Re: ID CDOE-10-287 revision 1 (Marked in color)

Title: The risk of temporomandibular disorder in patients with depression: A population-based cohort study

Chun-Hui Liaoa; Chen-Shu Changb; Shih-Ni Changc,d,e; Hsien-Yuan Lanea,f, Shu-Yu Lyug, Donald E. Morisky h, Fung-Chang Sungd,i,*

a Department of Psychiatry, China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung 404, Taiwan

b Department of Neurology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua City 500, Taiwan

c The Ph.D. Program for Cancer Biology and Drug Discovery, and d Management Office for Health Data,China Medical University, Taichung 404, Taiwan

e Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan

f Institute of Clinical Medical Science, China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung 404, Taiwan

g School of Public Health, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 110, Taiwan

hDepartment of Community Health Sciences,UCLA School of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772

i Department of Public Health, China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung 404, Taiwan

Running title: Depression and temporomandibular disorder

*Correspondence author:

Fung-Chang Sung, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Professor

China Medical University and Hospital College of Public Health 91 Hsueh-Shih Road

Taichung 404, Taiwan

Telephone: 886-4-2206-2295 Fax: 886-4-2201-9901

Email: fcsung1008@yahoo.com

Word count: 173 in Abstract; 2335 in the text; 4 tables; 33 references.

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study used a population-based retrospective cohort design to examine

whether depression is a risk factor of temporomandibular disorder (TMD). Methods:

From a universal insurance database, we identified 7,587 patients newly diagnosed

individuals with depression in 2000 and 2001. A total of 30,197 comparison subjects

were randomly selected from a non-depression cohort. Both groups were followed

until the end of 2008 to measure the incidence of TMD. Results: The incidence of

TMD was 2.65 times higher in the depression cohort than in the non-depression

cohort (6.16 vs. 2.32 per 1,000 person-years). The multivariate Cox proportional

hazard regression analysis measured hazard ratio (HR) of TMD for the depression

cohort was 2.21 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.83 - 2.66), after controlling for

sociodemographic factors and other psychiatric co-morbidities. Females had higher

risk to develop TMD than males (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.36 - 1.92 for females without

depression; HR 3.54, 95% CI 2.81- 4.45 for females with depression). Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that patients with depression are at an elevated risk of

developing TMD.

Key word: depression; hazard ratio; population-based study; retrospective cohort

design; temporomandibular disorder

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are quite common among the general

population, with a life-time prevalence of up to 93% in an epidemiological study (1).

These disorders include complaints of the temporomandibular system, consisting of

the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and the associated neuromuscular system (2). A

national survey among Dutch adults showed that 21.5% of the adult population had

temporomandibular dysfunction but only 15% of those sought treatment (3). Most

patients seek treatment because of TMD pain (4), in the temporomandibular region or

involving the eyes, face, shoulder, neck, back and head (5, 6). Patients with TMD

have a decreased quality of life due to orofacial pain, particularly for patients with

severe TMD (7). The etiology of TMD has been regarded as multifactorial. Dworkin

and Leresche (8) designed a two-axis diagnostic scheme to evaluate the patient’s

condition. The psychological variables were assessed with Axis II, emphasizing the

relevant factors of TMD. Gracely (9) reported that individuals can have different

levels of pain perception, which can be influenced by emotional factors. Hotopf et al.

have noted the psychiatric disorder may promote 40% cases of multiple symptoms

including arthritis, rheumatism and headache (10). Magni et al. found in a prospective

study that the relationship between depressive systems and chronic musculoskeletal pain may operate in both directions (11).

Depressive symptoms are significantly related to the severity of pain in the TMD

patients (12). Moreover, TMD pain and depression are often coexistent (13-15).

Macfarlane et al. found in a case-control study that patients with pain dysfunction syndrome had high levels of psychological distress (15). Depression has now become

a global burden disorder and the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide (16).

Major depressive disorder presents in 5% to 10% of patients seeking primary care

(17). The prevalence of depression may well be higher among the general population

because some people may have depressive disorders which do not fully meet the

diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder of the American Psychiatric

Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Among studies on the relationship between depressive systems and pain, there is

a convergent association between depression and TMD pain, especially in the chronic

pain group (2). Several studies on the relationship between depression and TMD have

evaluated the mood condition among TMD patients (13-18). However, those studies

were unable to answer whether depression is a source or consequence of TMD pain

because of case-control and cross-sectional designs.

