The Rise of Chinese Literary Theory: Intertextuality and System

Mutations in Classical Texts

Han-liang Chang Professor of Semiotics National Taiwan University

It seems anachronistic to talk about intertextuality in the beginning of the Twenty-First Century, almost forty years since the term first appeared with Julia Kristeva’s introduction of Mikhail Bakhtin to the Western world (1969: 143-73). Popular as the term is, and

controversial as its changing concept has been, very little modern Chinese critical writing deals with the issue of intertextuality (Yip 1988; Fokkema 2000). But comparable textual strategies have governed Chinese critics’ and poets’ reading and writing about literature throughout the dynasties. My analysis probes into the matter by relating two highly influential ancient texts, the Confucian Classic of Changes (hereinafter cited as Changes), dated as early as the fifth century B.C.E. and Liu Xie ’s The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons (cited as Dragons), an ars poetica in the third century of the Common Era. But first, a theoretical and methodological framework is in order.

The use and abuse of the term “intertextuality” over the past three decades have less to do with the word’s novelty than its ambiguity. Like all conceptual words, its root text has undergone a process from concreteness to abstraction. Its Latin etymology and hence metaphor of textile aside, the concept’s changing shape in modern scholarship can be seen from the ways in which the word text is used by traditio nal textual critics, the New Critics, and members of the Tel Quel group. Modern critical history witnessed text’s metamorphosis from a more or less material entity, i.e., manuscripts or printed matter which a textual critic can edit, to a semantic property claiming autonomy and aspiring to the conditions of ontology, a system of coded structures, and finally to some kind of enunciative and discursive

productivity (Kristeva) or semiotic mis-en-abîme (Derrida). The same critical history has also seen the exchange of textuality and intertextuality, as well as the latter’s ultimate triumph over the former.

It is not my intention here to go over the history of this conceptual evolution, to expose and, if possible, to dispel some of the myths involved with intertextuality. Much has already been done in this regard.1 I shall, instead, appropriate two usages. The first usage is suggested by Kristeva as a remedy to the confusion of influence with intertextuality, which she refers to the “transposition of one (or several) sign system(s) into another” (1974: 59-60). The second usage belongs to Michael Riffaterre in his untiring attempts over the past thirty years to reinstate materiality by truncating the abstract intertextuality to a more reified intertext (1990: 56).2 Whether or not intertexts can be identified through specific signposts, as Riffaterre suggests, is not an issue here. My attempt is to articulate the transposition of sign systems as manifested in the two classical Chinese texts, the Confucian philosophical writing Changes and Liu Xie’s Dragons, the latter generally regarded as the first systematic book of literary theory and criticism.

1. Text and Architext

Let me begin by briefly defining, indeed rehearsing, text. Text is the product of signification, i.e., the positioning and functioning of signs with “coded structures” as tacitly agreed upon, or used without awareness, by members of a discursive community. These signs and their components are variously distributed and integrated into a hierarchy of relations. It is possible that a text is made up by different kinds of encoded signs, such as verbal and nonverbal signs. In such cases, these codes necessarily enter into complex intratextual relationships. Now when the same or a similar structural relationship is applied to two or several or, theoretically, an infinite number of texts, one is dealing with the

phenomenon of intertextuality. The transcoding relationship exists on both the expression and the content levels, or syntactic and semantic levels. I shall demonstrate by analyzing

the heterogeneous text of Changes and its relation to Dragons.

My basic assumption cannot be more simplistic: the nonverbal sign system of trigram and hexagram in Changes has served as an architext (Genette 1979, 1982), intertext

(Riffattere), or interpretant (Peirce), which, by virtue of its nonverbal, but highly abstract and flexible, nature, is capable of receiving repeated semantic investments, such as Liu Xie’s interpretations of the origin of literacy/ literature, form and genre, and evolution. This transposition of sign systems began with the earliest exegetes, has continued throughout the millennia, and is still being practiced today in popular culture. Once verbalized, various new semiotic systems were transcoded into other systems because of language’s double articulation and literature’s secondary modeling system, including generic and formal

constraints. This second stage of semiotic transposition can be best demonstrated by Sikong Tu’s Twenty-Four Orders of Poetry of the Eleventh Century.

The Book of Changes or The Classic of Changes, as in Lynn’s recent translation, is the title, not of one book, but of a historical corpus of commentaries, dating, according to some scholars, as early as King Wen or Chancellor Zhou of the Zhou dynasty in the Twelfth

Century B.C.E. One tradition attributes its authorship/ editorship to Confucius. However, it is unlikely that Confucius, or for that matter any other individual, could have authored such a heterogeneous text; nor could he have been its first commentator. Confucius’ link with the text remains controversial though there is ample evidence to support his editorship.

1. There are many quotations from him in the Commentary on Appended Phrases, presumably by his followers.

2. In The Analects compiled by his disciples, the Master is reported to have remarked that with a few more years to live, he would be able to learn the Changes at the age of fifty.3 This is an often-quoted but puzzling remark because his frequent references to the Changes show that he knows the text well. But as far as I can tell, nobody has annotated this strange exclamation in terms of

the magic number 50 in the Changes.

3. The Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi records that Confucius edited the six classics, including the Changes.

This last interpretation is endorsed by Liu Xie, as he observes in the chapter entitled Zongjing [“The Classics as Literary Sources”]: “But after our Master edited and handed down this material, those great treasures, the Classics, began to shine through. The Book of Changes spread out its ten Wings, or Commentaries. . . .”

