214

The Development of Given/New Interpretation

by Taiwanese EFL University Students and Its Pedagogical

Implications

Shu-Hui Eileen Chen (陳淑惠) Shu-Huang Tseng (曾淑凰) Yin-Ling Tsao(曹尹齡) National Taipei of University of Education

National Taipei of University of Education National Taipei of University of Education

Abstract

From functionalist viewpoint, language acquisition is considered a process to

map surface linguistic cues unto function. Based on the Competition Model, this study investigated how Taiwanese EFL university students with lower and higher L2 proficiency level utilize surface cues of word order, cleft structure, animacy, and focal accent for Given and New interpretation. Three groups of subjects participated in this study: 20 Taiwanese EFL university students with lower English proficiency, 20 Taiwanese EFL university students with higher English proficiency, and 20 monolingual English native speakers. The result indicated that: (1) both EFL groups effectively utilized word order cue; (2) the higher proficient group, but not the lower proficient group, could make use of cleft structure for Given and New interpretation; (3) when animacy competed with word order, both EFL groups relied more on word order; when animacy competed with cleft marked structure, unlike NES, both EFL groups preferred animacy to cleft syntax; (4) when focal accent competed with word order, both EFL groups relied more on word order like NES, though there was significant difference in the extent of reliance between LEP and NES; when focal accent competed with cleft, HEP, but not LEP, displayed preference for cleft cue, as NES did. (5) When focal accent converged with other cues, both EFL groups didn’t respond consistently; (6) when focal accent conspired with animacy over word order, both EFL groups were inclined to rely on word order; while in the condition when focal accent conspired with animacy over cleft, they responded to cleft structure nonuniformly. The findings were discussed from linguistic, psycholinguistic, developmental and pragmatic perspectives, with pedagogical implications provided for EFL teaching and learning.

INTRODUCTION

215

(MacWhinney, 1987; MacWhinney, 2002; MacWhinney, 2005). From this perspective, language acquisition can be considered a process to master substantial underlying Given and New with linguistic surface cues (Ellis, 2008). Natural languages and communication channels utilize specific linguistic cues to interpret Given/New information. For example, later occurring part in actives, post-copular element in clefts, and the element carrying heaviest stress frequently served as New indicators (LaPolla, 1993; Prince, 1985).

Based on the Competition Model, language is assumed to map form unto function in many to many fashions at the level of prosody, syntax, and semantics in processing (Bates & MacWhinney, 1989). A number of cross-linguistic studies on agent (subject)/patient (object) identification have reported different patterns in the use of surface cues by adults and children, such as in English, Chinese, German, Italian, and Japanese (Bates, McNew, MacWhinney, Devescovi & Smith, 1982; Clancy, 1985; Kail, 1989; MacWhinney, Bates, & Kliegl, 1984; Li, Bates, & Liu, 1992; Miao, 1981; Su, 2001; Sun & Givon, 1985). The outcome indicated that there were crosslinguistic differences in cue strength. For example, in English, word order is stronger than animacy, and agreement is stronger than stress in agent/patient assisnment; in Italian the hierarchy of the importance of cues is, in the descending order, agreement, animacy, word order, stress; in Chinese, animacy is stronger than word order; in Hungarian, case marking is the strongest cue, compared with agreement and animacy. For pragmatic interpretation of Given/New, native English-speakers rely more on the marked cleft structure than native Chinese speakers (Chen, 2006), when semantics is in competition with marked cleft structure, native Chinese-speakers rely more on semantics while native English speakers rely more on cleft marked structure (Chen 1996, 1998, 2006).