Slade et al. have recently conducted a prospective cohort study of 238 healthy female volunteers aged 18-34 years investigating the psychological influence on the

risk of TMD. They found that depression, perceived stress, and mood are associated

with pain sensitivity with a 2- to 3-fold increase in the risk of TMD (P < 0.05) (19).

But, this study was limited to a small sample size with only one gender and a short follow-up period. We therefore designed a population-based cohort study with higher statistical power to detect the development of TMD among the depressive patients.

Not all patients with TMD complaints visit the dentists. We hypothesized that patients

with depressive disorder would have a higher risk of TMD complaints, leading to a

greater likelihood to seek dental services than the general population. To gain a better understanding of the relationship between depression and TMD, we conducted a

population-based retrospective cohort study using claims data from the universal

insurance program. The incidences of dentist-diagnosed TMD were compared

between patients with depression and without depression.

Materials and methods

Data resources

This study used the reimbursement claims data of The National Health Insurance

program of Taiwan that reformed in March 1995 from 13 insurance systems. The

insurance program has covered more than 96% of the 23 million population and

contracted with more than 90% of hospitals and clinics in Taiwan since 1996 (20, 21).

The Department of Health National Health Research Institute (NHIR) managed all

medical claims data reported from the contracted health care facilities. With approval

from NHRI, we were able to use a representative sub-datasets of one million insured

persons randomly selected from all beneficiaries enrolled in the insurance program

(21). This data set consisted of the registry of medical facilities, details of inpatient

orders, ambulatory care, dental services and prescriptions linked with scrambled

patient identification. Because all patient identifications were surrogated, this study

was conducted with patients privacy secured and with a waiver from the institutional

review board.

Study sample

We used the coding of the International Classification of Disease Diagnoses, Ninth

Revision of Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to identify 7,587 patients with depression (ICD-9-CM 296.2, 296.3, 300.4 and 311) newly diagnosed in 2000 and

2001 as the study cohort. In order to ensure the validity of the diagnosis, only new

patients with at least three visits for depression care during the follow-up period after

the index date were eligible for inclusion. For each case with depression identified, we

used simple random sampling methods to select 4 persons without depression in the

same period for the comparison cohort (N = 30,348). We excluded 102 subjects from

the depressive cohort and 151 subjects from the comparison cohort. They were

excluded because of a history of TMD diagnosis by the baseline index date (defined

as the date the subject identified and selected) or missing information on age or sex.

Our final sample includes 7,485 subjects in the depression cohort and 30,197 subjects

in the non-depression cohort.

Socio-demographic variables and co-morbidities

The socio-demographic variables, including sex, age, occupation, employment

category, residential area and monthly income, were available. The age of each study

subject was measured by the difference between the index date and the date of birth.

Using the National Statistics of Regional Standard Classification (22), we grouped all

study subjects into four geographic areas (North, Central, South, and East and off

Islands) and three urbanization levels (low, medium and high).

We considered anxiety state (ICD-9-CM 300.00), panic disorder (ICD-9-CM 300.01), generalized anxiety disorder (ICD-9-CM 300.02), obsessive-compulsive

disorders (ICD-9-CM 300.03) and psychiatric diseases (ICD-9-CM 290-319; except

the main effect in this study – depression) as other psychiatric co-morbidities.

Study end-point

We linked study subjects to the inpatient and outpatient claims data of dental clinics to

identify the newly diagnosed cases of TMD (ICD-9-CM 524.6) as the outcome of the

study, using the scrambled patient identification number. We calculated person-years

for each study subject until TMD was diagnosed, or until December 31, 2008 for

those uncensored, or the censoring date because of death, emigration, termination of

insurance, or loss to follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the distributions of categorical socio-demographic variables and

co-morbidities between depression patients and non-depression patients using the

Chi-square test. We also calculated the incidence density with person-years for these

variables in the study cohort and comparison cohort. The rate ratio of TMD was

calculated by each variable.

Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis was used to assess the risk of

TMD associated with depression, adjusting for variables that were significantly related to depression from the prior Chi-square analyses. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95%

confidence interval (CI) were calculated in the model. The sex and age stratification

analyses for the risk of TMD in association with depression were also examined using

Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis.

All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (version 9.1 for

Windows; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Significance level was set to 0.05.

Results

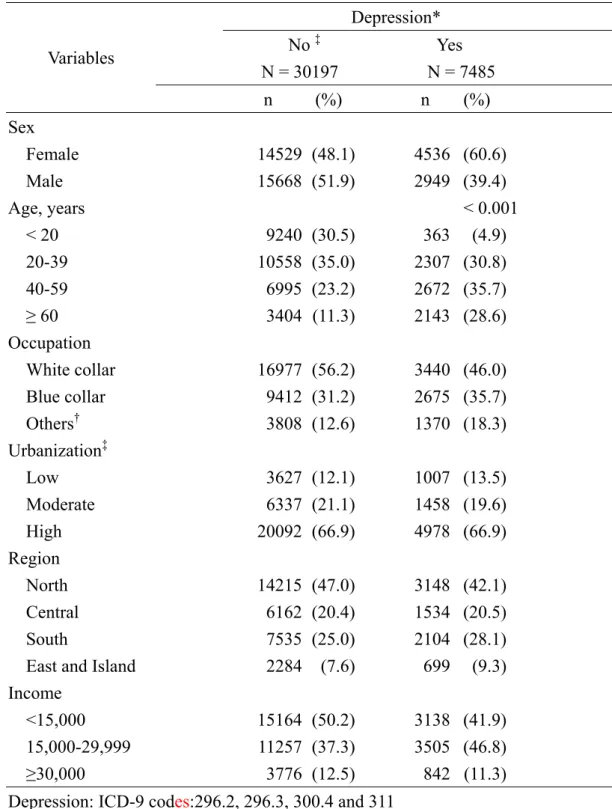

Table 1 compares socio-demographic characteristics between the depression cohort

and the non-depression comparison cohort. There were more females in the

depression cohort than in the comparison cohort (60.6% vs. 48.1%). The depression

cohort was also older, less white collar employment and had middle income.

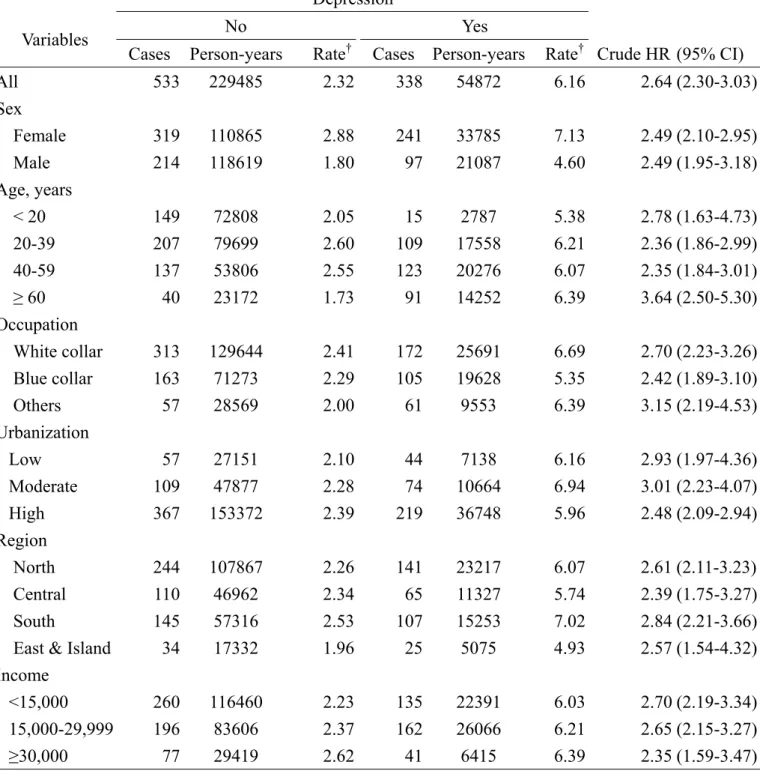

Table 2 presents the incidence and crude hazard ratios of TMD by

socio-demographic status. The overall incidence rate of TMD in the depression cohort

was 2.65 times higher than that in the comparison cohort (6.16 vs. 2.32 per 1,000

person-years). The crude hazard ratios measured by categorized socio-demographic

status ranged from 2.35 to 3.64, with the depression cohort of those more than 60

years of age having the highest hazard ratio. Older men in the non-depression cohort

had the lowest risk of having TMD.

