主題式教學法對台灣國小學生英語口說溝通能力之成效研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) The Effects of Theme-based Instruction on Oral Communicative Competence of EFL Young Learners in Taiwan. 立. 治 政 大 A Master Thesis. ‧ 國. 學. Presented to Department of English,. ‧. National Chengchi University. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements fro the Degree of Master of Arts. by Ya-tzu Hsiao January, 2011.

(3) Acknowledgments I would like to thank the enormous help given to me in completing this work. Firstly, I am grateful to dear Professor Ping-Huang Sheu, who always guides me patiently and highlights for me the different perspectives on English language education studies. I am sincerely thankful to dear committee members, Chi-yee Lin and Chieh-yue Yeh, for providing me with precious suggestions and valuable comments. Also, I would like to give heartfelt thankfulness to my good friends, Yen-hui, Huai-ching, Minnie, Sherry, and Jeff, for sharing great ideas with me and for. 治 政 motivating me to finish this paper enthusiastically. 大 I wish to acknowledge my dear 立 colleagues and students who always support me and inspire me in the whole process. ‧ 國. 學. Mostly, special love and thanks to my beloved family who always believe in me.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i Un. v.

(4) Table of Contents Acknowledgement……………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………..iv List of Tables..………………………………………………………………………..vii List of Figures..……………………………………………………………………...viii Chinese Abstract………………………………………………………………………ix English Abstract……………………………………………………………………….x Chapter One: Introduction………………………..……………………………………1 Background and Motivation……..……………………………………………….1 Purpose of the Study……………...………………………………………………5 Research Questions………………………………......……………………….….6 Significance of the Study………...……………………………………………….6 Definition of Important Terms……………………………………………………7 Chapter Two: Literature Review………..……………………………………………..9 The Origins of Theme-Based Instruction (TBI)………………………………….9 Theoretical Foundations..……………………………………..………………...10 Key Elements of TBI………….………………………………...………………14 The Benefits of TBI………………………………...……………………….…..17 Related Studies on TBI………………………………….……….……………...19. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. Critiques on the Previous Research……………………….……….……………22 Chapter Three: Methodology……………...…………………………………………24 Subjects…………………………………………….………………….………..24 Instruments………………………………………….…………………….…….25 English Oral Proficiency Test……………………………………………..25 English Learning Attitudes and Motivation Questionnaire………………..27 Procedure……………………………………………………………………..…29 Theme-Based Oral Instruction (TBOI) for EG………………………………....31 Instruction Procedure...……………………………………………………31 Teaching Process……...……………………...……………………………32. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Traditional Oral Instruction for CG…………….……….………………………40 Data Analysis…………………….………………….…………………………..41 Chapter Four: Results………………………….……………………………………..42 The Effects of TBOI and Traditional Oral Instruction on Learner s‟ Communicative Competence……………………………………………….42 The Comparison of the Learners‟ Attitudes and Motivation towards English Learning…………………………………………………………………….43 The Results of the Three Components of the Learning Attitudes Factor…45 iv.

(5) The Results of the Anxiety Factor…………………………………………53 The Results of Instrumental Factor………………………………………..54 Chapter Five: Discussion…………….…….……..…………………………………57 Research Question 1: What are the Effects of Theme-Based Instruction on oral Communicative Competence for EFL Elementary School Students? ........................................................................................................57 Research Question 2: Are There Any Changes in Learners‟ Attitudes and Motivation towards English Learning After the Implementation of Theme-Based Instruction? If Yes, in What Ways? …………………………60 Learning Attitudes Factor…………………………………………………..61 Anxiety Factor………………………………………………………………63 Instrumental Motivation Factor……………………………………………..63 Chapter Six: Conclusion……………………………………………………………...65 Pedagogical Implication of the Study...……………………………..…………..65 Limitation of the Study…………………………………...………….………….66 Suggestions for the Future Research……………………………….…………..67 References……………………………………………………………………………69 Appendixes…………………………………………………………………………...79 Appendix A: English Oral Proficiency Test……………..……………………...79 Appendix B: English Oral Proficiency Test Scoring Criteria……..……………81. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. Appendix C: English learning Attitudes and Motivation Questionnaire (Chinese Version)……………................................................................82 Appendix D: English learning Attitudes and Motivation Questionnaire (English Version) …………………………………………..………….84 Appendix E: The Categories of Three Factors for the 25 Questionnaire Items..86 Appendix F: Materials of the Pilot Study………………………………………88. Ch. engchi. v. i Un. v.

(6) List of Tables Table 2.1 Four Basic Types of Texts Used in Theme Units………………………….15 Table 2.2 Two Types of Transitions……….………………………………………….16 Table 2.3 The Summary of the Main Elements of the Previous Studies…..…………22 Table 3.1 The Four-theme Contents of EOPT………………………………………..26 Table 3.2 Threes Factors for the 25 Questionnaire Items……………………..……..28 Table 3.3 The Time Table and the Main Activities of Each Theme for EG….…….31 Table 3.4 The Activity and Task around the School Subject Theme.………...……..34 Table 3.5 The Activity and Task around the People Who Help Us Theme…………36 Table 3.6 The Activity and Task around the Fruit Salad Theme.……………………38. 政 治 大. Table 3.7 The Activity and Task around the Go Shopping Theme….……………….39 Table 3.8 The Time Table and the Main Activities of Each Theme for CG….…….40. 立. Table 4.1 Paired T-test on Pre- and Post- EOPT of EG and CG………………..……42. ‧ 國. 學. Table 4.2 Independent Sample T-test on Pre- and Post-EOPT of EG and CG…...…..43. ‧. Table 4.3 Paired T-test on Pre- and Post- Questionnaires of EG and CG……………44 Table 4.4 Independent Sample T-test on Pre- and Post- questionnaires of EG and CG……………………………………………………………………..…………45 Table 4.5 The Changes of EG Learners‟ Affective Component of the Learning. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. Attitudes towards English Learning between the Pre- and PostQuestionnaire……………………………….…………………………………………..46 Table 4.6 Comparison of Learners‟ Affective Components of the Learning Attitudes towards English Learning between EG and CG in the Post-Questionnaire……..47 Table 4.7 The Changes of EG Learners‟ Cognitive Components of the Learning Attitudes towards English Learning between the Pre- and Post- Questionnaire..48 Table 4.8 Comparison of Cognitive Components of the Learning Attitudes towards English Learning between EG and CG in the Post-Questionnaire………………49 Table 4.9 The Changes of EG Learners‟ Behavioral Components of the Learning Attitudes towards English Learning between the Pre- and Post- Questionnaire..50. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Table 4.10 Comparison of Behavioral Components of the Learning Attitudes towards English Learning between EG and CG in the Post-Questionnaire………………………………52. Table 4.11 The Changes of EG Learners‟ Anxiety towards English Learning between the Pre- and Post- questionnaire……………………………………...…………..53 Table 4.12 Comparison of Learners‟ Anxiety towards English Learning between EG and CG in the Post-Questionnaire…………….………………………………….54 Table 4.13 The Changes of EG Learners‟ Instrumental Motivation towards English Learning between the Pre- and Post- Questionnaire…….……………………….55 vi.

(7) Table 4.14 Comparison of Learners‟ Instrumental Motivation towards English Learning between EG and CG in the Post-Questionnaire………………………56. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i Un. v.

(8) List of Figures Figure 3.1 Flow Chart of the Research Procedure…………………………...………30 Figure 3.2 School Subject Thematic Brainstorming Web…………………….……..33 Figure 3.3 People Who Help Us Thematic Brainstorming Web…………………...36 Figure 3.4 Fruit Salad Thematic Brainstorming Web………………………..……...38 Figure 3.5 Go Shopping Thematic Brainstorming Web………..……………………39. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i Un. v.

