國中教師對英文寫作教學看法之研究

全文

(2) Abstract. Writing instruction has been ignored in junior high school in Taiwan. Since teachers and schools have started to focus on communicative ability, should writing gain more attention in junior high schools? The pedagogical practices are assumed to be determined by teachers’ perceptions, beliefs and attitudes. Therefore, this study aims to examine teachers’ perceptions of English writing instruction, what factors they believe are crucial, and what measures are recommended to improve it. Besides, the study investigates teachers’ attitudes toward assessing students’ writing ability in the entrance exam. Finally, this study also intends to explore whether public and private school teachers view certain issues differently. Questionnaires are administered to 57 English teachers in Taichung City and are analyzed by frequencies and the independent t-test. The findings show that either teachers or schools downplay the importance of writing instruction. Teachers find factors affecting their teaching include: students’ language proficiency, students’ motivation, and time and efforts spent to review students’ writings. Also most teachers disapprove to include a writing test in the entrance exam. Possible measures to improve writing instruction are suggested: ability grouping, reducing the number of classes to teach, adopting more appropriate teaching materials, and avoiding a test-oriented curriculum.. i.

(3) 摘. 要. 寫作教學在國中的英語教育中往往被忽視,近幾年來學校和老師已經開始注 重學生的英語口語表達能力,那麼寫作的溝通能力是否也應該受到同等重視呢? 教學內容取決於教師本身的認知、信念和態度,因此本研究的目的在於了解教師 對於寫作教學的看法,影響寫作教學的因素,並且應如何改善寫作教學的品質。 此外,本研究亦調查英語教師是否贊成在國中基測中加考英文寫作。最後,本研 究分析公私立英語教師的看法是否具有明顯不同。以台中市六所公私立國中的英 語教師為研究對象,對 57 位英語教師進行問卷調查,進行次數分配表及 t test 統計分析。研究發現,學校和教師都忽略了寫作教學,而影響寫作教學的重要因 素包括:學生的語言程度、學習動機以及檢討學生的文章。改善寫作教學品質的 方法包括:能力分組、減少授課班級數、選用更合適的教材以及避免考試導向的 英語課程。而大部分的英語老師不贊成在基測中加考寫作。. ii.

(4) Acknowledgments. I would first like to express my heartfelt thanks and appreciation to my advisor, Professor Yang. His guidance and encouragement makes this thesis possible. I also appreciate Professor Tsai Ching-hua, who reviewed my questionnaires and gave me helpful comments. I wish to thank the following high schools in Taichung City for their assistance, especially their English teachers involved in my study. They are Hiang Shang Junior High School, Han Kou Junior High School, Chih Shan Junior High School, Shi Yuan Senior High School, Stella Matutina Girls’ High School, Shinmin High School, and I-Ning High School. Besides, personal thanks go to Hui-chen Fang, Chian-ru Lin, Wen-ting Lai, Ya-jiun Wang, who provided me with valuable comments. Jing-shiou Jian, Chang-yu Wu, Bernice Chiou, Pei-jin Wu, Ching-ping Chou also kindly offered a lot of help. I am also grateful for the technical help from my roommate, Shu-min Yang. Finally, also deserving of recognition for their perpetual moral support are my parents, Eric Lee and Shu-pi Chang. With their support, I was able to complete the thesis.. iii.

(5) Table of Contents PAGE CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................1 Background and Motivation ..........................................................................................1 Research Context about Writing Instruction..................................................................5 Statement of the Problem...............................................................................................7 Purpose of the Study ......................................................................................................7 Research Questions........................................................................................................8 Research Design.............................................................................................................8 Organization of the Thesis .............................................................................................9 Definition of Terms........................................................................................................9 CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................11 Writing Approach to Writing Instruction .....................................................................12 Grammar approach..............................................................................................13 Controlled Composition......................................................................................15 Contrastive Rhetoric ...........................................................................................16 Process Approaches ............................................................................................17 Writing Assessment......................................................................................................20 Traditional Assessment .......................................................................................21 Portfolio Assessment...........................................................................................22 Research in Writers’ and Instructors’ Perceptions .......................................................23 Research in writers’ perceptions .........................................................................24 Research in teachers’ perceptions .......................................................................25 Related Research in Taiwan.........................................................................................27 CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY.............................................................................29 Participants...................................................................................................................29 Instrument ....................................................................................................................30 Preliminary Studies ......................................................................................................33 Interview .............................................................................................................33 Pilot study ...........................................................................................................35 Data Collection ............................................................................................................36 Data Analysis ...............................................................................................................36 CHAPTER 4 RESULTS ............................................................................................38.

