One Step Forward, One Step Backward:

Chen Shui-bian’s mainland policy

CHIEN-MIN CHAO1

Chen Shui-bian has been lauded for his moderation in handling cross-Strait relations but reviled for his vacillation. The most evident case of Chen’s unsteadiness is the President’s position on the issue of ‘one China’. He has been running the gamut from ‘future China’ to the latest ‘accepting one China is equivalent to the end of the ROC’. This lack of consistency can be explained by factional politicking within the DPP. Since the DPP was created in 1986, it has been quite evident that the party has been polarized into two major factions, the Formosa faction and the New Tide faction. The radical wing got the upper-hand as the overseas independence advocates started to flow back at the beginning of the 1990s. A few years later, the party started to change on its stand on Taiwan independence. The humiliating defeat of the DPP candidate Peng Ming-min in the 1996 presidential election prompted further transition. In the meantime, the weakening of the moderate wing in the DPP put Chen in a very difficult position. The party’s leadership on the left had constantly warned their followers of

self-destruction should the principle of ‘one China’ be accepted.

Concerns were raised when Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was elected President of Taiwan in March 2000, because of his proindependence stand. On the eve of the election, Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji warned Taiwan voters to think twice

before casting their ballots for the ‘candidate of independence’ lest they regret it afterwards.2

A year and half after the stunning election, relations across the Taiwan Strait have seemingly been stabilized. The President’s party, the DPP, managed to dislodge the KMT as the single largest party in the parliament after the election at the end of 2001. Yet the relatively calm facade can hardly conceal the tensions beneath. While commenting on the results of the election, a spokesman from Beijing’s Office of Taiwan Affairs reiterated the old policy that Chen and his administration would have to return to the ‘one China’ principle before contacts

could be resumed between the two.3

1

Dr Chien-min Chao is Professor at the Sun Yat-sen Graduate Institute for Social Sciences and Humanities, National Chengchi University, and Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore. The author is grateful to Professor John Wong and Professor John Copper for their valuable comments and suggestions. He would also like to thank Mr Aw Beng Teck for his editorial assistance.

2

Zhongguo shibao (Taipei), (16 March 2000), p.1.

3

Chen has been lauded for his moderation and caution in handling cross-Strait relations. On the campaign stump, candidate Chen struck a conciliatory tone bysaying that ‘Taiwan is a

de facto sovereignty and its name is ROC according to the Constitution4.This was considered

a major break from the belligerent independence rhetoric the party had held previously. In his inaugural address, President Chen tried to calm critics skeptical about his intentions by

pledging ‘five nos’.5The new administration under his leadership would not: declare

independence, abrogate the official name of the country, incorporate the ‘state-to-state theory’ into the constitution, hold a referendum on the issue of independence, or revoke the National Unification Guidelines and eliminate the National Unification Council (NUC). In an address delivered on New Year’s Day 2001, Chen surprised many when he proposed that the two sides should base their efforts on economic, trade and cultural integration and strive for a new

framework of ‘political integration’ and eternal peace.6

Beijing has not yet reciprocated these conciliatory gestures. Actually, Beijing seems to have concluded that, notwithstanding the rhetoric, Chen is essentially leading Taiwan

gradually toward independence.7 One reason for this view is the vacillation that has

characterized Chen’s China policy, in which he has often retracted things that he has said, sometimes almost immediately afterwards.

As an opposition parliamentarian, Chen was known to have rejected the ‘one China’ principle—claiming that it was the People’s Republic and had nothing to do with Taiwan. In the run-up to the presidential election, candidate Chen promised that once in office the issue could be put on the negotiation table. Since taking office, however, he has been running the gamut from a ‘future one China’, to ‘one China, different interpretations’, to the latest ‘there is no problem with the issue of China according to the ROC constitution’. His assertion that there was only a ‘spirit of pursuing negotiation to resolve problems’ rather than ‘consensus with regard to the “one China” issue’ at a 1992 meeting between representatives of the Strait Exchange Foundation (SEF) and Association of Relations Across the Taiwan Strait (ARATS)

confounded the issue even more.8

This lack of consistency can of course be explained by the DPP’s lack of experience in governing. The party has had difficulty convincing people that it is mellow enough to warrant a safe environment in the Taiwan Strait area. The problem is further complicated by the fact that Chen garnered only just over 39% of the popular vote (less than three percentage points above another candidate) in the election and that his administration has to face, at least at the

4

Zhongguo shibao, (21 May 2000), p.4.

5

Lienho bao (Taipei), (21 May 2000), p.2.

6 Zhongguo shibao, (2 January 2001), p.1. 7

Ming Bao (Hong Kong), (4 June 2001), p.A12.

8

In preparation for the historic summit between the two heads of the semi-official SEF and ARATS, representatives of the two organizations met in November 1992 to discuss the agenda. It was agreed that the ‘one China’ principle be expressed with their respective interpretations. After the agreement, the summit was able to take place in April 1993.

outset, a parliament, the Legislative Yuan, in which his party maintains barely a third of the seats. It is this reorientation from a politics-centered party to suit an economic centered

society that the party feels most uneasy.9

But this article argues that it is the DPP’s factional maneuvering that has been the essential driving force behind Chen’s indecisiveness. The article will explore the DPP’s factional past amid the debates concerning policies towards the mainland in which the party has engaged itself. The article will conclude by suggesting that the reason behind Chen’s failure to break the stalemate in relations across the Strait of Taiwan as he promised on the campaign road is mainly caused by opposition coming from the fundamentalist Taiwan independence advocates who do not want to give up the independence stand that they had held previously.

Factionalism as an ingrained problem for the DPP

One of the major goals of the DPP has been the creation of a new Taiwan identity. However, the party has been dogged from the very beginning by a binary vision on this particular issue, one for immediate independence and the other for a more relaxed policy.

The opposition movement started out as some members participated in the electoral process and became representatives of assemblies and local government administrators. Starting from the late 1970s magazines became major venues for the opposition. Among them, the most influential one was The Formosa Magazine. The magazine started publishing in August 1979 and reached a circulation of around 100,000. The focus of the monthly magazine was on democracy and to most of the contributors this seemed to be easy to combine with a Chinese identity. It was even a common claim that a better democracy might be molded out of

Taiwan by combining with Chinese culture.10For them, all people in Taiwan had at one point

immigrated to the island from the mainland and thus, should strive together towards freedom and happiness. Four months later, a violent riot broke out in the southern port city of

Kaohsiung following a demonstration organized by the Formosa group to commemorate

Human Rights Day.11Consequently, most of the leaders of the magazine were arrested and

put in jail.

