On: 28 April 2014, At: 15:16 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The International Journal of Human

Resource Management

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rijh20

General ethical judgments, perceived

organizational support, interactional

justice, and workplace deviance

Na-Ting Liu a & Cherng G. Ding ba

Department of Business Administration , Ming Chuan University , Taipei , Taiwan, ROC

b

Institute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University , Taipei , Taiwan, ROC

Published online: 08 Sep 2011.

To cite this article: Na-Ting Liu & Cherng G. Ding (2012) General ethical judgments, perceived organizational support, interactional justice, and workplace deviance, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23:13, 2712-2735, DOI: 10.1080/09585192.2011.610945

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.610945

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

and-conditions

General ethical judgments, perceived organizational support,

interactional justice, and workplace deviance

Na-Ting Liua* and Cherng G. Dingb

a

Department of Business Administration, Ming Chuan University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC;bInstitute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC This study focused on the relationships between individual differences in ethical judgments and workplace deviance. In addition, the moderating roles of perceived organizational support (POS) and interactional justice (IJ) on the relationships were investigated. The results indicated that the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities and passively benefiting at the expense of others were positively related to interpersonal and organizational deviance. The judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions were positively related to interpersonal deviance only. For the moderating effects, the higher the POS, the weaker the influence of the judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions on interpersonal deviance; the higher the IJ that an employee perceived, the weaker the influence of the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others on interpersonal deviance. Some managerial implications were also discussed.

Keywords:ethical judgments; interactional justice; perceived organizational support; workplace deviance

Introduction

Workplace deviance, referring to ‘voluntary behavior that violates significant organizational norms and in so doing threatens the well-being of an organization, its members, or both’ (Robinson and Bennett 1995, p. 556), has received increasing attention (e.g. Robinson and Bennett 1995; Bennett and Robinson 2003; Colbert, Mount, Harter, Witt and Barrick 2004; Liao, Joshi and Chuang 2004). This behavior is concerned with voluntary behavior in that employees either lack motivation to conform to or become motivated to violate normative expectations of the social context (Kaplan 1975). Several workplace deviance frameworks distinguish between behaviors directed at individuals and at organizations and this two-factor structure has been empirically supported (e.g. Robinson and Bennett 1995; Bennett and Robinson 2000; Vardi and Weitz 2004). Interpersonal deviance refers to actions taken against individuals (bosses, coworkers, or customers) in the workplace and includes political deviance (e.g. gossiping about coworkers) and aggression (e.g. verbal abuse). Organizational deviance refers to actions taken against the company and includes production deviance (e.g. leaving early and procrastinating) and property deviance (e.g. stealing from the company).

Past research has studied the reasons for employees about engaging in ‘bad behavior’ in organizations, including antisocial behavior (Giacalone and Greenberg 1997), workplace aggression (Baron and Neuman 1996), retaliatory behavior (Skarlicki and Folger 1997), and workplace deviance (Bennett and Robinson 2003). These studies have

ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online

q2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.610945 http://www.tandfonline.com

*Corresponding author. Email: nating.liu@gmail.com Vol. 23, No. 13, July 2012, 2712–2735

revealed what motivates or inhibits unethical behavior. Causes or predictors of ‘bad behavior’ include personal factors (e.g. personality traits) and situational factors (e.g. justice perceptions). Although many factors influence when and how an individual decides to engage in improper behaviors or those outside normal conventions of acceptability, the relationship between individual differences in moral thought/judgment and such behaviors in organizations has seldom been addressed.

This study examines whether ethical factors are a significant determinant of deviant behaviors in organizations. Specifically, this study seeks to explore whether individual ethical judgments will be a determinant of workplace deviance. Ethical judgments refer to an individual’s subjective probability beliefs in which he or she considers various ethically questioned behaviors, moral rightness or wrongness (e.g. Chan, Wong and Leung 1998; Muncy and Eastman 1998). Because workplace deviance involves ethically questionable activities (Henle, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz 2005), employees will vary in their decisions to engage in these activities by different ethical judgments. Individuals with higher ethical beliefs in preserving the personal well-being of others would refrain from any actions or decisions that could potentially harm others. When employees have lower ethical standards in judging the acceptability of questionable actions, they are more likely to violate organizational norms. Thus, employees’ ethical judgments may influence deviant behavior in the workplace. However, ethical judgments may not perfectly explain the causes of unethical behaviors (Fukukawa 2002). For instance, even if an employee perceives one form of organizational deviance, withholding effort, as unethical, he or she may still do so if his or her fairness perception is low. This is one of many cases where ethical judgments may not be reflected in behavior. When studying workplace deviance, researchers tend to focus on either situational perceptions or personal characteristics, but as Sackett and DeVore (2001, p. 161) indicated, ‘A full understanding of counter-productive behavior requires both domains.’ This study extends the relationship between individual ethical judgments and morally questionable behaviors (i.e. workplace deviance) by including the moderating forces of two situational perceptual variables, perceived organizational support (POS), and interactional justice (IJ). For employees having positive perceptions of work situation, which can constrain deviant decisions, lower ethical beliefs may not lead to more deviant behaviors. Understanding the role of employees’ perceptions of the work situation on the relationship of their ethical judgments and their workplace deviance will help managers identify, predict, and explain when employees are likely to behave ethically or unethically at work.

Henle et al. (2005) have studied the relationship between ethical ideology and workplace deviance. They found that ethical ideology was a significant predictor of workplace deviance. Ethical ideology is an individual’s preferred moral philosophy measured on two dimensions: idealism and relativism (Forsyth 1980, 1992). Idealism refers to the degree to which an individual believes that the right decision can be made in an ethically questionable situation. Relativism, in contrast, refers to the rejection of universal rules in making ethical judgments and focuses on the social consequences of behavior. In our study, general ethical judgments are believed ethicalness of various questionable practices, which consist of four dimensions: actively benefiting from an illegal activity (denoted by AI in this study), passively benefiting at the expense of others (PB), actively benefiting from questionable actions (AQ), and no harm/no foul (Muncy and Vitell 1992). The four judgments are ethical beliefs regarding various ethically questionable practices. The present study differs from Henle et al. (2005) in two ways. First, whereas Henle et al. (2005) examined the relationship between ethical ideology and workplace deviance, this study links general ethical judgments to workplace deviance.

This is consistent with Vitell’s (2003) suggestion that future studies could examine the link between general ethical judgments and other intentions and/or behaviors. Second, Henle et al. (2005) examined the two dimensions of ethical ideology, idealism and relativism, which interact in their effects on workplace deviance. This study, however, examines if the perceptions of the work situations, namely POS and IJ, will moderate the relationships between general ethical judgments and workplace deviance.

