Cognitive behavioural therapy for primary insomnia: a systematic

review

Mei-Yeh Wang

MSN RNLecturer, Cardinal Tien College of Nursing; and Doctoral Program Student, School and Graduate Institute of Nursing, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Shu-Yi Wang

MSN RNLecturer, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

Pei-Shan Tsai

PHD RNAssistant Professor, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

Accepted for publication 8 October 2004

Correspondence: Pei-Shan Tsai, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, 250 Wu-Hsing Street, Taipei 110,

Taiwan.

E-mail: ptsai@tmu.edu.tw

W A N G M . - Y . , W A N G S . - Y . & T S A I P . - S . ( 2 0 0 5 )

W A N G M . - Y . , W A N G S . - Y . & T S A I P . - S . ( 2 0 0 5 ) Journal of Advanced Nursing 50(5), 553–564

Cognitive behavioural therapy for primary insomnia: a systematic review

Aim. This paper reports a systematic review of seven studies evaluating the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for persistent primary insomnia.

Background. Insomnia is one of the most common health complaints reported in the primary care setting. Although non-pharmacological treatments such as the CBT have been suggested to be useful in combating the persistent insomnia, the efficacy and clinical utility of CBT for primary insomnia have yet to be determined. Method. A systematic search of Ovid, MEDLINE, psychINFO, PsycARTICLES, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases of papers published between 1993 and 2004 was conducted, using the following medical subject headings or key words: insomnia, primary insomnia, psychophysiological insomnia, sleep maintenance disorders, sleep initiation disorders, non-pharmacological treatment, and cognitive beha-vioural therapy. A total of seven papers was included in the review.

Findings. Stimulus control, sleep restriction, sleep hygiene education and cognitive restructuring were the main treatment components. Interventions were provided by psychiatrists except for one study, in which the CBT was delivered by nurses. Among beneficial outcomes, improvement of sleep efficacy, sleep onset latency and wake after sleep onset were the most frequently reported. In addition, participants significantly reduced sleep medication use. Some studies gave follow-up data which indicated that the CBT produced durable clinical changes in total sleep time and night-time wakefulness. Conclusions. These randomized controlled trial studies demonstrated that CBT was superior to any single-component treatment such as stimulus control, relaxation training, educational programmes, or other control conditions. However, hetero-geneity in patient assessment, CBT protocols, and outcome indicators made deter-mination of the relative efficacy and clinical utility of the therapy difficult. Therefore, the standard components of CBT need to be clearly defined. In addition, a comprehensive assessment of patients is essential for future studies.

Keywords: cognitive behavioural therapy, insomnia, non-pharmacological treatment, nursing, sleep, systematic review

Introduction

Insomnia is one of the most prevalent psychological health problems worldwide. According to the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey, approximately 33% of those with insomnia in the United States of America (USA) reported occasional insomnia, and 9% reported sleep difficulties that occurred on a regular basis (Ancoli-Israel & Roth 1999). Sleep disturbance is a common complaint in general practice. Once it has become established it may persist for many years (Edinger et al. 2001). In addition, in 1995, the direct costs of assessing and treating insomnia were approximated as $14 billion in the USA (Walsh & Engelhardt 1999). Insomnia, therefore, is an important public health problem. Similarly, an epidemiological survey of the French population demon-strated that 29% of the respondents had insomnia symptoms occurring at least three times per week for a month (Leger et al. 2000). The prevalence of insomnia symptoms occurring at least three nights per week was 37Æ6% in a survey of the general population of Finland (Ohayon & Partinen 2002). The prevalence of insomnia has also been reported in Asian countries. A survey of the South Korean general population showed that insomnia symptoms at least three nights per week were reported by 17% of those surveyed (Ohayon & Hong 2002). The overall prevalence of insomnia in the Japanese general population has been reported as 21Æ4% (Kim et al. 2000).

Primary insomnia probably accounts for around 15% of the chronic insomnias. It is more common in women than in men and the usual age of onset is 20–40 years old (Martin & Ancoli-Israel 2002). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV) defines primary insomnia as a complaint lasting for at least a month, with difficulty in initiating and/or maintaining sleep or of non-restorative sleep (American Psychiatric Associa-tion 1994). Disturbance in sleep does not occur exclusively during the course of another sleep disorder or mental disorder, and is not because of the general medical condition. Primary insomnia is diagnosed when somatized tension and learned sleep-incompatible behaviours play a predominant role in the maintenance of poor sleep (Perlis et al. 1997). In other words, people with insomnia exhibit an apprehensive over-concern about sleep, while the maladaptive sleep-preventing behaviour perpetuates sleep disturbance. The International Classification of Sleep Dis-orders – Revised (ICSD-R) uses the term ‘psychophysiolog-ical insomnia’ for such a complaint and links it with decreased functioning during wakefulness (American Sleep Disorders Association 1997). The International Classifica-tion of Disorders, 10th EdiClassifica-tion (ICD-10) requires a

minimum frequency (at least three times a week) and duration (1 month) of any complaint corresponding to the symptoms of insomnia to make the diagnosis (World Health Organization 1992). It also specifies that the sleep complaint may cause marked personal distress or interfer-ence with personal functioning in daily living. It might be argued that insomnia is a symptom rather than a primary diagnosis, but untreated insomnia will lead not only to increased psychological distress, but also to such clinical conditions as anxiety and depression.