(9) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文摘要. 論文名稱: 主題式教學法對台灣國小學生英語口說溝通能力之成效研究. 指導教授: 許炳煌. 立. 研究生: 蕭雅慈. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. 論文提要內容:. sit. y. Nat. 本研究在探討主題式教學法對台灣國小學生英語口說溝通能力之成效以及. n. al. er. io. 此教學法對學生英語學習態度與動機的影響。此研究以來自雲林縣某國小五年級. i Un. v. 二個班級學生為研究對象,這兩班級隨機指派為實驗組跟對照組。實驗組實施主. Ch. engchi. 題式口語教學法而對照組則實施傳統口語教學法,每週均上課一次。經過 12 週 的教學後,兩組皆進行英語口說能力測驗並施以英語學習態度與動機問卷。研究 結果顯示學生受過主題式教學法學習後在口說溝通能力有顯著進步,而且其英語 學習態度與動機也有正向的改變。希望本研究結果能為英語老師在教學實務上提 供助益。. ix.

(10) Abstract The present study mainly aimed at investigating the effects of theme-based oral instruction (TBOI) on elementary school students‟ oral communicative competence. Meanwhile, this paper also aimed at examining learners‟ perceptions of the use of TBOI, and the changes of learners‟ attitudes and motivation towards English learning after the implementation of TBOI. Two fifth-grade classes in a public elementary school in Yunlin County were randomly assigned to be the experimental group and the control group. The experimental group received TBOI, while the control group took the traditional oral. 治 政 instruction once a week. After the 12-week treatment, 大an English oral proficiency test 立 and an English learning attitudes and motivation questionnaire were administered to ‧ 國. 學. examine learners‟ oral communicative competence and their learning attitudes and. ‧. motivation respectively.. sit. y. Nat. The findings showed that TBOI had helped learners gain significant progress on. io. er. oral communicative competence, and that the learning attitudes and motivation. al. towards English learning had changed positively after the treatment of TBOI.. n. iv n C Hopefully, the findings of the study provide English teachers with some useful h emay ngchi U pedagogical implications.. Keywords: theme-based oral instruction, oral communicative competence. x.

(11) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION. This chapter serves as an overview of the whole study, and is divided into five sections. The first section states the background and motivation of the study concerning the problems that most English teachers encounter at elementary schools in Taiwan and introduces the possible solution, followed by a description of the purpose of this study. The third section presents the research questions. The significance of the study is presented in the fourth section. The definitions of. 治 政 important terms are listed in the final section. 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. Background and Motivation. ‧. In the past two decades, the English education, especially for young learners,. sit. y. Nat. has been varied widely across the world from Europe to South America, from China. io. er. to India. Trim (1997) claimed in the Council of Europe Press that the importance of. al. English language education in primary schools has grown rapidly due to the global. n. iv n C communication and technologyh revolution. Nowadays, e n g c h i U the English language serves as one of the critical modern foreign languages in Europe. In many South American countries like Colombia and Uruguay, English has been considered a required subject for most local primary schools curriculum (Cadavid, 2003; Fleurquin, 2003). With the trend of globalization, Krashen (2003) and Graddol (2006) foresee and further predict that the English language will be a world language, not merely a foreign language anymore. To keep an advantageous position in the competitive global economic arena, both official and private sectors of most Asian countries are devoted to the promotion and implementation of English language teaching and learning for young learners. 1.

(12) 2. Since the English language has been serving as the world‟s lingua franca for many decades and the importance of English proficiency has increased, acquiring communicative competence in English has become one of the crucial factors to be successful in international business, politics, academy or science (Krashen, 2003). Aware of the importance of English competence and in respond to the challenge of globalization, the English education policy has been modified and English education has been implemented from the primary level in The Nine-year Curriculum Educational Reform since the year 2002. Moreover, the Taiwan government also. 政 治 大. placed a high priority on English education in the Challenge 2008 National. 立. Development Plan (the Ministry of Education, 2002).. ‧ 國. 學. In the process of conducting the new English education policy, however, most elementary English teachers encountered three major problems. The first and most. ‧. frequently discussed problem was that the majority of parents were not satisfied with. y. Nat. io. sit. the schedule of the new English education. It is generally believed among most. n. al. er. parents that the earlier learners start learning English the better they will do in the. Ch. i Un. v. future, and as a result, they sent their children to private English learning institutions. engchi. (Crawford, 2001). Apparently the term English fever1 coined by Krashen (2003) also revealed that most Taiwanese parents have placed too much emphasis on their children‟s English learning and their over-expectations on their children‟s English test scores also gradually increased children‟s high learning stress and lowered their learning interest. Nevertheless, what parents was concern should be on how English is taught and what English competence should be acquired instead of merely focusing on when their children should start to learn English as well as on how. 1. Selected papers from the Twelfth International Symposium on English Teaching 2003 in Taipei, Krashen (2003) defined the term, English fever, “the overwhelming desire to (1) acquire English, (2) ensure that one‟s children acquire English, as a second or foreign language” (p. 100)..

(13) 3. many scores they should get (Lee, 2007). The second major problem widely mentioned was that many elementary English teachers were frustrated with the difficulty they had with children‟s low motivation and interest in learning English, though the Ministry of Education MOE has announced that arousing interest in English learning was one of the three main objectives in introducing the new English language policy for elementary level. According to the MOE (2009), the problem in the twin-peak distribution of students' English scores has been found at the primary level, which caused many lower. 政 治 大. achievers to give up learning English from very young age. Meanwhile, some recent. 立. studies pointed out that the fifth and sixth graders also gradually lost enthusiasm for. ‧ 國. 學. attending school‟s English classes due to the lack of learning challenge, less. ‧. relevance to their life experiences and the authentic environment (Chen, 2004; Crawford, 2001).. y. Nat. er. io. sit. The third problem was that most students failed to acquire adequate oral communicative competence at elementary level (Chang, 2006). Although MOE‟s. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. first major objective of elementary English language education was to develop. engchi. learners‟ aural and oral skills, both parents and school officials still paid high attention on learners‟ test scores instead of focusing on the whole learning process of learners‟ acquiring oral communicative competence (Crawford, 2001; Lee, 2007). In addition, the large class setting and short lessons (40 minutes per lesson) in public elementary schools forced students to work exclusively as a whole class with limited opportunity to provide them with organized tasks, which would allow students to learn English efficiently, cooperatively, and actively (Bowler & Parminter, 2002). In order to overcome those problems, the adoption of appropriate and effective teaching approaches was inevitable..

(14) 4. Since 1990s, the content and language integrated leaning (CLIL) approach has been widely adopted in Europe and has been gradually applied to foreign language classes in some Asian countries recently, like Hong Kong, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan due to its positive impact on improving learners‟ various facets of language learning, as well as positive attitudes towards learning English (Chung, 2004; Juez, 2006; Kiziltan & Ersanli, 2007; Lasagabaster, 2008; Osman, Ahmad & Jusoff, 2009; Seo, 1998; Yang, 2009). Research findings have shown that learners benefited greatly from participating in the CLIL approach, and the reported improvements are to. 政 治 大. help prepare learners for internationalization, to boost motivation to learn foreign. 立. language, to enhance learning skills and to elicit high levels of communications. ‧ 國. 學. (Coyle, 2008; Lasagabaster, 2008; Marsh, 2008; Marsh, Mehisto & Frigols, 2008;. ‧. Tuula, 2007). According to European Commission (2005), the definition of CLIL is that “Within CLIL, language is used as a medium for learning content, and the content. y. Nat. er. io. sit. is used in turn as a resource for language learning” (p. 4). Based on Brinton, Snow, and Wesche‟s (1989) identification, three major models of CLIL have been developed. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. for different instructional contexts: sheltered, adjunct and theme-based. Among them,. engchi. the first two driven by content usually occurs in first language (L1) contexts for helping English as a second language (ESL) university students, while the last driven by language is usually found in English as a foreign language (EFL) contexts (Brinton, Snow & Wesche, 1989; Davies, 2003). Particularly, theme-based instruction (TBI) had been applied to foreign language classes at primary level in some EFL countries for its flexible implementation, such as Hong Kong, Korea, and Turkish (Kiziltan & Ersanli, 2007, Seo, 1998; Yang, 2009). Given the fact that the focuses of the English instruction in Taiwanese primary schools are mainly on training learners‟ oral ability, arousing learners‟ motivation and interest in learning English, developing learning.