Another source of controversy is the dating of the five or six classics among Han

scholars. One version takes The Classic of Poetry to be on top of the classics; another takes the Changes to be the oldest. I do not deal with such matters here, but I would differentiate the Changes from the other Confucian canons for a distinctive feature, namely, it is the only canon that is variously encoded. In terms of the graphic or scriptorial code in which messages are framed, the Changes consists of two distinct systems: First, the nonverbal trigrams and their reduplications with variation, which are called the hexagrams; second, the verbal commentaries which can be further categorized according to kinds and degrees of semanticization. If one follows the classical distinction made by Hjelmslev (1959), one can arrive at a simplified reading that the first graphemic system, if it is writing at all, serves as the expression which is cenemic or meaningless, and the second semantic system the content, being pleremic or meaningful. The transposition of cenemic system into pleremic system through verbalization is, according to Laurent Jenny, a typical intertextual processing (Jenny 1982: 51). And it is this intertextual processing that has given rise to thousands of volumes that constitute the Changes scholarship.

2. Trigrams and Hexagrams

The binarism of expression and content, or if one prefers, signifier and signified, manifests itself in the minimal units as well as on higher levels. For instance, each trigram or hexagram, known in Chinese as gua, has a name, a corresponding verbal caption, called ci

or phrase. The gua itself can be further segmentalized into lower units because it is

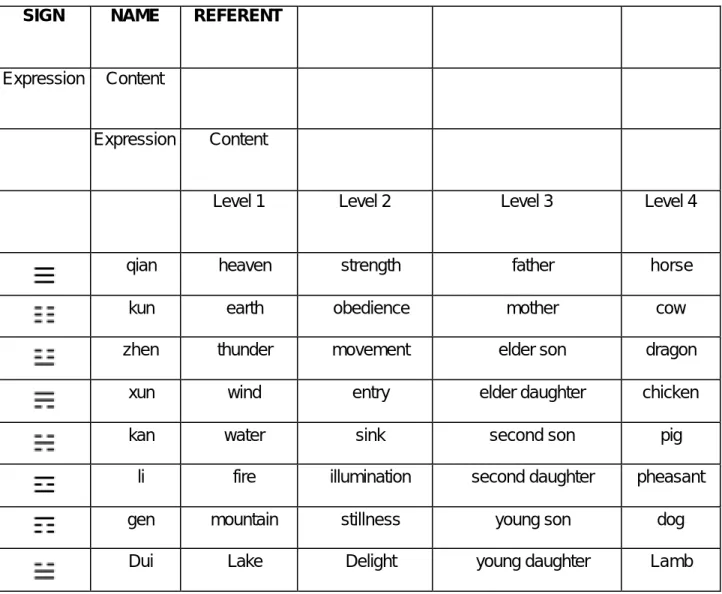

composed by parallel solid or broken lines called yao, which also have corresponding phrases. It takes three yaos to form a trigram, such as three parallel solid lines form the trigram called qian, and three broken lines kun. Altogether there are eight trigrams, and with two trigrams superimposed, where one is called the upper gua, the other the lower gua, a hexagram is produced, and after combinations and permutations, sixty- four hexagrams are produced. Table 1 illustrates correspondences among the sets of nominalization for the eight basic trigrams. The list is based on one of the Ten Commentaries, which is entitled Shugua [Explaining the Trigrams].

Table 1 Basic Trigrams

SIGN NAME REFERENT

Expression Content

Expression Content

Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4

qian heaven strength father horse

kun earth obedience mother cow

zhen thunder movement elder son dragon xun wind entry elder daughter chicken

kan water sink second son pig

li fire illumination second daughter pheasant gen mountain stillness young son dog Dui Lake Delight young daughter Lamb

The list can be endless. Here the simple and random taxonomy is far from being logical and typological, though one may submit the list to an analysis of the metaphorical and

metonymical relationships into which the semantic elements may enter. For instance, one could establish that (1) very loosely, all the units on one level, such as Level 1, belong to the large “semantic” area of nature, e.g., that heaven, earth, thunder, etc. all signify primordial natural elements, and that (2) all the units governed by one trigrammatic sign, such as ≡ [qian], enter into paradigmatic relationships, so that heaven, strength, father, horse . . . are substitutive. Two problems arise: first, the suggested relationships are neither linguistic nor logical; second, it is never clear how vertical transformations from the deep level of trigrams to the surface levels of referents, i.e., from system 1 (expression) to system 2 (content), are possible in the first place (Greimas and Courtés 1979 et 1986: 348-50). One could conclude, perhaps, that system 1 is so abstract, but handy, that any reading into it is acceptable. The modern Neo-Confucianist philosopher Mou Zongsan (1974: 88-89) observes,

The ‘book’ of Changes exhausts the mysterious and commands the mutable. It originated in oracle decipherment and divination on the basis of hexagrammatic signs. Its unique structure lies in its non-written sign system, which can accommodate different approaches.

The rules of combination and permutation of the nonverbal system 1 are rather fixed and limited and have been in general identified. There are basically transformational rules of negation and reversal between neighboring guas. Thus gua 1 gives rise to gua 2, to gua 3 . . . and after reduplication, to gua 64. These nonverbal signs, their names, and captions or phrases, constitute jing [the constant text] of Changes. And the ten commentaries attributed to Confucius or his followers are called zhuan [commentaries], including the xici [“Appended Phrases”].