216

linguistic surface cues with Given and New in pragmatic comprehension. Likewise, studies of Chinese and English in L2 processing also indicate that the developmental patterns might vary as a function of language proficiency (Chen & Chen, 2006; Su, 2001). For example, Su (2001) indicated that the advanced EFL learners show great resemblance in employing word order like native English speakers, as compared with beginning and intermediate learners. Instead of word order cue, the beginning and intermediate EFL learners preferred to rely on animacy cue in the interpretation of sentence. Furthermore, Su also provided the evidence that CFL learners transferred word order strategies in L1 to interpret L2 Chinese sentence, regardless of their language proficiency. Albeit they might become aware of animacy cue in the interpretation of NNV with the increase of proficiency, they still rely on word order heavily in processing. In the studies of English-Chinese and Chinese-English bilinguals, Liu et al. (1992) investigated the role of age of exposure in the development of sentence interpretation by English-Chinese and Chinese-English bilinguals. Liu et al. noted that CFL are more inclined to use word order cue significantly in L2 processing as animacy cue competes with word order cue. It was further found that late English-Chinese bilinguals transferred English-like word order strategies to Chinese and late Chinese-English bilinguals transferred animacy-based strategies to English sentences in identification of agent/patient relations. However, early bilinguals displayed a variety of transfer patterns, including use of animacy strategies in Chinese and word order strategies in English or use of L2 processing strategies in L1.

217

218

when the copula shi is stressed as in the phrase jiushi

To date, within the Competition Model framework, most studies were focused on syntactic interpretation of agent and patient (Su, 2001, 2004), with limited number of studies done on pragmatic interpretation (Chen & Chen, 2006; Chang, 2008) on EFL children. Given differences along linguistic and cognitive factors between children and adults (Brown, 1980), to better understand L2 sentence interpretation, more studies on pragmatic interpretation for Given and New information in adult L2 learners would be valuable. The present study intended to investigate how Taiwanese EFL university students with different L2 proficiency levels utilized surface cues, including word order, cleft structure, animacy, and focal accent, to identify Given and New information in sentence processing. The research questions that were addressed are as follows: (1) How do Taiwanese EFL university students with lower English proficiency utilize surface cues, including word order, cleft syntax, animacy, stress, to identify Given and New information? (2) How do Taiwanese EFL university students with higher English proficiency utilize surface cues, including word order, cleft syntax, animacy, stress, to identify Given and New information? (3) What are the similarities and differences in the development of Given and New interpretation between Taiwanese EFL university students with lower and higher English proficiency?

‘suit copula (literal meaning)’ “It exactly is”, the following element tends to convey Given information in non-copular sentences (Teng, 2005). As Ladd (1996), and Gussenhoven (2004) noted, the perception of prosodic prominence depends on people’s sensitivity to construct the correct phonological contrasts in prosodic structures. In Mandarin Chinese, there is intricate interplay between sentence form, intonation and stress, and more importantly, perception factor may thus come into play to affect Given/New differentiation in Mandarin Chinese. Another difference in cleft construction between English and Chinese is that unlike English cleft, a cleft focus in Chinese may, but need not, represent New information though it must receive a contrastive interpretation (Xu, 2006). Given the phonological attributes of the marker shi in Mandarin Chinese and the function of clefts, the reliability of the focus marker shi as pre-focusing New information marker is not that reliable in Mandarin Chinese as that in English. In view of the qualitative and quantitative differences, when learning English as a foreign language, Taiwanese EFL university students may encounter difficulties getting accostumed to the mapping of surface forms and Given/New in English.

METHODOLOGY

219

data collected for Dr. Shu-hui Chen’s NSC research project (NSC97-2410-H-152-008), funded by National Science Council, Taiwan. The methods are presented as follows: Subjects

Subjects in the present study are grouped into three groups: 20 Taiwanese EFL university students with lower English proficiency (hereafter LEP), 20 Taiwanese EFL university students with higher English proficiency (hereafter HEP), and 20 monolingual English native speakers (hereafter NES)

EFL adult learners were recruited from National Taipei University of Education. EFL adult learners with lower proficiency were undergraduates or graduates whose English proficiency was placed at intermediate level based on General English Proficiency Test (GEPT) in Taiwan. EFL adult learners with higher proficiency were English-majoring undergraduates and graduates whose English proficiency level was above higher-intermediate level based on their scores of GEPT.

