西方語法理論與中國語言事實的初始遭遇

——衛匡國《中國文法》序

姚小平

一

在西方與中國的交往史上,晚明是一個特殊的時期。西洋人首度大舉來華,接觸並認 識中國語言文化,就發生在那個時候。在那一時期的中西交流活動中,耶穌會士所起的作

用非常突出。比起 13 世紀初成立的方濟各會、道明會(一譯聖方濟會、多明我會)等修會,

後起的耶穌會只是小兄弟,建立於 1534 年,但很快就開始拓展傳教事業,向遠東地區進發。

1552 年 8 月,該會創始人之一沙勿略(St. Francis Xavier,1506-1552)從日本航行至上川 島,這裏距廣東臺山沙咀不足十海裏。由於明朝海禁甚嚴,他未能如願登陸。三年後,巴萊 多神父( Melchior Nuñez Barreto ,1520-1571:This Jesuit was the first missionary to whom Chinese barriers were temporarily lowered. He went as far as Canton, where he spent a month each time (1555). A Dominican, Father Gaspar da Cruz, was also admitted to Canton for a month, but he also had to refrain from forming a Christian community)曾在赴日途中泊靠廣州,謀劃 開拓中國教區,打算留下一位年輕會友,讓他專門學習漢語,然而也未能成功。又過二十 餘年,羅明堅(Michele Ruggieri,1543-1607)、利瑪竇(Matteo Ricci,1552-1610)終於從 澳門進入內陸,成為第一批通過實地接觸而學得中國語言文字的耶穌會士。

衛匡國(Martino Martini,字濟泰,1614-1661)於 1643 年入華,他與本會前輩利瑪竇

相隔逾半個世紀,據《在華耶穌會士列傳及書目》

1,這期間又有六十餘位耶穌會士陸續來到

中國,其中在研習中國語言文字上貢獻較多的,除了利瑪竇、衛匡國之外至少還有兩人:

郭居靜(Lazare Cattaneo,1560-1640:In Beijing the Jesuits resided at the residence of Wang Honghui, but Korean war fears hindered their visit. Wang, who had sponsored the trip, was passed over in his bid for a higher office, and thus had no direct influence with the eunuchs who maintained the Emperor’s appointment schedule. Money was running out, and it became clear a meeting at Court was now impossible. The two months spent at Wang’s residence were not idle, however. Ricci, Catteneo, and Zhong Mingren edited a Chinese vocabulary arranged in alphabetical order, romanized in the modified system originated by Ricci, including aspirants and indicators for the five tones of the Nanjing official language, which Ricci calls Quonhua (i.e., guanhua 官 話 ). Apparently a manuscript (now lost) was produced, entitled Vocabularium

sinicum, odine alphabetico europaeorum more concinnatum et per accentus suos digestum. Riccilater related how important Cattaneo’s contribution to the project was, “Father Catteneo contributed greatly to this work. He was an excellent musician, with a discriminating ear for delicate variations of sound and he readily discerned the variety of tones.” Nicolas Trigault refers to this work in his Chinese treatise Xiru ermu zi 西儒耳目資 (1626).)和金尼閣( Nicholas Trigault,1577-1628)。郭居靜與一位中國教友鐘巴相(Sébastien Fernandez,1562-1622,

一名鐘鳴仁)曾協助利瑪竇標注字音、辨別聲調,合作編纂了一部拉漢字典,即白佐良先

生(Giuliano Bertuccioli,1923-2001)在本書《導言》開首提到的那部成稿於 1598 年的字典

寫本,現藏於羅馬耶穌會檔案館;金尼閣這個名字在中國語言學家聽來並不陌生,因為

1626 年梓刻於杭州的《西儒耳目資》

2,署名作者便是金尼閣,這本書開耶穌會音韻研究之 先,不但系統地使用拉丁字母為漢字注音,還從普通語音學和比較語音學的角度解析漢語

的音理,為三百年後中國拼音字母的創制鋪墊了基礎。

3衛匡國做的卻是一件很不同的事情,他編寫了耶穌會的第一部漢語語法書。在衛匡國 之前,利瑪竇等人已注意到漢語具有奇特的構造,與西方人以往所知的任何其他語言類型 都不一樣。在金尼閣傳述的《利瑪竇中國劄記》裏,我們可以發現不少關於漢語特點的看法,

論及音節構造、聲調特徵、同音現象、文白異體、方言差別,有時還涉及語法,例如指出:在 兩個人談話時,漢語從不使用“語法上的第二人稱”;在談到自己時,從來不用“第一人 稱的代名詞”,“直呼本名而不說‘我’”,除非是主人對僕人、上級對下級說話;表示

客氣、謙恭、避諱的詞極多,等等。

4不過,這些說法都是從語用和修辭的視角,觀察漢語辭

彙語法而得出的零星結果,距離成體系的專門語法描寫尚遠。當衛匡國來到中國時,耶穌 會已經有了自成一體的拼音轉寫方案,也有了初具規模的漢外字典,這些都可以用於漢語 教學。但是,還缺少一本漢語語法書,這個任務就落到了衛匡國的肩上。

二

衛匡國抵達中國時,正值明王朝岌岌將墜。不久清兵入關,攻陷江南,他目見戰事的 慘烈,數度遭遇亂世之險。好在清軍無意加害西教,衛匡國與其他教士大都得以安然存身 且能不失時機地佈道宣教,為耶穌會吸納了一批本土士人。他沿承利瑪竇的做法,遵從中 國人祈祖祭孔的俗例,這也使得耶穌會在入華天主教各派當中發展最為順暢,與明清朝野

的關係都較好。在 1650 年爆發的所謂“禮儀之爭”中,衛匡國是代表耶穌會執言的關鍵人

物。那一年,羅馬教廷命令在華教士返回歐洲面陳原委,衛匡國被推為耶穌會特使,而待

到他歷盡艱辛抵達羅馬,已是 1654 年。同年,他向教廷呈遞了一份報告書——《中國基督

徒 人 數 與 素 質 簡 況 》 (

Brevis relatione de numero et qualitate Christianorum apud Sinæ,1654)。兩年後,教皇亞歷山大七世頒發飭令,准允中國教徒保留本民族的祭祀習俗。這樣的讓步在當時的教會只不過是一種策略罷了,然而在今天看來,卻是中西文化欲順利 交往而必須達成的折衷。或許衛匡國已經體悟到,任何一種西方精神文化形式,無論宗教、