(15) 5. skills, and cultivating learners‟ intercultural awareness, TBI seems to be an appropriate approach to the EFL context in Taiwan. Though TBI have caught more and more attention in various English language teaching programs, most previous studies on TBI were conducted to ESL/EFL students at higher level, i.e. junior high school or above in most countries (Chung, 2004; Douglas, 1996; Juez, 2006; Lasagabaster, 2008; Osman, Ahmad & Jusoff, 2009; Wu, 1996). There are only some studies focusing on EFL elementary level and even fewer or no relevant studies in Taiwanese elementary school setting. Whether TBI. 政 治 大. could contribute to a successful learning outcome in Taiwan EFL elementary context,. 立. it was needed and worthwhile for the researcher to conduct the present study.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Purpose of the Study. As mentioned in the previous section, the objectives of the ten-year. y. Nat. er. io. sit. implementation of English education program at elementary level were not fully accomplished. Seeking any possible and effective solutions is needed. After. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. investigating the English fever in Taiwan, Krashen (2003) suggested that “we acquire. engchi. language when we receive comprehensible input in a low anxiety situation” (p. 102), which pointed out two essential elements of successful language learning, meaningful learning and low affective filters. In addition, Lee (2007), serving as a teacher educator, claimed that providing children with plentiful input and guiding them through a spiral learning method in the meaningful context are essential to children‟s English learning. In order to offer a possible solution for the current teaching and learning situation in elementary schools, this study mainly focused on two purposes. First, this research aimed to examine whether TBI could facilitate learners‟ oral communicative.

(16) 6. competence in Taiwan EFL primary school setting. Second, this study attempted to explore whether TBI could arouse learners‟ interests and motivation towards English learning.. Research Questions Based on the aforementioned motivation and purpose, there is a necessity to study the effects of TBI on elementary school students‟ oral communicative competence. As Enright and McCloskey (1988) suggested, TBI was one of the most. 政 治 大. effective ways to assist English language learners at various levels of education.. 立. Hence, this paper applied TBI as the syllabus guidelines to foster learners‟ oral. ‧ 國. 學. communicative competence. Meanwhile, the researcher also aimed at examining. ‧. learners‟ perceptions of the use of theme-based instruction, and the changes of learners‟ attitudes and motivation toward English learning after the implementation. y. Nat. er. io. sit. of TBI. The study asked the following two primary questions.. 1. Does the theme-based instruction have positive effects on EFL elementary. n. al. Ch. students‟ oral communicative competence?. engchi. i Un. v. 2. Are there any changes in learners‟ attitudes and motivation towards English learning after the implementation of theme-based instruction? If yes, in what ways?. Significance of the Study This study was constructed to explore the effects of TBI on elementary learners‟ oral communicative competence and the influence on their learning attitudes and motivation. The results of the research provided the following contributions to English language learning. First, from the perspectives of the.

(17) 7. pedagogical implementation, TBI has helped learners improve their oral communicative competence in the elementary school setting. This finding may provide English teachers with a useful teaching model for developing learners‟ oral communicative competence in the mixed-level setting. Second, TBI can arouse young learners‟ motivation and can meet their needs for and interests in learning foreign languages. This result may give elementary English teachers some insights into adopting TBI to enhance learners‟ learning motivation and interests. Third, concerning the course book design, the results may offer textbook publishers a new. 政 治 大. vision on innovative and creative course design.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Definition of Important Terms. ‧. To help readers clarify the focus and gain better understanding of the study, important terms are defined as follows:. y. Nat. er. io. sit. 1. Oral communicative competence (OCC). According to Dell Hymes (1972; as cited in Brown, 2000), the term. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. communicative competence can be defined as “that aspect of our competence that. engchi. enables us to convey and interpret messages and to negotiate meanings interpersonally within specific contexts” (p. 246). In other words, communicative competence was relatively a dynamic and interpersonal communication (Savignon, 1983). Communicative competence can be divided into four major components: grammatical competence, discourse competence, sociolinguistic competence, and strategic competence (Canale & Swain, 1980).. 2. Theme-based Instruction (TBI) Being the most common adopted model of the content-based instruction (CBI),.

(18) 8. theme-based instruction refers to the teaching method in which the course is organized around a certain theme or topic (Brinton, Snow, & Wesche, 1989). In a theme-based course, the theme or topic serves as a connecting thread which makes a variety of activities integrated around meaningful content (Cameron, 2008). TBI in the present study is defined as a course in which learners work with a theme that is ripe with ample potential for discussion. Then, various oral activities revolving around the theme and the language focus were implemented in the course.. 政 治 大. 3. Theme-based Oral Instruction (TBOI). 立. In the theme-based classroom, Wachs (1996) claimed that learners tend to get. ‧ 國. 學. involved in the discussion of the theme or topic. Students focus on the meaning and. ‧. the issues related to their real life instead of sentence structures, vocabulary or tenses learning. Different from the traditional oral lesson with little cohesiveness,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. theme-based oral instruction puts emphasis on learners‟ prior knowledge, individual interests and living experiences leading them to discuss in meaningful ways.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(19) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW. This study explored the effectiveness of theme-based instruction (TBI) as a teaching method of developing elementary students‟ oral communicative competence. Firstly, this chapter introduced the origins of TBI and its theoretical foundation. Then, the key elements and benefits of TBI on children‟s language learning were illustrated. Next, related previous studies were discussed.. 治 政 大 (TBI) The Origins of Theme-Based Instruction 立 Theme-based instruction (TBI) is one of the three main approaches under the ‧ 國. 學. broader model of the content and language integrated leaning (CLIL) / the. ‧. content-based instruction (CBI), which emphasizes the integration of content. sit. y. Nat. learning with language teaching aims by creating a highly contextualized language. io. er. learning environment (Wesche & Skehan, 2002). These three models are sheltered,. al. adjunct and theme-based instructions. Sheltered instruction was applied to content. n. iv n C courses designed for the ESL learners taught by a content area specialist h e nand gchi U. (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). In the adjunct instruction model, learners are enrolled in the linked content and language courses, in which students have to complement the coordinated assignments (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). Theme-based instruction refers to “a language course in which the syllabus is organized around themes or topics...language analysis and practice evolves out of the topics that form the framework for the course” (Richards & Rodgers, 2001, p. 216). Different from sheltered and adjunct models applied in ESL immersion programs, TBI usually occurs in EFL contexts, for the lack of complex implementation. In TBI, themes are the central ideas that construct the language courses, and the language teacher, not 9.

(20) 10. the subject specialist, takes responsibility for teaching content. Besides, TBI is organized around theme or topic rather than a subject, which meet the different needs of various EFL contexts (Kiziltan & Ersanli, 2007). By definition, TBI is a language course which is constructed around themes or topics, with the linguistic forms integrated in the syllabus (Brinton, Snow & Wesche, 1989). Different from traditional language instruction, the selected themes or topics provide the content from which teachers extract language learning activities (Osman, Ahmad & Jusoff, 2009). While general language courses may also involve a variety. 政 治 大. of themes, the content acts individually as a meaningful context focusing on the. 立. language skills being taught. Brinton, Snow and Wesche (1989) pointed out that, “in. ‧ 國. 學. a theme-based course, in contrast, the content is exploited and its use is maximized. ‧. for the teaching of skill areas” (p. 26). Additionally, TBI provided learners with coherence and continuity across different subject areas and offered training on. y. Nat. er. io. sit. higher-level language skills (Brinton, Snow & Wesche, 1989). The notion of TBI is to integrate a variety of activities generating from the meaningful content and to. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. avoid offering learners fragment knowledge and unconnected exercises (Berry & Mindes, 1993).. engchi. Theoretical Foundations TBI is based on five major theories of language learning: scaffolding theory (Buner, 1983), the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD; Vygotsky, 1978), comprehensible input theory (Krashen, 1984), comprehensible output hypothesis (Swain, 1995) and schema theory (Anderson, 1977; Bartlett, 1932; Piaget & Inhelder, 1969). First, from the perspectives of cognitive psychology, Bruner (1983) introduced.

