行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

論貨幣與市場

計畫類別: 個別型計畫

計畫編號: NSC91-2415-H-002-030-

執行期間: 91 年 08 月 01 日至 92 年 07 月 31 日

執行單位: 國立臺灣大學經濟學系暨研究所

計畫主持人: 李怡庭

報告類型: 精簡報告

處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 92 年 10 月 22 日

摘要

關鍵詞:貨幣;市場;中介;隨機配對

我們發現經濟社會中,許多交易都是透過專業中介來進行,例如超級市場以及銀

行等等,而隨著這些透過專業中介進行交易的市場的興起,也產生了促進交易的

媒介,例如提貨券和支票等等。本研究討論專業中介與交易媒介同時出現以解決

交易障礙的問題。在一個有欲望雙重不一致、充滿交易困難的經濟體中,其交易

機會是不確定、隨機的。人們可以選擇成為專業中介商、建立沒有交易障礙的有

組織性的市場,並且以專業中介商發行的私人債務工具來進行交易。由於非組織

性市場具有交易機會是隨機的,且所有人的交易歷史都是私有資訊的特性,人們

並沒有義務接受中介商發行的債務工具。我們發現,只要折現率不會太大,該經

濟體存在一個所有人都在有組織性的市場進行交易的均衡。而當交易障礙不會太

大或太小時,有組織性市場和非組織性隨機交易的市場同時存在,而且專業中介

發行的私人債務工具在整個社會流通成為交易媒介。由於人們發現使用該專業中

介發行的私人債務工具可以解決非組織性市場中的交易困難,使得這些債務工具

得以流通成為交易媒介,因此我們得到了 “內部貨幣” (inside money) 伴隨著中

介商的存在而興起的現象。

Abstract

Key words: Money; Market; Intermediation; Random matching

This paper studies the role of alternative transaction mechanisms, where privately issued trade credit may be used as a general medium of exchange. We depict an economy with trade frictions in which people can choose between two trading arrangements — unorganized sector, where agents meet bilaterally and in random, and organized markets, which resemble Walrasian markets. Commodity prices in the organized markets are determined by the competitive condition that merchants’ profits equal opportunity cost. When deciding which sector to conduct trade, people take into account the trade-off between the saving in waiting cost and the higher commodity price in the organized markets. Merchants in the organized markets issue bills of exchange to sellers, and all merchants honor the bills issued by other merchants. We find that, as long as the discount rate is small, all transactions take place in the organized markets, regardless of the degree of trade frictions. This case resembles a Walrasian equilibrium. If trade frictions are not too low or too high, organized markets exist and bills of exchange serve as the medium of exchange in the unorganized sector, where people’s trading histories are private information. The model developed here is therefore a simple model of inside money: bills of exchange are used in the organized markets, and possibly circulate in the unorganized sector also, and they are liabilities of merchants.

1

Introduction

The recent development of search monetary models have shown success in explaining the mech-anisms under which fiat money is accepted as a medium of exchange, coexistence of money and credit, and many monetary policy issues. These models, by studying trading procedures more closely, yield intuitions that are hard to generate in Walrasian equilibrium models. Search mod-els and Walrasian modmod-els are endowed entirely different views towards the way that exchange is conducted. In search models, agents trade bilaterally in a random manner, which depicts the least organized form of economic activity. Walrasian models postulate the existence of markets where sellers and buyers can always locate the relevant markets without search.

While we do not observe that all trades are perfectly coordinated as depicted in Walrasian models, it may not be completely satisfactory to assume no trade is intermediated by some institutions. In real world, there exist middlemen, merchants, traders and banks — a system of intermediary which coordinates exchange between various commodities at a time, between present commodities and future commodities, and between present money and future money. Accompanying the existence of markets organized by specialized traders there may arise tradable objects to facilitate exchange.

This paper studies the role of alternative transaction mechanisms, where privately issued trade credit may be used as a general medium of exchange. We consider a model with a double-coincidence problem, as in Kiyotaki and Wright (1991, 1993), where agents can choose between two trading arrangements. One is called ‘unorganized sector’ where agents meet bilaterally in random, and the other is ‘organized markets’ set up by merchants, which resemble Walrasian markets. Merchants do not produce, they only buy and sell goods and make profits from providing the intermediation service. Commodity prices in the organized markets are determined by the competitive condition that merchants’ profits equal opportunity cost. When deciding which sector to conduct trade, people take into account the trade-off between the saving in waiting time and the higher commodity price in the organized markets.