The multivariate Cox proportional regression analysis showed that the risk of

TMD was significantly greater in the depression cohort than in the non- depression

cohort (HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.83 - 2.66) after controlling for covariates (Table 3).

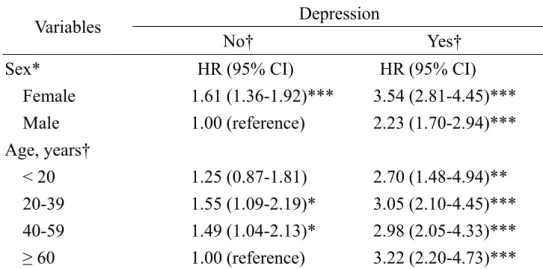

Table 4 shows that females were at greater HRs to develop TMD than males.

Compared with males without depression, females without depression had a HR of 1.61 (95% CI 1.36 - 1.92) and females with depression had the HR increased to 3.54

(95% CI 2.81 - 4.45). Compared with the non-depression cohort ≧ 60 years of age,

the HRs of TMD increased in patients with depression, and in particular, the highest

risk was noted in depression patients ≧ 60 years of age (HR 3.22, 95% CI 2.20 –

4.73).

Discussion

Studies investigating whether the risk of TMD is higher in patients with depression using cohort designs are limited. Our study aimed to explore whether depression is a

risk factor related to subsequent TMD problems. We measured the incidence of

dentist-diagnosed TMD in depressive patients compared with that of a non-depression

cohort, using a population-based retrospective cohort study design. This approach

overcomes the major limitation of cross-sectional and case-control study designs by

providing incidence information.

TMD disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with depression (13, 14, 23).

Previous studies on TMD and depression have been unclear as to whether depression

occurred prior to the onset of TMD or as a consequence of it. Slade et al. (19) found

that depression was one of the predicted risk factors of the first-onset of TMD among

healthy females with a small sample size. These studies collected information on

depression based on self-reported questionnaires, which is different from clinically

verified depressive disorder. Our population-based study on the association between

depression and subsequent TMD found that there is a 2.21 to 2.64-fold higher risk of a

diagnosis of TMD among patients with a physician diagnosed depressive disorder,

compared with the control group within an 8-year follow-up period, after adjusting for

demographic characteristics and comorbid anxiety disorders.

TMD are a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting temporomandibular joint,

the masticatory muscles, or both, and might present with joint sounds or severe

dysfunction. The most common symptom was pain and most patients sought help

because of it. TMD has also been a chronic pain condition in many cases (24). Not

only is depression prevalent among patients with chronic TMD-related pain

conditions, but patients with TMD and comorbid psychological factors had a poor

response to dental treatment alone (25). This could be explained by depression

possibly increasing pain-perception thresholds (26, 27) and affecting the expression of

TMD signs and symptoms (28). Therefore, depressive patients might have more TMD

problems, which lead them to seek dental services.

In our study, the incidence of TMD among the depression group was 4.5% in the

8-year follow-up, which is higher than the incidence in a previous study (3.1%) for a

Dutch adult population (3). This reflects a higher risk of TMD problems among the

depressive population. Our definition of TMD was based the information from

patients who had visited a dental clinics rather than from case-control study or general

cross-sectional survey among the general population. Therefore, in our study, the

difference in TMD incidences between the depressive patients and the general

population without depression is more valid. However, our diagnosis of depression

included both minor and major depressive disorders (ICD 296.2, ICD 296.3, ICD

300.4, and ICD 311), and may have identified subjects with a broader spectrum of

depressive disorders. It still is likely that depression is underestimated in the general

population, because not all patients seek help from physicians when depressed.

