Analyses

This chapter discusses the results of the two research projects, script methodology application and CIT in two separate sections. The first section presents discrepancies and congruencies between the general script of the conference organizers and that of the interpreters. The second section begins with the comparison and contrast of satisfactory incidents between the clients and the interpreters, proceeds with identified similarities and differences in the dissatisfactory incidents of the clients and the interpreters, and ends with a judgment of whether client satisfaction and dissatisfaction with interpretation services derive from the underlying events and behaviors that are opposites or mirror images of each other.

5. 1 Script Analysis

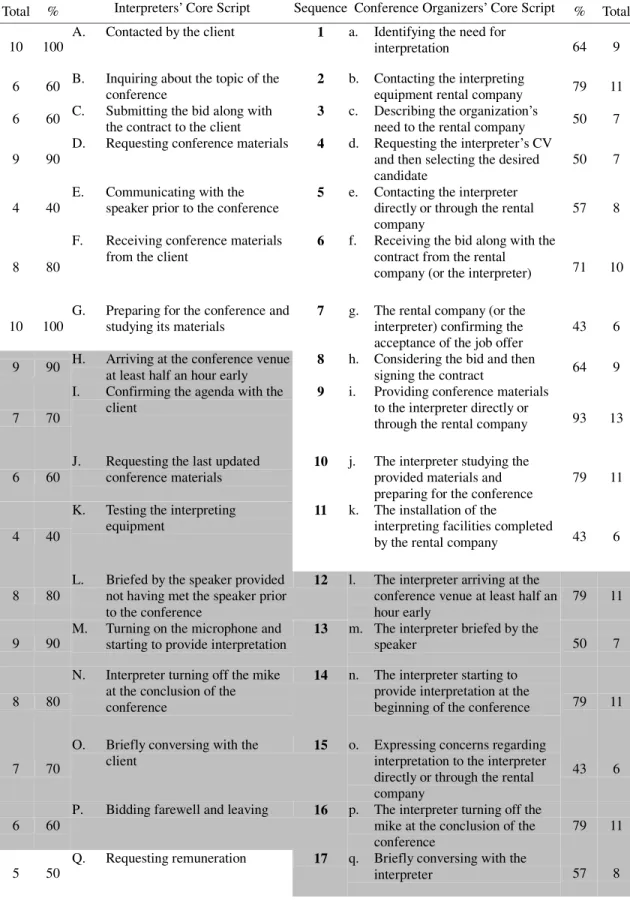

This section consists of two portions: identified discrepancies and congruencies between the general script of the conference organizers and that of the interpreters. These two portions are based upon the comparison and contrast of the general scripts as displayed in Table 5.1.

5. 1. 1 Discrepancy

As stated in the summary of the research results in the script project, the clients have a more elaborate general script than the interpreters with two more actions in it. This discovery, at first glance, seems contrary to the findings of Hubbert, Sehorn, and Brown (1995). Their investigation has proved that the service provider possesses a more elaborate script than the consumer because his/her script is acted out more often and also has to accommodate a greater variety of participants than the consumer. This assertion holds true when the conference organizers’ general script is closely examined. Their script involves two service

Table 5. 1 Comparison and Contrast of the General Scripts

Total % Interpreters’ Core Script Sequence Conference Organizers’ Core Script % Total 10 100 A. Contacted by the client 1 a. Identifying the need for

interpretation 64 9

6 60 B. Inquiring about the topic of the

conference 2 b. Contacting the interpreting

equipment rental company 79 11 6 60 C. Submitting the bid along with

the contract to the client 3 c. Describing the organization’s

need to the rental company 50 7 9 90 D. Requesting conference materials 4 d. Requesting the interpreter’s CV

and then selecting the desired

candidate 50 7

4 40 E. Communicating with the

speaker prior to the conference 5 e. Contacting the interpreter directly or through the rental

company 57 8

8 80

F. Receiving conference materials

from the client 6 f. Receiving the bid along with the contract from the rental

company (or the interpreter) 71 10

10 100 G. Preparing for the conference and

studying its materials 7 g. The rental company (or the interpreter) confirming the

acceptance of the job offer 43 6 9 90 H. Arriving at the conference venue at least half an hour early 8 h. Considering the bid and then

signing the contract 64 9

7 70

I. Confirming the agenda with the

client 9 i. Providing conference materials

to the interpreter directly or

through the rental company 93 13

6 60 J. Requesting the last updated

conference materials 10 j. The interpreter studying the provided materials and

preparing for the conference 79 11

4 40

K. Testing the interpreting

equipment 11 k. The installation of the

interpreting facilities completed

by the rental company 43 6

8 80 L. Briefed by the speaker provided not having met the speaker prior to the conference