哲學還是語法理論,來到中國都不能不接受改造,以靈活變通的方式存在。

返歐途中,衛匡國攜有多部書稿,並且在 1653-1658 年間先後出版了其中的三部:《中 國新地圖志》(Novus Atlas Sinensis),基於實地勘測,收載中國地圖 17 幅;《韃靼戰紀》

(De bello Tartarico),記敍明清戰史,也包括著者本人走北闖南的親身經歷;《中國上古 史》(Sinicæ Historiæ, Decas I),從神話傳說講起,敍述西曆紀元前的中國歷史。這些著作 無一不是創新,內容所及都是西方學界認識中國事物的盲區,只須一部就足以使他成名,

何況接連三部!歐洲知識界由是大為震撼,很多學人因此對中國歷史文化萌生興趣。此外 他還有一部書稿,在旅程中不斷修訂繕寫,那就是《中國文法》(Grammatica Sinica)。這 部稿子應該也有機會發表,可是始終未能梓行。其中的緣由已難考明,也許是因為他覺得 自己的作品尚未成型,需要時日提煉;但也可能是受限於技術條件,比如手稿中插有漢字 會讓印刷商發怵。

衛氏中文語法的原始手稿很可能已經佚失。幸運的是,衛匡國沿途與學界友人交往,

他們當中至少有兩位獲得了《中國文法》抄本這一珍奇難得的贈禮,而這兩份抄本又被輾轉

2《西儒耳目資》,中國文字改革出版社,1956 年影印版。

3 可參看羅常培,《耶穌會士在音韻學上的貢獻》,載《國立中央研究院中國歷史研究所集刊》一本,1930 年;

譚慧穎,《〈西儒耳目資〉辨源析流》,北京外國語大學博士論文,2007 年。

4《利瑪竇中國劄記》28-31、65、143-144 等頁,何高濟、王遵仲、李申譯,中華書局,1983 年。有關的評析可 參考 Gustav Ineichen, “Historisches zum Begriff des Monosyllabismus im Chinesischen”. Historiographia

傳抄,加上衛匡國留下的遺著(應是底稿或自抄新本,最有可能為身邊教友收藏),迄今 已發現的中文語法稿本計有五種,分藏於德國、英國、波蘭的幾家圖書館。白佐良比較了五 種抄本,決定選用柏林國家圖書館收藏的一種作為翻譯的底本,因為它最為完整、保存狀 態最好,而且來源可以確知:封面上寫有兩段題注,一段稱,這一本子是德國醫生克利耶

(Andreas Cleyer,1634-1697)於 1689 年從爪哇寄至歐洲的,作為禮物贈給本國同行門澤 爾(Christian Mentzel,1622-1701);另一段稱,巴耶(Theophilus Siegfried Bayer,1694- 1738)於 1716 年在柏林皇家圖書館抄錄了衛匡國的原本。門策爾起初迷戀於中國醫藥和植 物,後來將很大一部分精力投諸漢語研究,著有《中文之解:論漢字和漢語發音》 (Clavis

Sinica, ad chinensium scripturam et pronunciatorum mandarinicam,1698);巴耶是聖彼德堡科學院院士,因著《中文大觀:中國語言文字詮釋》(

Museum Sinicum: In quo Sinicae Linguae et Litteraturae ratio explicatur,1730)一書而被譽為西方漢學研究的先驅,此書收集了六萬漢字並摸索編排歸類的方法,是在歐洲正式刊行的第一部論述漢語的專著。然而 無論門澤爾或巴耶,其實都從未到過中國,他們對漢語語法結構的認識都受惠於衛匡國的

《中國文法》。

衛匡國的《中國文法》雖未湮沒,卻始終沒有公開發表。遲至 20 世紀末,《中國文法》才

得以公諸學界,有了現代印本,即白佐良譯注的拉丁文-義大利文對照本

5。不久,白佐良又

在《華裔學志》上用英文發表書評

6,考證衛氏語法撰寫、傳抄、流布的經過。 2006 年春天我在

羅馬訪學期間,已讀到拉意對照本,並隨手記下一些心得

7,現在寫這篇小序,恰能用上當

時所做的筆記。那時馬西尼教授告知,其師白佐良先生承譯的中文本已校訂過半,並邀我 為中譯本寫序。能有幸先期讀到漢譯文,且有機會與學界同好分享研讀所得,我自然樂意 之至。五年前,我們曾經把來華方濟各會士萬濟國( Francisco Varo, 1627-1687)撰著的

《華語官話語法》譯成中文

8,如今,一部比它更早的西洋漢語語法又將付梓;而在這之前,

英人威妥瑪(Thomas Francis Wade,1818-1895)編寫的《語言自邇集》也已有了中譯本

9。進 入新世紀以來,看到一部又一部西洋漢語研究史上的要著被還原為它們所探究的物件語言 身為中國學者我每每感到一種物還原主、學歸本根的欣喜。我們對整個海外漢語研究史的考 察,必將隨著這類要著的重刊、移譯、詮解和考釋,而逐漸地深入、豐滿起來。

三

《中國文法》僅含三章,首章談語音,後兩章論語法。書中舉例不多,表達精練,描述 簡約。全稿像是一份大綱,根據拉丁語法為漢語擬出語法框架,點到了很多大的方面,而 具細入微的探索還有待展開。