Theories and hypotheses

General ethical judgments and workplace deviance

Much research on workplace deviance has focused on identifying individual difference variables that predict deviant behavior in the workplace. These studies suggest that personality traits such as negative affectivity (NA), agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, personality dissimilarity, and self-esteem are related to employees’ deviant work behaviors (Aquino, Lewis and Bradfield 1999; Skarlicki, Folger and Tesluk 1999; Colbert et al. 2004; Liao et al. 2004; Burton, Mitchell and Lee 2005). However, there is a paucity of research investigating the relationship between workplace deviance and individual differences in moral thought or belief. Some theories have been proposed regarding individual differences in ethical judgments. For example, Kohlberg’s (1983) stages of moral development emphasize those used to justify moral decisions (e.g. consequences, moral standards of others, and self-generated moral standards). Vitell and Muncy (1992) reveal that individuals use three major rules to make their ethical judgments: the locus of the fault, the legality of the behavior, and the degree of harm caused. Forsyth (1992) has recognized that personal ethical ideology has a considerable impact on socially disapproved behavior. Henle et al. (2005) showed that idealism was negatively correlated with interpersonal deviance; employees lower in idealism were more likely to act deviantly toward others in their work environment.

Ethical judgments are beliefs about the moral rightness or wrongness of an action (Hunt and Vitell 1986). Muncy and Vitell (1992) defined general ethical judgments as ‘the moral principles and standards that guide behavior of individuals or groups as they obtain, use, and dispose of goods and services.’ To measure this construct, Muncy and Vitell (1992) developed a scale in which questions with ethical implications were divided into four classes. The first class, ‘actively benefiting from illegal activities,’ consists of questions regarding actions that are initiated by individuals and that are almost universally perceived as illegal (e.g. drinking a can of soda in a supermarket without paying for it). The second class, ‘passively benefiting at the expense of others,’ includes questions regarding individuals taking advantages of mistakes made by the other party (e.g. not saying anything when the waitress miscalculates the bill in your favor). The third class, ‘actively benefiting from questionable actions or behaviors,’ includes questions regarding situations in which individuals are actively involved in some deception, but their actions may not necessarily be considered illegal (e.g. using a coupon for merchandise they did not buy). The last class, ‘no harm,’ includes questions regarding situations in which individuals perceive their actions as doing little or no harm (e.g. using computer software or games they did not buy).

Previous studies have examined the extent to which general ethical judgments are related to other variables such as attitudinal characteristics and materialism (Vitell and Muncy 1992; Chan et al. 1998; Muncy and Eastman 1998). However, little attention has been given to the relationships between general ethical judgments and ethical behavior. To date, only one study has investigated the relationships between general ethical judgments

and unethical behavior. Suter, Kopp and Hardesty (2004) examined how certain ethical beliefs (actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, and no harm) are related to judgments regarding copying behavior in the workplace. Vitell (2003) suggested linking general ethical judgments to intentions and/or behavior in subsequent research.

Randall (1989) surveyed empirical studies that had examined the Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) model and found that the link between judgments and intentions was substantiated. Moral evaluation is a key component in the model of ethical decision making (e.g. Hunt and Vitell 1986; Akaah and Riordan 1989). Individuals confronted with an ethical dilemma evaluate it on the basis of relevant ethical cognitions about themselves. An individual’s low ethical standards may be the key variable that breeds unethical behavior (Vitell, Lumpkin and Rawwas 1991). Accordingly, employees with more unethical beliefs and thoughts may have lower ethical standards in judging the acceptability of questionable actions, and thus are more likely to engage in deviant behaviors in the workplace than those with less unethical beliefs and thoughts.

Some studies have found that individuals appear to hold differential concerns toward ethically questionable behaviors, generally perceiving the ‘actively benefiting from an illegal activity’ type of behavior most unethical and the ‘no harm/no foul’ type of behavior least unethical (e.g. Muncy and Vitell 1992; Rallapalli, Vitell, Wiebe and Barnes 1994; Rawwas, Vitell and Al-Khatib 1994). The actions of no harm/no foul, which appear acceptable to many, may be so rated, because no direct harm is done (although indirect harm may occur). It seems that individuals with the ethical judgments of ‘no harm/no foul’ are more unlikely to engage in deviant behaviors targeting either organizational members or the organization itself. Thus, the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions are more likely to lead to deviant workplace behaviors, while the judgments of no harm are not. Thus, the following is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: The judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions have positive influences on interpersonal and organizational deviance.

The moderating role of perceived organizational support

Another research question to be addressed in this study is that perceptions of the work situation may moderate the relationships between general ethical judgments and workplace deviance. That is, general ethical judgments and perceptions of the work situation would interact in their relationships with workplace deviance. Personality characteristics or individual differences have been found to have a greater impact on certain organizational processes when low situational constraints are present than high situational constraints (Weiss and Adler 1984). Work situation variables may affect how an individual reacts to his or her moral judgment (Trevin˜o 1986). Accordingly, the relationships between general ethical judgments and employee deviance discussed earlier may be contingent on theoretically relevant perceptions of the work situation in such a way that the relationships exist only when deviant behavior is provoked by the unfavorable work situation. Specifically, employees who have low ethical standards for judging ethically questionable actions are likely to behave deviantly, but only for those having low levels of POS.

POS reflects the quality of the employee – organization relationship by measuring the extent to which employees believe that their organizations value their contributions and care about their welfare (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa 1986). In an organizational setting, when employees perceive that they are supported by the organization (i.e. a favorable exchange), they will respond by directing positive behaviors toward the organization. In support of the social exchange perspective, POS has been shown to correlate with positive affect and organizational spontaneity (Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch and Rhoades 2001), as well as the desire to remain in the organization (Nye and Witt 1993). Meyer and Allen (1991) asserted that work experiences, especially those that increase employees’ level of comfort (e.g. perceived equity in reward distribution, POS, and supervisor consideration) are most consistently related to affective commitment. It is expected that employees, whose work experiences are consistent with their expectations and satisfy their basic needs, will develop a stronger affective attachment to the organization than those whose work experiences are less satisfying (Meyer, Allen and Smith 1993), because employees could satisfy this indebtedness through greater affective commitment to the organization and greater efforts to help the organization.

Specifically, the current investigation examines the possibility that POS moderates the influences of general ethical judgments on interpersonal and organizational deviance. When individuals with less moral thoughts perceive greater supports from the organization, they will become more motivated to refrain from behaviors that harm the organization. One means for employees to reciprocate for organizational support is by abiding by organizational norms. For example, employees who perceive high levels of organizational support should be less likely to say something hurtful or act rudely to a coworker (Colbert et al. 2004). Thus, when POS is high, the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities, the ethical judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others, and the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions have weak relationships with workplace deviance. However, when POS is low, workplace deviance becomes acceptable responses to employees’ less moral thoughts. Colbert et al. (2004) argued that employees who have negative perceptions of their work situation are likely to reciprocate by withholding effort or by engaging in more interpersonal deviance. That is, low level of morality in judging ethically questionable behaviors is associated with high levels of workplace deviance when POS is low. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: POS moderates the influences of actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions on interpersonal and organizational deviance such that the higher the POS, the weaker the influences.

