APRIL

2017

South China Sea Lawfare:

Post-Arbitration Policy Options and

Future Prospects

Edited by

Fu-Kuo Liu, Keyuan Zou, Shicun Wu, and Jonathan Spangler

South China Sea Think Tank

南海智庫

Taiwan Center for Security Studies

APRIL

2017

South China Sea Lawfare:

Post-Arbitration Policy Options and

Future Prospects

Edited by

Fu-Kuo Liu, Keyuan Zou, Shicun Wu, and Jonathan Spangler

South China Sea Think Tank

南海智庫

Taiwan Center for Security Studies

This report is the result of a collaborative effort by an international team

of authors. The content of the report does not necessarily reflect the

views of the individual authors, the editors, their respective institutions,

or the governments involved in the South China Sea maritime territorial

disputes.

Citation:

Fu-Kuo Liu, Keyuan Zou, Shicun Wu, and Jonathan Spangler (eds.), South China Sea

Lawfare: Post-Arbitration Policy Options and Future Prospects

, Taipei: South China Sea

Think Tank / Taiwan Center for Security Studies, April 20, 2017.

Citation for individual chapters:

Author Name, “Chapter Title,” in Fu-Kuo Liu, Keyuan Zou, Shicun Wu, and Jonathan

Spangler (eds.), South China Sea Lawfare: Post-Arbitration Policy Options and Future

Prospects

, Taipei: South China Sea Think Tank / Taiwan Center for Security Studies,

April 20, 2017.

© 2017

South China Sea Think Tank / Taiwan Center for Security Studies. All

rights reserved. For inquiries about distribution and licensing, please contact the

South China Sea Think Tank at research@scstt.org.

South China Sea Think Tank

Asia-Pacific Policy Research Association

Fl. 10, No. 221, Sec. 4, Zhongxiao East Rd.

Daan District, Taipei City

Taiwan (ROC) 10690

+886 927 727 325

research@scstt.org

Taiwan Center for Security Studies

No. 64, Wanshou Rd.

Wenshan District, Taipei City

Taiwan (ROC) 11666

+886 2 8237 7213

tcsstw.org@gmail.com

Cover photo:

ROC Coast Guard humanitarian rescue drill near Itu Aba (Taiping) Island on November 29, 2016 (ROC

Coast Guard)

NTD 300 / USD 10 / RMB 70 (print)

ISBN 978-986-92828-2-6 (print)

ISBN 978-986-92828-3-3 (ebook/pdf)

Contents

1

Executive Summary

5

Part I: Introduction

7

South China Sea Policy Options in the

Post-Arbitration Context

Jonathan Spangler

21 Part II: Rival Claimants

23

China’s Legal Policy Options and Future Prospects

Nong Hong

35

China’s Diplomatic Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Yan Yan

47

China’s Security Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Renping Zhang and Duo Zhang

61

Malaysia’s Policy Options and Future Prospects

Chow Bing Ngeow

77

Philippines’ Legal Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Jay L. Batongbacal

91

Philippines’ Diplomatic Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Richard Javad Heydarian

99

Philippines’ Security Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Rommel C. Banlaoi

111 Taiwan’s Legal Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Chen-Ju Chen

125 Taiwan’s Diplomatic Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Jonathan Spangler

143 Taiwan’s Security Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Fu-Kuo Liu

155 Vietnam’s Policy Options and Future Prospects

Truong-Minh Vu and Nguyen Thanh Trung

171 Part III: Major Stakeholders

173 ASEAN’s Policy Options and Future Prospects

Siew Mun Tang

187 Australia’s Policy Options and Future Prospects

Sam Bateman

205 United States’ Policy Options and Future Prospects

Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

221 Part IV: Conclusion

223 International Legal Perspectives on the South

China Sea Dispute after the Tribunal’s Award on

the Merits

Taiwan Center for Security Studies (TCSS) serves as a platform for research and

dialogue between international experts on issues of East Asian security and

cross-strait relations. It is affiliated with National Chengchi University in Taipei, Taiwan.

mcsstw.org

South China Sea Think Tank (SCSTT) is an independent, non-profit organization that

promotes dialogue, research, and education on South China Sea issues. It does not

take any institutional position on the disputes. SCSTT is part of the Asia-Pacific Policy

Research Association (APPRA).

Executive Summary

On July 12, 2016, the Tribunal in the South China Sea

arbi-tration case issued its Award, officially bringing closure

to the arbitral proceedings initiated by the Philippines

against China in early 2013. In the Award, the Tribunal’s

conclusions overwhelmingly supported the Philippines’

positions regarding almost all of the fifteen submissions

in its Memorial.

1The Tribunal also rejected or opted not

to take into account the vast majority of China’s

posi-tions as elaborated through official statements and was

similarly not persuaded by arguments issued or

evi-dence presented by Taiwan.

The Award, especially due to relevant countries’

pol-icy responses and the enduring controversy over its

content, has significant implications for the South China

Sea maritime territorial disputes, which remain one of

the most potent and complex issues affecting stability

and security in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. In

the post-arbitration context, rival claimants and major

stakeholders have been forced to recalibrate their

rhet-1 See “Table 1: Summary of the Philippines’ Submissions and Tribunal’sAwards” in the introduction to this report.

The Award has significant implications for the South China Sea maritime

territorial disputes, which remain one of the most potent and complex issues

oric, strategies, and policies in order to

safe-guard their interests and rights in the maritime

area while maintaining an image

international-ly that is conducive to achieving these aims.

This report, entitled South

China Sea Lawfare:

Post-Ar-bitration Policy Options and

Future Prospects, builds upon

the success of the first South

China Sea Lawfare report that

was published in early 2016.

2By bringing together an

in-ternational team of experts

writing on the different

ap-proaches of each claimant

and stakeholder, it aims to

serve as a more inclusive

reference on

post-arbitra-tion South China Sea policy

issues than the many other

analyses published in the

af-termath of the Award.

In Part I: Introduction, the report begins by

giving a brief overview of the arbitral

proceed-ings in historical perspective and summarizing

the legal positions of the parties involved and

the Tribunal’s conclusions as described in its

2 On January 29, 2016, the first South China Sea Lawfare reportwas published by the South China Sea Think Tank and the Taiwan Center for Security Studies. Fourteen authors from ten countries contributed to the publication, for which research began immediately following the release of the Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility on October 29, 2015, in the Philippines v. China arbitration case. The report can be downloaded from http://scstt.org/reports/2016/525/.

Bringing together an international

team of experts writing on the

different approaches of each

claimant and stakeholder, it aims to

serve as a more inclusive reference

on post-arbitration South China

Sea policy issues than the many

other analyses published in the

aftermath of the Award.

