高中英語教師寫作教學信念與實踐:質性個案研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Senior High School EFL Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs and Practices on Writing Instruction: A Qualitative Case Study. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English,. 政 治 大. National Chengchi University. 立. er. io. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. In Partial Fulfillment. of the Requirements for the Degree of. n. al. C Master h e nofgArts chi. by Min-Chih Chen December, 2012. i n U. v.

(3) Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Yi-Ping Huang, who patiently guided me through the obstacles during the entire research process. This thesis would not be completed without her valuable and insightful suggestions. Next, my thanks go to two participants in this study, Shelly and Jocey (pseudonyms), who allowed me to enter their classes and gave their support and advice to me. Third, I also appreciated the advice given by the committee members, Dr. Chen-kuan Chen and Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh, whose suggestions and encouragements. 政 治 大 graduate school— Jeremy, 立who served as the debriefer to review the whole study and. enabled me to better revise my thesis. Next, my heartfelt thanks go to my classmate at. ‧ 國. 學. provided me with useful suggestions. Last but not least, I would like to give my whole-hearted thanks to my parents and younger brother for their love and support that. ‧. build my confidence to conquer all the difficulties during the thesis writing process. It is. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. all of these people’s encouragements that made this thesis possible.. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(4) Table of Contents. Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................iii Chinese Abstract ......................................................................................................vii English Abstract .......................................................................................................viii Chapter 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................1 Background and Rationale of the Study ..........................................................1. 政 治 大 .......................................................................................3 立. Purposes of the Study ......................................................................................3 Definition of Terms. 2. Literature Review .................................................................................................5. ‧ 國. 學. Definition of Beliefs and Teachers’ Beliefs ....................................................5. ‧. Approaches to Beliefs about Language Learning ...........................................6. y. Nat. Research on English Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Classroom ..............8. er. io. sit. Teachers’ Beliefs about General English Teaching ........................................8 Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching Specific Field of Language .......................8. al. n. v i n C hBeliefs and Practices Research on Language Teachers’ on Writing engchi U. Instruction .......................................................................................................10 Various Approaches to Writing Instruction ....................................................10 Consistency between Belief and Practice .......................................................12 Factors Influencing Teacher’s Beliefs or Practices ........................................12 Contextual Factors Influencing Teachers’ Practices on Writing Instruction ..15 Framework of the Relationship between Teacher’s Beliefs and Practices .....18 Research Questions ..........................................................................................20 3. Methodology ........................................................................................................21 Research Design .............................................................................................21 iv.

(5) Participants and Contexts ...............................................................................21 Data Collection Method .................................................................................23 Semi-structured interviews ............................................................................24 Classroom Observations and Field Notes ......................................................26 Data Analysis .................................................................................................26 Validation .......................................................................................................27 Role of the Researcher ...................................................................................28 4. Findings and Case Analysis .................................................................................29. 政 治 大 Course Preparation ........................................................................................29 立. Shelly .............................................................................................................29. Writing Instruction in Class ...........................................................................30. ‧ 國. 學. Beliefs and Practices on Writing Instruction ...................................................31. ‧. Jocey ..............................................................................................................41. sit. y. Nat. Course Preparation ........................................................................................41. io. er. Writing Instruction in Class ...........................................................................42 Beliefs and Practices on Writing Instruction ...................................................42. al. n. v i n Ch Summary ......................................................................................................... 55 engchi U Contextual factors influencing teacher’s beliefs and writing instruction ......56 Shelly .............................................................................................................56 Jocey ..............................................................................................................64 5. Cross-Case Analysis and Discussion ...................................................................75 Research Question One .................................................................................75 Research Question Two ................................................................................77 Research Question Three ..............................................................................80 6. Conclusion ...........................................................................................................89 Summary of the Study ...................................................................................89 v.

(6) Pedagogical Implications ...............................................................................90 Limitations of the Study .................................................................................91 Suggestions for Future Research ...................................................................91 Conclusion .....................................................................................................92 References ................................................................................................................95 Appendices ...............................................................................................................101 A.. Teachers’ Interview Questions ............................................................................101. B.. Students’ Interview Questions ...........................................................................106. C.. Transcript Conventions ........................................................................................109. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(7) 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱:高中英語教師寫作教學信念與實踐:質性個案研究 指導教授:黃怡萍 博士 研究生:陳閔志. 論文提要內容: 過去研究著重於教師全方位的英語教學信念,關於英語教師個別技巧方面的教學. 政 治 大 質化研究方式探討兩位高中英語教師寫作信念及其課堂教學,同時分析學生相關 立 信念研究較為缺乏,因此本研究將重心擺在教師寫作信念的研究。本研究旨在以. 因素如何影響教師寫作信念及其課堂教學。研究對象包含兩位高中英語教師及八. ‧ 國. 學. 名學生。資料蒐集方式包含訪談、課室觀察、以及觀察筆記。研究結果顯示教師. ‧. 信念及其教學並非完全一致。部分不一致的原因主要在於學生行為、學習態度、. y. Nat. 英語程度、師生的學習背景不同、時間壓力,以及課堂人數多寡等情境因素。此. er. io. sit. 外,相較於之前研究所提及的情境因素,學生特質能為教師的教育帶來不同層面 的影響。總之,學生因素以及信念與教學的不一致可以幫助教師們反思教學的本. al. n. v i n 質,並且藉由情境化的調整,發展出更符合情境的教學方式。 Ch engchi U. vii.

(8) Abstract In the past, the research focused on English teachers’ general pedagogical beliefs while the research on specific beliefs was lacking. Hence, the current research put emphasis on English teachers’ pedagogical beliefs on writing instruction. The purposes of the current study were to investigate two senior high school English teachers’ beliefs and practices on writing instruction and how students’ characteristics influenced them. The participants were two senior high school teachers and eight students chosen from the teachers’ classes. Data collection methods included semi-structured interviews with. 政 治 大 partial inconsistency between the teachers’ beliefs and their instruction, mainly resulting 立 teachers and students, classroom observations, and field notes. The results indicated a. from students’ behavior, learning attitudes, students’ English proficiency, time pressure,. ‧ 國. 學. and class sizes. Also, students’ characteristics were found to have different types of. ‧. influence on teachers’ instruction compared to other contextual factors mentioned in the. y. Nat. previous research. In conclusion, students’ characteristics and the discrepancies between. er. io. sit. teachers’ beliefs and practices would help teachers reflect on the nature of their instruction and develop more contextually responsive teaching.. n. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i n U. v.

(9) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. Background and Rationale of the Study The amount of research on teachers’ beliefs, cognition, or knowledge has been increased rapidly over the past decades. In recent years, some studies in the second or foreign language teaching have claimed that teachers’ pedagogical systems, such as knowledge and beliefs, do have an effect on their teaching behaviors (Johnson, 1994,. 政 治 大 guided by their specific pedagogical beliefs in the ESL or EFL context. 立. Woods, 1996). The English teachers’ instruction behavior in the classroom may be. Despite the prevalence of research on teacher beliefs, most studies simply focus. ‧ 國. 學. on teachers’ beliefs in general instead of specific aspects of teaching, such as listening,. ‧. speaking, reading, and writing (Chung 2003; Lai, 2004; Liu, 2004; Lu, 2003). Borg. sit. y. Nat. (2003) argues that more emphasis on teachers’ beliefs about specific areas should be. io. er. made, since research related to those aspects is relatively underdeveloped, and most research focused only on grammar instruction. Similarly, in Taiwan, several studies. al. n. v i n C beliefs focus on EFL teachers’ general teaching (Kao, 2002; Liao, 2008; U h e nongEnglish i h c Lin, 2001), but only a few studies on specific fields of English teaching have been conducted, such as grammar and vocabulary (Chang, 2005; Chuang 2010). Among all specific English teaching beliefs, beliefs on writing instruction should be given more attention because lots of high school students regarded English writing as their most taxing subject (Li, 1992). This can be shown by the statistics in recent five years from College Entrance Examination Center (CEEC)—all of the high school students could only score an average of about 7 (the total score is 20 points) in English writing. The reason behind the frustrating outcome, according to Hsu (2005), was the modification on high school entrance exam. After the educational reformation 1.

