Chapter 1 Introduction

Motivation

How to teach a class of students with different academic achievements and varied abilities has always been a problem for English teachers in Taiwan. In a class numbering 30 to 40 students, some have learned English for 2 years or more before they enter junior high school, but some are just fresh starters. It is difficult for

teachers to decide the appropriate level of materials and instruction in class. Therefore, ability grouping has recently been proposed to be implemented in English teaching in Taiwan.

The earliest practice of ability grouping can be traced back to W. T. Harris’s plan, initiated in 1867 in St. Louis, U.S.A., where bright pupils were selected and rapidly promoted through the elementary grades (Goldberg, Passow, & Justman, 1966). After that, various types of ability grouping have been put into practice. Many teachers strongly favor ability grouping on the basis of the assumptions as follows: (1) students learn better when they are grouped with others of similar ability, (2) slower students develop more positive attitudes towards themselves and school by avoiding exposure to bright students, (3) students are easier to teach and manage when the range of individual differences is smaller, and (4) teachers can provide more appropriate materials and subject content to students of similar ability (French & Rothman, 1990;

Nicholson, 1998; Oakes, 1985).

Ability grouping has also been practiced at some schools in Taiwan, and it seems to become a trend. According to an investigation conducted by Taipei Bureau of Education (“Ability Grouping,” 2004), 30 elementary schools out of 142 in Taipei have implemented ability grouping in English teaching to cope with teaching and learning difficulties caused by different academi c achievements and varied abilities of students. One successful example is Taipei Lungan Elementary School, where flexible

ability grouping has been practiced for 4 years and positive effects have been attested on students, teachers, and parents (Chan & Chiang, 2002). Students are happy about the grouping system and can learn English under the unstressed circumstances. Ability grouping was also carried out successfully at Wenzao Ursuline College of Languages for the second-year English reading class (Su & Lin, 2003). Both high and low achievers agreed that ability grouping met their learning needs for reading and listening.

Although ability grouping has been practiced for more than a century, studies do not reach agreement on its effects on students of various proficiency levels. Actually, many studies showed that ability grouping did not influence student achievements significantly (French & Rothman, 1990; Goldberg et al.,1966). French and Rothman (1990), for example, pointed out that ability grouping retarded academic progress of students in low- and middle-ability groups. Besides, Burroughs and Tezer (1968) found that poor teaching methods and techniques were often used in lower-level groups. Furthermore, students in the low- and middle-ability groups developed resentment against the teacher and the subject matter, as well as a negative spirit of competition.

The debate on ability grouping goes on among teachers, parents, administrators, and educational researchers for more than half of a century, and its educational merits seem to be controversial. Therefore, it is worth to study the effects of ability grouping on English learning in Taiwan.

Background of the Study

In the school year of 2002, Sunny Junior High School1 implemented ability grouping in the 7th-grade English class. The 7th graders mainly came from the school district of Colin Elementary School and Raymond Elementary School2. They were

among the first groups of students that received the new elementary school English curriculum when they were at the 6th grade in the school year of 20013. Before they entered junior high school, each of them had at least one-year experience of formal English learning. To understand how new English curriculum implemented in elementary school, the director of students’ academic affairs, the chief of curriculum section, and the English teachers of Sunny Junior High School had a meeting with the English teachers of Colin Elementary School and Raymond Elementary School in April, 2002. Furthermore, the junior high school teachers visited and observed their English classrooms in May, 2002.

At Colin Elementary School, no ability grouping was implemented in English class. Students learned English in their original class. At Raymond Elementary School, students were divided into advanced learners, intermediate learners, and true beginners. True beginners learned the 26 alphabets and basic vocabulary; intermediate learners learned a set of textbooks, which was the same as Colin Elementary School;

advanced learners read the novel The Little Prince in English version. In both schools, English curriculum was implemented 2 class-periods a week. According to the English curriculum guidelines of the Nine-year Joint Curricula Plan in 2000 (MOE, 2004), English curriculum in elementary education mainly aims to develop the following abilities of students: (1) mastery of 26 alphabets, (2) ability to use at least

1 Sunny is the pseudonym of the junior high school investigated in the present study to respect the school’s right to privacy.