By encouraging and compiling a diversity

of views on the South China Sea, the

editors hope that this report will serve as

a resource for policymakers, a foundation

for future research, and an example of

constructive international collaboration in

the midst of the disputes.

two awards. In Part II: Rival Claimants and

Part III: Major Stakeholders, the chapters

focus on (1) the specific policy approaches

of each country or actor; (2) the implications

of the Award for each; (3) the legal,

diplo-matic, and security

pol-icy options available to

them; and (4) their future

prospects in the

post-ar-bitration context of the

South China Sea. In Part

IV: Conclusion, the report

explores the implications

of the Award for

interna-tional maritime law and

the future of maritime

territorial disputes. By

en-couraging and compiling

a diversity of views on the

South China Sea, the

edi-tors hope that this report

will serve over the coming

years as a resource for policymakers, a

foun-dation for future research, and an example

of constructive international collaboration

in the midst of the disputes.

Part I:

South China Sea Policy Options in the

Post-Arbitration Context

Jonathan Spangler

Introduction

Over the past year, many in-depth historical accounts and comprehensive analyses of the arbitral proceedings and actors’ responses to the arbitration case have been published. Among these, there is South China Sea Lawfare:

Le-gal Perspectives and International Responses to the Philippines v. China Arbitration Case, the predecessor to this report, also jointly published by the South China

Sea Think Tank and Taiwan Center for Security Studies. Released in January

Abstract

The arbitration case and the Tribunal’s conclusions as outlined in the Award have major

legal, diplomatic, and security implications for rival claimants and major stakeholders in

the South China Sea. As a result, states and other actors must consider their relevant policy

options and proceed accordingly. This chapter begins by providing a condensed historical

overview of the arbitral proceedings, which are summarized by dividing the timeline into

the pre-arbitration context, the Philippines’ initiation and China’s response, the Award on

Jurisdiction and Admissibility of October 2015, and the Award of July 2016 on the merits and

remaining issues in the arbitration case. It then considers the implications of the Award and

the related common policy options available to multiple claimants and stakeholders.

Legal-ly, these implications and policy options relate to the status of features, sovereignty issues,

maritime rights and entitlements, and obligations in maritime spaces. Diplomatically, they

involve recalibrating diplomatic relations and preferences regarding the means of dispute

settlement. In terms of security, they include legal justification for military operations,

em-boldened securitization efforts, and opportunities for confidence-building and cooperation.

In considering these issues, the chapter aims not to provide an exhaustive account of all

relevant implications and policy options but to serve as a foundation for the chapters that

follow as well as future research and policy discussions on the South China Sea maritime

territorial disputes.

2016, three months after the Award on Jurisdiction and Ad-missibility was issued by the Tribunal, that report included contributions from sixteen scholars who were collectively tasked with providing detailed analyses of the perspec-tives of ten rival claimants or major stakeholders in the South China Sea maritime territorial disputes.

In this report, we have encouraged our team of au-thors to minimize discussions of the background of the arbitral proceedings in order to focus specifically on the present and future of the South China Sea disputes in the post-arbitration context.

To serve as a basic foundation for readers, this chapter first provides a very brief timeline of the arbitral proceed-ings.1 It then offers a bird’s-eye view of the legal,

diplo-matic, and security implications of the Award and policy options for rival claimants and major stakeholders moving forward as discussed in much greater detail in the chap-ters that follow.

Philippines v. China in a Nutshell

Regardless of one’s views on the Philippines v. China ar-bitration case itself, there is a general consensus among government officials, researchers, and non-academic ob-servers that the arbitral proceedings have borne major im-pacts on the South China Sea maritime territorial disputes. Although the details of the proceedings, different actors’ legal perspectives, and relevant responses are complex and beyond the scope of this brief introduction, the issue can be roughly summarized by dividing the timeline into the pre-arbitration context, the Philippines’ initiation and China’s response, the Award on Jurisdiction and Admissi-bility of October 2015, and the Award of July 2016 on the merits and remaining issues in the arbitration case.

Pre-Arbitration Context

In the decades prior to the arbitration case, the South China Sea witnessed various rounds of bilateral and mul-tilateral negotiations regarding dispute settlement. All the while, the history of the maritime area has been punctu-1 For a more detailed historical overview, please refer to the

introduction of the previous report. See Jonathan Spangler and Olga Daksueva, “Philippines v. China Arbitration Case: Background, Legal Perspectives, and International Responses,” in Fu-Kuo Liu and Jonathan Spangler (eds.), South China Sea Lawfare: Legal Perspectives

and International Responses to the Philippines v. China Arbitration Case,

January 29, 2016, pp. 17–37.

China and the

Philippines have

exchanged views

on the maritime

disputes since the

1970s in various

diplomatic fora.

The history of the maritime area has

been punctuated by armed clashes,

occupations by force and without,

and heated political rhetoric

mostly involving reassertions of

sovereignty or accusations of illegal

actions by rival claimants.

ated by armed clashes, occupations by force and without, and heatedpolitical rhetoric mostly involving reassertions of sovereignty or accu-sations of illegal actions by rival claimants. China and the Philippines have exchanged views on the maritime disputes since the 1970s in var-ious diplomatic fora. Bilateral efforts resulted in multiple statements and agreements, including the Joint Statement between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of the Philippines concerning Con-sultations on the South China Sea and on Other Areas of Cooperation in 1995, the Joint Statement of the China-Philippines Experts Group Meeting on Confidence-Building

Mea-sures in 1999, the Joint Statement be-tween the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines on the Framework of Bilateral Cooperation in the Twenty-First Century in 2000, and a joint press statement following the third China-Philippines Experts’ Group Meeting on Confidence-Building Mea-sures in 2001.2 In 2002, the Declaration

on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) was signed between member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China. After that, negotiations within ASEAN on adopting a legally binding Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC) continued, eventually resulting in a draft agreement being accepted in 2012 and preliminary discussions with China but with no substantive agree-ment having yet been reached.

Initiation and Response

On January 22, 2013, the Philippines formally initiated arbitral pro-ceedings against China under Article 287 and Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). On February 19, 2013, China, via a Note Verbale, rejected and returned the Philippines’ Notification and Statement of Claim initiating the proceedings, stated that it would neither accept nor participate in the arbitration, and pro-vided reasoning to support its position.

