Chapter Four

Hypotheticality in Taiwanese Conditionals

We have seen in Chapter Two (Section 2.2) the three types of reasons for a speaker to frame propositions in a conditional sentence (that is, the speaker is not engaging in full assertion)—it may be due to the speaker’s lack of knowledge; it may be concerned with the speaker’s marking of epistemic distance to the proposition in the protasis; or it may be related to the appropriateness of performing a speech act.

The speaker’s lack of knowledge, among others, is the most prototypical motivation for uttering a conditional sentence (cf. Dancygier 1998, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005). Following this, when uttering a conditional sentence, the speaker has no well-justified knowledge about the state of affairs in the protasis and the apodosis.

That is, the speaker uttering a conditional sentence is not ready to back up the proposition of either the protasis or the apodosis with evidence. Therefore, the speaker does not make full-commitment to the state of affairs in conditionals. Thus, conditionals are uncertain and hypothetical in essence.

Hypotheticality of a conditional sentence is defined as the degree of the speaker’s commitment to the factuality of the propositions expressed in the subordinate clauses, especially in the protases (cf. Comrie 1986, Athanasiadou and Dirven 2002, Wierzbicka 2002). Comrie (1986) further proposes that hypotheticality is a ‘continuum’, and different languages simply distinguish different degrees of hypotheticality along this continuum.

Languages vary in their grammatical forms for distinguishing hypotheticality.

In English conditionals, differentiation of degrees of hypotheticality is reflected mainly in verb forms, i.e. tense-backshifting (cf. Fauconnier 1985, Comrie 1986;

marked by means of different markers for the protasis, such as English when, in case of, and if (cf. Fillmore 1990, Grundy 2000: 120, Givon 2001: 324).

With regard to hypotheticality, Comrie (1986) makes a false claim that Mandarin makes no distinction in terms of degrees of hypotheticality, for there is not any device in verb tense that signals degrees of hypotheticality. It is true that Mandarin does not make distinctions in the auxiliary verbs and tense as English do, but it doesn’t follow that Mandarin has no way of making the distinction between different degrees of hypotheticality. Chao (1991: 55) mentions that Mandarin conditional markers are placed in the order of hypotheticality (from low to high) as follows: yaoshi 要是,jiaru 假如,ruoshi 若是,tangruo 倘若,jiaruo 假若,jiashi 假 使 ,tangshi 倘 使 ,sheruo 設 若 . Shiao (2005) also compares the degrees of hypotheticality of three Mandarin conditional structures: ‘Ruguo A, B’ (如果 A, B),

‘Ruguo A de-hua, B’ (如果 A 的話, B), and ‘A de-hua, B’ (A 的話, B). These studies suggest that Mandarin conditionals do distinguish degrees of hypotheticality, and the distinction is signaled mainly by the choice of different conditional conjunctions.

Taiwanese conditionals, like Mandarin conditionals, do not have any device in verb tense to signal degrees of hypotheticality. And from our analysis we find that degrees of hypotheticality in Taiwanese conditionals are, again like in Mandarin conditionals, reflected mainly by different conditional linking elements. In what follows, we will first examine all Taiwanese conditionals along the continuum of hypotheticality. Then we will discuss the correlation between different conditional structures (i.e. conditional linking elements) and different degrees of hypotheticality.

4.1 Continuum of Hypotheticality in Taiwanese Conditionals

Hypotheticality of one conditional sentence (consisting of p and q) refers to the speaker’s scalar certainty toward the factuality of p. When the speaker has higher

certainty toward the factuality of p, the conditional sentence carries lower degree of hypotheticality. On the contrary, when the speaker is less certain toward the factuality of p, the conditional sentence is of higher degree of hypotheticality. Thus, for the judgment of hypotheticality in one conditional sentence, the most important factor to be considered is ‘speaker attitude’, which may often be inferred from the context of the conditional sentence. In addition to the context, propositional meaning of the conditional sentence also helps to judge its hypotheticality.

Sperber and Wilson (1986), in their theory of relevance, argue that utterances come with a guarantee of their optimal relevance, which means that they present the message to the hearer in the way which ensures maximal communicative gain and at the same time minimizes the hearer’s processing effort. Hearers are therefore assumed to conduct their search for the most relevant interpretation by weighing what was said against what they already know.

The theory offers an elaborate account of inferential aspects of interpretation, set against a special understanding of the ‘context’. In most pragmatic theories, an interpretation of an utterance is arrived at by eliminating the ambiguities which are incompatible with the context and supplying contextually derived information where the utterance is vague or indeterminate (cf. Levinson 1983:47-53, Mey 1993: 9, 38, Thomas 1995: 1-14). Regarding context, Sperber and Wilson point out that in any discourse, the context in which a given utterance is processed is dynamically constructed for the purposes of processing this particular utterance. Such a notion of the context can be used in explaining both how speakers construct their utterances and how hearers interpret them, and it may in fact apply to all levels of message construction.

Naturally, the context most easily accessible to conscious analysis is that of the

stored in the short-term memory of the interlocutors. But the context may also contain the relationship between the interlocutors, and their encyclopedic knowledge related to the concepts occurring in the utterance to be interpreted.

A proper understanding of inference and context is necessary in accounting for hypotheticality of conditional sentences. In addition to context, the propositional frame of clause also sheds light on the examination of hypotheticality of conditional sentences.

One aspect of propositional meaning which may affect hypotheticality is the referential status of the participant NP. According to Givon (1993: 216), the participant NP of one proposition can be interpreted as referring or non-referring.

Under the scope of realis modalities, noun phrases can only be interpreted as referring;

while under the scope of irrealis modalities (such as conditionals), noun phrases may be interpreted as either referring or non-referring. When a noun phrase is interpreted as referring, the speaker uttering the NP has a specific reference in mind. On the other hand, when a noun phrase is interpreted as non-referring, the speaker has no particular reference in mind. Following the line, a non-referring NP tends to be more hypothetical than a referring one.

Hypotheticality of one conditional sentence also has to do with the status of the event in the proposition. A proposition specifying a specific event at a specific time is, in essence, cognitively more predictable/controllable (and hence less hypothetical) than a proposition which doesn’t specify a particular event at any particular time. This explains why the so-called ‘generic statements’ are classified as conditionals in irrealis scope by researchers (cf. Comrie 1986:83, Fillmore 1990:154, Dancygier 1998:63, Grundy 2000:130). Compare the following sentences:

(4.1) When I pressed its tummy yesterday, it squeaked.

(4.2) If/When/Whenever I press its tummy, it squeaks.

Example (4.1) is a realis assertion while example (4.2) is an irrealis one (or

‘non-assertion’). The difference is due to the status of the event—in example (4.1), a specific event at a specific time is identified; on the contrary, example (4.2) denotes a repeated occurrence of an event. This habitual-coded clause ‘I press its tummy’ is just as strongly asserted as a realis-coded assertion and thus shares an important pragmatic feature of realis. However, while a habitual (generic) assertion may be founded—as a generalization—on many events that may have indeed occurred at specific times, it does not assert the occurrences of any specific event at any specific time. Therefore, sentence (4.2) is irrealis-coded and regarded as a conditional sentence.

The last aspect of propositional meaning relating to the notion of hypotheticality is the occurring time of the propositional event. Future is by nature not knowable and not predictable. Thus, a future-tending proposition is less certain (more hypothetical) than a non-future-tending one.

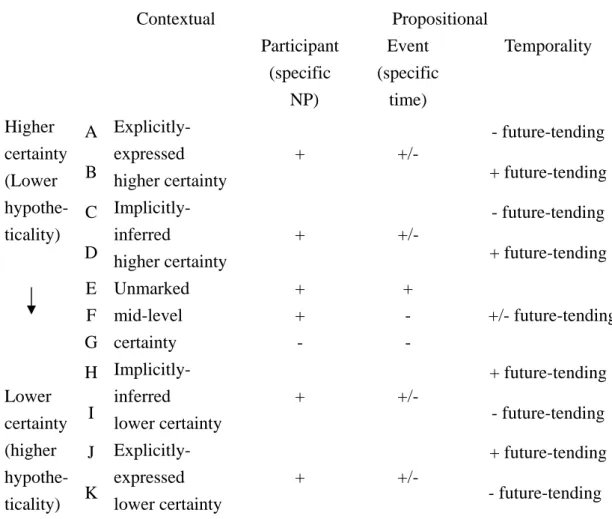

Utilizing the criteria discussed so far (‘context’ and ‘propositional meaning’ of the proposition), we differentiate Taiwanese conditionals in terms of hypotheticality.

The following table is the hypotheticality (epistemic certainty) scale for Taiwanese conditionals.

