國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士班碩士論文

指導教授:尤雪瑛博士

Advisor:Dr. Hsueh-ying Yu

中文題目

台灣高中生英文寫作用字分析與教學

英文題目

A Study on Teaching Vocabulary for English Writing to

Taiwanese High School Students

研究生:李芷涵

Name:Chih-han Lee

中華民國一○五年六月

June, 2016

A Study on Teaching Vocabulary for English Writing to

Taiwanese High School Students

A Dissertation

Submitted to

Department of English,

National Chengchi University

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

by

Chih-han Lee

iii

Acknowledgements

I would like to give thanks to the following people for their aid in the completion of my thesis. Without them, the work could not have been finished so efficiently.

First of all, I want to express my deepest gratitude to my dearest advisor, Dr. Hsueh-ying Yu, who have always been my role model for her devotion to education, her expertise in research, her wisdom in life, and her humility and tenderness towards people. Without her constructive advice on my academics and timely guidance for my life, I would not have accomplished this difficult task – and I feel really blessed to have such an amazing mentor in my life. Also gratefully acknowledged are my two committee members, Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh and Dr. Yi-ping Huang, who offered insightful suggestions concerning the application of related literature, the overall research design, and further improvement of this study.

My appreciation also goes to my English teacher, Hui-ping Liu, who always has confidence in me and has been encouraging me throughout my teaching career. Her example has influenced me profoundly to grow as a professional and vigorous teacher. I would also like to thank the seniors in my graduate school, Claire Liu, Carlos Kang, and Effie Wang, for their constant assistance and companionship during the process. In addition, I am grateful for the wonderful people from the school where I am currently teaching – particularly my sweet students who had been participating actively in the research and my heart-warming colleagues who had supported me.

Last but not least, I owe my beloved family, particularly my mother and sister, my sincerest thanks. With their unconditional love, care, and patience, I was able to complete my thesis. Most importantly, I would love to praise the Lord my shepherd, whose goodness and love have been following me and whose grace have been sufficient for the completion of this work.

iv

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements……… iii

List of Figures………. vi

List of Tables………. vii

Chinese Abstract………viii

English Abstract……….. ix

Chapter I. Introduction ... 1

Background and Motivation ... 1

Research Purposes and Research Questions ... 3

Significance of the Study ... 3

II. Literature Review... 5

Vocabulary in Language Learning ... 5

The Nature of Word Knowledge ... 8

Principles of Teaching Vocabulary ... 12

Measurements of Productive Vocabulary ... 16

Vocabulary Instruction in Taiwan ... 20

III. Methodology ... 25

Contexts ... 25

Instruments ... 26

Procedures ... 28

v

IV. Results and Discussion ... 39

Analyses of the VKS ... 39

Analyses of the Writing Task ... 46

Observations during the Teaching Experiment ... 58

V. Conclusion ... 61

Summaries of the Teaching Activities ... 61

Findings... 62

Pedagogical Implications... 64

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research ... 65

References ... 68

vi

List of Figures

Figure 1. The VKS Elicitation Scale (Paribakht & Wesche, 1997) ………19 Figure 2. The VKS Scoring Categories (Paribakht & Wesche, 1997) ………20

vii

List of Tables

Table 1. The Number of Words Required for Different Educational Stages………...21

Table 2. Target Words ……… 27

Table 3. The Results of the VKS in the Pre-Test……… 40

Table 4. The Results of the VKS in the Post-Test………41

Table 5. The VKS Scores of Target Words………..………43

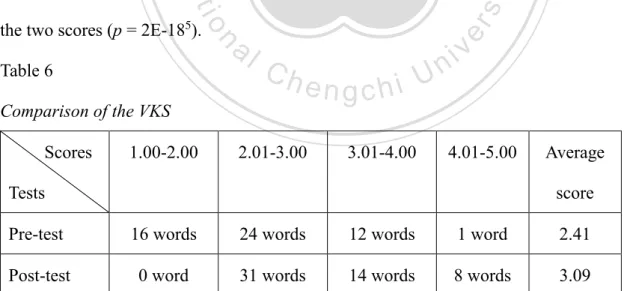

Table 6. Comparison of the VKS……….………44

Table 7. The Results of the Writing Task in the Pre-Test………48

Table 8. The Results of the Writing Task in the Post-Test………..……49

Table 9. Comparison of the Three Students………56

viii

國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士班

碩士論文提要

論文名稱:台灣高中生英文寫作用字分析與教學 指導教授:尤雪瑛博士 研究生:李芷涵 論文提要內容: 本研究旨在實驗一套單字教學活動是否能成功增加台灣高中生的寫作應用 字彙。在實驗開始前,研究者先進行前測,採用了字彙知識自評表(Vocabulary Knowledge Scale)和一份作文題目以了解學生一開始的字彙知識及主要單字的使 用情況。之後,研究者開始了為期十二週的教學活動,此活動分為三階段:呈現 (Presentation)、練習(Practice)、應用(Production),每個階段皆採用不同的活動進 行教學,並根據這四大原則來設計教導應用字彙的活動:刻意性、重複性、參與 性、情境性。教學實驗過後,研究者進行後測以了解字彙知識的改變及主要單字 的使用情況,並分析不同程度的學生作品,以了解學生實際的用字情況。 研究結果顯示,本教學活動能有效增進學生的辨識字彙能力及字彙的應用。 字彙知識自評表顯示前後測分數有顯著性差異,在後測中,超過半數以上的單字 進步到比前測更高的等級,而且有八個字進升到應用字彙的程度。百分之八十七 的學生有把主要字彙用在他們的作文中,且正確的使用頻率及相關單字的使用也 增加了,無論是新字或舊字,在後測的使用數量都是前測的兩倍。 關鍵字:字彙知識、字彙習得、應用字彙、字彙知識自評表、英文寫作ix

Abstract

The current study experiments with a series of teaching activities for productive words to Taiwanese students at the senior high level. It aims to understand the changes of word knowledge and target word use after the experiment. In the beginning, a pre-test was administered with the help of two instruments, the

Vocabulary Knowledge Scale and a writing prompt, to understand the students’ initial level. Then, the researcher conducted the teaching experiment for 12 weeks, which consisted of the Presentation, Practice, and Production stages. In each stage, the activities were designed based on four important principles for teaching productive words: intentional, repeated, involving, and contextualized. After the experiment, a post-test using the same instruments was carried out to analyze the changes of word knowledge and target word use. Moreover, individual writing products of different levels were analyzed to see the actual usage of words in the students’ writing.

The results showed that the teaching experiment was effective in increasing the students’ receptive knowledge and productive use of the target words. The VKS scores of the pre- and post-test differed significantly. More than half of the words moved up to higher levels, and eight words moved to the productive level in the post-test. The students’ writing products also indicated a considerable increase in the use of target words in terms of the correct usages and related words. Eighty-seven percent of the students used the target words in the post-test. Moreover, the number of old and new words used doubled in the post-test.

Keywords: word knowledge, vocabulary acquisition, productive words, Vocabulary Knowledge Scale, English writing

1

CHAPTER 1 Introduction

This chapter first introduces the background and motivation of the current study. The second section states the research purposes and questions to be explored in the study. Last, the significance of the study is proposed in terms of how it may contribute to the understanding of teaching productive words.

