Understanding Faculty Needs:

A Case Study at the University of Toledo

學科教授對圖書館服務之需求:

多麗都大學實例

Julia A. Martin

Business & Economics Librarian/Assistant Professor of Library Administration,

University of Toledo, U.S.A.

E-mail:julia.martin@utoledo.edu

Keywords(關鍵詞)

:

Subject Librarians(學科館員); Subject Specialists(主題專家); Liaison

Librarians(院系聯絡館員); Collection Development(館藏發展);

Surveys(問卷調查); Information Seeking Strategies(資訊搜尋策略);

Information Process Behavior(資訊處理行為)

【Abstract】

The paper explores how faculty need and

use the library. It reviewed literature on the

roles of subject librarians and the advantages

for faculty and libraries. It summarized key

strategies for subject liaison librarians to

de-velop relationships with faculty and the use of

surveys to explore faculty needs. The paper

also included a survey administered to the

business, engineering, and education faculty at

The University of Toledo in 2006-07 to help

subject librarians better understand their clients.

The University of Toledo survey focused on

faculty perception of library collection

devel-opment and library services, and examined

faculty's research needs and their patterns of

using library resources and services.

本 文 探 討 學 科 教 授 對 圖 書 館 的 需 求 和 使

用。它對學科館員對提供專業學科服務的優勢

和對圖書館服務所起的角色作用作了文獻探

討,並概括了建立和院系教授聯繫的主要策略

和使用問卷調查來瞭解他們的需求。本文包括

2006-07 年度對多麗都大學商學院、工程學院

和教育學院教授的問卷調查,發現教授對資訊

檢索和資訊處理的行為理念和使用圖書館的

模式。問卷注重教授研究興趣和資訊搜尋策略

與圖書館服務的關係,從而使學科館員更充分

瞭解他們學術研究的需求。

Introduction

The faculty survey began with a desire to better un-derstand faculty needs so that subject librarians could better serve them. Subject librarians are tasked with helping the faculty and students of specific colleges or departments. Many librarians focus their efforts on serving students rather than faculty and The University

of Toledo (UT) is no exception. However, a recent merger, a new university mission statement, and a new strategic plan demonstrated a significant increase in the university’s research endeavors. In light of these changes, several subject librarians at UT felt a need to reassess services to faculty.

First, the literature was searched to better understand the roles of subject librarians in serving faculty. The literature revealed not only the roles of subject librari-ans, but strategies for developing closer relationships and many advantages for both the library and faculty members.

Second, the literature was searched to discover the needs of faculty. While some information was found on reading habits and faculty’s desire for more com-prehensive library collections, an incomplete picture was formed. At UT, a LibQUAL+ survey had previ-ously been conducted. However, its response rate was low with very few faculty members responding. UT’s business librarian, with the encouragement of the College of Business Administration’s Library Com-mittee, decided it might be helpful to conduct a survey directly aimed at faculty. Survey questions were generated from other surveys and from a desire to un-derstand usage of specific titles and services offered at UT. Survey results provided insight into how UT faculty view and use research materials.

This paper is based on a presentation given at the Chinese American Librarians Association's 21st Cen-tury Librarian Seminar in Wuhan, China in October 2008.

Literature Review

The Roles of Subject Librarians

The roles of subject specialists vary, but typically encompass six responsibilities: specialist knowledge, reference services, library instruction, liaison activities, collection development, and research assistance.

To provide a foundation for specialist knowledge, a degree, particularly a graduate degree, in a relevant dis-cipline is often preferred by libraries. However, many specialists have other relevant experience or fall into the specialty because of the unfulfilled needs of their institu-tions. Subject librarians often provide in-person, email, chat, IM, and phone reference services at a reference desk in a specialty library or a main library. Subject librarians are responsible for working closely with a subset of the university population, usually a college or a department. Library instruction, particularly in the subject specialty, is another common responsibility. Subject librarians may incorporate information literacy guidelines into instruction and reference by emphasizing the need for information, how to find it, how to evaluate it, and how to use it. In many cases, subject librarians put great emphasis on developing and maintaining rela-tionships with faculty in their assigned colleges and departments. Another important responsibility for subject librarians is collection development. The American Library Association's (ALA) Reference and User Services Association has published "Guidelines for Liaison Work in Managing Collections and Services" (2001). Collection development includes not only the selection and de-selection of books, but important choices regarding dropping serials or moving them to electronic formats and the acquisition of databases to support the curriculum and research. In-depth research assistance for faculty and graduate students, and even undergraduates and community members, is another valuable service provided by subject librarians. Though not all subject librarians will serve all these roles, they will serve many of them (Cotta-Schonberg, 2007; Dyson, 2007; Gaston, 2001; Hardy & Corrall, 2007; Wood, 2005; Yang, 2000). The Association of Research Libraries (ARL) published a Liaison Services SPEC Kit (Logue, Ballestro, Imre, & Arendt, 2007) which offers examples of roles and responsibilities, po-sition descriptions, training materials, and service de-scriptions for liaisons, who are often subject specialists.