The moderating role of interactional justice

A number of authors (e.g. Sheppard, Lewicki and Minton 1992; Folger 1993) have argued that if employees perceive organizational decisions and managerial actions to be unfair or unjust, they are likely to experience feelings of anger, outrage, and resentment. Unjust treatment can elicit retribution, and those who feel unfairly treated might retaliate and punish those who are seen as responsible for the problem (Skarlicki et al. 1999). In studies investigating deviance as adaptation to the social context at work, Robinson and Greenberg (1998) note that unfair interpersonal treatment is a prominent social influence

on deviance. The key concept here may be IJ. IJ refers to the fairness of the treatment an employee receives in the enactment of formal procedures or in the explanation of those procedures (Bies and Moag 1986). When decision makers treat people with respect (e.g. treating people with dignity and courtesy) and proprietary (e.g. refraining from improper comments) and thoroughly explain the rationale for their decisions, IJ is fostered. A cross-cultural study by Mikula, Petri and Tanzer (1989) found that perceived violations of IJ were the most important category of unjust events reported by respondents, indicating that these perceptions may exert the strongest influence on employee job responses. Day-to-day interpersonal encounters are so frequent in organizations that interpersonal justice often becomes more relevant and psychologically meaningful to employees, compared with other types of justice information (Bies 2005; Fassina, Jones and Uggerslev 2008). Aquino et al. (1999) found that perceptions of IJ were stronger predictors of deviant behaviors directed against both the organization and other individuals than either distributive or procedural justice. The findings also reveal that interpersonal concerns may be more salient to individuals when they form judgments of fairness than either outcomes or the structural characteristics of procedure. As a result, of the three categories of justice perceptions, we decide to focus on IJ because of its relatively stronger relationship with deviant behaviors.

Research on the relationships between justice and deviance has also suggested that the different dimensions of justice are tied to different sources and as individuals seek to determine the source of unfairness to direct their deviance reactions, the source of injustice tends to be aligned with the target of deviance. In essence, distributive and procedural justice are generally attributed to the organization’s actions, so research has generally demonstrated that these dimensions are associated with organization-directed deviance (e.g. Aquino et al. 1999; Bennett and Robinson 2000; Ambrose, Seabright and Schminke 2002; Berry, Ones and Sackett 2007). Similarly, interactional (i.e. interpersonal and informational) justice emanates from specific individuals (e.g. supervisors), therefore it has been generally associated with interpersonal deviance (e.g. Aquino et al. 1999; Bennett and Robinson 2000; Ambrose et al. 2002). There are some reasons to explain this. First, violations of IJ may trigger retaliatory action, partially due to individual sensitivity to fair treatment. Involvement in a personal relationship that is characterized by a high degree of trust and respect (i.e. high IJ) communicates a sense of communality and being highly regarded (Van den Bos, Lind and Wilke 2001; Brockner 2002). A lack of trust and respect while interacting with others (i.e. violations of IJ) can lead to feelings of exclusion and a loss of social identity (Lind, Kray and Thompson 2001). Thus, IJ perceptions primarily affect attitudes and behaviors toward the person carrying out the treatment, unlike procedural justice perceptions, which are thought to impact reactions to the employing organization. Second, recent theories suggest that violations of distributive justice (i.e. unfair outcome) are not enough to trigger the intention to providing emotional or physical discomfort or harm for others in the organization such as bosses or coworkers (Greenberg and Alge 1998). It is likely that a person becomes aware of injustice when they receive an unfair outcome, but individuals need a stronger motive to respond. One such motive occurs when a person believes that violations of IJ have occurred (Greenberg 2002). Third, Bies and Tripp (2001) stated that abuse by one’s supervisor is one example of the type of ‘sparking event’ that can lead to revenge. This ‘sparking event’ may lead to escalating instances of aggression in the workplace (e.g. spreading rumors, or verbal abuse). Thus, the interpersonal nature of interactional injustice (e.g. supervisor interpersonal injustice) may result in interpersonal deviance, rather than organizational deviance, which is more impersonal in nature.

Because IJ is highly relevant to interpersonal deviance, we focus on examining the moderating effect of IJ on the relationships between general ethical judgments and interpersonal deviance. Recent evidence suggests that individual responses to unfavorable actions are less severe when they perceive the procedures adopted as just (Brockner, Dewitt, Grover and Reed 1990). Furthermore, the situational strength theory may explain this moderating role. It has long been argued that relationship between individual differences and behavior is moderated by the strength (or demands) of the situation (Mischel 1977; Weiss and Adler 1984). This theory describes strong situations as those in which appropriate behaviors are clear and expectations of the environment are met. The possibility of exerting the influence of an individual’s differences is low in such situations preventing interpersonal variables from predicting outcomes. Contrarily, in a weak situation when environments are unpredictable and proper behaviors are unclear, the individual difference – behavior association is likely to emerge. The same can be applied to explain how the interplay between individual differences in ethical judgments and IJ affects workplace deviance. We proposed that interaction justice should create a strong circumstance in which the employees are treated with dignity, proper manners, and respect and in which the supervisor explains the procedures thoroughly and communicates details. This situation will lead to clear expectations of behaviors and a predictable environment. Hence, we extended the situational strength theory to include justice as a strong situation in which individual differences in ethical judgments is allowed less variability to predict workplace deviance. In other words, the relationships between general ethical judgments and interpersonal deviance will be weaker for the higher IJ in the workplace situation. Similarly, the relationships will be stronger for the lower IJ. Thus, the following is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: IJ moderates the influences of actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions on interpersonal deviance such that the higher the IJ, the weaker the influences.

Methods Participants

Participants were 460 full-time employees in Taiwan from different organizations in different industries. This diversity was valuable in that it enabled us to more confidently generalize our results to the larger employee population. The sample was appropriate because researchers in the areas of workplace deviance have emphasized the need for samples that span several organizations and occupations (e.g. Bennett and Robinson 2000). In addition, sample relevance (Sackett and Larson 1990) has been taken into account. The sample possessed the essential personal and setting characteristics that defined membership in the intended target population. During the survey for this study, each questionnaire included a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, and respondents were assured that all information would be kept confidential to increase the response rate and acquire more accurate information. The response rate was 92%.

Of the respondents, the average age was 31.63 years (SD ¼ 8.07) and the average organizational tenure was 5.85 years (SD ¼ 6.66); 52.4% were men, 47.6% were women, 8.1% completed high school or lower educations, 33.9% completed 2-year college/voca-tional school educations, 41.5% had bachelor degrees, and 16.5% possessed graduate degrees. The distribution of occupation was as follows: production, 34.3%; service, 41.1%; public sectors, 12.8%; others, 11.8%.

Measures

All of the measures used for the constructs in this study were taken from the existing literature. They have been well translated (by satisfactory back-translation) and pretested (by successful interviews with supervisors and job incumbents of several occupations). General ethical judgments

Actively benefiting from illegal activities (AI) (e.g. drinking a can of soda in a supermarket without paying for it), passively benefiting at the expense of others (PB) (e.g. getting too much change and not saying anything), and actively benefiting from questionable actions (AQ) (e.g. using an expired coupon for merchandise) were measured using the scale developed by Muncy and Vitell (1992). The order of 12 items for the three dimensions was randomized in the questionnaire to avoid order effects. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they perceived a given behavior as being wrong or not wrong, on a six-point Likert scale (1 ¼ strongly believe that it is wrong; 6 ¼ strongly believe that it is not wrong). Coefficient alphas for actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions were 0.67, 0.71, and 0.66, respectively.