Our study was compatible with previous reports that found that females had a

higher rate of TMD than males (29-31). Elderly depressive patients are also found to

have a higher risk of TMD, which lead them to seek dental services. However, the

non-depressive elderly had the least risk of TMD. Further research to evaluate TMD

among geriatric patients is needed.

There are some limitations to interpret the results of our study. First of all, the

diagnoses of depression, TMD and comobidity relied on claims data, so there may be

missing information made under a standardized diagnostic process. Obtaining this

kind of information for a large population-based cohort study would be extremely

difficult. But our strength in this study was that working from a clinical diagnosis

made it possible to avoid the limitations of self-reported questionnaires. To increase

the diagnostic validity, all cases were diagnosed with depressive disorder at least three

times, which provided a reliable cohort assessment. Second, some studies found that a

myofascial type of TMD have a higher comorbidity of depression and required health

care more frequently (32, 33). But, we did not have the type and severity of TMD, and

the stress and mood status among our study cohort. We, therefore, could not further

evaluate the impact among them. Even though, we found a higher risk of developing

TMD among the depressive patients than the general population, which supports the

temporal relationship between depressive disorder and TMD. In addition, we could

not definitively identify the real onset time of depression from the database. However,

we still could hypothesis that life-time depression is one risk factor of TMD.

In conclusion, a temporal relationship between depression and TMD seems to

exist. These results imply that that dentists involved in the management of TMD need

to be aware of the co-morbidity of depression in these patients. Further research on

the clinical efficacy of decreasing dental services for TMD after the treatment of

depression is needed.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the National Sciences Council, Executive Yuan (grant

numbers NSC 99-2621-M-039-001), China Medical University Hospital (grant

number #DMR-99-119 and 1MS1) and the Taiwan Department of Health Clinical

Trial and Research Center for Excellence (grant number DOH100-TD-B-111-004 and

DOH100-TD-C-005). Liao CH and Chang CS contributed equally for this study.

References

1. Carlsson CR. Epidemiology and treatment need for temporomandibular disorders.

J Orofac Pain 1999;13:232-237.

2. Kafas P, Leeson R. Assessment of pain in temporomandibular disorders: the

bio-psychosocial complexity. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;35:145-149.

3. De Kanter RJ, Käyser AF, Battistuzzi PG, Truin GJ, Van t'Hof MA. Demand and

need for treatment of craniomandibular dysfunction in the Dutch adult

population. J Dent Res 1992;71:1607-1612.

4. Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Howard J, Truelove E, et

al. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders:

clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc 1990;120:273-281.

5. Pollmann L. Sounds produced by the mandibular joint in a sample of healthy

workers. J Orofac Pain 1993;7:359-361.

6. Kafas P, Chiotaki N, Stavrianos Ch, Stavrianou I. Temporomandibular joint pain:

diagnostic characteristics of chronicity. J Med Sci 2007;7:1088-1092.

7. Barros Vde M, Seraidarian PI, Côrtes MI, de Paula LV. The impact of orofacial

pain on the quality of life of patients with temporomandibular disorder. J Orofac

Pain 2009;23:28-37.

8. Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular

disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J

Craniomandib Disord 1992;6:302-355.

9. Gracely RH. Studies of pain in human subjects. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors.

Textbook of pain. 4th ed. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone, 1999; 385-408.

10. Hotopf M, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, Wessely S. Temporal relationships between

physical symptoms and psychiatric disorder. Results from a national birth cohort.

Br-J-Psychiatry. 1998; 173: 255-61

11. Magni G, Moreschi C, Rigatti-Luchini S, Merskey H. Prospective study on the

relationship between depressive symptoms and chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Pain 1994; 56: 289-297

12. Auerbach SM, Laskin DM, Frantsve LM, Orr T. Depression, pain, exposure to

stressful life events, and long-term outcomes in temporomandibular disorder

patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:628–633.

13. Korszun A, Hinderstein B, Wong M. Comorbidity of depression with chronic

facial pain and temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol Endod 1996;82:496–500.