Primary insomnia is often treated pharmacologically, the most common treatment being the prescription of ben-zodiazepines. However, a number of problems are associ-ated with chronic hypnotic medications use, such as psychological dependence and tolerance, decreased daytime functioning, poor sleep quality, and rebound insomnia on withdrawal from the medication (Riedel et al. 1998). The other option that has been widely described is antidepres-sants. However, knowledge on the long-term effects of these is currently lacking. Although the symptoms could be relieved by medications within short period of time, the underlying mechanisms that sustain persistent insomnia remain unresolved. Because the effectiveness of hypnotic medications in long-term use has been controversial, non-pharmacological therapy could be an effective treatment alternative for persistent insomnia (Morin et al. 1999, Smith et al. 2002). In a meta-analysis of the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions for insomnia with adult groups, Morin et al. (1994) found an effect size of 0Æ88 for sleep onset latency (SOL), and an effect size of 0Æ65 for time awake after sleep onset (WASO). For primary insomnia in particular, multifaceted cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been developed to counteract its cognitive and/or behavioural mechanisms. In order to reverse the maladap-tive thoughts and behaviour patterns that perpetuate primary insomnia, it is suggested that CBT could be used in conjunction with one course of up to 1 month of hypnotic treatment (Perlis et al. 2001). Moreover, Hajak et al. (2002) found that behaviour therapy could reduce the dose of hypnotics in clinical settings.

The importance of psychosocial and behavioural factors in primary insomnia has been acknowledged. Several of the individual components of CBT are recommended as stand-ard treatment (stimulus control) or guideline treatment (progressive muscle relaxation), according to the American Psychological Association (Chesson et al. 1999). However, the efficacy of multifaceted CBT alone for primary insom-nia is still controversial. It is still not determined which components should be specifically combined as so-called CBT, and so it is still recommended as treatment option

only. Moreover, the assessment and diagnosis of primary insomnia mainly relies on subjective reports in clinical settings. Although a large number of people do experience sleep difficulties, not all meet the diagnostic criteria for insomnia. Many medical illnesses and emotional distur-bances also might cause sleep problems. Therefore, the method of assessment and diagnosis of patients needs to be carefully considered.

In this paper we analyse the existing literature to examine the efficacy of CBT alone as a treatment for primary insomnia. An assessment of CBT treatment protocols is also presented. In addition, directions for future research are addressed.

Search methods

Published studies related to CBT and primary insomnia were targeted. Although insomnia is common in older people, age-related changes such as the circadian rhythm changes complicate the mechanism that sustains insomnia. Therefore the age range of between 18 and 65 years was chosen. The main diagnosis was primary insomnia/psychophyiological insomnia according to DSM-IV/ICSD-R/ICD-10. Studies that included patients with other sleep disorders (e.g. circadian rhythm sleep disorder, periodic limb movements in sleep), severe medical conditions (e.g. cancer, dementia, end stage renal disease), severe psychiatric disorders (e.g. major depression, anxiety disorder), and substance use were excluded from the review because of confounding factors. Treatment strategies defined as multifaceted CBT included sleep scheduling (stimulus control and sleep restriction), progressive muscle relaxation, sleep hygiene education,

and/or cognitive reconstructions. Non-pharmacological

treatments directly targeting circadian rhythms (e.g. light exposure), white noise, acupuncture and exercise were all excluded. Studies included for review were restricted to those that included at least one of the following outcome variables: sleep onset latency, number/duration of awaking after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, sleep quality, beliefs and attitudes about sleep, and medication reduction. To be included, studies also had to be randomized controlled trial and in the English language.

A search of the electronic databases Ovid, MEDLINE, psychINFO, PsycARTICLES, CINAHL and EMBASE was conducted for papers published between 1993 and 2004, using the following medical subject headings or key words: insomnia, psychophysiological insomnia, sleep maintenance disorders, sleep initiation disorders, primary insomnia, non-pharmacological treatment and cognitive behavioural therapy.

The quality and strength of the studies were evaluated using the Jadad Scale for evaluating controlled clinical trials, which scores from 0 (poor) to 5 (excellent) (Jadad et al. 1996). The Jadad Scale evaluates three important elements of controlled clinical trials: randomization, double-blinding, and the description of withdrawals and dropouts. Papers with a Jadad score of two or higher were included in this review.

A total of 25 papers with the likelihood of meeting the inclusion criteria were retrieved in full. Each study was assessed and compared for suitability against the review inclusion criteria. Data were extracted by three reviewers independently. Three studies included a group of older people, six did not meet the inclusion criteria for outcome variables, one assessed light therapy and eight did not use a RCT design. Finally, only seven studies with a Jadad score of two or greater were included in the review.

Results

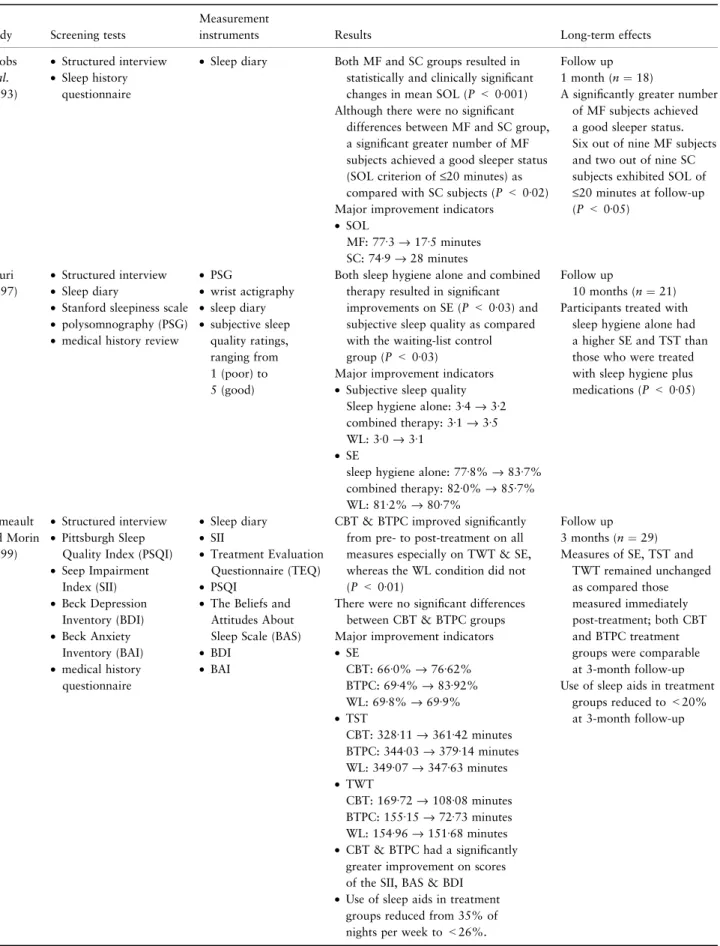

A total of seven papers was extracted for the review (see Table 1), and their participants were aged 36Æ7–64Æ7 years and had a mean duration of symptoms of more than 10 years. More than half were female. Participant screening, instru-ments, results, and long-term effects reported in these studies are summarized in Table 2.