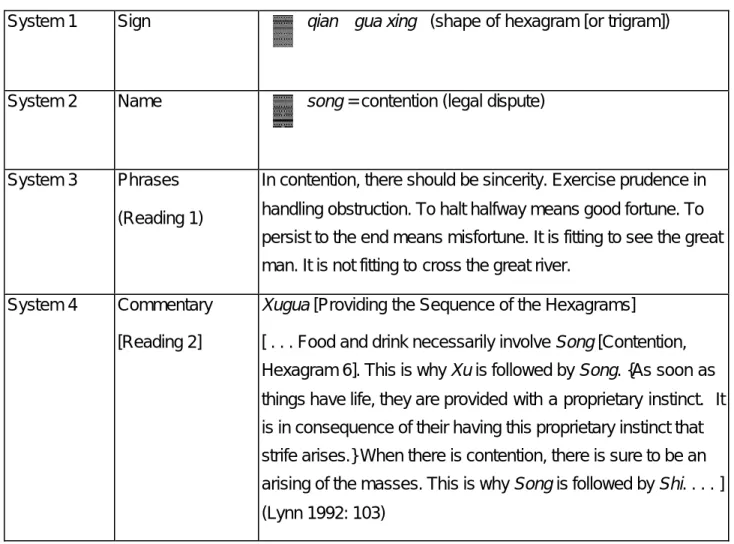

Thus, what we call The Classic of Changes is a composite text of three distinct, but superimposed, levels: (1) System 1: the nonverbal, graphic sign system, (2) System 2: a

verbalized nominal system encoded to map System 1, and (3) System 3: a secondary verbal mapping, setting to decode Systems 1 and 2, but actually encoding them. Table 2 shows the inter-systemic relationship of the hexagram song [contention or legal dispute].

Table 2 The Hexagram Song

System 1 Sign qian gua xing (shape of hexagram [or trigram])

System 2 Name song = contention (legal dispute)

System 3 Phrases (Reading 1)

In contention, there should be sincerity. Exercise prudence in handling obstruction. To halt halfway means good fortune. To persist to the end means misfortune. It is fitting to see the great man. It is not fitting to cross the great river.

System 4 Commentary [Reading 2]

Xugua [Providing the Sequence of the Hexagrams]

[ . . . Food and drink necessarily involve Song [Contention, Hexagram 6]. This is why Xu is followed by Song. {As soon as things have life, they are provided with a proprietary instinct. It is in consequence of their having this proprietary instinct that strife arises.} When there is contention, there is sure to be an arising of the masses. This is why Song is followed by Shi. . . . ] (Lynn 1992: 103)

On the lowest level, i.e., System 1, transformations are based on the simple opposition between solid and broken lines, the only other formal constraint being three lines of the original trigram [bengua] and the six lines of its derived hexagram [biegua]. Suppose one takes the trigram as the signifier, its corresponding name on the higher level of System 2 the signified, then one finds their relationship extremely arbitrary. So far it is still not clear how System 1 gives rise to System 2. Since System 2 is verbalized, interpretations based on

random semantic investment follow naturally and quite easily.4

Legend has it, and Liu Xie believes it, that System 1 was invented by the mythical Fu Xi [Pao Hsi in Shih’s translation], who devised a divination and communication system which, lacking a better term, can only be called either iconic numerical sign, or “semasiography,” i.e., non-phonetic pre-writing (Gelb 1963; Sampson 1985: 39).5

Human pattern originated in the Supreme, the Ultimate. ‘Mysteriously assisting the gods’, the image of the Changes are the earliest expressions of this pattern. Pao-hsi began [the Book of Changes] by drawing [the eight trigrams], and Confucius completed it by writing the ‘Wings’ (Liu i.465-522: 15).

To this sign system of sixty- four hexagrams, interpreters have appended their metatexts, i.e., commentaries for various social and political uses. The process of verbalization may have coincided with the development and sophistication of writing, witnessing, metonymically, the metamorphosis of a semi-divine homo signans to homo loquens.

3. Two Traditions

Starting from the Han dynasty in the Second Century B.C.E., the Yi [I Ching] or

Changes scholarship developed along two traditions. The first tradition, which developed in the Han dynasty and was labeled Shushu xi [the School of Method and Number] and/or Xiangshu xi [the School of Sign and Number], is primarily concerned with the operations of System 1 for the function of divination, therefore it refrains from philosophizing and makes little use of the commentaries. Even in the “Appended Phrases”, we are able to see such a function.

When the eight trigrams formed ranks, the [basic] images were present there within them . . . And so, when they doubled these, the lines were present there within them . . . When they let the hard and the soft displace each other, change was present there within them. Good fortune, misfortune, regret, and remorse are all generated from the way the lines move. . . . (Lynn: 1992, 74-75).

The second tradition, fully developed before Liu Xie’s time, is interested in the philosophy of the Changes and hence pays more attention to the commentaries (Mou 1974: 89-99). It is called Yili xi [the Meaning and Reason School].

Liu’s reading of Changes, to be sure, is not his own invention, but mediated by the metatexts of others, in particular, Wang Bi and Wang’s disciple Han Kangbo. Liu praises Wang’s interpretation as “precise and illuminating” and asserts that it can serve as a “paragon”. (Liu i.465-522: 205) These metatexts, unlike the exegeses of Han scholars, which excelled in philology, are characterized by their interest in metaphysical issues. Together with the Daoist canons of Laozi and Zhuangzi, the Changes was regarded as one of the three “Mysteries” [san xuan]. Liu Xie finds in the Changes philosophical foundations of literary concepts, particularly the concept of ontology based on dao, and the concept of

evolution, based on yi [change].