2 Jonathan Spangler and Olga Daksueva, “Philippines v. China Arbitration Case: Background, Legal Perspectives, and International Responses,” in Fu-Kuo Liu and Jonathan Spangler (eds.), South China Sea Lawfare: Legal Perspectives and International

Philippines’ Submissions

The Philippines, in its Memorial presented to the Tribunal on March 30, 2014, requested that the Tribunal issue an Award regarding fifteen submissions related to the status and le-gal entitlements of certain features in the South China Sea, the conduct of states and other actors in the disputed areas, and the legal legitimacy of China’s historical claims. These are summarized in Table 1. In its testimony during the arbitral proceedings, the Philip-pines also requested that the Tribunal ad-dress other key issues beyond the scope of its fifteen Submissions, including the legal status of features in the Spratly Islands.

Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility

Following a hearing in July 2015 and several months of deliberations, the Tribunal issued its Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility on Oc-tober 29, 2015. In this preliminary award, the arbitrators concluded that they had jurisdiction regarding seven of the Philippines’ Submissions, reserved consideration on another seven, and requested clarification about one. (See Table 1.) China responded with a foreign ministry state-ment that declared that the Award “is null and void, and has no binding effect on China,” criti-cized the Philippine government for its “political provocation under the cloak of law,” and reiter-ated its previous position of non-acceptance and non-participation.

Award on Merits and Remaining Issues

From November 24–30, 2015, the Tribunal held the Hearing on the Merits and Remaining Issues of Jurisdiction and Admissibility, in which it heard the Philippines’ arguments related to the arbitra-tion case. On July 12, 2016, the Arbitral Tribunal issued its Award. The Philippines’ submissions and additional claims, the Tribunal’s conclusions contained in its Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, and its conclusions made in the Award are summarized in Table 1 below.

China responded

with a foreign

ministry statement

that declared that

the Award “is null

and void, and has

no binding effect on

China,” criticized the

Philippine government

for its “political

provocation under

the cloak of law,” and

reiterated its previous

position of

acceptance and

non-participation.

Implications and Policy Options

The profound implications for states and actors involved in the South China Sea disputes come not only from the content of the Award itself but also from the responses and actions of others in the post-arbitration context. For analytical pur-poses, the implications and relevant policy

op-tions are roughly categorized in this chapter and throughout the report as relating to legal, diplo-matic, and security issues. Needless to say, these issues are tightly intertwined, and there is much overlap and interaction between these loose categorizations. Nevertheless, they are useful in achieving the aim of more clearly illustrating the key issues that are at stake. Many implications and policy options are shared in part by differ-ent states, regional groupings, and other actors. At the same time, due to the unique contexts in which each of them operates, there are also oth-er implications and policy options specific to coth-er- cer-tain claimants or stakeholders, but these will be addressed in full in subsequent chapters.

Legal Implications

The Tribunal’s interpretations of international maritime law, particularly those affecting the le-gal status of features, sovereignty issues, mari-time rights and entitlements, and obligations in maritime spaces have effectively redrawn the legal landscape of the South China Sea. In turn,

the legal implications resulting from the conclu-sions outlined in the Award demand that rival claimants and major stakeholders consider their relevant policy options and proceed accordingly.

Status of Features

The Tribunal’s conclusions about the legal status

of features have major implications for maritime delimitation in the South China Sea. For both those whose legal positions have been backed up by the arbitrators and those whose national interests have been negatively impacted, key de-cisions must be made as a result. In particular, countries have been forced to express support for the Award, reject it and provide sufficient justi-fication for doing so, or find a safe middle ground based on partial acceptance and/or ambiguity. Although it is yet to be seen, the reality is that even those that have explicitly expressed support for the Award would likely no longer agree with it in its entirety if the Tribunal’s conclusions were used in the future in a way that was detrimen-tal to those countries’ own national interests.

In other words, even explicit and apparently full support today may only translate to partial sup-port in the future. History shows that countries are often unlikely to participate in compulsory international arbitration mechanisms when the outcome would clearly prove detrimental to their interests.

Countries have been forced to express support for the Award, reject it and

provide sufficient justification for doing so, or find a safe middle ground

based on partial acceptance and/or ambiguity.

Philippines’ Submission or Additional Claim March 30, 2014; November 30, 2015 Tribunal’s Position in Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility October 29, 2015

Tribunal’s Position in Final Award

July 12, 2016

1 China’s maritime entitlements in the South China Sea, like those of the Philippines, may not extend beyond those permitted by [UNCLOS].

Reserved

consideration UNCLOS “defines the scope of maritime entitlements in the South China Sea, which may not extend beyond the limits imposed therein.” (X, 1203, B, 1)

2 China’s claims to sovereign rights and jurisdiction, and to “historic rights”, with respect to the maritime areas of the South China Sea encompassed by the so-called “nine-dash line” are contrary to the Convention and without lawful effect to the extent that they exceed the geographic and substantive limits of China’s maritime entitlements under UNCLOS.

Reserved

consideration China’s claims regarding “historic rights, or other sovereign rights or jurisdiction, [within] the ‘nine-dash line’ are contrary to [UNCLOS and have no] lawful effect [where] they exceed the geographic and substantive limits of China’s maritime entitlements under [UNCLOS]”.

UNCLOS “superseded any historic rights, or other sovereign rights or jurisdiction, in excess of the limits imposed therein.” (X, 1203, B, 2)

3 Scarborough Shoal generates no entitlement to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

Had jurisdiction Scarborough Shoal is a rock without EEZ or continental shelf entitlements. (X, 1203, B, 6) It is entitled to territorial waters.

4 Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal and Subi Reef are low-tide elevations that do not generate entitlement to a territorial sea, exclusive economic zone or continental shelf, and are not features that are capable of appropriation by occupation or otherwise.

Had jurisdiction Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are low-tide elevations without territorial sea, EEZ, or continental shelf entitlements. They are not “capable of appropriation.” (X, 1203, B, 4)

Subi Reef is a low-tide elevation without territorial sea, EEZ, or continental shelf entitlements. It is not “capable of appropriation, but may be used as the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea of high-tide features situated at a distance not exceeding the breadth of the territorial sea.” (X, 1203, B, 5) It is within the 12-nm territorial waters of Sandy Cay, which is a high-tide feature. (X, 1203, B, 3, d)

5 Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are part of the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of the Philippines.

Reserved

consideration Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are low-tide elevations without territorial sea, EEZ, or continental shelf entitlements, and “there are no overlapping [EEZ or continental shelf] entitlements … in the areas.” (X, 1203, B, 4)

6 Gaven Reef and McKennan Reef (including Hughes Reef) are low-tide elevations that do not generate entitlement to a territorial sea, exclusive economic zone or continental shelf, but their low-water line may be used to determine the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial sea of Namyit and Sin Cowe, respectively, is measured.

