Lessons From the First Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review

FROM COMMITMENT TO ACTION ON SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS

state of world population 2013

DIALOGUE

AC T

CIVIL

SOCIETYSRHR INVESTMENT

PARTICIPATION STAKEHOLDERS

EQUALITY

NON-DISCRIMINTATION

CHANGE

HUMAN RIGHTS

HUMAN RIGHTSACCOUNTABILITY

JUSTICE

OBLIGATIONS

IMPLEMENTATIONEQUAL

QUALITY POSITIVE

ADVANCED COMMUNITY

ATTENTION

MECHANISMS

SUCCESSFUL

REPRODUCTIVE

RIGHTS

ACCOUNTABILITY

W ORK

NHRI

ASSESSMENTCover photos: © UN Photo/Jean-Marc Ferré

Table of Contents

Abbreviations and acronyms. ... 2

Acknowledgements ... 2

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...3

CHAPTER 1: THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW AND SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS ...7

What are sexual and reproductive health and rights?... 8

What is the UPR and how does it work? ... 10

Why is the UPR important for sexual and reproductive health and rights? ... 14

Why has this assessment report been prepared? ... 15

CHAPTER 2: SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UPR ...16

State reporting on sexual and reproductive health and rights ... 17

Volume of recommendations and voluntary commitments ... 18

Quality of recommendations ... 20

Responses to recommendations ... 21

Thematic analysis of recommendations... 22

CHAPTER 3: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UPR RECOMMENDATIONS... 31

Planning processes ... 32

Monitoring mechanisms ... 32

Implementation of recommendations ... 33

Degree of implementation ... 34

Thematic analysis of implementation of recommendations ... 35

CHAPTER 4: FINAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR ADVANCING SRHR IN THE UPR ...42

APPENDICES ...46

Appendix 1: List of United Nations Member States comprising each region ... 46

Appendix 2: Implementation of SRHR related recommendations (based on the SRI database) ... 48

REFERENCES ...50

END NOTES ... 51

DISCLAIMER: The designations employed and the presentation of material in maps in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNFPA concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

EDUCATION

LAW

INVESTING

PUBLIC UNIVERSALITY

LEGAL SUSTAINABILITY

COORDINATION

QUALITY OUTCOME

2 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW

Abbreviations and Acronyms

AAAQ Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability, and Quality CAT Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or

Degrading Treatment or Punishment

CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities CSO Civil society organization

FGM/C Female genital mutilation/cutting HIV/AIDS Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome

HRC United Nations Human Rights Council

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICERD International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Racial Discrimination

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

ICPD International Conference on Population and Development

ICRMW International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families LGBTI Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex NGO Non-governmental organization

NHRI National human rights institution

OHCHR Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights PfA Platform for Action

PoA Programme of Action

SRHR Sexual and reproductive health and rights SRI Sexual Rights Initiative

STI Sexually transmitted infection SuR State under Review

UN United Nations

UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNCT United Nations Country Team

UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund UPR Universal Periodic Review WHO World Health Organization

Acknowledgements

This report has been developed by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) under the direction of Luis Mora, Chief of the Gender, Human Rights and Culture Branch, and the technical guidance of Alfonso Barragues. In particular, UNFPA wishes to acknowledge Action Canada on Population and Development, and especially Neha Sood for her substantive expertise and contribution to the drafting of this document.

A special word of thanks is owed to Bruce Campbell and Mona Kaidbey for their encouragement and strategic leadership, as well as to UNFPA colleagues Alanna Armitage and Lily Talapessy, who devoted their time and commitment to peer-review this report.

A particular mention goes to Ida Krogh Mikkelsen for her thorough editorial review of the document.

UNFPA wishes to extend special thanks to the following UNFPA colleagues from country and regional offices who were interviewed about the UPR:

Lola Valladares Tayupanta (Ecuador), Dorothy Nyasulu (Malawi), Hind Jalal (Morocco), Debora Nandja (Mozambique), Diana Ismailova (Tajikistan), Manel Stambouli (Tunisia), Magdalena Furtado (Uruguay), Karl Kulessa and Fuad Aliev (Uzbekistan), Enshrah Ahmed (Arab States Regional Office) and Maha Muna (Pacific Sub-Regional Office). Furthermore, a word of appreciation is owed to Janette Amer and Carolin Schleker (UN-Women) and Karin Lucke and Emilie Filmer-Wilson (United Nations Development Operations Coordination Office) for making time in their busy agendas to participate in this series of interviews and for ensuring a coherent and integrated approach to the United Nations engagement with international human rights mechanisms.

Executive Summary

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a unique mechanism established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2006. This mechanism

facilitates the review of the fulfilment by each United Nations Member State of its human rights obligations and commitments, with its full

involvement, and with the objective of improving the human rights situation on the ground. The outcome of the review is a set of recommendations made to the State under Review (SuR) by reviewing States, the response of the SuR to each recommendation, as well as any voluntary commitments made by it during the review. After the review, the SuR has the primary responsibility to implement the UPR outcome. However, it may do so with the assistance of the United Nations system and participation of civil society, national human rights institutions (NHRIs) and other relevant stakeholders. The UPR is intended to complement and not duplicate or replace the work of other human rights mechanisms such as treaty bodies or special procedures.

The UPR is largely considered a successful mechanism for its ability to bring to the fore human rights concerns in each country to empower civil society, including marginalized and excluded groups, to claim their human rights, and to bring substantial pressure to States to meet their human rights obligations. Due to its comprehensive scope covering the full range of human rights, the UPR provides a valuable opportunity to contribute to the realization of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).

This publication, Lessons From the First Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review: From Commitment to Action on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights1, aims to explore the potential role the UPR mechanism can play in advancing the realization of SRHR at the global, regional and country levels. It assesses the attention the UPR has given to these

issues during its first cycle and identifies ways to enhance this level of attention through all stages of the UPR process.