Perceived organizational support

POS was assessed by using the short version of the survey of perceived organizational support (SPOS) (with eight items) developed by Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch (1997). Respondents indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statements such as ‘my organization really cares about my well-being’ on a six-point Likert scale (1 ¼ strongly disagree; 6 ¼ strongly agree). The coefficient alpha for POS was 0.88.

Interactional justice

Seven items adopted from Niehoff and Moorman (1993) were used to measure this construct. Employees were asked to indicate the degree to which they felt their needs were considered in and adequate explanations were made for job decisions on a six-point Likert scale (1 ¼ strongly disagree; 6 ¼ strongly agree). A sample item was ‘When decisions are made about my job, the general manager treats me with kindness and consideration.’ The coefficient alpha for IJ was 0.94.

Workplace deviance

The workplace deviance was measured using the scale developed by Bennett and Robinson (2000). The first part of the scale consists of seven items that assess deviant behaviors directly harmful to other individuals within the organization (interpersonal deviance). A few examples are: ‘Said something hurtful to someone at work’; ‘Played a mean prank on someone at work’; and ‘Acted rudely toward someone at work.’ The second part of the scale consists of nine items that assess deviant behaviors directly harmful to the organization (organizational deviance). Examples of items are: ‘Taken property from work without permission’; ‘Intentionally worked slower than you could have worked’; and ‘Come in late to work without permission.’ All respondents rated how often they engage in these behaviors during the past 1 year on the 16 items on a six-point Likert scale with anchors ranging from 1 ¼ never to 6 ¼ daily. Coefficient alphas for interpersonal deviance and organizational deviance were 0.84 and 0.82, respectively.

Control variables

Past research showed that NA would positively influence employees’ deviant behaviors (e.g. Aquino et al. 1999; Skarlicki et al. 1999). Watson and Clark (1984) defined NA as a higher-order personality variable describing the extent to which an individual experiences (either in terms of frequency or intensity) levels of distressing emotions such as anger, hostility, fear, and anxiety. Compared to a person who scores low on a measure of NA, an individual who scores high on such a measure can be described as experiencing greater distress, discomfort, and dissatisfaction over time and in different situations (Watson and Clark 1984). Indirect evidence suggests that NA is related to certain forms of negative behaviors. For example, Eysenck and Gudjonsson (1989) reported that NA predicted delinquency, defined as the tendency to violate moral codes and engage in disruptive behavior. Heaven (1996) reported that NA was related to self-reports of interpersonal vandalism, violence, and theft. Thus, we included NA as a control variable. Eight items adapted from the PANAS scale (Watson, Clark and Tellegen 1988) were used to measure negative effect as a trait variable. Respondents were asked to indicate how often they had experienced each mood state within the last 1 year using a six-point Likert scale (1 ¼ not at all; 6 ¼ a lot). The coefficient alpha was 0.90.

In addition, we included three demographic variables (gender, age, and tenure) as control variables. Gender was controlled because males tend to engage in more aggressive behavior at work (Baron, Neuman and Geddes 1999), absenteeism (e.g. Johns 1997), and theft (e.g. Hollinger and Clark 1983). Age was also controlled because empirical evidence indicates that older employees tend to be more honest than younger employees (Lewicki, Poland, Minton and Sheppard 1997). Hollinger, Slora and Terris (1992) suggested that employees with less tenure were more likely to commit organizational deviance. Thus, we controlled for tenure.

Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of all variables included in this study. In our study, we found that organizational deviance (mean ¼ 2.47) was rated higher than interpersonal deviance (mean ¼ 2.22). In addition, there were positive correlations between workplace deviance and judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions. There were negative correlations between workplace deviance and IJ, and POS.

Validity assessment

Prior to testing for our hypotheses, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for AI, PB, AQ, POS, IJ, NA, interpersonal deviance, and organizational deviance. Although the fit was not quite satisfactory (adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) ¼ 0.80; comparative fit index (CFI) ¼ 0.89; normed fit index (NFI) ¼ 0.82; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ¼ 0.05), the construct validity of the measurements has been supported by noting that, based on Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) recommendation, the relationships between each indicator variable and its corresponding construct were significant (t-values all . 2.58, p , 0.01), verifying the convergent validity, and all pairs of constructs were significantly distinct (the chi-square difference statistics were all greater than the critical value ofx2(1, 0.05/28) ¼ 9.76 by using the Bonferroni method and under the experiment-wise error rate of 0.05), demonstrating the discriminant validity.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables. Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 0 1 1 1 2 1. Gender a –– 2. Age 31.63 8.06 2 0.30 ** 3. Education(year) 15.31 1.81 2 0.07 2 0.16 ** 4. Tenure (year) 5.85 6.66 2 0.19 ** 0.76 2 0.33 ** 5. NA 3.07 0.83 2 0.02 2 0.07 2 0.01 0.01 (0.90) 6. AI 1.67 0.62 2 0.03 2 0.12 ** 2 0.02 2 0.05 0.03 (0.67) 7. PB 2.94 0.93 2 0.09 2 0.11 * 0.07 2 0.08 2 0.03 0.37 ** (0.71) 8. AQ 2.54 0.94 2 0.05 2 0.00 0.07 2 0.02 0.04 0.40 ** 0.43 ** (0.66) 9. POS 3.83 0.98 2 0.06 0.07 2 .01 0.05 2 0.17 ** 0.00 2 0.03 2 0.02 (0.94) 10. IJ 3.87 0.97 2 0.05 0.02 0.01 0.05 2 0.10 * 2 0.02 2 0.02 2 0.05 0.64 ** (0.88) 11. ID 2.22 0.90 0.04 2 0.27 ** 0.01 2 0.18 ** 0.12 ** 0.18 ** 0.11 * 0.12 * 2 0.16 ** 2 0.12 ** (0.84) 12. OD 2.47 0.88 2 0.05 2 0.23 ** 0.16 ** 2 0.22 ** 0.14 ** 0.15 ** 0.20 ** 0.17 ** 2 0.17 ** 2 0.10 * 0.38 ** (0.82) Notes : N ¼ 460; NA, negat ive affectivity; A I, actively benefi ting from il legal activities; PB, passi vely benefi ting at the expense o f oth ers; AQ, actively benefi ting from questio nable actions; POS, per ceived or ganizational supp ort; IJ, inter actional justice; ID, inte rpersonal devia nce; OD , organiz ational devi ance; * p , 0.05 ;** p , 0.01 . aGender wa s co ded by 0 ¼ male and 1 ¼ femal e. Coeffi cient alpha s are on the diag onal.

Results of hypothesis testing

As seen in Table 2, a series of hierarchical regression analyses were performed to test whether the three dimensions of general ethical judgments positively related to interpersonal and organizational deviance, and whether POS and IJ moderated the relationships between general ethical judgments and workplace deviant behaviors (WDBs).

First, four control variables, including gender, age, tenure, and NA, were entered into the regression, as in Models 11 and 21, using interpersonal deviance and organizational deviance, respectively as the dependent variables. Overall, the models accounted for 8% of the variance in interpersonal deviance ( p , 0.01) and 9% of the variance in organizational deviance ( p , 0.01). Employees’ age and NA were significantly related to both interpersonal and organizational deviance. The younger employees tended to be more unethical than older employees in the workplace. Individuals with high NA were more likely to engage in workplace deviance.