2 Colin and Raymond are the pseudonyms of the two elementary schools to respect the schools’ right to privacy.

3 The Nine-year Joint Curricula Plan became effective in September 2001. It planned to institute English instruction for all 5th graders. To respond to the call of parents of 6th graders at that time, 6th graders in the 2001 school year were also included in the participants receiving new English curriculum.

No standardized textbooks to be used nationwide were available under the new curriculum policy.

Schools freely adopted textbooks that came under review by the National Institute of Compilation and Translation. The pedagogical emphases at the stage of elementary English instruction focused on developing students’ listening and speaking abilities in English and developing students’ interests in learning English (Chern, 2003).

200 productive vocabulary and to spell at least 80 of them, (3) ability to read words by the rules of phonics, and (4) ability to carry out simple daily life conversations in English, such as greetings, expressing thanks, apology, saying goodbye, etc. Under these guidelines, the English teachers in both elementary schools used a lot of activities, including games, songs, and role-play, in classroom teaching. Few class hours were spent on grammar explanations. Assessment took the form of games and paper-and-pencil tests.

Through the communication between junior high and elementary teachers, junior high school teachers had basic understanding of the students. Figuring out that the differences between individual students were even larger than before and seeing how ability grouping worked in Raymond Elementary School, the director of students’ academic affairs, the chief of curriculum section, and the English teachers of Sunny Junior High School decided to implement ability grouping in English class in the coming school year of 2002 to deal with potential teaching difficulties.

Ability Grouping System in Sunny Junior High School Grouping Students

At the very beginning of the school year 2002, the students of nine classes were separated into either Group A (high level) or Group B (low level) based on their performance in an English placement test. Two test writers constructed the placement test by consulting a set of textbooks mainly used by the two elementary schools in the school district. The test questions included listening comprehension, 26 alphabets (capital and lower cases), vocabulary recognition, unscrambling the words, matching questions and answers, short answers (e.g., Yes, I do. / No, I don’t.), sentence completion (e.g., Do you like pizza?). See Appendix A for the placement test.

For the convenience of scheduling class hours, students of 9 classes were divided

into three large sections, namely, Classes 1, 5, and 8 formed Section 1, Classes 2, 6, and 9 formed Section 2, and Classes 3, 4, and 7 formed Section 34. Each section was further divided into 3 classes according to students’ scores on the English placement test. The 3 classes of the same section had the same English class schedules.

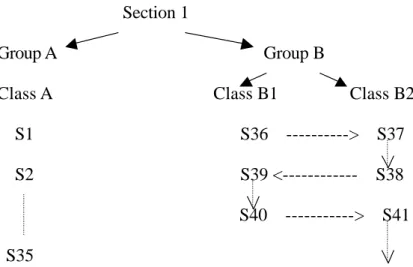

The top one-third students in each section were placed in Group A. The rest of the students in each section were evenly placed into two classes (B1 and B2) according to their performance in the placement test. For example, in Section 1, the top 35 students were placed in Group A, then the student ranked as 36th was placed in B1, the 37th student was placed in B2, the 38th in B2, the 39th in B1, and so on. Figure 1 shows how students in Section 1 were placed into three classes.

Section 1

Group A Group B

Class A Class B1 Class B2 S1 S36 ---> S37 S2 S39 <--- S38 S40 ---> S41 S35

Figure 1 Diagram of allocating students

Class B1 and Class B2 were basically equal in English abilities. By allocating students in this way, the school tried to avoid stigmatizing low-level students as bad students. In the end, there were 3 classes of Group A, 3 classes of B1, and 3 classes of B2 in total.

_____________________________________

4 The 9 homeroom classes were formed based on an S distribution of students’ scores on the IQ test they took when they enrolled junior high school so that each homeroom class was basically equal in IQ and learning abilities. In addition, the three sections were formed for the convenience of timetable arrangements. The three sections were also basically equal in IQ.

The students had English in separate language classrooms, whereas they had other regular curriculum with their original class. Students in Groups A and B used the same set of English textbooks, and took the same midterm and final examination questions. Before the second semester, the students were regrouped according to their average scores of midterm and final examinations of the first semester. Those who made good progress to the top one-third in each section transferred from Group B to Group A, and vice versa.