The significance of the UPR for the

advancement of SRHR is reflected in UNFPA’s Strategic Plan 2014-2017. As discussed in Chapter I below, according to the plan, UNFPA aims to achieve the following outcome: “Advanced gender equality, women’s and girls’ empowerment, and reproductive rights, including for the most vulnerable and marginalized women, adolescents and youth.” The indicator for this outcome is the

“Proportion of countries that have taken action on all of the Universal Periodical Review (UPR) accepted recommendations on reproductive rights from the previous reporting cycle.”

This report assesses the first cycle of the UPR from 2008-2011 from the perspective of

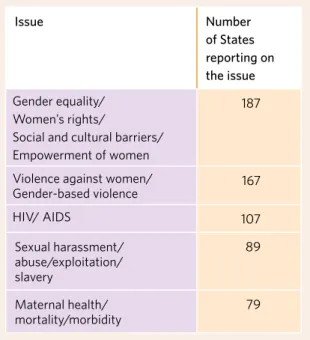

4 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW TABLE 1:

SRHR issues most commonly reported on in national reports

Issue Number of States

reporting on the issue Gender equality/

Women’s rights/

Social and cultural barriers/

Empowerment of women

187

Violence against women/

Gender-based violence 167

HIV/AIDS 107

Sexual harassment/

abuse/exploitation/

slavery

89

Maternal health/

mortality/morbidity 79

recommendations related to SRHR. It examines the level of attention paid to different aspects of SRHR, the quality of recommendations, positive developments, issues of concern, and regional trends (Chapter II). It also assesses the implementation of UPR outcomes, including national planning processes and monitoring systems (Chapter III). The report concludes with final considerations for various stakeholders (Chapter IV).

In terms of the level of attention to SRHR, an examination of the reporting by SuRs reveals that all 193 States reported on more than one aspect of SRHR. Table 1 lists the five issues most reported on, and the number of States that reported on each.

A total of 21,956 recommendations and

voluntary commitments were made during the first cycle, of which 5,720 or 26 per cent pertained to SRHR. Examining the 12 sessions that comprised the first UPR cycle 2008-2011, it is observed that in the first session, this proportion was 20 per cent; by the eleventh session, it had risen to

33 per cent. This shows that SRHR issues received increased attention as the first cycle of the UPR progressed.

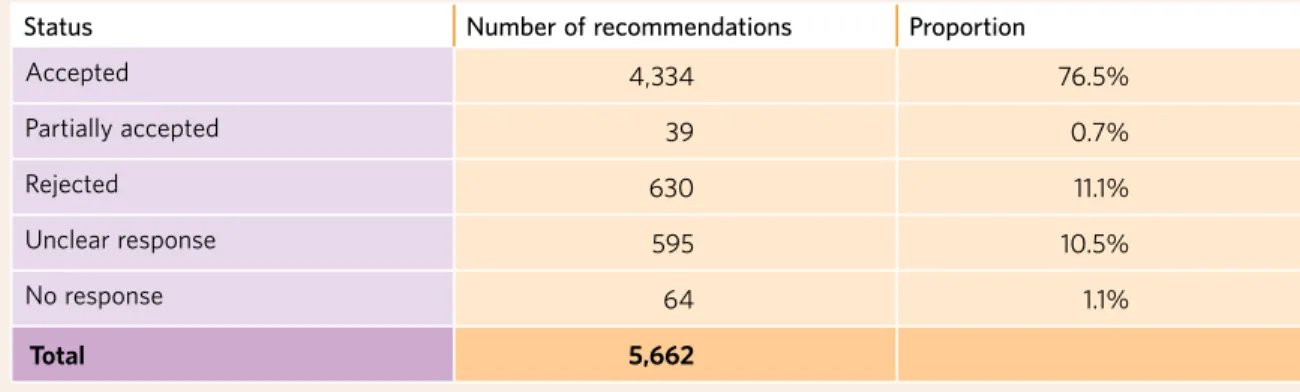

Out of the 5,696 SRHR-related recommendations made during the first cycle, 4,396 or 77 per

cent were accepted or partially accepted. A significant number, 659 or 12 per cent, received either an unclear response or no response at all;

however, this presents ample scope to enter into dialogue with governments about implementing these recommendations. The remaining 11 per cent were rejected by SuRs. In cases where the recommendation is rejected by a government due to lack of capacity or other reasons, the government could be offered support towards the implementation of such recommendations.

A large proportion of the SRHR-related recommendations pertain to human rights

instruments, gender equality, gender-based violence and women’s human rights. Fewer recommendations have been made on a number of other SRHR issues, including contraception and family planning, early pregnancy, sex work and sexuality education, among others.

As with the UPR in general, recommendations made on SRHR issues have been of a varying level of specificity. They included recommendations that are robust, calling for specific actions and reflecting a human rights-based approach. Such recommendations have called on the SuR to sign or ratify or accede to international human rights instruments; to review, enact and implement specific laws and policies; to ensure participation of rights-holders in decision making; to ensure good quality in the implementation of programs;

and to collect and disaggregate data, among other actions. Conversely, some recommendations were very general and some called for States to just

“consider” taking actions towards guaranteeing rights. Nevertheless, each recommendation increases potential for dialogue, advocacy and action for change.