In the years 1984 and 1985 there was a surge of opposition magazines. One of these magazines had the English title The Movement (xincaoliu, or the new tide). The magazine did

9 See Chien-min Chao, ‘Opportunities amid crisis: mainland policies under President Chen Shui-bian’,

paper presented at the Fourth ASEAN—ISIS/IIR Dialogue on ASEAN—Taiwan and Human Security Issues: Coping with Globalization, Taipei, 11–14 January 2001.

10

Meilidao. [Formosa] (Taipei), 1, (1979), p.2.

11 The event erupted after the severance of diplomatic relations with the Untied States earlier that

year. Consequently, 183 policemen were injured and a number of well-known opposition political figures were convicted and sentenced to prison. A compromise was reached between the government and the opposition and an election washeld in December 1980, which became a watershed event in Taiwan’s political development. See John F. Copper, Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China), second edition (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2000), pp. 105–106.

not have a circulation of a size close to that of The Formosa, but it had many important opposition politicians on its editorial board. The Movement introduced a new view on the status of Taiwan identity. Taiwan was now to a larger degree an integral part of the world as opposed to being a mere part of the Chinese cultural sphere. Democracy was still important but Taiwan independence and the role of the Taiwanese as victims of the arbitrariness of the

mainlanders had become a far more prominent concern.12

By the time the DPP was formed and convoked its first congress in 1986, it was the Kan Ninxian, a member of the Legislative Yuan, and his faction, the moderates, and the New Tide faction (xincaoliu xi), members basically from The Movement magazine, radical in ideology, took the lion’s share. The Formosa faction (meilidao xi), formed by families and defense lawyers (including Chen Shui-bian and Frank Xie, the current Chairman of the Party) of the Kaohsiung Incident was marginalized due to the fact that most of its leading persons were imprisoned serving time after the Kaohsiung Incident. The release of two prominent DPP figures Huang Xinjie and Zhang Junhong, who had served time for the 1979 Kaohsiung

Incident, in May 1987, benefited the moderate Formosa faction,13 setting the stage for a party

in which three major factions would dominate the internal policy debates.

But the legacy of the Kaohsiung Incident and the fact that almost all senior DPP leaders were members of the faction make the Formosa faction the most dominant force to reckon with. The situation did not change until 1991 when the overseas independence movement based in the United States was allowed to return. By allying with these overseas independence fundamentalists, who were extreme militants as they would not rule out violent revolution as a means to fulfill their goals, the radical New Tide faction finally became the most dominant force at the Fifth DPP Party Congress held in October 1991.

In order to compete for political resources two new minor factions were formed in 1992 that played a conciliatory ‘third party’ role. Then legislator Chen Shui-bian split from

Formosa in that year and formed, together with Annete Lu, now the Vice President, his own Justice Alliance, and Frank Xie, who had been close to the radical New Tide, coalesced with a few heavyweights including Yao Jiawen (former DPP Chairman elected at the Second Party Congress in 1987) and Shi Mingde (former DPP Chairman elected at the Sixth Party

Congress in 1994), and formed the Alliance for Laissez-faire Nation, for the purpose of the year-end election in the Legislative Yuan. The Kan Ninxian Faction, however, started to fizzle out when the party convened its third congress in 1988. A more enduring two-plus-two pattern soon emerged.

12

Jesper Zeuthen, ‘Nation and identity in Taiwan: an analysis based on examinations of the public discussion’, unpublished paper.

13

The term ‘Formosa’, which literally means a beautiful island, was invented by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century when they first saw the island, and was borrowed by Taiwan independence

advocates and became synonymous with their cause. But for the Formosa faction, their position on independence was relatively mild within the party. The term ‘xi’, which literally means ‘system’, is used by the party to substitute faction.

But an internal power struggle within the Formosa faction pitting two mostinfluential politicians and close allies Xu Xinliang and Chang Junhong against each other for the party chairmanship at the Seventh Party Congress in 1996 decimated the faction. Although Xu defeated Trong Tsai of the Alliance for Laissez-faire Nation and won the chairmanship, the faction gained only three seats from the 11-seat Central Standing Committee. The most

powerful faction of the DPP was thus reduced to the smallest (see Tables 1 and 2).14 It

became inevitable that the party was moving towards the radical end of its ideological spectrum.

14 See Liu Jinchai, Dadan xijin? Jieji yongren? Minjindang dalu zhenche poxi [Go Westward Boldly? Or

No Haste, Be Patient? An Analysis of DPP’s Mainland Policy] (Taipei: Shiying Publishing Co., 1998), p.141.

Table 1. Major factions within DPP and their key leaders, 2001

Factions Key persons

Formosa faction Huang Xinjie (former DPP Chairman, deceased)

Xu Xinliang (former DPP Chairman, withdrew from DPP) Zhang Junhong (formed his own faction the New Century)

The New Tide Faction Qiu Yiren (Secretary General, the Executive Yuan) Wu Nairen (Secretary General, DPP)

Lin Zhuoshui (member, the Legislative Yuan) Hong Qicang (member, the Legislative Yuan)

Alliance for Laissez-faire Nation Frank Xie (DPP Chairman) Yao Jiawen (former DPP Chairman)

Shi Mingde (former DPP Chairman, withdrew from the party)

Justice Alliance Chen Shui-bian (ROC President) Annete Lu (ROC Vice President)

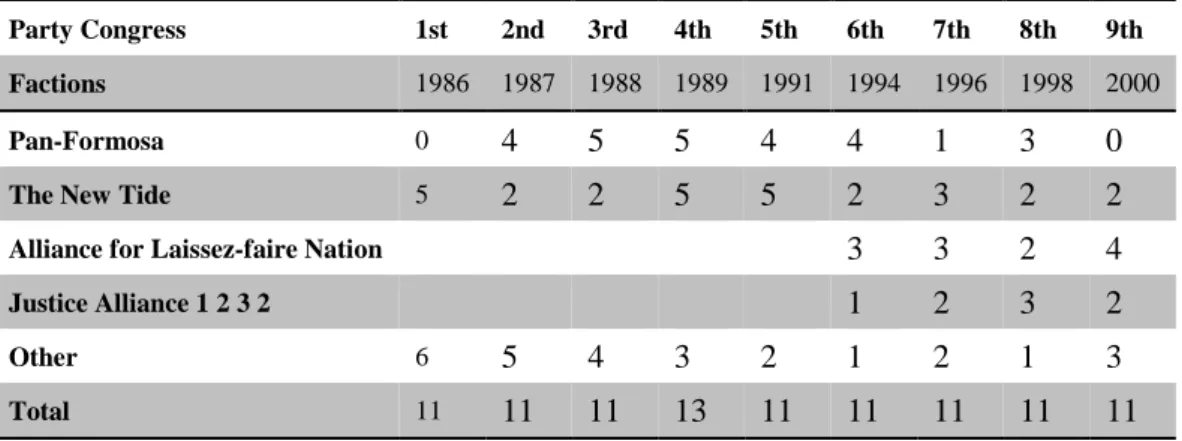

Table 2. Seats won by different factions in the DPP Central Standing Committee, 1986–2000