Had jurisdiction Gaven Reef (South) and Hughes Reef are low-tide elevations without territorial sea, EEZ, or continental shelf entitlements. They are not “capable of appropriation, but may be used as the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea of high-tide features situated at a distance not exceeding the breadth of the territorial sea.” (X, 1203, B, 5)

Gaven Reef (South) is within the 12-nm territorial waters of Gaven Reef (North) and Namyit Island, which are high-tide features. (X, 1203, B, 3, e)

Hughes Reef is within the 12-nm territorial waters of McKennan Reef and Sin Cowe Island, which are high-tide features. (X, 1203, B, 3, f)

7 Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef and Fiery Cross Reef generate no entitlement to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

Had jurisdiction Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef and Fiery Cross Reef are rocks without EEZ or continental shelf entitlements. (X, 1203, B, 6)

Philippines’ Submission or Additional Claim March 30, 2014; November 30, 2015 Tribunal’s Position in Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility October 29, 2015

Tribunal’s Position in Final Award

July 12, 2016

8 China has unlawfully interfered with the enjoyment and exercise of the sovereign rights of the Philippines with respect to the living and non-living resources of its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.

Reserved

consideration China “breached its obligations under Article 56” regarding “the Philippines’ sovereign rights over the living resources of its exclusive economic zone” by implementing its 2012 South China Sea fishing moratorium and not making “exception for areas of the South China Sea falling within the exclusive economic zone of the Philippines [or] limiting the moratorium to Chinese flagged vessels.” (X, 1203, B, 9)

9 China has unlawfully failed to prevent its nationals and vessels from exploiting the living resources in the exclusive economic zone of the Philippines.

Reserved

consideration China “breached its obligations under Article 58(3)” by not preventing “fishing by Chinese flagged vessels” at Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal, which are within the Philippines’ EEZ, in May 2013. (X, 1203, B, 11)

10 China has unlawfully prevented Philippine fishermen from pursuing their livelihoods by interfering with traditional fishing activities at Scarborough Shoal.

Had jurisdiction China has, since May 2012, “unlawfully prevented fishermen from the Philippines from engaging in traditional fishing at Scarborough Shoal,” which “has been a traditional fishing ground for fishermen of many nationalities.” (X, 1203, B, 11)

11 China has violated its obligations under the Convention to protect and preserve the marine environment at Scarborough Shoal and Second Thomas Shoal.

Had jurisdiction China “breached its obligations under Articles 192 and 194(5)” because it “was aware of, tolerated, protected, and failed to prevent” environmentally destructive activities by fishermen from Chinese flagged vessels, who “have engaged in the harvesting of endangered species on a significant scale[ and] the harvesting of giant clams in a manner that is severely destructive of the coral reef ecosystem” in the South China Sea. (X, 1203, B, 12)

12 China’s occupation and construction activities on Mischief Reef (a) violate the provisions of the Convention concerning artificial islands, installations and structures;

(b) violate China’s duties to protect and preserve the marine environment under the Convention; and

(c) constitute unlawful acts of attempted appropriation in violation of the Convention.

Reserved

consideration China “breached its obligations under Articles 123, 192, 194(1), 194(5), 197, and 206” because its land reclamation and construction have “caused severe, irreparable harm to the coral reef ecosystem” without cooperating, coordinating, or communicating environmental impact assessments with other countries. (X, 1203, B, 13)

China “breached Articles 60 and 80” through its “construction of artificial islands, installations, and structures at Mischief Reef without the authorisation of the Philippines” because the feature is a low-tide elevation not capable of appropriation within the Philippines’ EEZ. (X, 1203, B, 14)

13 China has breached its obligations under the Convention by operating its law enforcement vessels in a dangerous manner causing serious risk of collision to Philippine vessels navigating in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal.

Had jurisdiction China “breached its obligations under Article 94” and “violated Rules 2, 6, 7, 8, 15, and 16 of the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972” by causing “serious risk of collision and danger to Philippine ships and personnel” through the “operation of its law enforcement vessels” on April 28 and May 26, 2012. (X, 1203, B, 15)

Philippines’ Submission or Additional Claim March 30, 2014; November 30, 2015 Tribunal’s Position in Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility October 29, 2015

Tribunal’s Position in Final Award

July 12, 2016

14 Since the commencement of this arbitration in January 2013, China has unlawfully aggravated and extended the dispute by, among other things: (a) interfering with the Philippines’ rights of navigation in the waters at, and adjacent to, Second Thomas Shoal; (b) preventing the rotation and resupply of Philippine personnel stationed at Second Thomas Shoal; and (c) endangering the health and well-being of Philippine personnel stationed at Second Thomas Shoal.

Reserved

consideration China has aggravated the disputes over “the status of maritime features in the Spratly Islands” as well as those about the countries’ “respective rights and entitlements” and “the protection and preservation of the marine environment” at Mischief Reef. (X, 1203, B, 16)

China has enlarged the disputes over “the protection and preservation of the marine environment to Cuarteron Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Gaven Reef (North), Johnson Reef, Hughes Reef, and Subi Reef.” (X, 1203, B, 16)

15 Original:

China shall desist from further unlawful claims and activities.

Amended:

China shall respect the rights and freedoms of the Philippines under the Convention, shall comply with its duties under the Convention, including those relevant to the protection and preservation of the marine environment in the South China Sea, and shall exercise its rights and freedoms in the South China Sea with due regard to those of the Philippines under the Convention.

Requested

clarification China should have abstained from activities with “a prejudicial effect [on] the execution of the decisions to be given” and activities that “might aggravate or extend the dispute during” the arbitral proceedings. (X, 1203, B, 16)

Additional Issues

1 Itu Aba (Taiping) Island is a rock, not an island, under Article 121(1) and 121(3) of UNCLOS.

(Itu Aba Island is occupied by Taiwan and is the largest feature in the Spratly Islands.)

Itu Aba (Taiping) Island is a rock without EEZ or continental shelf entitlements because “no maritime feature claimed by China within 200 nautical miles of Mischief Reef or Second Thomas Shoal constitutes a fully entitled island.” (X, 1203, A, 2, a)

2 Thitu Island is a rock, not an island, under Article 121(1) and 121(3) of UNCLOS.

(Thitu Island is occupied by the Philippines and is the second-largest feature in the Spratly Islands.)

