to items relating to learning and professional competency, such as con-tinuous learning (mean = 5.4), knowledge and skills (mean = 5.6), and appropriate diagnoses (mean = 5.6), but relatively low valuations to items related to the de-velopment of new skills and treatment methods (mean = 4.8), research (mean = 4.6), and teaching (mean = 4.7). The Cronbach’s alpha for this dimension was 0.88.

3.2. Interpersonal skill with patients

The respondents indicated relatively high concern for items such as compassion, integrity, equity, and com-munication skills; however, one exception was the item “charge for those services rendered by me” (mean = 4.7). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

3.3. Teamwork

In contrast to their relatively low valuation of “compli-ance with the administrative policies of the hospital” (mean = 4.6), respondents showed that they highly

valued coordination, cooperation, and knowledge shar-ing. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

3.4. Public health duty

Respondents put high emphasis on reporting notifia-ble diseases, but gave a relatively lower valuation for “help to enact health-related legislation” (mean = 4.9) and “encourage health promotion within the commu-nity” (mean = 4.9). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

3.5. The protection of patients’ rights

The design of the items in this dimension was based mainly upon the Declaration of Lisbon on the Rights of the Patient.36 Since the declaration focuses not only on ordinary patients, but also on terminally-ill and legally-incompetent patients, the items covered a wide range of ethical issues. The student answers demonstrated that they paid attention to items such as “patients de-serve a full explanation of their disease, treatment, and prognosis” (mean = 5.2), “being assured of full confiden-tiality and dignity” (mean = 5.3), and “humane terminal care” (mean = 5.2), but gave relatively low valuations to items such as “the right to know the information tran-scribed in their medical records” (mean = 4.8), and “health education” (mean = 4.8). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

3.6. Subgroup analysis

This study undertook subgroup analysis of students in different grades. Notably, there were no statistically significant differences between the first-year and fourth-year students (Table 1). However, compared to students in earlier years of study, the fourth-year stu-dents had slightly lower valuations for the items indicated above, indicating perhaps that the edu-cational reforms were not fully in effect during their first years of study. Students in the medical schools of general universities rated relatively high compared to respondents in medical universities, with the ex-ception of pre-med students who gave relatively low

valuations to the dimension of “public health duty” (Table 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings

Students scored highest on teamwork and interper-sonal skills, followed by medical knowledge and skills. Students placed less importance on public health duty and protection of patients’ rights. This result is different from previous research which contended that medical students placed primary significance on the construct of medical knowledge and skills, paying less attention to the other constructs.42,43 Our research appears to show preliminary success of the current medical edu-cation reform designed to provide a medical humani-ties curriculum for pre-med students (that is, first- and second-year students). Nonetheless, student aware-ness of public health duties and patients’ rights protec-tion still demand improvements. We recommend redesigning future curriculum to raise the sense of public health duties and protection of patients’ rights among students.44

The slight gap between general universities and medical universities may reflect the greater emphasis on liberal art courses in the former. However, humani-ties are now a large part of the required program for medical undergraduates.12,45–47 At the same time, med-ical students face a heavy burden of basic science courses in the first and second years, squeezing out attention to the humanities. A follow-up longitudinal survey is needed to determine whether or not the goal of imbuing humanistic concerns in medical students is being achieved.

4.2. Instrument assessment

A major concern of this research was the quality of the instrument.14 This study measured the ideals of profes-sionalism extracted from the codes of conduct of major medical associations. We assessed the reliability and

Table 1 Medical students’ valuations of the dimensions of professionalism*

Construct Total Year 1 (n = 122) Year 2 (n = 84) Year 3 (n = 136) Year 4 (n = 98)

Medical knowledge and clinical skills 5.14 (0.58) 5.15 (0.55) 5.15 (0.63) 5.16 (0.57) 5.07 (0.61) Interpersonal skill with patients 5.16 (0.64) 5.22 (0.58) 5.20 (0.65) 5.11 (0.69) 5.11 (0.62)

Teamwork 5.16 (0.66) 5.26 (0.60) 5.16 (0.67) 5.13 (0.75) 5.06 (0.68)

Public health duty 5.01 (0.75) 5.06 (0.72) 4.94 (0.82) 5.05 (0.78) 5.04 (0.64)

Protection of patients’ rights 5.05 (0.64) 5.16 (0.60) 5.10 (0.67) 4.99 (0.71) 5.04 (0.64)

*Data presented as mean (standard deviation). Scale of valuation (approximate translation): 1 = I think it is very unimportant; 2 = I think it is unimportant; 3 = I think it is somewhat unimportant; 4 = I think it is somewhat important; 5 = I think it is important; 6 = I think it is very important.

validity of this instrument, and received desirable results. Therefore, we believe that this instrument is a reasonable device for evaluating pre-med and medical students’ stated professional values.