(10) of Nine-Year Integrated Curriculum, the current Basic Competence Test (BCT) for Junior High School adopted multiple choices as the only type of questions. Therefore, this situation would lead to a washback effect that teachers and students in junior high school put their emphasis on reading instead of writing training. In other words, after students graduate, it may be possible that they could only gain the skills of reading instead of writing. After these students enter senior high school, it is difficult for them to write a complete English sentence, let alone an English composition. Thus, the modification in the exam might influence teachers’ teaching beliefs and writing. 政 治 大 received little attention (Wu, C. F., 2002; Wu, S. R., 2002), for writing skills is not as 立 instruction. Also, the quest of English teachers’ beliefs about writing instruction has. applicable as other three skills used in Taiwan. Consequently, the need for more. ‧ 國. 學. research on what teachers believe and how their beliefs impact their teaching in the. ‧. field of writing instruction is necessary.. y. Nat. Although teachers’ beliefs are thought to have an effect on their writing. er. io. sit. instruction, previous research on teachers’ beliefs has shown an inconsistency between what teachers believe and what teachers do (Kao, 2002). Major contextual factors. al. n. v i n C h (1) States’ educational causing the inconsistency might include: policies, including engchi U. washback effects (Chang, 2007; Hsu, 2005, Wu, 2006), (2) school authority factors, including insufficient class hour (Hsu, 2005; Kuo, 2004), and class sizes (Chang, 2007; Hsu, 2005; Lin, 2009), and (3) students’ characteristics (Chang, 2007; Kuo, 2004; Lai, 2004; Lin, 2009; Liu, 2004; Wu, 2006 ). Borg (2003) argued that contextual factors strongly impacted teachers’ beliefs and practices, especially those related to students (Chang 2000). For example, Johnson (1992) mentioned that several factors may influence teachers’ instructional beliefs and practices, and that half of them were related to students’ involvement, motivation, understanding, affective needs, and language skills. How students’ characteristics may impact teachers’ beliefs and 2.

(11) practices on literacy education, though significant, is insufficient (Chen, 2009), let alone the research on teachers’ beliefs about writing instruction. In addition, research on high school teachers’ belief mostly used quantitative research methods (Breen, 1991; Peacock, 2001), which have been criticized for not being able to reflect teachers’ practical or experiential knowledge (Borg, 2009). Thus, qualitative research methods become important in studying teacher beliefs. Since this study aims to get an in-depth understanding of how students’ characteristics might influence teachers’ pedagogical beliefs about writing, observations and interviews were. 政 治 大 Given the importance of understanding the influence of students’ characteristics 立. adopted as data collection methods.. on teachers’ beliefs and practices, this qualitative case study aims to explore two. ‧ 國. 學. in-service high school English teachers’ teaching beliefs about writing and how. ‧. students’ characteristics might influence their beliefs and practices.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Purposes of the Study. The importance of understanding the relationship between teachers’ writing. al. n. v i n C h the reasons behind beliefs and practices and discussing it provides the need for engchi U. conducting this research. In order to have an in-depth understanding of how the students’ characteristics might influence teachers’ pedagogical beliefs, a qualitative case study methodology was adopted to explore two in-service senior high school English teachers’ teaching beliefs and practices on writing instruction and how students’ characteristics may influence teachers’ beliefs and their classroom practices. Definition of Terms (1) Pedagogical beliefs about writing instruction Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs about writing instruction were defined as teachers’ 3.

(12) perceptions and knowledge about teaching of writing, (2) Practices about writing instruction Teachers’ practices about writing instruction were defined as teachers’ class preparation, teaching procedures, teaching instruction, materials used in class and the assignment. (3) Contextual factors In this study, Borg’s (1998) definition of contextual factors was adopted to refer to the social, psychological, and environmental realities of the school and classroom,. 政 治 大 policies, students’ characteristics and so on. 立. such as principals’ requirements, curriculum, classroom and school layout, school. (4) Students’ reaction. ‧ 國. 學. Students’ reaction was defined as the way students responded to teachers’. ‧. instruction or initiation of questions in class, such as verbal responses, facial. y. Nat. responses, and body gestures.. er. io. sit. (5) Students’ characteristics. Students’ characteristics referred to all the student-related factors that would. al. n. v i n C h such as students’ influence teachers’ beliefs and practices, gender, , motivation, engchi U. learning attitudes, English proficiency, learning backgrounds and students’ reaction.. 4.

(13) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW In this chapter, five themes relating to teaching beliefs and practices will be discussed. The first section defines teachers’ beliefs. The second section deals with different approaches to conceptualizing beliefs. The third one encompasses various approaches to writing instruction. The fourth one is concerning contextual factors influencing language teachers’ beliefs and practices on writing instruction. Conceptual frameworks of the relationship between teacher’s beliefs and practices will be. 政 治 大. discussed in the fifth section. Finally, the discussion of the literature will lead to the research questions.. 學. ‧ 國. 立. Definition of Beliefs and Teachers’ Beliefs. ‧. Beliefs were considered as a mental conception which consciously or. y. Nat. unconsciously guided our behavior or thoughts (Johnson, 1994; Rokeach, 1968, Sigal,. er. io. sit. 1985). In the previous literature, people’s assumptions or conceptions influencing how they interpreted things were regarded as beliefs (Pajares, 1992). Beliefs were formed. al. n. v i n C h and they would not early and tended to self-perpetuate, change due to time, schooling, engchi U or living experience (Calderhead & Robson, 1991; Goodman, 1988; Nespor, 1987; Nisbett & Ross, 1980; Poser et al., 1982; Schommer, 1990). Concluded from the previous research (Johnson, 1994; Rokeach, 1968, Sigal, 1985), beliefs were considered a mental construction which consciously or unconsciously guided our behavior or thoughts. Teachers’ beliefs could be referred to as teachers’ attitudes toward education, including schooling, teaching, learning, and students-related issues (Pajares, 1992). As Johnson (1994) mentioned, “teachers’ beliefs are considered to have a filtering effect on all aspects of teachers’ thought, judgments, and decisions” (p. 439). Tsui (2003) 5.

(14) defined teachers’ beliefs as teachers’ conception of teaching and learning, influencing their classroom instruction. In sum, teachers’ beliefs could be viewed as teachers’ perceptions about teaching and learning, and those beliefs may guide their instruction.. Approaches to Beliefs about Language Learning Three approaches, according to Barcelos (2003), were adopted to study language learning beliefs. The first one was the normative approach. The term “normative” was originally used in studies of students’ culture backgrounds, in which students’ culture. 政 治 大 quantitatively and viewed beliefs on SLA as indicators of students’ future behavior. 立. was an explanation for their behaviors in the classroom. The studies were conducted. The normative approach usually adopted questionnaires to investigate learners’ beliefs.. ‧ 國. 學. Among those who adopted the normative approach, Horwitz (1985) was credited with. sit. y. Nat. on beliefs because of its objectivity and generalizability.. ‧. adopting the Beliefs About Language Learning Inventory (BALLI) to conduct research. io. er. According to Wilkinson and Schwartz (1989), though the clarity and precision were two advantages in quantitative methods in the normative approach with the use of. al. n. v i n C hthe researchers could questionnaire and descriptive statistics, only identify learners’ engchi U beliefs through the paperwork. The actual emotional state may not be interpreted. through the statement in the questionnaire. Besides, there were different reasons behind the same behavior. The criticism led to the adoption of the metacognitive approach. The name of this approach was derived from the framework on metacognitive knowledge advocated by Wenden (1987). He proposed that students’ metacognitive knowledge may help them reflect on what they were doing and develop their potential for learning. Those who used the metacognitive approach usually adopted semi-structured interviews and self-reports to collect data. Some of the beliefs elicited through the metacognitive approach were different from those elicited through the 6.