12 l. The interpreter arriving at the conference venue at least half an

hour early 79 11

9 90 M. Turning on the microphone and

starting to provide interpretation 13 m. The interpreter briefed by the

speaker 50 7

8 80

N. Interpreter turning off the mike at the conclusion of the conference

14 n. The interpreter starting to provide interpretation at the

beginning of the conference 79 11

7 70

O. Briefly conversing with the

client 15 o. Expressing concerns regarding

interpretation to the interpreter directly or through the rental company

43 6

6 60 P. Bidding farewell and leaving 16 p. The interpreter turning off the mike at the conclusion of the

conference 79 11

5 50 Q. Requesting remuneration 17 q. Briefly conversing with the

interpreter 57 8

Total % Interpreters’ Core Script Sequence Conference Organizers’ Core Script % Total 5 50 R. Paid by the client 18 r. Paying the interpreter

50 7 19 s. The rental company collecting

the payment from the conference

organizer 50 7

20 t. Paying the rental company

50 7

providers—the interpreter and the interpreting equipment rental company whereas the college students’ haircut script in the study of Hubbert et al. only includes one. If the base actions designed exclusively for interaction with the rental company—i.e., Actions b, c, k, t—were taken out of the clients’ script, it would be shorter than the interpreters’.

Assessing elaborateness of the general script in another aspect—the reported actions during the conference—may also confirm that the interpreter has a more detailed mental representation for interpretation services than the client. While the interpreters’ on-site service activities include nine components from early arrival at the conference to departure after saying goodbye, the clients’ consists of six events from the interpreter’s early arrival to a brief conversation with him/her. Such difference spells out unfulfilled expectations or

undesirable performances, and may give rise to customer dissatisfaction or fruitless

investment in unappreciated benefits (Hubbert et al., 1995). Therefore, incongruence between the two general scripts is further analyzed in the following paragraphs.

The first incongruence in actions, chronologically, is the time for entrance into the script of interpretation services. Namely, the clients’ general script and that of the interpreters start at different points in time. The interpreters enter into their script than the clients do at a much later stage when the clients are already done with their fourth step—requesting the interpreter’s CV and then selecting the desired candidate. Hubbert, Sehorn and Brown (1995) and Ling (2000) have also identified the difference in points of script activation. Hubbert et al.

further argued that it signifies a potential source of client dissatisfaction and advise the

service provider to start attending to clients the moment their scripts are put into action.

However, shifting the focus back on the general script for interpretation services, this study finds that their argument and advice may not be completely applicable in the context of conference interpreting, for their scripts were operated by only two parties in a generic services industry, the hairdresser and the haircut consumer whereas in this study the clients’

script involves three major characters—the interpreter, the interpreting equipment rental company, and themselves. The first four actions in the clients’ script are directed towards interaction with the interpreting rental company. However, the fourth step might be considered the precursor of contacting the interpreter, and thus calls for the interpreter’s attention. The interpreter’s general script, nevertheless, does not include any response to the client’s request for his/her CV. Therefore, it may be inferred that at the very early stage of the client’s script, the only potential source of client dissatisfaction as a result of discrepancy in expectations is for interpreters not having their résumés ready. The interpreter does need to include one more step, “preparing the CV for the client’s reference”, in their script, and it would be better for them to activate his/her script with this step.

The first four steps, which lack reciprocation from the interpreters, also indicate significance of the client’s search process for interpretation services. Instead of directly seeking out individuals to interpret, half of the conference organizers hire interpreters through a rental company. There might be two reasons. First, since the client has to deal with the rental company for interpreting facilities as indicated in the script and the rental company also works alongside interpreters at conference frequently, s/he might as well engage in one-stop shopping. Second, customers of professional services undertake greater financial risks than those of generic services and thus rely to a great extent on referrals and personal recommendations (Hill & Neely, 1988). Simply put, quite a few clients prefer business engagement with the rental company because it satisfies their needs and assumes part of

responsibilities for success or failure in interpretation, as suggested by Client No. 13. Given such customers’ purchasing behavior, interpreters should include the rental company in their scripts and establish a closer relationship with it for more business prospects. On the other hand, judging from the background information provided by the interpreters, most

interpreters still manage to make a living with a small portion of assignments from the rental company, since only the three senior interpreters receive more than 50% of interpretation cases from it. However, should this trend persist and spread among conference organizers, interpreters may need to formulate strategies to cope.