Any single aspect of professionalism, such as medi-cal knowledge and skills, might not comprehensively cover the principles of good doctoring. Compared to other instruments, which have problems of redun-dancy and narrow focus, this instrument covers multi-ple dimensions of professionalism.37,48,49

One reservation of this study was that it collected cross-sectional attitudes without considering recipro-cal learning in students’ clinirecipro-cal experiences, commu-nity participation, peer pressure, and possible role models.50 We provide the survey results as baseline data, and longitudinal study over time may clarify how the socialization process unfolds. Moreover, medical professionalism has long been developed in advanced countries such as the United States and England. We devised our instruments based on codes of conduct from advanced countries. Taiwan’s medical system has developed over the last 50 years via intense inter-actions with the United States. Today, its standard of living and legal process are comparable to that in de-veloped countries, and it has sought to meet interna-tional standards, so these codes are appropriate for defining Taiwan’s medical professionalism. The instru-ment additionally included some items that reflected the specific role of Taiwan’s physicians with regard to public health responsibilities. There is some cultural specificity to greater family cohesion in Taiwan and customary family care for hospital patients. Future ad-ditions to the instrument may reflect this.

4.3. Limitations

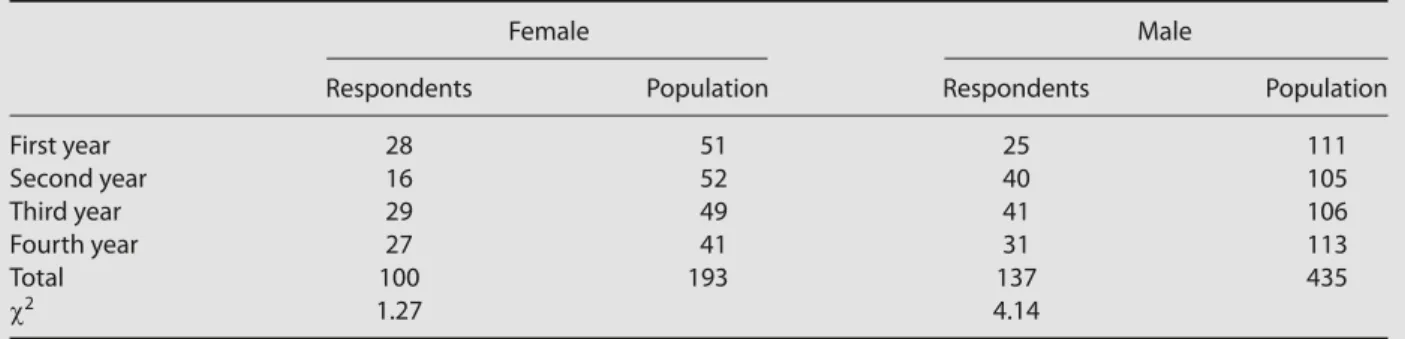

It should be noted that there are several research limi-tations. First, in asking how many students agree with the ideals of professionalism, we could not determine how fully they would apply these ideals in future action, especially after clinical practice.50 Second, the goodness of fit for generalization from respondents to the population was judged using only one demo-graphic variable from one medical school (Table 3). The results of this study may not apply to senior students, residents, and physicians. Further, for more objective measures, we need to seek public opinion on the behavior of the medical profession; however, this is beyond the range of this instrument.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 94-2416-H-038-005). The institutional review board permission number for this study is P970118. T able 2 V aluation of dimensions of pr of essionalism: c

omparison of the means*

C

onstruc

t

M

edical schools in medical univ

ersities

M

edical schools in general univ

ersities Y ear 1 ( n = 80) Y ear 2 ( n = 56) Y ear 3 ( n = 112) Y ear 4 ( n = 60) Y ear 1 ( n = 42) Y ear 2 ( n = 28) Y ear 3 ( n = 24) Y ear 4 ( n = 38) M edical k n o wledge and 5.14 (0.61) 5.11 (0.60) 5.11 (0.57) 5.02 (0.57) 5.19 (0.43) 5.22 (0.69) 5.36 (0.53) 5.14 (0.67) clinical sk ills In te rpersonal sk