Before moving to Liu Xie, I shall give another example to show the transposition of sign systems which involves the nonverbal yao and gua, the verbal phrases attached to yao and gua, and the commentary of Confucius, which is further commented by Liu’s predecessors Wang Bi and Han Kangbo. The example, I think, will shed light on how Liu Xie is to rewrite on the palimpsest of Changes and indeed on the body of Confucius through the secondary model of allegorization.

Chapter Eight of Part One of the Commentary on the Appended Phrases records Confucius’ reading of several hexagrammatic signs. One instance begins with a verse,

A calling crane is in the shadows; Its young answer it.

I have a fine goblet;

I will share it with you (Lynn: 1992, 57).

Anyone familiar with the poetic devices of The Classic of Poetry will be stricken by a sense of déjà vu. The first-person lyricism is occasioned by a natural phenomenon. But such a

poetic reading would be mistaken; it has to be recontextualized as a verbal decipherment of the hexagram Zhongfu [Inner Sincerity] whose sign is . Now the above verse is a verbal equivalence to the second solid line from the bottom called “nine second” which is a yang or male yao. This solid line is “suppressed”, so to speak, by two broken lines on top,

respectively called “six third” and “six fourth”, which are yin or female yaos, but it is repeated by the fifth solid line from the bottom, which is again a yang or male yao. The relationships among these solid and broken lines have received first-order semantic

investment and second-order poetic investment, both drawing on the repertoire of discursive practices of the time. Thus, a first-person voice is assumed, strangely to us but not to the ear of Changes’ practitioners, by the personified solid “nine second” line, who compares his misfo rtune to a calling crane in the shadows of those two broken lines “six third” and “six fourth”, and his addressee to whom he invites to a drink is the unbroken line “nine fifth”. The temporal and causal relationships between “nine second” yao, a component of the hexagram and a corresponding poem are intricate and intriguing. One could say the (architext of) hexagram gives rise to the poem, hence the latter as a metatext; but one could equally say that the poetic conventions of the time serve as an interpretant for the

commentator to decode the cryptic hexagram. Whatever the truth, one thing seems plausible, the canons of Changes and Poetry are mutually intertextual.

4. Rhetoric and Criticism

Our story is still unfinished. It is further complicated by Confucius who goes so far as to moralize the situation of the yao and, hence, the bird in the following comment.

The noble man might stay in his chambers, but if the words he speaks are about goodness, even those from more than a thousand li away will respond with approval to him, and how much the more will those who are nearby do so! If he stays in his chambers and his words are not about goodness, then those from more than a thousand li away will go against him, and how much the more will those

who are nearby do so! Words go forth from one’s person and are bestowed on the people. Actions start in what is near and are seen far away. Words and actions are the door hinge and crossbow trigger of the noble man. It is the opening of this door or release of this trigger that controls the difference between honor or disgrace. Words and actions are the means by which the noble man moves Heaven and Earth. So how could one ever fail to pay careful heed to them (Lynn: 1992, 58)!

Confucius’ comment is clearly different from the phrases [ci] of sign [xiang]. In that system of verbalization, only one level higher up than ming, the semantics is restricted to four words: ji, xiong, hui, lin [good fortune, misfortune, regret, and remorse] and whose

application is purely divinatory. But the Master’s commentary has extended its application and projected moralism and ethics onto the previous simple message. This certainly requires exercises of persuasion and use of rhetoric. The best example is provided by the Commentary to Appended Phrases, shortly (i.e., one hundred years) completed by Han Kangbo before Liu Xie’s time. I think this is a turning point in the Changes scholarship. From here, the next step is literary criticism.

The superimposition of language on nonverbal hexagrams practiced by Confucius and Han exegetes is characteristic of the Changes scholarship and unique in the commentary tradition of the classics. It is the very textual strategy adopted by Liu Xie. Liu opens his magnum opus by an autobiographical preface in which he identifies his lineage with

Confucius the master commentator in a dream vision.

As a child of seven I dreamed of coloured clouds like brocaded silk and that I climbed up and picked them. When over thirty years of age, I dreamed I had in my hand the painted and lacquered ceremonial vessels and was following

Confucius and travelling towards the south. In the morning I awoke happy and deeply at ease. The difficulty of seeing the Sage is great indeed, and yet he appeared in the dream of an insignificant fellow like me! Since the birth of man

there has never been anyone like the Master. Now, insofar as I wished to

propagate and praise the teachings of the Sage, nothing would have been better than to write commentaries on the Classics. (Liu i.465-522: 5)

The Changes serves as an architext for Liu Xie to conceptualize, structure and articulate his ideas about literature. Because of its non-specific nature, this architext cannot be restricted to what Gérard Genette (1979) would describe as a ge nre concept, but it provides an anterior “discursive space” (Culler 1981: 103), a textual repertoire of which Liu makes free use on both the expression and content levels, it also supplies Liu with strategies for his

interpretations of origin, periodization, evolution, genre and style. One could say that the Dragons presupposes the Changes, and the Changes ensures the Dragons’ intelligibility. Perhaps we could mention, in passing, that the animal of changes that governs the semiotic universe of Changes is none other than the totemic dragon, and that this metaphysical animal has metamorphosed into a symbol of art in Liu’s text. According to the philological

research, and therefore from a different persuasion, among the fifty chapters of the Dragons, only two chapters do not make explicit references to the Changes (Wang 1975).