Party Congress 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th Factions 1986 1987 1988 1989 1991 1994 1996 1998 2000

Pan-Formosa 0 4 5 5 4 4 1 3 0

The New Tide 5 2 2 5 5 2 3 2 2

Alliance for Laissez-faire Nation 3 3 2 4

Justice Alliance 1 2 3 2 1 2 3 2

Other 6 5 4 3 2 1 2 1 3

Total 11 11 11 13 11 11 11 11 11

Sources: Huang Defu, Minjujinbudang yu taiwan diqu zhenzhi minzhuhua [DPP and Democratization in the

Taiwan Area](Taipei: Shiying Publishing Co., 1993), p. 81; Liu Jincai, Dadan xijin? Jieji yongren? Minjindang dalu zhenche poxi [Go Westward Boldly? Or No Haste, Be Patient? An Analysis of DPP’s Mainland Policy]

(Taipei: Shiying Publishing Co., 1998),

Transition towards radical independence

It is evident that from its inception the DPP has been dissected ideologically between the moderates and the radicals. The schism has centered around Taiwan’s status in relation to China. A central issue evolved from the concept of zhumin zhijie, or plebiscite by the inhabitants, in which claims shifted from the creation of a new and independent country known as the Republic of Taiwan to that of Taiwan being a de facto independent country and that there was no need to further prove its status.

On top of that, the position on Taiwan independence was not unanimous, at least not in the period before and shortly after the party was formed. Actually, suggestions for actively engaging with mainland China and even for unification were not uncommon in the early years of the opposition movement. As an opposition movement loosely bound under the ideograph ‘dangwai’ (literally out of the KMT party), the moderates, contradicting the radicals, didn’t want to challenge the ‘one China’ policy of the KMT. Nevertheless, voices were heard from both camps calling for an end to the government’s ‘three nos policies’—Taiwan would not enter any negotiations with China, nor conduct direct communications or make any

compromise with China.15

One can certainly detect political motivations behind the opposition movement’s objection to the KMT’s mainland policy. As a newly emerged political force dangwai was trying to copycat rules of party politics and some within the opposition camp believed that an end to KMT’s strict policy might alleviate to some extent the isolation that Taiwan had found itself in since severing relations with the United States in January 1979. But it also reflects the reality that the opposition movement really started out as a democracy movement and to actively engage China not only did not contradict with that goal but also might actually help with the cause. In the early years, many joined the opposition with the conviction that democracy and the end of KMT’s autocracy were worthy causes and the creation of an independent country separated from China was deviation from that conviction. It was out of this conviction to discontinue the KMT rule that the older generation of democracy fighters joined forces, mainlanders or Taiwanese. It is therefore no surprise to learn that some senior DPP politicians like Fei Xiping, Zhu Kaozhen, and Lin Zhenjie, all mainlanders and members of the Legislative Yuan once, had craved for unification, Chinese federation or confederacy in the late 1980s.16

However, as democratization gathered momentum with localization (Taiwanization) as the main driving force, things started to change. As the elements demanding unification were

15

The policy was designed by the late President Chiang Ching-kuo as countermeasures against Beijing’s new initiatives, proposed in January 1979, of direct mail, trade, and shipping and exchanges on activities in the areas of culture, athletics and the like, collectively known as the ‘three links and four exchanges’. About Beijing’s new policy, see ‘A letter to the People of Taiwan’, in Council for Mainland Affairs, ed., Dalu gongzuo cankao ziliao [Reference Materials for the Work on Mainland China] (Taipei: Council for Mainland Affairs, 1998), vol. 2, pp. 1–4.

16

gradually squeezed out of the party, differences over the pace of Taiwan independence and relations with China started to widen. At the First Party Congress in November 1986, a clause was added to the DPP charter stating that ‘the future of Taiwan should be decided by its inhabitants’. This simple statement pushed the issue of self-determination to the fore. But differences remained as to how and under what conditions a plebiscite should be used. To the moderate Formosa and its allies, self-determination was only one way to demonstrate that the people of Taiwan had the final say in choosing their destiny and independence was just one of the options; but for the radical New Tide faction, ‘self-determination’ was equivalent to

independence and had to come before any authentic democracy could be established.17

The first major test for the faction-torn decision-making process in the DPP came in 1988 when disagreements surfaced in a party congress. While debating a possible amendment to the party platform to incorporate the sensitive subject of ‘freedom of Taiwan

independence’, radicals led by party chairman Yao Jiawen demanded that the future of Taiwan ‘be handed back to its people’ and that the DPP must ‘point out a direction for the

people of Taiwan’.18 Supporters cited favorable public opinions conducted by the party

machine to bolster the inclusion. The moderate Formosa faction however called for caution and advised against any revision. Faced with this dilemma, two minor factions under the stewardships of Chen Shui-bian and Frank Xie came to the rescue with two separate

compromise proposals. In the end, a conciliatory and now famous ‘four ifs’ were conceived.19

The DPP, it was purported, reserved the right to exercise independence: (1) if the KMT and CCP entered negotiation without the DPP; (2) if the KMT betrayed the interests of the Taiwan people; (3) if the CCP attempted to conquer Taiwan by force; and (4) if the KMT refused to implement authentic democracy.

Taiwan’s democratic experiment received a boost with the arrival of the new native president Lee Teng-hui in 1988 and a new wave of democratization among the former socialist states in East Europe and the Soviet Union, hastening change in the DPP at the turn of the 1990s. Consequently, the party took a drastic turn towards radicalization, strengthening the New Tide faction in the process.

It was obvious that the influences of the New Tide and the ‘third force’ comprising the two minor factions were on the rise at the expense of the previously dominant Formosa faction (see Table 2). The return of the more radical independence advocates at the beginning of the 1990s from abroad further tipped the balance. The legislative and national assembly elections held in 1991 and 1992, in which the old ‘10,000-year parliament’ (wannien guohui)

17

Huang Defu, Minjujinbudang yu taiwan diqu zhenzhi minzhuhua [DPP and Democratization in the Taiwan Area] (Taipei: Shiying Publishing Co., 1993), pp. 118–121.