(15) normative approach, for the metacognitive approach could elicit more information through interviews than that from the questionnaires. Wendon (1987) made a conclusion that various beliefs could lead to the development of “a more comprehensive and representative set of beliefs” (p.113). However, the meta-cognitive approach only focused on learners’ abstract thoughts, not examining beliefs under a certain context, leading to the third approach to explore language learning beliefs, that is, the contextual approach (Allen, 1996). The contextual approach, influenced by situated learning, put much emphasis on the. 政 治 大 considered to be interacted with learning contexts. Qualitative research and 立. interaction between learners’ beliefs and contexts. From this approach, beliefs were. interpretation were adopted in this approach. There were multiple ways of data. ‧ 國. 學. collection, which included case studies, classroom observation, diaries (Hosenfeld,. ‧. 2003), discussions, and stimulated recalls (Allen, 1996; Barcelos, 2000).. sit. y. Nat. In a nutshell, the normative approach analyzed the data through descriptive. io. er. statistics, in which beliefs were measured out of context. The metacognitive approach concentrated on the participants’ subjective judgment about themselves, inferring. al. n. v i n Cstatements beliefs from their intention and ofUbehavior. The contextual h e n ginstead i h c. approach described beliefs as embedded in participants’ contexts. In this study, the researcher relocated these approaches to examine teachers’ beliefs on writing instruction. Since the researcher considered students’ characteristics as main contextual factors that influence teachers’ pedagogical beliefs, the contextual approach was adopted to uncover the contextual influences on high school English teachers’ teaching beliefs on writing.. 7.

(16) Research on English Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Classroom This section discusses English teachers’ beliefs and practices in terms of: (a) teachers’ general beliefs about general English teaching and (b) teachers’ beliefs about teaching specific skills.. Teachers’ Beliefs about General English Teaching Regarding teachers’ beliefs about language teaching, most studies focused on the beliefs in general English teaching (Chang, 2003; Nien, 2002; Yang, 2003). For. 政 治 大 English teachers’ beliefs towards Communicative Language Teaching (CLT). In this 立 example, a study conducted by Liao (2003), who explored two senior high school. study, different data collection methods were used, such as teacher interviews and. ‧ 國. 學. classroom observations. The period of observation lasted five months. The findings. ‧. suggested that both participants held strong beliefs in CLT. However, they had to mix. sit. y. Nat. CLT and traditional methods in class instruction due to certain contextual factors, such. io. er. as limited instructional hours, a large class size, and the pressure of exams. Lee (2004) also conducted a qualitative study to investigate 12 public middle school EFL teachers’. al. n. v i n Cresults beliefs toward English teaching. The thatU middle school EFL teachers h e nindicated i h gc were reluctant to adopt the intended teaching methods because of the pressure of the monthly exams, students’ English proficiency gaps, and a large class size. From the. above research, it is concluded that contextual factors could hinder teachers’ realization of beliefs. Factors like students’ English proficiency, a large class size, or pressure of exams may discourage teachers from teaching in a way consistent with their ideal instruction.. Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching Specific Fields of Language Teachers’ specific beliefs on language teaching refer to teachers’ teaching 8.

(17) beliefs on a specific aspect of English teaching, such as listening, speaking, reading, and writing, which were regarded as important as general beliefs (Borg, 2003). However, relatively few studies have examined pedagogical beliefs on specific language aspects. Of the research conducted, most focus on grammar instruction (Chen, 2009, Farrell & Kun, 2008; Richards et al., 2001). Regarding grammar instruction, certain factors compelling teachers to teach contrary to what they believed were primarily concerning student expectations and preferences, as well as classroom management (see also Andrews, 2003; Borg, 1999).. 政 治 大 aspects. Wu (2002) examined the relationship between English teachers’ theoretical 立 In Taiwan, research also examined pedagogical beliefs on specific language. orientation and practices on reading instruction. The factors behind the incongruence. ‧ 國. 學. lied in the exams, students’ English proficiency levels and passive reaction from. ‧. students, which compelled teachers to change from a student-centered approach to a. y. Nat. textbook-centered one. Hsieh (2005) conducted a study aiming to investigate junior. er. io. sit. high school English teachers’ beliefs in grammar instruction. The finding suggested the belief-practice inconsistency was due to students’ limited English proficiency, which. al. n. v i n C hin class. Chuang (2010) made teachers abandon activities conducted another research engchi U to investigate English teachers’ beliefs and practices in grammar teaching in high. schools. The results indicated that there were mismatches between teachers’ beliefs and practices because of students’ limited English proficiency. After reviewing both foreign and domestic research dealing with teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and their practices, the researcher discovered that the research on the specific field, literacy instruction, may provide unique findings (Borg, 2003). Also, Tsui (2003) stated that while certain type of pedagogical knowledge was general to all subjects, the content of the subject could have an impact on the general pedagogical skills used by teachers. That is to say, previous research has been conducted on 9.

(18) teachers’ general beliefs, but the content of writing instruction may be unique, such as “focusing on form” or/and “brainstorming activities.” Therefore, it is pedagogically significant to examine teachers’ beliefs on writing instruction. Besides, we can find that certain factors, especially those related to student issues, such as students’ limited proficiency or passive learning attitudes, were constantly mentioned as reasons influencing teachers’ beliefs. Therefore, it was obvious that students’ characteristics play an important role in the modification of teachers’ beliefs and practices. But how the students’ characteristics may interact with. 政 治 大. teachers’ teaching beliefs needs more investigation.. 立. Research on Language Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices on Writing Instruction. ‧ 國. 學. Various Approaches to Writing Instruction. ‧. English teachers might adopt various approaches to writing instruction,. sit. y. Nat. including the product, process, and genre approach. This section discusses these. io. er. approaches in terms of their backgrounds, the content of courses, and roles of teachers.. al. n. v i n Ch Product approach. Influenced by behaviorism, Pincas (1982) regards learning as engchi U. “assisted imitation, and uses many instruction techniques, in which learners respond to a stimulus given by teachers” (p.153). Therefore, writing is viewed as being mainly about linguistic knowledge, and most of the instruction focuses on the appropriate use of vocabulary, conjunction words, and syntax from the product approach (Pincas, 1982). There are four stages within this approach: familiarization, controlled writing, guided writing and free writing. The familiarization makes learners realize certain features of texts, such as grammatical points and vocabulary usage. Later, learners practice the writing skills from controlled sentence patterns to free writing with increasing freedom. Teachers play the roles of dominators in this approach. In 10.