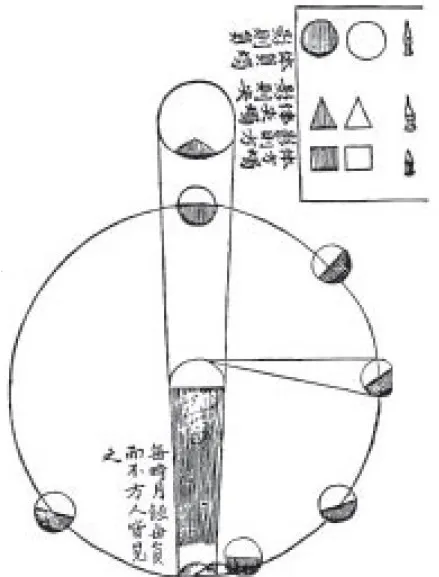

首章論述語音,主體是一張字表,列出三百多個字,實際上是一張音節表。衛匡國解 釋說,這些字都是單音節的詞,沒有屈折變化(monosyllabae et indeclinabiles)。這是從語 法和音節構造上看漢字,不管它的筆形構造;也即把漢字看作漢語裏最簡單而獨立的語言 單位,一個漢字就是一個單音節詞。傳教士接觸漢語之初,就為漢語的詞歸納出兩個特點 一是單音節性,二是沒有詞形變化。沒有詞形變化,這一點基本上可以肯定,然而單音節

性卻很有爭議。利瑪竇早就持類似的看法,甚至認定漢語裏面所有的詞都是單音節的

10;換

言之,即使是雙音節、多音節的詞,也都可以還原、歸簡為有意義的單個音節。可是我們觀

5 La Grammatica Sinica. In M. Martini, Opera Omnia, Vol.II, pp.349-481, a cura di Giuliano Bertuccioli.

Universita degli Studi di Trento, 1998.

6 Bertuccioli, Giuliano. “Martino Martini’s Grammatica Sinica”. In Monumento Serica(《華裔學志》), 51 (2003): 629-640.

7 載於拙著《羅馬讀書記》,外語教學與研究出版社將出。

8 瓦羅《華語官話語法》,姚小平、馬又清譯,外語教學與研究出版社,2003 年。

察上古漢語,如《詩經》當中,已經存在“蟋蟀、菡萏、崔嵬、逍遙、綢繆、婆娑”等不可拆解 的雙音節詞。顯然,漢語的字與詞、詞與音節並不像早期傳教士以為的那樣是完全等同的。

不過,比之印歐屈折語言和日語等粘著語言,漢語基本詞彙的單音節程度高得多,所以,

把單音節性看作漢語構詞的一個特點,大體上仍是可以接受的。關於單音節性這一命題,

因觀察分析的角度不同,學者們的看法也會各異,但有一點可以肯定:衛匡國在此列出的 音節表為漢語所獨有,任何一部西方語言的語法書都不會附帶這樣的音節表,更不用說把 它安排在起首第一章。

原作的字表上,每個字都標有拉丁注音,用拉丁語釋義,按照慣常的字母順序排列。

中譯本不僅用括弧加標了現代漢語拼音,還附上了另一種注音,即葡萄牙道明會士法蘭西 斯科·迪亞茲(Francisco Diaz,1606-1646)曾經用過的一套音標。白佐良認為,衛匡國在注 音時有可能借鑒了迪亞茲於 1640 年編成的《漢西字彙》(全名為 Vocabulario de Letra China

con la Explicacion Castellana “用卡斯蒂利亞語釋義的中文字典”)。這部字典收有七千餘字,較完整的抄本之一現藏波蘭克拉科夫市的雅傑隆斯卡圖書館。梵蒂岡圖書館存有另一抄本 編號 Borgia Cinese 412,我曾想借出一閱,可惜因本子遭損、有待修繕而未能如願。迪亞茲、

衛匡國所用的音標,都是早期漢字拉丁注音的珍貴史料;在《中國文法》的拉意對照本上,

除了這些之外還標有威妥瑪注音,例如第一個字“雜”,注音依次為衛匡國式、威妥瑪式、

現代拼音、迪亞茲式:

ça (tsa, zá) çǎ

字表一開頭說,漢語的音節不超過 318 個,可是序號卻明明排到第 320。或許應該剔除 第 102 個有音無字的 hun,以及第 293 字“物”(與第 299 字重複),那麼總數就恰如衛匡 國所說的那些。現代的漢語詞典在正文前後也常附有音節表,不過那上面的音節一般是帶 四聲的,而衛匡國的本意是要編一張無聲調的純音節表;這樣的純音節只是在理論上才有 其存在,需要用實有聲調的字來做例子。據他說,這些純音節配上五個聲調,足以構成 1179 個 音 節 。 接 下 來 , 他 從 學 習 者 的 角 度 講 了 六 個 較 難 發 的 音 , 都 是 輔 音 : c、ch、g、j、n、m(等於韻尾-ng),並與西班牙語、義大利語裏的類似輔音做了比較。拿義大 利語來比較,這很自然,因為衛匡國的母語是義大利語。至於還頻頻地與西班牙語做比較 一方面大概是想顧及西班牙傳教士學漢語的需要,另一方面則是受到迪亞茲等前人影響的 結果。

衛匡國辨別的五個聲調依次為:去聲、上聲、入聲、平聲、濁平;調號分別作:

ˊ,ˋ,ˇ,ˉ,ˆ。這樣的排序有些特別。萬濟國的五個聲調與此相同

11,排序更合中國人的習慣:

平清(上平)、濁平(下平)、上聲、去聲、入聲;調號分別為:ˉ,ˆ,ˋ,ˊ,ˇ。就分別調類 而言,西士並無發明,中國音韻學家早已判別清楚了,但創制調號是西士的貢獻。然而這 方面的首功應該記在利瑪竇、金尼閣的名下。

四

《中國文法》的第二章探討語法,分作三小節。第小一節的題目是〈論名詞及其變格〉,

當然漢語沒有屈折形變,所以衛匡國講的重點是:同一個字因其所在的位置不同,可以是 名詞或形容詞,也可以作動詞。名詞和動詞的界限不清楚,但不是所有的動詞都可以作名 詞,反之亦然。例如,“打”、“去”只是動詞,不能當名詞,而“愛”、“想”兼具動、名 二性,如在“我愛你”、“我想他”裏面是動詞,在“我的愛”、“我的想”中則是名詞。