In addition to difference in the script’s opening in terms of time and action, some more discrepancies are found along the timeline of interpretation services. They are herein

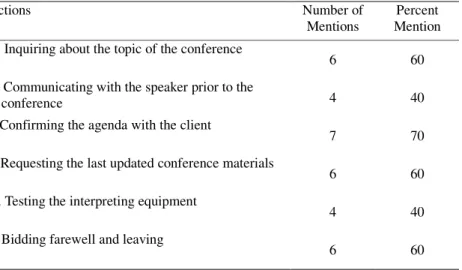

approached from the perspectives of both the clients and the interpreters. The clients’ general script has nine actions excluded from the interpreters’ general script, as shown in Table 5.2;

on the other hand, six of the interpreters’ actions are not included in the clients’ script, as shown in Table 5.3.

Table 5. 2 The Clients’ Actions Excluded from the Interpreters’ General Script

Actions Number of

Mentions Percent Mention a. Identifying the need for interpretation 64 9 b. Contacting the interpreting equipment rental

company 79 11

c. Describing the organization’s need to the rental

company 50 7

d. Requesting the interpreter’s CV and then selecting

the desired candidate 50 7

g. The rental company (or the interpreter) confirming

the acceptance of the job offer 64 9

k. The installation of the interpreting facilities

completed by the rental company 43 6

o. Expressing concerns regarding interpretation to the interpreter directly or through the rental

company 43 6

s. The rental company collecting the payment from

the conference organizer 50 7

t. Paying the rental company 50 7

Even though the client has nine actions that are left out of the interpreters’ general script, the interpreter does not have to or cannot be involved in all these actions; however, s/he does need to pay attention to three of them—Actions d, g, and o, as painted in gray in Table 5.2. Action d has been discussed in previous paragraphs, and repetition is avoided here.

Actions g and o are analyzed as follow.

Action g—the rental company (or the interpreter) confirming the acceptance of the job offer precedes contract signing between the interpreter and the client. By submitting the bid

and a contract for the interpretation case the interpreter has confirmed acceptance of the job offer or at least demonstrated their interest in it. However, the contract basically forbids the client from looking for alternatives. Should the selected interpreter be unable to show up with a very short notice, the conference organizer may have to settle for any one that is available, be s/he desirable or not, to avoid dysfunction of the conference. Therefore, some clients may feel more secure with a double-check of the interpreter’s availability before getting bound by the contract. A phone call by the interpreter to reiterate his/her interest can easily bridge this gap in expectations.

Action o—expressing concerns regarding interpretation to the interpreter directly or through the rental company is inserted amid the beginning and the end of the interpretation.

According to the individual scripts of the six conference organizers who reported this action, clients’ concerns may include inadequate volume, faulty use of terminology, improper speed, etc. However, according to the interpreters’ master list of individual scripts, only Interpreters No. 8 and 9 anticipate that the conference organizer will have something to say, such as comments on use of terminology. In the terminology of the CIT studies conducted by Bitner et al. (1990; 1994), when voicing their concerns to the interpreter, the client is expecting the interpreter’s proper response to service delivery system failures or asking the interpreter to accommodate his/her needs or requests. When this action in fact does not exist in the

interpreters’ general script, it suggests that the interviewed interpreters may not have familiarized themselves with responding to failures in interpretation or accommodating the client’s special needs. However, this probability requires further investigation. Interpreters’

unscripted responses on the spot might be less prudent in nature, and this study infers that they are more likely to give rise to client dissatisfaction.

One may wonder why Action o—expressing concerns is woven into the clients’ general script in the first place. Even though the actual interpreting process is represented by only two actions in the script, it is the reason that interpreters are hired. Regardless of the interpreter’s professional competence, mishaps do happen. The client’s entire script to achieve

cross-language communication nearly means nothing when the interpreter fails to deliver interpretation in a desirable manner. Therefore, Action o—expressing concerns serves as a contingency or a corrective action to assure the completion of the script and achievement of the clients’ purpose, as suggested by Schank and Abelson (as cited in Hubbert et al., 1995).

This means the client makes comment on the interpretation to make sure the interpreting event will be completed in the way s/he expects. Indeed, based on the collection of

dissatisfactory incidents in this study, some interviewed clients have experienced significant failure in interpretation in the past, so they routinely express concerns about interpreting quality. However, only six clients out of fourteen have included this action in this script. It is, therefore, possible that most interviewed clients have not experienced serious disruptions in interpretation.

Improved satisfaction is the ultimate goal of the script analysis. By examining the actions in the clients’ general script that are neglected by the interpreters, this study has identified unfulfilled expectations, which are considered a potential source of client dissatisfaction (Alford, 1998). These unfulfilled expectations are manifested in three

goal-directed actions: requesting the interpreter's CV, confirming the interpreter’s acceptance

of the job offer, and expressing concerns regarding interpretation to the interpreter. However, even though shedding light on what clients’ expectations have not been met is essential to the script analysis, it would not be complete without determining the necessity of the interpreters’

actions unexpected by the conference organizers. If theses actions are indeed indispensable, along comes the need to elucidate their intended benefits to the client.