Second, the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, and actively benefiting from questionable actions were added to the regression, as in Models 12 and 22 for interpersonal and organizational deviance, respectively. The three variables explained significant additional amounts of variability in interpersonal and organizational deviance beyond the control variables (DR2¼ 0.02 and 0.04, p , 0.01). The standardized regression coefficients associated with the three ethical judgments were all positively significant for interpersonal deviance, and for organizational deviance except actively benefiting from questionable actions. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was mostly supported.

Third, the two moderators, POS and IJ, were further added to the regression for interpersonal deviance, as in Model 13. The extra variability in interpersonal deviance explained by POS and IJ is significant (DR2¼ 0.02, p , 0.01). On the other hand, only POS was further added to the regression for organizational deviance, as in Model 23. The extra variability in organizational deviance explained by POS is also significant (DR2¼ 0.02, p , 0.01).

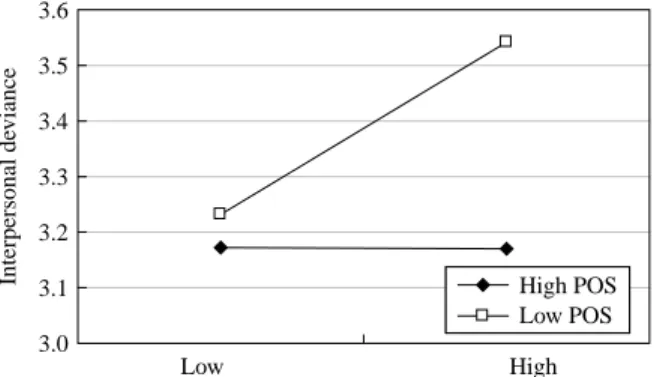

Finally, the six interaction terms, AI £ POS, PB £ POS, AQ £ POS, AI £ IJ, PB £ IJ, and AQ £ IJ, were further included to the regression for interpersonal deviance, as in Model 14, to examine the moderating effects of POS and IJ. However, only the three interaction terms, AI £ POS, PB £ POS, and AQ £ POS, were included for organizational deviance, as in Model 24. The resulting DR2 was significant for the former (0.03, p , 0.01), but not for the latter (0.006, p . 0.5). To reduce the effects of multicollinearity, all variables were centered before performing analysis. It appears that only AQ £ POS and PB £ IJ were significant for interpersonal deviance (b¼ 2 0.08, p , 0.05;b¼ 2 0.10, p , 0.01, respectively). Figures 1 and 2, produced based on the regression estimates (e.g. Cohen and Cohen 1983), support the expected shape of the hypothesized interactions. Figure 1 illustrate that when POS was relatively low, the judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions were positively related to interpersonal deviance. In contrast, when POS was relatively high, the magnitude of the positive relationship was substantially reduced. In addition, Figure 2 indicate that when IJ was relatively low, the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others had positive influence on interpersonal deviance. In contrast, when IJ was relatively high, the influence became much weaker. Thus, Hypotheses 2 and 3 were partially supported.

Table 2. Results of hierarchical regression analysis predicting workplace deviance. Interpersonal deviance Organizational deviance Variable Model 11 Model 12 Model 13 Model 14 Model 21 Model 22 Model 23 Model 24 Control variables Gender 2 0.07 2 0.04 2 0.05 2 0.03 2 0.21 * 2 0.16 † 2 0.16 * 2 0.15 † Age 2 0.04 ** 2 0.03 ** 2 0.03 ** 2 0.03 ** 2 0.02 * 2 0.01 † 2 0.01 † 2 0.01 Tenure 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 2 0.02 2 0.02 † 2 0.02 † 2 0.02* NA 0.07 † 0.07 † 0.07 † 0.09 * 0.10 ** 0.11 ** 0.11 ** 0.11 ** General ethical judgments AI 0.09 * 0.09 * 0.08 * 0.09 * 0.09 * 0.09 * PB 0.07 † 0.07 † 0.08 * 0.16 ** 0.16 ** 0.16 ** AQ 0.08 * 0.08 * 0.08 * 0.05 0.05 0.04 Moderators POS 2 0.10 * 2 0.11 ** 2 0.12 ** 2 0.12 ** IJ 2 0.08 * 2 0.09 * Interaction terms AI £ POS 2 0.04 2 0.05 PB £ POS 2 0.00 0.02 AQ £ POS 2 0.08 * 2 0.04 AI £ IJ 0.06 PB £ IJ 2 0.10 ** AQ £ IJ 0.05 Model F 9.83 7.33 6.95 5.23 10.79 9.65 9.73 7.37 R 2 0.08 ** 0.10 ** 0.12 ** 0.15 ** 0.09 ** 0.13 ** 0.147 ** 0.153 ** D R 2 0.02 ** 0.02 ** 0.03 * 0.04 ** 0.017 ** 0.006 Notes : The entrie s in the table are standar dized betas. NA, negat ive affectivity; AI, actively benefiti ng from illegal activities ; P B , passively ben efi ting at the expense o f others; AQ , actively benefi ting from questio nable actions; POS, per ceived organiz ational supp ort; IJ, inter actional justic e; † p , 0.10; * p , 0.05 ;** p , 0.01 .

Discussions

Over the years, there has been limited research on counterproductive behaviors at the workplace in Asian countries (Hamilton and Sanders 1995; Xie and Johns 2000). Smithikrai (2008) has suggested that WDB is an important aspect of job performance in the Eastern countries. One purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between individual differences in ethical judgments and workplace deviance. As expected, we found that employees having the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal actions and/or the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others were more likely to engage in interpersonal and organizational deviance. Employees having the judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions were more likely to engage in interpersonal deviance only. According to Vitell and Muncy (1992), while the behaviors regarding actively benefiting from questionable actions seem to be deceptive, these actions are probably not seen as illegal activities. However, some organizational deviant behaviors, for instance, ‘taken property from work without permission,’ may be seen as deceptive and illegal. The issue of ‘perceived illegality’ is, perhaps, what makes some types of organizational deviance less acceptable. Hence, employees having the judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions may not be likely to engage in some deviant behaviors directed at the organization. These results are important due to the differential effects of certain ethical judgments on interpersonal and organizational deviance. This can

3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6

Actively benefiting from questionable actions

Low High

Interpersonal de

viance

Low POS High POS

Figure 1. The moderating effects of perceived organizational support (POS).

