No. 35, December 2007, pp. 113-145

Trajectory Patterns of Self-Rated Health among the Elderly in Taiwan:

A Comparison across Ethnicity

+Ho-Jui Tung

*+ Author's note: This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 94-2412-H-016-001), Taiwan. Data were taken from the Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan, provided by the Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Taiwan, ROC. Address correspondence to: Ho-Jui Tung, Ph.D., Department of Healthcare Administration, College of Health Science, Asia University, 500 Liufeng Road, Wufeng, Taichung County 41354, Taiwan E-mail: htung@asia.edu.tw

* Department of Healthcare Administration, College of Health Science, Asia University, Taiwan

Received: October 2, 2006; accepted: August 6, 2007

Abstract

This study seeks to compare health trajectories across the two major ethnic groups of the elderly in Taiwan, the Taiwanese and the Mainlanders, over 11 years of follow-up. This ethnic division is considered a salient dimension of social stratification in Taiwan, shaping the two groups of elders' pathways through life. Data are from the first four waves of the Taiwan Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly (N=3,540).

Proportional hazard models with time-dependent covariates and multinomial logistic regression were employed to compare health trajectories across ethnicity. There are three major findings. (1) Self-rated health is shown to be a remarkably strong predictor of mortality despite controlling for other variables, which is consistent with the bulk of studies in this area. (2) By using a national representative sample of the elderly in Taiwan and treating self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate, evidence from this study reveals that self-rated health reflects a person's health trajectory. (3) Considerable differences exist in the ways socio- structural forces are related to the health trajectories of Mainlanders and Taiwanese, respectively, over the 11 years of follow-up. In conclusion, it seems that, among this elderly population, the ethnic inequality in health can be explained away by Mainlanders' higher socio-economic standing, which is different from the racial/ethnic health disparities observed in the United States, where social class accounts for part of the differences, but the health disparities between African Americans and whites remain after adjusting for measures of social class.

Keywords: Taiwan, self-rated health, mortality, ethnicity, health trajectory, elderly.

I. Introduction

With the globally changing demographic structure, gerontology, the study of aging, has gained increasing attention worldwide. Moreover, in social gerontology, a growing body of literature has highlighted the influence of ethnicity, minority status, and social class on the aging process.

This study seeks to compare health trajectories across the two major ethnic groups of elders in Taiwan: the native Taiwanese1 and the Mainlanders (immigrants who moved from China's mainland to Taiwan around 1949 in the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War) over the 11-year period from 1989 through 1999. This ethnic division is considered a salient dimension of social stratification in Taiwan (Gates 1987), shaping the two groups' members' pathways through life. Data collected on this elderly population, who were born before 1929 and who have lived and grown old through a period of rapid social change, are analyzed in order to improve our understanding of how ethnicity and socio-structural variables are related to their health trajectories in their later lives.

(1) Ethnicity and aging studies in Taiwan

Many sociological studies examining the ethnic division between Mainlanders and Taiwanese have focused on comparisons of social mobility, inter-marriage, ethnic identity and assimilation, and voter mobilization (Chen 2005; Hu 1990; Tsai 1996; Wang 1993; Wu 1997, 2002). The reason that few studies have focused on the health status of

1 In this study, "Taiwanese" is used to refer to elders who were born in Taiwan. This study thus labels not only the Hoklo (Minnan) but also the Hakka as Taiwanese, although there are arguments that these two groups of Taiwanese differ culturally.

Mainlanders and Taiwanese elders is probably the lack of large-scale survey data. Because of a dramatic decline in total fertility in Taiwan and the expectation of a rapid transformation in age structure, more surveys regarding the health and living status of the island's elderly population have been collected. Among the studies that have made use of the data, Tung and Mutran (2005) compared two measures of health status (self-rated health and functional and disability status) between the Mainlander and Taiwanese elders, finding significant health disparities between the two groups of elders.

On the other hand, the study of old age in Taiwan has been dominated by scholars from the fields of public health and health services, in which population aging tends to be portrayed as a looming problem. The underlying assumption that drives the studies and interventions toward old age that older people are more vulnerable to chronic diseases and functional disabilities, which may lead to greater use of health services and, eventually, a greater likelihood of being institutionalized (Kaplan et al. 1993; Mor et al.

1994; Stuck et al. 1999; Verbrugge and Jette 1994). In the case of Taiwan, the transformation of its population structure over a relatively short period has led the study of old age in Taiwan to focus on the cost and burden attached to this demographic change (Wu and Chiang 1995). Less attention has been paid to documenting the ethnic patterning of health between Mainlander and Taiwanese elders. The current study is meant to fill this gap and to explain how membership in one of the two ethnic groups is related to group members' health trajectories over an 11-year period during their later lives.

(2) Life Course Perspective

Social gerontology stresses the diversity within elderly populations

and the influences of ethnicity and socio-structural forces on the aging process. Researchers in this area call for closer scrutiny of the considerable diversity, heterogeneity, and intra-cohort variability (Dannefer and Uhlenberg 1999; Dannefer 2003; George 1993) within the cohorts of people who share a collective social and historical circumstance. As Walker (1990) points out, "older people (like their younger counterparts) are divided more deeply among themselves, along social class and other lines than they are united by the simple fact of sharing a common age group" ( Walker 1990:

391).

Particularly, the life course perspective argues that aging occurs from birth to death as life transitions unfold and individuals enter and exit social positions and roles over the life course (George 1993, 2003; Elder 1991, 1994). Here, life course refers to "trajectories of role transitions and the social pathways followed over particular phases of life" (Alwin and Wray 2005). In current study, the two ethnic groups of elders, Mainlanders and Taiwanese, differ in one key feature: migration experience. The move of Mainlanders to the island of Taiwan in the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War can be seen as a social dislocation by which their normative sequences of life transitions or trajectories were disrupted. When the war came along, they were either drafted into the military or were forced to leave behind their community in the mainland. This is similar to situation studied by Ryder (1965); he compared the differences between American and European societies, in terms of societal changes. "America may be less tradition- bound than Europe because fewer young couples establish their homes in the same place as their parents" (Ryder 1965:851), he wrote. In light of the life course perspective, along with longitudinal data that follow people over time, researchers in this area have begun to address questions like "Does the linkage between socio-economic status (SES) and health change over

historical time?" "How can we identify different patterns of health trajectory?" And "How are social-structural factors related to older people's health trajectories over time?" So far, these lines of research have documented that health disparities either increase over the life course (House, Lantz, and Herd 2005; Mirowsky, Ross, and Reynolds 2000; Ross and Wu 1995) or persist in later life (House et al. 1994; Liao et al. 1999), because social advantages accumulate and compound to produce more heterogeneity and inequality in older age (Dannefer 2003; Ferraro 2006).