18 Minjin Bao (Taipei) 7, (23–29 April 1988), pp. 16–22. 19

Department of China Affairs of the DDP, Minzhu jinbudang lianan zhenche zhonyiao wenjian huibian [Compilation of Important Documents of the DPP], undated, p. 4.

was structurally rejuvenated, helped boost the confidence of the young political party.20 Externally, factors converged to give rise to unrealistic expectations out of which a radical Taiwan nationalism was conceived and nurtured. These factors included the aversion of the international community displayed towards China after the suppression of the student movement in the Tiananmen Square in 1989, the collapse of the former Soviet Union, and the relative improvements of Taiwan’s standing internationally, manifested by the sale of the F-16s by the Bush Administration in 1992 and the subsequent revision of its Taiwan policy by

the Clinton Administration in 1994.21 These factors congregated to give a false sense of

euphoria to some in Taiwan that the time was ripe to start a new nation. Over the next few years, the radical New Tide faction displaced the Formosa faction to become the most

dominant faction within the DPP. Consequently, overtures made by the party’s top echelon to China were irrevocably reversed.

The first sign of this sea change surfaced in 1990 when the radicals decided to redefine the sovereignty of the country at the Second Central Committee Plenum Meeting of the Fourth Party Congress so that a more disparate identity could be carved out vis-a`-vis China. To counter China’s ‘one country, two systems’ offensive and to show its disapproval of the newly-created National Unification Council by the KMT government, the New Tide faction pressured the government to declare that the sovereignty of Taiwan ‘does not extend to the Chinese mainland and Outer Mongolia’, and to urge the PRC to publicly recognize Taiwan as a sovereign country. In the end, a resolution was passed granting the exclusion but using a

less abrasive phrase ‘de facto sovereignty’, rather than the original ‘sovereignty’.22

The first major transition came in August 1991 when the newly-formed DPP adopted a draft constitution for the future new country it called the ‘Republic of Taiwan’. This was a major step towards severing relations with China and achieving the status of de jure independence.

Two months later at the Fifth Party Congress, Lin Zhuoshui, a parliamentarian deemed as the foremost Taiwan independence theorist, proposed revising the party platform on behalf of the New Tide faction. It called for ‘establishing a fully independent sovereign nation by the

name of the “Republic of Taiwan”’.23 Xu Xinliang, a heavyweight from the Formosa faction

20

After the end of the Sino—Japanese War, a constitution was promulgated in 1946 by the Nationalist government and elections were held to choose representatives for the Legislative Yuan, the Control Yuan and the National Assembly in the next few years. But since retreating to Taiwan in 1949 there had been only a few ‘supplementary elections’ held to fill a few vacancies left by

representatives who had passed away and no elections had been held to replace the whole chamber due to the issue of legitimacy. The elections in 1991 and the following year were the first elections in which all positions in the Legislative Yuan and the National Assembly were up for grabs.

21

See James Mann, About Face: A History of America’s Curious Relationship with China, from Nixon to Clinton (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), ch. 17.

22 Zhongkuo shibao, (8 October 1990), p.3. 23

Lin Zhuoshui, ed., Lu shi zheyang zhou chulai de [Roads Are Created This Way] (Taipei: Qianwei Publishing Co., 1992), pp. 89–91.

campaigning for the party chairmanship, reversed a long-held position favoring de facto independence and endorsed the radical proposition in order to garner support from the

opposition camp.24

The Congress then passed a resolution proposed by Chen Shui-bian to include the notorious ‘independence clause’ in the platform and added a condition requiring a plebiscite before a new sovereign country was formed. It was further decided that the term CCP referred to in the party platform should contain a more ‘sovereign’ idea encompassing the People’s Republic of China. These might have been the greatest changes made in the party’s short history of less than two decades. From then on the party was stigmatized as a party for independence. The DPP had thus shifted from a more innocuous position advocating a ‘plebiscite by the inhabitants of Taiwan’ without stating any presupposed conclusion regarding independence, to one embodying a fanatical Taiwan nationalism in which

nation-building was preeminent.25 From then on, the issue of sovereignty and the creation of a

new identity dominated the debates within the party. The radicalization of the party forced some moderates to beat a retreat. By June of 1991, people like Fei Xiping, Zhu Kaozhen, and Lin Zhenjie who had the ‘greater China thinking’ by calling for unification, Chinese

federation or confederacy, had cited prevalence of Taiwan independence thinking within the

party as the reason of bowing out of the party.26

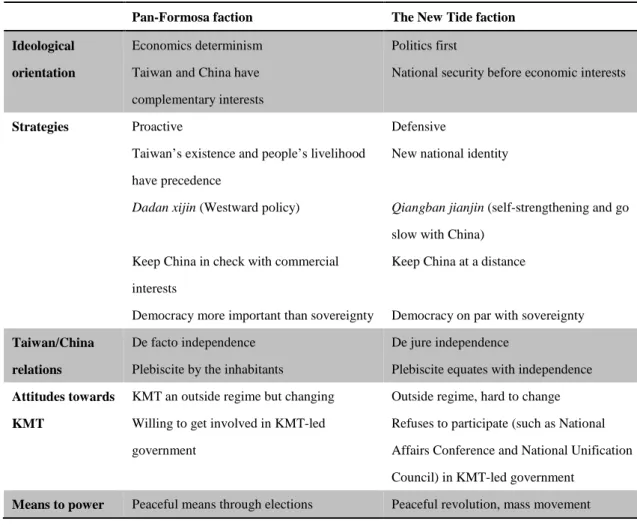

At that moment, it is ultra-clear that there were two forces within the DPP competing for both ideological as well as political supremacy (see Table 3). For the moderate pan-Formosa and its allies, economic relations with the Chinese mainland were critically essential to the island’s future and Taiwan should take advantage of the geographic proximity and the complementary nature of the two economies and work to its benefits. Equipped with a free market economy and liberal democracy Taiwan should be confident to expand westward (dadan xijin). As for political relations with China, Taiwan was quite content with its de facto sovereign status. Should there be any change of that status in the future, it would be decided by all the inhabitants of the island through a comprehensive mechanism of plebiscite.

For the radical New Tide faction, to create a separate Taiwanese political identity distinct from that of China’s was the most important task for the people of Taiwan. In order to realize that goal China should be kept at a distance, economically or otherwise. What Taiwan ought to do, according to this group of people, was to strengthen itself and with it to withstand the unification pressure coming from the other side of the Taiwan Strait. So the policy of

24

Zhili zhaobao [Independence Morning Post], (26 August 1991), p. 3.

