臺灣外?鳳頭鸚鵡 (Cacatua 屬) 野外族群現況

全文

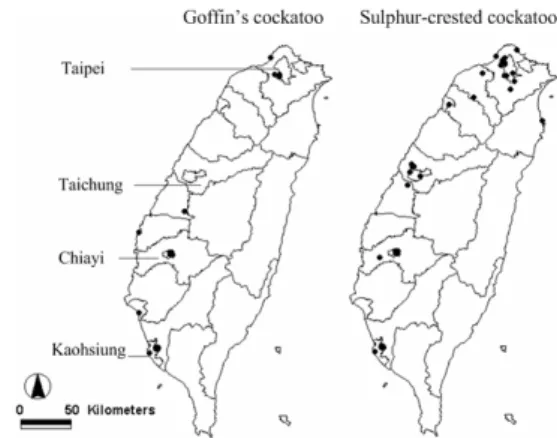

(2) September, 2006. Lin & Lee: Exotic white cockatoos in Taiwan. long-lasting bond, and keep in pair all the year around. Each year they return to the same nest used in previous years or nearby for breeding. Eggs take three to four weeks to hatch and the nesting period last for 7 to 14 weeks (Forshaw, 1989; Rowley, 1997; Juniper and Parr, 1998). Because it is essential to understand relevant ecological processes and to predict ecological and economic impacts of exotic species, the study of biological invasions is an important topic of current ecological studies (Drake et al., 1989; Lodge, 1993). Severinghaus (1999) reported six species found in Taiwan from 1994 to 1999, but no detail biological information was given. The purpose of this study is to determine the status of the exotic white cockatoos in Taiwan with respect to their distribution, abundance, population fluctuation, and invasion success.. MATERIALS AND METHODS The data on the distribution of white cockatoos in Taiwan from December 1986 to May 2000 were obtained from the observation database of the Wild Bird Federation Taiwan (WBFT). The data are consisted of species, dates, locations and numbers of birds observed. An assessment survey was conducted by the authors from September, 1998 to December, 2000 in the areas where the white cockatoos were recorded by WBFT and active bird watchers. Each site was surveyed at least once. When the birds were found, we recorded the species and their numbers. To determine the distribution of the white cockatoos, the data with accurate records of species and locations observed were compiled. We used those data with location accuracy that can be referred to a 2 km × 2 km grid system (Lee et al., 2004) established by Lee et al. (1996). In each grid the largest number of birds recorded for a species was used to represent the relative abundance of the particular species. Distribution maps were made using ArcView GIS 3.2 (ESRI, 1999). To illustrate the changes in abundance of the white cockatoos, the sites with data longer than five years and each year had observations longer than six months were used. The largest number of birds recorded for a species in each month was used to represent the relative abundance of that particular species in that particular month at that particular site. Based on the information, we established the population fluctuation profile of a species by plotting its relative abundance against months.. 189. RESULTS Based on the WBFT database, four species of cockatoos, i.e., Goffin’s Cockatoo (10 locations), Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (4 locations), Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (24 locations), and White Cockatoo (2 locations), were sighted in the wild in Taiwan. Most of the locations were near the cities and towns (Table 1). In most of these sites, the maximum number was smaller than three (50-75% for each species), but small flocks in numbers between three and 25 individuals were observed in some locations for the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (50%) and the Goffin’s Cockatoo (50%). The maximum number was 12 birds for the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and 25 birds for the Goffin’s Cockatoo at Cheng-Ching-Hu, Kaohsiung County. However, in our survey, we could only find three species, while the Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo was not detected. Based on occurrence records of the WBFT database, the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and the Goffin’s Cockatoo were frequently observed in the wild, but the populations for the Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and the White Cockatoo were rare. The distribution maps for the Sulphur-crested cockatoo and Goffin’s Cockatoo indicate that these two species occurred in the western coastal plain of Taiwan at elevations below 200 m in the vicinities of the major cities, including Taipei, Chiayi and Kaohsiung (Fig. 1). Some were found in the countryside. The two species shared similar habitats, such as parks, botanical gardens, school campuses, golf courses and woodlots, where there were large trees to provide food sources and holes for nesting and roosting.. Fig. 1. Distribution maps of the Goffin’s Cockatoo (C. goffini) and the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Cacatua galerita) in Taiwan from December 1986 to December 2000. The distribution for the the Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and the White Cockatoo were too few and thus omitted..