Merchants issue bills of exchange to producers for their commodities. Similar to Calvacanti and Wallace (1999), we assume complete information regarding trading histories of merchants, and punishment on defecting merchants is feasible. This implies that all merchants in the

organized markets honor the bills issued by other merchants.1 An agent, once acquiring a bill of exchange, can spend the bill in the organized markets or in the unorganized sector, in which agents’ trading histories are private information. The model developed here is therefore a simple model of inside money: bills of exchange are used in the organized markets, and possibly circulate in the unorganized sector also, and they are liabilities of merchants. The extent of organized markets, amount of inside money and merchants’ profits are all determined endogenously.

Equilibria are characterized by whether there are active organized markets and whether private liabilities are used as a general medium of exchange. As long as the discount rate is small, all transactions take place in the organized markets, regardless of the degree of trade frictions. This case resembles a Walrasian equilibrium. If trade frictions are not too low or too high, organized markets arise and bills of exchange circulate as a general medium of exchange in both sectors. When trade frictions are low, conducting trade in the unorganized sector is so attractive that it may not leave sufficient profits for the intermediation business. If trade difficulties are high, it would be too time-consuming for bill holders to encounter trade opportunities in the unorganized sector, and so circulation of bills would be confined in the organized markets.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the basic model. Section 3 characterizes stationary equilibria. Section 4 concludes.

2

The Basic Model

Time is discrete and continues forever. The economy is populated by a [0, 1] continuum of infinitely-lived agents. Let T be the set of goods. These goods are divisible but not storable once divided. Goods come in units of size one. Each agent i consumes goods in a subset Ti⊂ T

and cannot consume goods not in Ti. Let u > 0 be the instantaneous utility from consuming

an agent’s consumption good and r his discount rate. When agent i consumes q units of his consumption goods he enjoys utility qu. He can produce just one good at a time, which is not in Ti, at a cost in terms of disutility c. Assume that agents must consume in order to produce, and

the resulting implication is that agents holding asset cannot barter (an alternative assumption

1

Assumptions in random matching models include the lack of commitment and private information concerning trading histories. However, to study some form of credit in a random matching model, such as bills of exchange considered here, one needs to weaken the above assumptions.

is considered in section 5).

The set of agents is symmetric in the sense that the same number of agents consume each good and the same number of agents produce each good. This leads to the following: whenever you meet someone, there is a probability x that he consumes what you produce. The probability that the randomly encountered partner also produces what you consume is x. Thus, the probability of a “double coincidence of wants” is x2, which also measures the difficulty of direct barter in the model.

In this economy agents meet bilaterally and at random. The potential trade partner’s type and inventory are observable. Agents are unable to commit to future actions, and proposed transfers cannot be enforced. Trade history is private information to the agent (except a subset of agents, see below). Transactions thus take the form of barter or may be facilitated by some tangible asset. Because goods are not storable once divided, barter trade is one-for-one swap.

Every agent is endowed with a production opportunity. A fraction M ∈ [0, 1] of the agents are randomly chosen to be endowed with the ability to organize a market of consumption goods. Those agents are potential merchants. A potential merchant will enter as long as the profits earned from providing the intermediation service are at least as large as the expected returns to an ordinary producer-consumer. Once a potential merchant enters, he can no longer produce goods. Thus, merchants in this model buy and sell goods but they do not produce. Each merchant sets up a store of the commodity that he wishes to consume. Given the assumption on preference and symmetry, there are many merchants in the market of a particular commodity, and we consider merchants run business under competitive conditions. Once the organized markets exist, an agent can always locate the market of the commodity that he wishes to buy or sell without search.

Trades in the organized markets are proceeded in the following fashion. Merchants issue bills of exchange to the sellers for their products.2 Bills of exchange are indivisible. Agents holding bills may buy goods in the organized markets or in the unorganized sector, where agents’ trading histories are private information. If a consumer buys a commodity from a

2

One may suspect that results depend on our assumed exclusive privilege for merchants to print bills of exchange. However, if we assume everyone has the technology to print bills, since agents in the unorganized sector can not be monitored and can not commit to future actions, the equilibrium result is that no one will accept a bill issued by non-merchants.

merchant, he gets q units and the merchant gets 1 − q units of the goods. Since merchants in a market compete for customers, the quantity of goods that a bill can buy, q, is determined by the competitive condition — merchant’s profits equal the opportunity cost, the expected value to a producer-consumer. Similar to Calvacanti and Wallace (1999), we assume that, once the organized markets exist, there is complete information regarding trading histories of merchants and punishment on defecting merchants is feasible.3 Under some no-defection conditions, all merchants in the organized markets honor the bills issued by other merchants.4