(3) Trajectory of health

Examining older persons' health trajectories over time usually involves some indicators of health over several measurement occasions, which requires a longitudinal panel design. The single item, "regarding your state of health, do you feel it is excellent, good, average, not so good, or poor,"

has proven a reliable predictor of mortality, even after controlling for numerous measures of physical health (Idler 1999; Strawbridge and Wallhagen 1999; Zimmer et al. 2000). It is also one of the most easily measured concepts in social sciences (George 2003). Research focusing on the link between this self-rated health measure and mortality also points out that the predictive value of this single item may lie in the explanation that people incorporate their health changes into their health ratings (Ferraro and Kelly-Moore 2001; Ferraro 2006), which means that self-rated health actually reflects a person's health trajectory (Idler and Benyamini 1997;

Wolinsky and Tierney 1998; Liang et al. 2005). More important, in several recent reports, researchers have also found that the self-rated health- mortality association may differ among age and gender groups (Bath 2003;

Benyamini et al. 2003; Deeg and Kriegsman 2003). In order to move the field forward, it becomes crucial to study the ways in which self-rated health

are derived and how they may differ across different social groups (Idler 2003). However, most of these studies have been conducted in industrialized countries; few have examined the situation in developing countries (Frankenberg and Jones 2004; Yu et al. 1998). The current study serves as an empirical test to address the following research questions. Is self-rated health reported by the two ethnic groups of elders in Taiwan predictive of their survival status 11 years later? If so, does self-rated health represent judgments of health trajectories? That is, do the elders incorporate health changes into the ratings of their own health? Are there differences in the self-rated health-mortality relationships across ethnicity? If findings from the previous analysis support a dynamic thesis of self-rated health, then the use of self-rated health to represent health trajectories is legitimized.

Finally, we know that all longitudinal surveys face the problems of panel attrition and potential selection effects (Ferraro and Kelly-Moore 2003). Consequently, the respondents' long-term and short-term survival statuses are included to identify six health trajectories among this elderly population. The final analysis deals with how ethnicity and other socio- structural variables are related to these health-trajectory patterns over the 11 years of follow-up.

II. Data and Methods

(1) Sample

Data for this study are from the first four waves of the Taiwan Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly, which is a panel-design longitudinal survey. A national representative sample of people 60 or older

in 1989 was drawn. Twenty-seven strata with roughly equal size were identified, stratified by three administrative levels (city, urban township, and rural township), three levels of education, and three levels of total fertility rate. Among the 4,412 persons selected for the survey, 4,049 responded, yielding a response rate of 91.8%. When the first follow-up occurred in 1993, 3,155 elders were successfully re-interviewed, with a response rate of 91.0% after excluding the deceased cases from the denominator. The next three follow-ups took place in 1996 (2,669 cases were retrieved, with a response rate of 88.9%), in 1999 (2,310 cases were re-interviewed, with a response rate of 90.1%), and in 2003 (2,036 cases were interviewed). Detailed descriptions of sampling and the questionnaire are provided elsewhere (Taiwan Provincial Institute of Family Planning 1989).

Because a major purpose of this study was to compare the health trajectories across the two ethnic groups of elders in Taiwan, Mainlanders and Taiwanese, we excluded 95 respondents who identified themselves as having "other" ethnicity. In addition, we also found that self-rated health was not available for proxy interviews, so another 137 cases with missing self-rated health at baseline were also excluded from the analysis. For the respondents who had their self-rated health recorded in the first wave but were found missing on this item in the follow-ups, an imputed value of self- rated health was assigned to them based on following principles: (1) if their second-wave measures were missing, these were replaced with an average of the first- and third-wave measures; (2) if their third-wave measures were missing, these were replaced with an average of their second- and fourth- wave measures; (3) if more than two waves of the measures were missing, then the cases were deleted. As a result, another 277 cases were deleted from the analysis. That left 3,540 cases available for this study; their

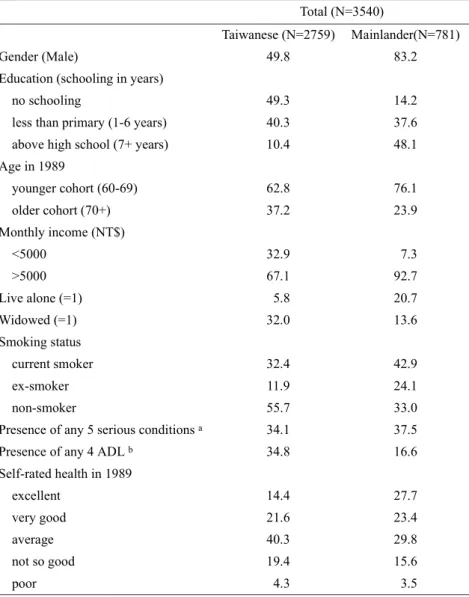

Table 1: Percentage Distribution of Sample Characteristics by Ethnicity Total (N=3540)

Taiwanese (N=2759) Mainlander(N=781)

Gender (Male) 49.8 83.2

Education (schooling in years)

no schooling 49.3 14.2

less than primary (1-6 years) 40.3 37.6

above high school (7+ years) 10.4 48.1

Age in 1989

younger cohort (60-69) 62.8 76.1

older cohort (70+) 37.2 23.9

Monthly income (NT$)

<5000 32.9 7.3

>5000 67.1 92.7

Live alone (=1) 5.8 20.7

Widowed (=1) 32.0 13.6

Smoking status

current smoker 32.4 42.9

ex-smoker 11.9 24.1

non-smoker 55.7 33.0

Presence of any 5 serious conditionsa 34.1 37.5

Presence of any 4 ADLb 34.8 16.6

Self-rated health in 1989

excellent 14.4 27.7

very good 21.6 23.4

average 40.3 29.8

not so good 19.4 15.6

poor 4.3 3.5

Note:ahypertension, cancer, diabetes, heart diseases, and stroke.

bdifficulties in walking, bathing, using the phone, and managing money.

characteristics are presented in Table 1.

(2) Measures

The survival status of the original 4,049 respondents was determined by cross-checking the death certificate registration system, which is managed by Taiwan's Cabinet-level Department of Health, and the household-registration system, which is maintained by Taiwan's Ministry of the Interior. For the deceased respondents, their dates of death (detailed in months) were obtained. Since mortality information was not available past December 1999, only the first four waves of the survey data were used.

Cases who were alive after December 1999 are treated as censored. Of the 3,540 original respondents interviewed in 1989, 1,427 (40.3%) had died by 1999.

The measurement of self-rated health is a single item, "Regarding your state of health, do you feel it is excellent (coded 1), good, average, not so good, or very poor (coded 5)." Thus, higher scores mean the perception of poorer health. This 5-category measure was used when examining the relationship between self-rated health and survival status over the 11-year period. It is argued that using the 5-category item and treating it as a continuous variable could prevent the coarseness involving collapsing the 5 categories into fewer responses. Plus, it would be more parsimonious when treating self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate (Ferrarro and Kelley-Moore 2001). However, in identifying trajectory patterns, the 5- category self-rated health was dichotomized into simply "good" (for excellent, good, and average) and "poor" (for not so good and very poor).