Monolingual English native speakers participated in sentence verification task in their native language only. Their performance served as a standard reference point which was used to examine the language performance in Taiwanese EFL university students.

Stimuli

The stimuli sentences were composed of two sentence types--actives and clefts, in which animacy and stress were manipulated. Sentence types were constructed around two semantic conditions: animate agent/verb/ animate patient, such as The turtle chase the cat., and animate agent/verb/inanimate patient, such as The tiger pull the kite. Cleft marked sentences were also constructed around the two semantic conditions: animate agent/action/ animate patient, e.g., It is the turtle that chases the cat., and inanimate agent/action/animate patient, e.g., It is the clock that awakes the bird. Stress was constructed in three conditions: normal stress on the second NP, emphatic stress on the first NP, emphatic stress on the second NP. All the stimuli sentences included two nouns and one transitive verb. Since the accompanying pictures against which the stimulus was verified were presented with the stimuli, due to the mutual knowledge (Parrotte & Shina, 1987) of the visual content, definite nominals were used in sentences. This way, the local marking by article contrast was eliminated, and would not confound the interpretation of Given and New information. The use of surface cues of under consideration could thus be more rigorously measured.

220

New information. It was assumed that the latter part in actives with normal stress, the prosodic prominence, and the part in post-copular position in clefts serve as New. The hypothesis was that Given information would be assumed to be true, while New tends to be verified. All the target sentences were recorded by a native speaker of Chinese and English respectively.

Procedures

Subjects were visited on schedule and did the experiment in a quiet space.

Before the experiment, nouns and verbs in the target sentences were introduced with pictures in English to ensure that the subjects could understand all of them. Besides, they were also told to notice the misrepresentation between auditory stimuli and visual stimuli. For example, in English, the pair of the pictures describing “The turtle chases the rabbit” and “The monkey chases the cat” were presented, while they heard the stimuli “Does the turtle chase the cat?” .They were required to use the same structure of the stimulus, such as actives or clefts, to correct a part in auditory stimuli in accordance with picture they chose. Based on the prediction, they would answer the question with: “No, the turtle chased the rabbit” instead of “No, the monkey chased the cat.” by correcting the post-verbal element.

Before the experiment, two demonstrative trials were carried out to help them better understand the procedure. Subjects were first asked to do the experiment in English, and then in Chinese in order to further examine the potential transfer phenomenon. When the experiment was conducted, subjects listened to the tape, looked at the pictures, and gave their answers at the same time. It took each participant 30 minutes to complete the experiment.

Coding and data analysis

Every subject’s score was composed of the number of times when the element which tended to represent new information was verified, including the element occurring later in actives with normal intonation, the element carrying heavy stress, and the element located in post-copular position in cleft sentences.

After the collection of all data and summation of scoring were done, the data were treated statistically as with four factors (proficiency, sentence type, animacy, and stress). ANOVAs with repeated measures (sentence type, animacy, and stress) were conducted to denote the significance in the main effects and interaction variables. The significance was considered at the level of 0.5.

Results and Discussion

221

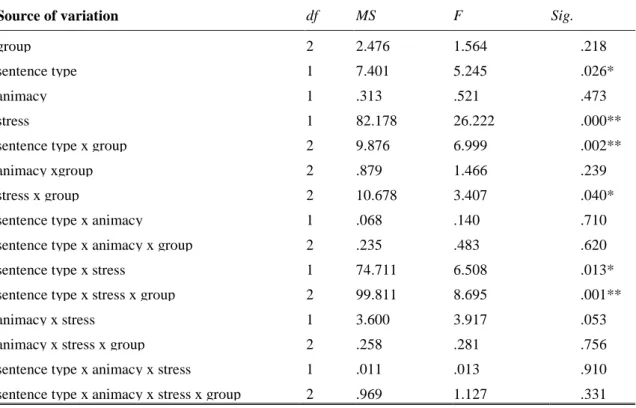

learners performed as a function of proficiency respectively in isolated sentences. ANOVAs were employed to analyze the data, particularly in L2 pragmatic developmental pattern of EFL adult learners. As indicated in Table1 below, the main effect of sentence type and stress, the two-way interaction effect of sentence type x

group, stress x group, sentence type x stress, and the three way interaction effect of group x sentence type x stress reached significance in all EFL groups. To better examine the sources of variation, the following discusses the utilization of surface cues in each of the cue configurations.