Liu’s use of the Changes is so widespread that almost all the literary issues he discusses can be traced to the metaphysical foundation of it. These include four areas of investigatio n; conceptualized and expressed in modern parlance, they are: (1) ontological, (2)

epistemological and cognitive, (3) evaluative, and (4) formalistic; and they embrace both literary semantics and pragmatics. And all these aspects involve the two texts, which criss-cross each other. Since Liu’s articulation of such problems is always informed and mediated by the Changes, it makes his own text a rewriting, a metatext of the architext that is the Changes; or better still, the Changes and the Dragons are intertextual.

Liu’s concept of the origin of literature, and for that matter, literacy in the truest sense of the word, is “logocentric”. As told in the Yuandao, it originated in Taiji [the Great Primal Beginning], from which are derived the two opposing fo rces yin and yang, represented

respectively by the solid and broken lines. These two forces are taken over and mediated by a Peircian thirdness, represented by a third line, whether solid or broken, symbolising

humanity. The interaction of such primal na tural and human relationships, then, is expressed abstractly by the gua. Part two of Commentary on the Appended Phrases thus opens with the description:

When the eight trigrams formed ranks, the [basic] images were present there within them. And so, when they [the sages] doubled these, the lines were present there within them. When they let the hard and the soft [i.e., the strong and the weak, the yang and yin trigrams] displace each other, change was present there within them. When they attached phrases to the lines and made them injunctions, the ways the lines move were present there within them. Good fortune, misfortune, regret, and remorse are all generated from the way the lines move (Lynn 1992: 75-76).

The whole system is, to be sure, a human cons truct, which is succinctly expressed in one phrase from Part One of the Commentary. The description of the origin of sign production in the Changes reads, in Lynn’s translation, “The sages set down the hexagrams and observed the images” (1992: 49).

5. Encyclopedic Semiotics

Let me pause here for a digression into possible semiotic recodings. I shall suggest the following renditions, which aim to show different degrees of recoding.

1. The sages have set up gua to observe xiang, appended to the former ci, to tell xiong or ji.

2. The sages have set up a sign system to observe phenomena, and have appended to the system language to tell ill and/or good omens.

3. The sages have set up the hexagrams and displayed all the combinations and permutations; and appended to them a system of interpretative language, i.e., written interpretations, to show ill or auspicious omens.

4. The sages have set up the sign (representamen + object + interpretant, or signifier + signified), conceptualized what it signifies, and attempted to explain it with the linguistic sign.

5. The sages have set up semiotic System 1 to observe another semiotic System 2, and appended to semiotic System 1 to interpret yet another semiotic System 3. Numbers 4 and 5 would be examples of what I have termed elsewhere semiotic recoding or remodeling of a commonplace in the Changes scholarship (Chang 1998). But the

consequences of it can be different because of the questions raised are different. For example, one could ask: “Is Xiang [image, sign, and above all literally, elephant] exterior to the sign or interior to it, system-specific or inter-systemic?” According to both Charles Sanders Peirce and Ferdinand de Saussure, the signified concept [of the signifier] and the object for which the representamen stands constitutes the sign, is part of it, rather than having a life outside the sign.

The semiotic implications of the above quotation from the Changes, of which Liu Xie is to make great use, cannot be over-emphasized. First, both the nonverbal and verbal systems are system-specific. Second, transpositions of system are possible, but they have to take into account this system-specificity. Third, because of language’s being in itself both an interpreted and interpreting system, all kinds of interpretation are generated and all kinds of interpretative use are accommodated by System 1 (Benveniste 1974). Last but certainly not least, in the case of the Dragons, Liu Xie has detected in the Sage’s act of sign production an abstraction which lays the foundation of his critical theory and serves as the substance for the organizing principle of change or influx. This he calls wen, which refers to “pattern”, or “letter”, either nonverbal or verbal. As he puts it in our excerpt from chapter two entitled Yuandao [On Tao, the Source]:

Human pattern originated in the Supreme, the Ultimate. ‘Mysteriously assisting the gods’, the images of the Changes are the earliest expressions of this pattern. Pao-

hsi began [the Book of Changes] by drawing [the eight trigrams], and Confucius completed it by writing the ‘Wings’. [One of the Wings], the ‘Wen- yen’ or ‘Words with Pattern,’ was written especially to explain the ‘Ch’ien’ [qian] and the ‘K’un’ [kun]. Words with pattern indeed express the mind of the universe (Liu i.465-522:15)!

Now, the human pattern covers both the nonverbal graphic sign system, what I earlier described as iconic numerical signs or semasiography, and the later transposed writing

system, adequately defined by wen’s double denotation. Witness Liu Xie’s description of, in Kristeva’s (1974) words, the “thetic phase” which establishes human signification, i.e., the miraculous moment when the human subject uses language to construct the world and herself.