Background and Motivation

Learning a second or foreign language requires learners to familiarize themselves with a different system of sound, vocabulary, and grammar of the language. Among the various aspects, vocabulary is the most important for learners to be able to

communicate in the language. Many studies have shown that vocabulary knowledge is highly correlated with learners’ performance in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. The importance of vocabulary is vividly depicted by Wilkins (1972), “Without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” (p. 111).

Despite its importance, vocabulary has long been considered one of the most difficult aspects for language learning, especially for learners of English. First of all, there are vast amounts of vocabulary to learn, and the amount continues to grow year by year. Furthermore, the difficulty is not only about acquiring adequate amount of words but also about learning to use the words appropriately. Learners may know the meanings of a word, but cannot spell it correctly or use it in writing sentences or passages. There is a discrepancy between the words that they can recognize and those they can produce, and the number of receptive words is much more than that of the productive words (Webb, 2008). However, in everyday communication, both the receptive words and productive words are needed in order to understand, interpret, and express one's ideas. Such discrepancy often frustrates learners, as their efforts of

2

increasing the words for production often turn out to be futile.

The discrepancy may result from the fact that vocabulary instruction in EFL contexts has put more emphasis on receptive words than on productive words (Moskovsky, Jiang, Libert, & Fagan, 2015). EFL learners are often instructed to remember words from wordlists, vocabulary books, or reading passages. On

textbooks, example sentences may also be provided to help learners learn the word, its collocations, or derivations. However, these approaches do not succeed in making the target words become productive vocabulary. Even if teachers hope to do so,

approaches and activities for teaching productive words are still lacking in many of the English learning programs or courses.

Teaching productive words can be a difficult task for English teachers in EFL contexts because of the various aspects it involves (Nation, 2001). First, the spellings of English words are often confusing and may be different from learners’ native language. After learning the spellings, learners need to establish the form-meaning link of the new word. Then, to use the word correctly, the part of speech and collocations are also necessary. For learners at even higher levels, they have to

distinguish the subtle differences and connotations among many similar words so that they can use the words properly. With so many aspects to cover, it is no wonder that teachers find it impossible to teach productive words within the limited instruction time.

With so many aspects to cover, productive words are challenging not only for teaching but also for researching. In the literature, there are many studies on vocabulary acquisition, vocabulary knowledge, vocabulary size, and vocabulary assessment. However, most of them mainly focus on words for recognition, and only few are dedicated to productive words. Few studies have addressed how great the gap between receptive words and productive words may be and how teaching can fill up

3

the gap. Given the importance of productive words and lack of relevant research, the present study seeks to provide a method of teaching productive words with the hope to attract the attention from teachers and researchers.

Research Purposes and Research Questions

With the above mentioned problems, the current study aims to conduct a teaching experiment of productive vocabulary in an EFL setting and evaluate its effectiveness. The teacher-researcher will choose target words for productive purposes and designed a teaching experiment. Afterwards, the students' performances before and after the experiment are compared to examine the effectiveness of the teaching experiment. The first aim is to see if there are any changes in the students' vocabulary knowledge, as measured by the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale developed by Wesche & Paribakht (1996). The second aim is to compare and analyze the students’ writing products to see how they use the target words before and after the experiment.

With the purposes in mind, the teacher-researcher addresses the following two research questions in the current study:

1: What are the changes of the students’ knowledge of the target words before and after the experiment?

2: What are the changes of the use of target words in writing tasks before and after the experiment?

Significance of the Study

The current study attempts to develop a method for teaching productive vocabulary for senior high school students in Taiwan. It can inform teachers and researchers of the content of word knowledge, and the acquisition of such knowledge, which may serve as the basis of vocabulary teaching courses. The study also

demonstrates how the activities for teaching productive words can be incorporated with the regular teaching schedule. Teachers and practitioners can design practical

4

courses for teaching productive words in their regular programs. In particular, the activities, approaches, and principles proposed in the current study can be used as references in turning students’ receptive words into productive words for teachers in EFL contexts.

5

CHAPTER 2 Literature Review

The chapter reviews literature on teaching vocabulary related to the current study. The first section introduces the role of vocabulary in language learning by highlighting its importance and pointing out learners’ difficulty. The second section focuses on the nature of vocabulary knowledge, particularly on studies on vocabulary size and depth, and on how to bring receptive words into productive words. Next, the third section reviews the principles of teaching vocabulary, which covers the selection of words and methods and principles of vocabulary teaching. The fourth section includes studies on various measurements of productive words. The final section reviews relevant studies on teaching vocabulary to Taiwanese students.

Vocabulary in Language Learning

In the section, the central role vocabulary plays in language learning is first reviewed. After that, learners’ difficulty and possible sources of the difficulties are outlined and explored from a general perspective to a more specific one.

The Importance of Vocabulary

“Without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” (Wilkins, 1972, p.111). The famous comment pinpoints the critical role of vocabulary, which has been recognized by teachers and researchers in the field of language teaching. Various studies of L1 and L2 learning reported that vocabulary is the building blocks of a language. Learners can communicate in the target language even with limited number of words (Nation & Crabbe, 1991).

Various studies have shown that learners’ vocabulary size correlated with their performance in the receptive and productive skills. Learners’ vocabulary size has been found to correlate with reading comprehension and strongly predict students’

6

Zhang, 2012). As for listening comprehension, studies have shown that learners needed to know at least 90 percent of the words in a passage to understand it (Stæhr, 2009; Zeeland & Schmitt, 2012). Furthermore, to communicate in English, learners need a large amount of vocabulary for the more challenging productive skills. Hilton (2008) investigated spoken language from corpus and suggested that the

“disfluencies” or hesitations were the result of lack of lexical knowledge. Yu (2009) measured lexical diversity and found it to correlate significantly with students’ overall task performances on speaking and writing. Additionally, Stæhr (2008) proved the significance of vocabulary size for language proficiency, as evident from the skills of listening, reading, and writing. Vocabulary, therefore, is critical for receptive and productive skills, and for both the spoken and written form (Schmitt, 2008).

Since vocabulary plays such a significant role in learning a language, it is

especially necessary for EFL teachers to put emphasis on learners’ vocabulary size. In Taiwan, according to the report on the twelve-year compulsory education (Chang, 2013), the vocabulary size of different stages was explicated. For students in

elementary schools, the focus is on the spoken language, with 300 words to use orally and 180 words for spelling. For those in junior high, the goal is that students can use 900 words orally and 1,020 words for writing. Students graduating from junior high are expected to have learned around 1,200 productive words, a figure close to those of Japan, Korea, and China. However, the issue of vocabulary size becomes complicated in the senior high due to various versions aiming at differentiated teaching. Generally speaking, senior high graduates are expected to have around 4,000 words for the Proficiency Test and 7,000 words for the Joint College Entrance Exam. Though the figures seem to match the minimal lexical threshold suggested by Laufer &

Ravenhorst-Kalovski (2010), challenges exist as to how to bridge the vocabulary size gap from junior high to senior high, as well as how many students can meet the

7

expectations. Also, it is uncertain how well students can master and use these words.