Treatment components

Stimulus control and sleep hygiene were included in all studies except that by Hauri (1997), in which the behavioural treatment condition was restricted to sleep hygiene advice alone. Three studies employed cognitive reconstruction as one of the treatment components (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Espie et al. 2001, Morin et al. 2002). Two included relaxation training (Jacobs et al. 1993, Espie et al. 2001). Edinger and Sampson (2003) used an abbreviated format of CBT with only three components: stimulus control, sleep restriction and sleep hygiene. Participants were treated on an individual basis in most studies (6/7). In addition to CBT, bibliotherapy supplemented with audiocassette tapes was used in two studies (Edinger et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003) to examine the efficacy of self-help materials and the impact of professional guidance on outcomes. The CBT programmes were implemented on a weekly basis over a 6–10-week period. Each session lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. No reports gave the rationale for the treatment dosage. In seven studies, most of the interventions were provided by psychiatrists and only one used nurse-directed CBT (Espie et al. 2001).

Table 1 Sum mary of inclu ded stud ies Study Samp le charact eristics Inte rventio ns and cont rols Treat ment comp onents Jaco bs et al. (19 93) 16 fema les and fou r males were recruit ed via medi a advert isement or physicia ns-referral. Mean age wa s 36 Æ7 years and mean durati on of symp toms was 9 Æ1 years Two gro ups • Mu ltifactor beh avioural int ervention • Stimu lus cont rol Multif actor behavi oural in terventi on • St imulus con trol • R elaxati on respo nse • Sleep edu cation Hau ri (19 97) 19 fema les and seven males were rec ruited via m edia advert isement or self-refe rral. Mean age was 36 Æ7 years and me an durat ion of sympt oms wa s 1 3 Æ2 y ears Thre e group s • Sleep hygien e • Sleep hygien e and ph armacot herapy • Wai ting-list control s Sleep hyg iene • Sleep hyg iene adv ice • R elaxati on train ing (minor par t) • Sup portiv e therap y • Lo w-leve l cogn itive in terventi on Mim eault and Morin (19 99) 32 fema les and 22 m ales were re cruited via media advert isement . M ean age wa s 5 0 Æ8 years and mean durati on of symp toms was 14 Æ14 years. The m ajorit y o f participants (91 %) report ed mixed sleep-onset and mainten ance insom nia Thre e group s • Bibl iothera py • Bibl iothera py and phone consult ations • Wai ting-list control Cogni tive Behavi oural Therapy • St imulus con trol • Sleep rest riction • C ognitive therapy • Sleep hyg iene edu cation Edin ger et al. (2001) 35 fema les and 40 m ales were re cruited via media advert isement or self-refe rral. Mean age was 55 Æ3 years and mean durati on of symp toms was 13 Æ6 years Thre e group s • Cogn itive beh avioural therapy • Re laxati on traini ng gro up • Qua si desensitizati on group (Place bo therap y) Cogni tive Behavi oural Therapy: • St imulus con trol • Sleep rest riction • Sleep hyg iene edu cation Espie et al. (20 01) 95 fema les and 44 m ales were ph ysicians-referre d. Mean age was 51 Æ4 years. Ove r 40% of participants had expe rienced symp toms for more than 10 years Two gro ups • Cogn itive beh avioural therapy • Self-m onitoring control Cogni tive Behavi oural Therapy • Sleep sched uling • R elaxati on train ing • C ognitive therapy • Sleep hyg iene edu cation Morin et al. (20 02) 47 fema le and 25 m ales were re cruite d via newsp aper advert isement s. Mean age wa s 6 4 Æ7 years and mean durati on of symp toms was 17 years 25% of subject s were diagnos ed as difficu lty in maintai ning sleep, 6 Æ9% of subjects were diagn osed as difficu lty in initi ating sleep and 64% of subject s were diagnos ed as mixe d ty pe. The diagnos is of the rest of the subjects wa s unkno wn Fo ur gro ups • Cogn itive beh avioural therapy • Pharma coth erap y • Cogn itive beh avioural therapy and Pharma coth erapy • Plac ebo medi cation Cogni tive Behavi oural Therapy • St imulus con trol • Sleep rest riction • C ognitive therapy • Sleep hyg iene edu cation Edin ger and Samp son (20 03) Two females and eight males were self-referred or physic ians-refe rred. Mean age was 51 years and mean durati on of symp toms was unkno wn Two gro ups • Abb reviat ed cogn itive behaviou ral tre atment (ACB T) • Sleep hygien e recommend ations ACBT •St imulus con trol • Sleep rest riction • Sleep hyg iene edu cation

Table 2 Research on the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy on primary insomnia

Study Screening tests

Measurement

instruments Results Long-term effects

Jacobs et al. (1993) • Structured interview • Sleep history questionnaire

• Sleep diary Both MF and SC groups resulted in statistically and clinically significant changes in mean SOL (P < 0Æ001) Although there were no significant

differences between MF and SC group, a significant greater number of MF subjects achieved a good sleeper status (SOL criterion of £20 minutes) as compared with SC subjects (P < 0Æ02) Major improvement indicators

• SOL

MF: 77Æ3 fi 17Æ5 minutes SC: 74Æ9 fi 28 minutes

Follow up 1 month (n ¼ 18)

A significantly greater number of MF subjects achieved a good sleeper status. Six out of nine MF subjects and two out of nine SC subjects exhibited SOL of £20 minutes at follow-up (P < 0Æ05) Hauri (1997) • Structured interview • Sleep diary