3

Symmetric stationary equilibrium

We focus on symmetric equilibria where strategies and distributions are time-invariant, and agents in identical states (regardless of their consumption types) choose identical actions. Strategies

Let P denote the proportion of agents who can produce goods (called producers) and B the proportion of agents who hold bills of exchange (called consumers). An agent is in one of the following states: being a producer, a consumer or a merchant. Producers need to decide where to sell their products; consumers decide where to spend the bills for consumption goods. Let Sp and Sb be the equilibrium probability that a producer and a consumer, respectively, chooses

to trade in the unorganized sector. Thus, at a point of time, P Sp and BSb are measures of

producers and bill holders, respectively, who trade in the unorganized sector; P (1 − Sp) and

B(1 − Sb) are measures of producers and bill holders, respectively, who trade in the organized

markets. Agents resume the decision process after production and consumption are completed. In the unorganized sector, a producer may encounter another producer and if there is a double coincidence of wants, a barter trade takes place. A producer may also encounter a bill holder,

3

We can imagine that the society is able to keep a public record of transactions of merchants once the organized markets are active. If organized markets do not exist, then all agents trade in the unorganized sector and their trading histories are private information.

4To rule out credit, we assume that agents who arrive in the organized markets can not communicate with

each other, though each can communicate with the merchant. The timing within the period is as follows. Agents arrive at a store in the organized markets and contact the merchant sequentially. After all arrivals, the merchant determines the price q. Producer each produces a good, gets a unit of bill and leaves the store. Then consumers and the merchant consume their shares of the goods.

and in that situation he must decide whether to accept the bill as payment for his production. Let Σ denote the probability that a random producer accepts a bill in the unorganized sector, and σ an individual’s best response. In equilibrium, σ = Σ.

Value functions

Let Vj, j = p, b and m, denote the end-of-period expected life-time utility to a producer, bill

holder and merchant, respectively. Let wp and wb denote the expected payoff to a producer and

a bill holder, respectively, trading in the unorganized sector:

wp ≡ P Spx2(u − c) + BSbx maxσ σ(Vb− Vp− c, 0)

wb ≡ P SpxΣ(u + Vp− Vb).

A producer encounters a double-coincidence trade opportunity with probability P Spx2. He meets

a consumer who wants his good with probability BSbx, and in that situation he receives the

gain from accepting a bill of exchange. The Bellman’s equations satisfy:

rVp = max sp {wp , Vb− Vp− c} (1) rVb = max sb {wb, qu + Vp− Vb} (2) rVm = [P (1 − Sp)(1 − q)u]/M. (3)

Equation (1) and (2) set the flow return to a producer and a bill holder, respectively. Because merchants are identical and compete for customers, in equilibrium they earn identical expected profits. Equation (3) shows that each merchant in the market of a commodity gets an equal share of business, P (1 − Sp)/M units of goods, each of which results in profits (1 − q)u.

Best response conditions

An agent chooses his strategies taking as given those of others, value functions and the expected terms of trade. Let (sp, sb, σ) denote an individual’s best response when he takes as

given everyone else’s strategies (Sp, Sb, Σ). A producer’s decision as whether to trade in the

unorganized sector is described by

sp = 1 if wp > Vb− Vp− c ∈ [0, 1] if wp = Vb− Vp− c = 0 if wp < Vb− Vp− c. (4)

A bill-holder’s decision as whether to trade in the unorganized sector is sb = 1 if wb > qu + Vp− Vb ∈ [0, 1] if wb = qu + Vp− Vb = 0 if wb < qu + Vp− Vb. (5)

A similar best response condition holds for a producer’s strategy σ as whether to accept a bill offered in the unorganized sector. Note that if Vb− Vp− c < 0 organized markets would

not exist because producers’ expected payoff from search is bounded by the gains of barter.5 If organized markets are inactive, no bills would be issued, and so the strategy σ is irrelevant. Thus, in equilibrium if bills of exchange ever exist, they will be accepted in the unorganized sector (Σ = 1). Circulation of bills outside the organized markets thus is determined by whether bill holders find it profitable to spend the bills in the unorganized sector.