The implementation of the UPR outcome is arguably the most important stage of the UPR

TABLE 1

process, as this is what can improve the human rights situations within countries through changes in laws and policies and improvements in programme planning, budgeting, implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

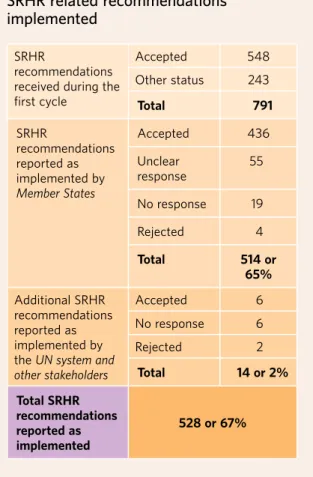

According to information provided by 56 states in their review reports for the second UPR cycle, 67 per cent of SRHR-related recommendations (528 out of 721) have been reported partially or fully implemented. In some cases States are implementing recommendations beyond those that were formally accepted. This was the case for six SRHR-related recommendations that had been rejected and 80 that had received unclear or no responses. This demonstrates that relevant stakeholders should engage in policy dialogue and provide support to Governments on SRHR issues.

Actions taken to implement recommendations have included inter alia legal and policy reform;

the enactment of new laws, policies and strategies;

setting up of national machineries, institutions and working groups; training of community workers,

States personnel and community leaders; setting up of community watchdog groups; investing in infrastructure and social services; and public education.

The report observes that there are a number of examples where positive measures have been taken in implementing the first cycle of UPR recommendations, including strong and beneficial collaboration among governments, UN agencies and civil society. Azerbaijan increased the minimum age of marriage to 18 years and criminalized the act of forcing women into marriage. Botswana reported passing the Domestic Violence Act, which provides legal remedies to victims of marital rape, and the Republic of Korea reported prosecuting cases of marital rape. Cuba introduced a sexuality education curriculum throughout the national education system for all levels of education. In Pakistan, a legal amendment criminalized forced marriages, child marriages and other customary practices that are discriminatory towards women and girls. In Turkmenistan, the Government collaborated with

Stages of the UPR process

Review

Reporting Follow up

Planning Implementation

Monitoring

Midterm report

1 3 2

FIGURE 1

6 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW

UNFPA to establish two youth centres to familiarize young people with HIV prevention, using a peer-to- peer teaching approach.

The report observes that a specific recom- mendation rather than a general one, and one that addresses fewer issues rather than several is more effective for tracking implementation and thus holding the SuR accountable. At the same time, the implementation of recommendations formulated in general terms around issues such as health, education, discrimination, violence, gender equality, human rights, et cetera can involve specific actions pertaining to SRHR. Concrete information from the United Nations system, NHRIs and civil society on the implementation of UPR outcomes by the SuR, or the lack thereof, is critical for effective tracking.

The national UPR implementation plan should specify key objectives, concrete actions, clear indicators and timeframes, allocated responsibilities at various levels, identified available resources, and required assistance and support. The process of

developing the implementation plan should ensure the full and effective participation of civil society and collaboration with the United Nations system and NHRIs.

The implementation plan should include a monitoring and evaluation component in order to ensure that it is implemented in a timely and effective manner. The monitoring framework should identify what kind of information is relevant for each UPR recommendation, with input from different stakeholders, including affected marginalized populations. It is important to ensure that adequate institutional capacity and appropriate methodologies are present for data collection and analysis. The implementation plan and monitoring framework for the UPR outcome should bring together recommendations from all other human rights mechanisms as well. This would enhance the actions taken to implement the UPR outcome, as well as strengthen implementation, monitoring and reporting of the other recommendations.

Ultimately, governments have the responsibility to implement the recommendations they have willingly accepted. The clustering of SRHR-related recommendations in the context of national planning, coordination and tracking mechanisms will contribute to advancing these rights in a less fragmented and mutually reinforcing way.

UNFPA stands ready to support the establishment and strengthening of sustainable, participatory, inclusive and transparent planning, coordination and tracking mechanisms so the UPR can contribute to realizing SRHR for all without discrimination.

Peer educator in SRHR, Mozambique © Benedicte Desrus/Sipa Press

EDUCATION

IMPLEMENTATION

LEVEL

RIGHTS

HEALTH

LEVEL

ALITY SITIVE

SUPPORT

EDUCATION ATTENTION

COMMUNITY

IS SUE

MINIMUM

DOMESTIC

PRACTICE

LEVEL

ACTIONS

REPORT ENSURE REPRODUCTIVE

MECHANISMS

ACCOUNTABILITY

LEGAL

IMPROVE

HEALTH INVEST MEMBER

ADVANCED

DIALOGUE

REVIEW

SHARE

THE UNIVERSAL

PERIODIC REVIEW AND SEXUAL AND

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS

This chapter provides a definition of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), grounded in the human rights framework. It describes the Universal Periodic Review (UPR),

its process and its strengths, and explains why the UPR is significant for the advancement of SRHR. Following from this, it explains the relevance of the timing and content of this

report and how it is expected to be used.

CHAPTER 1

PLAN PUBLIC STAGES

REVIEW

FRAMEWORK

COUNCIL POLICY

8 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW

What are sexual and reproductive health and rights?

The 1994 Programme of Action (PoA)2 of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) was the first among inter- national development frameworks to address issues related to sexuality, sexual and reproductive health, and reproductive rights. In paragraph 7.2 the ICPD PoA defines an individual’s sexual and reproductive health as complete well-being related to sexual activity and reproduction.3

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) encompass both entitlements and freedoms. This includes the definition of reproductive rights in paragraph 7.3 of the ICPD PoA, which clarifies that these are not a new set of rights but human rights in existing human rights instruments related to sexual and reproductive autonomy and the attainment of sexual and reproductive health. Additionally, the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action (PfA)4 expands this definition to cover both sexuality and reproduction by affirming in paragraph 96 the right to exercise control over and make decisions about one’s sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. The above language has since been reiterated in different United Nations documents5, including outcomes of monitoring and review processes of the ICPD PoA and the Beijing PfA.

Standards relating to SRHR are found in inter- national human rights treaties, including:

• International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)

• International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

• International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

• Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

• Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)

• Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

• International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICRMW)

• Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

Additionally, other international and regional human rights instruments and national laws are relevant. Furthermore, United Nations treaty monitoring bodies have expanded the application of human rights standards in the area of SRHR through authoritative interpretations in General Comments and Recommendations as well as through concluding observations.