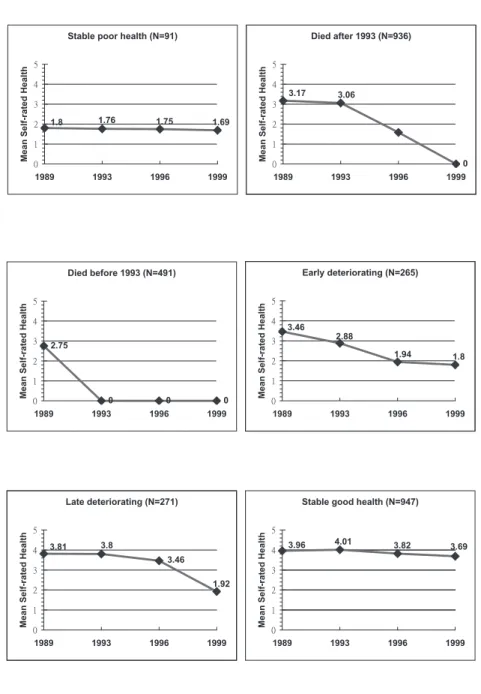

Based on transitions of self-rated health across waves and respondents' survival status, 7 major trajectory patterns were identified:

(1) stable poor health: those who survived the whole 11 years and rated

their health as "not so good" or "very poor" throughout the four wa- ves

(2) died later: those who died between 1994 and 1999 (3) died early: those who died before the end of 1993

(4) early deterioration: those who survived the whole observation per- iod and had a baseline self-rated health better than average, but who also declined into the "not so good" or "very poor" categories in the earlier waves

(5) late deterioration: those who survived the whole observation period and maintained an above-average self-rated health until the third wave, when it deteriorated into the "not so good" or "very poor"

categories for the last wave

(6) stable good: those who survived the whole 11 years and rated their health as excellent, good, or average through the four waves of the survey

(7) no clear pattern: those who survived the whole 11 years but had fluctuating ratings of self-rated health over the period; their com- parisons against the other trajectories are not the focus of this analysis.

Finally, it should be noted that for the purposes of illustration (see Figure 1) the original coding for self-rated health has been reversed, so that excel- lent=5 and "very poor"=1. In addition, another category was added: "dead"

(=0).

A variety of covariates, along with self-rated health, are included to predict the outcome variable. First, covariates centered on the mechanisms linking the Mainlander and Taiwanese elders' social position to their health status (Hayward et al. 2000) are included; these include gender, age, ethnicity, and measures of socio-economic status (SES). The significance of

Figure 1. The six trajectory patterns and their average self-rated health across waves.

ethnicity (Taiwanese=1; Mainlanders=0) has been discussed previously.

Gender (male=1 and female=2) and age are fundamental social relations and have both profound biological and social influences on health. Age was dichotomized into two cohorts: "younger" (aged 60 – 69 in 1989) and "

older" (aged 70 and over in 1989). Educational attainment (years of schooling) is also fundamental in reflecting an individual's childhood social class circumstances, shaping health behaviors (such as smoking), and increasing self-efficacy and sense of control (Ross and Wu 1995). Measure of educational attainment is collapsed into 3 groups (no schooling, less than primary school, and high school and above) in the multinomial logistic regression analysis. Higher income is associated with better access to health care and economic resources. Monthly income (including spouse's) in 1989 is measured by a seven-category item: less than NT$3,000 (=1), NT$3,000 to NT$4,999 (=2), NT$5,000 to NT$9,999 (=3), NT$10,000 to NT$14,999 (=4), NT$15,000 to NT$20,000 (=5), NT$20,000 to NT$49,999 (=6), and NT$50,000 and over (=7). This income information, however, was missing for 397 cases. Their income measures were replaced with the median incomes imputed from their gender and education-level groupings. These 7- category income measure are treated as continuous variables in the survival analyses, but were dichotomized (below or above NT$5,000) in the multinomial logistic regression.

The health-protection effect of social relationships is well documented (House, Umberson, and Landis 1988). In a society where informal care provided by families accounts for most of the care burden, support for the old often takes the form of living together. Another included indicator of social relationships is widowhood. Both of these are dichotomous measures, where 1 equals the name of the variables and 0 means all others.

A lifestyle health behavior measure is included as well. Dummy

variables are created to differentiate the elders' smoking status: one for the current smokers against all others, another for the past smokers against all others.

For health-related covariates, a measure of presence of any five serious conditions is used. In each wave of the survey, the respondents were asked,

"Has a doctor ever told you that you have hypertension, diabetes, heart problems, stroke, or cancer?" For each of the conditions, "yes" is coded 1, with other answers coded 0. Since the survey was conducted among community-dwelling elders, relatively few had these serious conditions; so we decided to collapse them further into one dichotomous measure (presence of any of the five conditions is coded 1, and freedom from all of these conditions is coded 0). Finally, functional status at baseline is assessed by a composite of 4 items (bathing, walking short distance, managing money, and using the phone) measuring both the difficulties of activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL).

Again, relatively few of these community-dwelling elders had any ADL or IADL disabilities, so they are collapsed into one dichotomous measure (presence of any of the four difficulties is coded 1, and freedom from all of the difficulties is coded 0).

III. Analysis

When examining the relationship between mortality and self-rated health, proportional hazard models for survival analysis are employed.

Several analyses were conducted to compare findings. First, respondents' baseline self-rated health (referred to as W1 in the tables) was entered, along with other risk factors, to predict mortality over the 11 years. Next, time- dependent self-rated health and serious conditions were introduced into the

models.

According to Allison (1995), there are several ways to implement the time-dependent covariates, most of which require some manipulation of the data structures. For our data, a major challenge is that self-rated health and other covariates were measured at four irregular intervals (at baseline, 1993, 1996, and 1999), which do not correspond to the unit of survival time (you can count how many months has lapsed or how many years has lapsed since the beginning). As a result, we have to take the most recent values and scale them by time of observation in years. In essence, a time stamp is placed on the most recent values, and related SAS codes are given to pick up the most recent measures for the two time-dependent covariates (self-rated health and serious chronic conditions). For the time-dependent measures in the years between waves, the most recent available measures are assigned to them. When the time-dependent covariates are incorporated, When the time-dependent covariates were incorporated, the dynamic thesis of self- rated health can be evaluated by comparing findings from models with and without time-dependent covariates. If older people do incorporate health changes into their health ratings, self-rated health should remain a significant predictor in these models. Indeed, one may expect that its association with mortality would be stronger.

Multinomial logistic regression is used to model the factors predicting different health trajectories over the observation period. When modeling the six health-trajectory patterns, the aim is to identify predictors differentiating those who had consistent good health from other health trajectories.