Thitu Island is a rock without EEZ or continental shelf entitlements because “no maritime feature claimed by China within 200 nautical miles of Mischief Reef or Second Thomas Shoal constitutes a fully entitled island.” (X, 1203, A, 2, a)

Philippines’ Submission or Additional Claim March 30, 2014; November 30, 2015 Tribunal’s Position in Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility October 29, 2015

Tribunal’s Position in Final Award

July 12, 2016

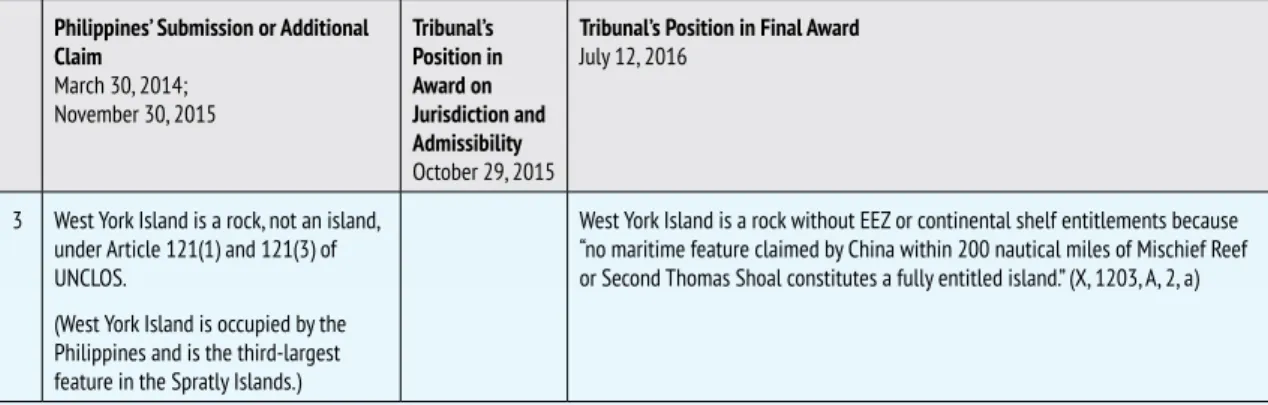

3 West York Island is a rock, not an island, under Article 121(1) and 121(3) of UNCLOS.

(West York Island is occupied by the Philippines and is the third-largest feature in the Spratly Islands.)

West York Island is a rock without EEZ or continental shelf entitlements because “no maritime feature claimed by China within 200 nautical miles of Mischief Reef or Second Thomas Shoal constitutes a fully entitled island.” (X, 1203, A, 2, a)

Sovereignty Issues

Although the Tribunal, China, and the Philippines all separately recognized in official statements that the Tribunal did not have jurisdiction over sovereignty issues, discussions of other issues in the Award made implicit legal conclusions about sovereignty. For example, the arbitrators (1) in-terpreted the legal status of features (i.e., the ‘rocks’ or ‘islands’ question) in the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal, (2) recognized the Philip-pines’ 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending from its coastlines, (3) concluded that China’s nine-dash line claims are not in

ac-cordance with international law to the extent that they represent claims to rights or entitlements in excess of those accorded by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and (4) determined that Philippine fishermen enjoy historical fishing rights in the vicinity of the Scarborough Shoal. Taken individually, each of these could be understood as not necessari-ly representing decisions on sovereignty issues. However, given the interconnected nature of the issues, their combined effect could undoubtedly have a profound impact on issues of sovereignty.

This is a conundrum that governments and inter-national legal scholars are still in the process of grappling with. For states and other actors, how to address the issue, if at all, will necessarily fac-tor into the formulation of their South China Sea policy approaches in the future.

Maritime Rights and Entitlements

As mentioned above, the Tribunal made conclu-sions related to the legal status of features under UNCLOS, the Philippines’ EEZ, and China’s nine-dash line. As a result, the Award has major im-plications for maritime rights and entitlements. Moreover, these implications are not necessarily limited to the South China Sea because decisions made in past international arbitration cases of-ten serve as precedents for those in future cases. As the sovereignty claims and entitlements of all rival claimants are affected either directly or indi-rectly by the Award (most notably, the conclusion that no features in the Spratly Islands or Scarbor-ough Shoal are EEZ-entitled), these countries will all need to factor the new reality into their South China Sea policy approaches, whether they rec-ognize the legal effect of the Award or not. More-over, non-claimant stakeholders such as Austra-lia, India, Japan, and the US must also consider their revised policy options for military, commer-cial, and other operations in the South China Sea.

Obligations in Maritime Spaces

Another key issue that the Tribunal considered in its Award was Chinese activities on maritime fea-tures and the actions of Chinese or China-flagged vessels in relevant maritime areas. The arbi-trators concluded that China had breached its obligations under UNCLOS by (1) engaging in artificial island creation and infrastructural devel-opment on features within the Philippines’ EEZ, (2) allowing environmentally destructive living resource extraction operations to take place, and (3) interfering in Filipinos’ lawful fishing activi-ties. Aside from the immediate reputational dam-age done to Beijing for supporting such activities now deemed to be illegal under international law, these conclusions may have important ripple

Aside from the immediate

reputational damage done to

Beijing for supporting such activities

now deemed to be illegal under

international law, these conclusions

may have important ripple effects

as other countries may think

twice about the potential legal

repercussions of their own activities

at sea.

effects as other countries may think twice about the potential legal repercussions of their own ac-tivities at sea.

Diplomatic Implications

In addition to legal issues, the Award and subse-quent responses in the post-arbitration context present important diplomatic implications and

relevant policy options. These relate to the reca-libration of diplomatic relations between coun-tries and other actors and preferences regarding means of dispute management.

Recalibrating Relations

Because of the legal impacts of the Award on the status of features, sovereignty issues, mari-time rights and entitlements, and obligations in maritime spaces, rival claimants and major stake-holders have had to recalibrate their bilateral and multilateral diplomatic relations to suit the post-arbitration context.

In terms of relevant policy options, a major aspect of efforts to recalibrate diplomatic re-lations has been for states and other actors to determine how vocal to be in their support for or opposition to the Award and whether or not – and, if so, how – to criticize and respond to the actions of other actors. On the whole, most have opted for diplomatic caution and ambiguity re-garding issues perceived as sensitive. At the time of writing, only seven countries had publicly ex-pressed support for the Award and called upon the parties to abide by the Tribunal’s conclusions as outlined within. Many others have demon-strated a high level of diplomatic caution by is-suing vague and ambiguously or indirectly word-ed statements. In many cases, these have been

interpreted by observers as weak or otherwise toned-down for fear of disrupting relations with Beijing. Therefore, these soft statements demon-strate not so much that those actors oppose the Tribunal’s conclusions but that China’s influential role in the global economic system and political order is a paramount consideration for them. The extent to which these cautious approaches aimed at maintaining the diplomatic status quo will continue to be so widespread remains to be

seen, and the issue will likely depend on the in-ternational community’s ongoing assessment of Chinese actions in the region.