State responsibility in respecting, protecting and fulfilling sexual and reproductive

health and rights

As with the realization of all human rights, the realization of SRHR requires duty bearers (the State) to respect, protect and fulfil such rights, regardless of the social, political or cultural norms that may prevail at the national level, and in accordance with human rights principles of equality, non-discrimination, participation, inclusion, accountability and rule of law.6 In the context of SRHR, States have the obligation to respect, protect, and fulfil human rights, which should guide the development of laws and policies, as well as practices.

• The obligation to respect requires that states do not act in a way that interferes with individuals’

enjoyment of their rights, either directly or indirectly.7 As such, states should not limit access to contraceptives, withhold or misrepresent health- related information, or utilize coercive medical practices.8

• The obligation to protect demands that states take measures to prevent third parties from interfering with human rights and impose sanctions on those who violate others’ human rights.9 For instance, states should adopt legislation to ensure equal access to health care, ensure that health services from private providers comply with human rights

TABLE 2:

Illustrative rights and obligations related to sexual and reproductive health and rights

SRHR encompasses the following rights (nonexhaustive list):

Illustrative State Obligations:

The Right to Life • Prevent maternal mortality and morbidity through safe motherhood programs

• Ensure access to safe abortion services when the life and health of the mother is at risk The Right to Health • Ensure sex workers have access to the full range of sexual and reproductive health care services

• Ensure reproductive health services are available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality (AAAQ) The Right to Education &

Information • Ensure school curriculums include comprehensive, evidencebased, and nondiscriminatory sexuality education

• Ensure accurate public education campaigns on the prevention of transmission of HIV The Rights to Equality and

Non-Discrimination • Prohibit discrimination in access to health care on grounds of sex, age, disability, race, religion, nationality, economic status, sexual orientation, health status including HIV/AIDS, et cetera

• Do not deny access to health services that only women need The Right to Decide

Number and Spacing of Children

• Ensure the full range of modern contraceptive methods

• Provide women with comprehensive and accurate information to ensure informed consent to contraceptive methods, including sterilization

The Right to Privacy • Ensure the right to bodily autonomy and decisionmaking around sexual and reproductive health issues

• Guarantee confidentiality and privacy with regard to patient health care information, including prohibiting third party consent, such as spousal and parental, to sexual and reproductive healthcare services

The Right to Consent to Marriage and Equality in Marriage

• Prohibit and punish child and other forced marriages

• Set the age limit for marriage at 18, equally for boys and girls

The Right to be Free from Torture or Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

• Guarantee access to emergency contraception, especially in cases of rape

• Guarantee access to termination of pregnancy when a woman’s life or health is in danger, in cases of rape and fatal fetal impairment

The Right to be Free from Sexual and GenderBased Violence

• Ensure genderbased violence, including domestic and intimate partner violence, is effectively prohibited and punished in law and in practice

• Prohibit and punish all forms of rape, in peacetime and in conflict, and including marital rape

• Prohibit and punish all forms of violence perpetrated because of sexual orientation The Right to be Free from

Practices that Harm Women and Girls

• Prohibit and punish all forms of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C)

The Right to an Effective

Remedy • Ensure effective mechanisms are in place for women to complain of SRHR violations

• Ensure access to effective counsel for women who are unable to afford a lawyer TABLE 2

standards, and take measures to protect individuals from harmful traditional practices.10

• The obligation to fulfil requires states to adopt legislative, budgetary, administrative, and judicial measures towards the full realization of human rights.11 States have the obligation to create a

favourable legal and policy environment, which is non-discriminatory, protects individuals from viola- tions of their SRHR, and enables rights-holders to claim their rights. States should ensure that decision-making processes are transparent, provid- ing rights-holders with information about such

10 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW

registration systems, providing judicial and non-judicial legal remedies, investigating and punishing violations as well as providing redress and reparations, providing access to legal aid, and removing barriers to justice and redress systems, among other actions.

At the international level, State Parties to inter- national human rights treaties must report to treaty monitoring bodies in a timely manner. All States must report to the UPR process, and implement the recommendations of various human rights mechanisms.

Donors and United Nations agencies also play a role in ensuring that development assistance contributes to the realization of SRHR through their conformity to international human rights standards.

This entails ensuring that development policies are human rights-based and support national efforts, including participation of rights-holders in decision- making processes, and special attention to those most affected and marginalized. Furthermore, the role of the private sector through its philanthropic engagement in development and the corporate human rights responsibility of businesses and enterprises should not be understated.

What is the UPR and how does it work?

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a unique mechanism established by the United Nations General Assembly through its resolution 60/251 dated March 15, 2006. It mandated the Human Rights Council (HRC) to “undertake a universal periodic review, based on objective and reliable information, of the fulfilment by each State of its human rights obligations and commitments in a manner which ensures universality of coverage and equal treatment with respect to all States; the review shall be a cooperative mechanism, based on an interactive dialogue, with the full involvement of the country concerned and with consideration given to its capacity-building needs; such a mechanism shall complement and not duplicate the work of treaty bodies.”14

processes and ensuring their participation in such processes.

States have the obligation to realize progressively economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to health, by employing the maximum available resources.12 To that end, states should put in place effective planning mechanisms and allocate sufficient budgetary resources. This involves developing strategies, plans, policies and programs on or encompassing SRHR, using best available evidence; enacting regulations to protect against violations of individuals’ SRHR by non-State actors; devoting the maximum available resources towards implementation, monitoring and evaluation remedies and other accountability mechanisms; ensuring participation of rights- holders in planning and budgeting processes; and ensuring that all related information is made avail- able in a transparent manner.