Teachers’ Teaching

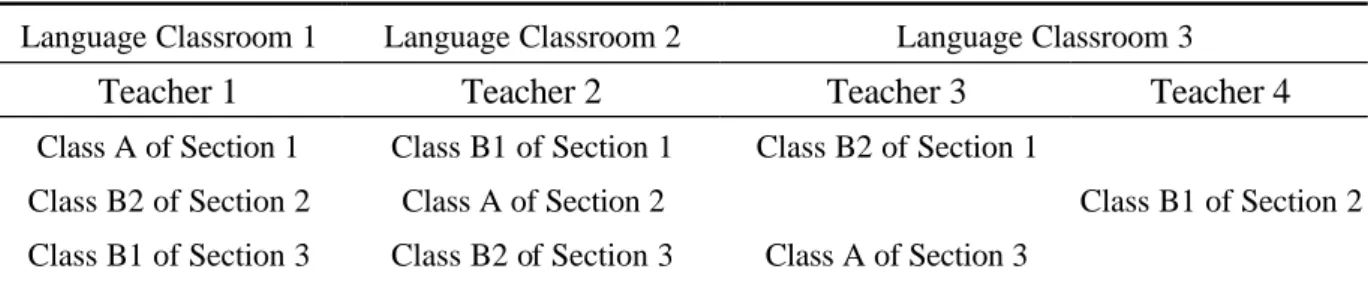

There were four teachers responsible for the 7th-grade English. To avoid being labeled as “Group A teacher” or “Group B teacher”, all English teachers agreed that neither Group A nor B should be all assigned to one particular teacher. Therefore, the school assigned different groups evenly to the four English teachers. Table 1 shows how the classes were assigned to the teachers. The classes of the same section had the same English class schedules.

Table 1 Assignment of classes to teachers

Language Classroom 1 Language Classroom 2 Language Classroom 3

Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Teacher 3 Teacher 4

Class A of Section 1 Class B2 of Section 2 Class B1 of Section 3

Class B1 of Section 1 Class A of Section 2 Class B2 of Section 3

Class B2 of Section 1

Class A of Section 3

Class B1 of Section 2

Considering that students could get into senior high based on their grades of junior high, to ensure fairness the school adopted the policy that all students used the same textbooks and took the same midterm and final examination questions. However, the teachers could design their own classroom activities, adjust the difficulty level of their instruction, and give assignments, supplementary materials, or quizzes according to the abilities of different classes.

Teachers’ Reflections in Team Meeting

Before the school year 2003 started, all English teachers and the director of students’ academic affairs had a meeting in June to discuss if ability grouping system would be continued for the 8th graders and the upcoming 7th graders. The four English teachers involved in ability grouping shared their experiences and reflections in the meeting. What follows is a translated version of the minutes.

Teacher 1: (1) Top students of Class A behaved arrogantly in class, showing little interest in curriculum.

(2) Sometimes, some students were not able to get into the classroom on time because of the delay of their previous class, and the rest of the students and I wasted time on waiting.

(3) Students often forgot to bring their textbooks or stationery, and we just had to stop and wait for them to get their things.

(4) I only taught one-third of my homeroom class. I spent little time with the other two-thirds and I barely knew them. Under this situation, it was difficult for me to be the homeroom teacher of the other two-thirds. (Teacher 2 also had the same problem.)

Teacher 2: (1) Many students of Class A were very proud of their English abilities and paid little attention to my instruction in class.

Although they were good at listening and speaking, they made a lot of mistakes in writing. However, they were still as proud as a peacock and did not concentrate in class.

(2) Many students of Class A didn’t turn in assignments I gave. They just didn’t care about their grades. That was very strange.

(3) I also had the same problem with Teacher 1. I spent little time with the other two-thirds of my homeroom students, which had influenced my management of my homeroom class.

Teacher 3: (1) There were still wide discrepancies in Class A. The top students showed little interest in textbooks, while the others in Class A still needed basic practice of sentence patterns in speaking and writing.

It was hard to fulfill the needs of both kinds of students at the same time.

(2) Preparing lesson plans was a heavy burden on me. I had to prepare

and design different lesson plans and activities for Class A and Class B. In the meantime I also needed to prepare lesson plans for the 8th graders because I was also in charge of a class of the 8th graders. That is, I had to prepare three different kinds of lesson plans at the same time, and that exhausted me.

Teacher 4: I think ability grouping is good for students. Students in Group A could learn more difficult things; they wouldn’t stay where they were, though I didn’t teach Class A. Students in Class B could practice basic things more. They were motivated by the thought that they could transfer to Group A if they worked hard. That encouraged them.