至於形容詞,衛匡國認為它總是出現在名詞之前,如“好人”;後置於名詞的形容詞

就變為名詞:“人的好”(可是他沒有考慮“[他]人好”這種似乎更常見的構造)。這也等

於說,當一個名詞出現在另一個名詞之前,就成為形容詞。但如果一個名詞的後面帶了“

子”,如“房子”、“哥子”,則不能再充當形容詞。名詞沒有數的變化,複數意義用“們

”來表示,如“人們”;或可以利用字的重疊來表示,如“人人”。他特別提醒讀者,“

們”與西方語言的名詞複數標記並不相當,因為當一個名詞的前面已經有了表示數量的表 達時,就不能再用“們”,例如“多人”、“叫幾個人”,後面都不能帶“們”字。“子”

和“們”都是所謂“小詞”(particula)。更重要的一個小詞是“的”,表示屬格關係,永 遠後置於名詞或代詞:“人的好”、“我的狗”。在西洋漢語語法裏,小詞或小品詞(本書 中譯為“助詞”)從一開始就是一個至關重要卻又含混不清的概念,凡是表達語法意義的 字都叫小詞,涵蓋面幾乎跟虛詞一樣寬泛。

第二小節題作〈論代詞〉,只列口語的“我、你、他”及其帶“們”的複數形式,不涉及 文言人稱代詞。又列有“不變格”,即不帶“們”的“誰”,以及“個個”、“自己”、“

這個”、“那個”等。最後是指示代詞+量詞+名詞搭配的三個示例:“這個人”、“這只牛

”、“那匹馬”。關於量詞,後面第三章第七節講到數詞時有更詳細的列述。

第三小節〈論動詞變位〉,區分三個基本時態:“我愛”是現在時,“我愛了”是過去 時,“我將愛”是將來時。基本時態之外,又有已完成行為的表達,如“我愛過了”;或 一種延續未完的過去狀態的表達,如“那時間愛”。語式有三種:主動式,如“我愛”、“

我 打 你 ” ; 被 動 式 , 如 “ 我 被 他 的 愛 ” 或 “ 我 被 他 愛 ” 、 “ 我 被 他 打 ” ; 祈 願 式

(optativum,或稱“希求式”,本書中譯為“選擇式”),如“我巴不得愛”或“巴不得 我愛你”。這種語式見於希臘語而不見於拉丁語,所以衛匡國在把這兩句漢語譯入拉丁語 時,只能用虛擬式來表達:Utinam ego amem; utinam ego te amem;換用英語說,應該是

“If only I could love”、“If only I could love you”。無論在哪種語言裏,動詞都是最具活力、

最不易把握的詞類,況且中西語言動詞的形態絕然有別,比起其他詞類來在語義上也更難 對應,所以在早期的西洋漢語語法中,動詞便成為薄弱的一環。

第三章繼續講語法,含七節。第一節〈論介詞〉,把“前、後、上、下”看作介詞,與動詞 組合時一般出現在前,如“前作”、“後來”、“上去”、“下走”;與名詞組合時則出現 在後:“房前”、“門後”、“卓子上”、“地下”,但不儘然,如“外面”、“裏頭”。除 這些之外,只提到一個“為”,例子是“為天主到那裏”。

第二節〈論副詞〉,區分 21 類,可謂精細入微。第一類表示願望(optandi,本書中譯為

“選擇”),例詞是“巴不得”。這個例子在前一章裏講到動詞的時候也舉過,解釋為祈 願式,或許可以認為,在漢語裏是用副詞等辭彙手段來表達西方語言通過動詞變位元表示 的語氣。其餘各類的設立大抵是清楚而合理的。在西方語言中,副詞的詞形相當固定,從邏 輯語義上說與漢語的副詞也較容易逐類對應。

第三節〈論嘆詞〉,分出三類:表痛苦,表讚賞,表驚歎。按照今天常規的理解,第一 類“苦”、“苦惱”、“可憐”和第二類“奇”都是形容詞。無論歐語漢語,都有不少形容 詞可以單獨使用,作獨詞感歎句,例如“奇怪!”(英語 “Strange!”)。這類詞顯然有別 於嚴格意義上的感歎詞,如“啊(呀)!”、“哇(噻)!”。衛匡國在此引用的例詞,特 別是單音節的“苦”、“奇”,即使在文言裏通常也不獨用,要說成“苦耶!”、“奇哉!

”。這裏的“耶、哉”,也即本節陳述的第三類,是漢語特有的語尾助詞,早期的西洋漢語 語 法 沒 有 把 它 們 看 作 獨 立 的 詞 類 。 但 後 期 的 著 作 , 如 甲 柏 連 孜 ( Georg von der Gabelentz,1840-1893)在《漢文經緯》中,已明確設立一類“尾助詞”(Finalpartikeln),

儘管對於“哉”、“兮”等究竟屬於嘆詞還是尾助詞尚難決斷。

12第四節〈論不常用的連詞〉 。所謂“不常用”,指的是大都見於文言古語。其下略分四類:

1)起連系作用;2)起止句作用;3)表示轉折;4)表示相反。其中第 2 類“也”、“矣”

歸在連詞底下很勉強,不過著者已看出它們的功能在於“止句”,故稱之為“語尾小詞”

(particulae terminativae),這就為後來的語法家讓語尾詞獨立城類預備了有用的概念。

第五節〈名詞的原級、比較級和最高級〉 。按照西方語法,惟形容詞和副詞才有級的分別,

名詞並不適用這一範疇。衛匡國這樣解釋,是因為他把“果子”、“房子”等詞中的實字“

果”、“房”看作絕對名詞或純名詞,可比於形容詞的原級(或稱絕對級)。接下來講的“

更”“絕”等,現在作程度副詞解,衛匡國在前面的副詞一節裏也舉過具有比較意義的“

更”字。這一節的處理有些奇怪,形容詞本該單獨分出一節來講,可是本書中並沒有這樣 的一節。形容詞去了哪里呢?先是在第一章第一節,歸到名詞底下,把形容詞看作名詞的 活變形式,如“好”是名詞兼形容詞;之後是在第三章第二節,把形容詞視為副詞的小類 尤其是表示性質的“善、妙、好、巧”等;再次是在第三章第三節,看作嘆詞的一類,如“苦 奇”。看來著者是惑于漢語詞性之活,覺得把形容詞拆散開來,才符合漢語語法的實際。雖 然這樣做並不成功,卻也顯出一種企圖擺脫西方語法、把握漢語特點的嘗試。