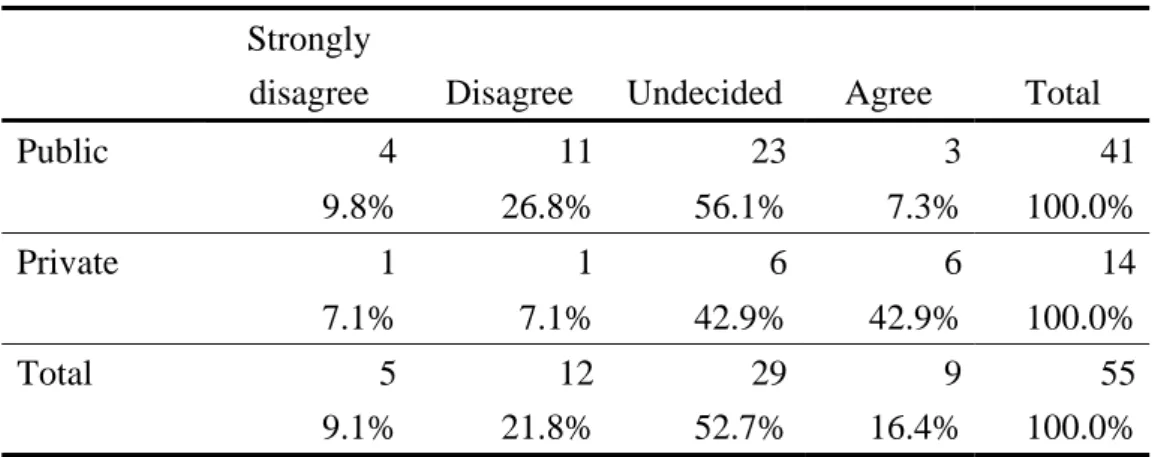

(6) Teachers Downplay the Importance of Writing Instruction.........................................38 Schools Downplay the Importance of Writing Instruction. .........................................42 Factors Influencing Writing Instruction.......................................................................44 Methods to Strengthen the Effect of Writing Instruction.............................................45 Attitudes towards Testing Students’ Writing Ability in the Entrance Exam ................47 Different Views from Public and Private School Teachers..........................................50 CHAPTER 5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ................................................55 The Differences between Teachers’ Perception and Practice. .....................................55 Teachers’ Attitudes toward Writing Assessment in the Entrance Exam. .....................58 Public and Private School Teachers’ Different Perceptions of Teaching Writing........59 Pedagogical Implications .............................................................................................61 Limitations of the Study...............................................................................................62 Suggestions for Future Study.......................................................................................63 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................63 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................65 APPENDICES .............................................................................................................71 Appendix A. Interview Guide (Chinese) .....................................................................71 Appendix B. Interview Guide (English) ......................................................................71 Appendix C. Cover of the Questionnaire (Chinese) ....................................................72 Appendix D. Questionnaire (Chinese).........................................................................73 Appendix E. Questionnaire (English) ..........................................................................78 Appendix F. Correlations between teachers’ attitudes and school types……………..84 LIST OF TABLES Table 3.1……………….………………………………………………………….......29 Table 4.1 Item 4...……….…………………………………………………………….39 Table 4.2 Item 9-10.………..…………………………………………………………39 Table 4.3 Item 21-22…...…………………………………………………………......39 Table 4.4 Item 7-8…...………………………………………………………………..40 Table 4.5 Item 12-15…...……………………………………………………………..41 Table 4.6 Item 1……………………………………………………………………....42 Table 4.7 Item 2………………………………………………………………………42 Table 4.8 Item 11……………………………………………………………………..43 Table 4.9 Item 16-17………………………………………………………………….43 Table 4.10 Item 23……………………………………………………………………44.

(7) Table 4.11 Item 24……………………………………………………………………46 Table 4.12 Item 19-20………………………………………………………………...47 Table 4.13 Item 25………………………………………………………………........49 Table 4.14 Item 25……………………………………………………………………49 Table 4.15 Item 25……………………………………………………………………49 Table 4.16 Comparison of mean differences between public and private school teachers……………………………………………………………………………….50 Table 4.17 Item 4……………………………………………………………………..51 Table 4.18 Item 9……………………………………………………………………..52 Table 4.19 Item 8……………………………………………………………………..52 Table 4.20 Item 17……………………………………………………………………53 Table 4.21 Item 11……………………………………………………………………53 Table 4.22 Item 19……………………………………………………………………54 Table 4.23 Item 20……………………………………………………………………54 Table 4.24 Item 23……………………………………………………………………55 Table 4.25 Item 25……………………………………………………………………55.

(8) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. Background and Motivation In Taiwan, English education had long been riveted on receptive skills, especially reading skills and grammar learning. Recently, the focus of English education has shifted from receptive skills to productive skills because communicative functions are now being emphasized. Students are given more opportunities to practice listening and speaking. However, the ability of written communication is still ignored and devalued. For a long time, students were expected to acquire test-taking skills, especially reading skills. Now, the Ministry of Education gives equal importance to the four language learning skills and appeal to more attention to communicative ability. Students are required to not only memorize vocabulary and master grammar but also acquire productive skills. Students in private or public schools, more or less, have opportunities to learn to listen and to speak. However, writing ability is still considered less important by schools and teachers. In order to enhance students’ speaking and listening abilities, many schools endeavor to develop mechanisms to immerse students in English-speaking environment. The most common measure is for teachers to make use of CDs which come with the textbook. Text readings from CDs are helpful for training students’ listening ability. Besides the text recitation from CDs played in class, many private schools in Taichung City engage native English-speaking teachers to conduct Conversation classes. Students are allowed to have direct interaction with native speakers and encouraged to speak. Even Foreign Language Centers have already been established in private schools to provide an organized system of English education. In 1.

(9) Stella Matutina Girls’ High School, for example, Conversation classes are conducted by native English-speaking teachers. English is no longer just a subject to practice or to study but a means of communication with people. Students respond to teachers’ instruction or directions to achieve tasks through the authentic language use. Another private school not only sets up the Conversation class, but also have students participate in English-speaking and –listening activities as much as possible. Shinmin High School arranges Physical Education, Art, and Civil Education classes to be taught in English by native English teachers. Students can receive a massive exposure to the English-speaking environment. Unlike private schools, which entitle every student to have direct interaction with native speakers, public schools can have only a certain number of students attend English classes conducted by native English-speaking teachers. Besides, public schools do not set up a school-wide program to provide every student with the same opportunity to use English with native English speakers. In public schools, only a certain number of students are privileged to gain access to particular learning resources. Except the classes conducted by native English-speaking teachers, all students have, on average, five class periods a week for an English class taught by Taiwanese teachers. The classes are mainly dominated by reading activities and the textbook serves as the foundation of what students should learn. What teachers do is to have students study one textbook selected by teachers themselves and familiarize students with the grammatical structures, vocabulary, and idioms presented in the textbook. Then students are tested in monthly examinations on what they have learned about the language usage in the textbook. The adoption of extra teaching or learning materials is optional and varies with teachers. Only some teachers arrange extra reading materials for students and even fewer teachers teach students to practice writing. 2.

(10) The focus on speaking, listening, and reading activities contrasts sharply with inattention to writing ability. Although taken as the least important ability of the four skills in classroom, the role of writing ability is clearly stated in the national education policy. The Competence Indicators published by the Ministry of Education affirm the equal importance of the four language learning skills and provide specifications of exact characterizations of target proficiency in accordance with students’ learning stages. Learning tasks which should be accomplished for each stage are proposed. Whether students have accomplished the tasks becomes a criterion so that teachers can evaluate students’ attainment. Based on the specifications in the Competence Indicators, schools as well as teachers plan their curriculum and teachers design tasks or assignments. In terms of writing ability, junior high school students ought to be able to write greeting cards, letters, and paragraphs through the three years of study. Overall, the importance of writing in classroom is downplayed for some reasons. For one, it is generally believed that students at junior high school are incapable of learning to write until they reach a better level of language proficiency at senior high school. To many teachers, writing most of time refers only to sentence level practices such as sentence combing, translation, and transformations. Students are not encouraged to acquire knowledge about paragraph organization, coherence, and transition in composition. The exercises pertaining to writing revolve around sentence level activities. Besides, since English curriculum is often test-oriented and the main task of English instruction is to get students ready for the entrance exam, which is mainly associated with vocabulary learning and reading skills and since writing is not tested in the examination, it is often regarded as avoidable or unnecessary to spend time on. As a result, the time and efforts of English instruction have concentrated on test-taking skills. Both the disregard for writing instruction and the test-oriented curriculum 3.

(11) contribute to the lack of writing instruction. Another reason is that a wide variety of student language levels may disrupt the instruction. It is generally believed that the same level of proficiency facilitates teaching and learning. The more diverse the students, the more problematic the instruction. Public and private schools may face a different extent of student heterogeneity because these two types of junior high schools recruit students in different ways. Public schools are obliged to receive students in a specific educational district. As a result, students with different aptitudes may enter the same school. Especially after the Ministry of Education has announced that junior high schools should place students randomly without considering students’ aptitude, a junior high school class may seat students with different levels of language proficiency. That is, a student whose English proficiency might have surpassed that of senior high students may sit in the same classroom with another student who cannot memorize all the basic vocabulary presented in the textbook. On the contrary, students who plan to enter a private school, on the whole, must pass tests administered by the school. Generally speaking, most private school students must reach a certain standard of proficiency and those in first-rate private schools are superior to most public school students. Although encountering the enormous diversity of student proficiency, some public schools follow the government policy but with a little flexibility. They divide classes into two levels according to their scores. The better half of the classes goes to an A-level class and the other half goes to a B-level class. Students of each level come from two or three classes and study main courses together, such as English, Science, Mathematics, and Chinese. This ability grouping is believed to help teachers adjust their teaching more easily according to students’ proficiency or aptitude and learning progress. Due to the mechanism, to many teachers, writing instruction becomes feasible and may go well in an A-level English class. On the other hand, it still 4.