Learner Difficulty

Acquiring vocabulary involves different “learning burden”, the amount of effort needed to learn it (Nation, 2001). The learning burden of a word depends on learners’ language backgrounds and the aspects of knowledge involved. The general principle is that the more a learner is familiar with the patterns or knowledge of the word, the lighter the learning burden and the easier to learn it. Laufer (1997) pointed out the factors affecting the learnability of a word – pronounceability, orthography, length, morphology, synformy, grammar, and semantic features. Similar or consistent patterns, transparency of meanings, and one-to-one form-meaning relationships are regarded as facilitating factors. The more familiar or predictable a word is, the lighter the learning burden. On the other hand, irregularities, derivational or inflectional complexities, deceptive meanings, synformy, connotations, and strict restrictions of usage are difficulty-inducing factors. These aspects should be given special attention when teachers design a lesson to alleviate learners’ burden.

Other studies on the relationship between L1 and L2 showed learning vocabulary in a second language to be even more challenging and complicated due to various factors. Figueredo (2006), reviewing literature on the influences of L1, concluded that first language knowledge can contribute positively and negatively to ESL learners’ English spelling, and that such dependence decreases as learners advance in knowledge about English spelling norms. Willis & Ohashi (2012), in a study of Japanese EFL learners, found that cognateness best predicts difficulty in learning words, followed by frequency and word length in phonemes. Having cognates in the L1 helps vocabulary acquisition in the L2. Frequency, the chances of encountering words, plays a particularly important role due to the limited access to the target language in a foreign context.

8

As for Chinese EFL learners, the learning burden is heavier since English and Chinese differ greatly, ranging from phonological, orthographic, to socio-cultural aspects. Studies on contrastive analysis and error analysis have also indicated the areas learners grapple with. Wang, Perfetti, & Liu (2005) compared Chinese and English writing systems and pointed out three major differences: the grapheme mapping principle, the graphic form and spacial layout, and the tonal feature. While English uses alphabets (phonemic writing system), Chinese uses characters

(morphographic writing system). Different demands are required of different writing systems, resulting in challenges for Chinese students to acquire vocabulary from a completely different system.

In Pan & Wang’s study (2005), errors were categorized into lexical errors, grammatical errors, and semantic, rhetorical and stylistic errors. Among the error types, lexical errors accounted for 65 percent. The most common were word connotation and collocation, which took up nearly half of the lexical errors. The researchers proposed three causes for this: learners’ inadequate vocabulary, the confusion of synonyms and near synonyms, and wrong collocations. Learners could not express themselves without a sufficient vocabulary or might be confused by words with similar meanings but different connotations. To resolve these problems, they may choose words and collocations using the knowledge of their mother tongue, resulting in unnatural languages or errors. Tang (2006) found similar results of direct

translation of words, adding that both interference of Chinese and lexical deficiency in English affect students’ writing performance.

The Nature of Word Knowledge

Meara (1996) stated that lexical knowledge consisted of three dimensions, including vocabulary size, the speed of access, and the structures the word has in the lexicon. In the section, word knowledge is reviewed from the perspective of size and

9

depth, which includes the structures of words. After understanding the nature of word knowledge, special attention is paid on turning receptive words into productive words.

Vocabulary Size

Word knowledge is usually described by size and depth in terms. According to Schmitt (2014), size or breath of vocabulary knowledge means how many words are known. Though the concept seems quite straightforward, vocabulary size can differ in terms of how one counts words. According to Nation (2001), there are four different ways of counting – tokens, types, lemmas, and word families. Tokens refer to every single word in a text, while types refer to every word without counting the same occurrence again. Lemmas consist of a headword and the inflected and reduced forms, whereas word families include a headword, the inflected forms and closely related derivations. Each of the four ways serves different functions, and deciding the most appropriate one for research requires careful consideration.

Though previous studies varied in the ways of counting vocabulary, they agreed that vocabulary size played a crucial role in learners’ performance. Studies on the listening aspect have indicated that a certain amount of vocabulary is needed for comprehension. Stæhr (2009) suggested a consistent 98% of text coverage for

listening comprehension, and Zeeland & Schmitt (2012) indicated a minimum of 90% for native and non-native speakers, with 95% being a more reliable indicator.

Moreover, to use the language effectively, learners needed to be equipped with adequate amounts of vocabulary to function properly. According to Nation’s research (2001, 2006), the first 1,000 words of West’s General Service List cover roughly 78%-81% of the running words in written texts and 85 % in spoken texts. However, the amount might not be enough for learners. Hirsh & Nation (1992), examining the words in novels, argued that 2,000 to 3,000 words could serve as a good basis for language use under favorable conditions. In a later study, Nation (2006) pointed out

10

that if 98% is taken as the ideal amount for text coverage, learners need 8,000-9,000 word families for written texts and 6,000-7,000 for spoken texts. Laufer &

Ravenhorst-Kalovski (2010) indicated an optimal and minimal “lexical threshold” for adequate reading comprehension – 8,000 word families can cover 98% words, while a minimal of 4,000-5,000 word families would cover around 95%. Different from the most frequent 1,000 words, less common words become more difficult and

specialized, which requires learners to learn far more words if they desire to reach the lexical threshold.

Vocabulary Depth

Vocabulary depth or quality refers to how well a word is known (Schmitt, 2014). It consists of different components or aspects, which are separate yet inter-related to each other. Representative examples of this view are Richards’s (1976) definitions of vocabulary and Nation’s (2001) model. Of particular value is Nation’s model

describing nine aspects of knowing a word, which can be classified into three groups. The first group, form, includes spoken form, written form, and word parts. The second group, meaning, consists of the form and meaning, concept and referents, and

associations. The last group, use, includes grammatical functions, collocations, and constraints on use. Each of the nine aspects has a receptive and productive dimension. Nation (2001) defines “receptive” as “perceiving the form of a word while listening or reading and retrieving its meaning” (pp. 24-25), while the “productive” involves “wanting to express meaning through speaking or writing and retrieving and producing the appropriate spoken or written word form” (p. 25). With so many aspects, it seems impossible and impractical for teachers to cover all of them.

Therefore, the current study will only cover certain key aspects of word knowledge – the productive written form, meaning, and use.

11

and productive dimensions. For them, the receptive and productive are part of learners’ vocabulary knowledge, which progresses along a continuum (Melka, 1997) or goes through different stages in the learning process (Wesche & Paribakht, 1996). Laufer (1998) categorized vocabulary knowledge as having the following three components, which were passive, controlled active, and free active. Later, Henriksen (1999) was more precise in describing the development. She proposed that learners’ lexical competence developed in three dimensions – from partial to precise, from little to deeper understanding, and from receptive to productive.