Table 1 ANOVA Results of The Given and New Interpretation Task for EFL learners

Note.*p ≦ 0.05 **p ≦ 0.01

Use of word order

Word order cue is the only available cue in English semantically-reversible actives

with normal intonation for Given and New interpretation. The percentile of the expected use of word order cue by treating post-verbal element as New indicator was 87.5 %, 76.25%, and 57.5% for LEP, HEP, and NES. The result showed that NES used word order cue for Given/ New interpretation effectively. Although both EFL learners could use word order cue, there were variations. The statistical result showed that in terms of the percentile, there was significance in the extent of reliance between LEP and NES (p ≦ 0.05), though not between HEP and NES. Despite this, due to the similarities of word order cue across the two languages, word order cue was easily acquired to identify Given/New regardless of proficiency level. However, it was noted that the higher English proficient EFL adult learners are, the lesser they would rely on

Source of variation df MS F Sig.

group 2 2.476 1.564 .218

sentence type 1 7.401 5.245 .026*

animacy 1 .313 .521 .473

stress 1 82.178 26.222 .000**

sentence type x group 2 9.876 6.999 .002**

animacy xgroup 2 .879 1.466 .239

stress x group 2 10.678 3.407 .040*

sentence type x animacy 1 .068 .140 .710

sentence type x animacy x group 2 .235 .483 .620

sentence type x stress 1 74.711 6.508 .013*

sentence type x stress x group 2 99.811 8.695 .001**

animacy x stress 1 3.600 3.917 .053

animacy x stress x group 2 .258 .281 .756

222

word order, more close to the performance of NES.

Use of marked cleft structure

In semantically-reversible cleft structure with normal stress on the first post-copular element, the percentile of the expected reliance on English cleft cue as New indicator was 37.5%, 61.25%, and 72.5% for LEP, HEP, and NES. The result indicated that NES utilized the cleft cue effectively. There was significant difference in the percentile of cleft cue use only between LEP and English native speakers ( p ≦ 0.05), but not between HEP and NES. This indicated that higher English proficient learners instead of lower English proficient learners had acquired the ability to utilize cleft cue, approximating the target norm. Compared with a study done by Chen & Chen (2006) on EFL children’s pragmatic development, there were similarities and differences between child and adult acquisition patterns in the acquisition of cleft cue to identify New. In their study, regardless of L2 proficiency level, Taiwanese EFL children were unable to utilize cleft to identify New, while in this study, Taiwanese EFL university students with higher, but not lower English proficiency level, could use cleft to identify New. This implies that the acquisition of the mapping between cleft and Given/New continues till very late.

In addition, it was found that the acquisition of form-function mapping between clefts and Given/New occurred later than that for word order, supporting MacWhinney’s (2005) claim that the acquisition of cues in a second language begins with L2 cue that are close to those for L1 in L2 sentence interpretation, and gradually changes in the direction of the native speakers’ settings for L2.

Competition between animacy and word order

The reliance on animacy could be evaluated in the condition when animacy

competed with word order in semantically reversible actives with normal stress on post-verbal element. The percentile of expected use of word order over animacy as New indicator was 68.75%, 77.55%, and 50% for LEP, HEP, and NES. Each of the EFL groups relied on word order cue more than animacy, while NES performed at chance level. Particularly, HEP group had more preference for word order than LEP and NES. The finding seems to divert from the claim made by Gass (1987) that semantic cue predominated over syntactic cue in language learning.