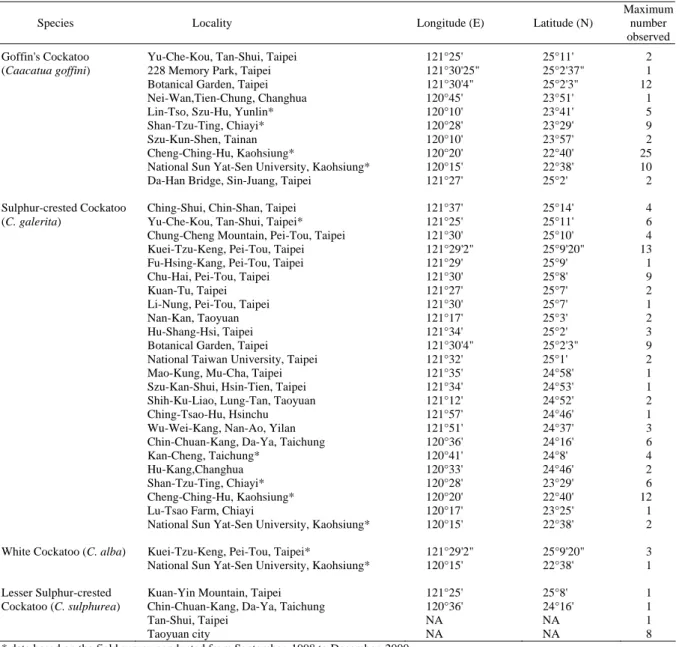

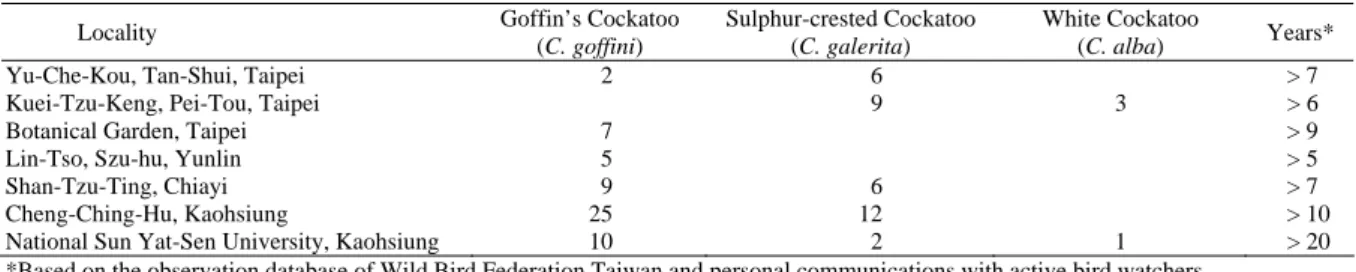

(3) 190. TAIWANIA. Vol. 51, No. 3. Table 1. Localities and the maximum numbers of exotic white cockatoos observed in Taiwan from 1986 to 2000 (data obtained from the Wild Bird Federation Taiwan database and a field survey between September, 1998 and December, 2000). Species. Locality. Longitude (E). Latitude (N). Maximum number observed. Goffin's Cockatoo (Caacatua goffini). Yu-Che-Kou, Tan-Shui, Taipei 228 Memory Park, Taipei Botanical Garden, Taipei Nei-Wan,Tien-Chung, Changhua Lin-Tso, Szu-Hu, Yunlin* Shan-Tzu-Ting, Chiayi* Szu-Kun-Shen, Tainan Cheng-Ching-Hu, Kaohsiung* National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung* Da-Han Bridge, Sin-Juang, Taipei. 121°25' 121°30'25" 121°30'4" 120°45' 120°10' 120°28' 120°10' 120°20' 120°15' 121°27'. 25°11' 25°2'37" 25°2'3" 23°51' 23°41' 23°29' 23°57' 22°40' 22°38' 25°2'. 2 1 12 1 5 9 2 25 10 2. Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (C. galerita). Ching-Shui, Chin-Shan, Taipei Yu-Che-Kou, Tan-Shui, Taipei* Chung-Cheng Mountain, Pei-Tou, Taipei Kuei-Tzu-Keng, Pei-Tou, Taipei Fu-Hsing-Kang, Pei-Tou, Taipei Chu-Hai, Pei-Tou, Taipei Kuan-Tu, Taipei Li-Nung, Pei-Tou, Taipei Nan-Kan, Taoyuan Hu-Shang-Hsi, Taipei Botanical Garden, Taipei National Taiwan University, Taipei Mao-Kung, Mu-Cha, Taipei Szu-Kan-Shui, Hsin-Tien, Taipei Shih-Ku-Liao, Lung-Tan, Taoyuan Ching-Tsao-Hu, Hsinchu Wu-Wei-Kang, Nan-Ao, Yilan Chin-Chuan-Kang, Da-Ya, Taichung Kan-Cheng, Taichung* Hu-Kang,Changhua Shan-Tzu-Ting, Chiayi* Cheng-Ching-Hu, Kaohsiung* Lu-Tsao Farm, Chiayi National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung*. 121°37' 121°25' 121°30' 121°29'2" 121°29' 121°30' 121°27' 121°30' 121°17' 121°34' 121°30'4" 121°32' 121°35' 121°34' 121°12' 121°57' 121°51' 120°36' 120°41' 120°33' 120°28' 120°20' 120°17' 120°15'. 