It remains to specify the condition for determining merchant’s profits. Competition among merchants results in no-surplus condition; that is, the expected profits earned equal the oppor-tunity cost — the expected payoff to a producer-consumer. Hence, the value of bills of exchange in the organized markets, q, is determined by

Vm = Vp. (6)

We now check whether a merchant has an incentive to defect by not honoring bills of exchange issued by other merchants. Assume that defection by a merchant is punished by having the defecting merchant get the payoff from autarky, which is zero. By defection, we mean that a merchant consumes all the goods in inventory and does not redeem any bills presented to him. If a merchant defects, he gets utility P (1 −Sp)u/M. If a merchant chooses to stay in business, he

enjoys utility P (1 − Sp)(1 − q)u/M and the continuation value Vm. The no-defection condition

thus implies

P (1 − Sp)u/M ≤ P (1 − Sp)(1 − q)u/M + Vm (7)

The steady state requires the outstanding bills of exchange be constant; i.e., the amount of bills issued equals the amount of bills destroyed every period,

P (1 − Sp) = B(1 − Sb). (8)

5

Since the creation and redemption of bills involve the exchange of goods, (8) can be interpreted as a condition that equates goods supplied and goods demanded in the markets. Finally,

P + B + M ≡ 1. (9)

Definition 1 A symmetric stationary equilibrium with active organized markets is a vector of value functions V = (Vp, Vb, Vm), trading strategies S = (sp, sb, σ), price q, and steady state

distribution p = (P, B) such that (i) given S, q, and p, value functions V satisfy (1) — (3); (ii) given V, S, and p, price q satisfies (6); (iii) given V, q, and (sp, sb) = (Sp, Sb), σ = Σ = 1,

strategies S satisfy (4) and (5); (iv) given V, S, p and q, no-defection condition (7) is satisfied; (v) p satisfy (8) and (9).

3.1

Existence of Equilibria

First, a stationary equilibrium without organized markets always exists. If it is believed that no potential merchants would set up the markets, then Sp = 1 is the unique best response. If all

producers sell products in the unorganized sector, no potential merchants would enter, and no bills of exchange would be issued. Hence Vp > 0 and Vm = 0 sustain the equilibrium strategies.

Potential merchants take up the role as a producer-consumer. Only barter takes place in this economy.

There are three types of equilibria with organized markets. When all producers trade in the organized markets, so do the consumers, Sp = 0, Sb = 0. If producers are indifferent between

trading in the organized and unorganized sectors, Sp ∈ (0, 1), the use of bills may be limited

in the organized markets, Sb = 0, or may circulate also in the unorganized sector as a medium

of exchange, Sb ∈ (0, 1). Note that Sb = 1 is not consistent with the existence of organized

markets, since in steady state bills of exchange must be created and destroyed.

The following proposition concerning the existence of equilibrium that all trades take place in the organized market — a fully organized markets equilibrium.

Proposition 1 For sufficiently small r there exists a fully organized markets equilibrium. Proof: Given (Sp, Sb) = (0, 0), P = B = (1 − m)/2 by (8). The strategy sp = 0 is the best

response if and only if Vb− Vp− c > 0, which is satisfied iff r < (u − c)/c. The strategy is the

Vb > 0. Equation (6) thus can be solved for q = 2cM (1+r)+(1−M)(2+r)u[2+(1−M)r]u . One can show that for

any M ∈ (0, 1), q ∈ (0, 1) iff r < (u − c)/c. Thus, Vm > 0. Also, the no-defection condition (7)

is satisfied iff q ≤ 1+r1 , which implies r ≤

−2cM−(1−M)u+√(1+M )u[2cM +(1−M)u]

2cM +(1−M)u .

The fully organized markets equilibrium resembles a Walrasian equilibrium, underlying which the mechanism is interpreted as follows. Specialized traders organize markets for various com-modities. Each producer sells product in the market of his production good, receives a bill of exchange, and redeems it next period in the market of his consumption good. A distinction from Walrasian equilibrium is here the equilibrium involves the use of a medium of exchange. Notice that in the present model, though there is complete information regarding merchants’ trading histories, an ordinary producer-consumer’s trading history remains private information. A tangible asset is thus necessary for transactions between merchants and consumers.

Now consider the equilibrium where consumers always spend bills in the organized markets but producers find it equally profitable to trade in the organized and unorganized sectors, Sp ∈

(0, 1), Sb= 0. Only barter takes place in the unorganized sector.

Proposition 2 If trade frictions are very low or very high and the discount rate is small, the organized markets are active and the use of bills of exchange is limited in organized markets.

Proof: See Appendix.