Accordingly, likelihood of other trajectories is modeled against that of consistent good health in the multinomial logistic regression analysis.

IV. Results

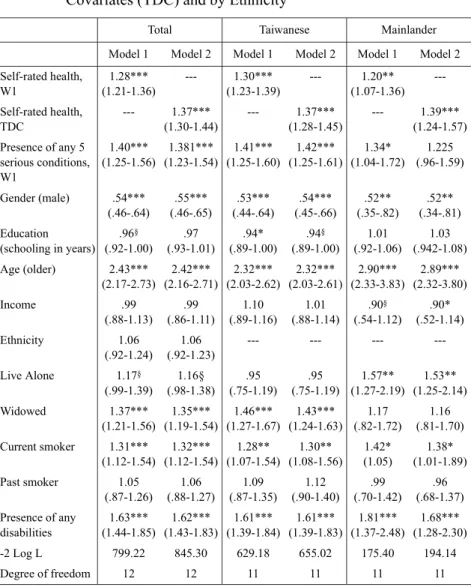

(1) Self-rated health-mortality relationship

The results of the baseline and time-dependent self-rated health analyses are presented in Table 2. Hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented for the total and separately for Mainlander and Taiwanese elders, where model 1 uses the baseline self-rated health and model 2 treats self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate (referred as TDC in the tables). From the first column of Table 2, we can see that baseline self-rated health is highly predictive of mortality over the 11 years.

The hazard ratio for this W1 self-rated health measure is 1.28, which means that, on average, the risk of mortality increases by 28% per single unit down the rating scale (1=excellent; 5=very poor). Presence of any of the five serious conditions and any of the four disabilities are also associated with higher mortality, as are gender, age, being widowed, and being a current smoker. Among SES indicators, education (years of schooling) is only modestly associated with mortality.

Although mortality does not differ across ethnicity, when controlling for other covariates, there are considerable differences in terms of which factors are more important in predicting mortality risk between Mainlander and Taiwanese elders. By comparing the second and third columns of Table 2, we see that education's health-protection effect is more pronounced for Taiwanese elders. On the contrary, it seems that income is more associated with mortality among Mainlanders in predicting mortality over the 11 years of follow-up. In terms of indicators of social relationships, widowhood is a strong predictor of mortality for Taiwanese elders but not for Mainlanders.

Table 2. Hazard Ratios and Confidence Intervals from Proportional Hazard Models of Mortality with and without Time-dependent Covariates (TDC) and by Ethnicity

Total Taiwanese Mainlander

Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Self-rated health,

W1

1.28***

(1.21-1.36)

--- 1.30***

(1.23-1.39)

--- 1.20**

(1.07-1.36) ---

Self-rated health, TDC

--- 1.37***

(1.30-1.44)

--- 1.37***

(1.28-1.45)

--- 1.39***

(1.24-1.57) Presence of any 5

serious conditions, W1

1.40***

(1.25-1.56)

1.381***

(1.23-1.54)

1.41***

(1.25-1.60)

1.42***

(1.25-1.61) 1.34*

(1.04-1.72) 1.225 (.96-1.59)

Gender (male) .54***

(.46-.64)

.55***

(.46-.65)

.53***

(.44-.64)

.54***

(.45-.66)

.52**

(.35-.82)

.52**

(.34-.81) Education

(schooling in years) .96§ (.92-1.00)

.97 (.93-1.01)

.94*

(.89-1.00) .94§ (.89-1.00)

1.01 (.92-1.06)

1.03 (.942-1.08) Age (older) 2.43***

(2.17-2.73)

2.42***

(2.16-2.71)

2.32***

(2.03-2.62)

2.32***

(2.03-2.61)

2.90***

(2.33-3.83)

2.89***

(2.32-3.80)

Income .99

(.88-1.13) .99 (.86-1.11)

1.10 (.89-1.16)

1.01 (.88-1.14)

.90§ (.54-1.12)

.90*

(.52-1.14)

Ethnicity 1.06

(.92-1.24) 1.06 (.92-1.23)

--- --- --- ---

Live Alone 1.17§ (.99-1.39)

1.16§

(.98-1.38) .95 (.75-1.19)

.95 (.75-1.19)

1.57**

(1.27-2.19)

1.53**

(1.25-2.14)

Widowed 1.37***

(1.21-1.56)

1.35***

(1.19-1.54)

1.46***

(1.27-1.67)

1.43***

(1.24-1.63) 1.17 (.82-1.72)

1.16 (.81-1.70) Current smoker 1.31***

(1.12-1.54)

1.32***

(1.12-1.54)

1.28**

(1.07-1.54)

1.30**

(1.08-1.56) 1.42*

(1.05)

1.38*

(1.01-1.89)

Past smoker 1.05

(.87-1.26) 1.06 (.88-1.27)

1.09 (.87-1.35)

1.12 (.90-1.40)

.99 (.70-1.42)

.96 (.68-1.37) Presence of any

disabilities

1.63***

(1.44-1.85)

1.62***

(1.43-1.83)

1.61***

(1.39-1.84)

1.61***

(1.39-1.83)

1.81***

(1.37-2.48)

1.68***

(1.28-2.30)

-2 Log L 799.22 845.30 629.18 655.02 175.40 194.14

Degree of freedom 12 12 11 11 11 11

Note: Values are hazard ratios (95% confidence interval). W1= Wave 1. TDC=Time-dependent co- variate.

§p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

To live alone is highly predictive of dying over the 11 years among Mainlander elders; this, however, is not seen among their Taiwanese counterparts.

When treating self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate, it is not only a significant predictor of mortality over the 11 years of follow-up; its effect is also much stronger. This stronger effect is seen for the total sample and for both of the sub-samples (Mainlander and Taiwanese). For example, looking at model 2 for the total sample, one-unit increase in self-rated health would lead to a 37% (HR=1.37) incease in morality risk over the 11 years of follow-up, with adjustments for socio-structural and SES variables as well as health-related risk factors. This provides evidence to support the thesis that self-rated health actually reflects a "dynamic, rather than static, perspective on health" (Idler and Benyamini 1997; Wolinsky and Tierney 1998; Ferraro and Kelly-Moore 2001). For the Taiwanese and Mainlander sub-samples, the pattern of significant findings is very similar across ethnicity. For Mainlander elders, however, when treating self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate (model 2), a notable difference between the two ethnic groups is found (in terms of the predictive value of the presence of any serious conditions related to mortality). That is, the association between the presence of any serious conditions and mortality disappears (model 2 for the Mainlander sub-sample) once including self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate.