(12) remains doubtful to many teachers that writing instruction is practical in classes of mixed proficiency or in classes rated as B-level.. Research Context about Writing Instruction Writing is a very complex and demanding activity. It involves thinking, planning, organizing, and mastering many levels of language (Hamp-Lyons, 2003). Writing seems, to FL teachers, unpractical if students haven’t reached a certain level of competence. The problem here is what level of competence is needed. There is little research, to my knowledge, that provides such information. Scott (1995) argues that writing competence is closely associated with other language competences, such as linguistic, speaking, and reading competence. She also hypothesizes that writing competence is not language specific but a general notion. This threshold level of competence for writing also prevailed in ESL writing two decades ago as Leki (1992) states that “in the early 1980s, L2 writing classes were still emphasizing linguistic competence as a prerequisite to learning to write.” Writing would be postponed until students had to some degree mastered the linguistic structures. Writing instruction has been declared unnecessary and difficult to practice by some FL teachers. However, it is found in literature that many researchers argue for the necessity of writing instruction in FL courses (Zamel, 1983; Reichelt, 1999). Some researchers hold that writing instruction is appropriate and essential to any level of language proficiency (Zamel, 1987; Scott, 1996; Raimes, 1983; Hadfield & Hadfield, 2000). Zamel (1987) argues that approaches to the teaching of composition are not only appropriate for native speakers but also effective for teaching all levels of writing, including ESL composition. Besides the importance of writing, writing instruction has been extensively discussed in L1, ESL, and FL research. Exploring the Dynamics of Second Language 5.

(13) Writing (Kroll, 2003) and Teaching ESL Writing (Reid, 1993), to name a few, have explored issues and teaching approaches to L2 writing. Reichelt (1999) also gives a comprehensive view of FL writing and research pedagogy in the US. From over 200 works, he identifies two categories of writing research. One is topics addressed in research-oriented works including analysis of texts, writers’ processes and/or attitudes toward pedagogical procedures, writers’ processes/attitudes in relation to text analysis, and some aspect of FL pedagogy. On the other hand, topics addressing pedagogical works include overall writing curriculum, writing assignments or pedagogical techniques, and FL writing feedback and assessment. Research in FL writing instruction in Taiwan has put substantial emphasis on the effects of a certain pedagogy and students’ performance in relation to the pedagogy. We still know little about how the teacher as a designer or implementer perceive and develop a teaching measure. In literature, teachers seem to play a marginal and subordinate role. But, in FL classrooms, teachers actually play the most important role. They dominate the class and lead students to where they want them to go. Therefore, teacher beliefs and perceptions regarding English curriculum and writing instruction appear to be crucial to students’ learning. Some studies have confirmed that teachers’ experiences, beliefs, and attitudes would influence their teaching (Freeman & John, 1993; Cumming, 2003; Shi & Cumming, 1995). For example, post-graduate education is related to teachers’ teaching (Cumming, 2003). Teachers’ personal knowledge is helpful for their instruction (Golombek, 1998) Cumming (2003) also claim that further exploration of teachers’ beliefs and attitudes in their current curriculum can be helpful for novice teachers. Thus, identifying areas of commonality and difference in their stated curriculum practices should be of particular value in helping 6.

(14) novice instructors to focus their thinking on key aspects of their courses, to reflect on their ongoing teaching experiences from a global perspective, and to anticipate curriculum alternatives that the may wish or be obliged to pursue. (p.73). Statement of the Problem Observations from classroom reveal that writing instruction has not been seriously put into practice by all the English teachers and it is often considered of minor importance. Although there is much research in pedagogies and approaches to writing instruction and in writers’ processes/attitudes to some aspect of pedagogy, researchers have paid insufficient attention to how teachers perceive writing instruction per se. Little attention is focused on writing instructors’ conceptions in terms of their descriptions of their writing instruction practices, personal beliefs, justifications of their pedagogical actions, and self-evaluation of their curriculum in school.. Purpose of the Study This study aims to examine junior high school instructors’ concerns, problems, and perceptions related to writing instruction. It is hoped that this study can attract researchers’ and teachers’ attention to writing instruction and make them notice the importance of writing ability for junior high school students. Besides, teachers’ problems, concerns, perceptions, and recommendations can be revealed to be helpful for the curriculum designing in the future. It is also hoped that effective measures to cope with issues involved in writing instruction can be developed and that this present study can shed light on the improvement of teacher education (Freeman and Johnson, 1998). Novice teachers can benefit from the thoughts and experiences in-service 7.

(15) teachers have provided. Moreover, teachers’ attitudes towards writing assessment in the entrance examination can be made explicit. The results may serve as the basis for a future revision of national curriculum. The study is hoped to provoke other researchers’ interest in further investigating the national English curriculum and the English curriculums at junior high schools.. Research Questions Pedagogies of writing instruction have been heatedly discussed. However, it still remains uncertain what problems in-service teachers face and what attitudes they hold towards writing instruction. Thus, the present study was designed to find out teachers’ existing practices, their beliefs and their problems regarding writing instruction. The research questions that guide this investigation are: 1. How teachers perceive the implementation of their English curriculum? 2. What factors do teachers perceive influence writing instruction? 3. What changes concerning writing instruction would they recommend for the existing language program? 4. Do teachers agree that writing should be tested in the entrance exam? 5. How differently public and private school teachers perceive issues about writing instruction? To further analyze or interpret the results, teachers’ views on students’ language learning needs and motivations are also investigated.. Research Design A questionnaire was developed to gather information on beliefs and perceptions of writing instruction at junior high schools. Teachers’ personal information, such as 8.

(16) sex, education, age, and experiences of English teaching, was also obtained. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the scope of writing instruction and set the framework of the study. Based on the results of the interviews, a preliminary questionnaire was created and tried out. Based on the feedback from the tryouts, the questionnaire was finalized and administered to 57 English teachers in three public and three private junior high schools. The results of the questionnaire were analyzed by descriptive statistics and paired t tests.. Organization of the Thesis The beginning of the thesis explains what motivates the researcher to discuss teachers’ perceptions towards writing instruction in junior high school. The following chapter gives an overall picture of L1, ESL, and EFL writing research. Major writing instruction approaches and measures to evaluate writing ability are also introduced. Most importantly, research regarding students’ or teachers’ perceptions is revealed. This chapter ends with a brief introduction of research in FL writing done in Taiwan. Chapter 3 includes a thorough description of how the study was conducted. Participants, instrument, procedures of data collection, and the method of data analysis are made explicit. Results of the study are presented and analyzed in Chapter 4. The conclusion, pedagogical implications, limitations of the study, and suggestions for further study are reported in the last chapter.. Definition of Terms Writing Writing and composition are often changeable. In L1 and ESL research, it refers to a paragraph or an essay. As Raimes (1983) puts it, writing is based on the assumptions that “writing means writing a connected text and not just singles sentences, that 9.