Now with the emergence of mind, language is created, and when language is created, writing appears. This is natural. When we extend our observations, we find that all things, both animals and plants, have patterns of their own. Dragons and phoenixes portend wondrous events through the picturesqueness of their appearance, and tigers and leopards recall the individuality of virtuous men in their striped and spotted variegation. The sculptured colors of clouds surpass paintings in their beauty, and the blossoms of plants depend on no embroiderers for their marvellous grace. Can these features be due to external adornment? No, they are all natural. Furthermore, the sounds of the forest wind blend to produce melody comparable to that of a reed pipe or lute, and the music created when a spring strikes upon a rock is as melodious as the ringing tone of a jade instrument or bell. Therefore, just as when nature expresses itself in physical bodies there is plastic pattern, so also, when it expresses itself in sound, there is musical pattern. (Liu i.465-522: 13-15)

encyclopedic semiotics (Eco 1983). He produces a verbal semiotic object, a text, if you like, which uses language to encode natural phenomena-in his word, wen or “patterns”. Patterns are signs running the gamut from a simple trigram to sophisticated literary designs. They constitute the unmistakable signpost of literacy/ literature, and govern all the historical genres and forms which Liu Xie deals with in the subsequent chapters. In fact, in the Changes, wen is defined as the locus where patterns or texts clash.

Liu Xie actually deals with them in the manner the diviner practices his magical art, both in the author’s symbolic division of his text into fifty chapters, following the order of

divination, and a unique strategy of conceptual and rhetorical flux. Let me give one example to show his interest in the originary pattern of Changes. In an early chapter entitled Zhengsheng [Evidence from the Sage], Liu tries to appropriate the method of divination for discursive and stylistic registers (Huang and Zhang 1986: 369). The cryptic text reads:

Writing chiefly characterized by critical judgment he [the Sage] symbolizes by the hexagram kuai, and writing chiefly characterized by logical clarity he models after the hexagram li. (Liu i.465-522: 25)

To illustrate and to justify his stylistic description, Liu later quotes the Changes as saying, ‘When things have been correctly distinguished and the language expressing them has been made accurate, then decisive judgments are complete.’ (Liu i.465-522: 27) Here the Sage’s style is noted for a resolute critical language derived from the Jing, indeed from sign reading.

In the same way as the Sage was inspired by the divinatory signs for his linguistic performance, Liu is also aware of the Changes as a rich intertextual repertoire. In a chapter devoted specifically to the use of literary topoi and allusions, he refers to the hexagram of

Daxu, literally meaning the “great storage” [Lynn’s translation is “The Great Domestication”]. He says,

The Hsiang commentary to hexagram Ta-ch’u says: ‘The superior man acquaints himself with many sayings of antiquity and many deeds of the past’, so it is possible that these might also be encompassed within the scope of literary writing. (Liu i.465-522: 395)

This is a direct quotation from the exegesis of the hexagram’s sign [xiang], where the trigram gen is on top of qian. The sign represents the phenomenon when heavens are embraced by mountains, and is construed as symbolic of the sage’s rich store of virtue in his mind (Wang Bi et. al, i.226-249: 81). If one examines closely the first- level of semanticization in the Jing, i.e., in the phrases attached to yao, gua, and xiang, one would find almost nothing but divinatory codification. The readings may appear simplistic, at times contradictory, at times arbitrary; but, the system is there.

Broad and comprehensive as it is, pattern is at most a vague concept for sign. Once departed from nature, it acquires verbal configurations, as the poet would say, the sound of shape and the shape of sound. It would be useful to examine Liu’s conceptualization of wen as both the primary modeling system and the secondary modeling system. The primary model deals with the reciprocal relationship between wen as natural sign and wen as human pattern (of language), and the secondary all the subcodes that constitute specific genres and styles. In fact, Liu’s empirical studies of genres before his times in the first part of Dragons, such as “An Exegesis of Poetry”, “An analysis of Sao”, “Elucidation of Fu”, etc. can be all regarded as illustrations of wen’s secondary modeling functions. The relationships among (1) natural wen, (2) wen as the totality of aspects of primary model of language, whether phonological, syntactic, or semantic, and (3) wen as generic and stylistic features in the secondary model can be presented by a double- layered expression/content structure:

Content natural sign (wen) generic sign (wen 2)

Expression human sign (wen 1) = linguistic sign (wen 1)

Here the fact that human language serves as the expression capable of, in different contexts, representing both natural phenomena and generic and stylistic codes is a curious, but logical, and more refined response to the history of semanticization which characterizes the Changes scholarship. It is the same expression- function of wen which witnesses its mediation of two kinds of content: nature and genre.

6. Conclusion

In an earlier article (Chang 1998), I ventured into the tension between logic and rhetoric in Pre-Qin classics, which may lay the discursive foundation of “semiotics” or at any rate lead to our systematic investigations into the nature and functions of signs. Whether verbal or nonverbal, the signs we have dealt with are always already intertextualized. This

intertextualized feature, as evidenced in the Changes, is true to the sign as a representation; as a manifest indication from which inferences about something latent can be made; or as a verbal or nonverbal gesture produced with the intention of communication. The nonverbal sign system of xiang follows its own simple “logic” of binarism, and that simple system is immediately “contaminated”, so to speak, by the superimposition of the rhetoric of ci. The transformation of sign systems from nonverbal to verbal (in the case of the Changes), from literate to literary or “creative” to “theoretical” (in the case of the Dragons), if without metalingual recoding, may not be reduced to the reciprocal relation between object- language and meta- language. Here, the Hjelmslevian configuration of expression/content will help to account for the reciprocity of object-semiotic and meta-semiotic of the two texts under consideration (Hjelmslev 1943).