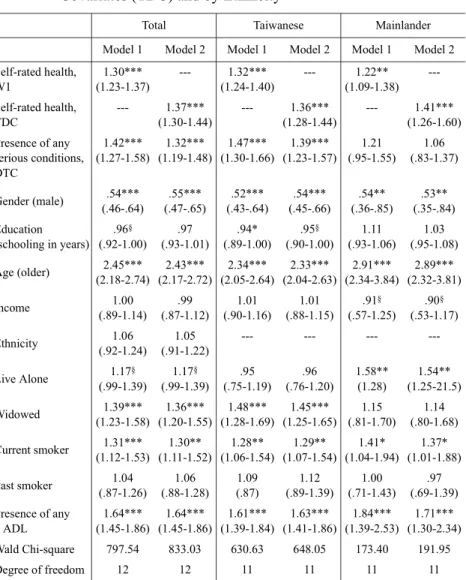

In Table 3, another time-dependent covariate, the presence of any serious conditions, is added to further evaluate the dynamic thesis of self- rated health. From Table 3 we see that, again, self-rated health is a significant predictor of mortality for the total sample and for both the Taiwanese and the Mainlander sub-samples. A striking difference between the two ethnic groups appears, however, when morbidity information is

Table 3. Hazard Rations and Confidence Intervals from Proportional Hazard Models of Mortality with Multiple Time-dependent Covariates (TDC) and by Ethnicity

Total Taiwanese Mainlander

Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Self-rated health,

W1

1.30***

(1.23-1.37)

--- 1.32***

(1.24-1.40)

--- 1.22**

(1.09-1.38) ---

Self-rated health, TDC

--- 1.37***

(1.30-1.44)

--- 1.36***

(1.28-1.44)

--- 1.41***

(1.26-1.60) Presence of any

serious conditions, DTC

1.42***

(1.27-1.58)

1.32***

(1.19-1.48)

1.47***

(1.30-1.66)

1.39***

(1.23-1.57) 1.21 (.95-1.55)

1.06 (.83-1.37)

Gender (male) .54***

(.46-.64)

.55***

(.47-.65)

.52***

(.43-.64)

.54***

(.45-.66)

.54**

(.36-.85)

.53**

(.35-.84) Education

(schooling in years) .96§ (.92-1.00)

.97 (.93-1.01)

.94*

(.89-1.00) .95§ (.90-1.00)

1.11 (.93-1.06)

1.03 (.95-1.08) Age (older) 2.45***

(2.18-2.74)

2.43***

(2.17-2.72)

2.34***

(2.05-2.64)

2.33***

(2.04-2.63)

2.91***

(2.34-3.84)

2.89***

(2.32-3.81)

Income 1.00

(.89-1.14) .99 (.87-1.12)

1.01 (.90-1.16)

1.01 (.88-1.15)

.91§ (.57-1.25)

.90§ (.53-1.17)

Ethnicity 1.06

(.92-1.24) 1.05 (.91-1.22)

--- --- --- ---

Live Alone 1.17§ (.99-1.39)

1.17§ (.99-1.39)

.95 (.75-1.19)

.96 (.76-1.20)

1.58**

(1.28)

1.54**

(1.25-21.5)

Widowed 1.39***

(1.23-1.58)

1.36***

(1.20-1.55)

1.48***

(1.28-1.69)

1.45***

(1.25-1.65) 1.15 (.81-1.70)

1.14 (.80-1.68) Current smoker 1.31***

(1.12-1.53)

1.30**

(1.11-1.52)

1.28**

(1.06-1.54)

1.29**

(1.07-1.54) 1.41*

(1.04-1.94) 1.37*

(1.01-1.88)

Past smoker 1.04

(.87-1.26) 1.06 (.88-1.28)

1.09 (.87)

1.12 (.89-1.39)

1.00 (.71-1.43)

.97 (.69-1.39) Presence of any

4 ADL

1.64***

(1.45-1.86)

1.64***

(1.45-1.86)

1.61***

(1.39-1.84)

1.63***

(1.41-1.86)

1.84***

(1.39-2.53)

1.71***

(1.30-2.34) Wald Chi-square 797.54 833.03 630.63 648.05 173.40 191.95

Degree of freedom 12 12 11 11 11 11

Note: Values are hazard ratios (95% Confidence Interval). W1= Wave 1. TDC=time-dependent co- variate.

§p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

treated as time-dependent: the presence of serious conditions is unrelated to mortality among Mainlander elders over the 11 years of follow-up. It seems that these life-threatening conditions are not so "threatening" among the Mainlander elders, when compared to conditions reported by their Taiwanese counterparts.

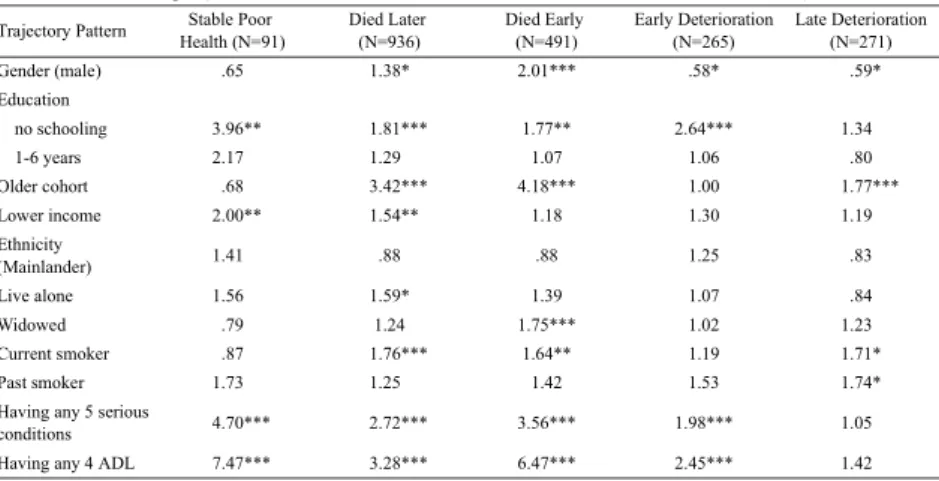

(2) Trajectory patterns

The results of multinomial logistic regressions predicting different health trajectories across the two ethnic groups of elders are presented in Table 4-1 to Table 4-3. For each predictor, odds ratios (OR) for comparing the trajectories of the "stable poor health," "died later," "died early," "early deterioration," and "late deterioration" categories against that of "stable good health" are reported for the whole sample (Table 4-1) and separately for the Taiwanese (Table 4-2) and Mainlanders (Table 4-3). Comparisons for the trajectory of "no clear pattern" are not the focus of this study and so are not shown here.