(21) 11. scaffolding as a useful framework provided by adults to support children, which can help them to complete more difficult tasks beyond their independent efforts. The scaffolding theory in TBI involves linguistic, cognitive and affective aspects. In terms of linguistic scaffolding, as language teachers set target language learning points for a new lesson, children have been struggling with using the needed language forms to solve the tasks or problems. With providing systematic language learning, what Bruner refers to as formats, the language teacher implemented constrained and familiar activities in order to equip children with essential language. 政 治 大. patterns though they are not familiar with those language points at the beginning.. 立. The linguistic aspect is characterized during the process in which children gradually. ‧ 國. 學. borrowed language forms or patterns needed. This scaffolding made the language. ‧. teacher act as instructor, helping and supporting children till the moment children can automatically participate in real communication without the assistance of the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. adults. Further, both cognitive and affective scaffolding can be integrated in small group activities, games or tasks which require cooperation, discussion, and. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. imagination. In TBI, learners are assisted by skillful teachers or more capable peers. engchi. in their development. Wu (2007) indicated that one of recommended strategies for the implementation of TBI is cooperative learning which allows learners to learn from other capable learners. Since the more students know about the language, the more easily they can learn content and assist others with the content and language. Second, by moving forward to one‟s ultimate learning situation, this scaffolding notion chimed with Vygotsky‟s (1978) ZPD theory. In terms of second language acquisition (SLA), ZPD theory is one of the important concepts in the social constructivist model. Different from other schools of SLA, Vygotsky observed children‟s language learning under the social context instead of individual learning..

(22) 12. Vygotsky (1978) defined ZPD theory as: The distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers. (p.86) TBI can provide learners with ample communicative stretching for language learning. Motivated by high interest in a theme or topic, children may be eager to work out the meaning of unfamiliar language. With the support of meaningful content, children may struggle to communicate to others with limited knowledge.. 政 治 大. These precious moments when children are stretched to their limit may pushes them. 立. into the ZPD (Cameron, 2008).. ‧ 國. 學. Third, among Krashen‟s (1982) theories of second language acquisition, the. ‧. input hypothesis is the most important one. The input hypothesis put emphasis on comprehensible input which can help learners acquire a second language (Zheng,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. 2008). For Krashen (1982), an essential “condition for language acquisition to occur is that the acquirer understands input language that contains structure a bit beyond. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. his or her current level of competence” (p. 100). In other words, the suitable. engchi. language level for learners should not be too much far beyond learners‟ current competence. That is to say, learners can acquire most of it but they may feel challenged to make progress (Brown, 2000). In TBI classrooms, children are interested in the content or have understood some parts of the content which is presented in new or a slight difficult linguistic structure. They use the target language as a medium of communication rather than an object of analysis. As for comprehensible input, Krashen claimed that to learn a second language effectively, acquisition should be emphasized on meaning rather than form. For an English teaching class, it is essential to occupy class time with acquisition tasks or activities.

(23) 13. rather than to focus on linguistic forms or drills practicing (Zheng, 2008). In the implication of TBI, the teacher provided comprehensible input based on learners‟ interests and needs, Fourth, in a view of Swain‟s comprehensible output hypothesis (1985), the development of learners‟ communicative competence not only relies on comprehensible input, but it also needs to provide learners with ample opportunities to use the target language productively. Moreover, De Bot (1996) also claimed that output plays a crucial role in second language acquisition “because it generates highly. 政 治 大. specific input that the cognitive system needs to build up a coherent set of. 立. knowledge” (p.529). Based on Swain‟s (1985) definition, comprehensible output. ‧ 國. 學. means “a message conveyed precisely, appropriately and coherently” (p. 249). In the. ‧. TBI classroom, thematic learning activities can provide learners with opportunities to negotiate meaning and to trigger coherent output since they focus on learners‟ living. y. Nat. er. io. sit. experiences, background knowledge and contextual language forms. Finally, according to schema theory (Anderson, 1977; Bartlett, 1932; Piaget,. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. 1969), all human beings can utilize schema, the categorical rules or scripts, to. engchi. interpret or to predict situation occurring in the environment. Corresponding to instructional strategies, the most effective implication of schema theory is the prior knowledge in processing information (Armbruster, 1996). To help learners to process information effectively, the teacher needs to focus on learners‟ existing schema and to help them make connections to the new content. In the learning process of TBI, learners‟ background knowledge acquired through their mother tongue is quite influential to assist them in linking what they have known with the new topics, and to help children learn the foreign language confidently (Seo, 1998). In conclusion, through the implication of scaffolding and ZPD theories,.

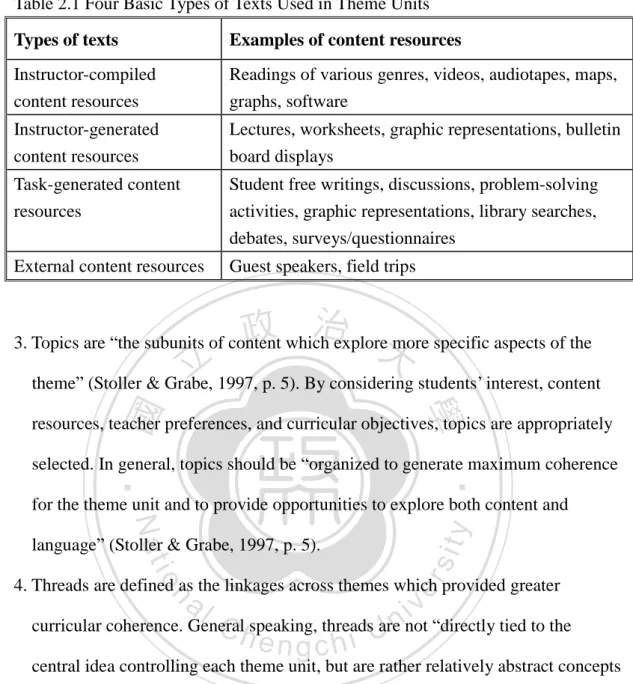

(24) 14. learners can receive supports from their teachers and peers, and can be beneficial from the interaction. Having related to comprehensible input and schema theories, the meaningful learning in TBI can create an environment where learners can comprehend the instructional input and construct framework of knowledge. As Long (1996) mentioned, interaction and meaningful input are the two essential and important features in learning languages successfully. Theoretically, TBI equipped with these two essences, interaction and meaningful input, serves as a successful approach to language teaching and learning.. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. Key Elements of TBI. ‧. Regarding key elements of TBI, Stoller and Grabe (1997) outlined the Six T‟s Approach (pp.5-7) as a systematic framework for organizing the content resources. y. Nat. er. io. sit. and selecting appropriate activities for broadly interpreting TBI as follows: 1. Themes are the main ideas that construct essential course units. They are selected. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. considering the appropriateness to students‟ “needs and interests, institutional. engchi. expectations, program resources, and teacher abilities and interests” (Stoller & Grabe, 1997, p. 5). 2. Texts are content resources including both written and aural materials which determined the basic design of theme units. Text selection followed some decisive criteria, such as students‟ interests, learners‟ language proficiency, format styles, coherence and relevance to other materials and so on. Stoller and Grabe (1997) defined four basic types of texts (as specified in Table 2.1) for using in theme units..

(25) 15. Table 2.1 Four Basic Types of Texts Used in Theme Units Types of texts. Examples of content resources. Instructor-compiled content resources. Readings of various genres, videos, audiotapes, maps, graphs, software. Instructor-generated content resources. Lectures, worksheets, graphic representations, bulletin board displays. Task-generated content resources. Student free writings, discussions, problem-solving activities, graphic representations, library searches, debates, surveys/questionnaires. External content resources. Guest speakers, field trips. 政 治 大. 3. Topics are “the subunits of content which explore more specific aspects of the. 立. theme” (Stoller & Grabe, 1997, p. 5). By considering students‟ interest, content. ‧ 國. 學. resources, teacher preferences, and curricular objectives, topics are appropriately. ‧. selected. In general, topics should be “organized to generate maximum coherence for the theme unit and to provide opportunities to explore both content and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. language” (Stoller & Grabe, 1997, p. 5).. 4. Threads are defined as the linkages across themes which provided greater. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. curricular coherence. General speaking, threads are not “directly tied to the. engchi. central idea controlling each theme unit, but are rather relatively abstract concepts that provide natural means for linking themes” (Stoller & Grabe, 1997, p. 6). In particular, the function of thread is to review and to recycle essential content and language focus across themes, and to reinforce selected learning strategies. Further, threads can connect themes that appear quite different on the surface in order to foster a cohesive syllabus. Various thematically different contents can be linked through some threads, which provided opportunities to integrate language knowledge and content aspects from new perspectives. 5. Tasks are the day-to-day basic units in which instructional activities and.