Table 4.1 Epistemic certainty scale for Taiwanese conditionals

Contextual Propositional

Participant (specific

NP)

Event (specific

time)

Temporality

A - future-tending

B

Explicitly- expressed higher certainty

+ +/-

+ future-tending

C - future-tending

D

Implicitly- inferred higher certainty

+ +/-

+ future-tending

E + +

F + -

G

Unmarked mid-level

certainty - -

+/- future-tending

H + future-tending

I

Implicitly- inferred

lower certainty

+ +/-

- future-tending

J + future-tending

Higher certainty (Lower hypothe- ticality)

Lower certainty (higher hypothe- ticality) K

Explicitly- expressed lower certainty

+ +/-

- future-tending

※ [+]: presence; [-]: absence; [+/-]: either presence or absence

Conditionals of contextually marked certainty (A-D and H-K) always contain particular participants, because without specific participants, the speaker cannot apply his/her judgment of the probability toward the propositions. Events, however, are not always specifically referred to. Conditionals with unspecified events are habit-coded.

For such conditionals (A-D and H-K), it is the temporality that crucially distinguishes degrees of hypotheticality. For instance, while both A and B are conditionals with speakers’ explicitly marked higher certainty, non-future-tending conditionals (A) are more certain than future-tending ones (B).

As for conditionals of contextually unmarked mid-level certainty (E-G), temporality of the propositions does not lead to difference in hypotheticality (since

speakers do not hold any assumption about the probability of the propositions, no matter whether the event is future-tending or not, the speakers simply have no idea about the probability of the propositions.) In conditionals of this type, it is the presence/absence of specific participants/events that helps to differentiate degrees of hypotheticality. For instance, conditionals with both specific participants/events (E) are more certain than conditionals with specific participants but non-specific events (F).

In what follows, we will present examples of Taiwanese conditionals in the order of degree of hypotheticality—from lower hypotheticality (i.e. higher speaker certainty) to higher hypotheticality (i.e. lower speaker certainty).

4.1.1 Explicitly-Expressed Higher Certainty

In this section we will present conditionals in which we find (from the co-text of a conditional) the speaker’s explicitly-expressed higher certainty toward the factuality of the protasis. In other words, these conditionals are of lower degree of hypotheticality.

The conditionals in examples (4.3) and (4.4) serve the function of topicalization.

That is, the conditional conjunctions function as topic-introducers (which can be translated into English ‘as for; when it comes to; if speaking of’), introducing entities whose existence is agreed upon by the speaker and the hearer in the prior text. In such cases, the factuality of the protasis is undoubted for the speaker.

Therefore, hypotheticality associated with such topicalizing construction is extremely low.

(4.3) ((matchmaker))

1. A: 好 矣, 免 閣 佇 彼 共 我 誘拐, ho a, bien koh ti hia ka goa yiukuai, ok UFP need-not again at there GOAL 1SG seduce 2. hng, 烏玫瑰,

hng, Ou-muikui, DM Black-Rose

3. 你 也 敢 出賣 我, haN, li a gaN chhutbe goa, haN, 2SG also dare betray 1SG UFP

4. 我 今仔日 一定 欲 予 你 好看!

goa kinajit itteng beh hou li ho-khoaN!

1SG today certainly want give 2SG good-look 5. B: e, 歹勢 hoN,

e, phaiNse hoN, DM sorry UFP

6. 我 毋 是 烏 玫瑰, goa m si Ou-muikui, 1SG NEG COP Black-Rose 7. 我 是 秦有緣 le.

goa si Chin-u-en le.

1SG COP Chin-u-en UFP 8. C: 無 毋著!

bo m-tioh!

NEG NEG-right

→9. 若 阮 姊仔, na gun chia, as-for 1PLE sister

10. 頂港 有 名聲, 下港 真 出名, teng-kang u miasiaN, e-kang chin chhutmia, northern-Taiwan have fame southern-Taiwan really famous 11. 大名 鼎鼎 的 萬能 媒人婆= 啊.

toa-beng tengteng e banleng moelangpo= a.

big-name well-known ASSC omnipotent matchmaker UFP

A(1-4): That’s enough, stop seducing me. Hng, Black Rose. You should dare to betray me? I will surely revenge on you today.

B(5-7): Eh, sorry. I am not Black Rose. I am Chin-u-en.

C(8-11): That’s right. As for my sister, she is famed in both northern- and southern-Taiwan as a matchmaker.

In example (4.3), A thinks B’s name is Ou-muikui (in line 2). B responds to A by telling A that she is not Ou muikui but Chin-u-ian (in lines 6 and 7). C, then, reinforces the validity of B’s utterance and emphasizes that B is actually very famous as a matchmaker. In line 9, C uses na to mark the NP gun chia, which refers to B.

The NP gun chia is the topic for the proposition in the following two lines (lines 10 and 11), which describes how famous gun chia is as a matchmaker. Na, therefore, functions to introduce an NP to serve as the topic for the following discourse. Since the existence of p (gun chia) is obviously confirmed by both interlocutors, the conditional protasis is of very low degree of hypotheticality.

(4.4) ((figure))

1. F: 我, 我 定 攏 講 你 矮 肥 短, goa, goa tiaN long kong li e pui te, 1SG 1SG often all say 2SG short fat short 2. 著 無? hoN?

tioh bo? hoN?

right NEG UFP

3. 啊 你, 你 勿愛 激到 彼號 面 啦, a li, li mai kek-kah hit-lo bin la, DM 2SG 2SG NEG anger-RES that-CL face UFP 4. 你 著 知影 講 hoN,

li toh chaiiaN kong hoN, 2SG just know COM UFP 5. 阿嫂 著 有 嘴 無 心,

Aso toh u chhui bo sim, Aso just have mouth NEG heart 6. 啊 其實 hoN,

a kisit hoN, DM in-fact UFP

7. 矮 肥 短 hoN, e pui te hoN, short fat short UFP

8. 啊 這 句 也 無 歹話 啊, a chit ku a bo phaiN-oe a, DM this-CL also NEG bad-word UFP

9. 著毋著?

tioh-m-tioh?

right-NEG-right 10. A: hng?

hng?

RT

11. F: e, 這 哪 有 歹話?

e, che na u phaiN-oe?

DM this how-come have bad-word

→12. 若 親像 這 款 體格, na chinchhiuN chit khoaN tehkeh, as-for like this type figure 13. 原仔 無 逐 口灶 有 的 呢,

goana bo tak khaochau u e ne, also NEG every family have NOM UFP

14. 這 也 原仔 著 你 hoN, 才 有 配合 le, che a goana toh li hoN, chiah u phoehap le, this also also just 2SG UFP then have match UFP 15. 著毋著?

tioh-m-tioh?

right-NEG-right

16. 配 你 的 身驅 , hoe li e sinkhu, match 2SG ASSC body

17. 啊 你 看 這個 面, a li khoaN chit-le bin, DM 2SG look-at this-CL face 18. 哎唷, 圓圓 偌 古錐 le.

aiiok, iN-iN loa kouchui le.

DM round-round so cute UFP

F(1-9): I often said that you are short and fat, right? But don’t be so angry at

hearing it. You have already known that I (your sister-in-law) always say what I don’t really mean. In fact, short-and-fat is not a bad word, is it?

A(10): What?

F(11-18): Hey, how could it be a bad word? As for/If speaking of this kind of figures, not everyone can have it. It is only you can have such a figure. Right?

Along with you body…look at this face, kind of round and so cute.

In example (4.4), F is trying to persuade A that A has a good figure. From lines 1-9, F has been talking about some characteristics of A’s figure. In line 12, after A’s interval response, F uses na to reintroduce the topic (about A’s figure) in order to continue her persuasion. Because the existence of the proposition in the protasis has been agreed upon by both the speaker and the hearer in the preceding discourse, hypotheticality of this conditional sentence is excessively low.

Conditionals like (4.3) and (4.4) are actually one kind of negotiation strategy in the discourse interaction, in which the speaker conveys the message ‘if we can take such-and-such as our topic’. This topicalizing function is not unique to Taiwanese conditionals. In fact, many typologists have noted connections between conditional and topic markers, and have suggested that if-clauses are functionally more topics than premises in many cases (cf. Haiman 1978, Traugott 1985, Schiffrin 1992, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005).

Topic-like conditionals are like ‘speech act conditionals’ discussed by many researchers (cf. Auwera 1986, Dancygier 1998, Sweetser 1990, 2005, Su 2004, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005) in that in such conditionals, the conditional space building is not to set up a basis for prediction but to give the appropriate setting for a speech act—to talk about a certain topic. That is, by employing a conditional to introduce a topic, the speaker is construing the discourse in a certain way—they thereby create such a context for an addressee. In doing this, the speaker is being

certain topics.