• Stanford sleepiness scale • polysomnography (PSG) • medical history review

• PSG • wrist actigraphy • sleep diary • subjective sleep quality ratings, ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (good)

Both sleep hygiene alone and combined therapy resulted in significant improvements on SE (P < 0Æ03) and subjective sleep quality as compared with the waiting-list control group (P < 0Æ03)

Major improvement indicators • Subjective sleep quality

Sleep hygiene alone: 3Æ4 fi 3Æ2 combined therapy: 3Æ1 fi 3Æ5 WL: 3Æ0 fi 3Æ1

• SE

sleep hygiene alone: 77Æ8% fi 83Æ7% combined therapy: 82Æ0% fi 85Æ7% WL: 81Æ2% fi 80Æ7%

Follow up

10 months (n ¼ 21) Participants treated with

sleep hygiene alone had a higher SE and TST than those who were treated with sleep hygiene plus medications (P < 0Æ05) Mimeault and Morin (1999) • Structured interview • Pittsburgh Sleep

Quality Index (PSQI) • Seep Impairment Index (SII) • Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) • Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) • medical history questionnaire • Sleep diary • SII • Treatment Evaluation Questionnaire (TEQ) • PSQI

• The Beliefs and Attitudes About Sleep Scale (BAS) • BDI

• BAI

CBT & BTPC improved significantly from pre- to post-treatment on all measures especially on TWT & SE, whereas the WL condition did not (P < 0Æ01)

There were no significant differences between CBT & BTPC groups Major improvement indicators • SE CBT: 66Æ0% fi 76Æ62% BTPC: 69Æ4% fi 83Æ92% WL: 69Æ8% fi 69Æ9% • TST CBT: 328Æ11 fi 361Æ42 minutes BTPC: 344Æ03 fi 379Æ14 minutes WL: 349Æ07 fi 347Æ63 minutes • TWT CBT: 169Æ72 fi 108Æ08 minutes BTPC: 155Æ15 fi 72Æ73 minutes WL: 154Æ96 fi 151Æ68 minutes • CBT & BTPC had a significantly

greater improvement on scores of the SII, BAS & BDI • Use of sleep aids in treatment

groups reduced from 35% of nights per week to <26%.

Follow up 3 months (n ¼ 29) Measures of SE, TST and

TWT remained unchanged as compared those measured immediately post-treatment; both CBT and BTPC treatment groups were comparable at 3-month follow-up Use of sleep aids in treatment

groups reduced to <20% at 3-month follow-up

Table 2 (Continued)

Study Screening tests

Measurement

instruments Results Long-term effects

Edinger et al. (2001) • Structured interview • Sleep log • Medical examination • PSG • PSG • Sleep log • Insomnia Symptom Questionnaire (ISQ) • Self Efficacy Scale

(SES) • BDI • TEQ

CBT recipients reported a 54% reduction in WASO whereas RT and PT reported only 16% and 12% reduction, respectively (P < 0Æ01) 59Æ1% of CBT, 29Æ2% of RT and

4Æ8% of PT subjects achieved the normal ISQ score on study completion (P < 0Æ01) Major improvement indicators: • TST CBT: 352Æ1 fi 372Æ4 minutes RT: 352Æ1 fi 337Æ9 minutes PT: 352Æ1 fi 334Æ0 minutes • SE CBT: 77Æ8% fi 85Æ5% RT: 77Æ8% fi 78Æ1% PT: 77Æ8% fi 75Æ7% • WASO CBT: 50Æ8 fi 30Æ1 minute RT: 50Æ8 fi 50Æ6 minutes PT: 50Æ8 fi 66Æ4 minutes Follow up 6 months (n ¼ 46) CBT group produced an average

WASO of 26Æ6 minutes and SE of 85Æ1% compared with WASO of 43Æ3 minutes and SE of 78Æ8% in RT (P ¼ 0Æ02). Espie et al. (2001) • PSQI • Epworth sleepiness scale • PSG • PSQI • sleep diary • wrist actigraphy • PSG • State-Trait Anxiety Inventory • Penn Worry Questionnaire • BDI

CBT significantly improved sleep patterns and sleep quality

as compared with SMC (P < 0Æ05) Major improvement indicators • WASO CBT: 31 fi 47 minutes SMC: remained ‡80 minutes • SOL CBT: 61 fi 28 minutes SMC: 74 fi 70 minutes • CBT produced significant

reductions in trait anxiety and worry (P < 0Æ05) • 76% of patients who initially

used hypnotic medication had stopped completely at post-treatment

Follow up 12 months (n ¼ 109) CBT was associated with a sustained

mean reduction by 50% in SOL, reduction by 36% in WASO and an increase of 10% in TST 84% of subjects available at

12-month follow up no longer required hypnotics Morin et al. (2002) • Structured interview • Physical examination • Dysfunctional Attitudes

and Beliefs About Sleep (DABAS)

• Sleep diary • PSG • DBAS

There were 78%, 56%, 75% and 14% of the participants in CBT, PCT, COMB and PLA, respectively, researched a clinically meaningful outcome

CBT and COMB provided greater improvements in DBAS scores than did PCT and placebo (P < 0Æ05) Reductions of DBAS scores were

positively related to the increase in SE (P < 0Æ05)

Major improvement indicators • SE CBT: 68% fi 85% PCT: 72% fi 83% COMB: 64% fi 85% PLA: 69% fi 74% Follow up: 3(n ¼ 56), 12(n ¼ 52) and 24(n ¼ 46) months More adaptive DBAS scores were

significantly correlated with SE at each of the three follow-up assessments

CBT, PCT and COMB endorsed less dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep than the PLA group (P < 0Æ05)

There was no significant difference among CBT, PCT and COMB

Assessment of participants

The ICSD-R and the DSM-IV were the main diagnostic criteria in studies reviewed and as the guidance for conducting structured interviews. In addition to structured interviews and self-report measurement of insomnia symp-toms, only three studies used polysomnography (PSG) to confirm the diagnosis (Hauri 1997, Espie et al. 2001, Morin et al. 2002). Espie et al. (2001) used Epworth’s Sleepiness Scale to rule out the possibility of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and periodic limb movements on sleep. A score of more than 5 on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to identify significant sleep disturbance in two studies (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Espie et al. 2001). Furthermore, only two studies measured the pretreatment mood states of participants and excluded the psychiatric pathology (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Espie et al. 2001). Two used laboratory tests to screen participants (Edinger et al. 2001, Morin et al. 2002).