From Receptive to Productive

Productive words are important due to their usefulness in communication. Research has indicated that learners’ receptive words are larger than their productive words (Webb, 2008) and the productive dimension needs specific instruction. The productive use of a word is more challenging due to the following four reasons. According to Nation (2001), the first reason, “the amount of knowledge explanation”, indicates that productive learning requires more precise knowledge. Learners need to know, for example, the spellings and uses of words, rather than merely recognizing words in speech or texts. Second, “the practice explanation” holds that learners normally have fewer chances of practice using words. Then, “the access explanation” points out that productive recall is more difficult due to many competing associations and L1 interference. Lastly, “the motivation explanation” holds that learners may not have the motivation to use certain words due to avoidance of mistakes of unfamiliar words or their personal styles and preferences.

Given the importance of productive words, several studies have attempted to increase productive words by turning receptive words into productive words (Fan, 2000; Laufer, 1998; Lee & Muncie, 2006). It was found that although more proficient learners possessed more receptive words, there was no consistent relationship

12

between the proficiency level and the number of productive words (Fan, 2000). Besides, even though learners have learned some new words, this may not be reflected in their products, making their productive words seem less (Laufer, 1998). To further push students to use the words they have learned, effective teaching activities were needed to effectively narrow the gap between receptive words and productive words (Fan, 2000; Lee & Muncie, 2006). These studies helped to understand the relationship between receptive and productive words.

Principles of Teaching Vocabulary

In the third section, relevant studies about word selection are discussed. After that, research on how to teach vocabulary is examined to provide activities and principles for teaching vocabulary effectively.

Word Selection

Before deciding the appropriate ways of teaching, it is necessary to select the target words to be taught. Two major criteria for word selection are frequency and learner needs. Teachers should focus on the most useful vocabulary – which have a wide range of use and high frequency (Nation, 2003; Read, 2004). It has been indicated the most frequent 1,000 word families were of the most learning value for beginners, and teachers should give them special attention (Nation 2001, 2003; Schmitt, 2010). In addition to frequency, the usefulness of words may also be

determined by learner needs. As learners progress, their needs and motivation should be considered since the words to be included will become more and more specialized. Therefore, learners in different learning contexts required different lists of most frequently used words. Nation (2003) explained that after learning the most frequent 1,000 words, teachers need to design a tailor-made word list based on learner needs.

Another issue in deciding the word list is the proportions of different word classes to include. Research has pointed out that the two major classes of words were

13

nouns and verbs, taking up nearly one-third and one-fifth of English words respectively (Hardie, 2007; Hudson, 1994). It is thus suggested that teachers can select more nouns and verbs to prepare students for basic communication.

Another concern is about what aspects of word knowledge should be taught. Nation (2003) suggests teaching the core meanings to make vocabulary learning more effective. However, teaching core meanings alone is insufficient since word

knowledge includes different aspects (Nation, 2001; Schmitt, 2000). It is unnecessary and impractical to include all the aspects in teaching every word. Teachers need to make choices of what to include and what not to, based on factors like students’ level and the teaching context. After choosing the words to include in a course, another important task would be to determine the appropriate ways to teach the target words.

Methods and Principles

A traditional and widely-adopted approach to language teaching has been the three-staged PPP model – Presentation, Practice, Production (Richards, 2005). In the model, learners are exposed to the target forms in context in the first stage. Then, they are required to practice the forms with predetermined structures in the second stage. Finally, they are assigned to produce the language in the third stage. Though some have criticized the model and its assumptions (e.g., Skehan, 1996), the popularity of the PPP approach is very likely to sustain due to its clearly step-by-step lesson design and a wide range of uses in class. It has also been perceived by many teachers as easier to understand and implement. Especially in Asian contexts, PPP is thought to be pragmatic and effective for language teaching (Carless, 2009). Moreover, as it is generally agreed that practice makes perfect, this is particularly helpful for lower-achievers (Maftoon & Sarem, 2012). The approach thus serves as a good language teaching model and can be used along with many other teaching methods.

14

enhancement. Awareness-raising techniques like using boldface, highlight, and underline have been found to be effective in drawing learners’ attention to the words, which could improve word learning by increasing learners’ noticing level (Nation, 2001). Increased levels of noticing help vocabulary learning, since the awareness of the linguistic features of the target language is critical according to the input

enhancement hypothesis (Smith, 1993).

Another method of word learning is the “Output Hypothesis” proposed by Swain (1985). The hypothesis argued for the indispensable role of oral or written output in language learning. The researcher further pointed out that output included four significant functions – noticing, consciousness raising, hypothesis testing, and

metacognitive knowledge, which were conducive to language learning (Swain, 1995). In other words, it was the production stage that “pushed” students to use the target words, turning the words into their productive repertoire. Thus, actual production was a critical factor in learning productive words, which has been proved in various studies (Fan, 2000; Laufer, 1998; Lee & Muncie, 2006; Nation, 2007).

In addition to enhancing input and increasing output, one effective method for vocabulary teaching is through learner collaboration. Studies have found that peer support and teaching helped L2 vocabulary learning, especially in terms of raising motivation (Assinder, 1991; Kim, 2008; Shaaban, 2006). Assinder (1991) found that peer teaching could effectively lead to peer learning in that it not only increased learners’ language skills, but also the cognitive and affective aspects for language learning. Nation (2001) also proposed peer teaching as an activity for establishing the form-meaning connection of a new word, explaining that the learner who taught learned as well as the one being taught.

Lastly, another effective method for teaching vocabulary is through integrated activities. Hinkel (2006) noted that “In an age of globalization, pragmatic objectives

15

of language learning place an increased value on integrated and dynamic multiskill instructional models with a focus on meaningful communication and the development of learners’ communicative competence” (p.113). Since language skills are used integratively in real communication, teaching vocabulary in integration with other aspects leads to L2 purposeful communication. Activities designed according to this view match the communicative approach; in particular, task-based and content-based instruction were the most adopted activities (Hinkel, 2006). Research also found that the integrated skills have the advantage of increasing vocabulary retention and writing quality over a period of time (Lee & Munice, 2006).

There are various types of vocabulary exercises that can be used for different purposes. On the whole, these activities are organized around four important principles that contribute to productive word learning particularly. These principles are synthesized from relevant sources as follows. The first principle is intentional. Though it is often suggested that both incidental and intentional learning should be included, intentional learning is especially critical because of its value for vocabulary learning (Hulstijn, 2001; Read, 2004; Schmitt, 2008). Incidental learning alone is insufficient in that the occurrences of the new words may be too few for learners to pick up. Even if the new words occur for many times, learners may not be aware of them when appearing in context. Furthermore, discrete and decontextualized study of words is helpful for learning word forms and word meanings (Schmitt, 2008). As a result, intentional learning is more effective in providing rich and elaborate processing and deliberate rehearsal activities, which is necessary for learning productive words (Hulstijn, 2001).

The second principle is repeated. Research has shown the necessity of numerous encounters with words. Some contend at least five times of exposure is required (Hatch & Brown, 1995), and others suggest multiple modes of exposure and

16

multifaceted curriculum provide better chances for learning (Hunt & Beglar, 2005; Lee & Muncie, 2006). Repetition is especially critical for L2 learners. Since they may not have many chances to encounter, use, and learn vocabulary, intentional and repetitive practice in class provides them with enough encounters to memorize the words (Zimmerman, 1997). As for the spacing of repetition, Nation (2001) points out that spaced repetition seems more effective than massed repetition. While the former involves repeating a word across an extended period of time, the latter tends to focus on a word at a time. Spaced repetition is suggested because it works better for long-term memory.