25°14' 25°11' 25°10' 25°9'20" 25°9' 25°8' 25°7' 25°7' 25°3' 25°2' 25°2'3" 25°1' 24°58' 24°53' 24°52' 24°46' 24°37' 24°16' 24°8' 24°46' 23°29' 22°40' 23°25' 22°38'. 4 6 4 13 1 9 2 1 2 3 9 2 1 1 2 1 3 6 4 2 6 12 1 2. White Cockatoo (C. alba). Kuei-Tzu-Keng, Pei-Tou, Taipei* National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung*. 121°29'2" 120°15'. 25°9'20" 22°38'. 3 1. 121°25' 120°36' NA NA. 25°8' 24°16' NA NA. 1 1 1 8. Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (C. sulphurea). Kuan-Yin Mountain, Taipei Chin-Chuan-Kang, Da-Ya, Taichung Tan-Shui, Taipei Taoyuan city * data based on the field survey conducted from September, 1998 to December, 2000.. We identified seven permanent roosting sites that had been used by one or mixed species of Goffin’s cockatoo, Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and White Cockatoo for 5 or more than 20 years (Table 2). There were one site used by three species, four sites by two species, and one site by only one species. The maximum numbers of the white cockatoos at each of the roosting sites were recorded at the time when they flied in circle around the roost area or stayed on the top of high trees prior to settling on the roosting tree. At the campus of National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung City, the Goffin’s Cockatoo were. recorded only twice in the winters of 1998 and 1999, and were not found since then. Peitou, Taipei and Taipei Botanical Garden were the only two locations with sighting records extended at least of 5 years and each year had sightings longer than six months. Monthly relative abundance of the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo in Peitou from January, 1996 to October, 2000 (Fig. 2a), and the Goffin’s Cockatoo in the Taipei Botanical Garden from November, 1994 to May, 2000 (Fig. 2b) indicated that their abundance remained fairly stable with small population size. The monthly maximum flock sizes fluctuated from one to 13 birds for both species..