25

Julian J. Kuo, Minjindang zhuanxing zhitong [The Pain of Transition with the DPP] (Taipei: Commonwealth Publishing Co., 1998), p. 115.

26 Fei Xiping withdrew from the DPP in December 1988, citing strong independence and fascist way of

thinking contradicting with democratic goals set by the party; Zhu Kaozhen disavowed party membership in August 1990, accusing the New Tide of being an infectious AIDS disease and that localization should not be based on negation of the Chinese culture; Lin Zhenjie complained that the party disallowed freedom of not supporting Taiwan independence. See Liu Jinchai, Dadan xijin?, p. 178.

qiangban jianjin (self-strengthening and go slow with China) was affirmed. KMT was indeed

an ‘outside regime’ and for that the party should try its best to avoid having any relations with it. To stay put and maintain the status quo was far from enough. Taiwan needed to strive for the establishment of an internationally recognized sovereignty.

Table 3. Ideological differences between moderates and radicals

Pan-Formosa faction The New Tide faction Ideological

orientation

Economics determinism Taiwan and China have complementary interests

Politics first

National security before economic interests

Strategies Proactive

Taiwan’s existence and people’s livelihood have precedence

Dadan xijin (Westward policy)

Keep China in check with commercial interests

Democracy more important than sovereignty

Defensive

New national identity

Qiangban jianjin (self-strengthening and go

slow with China) Keep China at a distance

Democracy on par with sovereignty

Taiwan/China relations

De facto independence Plebiscite by the inhabitants

De jure independence

Plebiscite equates with independence

Attitudes towards KMT

KMT an outside regime but changing Willing to get involved in KMT-led government

Outside regime, hard to change Refuses to participate (such as National Affairs Conference and National Unification Council) in KMT-led government

Means to power Peaceful means through elections Peaceful revolution, mass movement

From ‘old independence’ to ‘new independence’

The radical and militant bent of the DPP in the early 1990s had met with resistance from both within and without the party, prompting a rethink of the strategy.

The first challenge came from a reinvigorated and rejuvenated KMT. After a shaky start, President Lee Teng-hui gradually consolidated his power base against the old-guards within his party. Lee’s drive to democratize Taiwan and the localization initiative innate in the process blurred the heretofore ideological differences between the party he was leading and the biggest opposition party, the DPP. To the latter, the KMT was no longer an ‘outside regime’ run by a few elite fleeing from China and estranged from the masses. Lee’s

expressions such as ‘sad to be a Taiwanese’,27 ‘the new Taiwanese’,28and ‘popular

27

President Lee made the argument in an interview with a Japanese journalist of the Sankei Shimbun, Ryotaro Shiba.

sovereignty’ were greeted with trepidation by the DPP as they saw their legitimacy platform being hijacked by the KMT.

On the other hand, the radicalization of the DPP as well as Lee’s localization drive deepened the misgivings of right wingers in the KMT over the direction in which Taiwan was heading. The founding of the Chinese New Party (later the New Party) in August 1993 and the subsequent election for the mayor of Taipei brought ethnic confrontation to a new height. The intensity of the ethnic confrontations flared in the campaigning; and at the first direct presidential elections in 1996, the DPP was forced to make another round of adjustment. The defeat of the DPP candidate Peng Ming-min in the presidential election and the firing of missiles near Taiwan shores by Beijing on the eve of the election were catalysts for the change.

The moderates were worried about the emergence of radicalism. Former Party Chairman Xu Xinliang broached the idea of a new Taiwan nationalism in an attempt to differentiate it from the old type of nationalism. The old nationalism, according to Xu, was defensive, timid and full of hatred, while the new one was based on self-confidence, open-mindedness, and aggressiveness. Xu questioned the wisdom of building a new nation in the light of Taiwan’s tumultuous relationship with its giant neighbor, China. The key to Taiwan’s future, Xu argued, was to forge a close bond between the people and the government through economic means

so as to suppress the old problem of identity.29

Xu’s arguments set the motion for a new round of debate within the DPP, and the old paradigm of Taiwan independence gradually gave way to a new line of argument in which pragmatism was added to the equation for the first time. The well-being of the people of Taiwan and the building up of the island’s aggregate strength were elevated on a par with sovereignty as major DPP concerns in strategizing Taiwan’s relations with its neighbor across the Strait.

The most dramatic change came when Shi Mingde, then Party Chairman and once a die-hard radical independence advocate, made a shocking announcement while visiting the United States in September 1995 that once in power, there was ‘no need for the party to declare independence’. This triggered a second round of debate over the party’s stand on independence and national identity. Some deemed the announcement as a ‘paradigmatic

revolution’ in the evolution of the movement for Taiwan independence,30 and the forsaking of

the old conviction of seeking a new sovereign entity. Even Lin Zhuoshui felt compelled to rephrase his previous position by saying that ‘sovereignty is already independent but the goal

28

President Lee coined the term in 1998 during the Taipei mayoral election. It was believed that the invention had helped KMT candidate Ma Yinjiu, a second generation of mainlander, win the election over the DPP opponent Chen Shui-bian, a native Taiwanese.

29

Xu Xinliang, Xin taiwanren [The Rising People] (Taipei: Yuanliu Publishing Co, 1995).

30

of nation-building is yet to be fulfilled’.31

The new theory called for an end to the old position that Taiwan’s status remained open after Japan ended its colonial rule. To bring down the political establishment was no longer a priority; nor was it a priority to build a new country. Instead, crafting a new image more appealing to the majority of the local voters took precedence, even as the DPP started preparing for a possible power changeover.