In order to determine if the interpreters’ six excluded actions, as displayed in Table 5.3, are necessary, this study bases its judgment on AIIC’s Practical Guide for Professional Conference Interpreters (1990) and Checklist for Conference Organizers (1992), for they have been published to contribute to, as proclaimed, “high standards of professionalism and quality interpretation”. These six actions are Actions B—conference topic inquiry,

E—pre-conference communication with the speaker, I—agenda confirmation, J—request for updated materials, K—equipment testing, and P—farewell bidding. In close examination, all the actions, except Action I—agenda confirmation, have been elaborated upon in at least one of these two documents, and thus have their existences justified. In addition to the

endorsement by an interpreter’s professional association, two of the five actions, Actions J—request for updated materials and K—equipment testing, may contribute to client satisfaction based on the CIT research results of this study. In the satisfactory incident provided by Client No. 5, the interpreter was considered having a “proactive attitude”

because he requested the latest presentation materials. Action J—request for updated materials constitutes as positive deviation from the client’s script, which enhances customer satisfaction (Alford, 1998). On the other hand, no collected data can verify the status of Action K—equipment testing as a satisfaction booster; however, evidence does exist that its absence from the script may be a satisfaction buster. In the dissatisfactory incident provided by Client No. 1, the interpreters put on a scene for blatantly complaining of the interpreting equipment to the technician, which upset the client because it drew unnecessary attention

from the audience. The client did not mention if the interpreters tested the interpreting equipment prior to the conference or not, but at least doing so may increase the odds of identifying the problem earlier and preventing subsequent dissatisfying development. As for Action E—pre-conference communication with the speaker, the conference organizer may have a good reason for not being able to cooperate because many speakers arrive in Taiwan almost in the last minute and may suffer from the jet lag or have other engagements of higher priorities to attend to. Since this action was mentioned in just enough interviews to qualify as a base action in the general script and its purpose may be achieved to a certain extent by Action L—briefed by the speaker, the interpreter may drop it from the script.

Table 5. 3 The Interpreters’ Actions Excluded from the Clients’ General Script

Actions Number of

Mentions Percent Mention B. Inquiring about the topic of the conference

6 60

E. Communicating with the speaker prior to the

conference 4 40

I. Confirming the agenda with the client

7 70

J. Requesting the last updated conference materials

6 60

K. Testing the interpreting equipment

4 40

P. Bidding farewell and leaving

6 60

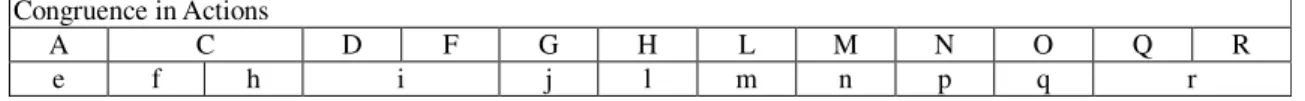

5. 1. 2 Congruency

Despite the aforementioned discrepancies in the general scripts of the conference organizers and the interpreters, these two scripts are very similar to each other. The result of the matching process reveals that of all the eighteen actions in the interpreters’ general script, twelve have either an identical twin or corresponding action in the clients’ script, and so do

eleven of all the fourteen actions in relation to the interpreter (with Actions a, b, c, k, r and t taken out from the client’s general script), as demonstrated in Table 5.4 and Table 5.5. This means the expectations of both the interpreters and conference organizers have been operationalized by the script methodology, and the script analysis suggests that 66.66%

(12/18) of the interpreters’ expectations would be met by the conference organizers, and 78.57% (11/14) of the conference organizers’ by the interpreters. Based on the review of literature, congruency of the service delivery process and the clients’ general script indicates customer satisfaction. However, this study, at this point, still cannot decide whether a 78.57%

fulfillment of the clients’ expectations is high enough, and thus cannot determine whether the clients would be satisfied or not. To deepen the understanding of potential sources of client satisfaction and dissatisfaction, this study, thus, turns to the CIT research project for complementary answers.