In examples (4.5)-(4.7) below, the protasis has been grounded in the preceding discourse by other interlocutors, and the speaker (of the conditional) accepts the factuality of that protasis. Such conditionals function mainly to mark the speaker’s epistemic distance to the protasis, but not to mark the speaker’s doubt toward the proposition.

(4.5) ((graduation ceremony))

(A father (B) is telling his son (A) on the phone that he is planning to attend the son’s graduation ceremony. The son, however, suggests his father not come. The father is very angry at his son’s refusal, because he takes the refusal as the evidence for his son’s being ungrateful to him)

>1. B: 飼 你 這個 死囡仔災, chhi li chit-e si-ginache, raise 2SG this-CL dead-child

>2. 無 啥物 路用.

bo siaNmih louiong.

NEG what use 3. A: 爸仔,你 勿愛 烏白想.

Pa-a, li mai oupeh-siuN.

Dad 2SG NEG groundlessly-think

>4. B: 自 細漢 共 你 liap 捏 到 這呢 大, chu sehan ka li liapni kah chiahnih toa, from little-child BENE 2SG look-after to this old

>5. 予你 讀冊.

hou li thakchheh.

let 2SG study

>6. 今仔日,人 講 我 通伯仔 好命, kinajit, lang kong goa Tong-peh-a homia, today people say 1SG Tong-peh-a happy

>7. 煞 予 阮 囡仔來 看無.

soa hou gun gina lai khoaNbo.

should PASS 1PLE child come look-down-upon

>8. 好! 你 敢 真正 對會起 你 的 良心?!

ho! li kam chinchiaN tuiekhi li e liongsim?!

DM 2SG can really conform-to 2SG ASSC conscience 9. A: 爸仔!你 勿愛 按呢, 我 哪 有

Pa-a! li mai anne, goa na- u Dad 2SG NEG like-this 1SG how-come have

這號 意思, chit-lo isu, this-CL intention

→10. 你 若 按呢 想, li na anne siuN, 2SG if this-way think

我 實在 毋知 欲 按怎 才 好.

goa sitchai m-chai beh anchoaN chiah ho.

1SG really NEG-know will what then good

B(1-2) : It’s a waste of effort for me to bring you up.

A(3) : Dad, don’t guess groundlessly.

B(4-8 ): I have been taking good care of you since you were a little baby, and I have let you have a education. Everybody says it’s time for me to enjoy my life now. But I should be looked down upon by you. Is your conscience clear in saying this?

A(18-19): Dad, don’t say that. I didn’t mean it. If you think in this way, I really don’t know what to do.

In example (4.5), the son says (in line 10) that if his father believes him to be disobedient, then he really doesn’t know how to defense himself and has no idea what to do. What’s worth noting in line 10 is the presence of the conditional marker na.

From the context, we know the father does consider his son to be ungrateful. However, it is a fact communicated by the father himself, but not by the son. The son, as an external observer, cannot enter into the inner world of his father’s consciousness.

Since the assumption is not known to the son directly, he then uses na to mark his epistemic/evidential distance to the assumption. Nevertheless, the proposition in the

information in the protasis to be factual. Therefore, the conditional protasis is of very low degree of hypotheticality.

(4.6) ((breathing problem))

1. C: --按呢, 啊 有當時仔 著 按呢, anne, a utangsia toh anne, like-this, DM sometimes just likethis,

2. 干單 按呢, 若 欲 喘氣 hoN, 喘 勿會 起來, kanta anne, na beh chhoan-khui hoN, chhoan boe khilai, only like-this, like want breathe-air UFP, breathe NEG up 3. 啊 我 著 用 哈唏 的 hoN--

a goa toh iong hahhi e hoN-- DM 1SG then use yawn NOM UFP-- 4. A: 是,

si, COP

5. C: -- 來 做 喘氣, 來 做 按呢.

-- lai cho chhoan-khui, lai cho anne.

come for breathe, come for like-this 6. A: haN.

haN.

RT

7. C: 有當時仔 哈唏 哈 一個 兩個, utangsia hahhi ha chit-e nng-e, someimes yawn yawn one-CL two-CL 8. 猶閣, 彼個 氣, 猶閣 挽 勿會 起來,

iakoh, hit-le khui, iakoh ban boe khilai, still that-CL breath still take NEG up, 9. A: 是.

si.

COP

10. C: 啊 所以這 是 按怎 haN?

a soui che si anchoaN haN?

DM so this COP what UFP?

→11. A: 你 準若 按呢 hoN, -- li chun-na anne hoN, -- 2SG if-if like-this UFP

12. C: heN.

heN.

RT

13. A: -- eN, 這 可能 是 有, 有 足 濟 款 hoN, -- eN, che kholeng si u, u chiok che khoaN hoN, DM this probably COP have have very many type UFP 14. C: haN, haN.

haN, haN.

RT RT

C(1-3): Like this…, sometimes it’s like this…just like this…if I wanna breathe but cannot make it, then I yawn.

A(9): Yes.

C(10): So what’s this all about?

A(11): If you are like this,-- C(12): Yeah.

A(13): --it may be caused by lots of reasons.

C(14): Hm, hm.

In example (4.6), an audience C is consulting a medical doctor A through a radio call-in show. After listening to C’s description of his/her breathing problem, A regards C’s description as a fact, and makes some diagnoses based on this fact. Though A accepts the factuality of C’s description, A is not a direct experiencer of the breathing problem. That is, C’s personal experience cannot be gone through by A directly. As a result, line 11, the conditional marker chun-na is used to mark A’s evidential/epistemic distance to the proposition initiated by C.

(4.7) ((worry))

1. M: 這 你 放心 啦.

che li hongsim la.

this 2SG feel-relieved UFP

2. 我 共 伊 看, goa ka i khoaN, 1SG THE 3SG see

畚掃仔 伊 毋 是 這種 人 啦.

Pun-so-e i m- si chit-chiong lang la.

Pun-so-e 3SG NEG-COP this-type people UFP

3. 伊 彼呢仔 忠厚,

i hiahniha tionghou, 3SG that kind

4. 彼呢仔 老實 著 hoN, hiahniha lausit toh hoN, that honest ASP UFP 5. 伊 勿會 做 歹 代誌 啦.

i be cho phai taichi la.

3SG NEG do bad thing UFP

>6. K: 唉! 嘛是 閣 淡薄仔 煩惱 le.

ai! ma si koh tampoha hoanlo le, DM also COP still a-little worry UFP 7. 做 一寡 歹 代誌 是 勿會要緊 啦,

cho chitkoa phai taichi si be-iaukin la, do some bad thing COP NEG-matter UFP

8. 也 毋閣 hoN, 會 去 害著 彼 兩個 囡仔 啊.

ia mkoh hoN, e khi haitoh hit nng-e gina a.

also but UFP will go harm that two-CL child UFP 9. M: m= 阿嫂, 啊 旦 這 毋 卡 簡單,

m= Aso, a taN che m khah kantan, DM sisiter-in-law DM now this NEG more easy

→10. 假使講 你 若是 勿會 放心, kasu-kong li na si be hongsim, if-say 2SG na COP NEG feel-relieved 11. 你 也 勿會曉 親身 去 調查.

li ia be-hiau chhinsin khi tiaucha.

2SG also NEG-know personally go investigate

M(1-5): You don’t have to worry about this. In my opinion, Pun-so-e is not that kind of person. He is so kind and honest that he would not do anything bad.

K(6-8): Sigh. I am still worrying about it. It didn’t matter too much for him to do something bad, but it would do harm to the two children.

M(9-11): Sister, this is very easy. If you are really worrying about it, you can go investigate the whole matter personally.

In example (4.7), M and K are talking about a guy called pun-so-e. M (from line 1to line 5) says that the guy is always very kind and sincere, so she believes the guy didn’t do anything bad. K, on the other hand, cannot be sure whether or not the guy did something bad. M, in response to K’s doubt, tells K in lines 10 and 11 that if K is really worried about the guy’s deeds (as K herself says), she can go investigate the truth in person. Lines 10 and 11 constitute one conditional sentence, in which line 10 is the protasis containing the conditional marker kasu kong…na si and line 11 is the apodosis which is not marked with a backward-linking element. In this case, M accepts the factuality of the contextually given p, and the main function of the conditional construction is to mark her epistemic distance to p.