Competition between animacy and cleft

223

33.75%, 48.75%, and 76.25% for LEP, HEP, and NES. The statistical result showed that NES adopted cleft over animacy. In strategy selection, unlike NES, each of the EFL learners was inclined to utilize animacy cue rather than cleft cue. However, compared with LEP (with 33.75% correct response), HEP (with 48.75% correct response) could better utilize cleft structure to a greater extent for Given/New interpretation. In terms of the percentile, there was significant difference between each group of the EFL learners and NES ( p ≦ 0.05). In brief, both EFL groups haven’t acquired the mapping rule to approximate the target norm in this cue configuration.

Competition between focal accent and word order

In semantically-reversible actives with emphatic stress on post-verbal element,

focal accent competed with word order. The percentile of the expected reliance on focal accent for LEP, HEP, and NES was 18.75%, 31.25%, and 46.25%. The result showed that like NES, both EFL groups relied more on word order rather than expected focal accent cue. As statistical result indicated, there was significant difference between LEP and NES in the degree of reliance of focal accent, but not between HEP and NES. HEP utilized focal accent to a greater extent than LEP, suggesting that the higher English proficient EFL learners were, the more they relied on focal accent as New indicator, more close to the performance of NES.

Competition between focal accent and clefts

In semantically-reversible clefts with emphatic stress on the second noun, focal accent competed with cleft cue. When focal accent was in competition with cleft, the percentile of expected correct use of emphatic stress as New indicator for LEP, HEP, and NES was 72.5%, 47.5%, and 30%. The result showed that NES preferred cleft syntax to focal accent. The observation of strategy use showed that HEP relied on cleft over focal accent like native English speakers, but LEP was inclined to use focal accent cue over cleft, unlike NES. In terms of the percentile, there were significant differences between each of EFL groups and NES (p ≦ 0.05). This implied that the higher proficient EFL learners were, the lesser they relied on focal accent cue, like NES, when it completed with cleft.

Converging focal accent and word order

224

statistical result, like NES, both EFL groups effectively utilized the converging cues. In terms of the percentile for the reliance degree, no significance was found between each of EFL groups and NES. This suggested that both EFL groups have acquired the mapping rule in pragmatic comprehension in the use of two converging cues.

In comparison with the percentile in active with normal stress on post-verbal element, the percentage of the use of converging cues decreased by 15%, 1.25%, and 2.5% in LEP, HEP, and NES. The result didn’t support the convergence principle postulated by MacWhinney and Bates (1989) that the most consistent sentence interpretation strategies would be provided in the convergence of all surface linguistic cues because the converging cues didn’t yield better performance for all EFL groups, compared with the performance in the condition when word order cue was the only available cue.

Converging focal accent and clefts

In semantically-reversible clefts in which emphatic stress was placed on the post-copular element, focal accent was in convergence with cleft cue. Under the convergence condition of focal accent and cleft, the percentile of the reliance on the two converging cues for LEP, HEP, and NES was 27.5%, 56.25%, and 73.75%. Based on the statistical result, NES effectively relied on the converging cues. In terms of the percentile, HEP instead of LEP relied on the converging cues to a more similar extent like native English speakers. This suggested that as L2 learners develop their L2, they gradually performed more like their target norms.

When compared with the condition where marked cleft structure was the only available cue, the percentage of correct response for LEP and HEP decreased by 10% and 5%, but slightly increased by 1.25% in NES. This suggested that both the EFL groups didn’t improve their performance significantly in the use of the converging cues. The slightly better performance by NES partially echoed Convergence Principle as postulated in the Competition Model (MacWhinney & Bates, 1989).

Conspiracy of focal accent and animacy over word order

225

NES, both the EFL groups preferred the use of word order cue to the conspiring cues of focal accent and animacy as New indicator. Although all the EFL groups have more preference for the word order cue to the two conspiring cues in this condition, the higher proficient EFL learners were, the more they relied on the conspiring cues for Given/New, closer to the target norm.