Table 5. 4 Congruence in Actions

Congruence in Actions

A C D F G H L M N O Q R

e f h i j l m n p q r

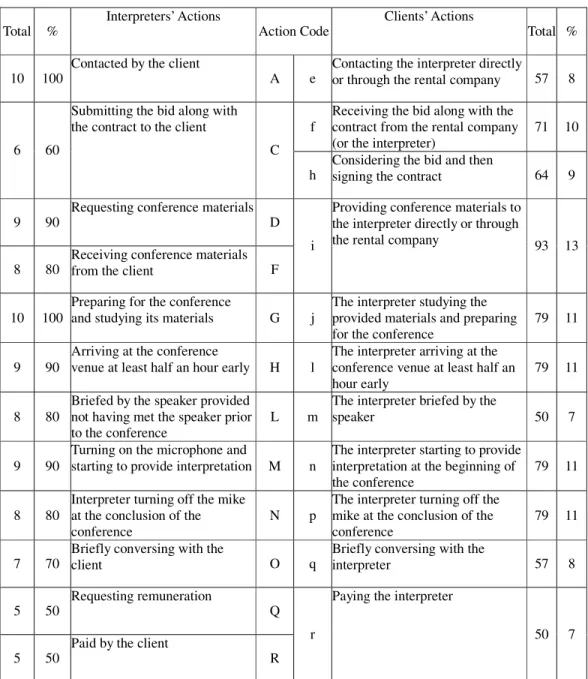

5. 1. 3 The involvement of the interpreting equipment rental company

The clients’ general script includes nine actions that are excluded from the interpreters’

general script. These actions are Actions a—need identification, b—contacting equipment company, c—need description, d—request for CV, g—acceptance confirmation, k—facility installation, o—expressing concerns, s—payment collection, and t—paying the rental. As discussed in the previous portion, the interpreter may have to incorporate Actions d, g, and o

to improve client satisfaction. The other six actions are in fact directed to the rental company.

Based on the results in Chapter 4, these six actions all have their corresponding actions in the equipment rental company. The rental company not only passively waits for business

opportunities, but also actively seeks organizations that may need interpretation, which takes care of Actions a and b. It also inquires the clients about their needs, completes installation of interpreting facilities prior to the conference, collects payment and receives it from the client, which corresponds to Actions c, k, s, and t. Moreover, it even provides the interpreter’s CV.

Therefore, if a client recruits interpreters through a rental company, the interpreter and the rental company as a service team can almost meet all his/her expectations manifested in the script. However, the service team still needs to confirm the interpreter’s availability and pay attention to the clients’ concerns regarding interpretation quality.

Table 5. 5 Detailed Congruence in Actions

Total % Interpreters’ Actions

Action Code Clients’ Actions

Total %

10 100 Contacted by the client

A e Contacting the interpreter directly

or through the rental company 57 8

f Receiving the bid along with the contract from the rental company

(or the interpreter) 71 10 6 60

Submitting the bid along with the contract to the client

C

h Considering the bid and then

signing the contract 64 9

9 90 Requesting conference materials D

8 80 Receiving conference materials

from the client F

i

Providing conference materials to the interpreter directly or through

the rental company 93 13

10 100 Preparing for the conference

and studying its materials G j The interpreter studying the provided materials and preparing

for the conference 79 11

9 90 Arriving at the conference

venue at least half an hour early H l The interpreter arriving at the conference venue at least half an

hour early 79 11

8 80 Briefed by the speaker provided not having met the speaker prior

to the conference L m The interpreter briefed by the

speaker 50 7

9 90 Turning on the microphone and

starting to provide interpretation M n The interpreter starting to provide interpretation at the beginning of

the conference 79 11

8 80 Interpreter turning off the mike at the conclusion of the

conference N p The interpreter turning off the mike at the conclusion of the

conference 79 11

7 70 Briefly conversing with the

client O q Briefly conversing with the

interpreter 57 8

5 50 Requesting remuneration

Q

5 50 Paid by the client

R r

Paying the interpreter

50 7

5. 2 CIT Analysis

This section comprises three major portions. For the first two portions, based on the research results presented in Chapter 4 a comparison and contrast is drawn between the viewpoints of the clients and the interpreters first on satisfactory incidents, and then on dissatisfactory incidents. The last portion summarizes the first two portions and attempts to determine whether the underlying events and behaviors that result in client satisfaction and dissatisfaction with interpretation services are opposites or mirror images of each other.

Throughout this section, attribution theory is used to interpret all the comparison and contrast.