14. Vimpari SS, Knuuttila ML, Sakki TK, Kivela SL. Depressive symptoms

associated with symptoms of the temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction

syndrome. Psychosom Med 1995;57:439–444.

15. Macfarlane TV, Gray R, Kincey J, Worthington HV. Factors associated with the

temporomandibular disorder, pain dysfunction syndrome (PDS): Manchester

case-control study. Oral Diseases 2001;7: 321-330.

16. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by

cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1498-1504.

17. Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp

Psychiatry 1992;14:237-247.

18. Macfarlane TV, Kincey J, Worthington HV. The association between

psychological factors and oro-facial pain: a community-based study. European

Journal of Pain 6: 427-434 (2002).

19. Slade GD, Diatchenko L, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Fillingim RB, Belfer I, et al.

Influence of psychological factors on risk of temporomandibular disorders. J

Dent Res 2007;86:1120-1125.

20. Lu JF, Hsiao WC. Does universal health insurance make health care unaffordable?

Lessons from Taiwan. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:77-88.

21. National Health Insurance Research Database, Taiwan.

http://www.nhri.org.tw/nhird/en/index.htm

22. Liu CY, Hung YT, Chuang YL, Chen YJ, Weng WS, Liu JS, Liang KY.

Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling

design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag.2006;14:1 –22.

23. Mongini F, Ciccone G, Ceccarelli M, Baldi I, Ferrero L. Muscle tenderness in

different types of facial pain and its relation to anxiety and depression: A

cross-sectional study on 649 patients. Pain 2007;131:106-111.

24. Dworkin SF, Massoth DL. Temporomandibular disorders and chronic pain:

disease or illness? J Prosthet Dent 1994;72:29-38.

25. Turner JA, Dworkin SF. Screening for psychosocial risk factors in patients with

chronic orofacial pain: recent advances. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:1119-1125.

26. Dickens C, McGowan L, Dale S. Impact of depression on experimental pain

perception: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom

Med 2003;65:369-375.

27. Lautenbacher S, Spernal J, Schreiber W, Krieg JC. Relationship between clinical

pain complaints and pain sensitivity in patients with depression and panic

disorder. Psychosom Med 1999;61:822-827.

28. Dworkin SF, Sherman J, Mancl L, Ohrbach R, LeResche L, Truelove E.

Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of the research diagnostic criteria for

Temporomandibular Disorders Axis II Scales: depression, non-specific physical

symptoms, and graded chronic pain. J Orofac Pain 2002;16:207-220.

29. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic

pain. Pain 1992;50:133-149.

30. Locker D, Leake JL, Hamilton M, Hicks T, Lee J, Main PA. The oral health

status of older adults in four Ontario communities. J Can Dent Assoc

1991;57:727-732.

31. Macfarlane TV, Blinkhorn AS, Davies RM, Kincey J, Worthington HV.

Oro-facial pain in the community: prevalence and associated impact. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002;30:52-60.

32. Lindroth J, Schmidt JE, Carlson CR. A comparison between masticatory muscle

pain patients and intracapsular pain patients on behavioral and psychosocial

domains. J Orofac Pain 2002;16:277–283.

33. Schmitter M, Kress B, Ohlmann B, Henningsen P, Rammelsberg P. Psychosocial

behaviour and health care utilization in patients suffering from

temporomandibular disorders diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings and

MRI examination. Eur J Pain 2005;9:243-250.

TABLES

Table 1. Comparisons in demographic characteristics between patients with and without depression at baseline in 2000-2001

Depression*

No ‡

N = 30197

Yes

N = 7485 Variables

n (%) n (%)

Sex

Female 14529 (48.1) 4536 (60.6)

Male 15668 (51.9) 2949 (39.4)

Age, years < 0.001

< 20 9240 (30.5) 363 (4.9)

20-39 10558 (35.0) 2307 (30.8)

40-59 6995 (23.2) 2672 (35.7)

≥ 60 3404 (11.3) 2143 (28.6)

Occupation

White collar 16977 (56.2) 3440 (46.0) Blue collar 9412 (31.2) 2675 (35.7)

Others† 3808 (12.6) 1370 (18.3)

Urbanization‡

Low 3627 (12.1) 1007 (13.5)

Moderate 6337 (21.1) 1458 (19.6)