The advantages for faculty, students, and librarians are many. Advantages for faculty include a forum for communicating their needs and one identifiable and responsible person. Both faculty and students benefit from targeted collections and subject specific library instruction. The librarian's deep subject knowledge and access to other subject specialists assist faculty and graduate students in advanced research requests.

A subject specialist organization of the reference department has the potential to create many advantages for librarians, particularly a better knowledge of their customers. Close faculty-librarian relationships often lead to a natural forum for communicating both faculty needs and library policies, services, and resources. The library and the librarian increase their visibility and cultivate opportunities for creating customer par-ticipation and buy-in and, possibly, advocacy. Other possibilities such as team teaching and collaboration in research and writing may develop. Advantages for the library go far beyond the development of focused paper and electronic collections.

Many strategies may help a subject librarian create and maintain relationships with faculty. Subject spe-cialists in various disciplines have shared their strategies and experiences, including a Rutgers task force (Glynn & Wu, 2003); Frada Mozenter, Bridgette Sanders, and Jeanie M. Welch (2000); Carla Hendrix (1999); Scott Stebelman, Jack Siggins, David Nutty, and Caroline Long (1999); Jessica Albano (2005); Stephan Macaluso and Brabara Whitney Petruzzelli (2005); a group of new subject liaisons (Stoddart, Bryant, Baker, Lee, & Spencer, 2006); an ALA Business Reference and Ser-vices Section meeting (2001); Michele R. Tennant, Tara Tobin Cataldo, Pamela Sherwill-Navarro, and Rae Je-sano (1994); Sandra Beehler (2006); and Matthew Wright (2007). Perhaps the most effective is to focus on key classes, including library instruction classes and research classes. Instructors of library instruction classes are often able to find the time to fit in a trip to the library. Targeting library instruction classes has the

advantage of reaching students at the beginning of their academic careers. One disadvantage to this approach is that the students usually do not have an assignment on which to focus their attention during the session. However, an emphasis on the library as a place to study, use computers, and ask questions is a good first step. Research classes are a natural environment for library instruction and developing ongoing relationships with faculty. Students focus on the content of the session because they have a defined outcome that requires li-brary research. One disadvantage is that research classes are often scheduled at the end of students' uni-versity careers instead of towards the beginning. If the librarian can reach all sections of a required class in the college or department, maximum coverage for amount of effort can be achieved.

Other strategies for developing relationships with fac-ulty include targeting new facfac-ulty, who tend to be more open to new strategies, attending department and college meetings, sometimes to present, but always to listen, attending the college's public lectures, and distributing a newsletter, email update, or blog. A library pathfinder or workshop on a new or changed product might be welcomed. Browsing faculty websites for research interests and browsing offered classes and their text-books and syllabi offers information regarding the inter-ests of faculty. A survey of library users, whether Lib-QUAL+ or a homegrown survey, may prove fruitful. Another way to experience the college and create seren-dipitous meetings is to conduct office hours in a com-puter lab or busy corridor, which the University of Al-berta's Cameron Science & Technology Library (Reich-ardt & Kowalyk, 2004) and the University of Missis-sippi's library (Stephan, 2007) successfully implemented. Though students may be the primary target, faculty often stop by to chat. Some universities (Bartnik, 2007; Freiburger & Kramer, 2009; Johnson & Alexander, 2007) are experimenting with embedded librarians or field li-brarians, where the librarian's office is moved from the library to the college or department. The collection

re-mains in the library and the basic job duties do not change. However, the librarian is more accessible and becomes a member of the college or department community.

Much of the literature on liaison librarians and sub-ject specialists focus on serving students. Even the development of better relationships with faculty often seems to have the end goal of reaching students, with faculty members as intermediaries. In the survey conducted at UT, faculty research needs rather than teaching needs are addressed.

Surveys of Faculty to Better

Un-derstand Their Needs

Today's academic libraries suffer from a lack of measures of success. The traditional measures of collections, expenditures, and staffing no longer ade-quately describe or measure most libraries. Many have proposed new areas of measurement and these measurements have some models, but data can be dif-ficult to obtain and are certainly not standard across libraries. Sharon Weiner (2005) showed that new measures of service, including number of reference transactions, number of instructional presentations, and number of attendees at group presentations positively correlated with The Association of Research Libraries traditional measures of number of volumes owned, number of journal subscriptions, number of employees, and budget. Kathryn Deiss (1999) proposed measur-ing organizational capacity by measurmeasur-ing human re-sources, individual and group performance, creativity and innovation, and organizational capacity. Even something as basic as measuring the use of electronic resources, on which libraries increasingly spend a lar-ger proportion of their collections budgets, is not yet consistently feasible, though many groups are working on the technical aspects of this measurement (Bernon, 2008; Pesch, 2008; Tijerina & King, 2008).