After the four teachers’ sharing of their opinions, all of the English teachers voted to decide if ability grouping would be continued. Six out of nine English teachers voted against continuing ability grouping system; one teacher voted for continuing ability grouping system; one teacher gave up voting5 and one teacher was absent from the meeting that day. Therefore, the same group of students had English under ungrouped situation when they were 8th graders. During the process of decision making, the students and parents, however, were never consulted.

Research Questions

The present study investigated the effects of ability grouping carried out in Sunny Junior High School in Taipei in 2002 on the seventh graders. In 2003 the policy was called off, and the same group of students had English in ungrouped classrooms when they were eighth graders. With this experience, this study aimed to answer the following research questions:

1. What attitudes did students keep towards English learning when they were in grouped and ungrouped classrooms respectively?

_________________________________________

5 The teacher who gave up voting was responsible for teaching resource classes where students had problems of mental deficiency. She did not teach regular classes, so she had no opinions.

2. What instructional strategies did teachers use when they dealt with grouped and ungrouped classes?

3. What difficulties did teachers encounter in the two different teaching situations?

4. What attitudes did parents keep towards ability grouping implemented in junior high English teaching and learning?

Significance of the Present Study

Previous domestic studies concerning ability grouping implemented in English class include those of elementary and college English teaching (Chiang, 2000; Chiang, 2003; Chien, 1987; Chien, Ching, & Kao, 2002; Su & Lin, 2003; Yu, 1994). However, the effects of ability grouping on junior high English teaching have seldom been investigated. Therefore, the results of this study may help clarify the effects of ability grouping on junior high school students and teachers. Based on the results, teaching implications will be offered. The study’s results may also be useful for junior high educational administrators and policy makers.

Definition of Terms Mixed-ability Grouping

Mixed-ability grouping is “intentionally mixing students of varying talents and needs in the same classroom” (ASCD, 2004). In the present study, ungrouped

classrooms are those deliberately structured classrooms with a wide range of abilities and achievement levels of students, also called homeroom classes. The 7th graders in 2002 were in ability-grouped classes only for English, but in mixed-ability classes for all the other subjects. When they were the 8th graders, they were in mixed-ability classes for all the subjects, including English.

Ability Grouping

Ability grouping is “the selection or classification of students for schools, classes, or other educational programs based on differences in ability or achievement” (ERIC, 2004). Students are assigned into separate ability categories based on standardized intelligence tests, achievement tests, or the combination of both plus teacher

judgments or other school records (Bryan & Findley, 1970; Dictionary of Education PLUS, 2004; Slavin, 1993).

According to Dictionary of Education PLUS (2004), ability grouping can be put into practice in different forms. When ability grouping is applied to all academic subjects, it is called “tracking” in the United States or “streaming” in Europe.

Alternatively, students may be ability-grouped for specific subjects, but in heterogeneous classes for other subjects.

Besides, the types of grouping arrangements can fall into two categories:

between-class and within-class (Slavin, 1987). The former one is school-level arrangements by which students are assigned to classes according to some measure of ability or performance, while the latter one attempts to reduce the heterogeneity within a larger class, each subgroup of which receives instruction at its own level and is allowed to progress at its own rate.

In the present study, ability-grouped classrooms are between-class ability grouping, where the 7th graders in 2002 were grouped only for English by an English placement test.

Homogeneous Grouping

Homogeneous grouping is “the organization or classification of students

according to specified criteria for the purpose of forming instructional groups with a high degree of similarity” (ERIC, 2004). The practical criterion for this classification

may be age, sex, social maturity, IQ, scholastic aptitude, achievement, learning style, or a combination of them (Bryan & Findley, 1970; Dictionary of Education, 2004). In the present study, the 7th graders in Sunny Junior High School in 2002 were

homogeneously grouped according to the scores on an English placement test.

Heterogeneous Grouping

Heterogeneous grouping is “a term used interchangeably with mixed-ability grouping” (ASCD, 2004). According to ERIC (2004), the related term to

heterogeneous grouping for second language instruction is multi-level classes which are composed of students with a wide range of proficiency in the language being taught. In this study, the homeroom classes are mixed-ability classrooms with students of multi-level English proficiency.