The implementation of plans, policies and programmes that support the realization of SRHR must be grounded in human rights standards and principles. All sexual and reproductive health facili- ties, information, education, goods and services must be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality. The provision of information, education, goods and services must be free from barriers, provided by well-trained personnel, and free from all forms of discrimination. States must ensure the participation of rights-holders in the design, deliv- ery and evaluation of such information, education, goods and services.13

States have an obligation to monitor and review the implementation of laws, programmes and policies, and establish remedies where SRHR have been violated. At the national level, this entails ensuring the existence of effective human rights institutions, providing access to informa- tion about accountability mechanisms, including rights-holders in decision-making, establishing effective monitoring and review mechanisms, and developing rights-based indicators. It further entails collecting disaggregated data, strengthen- ing birth and death (including maternal deaths)

The objectives of the UPR are outlined in HRC resolution 5/1, also known as the “Institution-Building Package”:15

a The improvement of the human rights situation on the ground;

b The fulfilment of the State’s human rights obligations and commitments and assessment of positive developments and challenges faced by the State;

c The enhancement of the State’s capacity and of technical assistance, in consultation with, and with the consent of, the State concerned;

d The sharing of best practice among States and other stakeholders;

e Support for cooperation in the promotion and protection of human rights;

f The encouragement of full cooperation and engagement with the Council, other human rights bodies and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

The UPR is an important process for advancing the realization of human rights for several reasons.

It is universal; each of the 193 United Nations Member States is peer-reviewed on its entire human rights record every four and a half years. Each State under Review (SuR), regardless of size or political influence, is subject to the same rules and scrutiny and must respond to each recommendation put forward by reviewing States, as well as report on the implementation of recommendations accepted by it.

Unlike other monitoring mechanisms of the UN, such as the treaty monitoring bodies, the UPR is truly comprehensive and is not limited by a Member State’s lack of ratification of one or more treaties. This means that the UPR can be utilized to apply human rights standards to all issues of concern within a country, and to engage in dialogue with governments about issues that might not be addressed through other applicable accountability mechanisms. Also, the UPR can serve as a mechanism to strengthen treaty ratification and as an accountability mechanism for international agreements that do not build in strong human rights-based

accountability systems of their own, such as the ICPD Programme of Action, the Beijing Platform for Action and the Millennium Development Goals. It can also be utilized to advise a SuR on how to apply a human rights-based approach to its efforts to implement these agreements.

It is also a transparent process. All documents prepared for the review are publicly available; the review is webcast live and archived; all questions and recommendations directed to a SuR, its responses to recommendations and its reporting on the implementation of recommendations are published and publicly available. Further, the SuR is required to respond to all the recommendations put to it, contributing to greater transparency as its views on each recommendation is expected to be made known.

This is a distinct advantage over treaty body processes, where the views of the SuRs about concluding observations directed at them may not be known.

The UPR carries political weight since it involves States making recommendations to other States, and can be used to bring substantial pressure to SuRs to meet their international obligations.

Stages of the UPR process Review

Reporting Follow up

Planning Implementation

Monitoring

Midterm report

1 3 2

FIGURE 2

The UPR is a three-stage process:

STAGE 1 Review of the human rights situation of the SuR

STAGE 2 Follow up to the review

STAGE 3 Reporting for the subsequent review

12 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW

b Review of the SuR by the UPR Working Group Although not formally part of the UPR process, the two to three months preceding the review could be utilised by the United Nations system, civil society, NHRIs and other stakeholders to advise reviewing States to ask particular questions or make specific recommendations to the SuR. The review itself takes place during a three-and-a-half hour16 meeting in Geneva, and is conducted by the UPR Working Group, which is composed of the 47 members of the HRC. However, any United Nations Member State or Non-member Observer State may participate in the dialogue with the SuR; these are referred to as reviewing States in this report. The UPR is meant to be a cooperative mechanism, involving an interactive dialogue about the human rights situation in each country, actions taken to improve it and the existing challenges to the realization of human rights, a sharing of best human rights practices, and a discussion about States’ capacities to deal with human rights challenges. During the review, the SuR presents the information collected by it for the review and may respond to questions submitted in advance. Any reviewing State may make an intervention17 in the interactive dialogue, posing questions, making comments and/or making recommendations to the SuR. The SuR is given opportunities to respond to questions and comments from reviewing States. Civil society, NHRIs, the United Nations system and other stakeholders may attend but not participate in the interactive dialogue.

The outcome of this meeting is a report of the UPR Working Group containing, inter alia, recommendations by reviewing States and voluntary commitments by the SuR, prepared by the troika.

This Working Group report is adopted no sooner than 48 hours after the review but within a week of it. The SuR has the opportunity to make preliminary comments on the recommendations. In practice, at this stage, SuRs might “accept” a recommendation or say that it “enjoys their support”; they might “reject”

a recommendation or say that it “does not enjoy their support”. Usually they defer providing responses to a

STAGE 1 Review of the human rights situation of the SuR

The review itself involves a number of steps:

a Gathering and Preparation of UPR Information

b Review of the SuR by the UPR Working Group

c Review and adoption of the UPR outcome during a regular session of the HRC

a Gathering and Preparing information for the Universal Periodic Review

The SuR prepares information for the review that may be submitted beforehand in writing, in the form of a national report, or delivered orally during the review, though in reality a written national report is almost always submitted. This report is expected to be prepared through broad consultations with relevant stakeholders including the United Nations system and civil society.