Means of Dispute Management

Following the Award, many actors have been em-boldened in expressing their pre-existing prefer-ences regarding means of dispute management. There are a range of possible options for man-aging or settling territorial disputes, including through bilateral and multilateral diplomatic ne-gotiations and consultations, nene-gotiations within regional groupings, third-party mediation, and international arbitration. Each of the claimants and stakeholders in the South China Sea has their own preferences on the issue. The Philip-pines’ unexpected unilateral initiation of arbitral proceedings against China was the first of its kind in the South China Sea and a first for China. Once the arbitral proceedings had been initiated, they effectively pushed aside other available means of dispute management until the case had con-cluded. Now, in the post-arbitration context, ri-val claimants and major stakeholders can again more meaningfully advocate their preferences, and each must consider which dispute manage-ment policy options best serve their interests and those of the region.

Rival claimants and major stakeholders have had to recalibrate their bilateral

and multilateral diplomatic relations to suit the post-arbitration context.

Security Implications

Although the Award only directly addressed a small subset of security issues that exist in the South China Sea (i.e., regarding Chinese law enforcement ac-tivities), it does have several broader security implications. These relate to legal justifications for law enforcement and military operations, the emboldening of countries in their regional securitization efforts, and emerging opportunities for confidence-building and cooperation.

Legal Justifications for Law Enforcement and Military Operations

Because the Tribunal sought to determine in its Award the legal status of fea-tures in the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal (i.e., as “rocks” without EEZ entitlements under UNCLOS), confirmed the Philippines’ EEZ entitlements, and concluded that China’s nine-dash line claims are not in accordance with

inter-national law where they represent claims to rights or entitlements in excess of those accorded by UNCLOS, a new, albeit incomplete, clarity has emerged regard-ing maritime delimitation – at least from the perspec-tives of actors supportive of the arbitration case. For countries conducting military or law enforcement op-erations in the South China Sea, the content of the Award may offer legal justifications for such activities. Based on the Tribunal’s conclusions, for example, lit-toral states will be able to use the Award to justify law enforcement operations targeting illegal fishing ac-tivities within EEZs as drawn from the coastlines with-out having to consider the possibility of EEZ-entitled islands in the Spratly Islands affecting these maritime boundaries. Moreover, other countries, including non-claimants, will be able to more conveniently provide legal justification for freedom of navigation (FON) operations with less concern for any potential le-gal effect of China’s nine-dash line claim.

Emboldened Securitization Efforts

One further implication of the possible legal justifications for law enforcement and military operations noted above is that the Award may embolden countries in their securitization efforts. Increased law enforcement and naval presence in maritime areas compounded with an increased confidence in the legality of relevant activities could, in turn, lead to an increased risk of incidents at sea. Countries will have to carefully consider the geographic scope, objectives, and transparency of their activities when formulating relevant policy.

Opportunities for Confidence-Building and Cooperation

On the other hand, the “legal clarity with caveats” that the arbitration case has provided may present some opportunities for confidence-building and

cooper-For countries conducting

military or law enforcement

operations in the South

China Sea, the content of

the Award may offer legal

justifications for such

activities.

ation on security issues. Vast maritime expenses were addressed in the Award to different extents and with varying conclusions. In some of those maritime areas, rival claimants may find points of agreement, which could serve as foundations for negotiations that later develop into confidence-building mea-sures and security cooperation. In particular, there may be substantial diplo-matic space for cooperation on maritime law enforcement and non-traditional security issues such as piracy and drug trafficking.

Conclusion

As outlined above, the Award has major legal, diplomatic, and security im-plications for rival claimants and major stakeholders in the South China Sea. As a result, states and other actors must consider their relevant policy op-tions and proceed accordingly. Legally, these implicaop-tions and policy opop-tions relate to the status of features, sovereignty issues, maritime rights and en-titlements, and obligations in maritime spaces. Diplomatically, they involve recalibrating diplomatic relations and preferences regarding the means of dispute settlement. In terms of security, they include legal justification for

mil-itary operations, emboldened securitization efforts, and opportunities for con-fidence-building and cooperation. The issues considered include only those that are common to multiple claimants and stakeholders. To be sure, there are also many crucial country- or actor-specific implications and policy options to be addressed in the post-arbitration context of the South China Sea maritime territorial disputes. It is these issues and more that are discussed in greater detail in the chapters that follow.

Jonathan Spangler is the Director of the South China Sea Think Tank. His research focuses on Asia-Pacific

regional security, maritime territorial disputes, and cross-strait relations. His publications, projects, and contact information can be found at jspangler.org.

In some maritime areas, rival claimants may find points of agreement,

which could serve as foundations for negotiations that later develop into

Part II:

Post-Arbitration South China Sea:

China’s Legal Policy Options and Future

Prospects

Nong Hong

Abstract

With the Award being released on July 12, 2016, the South China Sea arbitration case, lasing

for more than three years, has come to an end. The Tribunal concluded in its thoroughly

one-sided Award that many of China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea were contrary

to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and that actions

support-ed by the Chinese government had thereby violatsupport-ed the Philippines’ sovereign rights and

freedoms. In general, China’s legal policy approach to territorial disputes is based on its

preference for negotiation and/or consultation directly with the other party, and its position

of non-participation in and non-acceptance of the South China Sea arbitration case and its

awards has been coherent. The end of the proceedings does not mean the end of the

dis-putes between the two countries and within the region. However, it does have important

legal and political implications for China and other states. First of all, it has had detrimental

impacts on China’s sovereignty claims and related entitlements. Second, the Arbitral

Tribu-nal expanded its jurisdiction and ignored the legitimate and reasonable claims of the coastal

states. Third, this unpleasant result helped the Chinese government justify its position of

non-participation and non-acceptance as this ruling has severely harmed China’s national

interests. Fourth, it raises doubts about the role of UNCLOS in maritime dispute settlement.

This has legal implications not just for China but for international law more broadly. Finally,

the Award does not lead to the settlement of the maritime disputes between the contracting

states of UNCLOS in the South China Sea. That said, the arbitration case has motivated China

and ASEAN to speed up negotiations on a Code of Conduct. It has also created an

oppor-tunity for both China and the Philippines, which have openly expressed their willingness to

engage in bilateral negotiations. These developments also raise important questions about

the role that extra-regional actors should play in the disputes. The South China Sea has a

complicated past and an uncertain future, but cooperation among nations could stabilize

the region and bring tranquility to this important sea.

Introduction

With the Award released on July 12, 2016, by the Arbitral Tribunal established under Annex VII of the United Na-tions Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the South China Sea arbitration case, lasing for more than three years, has come to an end. Unlike similar cases that resulted in more balanced conclusions regarding mari-time disputes between two claimants, the Award is con-sidered an overwhelming win for the Philippines.