(17) writers write for a purpose and a reader, and that the process of writing is a valuable learning tool for all of our students.” In FL classrooms, non-native English teachers sometimes mix a sentence-level exercise up with a paragraph writing. In this study, writing or composition refers to a paragraph or an essay writing above sentence exercises, such as pattern sentences, sentence combination, substitutions or transformations. To accomplish a writing task, not only do students need to possess the knowledge of grammatical structures and vocabulary but they also have to acquire the knowledge of paragraph organization or rhetorical structure.. The Entrance Exam The entrance exam for junior high school students is called the Basic Competence Test. Five subjects are tested as subtests. Each subtest is designed based on the specifications of the Competence Indicators published by the Ministry of Education and measures a student’s ability to achieve those specifications. In the English test, there is only one test format—multiple choices. Forty-five multiple choices in total are tested on vocabulary, grammatical structures, idioms and reading comprehension. (See http://www.bctest.ntnu.edu.tw/). 10.

(18) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. FL Writing in junior high school has long served a subservient role by teaching learning linguistics features or being used to develop other skills. However, researchers have now called teachers’ attention to students’ writing ability for communicative purposes. In addition to communication, Raimes (1983) also argues that writing benefits students in other three ways. Writing not only equips students with knowledge of grammatical structures, idioms, and vocabulary but gives them “a chance to be adventurous with the language.” Moreover, writing involves students in language use, which enhances students’ thinking. For FL teachers in junior high school, writing often refers to sentence-level exercises. The sentence drills such as fill-ins, substitutions, transformations, and sentence patterns create no meaningful purposes or context for writers. Given that teachers often limit writing instruction to sentence writing and that they lack teaching resources, some researchers have developed teaching techniques for teachers to integrate writing activities into English class. For example, Hadfield & Hadfield (2000) introduce a collection of writing activities, which demonstrate how sentence writing can be developed into paragraph or essay writing. Each activity contains three stages: lead-in, organizing texts, and creating texts. Through the three stages, students are first introduced to the background knowledge of a certain topic and the language points needed. They are then given controlled writing practice for text organization techniques. At the last stage, students are asked to write a text for a particular purpose or context. In one activity, for example, teachers ask students about their penpals, if they have any, for information. Then students practice reordering the jumbled sentences teachers have written down on the blackboard such as: name my John is. 11.

(19) Then a letter with unorganized sentences is shown to be reordered. After students rewrite the letter, they are asked to write a reply. The increasing importance of writing ability and more attention from researchers to FL writing initiates the interest of study to explore how English teachers view writing teaching in junior high school. Thus, this chapter starts with a brief review of research in the field of ESL and EFL writing pedagogies. It also includes a discussion of the measures to evaluate students’ writing ability. Second, focus of review is on learners’ perceptions and attitudes towards their learning of writing and towards a certain aspect of a writing pedagogy or technique. Moreover, teachers’ perceptions or assumptions, on which practice in class is based, are explored. Finally, related research done in Taiwan are briefly introduced.. Writing Approach to Writing Instruction Extensive research in writing has revolved around pedagogy. Many pedagogies or approaches have been influential in classrooms. Many researchers propose different perspectives on the research of second language writing and approach to writing instruction. Reichelt (1999) reviews research in FL writing and research pedagogy in the US and identifies two categories of writing research: topics addressing research-oriented works and topics associated with pedagogical works. Raimes (1993) gives a brief historical framework of writing approaches for two and a half decades, from 1966 to the time when she did the study. She also notes that the four approaches are never “discrete and sequential.” From 1966, the focus on “form” reinforces teachers’ concern for the learning of grammatical structures and contrastive rhetoric. Teachers are not interested in the content or ideas students write about but their mastery of linguistic features and “logical construction and arrangement of discourse forms” (Silva, 1990). From 1976, the attention shifted to the “writer,” leading to the 12.

(20) process approach. “Teachers have begun to allow their students time and opportunity for selecting topic, generating ideas, writing drafts and revisions, and providing feedback” (Raimes, 1993). From 1986, the research in “content” and “reader” started to associate writing with academic activities and the subject matter the ESL students are studying. Silva (1990) proposes four most influential approaches in ESL writing research: controlled composition, current-traditional rhetoric, the process approach, and English for academic purposes. Similar to Silva’s framework, Matsuda (2003) proposes four development stages of writing research: writing as sentence-level structure, writing as discourse-level structure, writing as process, and writing as language use in context. In conclusion, these important approaches mentioned above—grammar, controlled approach, contrastive rhetoric, the process approach, and genre approach—are considered important approaches or issues to writing research. But, the writing approaches reviewed in the following sections will skip genre approach for it is closely associated with academic contexts. In FL junior high school, students are required to possess basic language ability and not prepared to study English for an academic purpose. Immersing junior high school students in the academic discourse community is the least likely thing for EFL teachers and researchers to consider. Thus, the following sections give a brief discussion of the writing pedagogies in time order: grammar approach, controlled composition, contrastive rhetoric, and the process approach.. Grammar approach Grammar has been the focus of writing instruction because it can be straightforwardly taught (Raimes, 1984) and a piece of good writing is believed to conform to grammatical forms (Frodesen & Holten, 2003). However, as the focus of 13.

(21) recent research has shifted from product-based approach to process approach, meanings and ideas are emphasized. Attention to linguistic structures is postponed after ideas have been clarified. The grammatical focus has gained less importance in the writing process. Students are then not encouraged to correct their errors until at the very final stage of writing process. Truscott (1996) also strongly argues against the use of grammar correction because of the ineffective and harmful effect on students’ learning. Truscott cites a body of research to conclude that grammar correction should be abandoned. But, a few researchers now argue for instructors’ consistent use of grammatical correction throughout students composing stages. In process approach, grammatical instruction is proved important throughout students writing stages. As Ferris (2003) points out, feedback is most effective at intermediate stages of the writing process. Instructors’ consistent attention during student’s drafting process is important; however, instructors are advised not to overdo the correcting grammatical errors (Frodesen & Holten, 2003). Grammar has also been regarded as a bridge to communication. Frodesen (2001) stress its essential role in effective written communication. Frodesen believes that grammar should help writers develop knowledge of linguistic features and grammatical systems to communicate with readers. She also suggests that grammar helps students develop discourse-level grammatical principles, such as cohesion. The goal of communicative functions still depends to a certain degree on grammar for clarifying meanings (Thornbury, 1999). Although it has been given a less predominant place in second language writing classrooms (Frodesen & Holten, 2003), grammar instruction is believed to be dominant in most FL English or writing courses, including FL courses in Taiwan.. 14.