Conspiracy of focal accent and animacy over cleft

In semantically-irreversible cleft in which emphatic stress was imposed on the second animate noun, focal accent conspired with animacy against cleft cue. Under this condition, the percentage of the use of conspiring animacy and focal accent over marked cleft structure was 77.5%, 51.25%, and 32.5% for LEP, HEP, and NES. Based on the statistical result, NES preferred the cleft structure over the conspiring focal accent and animacy. In other words, there were cross-linguistic differences that NES had more preference for the cleft cue. Unlike the performance of NES, both EFL groups relied more on the conspiring cues of focal accent and animacy than cleft syntax for Given/New interpretation. There was significant difference between each of EFL groups and NES in terms of the percentile of the use o the conspiring cues (p ≦ 0.05), indicating that EFL groups haven’t approximated the target norm in strategy selection.

226

Conclusion and pedagogical implications

The finding of this study was summarized in the following: 1. Both EFL groups effectively utilized word order cue.

2. HEP, but not LEP, have learned to use cleft structure for Given and New interpretation.

3. When animacy competed with word order, both EFL groups relied more on word order; when animacy competed with cleft marked structure, unlike NES, both EFL groups preferred animacy to cleft syntax.

4. When focal accent competed with word order, both EFL groups relied more on word order like NES, though there was significant difference in the extent of reliance between LEP and NES; when focal accent competed with cleft, HEP, but not LEP, displayed preference for cleft cue, as NES did.

5. When focal accent converged with other cues, EFL groups didn’t respond consistently.

6. When focal accent conspired with animacy over word order, both EFL groups were inclined to rely on word order; while in the condition when focal accent conspired with animacy over cleft, they responded to cleft structure nonuniformly.

There were some implications that could be drawn from the findings of

this study. First, inter-language variations in L2 pragmatic comprehension were found to be constrained by the interplay of developmental, psychological, and linguistic factors. An adequate model of L2 learning needs to be constructed across multidimensional facets instead of adopting a one-dimensional approach.

Secondly, as L2 adult learners develop their second language, L2 syntactic learning and pragmatic interpretation developed on separate path, and was not mastered at the same time. EFL teachers should be aware that the comprehension of the meaning of linguistic forms might not be sufficient to ensure understanding of the pragmatic Given/New marking in sentences. Language teaching should not limit to the teaching of sentence forms or forms in isolation. According to Bardovi-Harlig (1990), a sentence, within a passage, functions at three levels: syntactic, semantic, pragmatic. At the pragmatic level, encoding of Given and New information is one of the major functions that a sentence is used for. Recent study on discourse analysis have led to a general movement within language pedagogy, which moves from focus on grammar to concern with language teaching for communication, which involves application of pragmatic knowledge of information patterning (Celce-Murcia & Olshtain, 2000).

227

different languages varying in cue weights of information patterning, can be conducted. Second, other types of pragmatic interpretation tasks can be used, with more experimental variables manipulated, e.g., passives, adverbials, or context of different nature. Third, more studies, within the framework of the Competition Model, can be conducted to compare the similarities and differences between production & comprehension for Given/New encoding and decoding in bilingual.

References

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1990). Pragmatic word order in English composition. In V.

Connor & A.M. Johns (Eds.), Coherence in writing: Research and pedagogical perspectives (pp. 44-65). Alexandria: VA: TESOL.

Bates, E., McNew, S., MacWhinney, B., Devescovi, A., & Smith, S. (1982). Functional constraints on sentence processing: A cross-linguistic stud y. Cognition , 11, 245-299.

Bolinger, D. L. (1989). Intonation and its use. California: Standford University Press. Brown, Douglas. (2007). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. New York:

PearsonLongman.

Celce-Murcia, M., & Olshitain, E. (2000). Discourse and context in language teaching. Oxford: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, L. Y. (2008). A Study on Given and New Interpretation by Taiwanese EFL Junior High School Students. MA thesis, National Taipei University of Education.