第六節〈附:代詞〉,列出口語中的三個單數人稱代詞“我、你、他”,然後說明“的”

的用法,即表示領屬關係:“我的”、“我們的”、“我的國”、“我的府”。這一節的內容 與前面第二章第二節所敘不無重複,看來像標題所記的那樣,是一個附錄,想必是補寫之 後附上的,容以時日的話,著者會把兩處合併起來。

第七節〈論數詞以及與之有關的小詞〉,除開通常意義的數詞,還選出近四十個常用量 詞,歸作一類來分析。其體例大抵是,先說明一個量詞的適用範圍,指哪一類事物,再舉 出最常見的搭配形式。衛匡國最後指出,量詞也可後置於名詞,如“牛一頭”、“馬一匹”。

在初識漢語的歐人眼裏,量詞是一個突顯的特徵,無怪著者在這上面著墨很多。出自早期 傳教士之手的各類漢語字典,也常附帶一張量詞表,例如方濟各會士

葉宗賢(Basilii à Glemona,1648-1704)編纂的《字彙臘丁略解》(Dictionario Sinici-

Latina Brevis Explicatio )13, 附 錄 之 一 〈 數 目 異 節 〉 收 有 近 90 個 量 詞 ( Particulas Numerales)。其實,在表達本身難以數的事物、而又必須取某一單位來計量時,西方語言也 會用到量詞,例如在用拉丁文翻譯上述搭配短語時,衛匡國就用了

folium(張)、manus(卷)、

granum(粒)、par(雙)、massa(團)、congerie(堆)、bursa(袋)等詞。只是跟漢語的量詞比起來,這些詞終究個數有限,零零散散不成系統,所以西方語法學家對自己 的語言從不覺得有必要專門作量詞的分析,更不會當作一個自立的詞類來處理。

五

萬濟國的《華語官話語法》成書於 1682 年,1703 年出版於廣州,是迄今已知第一部正 式發表的西洋漢語語法。幾年前,在《華語官話語法》中譯本推出之際我曾寫道:我們追蹤

西方人研究漢語語法的歷史,“有案可查的始點”便是這本書。

14現在看來,這個始點還可

以往前推進數十年,到 17 世紀中葉衛匡國攜回歐洲的《中國文法》。據白佐良推測(見本書

〈導言〉第 5 節),《中國文法》應該在 1696 年就已經以某種形式在歐洲正式出版,只是還 沒有發現相應的印本,某個本子或有可能沉睡於東歐某國的某家圖書館。當然,我們要等 到那個印本重新面世,才有把握來改寫西方漢語語法的刊行史,否則“最早正式出版”這 項榮譽頭銜仍得頒給萬濟國語法。

西方人究竟是從什麼時候開始編撰漢語語法的呢?整個歷程的起點也許比衛匡國、萬

濟國都要早,早到 16 世紀末,因為根據道明會會史的記載,該會教士胡安 ·柯伯(Juan

Cobo , 生 年 未 詳 , 卒 於 1592 年 前 後 ) 撰 有 一 部 漢 語 語 法 , 書 名 叫 Arte de la lengua

13 梵蒂岡圖書館藏有這部字典的兩個抄本,分置於兩個庫,編號為 Borgia Cinese 495 和 Vat. Estr. Oriente 2。見拙文“早期的漢外字典——梵蒂岡館藏西士語文手稿十四種略述”,《當代語言學》2007 年第 2 期。

China(《中國語言文法》,或譯《中文語法術》);然後,1640-1641 年間在菲律賓,道明會

士法蘭西斯科·迪亞茲又編寫了一部漢語語法。

15可是,由於迄今尚未發見任何手稿或抄本,

迪亞茲的語法甚至連書名也已不存,這些就僅只是空頭記錄,難以作為“有案可查的始點

”。在此,像在任何一項人文學術史的考察中那樣,文本的發現和闡釋仍然至為關鍵。《華 語官話語法》、《中國文法》相繼譯成中文,進入中國學人的視野,意義正在這裏。如今,這 兩部初始階段的西洋漢語語法擺在我們面前,期待著感興趣者來對它們的體系、內容、概念 術語等等進行比較。同時,它們牽及的早期歷史在我們眼裏依然撲朔朦朧,有不少疑點尚 待澄清,例如:《華語官話語法》與《中國文法》有沒有淵源關係?萬濟國對衛匡國撰寫漢語 語法一事是否知情?《中國文法》在多大程度上是衛匡國的獨創,他是否借鑒過早先已有的 成果(如柯伯、迪亞茲的漢語語法,須知衛匡國對迪亞茲的《漢西字彙》並不陌生)?

諸如此類的問題,我們不妨先擱置起來。也許有一天,會突然在世界的某個角度發掘 出關聯文本,書稿、信件、日記等等,到那時種種疑團自會開釋。

(2007 年大雪日於北外)

The Paper Lion

Early Western Study of the Chinese Language

(www.logoi.com/notes/jesuits.html)

The European Catholic missionaries who reached China in the late 16th century were the first Westerners who tried to learn Chinese in a systematic way. The pioneers were two Italian Jesuit priests: Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci. They learnt Chinese with local tutors in the Portuguese colony of Macao, against the will of their brothers, who thought that they were wasting their time, trying to do the impossible. Indeed, without any grammar or dictionary, and with poor teachers who only spoke Southern dialects, it was a miracle that they learnt Chinese so well!

Michele Ruggieri was able, with some help, to write a catechism in Chinese, and he even composed poems in Chinese. Matteo Ricci surpassed him: he is the author and translator, together with a number of Chinese Christian literati, of numerous works on subjects such as geometry, geography, morality, theology and so on. He also compiled a Chinese-Portuguese dictionary, never published. Another Jesuit, Nicolas Trigault, wrote a massive work in Chinese entitled The

collection of sounds and writings of the Western scholars (1625), presenting to the Chinese publicthe Latin alphabet, while also offering the first system of "Romanization" (i.e. a way to render Chinese sounds in Latin letters).