(19) conclusion, the product approach views writing as the knowledge about the language structure.. Process approach. As for the process approach, writing is viewed as language skill development, such as planning and drafting. This approach includes four stages: prewriting, drafting, revising and editing (Badger & White, 2000). The prewriting enables learners to brainstorm different topics of the text. At the drafting stage, learners select and construct the ideas from the brainstorming stage, leading to the first draft.. 政 治 大 groups. Finally, they edit and refine the text. Teachers play the roles of facilitators to 立 After the discussion, learners might revise the first draft either individually or in. draw out leaners’ potential. In the view of the process approach, writing skills are. ‧ 國. 學. unconsciously developed rather than consciously learned by learners. In conclusion,. ‧. the process approach views writing as the exercise of linguistic skills, and the. y. sit. io. er. facilitators.. Nat. development of writing is an unconscious process in which teachers serve as. al. n. v i n C h regards writingUas linguistic knowledge and Genre approach. The genre approach engchi. emphasizes the variation of writing within different social contexts, such as sales. letters, research articles, and reports (Flowerdew, 1993). There are three stages within this approach. The first one is reading and analyzing the genre of the text which learners are going to produce. Later, learners could practice relevant language forms and consider the social context of the text, such as the identity of the reader, or the purpose of the writing. Finally, learners produce a new text by themselves. In sum, genre approach sees writing as the knowledge about the language with the attention paid to the social purpose.. 11.

(20) Consistency between Belief and Practice Most literature has shown that English teachers’ beliefs on writing instruction were more or less inconsistent with their practices (Chang, 2007; Lin, 2009). However, not every study had the same results. Some studies showed that teachers’ teaching beliefs were partially consistent (Chen, 2009) or fully consistent (Spada & Massey, 1992) with their instruction. The following discusses the reasons behind the inconsistency and consistency. Mitchell (2005) and Feryok (2004) proposed that if teachers had more teaching experience, their beliefs would be more consistent with. 政 治 大 than beliefs acquired more recently. Richardson (1991) also claimed that less 立. classroom practices, because the deeply held beliefs would be applied more thoroughly. experienced teachers might have their beliefs constantly changed in practices. In 2011,. ‧ 國. 學. Woods suggested that more experienced teachers were likely to have more. ‧. experientially informed beliefs than relative novices, and beliefs modified by teaching. sit. y. Nat. experience might be expected to correspond with teaching practices. The beliefs of. io. er. experienced teachers in the case studies may have become more firmly embedded in their practices as the time went by. In conclusion, teachers’ teaching beliefs would be. al. n. v i n C hAs teachers gainedUmore teaching experience, solidified by their teaching experience. engchi their instruction would become more consistent with their beliefs.. After the discussion of the reasons behind the inconsistency, the factors influencing either English teachers’ beliefs or practices will be elaborated in the following sections.. Factors Influencing Teacher’s Beliefs or Practices After reviewing the previous research, the researcher categorized three kinds of factors influencing teachers’ beliefs or practices: schooling, professional coursework, and contextual factors. The following paragraphs would introduce them one by one. 12.

(21) Schooling. Schooling means the teachers’ learning experience when they were students. As Bailey mentioned in 1996, in-service teachers’ instruction or belief was strongly influenced by their school teachers when they were students. When they taught in class, they would consciously or unconsciously simulate or forfeit certain ways of teaching based on their positive or negative perspectives on their school teachers. Several studies have elaborated the positive influence of schooling on English teachers’ instruction, which means that teachers may adopt the way they were taught. 政 治 大 two secondary school teachers. The methods involved self-report inventories, 立. when they were students. For instance, Olson and Singer (1994) conducted a study on. interviews with teachers, and class observations. From two participant teachers’. ‧ 國. 學. interviews, both teachers expressed that their pedagogical beliefs and practices were. ‧. influenced by their schooling experiences. One teacher stated how she taught her. y. Nat. students was a reflection of the enjoyable experiences that she had in school, while the. er. io. teacher.. sit. other one would ask students to read more because of the influence from her 7th grade. al. n. v i n C impact In addition to the positive school experience may exert on English U h e nthat i h gc. teachers’ instruction, some schooling experience could have negative effects on either teachers’ beliefs or practices, making them adopt a new way of instruction. For example, Woods (1996) adopted interviews and class observation to examine eight ESL teachers who taught adult students and found one of the participants implemented communicative approach during instruction because of her early language learning experience. As this teacher’s several years of skill-based language learning experience in school had not enabled her to speak French, she formed a teaching belief that communicative approach was more beneficial to students. Another study based on the schooling experience of two female kindergarten teachers was conducted by Thomas 13.

(22) and Barksdale-Ladd (1997). One participant adopted a “whole language” approach because of her negative experience of phonics practice when she had been a student. Another participant believed in “skill-based” instruction, for she had not experience it in her early literacy experience. In summary, the schooling experience not only has positive effects but also negative ones on either English teachers’ beliefs or instruction.. Professional coursework. Professional coursework are courses that pre-service teachers. 政 治 大 teaching beliefs could be influenced by simulating or adjusting instructors’ ways of 立. have to take before they teach in class. During the training session, pre-service teachers’. teaching or changing their views toward teaching after training sessions (Almarza,. ‧ 國. 學. 1996; Brown & McGannon, 1998). Borg (1999) conducted a study in order to. ‧. understand English teachers’ beliefs on grammar instruction. After 15 hours of class. y. Nat. observations and interviews, Borg discovered that the most influential factor. er. io. sit. influencing participants’ pedagogical beliefs and practices was the training received in the teacher education program. During the training, the participant had been taught. al. n. v i n C h approaches which with the communicative and learner-center were reflected in his engchi U. instruction in class. Even when he faced students’ negative responses in class, these beliefs were not changed. Rueda and Garcia (1996) also conducted a study to examine whether different types of teacher training could cause different teaching beliefs and instruction. Participants included 54 English teachers. After coding the data from interviews and class observation, they found different instruction methods in the area of reading and assessment. The participants with the special education background believed that teacher’s responsibility was to pass knowledge to students. On the other hand, the qualified teachers preferred to guide learners to grasp meanings of the texts from their prior knowledge. As for assessment, the special education teachers tended to 14.

(23) adopted a skill-based approach, while the qualified teachers used a holistic approach. From the above literature, we could realize the influence of different types of teacher education on their beliefs and instruction.. Contextual Factors Influencing Teachers’ Practices on Writing Instruction English teachers’ writing beliefs are more or less inconsistent with their practices (Basturkmen 2011; Chang, 2007; Lin, 2009), because teachers’ beliefs may be influenced by certain contextual factors. Contextual factors, according to Borg (1998),. 政 治 大 as principals’ requirements, curricula, classroom and school layouts, school policies, 立. are social, psychological, and environmental realities of the school and classroom, such. students’ characteristics and so on. Several studies have claimed the primary of. ‧ 國. 學. contextual factors in teachers’ instruction (Fang, 1996; Borg, 2003; Lee, 2008).This. ‧. section will list major contextual factors influencing teachers’ practices on writing. y. Nat. instruction and then narrow the focus to the issues related to students.. er. io. sit. The contextual factors influencing teachers’ writing practices can be categorized into three main factors: (1) states’ educational factors (2) school authority factors (3). al. n. v i n students’ characteristics. ThreeCcategories will be discussed h e n g c h i U as follows:. States’ educational factors. Research has shown that states’ educational policies exert a significant influence on teachers’ practices on writing instruction. (Chang, 2007; Hsu, 2005; Wu, 2006). Educational policies refer to the official policies implemented by Ministry of Education, including washback effects, which may compel teachers to adjust their instruction to make students perform well on the exam. For example, Chang’s study (2007) aimed to investigate high school and junior college English writing teachers’ beliefs and practices. The instruments were background surveys for students and teachers, interviews with students and the writing teachers. Results 15.