Chao, Y.R. (1968). A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: Univeristy of California Press.

Chen, R. (1995). Communicative dynamism and word order in Mandarin Chinese. Language Sciences, 17, 201-222.

Chen, S. H. (1998). Surface cues and the development of given and new information. Applied Psycholinguistics, 19(4), 553-582.

Chen, S. H., & Chen, S. C. (2006) The development of Given and New strategy by Taiwanese EFL children: The emergence of L2 pragmatic comprehension. In the proceedings of 2006 International conference and Workshop on TEFL and Applied Linguistics. Ming-Chuan University.

Chui, Kawai. (1994). Information flow in Mandarin Chinese discourse. Ph.D. disstertation, National Taiwan Normal University.

Chui, Kawai (2005). Structuring of information flow in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 33(1), 34-67.

228

crosslinguistic study of language, Vo 1: The data. Hilldale, New Jersey. Clancy, P. M. (1992). Referential strategies in the narrative of Japanese children. Discourse Process, 15,441-467.

Cutler, A. (1997a). The comparative perspective on spoken-language processing. Speech Communication, 21(1/2), 3-16.

Culter,A. (1997b). The syllable’s role in the segmentation of stress languages. Language and Cognitive Processes, 12(5/6), 839-845.

Devescovi, A.,& D’amico, S. The competition model: Crosslinguistic studies of online processing. In: Tomasello, M.; Slobin, DI (eds.), Beyond nature-nurture. Essays in honor of Elizabeth Bates. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005, pp. 165-191

Gass, S.(1987). “The resolution of conflicts among competing systems: A bidirectional perspective.” Applied Psycholinguistics, 8, 329-350.

Gussenhoven, C. (2004). The phonology of tone and intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Halliday, M.A.K(2005). Studies in English. New York: Continuum.

Halliday, M. A. K, & Webster, J. J. (2005). Studies in English Language. New York: Continuum.

Harrinton, M. (1987). Processing transfer: Language-specific processing strategies as a source of interlanguage variation. Applied Psycholinguistics, 8, 351-377. Hernandez. A., Bates, E., & Avila, L. (1994). On-line sentence interpretation in

Spanish-English bilinguals: What does it mean to be “in- between”? Applied Psycholinguistics, 15, 417-446.

Hernandez, A., Li, P., & MacWhinney, B. (2005) The emergence of competing modules in bilingualism. Trends in Cognitive Science, 9(5), 220-225. Hickmann, M., Hendricks, H., Roland, F., Liang, J. (1996). The marking of new

information in children’s narratives: a comparison of English, French, German, and Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Child Language, 23, 591-619.

Hickmann, M., & Liang, J. (1990). Clause-structure variation in Chinese narrative discourse: a developmental analysis. Linguistics, 28, 1167-1200.

Hornby, P. A (1971). Surface structure and the topic-comment distinction: A developmental study. Child Development, 42, 1975-1988.

Kilborn, K., & Cooreman, A. (1987). Sentence interpretation strategies in adult Dutch-English bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics, 8, 415-431.

Ladd, D.R. (1996). Intonational phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lambrecht, K. (1994). Information structure and sentence form.

229

Lambricht, K. (2001). A framework for the analysis of cleft constructions. Linguistics, 39(3), 463-516.

LaPolla, R. J. (1993). Arguments against ‘Subjects’ and ‘Direct Object’ as viable Concepts in Chinese. Bulletin of the Institue of History and Philosophy, Acedmica Sinia, 63, 759-808.

LaPolla, Randy J. (1994). Pragmatic relations and word order in Chinese. In P. Downing and M. Noonan (Eds.) Word Order in Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

LaPolla, Randy J. (2009). Chinese as a Topic-Comment (Not Topic-Prominent and Not SVO) Language. In Janet Xing (Ed.), Studies of Chinese

Linguistics: Functional Approaches (pp. 9-22). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Li, C., & Thompson, S. (1976). Subject and topic: a new typology for language. In C. Li (Ed.), Subject and Topic. New York: Academic.