The third principle is involving. Students are found to learn more effectively when involved with deeper levels of processing words that require more efforts (Hulstijn & Laufer, 2001; Sokmen, 1997). Various activities and techniques, such as preteaching, semantic mapping or word guess, can stimulate students’ motivation to use the new words. In particular, actual production is critical for learning words productively (Lee & Muncie, 2006; Sokmen, 1997).

The last principle is contextualized. Contexts aid learners in learning different meanings, usages and collocations of words as well as give more chances of repetition. As a result, it is suggested that students be exposed to and practice using words in different contexts (Fan, 2000; Lee & Muncie, 2006; Nation, 2001;

Zimmerman, 1997). The four principles are the basis for the design of the current research, put into practice in the methodology part.

Measurements of Productive Vocabulary

The section focuses on several widely adopted ways of measuring learners’ productive words. One is to measure learners’ vocabulary directly through discrete-point tests. Another is to analyze learners’ word use in their written products with the help of computer or statistics. Finally, learners’ vocabulary knowledge can also be

17

revealed through learners’ self-report, based on how well they think they know the words.

Discrete-point Tests

Read (2000) defined discrete-point tests as focusing on learners’ “knowledge of individual structural elements of the language” (p. 77). Common test items of this kind include multiple choice, matching, blank-filling, and word translation (Read, 2000). This kind of test has been widely used in tests of vocabulary, such as the Vocabulary Levels Test (Nation, 1983). From this test, Laufer and Nation (1999) developed the Productive Levels Test, which had two equivalent versions for four frequency levels. The test items were 18 words from each of the 2000, 3000, 5000, and 10000 word levels. Learners had to fill in the gap of a sentence containing the first few letters of the word tested. A learner’s knowledge was revealed through the percentage of words known in a level. If he/she answered 9 out of 18 items correctly at the 2000 level, that roughly represented a 50 percent of knowledge of the words at that level.

The Productive Levels Test has its advantages and disadvantages for

measurements of productive words. It resembles the traditional paper-and-pencil test, and teachers and students are more familiar with its format. Also, it is easier to design, administer, and grade in classroom settings. However, grades of such test do not necessarily reflect learners’ productive words. Though the developers of the test claimed that the test was reliable, valid and practical in measuring vocabulary growth (Laufer & Nation, 1999), such test seems to focus more on rote memorization rather than creative uses of words.

Learners’ Written Products

To measure learners’ productive words in their written products, literature has pointed out four widely-adopted measures (Laufer & Nation, 1995). Lexical

18

originality indicates the percentage of words unique to the user. Lexical density refers to the percentage of content words versus function words in texts. Lexical

sophistication is the ratio of advanced words to common words. Lastly, lexical variation shows the type-token ratio in texts. Laufer & Nation (1995) proposed another measurement, the Lexical Frequency Profile (LFP). They explained that the LFP could test the lexical richness in written products and that it could indicate the size of learners’ productive vocabulary. Learners were often required to write more than two hundred words, and their products were analyzed with the help of computer softwares. Words found in learners’ compositions were categorized to four bands based on frequency. Then, the words were further analyzed according to indicators like numbers of word families used, type-token ratios, sophisticated or unique words and so forth.

Analyzing students’ authentic written products may seem more natural and useful than discrete-point tests, but research has also pointed out several drawbacks of this approach. The LFP could measure learners’ changes of vocabulary richness and lexical variation in the long-term (Laufer, 1994). However, statistical data do not offer much information for researchers to interpret the results. Later studies also pointed out that the LFP could not completely reflect word knowledge as the researchers had claimed (Goodfellow, Lamy, & Jones, 2002). They contended that the LFP was effective in taking the concept of word frequency into account. However, categorizing words into four broad bands may neglect the roles individual words play in texts. Besides, some of the changes in word knowledge could not be reflected in the results of the LFP (Muncie, 2002).

Learners’ Self-Report

Different from the previous approaches, the last way of measuring productive words is not through tests but through learners’ self-evaluation. One of the most

19

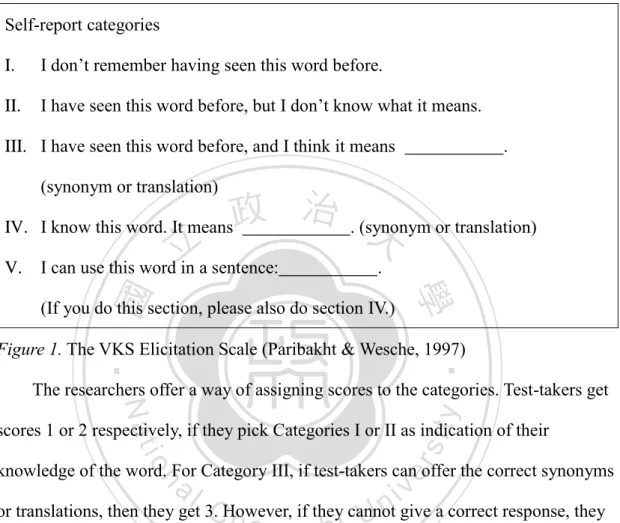

widely-adopted one is the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale, developed by Paribakht & Wesche (1997). The VKS requires learners to report how well they know a word on a scale of five degrees and provide evidence for their self-evaluation. Figure 1 shows the five self-report categories.

Self-report categories

I. I don’t remember having seen this word before.

II. I have seen this word before, but I don’t know what it means. III. I have seen this word before, and I think it means .

(synonym or translation)

IV. I know this word. It means . (synonym or translation) V. I can use this word in a sentence: .

(If you do this section, please also do section IV.)

Figure 1. The VKS Elicitation Scale (Paribakht & Wesche, 1997)

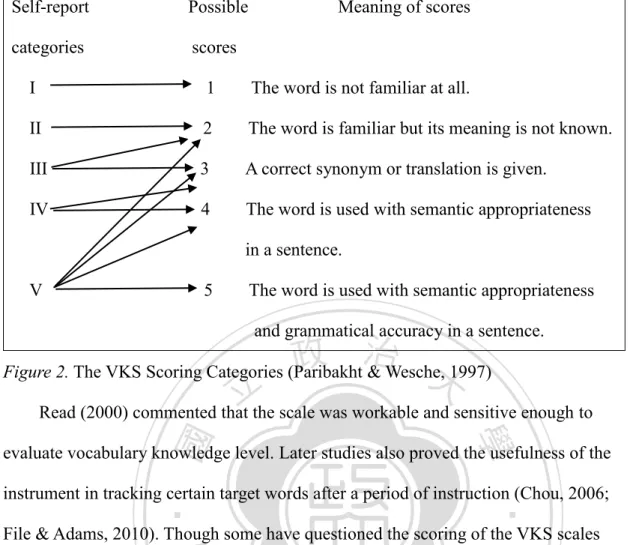

The researchers offer a way of assigning scores to the categories. Test-takers get scores 1 or 2 respectively, if they pick Categories I or II as indication of their

knowledge of the word. For Category III, if test-takers can offer the correct synonyms or translations, then they get 3. However, if they cannot give a correct response, they receive score 2. Score 4 means that test-takers can offer acceptable meanings, but the part of speech is incorrect. Score 5 means that test-takers can use the word correctly in terms of meaning and grammar, and that test-takers possess productive knowledge of the word. Figure 2 shows the categories, the possible scores, and the meanings of scores.