Notes

1. To date, there have been dozens of tomes as well as special issues on the topic in critical journals, such as Poétique: revue de théorie et d’analyse littéraire 20 (1976), Diacritics 11.4 (1981), Texte: Revue de critique et de théorie littéraire 2 (1983), The American Journal of SEMIOTICS (1985). See, for instance, the surveys of Morgan (1985) and, more recently, Bernardelli (1997). Yip (1988) is one of the few articles dealing with the concept in classical China. For a brief comparison of the two traditions, see Fokkema (2000). This paper was originally presented at the International Conference on Esthétique du divers at Beijing University, PR China, 7-10 April 2001.

2. Note Riffaterre’s recent redefinition of intertext as an abstract structural relationship: “the web of relationships between the text and other texts which together form the intertext” (1997: 23).

3. Why at the age of fifty? Fifty seems to be a magic number in connection with the Changes. According to the “Appended Phrases”, “The number of the great expansion [exercise, inference] is fifty [yarrow stalks]. Of these we use forty- nine”(Lynn 1992: 60). Liu Xie says, “The postulation of principles and definitions of terms are shown in the number of the Great Change; but only forty- nine chapters are employed for the elucidation of literature”. (Liu i.465-522: 7)

4. The simplistic binarism of System 1 and the apparent lack of logicality in vertical

transformations from System 1 to System 2 and thus System 3 actually inform Liu Xie’s structuration of the forty-nine chapters and the mutability of concepts therein. Sikong Tu’s twenty- four orders should be read in this light. See for instance, the 24th order is liudong [moving] to be annotated by the Changes “Always moving, permeating the universe, mutation of Heaven and Earth, vanishing like this”.

5. It is appropriate to call the system of trigrams and hexagrams pre-writing. The locus under discussion deals with the origin of writing, and immediately after his allusion to

Pao Hi’s invention of these patterns, Liu Xie refers to other forerunners of writing, including quipu “knotted cords” and “birds’ markings” (Liu i.465-522: 17).

References

BENVENISTE, Émile.

1974. “Sémiologie de la langue”, in Problèmes de linguistique générale II (Paris: Gallimard, 1974), 43-66, trans. as “The Semiology of Language” by Genette Ashby and Adelaide Russo, Semiotica Special Supplement (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1981), 5-23. Page references in the present article are to the English translation.

BERNARDELLI, Andrea.

1997. “The Concept of Intertextuality Thirty Years On: 1967-1997”, VERSUS: quaderni di studi semiotici 77/78 (May-December, Milan: Bompiani), 3-22.

CHANG, Han-liang.

1988. “Controversy over Language: Towards Pre-Qin Semiotics”, Tamkang Review 28.3, 1-29.

CULLER, Jonathan.

1981. “Presupposition and Intertextuality”, in The Pursuit of Signs: Semiotics, Literature, Deconstruction (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), 100-18. ECO, Umberto.

1983. “Proposals for a History of Semiotics”, in Semiotics Unfolding, ed. Tasso Barbé (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), vol. 1 of 3, 75-89.

FOKKEMA, Douwe.

2000. “Rewriting: Forms of Rewriting in the Chinese and European Traditions”, Comparative Literature: East & West 1, 3-14.

GELB, Ignace J.

1963. A Study of Writing (2nd ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press). GENETTE, Gérard.

by Jane L. Lewin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992). Page references in the present article are to the English edition.

1982. Palimpsestes: La littérature au second dégrè (Paris: Seuil), trans. as Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997). Page references in the present article are to the English edition.

GREIMAS, Algirdas Julien, and Joseph COURTÉS.

1979 et 1986. Sémiotique - Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage I & II (Paris: Hachette), trans. as Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary by Larry Crist, et. al (Bloomington: Indian University Press, 1982). Page references in the present article are to the English edition.

HJELMSLEV, Louis.

1943. Omkring sprogteoriens grundlæggelse (Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, republished in 1966 by Akademisk Forlag) trans. as Prolegomena to a Theory of Language by Francis J. Whitfield (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1969). Page references in the present article are to the English edition.

1959. Essais linguistiques [=Travaux du Cercle linguistique Copenhague 12] (Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag).

HUANG, Shouqi, and Shanwen ZHANG.

1986. “Shilun zhouyi dui wenxin diaolong di yingxiang” [“On the influence of The Book of Changes on The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons”], Wenxin diaolong xuekan [Journal of Wenxin diaolong Studies] 4, 367-93.

JENNY, Laurent.

1982. “The Strategy of Form”, in French Literary Theory Today: A Reader, ed. Tzvetan Todorov (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 34-63.

1969. Σηµειωτικη: Recherches pour une sémanalyse. Collections “Tel Quel” (Paris: Seuil).

1974. La Révolution du langage poétique: l'avant-garde à la fin du XIXe siècle,

Lautréamont et Mallarmé (Paris: Seuil), trans. as Revolution of Poetic Language by Margrat Waller (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984). Page

references in the present article are to the English edition.

1980. Desire in Language: a semiotic approach to literature and art, ed. Leon S. Roudiez, trans. Thomas Gora, Alice Jardine, and Leon S. Roudiez (New York:

Columbia University Press). LIU, Xie.

i.465-522. Wenxin diaolong (Chinese text). The English trans. by Vincent

Yu-chung Shih, The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1983), was alone and used in this paper.

LYNN, Richard John.