(24) indicated that teachers’ beliefs and practices varied because of the test-oriented educational policy. As such, English teachers had to forfeit the communicative approach and turned to the product approach, putting emphasis on explicit vocabulary and grammar instruction, translation methods, memorization of vocabulary and model sentences in writing instruction. Similarly, Hsu’s study (2005) also showed that the test-oriented trend in education policy compelled teachers to change their instruction. School authority factors. Compared to state’s educational policies, school authority factors has less influence on teachers’ practices, teachers did not have to substantially. 政 治 大 in each school, including insufficient class hours (Hsu, 2005; Kuo, 2004), and class 立. adjust their ways of teaching. School authority factors mean certain policies drawn up. sizes (Chang, 2007; Wu, 2002; Lin, 2009). Wu (2002) examined the relationship. ‧ 國. 學. between English teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and practices. The factors behind the. ‧. incongruence lied in school curriculum design. Teachers had to abandon the process. sit. y. Nat. approach because of limited class hours. Lin (2009) presented a study to investigate. io. er. how English writing was taught in high schools in Taiwan. The result indicated that half of the teachers in the study showed a positive attitude toward the process approach. al. n. v i n of English writing. However, few ofCthem were willing toU h e n g c h i implement it due to the large class size.. Students’characteristics. Among those contextual factors, students’ characteristics are mentioned in almost every study, and should be viewed as one of the most significant factors influencing teachers’ practices. Students’ characteristics are defined as any issues related to students themselves. The students’ characteristics could be further classified. As Chen mentioned in his study (2005), factors related to students consisted of several categories: proficiency level (Chang, 2003; Wu, 2002), motivation (Lin, 2001; Nien, 2002), attitudes (Nien, 2002), needs (Chang, 2003), and gender (Chang, 16.

(25) 2003). Student’s English proficiency is defined as students’ knowledge of English and performance on the exam, and their proficiency levels would influence teachers’ practices, for teachers have to change their writing approach from a process approach to controlled writing (product approach) to meet students’ needs. Hsieh (2005) conducted a study aiming to investigate junior high school English teachers’ teaching beliefs and practices. The finding suggested that the belief-practice inconsistency was due to the limited proficiency of the students. Therefore, teachers had to adopt controlled writing while giving up the communicative approach. Likewise, Chuang. 政 治 大 in vocational high schools. The results indicated that there were mismatches between 立. (2010) conducted another research to investigate English teachers’ beliefs and practices. teachers’ beliefs and practices because of students’ proficiency. Teachers asked. ‧ 國. 學. students to practice sentence patterns instead of telling them to write the whole article. ‧. due to students’ low English proficiency.. y. Nat. As for students’ leaning motivation and attitudes, teachers may provide more. er. io. sit. teaching activities if students are willing to learn. For example, Nien’s study (2002) suggested that teachers had difficulty implementing the communicative approach. al. n. v i n because of students’ negative C attitudes and low motivation h e n g c h i U toward it, which forced teachers to adopt a traditional teaching approach, such as the grammar translation. method or the product approach. In Lin’s study (2001), teachers were supportive of using English to teach in class. However, due to students’ passive attitude toward teachers’ instruction, teachers had no choice but to adopt students’ mother tongue. When it comes to students’ needs, Chang (2003) mentioned that teachers believed the instruction should be adjusted according to students’ grade, for they realized students in different grade would have different learning objectives. For example, students in the twelfth grade were facing much exam pressure. Therefore, teachers would put their emphasis of instruction on how to help students get high 17.

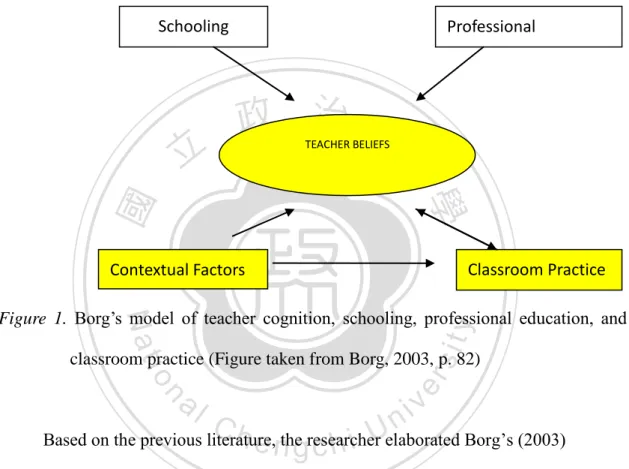

(26) scores in the exam. As for the influence of students’ gender, teachers would also supply more information in class when teaching girl students, for girls usually behave better than boys in class. In summary, contextual factors would change teachers’ practices on writing instruction, mostly from the process approach to the product approach. Among all the contextual factors, students’ characters played the most important role. Despite its significance, most of the previous studies have adopted the quantitative approach for examination, but it failed to reveal the complicated relation between beliefs and. 政 治 大 mentioning the influence they had on teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and practices on 立 instruction. Also, student’ characteristics have received little attention when. high school’s writing instruction. However, the educational reformation carried out ten. ‧ 國. 學. years ago has a huge impact on high school students’ English writing abilities, which. ‧. may probably influence high school English teachers’ beliefs and practices on writing. y. Nat. instruction. Therefore, this study aims to explore how students’ characteristics may. er. io. sit. influence English teachers’ beliefs and practices in a qualitative way.. al. n. v i n C hTeacher’s Beliefs and Frameworks of the Relationship between Practices engchi U. Borg’s model (2003) is adopted in this study, for his framework puts more. emphasis on the influence of the contextual factors. As shown in Figure 1, the central part of the model is teacher’s cognition, which encompasses belief, knowledge, theories, and so on. Around the cognition, four factors may influence or interact with it. They are schooling, professional coursework, contextual factors, and classroom practice. Schooling refers to teacher’s learning experience. Professional coursework means the courses which pre-service teachers have to take. Contextual factors represent social, psychological, and environmental realities of the school and classroom, such as principals’ requirements, curricula, school policies, students’ 18.

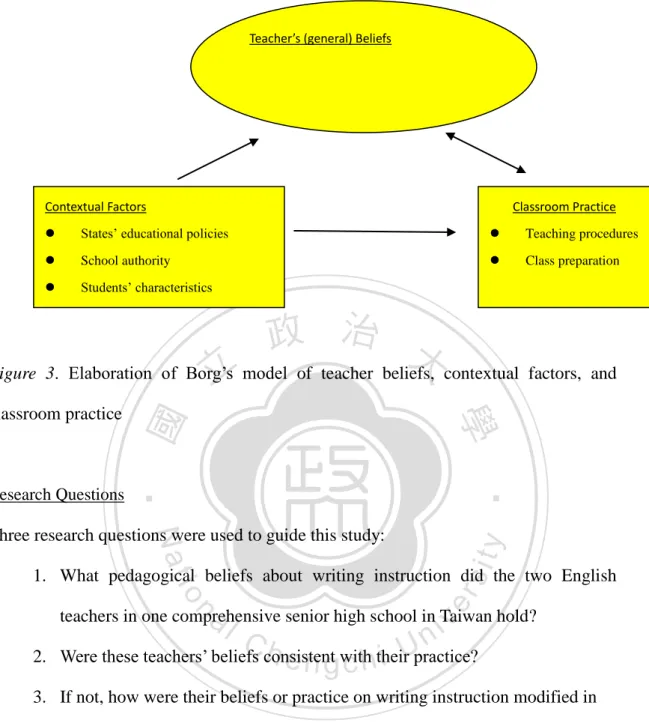

(27) characteristics and so on. Classroom practice refers to the way teachers teach in class, including their teaching procedure, class preparation and teaching materials, which are influenced by contextual factors. Since this study deals with the contextual factors behind teachers’ beliefs and practices, only part of Borg’s model, that is the relation among teachers’ beliefs, contextual factors and classroom practice will be examined.. Schooling. Professional Coursework. 立. 政 治 大 TEACHER BELIEFS. ‧ 國. 學 Classroom Practice. ‧. Contextual Factors. sit. y. Nat. Figure 1. Borg’s model of teacher cognition, schooling, professional education, and. n. al. er. io. classroom practice (Figure taken from Borg, 2003, p. 82). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Based on the previous literature, the researcher elaborated Borg’s (2003) illustrated in Figure 3. In this framework, the contextual factors include states’ educational policies, school authority, and students’ characteristics, while classroom practice involves teaching procedures and class preparation.. 19.