20

Self-report Possible Meaning of scores categories scores

I 1 The word is not familiar at all.

II 2 The word is familiar but its meaning is not known. III 3 A correct synonym or translation is given.

IV 4 The word is used with semantic appropriateness in a sentence.

V 5 The word is used with semantic appropriateness and grammatical accuracy in a sentence.

Figure 2. The VKS Scoring Categories (Paribakht & Wesche, 1997)

Read (2000) commented that the scale was workable and sensitive enough to evaluate vocabulary knowledge level. Later studies also proved the usefulness of the instrument in tracking certain target words after a period of instruction (Chou, 2006; File & Adams, 2010). Though some have questioned the scoring of the VKS scales and the use of decontextualized prompts (Bruton, 2009), the VKS is still widely used due to its value for empirical research (Lin, 2015; Min, 2008). In light of this, the current study will make use of the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale to gain more information on learners’ vocabulary knowledge.

Vocabulary Instruction in Taiwan

Educators of English in Taiwan, like many others in EFL contexts, are faced with a lot of difficulties. In an insightful article, Chang (2014) has pointed out that English teachers in Taiwan need to reflect on the effectiveness of English education. The language is still widely considered as a foreign language used only by limited population. In addition to that, many students tend to view English just as a school subject and study it for exams. What’s worse, many teachers tend to focus more on teaching linguistic knowledge and neglect the pragmatic aspects of language use in

21

real contexts. All of these factors contribute to low motivation for English, or as Chang (2014) put it, “apathy” toward learning English.

Though the situation may seem gloomy, the educators in Taiwan still strive hard to improve students’ English. In a detailed review of the studies (Chen & Tsai, 2012), the researchers examined several widely-acknowledged local journals and conference papers on English teaching and learning in Taiwan from 2004 to 2009. They found that the studies have followed international trends and catered to students’ needs. Moreover, they further categorized three common themes of the research conducted in this period, which were English education, skills development, and assessment.

Among the vast amount of literature, a small body of research on skills

development focuses on vocabulary instruction in Taiwan. One important issue relates to the vocabulary size of Taiwanese students. Yang (2006) examined the curriculum requirements for different educational stages. Table 1 shows the results of the number of words required for each stage.

Table 1

The Number of Words Required for Different Educational Stages

Stages Word types

elementary school junior high senior high

For recognition about 500-600 2,000 5,600

For production 300 (oral); 180 (written)

1,200 about 3,360

Note. Adapted from On the Issue of Vocabulary Size in English Teaching in Taiwan,

p. 38, by Yang, 2006.

Yang (2006) commented that the required vocabulary sizes for junior high and senior high students were sufficient for text coverage. However, what the researcher failed to notice was that there was a big gap between the vocabulary size of junior

22

high and that of senior high. In another study, Wang (2004) noted that such gap

resulted in great learner difficulties. Freshmen of senior high often found it difficult to keep up with the great increase of vocabulary size and the demanding vocabulary practices.

In addition to the issue of vocabulary size, other studies have approached vocabulary instruction in Taiwan from the aspect of vocabulary learning strategies. Wang (2004) found that students at the senior high level knew little about vocabulary learning strategies. It was reported that they did not use strategies frequently, or only used multimedia or mnemonic techniques once in a while to help memorize new words. However, in a larger scale study of students at different educational levels, it has been found that students used several strategies and believed these strategies to be helpful. Among them, the most widely adopted was dictionary use (Tsai & Chang, 2009; Wu, 2005). Studies also agreed that students at higher proficiency levels employed vocabulary learning strategies better and more frequently, and that explicit teaching and training could bring about positive effects in strategy use, especially for lower-achievers (Lai, 2013; Tsai & Chang, 2009).

Another important line of research has focused on different ways of vocabulary teaching in Taiwan. One of the studies experimented problem-based learning with elementary school students and found the approach effective. Since it provided excellent opportunities for students to practice using the target words in contexts, students acquired words beyond their level and could use the words productively (Lin, 2015). Another study investigated the current practices for vocabulary teaching in senior high schools. The results showed that teachers often taught words from the example sentences on textbooks, reviewing relevant old words and teaching new information at the same time (Wang, 2004). Still another research compared the long-term effects of reading plus vocabulary-enhancement activities versus that of narrow

23

reading. The result was in accord with previous literature in that it proved vocabulary gains through reading and vocabulary supplemental activities (Min, 2008).

Though attempts have been made to understand vocabulary instruction in Taiwan, studies on effective methods for vocabulary teaching are still quite limited. Only few studies have investigated vocabulary teaching to students at the senior high level. Rare studies are conducted to develop teaching methods that can effectively increase students’ productive vocabulary in secondary schools in an EFL context like Taiwan. Thus, the current research intends to bridge the gap through finding out effective methods of teaching productive vocabulary to senior high students in Taiwan.

25

CHAPTER 3 Methodology

The methodology of the study included four parts: the context of the current study, the instruments used, the research procedures, and the data analysis method.

Context

The current study was a case study reporting the long-term effects of a teaching experiment of productive vocabulary to Taiwanese students at the senior high level. The participants of the study came from a public high school in Miaoli County, the north-central part of Taiwan. The school, where the teacher-researcher worked as a regular English teacher, was located in a rural area, with roughly one hundred forty students in a grade. The school was extremely new, having the first graduates from senior high in 2016. The small number of students and the young age of the school contributed to its relatively few resources in terms of finances and human resources.

The participants of the current study were 39 eleventh graders from a class the teacher-researcher taught. The class consisted of nearly a quarter of male students, and the rest were female, most of whom had more interests in subjects related to language, liberal arts or social studies. The students were all native speakers of

Mandarin Chinese and had been learning English for at least six years. However, most of them belonged to the lower or lower-intermediate level1, which did not match the level indicated by the report on the twelve-year compulsory education (Chang, 2013). The students had the motivation to learn English, but had little confidence and did not know how to learn English well. What’s worse, their vocabulary size was quite

1 Most of the students in the study obtained B or B+ on English in the Comprehensive Assessment

Program for Junior High School Students, the entrance exam of senior high schools in Taiwan. It categorized test-takers into three broad Bands – A, B, and C, with Band A and Band B further divided into three small levels – A++, A+, A, B++, B+, and B. The institution responsible for the exam, the Research Center for Psychological and Educational Testing [RCPET] (2014), reported that of all the test-takers in that year, 10.76% got B+ and 24.32% got B.

26

inadequate, which resulted in difficulty in reading and writing. This posed a great challenge for them to achieve their goals in the college entrance exam. Seeing this, the teacher-researcher decided to choose them as the participants of this experiment, hoping to increase their productive vocabulary size especially.