China’s position of non-participation and non-accep-tance can be clearly explained by its legal culture and state practice regarding international dispute settle-ment. Its strong opposition to the arbitration case has been clearly analyzed in its Position Paper on December 7, 2014, which deeply questioned the jurisdiction of the Arbitral Tribunal and admissibility of the case.1 A careful review of the Award on merits and remaining issues of

jurisdiction and admissibility has verified China’s skep-ticism that the South China Sea arbitration case is not purely an attempt to resort to an international judiciary in order to resolve the maritime disputes. Instead, it is a political game of international law.

China is now facing tremendous pressure from some members of the international community, especially the United States and Japan, calling for a full implementation of the Award. China’s position of non-participation and non-acceptance has won overwhelming support from its people, particularly since the Award was issued on July 12, 2016. This unpleasant result helped the Chinese government justify its position of non-participation and non-acceptance as the Tribunal’s conclusions severely harm China’s national interests. For some Chinese in-ternational law scholars that believed that participation would have given China a better chance to present its legal argument and evidence, the Award eliminated their confidence and belief that international law, especially UNCLOS, could have a constructive and positive role in settling the maritime disputes in the South China Sea. Hence, China is unlikely to recognize or comply with the Award.

Facing a dilemma arising from the Award, China, the Philippines, and other claimant states must recalibrate 1 “Position Paper of the Government of the People’s Republic

of China on the Matter of Jurisdiction in the South China Sea Arbitration Initiated by the Republic of the Philippines,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, December 7, 2014, <http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1217147.shtml>.

China’s position of

non-participation

and non-acceptance

can be clearly

explained by its legal

culture and state

practice regarding

international dispute

settlement.

China has always advocated

bilateral negotiations as the

most practical means of dispute

settlement between states. In

practice, China has resolved

several of its bilateral disputes

with other countries through

negotiation and consultation.

their policy approaches and reconsider their available policy options.This paper analyses China’s approach to international law and third party compulsory dispute settlement mechanisms and its positions and legal bases for these positions in the South China Sea arbitration case. It then explores the legal implications arising from the Award and also the further implications for international law, including UNCLOS and Article 298 in particular. The paper suggests that between China and the Philippines, only direct negotiations based on mutual respect will be constructive and able to

rebuild lost confidence. The dis-cussions on exploring other re-gional and local remedies that have emerged among China and other claimant states and ASEAN and should continue. Moreover, fostering regional functional cooperation based on the principles of Article 123 of UNCLOS should be en-hanced, and other stakeholders in the South China Sea will have to play a more constructive role in contributing to the peace and stability of the region.

Legal Policy Approach

China’s legal policy approach to territorial disputes has involved em-phasizing its preference for bilateral negotiations and consultations, exclusion of compulsory arbitration for dispute settlement, and non-participation in the Philippines’ unilaterally initiated arbitration case and non-acceptance of the resulting awards.

Preference for Bilateral Negotiations

Ways of peaceful dispute settlement include good office2, mediation,

consultation, negotiation, arbitration, courts, and so on. In most cases, China prefers direct negotiation and/or consultation with the other par-ty. This orientation mostly originates from and owes itself to Chinese culture and history. China has always advocated bilateral negotiations as the most practical means of dispute settlement between states. In practice, China has resolved several of its bilateral disputes with other countries through negotiation and consultation, such as border and 2 Typically, these are low-key actions by a third party to bring opposing parties to

dialogue or negotiation. Good offices may include informal consultations to facilitate communication; offers of transportation, security, or venues; or fact-finding. The third party may suggest ways of negotiations and achieving a settlement but usually stops short of participating in negotiations.

dual nationality disputes, among other issues. As far as the judiciary is concerned, China’s atti-tude is very conservative. Thus far, no dispute be-tween China and any other state had ever been brought before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or other international tribunals, so the South China Sea arbitration case is an exception in this regard. During the Sino-India border conflict in 1962, China refused India’s proposal to submit the dispute to international arbitration by stating that the “Sino-India border dispute is an import-ant matter concerning the sovereignty of the two countries, and the vast size of more than 100,000

square kilometres of territories. It is self-evident that it can only be resolved through direct bilat-eral negotiations. It is never possible to seek a settlement from any form of international arbi-tration.”3 However, after the 1980s, it changed

its policy by consenting to arbitration in treaties that it ratified to, but confined this only to eco-nomic, trade, scientific, transport, environmental, and health areas.4 Some conventions require the

contracting states to accept compulsory judicial dispute settlement procedures. For instance, UN-CLOS makes it obligatory for its state parties to select at least one of the compulsory procedures: the ICJ, International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), arbitration, or special arbitration. Upon ratification of the convention, China did not state which mechanism it had accepted. There-fore, it was deemed to accept the mechanism of arbitration.5

3 Gao Yanping, “International Dispute Settlement,” in Wang Tieya (ed.), International Law, Beijing: Law Press, 1995, pp. 611–612. [Chinese]

4 Zou Keyuan, China-ASEAN Relations and International Law, Oxford: Chandos Publishing, 2009, p. 31.

5 UNCLOS, Article 297(3).

Exclusion of Compulsory Arbitration for Dispute

Settlement

Meanwhile, China’s perception of the role of in-ternational courts in dispute settlement is also passive. In treaties in which it is a party, China has usually made a reservation about the clause of judicial settlement by the ICJ. On September 5, 1972, China declared that it did not recognize the statement of the former Chinese government on Acceptance of the Compulsory Jurisdiction of the ICJ. In fact, it refused to settle any dispute with other countries through the ICJ. On the other hand, as a UN Security Council member, it has nominated judges of Chinese nationality to the ICJ as well as to other international courts, such as ITLOS. Since these courts are composed main-ly of judges from the West, developing countries, including China, are doubtful about the impar-tiality and justice the international judiciary can maintain.6 As for UNCLOS, China declared on

September 7, 2006, under Article 298 the exclu-sion of certain disputes (such as those concern-ing maritime delimitation in territorial disputes or military use of the ocean) with other countries from the jurisdiction of the international judiciary or arbitration.7 As one Chinese scholar points out,

there is slim chance that China would change its attitude towards third-party dispute settlement forums in the near future with regard to its dis-pute in the South China Sea.8

Nevertheless, some other international legal scholars in China started to bring to the table the issue of third-party compulsory dispute set-tlement forums. At the “Symposium on China’s Energy Security and the South China Sea” held in China in December 2004, for example, Jia Yu explained the reasons why China felt reluctant to go to an international court to address its dis-putes with other countries, especially regarding sovereignty claims and maritime jurisdiction. Un-like the assumptions of some western scholars, 6 Zou, China-ASEAN Relations and International Law, 2009, p.

32.

7 “China’s Declaration in Accordance with Article 298 of UNLOCS,” September 7, 2006.