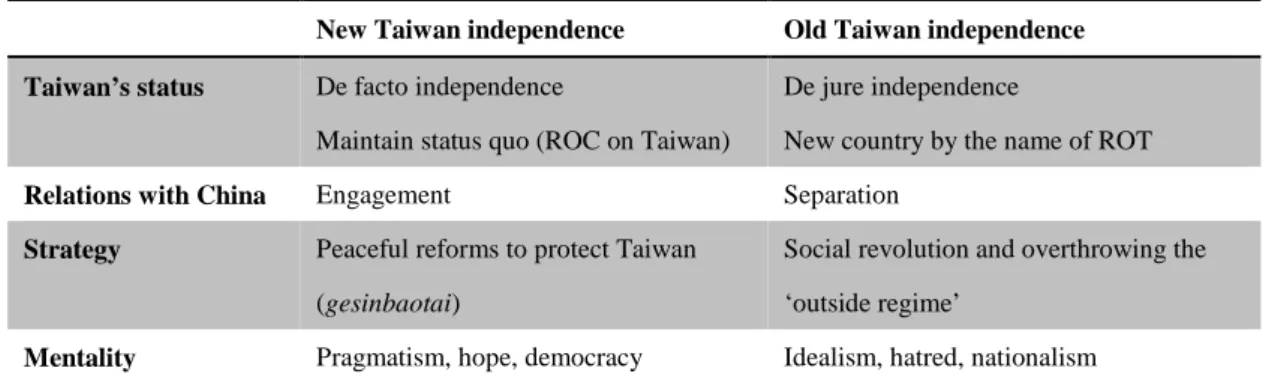

DPP candidate Peng Ming-min’s humiliating defeat in the 1996 presidential election, getting only 21% of the popular votes cast, was what prompted this round of transition. Deputy Director of the DPP Cultural Department Zhou Yizen issued the ‘Program of Taiwan Independence for the New Generation’ in May 1996, challenging the ‘old Taiwan

independence’ publicly. As Zhou contended, Taiwan independence should not be based on hatred towards China, or towards the ‘regime from outside’ (meaning the KMT), nor on the

creation of a new name and flag.32 In other words, the goal of Taiwan independence should

not be promoted because of an unrealistic dream; rather, it should be pursued because of the utilities, if there were any, that it is going to bring to the people of Taiwan. Therefore, with a pragmatical attitude of engaging China with a wholesome mentality of hope and pride, the people of Taiwan could overcome the hatred endowed on them by unfortunate historical events. It was time to bid farewell to the idealistic Taiwanese nationalism and embrace democracy, something the opposition had been fighting for decades. Maintenance of the status quo thus emerged as the new consensus among the younger generation of the DPP. Table 4 shows the metamorphosis of Taiwan independence in the mid-1990s. The changes were very much a reflection of the factional divergence in the party.

It is apparent that electoral concerns were the catalysts behind the transition. But

external pressures had no doubt also helped facilitate the change. President Bill Clinton’s visit to China in 1998 and the reaffirmation of the ‘three nos policy’ (the US would not support Taiwan independence; one China, one Taiwan; nor would the US lend support to Taiwan’s quest for membership in international organizations with statehood as a requirement) disheartened the Taiwanese. This prompted the DPP Central Standing Committee to issue a statement reaffirming Taiwan as a de facto sovereignty and that any change of that status would require popular balloting. The notorious ‘plebiscite for independence’ was thus recast as a ‘referendum for unification’.

31

Zhongkuo shibao, (8 July 1998), p. 15.

32‘Taiwan minzhu yundong de xinshidai gangling’, [‘Program of Taiwan independence for the new

Table 4. A comparison of the old and the new independence movements

New Taiwan independence Old Taiwan independence Taiwan’s status De facto independence

Maintain status quo (ROC on Taiwan)

De jure independence

New country by the name of ROT

Relations with China Engagement Separation

Strategy Peaceful reforms to protect Taiwan (gesinbaotai)

Social revolution and overthrowing the ‘outside regime’

Mentality Pragmatism, hope, democracy Idealism, hatred, nationalism

DPP victory and reformation of factions

Chen’s unexpected victory and the DPP becoming the ruling party have fundamentally altered the party’s factional configuration and hence, its modus operandi. For the first time in the party’s history, there is a person who commands authority above factions.

However, the restructuring appears to be in form rather than in substance. As head of a minority government, President Chen had wanted to organize an administration on a

non-partisan basis, a ‘cabinet of all people’ (quanmin neige). The decision to pick General Tang Fei of the KMT as the Premier was evidence of that policy. Faced with strong

opposition from the KMT-dominated Legislative Yuan, Chen had wanted to build a working alliance with opposition KMT legislators sharing a similar ideology.

Unfortunately, these policies did not receive unanimous support from within the DPP. Consequently, Chen was forced to accept Tang Fei’s resignation to take the blame for the

flip-flop over the construction of the fourth nuclear power plant.33

Restrained by factional considerations and hindered by the fact that the radical New Tide faction had the lion’s share in the power game as it held many important positions such as the secretary generalship of both the party and the cabinet, the President has balked from making resolute decisions. The flip-flops have

undoubtedly provided ammunition for Chen’s opponents, fermented new resentment across the Strait and created alienation within his own party.

The weakening of the moderate wing in the DPP has put Chen in a very difficult

position. Former Party Chairman Xu Xinliang, a major force in the Formosa faction, resigned from the party to take part in the 1996 presidential election, only to lose to Peng Ming-min in the primary. Some heavy-weights within the faction, including Zhang Junhong, split from the faction to form the New Century faction in 1998 because of dissatisfaction with the party’s

33 As an opposition party, the DPP had thrown its support behind the residents of Gongliao, a rural

town on the fringe of the Taipei city, in their fight against the KMT government’s decision to build the fourth nuclear power plant there. After becoming the ruling party, the party immediately took action to revoke the construction although it was understood that 30% of the project was already completed with roughly US$3 billion of money spent. After a strong resistance from the KMT with a threat to proceed with the recalling of the president with a popular vote, the DPP finally backed off.

strategy to ally with the KMT and its engagement policy with China designed by Xu. The Formosa faction eventually ceased to be a credible political force (see Table 1). Today, faced with a single-dominant faction with a radical ideology, Chen Shui-bian’s hands are tied.

To show support for the President and to better position themselves for maximal political gains, four small factions formed the Mainstream Alliance faction soon after the election. The dominant New Tide faction and the New Century faction, a weak remnant of the

once mighty Formosa, coalesced to form a second power block.34 But the redrawing of the

factional map did not resolve the chronic problem of intra-party differences.

Factionalism and Chen Shui-bian’s China policies

Chen Shui-bian’s policies toward mainland China have to be understood in the context of factional politics within his own party. The first casualty was the party’s policy towards the ‘one China’ issue. The Resolution on the Future of Taiwan, passed at the Second Plenary Meeting of the DPP Eighth Party Congress in May 1999, stated unambiguously that Taiwan should forsake the ‘one China’ principle to avoid confusing the international community and to avoid facilitating a hostile takeover by the PRC. The party’s leadership on the left had constantly warned their followers of self-destruction should the principle be accepted. The President had on different occasions described himself as ‘ethnic Chinese’, dodging the term ‘Chinese’.