Libraries have turned to business practices for measures of quality and satisfaction. Shi and Levy (2005) discuss the evolution of library surveys. Many

libraries use LibQUAL+, a survey designed to measure affect of service, library as place, and collections and access. LibQUAL+ is a modified form of SERVQUAL, a tool businesses use to measure service quality. However, libraries suffer from low response rates to LibQUAL+ surveys as well as debate over some of the survey items and the difficulty of separat-ing tangibles and intangibles. Some researchers have concentrated on specific populations. Kayongo and Jones (2008) found that faculty at ARL libraries were consistently dissatisfied with collections and access to them. They found strong correlations between fac-ulty scores on the LibQUAL+ survey and ARL statis-tics for total materials expenditures.

Librarians and their professional organizations have also developed surveys to better understand their cus-tomers. In 2002 The Council on Library and Infor-mation Resources (CLIR) published a report that ex-plored the changing usage patterns caused by the growing web environment (Friedlander). Faculty reported spending an average of 15.79 hours a week obtaining, reviewing, and analyzing information. At that time 67.8% of faculty still relied exclusively on print resources. However, 25.6% said they needed more online journals. More recently, King, Tenopir, Choemprayong, and Wu (2009) found that faculty spend about 132 hours per year (2.5 hours per week) reading scholarly articles. In addition, they found that libraries provide 52% of the articles read. Fac-ulty have also been surveyed regarding their awareness of library databases (Laribee & Lorber, 1994; Renwick, 2005; Weingart & Anderson, 2000). The majority of researchers found that many faculty lack awareness of library resources and recommended the need to pro-mote library databases and other resources.

University of Toledo Faculty

Survey

The UT faculty survey was designed to capture in-formation regarding research activities rather than

teaching activities. Ideas were generated from Lib-QUAL+ questionnaires and other published surveys (Friedlander, 2002; Laribee & Lorber, 1994; Renwick, 2005; Thomson-Roos, 2005; Weingart & Anderson, 2000). The subject librarians hoped to gain insight into how the library fit into faculty research practices. During the 2006-2007 academic year, full-time faculty in the Colleges of Business Administration, Engineer-ing, and Education at The University of Toledo were surveyed. College of Business Administration faculty were surveyed first in Fall 2006. In Spring 2007 the survey instrument was modified slightly to survey faculty in the Colleges of Engineering and Education. All faculty members were mailed a survey with a brief note of thanks and a mint. Two follow-up emails were sent. Fifty-eight faculty members out of a population of 225 participated, with a 26% response rate. Though a 26% response rate was less than hoped for, the response was sufficient to form an im-pression of faculty characteristics. Faculty members

were asked a series of demographic questions and questions about their satisfaction level with library resources and services, their information search be-haviors, and library usage patterns, some of which are summarized below.

Results

Demographics

Of the participating faculty, 25 were from the Col-lege of Business Administration, 15 from the ColCol-lege of Education, and 18 from the College of Engineering (Table 1). The average length of employment at UT was 12 years and the average length of time conduct-ing scholarly research was 16 years. More partici-pants were male (42) than female (16). The majority of respondents were tenured faculty (35), followed by tenure track faculty (14), and visiting faculty or lectur-ers (9). The average number of peer reviewed journal articles published per person was 18 (Table 2).

Table 1 Respondents by College

College Respondents Population Response Rate

Business 25 78 32%

Education 15 59 25%

Engineering 18 88 20%

Total 58 225 26%

Table 2 Respondents' Demographic Profile

Gender Tenure Status Years Researching

Male Female Tenured Tenure

Track Visiting/ Lecturer at UT Total Peer Reviewed Articles 42 16 35 14 9 12 16 18

Faculty Satisfaction Level with

Li-brary Resources and Services

Faculty were asked a series of questions about their beliefs regarding research material availability and whom they believed held the responsibility for acquir-ing them. A seven point Likert scale was used with 1

being strongly disagree, 4 being neither agree nor dis-agree, and 7 being strongly agree. Faculty were asked to rate their beliefs regarding library resource availability and effect on research (Table 3). Ratings for each question were averaged and displayed here from highest (agree) to lowest (disagree). Responses

indicate that library resources do positively support research, but that faculty desire further support.

Fur-thermore, responses indicate that library resources do not play a strong role in determining research pursuits.

Table 3 Resource Availability's Effect on Research

Survey Question Ave. Rating

The availability of research materials and resources at UT libraries positively impact my research productivity.

5.34 My ability to meet my department's research goals is facilitated by the availability of library

re-sources at UT.

4.65 I am happy with the research materials and resources available to me through UT Libraries. 4.62 UT Libraries current resources do not adequately support faculty research activity. 4.31 I feel a sense of frustration with the availability of research materials available through UT Libraries. 3.52 Completing research projects is difficult given the library resources available at UT. 3.35 My department's research expectations are difficult to achieve with the current level of research

ma-terials and resources available through UT Libraries.

3.35 The type of research activities I undertake is partly determined by the library resources available at

UT.