Li, C., & Thompson, S. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Li, P., Bates, E., & Liu, H. (1992). Cues as functional constraints on sentence processing in Chinese. In Chen, H. C., & Tzeng, O. J. L. (Ed.). Language Processing in Chinese,(207-232). Netherland: North Holland.

Li, P., Bates, E., Liu, H., & MacWhinney, B. (1993). Processing a language without inflections: A reaction time study of sentence interpretation in Chinese. Journal of Memory and Language, 32, 451-484.

Liu, H., Bates, E., & Li, P. (1992). Sentence interpretation in bilingual speakers of English and Chinese. Applied Psycholinguistics, 13, 451-484.

MacWhinney, B., Bates, E., & Kligel, R. (1984). Cue validity and sentence interpretation in English, German and Italian. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23, 127-150.

MacWhinney, B. (1987). The competition model. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.), Mechanisms of language acquisition. Hillsdale,NJ:Erlbaum.

MacWhinney, B. & Bates, E. (Ed.). (1989). The Crosslinguistic Study of Sentence Processing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacWhinney, B. (2002) The Competition Model: The input, the context, and the brain. In Robinson, P. New York: Cambridge University Press

MacWhinney, B. (2005). "A Unified Model of Language Acquisition". in Kroll,Judith; DeGroot, Annette. Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches.. Oxford: Oxford University Press

MacWhinney, B. (2005). Extending the Competition Model. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9(1). 69-84.

230

Miao, X. (1981). Word order and semantic strategies in Chinese sentence comprehension. International Journal of Psycholinguistics, 8, 23-33.

Prince, E. (1981). Toward a taxonomy of given/new information. In P. Cole (Ed.), Radical Pragmatics, (pp.223-255). New York: Academic Press.

Prince, E. (1985). Fancy syntax and ‘shared knowledge’. Journal of Pragmatics, 9, 65-81.

Shen, X.-N. (1990). The Prosody of Mandarin Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shen, X. S. (1990). Ability of learning prosody of an intonational language by speakers of a tonal language: Chinese speakers learning French prosody. IJAL, 28(2), 119-134.

Stavans, A. (2003). Bilingual as narrators: A comparison of bilingual and monolingual Hebrew and English narratives. Narrative inquiry, 13(1), 151-139.

Stephen, J.E. (1981). Differences in the F0

Su, I.R.(2001a). Transfer of sentence processing strategies : A Comparison of L2 patterns of speech: Tone language versus stress language. Journal of Accoustical Societal America, 70(1), 39-59.

learners of Chinese and English. Applied Psycholiguitics, 22, 83-112. Su, I.R. (2004). The effects of discourse processing with regard to syntactic and

semantic cues: A competition model study. Applied Psycholignusitics, 25, 587-601.

Sun, C. F. & Givon, T. (1985). On the so-called SOV word order in Mandarin Chinese: A qualified text study and its implications. Language, 61,329-351.

Teng, S. H. (2005). Functional grammar and informational structure in Chinese. In S. H. Teng (Ed.), Studies on Modern Chinese Syntax (pp. 269-274), Taipei, Taiwan: Crane Publishing Co. Ltd.

Tsao, Feng-fu (1990). Sentence and Clause Structure in Chinese: A Functional Perspective. Taipei: Student Book Co.

Wang, B. & Xu, Y. (2006) Prosodic Encoding of Topic and Focus in Mandarin. Speech Prosody,1-4.

Xu, L. (2004). Manifestation of information focus. Lingua, 114, 277–299.

Xu, Y.(1999). Effects of tone and focus on the formation and alignment of F0 contours. Journal of Phonetics, 27, 55-105.

Yekovich, F.R. Walk, C.H. & Blackman, H.S. (1979). The role of presupposed and focal information in integrating sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 535-548.