(28) Teacher’s (general) Beliefs. Contextual Factors. Classroom Practice. . States’ educational policies. . Teaching procedures. . School authority. . Class preparation. . Students’ characteristics. 政 治 大 students) Figure 3. Elaboration of Borg’s 立 model of teacher beliefs, contextual factors, and students’ characteristics. ‧ 國. ‧. Research Questions. 學. classroom practice. sit. y. Nat. Three research questions were used to guide this study:. n. al. er. io. 1. What pedagogical beliefs about writing instruction did the two English. i n U. v. teachers in one comprehensive senior high school in Taiwan hold?. Ch. engchi. 2. Were these teachers’ beliefs consistent with their practice? 3. If not, how were their beliefs or practice on writing instruction modified in the classroom? What contextual factors, especially students’ characteristics, might impact such modification?. 20.

(29) CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY. Research Design Since a qualitative case study can provide an intensive, complete description and analysis of a single entity (Duff, 2007), this study adopted the qualitative case study design to explore and observe two senior high school English teachers’ beliefs and practices in writing instruction and how their beliefs and practices on writing. 政 治 大. instruction might be shaped by students’ characteristics in the class contexts.. 立. Participants and Contexts. ‧ 國. 學. The current research was conducted in a medium-size public senior high school in. ‧. a metropolitan area in northern Taiwan. This school was chosen because among all the. sit. y. Nat. high school students in Taiwan in 2010, the students there got the average score in their. io. er. high school entrance exams, which made the school a typical case. There were 33 classes and 13 English teachers at this school. Each English teacher taught two to three. al. n. v i n Csix classes in one semester and had seven hours for each class every week. In 2011, U h eto n i h gc there were 20-week course of study and three monthly achievement tests. Each. achievement test included four lessons. There were about 35 students in each class. Both boys and girls were included. The students in this school were randomly assigned to each class. In class, students sit in rows and face the teacher in the same direction. There was a blackboard behind the teachers on the stage for them to write down the supplementary notes. Jocey and Shelly were two public senior high school female English teachers participating in this study. Shelly was chosen because she is a friend of the researcher. The other teacher was selected through snowball sampling (Glesne, 1999). Having 21.

(30) good reputation for writing instruction, Jocey was introduced by Shelly. Both teachers majored in English in college. Jocey taught more than 20 years in the same school, while Shelly had twelve years of teaching experiences and had taught in two different high schools before being transferred to the current school. In 2011, they taught two classes when the data were collected. Since both teachers taught in the same school, some conditions related to school, such as curriculum syllabi and school administration, were almost the same. They agreed to join in this study after the researcher explained the purpose of the current study. Table 1. shows the demographic information of the two participants.. 立. Demographic Information of Two Participants. 學 ‧. ‧ 國. Table 1. 政 治 大. Age length of teaching. teaching experiences. Female. 51. the current high school. Shelly Female. 34. y. sit. 26 years. io. al. n. 12 years. er. Jocey. Nat. Gender. 3 years in a private high school. v i n Ch in aU public girls’ high school i e n g1 year h c 8 years in the current high school. Aside from two English teachers, eight students were also interviewed to serve as a form of triangulation. Two students were chosen in each class based on teachers’ recommendation. Their name, sex, English proficiency, and the experience of learning English are described in Table 2.. 22.

(31) Table 2 Profile of Participating Students. Class. Name. Sex. English Proficiency Experiences. of. Learning English Jocey’s. Class A. Class Class B. Howard male. high. 12 years. Peggy. low. 10 years. medium. 9 years. female. Jennifer female. Shelly’s Class C. Edward. 政 low治 大 male medium. Class. Iris. female. high. Katrina. female. low. Jane. female. high. Jeremy. 10 years 11 years 12 years. ‧. Nat. Data Collection Method. io. sit. y. 9 years. er. Class D. 11 years. 學. ‧ 國. 立. male. al. v i n C h individually before interviews with each English teacher e n g c h i U and after the class observation, n. Data collection was derived from three main sources: (a) two semi-structured. (b) one individual interview with two students from each observed class and (c) classroom observation and field notes. Before data collection methods are discussed, the schedule of data collection is presented in Table 3:. Table 3 The Schedule of Data Collection. 2011. 23.

(32) 3/27. Pre-observation interview with Jocey (60 min). 4/04 ~ 5/13. Classroom observation (Class A, 39 hours) (6.6 hours on writing instruction). 4/05 ~ 5/13. Classroom observation (Class B, 38 hours) (5.9 hours on writing instruction). 5/21. Post-observation interview with Jocey (30 min). 5/22. Pre-observation interview with Shelly (60 min). 5/23 ~ 6/24. Classroom observation (Class C, 30 hours) (4.7 hours. 政 治 大 Classroom observation (Class D, 30 hours) (4.3 hours 立 on writing instruction). 5/23 ~ 6/24. ‧ 國. Post-observation interview with Shelly (30 min). 7/09. Students’ interview Class B (20min each ). 7/10. Students’ interview Class C (20min each ). 7/16. Students’ interview Class A (20min each ). 7/17. Students’ interview Class D (20min each ). ‧. 7/02. n. engchi. sit er. io. Ch. y. Nat. al. 學. on writing instruction). i n U. v. Semi-Structured Interviews Semi-structured interviews with two participating teachers were conducted before and after the class observation in 2011. Before the interview, two participating teachers’ course syllabi were reviewed to decide the time of the observation and interviews. There were two interviews with each teacher, one pre-observation interview and one post-observation interview in 2011. Each interview lasted about sixty minutes and was conducted individually to avoid interference between two participants. Besides, all interviews were recorded and transcribed.. 24.

(33) The purpose of the pre-observation interview was to know a) the participants’ learning and teaching backgrounds, b) their pedagogical beliefs toward writing instruction, and c) the students’ involvement during the class. The first teacher interview protocol was developed based on Carspecken (1996), including four topics, each of which contained one lead-off question and a few follow-up questions. Lead-off questions were served as a guide for later follow-up questions. The topics of the first interview were based on Glesne’s interview techniques (1999), (See Appendix A). They included teachers’ personal backgrounds, beliefs about writing, opinions about. 政 治 大. students’ influence on teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and practices, and techniques to writing instruction.. 立. On the other hand, the post-observation interviews were conducted after the. ‧ 國. 學. whole observation. The purpose of this interview was to understand teachers’. ‧. decision-making processes, and how students and other factors might influence these. sit. y. Nat. processes. Each interview lasted about thirty minutes. Based on the suggestions made. io. er. by Hsu (2005), Kao (2002), Wu (2006), the topics of the interview included some incidents happening in the classroom, the decision made when both participants were. al. n. v i n teaching, and some questions C derived from the pre-observation interview. (For the hengchi U questions of this interview, please refer to Appendix A ). After two interviews with the teachers, interviews with students from both teachers’ classes were conducted for the purpose of triangulation. The purpose of the interview was to understand students’ impression on teacher’s writing instruction. Two students from each observed class were chosen based on the teachers’ recommendations. In this study, eight students from four classes were interviewed after the class observation was done. One student was interviewed at a time to avoid interference from other classmates. Each interview lasted about 20 minutes. The reason why students’ interview was held in July was that they had much free time during 25.