5. 2. 1 Satisfactory experience with interpretation services 5. 2. 1. 1 Service theater

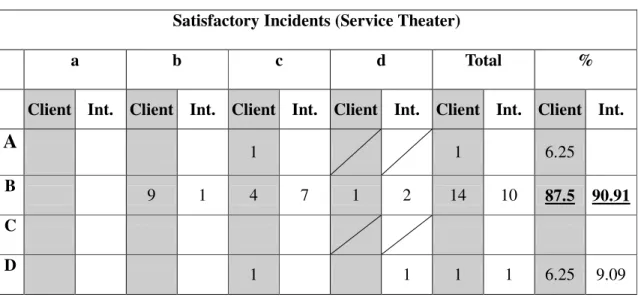

A combination of the sorting results of satisfactory incidents with the Service Theater Classification Scheme, as shown in Table 5.6, enables the study to compare and contrast more easily the underlying events and behaviors that triggered client satisfaction with interpretation services. The four row headings—A, B, C, and D—respectively denotes Group A—Setting, Group B—Actors, Group C—Audience, and Group D—Performance in the Theater scheme.

The four lower-case-lettered column headings represent the categories under each group. The clients’ results and the interpreters’ are placed side by side.

Group B—Actors gathers 87.5% of satisfactory incidents told by the clients and 90.91% of those told by the interpreters, which makes it the overwhelmingly predominant group from the viewpoints of both parties. This suggests satisfaction is mainly considered, regardless of perspectives, to derive from the interpretation services personnel. Despite convergence in major grouping, these two groups of respondents differ in sub-categorization.

Of all the fourteen accounts told by the clients assigned to Group B, nine fall into Category b—the attitudes and behavior of the service provider, while seven of all the nine incidents provided by the interpreters belong to Category c—the level of excellence of the service provider’s technical skills. This difference indicates that most conference organizers think that they were pleased with interpretation services because of the interpreter’s attitudes and behavior instead of the interpreters’ interpreting skills, but most interpreters suspect that they pleased the conference organizers with their professional excellence in interpreting.

Table 5. 6 Comparison of the Clients’ and Interpreters’ Satisfactory Incidents Sorted with the Service Theater Classification Scheme

Satisfactory Incidents (Service Theater)

a b c d Total %

Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int.

A 1 1 6.25

B 9 1 4 7 1 2 14 10 87.5 90.91

C

D 1 1 1 1 6.25 9.09

5. 2. 1. 2 BBTM

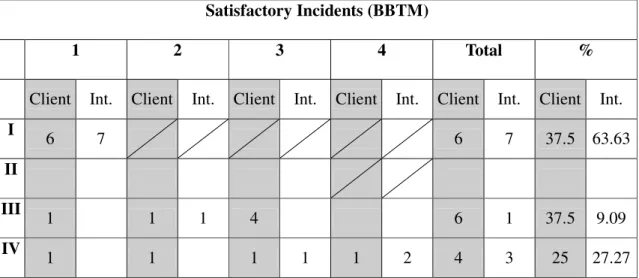

As is done with the sorting results of satisfactory incidents with the Theater scheme, Table 5.7 is drawn to compare and contrast the perspectives of the clients and the interpreters.

The four row headings—I, II, III, and IV—respectively denotes Group I—Holistic evaluation, Group II—Core service failure, Group III—Customer needs and requests, and Group

D—Provider’s voluntary actions in the BBTM scheme. The four column Arabic-numeral

headings represent the categories under each group. The clients’ results and the interpreters’

are placed side by side.

Table 5. 7 Comparison of the Clients’ and Interpreters’ Satisfactory Incidents Sorted with the BBTM Classification Scheme

Satisfactory Incidents (BBTM)

1 2 3 4 Total %

Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int.

I 6 7 6 7 37.5 63.63

II

III 1 1 1 4 6 1 37.5 9.09

IV 1 1 1 1 1 2 4 3 25 27.27

When sorted by the BBTM Classification Scheme, a majority of the interpreter’s incidents still concentrate in one particular group—Group I (63.63%), whereas the clients’

spread into three groups quite evenly—Group I (37.5%), Group III (37.5%), and Group IV (25%). This magnifies the divergence in attribution of success in interpretation services. With the concentration of their reported incidents in Group I, it can be inferred that the interpreters believe that client satisfaction with their services originated from success in delivery of the core service, i.e., trouble-free interpretation. However, judging from the fairly equal

representations of Groups I, III, and IV among the clients, this study suspects that it is just as likely for clients to have felt satisfied with interpretation services because their special needs and requests were taken good care of by the hired interpreter as because the interpreters had done a good job in interpreting. Of all the six incidents reported by the clients in Group III, four have been assigned to its Category 3. This suggests that the clients might have felt

satisfied especially because of the interpreter’s positive responses to their mistakes, such as changing the conference venues (CS2), providing insufficient or inadequate conference materials (CS5 & CS11) and overworking the interpreter (CS10-1).