3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6

Passively benefiting at the expenses of others

Low High

Interpersonal de

viance

Low IJ High IJ

Figure 2. The moderating effects of interactional justice (IJ).

further justify the distinction between interpersonal and organizational deviance and further our understanding of the workplace deviance construct (Mount, Ilies and Johnson 2006). Overall, individual differences in moral thought or belief truly influence employees’ deviant workplace behaviors. Employees with more unethical judgments are more likely to engage in unethical actions in the workplace. The present finding regarding the relationships between individual differences in ethical judgments and WDB in the Taiwanese context are quite similar to those found in the Western context (e.g. Kohlberg 1983; Forsyth 1992; Vitell and Muncy 1992; Henle et al. 2005). This may be because WDB is commonly undesirable and rejected by any given organizations. It is very likely that most contents of WDB (e.g. ‘Taken property from work without permission’; ‘Unauthorized absence’) would be viewed as undesirable in most societies. It is argued here that, across countries, when it comes to performance, certain work-related behaviors are prohibited to deter negative effects on productivity regardless of the country of the employees. Thus, even though employees in Taiwan and the USA are in culturally different societies, they both share the same perception and have a similar work standard that WDB is undesirable and strongly prohibited.

The other purpose of this study was to examine how perceptions of work situation moderated the relationships between employees’ ethical judgments and workplace deviance. We found that when employees perceived high POS, the influence of judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions on interpersonal deviance was significantly reduced. Employees who perceive high levels of organizational support may reciprocate by abiding by organizational norms associated with interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, when employees perceived high IJ, the influence of judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others on interpersonal deviance was also significantly reduced. Employees who perceive high IJ are less likely to engage in deviant acts toward others even if provoked by the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others.

Partial hypotheses concerning moderating effects were not supported. First, for interpersonal deviance, POS was unable to moderate the relationships of the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities and the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others with interpersonal deviance; IJ was unable to moderate the relationships between the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities and actively benefiting from questionable actions with interpersonal deviance. As mentioned previously, past studies have found that individuals perceive that the ‘actively benefiting from illegal activities’ type of behavior is most unethical (e.g. Muncy and Vitell 1992; Rallapalli et al. 1994; Rawwas et al. 1994). It appears that if individuals have the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities, both POS and IJ could not exert great effects on restraining their intentions to engage in interpersonal workplace deviance, because of the intrinsically possessing illegal thoughts and beliefs. The results also showed that employees having the judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions (e.g. believing ‘stretching the gossip to someone at work’ is ethically not wrong) paid considerable attention to whether their work organization valued their contributions and cared about their well-being. Interpersonal fair treatment may not produce greater effect on them. However, IJ can restrain employees with the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others (e.g. believing ‘remaining silent when hearing incorrect criticism of their supervisors’ or ‘tolerant of others deviance and less willing to report these behaviors to management’ is ethically not wrong) from engaging in interpersonal deviance. When employees feel the quality of interpersonal treatment received during the execution of a procedure is maintained, and adequate explanations are given for job decisions, even if

they have the beliefs of passively benefiting, they are less likely to engage in interpersonal deviance. In other words, employees having tendency to passively benefiting at the expense of others attach more importance to IJ than organization support.

Second, for organizational deviance, one noteworthy empirical finding was that POS was unable to moderate the relationships between general ethical judgments and organizational deviance. This may be explained for some reasons. First, existing theory and research suggest that employees’ thoughts about work (cognitions) and their feelings about work (affect) are likely to influence workplace deviance behavior (Organ and Near 1985; Lee and Allen 2002). Indeed, the suggestion that two motives, instrumental and expressive, underlie workplace deviance sets the stage for both cognition- and affect-oriented explanations of this behavior (Sheppard et al. 1992; Greenberg and Scott 1996; Robinson and Bennett 1997). Instrumental motivation reflects ‘attempts to reconcile the disparity by repairing the situation, restoring equity, or improving the current situation’ (Robinson and Bennett 1997, p. 18). Lee and Allen (2002) demonstrated that employees’ job cognitions, such as reward equity and recognition, were associated with organizational deviance but not with interpersonal deviance. In contrast, expressive motivation for workplace deviance reflects ‘a need to vent, release, or express one’s feelings of outrage, anger, or frustration’ (Robinson and Bennett 1997, p. 18). Behaviors induced by an expressive motive may be directed at coworkers, clients, or the organization and may be enacted both at work and outside work. Thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that workplace deviance behaviors that harm the organization are more cognition-driven than affect-driven. In contrast, behavior that is harmful to individuals might have a stronger affective, than cognitive, underpinning (Lee and Allen 2002). As mentioned earlier, base on social exchange perspective, POS has been shown to correlate with positive affect and organizational spontaneity and desire to remain (affective attachment) in the organization. Employees who perceive low levels of organizational support are likely to experience frustration because they do not feel as though they have the support to achieve their goals (Colbert et al. 2004), which, as Spector (1997) noted, may lead to such deviant behaviors as hostility or aggression. Meyer and Allen (1991) asserted that POS, freedom from conflict, and supervisor consideration showed the most consistent relationship with affective commitment. It seems that POS is more strongly related to job affect than to job cognition. Consequently, POS is more related to interpersonal deviance than organizational deviance. Future study should attempt to examine the moderating role of employees’ job cognition on the influence of general ethical judgments on organizational deviance or the antecedents of organizational deviance such as organizational arrangements (e.g. disciplinary procedures and performance monitoring). Second, cultural values at the national level could be invoked as an explanatory variable. Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002, p. 711) noted that the social exchange theory explanations for a relationship between POS and employee outcomes are founded in norms of reciprocity and that ‘the strength of this association should be influenced by employees’ acceptance of the reciprocity norm as a basis for employee-employer relationships.’ At the societal level, power distance refers to ‘the extent to which a society accepts the fact that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally’ (Hofstede 1980a, p. 45). Subordinates high in power distance – that is, those who score high on a power distance measure – are, because of their strong deference to authority figures, likely to be less reliant on the reciprocity norm with respect to their performance contributions than their counterparts with low power distance scores (Farh, Hackett and Liang 2007). Partners holding the high power distance value maintain greater social distance, and role expectations bind employees to show deference, respect, loyalty, and dutifulness to

authority figures. Power distance beliefs shape social connections not only to authorities, but also to organizations (Tyler, Lind and Huo 2000). This notion that social exchange theory explanations for employee attitudes and behaviors apply less to individuals high in power distance has received considerable support (e.g. Lee, Pillutla and Law 2000; Lam, Schaubroeck and Aryee 2002). The Taiwanese culture is rated as relatively high on the dimensions of power distance (Hofstede 1980b). It is reasonable that the relationship between POS and organizational deviance is weaker for those higher in power distance. Future study should attempt to examine the moderating role of national-level or individual-level cultural values on the influence of general ethical judgments on organizational deviance. Another possible explanation is that organizational deviance (e.g. abusing break times) is less observable and more difficult to detect than interpersonal deviance (e.g. arguing) (Mount et al. 2006). Employees are more likely to engage in organizational deviance with opportunistic manner.