Outcome measurements

The major outcome variables for CBT were SOL, WASO, sleep efficiency (SE), total sleep time (TST), total wake time

(TWT), and general sleep quality. Reduction in the use of hypnotics was also assessed in two studies (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Espie et al. 2001). All studies used daily sleep diaries to assess outcome. Four studies used PSG to validate the results obtained from sleep diaries (Hauri 1997, Edinger et al. 2001, Espie et al. 2001, Morin et al. 2002). Other established questionnaires about general sleep disturbance, such as the PSQI (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Espie et al. 2001), Insomnia Symptom Questionnaire (ISQ) (Edinger et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003) and Sleep Impairment Index (SII) (Mimeault & Morin 1999), were also used for assessment. The Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes About Sleep Scale (DBAS) was adopted in two studies to assess sleep-related beliefs (Morin et al. 2002, Edinger & Sampson 2003). Instruments such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Penn Worry Questionnaire (PWQ) were used to measure change in mood states (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Espie et al. 2001). In addition, three studies used the Treatment Evaluation Questionnaire (TEQ) to measure participants’ perceptions of the insomnia treatment received (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Edinger et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003).

Table 2 (Continued)

Study Screening tests

Measurement

instruments Results Long-term effects

Edinger and Sampson (2003) • Structured interview • Chart review • Sleep logs • ISQ • SES • DBAS • TEQ

90% of the ACBT group showed an increase in SE and 30% of the SHR group did so (P ¼ 0Æ02) 60% of the ACBT and none of the

SHR patients achieved the criterion for clinically significant WASO improvement (P ¼ 0Æ011) ACBT appeared superior to SHR in

normalizing ISQ scores (P < 0Æ005) and DBAS scores (P < 0Æ005) Major improvement indicators • WASO ACBT: 54Æ2 fi 46Æ6 minutes SHR: 97Æ2 fi 98Æ5 minutes • SE ACBT: 71Æ4% fi 80Æ0% SHR: 71Æ4% fi 72Æ3%

• ACBT reported a greater sense of sleep-related self-efficacy

Follow up 3 months (n ¼ 7)

ACBT-treated patients averaged a 52% reduction in WASO from study entry to the 3-month follow-up time point

55Æ6% of the ACBT and none of the SHR patients showed normal ISQ scores by the 3-month follow-up (P ¼ 0Æ02).

MF, multifactor behavioural intervention; SC, stimulus control; WL, waiting-list control; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; BTPC, biblio-therapy and phone consultations; RT, relaxation training; PT, placebo biblio-therapy quasi-desensitization group; SMC, self-monitoring control; PCT, pharmacotherapy; COMB, CBT & PCT; PLA, placebo medication; ACBT, abbreviated cognitive behavioural treatment; SHR, sleep hygiene recommendations; SOL, sleep onset latency; SE, sleep efficiency; TST, total sleep time; TWT, total wake time; WASO, wake time after sleep onset.

Clinical significance of changes in sleep parameters

The efficacy of multifaceted CBT programmes was examined in comparison with a control group (i.e. placebo treatment or waiting-list group), single component treatment group (i.e. stimulus control, relaxation training, or educational pro-gramme), or pharmacological treatment group. The studies demonstrated that CBT produced statistically significant changes compared with the control conditions. Hauri (1997) found that both active treatment conditions resulted in significant improvements in SE (P < 0Æ03) and subjective sleep quality (P < 0Æ03) compared with the control group. SE was improved to 85Æ1% in the treatment groups compared with 80Æ7% in the waiting-list group. Mimeault and Morin (1999) found that both CBT-treated groups produced signi-ficant sleep improvements as compared with the waiting-list control group. SE increased to 76Æ6% in CBT participants, but was 69Æ9% in the waiting-list control group (P < 0Æ01). Total sleep time increased from 328 to 361 minutes in CBT participants, but remained far <6 hours in the waiting-list group (P < 0Æ01). Espie et al. (2001) also found that mean SOL reduced from 61 to 28 minutes (P < 0Æ01) following CBT compared with a change from 74 to 70 minutes in the self-monitoring group. Moreover, Edinger et al. (2001) reported the superiority of CBT over other treatment groups. The duration of WASO was 50Æ6 minutes and SE was 78Æ1% in the relaxation training-treated patients, whereas CBT-treated patients achieved 30Æ1 minutes of WASO and 85Æ5% of SE (P < 0Æ01). Jacobs et al. (1993) also found that, although two behaviourally-treated groups had significant improvements in SOL, only those in the multifactor beha-vioural intervention group achieved a mean post-test sleep latency within the range defining good sleepers (<20 minutes). The multifactor behavioural intervention group had a 77% improvement on mean SOL compared with the stimulus control group (63%). Edinger and Sampson (2003) showed that abbreviated cognitive behavioural insomnia therapy (ACBT) reduced WASO to 46Æ6 minutes, compared with 98Æ5 minutes in the sleep hygiene education group. In addition, ACBT appeared superior to the sleep

hygiene education group in normalizing ISQ scores

(P < 0Æ005) and DBAS scores (P < 0Æ005). Morin et al. (2002) also found that CBT and CBT combined with pharmacotherapy produced significant improvements in DBAS compared with pharmacotherapy alone. Interestingly, there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes between CBT and CBT combined with pharmacotherapy.

Overall, improvement of WASO and SE were the most

frequently-reported beneficial outcomes. Three studies

showed that CBT resulted in an average of 50 % reduction

in WASO as compared with the pretest baseline; mean post-test awakening time was <55 minutes. Although the results still fall outside the optimal range (<30 minutes), post hoc comparisons revealed that the reduction in WASO was statistically significantly greater (P < 0Æ05) for CBT than the control condition (Edinger et al. 2001, Espie et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003).