Starting from gender's effect on differentiating health trajectories, it is

Total Sample (Total N=3540, the "Stable Good" N=947, and the "No Clear Pattern" N=539) Trajectory Pattern Stable Poor

Health (N=91)

Died Later (N=936)

Died Early (N=491)

Early Deterioration (N=265)

Late Deterioration (N=271)

Gender (male) .65 1.38* 2.01*** .58* .59*

Education

no schooling 3.96** 1.81*** 1.77** 2.64*** 1.34

1-6 years 2.17 1.29 1.07 1.06 .80

Older cohort .68 3.42*** 4.18*** 1.00 1.77***

Lower income 2.00** 1.54** 1.18 1.30 1.19

Ethnicity

(Mainlander) 1.41 .88 .88 1.25 .83

Live alone 1.56 1.59* 1.39 1.07 .84

Widowed .79 1.24 1.75*** 1.02 1.23

Current smoker .87 1.76*** 1.64** 1.19 1.71*

Past smoker 1.73 1.25 1.42 1.53 1.74*

Having any 5 serious

conditions 4.70*** 2.72*** 3.56*** 1.98*** 1.05

Having any 4 ADL 7.47*** 3.28*** 6.47*** 2.45*** 1.42

Table 4-1. Odds Ratios from Multivariate Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Health Trajectory patterns:

§p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

clear that although male elders were 1.38 (p<.05) times more likely to die before 1993 and 2.01 (p<.001) times more likely to die after that year, they were less likely to experience an early (OR=.58, p<.05) or a late (OR=.59, p<.05) deterioration of self-rated health than their female counterparts.

However, when considering gender differences in trajectory patterns across ethnicity, a striking difference is found between Taiwanese and Mainlanders. That is, the gender mortality gap (male Taiwanese are more likely to die over the follow-up years) is not observed among the Mainlanders. However, it should be noted that the gender composition is extremely skewed among the Mainlanders. Only 16.8% of the Mainlander sample are female (see Table 1).

In terms of the health-protection effects of SES indicators, compared with those who have more than 7 years of schooling, elders with no formal schooling have significantly higher odds of staying in poorer health (OR=3.96, p<.01), dying before 1993 (OR=1.77, p<.001) or after that year (OR=1.81, p<.001) or experiencing an "early deterioration" (OR=2.64, p<.

001) of self-rated health. However, education's effects on health are less salient between elders who had less than 6 years of schooling and those who

Trajectory Pattern Stable Poor Health (75)

Died Later (N=754)

Died Early (N=397)

Early Deterioration (N=208)

Late Deterioration (N=215)

Gender (male) .65 1.54* 2.18*** .62§ .64§

Education

no schooling 3.68* 2.03*** 1.65* 2.29** 1.83*

1-6 years 1.66 1.29 .98 .95 .93

Older cohort .82 3.31*** 3.97*** .98 1.76**

Income (lower) 2.16** 1.50** 1.23 1.47* 1.26

Live alone 1.44 1.32 .75 .86 1.05

Widowed .77 1.41* 2.14*** 1.09 1.25

Current smoker 1.00 1.64** 1.47§ 1.04** 1.74*

Past smoker .97 1.19* 1.39 1.27 2.10*

Having any 5 serious

conditions 3.84*** 2.63*** 3.50*** 1.72** .97

Having any 4 ADL 5.50*** 3.01*** 5.78*** 2.22*** 1.23

Taiwanese Sample (Total N=2759, the "Stable Good" N=676, and the "No Clear Pattern" N=434) Table 4-2. Odds Ratios from Multivariate Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Health Trajectory patterns:

§p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

had 7 or more years of schooling. Lower-income elders are also more likely to stay in the "stable poor health" trajectory (OR=2.00, p<.01) or to die after 1993 (OR=1.54, p<.01). Regarding the differences in trajectory patterns across ethnicity, it seems that these SES indicators' health-protection effects are more salient in differentiating health trajectories among Taiwanese elders than they are among Mainlander elders. For example, income is not a significant predictor of health trajectories among the Mainlanders. For Mainlanders, education only matters in predicting the trajectory of "early deterioration."

There is some evidence that social relationships are associated with mortality over the follow-up years; but they operate in different ways across ethnicity. Widowhood is associated with mortality only among Taiwanese elders. On the other hand, Mainlander elders would be more likely to die over the period if they lived alone in 1989.

Smoking has been one of the leading causes of preventable death in Taiwan (Wen, Tsai, and Yen 1994); and from this study it seems that it is never too late to quit smoking. Those who were smoking in 1989 (the current smokers) were more likely to die over the follow-up years. Past

Trajectory Pattern Stable Poor Health

(N=16) Died Later (N=182) Died Early (N=94) Early Deterioration (N=57)

Late Deterioration (N=56)

Gender (male) .64 1.04 1.77 .52 .41*

Education

no schooling 3.02 1.21 2.07 3.71* .52

1-6 years 3.43 1.45 1.02 1.02 .91

Older cohort .18 3.78*** 5.30*** 1.17 1.65

Income (lower) 1.36 1.91 .77 .17 .27

Live alone 1.40 1.96* 2.68** 1.18 .61

Widowed .64 .65 .78 .85 1.25

Current smoker .44 1.88* 1.98§ 1.56 1.47

Past smoker 2.78 1.39 1.61 2.04§ 1.07

Having any 5 serious

conditions 13.78*** 2.81 3.33*** 2.82*** 1.27

Having any 4 ADL 27.70*** 5.68*** 14.29*** 4.97** 3.48*

Mainlander Sample (Total N=781, The "Stable Good" N=271, and The "No Clear Pattern" N=105) Table 4-3. Odds Ratios from Multivariate Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Health Trajectory patterns:

§p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

smoking behavior, however, was not associated with mortality over the follow-up years.

Finally, those who had any of the five serious conditions in the first wave are more likely to experience an "early deterioration" of self-rated health, to stay in the "stable poor health" trajectory, and to die, while those who had any of the four disabilities were also more likely enter the "early deterioration" trajectory, to stay in the "stable poor health" trajectory, and to die.

V. Discussion

For this studied cohort of elders, the ethnic division between Mainlander and Taiwanese elders is considered a salient dimension of social stratification, shaping the two groups of elders' pathways through life.

Emanating from this argument, this study empirically examines the health trajectories of these two ethnic groups of elders over 11 years of follow-up.

There are three major findings. (1) Self-rated health is shown to be a remarkably strong predictor of mortality despite controlling for other variables, which is consistent with the bulk of studies in this area. (2) By using a national representative sample of the elderly in Taiwan and treating self-rated health as a time-dependent covariate, evidence from this study reveals that self-rated health reflects a person's health trajectory. (3) Considerable differences exist in the ways socio-structural forces are related to the health trajectories of Mainlanders and Taiwanese, respectively, over the 11 years of follow-up. The social implications from these findings are discussed here.

First, although the association between self-rated health and mortality is quite similar between the Taiwanese and Mainlander sub-samples,

association patterns of many covariates do differ across ethnicity. For example, in terms of educational attainment, we know that educational opportunities were quite limited during the childhood and adolescence of this cohort of elders. This is especially true among the Taiwanese sub- sample. Almost 50% of them are illiterate. So, a plausible explanation of why low education is not predictive of mortality among the Mainlanders might be that a majority of them have at least some years of schooling, so there is little variation in the measure of education among Mainlanders to show its effect. On the other hand, it appears that the beneficial effect of income is more important for Mainlander elders, relative to the effect of education. Compared to Taiwanese elders, Mainlanders also have a higher average income. (A significant proportion of Mainlanders were on a variety of government pension programs.) At the same time, it could be that Mainlander elders have wider income gaps among them, when compared to their Taiwanese counterparts.