(22) Controlled Composition Controlled composition has been taken as a tool of reinforcing oral habits and focusing on learning of language structures. This product-based approach is mainly concerned with knowledge about vocabulary, syntax, and cohesive devices. Writing is primarily seen as “the result of the imitation of input, in the form of texts provided by the teachers” (Badger& White, 2000). Because controlled writing is usually believed to be helpful for developing students’ accuracy and correctness of linguistic knowledge, this approach prevails in many ESL composition classrooms (Silva, 1990). Raimes (1983) distinguishes five types of controlled writing activities: controlled, composition, question and answer, guided composition, parallel writing, and sentence combining. Controlled writing is believed to be suitable for all levels of students. “Controlled writing is easy to mark and much less time-consuming, so more can be assigned.” However, moving beyond the controlled writing, learners should learn to create and organize their own ideas. They should try to develop the knowledge of organization of written discourse, which is “culturally determined.” Raimes (1983) states that “controlled writing is a useful tool at all levels of composition teaching and not just in the early stages before students have gained enough fluency to handle free writing.” Models are widely used in this approach and Watson-Reekie (1984) proposes three ways in which models are beneficial: (1) Models provide exposure to the lexical items, structural patterns, and conventions of the target language at all levels of discourse in particular, they take us beyond sentence level. (2) They demonstrate many modes of rhetorical organization and stylistic variety, related to variables such as communicative purpose and anticipated audience. (3) They are, especially when authentic rather than composed to order, windows onto culture in its widest sense, revealing 15.

(23) customs, values, assumptions, and attitudes toward the world and man as perceived by speakers of the target language.. (p.97). Watson-Reekie (1984) believes that the models are treated as “a source of patterns to be reproduced or manipulated in various ways,” and, as a result, the product would seem very artificial. Writers are instructed to change certain features of the model in an arbitrary way. On the other hand, the designated features allow students to concentrate on one or two linguistic structures at a time (Raimes, 1983). Students should not be given too much stress during the writing process. However, according to Watson-Reekie (1984), this product-based approach cannot explicitly explain how the model was constructed and how a good writing is made. She argues that models should be used within the writing process. It is essential that teachers define the purpose and utility of writing tasks, select appropriate models for stimulus, guidance, and support.. Contrastive Rhetoric Kaplan’s (1966) investigation of nonnative students’ essays initiates the theory of contrastive rhetoric. The theory claims that sets of thought patterns systematically varied from culture to culture and even from time to time. Students from different language backgrounds prefer a certain type of rhetorical structure. Wring styles are evolved out of culture and reflect students’ social, historical, and political realities (Leki, 1992). Thus, teachers should be aware that rhetoric is not universal or innate. Teachers should also not hurry to jump to conclusion that texts created by nonnative speakers are illogical or carelessly written, if they do not follow the structural patterns of the target culture. Teachers are encouraged to explore the relationship between culture and written products, and especially to find out “how individual students bring distinct learning styles to the classroom (Reid, 1993b).” The study of Zamel (1983) 16.

(24) also suggests that teachers or schools design course syllabi and individualized lesson plans which reflect student’s diversity in “native culture, learning styles, and schemata.” Contrastive rhetoric offers specific activities such as model essays and journal writing. Watson-Reekie (1984) discusses the utility of models. First, models help students develop knowledge about linguistic lexical items, structural patterns, and conventions of the target language. Second, models display rhetorical organization and stylistic variety. Third, model reveals customs, values, assumptions, and attitudes of different cultures. However, Connor (2002, 2003) suggests that teachers and researchers be aware of the intercultural differences. The cultural patterns should not be viewed as a received mode, as they vary from person to person. The differences in written communication can come from multiple sources, such as L1 national culture, L1 educational background, genre characteristics. For instance, one inexperienced writer in the native language may have not acquired rhetorical patterns of their own cultures (Leki, 1992). Some ESL researchers oppose the mere imitation of patterns and blunt use of models because this simplified view about contrastive rhetoric leads to prescriptive teaching without letting students know how sentences are constructed and how meanings are fit into a specific structure (Zamel, 1983; Leki, 1992; Watson-Reekie, 1984). A narrow use of contrastive rhetoric values only prescriptions, which interfere with other learned systems (Raimes, 1993). Zamel’s (1983) findings also show that the outlines that students are asked to formulate inhibit the transfer of certain cultural thought patterns.. Process Approaches The previous two approaches are product-based, which overlook the 17.

(25) communication of meanings and students’ composing processes. From the 1970s, writing has been defined as a process of discovering ideas and problem solving and creating multiple drafts for different functions, such as generating, clarifying, rearticulating, and refining ideas (Zamel, 1983, 1987). The process approaches, which are mainly concerned with linguistic skills rather than with linguistic knowledge, typically have four stages: prewriting/planning; composing/drafting; revising; and editing. This is a cyclical (Badger & White, 2000), non-linear, exploratory, and generative (Zamel, 1983) process. Teachers and writers may focus on different issues such as content, organization, or grammar at different stages of the writing process (Badger & White, 2000; Seow, 2002; Ferris, 2003). Some features of this approach differ from previous writing approaches. For example, a teacher of process approach responds to student writing not at the final stage but during the process of writing, which allows the teacher or peers to give spontaneous comments on language errors, global content, and organization of ideas, not merely at the final stage of composing stages as in a traditional writing class (Seow, 2002). In a product-based approach, student writing focuses on accuracy of grammar, diction, and linguistic mechanisms all the way through. As soon as the texts are submitted for teacher evaluation and correction, students often feel unnecessary to further correct or revise their final texts again. Feedback should be given throughout the composing processes (Zamel, 1987) because the feedback, no matter from instructors or peers, may be the most significant to writers (Ferris, 2003). There are three types of feedback: written teacher commentary, peer feedback, and oral teacher-student conferences. Although the three types of feedback have been confirmed to be beneficial, some researchers have investigated which type would be most beneficial to students (See Zhang, 1995). Zang’s studies (1995, 1999) indicate 18.

(26) that “peer feedback does not have an affective advantage over teacher feedback in the ESL writing class.” Ferris (2003) argues that teacher-student conferences and peer feedback outweigh written teacher commentary. However, Ferris believes that no research evidence shows that one should completely replace the other. Therefore, Zang (1995) urges that teachers take into consideration the strategies and types of feedback they plan to adopt by asking about students’ feelings. However, some researchers cast doubt on the effect of feedback. The study of Lee (2004) shows that teachers were incompetent to correct errors and suggests more training be given to pre-service and in-service teachers. Truscott (1996) provides a body of research to verify that grammar correction is not only ineffective but even harmful for students’ learning. He argues that the acquisition of grammar structures is a gradual and complex learning process, not so simple as a direct transfer of knowledge from teacher to student. Different learners may differ in their developmental sequences. When teaching or learning fails to affect their learning processes, it only produces limited value and is a superficial form of knowledge. Truscott (1996) points out that making grammar correction is impossible from various theoretical points of view. There are also practical problems teachers would encounter while giving grammar correction. Ferris (1999) agrees with Truscott (1999), stating that “evidence supporting the effectiveness of error correction is little.” Still, Ferris holds a optimistic view and criticized the limited, dated, incomplete, and inconclusive evidence Truscott (1996) adopted The process approaches are often criticized for causing linguistic inaccuracies (Badger & White, 2000; Zamel, 1983). The study of Zamel (1983) shows too much focus on meaning alone kept students from carefully examining certain surface features of writing (Zamel, 1983). In response to this drawback, Ferris (2002) develop an editing process approach in an attempt to help students reduce their linguistic 19.