Instruments

Three sets of instruments were used in the study, including a list of target words, the writing prompt for pre- and post-tests, and the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale. First, the target words constituted the foci of the study. The number of words was 53 words for productive purpose. To select the target words, the teacher-researcher adopted four guiding principles. First, these words were related to the topic of the prompt to

facilitate the students' writing performance. Second, all the target words came from the 4,000 wordlist issued by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan (Jeng, Chang, Cheng, & Ku., 2002), an important reference for textbook writers. Next, the wordlist consisted of a balanced distribution among different word parts, with verbs and nouns taking up nearly four-fifths, and adjectives taking up the remaining one-fifth (Hardie, 2007). Lastly, there were old words and new words selected to see the effects of the teaching method on different types of words. Of all the 53 words, 40 words had been learned in the previous textbook volumes, while the remaining 13 words had never been learned from the textbooks prior to Book 3, the volume to be used in the coming semester. Table 2 listed all the target words, which were grouped following the

27 Table 22 Target Words Groups Words G1 (6 words)

personal (B1-U1), community (B1-U2), device (B1-U3), necessity (B1-U3), control (B1-U3), influence (B1-U4) G2

(6 words)

apply (B1-U4), environment (B1-U4), describe (B1-U4), express (B1-U6), negative (B1-U6), content (B1-U7) G3

(6 words)

situation (B1-U7), event (B1-U9), responsible (B1-U10), focus (B1-U11), attitude (B1-U11), product (B1-U11) G4

(5 words)

relax (B1-U11), benefit (B1-U12), social (B1-U12), access (B2-U2), message (B2-U2)

G5 (5 words)

contact (B2-U2), download (B2-U2), technology (B2-U2), connect (B2-U4), information (B2-U4)

G6 (5 words)

surf (B2-U5), clip (B2-U5), essential (B2-U6), factor (B2-U6), issue (B2-U6)

G7 (5 words)

major (B2-U6), privacy (B2-U7), incident (B2-U8), convey (B2-U10), regular (B2-U10)

G8 (5 words)

opinion (B2-U10), visual (B2-U11), abuse (B3-U2), account (B3-U2), bully (B3-U2)

G9 (5 words)

comment (B3-U2), delete (B3-U2), efficient (B3-U2), file (B3-U2), site (B3-U2)

G10 (5 words)

remark (B3-U2), switch (B3-U2), violate (B3-U2), virtual (B3-U2), identity (B3-U7),

The second instrument was a writing prompt used in the study to elicit the students’ written products. The narrative genre was used because narration has been reported to be easier for the students compared with other genre types (Way, Joiner, & Seaman, 2000). The topic of the prompt was related to the students’ lives, because familiarity with the topic was an important factor for the students to generate ideas for writing (Kiuhara, Graham, & Hawken, 2009). For this reason, the teacher-researcher designed a prompt that required the students to write a narration on the most

2 In Table 2, "B" means the textbooks where the words appear, while "U" signifies the units the words

appeared in each textbook volume. The 13 new words that the students have never learned before are in boldface.

28

impressive Internet incident for more than one hundred words. The requirement of the word number was necessary for providing sufficient information for further textual analysis. The prompt and the instructions were written in the students’ native language so that they can better understand the requirements.

Thirdly, the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale (the VKS) was used to evaluate the students’ level of vocabulary knowledge before and after the experiment. Though word selection was based on the students’ textbooks, an objective measure was needed to see how the students had learned the target words. Another reason for choosing the VKS lied in the fact that it had been widely used in previous literature to investigate the depth of word knowledge (Bruton, 2009; Paribakht & Wesche, 1993; Read, 2000; Wesche & Paribakht, 1996). The five descriptors of the VKS as given in Figure 1 were quite applicable and easy to operate. More importantly, they yielded quantitative data, which served as a basis for comparison of word knowledge before and after the experiment. To efficiently investigate the students’ knowledge, the teacher-researcher translated the five descriptors into the students’ native language and instructed the students with an example. Please refer to APPENDIX I for the first page of the VKS, which included the example given to the students.

Procedures

The current study took 14 weeks. The first week was the preparatory week, in which the teacher-researcher gathered information about the students’ background. Then, the teacher-researcher gave a brief introduction to English writing and

conducted the pre-test on the students. In the following 12 weeks, the experiment was carried out to teach the students the target words by exposing them to the words repeatedly through various ways. After the experiment, the post-test was administered to evaluate the results in the 14th week.

29

1. Pre-Test (Week 1)

Before the students did the pre-test, the teacher-researcher briefly introduced the students to the basic knowledge of English writing, especially description and

narration. Since the students’ previous writing experiences varied, such instruction was needed to assist and familiarize the students with writing conventions and mechanisms. After the introduction, the students were told that the writing exam would be included as one of their final grades. The purpose was to motivate the students to pay attention in class and write as best as they can. The introduction also included a brainstorming activity to help the students generate more ideas for their writing (see APPENDIX A for more details).

In the process of writing, no other aid was given to the students, since they have received instruction in the previous classes, and the Chinese prompt is not difficult for them to understand (see APPENDIX B). They were required to write a paragraph of at least one hundred words in fifty minutes. After that, the teacher-researcher collected the writings the writing prompt.

On the next day, the teacher-researcher gave the VKS to the students as another test for their beginning proficiency level. They had fifty minutes to finish the VKS (see APPENDIX C for the explanations to the students). The VKS was administered after the writing task to avoid possible learning effects.

2. The Experiment (Week 2 – Week 13)

During the 12-week experiment, there were ten minutes in every class period devoted to introducing and familiarizing the students with the target words. As there were six English classes in a week, there were totally 60 minutes for the teaching experiment each week. To see the effects of such teaching, the experiment lasted for three months. Added together, the time of the treatment was 720 minutes in total.

30

word learning as discussed in the literature review and was incorporated with the ongoing lesson. Activities and techniques introduced in previous literature (e.g. Nation, 2001; Ur, 2012) were also employed to achieve the purpose. These activities were further categorized according to their functions – to present, to practice, and to produce. The activities for presenting words aimed at drawing the students’ attention and activating their schemata. The practicing activities aimed to create meaningful contexts of learning the words. Lastly, the activities for producing words required the students to practice using words in various tasks. Listed below were the descriptions of the activities used for productive use of the target words.

1) The teacher presented the new words through:

a. Attention-drawing techniques – highlighting, visual or multimodal aids; b. Rich instruction – giving rich instruction on the words before reading a text; 2) The teacher guided students to practice the target words through:

a. Peer teaching – students teaching their lists of words to others; b. Glossing – students making their own glossary;

c. Partial dictation – students listening to the target words and filling in the blanks; 3) The teacher guided students to produce the target words through:

a. Sentence making – using the word to make a sentence;

b. translation – translating the word and making a sentence with it.

All the target words went through the phases of presentation, practice, and production stage. In each stage, the target words were reviewed twice. In total, the target words were repeated for six times through different activities during the 12-week experiment. The repetition followed the spiral curriculum design principle to create optimal opportunities for the students to review and use the words. In addition, reviewing all the target words over an extended period of time provided a great opportunity for the students to have constant exposure to the words through spaced

31

repetition, which helped memorize the words better (Nation, 2001). Below was a detailed description of the rationale for the design, the materials for each stage, and the instructional processes.