3.15

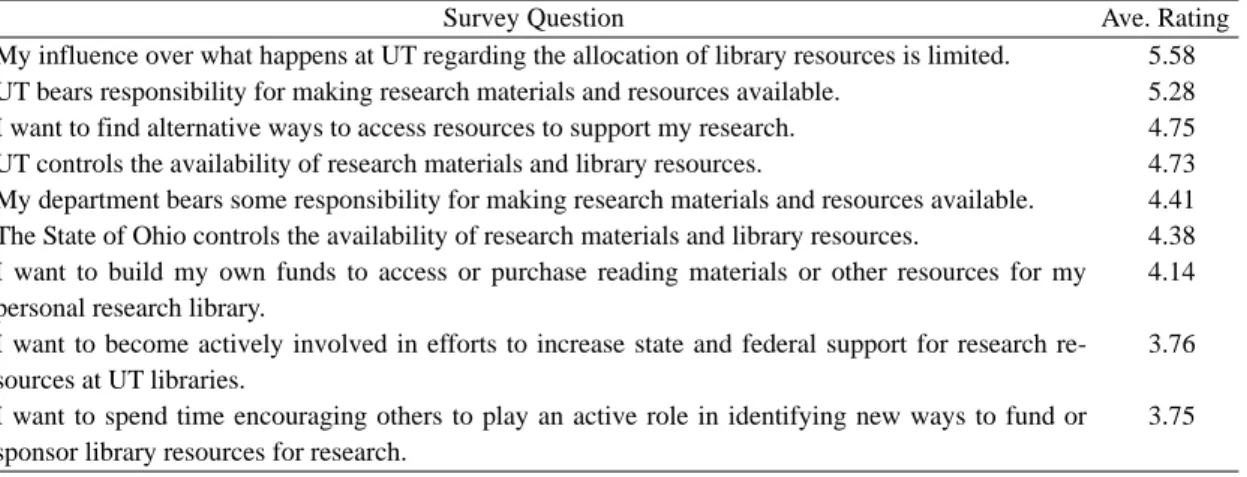

Faculty were also asked who bears the responsibility of providing research materials (Table 4). Ratings for each question were averaged and displayed here from highest (agree) to lowest (disagree). Responses

indi-cate that faculty believe the university bears the high-est level of responsibility for providing research mate-rials and that individual researchers bear the lowest level of responsibility.

Table 4 Responsibility for Access to Research Materials

Survey Question Ave. Rating

My influence over what happens at UT regarding the allocation of library resources is limited. 5.58 UT bears responsibility for making research materials and resources available. 5.28 I want to find alternative ways to access resources to support my research. 4.75 UT controls the availability of research materials and library resources. 4.73 My department bears some responsibility for making research materials and resources available. 4.41 The State of Ohio controls the availability of research materials and library resources. 4.38 I want to build my own funds to access or purchase reading materials or other resources for my

personal research library.

4.14 I want to become actively involved in efforts to increase state and federal support for research

re-sources at UT libraries.

3.76 I want to spend time encouraging others to play an active role in identifying new ways to fund or

sponsor library resources for research.

3.75

Faculty Information Search

Be-haviors

Faculty members were asked about their behavior when conducting research. Table 5 shows the

re-sources faculty used when not using the library. A seven point Likert scale was used with 1 being never happens and 7 being frequently happens. Ratings for each question were averaged and displayed here from

highest (frequently happens) to lowest (never happens). It was no surprise that Internet usage dominated re-search behavior. Faculty were more likely to

pur-chase their own materials than to visit another library, once a very common and necessary activity.

Table 5 Behavior When Conducting Research

Survey Question Ave. Rating

Search for free resources on the Internet. 5.80

Utilize public resources and databases to access research materials (excluding UT libraries and OhioLINK).

5.68 Purchase journals or other materials from my personal funds. 4.59 Borrow research materials or books from research colleagues. 3.89 Visit other universities to utilize their research resources and facilities. 3.36 Seek outside funding to pay for research materials otherwise unavailable through UT libraries. 2.91 Actively participate in a repository or online working papers community offered by other academic

institutions (e.g. SSRN).

2.89 Share the cost of purchasing research materials with research colleagues. 2.64

Faculty Information Usage

Pat-terns

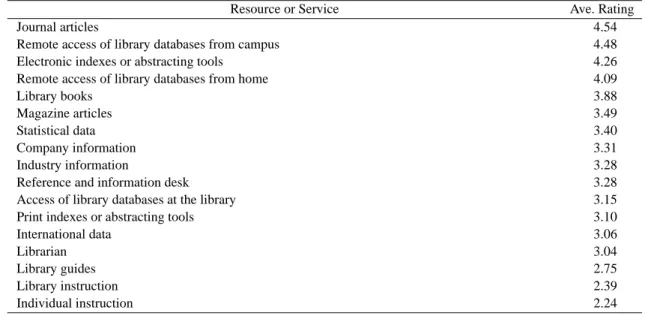

Faculty were given a list of 17 library material types and services and asked which were used in their uni-versity work (Table 6). A five point Likert scale was used with 1 being never use, 2 rarely use, 3 not sure, 4 occasionally use, and 5 being frequently use. Ratings for each question were averaged and displayed here

from highest (frequently use) to lowest (never use). Results indicate that faculty use journals and journal databases much more than any other type of library material or service. A lack of the use of librarians, library guides, library instruction, and individual in-struction demonstrate their independent research be-havior.