(27) errors. The researcher proposes three principles: (a) finding major patterns of error; (b) personalizing editing instruction; and (c) focusing on only frequent, global, and stigmatizing errors. Besides the language errors, students also have to correct errors in global content and organization of ideas (Seow, 2002). The applicability of this approach to EFL beginning learners remains doubtful because it engages the writer and the instructor in multiple and simultaneous acts and make enormous demands on both of them. The process approach is unlikely to be practiced in an EFL high school because of time constraints and pressure of meeting a schedule. However, researchers have held a positive view. Earlier, Zamel (1983) indicates this approach is considered appropriate for advanced ESL students, but she later argues (1987) that this approach can be appropriate for all levels of writing, including ESL composition. Kroll (2001) also believes that the process approach prevails for both L1 and ESL settings.. Writing Assessment Writing assessment plays a role in defining students’ proficiency, diagnosing their strengths and weaknesses, and realizing how much students’ have achieved (Weigle, 2002). Quoting Bachman and Palmer (1996), Weigle (2002) argues that one of the assessment purposes is to make inferences about language ability and the other is to make decisions based on the inferences. For a long time, writing ability has been tested indirectly in the forms of multiple choices, grammar completion, etc. Studies have also shown that writing tests are often highly correlated with concurrent objective tests. The results provide foundation for the use of indirect writing tests. But most ESL professionals these days believe that it is better that students are tested by directly writing a composition on a certain topic. (Hamp-Lyons, 2003). 20.

(28) Researchers have tried to design valid methods to measure writing ability. Their focus on direct testing have long shifted to the other alternative method—portfolio assessment. In the following sections, direct writing test is introduced and followed by a brief review of portfolio assessment.. Traditional Assessment Although direct tests are considered authentic and straightforward, some problems have been discussed in literature. The rater variable, the writing prompt, and the time constraints are important issues involved in writing assessment (Cho, 2003). To construct a valid writing test, Hamp-Lyons (2003) proposes four components to ensure the validity of the test: the writer, the task, the reader(s), and the scoring procedure. She maintains that teachers or test developers pay more attention to differences between writers in their “race, gender, ethnicity, culture, language background, level of education in L1 and in L2, stage of cognitive development, learning style, motivation, and degree of support in the home background.” She also calls for more research on the gap between the writer’s understanding of the test topic and the real intention of the topic. Although principles and stages of test design have been widely discussed (Weigle, 2002), the validity and reliability for direct writing testing has been questioned. For example, Leki and Carson (1997) intended to find out how ESL students responded to different choice of writing prompts in an academic context. Students were given different kinds of source of information to write a text: their own knowledge or experience; a textual source as a prompt; and a source text drawing on readers’ academic knowledge. Researchers found that the variables for writing without a prompt were lack of time, familiarity with the topic, and topic-related ideas, models, and vocabulary. In a second condition, students were given a prompt which “make 21.

(29) some connection between that material and their own experiences and opinions.” The prompt served as a model to stimulate thinking and supply much useful language-based information. As for the third kind of prompt, it was found that reading and understanding the source texts might produce additional burdens. Moreover, DeRemer (1998) investigates how raters define the assessment task in different ways. Raters may give a score based on their impression of a text, pay more attention to the description of the rubric, or they may focus only on a particular criterion without considering the others. This study refutes the belief that raters would evaluate student writing by internalizing a set of criteria. To assess student writing, three traditional approaches are widely discussed: holistic, analytic, and multiple trait scoring. (See Bailey, 1998; Hamp-Lyons, 2003; Weigle, 2002). However, the dissatisfaction of direct testing of writing and of holistic scoring has caused researchers to experiment with portfolio assessment (Hamp-Lyons, 2002). Thus, in the following section, we turn to a discussion of a process-based writing evaluation—portfolio assessment, which has been viewed as an alternative assessment.. Portfolio Assessment Driven by the developments in writing assessment, portfolio assessment has become the most popular form of alternative writing assessment. A portfolio is a collection of student work to appraise their progress over a period of time. In Brown and Hudson’s (1998) words, portfolio assessments are “purposeful collections of any aspects of students’ work that tell the story of their achievements, skills, efforts, abilities, and contributions to a particular class.” Students create their own portfolio with the aid of teachers and peers. With clear criteria or specific objectivities in mind, writers select samples of their work and reflect on their learning. The creation of the 22.

(30) portfolio can identify students’ weakness and strengths for educational benefits. In this way, teachers can gain in-depth knowledge of students’ learning and provide individualized instruction. Although beneficial to teaching and assessment, building up a portfolio is a skilled activity and may make some teachers uncomfortable (Hamp-Lyons, 2003). Song and August (2002) also argues that “the actual evaluation of portfolios is inevitably labor intensive,” and “make[s] substantial demands on instructors.” Brown and Hudson (1998) also reports five disadvantages: the issue of design decisions, logistics, interpretation, reliability, and validity. The use of other assessments in place of the traditional test still needs more research. Hamp-Lyons (2002) argues that “the use of portfolios for formal, high stakes assessment is still problematic.” Polio and Glew (1996) also cast doubt on anything other than a timed essay for a placement exam. However, Song and August (2002) may have thrown some light on the issue. Their study confirms the results of previous studies: ESL students have difficulties passing a timed impromptu test. They also provide evidence that the portfolio assessment successfully predicted students’ success in a subsequent English course and this type of writing assessment can serve as appropriate assessment alternative.. Research in Writers’ and Instructors’ Perceptions Educational researchers have made considerable efforts to build up theories, identify effective methods and approaches, and develop valid assessments for teaching writing. However, Freeman and Richards (1993) argue that attention to technique and procedure should be shifted to the conceptions of teaching underneath the pedagogies. A body of studies have proved that teachers’ philosophy, beliefs, experiences and conceptions on teaching have influence on their pedagogical practices (Shi & Cumming, 1995; Cumming, 2003; Kroll, 2001; Winer, 1992). 23.