(4) September, 2006. Lin & Lee: Exotic white cockatoos in Taiwan. 191. Table 2. The permanent roosting sites of exotic cockatoos and the maximum number recorded at each site from late 1998 to 2000. Goffin’s Cockatoo (C. goffini) 2. Locality. Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (C. galerita) 6 9. White Cockatoo (C. alba). Yu-Che-Kou, Tan-Shui, Taipei Kuei-Tzu-Keng, Pei-Tou, Taipei 3 Botanical Garden, Taipei 7 Lin-Tso, Szu-hu, Yunlin 5 Shan-Tzu-Ting, Chiayi 9 6 Cheng-Ching-Hu, Kaohsiung 25 12 National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 10 2 1 *Based on the observation database of Wild Bird Federation Taiwan and personal communications with active bird watchers.. Fig. 2. Trends of relative population abundance of the Sulphurcrested Cockatoo (Cacatua galerita) from January, 1996 to October, 2000 at Pei-Tou (Kuei-Tzu-Keng), Taipei (a) and the Goffin’s Cockatoo (C. goffini) from November, 1994 to May, 2000 at theTaipei Botanical Garden (b).. DISCUSSION This study reported four white cockatoo species that had escaped from captivity and found in the wild in Taiwan. An analysis on the long term database maintained by WBFT indicated that the Goffin’s Cockatoo and the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo were more common than the White Cockatoo and the Lesser Sulphur-crested Cockatoo. These species occurred primarily in the vicinities of metropolitan cities of western Taiwan. Despite the earliest record of the feral white cockatoos was more than 20 years ago (pers. comm., Mr. Green J. Y. Ou, former president of Kaohsiung Wild Bird Society), we found they maintained relatively small, but stable, population with nest building activities by the Goffin’s Cockatoo, the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and the White Cockatoo in the wild. Despite the global introduction of birds has been highly non-random with respect to taxon, parrots are the one that is highly favored (Blackburn. Years* >7 >6 >9 >5 >7 > 10 > 20. and Duncan, 2001). Unquestionably, the source of feral populations of the white cockatoos in Taiwan is related with pet trade. In the 1994 survey for 164 bird shops in Taiwan, there were 26 species of exotic parrots, and almost all of the shops (94%) carried at least one species (Chi, 1995). Although the white cockatoos were not the most popular parrots in the bird shops, five species (included those four species reported in this study and the Salmon-crested Cockatoo) were carried by one-fifth of the shops (Chi, 1995). Except the Salmon-crested Cockatoo, the other four species had been found in the wild. Apparently, they were escaped from captivity or released deliberately by man. Most of the exotic white cockatoos were found in or around metropolitan cities, where most of the bird shops were located (Chi, 1995). Whenever the birds escaped, they were expected to be found in or near the cities. Some illegally imported cockatoos were released by smugglers before they were inspection by the custom at harbors (pers. comm., Mr. Green J. Y. Ou). Disturbed habitats such as parks and campuses, host poor species richness (Pimm, 1989), and have less taxonomically or functionally related species (Ehrlich, 1989) and less competition (Crawley, 1986). They might be more favorable for exotic species (Smallwood, 1994; Williamson and Fitter, 1996). Although the white cockatoos in their native ranges can be found in various habitats, such as forests, farmlands, mangroves, and suburban areas (Forshaw, 1989; Rowley, 1997; Juniper and Parr, 1998), these parrots did not occur in forest of Taiwan. White cockatoos have not invaded Taiwan successfully. One of the possible hypotheses for their performance is that the climate or environmental conditions are not comparable to their natural range (Brown, 1989; Duncan et al., 2003). Long (1981) also indicates that most parrots are not successful as introduced species and those successful cases occurred only in the peripheral areas of their native ranges. Another possible factor that limits the population growth of white cockatoos in Taiwan is their low breeding success Exotic.