The OHCHR prepares a compilation report of United Nations information, summarizing information from reports of United Nations agencies, Funds and Programmes, United Nations Special Procedures, and United Nations human rights treaty bodies. It also prepares a stakeholder summary report, summarizing information provided by civil society and national human rights institutions. These two reports are critical components of the review as they offer an independent perspective on the human rights situation in the country and serve to strengthen the accountability of the mechanism and of the SuR. Accordingly, reviewing States often rely on these reports to make recommendations to the SuR. In practice, these three documents together form the basis for the review; however, they do not confine the scope of the review, as the original sources of these documents are also available and can be relied upon by reviewing States. Additionally, reviewing States may submit questions in writing, in advance of the review, to the troika – a group of three States who serve as rapporteurs and facilitate the review, selected through a drawing of lots for each SuR’s review.

BOX 1:

SuR Responses to Recommendations

There is no clear guidance to or expectations from States regarding their responses to recommendations. The OHCHR recognizes the responses,

“supported” and “noted”, as reflected in its Universal Human Rights Index (http://uhri.ohchr.org/).

In practice, over the course of the first cycle of the UPR, States have provided a range of responses, which the SRI database has grouped into five categories—recommendations that:

• Are “accepted” or enjoy the support of the SuR

• Are “partially accepted” or accepted in part

• Are “rejected” or do not enjoy the support of the SuR

• Received an “unclear” or general response

• Received “no response”

BOX 1

number of recommendations, with the understanding that such responses must be provided before the UPR outcome is finally adopted at a HRC regular session approximately five months after the Working Group session. All recommendations, regardless of the response of the SuR, are included in the Working Group report. After this report has been adopted, States can make only editorial modifications of their own statements within the following two weeks, though they cannot make any modifications to their recommendations in the Working Group report.

c Review and adoption of the UPR outcome during a regular session of the HRC

The UPR outcome consists of the UPR Working Group report and any addenda containing responses of the SuR to recommendations not responded to at the Working Group stage and any further voluntary commitments by the SuR. The outcome is adopted in plenary during a regular session of the HRC, approximately five months after the UPR Working Group session. In the intervening period, the SuR examines the recommendations received during the review, particularly the ones to which it has deferred response during the Working Group stage; it then takes decisions regarding its response to each. Ideally, the SuR would consult civil society, NHRIs and development partners at the national level before taking such decisions. This is an opportunity for the United Nations system and other stakeholders to advise the government regarding deferred recommendations and offer support for their implementation. It is also an opportunity for civil society, Parliamentarians and other stakeholders to apply pressure on the government to accept relevant recommendations – including through direct engagement, consultations, or Parliamentary debates – and build support among the media and the general public.

During the UPR outcome adoption at the HRC plenary session, the SuR often introduces its response to recommendations made by reviewing States, announces any voluntary commitments it is making, and replies to questions and issues that

were not sufficiently addressed during the Working Group session. Time is also allotted (2 minutes each) to Member and Observer States and other observers, including United Nations entities, who may wish to express their opinion on the outcome of the review.

In reality, it is uncommon for non-State entities to have the opportunity to speak, due to limitations of time. Time is also allotted for other stakeholders, including NHRIs and NGOs, to make general comments on the outcome of the review.

STAGE 2 Follow up to the review

After the review, the SuR has the primary responsi- bility to implement the accepted recommendations and voluntary commitments, and to determine how it will do so. However, it may request the assistance of the United Nations representation at the national and/or regional levels.18 Further, effec- tive participation of civil society, national human rights institutions and other relevant stakehold- ers is one of the principles underpinning the UPR process. It is important that the SuR collaborates with these stakeholders in planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating the actions it undertakes to implement recommendations and voluntary commitments. This is the most important stage of the UPR process, when actions are undertaken to improve the human rights situation in the country.

14 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW STAGE 3 Reporting for the subsequent review

States are encouraged to provide to the HRC, on a voluntary basis, a mid-term update on implementation of their UPR outcome.

In addition, they may choose to provide regular updates during HRC sessions under agenda item 6 of the UPR. During the subsequent review, the SuR is expected to provide information on the measures taken to implement recommendations and voluntary commitments of the previous review. Hence, the UPR ensures that all countries are accountable for progress or failure in implementing the outcomes of the UPR. Further, this review and subsequent reviews maintain their focus on the developments of the human rights situation in the SuR. Thus, new issues that may have emerged in the preceding four and a half years can be raised, as well as earlier issues that are still relevant and were not adequately covered in the previous review.

Why is the UPR important for sexual and reproductive health and rights?

The UPR has been significant for SRHR. During the first cycle of the UPR, a total of 21,95619 recommendations and voluntary commitments were made, of which 5,720 pertained to SRHR.

This is elaborated in Chapter II.

The data demonstrates the significance of SRHR and underscores the need for State action in this realm. It also underscores the potential that the UPR holds to advance SRHR both at intergovernmental and national levels in four ways:

1 The UPR helps to overcome fragmentation of SRHR in different treaties by reviewing the full spectrum of human rights

obligations contained in the SRHR agenda.

2 The high level of attention given by the UPR to SRHR contributes to emphasizing that SRHR are enforceable human rights.

3 UPR recommendations can contribute to increasing ratification of treaties, lifting of reservations, as well as adoption and implementation of legal, policy, budgetary, programming, and other measures at national and subnational levels.

4 The UPR creates global and national platforms for policy dialogue between governments, civil society and other relevant stakeholders concerned with the enjoyment of SRHR.

Due to its universality and comprehensive scope covering the full range of human rights, the UPR provides a valuable opportunity to highlight shortcomings related to fulfilment of SRHR, and hold States accountable for the SRHR situation in their countries. The SuR is expected to respond to all questions asked and each recommendation made.

Further, it is expected to report on the actions taken to implement the recommendations it accepted during its review. Thus, every question asked and every robust recommendation made pertaining to SRHR, especially in relation to legal and policy reform and human rights-based programmatic response, contributes in some way to the realization of SRHR.