The key element for the existence of this equilibrium lies in the incentive for buyers not to spend bills in the unorganized sector. When x is small, it’s hard to have a single-coincidence match for bill holders and so always making purchase in the organized markets is incentive compatible. When x is large, barter is easy, and so bill holders like to redeem the bills in the organized market and become a producer as soon as possible to take advantage of easy barter trade. This is so particularly when the discount rate is big, because a higher rate of discounting makes the time-consuming exchange process more troublesome. Indeed, we find that, as r is sufficiently big, always trading bills in the organized markets is the best response for all x. However, the no-defection condition for merchants would be violated if the discount rate is too high, because the discounted utility of staying in business would not be high enough.

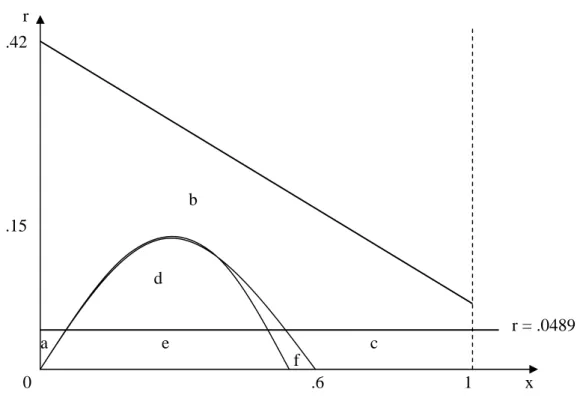

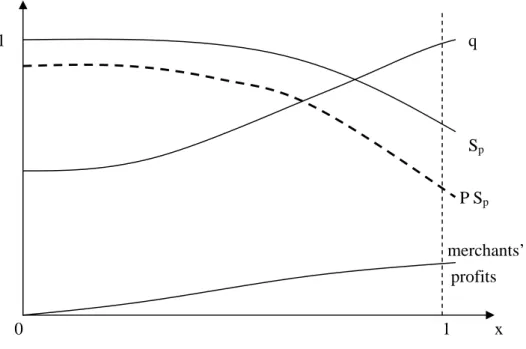

Figure 1 illustrates existence of equilibria, and figure 2 shows how the strategic variables, prices and merchant’s profits in this equilibrium depend on the trade frictions.6 Note that the

6

value of notes, merchants’ profits and the extent of organized markets all increase as trade be-comes easier in the unorganized sector. Perhaps a surprising phenomenon is that the measure of producers trade in the unorganized sector, P Sp, decreases as trade frictions fall. This seemingly

counter-intuitive result can be explained as follows. When trade frictions fall, producers’ ex-pected returns of trading in the unorganized sector rise, and so merchants need to offer a higher q to attract customers. Merchant’s profits would be sustained only if there is more business, to compensate the lower profit margin. This is possible only if more producers supply goods to the organized markets; i.e., more transactions take place in the organized markets and the extent of market is larger.

Note that in the model considered here, the extent of market does not affect trading efficiency in the organized markets, but it affects trade difficulties in the unorganized sector. That is, as more transactions take place in the organized markets, it is more difficult to conduct trade in the unorganized sector, because the probability of meeting a trade partner depends on the number of traders. Thus, agent’s decision to trade in the organized markets creates a negative externality to those who trade in the unorganized sector.

We next consider the equilibrium where bills are used as a general medium of exchange in both sectors. We discuss this equilibrium with observations from numerical experiments. Given other parameters, the best response conditions for sp ∈ (0, 1) and sb ∈ (0, 1) hold when x is

not too low or too high (see figure 1). Generally, this equilibrium exists at a range of x under which the equilibrium with sb = 0 does not exist, with reasons similar to what discussed above.

This equilibrium does not exist when r is sufficiently large, because trading in the unorganized sector is too time-consuming. When the discount rate falls, the existence region in terms of x is enlarged, so there is a trade-off between the discounting effect and trade difficulties. If there are less potential merchants in the economy, this equilibrium can exist at a lower value of x. A smaller M implies easier trade in the unorganized sector because the matching probability is proportional to the number of agents who engage in trade.

3.2

Welfare

We have demonstrated a case in that merchants set up markets, operate under competitive conditions, and associated with the emergence of markets the privately-issued trade credit may

be used as a general medium of exchange. A natural question is whether the emergence of markets and inside money is welfare improving. We use the weighted average flow returns W as the criterion to discuss welfare issues, where

W = r(P Vp+ BVb+ M Vm). (10)

Proposition 3 The equilibrium with organized markets and inside money dominates the pure barter equilibrium, when x or M is small.