(5) 192. TAIWANIA. species with multiple broods per season and large clutch sizes should have a higher probability of establishing their populations (Kolar and Lodge, 2001; Duncan et al., 2003). Most of white cockatoos bred between March and July in Taiwan, and their clutch size was 1-2 eggs (R. S. Lin, unpublished data). In addition, they can only raise one brood at most because they need three months to finish a complete breeding cycle (Forshaw, 1989; Rowley, 1997; Juniper and Parr, 1998). Consequently, they often lost their nests caused by bad weather which made their nesting holes as puddles and/or destroyed the trees that hold the nesting holes (R. S. Lin, unpublished data). In Hong Kong, geographically close to Taiwan, the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and the Goffin’s Cockatoo have also established feral populations (Viney et al., 1994; Carey et al., 2001). The Sulphur-crested Cockatoo were released probably as early as in 1941, and have certainly been augmented by more recent escapes or releases. Its population remained around 60 to 100 birds in recent years (Carey et al., 2001). Although there are some confirmed breeding records in the field, it is not certain whether the population is sustainable (Viney et al., 1994). Based on the case observed in Hong Kong, the future of these white cockatoos in Taiwan might share a similar trend. Comparing the performance of the white cockatoos to that of starlings and mynas in Taiwan (Lin, 2001), they were not very successful invaders. However, since the white cockatoos have a long life span and take two to five years to reach sexual maturity (Rowley, 1997), their populations might be able to increase if favorable conditions exist. Although there are some uncertainties for the white cockatoos populations to explode as invasive in the future, it is recommended to eradicate them at the time when their population sizes are small and localized (IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group, 2000).. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We want to express our deep appreciation to the Wild Bird Federation Taiwan for providing the sighting records, Mr. Green J. Y. Ou for providing first-hand observation information, Mr. Pao-Hua Liu for his assistances in the field, and Dr. Chu-Fa Tsai for critically reading on an earlier draft of the manuscript. The study was partially supported by National Science Council and Council of Agriculture, Taiwan.. LITERATURE CITED. Vol. 51, No. 3. Beissinger, S. R. and E. H. Bucher. 1992. Can parrots be conserved through sustainable harvesting? Bioscience 42: 164-173. Blackburn, T. M. and R. D. Duncan. 2001. Establishment patterns of exotic birds are constrained by non-random patterns in introduction. J. Biogeogr. 28: 927-939. Brazil, M. A. 1991. The birds of Japan. Christopher Helm, London, UK. p. 277. Brown, J. H. 1989. Patterns, modes and extents of invasions by vertebrates. In: Drake, J. A., H. A. Mooney, F. di Castri, R. H. Groves, F. J. Kruger, M. Rejmánek and M Wiliamson (eds.), Biological invasions: A global perspective. John Wiley and Son, New York, USA. pp. 85-109. Carey, G. J., M. L. Chalmers, D. A. Diskin, P. R. Kennerley, P. J. Leader, M. R. Leven, R. W. Lewthwaite, D. S. Melville, M. Turnbull and L. Young. 2001. The Avifauna of Hong Kong. Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, Hong Kong, China. p. 293. Chi, W. 1995. A survey of the bird shops in Taiwan. Green Consumer Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan. p. 58. (In Chinese) Coates, B. J., K. D. Bishop and D. Gardner. 1997. A guide to the birds of Wallacea. Dove Publications, Alderley, Queensland, Australia. pp. 337-338. Crawley, M. J. 1986. The population ecology of invaders. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. London, Series B, Biol. Sci. 314: 711-731. Drake, J. A., H. A. Mooney, F. di Castri, R. H. Groves, F. J. Kruger, M. Rejmánek and M. Williamson. 1989. Biological invasions: A global perspective. John Wiley and Sons, New York, USA. p. 550. Duncan, R. P., T. M. Blackburn and S. Daniel. 2003. The ecology of bird introductions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34: 71-98. Ehrlich, P. R. 1989. Attributes of invaders and the invading success: Vertebrates. In: Drake, J. A., H. A. Mooney, F. di Castri, R. H. Groves, F. J. Kruger, M. Rejmánek and M Wiliamson (eds.), Biological invasions: A global perspective. John Wiley and Son, New York, USA. pp. 315-328. ESRI. 1999. ArcView GIS 3.2. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., Redlands, California, USA. Forshaw, J. M. 1989. Parrots of the world. 3rd edn. Lansdowne Editions, Willoughby, New Southwales, Australia. pp. 134-149. IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group. 2000. IUCN guidelines for the prevention of biodiversity loss caused by alien invasive species. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. pp. 8-9..