High 20092 (66.9) 4978 (66.9)

Region

North 14215 (47.0) 3148 (42.1)

Central 6162 (20.4) 1534 (20.5)

South 7535 (25.0) 2104 (28.1)

East and Island 2284 (7.6) 699 (9.3)

Income

<15,000 15164 (50.2) 3138 (41.9)

15,000-29,999 11257 (37.3) 3505 (46.8)

≥30,000 3776 (12.5) 842 (11.3)

Depression: ICD-9 codes:296.2, 296.3, 300.4 and 311

*Chi-square test, all p-values are less than 0.001

† Unemployed: retired and low income

‡ Urbanization: low = 1st and 2nd lowest quartile of population density, moderate = 3rd quartile of population density, high = 4th highest quartile of population density

Table 2. Comparisons of incidence of temporomandibular disorder between cohorts with and without depression by sociodemographic factor

Depression No Yes Variables

Cases Person-years Rate† Cases Person-years Rate† Crude HR (95% CI)

All 533 229485 2.32 338 54872 6.16 2.64 (2.30-3.03)

Sex

Female 319 110865 2.88 241 33785 7.13 2.49 (2.10-2.95)

Male 214 118619 1.80 97 21087 4.60 2.49 (1.95-3.18)

Age, years

< 20 149 72808 2.05 15 2787 5.38 2.78 (1.63-4.73)

20-39 207 79699 2.60 109 17558 6.21 2.36 (1.86-2.99)

40-59 137 53806 2.55 123 20276 6.07 2.35 (1.84-3.01)

≥ 60 40 23172 1.73 91 14252 6.39 3.64 (2.50-5.30)

Occupation

White collar 313 129644 2.41 172 25691 6.69 2.70 (2.23-3.26) Blue collar 163 71273 2.29 105 19628 5.35 2.42 (1.89-3.10)

Others 57 28569 2.00 61 9553 6.39 3.15 (2.19-4.53)

Urbanization

Low 57 27151 2.10 44 7138 6.16 2.93 (1.97-4.36)

Moderate 109 47877 2.28 74 10664 6.94 3.01 (2.23-4.07)

High 367 153372 2.39 219 36748 5.96 2.48 (2.09-2.94)

Region

North 244 107867 2.26 141 23217 6.07 2.61 (2.11-3.23) Central 110 46962 2.34 65 11327 5.74 2.39 (1.75-3.27)

South 145 57316 2.53 107 15253 7.02 2.84 (2.21-3.66)

East & Island 34 17332 1.96 25 5075 4.93 2.57 (1.54-4.32) Income

<15,000 260 116460 2.23 135 22391 6.03 2.70 (2.19-3.34) 15,000-29,999 196 83606 2.37 162 26066 6.21 2.65 (2.15-3.27)

≥30,000 77 29419 2.62 41 6415 6.39 2.35 (1.59-3.47)

† per 1,000 person-years

Table 3. Hazard ratio of temporomandibular disorder in association with depression in Cox proportional hazard models

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Variables

HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI)

Depression

No 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference) Yes 2.64 (2.30-3.03)*** 2.42 (2.09-2.81)*** 2.21 (1.83-2.66)***

Model 1: unadjusted

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, area, occupation, urbanization, income and other psychiatric co-morbidity

***p <0.0001

Table 4. Sex- and age-specific hazard ratio of temporomandibular disorder associated with depression measured with multivariable Cox method

Depression Variables

No† Yes†

Sex* HR (95% CI) HR (95% CI)

Female 1.61 (1.36-1.92)*** 3.54 (2.81-4.45)***

Male 1.00 (reference) 2.23 (1.70-2.94)***

Age, years†

< 20 1.25 (0.87-1.81) 2.70 (1.48-4.94)**

20-39 1.55 (1.09-2.19)* 3.05 (2.10-4.45)***

40-59 1.49 (1.04-2.13)* 2.98 (2.05-4.33)***

≥ 60 1.00 (reference) 3.22 (2.20-4.73)***

† multivariable model including also area, occupation, urbanization, income and other psychiatric co-morbidity

*p <0.05; **P <0.01; ***p <0.0001