How did these missionaries learn Chinese? Most of them thought that the Chinese language

did not have grammatical rules, and that the only way to learn it was to be exposed to a good

teacher, and to memorize sentences and patterns. In fact, this remained the way Westerners learnt

Chinese for a long time, at least until the beginning of the 20th century. Such method was based

on traditional Chinese pedagogy, which prized memorization of characters and of sentences

extracted from the classics of Chinese literature.

As a matter of fact, more experienced missionaries prepared simple conversation textbooks for the newly arrived recruits. Some 17th- and 18th-century teaching materials used by beginners have survived in the Vatican Library in Rome or in the French National Library in Paris: most of them consist of dialogues in spoken Chinese, usually between a Westerner and a curious Chinese.

The Chinese asks many questions about the customs and strange things of Europe, and the Westerner, beside trying to impress him with the description of mechanical clocks, oil painting in three dimensions and the like, always tries to talk about Christianity. The first Western grammar of Chinese was written in Latin by the Italian Jesuit Martino Martini in the mid-17th century, but was never published. In the latter part of the 17th century, however, missionaries from Spain (Dominicans, Augustinians and Franciscans) tried to fill the vacuum. Unlike the previous generation of Jesuit priests, these Spanish friars were bound to work not with the Chinese scholars, but among commoners. Thus they were interested in the spoken language, and not so much in the classical literature and the written classical language. They not only used dialogues, wrote dictionaries (of course by hand!), but finally were able to print a Spanish-language grammar of Chinese in Canton in 1703. Authored by Francisco Varo and Pedro de la Pifiuela (editor), the

Arte de la lengua mandarina (Art of the mandarin language) was circulated mainly amongmissionaries in China, and maybe passed on to some interested merchants. Only few copies made it to Europe, and were avidly collected by linguists, who used (and at times plagiarized!) that knowledge to establish the basis for the modern study of Chinese in the West.

We find a funny description of the best method to learn Chinese in a manuscript grammar prepared by the Augustinian monk José Villanueva towards the end of the 18th century:

What should a European do who wants to learn Chinese? He should put away the Chinese characters and start with the Chinese syllables written as European words and annotated with the proper accents.

He should not trouble to learn many syllables, but learn to pronounce those he reads with fluency and without hesitation. He must try to find some Chinese who speak and understand correct Mandarin, and should speak and converse with him as much as possible... Then after having trained for four or five months he should take a Chinese book, written in Chinese characters without admixture of European words... He should grasp the Chinese-European dictionary and look up each character patiently, one by one, and assure himself calmly of its meaning, without fear, realizing that he is carrying his cross. No doubt he will forget one character while he is looking for another. But he should not give up, only go on and look it up for the second, the fourth, and the sixth time. Often he will feel horrified and it will appear to him impossible to learn the characters. In each character he will see a fierceful lion wanting to attack him. When he realizes that it is a paper lion, he will laugh. After two months or at most three the fearful lion will be transformed in a peaceful ox ... .

Today such method would not find much acceptance, and nevertheless, many who study Chinese indeed still "feel horrified" and in each Chinese character continue to see a fierceful lion wanting to attack them!

Chinese as a foreign language

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Western study of the Chinese language)

This article contains Chinese text.

Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters.

Increased interest in China from those outside has led to a corresponding interest in the study of Chinese as a foreign language. However the teaching of Chinese both within and outside China is not a recent phenomenon. Westerners started learning Chinese language in the 16th century.

In 2005, 117,660 non-native speakers took the Chinese Proficiency Test, an increase of 26.52% from 2004.[1] From 2000 to 2004, the number of students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland taking Advanced Level exams in Chinese increased by 57%.[2] An independent school in the UK made Chinese one of their compulsory subjects for study in 2006.[3]

Contents [hide]

1 History 2 Difficulty

2.1 The characters 2.2 The tones 3 Where to learn

4 Notable non-native speakers of Chinese 5 See also

6 Notes 7 External links

[edit]

History

The fanciful Chinese scripts shown in Kircher's China Illustrata (1667). Kircher divides Chinese characters into 16 types, and argues that each type originates from a type of images taken from the natural world

The understanding of the Chinese language in the West began with some misunderstandings. Since the earliest appearance of Chinese characters in the West,[4] the belief that written Chinese was ideographic prevailed.[5]

Such a belief led to Athanasius Kircher's conjecture that Chinese characters were derived from the Egyptian hieroglyphs, China being a colony of Egypt.[6] John Webb, the British architect, went a step further. In a Biblical vein similar to Kircher's, he tried to demonstrate that Chinese was the Primitive or Adamic language. In his An Historical Essay Endeavoring a Probability That the Language of the Empire of China Is the Primitive Language (1669), he suggested that Chinese was the language spoken before the confusion of tongues.[7]

Inspired by these ideas, Leibniz and Bacon, among others, dreamt of inventing a characteristica universalis modelled on Chinese.[8]

Thus wrote Bacon:

“ it is the use of China and the kingdoms of the High Levant to write in Characters Real, which express neither letters nor words in gross, but Things or Notions...

[9]”

Leibniz placed high hopes on the Chinese characters:

“ j'ai pensé qu'on pourrait peut-être accommoder un jour ces caractères, si on en était bien informé, non pas seulement à représenter comme font ordinairement les caractères, mais même à cal-culer et à aider l'imagination et la méditation d'une manière qui frapperait d'étonnement l'ésprit de ces peuples et nous donnerait un nouveau moyen de les instruire et gagner.