The UPR process is underpinned by the principle of participation of all relevant stakeholders,

including civil society. The HRC expects States to consult widely with relevant stakeholders regarding preparation for and follow up to the review.20 States should ensure their systematic, meaningful and effective participation at all stages of the UPR process including reporting for the review, responding to recommendations, preparing implementation plans and monitoring. This could be done through sharing information about the UPR widely among various stakeholders, including through translation in different local languages, setting up mechanisms and procedures for multi- stakeholder policy dialogue, as well as conducting broad and accessible consultations. Following a human rights-based approach, particular attention

should be paid to ensuring the participation of marginalized populations at all stages of the UPR.

This provides for the realities and views of rights- holders to be central to the review process, thus supporting the effective and inclusive realization of all human rights, including SRHR, without selectivity.

As a critical component of this, the UPR process also provides many opportunities for dialogue and advocacy, which may be pivotal for SRHR to become part of the review.

Why has this assessment report been prepared?

By March 2012, all 193 United Nations Member States had been reviewed once, during the first cycle of the UPR. Overall, the mechanism is considered to be making a positive contribution. The UPR has increased cooperation and dialogue about human rights at multiple levels – between States; within and between government machineries; and among States, civil society, NHRIs and the United Nations system.

It has also played a significant role in systematizing the collection, assessment and documentation of the human rights situation within countries by States, civil society and the United Nations system.

The significance of the UPR is reflected in

UNFPA’s Strategic Plan 2014-2017, where the overall goal of UNFPA is to “achieve universal access to sexual and reproductive health, realize reproductive rights, and reduce maternal mortality to accelerate progress on the ICPD agenda, to improve the lives of adolescents and youth, and women, enabled by population dynamics, human rights, and gender equality.” As outlined in the Strategic Plan, UNFPA aims to contribute to the stated outcome: “Advanced gender equality, women’s and girls’ empowerment, and reproductive rights, including for the most vulnerable and marginalized women, adolescents and youth.”

The indicator for this outcome is: “Proportion of countries that have taken action on all of the Universal Periodical Review (UPR) accepted recommendations on reproductive rights from the previous reporting cycle.”

Accordingly, the new strategic plan facilitates a more systematic engagement of UNFPA with the

UPR process in the coming years. This is outlined in output 9: “Strengthened international and national protection systems for advancing reproductive rights, promoting gender equality and non-discrimination and addressing gender-based violence.” Output indicator 9.2 outlines UNFPA’s work with the UPR and other human rights mechanisms: “Number of countries with a functioning tracking and reporting system to follow up on the implementation of reproductive rights recommendations and obligations.”

In this context, it is important to assess the first cycle of the UPR from an SRHR perspective, examining attention paid to different aspects of SRHR, the quality of recommendations, positive developments, issues of concern, and regional trends.

It is also important to assess the implementation of UPR recommendations related to SRHR, including in the context of national planning processes and monitoring systems. Following the review at the HRC, the SuR’s implementation of recommendations and voluntary commitments is arguably the most important stage of the UPR process, as this is what can improve the SRHR situations within countries, through changes in laws and policies and improvements in programme planning, budgeting, implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

This report provides guidance for strengthening UNFPA’s future engagement with the UPR process at global, regional and country levels. Furthermore, this report outlines relevant considerations for various UPR stakeholders including governments, the United Nations system, CSOs and NHRIs in order to improve the effectiveness of the UPR process in advancing SRHR.

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS IN

THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC

REVIEW

This Chapter assesses the first cycle of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) from a sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) perspective, highlighting both positive and negative trends. It includes an examination of States under Review (SuRs)

reporting on SRHR issues, recommendations made by reviewing States and SuR responses to these recommendations. It also includes an in-depth assessment of the

UPR’s performance on select SRHR issues.

CHAPTER 2

SIGNIFICANT

LEVEL

RECOMMENDATIONS ACCEPTED

QU ALITY NUMBER ADVANCED

COUNTRIES

VOLUNTARY

PERTAINING

LE GAL

MATERNAL

DOMESTIC

LEVEL

PUBLIC

SRHR REVIEW

MECHANISMS

RECOMMENDATIONS

FIRST

LEGAL

SERVICE

WOMEN CYCLE ATTENTION

FAMILY

SPECIFIC

REVIEW

CYCLE DATA STAGES

GENERAL

FRAMEWORK

GENDER

HIV/AIDS

HUMAN

INVEST

RESPONSIVE

INFORMATION

BOX 2:

Components of sexual and reproductive health and rights in the database

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) encompass a wide range of issues, including but not limited to:

• Comprehensive sexuality education

• Access to sexual and

reproductive health information, education and services

• Prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STI)

• HIV prevention, treatment and care, including voluntary and confidential counselling and testing

• Prevention and treatment of maternal morbidities

• Prevention and treatment of infertility

• Prevention and treatment of reproductive cancers

• Assisted reproduction

• Sexual and reproductive coercion

• Forced impregnation

• Involuntary sterilization

• Early marriage

• Forced marriage

• Sexual harassment

• Sexual violence

• Domestic violence and intimate partner violence

• Marital rape

• Polygamy

• Witch hunting

• Dowry

• Son preference

• Sexual abuse and exploitation

• Gender-based violence

• Femicide

• Female infanticide

• Female genital mutilation/

cutting (FGM/C)

• So-called “honour” killings

• Trafficking in women and girls

• Trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation

• Gender equality

• Sexual orientation

• Gender identity and expression

• Rights of intersex persons

• Rights of sex workers

• Rights of people living with HIV/AIDS

• Rights of persons with disabilities

• Women’s human rights (to participation, resources, decent work et cetera)

• Empowerment of women and girls

• Rights of adolescents to sexual and reproductive health information, education and services

BOX 2

RECOMMENDATIONS

RESPONSIVE

This assessment report is based on data from a database21 that records all information from the UPR related to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), including recommendations, voluntary commitments, questions, comments, and information from national reports, compilations of United Nations information and summaries of stakeholder information. This searchable database is useful to track the performance of the UPR on various SRHR issues and can serve as a critical resource for developing submissions for the UPR and for advocacy. This database has been used to examine the trends elaborated in this chapter.