(34) summer vacation. The topics of this interview were adapted from Nien’s (2002) study. A student interview protocol (see Appendix B) was developed based on Carspecken (1996). All the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.. Classroom Observations and Field Notes In this study, two English teachers were observed from April to June, Monday to Friday, in the spring semester of 2011 (137 hours in total, in which 21.5 hours belonged to writing instruction). To avoid the conflicts between both teachers’ course. 政 治 大 Shirley’s class from May to June. Both classes of each participating teacher were 立. schedules, the researcher observed Jocey’s class from April to May and then observed. chosen for observation because each teacher taught two classes. Therefore, there were. ‧ 國. 學. total four classes (Class A, B, C and D) observed by the researcher. Class A and B were. ‧. taught by Jocey, while Class C and D were taught by Shelly. The whole class. sit. y. Nat. observation was recorded through video camera and field notes. The researcher did not. io. er. participate in the process of instruction, only as an observer, recording those events related to the research questions. The field notes included any events and activities. al. n. v i n C hthose related to theUstudents’ characteristics happening in the classroom, especially engchi when writing was taught, without any personal interpretation.. Data Analysis Data gathered from the interview with teachers and students were audio-taped and transcribed and then coded based on content analysis proposed by Lieblich (1998). The purpose of using content analysis was to analyze interview data and investigate participants’ perspectives. After the verbatim transcription, the researcher translated the data from Chinese to English and then picked out the data which were related to the teachers’ writing beliefs and practices. Those data were categorized after the contrast 26.

(35) and comparison, and then recurring themes would be chosen. After that, the recurring themes were classified into certain content categories. As for the class observation, the researcher wrote down field notes during the class and watched the recording after class to gather the information related to (1) teachers’ instruction, (2) what teachers said in class (such as initiating questions), (3) students’ responses, and (4) students’ expression. Finally, compare and contrast the data from the observation and the content categories from the interview data to get several new content categories to reach a conclusion.. 立. 政 治 大 Validation. To establish the trustworthiness of this study, several procedures were adopted. ‧ 國. 學. (see Lincoln & Guba, 1985). First, pre-observation interviews with both participants. ‧. were triangulated with class observation and the interview with the students. Through. y. Nat. the pre-observation interview, the researcher knew the pedagogical beliefs on writing. er. io. sit. instruction held by the teachers. Then, the class observation of teachers’ writing activities was used as the evidence to prove the beliefs that teachers mentioned in the. al. n. v i n C hgathered in the field previous interview. Also, the data notes, post-observation engchi U. interviews with teachers, and the interview with students could be used to realize the students’ involvement and the reasons behind the decision making process. The interview with the students could also be a supplement for the researcher to understand the influence of students’ characteristics on teachers’ beliefs and practices on writing instruction from another perspective. The second procedure was member check. The selected data from the field notes and the interviews were checked by the participating teachers to see if there was any misunderstanding between the researcher and the teachers. Finally, peer debriefing was also involved in this study. According to Lincoln and Guba (1985), a debriefer is an individual who keeps the researcher honest and asks 27.

(36) questions about methods, meanings, and interpretations. From an outsider’s viewpoint, the debriefer checked the research process to clarify the ambiguity or something inappropriate. Jeremy, a classmate of the researcher, was asked to be the peer debriefer in the whole study.. Role of the Researcher During the observation, the researcher played the role as an observer to avoid interfering the teaching process in class; meanwhile, he also tried to learn from the. 政 治 大 enabled the researcher to reflect on all aspects of research procedures and findings. 立. participants instead of being an expert or an authority figure. The learner’s perspective. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 28. i n U. v.

(37) CHAPTER 4 FINDINGS AND CASE ANALYSIS. The purpose of the study is to gain an in-depth understanding of two senior high school English teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and practices on writing instruction and how students’ characteristics may influence their instruction. The analysis of Shelly’s and Jocey’s pedagogical beliefs and practices is presented in the following sections. Also, students’ opinions are included to realize how they viewed the instruction.. 政 治 大. Finally, factors that would influence teachers’ instruction will be discussed.. 立. Shelly. ‧ 國. 學. In this section, Shelly’s pedagogical beliefs on writing instruction and the way. Nat. sit. y. ‧. she taught in the classroom will be discussed.. io. er. Course Preparation. Shelly used the textbook and several articles extracted from English magazines. al. n. v i n Cteaching, as materials. In her first year of a great amount of time reading the h e n gshecspent hi U textbook, analyzing texts, searching the supplementary information from reference. books or the Internet, such as synonym, relative word groups, and derivatives. After years of teaching, Shelly has spent less and less time on the textbook, for she had been familiar with the content in the textbook, and the content has been taught over and over again. However, the preparation of supplementary materials was another story. Since Shelly hoped that the materials could make students realize the events happening in the world and connect what they have learned in class with their daily lives, she found the related articles from the latest magazines. After reading them, Shelly pinpointed certain key points, such as word usage, sentence patterns, and derivatives for students to notice. 29.

(38) In sum, the textbook was used as the main source of writing instruction, while articles related to the current events served as the supplementary materials to improve students’ writing abilities. As for the development of the instructional procedure, Shelly admitted that she did not spend much time on that because of her years of teaching experience in high school. Before stepping on the platform, she completely had in mind what she was going to teach. The only thing she insisted on was that sentence patterns must be taught bottom up, which meant they should be disassemble at first, and then each segment. 政 治 大 pattern. By doing so, Shelly believed it was easier for students to follow her 立. would be explained. Finally, each segment was combined to form a complete sentence. instruction.. ‧ 國. 學. In sum, Shelly did spend a great amount of time preparing writing materials,. ‧. including the content in the textbook and English articles in the past. However, the. sit er. io. Writing Instruction in Class. y. Nat. time for class preparation has decreased as she becomes more and more experienced.. al. n. v i n Cthat When interviewed, Shelly said a fixed U writing instruction procedure h eshenhad i h gc. for every lesson. First, she explained the sentence patterns and then asked students to. finish the drills on the textbook. Next, the articles Shelly gave students in the previous class would be discussed and key points were pinpointed. For the teacher, the article reading was thought to be helpful in learning writing, which will be elaborated in the next section. After class, an assignment was assigned to each student to make three sentences based on what they have learned today. However, she also acknowledged that there was an inconsistency between her beliefs and practices on writing instruction. Ideally, Shelly thought that certain activities should have been included, such as brainstorming, group discussions and revising. The activities could make students 30.

(39) realize that language could be served as a tool to communicate with others (e.g. writing a letter), rather than merely a subject learned in class. However, she had difficulty carrying out her ideal teaching methods because of students’ inappropriate behavior and time limitation. The goals of her instruction, according to Shelly, were to enable students to understand the connection between the language they learned and their surroundings. For her, writing instruction included extensive reading, sentence-pattern teaching and practices.. 政 治 大 Data collected from Shelly’s statements could be categorized as the following 立. Beliefs and Practices on Writing Instruction. teaching beliefs and practices on writing instruction: (a) Learning L2 is like learning. ‧ 國. 學. L1, (b) sentence patterns should be taught by using bottom-up strategies, (c) practice is. ‧. essential when teaching sentence patterns, and (d) instruction should be adjusted. er. io. sit. y. Nat. according to different students.. Learning L2 is like leaning L1: Reading comes before writing. Shelly believed. al. n. v i n C Chines, learning English is like learning meant reading came before writing. U h e n which i h gc. Therefore, she thought the key to successful writing instruction was extensive reading across various topics, which was correspondent to Borg’s model (2003) that teachers’ beliefs could influence their instruction. During the interview, she told the researcher that the process of learning a second language should be similar to that of learning our mother tongue; that is, we learned how to listen before we knew how to speak. Further, through learning letters, words, and sentence patterns, we could read. After accumulating enough input, we could write. Likewise, for Shelly, the situation remained the same when we learned English in Taiwan: reading should be learned before writing. Therefore, according to Shelly, “lots of reading materials should be 31.