The conditionals in the following examples (4.8)-(4.10) differ from the conditionals in (4.5)-(4.7) only in one aspect—the temporality of the propositional event. While conditionals in (4.5)-(4.7) are non-future-tending, conditionals in (4.8)-(4.10) are future-tending. As we mentioned in the previous discussion, future is by nature unpredictable and uncontrollable. As a result, conditionals in (4.8)-(4.10) are comparatively more hypothetical than conditionals in (4.5)-(4.7).

(4.8) ((stocks)) 1. A: 阿媽,

A-ma, Grandma

2. 彼-- 啊 彼 也 已經 慣勢 慣勢 矣, he -- a he ia ikeN koansi koansi a, that DM that also already get-used-to get-used-to CRS

3. 起 起 落 落 啊, 慣勢 慣勢 矣.

khi khi loh loh a, koansi koansi a.

up-up-down-down UFP get-used-to get-used-to CRS 4. B: heN,啊 這碼--

heN, a chitma-- RT DM now

>5. C: 應該 是 會 起 啦, 我 感覺 會 起.

engkai si e khi la, goa kamkak e khi.

supposedly COP will up UFP 1SG think will up 6. B: --那 彼擺 講 teh 起 矣, teh 起 矣.

-- na hit-bai kong teh khi a, teh khi a.

like that-time say ASP up CRS ASP up CRS

→7. C: 明仔朝起 一 開盤 一 起, bina-chaikhi chit khui-poaN chit khi, tomorrow-morning as-soon-as open-quotation as-soon-as up 8. 彼 teh 亂 的 人

he teh loan e lang that ASP protest NOM people

著 逐家 攏 走 返去 上班 啦 @@

toh takke long chau-tngkhi siongban la. @@

then everyone all go- back work UFP

A(1-3): Grandma, we have kind of gotten used to it. The price is always up and down, and we have gotten used to it.

B(4): Right. And this time--

C(5): The price is supposedly to go up. I think it will go up.

B(6): --is like last time that everybody said it was going up…it was going up.

C(7-8): If the price goes up as soon as the stock market opens, then the protesters will go back to work.

In example (4.8), three family members (the mother (A), the son (C), and the grandmother (B)) are talking about the price fluctuation in the stock market. Note in line 5, C says that he believes the price will go up. The irrelais-inducing epistemic adverb engkai indicates that though the proposition ‘e khi’ is not yet a fact in the real world, C is quite certain about the realization of that proposition in the future.

Therefore, we can infer from line 5 to know that in the conditional sentence (lines 7

and 8), C’s is certainty toward the protasis (line 7) is relatively high. In this conditional sentence, the protasis is unmarked, but the apodosis is marked by toh.

(4.9) ((gold watch))

1. A: 你 愛 知 呢.

li ai chai ne, 2SG have-to know UFP >2. e, 彼, 連鞭 hoN,

e, he, liammi hoN, DM that later UFP

>3. 恁 hoN, 小妹仔 著 欲 嫁 予 lin hoN, sio-moea toh beh ke hou

2PLE UFP little-sister just will marry PASS 彼 啥物 阿啄仔 呢,

he siaNmih atoka ne, that what foreigner UFP …(ellipsis of twenty-four lines)

28. 我 會記得 hoN, 阿爸 彼 hoN, goa ekittit hoN, A-pa hia hoN, 1SG remember UFP father there UFP

29. 假若 閣 有 一 骨交 金錶 佇-le o?

kahna koh u chit kha kim-pio ti -le o?

seem still have one-CL gold-watch at-ASP UFP 30. 彼, 這粒 金錶 hoN,

he, chit-liap kim-pio hoN, that this-CL gold-watch UFP

31. 我 若 無 想 辦法 共 提 過來, goa na bo siuN panhuat ka the koelai, 1SG if NEG think way SOU take come 32. 到時 hoN,

kau-shi hoN, to-time UFP

→33. 恁 小妹仔 若 嫁 予 <E David E>, lin sio-moea na ke hou <E David E>, 2PLE little-sister if marry PASS David

34. 啊 閣 當做 嫁粧, 閣 佮 予 伊, 哇, a koh tongcho kechng, koh kah hou i, oa, DM again as dower again take PASS 3SG wow 35. 按呢 毋 煞 閣 no-sut 去 矣?

anne m soa koh no-sut khi a?

this-way NEG should again NEG-eat go CRS

A: You have to know that your sister is going to marry that foreigner soon….I remember that your father has a gold-watch. That gold-watch will be given to your sister if I don’t take it now. In that case, we will have no chance to get the watch.

In example (4.9), it has been known to A that the sister-in-law will marry David in the future (lines 2 and 3). Therefore, the proposition lin sio-moea ke ho <E David E> in line 33 is predicted and anticipated by A. In this conditional, the protasis is marked by na, and the apodosis is unmarked.

(4.10) ((DPP committee member))

>1. A: 這個 每 禮拜四 hoN, chit-le mui lepaisi hoN, this-CL every Thursday UFP 2. E: hng.

hng RT

>3. A: 拜四 下朝仔 hoN, paisi echaia hoN, Thursday morning UFP 4. E: hng.

hng.

RT

>5. A: 咱 會 請 洪 常委 啊-- lan e chhiaN Ang siongui a -- 1PLI will invite Ang member UFP 6. E: hng.

hng.

RT

>7. A: --來 上 咱 的 節目, -- lai siong lan e chiatbok, come join 1PLI ASSC show

>8. 來 報告 中常會-- lai boko tiongsionghoe—

come report regular-meeting 9. E: ho.

ho.

RT 10. A: --hoN?

-- hoN?

UFP

>11. 民進黨 中常會 的 代誌.

Binchintong tionngsionghoe e taichi.

DPP regular-meeting ASSC thing 12. E: ho.

ho.

RT

→13. A: 啊 伊 若 拜四 下朝 來 的 時, a i na paisi echai lai e si, DM 3SG if Thursday morning come NOM time 14. E: hng.

hng.

RT

15. A: 啊 你 有 啥物 問題, a li u siaNmih bunte, DM 2SG have what question

16. 對 民進黨 有 啥物 建議, tui Binchintong u siaNmih kiangi, to DPP have what suggestion 17. E: hng.

hng.

RT

18. A: 啊 民進黨 做 啥物 代誌, a Binchintong cho siaNmih taichi, DM DPP do what thing

19. hoN?

hoN?

UFP 20. E: hng.

hng.

RT

21. A: 啊 彼個 時間 上 好, a hit-e sikan siong ho.

DM that-CL time most good

A(1): Well, every Thursday…

E(2): Hm.

A(3): Thursday morning…

E(4): Hm.

A(5): We always invite Mr. Hong…

E(6): Hm.

A(7-8): to be on our show to report about the regular meeting…

E(9): Oh.

A(10-11): the matters discussed in the regular meeting of DPP.

E(12): Oh.

A(13): If/When he comes this Thursday morning, E(14): Hm.

A(15-16): no matter what questions or suggestions you have for DPP…

E(17): Hm.

A(18-19): or you are wondering about what DPP has done…

E(20): Hm.

A(21): That is the best time (for you to ask questions and give suggestions).

In example (4.10), A is the host of a radio call-in show and B is the audience calling in to ask some questions. This is the end of the conversation. In order to stop E from asking more questions, the host A suggests E call again on the coming Thursday. A tells E that one of the DPP committee members, Mr. Hong, is on the show every Thursday (lines 1,3,5,7,8, and 11). So as a customary practice, Mr. Hong will attend the show on this coming Thursday. In line 13, A uses the conditional marker na…e si to mark paisi echai (i) lai as a proposition whose factuality is anticipated.

4.1.2 Implicitly-Inferred Higher Certainty

In the following conditionals, speaker’s marked higher certainty is inferred from the broader context (such as the physical context of the utterance, or the interlocutors’ encyclopedic knowledge), rather than obtained from the co-text. Since speaker’s certainty is implicitly inferred rather than explicitly obtained, such conditionals are thus of relatively lower certainty than the ones discussed in the previous section.

In conditionals in examples (4.11) and (4.12) below, the speakers are describing non-future-tending habitual experience, i.e. the protases refer to a particular participant but do not specify a specific event. Since habitual experiences are based on many events that may have indeed occurred at specific times, we can implicitly infer from speaker’s knowledge that they hold higher certainty toward the protases.

(4.11) ((newspaper))

→1. C: 啊 若, 以早 我 若 看 報紙, a na, icha goa na khoaN pochoa, DM if before 1SG if read newspaper 2. 別 人 著 掛 目鏡,

baklang toh koa bakkiaN , others just wear glasses

3. 我 攏 毋免 掛 目鏡, hoN.

goa long m-bien koa bakkiaN, hoN.

1SG all NEG-need wear glasses UFP 4. A: haN.

haN.