(31) Therefore, research in perceptions and attitudes of the participants involved in teaching and learning is required. Polio (2003) cites some writer-related research, most of which studies perceptions and experiences of ESL learners in content courses. Reichelt also (1999) cites some research in FL writers’ attitudes toward pedagogical procedures and their attitudes in relation to some aspect of text analysis. However, the research in perceptions of the participants, namely instructors and writers is still lacking.. Research in writers’ perceptions Although research in writers’ perceptions is few, we still need to look into what have been covered in literature so far. In this section, a brief review of research in perceptions or attitudes of writers is presented. Some researchers have great interest in helping students to analyze a collection of authentic texts (corpus) and believe that looking through texts is helpful for writing instruction and learning. Many researchers start to examine students’ perceptions and effect of corpus use in writing class. This language-based approach proves beneficial to the development of L2 writing skills and can build students’ confidence (Yoon & Hirvela, 2004). They investigate the corpus use in ESL academic writing courses from students’ perspectives and intend to understand learners’ actual use of corpora and their attitudes toward corpus use in the L2 writing classroom. The results show that the ESL students, overall, felt positive about the application of the corpus activities. However, the intermediate-level learners showed more positive responses than advanced learners. The different views from these two groups may be explained by the teacher’s use of different amount of time and types of activities to the two groups. Lee (2004) compared junior high teachers’ and students’ perceptions of error correction. As pointed out, students are required to submit a writing of 120 to 300 24.

(32) words every 2 or 3 weeks. The study showed doubt on teachers’ competence to correct errors and suggested more training for pre-service and in-service teachers. In the study of Leki and Carson (1997), ESL students responded to different choice of writing prompts in an academic context. Students are given different kinds of source of information to write a text: their own knowledge or experience; a textual source as a prompt; and a source text drawing on readers’ academic knowledge. Another approach is to study L1 learners’ perceptions of L1 literary instruction to help understand what the students may bring to the process of L2 writing. Kobayashi and Rinnert (2002) study how students view their L1 wiring experience and instruction in high school and their results conform to the common assumption that Japanese students receive little training in L1 writing. As more universities assign essay writing as part of their entrance exams, more students have received intensive training in writing. The study also finds that the training in L1 writing help students build confidence and self-esteem.. Research in teachers’ perceptions Some studies focus on teachers’ perceptions of their teaching or some aspects of writing teaching. Lee (2004) compared junior high teachers’ and students’ perceptions of error correction. The study showed doubt on teachers’ competence to correct errors and suggested more training for pre-service and in-service teachers. Shi and Cumming (1995) interviewed five experienced teachers after observing their ESL classes and suggest that teachers were more concerned with the knowledge of language use, rhetorical organization, ideas and content, or composing processes. The study shows that teachers’ conceptualizations of their instruction are vital in curricular changes. Some research in teachers’ perceptions helps us understand what problems or 25.

(33) challenges teachers encounter. Winer (1992) analyzes dialogue journals of 100 students to trace how their attitudes and awareness change through a TESL writing practicum. This consciousness-raising study was designed to investigate how their negative feelings would change during the process of the course. The results show that either NSs or NNSs experience four obstacles: (a) a dread of writing, (b) boredom with general topics and intimidation by technical ones, (c) insecurity about their own writing skills, and (d) uncertainty of their teaching skills. Student teachers often associated their negative feelings with their previous experience as learners in L1 or L2 writing classes. Their prior experiences as both learners and teachers, if they had had writing teaching experience, indeed influenced how they viewed and taught writing. Troia and Maddox (2004) examine L1 writing instruction in middle schools. Eight special and ten general education teachers were interviewed and their views about their instruction were rated. Some factors which negatively influence their efforts to deliver effective teaching are identified: requirements to teach a great deal of subject matter content, large numbers of students, students’ varied backgrounds and abilities, lessened student motivation, failure to help students with disabilities to meet writing needs in the general education classroom, and underdeveloped district-sanctioned writing curricula. The study of Peyton et al. (1994) reveals the challenges ESL teachers met in their classrooms. Some teachers had to strive against the long-held attitudes and instructional practices in the schools. They needed to struggle not only with the school, but also with students and even with themselves. All of the teachers also had to struggle under the constraint of time, space, and resources. You (2004) observed and interviewed ten English writing teachers in college and found that writing instruction is test-oriented. Teachers focused on language skills for 26.

(34) test-taking rather than on communication skills. Students’ needs were also ignored. Teachers were unable to enhance professional training due to heavy loads of teaching.. Related Research in Taiwan This section provides a brief review of research done in Taiwan. The works cited come from Electronic Theses and Dissertations System, which collect theses and dissertations published by Taiwanese graduate students. The topics of most research in FL writing done in Taiwan can be placed within four main categories: works that focus on the effect of pedagogical techniques; works that focus on student attitude toward a writing teaching approach; works that focus on textbook design; and works that focus on teachers’ opinions about an aspect of English education in their schools. It has to be emphasized that the research topics of some studies may overlap and should be put under more than one categories. Most researchers are interested in creating a new writing approach or applying an existing one to improve students’ performance. The use of model-based instruction proves beneficial to the beginning learners (Chiang, 1999). Chen (2006) investigates the effect of an integration of reading and writing activities. The results show that the reading-to-writing method makes students more motivated to write and help them acquire linguistic knowledge. Although the applicability of portfolio assessment in junior high school still remains questionable, Wang (2002) examines the application of portfolio assessment in junior high schools. The research shows that students held a positive attitude toward the portfolio assessment and they benefited from the assessment. The results of Huang (2003) suggest that pre-writing strategies in a process approach help senior high school students develop their knowledge of essay organization. Some studies aims to investigate the effect of a certain pedagogy but also at the 27.

(35) same time explore writers’ attitudes and opinions of receiving instruction in that pedagogy. When Chang (2003) examines the effects of a portfolio assessment project, he also gathers information about students’ opinions about the method. Three theme-based projects designed by Chung (2005) reveal positive responses from junior high school students to this approach. The study of Huang (2004) aims to explore senior high school students’ perceptions of peer and teacher feedback. The results show that learners accept the notion of multi-audience. The researcher argues that the use of peer feedback can be integrated into the writing classes. Besides the research in writers’ attitudes toward writing approaches, students are also asked about their preference for their current English textbooks. By investigating junior high school students’ preference for textbook activities, Chao (2005) analyzed the relationship between preference and learning style and the relationship between preference and motivational intensity. Chan’s (2005) study, in addition to students’ views, also includes junior high school teachers’ opinions about textbooks. Another study also provides a comprehensive view of textbooks from junior high school teachers (Tang, 2005). The findings show that over one-third of teachers believed that the current English textbooks can’t improve students’ writing ability. Research in teachers’ attitudes and perceptions often revolve around textbook design as discussed above. Guo’s (2004) study explored what high school writing teachers in Taiwan thought about teaching writing and their view of teacher education and teacher development. Factors influencing pedagogical practices were students’ limited vocabulary and ideas, responding to student writing, busy schedule, time constraints, big class size, and administrators’ and parents’ expectation.. 28.