The Presentation Stage (Week 2 – Week 5). The Presentation stage went from

week 2 to week 5. The major purpose of the stage was to provide the students with multiple exposure contexts of the target words. Through repetitive encountering with the words, the students were more likely to memorize them. In addition, seeing words in different contexts provided the students with more instruction to the target

vocabulary, which can increase the chances of picking up the words. Particularly, the first presentation aimed at familiarizing the students with the target words, while the second round focused on providing more information concerning word usage, such as derivations, useful phrases, and collocations.

Because of the specific aims, the teaching materials varied in the two

presentation stage. For the first presentation, the original example sentences of the students’ textbooks were used with the keywords boldfaced to raise the students’ awareness, a method inspired by the input enhancement hypothesis (Smith, 1993). Such teaching materials helped the students repeat what they had learned and thus made it easier for them to recall the words. In addition, the boldface was used to draw the students’ attention to the highlighted parts and raise the awareness. One instance of the first round was listed as follows: “The story is based on Monica’s personal experience. She wrote down all of the interesting things she saw during her trip to Osaka” (please refer to APPENDIX D for more details).

For the second presentation, example sentences from the textbooks still remained the major sources. If suitable sentences could not be found from the textbooks,

renowned and widely-used online dictionaries, such as the Free Dictionary and Collins Dictionary, were used as the sources of the example sentences. Different from

32

the first presentation, the derivations or collocations of the target words became the foci in the example sentences. One such example from the second round to teach the derivation of “influence” was listed here: “An influential leader can change how people think and also lead them through difficult times” (please refer to APPENDIX E for more details).

The instruction for the first and second presentation followed roughly the same procedures. First, the teacher-researcher and the students took turns reading the example sentences containing the target words. Then, the teacher-researcher elicited the meanings of the boldfaced words from the students by asking them to give the Chinese translation. If they had a hard time doing this, they would be guided to guess the words from contextual clues. This activity was followed by the explanation of the important points and the parts which the students struggled with as shown in the pre-test. Still, the emphasis was put on the target words and its meaning in contexts. As for the second presentation, the teaching process included more guidance since it involved more difficult derivative forms. After the students understood the meanings of the derived words, they were asked to recall the original forms they had learned in the first presentation. During the presentation stage (Week 2 – Week 5), the target words were taught following the sequence from G1 to G10, which was the order of the students’ sequence of learning. All the target words were taught at this stage. The whole presentation stage took 240 minutes, ten minutes for each vocabulary lesson in 24 classes.

The Practice Stage (Week 6 – Week 9). The Practice stage started from week 6

and ended in week 9. This stage was intended to enhance the students’ knowledge of the target words through different modes. Different from the previous stage, the practice stage involved the students more in the activities, which was necessary for memorizing the words according to the Involvement Load Hypothesis (Hulstijn &

33

Laufer, 2001). To achieve the goal, the two rounds of practice were designed to provide adequate scaffolding for the production stage. The first round of practice focused on the spoken form and sound-meaning link of the vocabulary, while the second put emphasis on the students' active participation in learning the words through activities like peer teaching.

With the goal in mind, the practice stage was designed in a more challenging way. For the first round, the example sentences or passages were retrieved from the reading section of the textbook. This was not only a repetition but also a way to review words in different contexts. Different from Presentation, the first practice round required the students to do a partial dictation in each class period. The activity lasted for two weeks. With six classes in one week, there were 12 times for the students to do the partial dictation. In each lesson, there were several sentences, and the total number of words for each was around one hundred words. The students received a piece of paper with the example sentences or passages. They were required to listen to the teacher-researcher and fill in the blanks, which consisted of the key words, collocations, and sometimes derivatives of the target words. The sentences or passages were read twice. For the first time, the teacher-researcher read the sentences or passages as a whole and paused to wait for the students to fill in the blanks. For the second time, only the sentences that contained blanks were repeated. After the

listening, the students had a chance to look at the passages again and then gave the Chinese translation for the target words in the brackets below. Then, the teacher-researcher checked answers with them. The students reviewed the words in different contexts and deepened their word knowledge through listening. In addition, the act of providing glossing could involve the students in actively recalling the words (please refer to APPENDIX F for more detail). The rationale behind such design was to make the activity progressively challenging and give the students more chances to listen to

34

the target words and how they appeared in a larger context. For the first Practice, instead of following the sequence of G1 to G10, the target words were organized around the reading passages in a theme-based fashion.

For the second Practice, the students were required to form a group of four to five people and take turns teaching their classmates the target words. Each group got six to seven words and prepared in advance. Then, they were scheduled to give a presentation of five minutes about their list of words. There were three requirements for their teaching. First, they had to think of effective and creative ways to teach their words to the class. Then, everyone in the group had to speak in front of the class. Also, before the explanation, the group in charge needed to write down the words on the blackboard. To motivate the students, the teacher-researcher graded them

according to their participation and performance on stage. Bonus would be given to them if the teaching group or other students can ask questions regarding the words. Like the presentation stage, the practice stage took 240 minutes, ten minutes for each vocabulary lesson in 24 classes (please refer to APPENDIX G for more detail).

The Production Stage (Week 10 – Week 13). The last stage went from week 10 to

week 13. The major purpose of the Production stage was to create chances for the students to use the target words, since literature has pointed out that pushed output (Swain, 1985, 1995) and the very act of using words contributed to productive word learning (Fan, 2000; Lee & Muncie, 2006). The two rounds of the Production stage were designed to guide the students to use the words in sentence-making tasks. For the first round, the major focus was making a sentence with the target words. A little more difficult than the first round, the second round required the students to first translate a target word from Mandarin Chinese to English, and then make a sentence with the word.

35

task. The target words and collocations of these words were written on separate pieces of paper. The students came to the teacher to draw the wordlist their group would be in charge of for the class period. Then, the students worked with their group members to come up with a sentence for each word on the list which contained at least ten words. Then, they wrote the sentences they had created on the blackboard. During the process, the teacher-researcher assisted them in solving grammatical problems, when the students figured out the usages of the target words on their own. This move was to push the students to actively recall the words or to make them look up the words themselves, so that they could remember the words better through more involvement (Hulstijn & Laufer, 2001; Sokmen, 1997). After that, the teacher-researcher checked the sentences on the blackboard with the class. All the mistakes were corrected, but the emphasis was on the target words and the collocations. To motivate the students, the class voted on the best sentence of the day, and bonus was given to the group that produced the sentence.

The second Production stage required the students to use the target words through two tasks – Chinese-English translation and sentence construction of the words. First, the students came to draw the words for their group. However, this time, they would get a Chinese equivalent of the target words. Since a word may have various translations, only the core meaning was provided. The students, working with their groups, had to first translate the word and make a sentence with it. The rest instructional processes went just like the first stage. In the second Production, the translation task made it more challenging and motivating than the first Production. Also, it better evaluated whether the students could actively recall the target words and use them accurately, which was a demonstration of deeper word knowledge (Fan, 2000; Laufer, 1998) (please refer to APPENDIX H for the examples of the