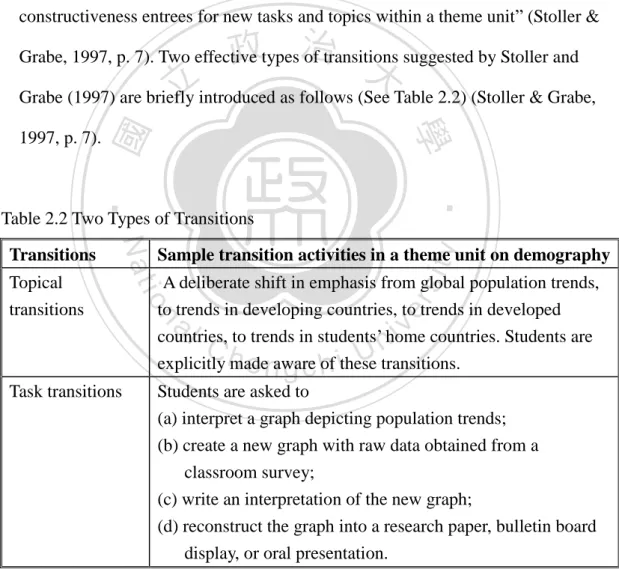

(26) 16. techniques are utilized to teach content, language, and strategy in language classrooms, such as note-taking, extracting main idea and information from the texts, problem solving, and critical thinking. In the Six-T‟s Approach, “tasks are planned in response to the texts being used. That is, content resources drive task, decisions and planning” (Stoller & Grabe, 1997, p. 6). 6. Transitions are “explicitly planned actions which provide coherence across tasks within the topics. Transitions create links across topics and provide constructiveness entrees for new tasks and topics within a theme unit” (Stoller &. 政 治 大. Grabe, 1997, p. 7). Two effective types of transitions suggested by Stoller and. 立. Grabe (1997) are briefly introduced as follows (See Table 2.2) (Stoller & Grabe,. ‧ 國. 學. 1997, p. 7).. ‧. Table 2.2 Two Types of Transitions. y. sit. al. er. A deliberate shift in emphasis from global population trends, to trends in developing countries, to trends in developed countries, to trends in students‟ home countries. Students are explicitly made aware of these transitions.. n. Task transitions. Sample transition activities in a theme unit on demography. io. Topical transitions. Nat. Transitions. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Students are asked to (a) interpret a graph depicting population trends; (b) create a new graph with raw data obtained from a classroom survey; (c) write an interpretation of the new graph; (d) reconstruct the graph into a research paper, bulletin board display, or oral presentation.. Unlike other communicative approaches (e.g. structural or task-based approaches) aiming at language teaching, the Six T‟s Approach framework makes learners more interested in and motivated toward learning English by providing.

(27) 17. them with unique concepts and effective techniques for developing a coherent theme-based instruction in the whole process of learning language.. The Benefits of TBI The potential of TBI to provide realistic and motivating uses of the language has high connection to the features of children‟s language learning, i.e. meaningful learning, learner-centered and cooperative learning. Basically, there are five essential benefits of TBI on children‟s language learning listed as follows (Enright &. 政 治 大. McCloskey, 1988; Mumford, 2000; Peregoy & Boyle, 1997):. 立. 1. Creating a meaningful conceptual framework: Brown (2001) indicated that. ‧ 國. 學. “whenever a new topic or concept is introduced, attempt to anchor it in students‟. ‧. existing knowledge and background so that it gets associated with something they already know” (p. 57). Peregoy and Boyle (1997) pointed out that TBI creates a. y. Nat. er. io. sit. meaningful conceptual framework for content learning and effective language acquiring. To make learning meaningful, students are engaged in authentic tasks. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. or activities, which are connected to their real life experiences. The teachers also. engchi. provide learners with authentic themes which revolve around learners‟ background experiences from home, previous instruction, and prior knowledge. 2. Meeting learners‟ needs and interests: As Freeman and Freeman (2006) suggested that learners will try harder to understand and to maintain focusing on the lesson if the content is relevant and interesting. In the process of organizing theme-based teaching, children can be involved in the discussion of topics selection, and their needs and interests are the key criteria for the course design. Children will learn and are willing to talk when the content is interesting to them and is related to their experiences (Seefeldt & Galper, 1998). Mumford (2000) suggested that “by.

(28) 18. building on learners‟ interests and life experiences, young people‟s attitudes, skills, and knowledge are developed in meaningful ways” (p. 4). According to Krashen‟s (1982) Affective Filter Hypothesis, TBI can provide children with a low anxiety learning environment since children‟s interests, need and attitudes have been taken into consideration as the top priority. 3. Providing learner-centered activities: Children differ from adults as language learners. Children are willing to listen to or speak of something that interests them for their own reasons, not merely because a teacher has asked them to. TBI. 政 治 大. provides child-centered activities and real communication for children to. 立. complete tasks through discussion or negotiation within a group. When they are. ‧ 國. 學. working on a given task in groups, they need to communicate for meanings and. ‧. negotiate for an agreement on solutions. This requires them to work as a group and take responsibility for their language. As Mumford (2000) claimed that. y. Nat. er. io. sit. “inquiry and real communication are activated by a desire to know more, resulting in enthusiastic participation in the learning process” (p.4), theme-based. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. instruction plays as a vehicle eliciting learners‟ desire.. engchi. 4. Developing cooperative learning: According to Slavin (1995) and Duenas (2004), significant progress in students‟ learning occurred when students worked in groups to reach solutions to the tasks. In additional, Peregoy and Boyle (1997) also suggested that small group motivated students to work collaboratively. As Dupuy (2000) pointed out, small group work can provide learners with ample opportunities in a low-risk environment for cultivating various abilities, such as how to do the peer editing, how to interact with others, how to share ideas, and how to construct knowledge. When the English teacher implemented a theme-based instruction, cooperative learning is one of the recommended strategies (Osman, Ahmad &.

(29) 19. Jusoff, 2009), which allows learners to get involved in the learning group, to learn from the capable peers, to share personal experiences with peers, and to perform different tasks or to acquire knowledge together. 5. Providing a language-rich classroom environment: TBI provided much more natural realistic contexts for nonnative speakers to use the target language (Peregoy & Boyle, 1997), and to foster language learning through communicative stretching (Cameron, 2008). Based on Vygotsky (1978)‟s ZPD, with the help of teachers or skilled peers, children can do and understand much more than they can. 政 治 大. on their own. TBI can “produce moments when pupils‟ language resources are. 立. stretched to their limit” (Cameron, 2008, p. 192). Supported by meaningful. ‧ 國. 學. content, children may be able to work out the meaning of new or unfamiliar. ‧. language, or motivated by interesting topics; they may be eager to communicate their knowledge to someone else.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. In conclusion, TBI allows children to learn in a way which is natural and authentic to them. That is, teachers can create a good deal of language course built. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. on children‟s interests and prior knowledge, and can provide an environment that. engchi. helps children link language learning and content knowledge to their real-life experiences.. Related Studies on TBI TBI, one of the CLIL models, has attracted much attention in the field of foreign language teaching and learning because it was seen as an appropriate curriculum design that can lead to positive gains in acquiring a second language in the English speaking countries. A number of school programs and studies showed that TBI was beneficial in the ESL/EFL context (Richards & Rodgers, 2001; Stoller,.

(30) 20. 2004; Wesche & Skehan, 2002). In this section, some previous studies focusing on TBI are discussed first; then, the limitations and suggestions of the related studies are illustrated. Osman, Ahmad and Jusoff (2009) conducted a study exploring the effectiveness of TBI as a means of honing the writing skills and the motivation for writing of 36 pre-degree ESL learners in a Malaysian tertiary institution. The finding indicated the implementation of TBI and cooperative process writing did to some extent improve the learners‟ motivation and proficiency in the language, mainly their writing skills.. 政 治 大. Douglas (1996) utilized a theme-based approach to design a curriculum to. 立. teach an advanced course of Japanese as a foreign language in an American. ‧ 國. 學. University. This study aimed at developing four skills. Formative and summative. ‧. evaluation of the program was conducted in order to examine the effectiveness of this approach. At the end of the final term, students filled out the questionnaire to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. evaluate the program as a whole. The results indicated that the students valued the theme-based approach, and appreciated participating in the instruction.. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. One successful program involving a TBI in Spain was documented by Juez. engchi. (2006). In Juez‟s research, the course instructed legal English, the content of Anglo-American legal system, and the use of audiovisual resources to connect the classroom to the real world. Surveys administered at the end of the course revealed highly positive feedback on perceived progress in both language and content. Kiziltan and Ersanli (2007) conducted a study of a theme-based course on Turkish young learners. Achievement tests were used at the end of the study, and the results showed that the TBI group performed better than the control group. Yang (2009) utilized theme-based teaching in an English course for primary ESL students in Hong Kong. However, the study was conducted in a non-school.