Turning to the two indicators of social relationships, living alone and being widowed, a very different association patterns across ethnicity is seen. As mentioned previously, in a society where the norm of filial piety is strongly emphasized, support for the elderly mainly takes the form of living with families (usually the older person's sons). Actually, even in the United States, where older people prefer to live independently when they can, a substantial number of the very old share homes with their children or other relatives (Golant 1996).

From the baseline survey, we know that for this cohort of elders marriage was a norm. This can be seen from the fact that marriage was almost universal among the Taiwanese sub-sample; but some 13% of the Mainlander elders never got married. Consequently, Mainlanders would have fewer children. Taiwanese would be more likely to live in an extended

family with their married children. Mainlanders might be less likely to receive a variety of support and assistance from their families. All of these point toward an intra-cohort differentiation of life course trajectories between these two groups of elders. Moreover, the types and sizes of their social ties would obviously differ significantly, which, in turn, influences their life chances during their later lives.

Another notable difference across ethnicity is that the measure of serious conditions is not predictive of mortality among the Mainlanders.

From the facts that Mainlanders have better access to health care and a significantly higher proportion of Mainlander elders have regular health check-ups, it is suspected that Mainlanders would likely be more aware of their chronic conditions, while conditions among the Taiwanese would go undiagnosed until they become more severe or even terminal.

Finally, even though there are significant mortality differentials between the two ethnic groups of elders, this ethnic disparity disappears when other socio-structural variables are taken into account. That is, ethnicity in this elderly population implies a social position that cut across other elements in the system of social stratification, such as SES, gender, and class; it also shares a lot of variance within these social structural variables. This is different from the racial/ethnic disparities of health observed in the United States, where social class accounts for part of the differences, but the health disparities between African Americans and whites remain after adjusting for measures of social class. As commented by Alwin and Wray (2005), the race/ethnic differences in health between African Americans and whites probably result from "patterns of institutional racial and ethnic discrimination that produce differential social pathways contributing to different health outcomes." On the contrary, the Mainlander and Taiwanese elders have lived on the island for more than half

a century. The boundaries and meaning of ethnicity are both undergoing renegotiation. From the facts that interethnic marriages are commonly seen and that a high percentage of Mainlanders and Taiwanese report close interethnic social ties, it is fair to say that, to some extent, there is permeability along the ethnic boundary and the social cleavages between the two ethnic groups have been narrowed over the years (Wu 2002). So, in the case of Taiwan, does this mean that ethnicity is a less important dimension of stratification than social class? However, as argued by Tung and Mutran, "meaningful ethnic identities are the way people conceive of themselves in their every day life." If social gerontology is committed to decreasing social inequality in health, more attention should be paid to identifing important social mediators of the aging experience.

References

Allison, P. D. 1995. Survival Analysis Using SAS: A Practical Guide. North Carolina: SAS Institute Inc.

Alwin, D. F. and L. A. Wray. 2005. "A Life-Span Development Perspective on Social Status and Health." Journal of Gerontology Social Sciences, 60B (Special Issue II): 7-14.

Bath, P. 2003. "Differences between Older Men and Women in the Self-Rat- ed Health-Mortality Relationship." Gerontolgoist 43: 387-395.

Benyamini, Y., T. Blumstein, A. Lusky, and B. Modan. 2003. "Gender Dif- ferences in the Self-Rated Health-Mortality Association: Is It Poor Self- Rated Health that Predicts Mortality or Excellent Self-Rated Health that Predicts Survival?" Gerontolgoist 43: 396-405.

Chen, W. C. 2005. "Ethnicity, Gender, and Class: Ethnic Differences in Ta- iwan's Educational Attainment Revisited." Taiwanese Sociology 10:

1-40.

Dannefer, D. 2003. "Cumulative Advantage/Disadvantage and the Life Course: Cross-Fertilizing Age and Social Science Theory." Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 58B: S327-S337.

Dannefer, D. and P. Uhlenberg. 1999. "Paths of the Life Course: A Typo- logy." Pp. 306-326 in Handbook of Theories of Aging, edited by V. L. Be- ngtson and K. W. Schaie. New York: Springer.

Deeg, D. J. H. and D. M. W. Kriegsman. 2003. "Concepts of Self-Rated Health: Specifying the Gender Differences in Mortality Risk." Geronto- logist 43: 376-386.

Elder, G. H., Jr. 1991. "Lives and Social Change." Pp. 58-86 in Theoretical Advances in Life Course Research: Vol. 1, Status Passage and the Life

Course, edited by W. R. Heinz. Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

Elder, G. H., Jr. 1994. "Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspec- tives on the Life Course." Social Psychology Quarterly 57: 4-15.

Ferraro, K. F. 2006. "Health and Aging." Pp. 238-256 in Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences, Sixth Edition, edited by R. H. Binstock and L. K.

George. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Ferraro, K. F. and J. A. Kelly-Moore. 2001. "Self-Rated Health and Mortal- ity among Black and White Adults: Examining the Dynamic Evaluation Thesis." Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 56B: S195-S205.

Ferraro, K. F. and J. A. Kelly-Moore. 2003. "A Half Century of Longitudi- nal Methods in Social Gerontology: Evidence of Change in the Journal."

Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 58B: S264-S270

Frankenberg, E. and N. R. Jones. 2004. "Self-Rated Health and Mortality:

Does the Relationship Extend to a Low-Income Setting?" Journal of Health and Social Behavior 45(4): 441-452.

Gates, H. 1987. Chinese Working-Class Lives: Getting By in Taiwan. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

George, L. K. 1993. "Sociological Perspectives on Life Transitions." An- nual Review of Sociology 19: 353-373.

George, L. K. 2003. "What Life-Course Perspectives Offer the Study of Ag- ing and Health. " Pp.161-188 in Invitation to the Life Course: Toward New Understandings of Later Life, edited by R. A. Settersten, Jr. Amity- ville, NY: Baywood Publishing.

Golant, S. 1996. "Problems in Conventional Dwellings and Neighbor- hoods." Pp. 207-235 in Aging for the Twenty-First Century: Readings in Social Gerontology, edited by J. Quadagno and D. Street. New York: St.

Martin's Press.

Hayward, M. D., E. M. Crimmins, T. P. Miles, and Y. Yu. 2000. "The Sig-

nificance of Socioeconomic Status in Explaining the Racial Gap in Chro- nic Health Conditions." American Sociological Review 65: 910-930.

House, J. S., D. Umberson, and K. Landis. 1988. "Structure and Process of Social Support." Annual Review of Sociology 14: 293-318.