The other important marker of clinical improvement is SE. An SE of <80% is the cutoff point for distinguishing insomniac patients from good sleepers (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Verbeek et al. 1999, Espie et al. 2001). Five studies showed a statistically significant improvement in SE of more than 80% (Hauri 1997, Mimeault & Morin 1999, Edinger et al. 2001, Morin et al. 2002, Edinger & Sampson 2003).

Other sleep parameters were also reported. A SOL below 30 minutes is considered normal (Morin 2003). Reduction in SOL was also documented in the studies reviewed. Jacobs et al. (1993) found that both multifactorial behavioural intervention and stimulus control effectively decreased SOL to <30 minutes. Edinger and Sampson (2003) found that 37Æ5% of CBT participants achieved the criterion for clinic-ally significant SOL improvement. Espie et al. (2001) also showed that SOL was statistically significantly reduced to 28 minutes at post-treatment measurement. Assessment of global insomnia symptoms such as the ISQ scores, which evaluates global insomnia symptoms, achieved a normal level in the CBT group; the ISQ scores of the CBT group were statistically significantly different from those of the relaxa-tion-training group and placebo therapy group (P ¼ 0Æ045) on study completion (Edinger & Sampson 2003). CBT also produced statistically significantly greater changes in beliefs and attitudes about sleep compared with the control condition (Morin et al. 2002, Edinger & Sampson 2003).

Some studies showed that participants who were receiving hypnotics during the study statistically significantly reduced sleep medication use without producing statistically signifi-cant deterioration in sleep, anxiety, or depression measures from baseline. According to Espie et al. (2001), 76% of those who originally took hypnotic medication had stopped taking medication completely at post-treatment. One-year follow-up assessment even showed that 84% of those available at follow-up no longer required hypnotics. Mimeault and Morin (1999) also found that sleep-aid use was reduced from 35% to 41% of nights per week at pretreatment to 26% to 25% at post-treatment.

Long-term effects

The long-term effects of CBT were also examined in several studies and the results suggested that the treatment effect of

CBT was sustained overtime whereas that of pharmacother-apy was short-lived. Hauri (1997) found that insomniacs who learned sleep hygiene and relaxation techniques without concomitant use of hypnotics maintained the improvement over a 10-month follow-up period. Those treated with the behavioural approach alone had a higher SE (83%) than those treated with sleep hygiene in combination with phar-macotherapy (78Æ8%). TST in the behavioural approach group was also longer than 6 hours compared with

347Æ4 minutes in the combined intervention group

(P < 0Æ05). In the study by Mimeault and Morin (1999), the treatment effect of CBT was maintained for 3 months after the study period. There were no significant changes from immediately post-treatment to 3-month follow-up in SE and TST. In addition, sleep-aid use was further reduced to <20%. Similarly, Espie et al. (2001) found clinically significant changes in sleep after 6 weeks of CBT, and these improvements were sustained through 12 months of follow-up. Approximately two-thirds of patients (n ¼ 109) achieved and maintained a sleep latency of <30 minutes 1 year after completion of therapy, and a similar proportion achieved <30 minutes of wakefulness during the night. Morin et al. (2002) found that the sleep improvement in the medication-treated only group returned to near baseline at 3-month follow up, whereas CBT sustained its sleep improvements very well up to 24 months. Morin et al. (2002) demonstrated that more adaptive beliefs and attitudes were associated with better sleep maintenance, while Edinger and Sampson (2003) reported that 55Æ6% of their CBT group had normal ISQ scores by 3-month follow-up; this suggest that changes in cognitive behavioural patterns may produce durable insom-nia-improving effects even with a limited sample size.

Discussion

Assessment of participants

The methods for assessing the inclusion criteria varied widely across studies. In the assessment of sleep complaints, most of the studies used telephone screening and/or face-to-face interviews. As a result, a large number of potential partici-pants were excluded. Although subjective data alone are sufficient to make the diagnosis of primary insomnia accord-ing to DSM-IV/or ICD-10 criteria, the screenaccord-ing process would be more rigorous if followed by additional measures such as a sleep quality questionnaire, sleep logs and/or PSG. Only one study adopted screening instruments such as the BDI or BAI to rule out psychiatric disorders (Mimeault & Morin 1999). Moreover, although participants in the studies reviewed were tended to be in the older middle-aged group

and had had difficulty sleeping for more than 10 years, only two used rigorous physical examination for screening (Edin-ger et al. 2001, Morin et al. 2002). Other studies either used subjective medical-physical questionnaires or reviewed poten-tial participants’. Two did not describe the screening process for recruiting participants (Espie et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003). Therefore, the influence of emotional and physical status could not be ruled out and caution should be exercised when interpreting the outcomes.

CBT component

The efficacy of CBT programmes was examined in compar-ison with single-treatment groups such as a stimulus control, relaxation training, educational programme, or pharmacolo-gical treatment. According to the results, a multifaceted approach for CBT may enhance therapeutic efficacy. How-ever, several issues need to be considered. First, the components of CBT were different in the studies reviewed. All adopted behavioural techniques including stimulus control and the sleep hygiene education. However, relaxation training was only specifically integrated into the CBT protocol by two studies (Jacobs et al. 1993, Espie et al. 2001). In addition, one did not clearly define the format of the treatment (Hauri 1997). In Hauri’s (1997) study, one single treatment (i.e. sleep hygiene education) was assessed, although relaxation training and low-level cognitive inter-vention (i.e. time management) were also integrated into the treatment protocol. One study adopted an abbreviated format of CBT that included only sleep education and a behavioural regimen (Edinger & Sampson 2003). The inconsistency in treatment protocols among studies led to difficulties in comparing results across studies.