Table 6 Use of Library Resources & Services

Resource or Service Ave. Rating

Journal articles 4.54

Remote access of library databases from campus 4.48

Electronic indexes or abstracting tools 4.26

Remote access of library databases from home 4.09

Library books 3.88

Magazine articles 3.49

Statistical data 3.40

Company information 3.31

Industry information 3.28

Reference and information desk 3.28

Access of library databases at the library 3.15

Print indexes or abstracting tools 3.10

International data 3.06

Librarian 3.04

Library guides 2.75

Library instruction 2.39

Discussion

This study attempted to confirm which library re-sources and services were being used and to delve deeper into the relationship between faculty research and the library. Surveys administered to the business, engineering, and education faculty at The University of Toledo in 2006-07 have shown that faculty value li-brary collections and desire greater support of research materials. They believe the university should bear primary responsibility for allocating money for re-search materials and feel that they have little influence over allocation decisions and have little desire to ad-vocate for increased materials allocations. Faculty frequently use the Internet for research and rarely go to library buildings. Of the many resources the library provides, they most value journal literature and the electronic indexes to access it. Several studies sup-port these conclusions, including a collaborative col-lection building agreement for the secol-lection and fund-ing of electronic databases between business faculty and the business library at Pennsylvania State Univer-sity, which emphasized the importance of electronic databases to faculty (White, 2004). Tucker, Bullian, and Torrence (2003) presented a model for fac-ulty/library liaison collaborative collection develop-ment. Michael Stoller (2005), a New York University collections librarian, theorized that the subject specialist librarian offers the best method for communicating with faculty and developing collections. Additionally, Thomson-Roos (2005) found that collections were ex-tremely important to business and economics faculty.

Though it would be a very broad assumption to think that The University of Toledo's business, education, and engineering faculty represent all UT faculty or all pro-fessional faculty, a glimpse of their beliefs, behavior, and library usage may help subject librarians understand the nature of faculty and their library needs. The role of the library that faculty seem to value most is collection development, implying that, from their viewpoint, it is

the most important role for the subject librarian. Whether purchasing new journals and databases, can-celing subscriptions, or answering research questions, knowing the needs and characteristics of the faculty assists subject librarians with their duties. While sub-ject librarians most highly value the provision of refer-ence and library instruction (McAbee & Graham, 2005), faculty most value the library collection. Subject li-brarians should be aware of faculty research needs even though, generally, much more time is spent assisting students and most faculty do not step foot in the library building. Faculty beliefs, behavior, and usage patterns should drive collection development much more than any other library service for faculty.

Though change is slow, The UT Libraries have re-sponded to the needs of faculty. First, the desire for online journal access has resulted in far fewer print publications and more online only journal subscrip-tions. Second, The UT Libraries have formed a mar-keting committee to help with communication. Though the first initiatives of the committee focused on undergraduate students, the committee has also begun to consider faculty relations. A flashy email template has been designed for subject librarians and the library to use for communication. A series of “Connection Sessions” has also been planned to high-light services that faculty use for research such as EndNote and interlibrary loan.

Conclusion

This study’s goal was to discover how the library fits into faculty member’s research practices. It found that faculty do value library resources, but feel they have little influence over their selection. When choosing research projects, faculty members do not consider the availability of library materials to support their projects’ success. Of the many library resources and services, faculty primarily use online journals and indexes. Other information resources like books and statistics were also important. Services offered by

librarians such as reference, library guides, and in-struction are used much less than materials. The sur-vey results emphasized the importance faculty place on comprehensive collections and access to materials. When serving their patrons, subject librarians need to be aware faculty rely on librarians most for collection building, rather than any other service.

References

Albano, J. (2005). The must list. College & Research

Libraries News, 66(3), 203-228.

American Library Association, Reference and User Services Association, Business References and Ser-vices Section, Business Reference in Academic Li-braries Committee. (2001). Brainstorming ideas for

faculty liaison. Program conducted at the meeting of

the American Library Association Midwinter Meet-ing, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www. ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/sections/brass/brassproto ols/brasspres/miscellaneous/liaison.cfm

American Library Association, Reference and User Services Association, Collection Development and Evaluation Section, Liaison with Users Committee. (2001). Guidelines for liaison work in managing

collections and services. Retrieved from http://www.

lita.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/resources/guidelines/gui delinesliaison.cfm

Bartnik, L. (2007). The Embedded academic librarian: The Subject specialist moves into the discipline col-lege. Kentucky Libraries, 71(3), 4-9.

Beehler, S. A. (2006). Customizing faculty’s needs: Development of a liaison program (A subject librar-ian’s priority). Against the Grain, 18(1), 60-61. Bernon, J. (2008, December). Why and how to

meas-ure the use of electronic resources. Liber Quarterly:

The Journal of European Research Libraries, 18(3/4), 459-463.

Cotta-Schonberg, M. (2007). The Changing role of the subject specialist. Liber Quarterly: The Journal of

European Research Libraries, 17(1-4), 180-185.