While all SRHR issues are interrelated and must be understood utilizing a broad frame of analysis, the database uses a list of 55 categories (see Box 2) to tag information in order to allow for detailed research and analysis. As with any listing, this one is not exhaustive and contains the category “others”.

It is important to bear in mind two points in order to understand fully the statistics presented in this chapter. First, this database includes information pertaining to women’s rights and gender equality, in so far as it relates to SRHR. Secondly, the database also contains information pertaining to human rights instruments that are understood to cover SRHR, such as the ICCPR, ICESCR, CEDAW, CRC, CRPD and the Palermo protocol, among others. Together, these two sets of information constitute a significant proportion of the information in the database.

Information pertaining generally to human rights (which may encompass SRHR if the SuR chooses to interpret them accordingly), but not specifically detailing SRHR issues, has not been included in the SRI’s database.

State reporting on sexual and reproductive health and rights

An examination of the information provided by SuRs in the national reports for the first cycle of the UPR reveals that all 193 States reported on more than one aspect of SRHR. Table 1 lists the five issues most reported on and the number of States that reported on each. Conversely, States reported very

18 LESSONS FROM THE FIRST CYCLE OF THE UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW TABLE 3:

SRHR issues most commonly reported on in national reports

Issue Number

of States reporting on the issue Gender equality/

Women’s rights/

Social and cultural barriers/

Empowerment of women

187

Violence against women/

Gender-based violence 167

HIV/ AIDS 107

Sexual harassment/

abuse/exploitation/

slavery

89

Maternal health/

mortality/morbidity 79

TABLE 3 while the twelfth session produced 2,506 –

almost five times the volume of the first session (see Table 5).

Recommendations on SRHR issues followed a similar trend. The first session of the UPR produced a small number of SRHR related recommendations and voluntary commitments, 106 in total, averaging approximately 7 per State. These numbers increased steadily with successive sessions. By the twelfth session, the number of SRHR related recommendations and voluntary commitments went up to 620, with the eleventh session producing the highest number of the first cycle – 724 in total, and an average of approximately 43 per State. These trends are illustrated clearly in Table 4.23

Of course, it is to be expected that, as the number of overall recommendations increased, the number of SRHR related recommendations would also increase. However, it is important to examine what proportion of overall recommendations and voluntary commitments pertained to SRHR. In the first session, these constituted 20 per cent of the total; by the eleventh session, this figure went up to 33 per cent. This shows that SRHR issues received greater attention as the first cycle of the UPR progressed.

There are a few possible reasons for this increase in attention to SRHR issues: increased engagement of SRHR activists, organizations and researchers with the UPR process, including through stakeholder submissions and advocacy with embassies and missions; increased input on SRHR issues by the United Nations system;

and increased advocacy on SRHR issues at the Human Rights Council (HRC) and the United Nations in general. It is evident from Table 5 that SRHR related recommendations have consistently constituted a significant proportion of total UPR recommendations. Due to the fact that SRHR continue to be contested by some Member States and violated in all parts of the world, it is to be expected that significant attention would be paid to these rights issues within the UPR.

infrequently on issues such as sex work, abortion, polygamy, forced sterilization, so-called “honour”

crimes, age of consent and sexual activity of minors, conscientious objection, and “adultery” or sex outside of marriage.

Besides the frequency of reporting, another important dimension is the quality of reporting by SuRs on SRHR issues. While analysis of this dimension is beyond the scope of this report, stakeholders are encouraged to examine national reports submitted by the country or countries that they are concerned with, to assess how the SuR has reported on such issues. National reports are publicly available on the website of the OHCHR.22

Volume of recommendations and voluntary commitments

As the first cycle of the UPR progressed, engagement of Member States with the UPR process increased as reflected in the increasing number of recommendations received by reviewed States. The first session of the UPR produced 519 recommendations and voluntary commitments,

TABLE 5:

SRHR related recommendations and voluntary commitments as a proportion of total recommendations and voluntary commitments, by UPR session

UPR session Overall recommendations +

voluntary commitments SRHR recommendations +

voluntary commitments Proportion*

1st (Apr 2008) 519 106 20%

2nd (May 2008) 935 245 26%

3rd (Dec 2008) 1398 291 21%

4th (Feb 2009) 1844 398 22%

5th (May 2009) 1706 446 26%

6th (Dec 2009) 2080 520 25%

7th (Feb 2010) 2195 476 22%

8th (May 2010) 2143 580 27%

9th (Nov 2010) 2095 643 31%

10th (Jan 2011) 2344 671 29%

11th (May 2011) 2191 724 33%

12th (Nov 2011) 2506 620 25%

Total 21956 5720 26%

*Approximated to the nearest whole number TABLE 4:

SRHR related recommendations, voluntary commitments, and average per country, by UPR session

UPR session SRHR

recommendations SRHR voluntary

commitments SRHR recommendations

+voluntary commitments Number of

countries reviewed Average per country*

1st (Apr 2008) 103 3 106 16 7

2nd (May 2008) 239 6 245 16 15

3rd (Dec 2008) 284 7 291 16 18

4th (Feb 2009) 398 0 398 16 25

5th (May 2009) 446 0 446 16 28

6th (Dec 2009) 520 0 520 16 33

7th (Feb 2010) 475 1 476 16 30

8th (May 2010) 579 1 580 15 39

9th (Nov 2010) 640 3 643 16 40

10th (Jan 2011) 671 0 671 16 42

11th (May 2011) 724 0 724 17 43

12th (Nov 2011) 617 3 620 17 36

Total 5696 24 5720 193 30

*Approximated to the nearest whole number TABLE 4

TABLE 5