(40) provided before asking students to write an article.” In the following paragraph, how Shelly realized the importance of extensive reading will be discussed. Shelly realized the importance of extensive reading when she was in college. There were lots of reading assignments each class. Most of the students did not finish them. But Shelly did the assignments every time, for she loved reading English, which also indirectly improved her writing skills. She stated the special experience to the researcher.. 政 治 大 professors often reminded me of practicing writing on my own for the 立. When I was a freshman, I spent a lot of time reading the textbook. Therefore,. purpose of taking the mid-term exam, which was full of open-ended. ‧ 國. 學. questions. But I didn’t. Possibly because I had no interest in writing. When. ‧. the mid-term came, I thought I was unable to answer the questions. To my. sit. y. Nat. surprise, I smoothly finished the test without difficulties. The score of the. io. er. test was also pretty high. I guessed it was a large amount of reading that made me write smoothly even I did not practice beforehand. (Interview. n. al. 052211). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. According to Shelly’s statements, we found Shelly believed the extensive reading could improve writing skills, so she could write smoothly during the exam even though not practicing writing in advance. But Shelly also acknowledged that her personal experience may not be generalizable to others, especially her students. As a teacher, she thought successful writing instruction should include both extensive reading and practice, which will be further discussed in later paragraphs. She did not need to practice, according to Shelly, might be because of her solid foundation of English proficiency in high school as well as her large amount of reading input in 32.

(41) college, which made her a unique case. In other words, her personal experience triggered the thoughts that extensive reading could improve writing, but not everyone could write smoothly without practice as she did. After becoming a teacher, Shelly did some research and found out how to improve students’ writing skills by extensive reading. According to her viewpoint, extensive reading could increase not only students’ linguistic knowledge, such as sentence patterns, but also their background knowledge of writing. “If they (students) do not read a lot, they have no idea what to write when randomly given a topic during. 政 治 大 every day, and then she would lead students to review the key points in next class. The 立 the exam,” Shelly explained. Accordingly, Shelly gave each student an article to read. following excerpt shows how she utilized extensive reading in class to improve. ‧ 國. 學. students’ writing abilities. (See Appendix C for transcription conventions). er. io. sit. y. ‧. Ss: Yes…. Nat. S: Have you read the article I gave you yesterday?. S: It is about Japanese Girl’s Day. Take a look at the first paragraph. Here are some. al. n. v i n Cword words you should notice: the in line two, “in celebration of” in the h e“observed” ngchi U next line, and “do so” in the last line. Let’s take a look at the first paragraph, the. word observe meant celebrate rather than check. The next one is in celebration of, the usage of which is similar to to celebrate plus verb. Next time, you could try to use that instead of to celebrate plus verb in your articles. The final one is do so. It replaced study hard in the sentence to avoid repetition. Of course, it is correct to write study hard, but it sounds a bit redundant. Ok, let’s look at the next paragraph…. In the above excerpt, the process of instruction was clearly displayed. Before class, Shelly gave each student an article to read. But because of time limitation, she 33.

(42) could not lead students to read the whole article. Instead, Shelly expected her students to read articles on their own. In class, she told them certain crucial word usage they should notice. In the above example, she pointed out another meaning of “observe,” another expression of “to celebrate,” and the usage of “do so” to represent the mentioned verb phrase. In conclusion, Shelly carried out her beliefs by making students read articles and pinpointed the key points for students to notice. When it comes to choosing the articles, there were two requirements for them to meet. The first one was that those articles should meet students’ English proficiency.. 政 治 大 that the topics of articles were related to current events. Shelly explained, “Since the 立 They were selected from English magazines sold in book stores. The other one was. content on textbooks was out of date, students had problems understanding the. ‧ 國. 學. practicality of language learning.” Therefore, the topics included festivals, sports. ‧. events, adventure stories, and some movies currently released in theater. “I think it is a. y. Nat. good way to let students understand what they have learned in class could be. er. io. sit. connected with their daily lives.” Shelly’s students also have the same viewpoints. Edward, one of students in class C, said to the researcher, “I enjoyed reading those. al. n. v i n C hmaking me realizeUwhat had happened in the articles, for them broaden my horizons, engchi world.” Another student, Iris, also expressed her thoughts: “I am a moviegoer, and I. enjoy reading the movie introductions in the article. At the same time, I could improve my reading ability.” From students’ points of view, it is clear that interesting topics are served as incentives for students to study English.. Sentence patterns should be taught by using bottom-up strategies. Shelly suggested that sentence patterns should be taught piece by piece and then combined those pieces to form a complete pattern. During the interview, Shelly said that sentence patterns played an essential role for constructing an article, for an article consisted of several 34.

(43) paragraphs, and a paragraph was composed of several sentences. Therefore, being familiar with sentence patterns was indispensable when writing an article. That is, Shelly expected students to be familiar with the patterns taught in class and be able to use them in their writings. When teaching sentence patterns, Shelly broke the whole sentence pattern into several parts, explaining each of them. Finally, she combined each part to form a whole sentence pattern. For example, in Lesson Seven, Shelly set up her goal for writing instruction as making students be familiar with the sentence pattern “what + (S) + V,” which meant a noun clause led by what. In order to help. 政 治 大 elaborated on the noun clause. Next, she described the function of the composite 立 students easily understand the pattern, Shelly first analyzed the pattern and then. relative pronoun “what.” Finally, she combined “what” and “noun clause” as a. ‧ 國. 學. complete sentence pattern. Shelly explained why she spent extra time analyzing the. ‧. sentence patterns as follows:. sit. y. Nat. io. er. A sentence is combined with several words or small patterns. Like the above example, noun clause is involved in a noun clause led by “what.” If students. al. n. v i n Cclause, don’t understand the noun definitely have difficulties picking up U h e nthey i h gc the whole patterns. (Interview 070211). In the above statement, Shelly indicated the importance of teaching sentence patterns piece by piece, for students had to initially understand the individual words and then the whole patterns. However, she claimed that there were two main reasons that many teachers did not disassemble the sentence patterns as she did. The first one lied in that teachers thought it a waste of time. Due to the limited time distributed in English classes, teachers had to figure out how to cram their instruction in the intensive schedule. Therefore, they would teach sentence patterns directly by explaining the 35.

數據

相關文件

To enable the research team to gain a more in- depth understanding of the operation of the Scheme, 40 interviews were conducted, including 32 in eight case study

How would this task help students see how to adjust their learning practices in order to improve?..

For the more able students, teachers might like to ask them to perform their play to an intended audience as an extended activity. The intended audience might be a primary

To ensure that Hong Kong students can have experiences in specific essential contents for learning (such as an understanding of Chinese history and culture, the development of Hong

In the third paragraph, please write a 100-word paragraph to talk about what you’d do in the future to make this research better and some important citations if any.. Please help

In order to understand the influence level of the variables to pension reform, this study aims to investigate the relationship among job characteristic,

The objects on orange orbits (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) rotate around the sun.. Johannes Kepler, Weil, Württemberg

In order to solve the problems mentioned above, the following chapters intend to make a study of the structure and system of The Significance of Kuangyin Sūtra, then to have