Deiss, K. (1999). ARL new measures: Organizational

capacity white paper. Available from Association of

Research Libraries

Dyson, P. (2007). Subject liaison at Lincoln. SCONUL

Focus, 41, 12-15.

Freiburger, G., & Kramer, S. (2009). Embedded li-brarians: One library's model for decentralized ser-vice. Journal of the Medical Library Association,

97(2), 139-142.

Friedlander, A. (2002). Dimensions and use of the

scholarly information environment: Introduction to a data set assembled by the Digital Library Federa-tion and Outsell, Inc. (CLIR pub110). Retrieved

from Council on Library and Information Resources website: http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub110/ contents.html

Gaston, R. (2001). The Changing role of the subject librarian, with a particular focus on UK developments, examined through a review of the literature. The New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 7(1), 19-36.

Glynn, T., & Wu, C. (2003). New roles and opportunities for academic library liaisons: A Survey and recommen-dations. Reference Services Review, 31(2), 122-128. Hardy, G., & Corrall, S. (2007). Revisiting the subject

librarian: A Study of English, law and chemistry.

Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 39(2), 79-91.

Hendrix, C. A. (1999). Developing a liaison program in a new organizational structure - A work in pro-gress. The Reference Librarian, 32(67), 203-224. Johnson, B. L., & Alexander, L. A. (2007). In the field.

Library Journal, 132(2), 38-40.

Kayongo, J., & Jones, S. (2008). Faculty perception of information control using LibQUAL+ indicators.

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(2), 130-138.

King, D., Tenopir, C., Choemprayong, S., & Wu, L. (2009). Scholarly journal information-seeking and reading patterns of faculty at five US universities.

Learned Publishing, 22(2), 126-144.

Laribee, J., & Lorber, C. (1994). Electronic resources: Level of awareness and usage in a university library.

Logue, S., Ballestro, J., Imre, A., & Arendt, J. (2007).

Spec kit 301: Liaison services. Washington, D.C.:

Association of Research Libraries.

Macaluso, S. J., & Petruzzelli, B. W. (2005). The li-brary liaison toolkit: Learning to bridge the commu-nication gap. The Reference Librarian, 43(89), 163-177.

McAbee, S. L., & Graham, J. B. (2005). Expectations, realities, and perceptions of subject specialist li-brarians’ duties in medium-sized academic libraries.

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 31(1), 19-28.

Mozenter, F. L., Sanders, B. T., & Welch, J. M. (2000). Restructuring a liaison program in an academic library.

College and Research Libraries, 61(5), 432-440.

Pesch, O. (2008, February). ONIX, Z and JWP: Li-brary standards in a digital world. Serials Librarian,

53(4), 63-78.

Reichardt, R., & Kowalyk, J. (2004). Librarian on-site service at the University of Alberta: How the science and technology library took its information and ref-erence from the library to the faculty. Sci-Tech News,

58(3), 7-11.

Renwick, S. (2005). Knowledge and use of electronic information resources by medical sciences faculty at The University of the West Indies. Journal of the

Medical Library Association, 93(1), 21-31.

Shi, X., & Levy, S. (2005). A Theory-guided approach to library services assessment. College & Research

Libraries, 66(3), 266-277.

Stebelman, S., Siggins, J., Nutty, D., & Long, C. (1999). Improving library relations with the faculty and university administrators: The Role of the fac-ulty outreach librarian. College & Research

Librar-ies, 60(2), 121-130.

Stephan, E. (2007). Taking the library to the users: Satellite reference at the University of Mississippi.

College & Undergraduate Libraries, 14(4), 59-72.

Stoddart, R., Bryant, T., Baker, A., Lee, A., & Spencer, B. (2006). Perspectives on… Going boldly beyond the reference desk: Practical advice and learning plans for new reference librarians performing liaison

work. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(4), 419-427.

Stoller, M. (2005). Building library collections: It’s still about the user. Collection Building, 24(1), 4-8. Tennant, M. R., Cataldo, T. T., Sherwill-Navarro, P., &

Jesano, R. (2006). Evaluation of a liaison librarian program: Client and liaison perspectives. Journal of

the Medical Library Association, 94(4), 402-409.

Thomson-Roos, E. (2005). Paper number 1: User sat-isfaction, the main purpose of a library? Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 10(3), 22-31.

Tijerina, B., & King, D. (2008, November). What is the future of electronic resource management sys-tems? Journal of Electronic Resources

Librarian-ship, 20(3), 147-155.

Tucker, J. C., Bullian, J., & Torrence, M. C. (2003). Collaborate or Die! Collection development in to-day’s academic library. The Reference Librarian,

40(83), 219-236.

Weiner, S. (2005). Library quality and impact: Is there a relationship between new measures and traditional measures? Journal of Academic Librarianship, 31(5), 432-437.

Weingart, S., & Anderson, J. (2000). When questions are answers: Using a survey to achieve faculty awareness of the library's electronic resources.