(6) September, 2006. Lin & Lee: Exotic white cockatoos in Taiwan. Juniper, T. and M. Parr. 1998. Parrots: A guide to the parrots of the world. Pica Press, Sussex, UK. pp. 276-284. Kolar, C. S. and D. M. Lodge. 2001. Progress in invasion biology: Predicting invaders. Tree 16: 199-204. Lee, P.-F., T.-S. Ding, F.-H. Hsu, and S. Geng. 2004. Breeding bird species richness in Taiwan: distribution on gradients of elevation, primary productivity and urbanization. J. Biogeo. 31: 307-314. Lee, P.-F., Y.-S. Lin, P.-S. Yang, L. L. Severinghaus, L.-L. Lee, H.-C. Lee, K.-Y. Lue, W.-C. Wu, S.-B. Hong, L.-C. Juang, D.-C. Hsu and C.-H. Chen. 1996. A GIS distribution databank for wildlife in Taiwan. Council of Agriculture, Taipei, Taiwan. p. 30. (In Chinese with English abstract) Lever, C. 1987. Naturalized birds of the world. Longmans, London, UK. pp. 243-245. Lin, R.-S. 2001. The occurrence, distribution and relative abundance of exotic starlings and mynas in Taiwan. Endemic Species Research 3: 13-23. Lodge, D. M. 1993. Biological invasions: lessons for ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 8: 133-137. Long, J. L. 1981. Introduced birds of the world. David and Charles, London, UK. pp. 238-249.. 193. Pimm, S. L. 1989. Theories of predicting success and impact of introduced species. In: Drake, J. A., H. A. Mooney, F. di Castri, R. H. Groves, F. J. Kruger, M. Rejmánek and M Wiliamson (eds.), Biological invasions: A global perspective. John Wiley and Son, New York, USA. pp. 351-367. Robson, C. 2000. A field guide to the birds of south-east Asia. New Holland Publishers, London, UK. p. 284. Rowley, I. 1997. Family Cacatuidae (Cockatoos). In: de Hoyo, J., A. Elliott and J. Sargatal (eds.), Handbook of the bird of the world Vol. 4. Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain. pp. 245-279. Severinghaus, L. L. 1999. Exotic birds in Taiwan. Wild Birds 7: 45-58. (In Chinese) Sibley, C. G. and B. L. Monroe. 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of birds of the world. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA. p. 1136. Smallwood, K. S. 1994. Site invasibility by exotic birds and mammals. Biol. Conserv. 69: 251-259. Viney, C., K. Phillipps and C. Y. Lam. 1994. The birds of Hong Kong and south China. Hong Kong Government Printer, Hong Kong. pp. 132-133. (In Chinese) Williamson, M. and A. Fitter. 1996. The varying success of invaders. Ecology 77: 1661-1666..

(7) 194. TAIWANIA. Vol. 51, No. 3. 臺灣外來鳳頭鸚鵡 (Cacatua 屬) 野外族群現況 (1,2,4). 林瑞興. (1,3). 、李培芬. (收稿日期:2006 年 1 月 4 日;接受日期:2006 年 3 月 29 日). 摘. 要. 依據中華民國野鳥學會鳥類資料庫 1986-2000 年及本研究 1998-2000 年的野外評估 調查,在臺灣已有 4 種鸚鵡科 (Psittacidae) 外來鳳頭鸚鵡屬 (Cacatua) 鳥種的野外族群 出現。其中,戈芬氏鳳頭鸚鵡 (C. goffini) 及葵花鳳頭鸚鵡 (C. galerita) 較為常見。白 鳳頭鸚鵡 (C. alba) 及小葵花鳳頭鸚鵡 (C. sulphurea) 的數量則仍稀少。鳳頭鸚鵡以單 獨或小群出現於臺灣西部的都會區附近,夜間棲息的地點固定並曾發現 2~3 種鳳頭鸚鵡 棲息在一起。鳳頭鸚鵡的族群數量在引入後,並無明顯增加的趨勢。整體而言,外來鳳 頭鸚鵡並未成功入侵臺灣。 關鍵詞:鳳頭鸚鵡、外來種、分布、臺灣。. ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. 2. 3. 4.. 國立臺灣大學生態學與演化生物學研究所,106 台北市羅斯福路 4 段 1 號,臺灣。 行政院農委會特有生物研究保育中心,552 南投縣集集鎮民生東路 1 號,臺灣。 國立臺灣大學生命科學系,106 台北市羅斯福路 4 段 1 號,臺灣。 通信作者。Tel: 886-49-2761331 ext. 142; Email: rslin@tesri.gov.tw.

(8)

數據

相關文件

Wayne Chang National Changhua University of Education- Master of Math Michael Wen National Kaohsiung Normal University - Bachelor of Math Peter Sun National Kaohsiung

172, Zhongzheng Rd., Luzhou Dist., New Taipei City (5F International Conference Room, Teaching Building, National Open University)... 172, Zhongzheng Rd., Luzhou Dist., New

On the other hand Chandra and Taniguchi (2001) constructed the optimal estimating function esti- mator (G estimator) for ARCH model based on Godambes optimal estimating function

A study on the spatial orientation ability for sixth grader students of elementary school― using three-dimensional views (Unpublished master’s thesis). National

2 Center for Theoretical Sciences and Center for Quantum Science and Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan..

2 Center for Theoretical Sciences and Center for Quantum Science and Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan..

3級 2級 3級 2級 3級 2級 3級 2級 3級

260、260區 臺北市立美術館站 美術公園區 266、266區 明倫高中站、庫倫街口站、就業服務處站 圓山公園區. 72