Implications

Understanding the factors that are related to workplace deviance also has some practical implications. First, we found that an employee’s ethical judgments are positively related to deviant behavior. The results are consistent with previous research (Henle et al. 2005), which showed that idealism of ethical ideology plays an important role in the occurrence of workplace deviance. The results further support the claim that effective method for preventing unethical and deviant behavior requires attention to both individual differences and the importance of creating an ethical work environment (Knouse and Giacalone 1997). From the bad apples perspective, individual characteristics are assumed to be the primary force influencing unethical behavior in organizations (Brass, Butterfield and Skaggs 1998), such as cognitive moral development (Ford and Richardson 1994), locus of control (Trevin˜o and Youngblood 1990), and Machiavellianism (Hegarty and Sims 1978). The bad apples perspective leads to the prescription that organizations should attempt to attract individuals who match an evolving profile of desirable characteristics. Selecting employees on the basis of individual differences in ethical judgments is likely to reduce the frequency and severity of deviant behavior that occurs in the organization. Furthermore, from the bad barrels perspective, the various attributes of organizations and society that influence unethical behavior in organizations should receive much attention. For example, Peterson (2002) revealed that deviant workplace behavior could be partially predicted from the ethical climate of an organization. If individuals with less moral thoughts lie in less ethical work environment, they have more desire to engage in workplace deviance (Knouse and Giacalone 1997).

Second, we found that positive situational perceptions at work lessen the impact of employees’ ethical judgments on workplace deviance. Thus, one way that organizations may reduce deviance in the workplace is to allocate more resources for those activities that are associated with employees’ positive perceptions of organizational support and their positive perceptions of interpersonal treatment. These findings further underscore the importance for the companies to enhance perceived support and fairness of all employees to reduce the occurrence of workplace deviance.

Third, organizational training programs should include a component that conveys to managers the pervasiveness and expense associated with workplace deviance, and explains the nature of deviant behaviors. This study provides support for the two-factor model for workplace deviance. There are two distinct types of deviance, and individuals who engage in one type of workplace deviance may not engage in the other. This provides

implications for rating employees’ performance for managers. It is suggested that deviant behavior is not unidimensional and supervisors should avoid a large amount of halo in rating the two types of workplace deviance.

Limitations

Four limitations of this study should be noted. First, in our study, workplace deviance was measured via self-report. Respondents may ‘fake good’ under the influence of social desirability. Although the accuracy of the deviance measures might be enhanced by asking supervisors or peers to report on the behavior of respondents, or by using organizational records, these types of assessment have their own limitations. It is unclear whether either observers or organizational records could provide more accurate data than respondents themselves, given that many instances of workplace deviance go unreported and unseen, thus constraining the validity of other reports (Bennett and Robinson 2000). In addition, meta-analyses have shown that self-reported criteria are even of higher validity than other reports of deviance (McDaniel and Jones 1988; Ones, Viswesvaran and Schmidt 1993). Further research should try to employ multiple sources of information on deviance.

Second, all of our measurements were collected from a single source. It is possible that relations among the constructs may have been inflated by common method variance. However, while it is difficult to obtain data from different sources in the present study, the technique for procedural remedies can be used to partially mitigate this concern. The potential remedy is to proximally or methodologically separate the measures by having respondents complete the measurements of the predictor and criterion variables under different conditions (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff 2003). In this study, we avoided item priming effects and used different scale anchors for the measures to reduce common method variance. In addition, we adopted Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986) to examine the problem of common method variance. If there were sizable inflation caused by same-source bias, then a single-factor solution would explain a substantial amount of the total variance of the variables. Our analysis found that a single-factor solution explained only 19% of the total variance. In addition, we used CFA (Korsgaard and Roberson 1995) to compare the fit resulting from the one-factor model with that from the eight-factor model (including AI, PB, AQ, POS, IJ, NA, interpersonal deviance, and organizational deviance). Since the eight-factor model had a better fit (x2/df ¼ 2.35, AGFI ¼ 0.80, CFI ¼ 0.89, NFI ¼ 0.82, and RMSEA ¼ 0.05) than the one-factor model (x2/df ¼ 8.06, AGFI ¼ 0.40, CFI ¼ 0.38, NFI ¼ 0.35, and RMSEA ¼ 0.12), common method variance was not a serious problem in this study.

Third, the effects we reported in this study are modest, typically accounting for approximately 15% to 16% of criterion variance. On the basis of both statistical and substantive considerations, we suggest that this is not the case. First, in our study, workplace deviance was measured via self-report. As previous studies (e.g. Fox and Spector 1999; Bennett and Robinson 2000), self-reports have been found to be an accurate method of assessing behaviors like workplace deviance. It seems likely that if participants were to respond inaccurately, they would underreport deviance in an effort to engage in impression management. Thus, we might have underestimated the actual level of workplace deviance. Indeed, we found that such behaviors were infrequently reported (interpersonal deviance, M ¼ 2.22, SD ¼ 0.90; organizational deviance, M ¼ 2.47, SD ¼ 0.88). However, this range restriction could only prevent us from detecting statistically significant effects, so our results are likely to be conservative tests of our hypotheses. Second, it is important to point out that small effect sizes are not uncommon

for interactions (Aguinis, Beaty, Boik and Pierce 2005). Moreover, even small effect sizes can have an important practical influence (e.g. Abelson 1985; Prentice and Miller 1992; Aguinis et al. 2005). For instance, recent reports suggest that workplace deviance costs the US economy billions of dollars annually, with the phenomenon being in constant increase in recent years (Bowling and Gruys 2010). In addition, workplace deviance is associated with a large variety of negative effects, costs for which cannot always be estimated. For example, reduced productivity, worsened work climate, damage to the organization’s reputation, elevation of turnover rates, and decline in employee motivation and commitment are common types of damage caused by workplace deviance (Penney and Spector 2005). Further, business failures may also happen when employee deviance spreads over the organization and managers are no longer able to ensure that instructions are followed (Jones 2009).

Finally, we were unable to control for some personality (e.g. conscientiousness and agreeableness) in explaining deviant behavior at work. Although our control variables included individual demographical characteristics and NA, ideally we might control for predispositions that influence workplace deviance. Future research should consider this possibility.

Suggestions for future research

Some research suggests that some forms of deviance are in fact influenced by factors beyond organizational walls (Bennett and Robinson 2003). One contextual factor that might impact deviant behavior at work is national culture. The Taiwanese culture is rated as relatively high on the dimensions of power distance and uncertainty avoidance, very high on the dimensions of collectivism and long-term orientation, and relatively low on the dimension of masculinity compared to other countries (Hofstede 1980b; Hofstede and Bond 1988). Based on Confucian philosophy and along with collectivism, the social context plays a more crucial role in Asian societies. In comparison to a Western, more individualistic context, a collectivistic context puts more emphasis on interpersonal relationships. This is because maintaining relatedness and adjusting one’s behavior to others is an important cultural value for collectivists (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Taiwanese place a high value on smooth interpersonal relations, and believe that social harmony is best maintained by avoiding any unnecessary friction. They consider it poor form to show anger, impatience, or dissatisfaction, and place high importance on soothing and nurturing behavior, which will make the counterpart more comfortable. Moreover, Taiwanese tend to be fearful of losing face, follow the group norms, and would rather not to be alienated from the group. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that group norms in typical Taiwanese organizations should discourage employees to commit WDB. Further research on antecedents of workplace deviance should take national culture into account.

To expand on the current findings, the moderating roles of other situational variables can be discussed in future research. These include peer influence and leadership style (e.g. socialized charismatic leadership; Brown and Trevin˜o 2006). For example, an individual’s peers have been found to influence unethical behavior. They may be others within the organization or lateral others in the field but employed by other organizations. Peers’ ethical beliefs play a significant role in determining members’ ethical behavior, especially when group members have frequent and intense contact (e.g. Zey-Ferrell, Weaver and Ferrell 1979; Zey-Ferrell and Ferrell 1982). As a result, the effects of peer

influence may moderate the relationships between general ethical judgments and workplace deviance.