RT

5. C: 我 著 有 法度 通 看 報紙, goa toh u huattou tong khoaN pochoa, 1SG then have way can read newspaper

6. 到 這碼 我 嘛 仝款 是 毋免 掛 目鏡, kah chitma goa ma kangkhoan si m-bien koa bakkiaN, to now 1SG also same COP NEG-need wear glasses 7. 有 [法度] 通 看 報紙, hoN, --

u huattou tong khoaN pochoa, hoN, -- have way can read newspaper UFP 8. A: [是,] 是.

si, si.

COP COP

9. C: --按呢, 啊 這碼, hoN, 報紙 啊-- -- anne, a chitma, hoN, pochoa a -- -- like-this DM now UFP newspaper UFP 10. A: aN.

aN.

RT

→11. C: --大字 的 看 hoN, -- toa-ji e khoaN hoN , big-word NOM read UFP

大字 的 看 頭殼 勿會 痛, toa-ji e khoaN thaukhak be thiaN, big-word NOM read head NEG ache

→12. 細字 的 若 認真 共 看 oN, se-ji e na jinchin ka khoaN oN, small-word NOM if seriously THE read UFP 13. 啊 頭殼 著 痛 起來, 按呢.

a thaukhak toh thiaN khilai, anne.

DM head then ache up like-this

C(1-3): Whenever I read the newspaper before, other people had to wear glasses, but I didn’t have to.

A(4): Hm.

C(5-7): I could read the newspaper clearly. I still can read the newspaper without wearing glasses nowadays.

A(8): Right, right.

C(9): Like this.. now.. the newspaper…

A(10): Hm.

C(11-13): If/Whenever I read big words, I don’t have a headache. But if/whenever I read small words seriously, I have a headache.

Example (4.11) is a snatch of talk from a radio call-in show. The audience A is telling the doctor B about his eye-problem. To describe his symptom, A contrasts his past experience of reading newspapers with the present experience. In line 1, A reports his past habit by a conditional sentence (marked by a forward-linking element na). In line 12, the same conjunction na is used to depict his present experience of reading the newspaper. Another conditional is found in line 11. In line 11, there is no lexical conjunction; rather, the two propositions toa-ji e khoaN ‘reading large characters’ and thaukhak be thiaN ‘not having headaches’ are simply juxtaposed, with the protasis placed before the apodosis.

(4.12) ((mahjong game))

(B is asking G whether it is the case that whenever there is not enough people for a mahjong game, G’s friends would call him to join the game.)

1. B: 阿偉, 又閣 teh <M 三 缺 一 M> 矣 hio?

A-ui, iukoh teh <M san que yi M> a hio?

A-ui again ASP three lack one CRS UFP …(ellipsis of four lines)

6. B: 是毋是 人 若 欠 著 揣 你?

si-m-si lang na khiam toh chhoe li ? COP-NEG-COP people if lack then call 2SG …(ellipsis of four lines)

→11. G: 有 時間 才 有, u sikan chiah u, have time then have →12. 啊 無 時間 著 無.

a bo sikan toh bo.

DM NEG time then NEG

B(1): A-ui, there are not enough people for a mahjong game again?

...

B(6): Is this the case that if there are not enough people, they would call you?

G(11-12): I only go if I have time. I don’t go if I don’t have time.

In example (4.12), the aunt (B) asks her nephew (G) if it is the case that whenever there is not enough people for a mahjong game, G’s friends would call on G to join the game (line 6). In other words, B is asking about G’s habit. The proposition in the protasis is lang khiam ‘there is not enough people’ and the proposition in the apodosis is (lang) chhoe li ‘(they) call on you’. The two propositions are conjoined by na. In answering this question, G utters two conditionals in lines 11 and 12. The two conditionals are unmarked in the protases, but marked with backward-linking elements—chiah and toh, respectively. In these two conditionals, G is describing his personal experience, and therefore we implicitly infer that G has higher certainty toward the protases.

The conditional in the following example (4.13), like the conditionals in (4.11) and (4.12), refers to a particular participant but does not specify a specific event. We can also implicitly infer from the context the speaker’s higher certainty toward p.

However, while the conditionals in (4.11) and (4.12) are non-future-tending, the conditional in (4.13) is future-projecting. Therefore, by comparison, the conditional in (4.13) is of relatively lower certainty/higher hypotheticality than the conditionals in (4.11) and (4.12).

(4.13) ((nob))

1. O: haN? 你 是 畚掃仔?

haN? li si Pun-so-e?

DM 2SG COP Pun-so-e 2. F: hng.

hng.

RT

3. O: 哇! 喔, oa! o wow UFP

4. 穿 到 這呢 媠 喔?

chhneg kah chiahnih sui o?

wear to this beautiful UFP 5. F: hng hng.

hng hng.

RT RT

6. O: e, 你 哪會 變 按呢 haN?

e, li na-e bien anne haN?

DM 2SG how-come change like-this UFP 7. F: hng, 我啥物 le 變 按呢?

hng, goa siamih le bien anne?

DM 1SG what ASP change like-this 8. 這碼 身份 無 仝 矣.

chitma sinhun bo kang a.

now status NEG same CRS

→9. 若欲 叫 我 的 名,

na beh kio goa e mia, if want call 1SG NOM name 10. 後壁 攏 加兩 字 員外.

aupiah long ka nng ji goangoe.

end all add two word sir

O(1): What? You are Pun-so-e?

F(2): Right.

O(3-4): You are dressed so beautiful.

F(5): Hm, hm.

O(6): How come you become like this?

F(7-10): What are you talking about? I am a changed person of a higher status now.

If you want to call me, add ‘Sir’ after my name.

In this example, F is a person who gets rich suddenly. In order to show his dignity, he requests others to address him with a respectful form ever after. We infer from the context that F’s encyclopedic knowledge (that people do address others) and his

personal experience (that people did call him by his nickname) make him quite sure that people will address him in the future. In this conditional sentence, the protasis is marked with na, and the apodosis is unmarked.

4.1.3 Unmarked Mid-level Certainty

The majority of conditionals in our data are of mid-level certainty on the certainty scale. In such conditionals, speakers do not express their marked certainty (higher or lower) toward the protasis. That is, we cannot infer from the context (co-text, or broader text such as speaker’s encyclopedic knowledge) speaker’s special certainty. However, these conditionals can still be further differentiated (in terms of degree of certainty) mainly by their propositional meaning.

(4.14) ((David))

1. D: 娥仔, 來, Ngou-e, lai, Ngou-e come

2. 無要 緊,

bo’ai kin, NEG matter 3. 你 老實 講,

li lausit kong, 2SG frankly say

4. 彼個 <M 大衛 M> 有 共 你 騎, hit-e <M Da-wei M> u ka li khia, that-CL David have THE 2SG ride 5. 共 你 按怎樣仔 無 啦?

ka li anchoaNiuNa bo la?

THE 2SG what NEG UFP

→6. 若有 hoN, na u hoN, if have UFP

7. 你 著 共 阮 兩個 老的 講, li toh ka gun nng-e lau-e kong, 2SG then GOAL 1PLE two-CL old-NOM say 8. 我 這聲 hoN,

goa chit-siaN hoN, 1SG this-time UFP 9. 著 叫 伊 娶 你.

toh kio i chhoa li.

then ask 3SG marry 2SG

D: Ngo-e(girl’s name), it’s ok. You tell me frankly. Did that David have sex with you?

Did he do anything to you? If he did, you just tell us. I will ask him to marry you.

In this example, D, the father, is asking his daughter about her love affairs. D has no idea whether her daughter has had sex with her boyfriend or not. In line 6, D makes a hypothetical assumption that they did have sex. In making the assumption, D does not hold any special belief (marked certainty) toward it. The conditional protasis is marked with na, and the apodosis marked with toh.

Note that in the preceding example, the conditional contains a particular participant and a specific event. For the conditional in the following example, the participant receives a referring interpretation, but there is no specific event specified.

As a result, though in both (4.14) and (4.15), we find speakers’ mid-level certainty, the conditional in example (4.15) is of relatively lower certainty than the conditionals in examples (4.14), due to the fact that (4.15) does not specify a particular event.

(4.15) ((unemployment))

1. H: e, e, 歹勢 hoN, e, e, phaise hoN, DM DM sorry UFP

2. 啊 這碼 著 公司 hoN teh 收編 啦, a chitma toh kongsi hoN teh siuphian la, DM now just company UFP ASP reduce UFP

3. 啊 骨交數 無 用 彼 濟, a khasiau bo iong hiah che, DM worker NEG use that many 4. 啊 thai 會 彼 抵好,

a thai- e hiah tuho, DM how-come that by-chance

5. 裁 也 裁, 抵好 去 裁著 你 啦.

chhai ia chhai, tuho khi chhaitoh li la.

fire also fire by-chance go fire 2SG UFP (ellipsis of nine lines)

15. 卓 先生,

Toh siansiN, Toh Mr.