Secondly, improvement indicators were also different across the studies. Improvements in SE, WASO, TST and SOL were reported for protocols that included behavioural techniques, except for the study by Morin et al. (2002). As behavioural techniques such as stimulus control are used to teach insomniac patients to re-associate the bed and bedroom with sleep by curtailing sleep-incompatible activities, the cues for staying awake will be changed and a consistent sleep– wake schedule could be rebuilt. Therefore, sleep efficacy and night-time wakefulness might be improved. On the contrary, Espie et al. (2001) found that, in addition to the change in WASO, relaxation training decreased both SOL and hypnotic use. Relaxation is useful in insomnia patients, who often display high levels of arousal both at night and during the daytime. Unfortunately, the effect of relaxation was difficult to determine because the data about the changes in partici-pants’ emotional status were lacking.

Structured cognitive reconstruction was included in three studies but not those done by Jacobs et al. (1993), Hauri (1997) and Edinger et al. (2001), and the abbreviated format of CBT adopted by Edinger and Sampson (2003). Based on the conceptual model of persistent primary insomnia, the treatment components should include cognitive as well as the physiological aspects. The addition of cognitive restructuring procedures that target perpetuating factors with behavioural instructions could enhance treatment efficacy and increase participants’ control over sleep. Morin et al. (2002) found that the better the adaptive beliefs and attitudes about sleep (lower DBAS scores), the better the sleep efficacy (SE). Themes such as ‘control and predictability of sleep’, ‘causal attributions of insomnia’, ‘consequences of insomnia’ and ‘sleep expectations’ were significantly correlated with im-proved SE at post-treatment assessments. Other studies that included a cognitive regimen also reported improvements in WASO, TST and medication use. Interestingly, the abbrevi-ated CBT format which included behavioural techniques and sleep hygiene education also resulted in improvements in SE, WASO and even DBAS scores. Therefore, the critical treatment ingredients in cognitive aspects need to be further investigated. After all, the value of CBT lies in the fact that it not only leads to subjective improvement of symptoms, but also increases the patient’s control over the previous sleep problem.

It is also noteworthy that there was no significant difference between CBT and CBT combined with pharmac-otherapy (Morin et al. 2002). Both treatment groups endorsed fewer dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep than those who had pharmacotherapy alone. It might be argued that medication could help alleviate the symp-toms of insomnia and the changes in beliefs and behaviours were not produced by CBT, but rather represented the sleep improvements with sleeping-aids. However, the improved sleep pattern in itself may not have been sufficient to produce statistically significant changes in beliefs and attitudes. CBT could be useful in breaking the vicious cycle of insomnia that leads to sleep disturbances, and also to reduce the risk of self-medication. Hauri (1997) also speculated that patients without hypnotics might have learned the behavioural techniques better and were more committed in their pursuit of behavioural relief, thereby producing considerable long-term influence on sleep in insomniacs.

Ideally, each treatment ingredient should be specifically connected to causes among different subgroups of insomnia. However, only two studies classified participants into three insomnia subgroups: difficulty in initiating sleep, difficulty in maintaining sleep and mixed type. Unfortunately, these

studies failed to investigate the relationship between different treatment components and the three subtypes of primary insomnia (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Morin et al. 2002). For future studies, it is important to characterize the subtype of insomnia in order to identify appropriate aetiology-based interventions and to examine their relative efficacy and clinical utility.

Therapist effect

The qualification of the therapist was not clearly explained in most studies. Psychologists were the conductors of CBT in most of the studies, and only one tested a nurse-led model of the CBT. Three studies used the TEQ to measure treatment credibility across groups at post-treatment, and the findings suggested that the therapist effect was controlled in general (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Edinger et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003). However, the expertise of the therapist might be the most controversial point concerning the efficacy of the CBT for insomnia. It has been found that treatment delivered by a trained therapist produced higher improve-ment rates for WASO than that delivered by a trainee (Morin et al. 1994). The study that investigated the efficacy of nurse-led CBT format also showed the greatest improvement in WASO. Espie et al. (2001) demonstrated that nurses were able to produce significant changes in PSG-verified insomnia symptomatology, suggesting that with adequate training most nurses should be capable of delivering CBT to patients with primary or psychological insomnia. The treatment package itself comprised transferable skills that can be learned by nurses with no prior expertise. Nevertheless, future studies should compare the efficacy of CBT led by primary care providers with different educational and professional preparations as therapists.

The efficacy of self-help materials such as pamphlets and audio-cassettes were supported by three studies (Mimeault & Morin 1999, Edinger et al. 2001, Edinger & Sampson 2003). The effectiveness of professional guidance was also examined by Mimeault and Morin (1999). In that study, participants who received bibliotherapy supplemented with a weekly 15-minute professional phone consultation had higher SE and TST during the initial treatment phase than those who had bibliotherapy alone. This suggests that the addition of phone consultation may enhance compliance with CBT components such as strategies to avoid time spent in bed. However, the groups with and without a professional phone consultation were comparable in terms of sleep improvements at 3-month follow up. It might be that once individuals have internalized the therapeutic changes, guidance may no longer be the critical factor of treatment.

Conclusion

The review demonstrated that CBT alone produced statisti-cally significant changes in sleep parameters for participants with persistent primary insomnia, and CBT was superior to single component treatment such as relaxation training, educational programmes, pharmacotherapy, and other pla-cebo treatments. Most nurses should be capable of delivering CBT to patients with primary insomnia.

To reach a definitive conclusion about the efficacy of CBT for primary insomnia, there are several recommendations for future research.

• Participants’ emotional and physical states need to be carefully assessed to avoid the influence of non-specific effects.

• The subtype of insomnia experienced by participants needs to be identified and the relationship between treatment ingredients and different subtypes examined. It should then be possible to determine the critical treatment ingredients and identify efficacious aetiology-based interventions. • A comparison of the efficacy of CBT programmes led by

primary care providers with different educational and professional preparations as therapists should be done.

• Prospective studies are needed to identify patient charac-teristics that predict satisfactory outcomes from self-help treatments.