ill with patients

5.28 (0.59) 5.14 (0.67) 5.07 (0.71) 5.03 (0.61) 5.11 (0.68) 5.33 (0.61) 5.33 (0.60) 5.22 (0.6 0) Team w o rk 5.31 † (0.61) 5.14 (0.64) 5.06 (0.77) 4.96 (0.66) 5.17 (0.56) 5.21 (0.75) 5.47 † (0.57) 5.21 (0.69) P

ublic health dut

y 5.09 (0.79) 4.96 (0.83) 5.01 (0.79) 4.94 (0.72) 4.97 (0.59) 4.89 (0.81) 5.27 (0.71) 5.17 (0.73) P rot ec tion of patients ’ rights 5.18 (0.66) 5.07 (0.68) 4.95 (0.71) 4.99 (0.55) 5.13 (0.47) 5.17 (0.65) 5.16 (0.72) 5.11 (0.77) *Data pr esent ed as mean (standar d deviation); †p < 0.05.

Table 3 Goodness of fit on sex for the respondents and population of one medical school

Female Male

Respondents Population Respondents Population

First year 28 51 25 111 Second year 16 52 40 105 Third year 29 49 41 106 Fourth year 27 41 31 113 Total 100 193 137 435 χ2 1.27 4.14

References

1. Arnold L, Stern DT. What is medical professionalism? In: Stern DT.

Measuring Medical Professionalism. New York: Oxford University

Press, 2006.

2. Sullivan WM. Medicine under threat: professionalism and pro-fessional identity. Can Med Assoc J 2000;162:673–5.

3. Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism: a contract between medi-cine and society. Can Med Assoc J 2000;162:668–9.

4. Hafferty FW. Definitions of professionalism—a search for mean-ing and identity. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;449:193–204. 5. Cohen JJ, Cruess S, Davidson C. Alliance between society and

medicine. The public’s stake in medical professionalism. JAMA 2007;298:670–3.

6. Irvine D. The performance of doctors. II: Maintaining good practice, protecting patients from poor performance. BMJ 1997; 314:1613–5.

7. Tai CK, Lee MB. Health Professionals and Social Responsibility. Taipei: Ministry of Education Republic of China Press, 2007. 8. Chiu CH, Arrigo LG, Tsai DJ. A historical context for the growth

of medical professionalism and curriculum reform in Taiwan.

Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2009;25:510–4.

9. Irvine D. The performance of doctors. I: Professionalism and self regulation in a changing world. BMJ 1997;314:1540–2.

10. Hafferty FW. What medical students know about professional-ism. Mt Sinai J Med 2002;69:385–94.

11. Huang KY. White Paper on Medical Education. Taipei: Medical Education Committee of Ministry of Education, 2002.

12. Rosovsky H. The University: An Owner’s Manual. London: W.W. Norton & Co., 1991.

13. Chiu CH, Tsai DJ. Medical education reform in Taiwan. Med Teach [In press]

14. Veloski JJ, Field SK, Boex JR, Blank LL. Measuring professionalism: a review of studies with instruments reported in the literature between 1982 and 2002. Acad Med 2005;80:366–70.

15. Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Hatala R, McNaughton N, Fronhna A, Hodges B, Lingard L, et al. Context, conflictual framework for evaluating professionalism. Acad Med 2000;75:S6–11.

16. American Medical Association. Principles of Medical Ethics. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2512.html [Date accessed: October 10, 2006]

17. British Medical Association. A Code of Practice for Private Practice. Available at: www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/Content/CCSCContractpri vMS?OpenDocument&Highlight=2,code [Date accessed: October 10, 2006]

18. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

AAPM&R Code of Conduct. Available at: www.aapmr.org/academy/

codea.htm#II [Date accessed: October 10, 2006]

19. American Association for Respiratory Care. AARC Statement of

Ethics and Professional Conduct. Available at: www.aarc.org/

media_center/position_statements/ethics.html [Date accessed: October 11, 2006]

20. American Academy of Neurology. AAN Code of Professional

Conduct. Available at: www.aan.com/globals/axon/assets/2500.

pdf [Date accessed: October 11, 2006]

21. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Code of Ethics and

Professionalism for Orthopaedic Surgeons. Available at: www.aaos.

org/about/papers/ethics/code.asp [Date accessed: October 11, 2006]

22. American College of Emergency Physicians. Code of Ethics for

Emergency Physicians. Available at: http://www.acep.org/practres.

aspx?id=29144 [Date accessed: October 11, 2006]

23. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE-CEC

Code of Ethical Standards. Available at: www.aace.com/meetings/

CEC/requirements.php [Date accessed: October 12, 2006] 24. The American Association of Physicists in Medicine. Guidelines

for Ethical Practice for Medical Physicists. Available at: www.aapm.