→16. 以後 你 若有 啥物 困難 啊, iou li na u siamih khunna a, afterwards 2SG if have what difficulty UFP 17. 我 會當 幫助 你 的 能力 內 啊,

goa etang pangcho li e lenglek lai a, 1SG can help 2SG NOM ability inside UFP 18. 你 作 你 講 無要緊.

li cho li kong bo’ai kin.

2SG go-ahead 2SG say NEG-matter

H(1-6): Sorry, our company is reducing the number of the employees. We don’t need many workers. While we were firing employees, you were by chance one of the people who got fired. Don’t be angry about this.

H(15-18): Mr.Toh, if you have any financial difficulty afterwards, as long as I can help you, please feel free to tell me.

In this example, the employer (H) is trying to comfort the employee (F), who has been laid off. In line 16, H promises F that if (whenever) F has financial difficulties in the future, he can definitely feel free to ask him for help. H bears no particular assumption (marked higher or lower certainty) about whether or not F will confront difficulties. In this conditional, the protasis is marked with na, and the apodosis is unmarked.

In the conditionals in (4.16)-(4.17) below, there is not only no specific event specified, but also no particular participant referred. Accordingly, the conditionals in (4.16)-(4.17) are of lower certainty than the conditional in (4.15).

(4.16) ((traffic regulation))

1. A: 所以=我 希望 咱 咱 的 台灣 人民 hoN, soui =goa hibong lan lan e taioan jinbin hoN, so 1SG hope 1PLI 1PLI NOM Taiwan people UFP 2. 逐家 卡 遵守 法治,

takke khah chunsiu hoatti, everybody more follow rule

→3. 咱 若 暗時仔, lan na amsia, 1PLI if night

→4. 假使 講 若 拄著 紅燈, kasu-kong na tutoh ang-teng, if-say if run-into red-light

5. 咱 嘛 是 愛 擋 著 著 著 啦.

lan ma si ai tong toh toh tioh la.

1PLI also COP have-to stop just just right UFP 6. 人 彼 先進 國家 的 人民,

lang he sianchin kokka e jinbin, people that advanced country NOM poeple 7. 攏 是 按呢 著 著 啦.

long si anne toh tioh la.

all COP like-this just right UFP

A: So I hope we Taiwanese…everyone has to follow the rules. If we run into a red-light even late at night, we still have to stop the car. People in the advanced countries all do this.

In example (4.16), A, a host of a radio program, is telling his audiences to abide by the rules and the law. In the conditional sentence (lines 3-5), the speaker does not

markers na and kasu-kong-na; in the apodosis, there is no backward-linking element.

(4.17) ((flight))

→1. A: 飛行機 若 欲 起飛 的 時, huihengki na beh khiboe e si, airplane if will take-off NOM time

2. 你 安全帶 一定 愛 綁 予 好.

li anchoantoa itteng ai pak hou ho.

2SG seat-belt certainly have-to fasten RES well 3. 啊 你 的 這個 <M 椅背 M>,

a li e chit-e <M yi-bei M>

DM 2SG NOM this-CL sit-back, 4. 愛 phan 一下,

ai phan chite, have-to hold ASP

5. 予 伊 豎 直 的.

hou i su tit e.

let 3SG stand straight NOM

6. 按呢 才 勿會 影響 著 別人 的 安全.

anne chiah boe enghiong toh bat-lang e anchoan.

this-way then NEG affect ASP others ASSC safety 7. 猶閣有 的 是,

iakohu e si, also NOM COP

→8. 飛行機 欲 坐 的 時陣, huihengki beh che e sichun, airplane want take NOM time

9. 絕對 勿會使 佇 便所 內底 食薰, hoN?

choattui boe-sai ti piansou laite chiahhun, hoN?

absolutely NEG-can at toilet inside smoke UFP 10. 啊 佇 走道 的 中間,

a ti chauto e tiongkan, DM at aisle ASSC middle 11. 也 勿會用 e 食薰.

ia boe-ionge chiahhun.

also NEG-can smoke

12. 食薰 是 佇 le 後壁.

chiahhun si tile aupiah.

smoke COP at rear

13. 一般 攏 是 有 一個 <E smoking area E> , itpoaN long si u chhit-e <E smoking area E>, generally all COP have one-CL smoking area 14. 食薰 的 愛 去 彼 食.

chiahhun e ai khi hia chiah.

smoke ASSC have-to go there smoke

→15. 猶閣有 落 飛機 的 時陣, iakohu loh hui-ki e sichun, also get-off plane NOM time 16. 你 千萬 毋通 青狂.

li chhenban m-tang chheNkong.

2SG make-sure NEG-can rash 無 差 到 一點仔 時間.

bo chha kah chittiama sikan.

NEG differ to a-bit time

→18. 你 愛 等 到 飛行機 停 到 好勢 矣, li ai tan kah huihengki theng kah hose a, 2SG have-to wait to plane stop to well CRS 19. 你 才 起來 提 你 的 行李 落去.

li chiah khilai the li e hengli lohkhi.

2SG then get-up take 2SG ASSC luggage down

A: Whenever/If a plane is taking off, you have to fasten your seatbelt well. And you have to hold the sit-back a little bit to keep it straight. In this way, you won’t endanger others. Besides, whenever you are taking an airplane, you must not smoke in the toilet. And you cannot smoke along the aisle, either. Generally speaking, there is a smoking area at the rear of the plane, and you can only smoke there. In addition, if you are getting off a plane, make sure not to be rash. A little time doesn’t make differences. You have to wait until the plane has finally stopped, and then you can get up to take your luggage.

Example (4.17) is a scrap of talk occurred in a radio call-in show. A, the host of the show, is telling the audiences some matters needing attention when we are taking a

plane. There are in total four conditional protases—lines 1, 8, 15, 18. In all these protases, there is no particular participant and no specific event referred. In the first conditional (lines 1-6), the protasis is marked with na…e si, and the apodosis is unmarked. For the second conditional (lines 8-14) and the third conditional (lines 15-17), the protases are marked with …e si(chun), the apodoses are unmarked. In the last conditional (lines 18-19), the protasis is unmarked, and the apodosis is marked with chiah.

4.1.4 Implicitly-Inferred Lower Certainty

In the conditionals below, though the speaker does not overtly express his/her marked certainty toward the protasis, we nevertheless can implicitly infer the speaker’s marked lower certainty from the broader context other than the co-text, such as our encyclopedic knowledge. Conditionals of this kind are of comparatively lower degree of certainty (and thus higher degree of hypotheticality) than conditionals in which the speaker holds unmarked mid-level certainty.

(4.18) ((job))

1. A: 副總 娘仔, 咱 講 實在 的 啦.

hu-chong niua, lan kong sitchai e la.

vice-president wife 1PLI say honestly NOM UFP 2. 兩 項 代誌 同時 發生 hoN,

nng hang taichi tong-si hoatseng hoN, two CL thing same-time happen UFP 3. 難免 卓仔 伊 會 想 傷 濟 啦.

lanbien Toh-e i e siuN siuN che la.

unavoidable Toh-e 3SG will think too many UFP 4. 所以 hoN, 我 想 講 hoN,

soui hoN, goa siuN kong hoN, so UFP 1SG think COM UFP

5. 伊 毋知 會 足 切 阮?

i m chai e chok chhe gun?

3SG NEG know will very hate 1PLE 6. 這碼 我 看 hoN,

chitma goa khoaN hoN, now 1SG see UFP

7. 一定 是 切 死 矣.

itteng si chhe si a.

certainly COP hate dead CRS 8. B: heN 啊.

heN a.

right UFP

9. 冤仇 hoN, 愈 結 愈 深 啦.

oansiu hoN, lu kiat lu chhim la.

hatred UFP more accumulate more much UFP

→10. m=, 這碼 若 跳 落 溪仔水 攏 洗 勿會 清 矣 o!

m=, chitma na thiau loh kheachui long se be chheng a o!

DM now if jump into stream all wash NEG clean CRS UFP 11. A: 著 啦.

tioh la.

right UFP

12. 啊 所以講 hoN, a soui kong hoN, DM so COM UFP

13. 欲 拜託 副總仔 hoN, beh paithok hu-chonge hoN, want request vice-president UFP 14 勿愛 將 卓仔 辭 頭路 啦.

mai chiong Toh-e si thaulou la.