In a pure barter equilibrium all agents are identical and W = rVp = x2(u − c). In the

equilibrium with active organized markets and inside money, Vp, Vb, Vm are all decreased by the

number of merchants. Hence, this equilibrium dominates a pure barter equilibrium when M or x are small. The reason lies in the assumption that merchants in this economy do not produce; they are trade agencies only. A bigger x makes barter easier and so the benefit of organized markets in facilitating trade may not be big enough to compensate the loss in resources used for providing intermediation service.

4

Conclusions

In this paper we depict an economy with trade frictions, where merchants may arise to set up markets and associated with the emergence of markets, the privately-issued trade credit may be used as a general medium of exchange. The trade credit issued by merchants is a kind of inside money; it is used in the organized markets and may also be used in the unorganized sector where people’s trading histories are private information.

Some previous studies considering explicitly trade frictions and the choice of different trading arrangements include Camera (2000) and Camera and Li (2003). Camera (2000) considers a costly matching technology that provides deterministic matches where agents conduct barter trade. In Camera and Li (2003) we consider intermediated credit trade with default risk. The major difference of this article is that I show how the emergence of a medium of exchange and the emergence of intermediaries are related, and the effect on the equilibrium level of specialization. For tractability we use a simple divisible goods setup that allows us to model merchant’s profits while every trade in the unorganized sector is one-for-one swap, so one did not need to determine the value of bills in the unorganized sector using bilateral bargaining. The value of

bills in the organized markets is determined by a competitive condition that merchants’ profits equal opportunity cost.

This paper does not consider outside money, but one can study the competition of credit (bills of exchange) and outside money, and how the competition produces a discount on the inferior one, in this model. Also for simplicity we assume that a predetermined subset of individuals are potential merchants, and trade efficiency in the organized markets is not affected by the number of merchants. An interesting question would be how trading efficiency of markets is affected by merchants’ entrance decision and the size of clientele served by merchants. We leave it for future research.

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 2. Given sb = 0, The value functions V = (Vp, Vb, Vm) are strictly positive

and inventory distribution p = (P, B) ∈ (0, 1) if sp ∈ (0, 1). We show it is the case when x is

close to 0 or close to 1. From wp = Vb− Vp− c one can solve for sp. When M is big, as x → 0,

sp→ 1 and ∂s∂xp|x→0< 0; as x → 1, sp→ 4[u−(1+r)c]+2rc2[u−(1+r)c] ∈ (0, 1) and ∂s∂xp|x→1< 0. Next, we check

q ∈ (0, 1). When M is big, as x → 0, q → 1 and ∂q∂x|x→0 < 0; as x → 1, q →

csp+u(1−2sp)

u(1−sp) > 0

since ∂sp

∂x|x→1 < 0. We also need to check whether the best response condition (5) for sb = 0 is

satisfied. When M is big, as x → 0, (qu + Vp− Vb− wb) → (1+r)(2−sru(2−sp)(1−sp)(1−sp)p) > 0; as x → 1,

(qu + Vp− Vb− yb) → (2−s(1+r)(2−sp)(u+cspp)+u(1−2s)(1−sp) p) > 0 since ∂s∂xp|x→1 < 0. When M is big, q → uc, and 1

1+r → 1, as r → 0. That is, as r is sufficiently small, q ≤ 1

1+r and so the no-defection condition

References

Camera, G. (2000) “Money, Search, and Costly Matchmaking,” Macroeconomic Dynamics, 4, 289-323.

Camera, G. and Y. Li (2003) “Default and Endogenous Risk in a Model of Money and Credit,” manuscript.

Cavalcanti, R. and N. Wallace (1999) “A Model of Private Bank-Note Issue,” Review of Eco-nomic Dynamics 2, 104-136.

Kiyotaki, N. and R. Wright (1991) “A contribution to the pure theory of money,” Journal of economic theory 53, 215-235.

Kiyotaki, N. and R. Wright (1993) “A search-theoretical approach to monetary economics,” American economics review 83, 63-77.

r .42 b .15 d r = .0489 a e c f 0 .6 1 x

Fullly organized markets equilibrium: areas a, e, f, c Equilibrium Sp = (0,1), Sb = 0: areas a, b, c

Equilibrium Sp = (0,1), Sb = (0, 1): areas d, e

1 q Sp P Sp merchants’ profits 0 1 x