[10]”

The serious study of the language in the West began with the missionaries coming to China during the late 16th century. Among them were the Italian Jesuits Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci. They mastered the language without the aid of any grammar books or dictionaries, and became the first sinologists. The former set up a school in Macao, the first school for teaching foreigners Chinese, translated part of the Great Learning into Latin, the first translation of a Confucius classic in any European language, and wrote a religious tract in Chinese, the first Chinese book written by a Westerner. The latter brought Western sciences to China, and became a prolific Chinese writer. With his amazing command of the language, Ricci impressed the Chinese literati and was accepted as one of them, much to the advantage of his missionary work. Several scientific works he authored or co-authored were collected in Siku Quanshu, the imperial collection of Chinese classics; some of his religious works were listed in the collection's bibliography, but not collected. Another Jesuit Nicolas Trigault produced the first system of Chinese Romanisation in a work of 1626.

Matteo Ricci, a Westerner who mastered the Chinese language

The earliest Chinese grammars were produced by the Spanish Dominican missionaries. The earliest surviving one is by Francisco Varo (1627–1687).

His Arte de la Lengua Mandarina was published in Canton in 1703.[11] This grammar was only sketchy, however. The first important Chinese grammar was Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare's Notitia linguae sinicae, completed in

texts followed, from Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat's Élémens (sic) de la grammaire chinoise in 1822 to Georg von der Gabelentz's Chinesische Grammatik in 1881. Glossaries for Chinese circulated among the missionaries from early on. Robert Morrison's A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, noted for its fine printing, is one of the first important Chinese dictionaries for the use of Westerners.

In 1814, a chair of Chinese and Manchu was founded at the Collège de France, and Abel-Rémusat became the first Professor of Chinese in Europe. In 1837, Nikita Bichurin opened the first European Chinese- language school in the Russian Empire. Since then sinology became an academic discipline in the West, with the secular sinologists outnumbering the missionary ones. Some of the big names in the history of linguistics took up the study of Chinese. Sir William Jones dabbled in it;[12]instigated by Abel-Rémusat, Wilhelm von Humboldt studied the language seriously, and discussed it in several letters with the French professor.[13]

The teaching of Chinese as a foreign language started in the People's Republic of China in 1950 at Tsinghua University, initally serving students from Eastern Europe. Starting with Bulgaria in 1952, China also dispatched Chinese teachers abroad, and by the early 1960s had sent teachers afar as Congo, Cambodia, Yemen and France. In 1962, with the approval of the State Council, the Higher Preparatory School for Foreign Students was set up, later renamed to the Beijing Language and Culture University. The programs were disrupted for several years during the Cultural Revolution.

According to the Chinese Ministry of Education, there are 330 institutions teaching Chinese as a foreign language, receiving about 40,000 foreign students. In addition, there are almost 5,000 Chinese language teachers.

Since 1992 the State Education Commission has managed a Chinese language proficiency exam program, which has tested over 142,000 persons. [12]

[edit]

Difficulty

Chinese is rated as one of the most difficult languages to learn, together with Arabic, Japanese and Korean, for people whose native language is English.[14] A quote attributed to William Milne

, Morrison's colleague, goes that learning Chinese is

“ a work for men with bodies of brass, lungs of steel, heads of oak, hands of springsteel, hearts of apostles, memories of angels, and lives of Methuselah.

[15]”

Two major difficulties stand out:

[edit]

The characters

The Kangxi dictionary contains 47,035 characters. However, most of the characters contained there are archaic and obscure. The Chart of Common Characters of Modern Chinese (现 代 汉 语 常 用 字 表 Xiandai Hanyu Changyong Zibiao), promulgated in People's Republic of China, lists 2,500 common characters and 1,000 less-than-common characters, while the Chart of Generally Utilized Characters of Modern Chinese (现代 汉 语 通 用 字 表 Xiandai Hanyu Tongyong Zibiao) lists 7,000 characters, including the 3,500 characters already listed above. Moreover, most Chinese characters belong to the class of semantic-phonetic compounds, which means that one can know the basic meaning and the approximate reading of most Chinese characters, after acquiring some elementary knowledge of the language.

Still, Chinese characters pose a problem for learners of Chinese. To the 17th-century protestant theologian Elias Grebniz, the Chinese characters were simply diabolic. He thought they were

“ durch Gottes Verhängniss von Teuffel eingeführet/ damit er die elende Leute in der Finsterniss der Abgötterei destomehr verstricket halte.

[16]”

In Gautier's novella Fortunio, a Chinese professor from the Collège de France, when asked by the protagonist to translate a love letter suspected to be written in Chinese, replies that the characters in the letter happen to all belong to that half of the 40,000 characters which he has yet to master.

[17]

[edit]

The tones

Mandarin has four tones. Other Chinese dialects have more, for example, Cantonese has nine (in six distinct tone contours

). In most Western languages, tones are only used to express emphasis or emotion, not to distinguish meanings as in Chinese. A French Jesuit, in a letter, relates how the Chinese tones cause a problem for understanding:

“ I will give you an example of their words. They told me chou signifies a book: so that I thought whenever the word chou was pronounced, a book was the subject.

Not at all! Chou, the next time I heard it, I found signified a tree. Now I was to recollect, chou was a book, or a tree. But this amounted to nothing; chou, I found, expressed also great heats; chou is to relate; chou is the Aurora; chou means to be accustomed; chou expresses the loss of a wager, &c. I should not finish, were I to attempt to give you all its significations.

[18]”

[edit]

Where to learn

Chinese courses have been blooming internationally since 2000 at every level of education.[19] Still, in most of the Western universities, the study of the Chinese language is only a part of Chinese Studies or sinology, instead of an independent discipline. The teaching of Chinese as a foreign language is known as duiwai Hanyu jiaoxue (对外汉语教学) in Chinese.

The Confucius Institute, supervised by Hanban (汉 办 ),[20] or the National Office For Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language, is responsible for promoting the Chinese language in the West and other parts of the world.

The People's Republic of China began to accept foreign students from the communist countries (in Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa) from the 1950s onwards. Foreign students were forced to leave the PRC during the Cultural Revolution.[21] Today's popular choices for the Westerners who want to study Chinese abroad include the Center for Chinese Language and Cultural Studies in Taiwan and Beijing Language and Culture University in Beijing. The former was especially popular before the 1980s when China had yet to open to the other parts of the world.