NEG DISP Toh-e fire job UFP

A(1-7): Vice President’s wife, frankly speaking, because these two things happened at the same time, no wonder Toh-e misunderstood it. So I am wondering whether he hates us or not. In my opinion, he must hate us very much.

B(8-10): That’s right. The hatred is accumulating. Now even if we drop into a stream, we cannot wash the hatred away.

A(11-14): Right. So we want to make a request to you—please don’t fire Toh-e.

In example (4.18), B, in line 9 and line 10, tells the manager’s wife that the hatred between the guy and them are getting so strong that even if A and B jump into a river, the hatred cannot be eliminated. In uttering line 10, B is actually being exaggerating.

Depending on his encyclopedic knowledge, B knows that it is unlikely for them to jump into a river, and therefore the protasis thiau loh kheachui is of quite low degree of certainty (high degree of hypotehticality). The protasis is marked with na, and the apodosis is unmarked.

(4.19) ((proposal))

1. B: 我 問 你 le, goa bun li le, 1SG ask 2SG UFP

2. 彼秋月 腹肚 底 彼個 囡仔 是毋是 he Chhui-goat pakto te hit-le gina si-m-si that Chhui-goat belly bottom that-CL baby COP-NEG-COP 你 的?

li e?

2SG ASSC 3. A: 是 啦.

si la, COP UFP

4. ia 毋閣 我 著 共 講 了 矣, ia mkoh goa toh ka kong liou a, DM but 1SG just GOAL say finished CRS 5. 我 叫 伊 去 提掉 著 無 代誌 矣.

goa kio i khi thehtiau toh bo taichi a.

1SG ask 3SG go abort then NEG problem CRS …(ellipsis of ten lines)

16 B: 恁 爸 teh 厝的 等 你 啦, lin ba teh chhue tan li la, 2PL father at home wait 2SG UFP 17 免 問 伊 啦,

bien bun i la, need-not ask 3SG UFP

18 欲 問 你 講, beh bun li kong, want ask 2SG COM

19 秋月 彼個 囡仔 是毋是 你 的 啦, Chhui-goat hit-le gina si-m-si li e la, Chhui-goat that-CL baby COP-NEG-COP 2SG ASSC UFP

→20 假使若 是 你 的, kasu-na si li e, if-if COP 2SG ASSC 21 伊 欲 講 hoN,

i beh kong hoN, 3SG want COM UFP

22 欲 叫 媒人婆 欲 去 提親.

beh kio moailangpo beh khi tehchhin.

will ask matchmaker will go propose-marriage

B(1-2): Let me ask you. Are you the father of the baby Chhui-goat is expecting?

A(3-5): Yes, but I have told her to do the abortion and everything would be fine.

…

B(16-22): Your father is awaiting you at home. You don’t have to ask him. (Actually), he wanted to ask you whether or not you are the father of Chhui-goat’s baby.

If you are, he says that he will ask a matchmaker to make an offer of marriage to Chhui-goat.

From the subject matter discussed in the example, along with the encyclopedic knowledge common to Taiwanese people in the early decades, we can implicitly infer the speaker’s lower certainty toward the protasis. Unwed pregnancy is regarded as a dishonor in the society. Therefore, the parents don’t want it to be true. This undesirability is reflected in the choice of the forward-linking element kasu-na, which expresses higher degree of hypotheticality. The correlation between hypotheticality and desirability is thoroughly discussed by Akatsuka (2002), who points out that

“natural language conditionals are an important device for encoding the speaker’s evaluative stance of desirability” (Akatsuka 2002: 323). The Japanese conditional

conditionals. The Taiwanese marker kasu-na in this example serves the same function as Japanese –tewa.

4.1.5 Explicitly-Expressed Lower Certainty

In what follows we will present conditionals in which the speaker explicitly expresses his/her lower certainty toward the protases. Since the marked lower certainty is expressed overtly, conditionals of this type are of relatively lower certainty than conditionals in which the marked lower certainty is inferred implicitly (as discussed in Section 4.1.4). Such conditionals can further be differentiated into two types in terms of certainty—unlikely but possible, and counterfactual.

(4.20) ((oath))

1. D: [我 . ] 我 拄仔 問 阿媽 講, goa. goa tua mng A-ma kong, 1SG 1SG just-now ask Grandma COM 2. eN=, 是 按怎 講 啥物 無 愛,

eN=, si an-na kong siaNmih bo ai, eN= COP how-come say what NEG like 3. 阿媽 講 啥物 有 啥物 讖詈,

A-ma kong siaNmih u siaNmih chhamloe, Grandma say what have what oath 4. 我 講 讖詈 是 啥,

goa kong chhamloe si siaN, 1SG say oath COP what

5. 伊 共 講, eN, 讖詈 著 是 講, i ka kong, eN, chhamloe toh si kong, 3SG GOAL say eN oath just COP COM 6. 以前 可能 有 娶 彼 姓 彼個=,

icheng kholeng u chhoa he siN hit-e=, before probably have marry that last-name that-CL >7. 尾仔 冤家 講,

beoa oanke kong, later fight say

>8. 後擺 阮 攏 勿會 娶 恁 姓 啥, oupai gun long boe chhoa lin siN siaN, afterwards 1PLE all NEG marry 2PL last-name what

→9. 娶 恁 姓 啥 的 我 著 絕 後嗣.

chhoa lin siN siaN e goa toh choat housu.

marry 2PL last-name what NOM 1SG then extinct offspring

D: I just asked Grandma why they don’t like (it). Grandma said something..something called ‘oath’. I asked what an oath is, and Grandma explained that the oath was taken because in the past, our ancestor probably married a girl whose last name was so-and-so. But eventually the couple had quarrels, and our ancestor said that from then on, our family wouldn’t marry girls whose last name was so-and-so. If we marry girls with that last name, we will have no offspring.

In example (4.20), the speaker D is explaining to another person why the men in their family don’t marry girls whose last name is so-and-so. The reason is that long time ago, their ancestors had quarrels with another family whose last name is so-and so.

Their ancestors thus took an oath that their descendants won’t marry girls with that last name (line 7). If any man in the family violates the oath, the family will have no offspring henceforth (line 9). From line 7 and the apodosis part goa toh choat housu in line 9, we can infer that D is quite certain that the proposition in the protasis chhoa lin siN siaN e won’t be true. In this conditional sentence, the protasis is unmarked and the apodosis marked with toh.

(4.21) ((fortune))

1. A: m, 我 嘛 是 無 啥 愛 相信 le.

m, goa ma si bo siaN ai siangsin le.

DM 1SG also COP NEG very will believe UFP

2. 你 勿會用得 講 干單 看 伊 穿 水 衫, li be-engti kong kanta khoaN i chheng sui saN, 2SG NEG-can COM only see 3SG wear beautiful clothing

3. 啊 戴 新 帽仔, 按呢 著 是 好額人.

a ti sin boa, anne toh si hogiah-lang.

DM wear new hat like-this then COP rich-people 4. e, 無 一定 hoN,

e, bo itteng hoN, DM NEG-certain UFP

5. 伊 這個人 愛 面子 le, i chit-le lang ai binchu le, 3SG this-CL person want face UFP 6. 你 無 聽 人 一句 講, 有無?

li bo thiaN lang chit ku kong, u bo?

2SG NEG hear people one-CL COM have-NEG 7. 十二月 屎桶 盡磅 拚,

chaplige sai-thang chinpong piaN, December shit-bucket all clear

8. 無定 伊 hoN 私奇 去 kheng kheng le, bo-teng i hoN saikhia khi kheng-kehng le, NEG-certain 3SG UFP personal-savings go gather-gather UFP

9. 去買 一塊仔 衫褲 作 面子 嘛 無 定著.

khi be chit-tea saN-kho cho binchu ma bo-tiaNtioh.

go buy one-CL clothes-pants for face also NEG-certain 10. L: m

m RT

11. M: 哎呀, 阿兄, 真 歹 講 呢.

ai-ia, A-hiaN, chin phai kong ne.

hey old-brother really hard say UFP

→12. 彼 hoN, 假使伊 若講 真正 無錢 hoN, he hoN, kasu i na kong chinchiaN bochin hoN, 3SG UFP if 3SG if say really poor UFP

>13. 哪 有 可能 講 hoN, na u kholeng kong hoN, how-come have possible COM UFP

>14. 像 管家 講 的 按呢, 穿 到 這呢 水?

chhiuN koanke kong e anne, chheng kah chiahnih sui?

like housekeeper say NOM this-way wear to this beautiful

15. L: 著 啊, 著 啊.

tioh a, tioh a.

right UFP right UFP

16. 我 有 聽講 hoN 最近, goa u thiaN-kong hoN choekin, 1SG have hear-say UFP recently

17. 欲 將 厝 hoN, 攏 翻 新 的 喔!

beh chiong chhu hoN, long hoan sin e o ! will DISP house UFP all change new NOM UFP 18. 足 有錢 的 款 喔!

chiok uchin e khoan o!

very rich NOM manner UFP

A(1-9): I still don’t quite believe it. You can’t say he is a rich guy only because you see him wear beautiful clothes and new hats. It’s not for certain. He is a man who thinks highly of the appearances. Haven’t you ever heard of one saying:

‘The shit-bucket is thoroughly cleaned in December.’ Maybe he just gathered all his personal-savings to buy new clothes and pants for the sake of his face/dignity.