Dr Lee Yuanze, the highly respected head of Academia Sinica who was believed to have helped tip the balance towards Chen at the last moment of the presidential election campaign by publicly throwing support behind him, was scorned by the DPP hard-liners when the Cross-Strait Cross-party Advisory Group (CCAG), a task force commissioned by the President to formulate consensus under Lee’s stewardship, pointed out that the ‘one China’

issue was something the new administration could not run away from.35

DPP chairman Frank Xie, who, along with the President, has been deemed as one of the most respected politicians in the ruling party, suffered the same fate when he suggested that

unification could be an option.36 In trying to break the Beijing–Taipei stalemate, Xie

proposed sticking to the ROC constitution as a way to counter Beijing’s insistence on the ‘one China’ issue. For this, Xie was censured by members of his own faction, who demanded that

he adhere to the party line when speaking on behalf of the party.37

Realizing that cross-Strait relations were the Achilles’ heel on his way to presidency,

34

They are: the Justice Alliance, Alliance for Laissez-faire Nation, the New Dynamics, and the New Alliance for Taiwan Independence. See Chen Huashen and Yang Junchi, ‘Minjindang paixizhenzhi yu jiazhuzhenzhi’ [‘DPP’s factional politics and family politics’], Kuojia zhenche luntan [Forum for National Policy] (Taipei) 1(3), (May 2001), pp. 47–55.

35 Zhongkuo shibao, (3 September 2000), p. 2. 36

Zhongkuo shibao, (17 August 2000), p. 4.

37

candidate Chen, carefully paraphrasing Anthony Giddens’ ‘the third alternative’38 and crafting the ‘new middle of the road’ (xin zhongjian luxian) policy during the 2000 presidential campaign, promised moderation in making policies towards China.

In his 2001 New Year address, President Chen proposed that the two sides should ‘base their relations on the current economic and cultural integration, build up mutual trust, and

work towards a new framework of political integration which would sustain eternal peace’.39

The proposal was considered far-fetched, given DPP’s lack of consensus in the wake of emerging China in the region of East Asia. But it did not come out of the blue either. In the 1999 Resolution on the Future of Taiwan, the party vowed to build a ‘special relation’ with China. Veteran party leader and former chairman Lin Yixiong once suggested ‘common tariffs’, ‘free trade zone’, and ‘common market’ as possible scenarios that the two sides may

enter.40 Another former party chairman She Mingde also coined the term ‘Great Chinese

Confederacy’.41 These previous proposals no doubt have helped soothe repercussions that

might have been generated out of the bold initiative of ‘political integration’.

However, dissention expressed by members of the radical New Tide faction as well as the militant fundamentalists including Jianguodang (Taiwan Independence Party) and Taiwan

Presbyterian Church have forced Chen to back away.42 For people like Peng Ming-min, Lee

Cheng-yuan, former head of the Jianguodang, and Lee Hong-xi, the President’s teacher at the National Taiwan University Law School, President Chen has already given in too much on the issue of ‘one China’ when he pronounced the ‘five nos’ at inauguration and thus backpedaled the position of Taiwan independence.

There is some concern within the party that as long as the ‘independence clause’ remains in the party charter, there will be misgivings. Over the years, the moderates have been urging revision of the ‘independence clause’ to alleviate pressure from outside and reduce misgivings from potential voters. For them, the reason for not pushing for a total obliteration of the independence position is a strategic one that will enable the party to leverage against Beijing’s incessant demands.

Shen Fuxiong, a member of the President’s Justice Alliance faction and eloquent legislator with island-wide reputation, once proposed revision of the clause. It was not unanimously endorsed and no revision was made at that time but it helped spur a rethinking about the once sacred credo of Taiwan independence within the party.

Rumor was rife that soon after the DPP won the presidential election, Chen Shui-bian urged Chen Zhaonan, a member of the New Century faction, to test balloon the possibility of

38

Anthony Giddens, The Third Way: Renewal of Social Democracy (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 1999).

39 Zhongguo shibao, (2 January 2001), p. 1. 40

Zhongguo shibao, (7 November 1997), p. 4.

41

Taiwan ribao (Taipei), (14 February 1998).

42 Liu Jincai, ‘Minjindang neibu de paixi shengtai yu dalu zhenche zhenyi’ [‘DPP’s factional

environment and disputes over the mainland policies’], Zhongguo pinglun [China Review] (Hong Kong), (May 2001), pp. 47–51.

getting on with the revision.43The proposal was dropped when the radicals expressed opposition and the government chose to remain mum as a result. Nevertheless, Party Chairman Frank Xie and veteran politician Zhang Junhong expressed support. For these politicians, plebiscite for independence should be defensive in nature. As long as Beijing renounces the use of force as a means of resolving differences, there is no need for Taiwan to resort to the use of plebiscite. Hence, to trade independence with no use of force from Beijing is highly recommended by the moderates.

As for the New Tide, the goal of independence has been an untouchable shengzhupai (a sacred tablet). Chen Shui-bian’s promise of ‘five nos’ has already served the function of restraining the ‘independence clause’ and therefore, there is no need for further amendment.

However, on the eve of a crucial election to renew the parliament and local

administrators held at the end of 2001, Taiwan stock price had dropped almost 50% since the DPP became the ruling party, its currency devalued to the lowest rate in 17 years,

unemployment had surged to an all-time high of 5.3%, and the real estate market had plunged precipitously. The economic slump had forced the new administration to take action.

Domestic business tycoons such as Morris Chang, the chairman of the world’s largest chip maker, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, had reversed his decision of not to make investment in the mainland in the near future by announcing that he now sees the

mainland market as ‘irresistible’.44 Well-known multinational corporations with interests in

Taiwan such as Dell computers heightened the anxiety by purporting that unless the problem of direct shipping was resolved, the company was going to relocate its Taiwan headquarters to

either Hong Kong or the mainland.45

Confronted by the unprecedented economic woes, President Chen Shui-bian convened a cabinet-level Economic Development Advisory Conference in August 2001 to find answers. The month-long conference did replace the ‘no haste, be patient’ policy with an ‘active opening and effective management’ policy. Over all, 332 consensuses on taxation and finance reforms, including 36 aimed at developing closer economic ties with the mainland, were passed. Among them, the most significant one is the lifting of the US$50 million cap on single investments in the mainland and the limit on total investments there by listed companies. It also urged the government to actively pursue direct trade, transportation and postal links, the so-called ‘three direct links’, with the mainland.46

It is believed that the President resorted to the unorthodox decision-making mechanism to circumvent possible opposition by the extreme fundamentalists within his own party. The New Tide faction had basically supported the shift of policy. However, speaking on behalf of

43 Zhongkuo shibao, (22 March 2000), p. 1. 44

Gongshang shibao, (5 September 2001), p. 6.