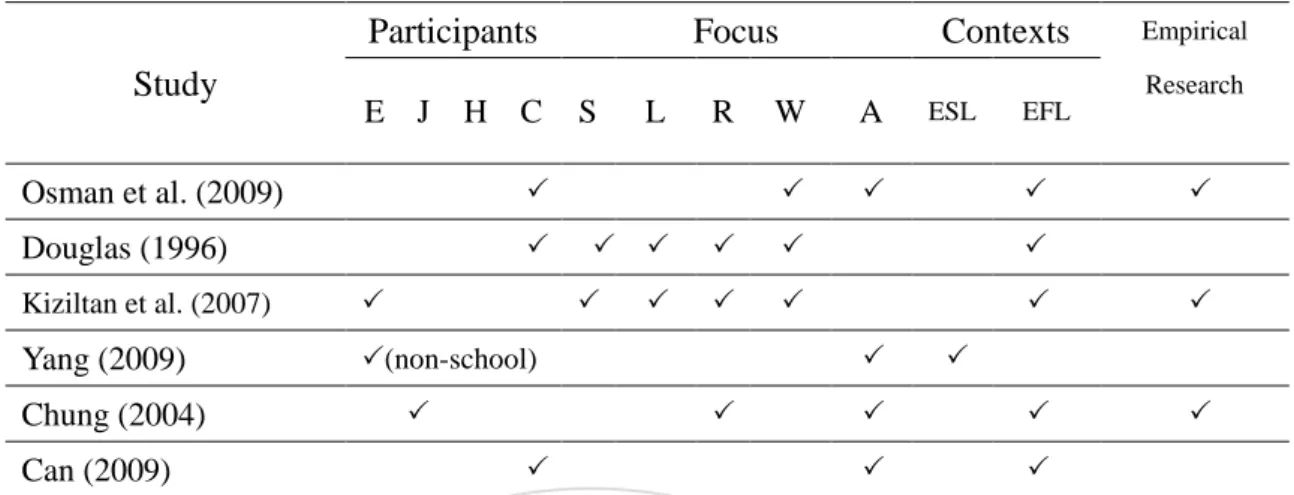

(31) 21. setting with 76 grade 4 and 5 children, and 12 course tutors were involved. Based on the collected data through questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, the finding indicated that theme-based teaching did not seem to arouse learners‟ interests in learning English at all since teachers failed to provide learners with interesting activities and suitable materials. It‟s obvious that more information concerning learners‟ interests and learners‟ English proficiency level should be collected before the course begins (i.e. a placement test and a survey on learners‟ interests could be administered in advance).. 政 治 大. Chung (2004) conducted a study to investigate the effects of the theme-based. 立. projects on English learning by comparing a computer-mediated communication. ‧ 國. 學. (CMC) group and a Non-CMC group in a junior high school in Taiwan. The study. ‧. findings reveal that CMC group did have great effects on improving learners‟ English reading proficiency, and most of the students in the group also showed. y. Nat. er. io. sit. positive responses to the theme-based project English learning, expressing that theme-based projects were interesting and they would like to further explore the. n. al. themes.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Can (2009) implemented a study to investigate the effects of theme-based syllabus on the motivation of freshman students in Turkey. The results showed that students‟ motivation improves after employing a theme-based syllabus which reflects students‟ interests in a classroom. The finding also revealed that theme-based syllabus can help learners develop positive attitude towards the course and language learning. The main elements of the previous studies were summarized in Table 2.3 as follows..

(32) 22. Table 2.3 The Summary of the Main Elements of the Previous Studies Participants Study. Focus. Contexts. Empirical Research. E J. H C. Osman et al. (2009). . Douglas (1996). . Kiziltan et al. (2007). . Yang (2009). (non-school). S. . . Chung (2004). L. R. W. A. . . EFL. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Can (2009). ESL. . Note. E= elementary school; J= junior high school H= senior high school; C= college; S=. 政 治 大. speaking; L= listening; R= reading; W= writing; A= attitudes. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Critiques on the Previous Research. ‧. Based on the discussions above and the main elements of the previous studies. io. al. er. account for the present study as follows.. sit. y. Nat. (Table 2.3), the limitations and suggestions of the previous studies are taken into. To begin with, most of the previous studies on TBI were conducted to higher. n. iv n C levels, especially to college students. h e nComparatively g c h i U fewer studies focused on. elementary school students. Yang‟s (2009) study was conducted to primary level; however, it was implemented in non-school setting in the ESL context. Although Kiziltan and Ersanli‟s (2007) study was on Turkish young learners in the EFL context, the teaching and learning situations were different from those of Taiwan. Doye and Hurrell (1997) pointed out the fact that the implementation of the English language education at primary level differs from one country to the others due to the differences in social, economic and educational conditions. In addition, though Chung‟s (2004) study was conducted to EFL setting in Taiwan, it focused on junior high school level and stressed on learner‟s reading.

(33) 23. proficiency through the aid of Computer-Mediated Communications instead of oral proficiency. Last, most of the previous studies are not empirical studies. For example, in Douglas‟s (1996) study, student responses were used as the criteria to evaluate the language program. In Yang‟s (2009) and Can‟s (2009) studies, an appropriate evaluation should be conducted at the end of the course in order to obtain much more persuasive findings rather than merely using questionnaires and interviews. Undoubtedly, there is a necessity of more empirical studies to investigate the effects. 政 治 大. of TBI on foreign language learning.. 立. Adding these together, the present study adopted an empirical research and. ‧ 國. 學. aimed at investigating the effects of TBI on EFL elementary students in Taiwan.. ‧. Additionally, one of the major goals of the new language policy for elementary level set by the MOE is to enhance learners‟ oral communicative competence; however,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. few previous studies focused on oral aspect. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to examine the effects of theme-based oral instruction (TBOI) on learners‟. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. oral communicative competence. Also, the attitudes and motivation toward English. engchi. learning through the implementation of TBOI were investigated in this study..

(34) CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY. This chapter consists of six sections. The first section briefly introduces the characteristics of the subjects. In the second section, instruments used in this study are illustrated. The whole procedure of this study is presented in the following section. The theme-based oral instruction (TBOI) for experimental group and the traditional oral instruction for the control group are described in the fourth and fifth sections. The final section deals with data analysis.. 立. 政 治 大 Subjects. ‧ 國. 學. The participants consisted of two fifth-grade classes in a public elementary. ‧. school in Douliou City, the capital of the Yunlin County. All the participants had. sit. y. Nat. completed more than two years of formal English instruction in the public school. io. er. with an average of two 40-minute English lessons per week. Moreover, 80% of them. al. attended extra English instruction after school. The students in this study had similar. n. iv n C educational background to mosthof the other students e n g c h i U in the EFL context of Taiwan. The two classes were randomly assigned to experimental group (EG) and control group (CG). The experimental group comprised 30 students who received the TBOI. Another 31 students served as a control group receiving the traditional oral training. An English Oral Proficiency Test (EOPT) was conducted to examine whether the two groups were at the similar language proficiency level at the beginning, and there was no significant difference in the results (p = .898). In addition, both groups were taught by the same instructor, the researcher, using the same textbook.. 24.