Several Mandarin courses are available online through various commercial web sites specifically catering to native English speakers. Free and Paid- for courses are also offered via podcasts.

Edmonton in Alberta Canada, is the first city in North America to incorporate Chinese language and cultural education within the context of the Alberta curriculum in public school system from kindergarden to high school education. The English-Chinese bilingual program is accessible to all children of chinese or non-chinese descent.

[edit]

Notable non-native speakers of Chinese

←

Frederick W. Baller : British missionary, linguist, translator, educator and sinologist←

L. Nelson Bell : American Missionary father- in-law of Billy Graham←

John Birch : American missionary and namesake of the John Birch Society←

Arthur Calwell : Australian politician←

Cường Để : Vietnamese prince←

Wolfram Eberhard : German sociologist←

Herbert Hoover : American President←

Bernhard Karlgren : Swedish Sinologist←

Kenneth Scott Latourette : American academic historian←

Walter Henry Medhurst British missionary and translator←

Ho Chi Minh : Vietnamese revolutionary←

Michiko Nishiwaki : Japanese actress←

Timothy Richard : American Baptist missionary←

Kevin Rudd : Australian Prime Minister←

Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky : Russian-born Bishop of Shanghai←

Richard Sorge : Soviet spy←

Hudson Taylor : British missionary and founder of the China Inland Mission←

Elsie Tu : British-born Hong Kong politician←

Samuel Wells Williams : American missionary, linguist, and diplomat←

Ruth Weiss : Austrian-born Chinese- naturalised journalist[edit]

See also

←

Edmonton Chinese Bilingual Education Association←

Japanese language education in Russia←

Japanese language education in the United States←

Language teaching[edit]

Notes

1. ^ (Chinese) "汉语水平考试中心:2005 年外 国考生总人数近 12 万",[1] Xinhua News Agency, January 16, 2006.

2. ^ "Get Ahead, Learn Mandarin", [2] Time Asia, vol. 167, no. 26, June 26, 2006.

3. ^ "How hard is it to learn Chinese?",[3] BBC, January 17, 2006.

4. ^ There are disputes over which is the earliest European book containing Chinese characters. One of the candidates is Juan González de Mendoza's Historia de las

cosas más notables, ritos y costumbres del gran reyno de la China published in 1586.

5. ^ Cf. John DeFrancis, "The Ideographic Myth".[4] For a sophisticated exposition of the problem, see J. Marshall Unger, Ideogram, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004.

6. ^ Cf. David E. Mungello, Curious Land:

Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Stuttgart: F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden, 1985, pp. 143-157; Haun

Saussy, Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2001, pp. 49-55.

7. ^ Cf. Christoph Harbsmeier, "John Webb and the Early History of the Study of the Classical Chinese Language in the West", in Ming Wilson & John Cayley (ed.s), Europe Studies China: Papers from an International Conference on the History of European Sinology, London: Han-Shan Tang Books, 1995, pp. 297-338.

8. ^ Cf. Umberto Eco, "From Marco Polo to Leibniz: Stories of Intercultural

Misunderstanding".[5] Eco devoted a whole monograph to this topic in his The Search for the Perfect Language, trans. James

Fentress, Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell, 1995.

9. ^ The Advancement of Learning, XVI, 2.

10.^ "Lettre au T.R.P. Verjus, Hanovre, fin de l'année 1698".[6] Cf. Franklin Perkins, Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light,

Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Machine translation: I thought we could perhaps one day accommodate these characters, if they were well informed, not only are usually represented as

characters, but even at calculate and assist the imagination and meditation in a way that would affect astonishment the spirit of these people and give us a new way to educate and win.

11.^ For more about the man and his grammar, see Matthew Y Chen, "Unsung Trailblazers of China-West Cultural Encounter".[7] Varo's grammar has been translated from Spanish into English, as Francisco Varo's Grammar of the Mandarin Language, 1703 (2000).

12.^ Cf. Fan Cunzhong (范存忠), "Sir William Jones's Chinese Studies", in Review of English Studies, Vol. 22, No. 88 (Oct., 1946), pp. 304–314, reprinted in Adrian Hsia (ed.), The Vision of China in the English Literature of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth

Centuries, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1998.

13.^ Cf. Jean Rousseau & Denis Thouard (éd.s), Lettres édifiantes et curieuses sur la langue chinoise, Villeneuve-d’Ascq: Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 1999.

14.^ According to a study by the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California in the 1970s, quoted on William Baxter's site.[8]

15.^ Quoted in "The Process of Translation:

The translation experience"[9] on Wycliffe's site.

16.^ Quoted in Harbsmeier, op. cit., p. 300.

17.^ "Sans doute les idées contenues dans cette lettre sont exprimées avec des signes que je n'ai pas encore appris et qui

appartiennent aux vingt derniers mille"

(Chapitre premier). Cf. Qian Zhongshu,

"China in the English Literature of the Eighteenth Century", in Quarterly Bulltein of Chinese Bibliography, II (1941): 7-48; 113- 152, reprinted in Adrian Hsia (ed.), op. cit., pp. 117-213.

18.^ Translated by Isaac D'Israeli, in his

Curiosities of Literature.[10] The original letter, in French, can be found in Lettres édifiantes et curieuses de Chine par des missionnaires jésuites (1702–1776), Paris: Garnier-

flammarion, 1979, pp. 468–470. chou is written shu in modern pinyin. The words he refers here are: 書, 樹, 暑, 述, 曙, 熟 and 輸,

all of which have the same vowel and consonant but different tones in Mandarin.

19.^ Cf. "With a Changing World Comes An Urgency to Learn Chinese",[11] Washington Post, August 26, 2006, about the teaching of Chinese in the US.

20.^ Abbreviated from Guojia Hanyu Guoji Tuiguang Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi (国家 汉语国际推广领导小组办公室).

21.^ Cf. Lü Bisong (呂必松), Duiwai Hanyu jiaoxue fazhan gaiyao (对外汉语敎学发展槪 要 "A sketch of the development of teaching Chinese as a foreign language"), Beijing:

Beijing yuyanxueyuan chubanshe, 1990.

[edit]