45

Ye Wanan, ‘Santong, songbang jieji yongren cainen genliu taiwan’ [‘Direct transportation and loosening up on the “no haste, be patient” policy are the keys to keep the roots in Taiwan’], Lienho bao, (23 August 2001), p. 14.

46

the fundamentalists, Vice President Annete Lu expressed her unhappiness by criticizing the President in saying that ‘those in charge should have the courage and consciousness to face the history’.47

Future developments

The surge of radicalism in the early 1990s in the DPP had been a cause of concern for Beijing. The moderates had lost out in the power struggle to the radical New Tide faction, which has since demonstrated extraordinary capabilities in maintaining party discipline.

48Ironically, the moderates’ position on the sensitive issue of Taiwan independence has been

adopted by the radicals. This is especially evident after the DPP became the ruling party and the New Tide emerged as the major force to contend with within the party. However, a small group of fundamentalists sticking to the original goal of Taiwan independence has continued to hold sway in the making of the Chen Administration’s policy towards China.

From Beijing’s point of view, the present situation is precarious at best. For Beijing, Chen Shui-bian is devious and untrustworthy. Qian Qichen, China’s vice premier and the second in command in the CCP’s Office of Taiwan Affairs, said in July 2000 that both Taiwan and the mainland are parts of China, instead of the more conventional ‘there is one China in the world and Taiwan is a part of it’. It was the first time that a major policy maker had made such an inclusive definition of China, and can only be interpreted as a reflection of the consternation on Beijing’s part.

Although the DPP has gradually redefined the terms of independence by stressing preservation of the status quo over reconstruction of a new entity, it is highly unlikely that Beijing would find this acceptable. Chen Shui-bian’s inconsistency has furthered Beijing’s misgivings. Chen had formally reaffirmed in his 2001 New Year address the ‘one China’

creed, albeit conditional on the ROC constitution,49 but Beijing has until now not made any

favorable response.

Secondly, Chen’s attitude towards the National Unification Guidelines, a document enacted by former president Lee, is an indication of his stand on the independence issue. In his inaugural address, Chen pledged not to revoke the document. In his 2001 New Year speech, President Chen stressed that he would ‘establish a new mechanism or readjust the old ones [meaning the National Unification Guidelines and the National Unification Council] as soon as possible’.

But so far nothing has happened. Neither the document nor the Council is annulled,

47

Zhongkuo shibao, (14 August 2001), p. 1.

48 The party held primaries in March 2000 to decide nominations for the upcoming Legislative Yuan

elections at the end of 2000 and the New Tide faction emerged the sole winner. The faction has held overwhelming influence over the decisions made both by the party machinery and the administration.

49 The reason for Chen’s statement that ‘there is no problem with “one China” according to ROC

constitution’ is simple: it is in line with the DPP position that Taiwan is an actual sovereignty and thus, the phrase ‘one China’ is shunned.

although they have become less important now.

On top of his pronouncements of ‘one China’ according to ROC constitution and the possibility of resuming the NUC meetings, President Chen had painstakingly coined the term ‘political integration’ in his 2001 New Year address, only to withdraw it later. It thus seems that President Chen has tried to chart an eclectic line to please both Beijing and DPP supporters. What has happened suggests that he has failed on both accounts. Factional restraint has held back Chen’s ability to innovate for a breakthrough in cross-Strait relations.

Beijing’s response to his first anniversary address in May 2001—that he would start negotiations with Beijing on any issues and at any place and that he would like to attend the annual APEC meeting to be held in Shanghai in November 2001, to meet with President Jiang

Zemin—was rather cool.50The ‘new five nos policy’— military procurement from and transit

through the US are not to be taken as provoking China; the ROC government would not miscalculate the situation in the Taiwan area; Taiwan is not a pawn of any country; the Chen Government will not spare any effort in improving relations with Beijing; cross-Strait

relations are not a zero-sum game51—made by Chen on a trip to Central America in May

2001 was met with a large-scale military drill on an island near Taiwan. Whether Beijing would alter the policy of ‘listening to his words and watching his deeds’ is the thing to watch next.

Beijing has made it very clear that unless Taipei reverses its current policy and reverts to the ‘one China’ consensus reached between the two sides in November 1992 that bilateral relations are unlikely to be normalized. Whether the Chen Shui-bian Administration would respond to that call is contingent to a very large degree upon what positions the radicals within the DPP will take. So far there is no sign that the radicals are ready to make any concessions on this issue.

But pressures are mounting. One year after taking over power from the KMT, the DPP has found itself in an extremely unsavory situation: the economic growth rate is already at a record low; the unemployment rate is the highest since the government started tabulation; a new wave of ‘mainland fever’ is haunting the island as large amounts of Taiwan capital flow west to the mainland market (latest statistics say that more than 43% of companies listed on the Taiwan stock market have established footholds on the other side of the Strait) and more and more engineers, managers, and college graduates find China an attractive place to explore opportunities (it is estimated that the number of Taiwan business and staff living on the

mainland is growing rapidly and Shanghai alone accounts for 350,000 Taiwanese);52 domestic

confidence has reached a new low as uncertainties over the future of the island mount; and support for the ‘one country, two systems’ formula, a propaganda gimmick designed by

50

An unidentified official in Beijing responsible for Taiwan policies included Chen’s speech as evidence for the island heading towards factual independence. See Ming Bao, (4 June 2001), p. A12.

51

Lien-ho bao, (28 May 2001), p. 1.

52

Beijing in the early 1980s to allure Taiwan back to the mainland fold,53is at a record high (in three polls conducted in mid-2001 by Taipei media organizations, between 29 and 33% of Taiwan residents said that they could live with the model; previous such figures were all below 20%).

For a party which started out from grassroots with mobilizing masses and winning elections as the only means that they have known of grabbing resources away from the once mighty KMT, these pragmatic pressures might speak aloud to the decision-makers of the DPP, moderate or not.

The DPP may find some consolation in winning the 2001 year-end elections and the emergence of the party as the largest political force in Taiwan. The party grabbed 87 seats as compared to the KMT’s 68 seats in the 225-member parliament, an increase of 20 seats. The voters seemed intent to give the fledgling ruling party another chance. The message that the voters sent to President Chen concerning cross-Strait relations might be unequivocal: there is no need to change. If that is the message, then the mandate that many pundits expected would be presented to the Chen Administration to further adjust its policy towards Beijing by a less than overwhelming victory would have been lost. It is henceforth less likely that the Chen Administration would make any drastic overtures to lure Beijing back to the negotiating table.

53

See Chien-min Chao, “‘One country, two systems”: a theoretical analysis’, Asian Affairs (1987), pp. 107–124.