Col-lege & Research Libraries, 61(2), 127-34.

White, G. W. (2004). Collaborative collection building of electronic resources: A Business faculty/librarian partnership. Collection Building, 23(4), 177-181. Wood, H. K. (2005). A Conversation with Anthony

Raymond. BF Bulletin, 129, 27-31.

Wright, M. J. (2007). Survey on law library liaison

services (R. Studwell (Ed.), Briefs in law

librarian-ship series vol. 14, AALL publication series no. 56, a publication of the Research Instruction and Reader Services SIS of the American Association of Law Libraries). Buffalo, NY: William S. Hein.

Yang, Z. (2000). University faculty's perception of a library liaison program: A Case study. Journal of

Appendix 1 FACULTY SURVEY

Please note that this version of the survey was given to business faculty. Education and engineering faculty re-ceived a version that reflected resources used in those disciplines.

DATE: November 21, 2006

TO: COBA Faculty

FROM: Sylvia Long-Tolbert, MIB Julia Martin, Carlson Library RE: Library Resources

We are conducting a user survey to better understand your preference and use of research resources funded through the University of Toledo Libraries. In light of budget cuts to library resources on campus, we hope to learn more about what impact library resources have on your research productivity. You also can take this opportunity to share your opinions about your service experience with the library as well as suggest those resources that would be useful to you in your job that are not currently available through the library.

Your participation in this survey involves completing the attached questionnaire. It takes approximately 15-20 min-utes of your time to do this. To ensure anonymity, you should return your completed survey via inter-office mail.

Please take a few minutes to complete the survey and return it to Julia Martin, MS#509 by December 8, 2006.

Questions may be directed to Julia Martin (julia.martin@utoledo.edu) or Sylvia Long-Tolbert (sylvia.long- tolbert@utoloedo.edu), the co-researchers of this project.

We greatly appreciate your feedback on this important research and resource issue.

Thank you!

NOTE: By completing this questionnaire you are giving your consent to participate in the project. Whether you participate or not will have no detrimental effect on your relationship with your department, Carlson Library or the University.

Your complete privacy is ensured as the information you supply will be evaluated in aggregate form rather than individually.

PLEASE TELL US A LITTLE ABOUT YOURSELF BEFORE YOU START THE SURVEY.

Gender: (___) M (___) F

Your tenure status: (___) Tenure-track (___) Tenured (___) Visiting / Lecturer

UT length of employment: _________ (years)

Length of time conducting scholarly research: _______ (years)

Research Activity

Number of published peer reviewed journal articles: _______

Number of published peer reviewed conference papers: _______

Date that you last submitted a manuscript to a peer-reviewed journal: (check only one option)

(______) (year submitted ) (___) None

Number of research projects currently underway: _______

Instructional Activity

Number of courses in which you require students to conduct research: _______

Number of courses which are being updated by you: _______

SECTION 1

For each statement below, please circle the rating that most closely reflects your response.

QUESTION 1a: Please rate your experiences with Carlson Library as reflected in the following statements.

Very Dissatisfied Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied Very Satisfied

My overall satisfaction with UT libraries 1….2….3….4….5….6….7

The relationship library employees have established with faculty 1….2….3….4….5….6….7 Resources available to faculty to support research activities 1….2….3….4….5….6….7 Resources available to faculty for teaching activities 1….2….3….4….5….6….7 Employee assistance with research requests 1….2….3….4….5….6….7 Employee assistance with teaching requests 1….2….3….4….5….6….7 Employee knowledge of research resources 1….2….3….4….5….6….7 Employee knowledge of teaching resources 1….2….3….4….5….6….7

QUESTION 1b: Please rate your personal satisfaction regarding different facets of your performance.

(Con-tinue using the satisfaction scale from the previous question.)

My overall satisfaction with my:

research productivity in the past 3 years.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

ability to get things done with the research resources available through UT libraries.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

professional progress as a researcher or scholar. 1….2….3….4….5….6….7

QUESTION 2: Complete the questions in this section IF you are or have been involved in conducting scholarly

research during your employment at UT.

Strongly Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Strongly agree

The availability of research materials and resources at UT libraries positively impacts my research productivity.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Completing research projects is difficult given the library re-sources available at UT.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

The type of research activities I undertake is partly determined by the library resources available at UT.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

My ability to meet my department’s research goals is facilitated by the availability of library resources at UT.

QUESTION 3: Rate the following statements in terms of how they relate to your beliefs about the current level

of library resources at the UT Libraries.

Not at all related to my beliefs

Highly related to my beliefs

The state of Ohio controls the availability of research materials and library resources.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

UT controls the availability of research materials and library re-sources.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

UT Libraries' current resource levels do not adequately support faculty research activity.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

My department’s research expectations are difficult to achieve with the current level of research materials and resources available through UT Libraries.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

UT bears the responsibility for making research materials and re-sources available.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

My department bears some responsibility for making research ma-terials and resources available.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

QUESTION 4: To what extent have you engaged in the following behaviors related to conducting research?