5. 2. 1. 3 Comparison of results in the two classification schemes

The results of comparison in the BBTM scheme are very consistent with those in the Theater scheme. This consistency suggests that while both the clients and the interpreters perceived success in interpretation to be the source of client satisfaction, the clients were even more likely to have felt satisfied because of the interpreters’ serving attitudes, such as forgiving, patient, considerate, attentive, accommodating, and other personal attributes mentioned in clients’ satisfactory incidents.

In addition, both schemes have an empty group without any incidents provided by the conference organizers or the interpreters. For the Service Theater, it is Group C—Audience.

This implies that the interpreters did not consider their clients to have contributed to

satisfactory services, and the interviewed clients did not take the credit for memorable service experiences, either. However, both classification schemes have identified the interpreters’

predominant attribution of satisfactory service experience to their successful interpretation.

Such difference conforms to the argument of Bitner, Booms and Mohr (1994) that even though both the service provider and customer would give themselves the credit for the success, according to attribution theory, the fact that the customer is paying to have a service would reduce their likelihood for doing so. For the BBTM, it is Group II—Core service failure. This suggests interpretation did not fail in any of the satisfactory incidents, be they told from the interpreters’ perspective or the clients’. This verifies that enjoyable

supplementary services, such as translation of urgent documents (CS8 & IS8) or the interpreter’s engagement in any kind of non-interpreting activities, boost the client’s

satisfaction, which must be established on the premise that the core service does not fail (Lovelock, 2001).

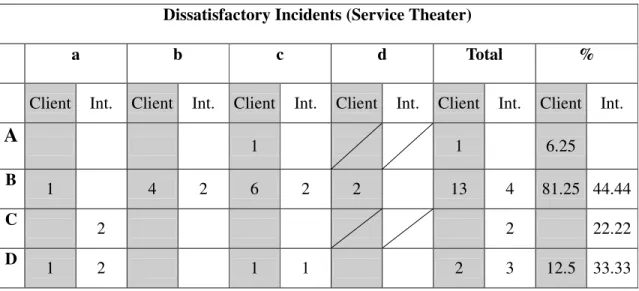

5. 2. 2 Dissatisfactory experience with interpretation services 5. 2. 2. 1 Service theater

As seen in Table 5.8 Group B—Actors garners most dissatisfactory incidents reported by both the clients and the interpreters in the Theater scheme. However, its predominance among the clients’ incidents is overwhelming as much as 81.25% with a difference of 68.75%

between it and the second largest group, Group D—Performance, whereas among the interpreters’ incidents it only prevails with a 44.44% of representation over the next largest group by a narrow margin of 11.11%. This means of both the clients and interpreters, most ascribed client dissatisfaction to the interpretation services personnel, but as much as 55.55%

of dissatisfaction was attributed to two other groups, Group III—Audience (22.22%) and Group IV—Performance (33.33%), by the interpreters. Such difference suggests that the clients think that the personnel ought to be responsible for their frustration, but more than half the interviewed interpreters did not claim responsibility for their clients’ displeasure in their portrayals of the situation. According to the interpreters, client dissatisfaction stemmed from the conference organizers’ unwillingness to cooperate (ID3 &ID6), one-time performance inflicted by misfortune (ID5 & ID7), or the problematic system design of interpretation services (ID10).

A closer examination of the dissatisfactory incidents in Group B—Actors reveals that even when both parties considered client dissatisfaction derived from the interpreter, their opinions regarding the specific source differed. Placement in Categories b and c indicates dissatisfaction as a result of, respectively, the disliked attitudes and behavior of the services personnel, and their dismal professional skills. Four of the clients’ thirteen incidents in Group

B belong to Category b, and six to Category c; the ratio is 2:3. Of the interpreters’ four incidents in Group B, half belong to Category b, and the other half to Category c; the ratio is 2:2. This suggests the clients were more sensitive to inept interpreters than undesirable attitudes.

Table 5. 8 Comparison of the Clients’ and Interpreters’ Dissatisfactory Incidents Sorted with the Service Theater Classification Scheme

Dissatisfactory Incidents (Service Theater)

a b c d Total %

Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int.