• The issue of treatment adherence needs to be explored. Ideally insomnia patients should be able to assimilate easily, adapt and feel comfortable in practising the tech-niques they have learned on a regular basis at home. Alternatives such as bibliotherapy and educational audio-tapes may be more readily accessible and effective inter-ventions.

Author contributions

MW and PT conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. MW and SW collected the data. MW, PT and SW analysed the data. PT and SW critically revised the manuscript. SW provided administrative, technical or mate-rial support and PT supervised the study.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, pp. 551–607.

American Sleep Disorders Association (1997) The Interventional Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised. American Sleep Disor-ders Association, Rochester, MN, USA.

Ancoli-Israel S. & Roth T. (1999) Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Sur-vey. I. Sleep 22, S347–S353.

Chesson A.L., Anderson W.M. Jr, Littner M., Davila D., Hartse K., Johnson S., Wise M. & Rafecas J. (1999) Practice parameters for the non-pharmacological treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep 22, 1128–1133.

Edinger J.D. & Sampson W.S. (2003) A primary care ‘friendly’ cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep 26, 177–182. Edinger J.D., Wohlgemuth W.K., Radtke R.A., Marsh G.R. &

Quilian R.E. (2001) Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association 285, 1856– 1864.

Espie C.A., Inglis S.J., Tessier S. & Harvey L. (2001) The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic insomnia: implementation and evaluation of a sleep clinic in general medical practice. Behaviour Research & Therapy 39, 45–60.

Hajak G., Bandelow B., Zulley J. & Pitttrw D. (2002) ‘As needed’ pharmacotherapy combined with stimulus control treatment in chronic insomnia-assessment of a novel intervention strategy in a primary care setting. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 14, 1–7. Hauri P.J. (1997) Can we mix behavioral therapy with hypnotics

when treating insomniacs? Sleep 20, 1111–1118.

Jacobs G.D., Rosenberg P.A., Friedman R., Matheson J., Peavy G.M., Domar A.D. & Benson H. (1993) Multifactor behavioral

What is already known about this topic

• Cognitive behavioural therapy can be useful incor-recting both mental states and behavioural practices that perpetuate insomnia.

• Cognitive behavioural therapy is underused by health care professionals but, given the cost, side effects and temporary benefits of pharmacological interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy deserves consideration in treating persistent insomnia.

What this paper adds

• A multifaceted approach for cognitive behavioural

therapy may be more effective than one that focuses on a single component.

• To reach a definitive conclusion about the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy for primary insomnia, clearly defined standard components of the therapy and a comprehensive assessment of patients are essential in future studies.

• With regard to ease of assimilation and accessibility, alternative formats for delivering cognitive behavioural therapy might be developed to suit a variety of primary care settings.

treatment of chronic sleep-onset insomnia using stimulus control and relaxation response. A preliminary study. Behavior Modifica-tion 17, 498–509.

Jadad A.R., Moore R.A., Carroll D., Jenkinson C., Reynolds D.J., Gavaghan D.J. & McQuay H.J. (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary. Con-trolled Clinical Trials 17, 1–12.

Kim K., Uchiyama M., Okawa M., Liu X. & Ogihara R. (2000) An epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population. Sleep 23, 41–47.

Leger D., Guilleminault C., Dreyfus J.P., Delahaye C. & Paillard M. (2000) Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. Journal of Sleep Research 9, 35–42.

Martin J.L. & Ancoli-Israel S. (2002) Assessment and diagnosis of insomnia in non-pharmacological intervention studies. Sleep Medicine Review 6, 379–406.

Mimeault V. & Morin C.M. (1999) Self-help treatment for insomnia: bibliotherapy with and without professional guidance. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology 67, 511–519.

Morin C.M. (2003) Measuring outcomes in randomized clinical trials of insomnia treatments. Sleep Medicine Reviews 7, 263–279. Morin C.M., Culbert J.P. & Schwartz S.M. (1994)

Nonphar-macological interventions for insomnia: a meta-analysis of treat-ment efficacy. American Journal of Psychiatry 151, 1172–1180. Morin C.M., Hauri P.J., Espie C.A., Spielman A.J., Buysse D.J. &

Bootzin R.R. (1999) Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep 22, 1134–1156.

Morin C.M., Blais F. & Savard J. (2002) Are change in beliefs and attitudes about sleep related to sleep improvements in the treat-ment of insomnia? Behaviour Research & Therapy 40, 741–752.

Ohayon M.M. & Hong S.C. (2002) Prevalence of insomnia and as-sociated factors in South Korea. Journal of Psychosomatic Re-search 53, 593–600.

Ohayon M.M. & Partinen M. (2002) Insomnia and global sleep dissatisfaction in Finland. Journal of Sleep Research 11, 339– 346.

Perlis M.L., Giles D.E., Mendelson W.B., Bootzin R.R. & Wyatt J.K. (1997) Psychophysiological insomnia: the behavioral model and a neurocognitive perspective. Journal of Sleep Research 6, 179– 188.

Perlis M.L., Sharpe M., Smith M.T., Greenblatt D. & Giles D. (2001) Behavioral treatment of insomnia: treatment outcome and the relevance of medical and psychiatric morbidity. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 24, 281–296.

Riedel B., Lichstein K., Peterson B.A., Epperson M.T., Means M.K. & Aguillard R.N. (1998) A comparison of the efficacy of stimulus control for medicated and non-medicated insomniacs. Behavior Modification 22, 3–28.

Smith M.T., Perlis M.L., Park A., Smith M.S., Pennington J., Giles D.E. & Buysse D.J. (2002) Comparative meta-analysis of phar-macotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159, 5–11.

Verbeek I., Schreuder K. & Declerck G. (1999) Evaluation of short-term non-pharmacological treatment of insomnia in a clinical set-ting. Journal of psychosomatic Research 47, S369–S383. Walsh J.K. & Engelhardt C.L. (1999) The direct economic costs of

insomnia in the US for 1995. Sleep 22, 386–393.

World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Diagnostic Criteria for Research (10th reversion). World Health Organization, Geneva.