L(10): Hm.

M(11-14): Hey, brother, it’s really hard to say. If he had been rich, it would be impossible for him, as the housekeeper said, to dress so well.

L(15-18): Yeah, yeah. I have heard that he is going to get the whole house repaired recently. It seems that he is really rich.

In example (4.21), A, L, and M are talking about a guy who seems to get rich suddenly. A doesn’t believe the guy can get rich in such a short time, so he assumes the guy looks better only in appearance. M, however, opposes to A’s speculation. M thinks the guy does get rich, because if the guy didn’t have much money, it would be impossible for him to dress so well (lines 13 and 14). From lines 13 and 14, we can infer that M thinks the protasis i chinchiaN bochin (line 12) to be unlikely. In this conditional, the protasis is marked by kasu.na kong, and the apodosis is unmarked.

(4.22) ((sarcoma))

1. A: [一般 ] 停經 以後, 咱 知影 是 這個 啊-- itpoaN thengkeng iau, lan chaiiaN si chit-e a-- generally menopause after 1PLI know COP this-CL UFP 2. C: heN.

heN.

RT

3. A: --這個 肉瘤 會 慢慢仔 消 入 去, 是 會 消.

--chit-e liokliu e banbana siau jip khi, si e siau.

this-CL sarcoma will slowly disappear in go COP will reduce 4. C: heN.

heN.

RT

5. A: 咱 希望 是 按呢 嘛.

lan hibong si anne ma.

1PLI hope COP like-this UFP 6. C: heN.

heN.

RT

→7. A: 啊 萬一 準若 講 無 消 的 時陣 [ hoN, a banit chun-na kong bo siau e sichun hoN, DM if if-if say NEG disappear NOM time UFP 8. C: [heN].

heN.

RT

9. A: 有 必要 著 卡 緊 處理掉 矣, hoN.

u pitiau toh kah kin chhuli-tiau a, hoN.

have necessity then more quickly take-away CRS UFP

A(1): Generally speaking, after the menopause, we know that-- C(2): Hm.

A(3): --that this sarcoma will slowly disappear. It will.

C(4): Yeah.

A(5): We hope it is like this.

C(6): Right.

A(7): If it should not disappear, C(8): Yeah.

A(9): it is necessary to take away the sarcoma.

In example (4.22), through a radio call-in program, a patient (C) is consulting a doctor (A) about her sarcoma. A in lines 1 and 3 tells C that the sarcoma is supposed to disappear after her menstruation ceases. However, in lines 7 and 8, A adds an additional remark that if the sarcoma does not disappear as expected, C has to go to the doctor to solve the problem. Lines 7 and 8 form a conditional sentence, in which line 7 is the protasis and line 8 the apodosis. These two propositions are conjoined by the conditional marker banit chun-na kong…e sichun. This conditional marker here functions to show the speaker’s marked lower certainty toward p, because from lines 1 and 3 we know clearly that the speaker believes the protasis bo siau is unlikely to be true. As for the apodosis, it is marked with toh.

In this example, the protasis is multiple-marked. This multiple-marking forward-linking element is employed not only to show the speaker’s strong low certainty toward the protasis, but also to express the speaker’s undesirability toward the protasis. Since the state of affairs in the protasis is undesirable to the hearer, the speaker chooses a highly-hypothetical conditional conjunction in order to show his sympathy for the hearer. Thus, the choice of linking element does not solely depend on the speaker’s certainty, but is also determined by the conversational effect the speaker wants to convey, such as being polite (cf. Su 2004, Dancygier and Sweetser 2005, Shiao 2005).

The conditional protases in the preceding three examples (4.20)-(4.22) are unlikely but still possible. The following conditional protases are of even lower certainty, compared with (4.20)-(4.22), because they are contrary-to-fact. Note that in the counterfactual conditionals, the propositions are always non-future-tending.

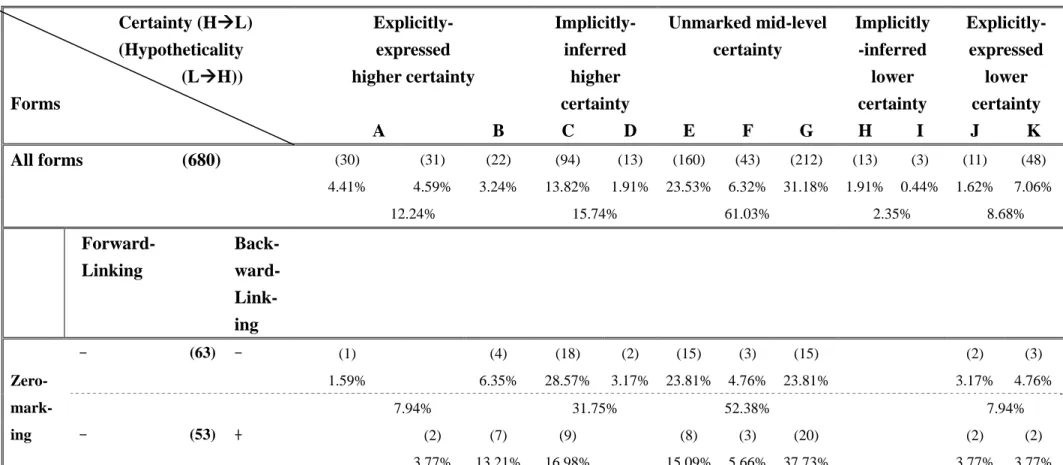

![Table 4.3 All forms VS. [-forward linking, -backward linking] VS. [-forward linking, +backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality Certainty (HÆL) Forms Explicitly- expressed higher certainty Implicitly- inferred higher certa](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/56.892.123.755.176.534/backward-continuum-hypotheticality-certainty-explicitly-expressed-certainty-implicitly.webp)

![Table 4.4 All forms VS. [-forward linking, +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality Certainty (HÆL) Forms Explicitly- expressed higher certainty Implicitly- inferred higher certainty Unmarked mid-level certainty Impl](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/57.892.125.758.173.452/continuum-hypotheticality-certainty-explicitly-expressed-certainty-implicitly-certainty.webp)

![Table 4.5 All forms VS. [na, +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality Certainty (HÆL) Forms Explicitly- expressed higher certainty Implicitly- inferred higher certainty Unmarked mid-level certainty Implicitly- inferre](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/58.892.127.756.174.424/continuum-hypotheticality-certainty-explicitly-expressed-certainty-implicitly-implicitly.webp)

![Table 4.6 All forms VS. […e si(chun), +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality Certainty (HÆL) Forms Explicitly- expressed higher certainty Implicitly- inferred higher certainty Unmarked mid-level certainty Implicitly](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/60.892.129.757.173.454/continuum-hypotheticality-certainty-explicitly-expressed-certainty-implicitly-implicitly.webp)

![Table 4.7 All forms VS. [na, +/-backward linking] VS. [ na kong, +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/61.892.123.754.411.746/table-forms-backward-linking-backward-linking-continuum-hypotheticality.webp)

![Table 4.8 All forms VS. [na, +/-backward linking] VS. [chun-na, +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/62.892.130.757.264.543/table-forms-backward-linking-backward-linking-continuum-hypotheticality.webp)

![Table 4.9 All forms VS. [kasu-na, +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality Certainty (HÆL) Forms Explicitly- expressed higher certainty Implicitly- inferred higher certainty Unmarked mid-level certainty Implicitly- in](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/63.892.129.757.173.453/continuum-hypotheticality-certainty-explicitly-expressed-certainty-implicitly-implicitly.webp)

![Table 4.10 All forms VS. [banit-na, +/-backward linking] in the continuum of hypotheticality Certainty (HÆL) Forms Explicitly- expressed higher certainty Implicitly- inferred higher certainty Unmarked mid-level certainty Implicitly-](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7257996.67100/64.892.128.757.173.454/continuum-hypotheticality-certainty-explicitly-expressed-certainty-implicitly-implicitly.webp)