In addition, given the stated importance of interpersonal justice as a predictor of deviant behavior, it is imperative to understand why this relation occurs (Sutton and Staw 1995). Studies have examined or discussed potential mediators of the interpersonal justice – workplace deviance relation. For example, arguing that workplace deviance may be a form of adaption to (or withdrawal from) a dissatisfying job. Judge, Scott and Ilies (2006) present evidence supporting their contention that interpersonal justice influences workplace deviance through job dissatisfaction. Moreover, Yang and Diefendorff (2009) suggested that supervisor interpersonal injustice will lead to CWB-I (counterproductive work behavior directed at individuals) through the experience of negative emotions. Episodes of supervisor interpersonal injustice may lead employees to experience ‘white-hot’ emotions such as anger, bitterness, and resentment (Barclay, Skarlicki and Pugh 2005). Feeling such negative emotions (Fitness 2000) may lead subordinates to act aggressively toward others at work. Thus, IJ may influence workplace deviance (especially on interpersonal deviance) through employees’ job satisfaction and/or negative emotions. In addition to the moderating role of IJ, future research should further investigate the indirect effects between IJ and workplace deviance.

Conclusion

Recent research has highlighted the importance of understanding deviant behavior in the workplace. Although progress has been made in understanding how personality traits (e.g. Colbert et al. 2004) and perceptions of the work situation (e.g. Lee and Allen 2002) are related to workplace deviance, little research has examined the relationship between individual differences in ethical judgments and workplace deviance, and how perceptions of the work situation moderate such relationships. Our model proposes that employees with less moral thoughts or beliefs may exhibit deviant behavior; however, this relationship may be enhanced or suppressed depending on employees’ perceptions of the work situation. That is, employees who perceive a favorable work situation are less likely to exhibit deviant behavior, even when provoked. This study contributes to relevant literature by linking individual general ethical judgments to deviant behaviors in the workplace and examining the moderating effects of the work situations of POS and IJ. The results showed that employees who had the judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities and/or the judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others were more likely to exhibit interpersonal and organizational deviance. Employees who had the judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions were more likely to exhibit interpersonal deviance only. Furthermore, perceptions of the work situations moderated the relationships between ethical judgments and interpersonal deviance such that certain ethical judgments were more strongly related to interpersonal deviance when either POS or IJ was low. These findings suggest that understanding individual differences in ethical judgments and underscoring positive perceptions of the work situation appear useful for the management of this costly behavior. Further research should examine additional moderating variables (e.g. national culture) to further clarify how general ethical judgments and workplace deviance are related.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by grant NSC 95-2416-H-009-017 from the National Science Council of Taiwan, ROC.

References

Abelson, R.P. (1985), ‘A Variance Explanation Paradox? When A Little is a Lot,’ Psychological Bulletin, 97, 128 – 132.

Aguinis, H., Beaty, J.C., Boik, R.J., and Pierce, C.A. (2005), ‘Effect Size and Power in Assessing Moderating Effects of Categorical Variables Using Multiple Regression: A 30-year Review,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 94 – 107.

Akaah, I.P., and Riordan, E.A. (1989), ‘Judgments of Marketing Professionals about Ethical Issues in Marketing Research: A Replication and Extension,’ Journal of Marketing Research, 26, 112 – 120.

Ambrose, M.L., Seabright, M.A., and Schminke, M. (2002), ‘Sabotage in the Workplace: The Role of Organizational Justice,’ Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 947 – 965.

Anderson, J.C., and Gerbing, D.W. (1988), ‘Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach,’ Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411 – 423.

Aquino, K., Lewis, M.U., and Bradfield, M. (1999), ‘Justice Constructs, Negative Affectivity, and Employee Deviance: A Proposed Model and Empirical Test,’ Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 1073 – 1091.

Barclay, L.J., Skarlicki, D.P., and Pugh, S.D. (2005), ‘Exploring the Role of Emotions in Injustice Perceptions and Retaliation,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 629 – 643.

Baron, R.A., and Neuman, J.H. (1996), ‘Workplace Violence and Workplace Aggression: Evidence on Their Relative Frequency and Potential Causes,’ Aggressive Behavior, 22, 161 – 173. Baron, R.A., Neuman, J.H., and Geddes, D. (1999), ‘Social and Personal Determinants of Workplace

Aggression: Evidence for the Impact of Perceived Injustice and the Type A Behavior Pattern,’ Aggressive Behavior, 25, 281 – 296.

Bennett, R.J., and Robinson, S.L. (2000), ‘Development of a Measure of Workplace Deviance,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 349 – 360.

Bennett, R.J., and Robinson, S.L. (2003), ‘The Past, Present and Future of Workplace Deviance Research,’ in Organizational Behavior: The State of the Science (2nd ed.), ed. J. Greenberg, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 247 – 281.

Berry, C.M., Ones, D.S., and Sackett, P.R. (2007), ‘Interpersonal Deviance, Organizational Deviance, and Their Common Correlates: A Review and Meta-Analysis,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 410 – 424.

Bies, R.J. (2005), ‘Are Procedural Justice and Interactional Justice Conceptually Distinct?’ Handbook of Organizational Justice, eds. J. Greenberg and J.A. Colquitt, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 85 – 112.

Bies, R.J., and Moag, C.L. (1986), ‘Interpersonal Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness,’ Research on Negotiations in Organizations, 1, 43 – 55.

Bies, R.J., and Tripp, T.M. (2001), ‘A Passion for Justice: The Rationality and Morality of Revenge,’ in Justice in the Workplace: From Theory to Practice (Vol. 2), ed. R. Cropanzano, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 197 – 208.

Bowling, N.A., and Gruys, M.L. (2010), ‘Overlooked Issues in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Counterproductive Work Behavior,’ Human Resource Management Review, 20, 54 – 61.

Brass, D.J., Butterfield, K.D., and Skaggs, B.C. (1998), ‘Relationships and Unethical Behavior: A Social Network Perspective,’ Academy of Management Review, 23, 14 – 31.

Brockner, J. (2002), ‘Making Sense of Procedural Fairness: How High Procedural Fairness Can Reduce or Heighten the Influence of Outcome Favorability,’ Academy of Management Review, 27, 58 – 76.

Brockner, J., DeWitt, R.L., Grover, S., and Reed, T. (1990), ‘When It is Especially Important to Explain Why: Factors Affecting the Relationship Between Managers’ Explanations of a Layoff and Survivors’ Reactions to the Layoff,’ Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 389 – 407.

Brown, M.E., and Trevin˜o, L.K. (2006), ‘Socialized Charismatic Leadership, Values Congruence, and Deviance in Work Groups,’ Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 954 – 962.

Burton, J.P., Mitchell, T.R., and Lee, T.W. (2005), ‘The Role of Self-Esteem and Social Influences in Aggressive Reactions to Interactional Injustice,’ Journal of Business and Psychology, 20, 131 – 170.