Never happens

Frequently Happens

Purchase journals or other materials from my personal funds. 1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Utilize public resources and databases to access research materials (excluding UT libraries and OhioLINK).

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Borrow research materials or books from research colleagues. 1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Visit other universities to utilize their research resources and facili-ties.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Seek outside funding to pay for research materials otherwise un-available through UT libraries.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Share the cost of purchasing research materials with research col-leagues.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

Actively participate in a repository or online working papers community offered by other academic institutions (e.g., SSRN).

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

QUESTION 5: State your level of agreement with the following statements

Strongly disagree Strongly agree

I have a great deal of control over how I get my research done. 1….2….3….4….5….6….7

My influence over what happens at UT regarding the allocation of library resources is limited.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

I am happy with the research materials and resources available to me through the UT libraries.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

I feel a sense of frustration with the availability of research materi-als available through the UT libraries.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

QUESTION 6: Rate how you think about your role as a member of the academic research community.

Strongly disagree Strongly agree

I want to find alternative ways to access resources to support my research.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

I want to build my own funds to access or purchase reading mate-rials or other resources for my personal research library.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

I want to become actively involved in efforts to increase state and federal support for research resources at UT libraries.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

I want to spend time encouraging others to play an active role in identifying new ways to fund or sponsor library resources for re-search.

1….2….3….4….5….6….7

SECTION 2: USE OF LIBRARY RESOURCES AND SERVICES

Which of the following resources or services do you use in your work at

the University of Toledo?

Indicate how frequently you use each resource by placing an ”X” in the appropriate column. Check only one col-umn.

* An example has been provided in the first row of the table below.

Type of Resource Never Use 1 Rar ely Use 2 Not Sur e 3 Occas ion ally Us e 4 F re que ntly Use 5

Disney Information Network

Journal articles Trade/Magazine articles Industry/Institutional information Government/Industry standards Statistical data International data Library books

Electronic indexes or abstracting tools Print indexes or abstracting tools

Group library instruction

Individual instruction

Library guides for subject resources

Librarian

Reference and information desks

Remote access of library databases from campus Remote access of library databases from home Access of library databases at the library

Other: ____________________________

In this section, please indicate your current use of the following electronic

resources that are available at the University of Toledo.

Indicate how frequently you use each resource by placing an ”X” in the appropriate column. Check only one column. * An example has been provided in the first row of the table below.

Database Title / Name Never Use 1 Rar ely Use 2 Not Sur e 3 Occas ion ally Us e 4 F re que ntly Use 5

Disney Information Network X

Business and Company Resource Center Business and Industry

Business Source Premier/Complete

EconLit Lexis/Nexis Academic NetLibrary (e-books) PAIS International PsycInfo Research Insight

Science Citation Index Social Sciences Citation Index

STAT-USA Thomson Research Other: _____________ Other: _____________ Other: _____________ Other: _____________

In this section, please indicate the likelihood of using the following

elec-tronic resources that are currently unavailable at the University of Toledo.

Indicate how frequently you would use each database by placing an ”X” in the appropriate column. Check only one column. Database Title / Name Highly Unlikely 1 Somewhat Unlikely 2 Not Sur e 3 Some what Like ly 4 Highly Like ly 5

ABI/Inform - provides abstracts of articles from interna-tional professional publications, academic journals, and trade magazines.

Choices - measures product and brand usage and media ex-posure and gives demographic characteristics and media us-age for users of specific products.

Factiva – indexes more than 8000 journals, newspapers, newswires, etc.

IBISWorld Industry Market Research – provides 680 indus-try market research reports at the 5-digit NAICS code level. Lexis/Nexis Company Dossier – provides basic and in-depth business information on more than 35 million global com-panies.

Lexis/Nexis Country Analysis – provides information on 190 countries and 157 industries.

Lexis/Nexis Statistical - provides access to statistics on a global basis.

Mintel Reports – covers US and international consumer markets with reports that analyze trends and market fore-casts on major players in an industry.

Value Line Investment Survey Online – one page reports on 1700 stocks.

World Bank e-Library - provides access to the World Bank's full-text collection of books, reports, and other documents.

In this section, please indicate your current use of the listed paper

re-sources that are available at the University of Toledo.

Indicate how frequently you use each resource by placing an ”X” in the appropriate column. Check only one col-umn. Database Title / Name Never Use 1 Rar ely Use 2 Don’t Know 3 Occas ion al Us e 4 F re que ntly Use 5

Best's Insurance Reports Life and Health D&B Consultants Directory

D&B Million Dollar Directory

Industrial Commodity Statistics Yearbook (U.N.)

JAI Press series (Advances in International Management, Advances in Strategic Management, etc.)

Mergent Manuals

National Accounts of OECD Countries

Nelson Information's Directory of Investment Research

Quality Control and Applied Statistics: the International Literature Digest

Standard and Poor's Industry Surveys

Ward's Business Directory of U.S. Private and Public Companies Other: _____________

Please discuss how you feel about the availability of library resources and

how technology affects your job.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR PARTICIPATION!

Please return the survey to Julia Martin, Carlson Library, MS#509.