House, J. S., J. M. Lepkowski, A. M. Kinney, R. P. Mero, R. C. Kessler, and A. R. Herzog. 1994. "The Social Stratification of Aging and Health."

Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35: 213-234.

House, J. S., P. M. Lantz, and P. Herd. 2005. "Continuity and Change in the Social Stratification of Aging and Health over the Life Course: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Longitudinal Study from 1986 to 2001/2002." Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 60B: S15-S26.

Hu, T. L. 1990. "Taros and Sweet Potatoes: Ethnic Relations and Identities of Glorious Citizens (Veteran-Mainlanders) in Taiwan." Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica 60: 107-132.

Idler, E. L. 1999. "Self-Assessments of Health: The Next Stage of Studies."

Research on Aging 21: 387-391.

Idler, E. L. 2003. "Discussion: Gender Differences in Self-Rated Health, in Mortality, and in the Relationship between the Two." Gerontolgoist 43:

372-375.

Idler, E. L. and Y. Benyamini. 1997. "Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty Seven Community Studies." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38: 21-37.

Kaplan, G.A., W. J. Strawbridge, T. Camacho, and R. D. Cohen. 1993. "Fac- tors Associated with Change in Physical Functioning in the Elderly: A Six Year Prospective Study." Journal of Aging Health 5: 140-153.

Liang, J., B. A. Shaw, N. Krause, J. Bennett, E. Kobayashi, T. Fukaya, and Y. Sugihara. 2005. "How Does Self-Rated Health Change with Age? A Study of Older Adults in Japan." Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences

60B: S224-232.

Liao, Y. L., D. L. McGee, J. S. Kaufman, G. C. Cao, and R. S. Cooper. 1999.

"Socioeconomic Status and Morbidity in the Last Years of Life." Ameri- can Journal of Public Health 89: 569-572.

Mirowsky, J., C. E. Ross, and J. Reynolds. 2000. "Links between Social Status and Health Status." Pp. 47-67 in Handbook of Medical Sociology, edited by C. Bird, P. Conrad, and A. Fremont. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Mor, V., V. Wilcox, W. Rakowski, and J. Hiris. 1994. "Functional Transi- tions among the Elderly: Patterns, Predictors, and Related Hospital Use."

American Journal of Public Health 84: 1274-1280.

Ross, C. E. and C. L. Wu. 1995. "The Links between Education and Health."

American Sociological Review 60: 719-745.

Ryder, N. 1965. "The Cohort as a Concept in the Study of Social Change."

American Sociological Review 30: 843-861.

Strawbridge, W. J. and M. I. Wallhagen. 1999. "Self-Rated Health and Mor- tality over Three Decades: Results from a Time-Dependent Covariate Analysis." Research on Aging 21: 402-416.

Stuck, A. E., J. M. Walthert, T. Nikolaus, C. J. Bula, C. Hohmann, and J. C.

Beck. 1999. "Risk Factor for Functional Status Decline in Community- Living Elderly People: A Systematic Literature Review." Social Science and Medicine 48: 445-469.

Taiwan Provincial Institute of Family Planning. 1989. 1989 Survey of Hea- lth and Living Status of the Elderly in Taiwan: Questionnaire and Survey Design. Comparative Study of the Elderly in Four Asian Countries, Re- search Report No. 1.

Tsai, S. L. 1996. "The Relative Importance of Ethnicity and Education in Taiwan's Changing Marriage Market." Proceedings of the National Sci- ence Council, Part C: Humanities and Social Sciences 6: 301-315.

Tung, H. J. and E. J. Mutran. 2005. "Ethnicity and Health Disparity among the Elderly in Taiwan." Research on Aging 27: 327-354.

Verbrugge, L. M. and A. M. Jette. 1994. "The Disablement Process." Social Science and Medicine 38: 1-14.

Walker, A. 1990. "The Economic Burden of Aging and the Prospect of In- tergenerational Conflict." Ageing and Society 10: 377-396.

Wang, F. C. 1993. "Causes and Patterns of Ethnic Intermarriage among the Hokkien, Hakka, and Mainlanders in Postwar Taiwan: A Preliminary Examination." Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica 76:

43-96.

Wen, C. Pan, S. P. Tsai, and D. D. Yen. 1994. "The Health Impact of Ciga- rette Smoking in Taiwan." Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 7(4):

206-213.

Wolinsky, F. D. and W. M. Tierney. 1998. "Self-Rated Health and Adverse Health Outcomes: An Explanation and Refinement of the Trajectory Hy- pothesis." Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 53B: S336-S340.

Wu, N. T. 1997. "Betel Nut and Sandal, Suit and Shoes: The Differences and Causes of the Social Mobility between Two Ethnic Groups." Taiwanese Sociological Review 1: 137-167.

Wu, N. T. 2002. "The Identity Conflict and Political Trust: Core Dilemmas of Current Ethnic Politics in Taiwan." Taiwanese Sociology 4: 75-118.

Wu, S. C. and T. L. Chiang. 1995. "Long-Term Care in Taiwan: Issues and Directions" Journal of Nationa Public Health Association (ROC) 14:

155-246.

Yu, E. S. H., Y. M. Kean, D. J. Slymen, W. T. Liu, M. Zhang, and R. Katz- man. 1998. "Self-Perceived Health and 5-Year Mortality Risks among the Elderly in Shanghai, China." American Journal of Epidemiology 147:

880-890.

Zimmer, Z., J. Natividad, H. S. Lin, and C. Napaporn. 2000. "A Cross-Na- tional Examination of the Determinants of Self-Assessed Health." Jour- nal of Health and Social Behavior 41: 465-481.

台灣老年人口的自評健康軌跡:

族群間的比較

董和銳

*中文摘要

在台灣的老年人口當中,本省籍與外省籍之間的族群差異是台灣 社會階層化的重要面向之一。本研究從生命歷程的觀點出發,利用國 民健康局的「台灣老人生活與保健調查」1989 到 1999 年的貫時性調 查資料(N=3540),實證地檢視自評健康的變化軌跡與存活狀況之間 的關係。主要的發現有: 與大部份老年學的相關文獻一致,自評健

康 與 存活 狀 況 之 間存 在 有 很強 的 相 關; 在 以時 間 相 依(Time-

dependent)的自評健康測量進行存活分析時發現,自評健康的變化確 實反映受訪老人的健康軌跡; 研究結果也發現社會結構變項與不同 的健康軌跡型態之間有不同的關聯。就族群間的健康差異而言,本研 究結果指出,不同於美國社會黑白之間的族群差異,台灣老年人口中 的族群差異似乎可以完全被社經地位變項所解釋(外省籍老人的平均 社經地位測量優於本省籍老人)。

關鍵字:台灣、自評健康、存活分析、族群、健康軌跡、老人

* 亞洲大學醫務管理學系助理教授