8 Interview with Dr. Wu Shicun.

During the Sino-India border conflict

in 1962, China refused India’s

proposal to submit the dispute to

international arbitration

China’s hesitation does not come from a lack of evidence for its sovereignty claims in the cases of the East China Sea and South China Sea. In fact, as the former ITLOS Judge Chan Ho Park point-ed out, comparpoint-ed with Vietnam and other South China Sea countries, China has more historic ev-idence to show its jurisdiction in the South China Sea.9 Jia Yu argued that China’s reluctance to

ac-cept a third party settlement forum comes from, first of all, the lack of experience in international litigation, and secondly, the lack of expertise in the international law field with regard to dispute

settlement.10 Apart from the reasons given by Jia

Yu, the political culture of China and many Asian countries, which emphasizes a belief in good neighbourly relations, will be jeopardized if the differences have to be resolved by third-party involvement and is therefore a psychological ob-stacle to using third-party mechanisms.

Non-Participation and Non-Acceptance

China’s position on the South China Sea Arbitra-tion case, namely non-participaArbitra-tion and non-ac-ceptance, has been coherent. On January 23, 2013, the day after the Philippines filed its No-tification and Statement of Claim,11 the Chinese

Foreign Ministry spokesman stated that China has “indisputable sovereignty” over the South 9 Interview with Judge Chan Ho Park in Shanghai, 2005. 10 Jia Yu, Presentation at the “Energy Security and the South

China Sea” Conference, Haikou, 2004.

11 “Notification of Statement and Claim,” Notification, No. 13-0211, Department of Foreign Affairs, Republic of the Philippines, January 22, 2013, <http:// www.philippineembassy-usa.org/uploads/pdfs/ embassy/2013/2013-0122-Notification%20and%20 Statement%20of%20Claim%20on%20West%20 Philippine%20Sea.pdf>.

China Sea under “abundant historical and legal grounds.”12 He blamed the dispute on the

Phil-ippines’ “illegal occupation of some of the Chi-nese islets and atolls of the Spratly Islands” and claimed that China had been “consistently work-ing towards resolvwork-ing the disputes through dia-logue and negotiations to defend Sino-Philippine relations and regional peace and stability.”13

On February 19, 2013, China officially refused to participate in the proceedings.14 In addition,

China accused the Philippines of making factually flawed accusations and of violating the

Declara-tion on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC).15 Chinese Foreign Ministry

spokes-man Hong Lei mentioned the consensus that Chi-na and ASEAN member states reached when they signed the DOC in November 2002 that disputes should be solved through talks between the

na-12 “China reiterates islands claim after Philippine UN move”,

BBC, January 23, 2013, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/

world-asia-21163507>.

13 “China reiterates islands claim after Philippine UN move”,

BBC, January 23, 2013, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/

world-asia-21163507>.

14 “China rejects Philippines’ arbitral request”, China Daily, February 19, 2013, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/ china/2013-02/19/content_16238133.htm>.

15 Article 5 states that “[t]he Parties undertake to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.” See “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea,” Foreign Ministers of ASEAN and People’s Republic of China, November 4, 2002, <http://cil.nus.edu.sg/rp/ pdf/2002%20Declaration%20on%20the%20Conduct%20 of%20Parties%20in%20the%20South%20China%20Sea-pdf.pdf>.

The political culture of China and many Asian countries, which emphasizes

a belief in good neighbourly relations, will be jeopardized if the differences

tions directly involved.16

China considers the act of initiating arbitral proceedings unfriendly and damaging to Si-no-Philippine relations. China complained that “the Philippine side had failed to notify the Chi-nese side, not to mention seeking China’s con-sent, before it actually initiated the arbitration.”17

There are several reasons why China rejected the arbitral proceedings, including (1) China has been consistent in its position on resolving the disputes between Beijing and Manila through bi-lateral negotiations; (2) under international law, China has the right to turn down the request from the Philippines for arbitral proceedings to

take place because it has made a declaration un-der Article 298 of UNCLOS; and (3) the act of filing the arbitration case poses an obstacle for the two countries in developing friendly relations.

In addition, China also questioned whether the Arbitral Tribunal had jurisdiction over the case. Although the Philippines did specifical-16 Hong Lei, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hong

Lei’s Regular Press Conference on October 28, 2014,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, October 28, 2014, <http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/ xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1204813.shtml>; Hong Lei, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hong Lei’s Regular Press Conference on November 23, 2015,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, November 23, 2015, <http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/ s2510_665401/t1317589.shtml>.

17 Sun Xiangyang, “Press Conference By Chinese Embassy On Philippines’ Submission of a Memorial to the Arbitral Tribunal on disputes of the South China Sea with China,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of the Philippines, April 1, 2014, <http:// ph.china-embassy.org/eng/xwfb/t1143166.htm>.

ly discuss the territorial issue in its Notification and Statement of Claim, it is impossible to dis-cuss most of its claims without first clarifying Chinese and Philippine sovereignty over island features in the South China Sea. For example, the majority of the Philippines’ claims assume that China only has territorial sovereignty over a few “rocks,” such as Chigua Jiao (Johnson Reef), Huayang Jiao (Cuarteron Reef) and Yongshu Jiao (Fiery Cross Reef) in the Nansha (Spratly) Is-lands,18 while intentionally ignoring the fact that

China has claimed sovereignty over the entire Nansha (Spratly) Islands. Hence, China maintains that the Philippines’ claims are essentially

mar-itime delimitation claims that involve questions of territorial sovereignty. Such questions, however, are excluded from UNCLOS arbitration under Article 298. Thus, China believes that its rejection of the arbitration has a solid basis in inter-national law.

Legal Implications of the Award

The Award can be understood in terms of the direct legal implications for China and the further implications for interna-tional law, especially the role of UNCLOS in settling or managing maritime disputes. For China, these legal implications include detrimtal impacts on sovereignty claims and related en-titlements in the South China Sea, illegalization of certain Chinese activities, improved grounds for justifying its non-participation in and non-ac-ceptance of the arbitral proceedings, increased doubts about the use of international law for dis-pute settlement, and reinforcement of the view that other stakeholders’ legal perspectives and actions do not contribute to regional peace and stability.

First, the Award suggests that China’s histo-ry-based claims within the nine-dash line do not 18 “Notification of Statement and Claim,” Notification,

No. 13-0211, Department of Foreign Affairs, Republic of the Philippines, January 22, 2013, pp. 12–13, <http:// www.philippineembassy-usa.org/uploads/pdfs/ embassy/2013/2013-0122-Notification%20and%20 Statement%20of%20Claim%20on%20West%20 Philippine%20Sea.pdf>.