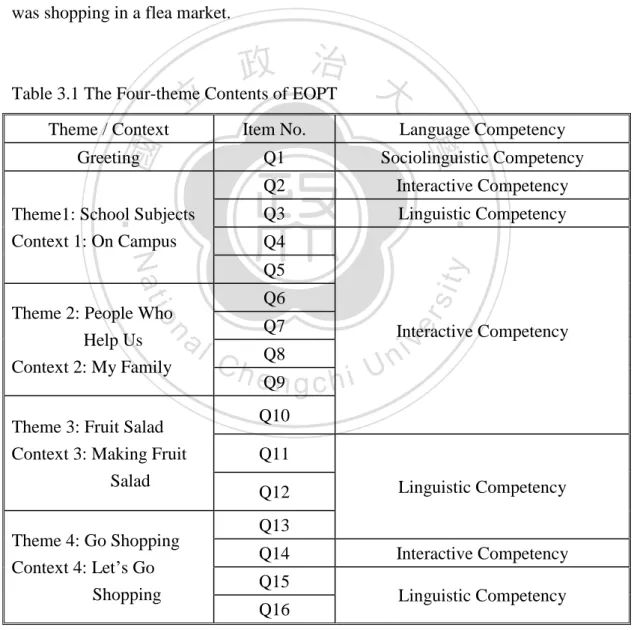

(35) 25. Instruments This study employed two instruments to measure the achievement of this study: an English oral proficiency test (EOPT) to exam learners‟ oral communication skill and a questionnaire to assess learning attitudes and motivation.. English Oral Proficiency Test (EOPT) In order to measure the effects of theme-based oral instruction (TBOI) on subjects‟ oral communicative competence, this study adapted Lee‟s (2008) English. 政 治 大. oral proficiency test as the pre-test and the post-test. The pre-test was also used to. 立. examine whether two groups were at similar English oral proficiency level in the. ‧ 國. 學. beginning of the research (mentioned in the section Subjects).. ‧. Due to the context differences, the questions and pictures had been modified based on the themes and the learning contents in this study (see Appendix A). The. y. Nat. er. io. sit. English proficiency test (EOPT) in this study included 16 questions which are categorized into four major themes, with three components: linguistic competency. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. (6 questions), interactive competency (9 questions) and sociolinguistic competency. engchi. (1 question) (Bachman, 1990; Lee, 2008; Nakamura, 2005), as shown in Table 3.1. Since the focus of theme one was on school subjects, the context was set on campus with pictures concerning the timetable and different subject lessons. The distribution of questions in School Subject Theme was from question 2 to question 5. The topic for theme two was regarding People Who Help Us, and the questions were distributed from question 6 to question 9. Since family members and their jobs have much more influence on learners‟ daily life, the family context has been selected for this theme..

(36) 26. Theme three was dealing with Fruit Salad, and the questions distribution was from question 10 to question 12. The main activities of this theme were around “Making Fruit Salad”, so it was also chosen as the context. The topic of theme four was Go Shopping, and the questions were distributed from question 13 to question 16. Since all the learners shared the same experiences of participating in the school flea market every semester, the context for this theme was shopping in a flea market.. 政 治 大 Table 3.1 The Four-theme Contents of EOPT 立. Language Competency. Q1. Sociolinguistic Competency. Q2. Interactive Competency. Q3. Linguistic Competency. Greeting. Q6 Q7. n. al. Ch. Q8. eQ9n g c h i. er. io. sit. Q5. Theme 3: Fruit Salad Context 3: Making Fruit Salad Theme 4: Go Shopping Context 4: Let‟s Go Shopping. y. Q4. Nat Theme 2: People Who Help Us Context 2: My Family. ‧. Theme1: School Subjects Context 1: On Campus. 學. Item No.. ‧ 國. Theme / Context. Interactive Competency. i Un. v. Q10 Q11 Q12. Linguistic Competency. Q13 Q14 Q15 Q16. Interactive Competency Linguistic Competency. Due to the lack of language laboratory, the oral tape-recording test format in Lee‟s study was not considered in the present study setting. Therefore, both the.

(37) 27. pre-and post-oral tests were all administrated by the researcher using a face-to face oral test format in which one oral examiner assessed individual student privately, i.e. one to one format (1:1 format). According to the Research Notes of the Cambridge Young Learners‟ English Test, the examiner did serve as the student‟s partner, comforting students‟ stress, interacting with the examinee, demonstrating, and ensuring the smooth continuum of the test (Wilson, 2005). Considering the potential stress during the test process in which children would generate, the oral test was implemented in the English classroom where students would feel more familiar,. 政 治 大. natural and comfortable in producing oral performance. The examiner‟s role was to. 立. ensure that all the students understood the content of test and answered freely. In. ‧ 國. 學. addition, the whole testing procedure was recorded for later scoring. In order to. ‧. measure learners‟ oral outcome appropriately and objectively, two raters, the researcher and an English teacher in the same school, assessed participant‟s oral. y. Nat. er. io. sit. performance respectively based on the rating scale adopted from Lee‟s (2008) scoring criteria (see Appendix B). That is, four points were given to each correct. n. al. Ch. answer and the total score was 64 points.. engchi. i Un. v. English Learning Attitudes and Motivation Questionnaire Adapting from the framework of Carreira‟s (2006) Motivation and Attitudes toward Learning English Scale for Children (MALESC), an English learning attitudes and motivation questionnaire (see Appendix C, D & E) was used to investigate the changes of learners‟ attitudes and motivation after the experiment. Moreover, this study aimed at measuring learners‟ oral communicative competence from the perspective of learning attitudes and motivation. The contents of the questionnaire were much more focused on learners‟ speaking performance. To.

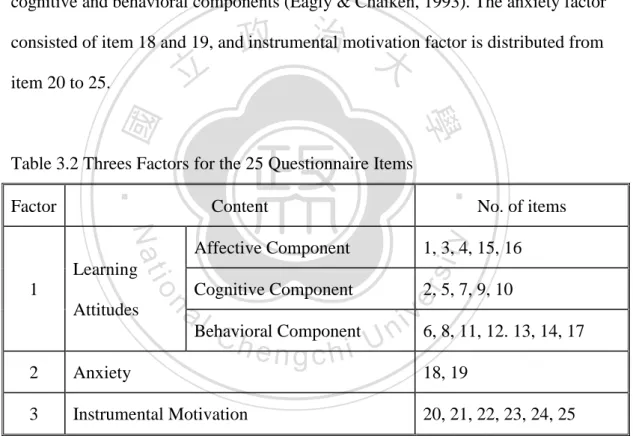

(38) 28. assess the face validity, the questionnaire has been judged by two English teachers working at the implementing elementary school. The contents of the learning attitudes and motivation questionnaire in the present study were categorized into three main factors including learning attitudes factor, anxiety factor and instrument motivation factor, with 25 items as shown in Table 3.2. There were 17 items (from item 1 to 17) concerning the learning attitudes factor, and were subcategorized into three attitude components, the affective, cognitive and behavioral components (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). The anxiety factor. 政 治 大. consisted of item 18 and 19, and instrumental motivation factor is distributed from. 立. item 20 to 25.. ‧ 國. 學. Table 3.2 Threes Factors for the 25 Questionnaire Items. Affective Component. sit. Cognitive Component. 2, 5, 7, 9, 10. n. al. Ch. Behavioral Component. 2. Anxiety. 3. Instrumental Motivation. engchi. 1, 3, 4, 15, 16. er. io. Attitudes. No. of items. y. Content. Nat. Learning 1. ‧. Factor. i Un. v. 6, 8, 11, 12. 13, 14, 17 18, 19 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25. In addition, taking Dörnyei‟s (2001) suggestion into consideration, this study applied an even-number response options to avoid the possibility that some respondents often tended to choose the neutral alternative, (i.e., “neither agree nor disagree”, “not sure”, or “neutral”). Thus, this study adopted a four-point Likert scale (i.e. strongly agree = 4, agree = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1)..