1992. The Classic of Changes: A New Translation of the I Ching as Interpreted by Wang Bi [Translations from the Asian Classics] (New York: Columbia University Press). All the English quotations in the text are from this translation.

MORGAN, Thais E.

1985. “Is There an Intertext in This Text?: Literary and Interdisciplinary Approaches to Intertextuality”, American Journal of SEMIOTICS 3.4, 1-40.

MOU, Zongsan.

1974. Caixing yu xuanli [Character and Metaphysics] (Taipei: Xuesheng shuju). 1999. Zhouyi di ziran zhexue yu daode hanyi [Natural Philosophy and Moral

Implications in the Book of Changes] (Taipei: Wenjin chubanshe). RIFFATERRE, Michael.

1978. Semiotics of Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press).

1979. La Production du texte (Paris: Seuil), trans. as Text Production by Terese Lyons (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986). Page references in the present

article are to the English edition.

1985. “The Interpretant in Literary Semiotics”, American Journal of SEMIOTICS 3.4, 41-55.

1990. “Compulsory Reader Response: The Intertextual Drive”, in Intertextuality: Theories and Practices, ed. Michael Worton and Judith Still (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 56-78.

1997. “Intertextuality’s Sign Systems”, VERSUS: quaderni di studi semiotici 77/78 (May-December, Milan: Bompiani), 23-34.

SAMPSON, Geoffery.

1985. Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

WANG, Bi, HAN Kangbo, and ZHU Xi.

i.226-249, i.332-380, and i.1130-1200. Wang, Han, and Zhu, Confucian scholars of different periods, reinterpret I Ching respectively with abundant

notes. The renderings by former two are often conflated as the known I Ching Wang Han Zhu [an annotated edition of I Ching by Wang and Han], and Zhu’s version is titled Zhouyi Benyi [the original meaning of I Ching]. I Ching Wang Han Zhu and Zhouyi Benyi are incorporated and republished as Zhouyi erzhong [Wang and Han’s Annotations and Zhu Xi’s Zhouyi Benyi in One Volume] by the

publisher, Daan Chupanshe, in 1999 in Taipei. Assessments of Lynn’s translation in 1992 are based on this Chinese edition.

WANG, Renjun.

and the Carving of Dragons] in Wenxin diaolong yanjiou lunwenji [Collected Essays on The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons], ed. Huang Jin- hung, et. al (Taipei: Jingsheng), 85-144.

YIP, Wai- lim.

1988. “Mixiang pangtong: wenyi di paisheng yu jiaohu yinfa” [Secret Echoes and Lateral Grasping], in Lishi chuanshi yu meixue [History, Hermeneutics and Aesthetics] (Taipei: Dongda), 89-113.

Biography

HAN-LIANG CHANG (b. 30 April 1943). Academic Status: Hu Shih Chair Professor of Semiotics and Comparative Literature, Dept. of Foreign Languages & Literatures, National Taiwan University. Mail Address: Dept. of Foreign Languages & Literatures, National Taiwan University, 1 Roosevelt Rd., Sec. 4, Taiwan 106. E-mail:<changhl @ntu.edu.tw>

Internet Page: <http://www.lttc.ntu.edu.tw/academics/changhl.htm> Personal Office Tel: (886) 2362-0866; Dept. Office Tel: (886) 2363-9395; Fax: (886) 2364-5452. Educational Background: Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, National Taiwan University, 1978.

Dissertation Title: “The Structural Study of Narrative”. Postdoctoral Fellow, English Dept., Johns Hopkins University, 1978-79; Fulbright Visiting Associate Professor, Marquette

University, USA, 1985-86; Honorary Research Fellow in Linguistics, Manchester University, UK, 1990-91; Visiting Chair Professor in Chinese Semiotics, Charles University, Czech, 1996; Honorary Research Fellow in English, Manchester University, UK, 1997; Visiting Professor and Fellow in Philosophy, University of Athens, Greece, 1999. Research Interests: (1) Semiotics; (2) Literary Theory; (3) Writing Systems. Professional Background: Founding Member, Literary Theory Committee, International Comparative Literature Association (1985- 1993); President, Comparative Literature Association of Taiwan (ROC) (1988-1990); Honorary Member, The Prague Linguistic Circle (1996-); Member, International Association for the Study of Controversies (1999-).

Bibliography

HAN-LIANG CHANG

2003. “Notes towards a Semiotics of Parasitism”, paper presented at the Third Gathering of Biosemiotics Copenhagen, 11-14 July 2003.

2003. “Is Language a Primary Modeling System? – On Jurij Lotman’s Semiosphere”. Σεµιωτικη: Sign Systems Studies, 31.2.

2000. “Hu Shih and John Dewey: ‘Scientific Method’ in the May Fourth Era-China”, Comparative Criticism, 22, 91-103.

1998. “The Rise of Semiotics and the Liberal Arts: Reading Martianus Capella's The Marriage of Philosophy and Mercury”, MNEMOSYNE: A Journal of Classical Studies, 51.5, 538-53.

1998. “The Legacy of Josef Vachek and Its Implications on the Studies of Chinese Script”, invited Memorial Lecture at Prague Linguistic Circle, 4 November 1996, published in Czech as “Odkaz Josefa Vachka pro studium cínského písma”, Slovo a Slovesnost, 59, 241-48.

1996. “Semiographics: A Peircean Trichotomy of Classical Chinese Script”, Semiotica, 108.1-2, 31-43.