A 1 1 6.25

B 1 4 2 6 2 2 13 4 81.25 44.44

C 2 2 22.22

D 1 2 1 1 2 3 12.5 33.33

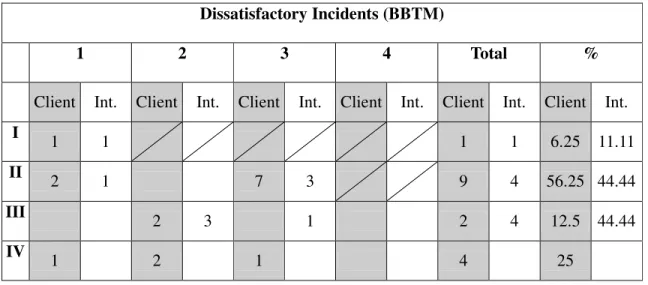

5. 2. 2. 2 BBTM

The sorting results with the BBTM scheme, as shown in Table 5.9, still place one particular group in a dominant position among the incidents reported by both the interpreters and the conference organizers. Group II—Core service failure contains 56.25% ( 50%) of the clients’ dissatisfactory incidents, and 44.44% ( 50%)of the interpreters’. The dominance of Group II among all the dissatisfactory incidents suggests the greatest contributing factor of client dissatisfaction is failure in interpretation, especially for the clients with its 56.25%

representation. However, among the interpreters’ incidents exists an equal representation, Group III—Customer needs and requests, which means the clients in these incidents were

dissatisfied because the interpreters did not give in to their requests or put up with their mistakes, such as participation in the rehearsal (ID1), recruitment of experienced interpreters with a meager pay (ID2), inferior working conditions (ID6), or on-line broadcasting of interpretation (ID3). On the other hand, despite the inclination towards Group II, among the conference organizers’ incidents exists a significant minority as well, Group IV—Provider’s voluntary actions (25%). The clients blamed the services personnel for initiating their

discontent. For example, the service provider did not pay enough attention to the client (CD4), appeared nonchalant (CD11-1 & CD12-1), or broke their promise (CD5).

Table 5. 9 Comparison of the Clients’ and Interpreters’ Dissatisfactory Incidents Sorted with the BBTM Classification Scheme

Dissatisfactory Incidents (BBTM)

1 2 3 4 Total %

Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int. Client Int.

I 1 1 1 1 6.25 11.11

II 2 1 7 3 9 4 56.25 44.44

III 2 3 1 2 4 12.5 44.44

IV 1 2 1 4 25

5. 2. 2. 3 Comparison of results in the two classification schemes

The results of comparison in the BBTM scheme converge with those in the Theater scheme in that failure in interpretation prompted most client dissatisfaction from the

perspectives of both the clients and interpreters, but in the eye of the interpreters, the clients were just as likely to inflict dissatisfaction upon themselves for being uncooperative (ID3) or unreasonably demanding (ID1, ID2, & ID6).

The results in the BBTM scheme and the Theater scheme have another thing in common. Both have an empty group: Group C—Audience of the Theater scheme from the clients’ perspective, and Group IV of the BBTM scheme—Providers’ voluntary actions. This means that neither of them thought they took the initiative to upset the service. Attribution theory may help to interpret this finding. People shirk responsibility for failure—a

self-protecting bias. Therefore, both the interpreter and client are not very likely to report dissatisfactory incidents as a result of their own mistakes.

5. 2. 3 Summary

The first portion of the CIT analysis reveals that both the clients and interpreters both perceived success in interpretation to be a major source of client satisfaction, but even more of the clients felt satisfied because of the interpreters’ positive serving attitudes rather than their professional skills. Moreover, none of the satisfactory incidents involved failure in interpretation. This finding enables this study to further assert that the clients were satisfied because of success in interpretation as a premise to be topped off by the interpreters’

commendable serving attitudes.

The second portion demonstrates failure in interpretation was bound to result in client dissatisfaction, but the interpreters also recognized client dissatisfaction was at times self-induced because of the clients’ unwillingness to cooperate and unreasonable requests.

In these two portions, both the clients and interpreters attributed satisfaction with interpretation services to the interpreters (themselves) either for their attitudes or for their professional skills. In the case of a dissatisfactory encounter, neither of them admitted to taking the initiative to upset the service. The clients pointed their fingers of blame at the interpreters’ ineptness while the interpreters’, though not as vehemently, also accused the clients of being uncooperative and unreasonably demanding. These findings verify the

predictions of attribution theory—people tend to take credit for success, and shirk

responsibility for failure, and such attribution bias is more obvious in failure than in success situations (Bitner et al. 1994).

These two portions together have identified the interpreter as the primary source of both client satisfaction and dissatisfaction, contributing either by their professional skills and serving attitudes. First, the professional skills determined the success or failure in

interpretation, and then serving attitudes boosted client satisfaction. If an interpretation was trouble-free and moreover the interpreter served with a pleasant attitude, the client was bound to feel satisfied, but if an interpretation raised the client’s eyebrows, the services would surely upset him/her regardless of serving attitudes. Commendable serving attitudes coupled with excellent interpretation are the key to client satisfaction, whereas dismal interpretation solely leads to client satisfaction. A conclusion may be drawn that the underlying events and behaviors that result in client satisfaction and dissatisfaction with interpretation services are opposites of each other.