(39) 29. Procedure This study was conducted to examine if TBOI could benefit learners‟ oral communicative competence and to investigate if their English learning motivation and attitudes has changed. The research procedure comprised two stages: pilot study and main study. The pilot study lasted for three weeks at the beginning of the semester, and the main study was running for the following 12 weeks as shown in Figure 3.1. In the pilot study stage, to make sure that the instruction procedure and the. 政 治 大. materials were appropriate, the first theme of TBOI was conducted in one fifth-grade. 立. class with 33 pupils running for 3 weeks, one month before the main study (in. ‧ 國. 學. September, 2009) . As for the EOPT and questionnaire, to test the face validity, both. ‧. the EOPT and questionnaire had been evaluated by one university professor and two elementary school English teachers before the implementation of the study.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Inappropriate items were revised based on the professor‟s and teachers‟ suggestions. For example, the description of Q11 in the EOPT was difficult to young learners.. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. The description was revised and became shorter and easier. The pictures shown in. engchi. EOPT were colorful rather than printed in black and white after modification. Then, the EOPT and questionnaire were conducted to the fifth-grade class for test reliability measured by Cronbach‟s α coefficient, and the internal consistency reliabilities of the EOPT and questionnaire evaluated were .933 and .930 respectively. Meanwhile, an inter-rater reliability analysis using the Kappa statistic was also performed to determine consistency between two raters, and the result was considered acceptable (Kappa =.887 with p < 0.001). At the beginning of the main study stage, the pre-EOPT was used to examine whether the subjects of two groups were at similar English oral proficiency level.

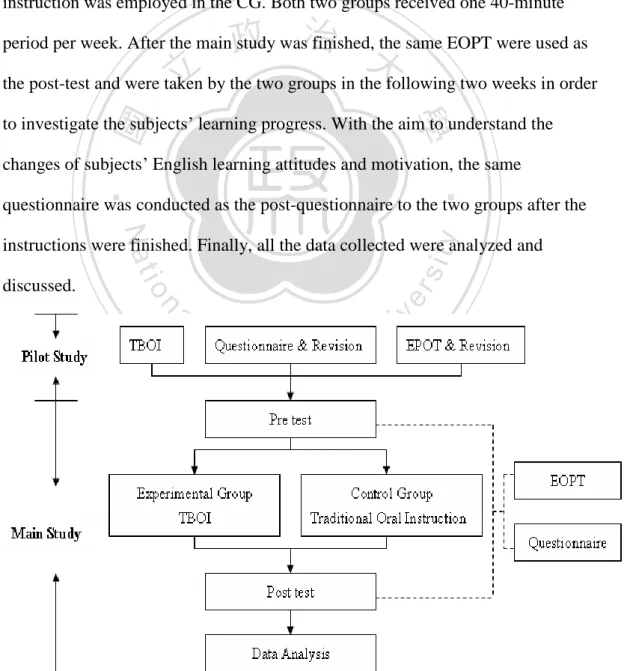

(40) 30. two weeks before the main study. Since the EOPT was quite time-consuming, a 40-minute period at noon break-time per day lasting for 2 weeks before the instruction was taken to conduct the test. In each period (40 minutes), there were eight students taking the EOPT. Meanwhile, the pre-questionnaire was conducted to both EG and CG in the class one week before the main study. The main study was implemented for 12 weeks from the beginning of October 2009 to the end of December 2009. The EG received TBOI and the traditional oral instruction was employed in the CG. Both two groups received one 40-minute. 政 治 大. period per week. After the main study was finished, the same EOPT were used as. 立. the post-test and were taken by the two groups in the following two weeks in order. ‧ 國. 學. to investigate the subjects‟ learning progress. With the aim to understand the changes of subjects‟ English learning attitudes and motivation, the same. ‧. questionnaire was conducted as the post-questionnaire to the two groups after the. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. discussed.. sit. instructions were finished. Finally, all the data collected were analyzed and. Ch. engchi. i Un. Figure 3.1 Flow Chart of the Research Procedure. v.

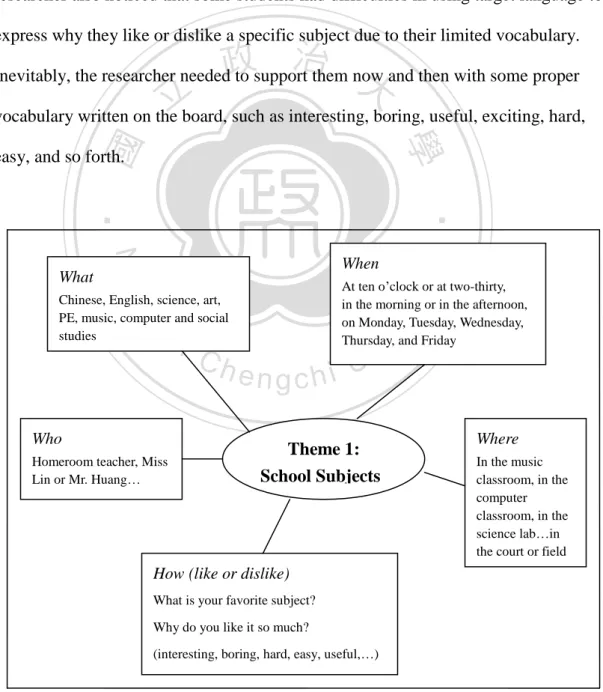

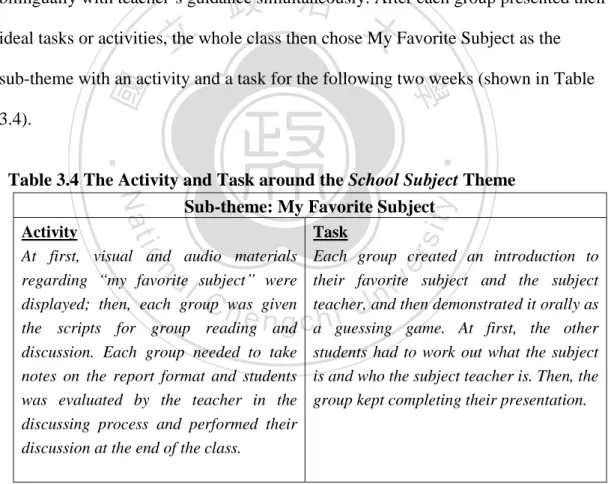

(41) 31. Theme-Based Oral Instruction for EG The theme-based oral instruction (TBOI) lasted for 12 weeks, and EG took one 45-minute period of English class per week. Based on the content of the textbook, Here We Go (Longman, 2009), four units were chosen as the main themes in the study. These four themes are School Subjects, People Who Help Us, Fruit Salad, and Go Shopping. With the goal for conducting TBOI successfully and appropriately, the first theme, School Subjects, was employed in the pilot study for three weeks before the. 政 治 大. main study. Since the first theme has been worked smoothly in the pilot study, the. 立. teacher duplicated the instruction procedure in the pilot study to the EG including. ‧ 國. 學. the implementing process and the main teaching contents (see Appendix F). In this section, the instruction procedure was described first, followed by. ‧. instruction teaching process.. n. er. io. Ch. sit. y. Nat. al. Instruction Procedure. i Un. v. Base on the schedule of school curriculum, each theme has been implemented. engchi. for three weeks, and the main activities for each week were showed in the following table (see Table 3.3). Table 3.3 The Time Table and the Main Activities for Each Theme Week 1. Theme brainstorming and webbing sub-themes 2 main activities or tasks selection. Week 2. The implementation of the first activity or task.. Week 3. The implementation of the second activity or task.. At the first week, the teacher discussed the theme with students using two basic planning tools, brainstorming and webs. The main theme was put in the center of the.

數據

相關文件

吳佳勳 助研究員 國立台灣大學農經博士 葉長城 助研究員 國立政治大學政治學系博士 吳玉瑩 助研究員 國立台灣大學經濟博士 陳逸潔 分析師 國立台灣大學農經系博士生 林長慶

依據教育部臺教師(二)字第 1070199256 號,辦理國小全英語教學之教師專業成長工作

國立政治大學應用數學系 林景隆 教授 國立成功大學數學系 許元春召集人.

To provide suggestions on the learning and teaching activities, strategies and resources for incorporating the major updates in the school English language

“Filmit 2020: A Student FilmCompetition” is a film making competition involving oral and written narration based on a theme provided by the NET Section and the European Union

Thus, our future instruction may take advantages from both the Web-based instruction and the traditional way.. Keywords:Traditional Instruction、Web-based Instruction、Teaching media

This study primarily represents a collaborative effort between researchers and in-service teachers in designing teaching activities and developing history of mathematics

中學中國語文科 小學中國語文科 中學英國語文科 小學英國語文科 中學數學科 小學數學科.