org/org/policies/details.asp?id=204&type=PP¤t=true [Date accessed: October 12, 2006]

25. American Psychiatric Association. The Principles of Medical

Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry. Available

at: http://www.psych.org/MainMenu/PsychiatricPractice/Ethics/ ResourcesStandards/PrinciplesofMedicalEthics.aspx [Date accessed: October 12, 2006]

26. American Medical Student Association. Principles Regarding

Stu-dent Rights and Responsibilities. Available at: http://www.amsa.org/

AMSA/Libraries/Exec_Docs/2009_AMSA_Preamble_Purposes_ and_Principles.sflb.ashx [Date accessed: January 12, 2010] 27. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Code of

Professional Ethics. Available at: http://www.acog.org/from_

home/acogcode.pdf [Date accessed: October 13, 2006] 28. Childbirth and Postpartum Professional Association. Code of

Con duct. Available at: www.cappa.net [Date accessed: October

13, 2006]

29. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. The Practice

Guide: Medical Professionalism and College Policies. Available at:

http://www.cpso.on.ca/policies/guide/default.aspx?id=1696 [Date accessed: January 12, 2010]

30. Australian Medical Association. AMA Code of Ethics—2004.

Editorially Revised 2006. Available at: www.ama.com.au/web.nsf/

tag/amacodeofethics [Date accessed: October 12, 2006] 31. Japan Medical Association. Principle of Medical Ethics. Available

at: www.med.or.jp/nichikara/ [Date accessed: October 14, 2006] 32. Taiwan Medical Association. White Paper for Ethics and Medical

Policy. Available at: www.tma.tw/ethical/doc/%A5%CD%A9R%

AD%DB%B2z%A5%D5%A5%D6%AE%D1.doc [Date accessed: October 14, 2006]

33. Taiwan Medical Association. Code of Ethics. Available at: www.tma. tw/ethical/ethical_01.asp [Date accessed: October 14, 2006] 34. World Medical Association. World Medical Association International

Code of Medical Ethics. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/

30publications/10policies/c8/index.html [Date accessed: October 15, 2006]

35. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/20activities/10ethics/10helsinki/ index.html [Date accessed: October 15, 2006]

36. Declaration of Lisbon on the Rights of the Patient 1981. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/l4/index. html [Date accessed: October 15, 2006]

37. Chapman DM, Hayden S, Sanders AB, Binder LS, Chinnis A, Corrigan K, LaDuca T, et al. Integrating the Accreditation Council for graduate medical education core competencies into the model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Acad

Emerg Med 2004;11:674–85.

38. Cohen R, Singer PA, Rothman AI, Robb A. Assessing competency to address ethical issues in medicine. Acad Med 1991;66:14–5. 39. Shaw K. The 2003 SARS outbreak and its impact on infection

control practices. Public Health 2006;120:8–14.

40. Hinkin TR. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ Res Methods 1998;1:104–21. 41. Allison PD. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications,

2001.

42. Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician—becoming a professional. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1794–9.

43. Smith P, Morrison J. Clinical clerkships: students can structure their own learning. Med Educ 2006;40:884–92.

44. Johnson I, Donovan D, Parboosingh J. Steps to improve the teaching of public health to undergraduate medical students in Canada. Acad Med 2008;83:414–8.

45. Huang KY. Put the humanities back to medical curriculum.

J Gen Educ 1996;3:1–16.

46. Liu JY, Tsai SM, Tang WH, Yeh J. On the analysis of the evaluation of general education in research-oriented universities. J General

Education: Concept & Practice 2006;1:263–302. Available at:

http://www.general.nsysu.edu.tw/download/papers/01-01/9_ %E5%8A%89%E9%87%91%E6%BA%90%E7%AD%89%EF%BC %9A%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6%E5%9E%8B%E5%A4%A7%E5 %AD%B8%E9%80%9A%E8%AD%98%E6%95%99%E8%82%B2 %E8%A9%95%E9%91%91%E4%B9%8B%E5%89%96%E6%9E% 90.pdf [Date assessed: August 20, 2009; In Chinese]

47. Veloski J, Hojat M. Measuring specific elements of professional-ism: empathy, teamwork, and lifelong learning. In: Stern DT.

Measuring Medical Professionalism. New York: Oxford University

Press, 2006.

48. Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med 2007;356:387–96.

49. Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, Veloski J, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med 2009; 84:1182–91.

50. Wilkes M, Raven BH. Understanding social influence in medical education. Acad Med 2002;77:481–8.