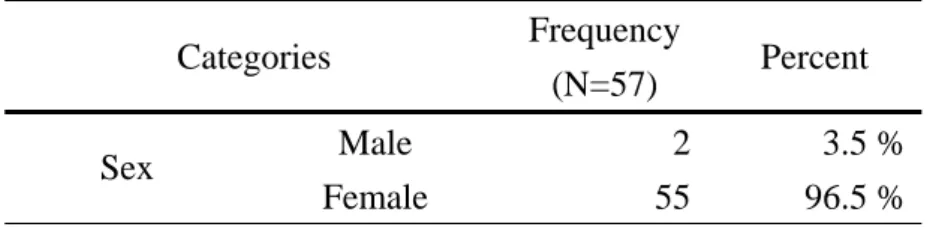

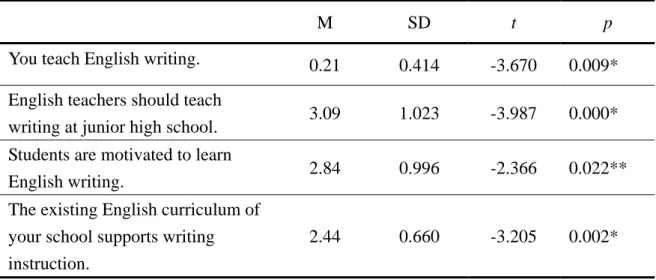

(36) CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY. The present study employs a qualitative approach to investigate junior high school teachers’ perceptions of English writing instruction. The participants, the instrument, the procedures of data collection, and the data analysis are reported. The procedures and the results of the preliminary studies are also described.. Participants Fifty-seven teachers from three public and three private junior high schools in Taichung area responded to this questionnaire. The demographic information is presented in Table 3.1. Only two of them are males (3.5%) and the 55 participants are female (96.5%). Among all, 41 participants were from three public schools (71.9%) and 16 participants from private schools (28.1%). Age distribution reveals that about 80 percent of participants were aged under 40 years of age, 15.8% were in the 41-50 year age range, and 5.3% in the 50 up year age range. Around half of questionnaire participants (50.9%) had had no more than five years of teaching experience in junior high school, 15.8% had had six to ten years of experience, and 26.3% had had more than 10 years of teaching experience. Seven teachers (12.2%) had had fewer than five years of teaching experience in senior high school. About one-third of participants got a master degree and two-thirds a bachelor degree. Table 3.1 Demographic Information Categories Sex. Frequency (N=57). Male Female. 2 55 29. Percent 3.5 % 96.5 %.

(37) School. Age (years). Experience (years) Education. Public. 41. 71.9 %. Private. 16. 28.1 %. 23-30. 17. 29.8 %. 31-40 41-50 50 up. 28 9 3. 49.1 % 15.8 % 5.3 %. 1-5 6-10 10 up. 29 9 15. 50.9 % 15.8 % 26.3 %. Bachelor. 39. 68.4 %. Master. 18. 31.6 %. Instrument A questionnaire was developed to gather information on how junior high school teachers viewed current writing instruction in school and its role in language program. Teachers’ personal information, such as sex, education, age, and experiences of English teaching, was also obtained. Teaching experience, here, refers only to their teaching experience in junior high school, excluding their experiences in senior high school or cram schools. The questionnaire (see Appendix A) includes a total of 25 questions, in which both open-response and closed-response questions were used. In order to give teachers more expediency of answering the questionnaire, multiple choices were provided for them to easily tick appropriate choices. Besides multiple choices, another two question formats were used—yes/no question and Likert-scale questions. The questionnaire was developed through two main phases. At the first stage, in order to explore the scope of the study and to set the framework of a valid questionnaire, extensive information on how teachers view writing instruction was acquired. Therefore, semi-structured interviews with three junior high school English teachers were conducted to gain their general perspectives and perceptions toward. 30.

(38) English writing instruction. An interview guide was adopted (see Appendix B) with varying specific follow-up questions. Five main areas of information were explored: (1) the practices of teachers’ writing instruction; (2) their beliefs and justifications of the pedagogical practices; (3) their self-evaluation of the effectiveness of their writing instruction; (4) their perceptions of students’ learning of writing instruction; (5) whether writing should be tested in the entrance exam. Besides, teachers’ background information was also taken into consideration such as education background, teaching experience, the number of classes they were currently teaching, and the average number of the classes they taught. More details about the design and results of the interviews were reported in the next section. In the second phase, a preliminary questionnaire was developed based on the data of the interviews. The tentative questionnaire contained five areas of information: teachers’ views on language learning needs and on writing teaching, their opinions about existing language curriculum at their schools, suggestions about the language program, and opinions about whether to test students on writing in the entrance exam. Almost all questions were on a 4-point Likert scale, which meant not to allow subjects to give a neutral or undecided answer. Teachers’ positions were expected to be made clear and highlighted. Besides, a multiple choice question was adopted for participants to tick more than one option. Options were offered in order to reduce the time and effort participants had to take. In so doing, participants could provide information with more ease. Still, another question required participants to rank the four skills of language learning in order of importance on the assumption that teachers might value a certain skill the most and another the least. This ranking question required teachers to decide what learning skill was most important to themselves. In addition to the formats mentioned, open-ended questions were employed in two items. 31.

(39) They were intended to allow participants to add extra opinions more freely. One of the two items was to investigate the methods which might enhance the efficiency of writing instruction. The other was to discover whether and why teachers agree or disagree that writing should be tested in entrance examinations. This tentative questionnaire was administered to four teachers and given to an expert for review and suggestions. More details about the design and results of the tentative questionnaire were also described in the following section. Finally, based on the results of and feedback on the preliminary questionnaire, the questionnaire was revised. The formats were then changed to some extent and the presentation of the questions was reorganized. As mentioned above, the question which required participants to rank the four language-learning skills in order of importance was broken down into four different questions. It was found in the preliminary study that some teachers considered some or all of the four skills of the same importance. Therefore, the original question was divided into four distinct questions so that teachers were required to examine the necessity of each learning skill for junior high school students separately. Besides, to avoid evoking teachers’ uncomfortable feelings about writing anything, the two open-ended questions mentioned above were changed into multiple choices, allowing teachers to tick more than one choice, whereas a space was still offered for extra opinions. Besides, four questions were turned into yes/no questions in consideration that more definite answers were needed. Teachers were expected to give definite answers to whether they gave writing instruction, whether their schools held composition contests, whether teachers referred to Competence Indicators, and whether there existed composition classes in their schools. Moreover, some questions which originally provided a 4-point response scale were now changed into a 5-point scale, adding a neutral or undecided answer. Take an example, for teachers who are not sure whether 32.

數據

Outline

相關文件

incorporating creative and academic writing elements and strategies into the English Language Curriculum to deepen the learning and teaching of writing and enhance students’

A genre is more dynamic than a text type and is always changing and evolving; however, for our practical purposes here, we can take genre to mean text type. Materials developed

Making use of the Learning Progression Framework (LPF) for Reading in the design of post- reading activities to help students develop reading skills and strategies that support their

- promoting discussion before writing to equip students with more ideas and vocabulary to use in their writing and to enable students to learn how to work in discussion groups and

To help students appreciate stories related to the theme and consolidate their knowledge and language skills in writing stories, the English Club has organised a workshop on story

Information technology learning targets: A guideline for schools to organize teaching and learning activities to develop our students' capability in using IT. Hong

- Teachers can use assessment data more efficiently to examine student performance and to share information about learning progress with individual students and their

Part 2 To provide suggestions on improving the design of the writing tasks based on the learning outcomes articulated in the LPF to enhance writing skills and foster